Chapter 3 Research Design and Methodology

- October 2019

- Thesis for: Master of Arts in Teaching

- University of Perpetual Help System Jonelta Pueblo de Panay

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Research Strategies and Methods

- First Online: 22 July 2021

Cite this chapter

- Paul Johannesson 3 &

- Erik Perjons 3

2752 Accesses

Researchers have since centuries used research methods to support the creation of reliable knowledge based on empirical evidence and logical arguments. This chapter offers an overview of established research strategies and methods with a focus on empirical research in the social sciences. We discuss research strategies, such as experiment, survey, case study, ethnography, grounded theory, action research, and phenomenology. Research methods for data collection are also described, including questionnaires, interviews, focus groups, observations, and documents. Qualitative and quantitative methods for data analysis are discussed. Finally, the use of research strategies and methods within design science is investigated.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bhattacherjee A (2012) Social science research: principles, methods, and practices, 2 edn. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Tampa, FL

Google Scholar

Blake W (2012) Delphi complete works of William Blake, 2nd edn. Delphi Classics

Bradburn NM, Sudman S, Wansink B (2004) Asking questions: the definitive guide to questionnaire design – for market research, political polls, and social and health questionnaires, revised edition. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Bryman A (2016) Social research methods, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Charmaz K (2014) Constructing grounded theory, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Coghlan D (2019) Doing action research in your own organization, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2017) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

MATH Google Scholar

Denscombe M (2017) The good research guide, 6th edn. Open University Press, London

Dey I (2003) Qualitative data analysis: a user friendly guide for social scientists. Routledge, London

Book Google Scholar

Fairclough N (2013) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language, 2 edn. Routledge, London

Field A, Hole GJ (2003) How to design and report experiments, 1st edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Fowler FJ (2013) Survey research methods, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Glaser B, Strauss A (1999) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Routledge, London

Kemmis S, McTaggart R, Nixon R (2016) The action research planner: doing critical participatory action research, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin

Krippendorff K (2018) Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology, 4th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

LeCompte MD, Schensul JJ (2010) Designing and conducting ethnographic research: an introduction, 2nd edn. AltaMira Press, Lanham, MD

McNiff J (2013) Action research: principles and practice, 3rd edn. Routledge, London

Oates BJ (2006) Researching information systems and computing. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Peterson RA (2000) Constructing effective questionnaires. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Prior L (2008) Repositioning documents in social research. Sociology 42(5):821–836

Article Google Scholar

Seidman I (2019) Interviewing as qualitative research: a guide for researchers in education and the social sciences, 5th edn. Teachers College Press, New York

Silverman D (2018) Doing qualitative research, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Stephens L (2004) Advanced statistics demystified, 1st edn. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York

Urdan TC (2016) Statistics in plain English, 4th ed. Routledge, London

Yin RK (2017) Case study research and applications: design and methods, 6th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stockholm University, Kista, Sweden

Paul Johannesson & Erik Perjons

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Johannesson, P., Perjons, E. (2021). Research Strategies and Methods. In: An Introduction to Design Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78132-3_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78132-3_3

Published : 22 July 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-78131-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-78132-3

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How To Write The Methodology Chapter

The what, why & how explained simply (with examples).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | September 2021 (Updated April 2023)

So, you’ve pinned down your research topic and undertaken a review of the literature – now it’s time to write up the methodology section of your dissertation, thesis or research paper . But what exactly is the methodology chapter all about – and how do you go about writing one? In this post, we’ll unpack the topic, step by step .

Overview: The Methodology Chapter

- The purpose of the methodology chapter

- Why you need to craft this chapter (really) well

- How to write and structure the chapter

- Methodology chapter example

- Essential takeaways

What (exactly) is the methodology chapter?

The methodology chapter is where you outline the philosophical underpinnings of your research and outline the specific methodological choices you’ve made. The point of the methodology chapter is to tell the reader exactly how you designed your study and, just as importantly, why you did it this way.

Importantly, this chapter should comprehensively describe and justify all the methodological choices you made in your study. For example, the approach you took to your research (i.e., qualitative, quantitative or mixed), who you collected data from (i.e., your sampling strategy), how you collected your data and, of course, how you analysed it. If that sounds a little intimidating, don’t worry – we’ll explain all these methodological choices in this post .

Why is the methodology chapter important?

The methodology chapter plays two important roles in your dissertation or thesis:

Firstly, it demonstrates your understanding of research theory, which is what earns you marks. A flawed research design or methodology would mean flawed results. So, this chapter is vital as it allows you to show the marker that you know what you’re doing and that your results are credible .

Secondly, the methodology chapter is what helps to make your study replicable. In other words, it allows other researchers to undertake your study using the same methodological approach, and compare their findings to yours. This is very important within academic research, as each study builds on previous studies.

The methodology chapter is also important in that it allows you to identify and discuss any methodological issues or problems you encountered (i.e., research limitations ), and to explain how you mitigated the impacts of these. Every research project has its limitations , so it’s important to acknowledge these openly and highlight your study’s value despite its limitations . Doing so demonstrates your understanding of research design, which will earn you marks. We’ll discuss limitations in a bit more detail later in this post, so stay tuned!

Need a helping hand?

How to write up the methodology chapter

First off, it’s worth noting that the exact structure and contents of the methodology chapter will vary depending on the field of research (e.g., humanities, chemistry or engineering) as well as the university . So, be sure to always check the guidelines provided by your institution for clarity and, if possible, review past dissertations from your university. Here we’re going to discuss a generic structure for a methodology chapter typically found in the sciences.

Before you start writing, it’s always a good idea to draw up a rough outline to guide your writing. Don’t just start writing without knowing what you’ll discuss where. If you do, you’ll likely end up with a disjointed, ill-flowing narrative . You’ll then waste a lot of time rewriting in an attempt to try to stitch all the pieces together. Do yourself a favour and start with the end in mind .

Section 1 – Introduction

As with all chapters in your dissertation or thesis, the methodology chapter should have a brief introduction. In this section, you should remind your readers what the focus of your study is, especially the research aims . As we’ve discussed many times on the blog, your methodology needs to align with your research aims, objectives and research questions. Therefore, it’s useful to frontload this component to remind the reader (and yourself!) what you’re trying to achieve.

In this section, you can also briefly mention how you’ll structure the chapter. This will help orient the reader and provide a bit of a roadmap so that they know what to expect. You don’t need a lot of detail here – just a brief outline will do.

Section 2 – The Methodology

The next section of your chapter is where you’ll present the actual methodology. In this section, you need to detail and justify the key methodological choices you’ve made in a logical, intuitive fashion. Importantly, this is the heart of your methodology chapter, so you need to get specific – don’t hold back on the details here. This is not one of those “less is more” situations.

Let’s take a look at the most common components you’ll likely need to cover.

Methodological Choice #1 – Research Philosophy

Research philosophy refers to the underlying beliefs (i.e., the worldview) regarding how data about a phenomenon should be gathered , analysed and used . The research philosophy will serve as the core of your study and underpin all of the other research design choices, so it’s critically important that you understand which philosophy you’ll adopt and why you made that choice. If you’re not clear on this, take the time to get clarity before you make any further methodological choices.

While several research philosophies exist, two commonly adopted ones are positivism and interpretivism . These two sit roughly on opposite sides of the research philosophy spectrum.

Positivism states that the researcher can observe reality objectively and that there is only one reality, which exists independently of the observer. As a consequence, it is quite commonly the underlying research philosophy in quantitative studies and is oftentimes the assumed philosophy in the physical sciences.

