When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

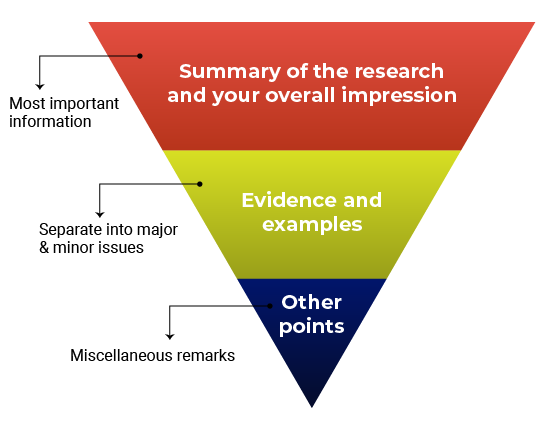

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

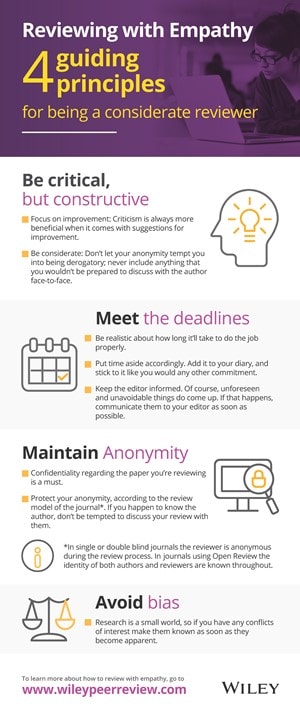

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The peer review process

Dmitry tumin, joseph drew tobias.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr. Joseph Drew Tobias, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Nationwide Children's Hospital, 700 Children's Drive, Columbus, Ohio 43205, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

The peer review process provides a foundation for the credibility of scientific findings in medicine. The following article discusses the history of peer review in scientific and medical journals, the process for the selection of peer reviewers, and how journal editors arrive at a decision on submitted manuscripts. To aid authors who are invited to revise their manuscripts for further consideration, we outline steps for considering reviewer comments and provide suggestions for organizing the author's response to reviewers. We also examine ethical issues in peer review and provide recommendations for authors interested in becoming peer reviewers themselves.

Key words: Manuscript review process, manuscript submission, peer review

Introduction

The review of research articles by peer experts prior to their publication is considered a mainstay of publishing in the medical literature.[ 1 , 2 ] This peer review process serves at least two purposes. For journal editors, peer review is an important tool for evaluating manuscripts submitted for publication. Reviewers assess the novelty and importance of the study, the validity of the methods, including the statistical analysis, the quality of the writing, the presentation of the data, and the connections drawn between the study findings and the existing literature. For authors, peer review is an important source of feedback on scientific writing and study design, and may aid in professionalization of junior researchers still learning the conventions of their field. Nevertheless, peer review can be frustrating, intimidating, or mysterious. This can deter authors from publishing their work or lead them to seek publication in less credible venues that use less rigorous peer review or do not subject manuscripts to peer review at all. In this article, we trace the origins of the scientific peer review system, explain its contemporary workings, and present authors with a brief guide on shepherding their manuscripts through peer review in medical journals.

The History of Scientific Peer Review

The introduction of peer review has been popularly attributed to the Royal Society of Edinburg, which compiled a collection of articles that had undergone peer review in 1731.[ 2 , 3 ] However, this initial process did not meet the criteria of peer review in its modern form, and well into the twentieth century, external and blinded peer review was still far from a requisite for scientific publication. Albert Einstein protested to the editor of an American journal in 1936 that his article was sent out for review, whereas this was not the practice of the German journals to which he had previously contributed.[ 4 ] Nevertheless, by the 1960s, the scientific value of peer review was becoming widely accepted, and in recent years, publication in a peer-reviewed journal has become a standard metric of scientific productivity (for the researchers) and validity (for the study).[ 5 , 6 ] In fact, publication in peer-reviewed quality journals is used to evaluate the quality of research during the academic promotion process. Today, peer review continues to evolve with the introduction of open review (reviewer comments posted publicly with the final article), postpublication review (reviews solicited from readers in an open forum after article publication), and journal review networks (where reviews are transferred from one journal to another when an article is rejected).[ 7 , 8 , 9 ] The constant at the center of this change remains the individual reviewer, who is asked to contribute their expertise to evaluating a manuscript that may or may not ever be shared with a wider scientific audience.

Reviewer Selection

The opacity of the peer review process is due, in part, to the anonymity of the reviewers and authors' lack of familiarity with how reviewers are selected. Typically, reviewers are selected by an editor of the journal, although depending on the size and organization of the journal, this may be the Editor-in-Chief, an Associate Editor, a Managing Editor, or an Editorial Assistant. Some journals permit authors to suggest their own reviewers, although the extent to which editors use these suggestions is variable. Authors may also be asked specifically or allowed to oppose reviewers, if they feel that certain scholars cannot grant their manuscript an unbiased hearing. Again, it is at the editors' discretion whether these requests are heeded. It has been suggested that these “opposed” reviewers may even be deliberately selected to ensure critical evaluation of a controversial manuscript. Alternatively, for very specific and narrow subject areas, there may be a limited number of appropriately qualified reviewers.

In general, reviewers may be of any academic rank and from a wide range of medical disciplines. A reviewer may be selected for their expertise in the topic of the study, but also for their general methodological expertise, or because they have been a reliable reviewer for the journal in the past. Qualified reviewers may not be invited if they cannot be reached by the editorial team, if they tend to submit late or uninformative reviews, or if they are too closely connected with the manuscript authors (e.g., colleagues at the same institution) and therefore may not provide an unbiased review. The reviewers initially selected by the editors may decline the invitation to review, mandating that the editors seek other reviewers. Unfortunately, this process of waiting for a response from the initial invitation to review (aside from the time taken to review) is one of the more common causes resulting in a delay in getting a response from the journal when a manuscript is submitted. The invited reviewer may pass the review on to a junior faculty member to allow them to participate and experience the academic peer review process. This may be performed with the permission of the editor, and noted after the review is submitted to the editor when the invited reviewer identifies that another person has participated in the process.

