How to develop a problem-solving mindset

May 14, 2023 Leaders today are confronted with more problems, of greater magnitude, than ever before. In these volatile times, it’s natural to react based on what’s worked best in the past. But when you’re solving the toughest business challenges on an ongoing basis, it’s crucial to start from a place of awareness. “If you are in an uncertain situation, the most important thing you can do is calm down,” says senior partner Aaron De Smet , who coauthored Deliberate Calm with Jacqueline Brassey and Michiel Kruyt. “Take a breath. Take stock. ‘Is the thing I’m about to do the right thing to do?’ And in many cases, the answer is no. If you were in a truly uncertain environment, if you’re in new territory, the thing you would normally do might not be the right thing.” Practicing deliberate calm not only prepares you to deal with the toughest problems, but it enhances the quality of your decisions, makes you more productive, and enables you to be a better leader. Check out these insights to learn how to develop a problem-solving mindset—and understand why the solution to any problem starts with you.

When things get rocky, practice deliberate calm

Developing dual awareness;

How to learn and lead calmly through volatile times

Future proof: Solving the ‘adaptability paradox’ for the long term

How to demonstrate calm and optimism in a crisis

How to maintain a ‘Longpath’ mindset, even amid short-term crises

Addressing employee burnout: Are you solving the right problem?

April Rinne on finding calm and meaning in a world of flux

How spiritual health fosters human resilience

6 Steps To Develop A Problem-Solving Mindset That Boosts Productivity

Problem-controlled approach vs. problem-solving approach, benefits of a problem-solving mindset, 6 steps to develop a problem-solving mindset, characteristics of a manager with a problem-solving mindset, problem-solving mindset examples for managers, frequently asked questions.

Other Related Blogs

What is a problem-solving mindset?

- Better decision-making: A problem-solving mindset helps managers analyze problems more effectively and generate various possible solutions. This leads to more informed decision-making , which is critical for effective leadership.

- Improved productivity: By addressing problems proactively, managers can prevent potential obstacles from becoming major issues that impact productivity . A problem-solving mindset can help managers to anticipate and prevent problems before they occur, leading to smoother operations and higher productivity.

- Enhanced teamwork: Encouraging a problem-solving mindset among team members fosters a culture of collaboration and encourages open communication. This can lead to stronger teamwork , as team members are more likely to work together to identify and solve problems.

- Improved morale: When managers take a proactive approach to problem-solving, they demonstrate their commitment to their team’s success. This can improve morale and build trust and respect between managers and team members.

- Better outcomes: Ultimately, a problem solving mindset leads to better outcomes. By effectively identifying and addressing problems, managers can improve processes, reduce costs, and enhance overall performance.

- Acknowledge the issue: Instead of avoiding or dismissing the problem, the first step in adopting a problem-solving mindset is to embrace it. Accept the problem and commit to trying to find a solution.

- Focus on the solutions: Shift your attention from the problem to the solution by concentrating on it. Then, work towards the result by visualizing it.

- Come up with all possible solutions: Create a list of all potential answers, even those that appear unusual or out of the ordinary. Avoid dismissing ideas prematurely and encourage creative thinking.

- Analyze the root cause: After coming up with a list of viable solutions. Finding the fundamental reason enables you to solve the problem and stop it from happening again.

- Take on a new perspective: Sometimes, a new viewpoint might result in game-breakthrough solutions. Consider looking at the problem differently, considering other people’s perspectives, or questioning your presumptions.

- Implement solutions and monitor them: Choose the best course of action, then implement it. Keep an eye on the findings and make changes as needed. Use what you learn from the process to sharpen your problem-solving skills.

- Positive attitude: A problem-solving manager approaches challenges with a positive and proactive mindset, focused on solutions rather than problems.

- Analytical thinking: A problem-solving manager breaks down complex challenges into smaller, more manageable pieces and identifies the underlying causes of difficulties because of their strong analytical skills .

- Creativity: A manager with a problem solving mindset think outside the box to solve difficulties and problems.

- Flexibility: A manager with a problem-solving mindset can change their problem-solving strategy depending on the circumstances. They are receptive to new ideas and other viewpoints.

- Collaboration: A manager who prioritizes problem-solving understands the value of collaboration and teamwork. They value team members’ feedback and are skilled at bringing diverse perspectives together to develop creative solutions.

- Strategic thinking: A problem-solving manager thinks strategically , considering the long-term consequences of their decisions and solutions. They can balance short-term fixes with long-term objectives.

- Continuous improvement: A problem-solving manager is dedicated to continuous improvement, always looking for new ways to learn and improve their problem-solving skills. They use feedback and analysis to improve their approach and achieve better results.

- 6 Principles of Adaptive Leaders that will make you a Remarkable Manager

- 9 Tips to Master the Art of Delegation for Managers

- The talent pipeline advantage: How it boosts employee retention and engagement?

- How To Prevent Workplace Bullying? 3 Perspectives

- Top 10 Team Building Activities That Smart Managers Are Using In 2023

- The Power of Focus: Achieving Success by creating One Word Goals in 5 steps

- 6 Step Process For Ethical Decision Making: A Guide with Examples

- 7 Ways to Develop Critical Thinking Skills as a Manager

- Performance Management Training: Empowering Managers To Manage Better

- Healthcare Leadership Development Plan Template: Get Started Today!

- A manager listens actively to a team member’s concerns and identifies the root cause of a problem before brainstorming potential solutions.

- A manager encourages team members to collaborate and share ideas to solve a challenging problem.

- A manager takes a proactive approach to address potential obstacles, anticipating challenges and taking steps to prevent them from becoming major issues.

- A manager analyzes data and feedback to identify patterns and insights that can inform more effective problem-solving.

- A manager uses various tools and techniques, such as brainstorming , SWOT analysis, or root cause analysis, to identify and address problems.

- To inform about problem-solving, a manager seeks input and feedback from various sources, including team members, stakeholders, and subject matter experts.

- A manager encourages experimentation and risk-taking, fostering a culture of innovation and creativity.

- A manager takes ownership of problems rather than blaming others or deflecting responsibility.

- A manager is willing to admit mistakes and learn from failures rather than become defensive or dismissive.

- A manager focuses on finding solutions rather than dwelling on problems or obstacles.

- A manager can adapt and pivot as needed, being flexible and responsive to changing circumstances or new information.

Suprabha Sharma

Suprabha, a versatile professional who blends expertise in human resources and psychology, bridges the divide between people management and personal growth with her novel perspectives at Risely. Her experience as a human resource professional has empowered her to visualize practical solutions for frequent managerial challenges that form the pivot of her writings.

Are your problem solving skills sharp enough to help you succeed?

Find out now with the help of Risely’s problem-solving assessment for managers and team leaders.

Do I have a problem-solving mindset?

What is a growth mindset for problem-solving , what is problem mindset vs. solution mindset , what is a problem-solving attitude.

Top 15 Tips for Effective Conflict Mediation at Work

Top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader, manager effectiveness: a complete guide for managers in 2024, 5 proven ways managers can build collaboration in a team.

A Positive Attitude for Problem Solving Skills

Introduction

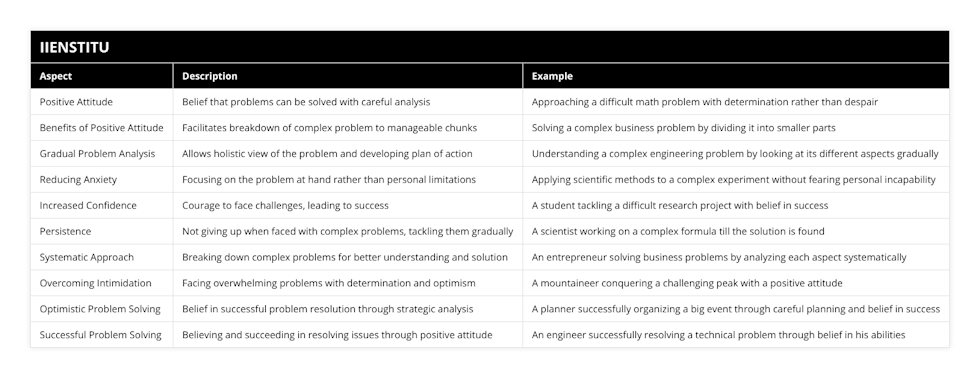

Positive Attitude

Benefits of a positive attitude.

Introduction: Problem-solving is essential for success in many areas of life, from academics to the workplace. Good problem solvers can break down a problem and gradually analyze it, while poor problem solvers often lack the confidence and experience to do this. A positive attitude towards Problem-solving is essential for success, as it allows individuals to approach problems confidently and believe they can be solved. This article will explore the benefits of a positive attitude in issue-solving, with examples of how it can help.

Optimistic problem solvers strongly believe academic reasoning problems can be solved through careful, persistent analysis. This belief is essential, as it allows individuals to approach problems with confidence and determination rather than giving up before they have even begun. A positive attitude also helps to reduce fear and anxiety when approaching complex problems, as it allows individuals to focus on the issue at hand rather than on their own perceived limitations.

The benefits of a positive attitude in problem-solving are numerous. Firstly, it allows individuals to break down a problem into smaller, more manageable chunks. This makes it easier to analyze the situation, enabling individuals to focus on one part of the problem at a time. It also helps reduce the feeling of being overwhelmed or intimidated by a problem, as it allows individuals to tackle the problem more organized and systematically.

Another benefit of a positive attitude in problem-solving is that it encourages gradual problem analysis. Poor problem solvers often give up when faced with a complex problem, believing they will never be able to solve it. However, a positive attitude allows individuals to take a step back and look at the situation holistically, considering all aspects of the problem and gradually analyzing it. This will enable individuals to understand the problem better and develop a plan of action for solving it.

To illustrate the benefits of a positive attitude in problem-solving, consider the following examples. An individual struggling to solve a mathematical problem may become overwhelmed by the complexity of the problem and give up before they have even begun. However, if they take a step back and break the problem down into smaller parts, they may be able to analyze it and come to a solution gradually. Similarly, an individual struggling to solve a complex business problem may feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the problem and give up. However, if they take a step back and break the problem down into smaller parts, they may be able to analyze it and come to a solution gradually.

