- Insights blog

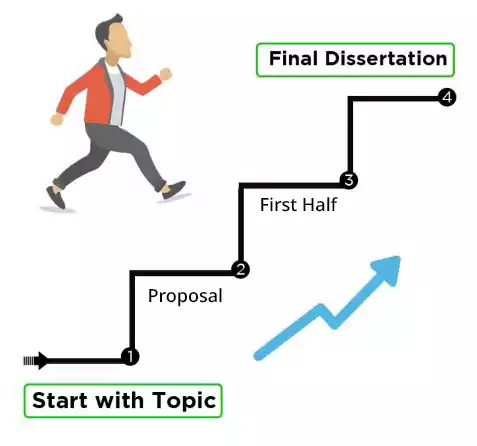

How to publish your research

A step-by-step guide to getting published.

Publishing your research is an important step in your academic career. While there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach, this guide is designed to take you through the typical steps in publishing a research paper.

Discover how to get your paper published, from choosing the right journal and understanding what a peer reviewed article is, to responding to reviewers and navigating the production process.

Step 1: Choosing a journal

Choosing which journal to publish your research paper in is one of the most significant decisions you have to make as a researcher. Where you decide to submit your work can make a big difference to the reach and impact your research has.

It’s important to take your time to consider your options carefully and analyze each aspect of journal submission – from shortlisting titles to your preferred method of publication, for example open access .

Don’t forget to think about publishing options beyond the traditional journals format – for example, open research platform F1000Research , which offers rapid, open publication for a wide range of outputs.

Why choose your target journal before you start writing?

The first step in publishing a research paper should always be selecting the journal you want to publish in. Choosing your target journal before you start writing means you can tailor your work to build on research that’s already been published in that journal. This can help editors to see how a paper adds to the ‘conversation’ in their journal.

In addition, many journals only accept specific manuscript formats of article. So, by choosing a journal before you start, you can write your article to their specifications and audience, and ultimately improve your chances of acceptance.

To save time and for peace of mind, you can consider using manuscript formatting experts while you focus on your research.

How to select the journal to publish your research in

Choosing which journal to publish your research in can seem like an overwhelming task. So, for all the details of how to navigate this important step in publishing your research paper, take a look at our choosing a journal guide . This will take you through the selection process, from understanding the aims and scope of the journals you’re interested in to making sure you choose a trustworthy journal.

Don’t forget to explore our Journal Suggester to see which Taylor & Francis journals could be right for your research.

Go to guidance on choosing a journal

Step 2: Writing your paper

Writing an effective, compelling research paper is vital to getting your research published. But if you’re new to putting together academic papers, it can feel daunting to start from scratch.

The good news is that if you’ve chosen the journal you want to publish in, you’ll have lots of examples already published in that journal to base your own paper on. We’ve gathered advice on every aspect of writing your paper, to make sure you get off to a great start.

How to write your paper

How you write your paper will depend on your chosen journal, your subject area, and the type of paper you’re writing. Everything from the style and structure you choose to the audience you should have in mind while writing will differ, so it’s important to think about these things before you get stuck in.

Our writing your paper guidance will take you through everything you need to know to put together your research article and prepare it for submission. This includes getting to know your target journal, understanding your audiences, and how to choose appropriate keywords.

You can also use this guide to take you through your research publication journey .

You should also make sure you’re aware of all the Editorial Policies for the journal you plan to submit to. Don’t forget that you can contact our editing services to help you refine your manuscript.

Discover advice and guidance for writing your paper

Step 3: Making your submission

Once you’ve chosen the right journal and written your manuscript, the next step in publishing your research paper is to make your submission .

Each journal will have specific submission requirements, so make sure you visit Taylor & Francis Online and carefully check through the instructions for authors for your chosen journal.

How to submit your manuscript

To submit your manuscript you’ll need to ensure that you’ve gone through all the steps in our making your submission guide. This includes thoroughly understanding your chosen journal’s instructions for authors, writing an effective cover letter, navigating the journal’s submission system, and making sure your research data is prepared as required.

You can also improve your submission experience with our guide to avoid obstacles and complete a seamless submission.

To make sure you’ve covered everything before you hit ‘submit’ you can also take a look at our ‘ready to submit’ checklist (don’t forget, you should only submit to one journal at a time).

Understand the process of making your submission

Step 4: Navigating the peer review process

Now you’ve submitted your manuscript, you need to get to grips with one of the most important parts of publishing your research paper – the peer review process .

What is peer review?

Peer review is the independent assessment of your research article by independent experts in your field. Reviewers, also sometimes called ‘referees’, are asked to judge the validity, significance, and originality of your work.

This process ensures that a peer-reviewed article has been through a rigorous process to make sure the methodology is sound, the work can be replicated, and it fits with the aims and scope of the journal that is considering it for publication. It acts as an important form of quality control for research papers.

Peer review is also a very useful source of feedback, helping you to improve your paper before it’s published. It is intended to be a collaborative process, where authors engage in a dialogue with their peers and receive constructive feedback and support to advance their work.

Almost all research articles go through peer review, although in some cases the journal may operate post-publication peer review, which means that reviews and reader comments are invited after the paper is published.

If you’ll like to feel more confident before getting your work peer reviewed by the journal, you may want to consider using an in-depth technical review service from experts.

Understanding peer review

Peer review can be a complex process to get your head around. That’s why we’ve put together a comprehensive guide to understanding peer review . This explains everything from the many different types of peer review to the step-by-step peer review process and how to revise your manuscript. It also has helpful advice on what to do if your manuscript is rejected.

Visit our peer review guide for authors

Step 5: The production process

If your paper is accepted for publication, it will then head into production . At this stage of the process, the paper will be prepared for publishing in your chosen journal.

A lot of the work to produce the final version of your paper will be done by the journal production team, but your input will be required at various stages of the process.

What do you need to do during production?

During production, you’ll have a variety of tasks to complete and decisions to make. For example, you’ll need to check and correct proofs of your article and consider whether or not you want to produce a video abstract to accompany it.

Take a look at our guide to the production process to find out what you’ll need to do in this final step to getting your research published.

Your research is published – now what?

You’ve successfully navigated publishing a research paper – congratulations! But the process doesn’t stop there. Now your research is published in a journal for the world to see, you’ll need to know how to access your article and make sure it has an impact .

Here’s a quick tip on how to boost your research impact by investing in making your accomplishments stand out.

Below you’ll find helpful tips and post-publication support. From how to communicate about your research to how to request corrections or translations.

How to access your published article

When you publish with Taylor & Francis, you’ll have access to a new section on Taylor & Francis Online called Authored Works . This will give you and all other named authors perpetual access to your article, regardless of whether or not you have a subscription to the journal you have published in.

You can also order print copies of your article .

How to make sure your research has an impact

Taking the time to make sure your research has an impact can help drive your career progression, build your networks, and secure funding for new research. So, it’s worth investing in.