The initially received reviews may conflict with one another, leading the editors to cast a wider net for experts who will agree to review a submission. Because many factors may delay the completion of the review process, editors may proactively invite more reviews than they require and decide on the manuscript after a minimum number of reviews have been completed. The use of email and the internet has greatly facilitated communication for the review process, which used to be accomplished via telephone and postal mail. In most instances, an initial email is sent to the reviewer inquiring regarding their availability and interest. They are then asked to agree to review, at which time, a secondary email with a link to the journal site, the manuscript, and the review forms is sent.

How Reviewers Assess a Manuscript

From the reviewer's perspective, participation in the review process begins with an invitation from the journal editors to consider reviewing a submitted manuscript. If they accept, the reviewers will be able to access the submitted manuscript files, and sometimes the authors' cover letter, and other article metadata (e.g., the authors' list of preferred reviewers, figures, tables, etc.). Some journals ask reviewers to complete a structured questionnaire regarding the manuscript, rating its attributes on a numeric scale, or answering specific questions about each article section. All journals permit the submission of free-response evaluations. It is these evaluations that typically carry the greatest weight in the editors' final decision. The free-text reviewer reports also give the authors specific instructions about revising their manuscript and responding to the concerns that are raised. Reviewers may also submit confidential free-response comments to the editors (not seen by the authors) and indicate to the editors if they would be willing to review a revised version of the manuscript. In the end, the reviewer is asked to indicate their final recommendation to accept the manuscript without changes, accept after minor revisions, reconsider after major revisions, or reject. Some journals may offer additional variations on these recommendations, such as “reject but allow resubmission,” discussed below.

Regardless of the requested format for reviews, reviewers will typically evaluate several key aspects of submitted manuscripts. For original research studies, these will include the importance of the research question, the rigor of the methods, the completeness, accuracy, and novelty of the study and its results, and the validity of conclusions drawn from the data. The presentation of the manuscript, including the writing style, structure, grammar, and syntax also determine how the manuscript is received by the reviewers. Although the study design and results may be valid, these findings may be lost if the presentation is not precise or if there are grammar and spelling errors.

Reviewers also consider whether the study adds to existing knowledge in the field, whether it was ethically conducted, and whether it may be subject to any conflicts of interest. The editor and the reviewers also evaluate the study content and decide whether it is valuable and relevant to the readers of the journal. Although the study may be valid and well performed, it may be decided that the subject matter fits more appropriately in a journal of a different specialty. Along those lines, there may be overlap in the interests and fit of journals in different specialties, so that common topics in anesthesiology research may be of interest to journals from surgical specialties, pain medicine, or healthcare quality and patient safety, depending on the article content.

Some reviewers may submit their comments in paragraph form, building a narrative of the study's strengths and weaknesses section by section, whereas others may submit a short summary of the study followed by a list of criticisms or suggested corrections. Less commonly, reviewers may annotate the original manuscript with specific changes and questions or using the track-changes function of the word-processing software. Although the reviewers may recommend a specific editorial decision (e.g., recommend accepting an article with revisions, recommend rejection) in their comments to authors, this is generally discouraged by most journals and does not override the final decision reached by the editorial team. The ultimate decision generally resides with the section editor or the editor-in-chief, once they have seen and evaluated the comments of the reviewers. Depending on the format of the journal, the manuscript may be reviewed by one to five individuals. When there are specific statistical questions or advanced methods used, a separate review of the analytic methods may be required. For high-profile journals with high Impact Factors, a recommendation to accept may be required from all reviewers to receive a favorable editorial decision. At times, if there is a split decision, an additional reviewer or member of the editorial board may be asked to evaluate the manuscript to break the tie.

Almost all journals practice blinded review, where the reviewers' identities are not revealed to the authors. Double-blind review, where authors' identities are concealed from reviewers, although previously uncommon in medical journals, has been increasingly used. The editors communicate their decision and reviewers' evaluations to the authors in a decision letter (e-mail), informing of manuscript acceptance or rejection.

Reviews and the Editorial Decision

The comments submitted by external reviewers are collected by the editorial team and considered when determining the overall decision on the submitted article. The reviews may be read directly by the Editor-in-Chief, or by one or more Associate or Section Editors. The first editor reading the reviews might provide a recommendation that is then considered by the more senior editor; or the editors may convene to discuss the reviews and reach a decision as a group. In some journals, editors may write their own summary of the reviewers' criticism (sometimes adding their own) or may point out the critiques they consider most important to their decision. In other journals, editors weigh the number of positive and negative reviews or may reject an article unless all reviewers endorse its acceptance or revision.

Based on the external reviews and their own reading of the manuscript, the editors will reach one of several options regarding the manuscript. Unconditional acceptance of an article on its first submission to a journal (without any requested revisions) is very rare. Sometimes, articles will be conditionally accepted or accepted with minor revisions, meaning that the editors wish the authors to make changes to their manuscript based on the reviewers' comments but will not send the revised manuscript for a further round of external review. Rather, if the comments are generally minor, the editor will ensure that the comments are appropriately addressed in the authors' revision. The more common decision is “major revision,” where editors are willing to consider a revised version of the article but will subject it to further external review, by the original reviewers, a new set of reviewers, or a combination of both. Some journals also use a “reject and resubmit” decision, indicating lower enthusiasm for a resubmitted version of the article but still permitting resubmission, perhaps in an alternative format (e.g., brief report or letter to the editor, vs. full article) or with extensive revisions. For this latter decision, a full review will be accomplished as the revised manuscript is handled in much the same way as a new submission.

If the editors feel an article is a poor fit for their journal or falls too far below its standards, they may reject submissions outright without sending the manuscript for external review. This “desk reject” should not be confused with articles being “unsubmitted” by a managing editor or editorial assistant. The latter can happen due to style or formatting issues with the initial submission, which the author is asked to correct before the manuscript proceeds to review. Having a manuscript “unsubmitted” does not preclude resubmission of a corrected manuscript and is unlikely to affect reviewer assessment and, eventually, editorial decision.