TRIZ: Exploring the Revolutionary Theory of Inventive Problem Solving

7 Problem Solving Skills You Need to Succeed

Exploratory Data Analysis: Unraveling its Impact on Decision Making

Failure Tree Analysis: Effective Approach for Risk Assessment

Conclusion: In conclusion, having a positive attitude towards problem-solving is essential for success. It allows individuals to approach problems confidently and believe they can be solved. It also allows individuals to break down a problem into smaller parts and gradually analyze it, reducing feeling overwhelmed or intimidated by a crisis. Examples of how a positive attitude can help in problem-solving are provided, illustrating the importance of a positive attitude.

A positive attitude is critical to unlocking problem-solving skills. IIENSTITU

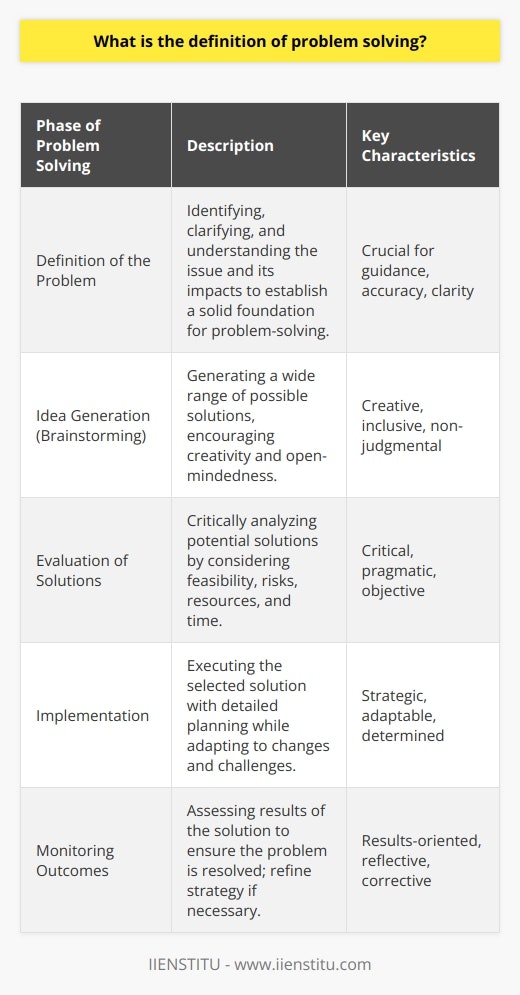

What is the definition of problem solving?

Problem-solving is a critical cognitive process involving identifying and resolving issues or obstacles. It requires the individual to analyze a problem, determine potential solutions, evaluate them, and then implement the most effective solution. Problem-solving can be defined as a cognitive process that allows individuals and groups to identify and address problems, develop potential solutions, and make decisions that lead to successful problem resolution.

The process of problem-solving is often broken down into five stages: defining the problem, generating possible solutions, evaluating the solutions, implementing the chosen solution, consists in and monitoring the outcome.

The first stage involves defining the problem by gathering information about the situation and breaking down the problem into manageable components.

The second stage involves generating possible solutions by brainstorming, researching, and consulting with experts.

The third stage consists in evaluating the answers and selecting the best one.

The fourth stage involves implementing the chosen solution.

The fifth stage involves monitoring the outcome to assess whether the solution was successful.

Problem-solving is a complex process, and the outcome's success depends on the individual's ability to analyze the problem, identify potential solutions, and evaluate the solutions before implementing the best solution. It requires individuals to think critically, use creativity and draw on their knowledge and experience. It also needs individuals to be flexible and open to different approaches and solutions.

Problem-solving is an essential skill that people use in their everyday lives. It is necessary for the successful functioning of society, as it enables individuals and groups to identify and address problems, develop potential solutions, and make decisions that lead to successful problem resolution.

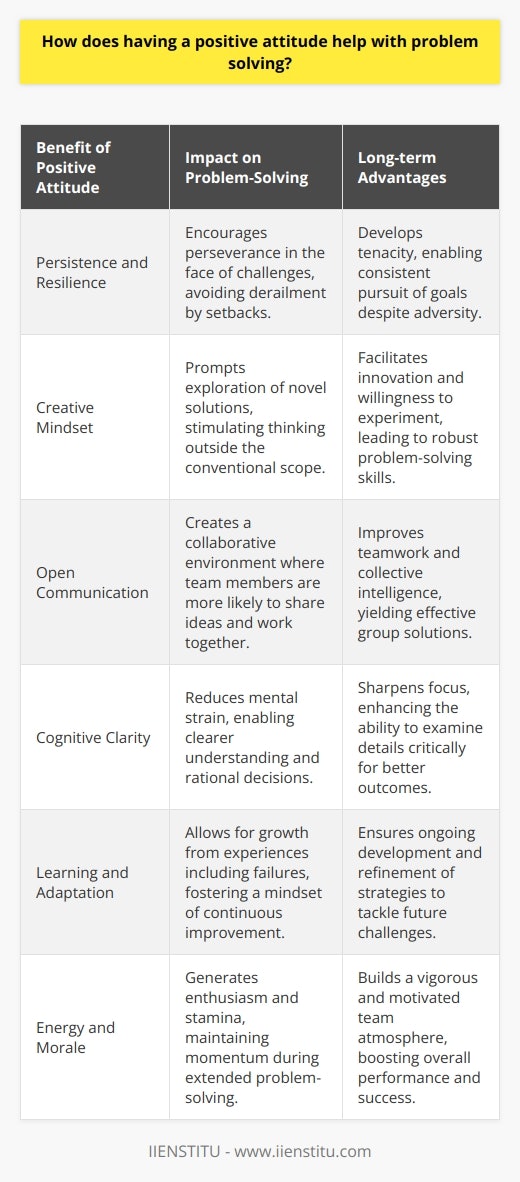

How does having a positive attitude help with problem solving?

A positive attitude when approaching a problem can be a great asset in finding a solution. It is often said that attitude is everything, and this is especially true when it comes to problem-solving. A positive attitude can lead to a more creative approach to problem-solving and increase the likelihood of finding a successful solution.

A positive attitude can help to increase motivation when approaching a problem. This can be a great asset in helping to identify the root cause of the problem and find a solution. In addition, with a positive attitude, an individual is more likely to take on the challenge of solving the problem rather than avoiding it or simply giving up.

Having a positive attitude can also help to promote constructive thinking. That is, thinking that focuses on solutions rather than playing the blame game or worrying about the consequences of failure. A positive attitude can help to keep the focus on finding solutions and staying motivated to work through the problem until a successful outcome is achieved.

In addition, having a positive attitude can help to reduce stress when tackling a problem. This can be invaluable in helping to maintain a clear mind and allow for the type of creative thinking that is often necessary when finding solutions. A positive attitude can help to keep the individual focused on the task at hand and help to prevent a feeling of being overwhelmed by the problem.

Finally, having a positive attitude can help to create a positive environment when approaching a problem. That environment encourages collaboration and brainstorming and promotes the exchange of ideas. This can be key to finding a successful solution.

In conclusion, having a positive attitude when approaching a problem can be a great asset in finding a successful solution. A positive attitude can help to increase motivation, promote constructive thinking, reduce stress, and create a positive environment when approaching a problem.

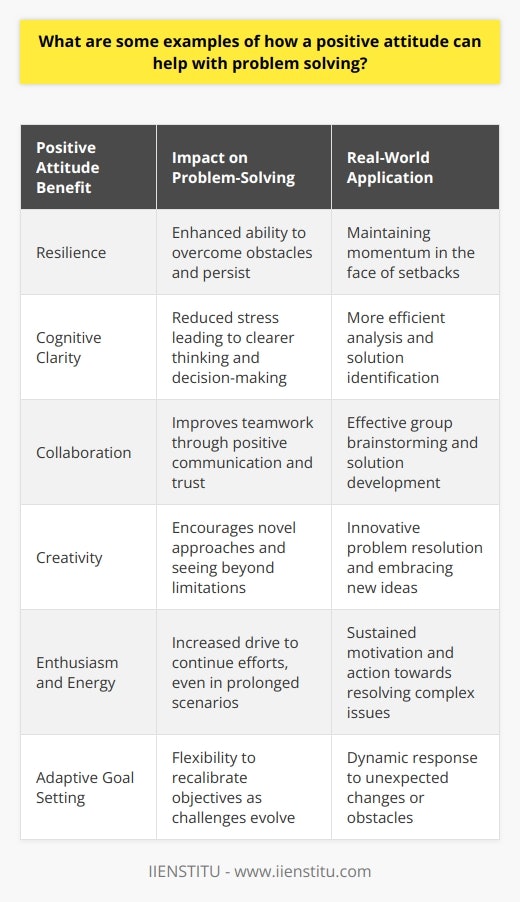

What are some examples of how a positive attitude can help with problem solving?

A positive attitude when facing a problem can be incredibly beneficial in solving it. Viewing the problem as an opportunity to learn and grow rather than a hurdle that cannot be overcome is essential. With the right attitude, problems can be solved more effectively and quickly.

One way that a positive attitude can help with problem-solving is by increasing motivation and perseverance. People with a positive attitude are likelier to persist in issue-solving and not give up when the going gets tough. With this attitude, it is more likely that a solution will be found.

Another way that a positive attitude can help with problem-solving is by providing greater clarity and focus. People with a positive attitude are more likely to take a step back and look at a situation objectively, allowing them to understand the problem better and develop a plan for solving it. This clarity and focus can also help to prevent distractions from derailing the problem-solving process.

Finally, a positive attitude can help to foster creativity and innovation. People with a positive attitude are more likely to look at a problem from a different perspective, allowing them to come up with creative solutions that would not have been considered otherwise. This creativity can be incredibly beneficial in finding a solution to a tricky problem.

In conclusion, I have a positive attitude when problem-solving can be immensely beneficial. It can increase motivation, provide clarity and focus, and foster creativity and innovation, all of which are important in finding a solution to a problem. Therefore, it is essential to maintain a positive attitude when facing a problem to maximize the chances of finding a solution.