Creating a real impact with your work can be a challenging and time-consuming task, which can feel difficult to fit into an already demanding academic career.

To help you understand what impact means for you and your work, take a look at our guide to research impact . It covers why impact is important, the different types of impact you can have, how to achieve impact – including tips on communicating with a variety of audiences – and how to measure your success.

Keeping track of your article’s progress

Through your Authored Works access , you’ll be able to get real-time insights about your article, such as views, downloads and citation numbers.

In addition, when you publish an article with us, you’ll be offered the option to sign up for email updates. These emails will be sent to you three, six and twelve months after your article is published to let you know how many views and citations the article has had.

Corrections and translations of published articles

Sometimes after an article has been published it may be necessary to make a change to the Version of Record . Take a look at our dedicated guide to corrections, expressions of concern, retractions and removals to find out more.

You may also be interested in translating your article into another language. If that’s the case, take a look at our information on article translations .

Go to your guide on moving through production

Explore related posts

Insights topic: Get published

Use a trusted editing service to help you get published

5 practical tips for writing an academic article

5 ways to avoid the wrong journal and find the right one

Publishing in a scholarly journal: Part one, the publishing process

As a psychology student or early career psychologist, you might be thinking about publishing your first paper in a scholarly journal. There are several important steps and points to consider as you embark on your publishing journey. Not sure where to start? We’ve got you covered!

Recognizing that not all young academics get all of their questions about publication answered in their respective training programs, we crowdsourced from trainees and early career psychologists using an anonymous Twitter poll and direct solicitation from various students and colleagues known to the authors, this three-part article series includes frequently asked questions about the publication process with answers from the Editor-in-Chief of Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology ( ECP ), William Stoops, the Associate Editor of ECP , Raina Pang, and a past ECP Editorial Fellow, Daniel Bradford. Part one focuses on crucial publishing insights for future authors; part two examines the role of the editorial board; and part three sheds light on peer review.

Choosing a journal

How does one choose a journal in which to publish and what factors (impact factor, journal content) should be considered?

In general, the most important factor to consider when choosing where to submit your article is the fit of the manuscript to the scope and profile of the journal; Aside from the quality of the science and writing, this is the largest factor that will determine whether a manuscript is accepted to a journal. To determine fit, one should examine the journal description, usually found on the journal website.

Additionally, it is helpful to browse the journal to see whether it has published articles on the same topic and with similar methods to the manuscript you are submitting.

In addition to the above, you may also consider online search engines, which can help generate a list of journals that may be appropriate for the manuscript being submitted:

- JournalFinder

- Springer Nature: Journal suggester

- Enago’s Open Access Journal Finder

- Journal/Author Name Estimator

Can you submit a paper to multiple journals at once?

No. Submitting a paper to multiple journals at once contravenes publishing guidelines and presents serious ethical concerns.

Is there a uniform format that I should submit my manuscript in?

Make sure to carefully read the manuscript submission instructions available on every journal’s webpage. Although there are certain rules that most journals follow (e.g. formatting in APA Style), each journal provides specific guidelines about certain aspects, for example the information that must be included within the manuscript.

What’s a predatory journal?

A predatory journal is a counterfeit publication that imitates that of a legitimate, respected publisher. Predatory publishers use various techniques to trick scholars into submitting their article for publication. A predatory publisher will usually solicit articles via email, emphasizing a publishing fee and touting a quick turnaround that often omits peer review.

Although the publishing fee is a red flag when it comes to identifying a predatory journal, not all journals that charge a publishing fee are predatory (see next question for more information). For tips on how to identify a predatory journal, see the following resources:

- Scholars beware

- How to avoid predatory publishers

Publishing fees

Does it usually cost money to publish?

It’s important to note that many journals do not charge the author(s) or their institution to publish an article. There are exceptions, however.

Some journals may charge a fee for publishing the article in a particular format. For example, some authors prefer or require their figures to be printed in color. Because printing in color costs more to the publisher, some journals may require a fee for each figure to be printed in color. Other journals may print one color figure for free, but charge for every additional color figure.

An increasing number of journals are also adding open access options which, when chosen, require fees paid by the author or their institution. Further, some reputable journals have recently gone entirely open access and thus require a fee to publish (the fee varies by journal). Open access journals are free to read for all and do not receive revenue from journal subscriptions—therefore, in many cases, an article publishing fee is charged to offset the cost of publishing (e.g., peer review management, production costs).

For example, APA’s open access journal Technology, Mind, and Behavior charges a $1,200 article processing charge (APC), however an author may apply for an APC waiver if they are unable to pay via grant, institutional funding, or by other means outlined on the journal website.

As such, it is important to recognize that journals charging a fee are not necessarily “predatory”—it’s crucial to consider other factors to figure out the legitimacy of the publication.

What is the difference between an open access journal and the open science movement?

Open access is a publishing model in which the author pays a fee to publish; the reader is able to access the article for free. Some journals are entirely open access, while others are “hybrid”—providing both a subscription as well as an open access publishing option.

Open science , on the other hand, is a movement towards increased transparency in publishing. It goes beyond open access, offering guidelines on the type of information that authors should include in their manuscript: for example, APA Style JARS provide guidelines for the details that authors should include in their methods section. Open science initiatives include data sharing, preregistration, preprints, registered reports, and more. The goals of open science initiatives are to increase openness and collaboration, and to improve reproducibility of science and research discovery.

Licensing and copyright

How does licensing and copyright work?

Authors usually own the copyright of their original work and are free to share, without limitation, any version of their articles prior to the final text (after the journal proofing / copy editing process). However, licensing of article versions and individual publisher stances on sharing of accepted articles vary and change frequently. Fortunately, there are many resources to help authors keep track of individual policies. For example, the Sherpa Romeo website includes a conveniently searchable tool of journals’ copyright and open access policies on a journal-by-journal basis.

Publishing tips

Expert insights on key topics and best practices in publishing.

Read insights

- APA Journals ™ Publishing Resource Center

- Author resource center

- Reviewer Resource Center

- Editor resource center

- APA and Affiliated Journals

APA Publishing Insider

APA Publishing Insider is a free monthly newsletter with tips on APA Style, open science initiatives, active calls for papers, research summaries, and more.

Contact Journals

Unfortunately we don't fully support your browser. If you have the option to, please upgrade to a newer version or use Mozilla Firefox , Microsoft Edge , Google Chrome , or Safari 14 or newer. If you are unable to, and need support, please send us your feedback .

We'd appreciate your feedback. Tell us what you think! opens in new tab/window

7 steps to publishing in a scientific journal

April 5, 2021 | 10 min read

By Aijaz Shaikh, PhD

Before you hit “submit,” here’s a checklist (and pitfalls to avoid)

As scholars, we strive to do high-quality research that will advance science. We come up with what we believe are unique hypotheses, base our work on robust data and use an appropriate research methodology. As we write up our findings, we aim to provide theoretical insight, and share theoretical and practical implications about our work. Then we submit our manuscript for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. For many, this is the hardest part of research. In my seven years of research and teaching, I have observed several shortcomings in the manuscript preparation and submission process that often lead to research being rejected for publication. Being aware of these shortcomings will increase your chances of having your manuscript published and also boost your research profile and career progression.