Revising the Manuscript

When the initial editorial decision is positive, but not an unconditional acceptance, authors may elect to revise their manuscript and resubmit it to the same journal with a point-by-point response to the reviewers (discussed in the next section). The primary aim of the authors for this revision should be to address the criticisms and concerns raised during the initial review. Yet, this may be easier said than done when faced with conflicting recommendations, hostile reviews, or simply a large number of suggestions to be accommodated within a strict manuscript word limit. To streamline the process of responding to reviews, we offer the following roadmap as a suggestion.

Address the “fatal flaws”

Reviewers or editors may point out critical weaknesses of the study that prevent it from drawing the intended conclusions or even any conclusions at all. For example, an inaccuracy in the data, a bias in patient recruitment, a limitation of sample size, or a lack of follow-up may be so severe that the manuscript cannot provide credible evidence on the treatment or exposure it is meant to study. In particular, a lack of appropriate ethical approval would disqualify a study from publication, no matter how methodologically rigorous it may have been. In systematic reviews and analyses of existing databases, prior publication of a near-identical paper by a different group may also fundamentally preclude a paper from acceptance. On the rare occasions when the paper's central conclusions are found invalid and cannot be corrected through new analysis or a different framing of the authors' argument, reconceiving the study may be a better approach than attempting to revise and resubmit. At other times, some of these issues may be approached and the editor and reviewers satisfied by adding text to the discussion outlining the limitations of the current study. This may allow authors to acknowledge the concerns expressed by the reviewers and yet not redo their study from the beginning.

Amend the data analysis

More commonly, reviewers ask for changes to the data analysis without implying that these requests invalidate the entire study. We recommend making these changes before any further edits to the manuscript, because the intent is often to see if the paper's original findings are robust. In the best case scenario, any additional analysis will only confirm and strengthen the central conclusions. However, additional analyses sometimes reveal contradicting findings, which the authors should frankly address in the revised manuscript, by pointing out the contradiction and speculating about why different analyses of their data may have reached different conclusions. Especially when the study design was prospectively registered, the authors should explain in the manuscript which analyses were planned a priori and which were added post hoc . In these studies, authors should also avoid changing the pre-specified primary outcome, which would have been used for any a priori power or sample size calculation.

Decline infeasible or inappropriate suggestions

Some requests may not be feasible, for example, when requested data were not collected for a prospective study, or when collecting the data would mean starting chart review from scratch for a retrospective study. At other times, it may not be feasible to comply with the reviewers' requests if they disagree with the study type, the study cohort, or make other requests that would require a new or different study to address. Reviewers could also request changes to the statistical analysis that are not appropriate for the data at hand or for the study aims. In these cases, authors have the choice of rebutting the reviewers' comments while making no change in their manuscript, but an argumentative revision that leans too heavily on this option may be received poorly on re-review, resulting in rejection of the manuscript. In our experience, authors may be successful in responding to the reviews while rebutting one or two of the reviewers' suggestions, but a legitimate argument must be made for the rebuttal, and the reasons clearly stated.

Explain the study rationale and methods

Having completed the revision of the data analysis, authors should check that their methods section includes a complete and correct explanation of how the data were collected and explains how the analysis was performed. It may be appropriate to end the introduction by stating the hypothesis of the study. In the methods section, reviewers will often ask about the ethical committee approval of the study, the site(s) where the study was conducted, patient inclusion and exclusion criteria, the consent process, the procedures involved and the protocol for anesthetic management, and the specific data points that were collected during the study. For prospective clinical studies, authors should also indicate whether the study was submitted to a trial registry (such as ClinicalTrials.gov), and whether this was done before or after study enrollment had started. Clearly stated ethical approval and trial registration information must be provided for all submissions. Explanations may be sought if the editors and reviewers believe that the study did not meet standards for ethical approval, patient consent, or trial registration. Other requests related to methods may ask to clarify how the primary and secondary aims outlined in the introduction were addressed in the analysis, and how the sample size was determined, whether based on a statistical power analysis or logistical considerations (e.g., how many patients could be recruited with available resources). When a statistical power analysis is performed, reviewers may ask for more detail about the assumptions of this analysis and any supporting data from pilot studies or previous publications.

Check the conclusions and limitations

Having revised the introduction, methods, and results, the authors should revise the discussion to make any changes to the conclusions required by new or different study findings. We recommend that authors start the discussion with a review of what the study found, and then discuss how the study findings relate to similar work that has been previously published. An excessively long discussion does not ensure that a study will be published and, in fact, may detract from the quality of the manuscript. For a scientific study (retrospective or prospective), the discussion should not read like a comprehensive review of the literature. Typically, the discussion of study limitations will be expanded in the revised manuscript to include additional study weaknesses pointed out by reviewers, acknowledge suggested changes that could not be made to the study methods, and mention other suggestions for future studies that would build on the current results or answer questions left unanswered by the current study. Reviewers may ask that the conclusions be more specific in addressing the primary aim or hypothesis of the study (stated in the introduction), but they may also encourage authors to go further afield in their discussion, connecting their findings to results from previous publications and describing how their findings support or challenge current clinical practice.

Writing the Response to Reviewers

As seen above, manuscript revision can require more writing and (re)analysis than even the initial submission. Therefore, the aim of the revision memo (response to reviewers) is to summarize for the editors and reviewers how each change addresses the concerns raised on the initial review. This document is handled differently by different journals; some require it to be uploaded as a separate file, others require that the revision memo be entered in a text-box during the online submission process, and still others require that the response to review be included in the cover letter for the resubmitted manuscript. Therefore, authors should pay close attention to the decision letter and its instructions as to how they should submit their response to reviewers and how they should refer to manuscript edits in the revision memo (e.g., by page number, by line number, or copying sections of the revised manuscript into the memo).

Typically, the reviewers' comments should be copied and entered in the response memo so that each comment is numbered and the response clearly listed after it, in a different font style or color. It is equally important to determine how the journal would like the changes tracked in the revised manuscript. Some journals will ask that the authors use the track-changes mode in the word processing software, whereas others may ask for changes to be highlighted or be added in a different color font. Deleted manuscript text may need to be shown in strike-through font or simply removed from the revised submission, depending on the journal. Journals may ask for two copies of the revised manuscript: one showing the changes and one in a clean format that is ready for copyediting.