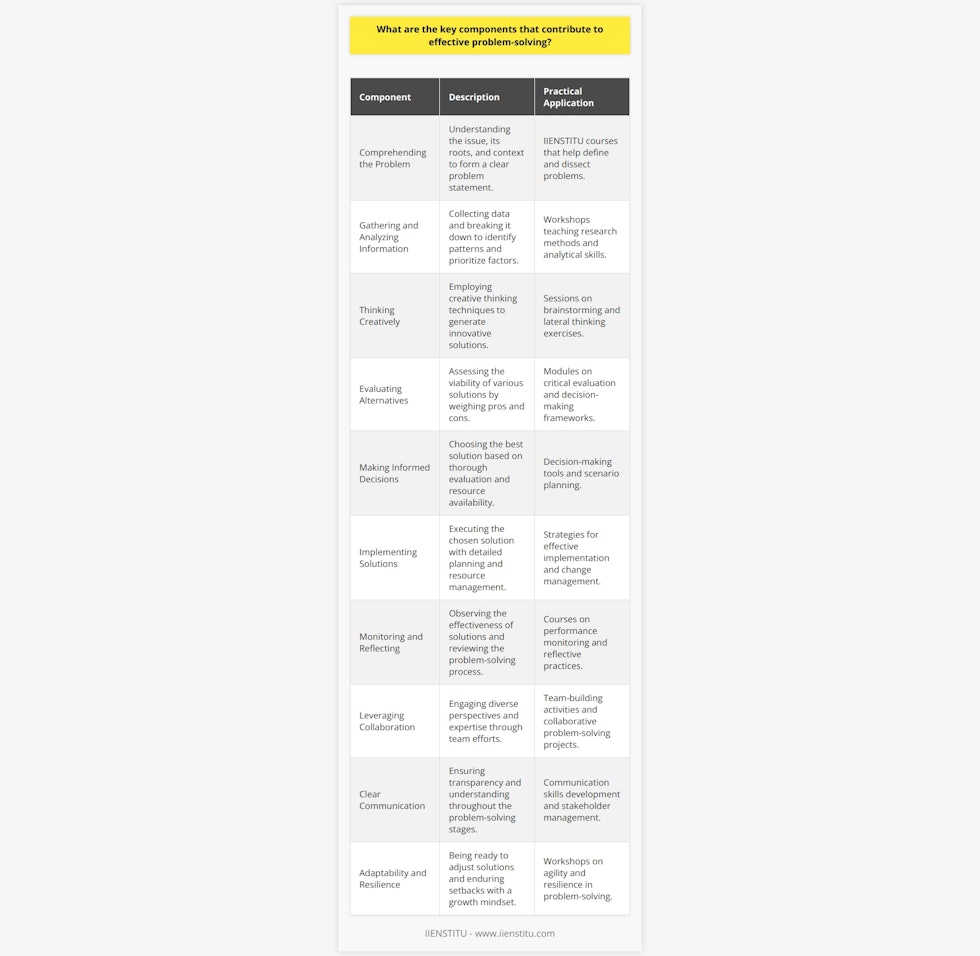

What are the key components that contribute to effective problem-solving?

Key Components of Effective Problem-Solving Understanding the Situation The first component of effective problem-solving is understanding the situation properly. This entails gathering comprehensive information about the problem and defining it explicitly. Accurate problem identification enables the problem-solver to establish relevant goals and objectives that are critical in devising feasible solutions. Exploring Multiple Perspectives Divergent thinking, or exploring multiple perspectives, is the second key component. It involves considering different viewpoints, opinions, and beliefs in order to identify various aspects of the problem. By being open-minded and considering different alternatives, a problem solver can generate multiple potential solutions, increasing the likelihood of developing an effective and creative resolution. Critical Thinking and Analysis The third key component is critical thinking and analysis, involving the evaluation of the problem and potential solutions. By analyzing each solution's pros and cons, the problem solver can determine the most appropriate course of action. Factoring in the feasibility, practicality, and effectiveness of each solution allows for selecting the most viable option that adheres to predetermined goals and objectives. Decision Making and Implementation The fourth component is decision making and implementation, which requires selecting the best solution and putting it into practice. It is crucial to consider the potential consequences and necessary resources while taking decisive action. Effective problem-solving involves continual assessment and adjustments to improve and refine the chosen solution. Collaboration and Communication Lastly, collaboration and communication play a significant role in problem-solving. Consulting with other individuals can offer fresh insights, ideas, and expertise, which can greatly enhance the problem-solving process. Furthermore, clear and concise communication is essential in conveying the problem, proposed solutions, and implementation strategies to all relevant stakeholders. In conclusion, effective problem-solving is a multifaceted process that involves understanding the situation, exploring multiple perspectives, employing critical thinking and analysis, making decisions and implementing solutions, and cultivating collaboration and communication. By mastering these components, individuals and teams can successfully address various challenges and achieve their goals.

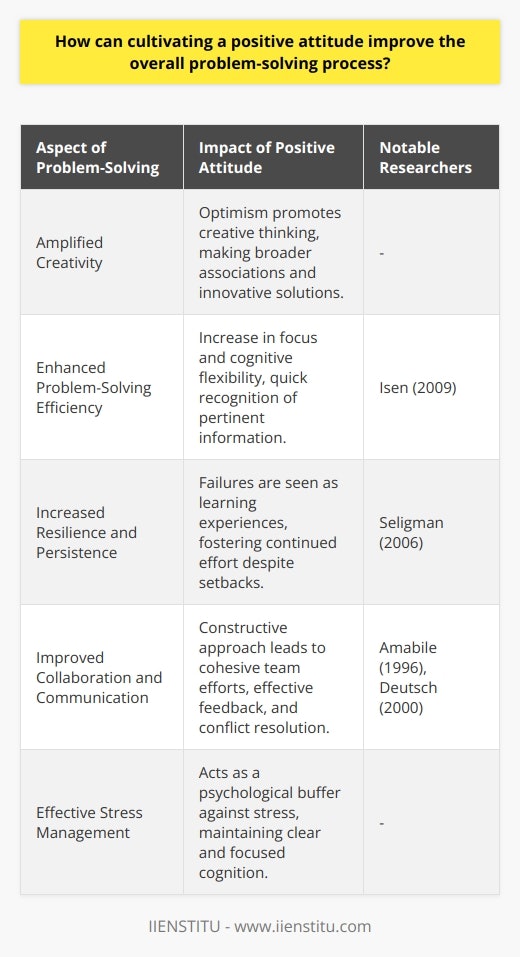

How can cultivating a positive attitude improve the overall problem-solving process?

Significance of a Positive Attitude Cultivating a positive attitude plays a vital role in enhancing the problem-solving process by fostering creativity and increasing motivation to succeed. When an individual approaches a problem with a positive mindset, they are more likely to engage in divergent thinking, where multiple solutions are explored to reach an optimal outcome (Isen, 2009). This perspective enables them to consider various alternative paths, leading to increased adaptability and a more manageable pathway towards resolution. Impact on Cognitive Abilities A positive attitude also enhances cognitive abilities, allowing individuals to effectively process information, identify patterns, and make logical connections (Fredrickson, 2004). By focusing on the potential for success, the brain can more efficiently organize and analyze relevant data, improving the quality of the decision-making process. Furthermore, optimism bolsters resilience and persistence, as individuals are more likely to view setbacks as temporary obstacles rather than insurmountable barriers (Seligman, 2006). Collaboration and Conflict Resolution Positive attitude extends beyond personal cognitive benefits and has the potential to improve group dynamics when solving complex problems collectively. By promoting a constructive environment, individuals are encouraged to share ideas, learn from others, and support their peers in formulating creative solutions (Amabile, 1996). Moreover, a positive attitude facilitates effective conflict resolution, as individuals are more predisposed to understand alternative viewpoints and collaborate to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes (Deutsch, 2000). Conclusion In conclusion, cultivating a positive attitude yields numerous benefits for the overall problem-solving process. By stimulating divergent thinking, enhancing cognitive abilities, and fostering effective collaboration among team members, individuals with a positive mindset can overcome challenges and develop innovative solutions. Therefore, embracing optimism and resilience significantly improves not only one’s personal problem-solving skills but also fosters a supportive environment where the collective intelligence thrives.

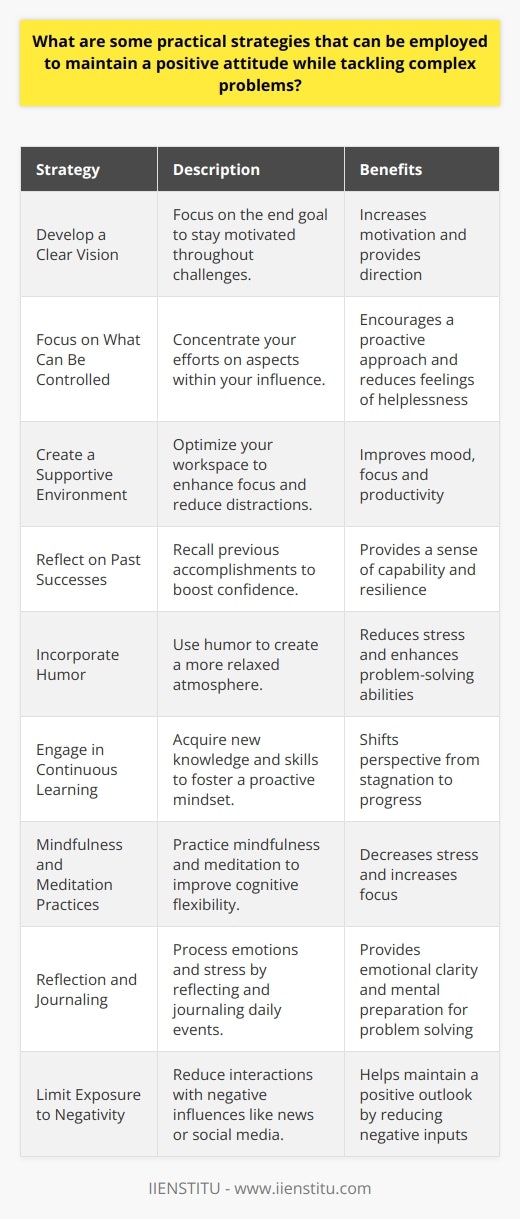

What are some practical strategies that can be employed to maintain a positive attitude while tackling complex problems?