Dr Aijaz Shaikh gives a presentation.

In this article, intended for doctoral students and other young scholars, I identify common pitfalls and offer helpful solutions to prepare more impactful papers. While there are several types of research articles, such as short communications, review papers and so forth, these guidelines focus on preparing a full article (including a literature review), whether based on qualitative or quantitative methodology, from the perspective of the management, education, information sciences and social sciences disciplines.

Writing for academic journals is a highly competitive activity, and it’s important to understand that there could be several reasons behind a rejection. Furthermore, the journal peer-review process is an essential element of publication because no writer could identify and address all potential issues with a manuscript.

1. Do not rush submitting your article for publication.

In my first article for Elsevier Connect – “Five secrets to surviving (and thriving in) a PhD program” – I emphasized that scholars should start writing during the early stages of your research or doctoral study career. This secret does not entail submitting your manuscript for publication the moment you have crafted its conclusion. Authors sometimes rely on the fact that they will always have an opportunity to address their work’s shortcomings after the feedback received from the journal editor and reviewers has identified them.

A proactive approach and attitude will reduce the chance of rejection and disappointment. In my opinion, a logical flow of activities dominates every research activity and should be followed for preparing a manuscript as well. Such activities include carefully re-reading your manuscript at different times and perhaps at different places. Re-reading is essential in the research field and helps identify the most common problems and shortcomings in the manuscript, which might otherwise be overlooked. Second, I find it very helpful to share my manuscripts with my colleagues and other researchers in my network and to request their feedback. In doing so, I highlight any sections of the manuscript that I would like reviewers to be absolutely clear on.

2. Select an appropriate publication outlet.

I also ask colleagues about the most appropriate journal to submit my manuscript to; finding the right journal for your article can dramatically improve the chances of acceptance and ensure it reaches your target audience.

Elsevier provides an innovative Journal Finder opens in new tab/window search facility on its website. Authors enter the article title, a brief abstract and the field of research to get a list of the most appropriate journals for their article. For a full discussion of how to select an appropriate journal see Knight and Steinbach (2008).

Less experienced scholars sometimes choose to submit their research work to two or more journals at the same time. Research ethics and policies of all scholarly journals suggest that authors should submit a manuscript to only one journal at a time. Doing otherwise can cause embarrassment and lead to copyright problems for the author, the university employer and the journals involved.

3. Read the aims and scope and author guidelines of your target journal carefully.

Once you have read and re-read your manuscript carefully several times, received feedback from your colleagues, and identified a target journal, the next important step is to read the aims and scope of the journals in your target research area. Doing so will improve the chances of having your manuscript accepted for publishing. Another important step is to download and absorb the author guidelines and ensure your manuscript conforms to them. Some publishers report that one paper in five does not follow the style and format requirements of the target journal, which might specify requirements for figures, tables and references.

Rejection can come at different times and in different formats. For instance, if your research objective is not in line with the aims and scope of the target journal, or if your manuscript is not structured and formatted according to the target journal layout, or if your manuscript does not have a reasonable chance of being able to satisfy the target journal’s publishing expectations, the manuscript can receive a desk rejection from the editor without being sent out for peer review. Desk rejections can be disheartening for authors, making them feel they have wasted valuable time and might even cause them to lose enthusiasm for their research topic. Sun and Linton (2014), Hierons (2016) and Craig (2010) offer useful discussions on the subject of “desk rejections.”

4. Make a good first impression with your title and abstract.

The title and abstract are incredibly important components of a manuscript as they are the first elements a journal editor sees. I have been fortunate to receive advice from editors and reviewers on my submissions, and feedback from many colleagues at academic conferences, and this is what I’ve learned:

The title should summarize the main theme of the article and reflect your contribution to the theory.

The abstract should be crafted carefully and encompass the aim and scope of the study; the key problem to be addressed and theory; the method used; the data set; key findings; limitations; and implications for theory and practice.

Dr. Angel Borja goes into detail about these components in “ 11 steps to structuring a science paper editors will take seriously .”

Learn more in Elsevier's free Researcher Academy opens in new tab/window

5. Have a professional editing firm copy-edit (not just proofread) your manuscript, including the main text, list of references, tables and figures.

The key characteristic of scientific writing is clarity. Before submitting a manuscript for publication, it is highly advisable to have a professional editing firm copy-edit your manuscript. An article submitted to a peer-reviewed journal will be scrutinized critically by the editorial board before it is selected for peer review. According to a statistic shared by Elsevier, between 30 percent and 50 percent of articles submitted to Elsevier journals are rejected before they even reach the peer-review stage, and one of the top reasons for rejection is poor language. A properly written, edited and presented text will be error free and understandable and will project a professional image that will help ensure your work is taken seriously in the world of publishing. On occasion, the major revisions conducted at the request of a reviewer will necessitate another round of editing. Authors can facilitate the editing of their manuscripts by taking precautions at their end. These include proofreading their own manuscript for accuracy and wordiness (avoid unnecessary or normative descriptions like “it should be noted here” and “the authors believe) and sending it for editing only when it is complete in all respects and ready for publishing. Professional editing companies charge hefty fees, and it is simply not financially viable to have them conduct multiple rounds of editing on your article. Applications like the spelling and grammar checker in Microsoft Word or Grammarly are certainly worth applying to your article, but the benefits of proper editing are undeniable. For more on the difference between proofreading and editing, see the description in Elsevier’s WebShop.

6. Submit a cover letter with the manuscript.

Never underestimate the importance of a cover letter addressed to the editor or editor-in-chief of the target journal. Last year, I attended a conference in Boston. A “meet the editors” session revealed that many submissions do not include a covering letter, but the editors-in-chief present, who represented renewed and ISI-indexed Elsevier journals, argued that the cover letter gives authors an important opportunity to convince them that their research work is worth reviewing.

Accordingly, the content of the cover letter is also worth spending time on. Some inexperienced scholars paste the article’s abstract into their letter thinking it will be sufficient to make the case for publication; it is a practice best avoided. A good cover letter first outlines the main theme of the paper; second, argues the novelty of the paper; and third, justifies the relevance of the manuscript to the target journal. I would suggest limiting the cover letter to half a page. More importantly, peers and colleagues who read the article and provided feedback before the manuscript’s submission should be acknowledged in the cover letter.