A typical revision memo will include a short paragraph acknowledging the editorial decision and reviewer comments and briefly summarizing key changes made to the manuscript. This would be followed by a numbered list of comments from the editors and reviewers (as received in the decision letter), with the authors' response to each one. Although not all reviewers and editors submit their comments as a numbered list, the authors may want to break up long sections or paragraphs of the reviews into shorter, numbered comments, to separately describe how each one was addressed in the revision. The authors' responses need not be excessively ingratiating but should respect the reviewers' effort in evaluating the manuscript, and concisely explain what was changed or why a change was not or could not be made. Different reviewers may have conflicting recommendations for revision. This may be as simple as one asking for a more concise definition of a method while another asking for a more detailed explanation. With conflicting reviews, the authors may consider taking the recommendation that is endorsed in the editor's comments (if this is provided), the one that is best aligned with the study aims, or the one that best matches the methods and writing style used in other contemporary papers in the field; and explaining this rationale when responding to the reviewers.

What to Do with a Rejected Manuscript

Based on reviewer reports or their own judgment, editors may reject a manuscript with no option to resubmit. It is essential to read the decision letter closely as some journals will state that they cannot publish a manuscript in its current form but offer to consider a new submission of a substantially revised manuscript (“reject and resubmit,” as mentioned above, in contrast to “revise and resubmit”). When the manuscript is rejected with no option of resubmission, authors may appeal this decision, but this option is rarely exercised and may not change the editors' decision. Appeals are also generally only successful when made by experienced and recognized scholars in the field.

Unless the study is discovered to be so flawed as to preclude publication in any venue, authors will usually consider submitting it to another journal after the initial rejection. Taking a single rejection and tabling a manuscript without further submission is rarely a good option. It is possible that multiple rejections will precede an eventual acceptance for valuable work. Given the amount of time taken to devise, implement, and up a study, we encourage authors to consider resubmission to a new journal, if the study is well conceived and addresses an important problem or question. In this case, the criticisms in the initial review are not binding, but still worth the authors' consideration. Particularly, authors should address any major flaws in the study's approach and conclusions (distinct from reviewers' preferences for additional data analysis unrelated to the primary aims), and correct any factual, spelling, or grammatical errors prior to resubmission. Adding recommended secondary analyses could sometimes strengthen the next submission, although just as often, the reviewers at the next journal may find these additional analyses superfluous, and will have their own set of analyses to recommend.

Becoming a Reviewer

Like any complex skill, navigating the peer review process is best learned through repetition. Becoming a peer reviewer for scientific journals is an important way to hone this skill, as well as providing a service to the scientific community, and adding to one's academic credentials as an expert whose opinion is sought by journal editors. The most common entry point to becoming a reviewer is through scientific publication; the authors of published articles can be contacted by another journal to provide a review on a related submission. One's expertise in a specific area may be noted by the editor who performs a topic search of key words when looking for reviewers. Alternatively, editors and associate editors may call on colleagues who they know are recognized experts in a particular field. Academic mentorship is also important, as mentors may ask junior colleagues and faculty to help them with reviewing article submissions, or may pass their name along to journal editors to be considered for inclusion in the reviewer pool. Once one has successfully reviewed for a journal, they are frequently called upon to review other submissions, especially if their review was returned in a timely manner. Many journals will give a specific timeframe within which the review is to be completed, while others will not. In most cases, a response within 2–4 weeks is considered acceptable. Some journals have now started editorial fellowships that aim to provide an immersive experience in the peer review and publishing process for early-career scientists. Lastly, researchers wishing to become peer reviewers may contact journal editors themselves, or register reviewer accounts in journal online submission systems. Although the general structure of peer review reports is described above, more specific guidance on performing peer review is available in other publications.[ 10 , 11 ]

Peer Review Ethics

Authors, reviewers, and editors have a shared responsibility for the ethical conduct of peer review. This is necessary to sustain the professional and public trust in peer review, as a system of evaluation that is accurate, constructive, and free from bias. Recently reported ethics violations have included authors misrepresenting the identity of suggested reviewers, reviewers plagiarizing a manuscript sent to them for review or recommending its rejection and then conducting a similar study, and editors inappropriately pressuring authors to cite articles published in their journal.[ 12 , 13 , 14 ] Some journals and publishers have also been criticized for circumventing the peer review process for submitted manuscripts.[ 15 ] For reviewers, it is most important that they be unbiased and not have any hidden agendas or personal vendettas to settle. For authors, ethical conduct in peer review includes disclosing the study's ethics committee approval, trial registration, and consent process; disclosing any related or overlapping prior publications; disclosing any actual or potential conflicts of interest; and submitting the manuscript only to one journal. These requirements are typically stated in the journal's guidelines for authors, and may need to be acknowledged in the cover letter accompanying the manuscript. In responding to reviews, authors should also carefully consider whether their revisions still fall within the scope of the ethics committee approval for the study and the informed consent that was obtained, and whether the revised manuscript remains faithful to the aims and study design of any pre-registered trial protocol.