Contrasted with this, interpretivism , which is often the underlying research philosophy in qualitative studies, assumes that the researcher performs a role in observing the world around them and that reality is unique to each observer . In other words, reality is observed subjectively .

These are just two philosophies (there are many more), but they demonstrate significantly different approaches to research and have a significant impact on all the methodological choices. Therefore, it’s vital that you clearly outline and justify your research philosophy at the beginning of your methodology chapter, as it sets the scene for everything that follows.

Methodological Choice #2 – Research Type

The next thing you would typically discuss in your methodology section is the research type. The starting point for this is to indicate whether the research you conducted is inductive or deductive .

Inductive research takes a bottom-up approach , where the researcher begins with specific observations or data and then draws general conclusions or theories from those observations. Therefore these studies tend to be exploratory in terms of approach.

Conversely , d eductive research takes a top-down approach , where the researcher starts with a theory or hypothesis and then tests it using specific observations or data. Therefore these studies tend to be confirmatory in approach.

Related to this, you’ll need to indicate whether your study adopts a qualitative, quantitative or mixed approach. As we’ve mentioned, there’s a strong link between this choice and your research philosophy, so make sure that your choices are tightly aligned . When you write this section up, remember to clearly justify your choices, as they form the foundation of your study.

Methodological Choice #3 – Research Strategy

Next, you’ll need to discuss your research strategy (also referred to as a research design ). This methodological choice refers to the broader strategy in terms of how you’ll conduct your research, based on the aims of your study.

Several research strategies exist, including experimental , case studies , ethnography , grounded theory, action research , and phenomenology . Let’s take a look at two of these, experimental and ethnographic, to see how they contrast.

Experimental research makes use of the scientific method , where one group is the control group (in which no variables are manipulated ) and another is the experimental group (in which a specific variable is manipulated). This type of research is undertaken under strict conditions in a controlled, artificial environment (e.g., a laboratory). By having firm control over the environment, experimental research typically allows the researcher to establish causation between variables. Therefore, it can be a good choice if you have research aims that involve identifying causal relationships.

Ethnographic research , on the other hand, involves observing and capturing the experiences and perceptions of participants in their natural environment (for example, at home or in the office). In other words, in an uncontrolled environment. Naturally, this means that this research strategy would be far less suitable if your research aims involve identifying causation, but it would be very valuable if you’re looking to explore and examine a group culture, for example.

As you can see, the right research strategy will depend largely on your research aims and research questions – in other words, what you’re trying to figure out. Therefore, as with every other methodological choice, it’s essential to justify why you chose the research strategy you did.

Methodological Choice #4 – Time Horizon

The next thing you’ll need to detail in your methodology chapter is the time horizon. There are two options here: cross-sectional and longitudinal . In other words, whether the data for your study were all collected at one point in time (cross-sectional) or at multiple points in time (longitudinal).

The choice you make here depends again on your research aims, objectives and research questions. If, for example, you aim to assess how a specific group of people’s perspectives regarding a topic change over time , you’d likely adopt a longitudinal time horizon.

Another important factor to consider is simply whether you have the time necessary to adopt a longitudinal approach (which could involve collecting data over multiple months or even years). Oftentimes, the time pressures of your degree program will force your hand into adopting a cross-sectional time horizon, so keep this in mind.

Methodological Choice #5 – Sampling Strategy

Next, you’ll need to discuss your sampling strategy . There are two main categories of sampling, probability and non-probability sampling.

Probability sampling involves a random (and therefore representative) selection of participants from a population, whereas non-probability sampling entails selecting participants in a non-random (and therefore non-representative) manner. For example, selecting participants based on ease of access (this is called a convenience sample).

The right sampling approach depends largely on what you’re trying to achieve in your study. Specifically, whether you trying to develop findings that are generalisable to a population or not. Practicalities and resource constraints also play a large role here, as it can oftentimes be challenging to gain access to a truly random sample. In the video below, we explore some of the most common sampling strategies.

Methodological Choice #6 – Data Collection Method

Next up, you’ll need to explain how you’ll go about collecting the necessary data for your study. Your data collection method (or methods) will depend on the type of data that you plan to collect – in other words, qualitative or quantitative data.

Typically, quantitative research relies on surveys , data generated by lab equipment, analytics software or existing datasets. Qualitative research, on the other hand, often makes use of collection methods such as interviews , focus groups , participant observations, and ethnography.

So, as you can see, there is a tight link between this section and the design choices you outlined in earlier sections. Strong alignment between these sections, as well as your research aims and questions is therefore very important.

Methodological Choice #7 – Data Analysis Methods/Techniques

The final major methodological choice that you need to address is that of analysis techniques . In other words, how you’ll go about analysing your date once you’ve collected it. Here it’s important to be very specific about your analysis methods and/or techniques – don’t leave any room for interpretation. Also, as with all choices in this chapter, you need to justify each choice you make.

What exactly you discuss here will depend largely on the type of study you’re conducting (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods). For qualitative studies, common analysis methods include content analysis , thematic analysis and discourse analysis . In the video below, we explain each of these in plain language.

For quantitative studies, you’ll almost always make use of descriptive statistics , and in many cases, you’ll also use inferential statistical techniques (e.g., correlation and regression analysis). In the video below, we unpack some of the core concepts involved in descriptive and inferential statistics.

In this section of your methodology chapter, it’s also important to discuss how you prepared your data for analysis, and what software you used (if any). For example, quantitative data will often require some initial preparation such as removing duplicates or incomplete responses . Similarly, qualitative data will often require transcription and perhaps even translation. As always, remember to state both what you did and why you did it.

Section 3 – The Methodological Limitations

With the key methodological choices outlined and justified, the next step is to discuss the limitations of your design. No research methodology is perfect – there will always be trade-offs between the “ideal” methodology and what’s practical and viable, given your constraints. Therefore, this section of your methodology chapter is where you’ll discuss the trade-offs you had to make, and why these were justified given the context.

Methodological limitations can vary greatly from study to study, ranging from common issues such as time and budget constraints to issues of sample or selection bias . For example, you may find that you didn’t manage to draw in enough respondents to achieve the desired sample size (and therefore, statistically significant results), or your sample may be skewed heavily towards a certain demographic, thereby negatively impacting representativeness .

In this section, it’s important to be critical of the shortcomings of your study. There’s no use trying to hide them (your marker will be aware of them regardless). By being critical, you’ll demonstrate to your marker that you have a strong understanding of research theory, so don’t be shy here. At the same time, don’t beat your study to death . State the limitations, why these were justified, how you mitigated their impacts to the best degree possible, and how your study still provides value despite these limitations .

Section 4 – Concluding Summary

Finally, it’s time to wrap up the methodology chapter with a brief concluding summary. In this section, you’ll want to concisely summarise what you’ve presented in the chapter. Here, it can be a good idea to use a figure to summarise the key decisions, especially if your university recommends using a specific model (for example, Saunders’ Research Onion ).

Importantly, this section needs to be brief – a paragraph or two maximum (it’s a summary, after all). Also, make sure that when you write up your concluding summary, you include only what you’ve already discussed in your chapter; don’t add any new information.

Methodology Chapter Example

In the video below, we walk you through an example of a high-quality research methodology chapter from a dissertation. We also unpack our free methodology chapter template so that you can see how best to structure your chapter.

Wrapping Up

And there you have it – the methodology chapter in a nutshell. As we’ve mentioned, the exact contents and structure of this chapter can vary between universities , so be sure to check in with your institution before you start writing. If possible, try to find dissertations or theses from former students of your specific degree program – this will give you a strong indication of the expectations and norms when it comes to the methodology chapter (and all the other chapters!).