7. Address reviewer comments very carefully.

Editors and editors-in-chief usually couch the acceptance of a manuscript as subject to a “revise and resubmit” based on the recommendations provided by the reviewer or reviewers. These revisions may necessitate either major or minor changes in the manuscript. Inexperienced scholars should understand a few key aspects of the revision process. First, it important to address the revisions diligently; second, is imperative to address all the comments received from the reviewers and avoid oversights; third, the resubmission of the revised manuscript must happen by the deadline provided by the journal; fourth, the revision process might comprise multiple rounds. The revision process requires two major documents. The first is the revised manuscript highlighting all the modifications made following the recommendations received from the reviewers. The second is a letter listing the authors’ responses illustrating they have addressed all the concerns of the reviewers and editors. These two documents should be drafted carefully. The authors of the manuscript can agree or disagree with the comments of the reviewers (typically agreement is encouraged) and are not always obliged to implement their recommendations, but they should in all cases provide a well-argued justification for their course of action.

Given the ever increasing number of manuscripts submitted for publication, the process of preparing a manuscript well enough to have it accepted by a journal can be daunting. High-impact journals accept less than 10 percent of the articles submitted to them, although the acceptance ratio for special issues or special topics sections is normally over 40 percent. Scholars might have to resign themselves to having their articles rejected and then reworking them to submit them to a different journal before the manuscript is accepted.

The advice offered here is not exhaustive but it’s also not difficult to implement. These recommendations require proper attention, planning and careful implementation; however, following this advice could help doctoral students and other scholars improve the likelihood of getting their work published, and that is key to having a productive, exciting and rewarding academic career.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Heikki Karjaluoto, Jyväskylä University School of Business and Economics for providing valuable feedback on this article.

Sun, H., & Linton, J. D. (2014).

Structuring papers for success: Making your paper more like a high impact publication than a desk reject opens in new tab/window

Technovation.

Craig, J. B. (2010).

Desk rejection: How to avoid being hit by a returning boomerang opens in new tab/window

Family Business Review

Hierons, R. M. (2016).

The dreaded desk reject opens in new tab/window

, Software Testing, Verification and Reliability .

Borja, A (2014):

11 steps to structuring a science paper editors will take seriously

Elsevier Connect

Knight, L. V., & Steinbach, T. A. (2008).

Selecting an appropriate publication outlet: a comprehensive model of journal selection criteria for researchers in a broad range of academic disciplines opens in new tab/window

, International Journal of Doctoral Studies .

Tewin, K. (2015).

How to Better Proofread An Article in 6 Simple Steps opens in new tab/window ,

Day, R, & Gastel, B: How to write and publish a scientific paper. Cambridge University Press (2012)

Contributor

Aijaz shaikh, phd.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Hum Reprod Sci

- v.10(1); Jan-Mar 2017

Preparing and Publishing a Scientific Manuscript

Padma r. jirge.

Department of Reproductive Medicine, Sushrut Assisted Conception Clinic Shreyas Hospital, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India

Publishing original research in a peer-reviewed and indexed journal is an important milestone for a scientist or a clinician. It is an important parameter to assess academic achievements. However, technical and language barriers may prevent many enthusiasts from ever publishing. This review highlights the important preparatory steps for creating a good manuscript and the most widely used IMRaD (Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, and Discussion) method for writing a good manuscript. It also provides a brief overview of the submission and review process of a manuscript for publishing in a biomedical journal.

B ACKGROUND

T he publication of original research in a peer-reviewed and indexed journal is the ultimate and most important step toward the recognition of any scientific work. However, the process starts long before the write-up of a manuscript. The journal in which the author wishes to publish his/her work should be chosen at the time of conceptualization of the scientific work based on the expected readership.

The journals do provide information on the “scope of the journal,” which specifies the scientific areas relevant for publication in the journal, and “instructions to authors,” which need to be adhered to while preparing a manuscript.

The publication of scientific work has become mandatory for scientists or specialists holding academic affiliations, and it is now desirable even at an undergraduate level. Despite a plethora of forums for presenting the original research work, very little of it ever gets published in a scientific journal, and even if it does, the manuscripts are usually from the same few institutions.[ 1 , 2 ] It serves the purpose of academic recognition; and certain publications may even contribute to shaping various national policies. An academic appointment, suitable infrastructure, and access to peer-reviewed journals are considered as the facilitators for publishing.[ 3 ]

The lack of technical and writing skills, institutional hurdles, and time constraints are considered as the major hurdles for any scientific publication.[ 3 ] In addition, the majority of clinicians in India are involved in providing healthcare in the private sector in individually owned hospitals or those governed by small groups of doctors. This necessitates performing a multitude of tasks apart from providing core clinical care and, hence, poses an additional limiting factor because of the long and irregular working hours.

It is extremely challenging to dedicate some time for research and writing in such a scenario. However, it is a loss to science if this group of skilled clinicians does not contribute to medical literature.

Maintaining the ethics and science of research and understanding the norms of preparing a manuscript are very important in improving the quality and relevance of clinical research in our country. This article brings together various aspects to be borne in mind while creating a manuscript suitable for publication. The inputs provided are relevant to all those interested, irrespective of whether they have an academic or institutional affiliation. While the prospect of becoming an author of a published scientific work is exciting, it is important to be prepared for minor or major revisions in the original article and even rejection. However, persevering in this endeavor may help preserving one’s work and contribute to the promotion of science.[ 4 , 5 ]

Important considerations for writing a manuscript include the following:

- (1) Conceptualization of a clinically relevant scientific work.

- (2) Choosing an appropriate journal and an alternative one.

- (3) Familiarizing with instructions to authors.

- (4) Coordination and well-defined task delegation within the team and involvement of a biostatistician from the conception of the study.

- (5) Preparing a skeletal framework for writing the manuscript.

- (6) Delegating time for thinking and writing at regular intervals.

S TEPS I NVOLVED IN M ANUSCRIPT P REPARATION

A manuscript should both be informative and readable. Even though the concept is clear in the authors’ mind, it is important to remember that they are introducing some new work for the readers, and, hence, appropriate organization of the manuscript is necessary to make the purpose and importance of the work clear to the readers.

- (1) Choosing the appropriate journal for publication : The preferred choice of journal should be one of the first steps to be considered, as mentioned earlier. The guidelines for authors may change with time and, hence, should be referred to at regular intervals and conformed to. The choice of journal principally depends on the target readers, and it may be necessary to have one or more journals in mind in case of nonacceptance from the journal of first choice. A journal’s impact factor is to be considered while choosing an appropriate journal.

Majority of the biomedical journals with good impact factor have specific authorship criteria.[ 8 ] This prevents problems related to ghost authorship and honorary authorship. Ghost authorship refers to a scenario wherein an author’s name is omitted to hide financial relationships with private companies; honorary authorship is naming someone who has not made substantial contribution to the work, either due to pressure from colleagues or to improve the chances of publication.[ 9 ]

Most of the journals conform to the authorship criteria defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.[ 10 ] They are listed as the following:

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; ANDDrafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; ANDFinal approval of the version to be published; ANDAgreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Some journals require authors to declare their contributions to the research work and manuscript preparation. This helps to prevent honorary and ghost authorship and encourages authors to be more honest and accountable.[ 11 ]

Keywords : are mentioned at the bottom of the Abstract section. These words denote the important aspects of the manuscript and help identify the manuscripts by electronic search engines. Most of the journals specify the number of keywords required, usually between 4 and 8. They need to be simple and specific to the manuscript; a good title contains majority of the keywords.