Scientific research is not complete until it is published, but not all research can or should be published. It falls to peer-review to determine the difference. By engaging with the process of peer review, authors can improve the quality of their work as well as gain confidence that it is published in a reputable medium. Furthermore, the fact that a study has been peer reviewed will increase its stature and potential for recognition. However, the peer review process does not assure this. Although responding to reviews can be challenging, we hope that the suggestions sketched out in this article will help authors plan their approach to manuscript revision and resubmission. We also encourage authors to participate in this process as reviewers, so that the labor of peer review is properly shared among the community of scientists.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- 1. Bornmann L. Scientific peer review. Ann Rev Inf Sci Technol. 2011;45:197–245. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Boswell MV, Hirsch JA. Medical journal peer review: Process and bias. Pain Physician. 2015;18:E1–14. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Csiszar A. Peer review: Troubled from the start. Nature. 2016;532:306–8. doi: 10.1038/532306a. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Kennefick D. Einstein versus the physical review. Phys Today. 2005;58:43–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Pagel PS, Hudetz JA. Scholarly productivity and national institutes of health funding of foundation for anesthesia education and research grant recipients: Insights from a bibliometric analysis. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:683–91. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000737. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Geyer ED, Tumin D, Miller R, Cartabuke RS, Tobias JD. Progress to publication of survey research presented at anesthesiology society meetings. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018 doi: 10.1111/pan.13466. [Epub ahead of print] [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Callaway E. Open peer review finds more takers. Nature. 2016;539:343. doi: 10.1038/nature.2016.20969. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Teixeira da Silva JA, Dobránszki J. Problems with traditional science publishing and finding a wider niche for post-publication peer review. Account Res. 2015;22:22–40. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2014.899909. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Kirk AD, Malchesky PS, Shapiro R, Webber SA, Hirsch HH, Marty FM, et al. Introducing the Wiley transplant peer review network. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2505–7. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13965. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Spigt M, Arts IC. How to review a manuscript. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1385–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. McDermott S, Turk MA. The art of manuscript review - and manuscript development. Disabil Health J. 2017;10:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.10.009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Qi X, Deng H, Guo X. Characteristics of retractions related to faked peer reviews: An overview. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93:499–503. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-133969. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Gross C. Scientific misconduct. Annu Rev Psychol. 2016;67:693–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033437. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Ioannidis JP. A generalized view of self-citation: Direct, co-author, collaborative, and coercive induced self-citation. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.11.008. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Bohannon J. Who's afraid of peer review? Science. 2013;342:60–5. doi: 10.1126/science.2013.342.6154.342_60. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (388.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

You are using an outdated browser . Please upgrade your browser today !

What Is Peer Review and Why Is It Important?

It’s one of the major cornerstones of the academic process and critical to maintaining rigorous quality standards for research papers. Whichever side of the peer review process you’re on, we want to help you understand the steps involved.

This post is part of a series that provides practical information and resources for authors and editors.

Peer review – the evaluation of academic research by other experts in the same field – has been used by the scientific community as a method of ensuring novelty and quality of research for more than 300 years. It is a testament to the power of peer review that a scientific hypothesis or statement presented to the world is largely ignored by the scholarly community unless it is first published in a peer-reviewed journal.

It is also safe to say that peer review is a critical element of the scholarly publication process and one of the major cornerstones of the academic process. It acts as a filter, ensuring that research is properly verified before being published. And it arguably improves the quality of the research, as the rigorous review by like-minded experts helps to refine or emphasise key points and correct inadvertent errors.

Ideally, this process encourages authors to meet the accepted standards of their discipline and in turn reduces the dissemination of irrelevant findings, unwarranted claims, unacceptable interpretations, and personal views.

If you are a researcher, you will come across peer review many times in your career. But not every part of the process might be clear to you yet. So, let’s have a look together!

Types of Peer Review

Peer review comes in many different forms. With single-blind peer review , the names of the reviewers are hidden from the authors, while double-blind peer review , both reviewers and authors remain anonymous. Then, there is open peer review , a term which offers more than one interpretation nowadays.

Open peer review can simply mean that reviewer and author identities are revealed to each other. It can also mean that a journal makes the reviewers’ reports and author replies of published papers publicly available (anonymized or not). The “open” in open peer review can even be a call for participation, where fellow researchers are invited to proactively comment on a freely accessible pre-print article. The latter two options are not yet widely used, but the Open Science movement, which strives for more transparency in scientific publishing, has been giving them a strong push over the last years.

If you are unsure about what kind of peer review a specific journal conducts, check out its instructions for authors and/or their editorial policy on the journal’s home page.

Why Should I Even Review?

To answer that question, many reviewers would probably reply that it simply is their “academic duty” – a natural part of academia, an important mechanism to monitor the quality of published research in their field. This is of course why the peer-review system was developed in the first place – by academia rather than the publishers – but there are also benefits.

Are you looking for the right place to publish your paper? Find out here whether a De Gruyter journal might be the right fit.

Besides a general interest in the field, reviewing also helps researchers keep up-to-date with the latest developments. They get to know about new research before everyone else does. It might help with their own research and/or stimulate new ideas. On top of that, reviewing builds relationships with prestigious journals and journal editors.

Clearly, reviewing is also crucial for the development of a scientific career, especially in the early stages. Relatively new services like Publons and ORCID Reviewer Recognition can support reviewers in getting credit for their efforts and making their contributions more visible to the wider community.

The Fundamentals of Reviewing

You have received an invitation to review? Before agreeing to do so, there are three pertinent questions you should ask yourself:

- Does the article you are being asked to review match your expertise?

- Do you have time to review the paper?

- Are there any potential conflicts of interest (e.g. of financial or personal nature)?

If you feel like you cannot handle the review for whatever reason, it is okay to decline. If you can think of a colleague who would be well suited for the topic, even better – suggest them to the journal’s editorial office.

But let’s assume that you have accepted the request. Here are some general things to keep in mind:

Please be aware that reviewer reports provide advice for editors to assist them in reaching a decision on a submitted paper. The final decision concerning a manuscript does not lie with you, but ultimately with the editor. It’s your expert guidance that is being sought.

Reviewing also needs to be conducted confidentially . The article you have been asked to review, including supplementary material, must never be disclosed to a third party. In the traditional single- or double-blind peer review process, your own anonymity will also be strictly preserved. Therefore, you should not communicate directly with the authors.

When writing a review, it is important to keep the journal’s guidelines in mind and to work along the building blocks of a manuscript (typically: abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, references, tables, figures).

After initial receipt of the manuscript, you will be asked to supply your feedback within a specified period (usually 2-4 weeks). If at some point you notice that you are running out of time, get in touch with the editorial office as soon as you can and ask whether an extension is possible.

Some More Advice from a Journal Editor

- Be critical and constructive. An editor will find it easier to overturn very critical, unconstructive comments than to overturn favourable comments.

- Justify and specify all criticisms. Make specific references to the text of the paper (use line numbers!) or to published literature. Vague criticisms are unhelpful.

- Don’t repeat information from the paper , for example, the title and authors names, as this information already appears elsewhere in the review form.

- Check the aims and scope. This will help ensure that your comments are in accordance with journal policy and can be found on its home page.

- Give a clear recommendation . Do not put “I will leave the decision to the editor” in your reply, unless you are genuinely unsure of your recommendation.

- Number your comments. This makes it easy for authors to easily refer to them.