Also, remember the golden rule of the methodology chapter – justify every choice ! Make sure that you clearly explain the “why” for every “what”, and reference credible methodology textbooks or academic sources to back up your justifications.

If you need a helping hand with your research methodology (or any other component of your research), be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through every step of the research journey. Until next time, good luck!

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

highly appreciated.

This was very helpful!

This was helpful

Thanks ,it is a very useful idea.

Thanks ,it is very useful idea.

Thank you so much, this information is very useful.

Thank you very much. I must say the information presented was succinct, coherent and invaluable. It is well put together and easy to comprehend. I have a great guide to create the research methodology for my dissertation.

Highly clear and useful.

I understand a bit on the explanation above. I want to have some coach but I’m still student and don’t have any budget to hire one. A lot of question I want to ask.

Thank you so much. This concluded my day plan. Thank you so much.

Thanks it was helpful

Great information. It would be great though if you could show us practical examples.

Thanks so much for this information. God bless and be with you

Thank you so so much. Indeed it was helpful

This is EXCELLENT!

I was totally confused by other explanations. Thank you so much!.

justdoing my research now , thanks for the guidance.

Thank uuuu! These contents are really valued for me!

This is powerful …I really like it

Highly useful and clear, thank you so much.

Highly appreciated. Good guide

That was helpful. Thanks

This is very useful.Thank you

Very helpful information. Thank you

This is exactly what I was looking for. The explanation is so detailed and easy to comprehend. Well done and thank you.

Great job. You just summarised everything in the easiest and most comprehensible way possible. Thanks a lot.

Thank you very much for the ideas you have given this will really help me a lot. Thank you and God Bless.

Such great effort …….very grateful thank you

Please accept my sincere gratitude. I have to say that the information that was delivered was congruent, concise, and quite helpful. It is clear and straightforward, making it simple to understand. I am in possession of an excellent manual that will assist me in developing the research methods for my dissertation.

Thank you for your great explanation. It really helped me construct my methodology paper.

thank you for simplifieng the methodoly, It was realy helpful

Very helpful!

Thank you for your great explanation.

The explanation I have been looking for. So clear Thank you

Thank you very much .this was more enlightening.

helped me create the in depth and thorough methodology for my dissertation

Thank you for the great explaination.please construct one methodology for me

I appreciate you for the explanation of methodology. Please construct one methodology on the topic: The effects influencing students dropout among schools for my thesis

This helped me complete my methods section of my dissertation with ease. I have managed to write a thorough and concise methodology!

its so good in deed

wow …what an easy to follow presentation. very invaluable content shared. utmost important.

Peace be upon you, I am Dr. Ahmed Khedr, a former part-time professor at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt. I am currently teaching research methods, and I have been dealing with your esteemed site for several years, and I found that despite my long experience with research methods sites, it is one of the smoothest sites for evaluating the material for students, For this reason, I relied on it a lot in teaching and translated most of what was written into Arabic and published it on my own page on Facebook. Thank you all… Everything I posted on my page is provided with the names of the writers of Grad coach, the title of the article, and the site. My best regards.

A remarkably simple and useful guide, thank you kindly.

I real appriciate your short and remarkable chapter summary

Bravo! Very helpful guide.

Only true experts could provide such helpful, fantastic, and inspiring knowledge about Methodology. Thank you very much! God be with you and us all!

highly appreciate your effort.

This is a very well thought out post. Very informative and a great read.

THANKS SO MUCH FOR SHARING YOUR NICE IDEA

I love you Emma, you are simply amazing with clear explanations with complete information. GradCoach really helped me to do my assignment here in Auckland. Mostly, Emma make it so simple and enjoyable

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

2024 Theses Doctoral

Statistically Efficient Methods for Computation-Aware Uncertainty Quantification and Rare-Event Optimization

He, Shengyi

The thesis covers two fundamental topics that are important across the disciplines of operations research, statistics and even more broadly, namely stochastic optimization and uncertainty quantification, with the common theme to address both statistical accuracy and computational constraints. Here, statistical accuracy encompasses the precision of estimated solutions in stochastic optimization, as well as the tightness or reliability of confidence intervals. Computational concerns arise from rare events or expensive models, necessitating efficient sampling methods or computation procedures. In the first half of this thesis, we study stochastic optimization that involves rare events, which arises in various contexts including risk-averse decision-making and training of machine learning models. Because of the presence of rare events, crude Monte Carlo methods can be prohibitively inefficient, as it takes a sample size reciprocal to the rare-event probability to obtain valid statistical information about the rare-event. To address this issue, we investigate the use of importance sampling (IS) to reduce the required sample size. IS is commonly used to handle rare events, and the idea is to sample from an alternative distribution that hits the rare event more frequently and adjusts the estimator with a likelihood ratio to retain unbiasedness. While IS has been long studied, most of its literature focuses on estimation problems and methodologies to obtain good IS in these contexts. Contrary to these studies, the first half of this thesis provides a systematic study on the efficient use of IS in stochastic optimization. In Chapter 2, we propose an adaptive procedure that converts an efficient IS for gradient estimation to an efficient IS procedure for stochastic optimization. Then, in Chapter 3, we provide an efficient IS for gradient estimation, which serves as the input for the procedure in Chapter 2. In the second half of this thesis, we study uncertainty quantification in the sense of constructing a confidence interval (CI) for target model quantities or prediction. We are interested in the setting of expensive black-box models, which means that we are confined to using a low number of model runs, and we also lack the ability to obtain auxiliary model information such as gradients. In this case, a classical method is batching, which divides data into a few batches and then constructs a CI based on the batched estimates. Another method is the recently proposed cheap bootstrap that is constructed on a few resamples in a similar manner as batching. These methods could save computation since they do not need an accurate variability estimator which requires sufficient model evaluations to obtain. Instead, they cancel out the variability when constructing pivotal statistics, and thus obtain asymptotically valid t-distribution-based CIs with only few batches or resamples. The second half of this thesis studies several theoretical aspects of these computation-aware CI construction methods. In Chapter 4, we study the statistical optimality on CI tightness among various computation-aware CIs. Then, in Chapter 5, we study the higher-order coverage errors of batching methods. Finally, Chapter 6 is a related investigation on the higher-order coverage and correction of distributionally robust optimization (DRO) as another CI construction tool, which assumes an amount of analytical information on the model but bears similarity to Chapter 5 in terms of analysis techniques.

- Operations research

- Stochastic processes--Mathematical models

- Mathematical optimization

- Bootstrap (Statistics)

- Sampling (Statistics)

More About This Work

- DOI Copy DOI to clipboard

Reference Examples

More than 100 reference examples and their corresponding in-text citations are presented in the seventh edition Publication Manual . Examples of the most common works that writers cite are provided on this page; additional examples are available in the Publication Manual .

To find the reference example you need, first select a category (e.g., periodicals) and then choose the appropriate type of work (e.g., journal article ) and follow the relevant example.

When selecting a category, use the webpages and websites category only when a work does not fit better within another category. For example, a report from a government website would use the reports category, whereas a page on a government website that is not a report or other work would use the webpages and websites category.

Also note that print and electronic references are largely the same. For example, to cite both print books and ebooks, use the books and reference works category and then choose the appropriate type of work (i.e., book ) and follow the relevant example (e.g., whole authored book ).