Practical strategies for maintaining a positive attitude Cultivating a growth mindset One practical strategy for maintaining a positive attitude while tackling complex problems is cultivating a growth mindset. This involves embracing challenges, viewing failures as opportunities to learn and persisting in the face of obstacles. Setting smaller, achievable goals Another strategy is setting smaller, achievable goals. Breaking the complex problem down into manageable tasks helps make it less daunting and encourages progress. Completion of each smaller task provides a sense of accomplishment, motivating continued efforts. Adopting effective time management Implementing effective time management not only improves efficiency but also reduces stress. Prioritising tasks, setting realistic deadlines and incorporating breaks into the schedule ensures steady progress and protects against burnout. Emphasising mental and physical well-being Maintaining mental and physical well-being is crucial for sustaining a positive attitude. Prioritising sleep, nutrition, exercise and relaxation promotes a healthy mindset, better focus and increased resilience when faced with difficult problems. Surrounding oneself with positivity Our social environment can significantly impact our attitude. Surrounding oneself with positive, supportive and like-minded individuals helps create an uplifting environment conducive to problem-solving. Practicing self-compassion Recognising that everyone experiences occasional setbacks is essential for maintaining a positive attitude. Instead of being self-critical, practice self-compassion, accepting the present circumstances and focusing on what can be controlled and improved. Using positive affirmations Positive affirmations are statements that promote a positive mindset and stress resilience. Repeating these affirmations throughout the day can help boost self-esteem, motivation and overall attitude. Seeking external resources Lastly, seeking external resources like books, articles, online courses or even consulting with experts can provide valuable insights and tools for solving complex problems. These resources augment understanding and foster a sense of empowerment. In conclusion, incorporating various practical strategies such as cultivating a growth mindset, setting smaller goals, managing time effectively, prioritising well-being, surrounding oneself with positivity, practicing self-compassion, using positive affirmations and seeking external resources can help maintain a positive attitude while tackling complex problems. These approaches not only facilitate problem-solving but also improve overall resilience and well-being.

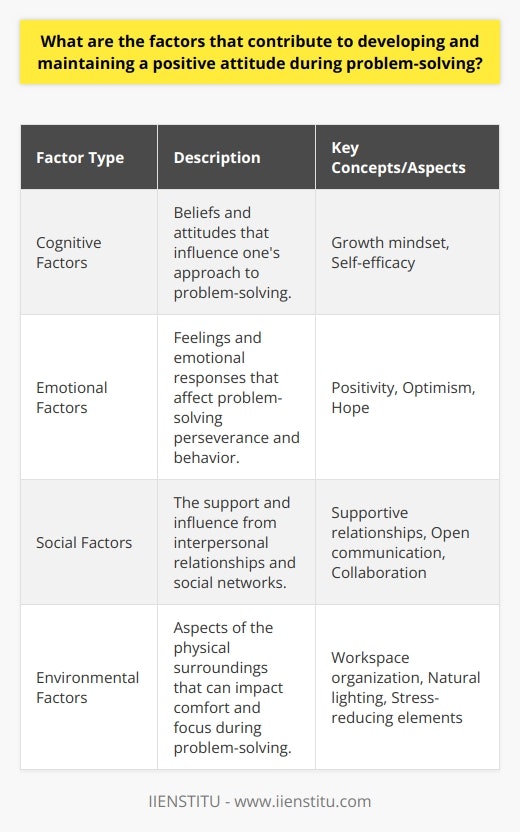

What are the factors that contribute to developing and maintaining a positive attitude during problem-solving?

Factors Influencing Positive Attitude Development Various factors contribute to developing and maintaining a positive attitude during problem-solving, which can enhance an individual's overall performance and success in finding effective solutions. These factors include cognitive, emotional, social, and environmental aspects. Cognitive Factors The cognitive factors involve an individual's inherent beliefs, perceptions, and thought patterns. A growth mindset, which embraces challenges and views effort as a pathway to improvement, is critical for fostering a positive attitude during problem-solving. Additionally, self-efficacy, or the belief in one's ability to achieve a desired outcome, can boost problem-solving efficiency and facilitate a positive attitude. Emotional Factors Positive emotions, like optimism and hope, play a vital role in maintaining a positive attitude during problem-solving. Optimism fosters resilience and encourages an individual to face challenges with a constructive approach. Further, hope promotes goal-directed thinking, adaptive coping strategies, and heightened motivation, which influence one's problem-solving attitude positively. Social Factors The social environment, including the presence of supportive peers, mentors, or supervisors, can contribute to a positive attitude development during problem-solving. Individuals in encouraging social contexts are more likely to feel confident and motivated to tackle challenges. Collaboration and teamwork can also facilitate diverse perspectives and creative solutions, promoting a constructive problem-solving attitude. Environmental Factors Lastly, the physical environment can impact an individual's attitude while addressing problems. A comfortable, organized, and functional workspace can foster focus, productivity, and a positive attitude. Additionally, implementing stress-relief techniques, such as regular breaks and stress-relieving activities, can foster a relaxed state of mind, essential for problem-solving. In conclusion, developing and maintaining a positive attitude during problem-solving involves a holistic approach that takes into account cognitive, emotional, social, and environmental factors. Cultivating a growth mindset, nurturing positive emotions, fostering supportive social connections, and optimizing the physical environment can significantly enhance an individual's problem-solving attitude and performance.

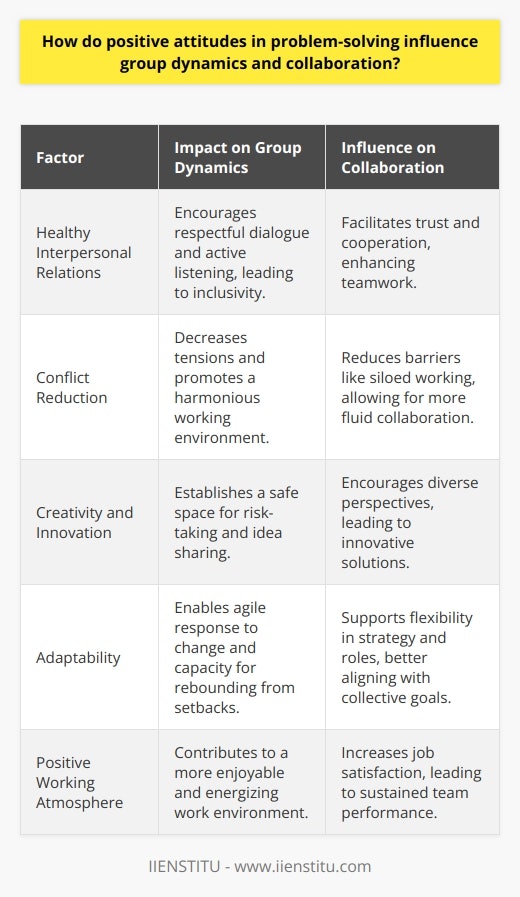

How do positive attitudes in problem-solving influence group dynamics and collaboration?

Impact on Group Dynamics Positive attitudes in problem-solving significantly affect group dynamics by fostering healthy communication channels, active participation, and commitment. With a solution-oriented mindset, group members tend to focus more on finding common ground, thereby minimizing conflicts and misunderstandings. As individuals distinctly acknowledge the potential of diverse perspectives in the resolution of complex tasks, they adopt a proactive approach to engaging with others. Enhancing Collaboration In addition, a positive problem-solving atmosphere promotes a sense of shared responsibility among group members. This feeling of connectedness paves the way for smooth collaboration, allowing individuals to leverage their strengths in achieving a shared objective. When group members support one another in overcoming challenges, they build trust and strengthen their interdependence, which is crucial for promoting a cohesive team culture. Promoting Creativity and Innovation Moreover, positive attitudes in problem-solving stimulate creativity and innovation within groups, as participants feel more comfortable sharing their ideas and thinking outside the box. By fostering an environment that celebrates diverse thinking and encourages open discussions, groups harness a wealth of knowledge that ultimately leads to the generation of novel solutions to complex issues. Encouraging Adaptability Furthermore, groups with a positive problem-solving outlook demonstrate high adaptability and resilience when encountering unexpected obstacles or setbacks. By focusing on solutions rather than dwelling on failure, members develop a sense of empowerment and determination. This, in turn, increases the group's overall capacity to develop and implement effective strategies that address the task at hand. Conclusion In summary, positive attitudes in problem-solving significantly influence group dynamics and collaboration by facilitating effective communication, fostering collective responsibility, stimulating creativity, and promoting adaptability. By cultivating a constructive and solution-oriented environment, groups can enhance their overall effectiveness and maximize their potential in achieving desired outcomes.

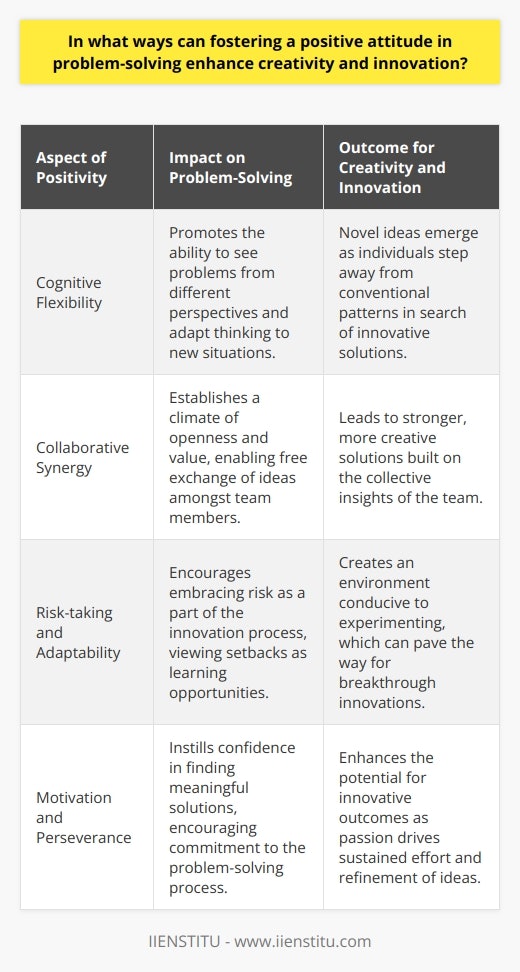

In what ways can fostering a positive attitude in problem-solving enhance creativity and innovation?