- Be careful not to identify yourself. Check, for example, the file name of your report if you submit it as a Word file.

Sticking to these rules will make the author’s life and that of the editors much easier!

Explore new perspectives on peer review in this collection of blog posts published during Peer Review Week 2021

[Title image by AndreyPopov/iStock/Getty Images Plus

David Sleeman

David Sleeman worked as a Senior Journals Manager in the field of Physical Sciences at De Gruyter.

You might also be interested in

Academia & Publishing

Space for Study: The Art and Science of Modern Library Creation

Rethinking accessible research with subscribe to open: the story so far, poised for a great future an open access week interview with colleen campbell, visit our shop.

De Gruyter publishes over 1,300 new book titles each year and more than 750 journals in the humanities, social sciences, medicine, mathematics, engineering, computer sciences, natural sciences, and law.

Pin It on Pinterest

Page Content

Overview of the review report format, the first read-through, first read considerations, spotting potential major flaws, concluding the first reading, rejection after the first reading, before starting the second read-through, doing the second read-through, the second read-through: section by section guidance, how to structure your report, on presentation and style, criticisms & confidential comments to editors, the recommendation, when recommending rejection, additional resources, step by step guide to reviewing a manuscript.

When you receive an invitation to peer review, you should be sent a copy of the paper's abstract to help you decide whether you wish to do the review. Try to respond to invitations promptly - it will prevent delays. It is also important at this stage to declare any potential Conflict of Interest.

The structure of the review report varies between journals. Some follow an informal structure, while others have a more formal approach.

" Number your comments!!! " (Jonathon Halbesleben, former Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Informal Structure

Many journals don't provide criteria for reviews beyond asking for your 'analysis of merits'. In this case, you may wish to familiarize yourself with examples of other reviews done for the journal, which the editor should be able to provide or, as you gain experience, rely on your own evolving style.

Formal Structure

Other journals require a more formal approach. Sometimes they will ask you to address specific questions in your review via a questionnaire. Or they might want you to rate the manuscript on various attributes using a scorecard. Often you can't see these until you log in to submit your review. So when you agree to the work, it's worth checking for any journal-specific guidelines and requirements. If there are formal guidelines, let them direct the structure of your review.

In Both Cases

Whether specifically required by the reporting format or not, you should expect to compile comments to authors and possibly confidential ones to editors only.

Following the invitation to review, when you'll have received the article abstract, you should already understand the aims, key data and conclusions of the manuscript. If you don't, make a note now that you need to feedback on how to improve those sections.

The first read-through is a skim-read. It will help you form an initial impression of the paper and get a sense of whether your eventual recommendation will be to accept or reject the paper.

Keep a pen and paper handy when skim-reading.

Try to bear in mind the following questions - they'll help you form your overall impression:

- What is the main question addressed by the research? Is it relevant and interesting?

- How original is the topic? What does it add to the subject area compared with other published material?

- Is the paper well written? Is the text clear and easy to read?

- Are the conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented? Do they address the main question posed?

- If the author is disagreeing significantly with the current academic consensus, do they have a substantial case? If not, what would be required to make their case credible?

- If the paper includes tables or figures, what do they add to the paper? Do they aid understanding or are they superfluous?

While you should read the whole paper, making the right choice of what to read first can save time by flagging major problems early on.

Editors say, " Specific recommendations for remedying flaws are VERY welcome ."

Examples of possibly major flaws include:

- Drawing a conclusion that is contradicted by the author's own statistical or qualitative evidence

- The use of a discredited method

- Ignoring a process that is known to have a strong influence on the area under study

If experimental design features prominently in the paper, first check that the methodology is sound - if not, this is likely to be a major flaw.

You might examine:

- The sampling in analytical papers

- The sufficient use of control experiments

- The precision of process data

- The regularity of sampling in time-dependent studies

- The validity of questions, the use of a detailed methodology and the data analysis being done systematically (in qualitative research)

- That qualitative research extends beyond the author's opinions, with sufficient descriptive elements and appropriate quotes from interviews or focus groups

Major Flaws in Information

If methodology is less of an issue, it's often a good idea to look at the data tables, figures or images first. Especially in science research, it's all about the information gathered. If there are critical flaws in this, it's very likely the manuscript will need to be rejected. Such issues include:

- Insufficient data

- Unclear data tables

- Contradictory data that either are not self-consistent or disagree with the conclusions

- Confirmatory data that adds little, if anything, to current understanding - unless strong arguments for such repetition are made

If you find a major problem, note your reasoning and clear supporting evidence (including citations).

After the initial read and using your notes, including those of any major flaws you found, draft the first two paragraphs of your review - the first summarizing the research question addressed and the second the contribution of the work. If the journal has a prescribed reporting format, this draft will still help you compose your thoughts.

The First Paragraph

This should state the main question addressed by the research and summarize the goals, approaches, and conclusions of the paper. It should:

- Help the editor properly contextualize the research and add weight to your judgement

- Show the author what key messages are conveyed to the reader, so they can be sure they are achieving what they set out to do

- Focus on successful aspects of the paper so the author gets a sense of what they've done well

The Second Paragraph

This should provide a conceptual overview of the contribution of the research. So consider:

- Is the paper's premise interesting and important?

- Are the methods used appropriate?

- Do the data support the conclusions?

After drafting these two paragraphs, you should be in a position to decide whether this manuscript is seriously flawed and should be rejected (see the next section). Or whether it is publishable in principle and merits a detailed, careful read through.

Even if you are coming to the opinion that an article has serious flaws, make sure you read the whole paper. This is very important because you may find some really positive aspects that can be communicated to the author. This could help them with future submissions.

A full read-through will also make sure that any initial concerns are indeed correct and fair. After all, you need the context of the whole paper before deciding to reject. If you still intend to recommend rejection, see the section "When recommending rejection."

Once the paper has passed your first read and you've decided the article is publishable in principle, one purpose of the second, detailed read-through is to help prepare the manuscript for publication. You may still decide to recommend rejection following a second reading.