Examples on these pages illustrate the details of reference formats. We make every attempt to show examples that are in keeping with APA Style’s guiding principles of inclusivity and bias-free language. These examples are presented out of context only to demonstrate formatting issues (e.g., which elements to italicize, where punctuation is needed, placement of parentheses). References, including these examples, are not inherently endorsements for the ideas or content of the works themselves. An author may cite a work to support a statement or an idea, to critique that work, or for many other reasons. For more examples, see our sample papers .

Reference examples are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Chapter 10 and the Concise Guide Chapter 10

Related handouts

- Common Reference Examples Guide (PDF, 147KB)

- Reference Quick Guide (PDF, 225KB)

Textual Works

Textual works are covered in Sections 10.1–10.8 of the Publication Manual . The most common categories and examples are presented here. For the reviews of other works category, see Section 10.7.

- Journal Article References

- Magazine Article References

- Newspaper Article References

- Blog Post and Blog Comment References

- UpToDate Article References

- Book/Ebook References

- Diagnostic Manual References

- Children’s Book or Other Illustrated Book References

- Classroom Course Pack Material References

- Religious Work References

- Chapter in an Edited Book/Ebook References

- Dictionary Entry References

- Wikipedia Entry References

- Report by a Government Agency References

- Report with Individual Authors References

- Brochure References

- Ethics Code References

- Fact Sheet References

- ISO Standard References

- Press Release References

- White Paper References

- Conference Presentation References

- Conference Proceeding References

- Published Dissertation or Thesis References

- Unpublished Dissertation or Thesis References

- ERIC Database References

- Preprint Article References

Data and Assessments

Data sets are covered in Section 10.9 of the Publication Manual . For the software and tests categories, see Sections 10.10 and 10.11.

- Data Set References

- Toolbox References

Audiovisual Media

Audiovisual media are covered in Sections 10.12–10.14 of the Publication Manual . The most common examples are presented together here. In the manual, these examples and more are separated into categories for audiovisual, audio, and visual media.

- Artwork References

- Clip Art or Stock Image References

- Film and Television References

- Musical Score References

- Online Course or MOOC References

- Podcast References

- PowerPoint Slide or Lecture Note References

- Radio Broadcast References

- TED Talk References

- Transcript of an Audiovisual Work References

- YouTube Video References

Online Media

Online media are covered in Sections 10.15 and 10.16 of the Publication Manual . Please note that blog posts are part of the periodicals category.

- Facebook References

- Instagram References

- LinkedIn References

- Online Forum (e.g., Reddit) References

- TikTok References

- X References

- Webpage on a Website References

- Clinical Practice References

- Open Educational Resource References

- Whole Website References

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

APA Sample Paper

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Note: This page reflects the latest version of the APA Publication Manual (i.e., APA 7), which released in October 2019. The equivalent resource for the older APA 6 style can be found here .

Media Files: APA Sample Student Paper , APA Sample Professional Paper

This resource is enhanced by Acrobat PDF files. Download the free Acrobat Reader

Note: The APA Publication Manual, 7 th Edition specifies different formatting conventions for student and professional papers (i.e., papers written for credit in a course and papers intended for scholarly publication). These differences mostly extend to the title page and running head. Crucially, citation practices do not differ between the two styles of paper.

However, for your convenience, we have provided two versions of our APA 7 sample paper below: one in student style and one in professional style.

Note: For accessibility purposes, we have used "Track Changes" to make comments along the margins of these samples. Those authored by [AF] denote explanations of formatting and [AWC] denote directions for writing and citing in APA 7.

APA 7 Student Paper:

Apa 7 professional paper:.

- En Español

- Medical Devices

- Radiation-Emitting Products

- Vaccines, Blood & Biologics

- Animal & Veterinary

- Tobacco Products

CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21

This information is current as of Dec 22, 2023 .

This online reference for CFR Title 21 is updated once a year. For the most up-to-date version of CFR Title 21, go to the Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (eCFR).

Learn More...

| Search Database |

- Medical Device Reports (MAUDE)

- CDRH Export Certificate Validation (CECV)

- CDRH FOIA Electronic Reading Room

- Device Classification

- FDA Guidance Documents

- Humanitarian Device Exemption

- Medsun Reports

- Premarket Approvals (PMAs)

- Post-Approval Studies

- Postmarket Surveillance Studies

- Radiation-Emitting Electronic Products Corrective Actions

- Registration & Listing

- Total Product Life Cycle

- X-Ray Assembler

This website has been translated to Spanish from English, and is updated often. It is possible that some links will connect you to content only available in English or some of the words on the page will appear in English until translation has been completed (usually within 24 hours). We appreciate your patience with the translation process. In the case of any discrepancy in meaning, the English version is considered official. Thank you for visiting esp.fda.gov/tabaco.

6.2 Obedience, Power, and Leadership

Learning Objectives

- Describe and interpret the results of Stanley Milgram’s research on obedience to authority.

- Compare the different types of power proposed by John French and Bertram Raven and explain how they produce conformity.

- Define leadership and explain how effective leaders are determined by the person, the situation, and the person-situation interaction.

One of the fundamental aspects of social interaction is that some individuals have more influence than others. Social power can be defined as the ability of a person to create conformity even when the people being influenced may attempt to resist those changes (Fiske, 1993; Keltner, Gruenfeld, & Anderson, 2003). Bosses have power over their workers, parents have power over their children, and, more generally, we can say that those in authority have power over their subordinates. In short, power refers to the process of social influence itself—those who have power are those who are most able to influence others.

Milgram’s Studies on Obedience to Authority

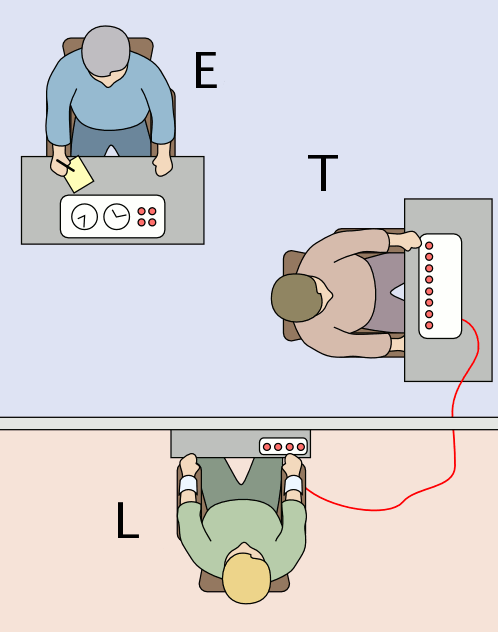

The powerful ability of those in authority to control others was demonstrated in a remarkable set of studies performed by Stanley Milgram (1963). Milgram was interested in understanding the factors that lead people to obey the orders given by people in authority. He designed a study in which he could observe the extent to which a person who presented himself as an authority would be able to produce obedience, even to the extent of leading people to cause harm to others.