The Impact of a Positive Attitude Fostering a positive attitude in problem-solving significantly influences creativity and innovation within individuals and organizations. A positive mindset toward problem-solving allows the individual to explore more possibilities, yielding dynamic approaches for resolving issues. The Role of Cognitive Flexibility One crucial aspect of this influence is cognitive flexibility, which is the ability to think about a problem from multiple perspectives and generate diverse ideas. A positive attitude improves cognitive flexibility by encouraging individuals to focus on the potential benefits of generating innovative solutions, rather than dwelling on the difficulties faced in arriving at those solutions. This shift in focus enhances creative thinking by expanding the range of ideas and perspectives explored. Encouragement of Collaboration Additionally, a positive attitude promotes collaboration and knowledge sharing among team members, fostering a synergistic environment that supports idea generation and innovation. When individuals approach problem-solving with optimism, they are more open to hearing and learning from others' perspectives, facilitating the exchange of valuable insights and ideas. Embracing Risk-taking and Uncertainty Furthermore, a positive mindset empowers individuals to embrace risks and uncertainties associated with innovative problem-solving. By considering setbacks and failures as opportunities for learning and improvement, individuals can develop resilience and adaptability, vital traits for creativity and innovation. A positive attitude toward problem-solving encourages experimentation and learning, cultivating a growth mindset that fuels innovation. Enhanced Motivation and Persistence Finally, a positive attitude bolsters motivation and persistence in the face of challenging problems. When individuals believe in their ability to find solutions and the potential value of their ideas, they become more passionate about the problem-solving process. They are more likely to continue exploring and refining ideas, resulting in an increase in creative output and the development of innovative solutions. In conclusion, fostering a positive attitude in problem-solving can greatly enhance creativity and innovation by supporting cognitive flexibility, encouraging collaboration, embracing risk-taking and uncertainty, and bolstering motivation and persistence. Therefore, individuals and organizations should invest in cultivating a positive outlook for improved problem-solving outcomes, driving overall success.

Yu Payne is an American professional who believes in personal growth. After studying The Art & Science of Transformational from Erickson College, she continuously seeks out new trainings to improve herself. She has been producing content for the IIENSTITU Blog since 2021. Her work has been featured on various platforms, including but not limited to: ThriveGlobal, TinyBuddha, and Addicted2Success. Yu aspires to help others reach their full potential and live their best lives.

What are Problem Solving Skills?

3 Apps To Help Improve Problem Solving Skills

How To Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

Improve Your Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills

Edison's 99%: Problem Solving Skills

How To Become a Great Problem Solver?

Definition of Problem-Solving With Examples

A Problem Solving Method: Brainstorming

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Brief research report article, the influence of attitudes and beliefs on the problem-solving performance.

- 1 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Education of Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Germany

- 2 Hamburg Center for University Teaching and Learning, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

The problem-solving performance of primary school students depend on their attitudes and beliefs. As it is not easy to change attitudes, we aimed to change the relationship between problem-solving performance and attitudes with a training program. The training was based on the assumption that self-generated external representations support the problem-solving process. Furthermore, we assumed that students who are encouraged to generate representations will be successful, especially when they analyze and reflect on their products. A paper-pencil test of attitudes and beliefs was used to measure the constructs of willingness, perseverance, and self-confidence. We predicted that participation in the training program would attenuate the relationship between attitudes and problem-solving performance and that non-participation would not affect the relationship. The results indicate that students’ attitudes had a positive effect on their problem-solving performance only for students who did not participate in the training.

Introduction

Mathematical problem solving is considered to be one of the most difficult tasks primary students have to deal with ( Verschaffel et al., 1999 ) since it requires them to apply multiple skills ( De Corte et al., 2000 ). It is decisive in this respect that “difficulty should be an intellectual impasse rather than a computational one” ( Schoenfeld, 1985 , p. 74). When solving problems, it is not enough to retrieve procedural knowledge and reproduce a known solution approach. Rather, problem-solving tasks require students to come up with new ways of thinking ( Bransford and Stein, 1993 ). Problem-solvers must activate their existing knowledge network and adapt it to the respective problem situation ( van Dijk and Kintsch, 1983 ). They have to succeed in generating an adequate representation of the problem situation (e.g., Mayer and Hegarty, 1996 ). This requires conceptual knowledge, which novice problem-solvers have to acquire ( Bransford et al., 2000 ). As problem solving is the foundation for learning mathematics, an important goal of primary school mathematics teaching is to strengthen students’ problem-solving performance. One central problem is that problem-solving performance is highly influenced by students’ attitudes towards problem solving ( Reiss et al., 2002 ; Schoenfeld, 1985 ; Verschaffel et al., 2000 ).

Attitudes and beliefs are considered quite stable once they are developed ( Hannula, 2002 ; Goldin, 2003 ). However, students who are novices in a particular content area are still in the process of development, as are their attitudes and beliefs. It can therefore be assumed that their attitudes change over time ( Hannula, 2002 ). However, such a change does not take place quickly ( Higgins, 1997 ; Mason and Scrivani, 2004 ). Nevertheless, in a shorter period of time, it might be possible to reduce the influence of attitudes on problem-solving performance ( Hannula et al., 2019 ). In this paper, we present a training program for primary school students, which aims to do exactly that.

Problem-Solving Performance

Successful problem solving can be observed on two levels: problem-solving success and problem-solving skills. Many studies measure the problem-solving performance of students on the basis of correctly or incorrectly solved problem-solving tasks, that is, the product (e.g., Boonen et al., 2013 ; de Corte et al., 1992 ; Hegarty et al., 1992 ; Verschaffel et al., 1999 ). In this case, only problem-solving success, that is, specifically whether the numerically obtained result is correct or incorrect, is evaluated. This is a strict assessment measure, since the problem-solving process is not taken into account. As a result, the problem-solving performance is only considered from a single, product-oriented perspective. For instance students’ performance is assessed as unsuccessful when they apply an essentially correct procedure or strategy but achieve the wrong result, or it is considered successful when students achieve the right result even though they have misunderstood the problem ( Lester and Kroll, 1990 ). An advantage of this operationalization, however, is that student performance tends to be underestimated rather than overestimated.

A more differentiated view of successful problem solving includes the solver’s problem-solving process ( Lester and Kroll, 1990 ; cf. Adibnia and Putt, 1998 ). In this way, sub-skills such as understanding the problem, adequately representing the situation, applying strategies, or achieving partial solutions are taken into account. These are then incorporated into the evaluation of performance and, thus, of problem-solving skills ( Charles et al., 1987 ; cf. Sturm, 2019 ). The advantage of this operationalization option is that it also takes into account smaller advances by the solver, although they may not yet lead to the correct result. It is therefore less likely to underestimate students’ performance. In order to assess and evaluate the problem-solving skills of students in the best way and, thus, avoid over- and under-estimating their skills, direct observation and questioning should be implemented (e.g., Lester and Kroll, 1990 ). An analysis of written work should not be the only means of assessment ( Lester and Kroll, 1990 ).

Attitudes and Beliefs

Attitudes are dispositions to like or dislike objects, persons, institutions, or events ( Ajzen, 2005 ). They influence behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Therefore, it is not surprising that attitudes–which are sometimes also synonymously referred to as beliefs–are a central construct in psychology ( Ajzen, 2005 ).

Individual attitudes to word problems influence, albeit rather unconsciously, approaches to such problems and willingness to learn mathematics and solve problems ( Grigutsch et al., 1998 ; Awofala, 2014 ). Research on attitudes of primary students to word problems is scarce. Most research focuses on students with well-established attitudes. However, the importance of the attitudes of younger children is undisputed ( Di Martino, 2019 ). Di Martino (2019) conducted a study on kindergarten children as well as on first-, third-, and fifth-graders and found that, with increasing age, students’ perceived competence in problem solving decreases, and negative emotions towards mathematical problems increase. Whether a solver can overcome problem barriers when dealing with word problems depends not only on his or her previous knowledge, abilities, and skills, but also on his or her attitudes and beliefs ( Schoenfeld, 1985 ; Verschaffel et al., 2000 ; Reiss et al., 2002 ). It has been shown many times that attitudes towards problem solving are influencing factors on performance and learning success which should not be underestimated ( Charles et al., 1987 ; Lester et al., 1989 ; Lester & Kroll, 1990 ; De Corte et al., 2002 ; Goldin et al., 2009 ; Awofala, 2014 ). Learners associate a specific feeling with an object, in this case with a word problem, triggering a specific emotional state ( Grigutsch et al., 1998 ). The feelings and states generated are subjective and can therefore vary between individuals ( Goldin et al., 2009 ).

Attitudes towards problem solving can be divided into willingness, perseverance, and self-confidence ( Charles et al., 1987 ; Lester et al., 1989 ). This distinction comes from the Mathematical Problem-Solving Project, in which Webb, Moses, and Kerr (1977) found that willingness to solve problems, perseverance in attempting to find a solution, and self-confidence in the ability to solve problems are the most important influences on problem-solving performance. When students are willing to work on a variety of mathematics tasks and persevere with tasks until they find a solution, they are more task oriented and easier to motivate ( Reyes, 1984 ). Perseverance is defined as the willing pursuit of a goal-oriented behavior even if this involves overcoming obstacles, difficulties, and disappointments ( Peterson and Seligman, 2004 ). Confidence is an individual’s belief in his or her ability to succeed in solving even challenging problems as well as an individual’s belief in his or her own competence with respect to his or her peers ( Lester et al., 1989 ). Students’ lack of confidence in themselves as problem-solvers or their beliefs about mathematics can considerably undermine their ability to solve or even approach problems in a productive way ( Shaughnessy, 1985 ). The division of attitudes into these three sub-categories can also be found in current studies ( Zakaria and Yusoff, 2009 ; Zakaria and Ngah, 2011 ).

Reducing the Influence of Attitudes and Beliefs

As it seems impossible to change attitudes within a short time frame, we developed a training program to reduce the influence of attitudes on problem solving, on the one hand, and to foster the problem-solving performance of primary-school students, on the other hand.