" Offer clear suggestions for how the authors can address the concerns raised. In other words, if you're going to raise a problem, provide a solution ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Preparation

To save time and simplify the review:

- Don't rely solely upon inserting comments on the manuscript document - make separate notes

- Try to group similar concerns or praise together

- If using a review program to note directly onto the manuscript, still try grouping the concerns and praise in separate notes - it helps later

- Note line numbers of text upon which your notes are based - this helps you find items again and also aids those reading your review

Now that you have completed your preparations, you're ready to spend an hour or so reading carefully through the manuscript.

As you're reading through the manuscript for a second time, you'll need to keep in mind the argument's construction, the clarity of the language and content.

With regard to the argument’s construction, you should identify:

- Any places where the meaning is unclear or ambiguous

- Any factual errors

- Any invalid arguments

You may also wish to consider:

- Does the title properly reflect the subject of the paper?

- Does the abstract provide an accessible summary of the paper?

- Do the keywords accurately reflect the content?

- Is the paper an appropriate length?

- Are the key messages short, accurate and clear?

Not every submission is well written. Part of your role is to make sure that the text’s meaning is clear.

Editors say, " If a manuscript has many English language and editing issues, please do not try and fix it. If it is too bad, note that in your review and it should be up to the authors to have the manuscript edited ."

If the article is difficult to understand, you should have rejected it already. However, if the language is poor but you understand the core message, see if you can suggest improvements to fix the problem:

- Are there certain aspects that could be communicated better, such as parts of the discussion?

- Should the authors consider resubmitting to the same journal after language improvements?

- Would you consider looking at the paper again once these issues are dealt with?

On Grammar and Punctuation

Your primary role is judging the research content. Don't spend time polishing grammar or spelling. Editors will make sure that the text is at a high standard before publication. However, if you spot grammatical errors that affect clarity of meaning, then it's important to highlight these. Expect to suggest such amendments - it's rare for a manuscript to pass review with no corrections.

A 2010 study of nursing journals found that 79% of recommendations by reviewers were influenced by grammar and writing style (Shattel, et al., 2010).

1. The Introduction

A well-written introduction:

- Sets out the argument

- Summarizes recent research related to the topic

- Highlights gaps in current understanding or conflicts in current knowledge

- Establishes the originality of the research aims by demonstrating the need for investigations in the topic area

- Gives a clear idea of the target readership, why the research was carried out and the novelty and topicality of the manuscript

Originality and Topicality

Originality and topicality can only be established in the light of recent authoritative research. For example, it's impossible to argue that there is a conflict in current understanding by referencing articles that are 10 years old.

Authors may make the case that a topic hasn't been investigated in several years and that new research is required. This point is only valid if researchers can point to recent developments in data gathering techniques or to research in indirectly related fields that suggest the topic needs revisiting. Clearly, authors can only do this by referencing recent literature. Obviously, where older research is seminal or where aspects of the methodology rely upon it, then it is perfectly appropriate for authors to cite some older papers.

Editors say, "Is the report providing new information; is it novel or just confirmatory of well-known outcomes ?"

It's common for the introduction to end by stating the research aims. By this point you should already have a good impression of them - if the explicit aims come as a surprise, then the introduction needs improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

Academic research should be replicable, repeatable and robust - and follow best practice.

Replicable Research

This makes sufficient use of:

- Control experiments

- Repeated analyses

- Repeated experiments

These are used to make sure observed trends are not due to chance and that the same experiment could be repeated by other researchers - and result in the same outcome. Statistical analyses will not be sound if methods are not replicable. Where research is not replicable, the paper should be recommended for rejection.

Repeatable Methods

These give enough detail so that other researchers are able to carry out the same research. For example, equipment used or sampling methods should all be described in detail so that others could follow the same steps. Where methods are not detailed enough, it's usual to ask for the methods section to be revised.

Robust Research

This has enough data points to make sure the data are reliable. If there are insufficient data, it might be appropriate to recommend revision. You should also consider whether there is any in-built bias not nullified by the control experiments.

Best Practice

During these checks you should keep in mind best practice:

- Standard guidelines were followed (e.g. the CONSORT Statement for reporting randomized trials)

- The health and safety of all participants in the study was not compromised

- Ethical standards were maintained

If the research fails to reach relevant best practice standards, it's usual to recommend rejection. What's more, you don't then need to read any further.

3. Results and Discussion

This section should tell a coherent story - What happened? What was discovered or confirmed?

Certain patterns of good reporting need to be followed by the author:

- They should start by describing in simple terms what the data show

- They should make reference to statistical analyses, such as significance or goodness of fit

- Once described, they should evaluate the trends observed and explain the significance of the results to wider understanding. This can only be done by referencing published research

- The outcome should be a critical analysis of the data collected

Discussion should always, at some point, gather all the information together into a single whole. Authors should describe and discuss the overall story formed. If there are gaps or inconsistencies in the story, they should address these and suggest ways future research might confirm the findings or take the research forward.

4. Conclusions

This section is usually no more than a few paragraphs and may be presented as part of the results and discussion, or in a separate section. The conclusions should reflect upon the aims - whether they were achieved or not - and, just like the aims, should not be surprising. If the conclusions are not evidence-based, it's appropriate to ask for them to be re-written.

5. Information Gathered: Images, Graphs and Data Tables

If you find yourself looking at a piece of information from which you cannot discern a story, then you should ask for improvements in presentation. This could be an issue with titles, labels, statistical notation or image quality.

Where information is clear, you should check that:

- The results seem plausible, in case there is an error in data gathering

- The trends you can see support the paper's discussion and conclusions

- There are sufficient data. For example, in studies carried out over time are there sufficient data points to support the trends described by the author?

You should also check whether images have been edited or manipulated to emphasize the story they tell. This may be appropriate but only if authors report on how the image has been edited (e.g. by highlighting certain parts of an image). Where you feel that an image has been edited or manipulated without explanation, you should highlight this in a confidential comment to the editor in your report.

6. List of References

You will need to check referencing for accuracy, adequacy and balance.

Where a cited article is central to the author's argument, you should check the accuracy and format of the reference - and bear in mind different subject areas may use citations differently. Otherwise, it's the editor’s role to exhaustively check the reference section for accuracy and format.

You should consider if the referencing is adequate:

- Are important parts of the argument poorly supported?

- Are there published studies that show similar or dissimilar trends that should be discussed?