Like his professor Solomon Asch, Milgram’s interest in social influence stemmed in part from his desire to understand how the presence of a powerful person—particularly the German dictator Adolf Hitler who ordered the killing of millions of people during World War II—could produce obedience. Under Hitler’s direction, the German SS troops oversaw the execution of 6 million Jews as well as other “undesirables,” including political and religious dissidents, homosexuals, mentally and physically disabled people, and prisoners of war. Milgram used newspaper ads to recruit men (and in one study, women) from a wide variety of backgrounds to participate in his research. When the research participant arrived at the lab, he or she was introduced to a man who the participant believed was another research participant but who was actually an experimental confederate. The experimenter explained that the goal of the research was to study the effects of punishment on learning. After the participant and the confederate both consented to participate in the study, the researcher explained that one of them would be randomly assigned to be the teacher and the other the learner. They were each given a slip of paper and asked to open it and to indicate what it said. In fact both papers read teacher , which allowed the confederate to pretend that he had been assigned to be the learner and thus to assure that the actual participant was always the teacher. While the research participant (now the teacher) looked on, the learner was taken into the adjoining shock room and strapped to an electrode that was to deliver the punishment. The experimenter explained that the teacher’s job would be to sit in the control room and to read a list of word pairs to the learner. After the teacher read the list once, it would be the learner’s job to remember which words went together. For instance, if the word pair was blue-sofa , the teacher would say the word blue on the testing trials and the learner would have to indicate which of four possible words ( house , sofa , cat , or carpet ) was the correct answer by pressing one of four buttons in front of him. After the experimenter gave the “teacher” a sample shock (which was said to be at 45 volts) to demonstrate that the shocks really were painful, the experiment began. The research participant first read the list of words to the learner and then began testing him on his learning.

The shock panel, as shown in Figure 6.9, “The Shock Apparatus Used in Milgram’s Obedience Study,” was presented in front of the teacher, and the learner was not visible in the shock room. The experimenter sat behind the teacher and explained to him that each time the learner made a mistake the teacher was to press one of the shock switches to administer the shock. They were to begin with the smallest possible shock (15 volts) but with each mistake the shock was to increased by one level (an additional 15 volts).

Once the learner (who was, of course, actually an experimental confederate) was alone in the shock room, he unstrapped himself from the shock machine and brought out a tape recorder that he used to play a prerecorded series of responses that the teacher could hear through the wall of the room. As you can see in Table 6.1,”The Confederate’s Schedule of Protest in the Milgram Experiments,” the teacher heard the learner say “ugh!” after the first few shocks. After the next few mistakes, when the shock level reached 150 volts, the learner was heard to exclaim “Get me out of here, please. My heart’s starting to bother me. I refuse to go on. Let me out!” As the shock reached about 270 volts, the learner’s protests became more vehement, and after 300 volts the learner proclaimed that he was not going to answer any more questions. From 330 volts and up the learner was silent. The experimenter responded to participants’ questions at this point, if they asked any, with a scripted response indicating that they should continue reading the questions and applying increasing shock when the learner did not respond.

| 75 volts | Ugh! |

|---|---|

| 90 volts | Ugh! |

| 105 volts | Ugh! (louder) |

| 120 volts | Ugh! Hey, this really hurts. |

| 135 volts | Ugh!! |

| 150 volts | Ugh!! Experimenter! That’s all. Get me out of here. I told you I had heart trouble. My heart’s starting to bother me now. Get me out of here, please. My heart’s starting to bother me. I refuse to go on. Let me out! |

| 165 volts | Ugh! Let me out! (shouting) |

| 180 volts | Ugh! I can’t stand the pain. Let me out of here! (shouting) |

| 195 volts | Ugh! Let me out of here! Let me out of here! My heart’s bothering me. Let me out of here! You have no right to keep me here! Let me out! Let me out of here! Let me out! Let me out of here! My heart’s bothering me. Let me out! Let me out! |

| 210 volts | Ugh!! Experimenter! Get me out of here. I’ve had enough. I won’t be in the experiment any more. |

| 225 volts | Ugh! |

| 240 volts | Ugh! |

| 255 volts | Ugh! Get me out of here. |

| 270 volts | (agonized scream) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. Let me out of here. Let me out. Do you hear? Let me out of here. |

| 285 volts | (agonized scream) |

| 300 volts | (agonized scream) I absolutely refuse to answer any more. Get me out of here. You can’t hold me here. Get me out. Get me out of here. |

| 315 volts | (intensely agonized scream) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. My heart’s bothering me. Let me out, I tell you. (hysterically) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. You have no right to hold me here. Let me out! Let me out! Let me out! Let me out of here! Let me out! Let me out! |

Before Milgram conducted his study, he described the procedure to three groups—college students, middle-class adults, and psychiatrists—asking each of them if they thought they would shock a participant who made sufficient errors at the highest end of the scale (450 volts). One hundred percent of all three groups thought they would not do so. He then asked them what percentage of “other people” would be likely to use the highest end of the shock scale, at which point the three groups demonstrated remarkable consistency by all producing (rather optimistic) estimates of around 1% to 2%.

The results of the actual experiments were themselves quite shocking. Although all of the participants gave the initial mild levels of shock, responses varied after that. Some refused to continue after about 150 volts, despite the insistence of the experimenter to continue to increase the shock level. Still others, however, continued to present the questions, and to administer the shocks, under the pressure of the experimenter, who demanded that they continue. In the end, 65% of the participants continued giving the shock to the learner all the way up to the 450 volts maximum, even though that shock was marked as “danger: severe shock,” and there had been no response heard from the participant for several trials. In sum, almost two-thirds of the men who participated had, as far as they knew, shocked another person to death, all as part of a supposed experiment on learning.

Studies similar to Milgram’s findings have since been conducted all over the world (Blass, 1999), with obedience rates ranging from a high of 90% in Spain and the Netherlands (Meeus & Raaijmakers, 1986) to a low of 16% among Australian women (Kilham & Mann, 1974). In case you are thinking that such high levels of obedience would not be observed in today’s modern culture, there is evidence that they would be. Recently, Milgram’s results were almost exactly replicated, using men and women from a wide variety of ethnic groups, in a study conducted by Jerry Burger at Santa Clara University. In this replication of the Milgram experiment, 65% of the men and 73% of the women agreed to administer increasingly painful electric shocks when they were ordered to by an authority figure (Burger, 2009). In the replication, however, the participants were not allowed to go beyond the 150 volt shock switch.

Although it might be tempting to conclude that Milgram’s experiments demonstrate that people are innately evil creatures who are ready to shock others to death, Milgram did not believe that this was the case. Rather, he felt that it was the social situation, and not the people themselves, that was responsible for the behavior. To demonstrate this, Milgram conducted research that explored a number of variations on his original procedure, each of which demonstrated that changes in the situation could dramatically influence the amount of obedience. These variations are summarized in Figure 6.10.

| Experimental Replication | Description | Percent Obedience |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Initial study: Yale University men and women | 65 |

| Experiment 10 | The study is conducted off campus, in Bridgeport CT | 48 |

| Experiment 3 | The teacher is in the same room as the learner | 40 |

| Experiment 4 | The participant must hold the learner’s hand on the shock pad | 20 |

| Experiment 7 | The experimenter communicates by phone from another room | 20 |

| Experiment 13 | An “ordinary man” (presumably another research participants refuse to give shock | 20 |

| Experiment 17 | Two other research participants refuse to give shock | 10 |

| Experiment 11 | The teacher chooses his own preferred shock level | 0 |

| Experiment 15 | One experimenter indicates that the participant should not shock | 0 |

This figure presents the percentage of participants in Stanley Milgram’s (1974) studies on obedience who were maximally obedient (that is, who gave all 450 volts of shock) in some of the variations that he conducted. In the initial study, the authority’s status and power was maximized—the experimenter had been introduced as a respected scientist at a respected university. However, in replications of the study in which the experimenter’s authority was decreased, obedience also declined. In one replication the status of the experimenter was reduced by having the experiment take place in a building located in Bridgeport, Connecticut, rather than at the labs on the Yale University campus, and the research was ostensibly sponsored by a private commercial research firm instead of by the university. In this study, less obedience was observed (only 48% of the participants delivered the maximum shock). Full obedience was also reduced (to 20%) when the experimenter’s ability to express his authority was limited by having him sit in an adjoining room and communicate to the teacher by telephone. And when the experimenter left the room and had another student (actually a confederate) give the instructions for him, obedience was also reduced to 20%.