The training program was an integral part of regular math classes and focused on teaching students to generate and use external representations ( Sturm, 2019 ; Sturm et al., 2016 ; Sturm and Rasch, 2015 ; see also Supplementary Appendix A ). Such a program that concentrates on the strengths and weaknesses of novices and on their individually generated external representations can be a benefit for primary-school students in two ways. The class discusses how the structure described in the problem can be adequately represented so that the solution can be found, working out multiple approaches based on different student representations. The students are thus exposed to ideas about how a problem can be solved in different ways. Such a training program fulfils, albeit rather implicitly, another essential component. By respectfully considering their individual thoughts and difficulties, the students are made aware of their strengths and their creativity and of the fact that there is not a single correct approach or solution that everyone has to find ( Lester and Cai, 2016 ; Di Martino, 2019 ). This can counteract fears of failure and lack of self-confidence, and generate positive attitudes ( Lester and Cai, 2016 ; Di Martino, 2019 ). The teacher pays attention to the solution process rather than to the numerical result in order to reduce the influence of attitudes on performance ( Di Martino, 2019 ). In the same way, experiencing success and perceiving increasing flexibility and agility can reduce the influence of attitudes. As a result, we expected attitudes and beliefs to have a smaller effect on problem-solving performance.

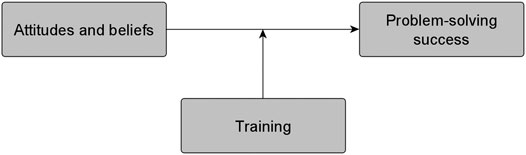

Based on previous research, our goal was to reduce the influence of attitudes on the problem-solving performance of students (see Figure 1 ). To this end, the hypothesis was derived that participation in the training program would minimize the effect of attitudes and beliefs on problem-solving success, so that students would succeed at the end of the training despite initial negative attitudes and beliefs.

FIGURE 1 . The moderation model with the single moderator variable training influencing the effect of attitudes and beliefs on problem-solving success.

Participants

In total 335 students from 20 Grade 3 classes from eight different primary schools in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate took part in the intervention study (172 boys and 163 girls). Nineteen students dropped out because of illness during the intervention. The age of the participants ranged between seven and ten years ( M = 8.10, SD = 0.47).

This investigation was part of a large interdisciplinary project 1 . A central focus of the project was to investigate whether representation training has a demonstrable effect on the performance of third-graders (cf. Sturm, 2019 ). For this reason, we implemented a pretest-posttest control group design. The intervention took place between Measurement Points 1 and 2. We measured the problem-solving performance of the students with a word-problem-solving test (WPST) at Measurement Points 1 and 2. All other variables were measured at Measurement Point 1 only (factors to establish comparable experimental conditions: intelligence, text comprehension, and mathematical abilities; co-variates for the mediation model: metacognitive skills, mathematical abilities).

In the intervention, third-grade students worked on challenging word problems for one regular mathematics lesson a week. The intervention was based on six task types with different structures ( Sturm and Rasch, 2015 ): 1) comparison tasks, 2) motion tasks, 3) tasks involving comparisons and balancing items or money, 4) tasks involving combinatorics, 5) tasks in which structure reflects the proportion of spaces and limitations, and 6) tasks with complex information. Two word problems were included for each task type and were presented to all classes in the same random sequence. Each task had to be completed in a maximum of one lesson.

The training was implemented for half of the classes and was conducted by the first author; the other half worked on the tasks with their regular mathematics teacher. They were not informed on the purpose of the intervention and not given any instructions on how to process the tasks. In the lessons for students doing the training, the students were explicitly cognitively stimulated to generate external representations and to use them to develop solutions. They were repeatedly encouraged to persevere and not to give up. The diverse external representations generated by the students were analyzed, discussed, and compared by the class during the training. They jointly identified the characteristics of representations that enabled them to specifically solve the tasks and identified different approaches (for more details about the study, see Sturm and Rasch, 2015 ). With the goal of reducing the influence of attitudes on performance, the class worked directly on the students’ own representations instead of on prefabricated representations. The aim was that students realized that it was worthwhile investing effort into creating representations and that they were able to solve problem tasks independently.

Thus, the study was composed of two experimental conditions: training program ( n = 176; 47% boys) (hereinafter abbreviated to T+) and no training program ( n = 159; 58% boys) (hereinafter abbreviated to T-). In order to control potential interindividual differences, the 20 classes were assigned to the experimental conditions by applying parallelization at class level ( Breaugh and Arnold, 2007 ; Myers and Hansen, 2012 ). The classes were grouped into homogeneous blocks using the R package blockTools Version 0.6-3 and then randomly assigned to the experimental conditions ( Greevy et al., 2004 ; Moore, 2012 ; see also Supplementary Appendix B for more information).

Word-Problem-Solving Test

Before the intervention and immediately after it, the students worked on a WPST, which we created. It consisted in each case of three challenging word problems with an open answer format. Each of the three tasks represented a different type of problem. The word problems from the WPST at Measurement Point 1 and the word problems from the WPST at Measurement Point 2 had the same structure. We implemented two parallel versions; only the context was changed by exchanging single words (see Supplementary Appendix C ). An example of an item from the test is a task with complex information ( Sturm, 2018 ): Classes 3a and 3b go to the computer room. Some students have to work at a computer in pairs. In total there are 25 computers, but 40 students. How many students work alone at a computer? How many students work at a computer in pairs? Direct observation and questioning could not be conducted due to the large number of participants in the project; only the students’ written work was available for analysis. The problem-solving process of the students could therefore only be assessed indirectly. For this reason, the performance of students in the two tests was evaluated based on problem-solving success, ruling out overestimation of performance.

Problem-Solving Success

The success of the solution was measured dichotomously in two forms: 1) correct solution and (0) incorrect solution. Only the correctness of the result achieved was evaluated. This dependent variable acted as a strict criterion that could be quantified with high observer agreement (κ = 0.97; κ min = 0.93, κ max = 1.00). A confirmatory factor analysis using the R package lavaan version 0.6-7 confirmed that the WPST measured the one-dimensional construct problem-solving success. The one-dimensional model exhibited a good model fit ( Nussbeck et al., 2006 ; Hair et al., 2009 ): χ 2 (27) = 36.613, p = 0.103; χ 2 /df = 1.356, CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.981, SRMR = 0.032, RMSEA = 0.033 ( p = 0.854). The reliability coefficients at Measurement Point 1 were classified as low (Cronbach’s α = 0.39) because the test consisted of only three items ( Eid et al., 2011 ) and a homogeneous sample was required at this measurement point ( Lienert and Raatz, 1998 ). The Cronbach’s alpha for the second measurement point (α = 0.60) was considered to be sufficient ( Hair et al., 2009 ). The test score represented the mean value of all three task scores.

Attitudes and Beliefs About Problem Solving

The attitudes and beliefs of the learners were recorded with the Attitudes Inventory Items ( Webb et al., 1977 ; Charles et al., 1987 ). The original questionnaire comprises 20 items, which are measured dichotomously (“I agree” and “I disagree”). The Attitudes Inventory measures the three categories of attitudes and beliefs related to problem solving: a) willingness (six items), b) perseverance (six items), and c) self-confidence (eight items). An example of an item for willingness is: “I will try to solve almost any problem.” An example of an item for perseverance is: “When I do not get the right answer right away, I give up.” An example of an item for self-confidence is: “I am sure I can solve most problems.”

Because the reported reliabilities were only satisfactory to some extent (α = 0.79, mean = 0.64) ( Webb et al., 1977 ), the Attitudes Inventory was initially tested on a smaller sample ( n = 74; M = 8.6 years old; 59% girls). A satisfactory Cronbach’s α = 0.86 was achieved (mean α = 0.73). The number of items was reduced to 13 (four items for willingness, four items for perseverance, five items for self-confidence), which had only a minor influence on reliability (α = 0.83). For economic reasons, the shortened questionnaire was used in the study. The three-factor structure of the questionnaire was confirmed with a confirmatory factor analysis using the R package lavaan version 0.6–7. As the fit indices show, the three-factor model had a good model fit: χ 2 (62) = 134.856, p < 0.001; χ 2 / df = 2.175, CFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.935, RMSEA = 0.062 ( p = 0.086) ( Hair et al., 2009 ; Brown, 2015 ). The three-factor model had a better fit than the single-factor model ( p = 0.0014): χ 2 (65) = 152.121, p < 0.001; χ 2 / df = 2.340, CFI = 0.938, TLI = 0.926, SRMR = 0.061, RMSEA = 0.066 ( p = 0.028). The students were grouped into three groups ( M –1 SD ; M ; M +1 SD ). The responses were coded in such a way that high scores ( M +1 SD ) indicated positive attitudes and beliefs, and low scores ( M –1 SD ) indicated negative attitudes and beliefs.

Additional Influencing Factors

In order to ensure the internal validity of the investigation, we collected student-related factors that influence the solution of word problems from a theoretical and empirical point of view. It has been shown that the mathematical abilities and metacognitive skills of students significantly influence their performance ( Sturm et al., 2015 ).

Mathematical Abilities

The basic mathematical abilities were determined using a standardized German-language test as a group test (Heidelberger Rechentest HRT 1–4, Haffner et al., 2005 ). The test consists of eleven subtests, from which three scale values were determined: calculation operations, numerical-logical and spatial-visual skills as well as the overall performance for all eleven subtests. The reliability was only satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.74). Total performance was included in the study.

Metacognitive Skills

The metacognitive skills of the students were measured using a paper-pencil version of EPA2000, a test to measure metacognitive skills before and/or after the solving of tasks ( Clercq et al., 2000 ). The prediction skills and evaluation skills of the students were collected for all three word problems of the WPST using a 4-point rating scale: 1) “absolutely sure, it’s wrong,” 2) “sure, it’s wrong,” 3) “sure, it’s right,” and 4) “absolutely sure, it’s right” ( Clercq et al., 2000 ). If the students’ assessments of “absolutely sure” matched their solution, they were awarded 2 points. If they agreed with “sure,” they received 1 point. No match was scored with 0 points ( Desoete et al., 2003 ). The reliabilities were only satisfactory (Cronbach’s α total =0.74, α prediction =0.56, α evaluation = 0.73). A confirmatory factor analysis revealed that prediction skills and evaluation skills represent a single factor (χ 2 (9) = 16.652, p < 0.001; χ 2 / df = 1.850, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.919, RMSEA = 0.053 ( p = 0.396)). The aggregated factor was used as a control variable in the moderator analysis.

In addition to the variables considered in this paper, text comprehension and intelligence were also surveyed in the project. However, they are not the focus of this paper; additional information can be found in Sturm et al. (2015) .