The general flow of the manuscript follows an IMRaD (Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, and Discussion) structure. Even though this has been recommended since the early 20 th century, most of the authors started following it since the 1970s.[ 13 ]

Important components of the Introduction section

A common error while writing an introduction is an attempt to review the entire evidence available on the topic. This becomes confusing to the reader, and the purpose and importance of the study in question gets submerged in the plethora of information provided. Issues mentioned in the Introduction section will need to be addressed in the Discussion section, and it is important to avoid repetitions and overlapping. Some may prefer to write the Introduction section after preparing the draft of the Materials and Methods and Results sections.

The last paragraph in the Introduction section defines the aim of the study or the study question using active verbs. If there is more than one aim for the study, specify the primary aim and address the secondary aims in a separate sentence. It is recommended that the Introduction section should not occupy more than 10–15% of the entire text.[ 14 ]

This is followed by a detailed description of the study protocol. At times, some of the methods used may be very elaborate and not very relevant to majority of the readers, for example, if polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is used for diagnosis, the type of PCR performed should be mentioned in this section, but the entire procedure need not be elaborated in the “methods” section. Either a relevant reference can be provided or the procedural details can be given online as supplemental data.

It is important to mention both the generic and brand names of all the drugs used along with the name of the manufacturer and the place of manufacturing. Similarly, all the hematological, biochemical, hormonal assays, and radiological investigations performed should provide the specifications of the equipment used and its manufacturer’s details. For many biochemical and endocrine parameters, it is preferred that the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation are provided. In addition, the standard units of measurements and the internationally accepted abbreviations should be used.[ 18 ]

There are online guidelines available to maintain uniformity in reporting the different types of studies such as Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for randomized controlled trials, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) for observational studies, and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for systematic reviews.[ 19 ] Adherence to these guidelines improves the clarity and completeness of reporting.

Statistical analysis : One of the most important deterrents for publishing clinical research is the inability to choose and perform appropriate statistical analysis. With the availability of various user-friendly software systems, an increasing number of the researchers are comfortable performing complex analyses without additional assistance. However, it is still a common practice to involve biostatisticians for this purpose. Coordination between the clinicians and biostatisticians is very important for sample size calculation, creation of a proper data set, and its subsequent analysis. It is important to use the appropriate statistical methodologies for a more complete representation of the data to improve the quality of a manuscript.[ 20 ] It may be helpful to refer to a recent review of the most widely used statistical analyses and their application in clinical research for a better data presentation.[ 20 ] There is some evidence that structured training involving data analysis, manuscript writing, and submission to indexed journals improves the quality of submitted manuscripts even in a low-resource setting.[ 21 ] Short, online certificate courses on biostatistics are available free of cost from many universities across the globe. The important aspects regarding the Materials and Methods section are summarized in Table 2 .

Important components of the Materials and Methods section

The results of the study are summarized in the form of tables and figures. Journals may have limitations on the number of figures and tables, as well as the rows and columns in tables. The text should only highlight the findings recorded in the tables and figures and should not repeat every detail.[ 16 ] Primary analysis should be presented in a separate paragraph. Any secondary analysis performed in view of the results seen in the primary analysis should be mentioned separately [ Table 3 ].

Important components of the Results section

When comparing two groups, it is a good practice to mention the data pertaining to the study group followed by that of the control group and to maintain the same order throughout the section. No adjectives should be used while comparing, except for the statistical significance of the findings. The Results section is written in the past tense, and the numerical values should be presented with a maximum of one decimal place.

Statistical significance as shown by P-value, if accompanied by odds ratio and 95% confidence interval gives important information of direction and size of treatment effect. The measures of central tendencies should be followed by the appropriate measures of variability (mean and standard deviation; median and interquartile range). Relative measures should be accompanied by absolute values (percentage and actual value).[ 22 ] The interpretation of results solely based on bar diagrams or line graphs could be misleading, and a more complete data may be presented in the form of box plots or scatter plots.[ 20 ]

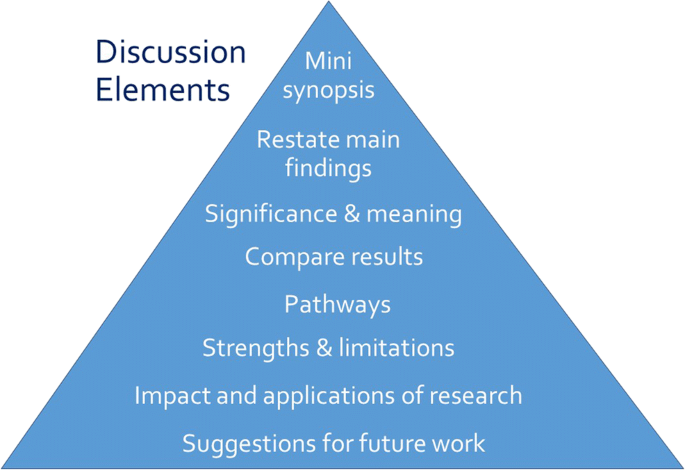

The strengths and weaknesses of the study should be discussed in a separate paragraph. This makes way for implications for clinical practice and future research.[ 16 , 23 ]

The section ends with a conclusion of not more than one to two sentences. The Conclusion section summarizes the study findings in the context of evidence in the field. The important components of the Discussion section are summarized in Table 4 [ Figure 1 ].

Important components of the Discussion section

The hourglass structure of the Introduction and Discussion sections

A referencing tool such as EndNote™ may be used to store and organize the references. The references at the end of the manuscript need to be listed in a manner specified by the journal. The common styles used are Vancouver, Harvard, APA, etc.[ 24 ] Despite continued efforts, standardization to one global format has not yet become a reality.[ 25 ]

It is important to understand the evidence in the referenced articles to write meaningful Introduction and Discussion sections. Online search engines such as Pubmed, Medline, and Scopus are some of the sources that provide abstracts from indexed journals. However, a full-text article may not always be available unless one has subscription for the journals. Those with institutional attachments, authors, and even the research division of pharmaceutical companies may be unconventional but helpful sources for procuring full-text articles. Individual articles can be purchased from certain journals as well.

- (9) Acknowledgements : This section follows the Conclusion section. People who have helped in various aspects of the concerned research work, statistical analysis, or manuscript preparation, but do not qualify to be authors for the study, are acknowledged, preferably with their academic affiliations.[ 26 ]

The aforementioned section provides the general guidelines for preparing a good manuscript. However, an exhaustive list of available guidelines and other resources to facilitate good research reporting are provided by the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research network ( http://www.equator-network.org ).