In addition to the role of authority, Milgram’s studies also confirmed the role of unanimity in producing obedience. When another research participant (again an experimental confederate) began by giving the shocks but then later refused to continue and the participant was asked to take over, only 10% were obedient. And if two experimenters were present but only one proposed shocking while the other argued for stopping the shocks, all the research participants took the more benevolent advice and did not shock. But perhaps most telling were the studies in which Milgram allowed the participants to choose their own shock levels or in which one of the experimenters suggested that they should not actually use the shock machine. In these situations, there was virtually no shocking. These conditions show that people do not like to harm others, and when given a choice they will not. On the other hand, the social situation can create powerful, and potentially deadly, social influence.

One final note about Milgram’s studies: Although Milgram explicitly focused on the situational factors that led to greater obedience, these have been found to interact with certain personality characteristics (yet another example of a person-situation interaction) . Specifically, authoritarianism ( a tendency to prefer things to be simple rather than complex and to hold traditional values ), conscientiousness ( a tendency to be responsible, orderly, and dependable ), and agreeableness ( a tendency to be good natured, cooperative, and trusting ) are all related to higher levels of obedience whereas higher moral reasoning ( the manner in which one makes ethical judgments ) and social intelligence ( an ability to develop a clear perception of the situation using situational cues ) both predict resistance to the demands of the authority figure (Bègue et al., 2014; Blass, 1991).

Before moving on to the next section, it is worth noting that although we have discussed both conformity and obedience in this chapter, they are not the same thing. While both are forms of social influence, we most often tend to conform to our peers, whereas we obey those in positions of authority. Furthermore, the pressure to conform tends to be implicit, whereas the order to obey is typically rather explicit. And finally, whereas people don’t like admitting to having conformed (especially via normative social influence), they will more readily point to the authority figure as the source of their actions (especially when they have done something they are embarrassed or ashamed of).

Social Psychology in the Public Interest

The Stanford Prison Study and Abu Ghraib

In Milgram’s research we can see a provocative demonstration of how people who have power can control the behavior of others. Can our understanding of the social psychological factors that produce obedience help us explain the events that occurred in 2004 at Abu Ghraib, the Iraqi prison in which U.S. soldiers physically and psychologically tortured their Iraqi prisoners? The social psychologist Philip Zimbardo thinks so. He notes the parallels between the events that occurred at Abu Ghraib and the events that occurred in the “prison study” that he conducted in 1971 ( Stanford Prison Study ).

In that study, Zimbardo and his colleagues set up a mock prison. They selected 23 student volunteers and divided them into two groups. One group was chosen to be the “prisoners.” They were picked up at their homes by actual police officers, “arrested,” and brought to the prison to be guarded by the other group of students—the “guards.” The two groups were placed in a setting that was designed to look like a real prison, and the role-play began.

The study was expected to run for two weeks. However, on the second day, the prisoners tried to rebel against the guards. The guards quickly moved to stop the rebellion by using both psychological punishment and physical abuse. In the ensuing days, the guards denied the prisoners food, water, and sleep; shot them with fire-extinguisher spray; threw their blankets into the dirt; forced them to clean toilet bowls with their bare hands; and stripped them naked. On the fifth night the experimenters witnessed the guards putting bags over the prisoners’ heads, chaining their legs, and marching them around. At this point, a former student who was not involved with the study spoke up, declaring the treatment of the prisoners to be immoral. As a result, the researchers stopped the experiment early.

The conclusions of Zimbardo’s research were seemingly clear: people may be so profoundly influenced by their social situation that they become coldhearted jail masters who torture their victims. Arguably, this conclusion may be applied to the research team itself, which seemingly neglected ethical principles in the pursuit of their research goals. Zimbardo’s research may help us understand the events that occurred at Abu Ghraib, a military prison used by the U.S. military following the successful toppling of the dictator Saddam Hussein. Zimbardo acted as an expert witness in the trial of Sergeant Chip Frederick, who was sentenced to eight years in prison for his role in the abuse at Abu Ghraib. Frederick was the army reservist who was put in charge of the night shift at Tier 1A, where the detainees were abused. During this trial, Frederick said, “What I did was wrong, and I don’t understand why I did it.” Zimbardo believes that Frederick acted exactly like the students in the prison study. He worked in a prison that was overcrowded, filthy, and dangerous, and where he was expected to maintain control over the Iraqi prisoners—in short, the situation he found himself in was very similar to that of Zimbardo’s prison study.

In a recent interview, Zimbardo argued (you can tell that he is a social psychologist) that “human behavior is more influenced by things outside of us than inside.” He believes that, despite our moral and religious beliefs and despite the inherent goodness of people, there are times when external circumstances can overwhelm us and we will do things we never thought we were capable of doing. He argued that “if you’re not aware that this can happen, you can be seduced by evil. We need inoculations against our own potential for evil. We have to acknowledge it. Then we can change it” (Driefus, 2007).

You may wonder whether the extreme behavior of the guards and prisoners in Zimbardo’s prison study was unique to the particular social context that he created. Recent research by Stephen Reicher and Alex Haslam (2006) suggests that this is indeed the case. In their research, they recreated Zimbardo’s prison study while making some small, but important, changes. For one, the prisoners were not “arrested” before the study began, and the setup of the jail was less realistic. Furthermore, the researchers in this experiment told the “guards” and the “prisoners” that the groups were arbitrary and could change over time (that is, that some prisoners might be able to be promoted to guards). The results of this study were entirely different than those found by Zimbardo. This study was also stopped early, but more because the guards felt uncomfortable in their superior position than because the prisoners were being abused. This “prison” simply did not feel like a real prison to the participants, and, as a result, they did not take on the roles they were assigned. Again, the conclusions are clear—the specifics of the social situation, more than the people themselves, are often the most important determinants of behavior.

Types of Power

One of the most influential theories of power was developed by Bertram Raven and John French (French & Raven, 1959; Raven, 1992). Raven identified five different types of power— reward power , coercive power , legitimate power , referent power , and expert power (shown in Table 6.2, “Types of Power”), arguing that each type of power involves a different type of social influence and that the different types vary in terms of whether their use will create public compliance or private acceptance. Understanding the types of power is important because it allows us to see more clearly the many ways that people can influence others. Let’s consider these five types of power, beginning with those that are most likely to produce public compliance only and moving on to those that are more likely to produce private acceptance.

| Reward power | The ability to distribute positive or negative rewards |

|---|---|

| Coercive power | The ability to dispense punishments |

| Legitimate power | Authority that comes from a belief on the part of those being influenced that the person has a legitimate right to demand obedience |

| Referent power | Influence based on identification with, attraction to, or respect for the power-holder |

| Expert power | Power that comes from others’ beliefs that the power-holder possesses superior skills and abilities |

| Note: French and Raven proposed five types of power, which differ in their likelihood of producing public compliance or private acceptance. | |

Reward Power

Reward power occurs when one person is able to influence others by providing them with positive outcomes . Bosses have reward power over employees because they are able to increase employees’ salary and job benefits, and teachers have reward power over students because they can assign students high marks. The variety of rewards that can be used by the powerful is almost endless and includes verbal praise or approval, the awarding of status or prestige, and even direct financial payment. The ability to wield reward power over those we want to influence is contingent on the needs of the person being influenced. Power is greater when the person being influenced has a strong desire to obtain the reward, and power is weaker when the individual does not need the reward. A boss will have more influence on an employee who has no other job prospects than on one who is being sought after by other corporations, and expensive presents will be more effective in persuading those who cannot buy the items with their own money. Because the change in behavior that results from reward power is driven by the reward itself, its use is usually more likely to produce public compliance than private acceptance.