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between the Measures

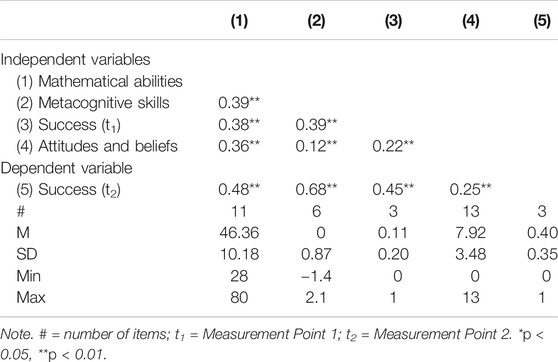

The descriptive statistics and correlations of all scales are presented in Table 1 (see Supplementary Appendix D for a separate overview for each of the experimental conditions). The signs for all correlations were as expected. The variable training program is not listed because it is the dichotomous moderator variable (T+ and T−).

TABLE 1 . Descriptive statistics and correlations of all variables for both experimental conditions.

Moderated Regression Analyses

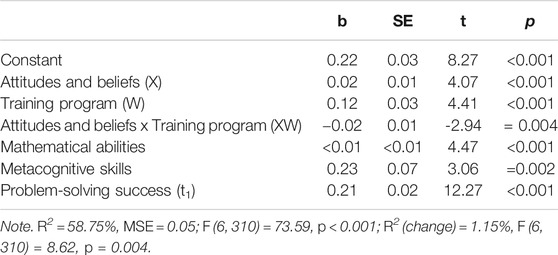

The hypothesis was tested with a moderated regression analysis using product terms from mean-centered predictor variables ( Hayes, 2018 ). This model imposed the constraint that any effect of attitudes and beliefs was independent of all other variables in the model. This was achieved by controlling for mathematical abilities, metacognitive skills, and problem-solving performance at Measurement Point 1. The estimated main effects and interaction terms are presented in Table 2 .

TABLE 2 . Results from the regression analysis examining the moderation of the effect of attitudes and beliefs on problem-solving success (t 2 ) by participation in the training program, controlling for mathematical abilities, metacognitive skills, and problem-solving success from the pretest.

When testing the hypothesis, we found a significant main effect of attitudes and beliefs, a significant main effect of the training program, and a significant moderator effect of the training on attitudes and beliefs as a predictor of problem-solving success. The main effect of the training program indicated that students who participated in the training performed better in the second WPST. The main effect of attitudes and beliefs showed that students with more positive attitudes and beliefs were more successful than students with negative attitudes and beliefs.

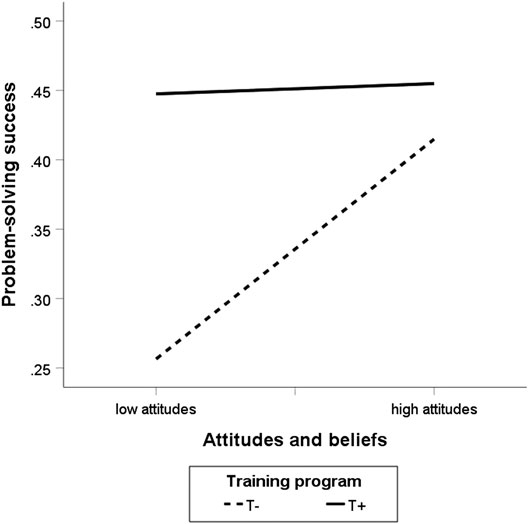

To further explore the interaction between attitudes and beliefs and the training program, we analyzed simple slopes at values of 1 SD above and 1SD below the means of attitudes and beliefs ( Hayes, 2018 ). As can be seen from the conditional expectations in Figure 2 , attitudes and beliefs did not affect the problem-solving success of students who participated in the training program. Attitudes and beliefs only had a positive effect on the problem-solving success of students who did not participate in the training.

FIGURE 2 . Moderator effect of the training program on problem-solving success at Measurement Point 2.

Our results confirm previous findings that the attitudes and beliefs of students correlate with their problem-solving performance. They indicate that this correlation can be moderated by student participation in a training program. Negative attitudes and beliefs did not affect the performance of students who participated in a problem-solving training program over several weeks. Whether the training program also causes a change in the attitudes and beliefs of the students over time has to be investigated in a follow-up study, which is planned with a longer intervention period with at least two measurements of attitudes and beliefs. A longer intervention period would have the advantage that attitudes develop depending on the individual experiences of a person ( Hannula, 2002 ; Lim and Chapman, 2015 ), for instance, when new experience is gathered or new knowledge is acquired (e.g., Ajzen, 2005 ).

Some limitations need to be considered when interpreting the results of the study. For example, the mitigating processes need to be investigated further. It is also unclear as to which components of the training are ultimately responsible for counteracting the effect of attitudes and beliefs. Although the study did not provide results in this regard, we assume that the following factors might have an effect: generating external representations, reflecting on the representations together as a group, and fostering an appreciative and constructive approach to mistakes. Further studies are needed to show whether and to what extent these factors actually attenuate the effect of attitudes and beliefs.

Furthermore, the measurement instruments for the control variables mathematical abilities and metacognitive skills were rather limited. If researchers are interested in understanding further effects of metacognitive skills, more aspects should be included. Furthermore, according to Lester et al. (1987), investigating attitudes and beliefs using a questionnaire is associated with disadvantages. How accurately students answer the questions depends on how objectively and accurately they can reflect on and assess their own attitudes. Misinterpretations and errors cannot be ruled out. The most serious disadvantage, however, is that data collection using an inventory can easily be assumed to have unjustified validity and reliability. For a deeper insight into the attitudes and beliefs of primary school students, qualitative interviews have to be implemented.

However, for the purpose of this study, it seems sufficient to consider the two control variables mathematical abilities and metacognitive abilities. We were able to ensure that the correlation between attitudes and beliefs and the mathematical performance of students was not influenced by these factors.

Regardless of the limitations, our study has some practical implications. Participation in the training program, independently of the mathematical abilities and text comprehension of students, reduced the influence of attitudes and beliefs on their performance. Thus, for teaching practice, it can be concluded that it is important not only to implement regular problem-solving activities in mathematics lessons, but also to encourage students to externalize and find their own solutions. The aim is to establish a teaching culture that promotes a variety of approaches and procedures, allows mistakes to be made, and makes mistakes a subject for learning. Reflecting on different possible solutions and also on mistakes helps students to progress. Thus, students develop a repertoire of external representations from which they can profit in the long term when solving problems.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology, University of Koblenz and Landau, Germany. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian. This study was also carried out in accordance with the guidelines for scientific studies in schools in the German state Rhineland-Palatinate (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen an Schulen in Rheinland-Pfalz), Aufsichts- und Dienstleistungsdirektion Trier. The protocol was approved by the Aufsichts- und Dienstleistungsdirektion Trier.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The project was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, grant number GK1561/1).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.525923/full#supplementary-material

1 This project was part of the first author’s PhD thesis

Adibnia, A., and Putt, I. J. (1998). Teaching problem solving to year 6 students: A new approach. Math. Educ. Res. J. 10 (3), 42–58. doi:10.1007/BF03217057

Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality and behavior . Maidenhead, United Kingdom: Open University Press .

Google Scholar

Ajzen, I. (1998). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Proc. 50 (2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Amarel, S. (1966). On the mechanization of creative processes. IEEE Spectr. 3 (4), 112–114. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.1966.5216589

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Awofala, A. O. A. (2014). Examining personalisation of instruction, attitudes toward and achievement in mathematics word problems among nigerian senior secondary school students. Ijemst 2 (4), 273–288. doi:10.18404/ijemst.91464

Boonen, A. J. H., van der Schoot, M., van Wesel, F., de Vries, M. H., and Jolles, J. (2013). What underlies successful word problem solving? A path analysis in sixth grade students. Contemporary Educ. psychol. 38 (3), 271–279. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.05.001

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., and Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: brain, mind, experience, and school . Washington, DC: National Academy Press .

Bransford, J. D., and Stein, B. S. (1993). The ideal problem solver: a guide for improving thinking, learning, and creativity . 2nd Edn. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman .

Breaugh, J. A., and Arnold, J. (2007). Controlling nuisance variables by using a matched-groups design. Organ. Res. Methods 10 (3), 523–541. doi:10.1177/1094428106292895

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research . 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press .

Charles, R. I., Lester, F. K., and O’Daffer, P. G. (1987). How to evaluate progress in problem solving . Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics .

Clercq, A. D., Desoete, A., and Roeyers, H. (2000). Epa2000: a multilingual, programmable computer assessment of off-line metacognition in children with mathematical-learning disabilities. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 32 (2), 304–311. doi:10.3758/BF03207799

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cox, R., and Brna, P. (1995). Supporting the use of external representation in problem solving: the need for flexible learning environments. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 6 (2–3), 239–302. .

Cox, R. (1999). Representation construction, externalised cognition and individual differences. Learn. InStruct. 9 (4), 343–363. doi:10.1016/S0959-4752(98)00051-6

De Corte, E., Op t Eynde, P., and Verschaffel, L. (2002). ““Knowing what to believe”: the relevance of students’ mathematical beliefs for mathematics education,” in Personal epistemology: the psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing . Editors B. K. Hofer, and P. R. Pintrich (New Jersey, United States: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers ), 297–320. doi:10.4324/9780203424964

De Corte, E., Verschaffel, L., and Op’t Eynde, P. (2000). “Self-regulation: a characteristic and a goal of mathematics education,” in Handbook of self-regulation . Editors P. R. Pintrich, M. Boekaerts, and M. Zeidner (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press ), 687–726.

de Corte, E., Verschaffel, L., and Pauwels, A. (1992). Solving compare problems: An eye movement test of Lewis and Mayer’s consistency hypothesis. J. Educ. Psychol. 84 (1), 85–94. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.1.85

Desoete, A., Roeyers, H., and De Clercq, A. (2003). Can offline metacognition enhance mathematical problem solving?. J. Educ. Psychol. 95 (1), 188–200. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.188

Di Martino, P. (2019). Pupils’ view of problems: the evolution from kindergarten to the end of primary school. Educ. Stud. Math. 100 (3), 291–307. doi:10.1007/s10649-018-9850-3

Duval, R. (1999). “Representation, vision, and visualization: cognitive functions in mathematical thinking. Basic issues for learning (ED466379),” in Proceedings of the twenty-first annual meeting of the north American chapter of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education XXI , Cuernavaca, Mexico , October 23–26, 1999 . Editors F. Hitt, and M. Santos ( ERIC ), 1, 3–26.