A DDITIONAL F ACTORS I NFLUENCING THE M ANUSCRIPT Q UALITY

- (1) Plagiarism : Plagiarism is a serious threat to scientific publications and is described by the office of Research Integrity as “theft or misappropriation of intellectual property and the substantial unattributed textual copying of another’s work and the representation of them as one’s own original work.” The primary responsibility of preventing plagiarism lies with the authors. It is important to develop the skill of writing any manuscript in one’s own words and when quoting available evidence, substantiate with appropriate references. However, the use of plagiarism detection tools and a critical analysis by the editorial team prior to submitting an article for peer review are also equally important to prevent this menace.[ 29 ] The consequences of plagiarism could range from disciplinary charges such as retraction of the article to criminal charges.[ 30 ]

- (2) Language : One of the important limitations to publication is the problem of writing in English. This can be minimized by seeking help from colleagues or using the language editing service provided by many of the journals.

- (3) Professional medical writing support : In recent years, it is acknowledged that the lack of time and linguistic constraints prevent some of the good work from being published. Hence, the role of professional medical writing support is being critically evaluated. Declared professional medical writing support is found to be associated with more complete reporting of clinical trial results and higher quality of written English. Medical writing support may play an important role in raising the quality of clinical trial reporting.[ 31 ] The role of professional medical writers should be acknowledged in the Acknowledgements section.[ 32 ]

S UBMISSION TO J OURNALS AND R EVIEWING P ROCESS

The submission of manuscripts is now exclusively an online exercise. The basic model of submission in any journal comprises the following: the title file or first page file, article file, image files, videos, charts, tables, figures, and copyright/consent forms. It is important to keep all the files ready in a folder before starting the submission process. When submitting images, it is important to have good quality, well-focused images with good resolution.[ 33 ] Some journals may offer the choice of selecting preferred reviewers to the authors and hence, one must be prepared for this. Once the manuscript is submitted, the status can be periodically checked. With minor variations, a submitted article goes through the following review process: The Editor allocates it to one of the editorial team members who checks for the suitability for publication in the journal. It is checked for plagiarism as well at this stage. The article then goes for peer review to two to three reviewers. The review process may take 4–6 weeks, at the end of which, the reviewers submit their remarks, and “article decision” is made, which could be an advice for minor/major revisions, rewriting the whole manuscript for specific reasons, acceptance without any changes (very rare), or rejection. It is important to take into consideration all the comments of the reviewers and incorporate the necessary changes in the manuscript before resubmitting. However, if the manuscript is rejected, revise to incorporate the valid suggestions given by the reviewers and consider submitting to another journal in the field. This should be effected without delay overcoming the disappointment so that the research still remains valid in the context of time.

P REDATORY J OURNALS

Some of the well-known journals provide an “open access” option to the authors, wherein if the manuscript is published, it is accessible to all the readers online free of cost. However, the authors need to pay a certain fee to make their manuscript an open access article. In addition, some of the well-known journals published by reputed publishers such as BioMed Central (BMC) and Public Library of Science (PLoS) have online “open access” journals, where the manuscripts are published for a fee but are subjected to the conventional scrutiny process, and the readers can access the full-text article.[ 34 ] The Directory of Open Access Journals, http://doaj.org , is an online directory that indexes and provides access to high-quality, open access, peer-reviewed journals. However, many online open access journals are mushrooming, which provide a legitimate face for an illegitimate publication process lacking basic industry standards, sound peer review practices, and solid basis in publication ethics. Such journals are known as “predatory journals.”[ 35 ] The pressure of needing to have scientific publications and the lack of knowledge regarding predatory journals may encourage authors to submit their articles to such journals. Currently, it is not easy to identify predatory journals, and authors should seek such information proactively from mentors, journal websites, and recent and relevant published literature. In addition, editorial oversights (editors and editorial board members), peer review practices, the quality of published articles, indexing, access, citations and ethical practices are important aspects to be considered while choosing an appropriate journal.[ 36 ]

A relevant research hypothesis and research conducted within the ethical framework are of utmost importance for clinical research. The natural progression from here is the manuscript preparation, a daunting process for most of the clinicians involved in clinical research. Choosing a journal that provides an appropriate platform for the manuscript, conforming to the instructions specific for the journal, and following certain simple guidelines can result in successful preparation and publishing of scientific work. Allocating certain time at regular intervals for writing and maintaining discipline and perseverance in this regard are very important prerequisites to achieve the goal of successful publication.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

R EFERENCES

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

How to publish your paper

On this page, journal specific instructions, nature journal pledge to authors, how to publish your research in a nature journal, editorial process, about advance online publication, journals' aop timetable, frequently asked questions.

For more information on how to publish papers in a specific Nature Portfolio title, please visit the author instructions page for the journal that is of interest to you.

Top of page ⤴

Editors of the Nature journals strive to provide authors with an outstandingly efficient, fair and thoughtful submission, peer-review and publishing experience. Authors can expect all manuscripts that are published to be scrutinized for peer-review with the utmost professional rigor and care by expert referees who are selected by the editors for their ability to provide incisive and useful analysis. Editors weigh many factors when choosing content for Nature journals, but they strive to minimize the time taken to make decisions about publication while maintaining the highest possible quality of that decision.

After review, editors work to increase a paper's readability, and thereby its audience, through advice and editing, so that all research is presented in a form that is both readable to those in the field and understandable to scientists outside the immediate discipline. Research is published online without delay through our Advance Online Publication system. Nature journals provide more than 3,000 registered journalists with weekly press releases that mention all research papers to be published. About 800,000 registered users receive e-mailed tables of contents, and many papers are highlighted for the nonspecialist reader on the journal's homepage, contents pages and in News and Views.

Throughout this process, the editors of Nature journals uphold editorial, ethical and scientific standards according to the policies outlined on the author and referee site as well as on our journal websites. We periodically review those policies to ensure that they continue to reflect the needs of the scientific community, and welcome comments and suggestions from scientists, either via the feedback links on the author and referees' website or via our author blog, Nautilus , or peer-review blog, Peer to Peer .

The Nature journals comprise the weekly, multidisciplinary Nature, which publishes research of the highest influence within a discipline that will be of interest to scientists in other fields, and fifteen monthly titles, publishing papers of the highest quality and of exceptional impact: Nature Biotechnology, Nature Cell Biology, Nature Chemical Biology, Nature Chemistry, Nature Climate Change, Nature Communications, Nature Genetics, Nature Geoscience, Nature Immunology, Nature Materials, Nature Medicine, Nature Methods, Nature Nanotechnology, Nature Neuroscience, Nature Photonics, Nature Physics, Nature Protocolsand Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. These journals are international, being published and printed in the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan. See here for more information about the relationship between these journals.

Nature and the Nature monthly journals have Impact Factors that are among the highest in the world. The high prestige of these journals brings many rewards to their authors, but also means that competition for publication is severe, so many submissions have to be declined without peer-review.