Coercive Power

Coercive power is power that is based on the ability to create negative outcomes for others, for instance by bullying, intimidating, or otherwise punishing . Bosses have coercive power over employees if they are able (and willing) to punish employees by reducing their salary, demoting them to a lower position, embarrassing them, or firing them. And friends can coerce each other through teasing, humiliation, and ostracism. people who are punished too much are likely to look for other situations that provide more positive outcomes.

In many cases, power-holders use reward and coercive power at the same time—for instance, by both increasing salaries as a result of positive performance but also threatening to reduce them if the performance drops. Because the use of coercion has such negative consequences, authorities are generally more likely to use reward than coercive power (Molm, 1997). Coercion is usually more difficult to use, since it often requires energy to keep the person from avoiding the punishment by leaving the situation altogether. And coercive power is less desirable for both the power-holder and the person being influenced because it creates an environment of negative feelings and distrust that is likely to make interactions difficult, undermine satisfaction, and lead to retaliation against the power-holder (Tepper et al., 2009). As with reward power, coercive power is more likely to produce public compliance than private acceptance. Furthermore, in both cases the effective use of the power requires that the power-holder continually monitor the behavior of the target to be sure that he or she is complying. This monitoring may itself lead to a sense of mistrust between the two individuals in the relationship. The power-holder feels (perhaps unjustly) that the target is only complying due to the monitoring, whereas the target feels (again perhaps unjustly) that the power-holder does not trust him or her.

Legitimate Power

Whereas reward and coercive power are likely to produce the desired behavior, other types of power, which are not so highly focused around reward and punishment, are more likely to create changes in attitudes (private acceptance) as well as behavior. In many ways, then, these sources of power are stronger because they produce real belief change. Legitimate power is power vested in those who are appointed or elected to positions of authority , such as teachers, politicians, police officers, and judges, and their power is successful because members of the group accept it as appropriate. We accept that governments can levy taxes and that judges can decide the outcomes of court cases because we see these groups and individuals as valid parts of our society. Individuals with legitimate power can exert substantial influence on their followers.

Those with legitimate power may not only create changes in the behavior of others but also have the power to create and change the social norms of the group. In some cases, legitimate power is given to the authority figure as a result of laws or elections, or as part of the norms, traditions, and values of the society. The power that the experimenter had over the research participants in Milgram’s study on obedience seems to have been primarily the result of his legitimate power as a respected scientist at an important university. In other cases, legitimate power comes more informally, as a result of being a respected group member. People who contribute to the group process and follow group norms gain status within the group and therefore earn legitimate power.

In some cases, legitimate power can even be used successfully by those who do not seem to have much power. After Hurricane Katrina hit the city of New Orleans in 2005, the people there demanded that the United States federal government help them rebuild the city. Although these people did not have much reward or coercive power, they were nevertheless perceived as good and respected citizens of the United States. Many U.S. citizens tend to believe that people who do not have as much as others (for instance, those who are very poor) should be treated fairly and that these people may legitimately demand resources from those who have more. This might not always work, but to the extent that it does it represents a type of legitimate power—power that comes from a belief in the appropriateness or obligation to respond to the requests of others with legitimate standing.

Referent Power

People with referent power have an ability to influence others because they can lead those others to identify with them . In this case, the person who provides the influence is (a) a member of an important reference group—someone we personally admire and attempt to emulate; (b) a charismatic, dynamic, and persuasive leader; or (c) a person who is particularly attractive or famous (Heath, McCarthy, & Mothersbaugh, 1994; Henrich & Gil-White, 2001; Kamins, 1989; Wilson & Sherrell, 1993).

A young child who mimics the opinions or behaviors of an older sibling or a famous sportsperson, or a religious person who follows the advice of a respected religious leader, is influenced by referent power. Referent power generally produces private acceptance rather than public compliance (Kelman, 1961). The influence brought on by referent power may occur in a passive sense because the person being emulated does not necessarily attempt to influence others, and the person who is being influenced may not even realize that the influence is occurring. In other cases, however, the person with referent power (such as the leader of a cult) may make full use of his or her status as the target of identification or respect to produce change. In either case, referent power is a particularly strong source of influence because it is likely to result in the acceptance of the opinions of the important other.

Expert Power

French and Raven’s final source of power is expert power. Experts have knowledge or information, and conforming to those whom we perceive to be experts is useful for making decisions about issues for which we have insufficient expertise. Expert power thus represents a type of informational influence based on the fundamental desire to obtain valid and accurate information, and where the outcome is likely to be private acceptance . Conformity to the beliefs or instructions of doctors, teachers, lawyers, and computer experts is an example of expert influence; we assume that these individuals have valid information about their areas of expertise, and we accept their opinions based on this perceived expertise (particularly if their advice seems to be successful in solving problems). Indeed, one method of increasing one’s power is to become an expert in a domain. Expert power is increased for those who possess more information about a relevant topic than others do because the others must turn to this individual to gain the information. You can see, then, that if you want to influence others, it can be useful to gain as much information about the topic as you can.

Research Focus

Does Power Corrupt?

Having power provides some benefits for those who have it. In comparison to those with less power, people who have more power over others are more confident and more attuned to potential opportunities in their environment (Anderson & Berdahl, 2002). They are also more likely than are people with less power to take action to meet their goals (Anderson & Galinsky, 2006; Galinsky, Gruenfeld, & Magee, 2003). Despite these advantages of having power, a little power goes a long way and having too much can be dangerous, for both the targets of the power and the power-holder himself or herself.

In an experiment by David Kipnis (1972), college students played the role of “supervisors” who were supposedly working on a task with other students (the “workers”). According to random assignment to experimental conditions, one half of the supervisors were able to influence the workers through legitimate power only, by sending them messages attempting to persuade them to work harder. The other half of the supervisors were given increased power. In addition to being able to persuade the workers to increase their output through the messages, they were also given both reward power (the ability to give small monetary rewards) and coercive power (the ability to take away earlier rewards). Although the workers (who were actually preprogrammed) performed equally well in both conditions, the participants who were given more power took advantage of it by more frequently contacting the workers and more frequently threatening them. The students in this condition relied almost exclusively on coercive power rather than attempting to use their legitimate power to develop positive relations with the subordinates. Although it did not increase the workers’ performance, having the extra power had a negative effect on the power-holders’ images of the workers. At the end of the study, the supervisors who had been given extra power rated the workers more negatively, were less interested in meeting them, and felt that the only reason the workers did well was to obtain the rewards.

The conclusion of these researchers is clear: having power may lead people to use it, even though it may not be necessary, which may then lead them to believe that their subordinates are performing only because of the threats. Although using excess power may be successful in the short run, power that is based exclusively on reward and coercion is not likely to produce a positive environment for either the power-holder or the subordinate. People with power may also be more likely to stereotype people with less power than they have (Depret & Fiske, 1999) and may be less likely to help other people who are in need (van Kleef et al., 2008).