- If a manuscript only uses half the citations typical in its field, this may be an indicator that referencing should be improved - but don't be guided solely by quantity

- References should be relevant, recent and readily retrievable

Check for a well-balanced list of references that is:

- Helpful to the reader

- Fair to competing authors

- Not over-reliant on self-citation

- Gives due recognition to the initial discoveries and related work that led to the work under assessment

You should be able to evaluate whether the article meets the criteria for balanced referencing without looking up every reference.

7. Plagiarism

By now you will have a deep understanding of the paper's content - and you may have some concerns about plagiarism.

Identified Concern

If you find - or already knew of - a very similar paper, this may be because the author overlooked it in their own literature search. Or it may be because it is very recent or published in a journal slightly outside their usual field.

You may feel you can advise the author how to emphasize the novel aspects of their own study, so as to better differentiate it from similar research. If so, you may ask the author to discuss their aims and results, or modify their conclusions, in light of the similar article. Of course, the research similarities may be so great that they render the work unoriginal and you have no choice but to recommend rejection.

"It's very helpful when a reviewer can point out recent similar publications on the same topic by other groups, or that the authors have already published some data elsewhere ." (Editor feedback)

Suspected Concern

If you suspect plagiarism, including self-plagiarism, but cannot recall or locate exactly what is being plagiarized, notify the editor of your suspicion and ask for guidance.

Most editors have access to software that can check for plagiarism.

Editors are not out to police every paper, but when plagiarism is discovered during peer review it can be properly addressed ahead of publication. If plagiarism is discovered only after publication, the consequences are worse for both authors and readers, because a retraction may be necessary.

For detailed guidelines see COPE's Ethical guidelines for reviewers and Wiley's Best Practice Guidelines on Publishing Ethics .

8. Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

After the detailed read-through, you will be in a position to advise whether the title, abstract and key words are optimized for search purposes. In order to be effective, good SEO terms will reflect the aims of the research.

A clear title and abstract will improve the paper's search engine rankings and will influence whether the user finds and then decides to navigate to the main article. The title should contain the relevant SEO terms early on. This has a major effect on the impact of a paper, since it helps it appear in search results. A poor abstract can then lose the reader's interest and undo the benefit of an effective title - whilst the paper's abstract may appear in search results, the potential reader may go no further.

So ask yourself, while the abstract may have seemed adequate during earlier checks, does it:

- Do justice to the manuscript in this context?

- Highlight important findings sufficiently?

- Present the most interesting data?

Editors say, " Does the Abstract highlight the important findings of the study ?"

If there is a formal report format, remember to follow it. This will often comprise a range of questions followed by comment sections. Try to answer all the questions. They are there because the editor felt that they are important. If you're following an informal report format you could structure your report in three sections: summary, major issues, minor issues.

- Give positive feedback first. Authors are more likely to read your review if you do so. But don't overdo it if you will be recommending rejection

- Briefly summarize what the paper is about and what the findings are

- Try to put the findings of the paper into the context of the existing literature and current knowledge

- Indicate the significance of the work and if it is novel or mainly confirmatory

- Indicate the work's strengths, its quality and completeness

- State any major flaws or weaknesses and note any special considerations. For example, if previously held theories are being overlooked

Major Issues

- Are there any major flaws? State what they are and what the severity of their impact is on the paper

- Has similar work already been published without the authors acknowledging this?

- Are the authors presenting findings that challenge current thinking? Is the evidence they present strong enough to prove their case? Have they cited all the relevant work that would contradict their thinking and addressed it appropriately?

- If major revisions are required, try to indicate clearly what they are

- Are there any major presentational problems? Are figures & tables, language and manuscript structure all clear enough for you to accurately assess the work?

- Are there any ethical issues? If you are unsure it may be better to disclose these in the confidential comments section

Minor Issues

- Are there places where meaning is ambiguous? How can this be corrected?

- Are the correct references cited? If not, which should be cited instead/also? Are citations excessive, limited, or biased?

- Are there any factual, numerical or unit errors? If so, what are they?

- Are all tables and figures appropriate, sufficient, and correctly labelled? If not, say which are not

Your review should ultimately help the author improve their article. So be polite, honest and clear. You should also try to be objective and constructive, not subjective and destructive.

You should also:

- Write clearly and so you can be understood by people whose first language is not English

- Avoid complex or unusual words, especially ones that would even confuse native speakers

- Number your points and refer to page and line numbers in the manuscript when making specific comments

- If you have been asked to only comment on specific parts or aspects of the manuscript, you should indicate clearly which these are

- Treat the author's work the way you would like your own to be treated

Most journals give reviewers the option to provide some confidential comments to editors. Often this is where editors will want reviewers to state their recommendation - see the next section - but otherwise this area is best reserved for communicating malpractice such as suspected plagiarism, fraud, unattributed work, unethical procedures, duplicate publication, bias or other conflicts of interest.

However, this doesn't give reviewers permission to 'backstab' the author. Authors can't see this feedback and are unable to give their side of the story unless the editor asks them to. So in the spirit of fairness, write comments to editors as though authors might read them too.

Reviewers should check the preferences of individual journals as to where they want review decisions to be stated. In particular, bear in mind that some journals will not want the recommendation included in any comments to authors, as this can cause editors difficulty later - see Section 11 for more advice about working with editors.

You will normally be asked to indicate your recommendation (e.g. accept, reject, revise and resubmit, etc.) from a fixed-choice list and then to enter your comments into a separate text box.

Recommending Acceptance

If you're recommending acceptance, give details outlining why, and if there are any areas that could be improved. Don't just give a short, cursory remark such as 'great, accept'. See Improving the Manuscript

Recommending Revision

Where improvements are needed, a recommendation for major or minor revision is typical. You may also choose to state whether you opt in or out of the post-revision review too. If recommending revision, state specific changes you feel need to be made. The author can then reply to each point in turn.

Some journals offer the option to recommend rejection with the possibility of resubmission – this is most relevant where substantial, major revision is necessary.

What can reviewers do to help? " Be clear in their comments to the author (or editor) which points are absolutely critical if the paper is given an opportunity for revisio n." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Recommending Rejection

If recommending rejection or major revision, state this clearly in your review (and see the next section, 'When recommending rejection').