Eid, M., Gollwitzer, M., and Schmitt, M. (2011). Statistik und Forschungsmethoden: lehrbuch . [Statistics and research methods] . 2nd Edn. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz .

Goldin, G. A. (2003). “Affect, meta-affect, and mathematical belief structures,” in Beliefs: a hidden variable in mathematics education? . Editors G. C. Leder, E. Pehkonen, and G. Törner (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers ), 31, 59–72. doi:10.1007/0-306-47958-3_4

Goldin, G. A., Rösken, B., and Törner, G. (2009). “Beliefs—No longer a hidden variable in mathematical teaching and learning processes,” in Beliefs and attitudes in mathematics education . Editors J. Maasz, and W. Schloeglmann (Rotterdam, Netherlands; Sense Publishers ), 1–18.

Greevy, R., Lu, B., Silber, J. H., and Rosenbaum, P. (2004). Optimal multivariate matching before randomization. Biostatistics 5 (2), 263–275. doi:10.1093/biostatistics/5.2.263

Grigutsch, S., Raatz, U., and Törner, G. (1998). Einstellungen gegenüber Mathematik bei Mathematiklehrern. Jmd 19 (1), 3–45. doi:10.1007/BF03338859

Haffner, J., Baro, K., Parzer, P., and Resch, F. (2005). Heidelberger Rechentest (HRT 1-4): erfassung mathematischer Basiskompetenzen im Grundschulalter [Heidelberger Rechentest (HRT 1-4): assessment of basic mathematical skills at primary school age] . Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe .

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis . 7th Edn. London, United Kingdom: Pearson .

Hannula, M. S. (2002). Attitude towards mathematics: emotions, expectations and values. Educ. Stud. Math. 49 (1), 25–46. doi:10.1023/A:1016048823497

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach . 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press .

Hegarty, M., Mayer, R. E., and Green, C. E. (1992). Comprehension of arithmetic word problems: Evidence from students' eye fixations. J. Educ. Psychol. 84 (1), 76–84. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.1.76

Higgins, K. M. (1997). The effect of year-long instruction in mathematical problem solving on middle-school students’ attitudes, beliefs, and abilities. J. Exp. Educ. 66 (1), 5–28. doi:10.1080/00220979709601392

Kirsh, D. (2010). Thinking with external representations. AI Soc. 25 (4), 441–454. doi:10.1007/s00146-010-0272-8

Lester, F. K., and Cai, J. (2016). “Can mathematical problem solving be taught? Preliminary answers from 30 years of research,” in Posing and solving mathematical problems . Editors P. Felmer, E. Pehkonen, and J. Kilpatrick (Washington, DC: Springer ), 117–135. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28023-3_8

Lester, F. K., Garofalo, J., and Kroll, D. L. (1989). “Self-confidence, interest, beliefs, and metacognition: key influences on problem-solving behavior,” in Affect and mathematical problem solving . Editors D. B. McLeod, and V. M. Adams (Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag ), 75–88. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-3614-6_6

Lester, F. K., and Kroll, D. L. (1990). “Assessing student growth in mathematical problem solving,” in Assessing higher order thinking in mathematics . Editor G. Kulm (Washington, DC: AAAS Publication ), 53–70.

Lester, F. K. (1985). “Methodological considerations in research on mathematical problem-solving instruction,” in Teaching and learning mathematical problem solving: multiple research perspectives . Editor E. A. Silver (Mahwah NJ: Erlbaum ), 41–69.

Lienert, G. A., and Raatz, U. (1998). Testaufbau und Testanalyse [Test construction and test analysis] . 6th Edn. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz .

Lim, S. Y., and Chapman, E. (2015). Effects of using history as a tool to teach mathematics on students' attitudes, anxiety, motivation and achievement in grade 11 classrooms. Educ. Stud. Math. 90 (2), 189–212. doi:10.1007/s10649-015-9620-4

Mason, L., and Scrivani, L. (2004). Enhancing students' mathematical beliefs: an intervention study. Learn. InStruct. 14 (2), 153–176. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.01.002

Mayer, R. E., and Hegarty, M. (1996). “The process of understanding mathematical problems,” in The nature of mathematical thinking . Editors R. J. Sternberg, and T. Ben-Zeev (Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum ), 29–54.

Moore, R. T. (2012). Multivariate continuous blocking to improve political science experiments. Polit. Anal. 20 (4), 460–479. doi:10.1093/pan/mps025

M. S. Hannula, G. C. Leder, F. Morselli, M. Vollstedt, and Q. Zhang (Editors) (2019). Affect and mathematics education: fresh perspectives on motivation, engagement, and identity . New York, NY: Springer International Publishing . doi:10.1007/978-3-030-13761-8

Myers, A., and Hansen, C. H. (2012). Experimental psychology . 7th Edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth .

Newell, A., and Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall .

Norman, D. A. (1993). Things that make us smart: defending human attributes in the age of the machine . New York, NY: Perseus Books .

Nussbeck, F. W., Eid, M., and Lischetzke, T. (2006). Analysing multitrait-multimethod data with structural equation models for ordinal variables applying the WLSMV estimator: what sample size is needed for valid results?. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 59 (1), 195–213. doi:10.1348/000711005X67490

Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and classification . Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press .

Rasch, R. (2008). 42 Denk- und Sachaufgaben. Wie Kinder mathematische Aufgaben lösen und diskutieren [42 thinking and problem solving tasks. How children solve and discuss mathematical tasks] . 3rd Edn. Seelze-Velber, Germany: Kallmeyer .

Reisberg, D. (1987). “External representations and the advantages of externalizing one’s thought,” in The ninth annual conference of the cognitive science society , Seattle, WA , July 1, 1987 (Hove, United Kingdom: Psychology Press ), 281–293.

Reiss, K., Hellmich, F., and Thomas, J. (2002). “Individuelle und schulische Bedingungsfaktoren für Argumentationen und Beweise im Mathematikunterricht [Individual and educational conditioning factors for argumentation and evidence in mathematics teaching],” in Bildungsqualität von Schule: schulische und außerschulische Bedingungen mathematischer, naturwissenschaftlicher und überfachlicher Kompetenzen . Editors M. Prenzel, and J. Doll ( Weinheim, Germany: Beltz ), 51–64.

Reyes, L. H. (1984). Affective variables and mathematics education. Elem. Sch. J. 84 (5), 558–581. doi:10.1086/461384

Schnotz, W., Baadte, C., Müller, A., and Rasch, R. (2010). “Creative thinking and problem solving with depictive and descriptive representations,” in Use of representations in reasoning and problem solving: analysis and improvement . Editors L. Verschaffel, E. de Corte, T. de Jong, and J. Elen (Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge ), 11–35.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1985). Mathematical problem solving . Cambridge, MA: Academic Press .

Shaughnessy, J. M. (1985). Problem-solving derailers: The influence of misconceptions on problem-solving performance. In E. A. Silver (Hrsg.), Teaching and learning mathematical problem solving: Multiple research perspectives (S. 399 -415). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Stuart, E. A., and Rubin, D. B. (2008). “Best practices in quasi-experimental designs: matching methods for causal inference,” in Best practices in quantitative methods . Editor J. W. Osborne (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE ), 155–176.

Sturm, N. (2018). Problemhaltige Textaufgaben lösen: einfluss eines Repräsentationstrainings auf den Lösungsprozess von Drittklässlern [Solving word problems: influence of representation training on the problem-solving process of third-graders . Berlin, Germany: Springer . | Google Scholar

Sturm, N., and Rasch, R. (2015). “Forms of representation for solving mathematical word problems – development of an intervention study,” in Multidisciplinary research on teaching and learning . Editors W. Schnotz, A. Kauertz, H. Ludwig, A. Müller, and J. Pretsch (London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan ), 201–223.

Sturm, N., Rasch, R., and Schnotz, W. (2016). Cracking word problems with sketches, tables, calculations and reasoning: do all primary students benefit equally from using them? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 101, 519. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.317

Sturm, N. (2019). “Self-generated representations as heuristic tools for solving word problems,” in Implementation research on problem solving in school settings. Proceedings of the 2018 joint conference of ProMath and the GDM working group on problem solving . Editors A. Kuzle, I. Gebel, and B. Rott (Münster, Germany: WTM-Verlag ), 173–192.

Sturm, N., Wahle, C. V., Rasch, R., and Schnotz, W. (2015). “Self-generated representations are the key: the importance of external representations in predicting problem-solving success,” in Proceedings of the 39th conference of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education . Editors K. Beswick, T. Muir, and J. Wells ( Basingstoke, United Kingdom: PME ), 4, 209–216.

Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learn. InStruct. 4 (4), 295–312. doi:10.1016/0959-4752(94)90003-5

van Dijk, T. A., and Kintsch, W. (1983). Strategies of discourse comprehension . Cambridge, MA: Acadamic Press .

Verschaffel, L., De Corte, E., Lasure, S., Van Vaerenbergh, G., Bogaerts, H., and Ratinckx, E. (1999). Learning to solve mathematical application problems: a design experiment with fifth graders. Math. Think. Learn. 1 (3), 195–229. doi:10.1207/s15327833mtl0103_2

Verschaffel, L., Greer, B., and de Corte, E. (2000). Making sense of word problems . Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger .

Webb, N. L., Moses, B. E., and Kerr, D. R. (1977). Mathematical problem solving project technical report IV: developmental acctivities related to summative evaluation (1975–1976) : Mathematics Education Development Center. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University .

Zakaria, E., and Ngah, N. (2011). A preliminary analysis of students’ problem-posing ability and its relationship to attitudes towards problem solving. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 3 (9), 866–870.

Zakaria, E., and Yusoff, N. (2009). Attitudes and problem-solving skills in algebra among malaysian matriculation college students. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 8 (2), 232–245.

Keywords: attitudes and beliefs, word problem, training program design, problem-solving, problem-solving success, primary school, moderation effect analysis

Citation: Sturm N and Bohndick C (2021) The Influence of Attitudes and Beliefs on the Problem-Solving Performance. Front. Educ. 6:525923. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.525923