Although this research suggests that people may use power when it is available to them, other research has found that this is not equally true for all people—still another case of a person-situation interaction. Serena Chen and her colleagues (Chen, Lee-Chai, & Bargh, 2001) found that students who had been classified as more self-oriented (in the sense that they considered relationships in terms of what they could and should get out of them for themselves) were more likely to misuse their power, whereas students who were classified as other-oriented were more likely to use their power to help others

Leaders and Leadership

One type of person who has power over others, in the sense that the person is able to influence them, is leaders. Leaders are in a position in which they can exert leadership, which is the ability to direct or inspire others to achieve goals (Chemers, 2001; Hogg, 2010). Leaders have many different influence techniques at their disposal: In some cases they may give commands and enforce them with reward or coercive power, resulting in public compliance with the commands. In other cases they may rely on well-reasoned technical arguments or inspirational appeals, making use of legitimate, referent, or expert power, with the goal of creating private acceptance and leading their followers to achieve. Leadership is a classic example of the combined effects of the person and the social situation.

Let’s consider first the person part of the equation and then turn to consider how the person and the social situation work together to create effective leadership.

Personality and Leadership

One approach to understanding leadership is to focus on person variables. Personality theories of leadership are explanations of leadership based on the idea that some people are simply “natural leaders” because they possess personality characteristics that make them effective (Zaccaro, 2007). One personality variable that is associated with effective leadership is intelligence. Being intelligent improves leadership, as long as the leader is able to communicate in a way that is easily understood by his or her followers (Simonton, 1994, 1995). Other research has found that a leader’s social skills, such as the ability to accurately perceive the needs and goals of the group members, are also important to effective leadership. People who are more sociable, and therefore better able to communicate with others, tend to make good leaders (Kenny & Zaccaro, 1983; Sorrentino & Boutillier, 1975).

Other variables that relate to leadership effectiveness include verbal skills, creativity, self-confidence, emotional stability, conscientiousness, and agreeableness (Cronshaw & Lord, 1987; Judge, Bono, Ilies, & Gerhardt, 2002; Yukl, 2002). And of course the individual’s skills at the task at hand are important. Leaders who have expertise in the area of their leadership will be more effective than those who do not. Because so many characteristics seem to be related to leadership skills, some researchers have attempted to account for leadership not in terms of individual traits but in terms of a package of traits that successful leaders seem to have. Some have considered this in terms of charisma (Beyer, 1999; Conger & Kanungo, 1998). Charismatic leaders are leaders who are enthusiastic, committed, and self-confident; who tend to talk about the importance of group goals at a broad level; and who make personal sacrifices for the group . Charismatic leaders express views that support and validate existing group norms but that also contain a vision of what the group could or should be. Charismatic leaders use their referent power to motivate, uplift, and inspire others. And research has found a positive relationship between a leader’s charisma and effective leadership performance (Simonton, 1988).

Another trait-based approach to leadership is based on the idea that leaders take either transactional or transformational leadership styles with their subordinates (Avolio & Yammarino, 2003; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, 1990). Transactional leaders are the more regular leaders who work with their subordinates to help them understand what is required of them and to get the job done . Transformational leaders, on the other hand, are more like charismatic leaders—they have a vision of where the group is going and attempt to stimulate and inspire their workers to move beyond their present status and to create a new and better future . Transformational leaders are those who can reconfigure or transform the group’s norms (Reicher & Hopkins, 2003).

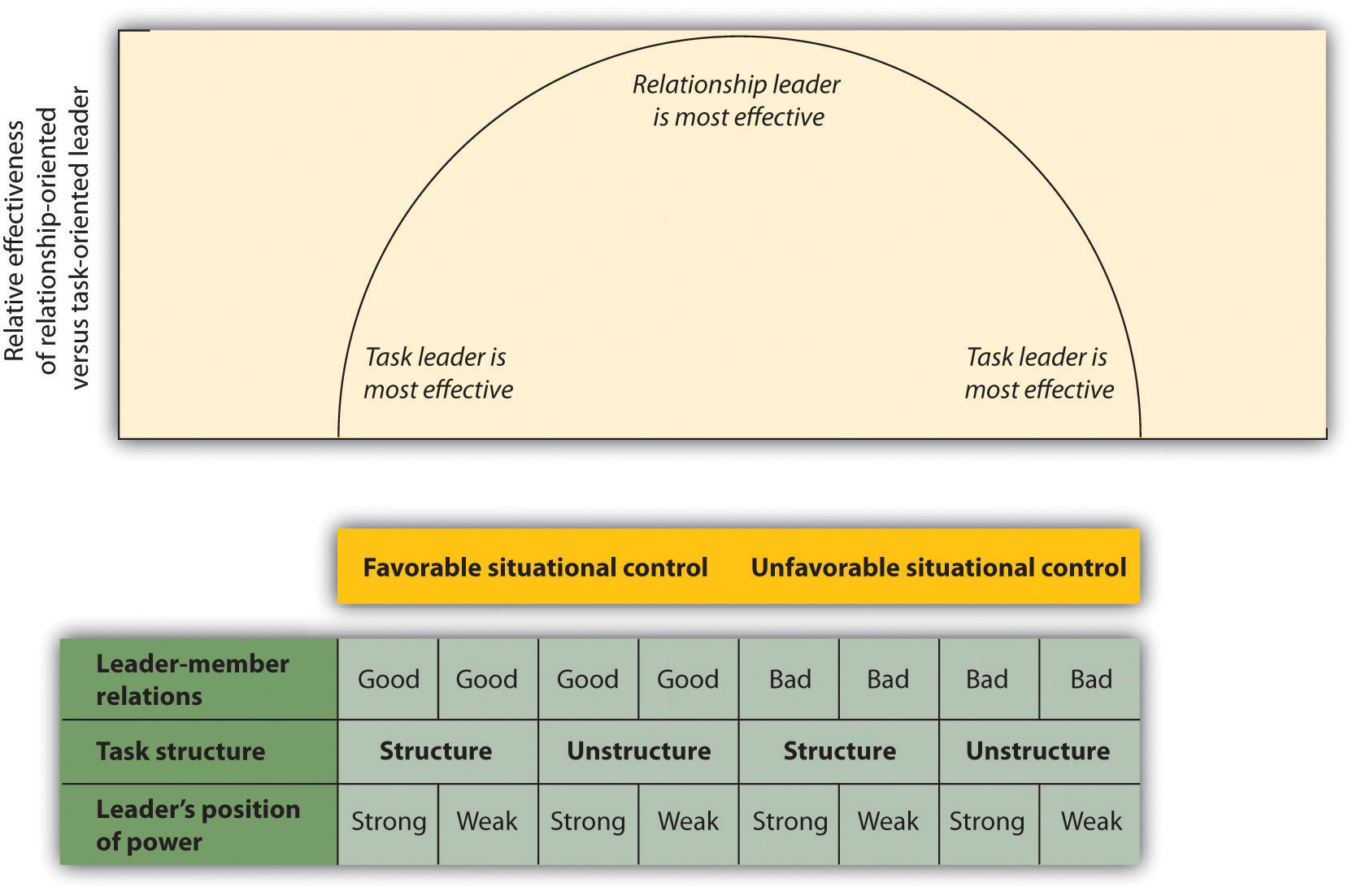

Leadership as an Interaction between the Person and the Situation

Even though there appears to be at least some personality traits that relate to leadership ability, the most important approaches to understanding leadership take into consideration both the personality characteristics of the leader and the situation in which the leader is operating. In some cases, the situation itself is important. For instance, although Winston Churchill is now regarded as having been one of the world’s greatest political leaders ever, he was not a particularly popular figure in Great Britain prior to World War II. However, against the backdrop of the threat posed by Nazi Germany, his defiant and stubborn nature provided just the inspiration many sought. This is a classic example of how a situation can influence the perceptions of a leader’s skill. In other cases, however, both the situation and the person are critical.