The Nature journals differ from most other journals in that they do not have editorial boards, but are instead run by professional editors who consult widely among the scientific community in making decisions about publication of papers. This article is to provide you with an overview of the general editorial processes of these unique journals. Although the journals are broadly similar and share editorial policies , all authors should consult the author information pages of the specific Nature journal before submitting, to obtain detailed information on criteria for publication and manuscript preparation for that journal, as some differences exist.

The following sections summarise the journals' editorial processes and describe how manuscripts are handled by editors between submission and publication. At all stages of the process, you can access the online submission system and find the status of your manuscript.

Presubmission enquiries

Many Nature journals allow researchers to obtain informal feedback from editors before submitting the whole manuscript. This service is intended to save you time — if the editors feel it would not be suitable, you can submit the manuscript to another journal without delay. If you wish to use the presubmission enquiry service, please use the online system of the journal of your choice to send a paragraph explaining the importance of your manuscript, as well as the abstract or summary paragraph with its associated citation list so the editors may judge the manuscript in relation to other related work. The editors will quickly either invite you to submit the whole manuscript (which does not mean any commitment to publication), or will say that it is not suitable for the journal. If you receive a negative response, please do not reply. If you are convinced of the importance of your manuscript despite editors' reservations, you may submit the whole manuscript using the journal's online submission system. The editors can then make a more complete assessment of your work. Note that not all Nature journals offer a presubmission enquiry service.

Initial submission

When you are ready to submit the manuscript, please use the online submission system for the journal concerned. When the journal receives your manuscript, it will be assigned a number and an editor, who reads the manuscript, seeks informal advice from scientific advisors and editorial colleagues, and compares your submission to other recently published papers in the field. If the manuscript seems novel and arresting, and the work described has both immediate and far-reaching implications, the editor will send it out for peer review, usually to two or three independent specialists. However, because the journals can publish only a few of the manuscripts in the field or subfield concerned, many manuscripts have to be declined without peer review even though they may describe solid scientific results.

Transfers between Nature journals

In some cases, an editor is unable to offer publication, but might suggest that the manuscript is more suitable for one of the other Nature journals. If you wish to resubmit your manuscript to the suggested journal, you can simply follow the link provided by the editor to transfer your manuscript and the reviewers' comments to the new journal. This process is entirely in your control: you can choose not to use this service and instead to submit your manuscript to any other Nature or nature research journal, with or without including the reviewers' comments if you wish, using the journal's usual online submission service. For more information, please see the manuscript transfers page .

Peer review

The corresponding author is notified by email when an editor decides to send a manuscript for review. The editors choose referees for their independence, ability to evaluate the technical aspects of the paper fully and fairly, whether they are currently or recently assessing related submissions, and whether they can review the manuscript within the short time requested.

You may suggest referees for your manuscript (including address details), so long as they are independent scientists. These suggestions are often helpful, although they are not always followed. Editors will honour your requests to exclude a limited number of named scientists as reviewers.

Decisions and revisions

If the editor invites you to revise your manuscript, you should include with your resubmitted version a new cover letter that includes a point-by-point response to the reviewers' and editors' comments, including an explanation of how you have altered your manuscript in response to these, and an estimation of the length of the revised version with figures/tables. The decision letter will specify a deadline, and revisions that are returned within this period will retain their original submission date.

Additional supplementary information is published with the online version of your article if the editors and referees have judged that it is essential for the conclusions of the article (for example, a large table of data or the derivation of a model) but of more specialist interest than the rest of the article. Editors encourage authors whose articles describe methods to provide a summary of the method for the print version and to include full details and protocols online. Authors are also encouraged to post the full protocol on Nature Protocols' Protocol Exchange , which as well as a protocols database provides an online forum for readers in the field to add comments, suggestions and refinements to the published protocols.

After acceptance

Your accepted manuscript is prepared for publication by copy editors (also called subeditors), who refine it so that the text and figures are readable and clear to those outside the immediate field; choose keywords to maximize visibility in online searches as well as suitable for indexing services; and ensure that the manuscripts conform to house style. The copy editors are happy to give advice to authors whose native language is not English, and will edit those papers with special care.

After publication

All articles are published in the print edition and, in PDF and HTML format, in the online edition of the journal, in full. Many linking and navigational services are provided with the online (HTML) version of all articles published by the Nature journals.

All articles and contact details of corresponding authors are included in our press release service, which means that your work is drawn to the attention of all the main media organizations in the world, who may choose to feature the work in newspaper and other media reports. Some articles are summarized and highlighted within Nature and Nature Portfolio publications and subject-specific websites.

Journals published by Nature Portfolio do not ask authors for copyright, but instead ask you to sign an exclusive publishing license . This allows you to archive the accepted version of your manuscript six months after publication on your own, your institution's, and your funder's websites.

Disagreements with decisions

If a journal's editors are unable to offer publication of a manuscript and have not invited resubmission, you are strongly advised to submit your manuscript for publication elsewhere. However, if you believe that the editors or reviewers have seriously misunderstood your manuscript, you may write to the editors, explaining the scientific reasons why you believe the decision was incorrect. Please bear in mind that editors prioritise newly submitted manuscripts and manuscripts where resubmission has been invited, so it can take several weeks before letters of disagreement can be answered. During this time, you must not submit your manuscript elsewhere. In the interests of publishing your results without unnecessary delay, we therefore advise you to submit your manuscript to another journal if it has been declined, rather than to spend time on corresponding further with the editors of the declining journal.

Nature journals offer Advance Online Publication (AOP).

We believe that AOP is the best and quickest way to publish high-quality, peer-reviewed research for the benefit of readers and authors. Papers published AOP are the definitive version: they do not change before appearing in print and can be referenced formally as soon as they appear on the journal's AOP website. In addition, Nature publishes some papers each week via an Accelerated Article Preview (AAP) workflow. For these papers, we upload the accepted manuscript to our website as an AAP PDF, without subediting of text, figures or tables, but with some preliminary formatting. AAP papers are clearly indicated by a watermark on each page of the online PDF.

Each journal's website includes an AOP table of contents, in which papers are listed in order of publication date (beginning with the most recent). Each paper carries a digital object identifier (DOI), which serves as a unique electronic identification tag for that paper. As soon as the issue containing the paper is printed, papers will be removed from the AOP table of contents, assigned a page number and transferred to that issue's table of contents on the website. The DOI remains attached to the paper to provide a persistent identifier.

Nature publishes many, but not all, papers AOP, on Mondays and Wednesdays.

For the monthly Nature journals publishing primary research, new articles are uploaded to the AOP section of their web sites once each week. Occasionally, an article may be uploaded on other days.

The monthly Nature Reviews journals also upload new articles to the AOP section of their web sites once each week.

Q. Which articles are published AOP?

A. Original research is published AOP — that is, Articles and Letters, and for the Nature journals that publish them, Brief Communications. Associated News and Views articles may be published with the AOP Article or Letter or when the papers are published in the print/online edition of the journal. Nature occasionally publishes other article types AOP, for example News and Commentaries.

Q. Is the AOP version of the article definitive?

A. Yes. Only the final version of the paper is published AOP, exactly as it will be published in the printed edition. The paper is thus complete in every respect except that instead of having a volume/issue/page number, it has a DOI (digital object identifier). This means that the paper can be referenced as soon as it appears on the AOP site by using the DOI. Nature also publishes some papers each week via an Accelerated Article Preview workflow, where the accepted version of the paper is uploaded as a PDF to our website without subediting of text, figures and tables, but with some preliminary formatting. These papers are clearly identified by a watermark on each page of the PDF.

Q. What is a Digital Object Identifier?

A. The DOI is an international, public, "persistent identifier of intellectual property entities" in the form of a combination of numbers and letters. For Nature Portfolio journals, the DOI is assigned to an item of editorial content, providing a unique and persistent identifier for that item. The DOI system is administered by the International DOI Foundation, a not-for-profit organization. CrossRef, another not-for-profit organization, uses the DOI as a reference linking standard, enables cross-publisher linking, and maintains the lookup system for DOIs. Nature Portfolio is a member of CrossRef.

Q. What do the numbers in the DOI signify?

A. The DOI has two components, a prefix (before the slash) and a suffix (after the slash). The prefix is a DOI resolver server identifer (10) and a unique identifier assigned to the publisher—for example, the identifier for Nature Portfolio is 1038 and the entire DOI prefix for an article published by Nature Portfolio is 10.1038. The suffix is an arbitrary number provided by the publisher. It can be composed of numbers and/or letters and does not necessarily have any systematic significance. Each DOI is registered in a central resolution database that associates it with one or more corresponding web locations (URLs). For example, the DOI 10.1038/ng571 connects to http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng571.

Q. Can I use the DOI in a reference citation?

A. Yes, instead of giving the volume and page number, you can give the paper's DOI at the end of the citation. For example, Nature papers should be cited in the form;

Author(s) Nature advance online publication, day month year (DOI 10.1038/natureXXX).

After print publication, you should give the DOI as well as the print citation, to enable readers to find the paper in print as well as online. For example;

Author(s) Nature volume, page (year); advance online publication, day month year (DOI 10.1038/natureXXX).

Q. How can I use a DOI to find a paper?

A. There are two ways:

- DOIs from other articles can be embedded into the linking coding of an article's reference section. In Nature journals these appear as "|Article|" in the reference sections. When |Article| is clicked, it opens another browser window leading to the entrance page (often the abstract) for another article. Depending on the source of the article, this page can be on the Nature Portfolio's site or a site of another publisher. This service is enabled by CrossRef.

- A DOI can be inserted directly into the browser. For example, for the DOI 10.1038/ng571, typing http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng571 brings up the entrance page of the article.

Q. What is the official publication date?

A. Many journals, and most abstracting and indexing services (including Medline and Thomson-Reuters) cite the print date as the publication date. Publishers usually state both the 'online publication date' and the 'print publication date'. Nature Portfolio publishes both dates for our own papers, in the hope that scientific communities, as well as abstracting and indexing services, will recognize these dates.

We endeavour to include both the online publication date and the usual print citation in reference lists of Nature Portfolio papers, where a paper has been published online before being published in print. Given the use of the DOI in locating an online publication in the future, we encourage authors to use DOIs in reference citations.

For legal purposes (for example, establishing intellectual property rights), we assume that online publication constitutes public disclosure. But this is for the courts to decide; Nature Portfolio's role as a publisher is to provide clear documentation of the publication history, online and in print.

Q. Must I be a subscriber to read AOP articles?

A. Yes. AOP papers are the same as those in the print/online issues: while abstracts are freely available on any Nature Portfolio journal's web site, access to the full-text article requires a paid subscription or a site license.

Q. Does Medline use DOIs?

A. Medline currently captures DOIs with online publication dates in its records, and is developing an enhanced level of support for the DOI system.

Q. Does Thomson-Reuters use DOIs?

A. Thomson Reuters captures DOIs in its records at the same time as the volume/issue/page number. Therefore, it is not using the DOI to capture information before print publication, but rather as an additional piece of metadata.

Q. How does AOP affect the Impact Factor?

A. Impact factors are calculated by Thomson-Reuters. At present, Thomson-Reuters bases its calculations on the date of print publication alone, so until or unless it changes its policy, AOP has no effect on impact factors.

Q. What are the page numbers in PDFs of AOP papers?

A. For convenience, the PDF version of every AOP article is given a temporary pagination, beginning with page 1. This is unrelated to the final pagination in the printed article.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

286k Accesses

19 Citations

706 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

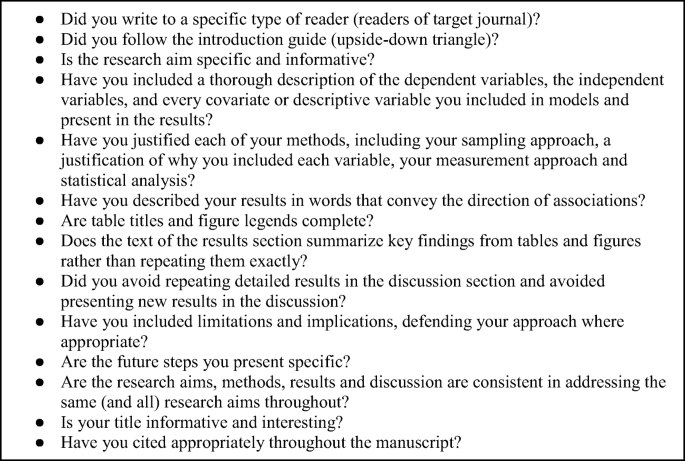

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Choose the Right Journal

The Point Is…to Publish?

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

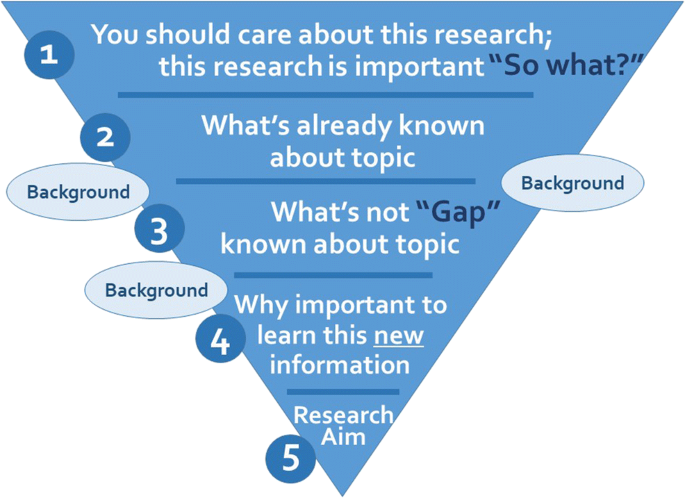

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section