An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Biochem Res Int

- v.2022; 2022

Essential Guide to Manuscript Writing for Academic Dummies: An Editor's Perspective

Syed sameer aga.

1 Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Quality Assurance Unit, College of Medicine, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS), King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs (MNGHA), King Abdulaziz Medical City, Jeddah 21423, Saudi Arabia

2 Molecular Diseases & Diagnostics Division, Infinity Biochemistry Pvt. Ltd, Sajad Abad, Chattabal, Srinagar, Kashmir 190010, India

Saniya Nissar

Associated data.

No data were used in this review.

Writing an effective manuscript is one of the pivotal steps in the successful closure of the research project, and getting it published in a peer-reviewed and indexed journal adds to the academic profile of a researcher. Writing and publishing a scientific paper is a tough task that researchers and academicians must endure in staying relevant in the field. Success in translating the benchworks into the scientific content, which is effectively communicated within the scientific field, is used in evaluating the researcher in the current academic world. Writing is a highly time-consuming and skill-oriented process that requires familiarity with the numerous publishing steps, formatting rules, and ethical guidelines currently in vogue in the publishing industry. In this review, we have attempted to include the essential information that novice authors in their early careers need to possess, to be able to write a decent first scientific manuscript ready for submission in the journal of choice. This review is unique in providing essential guidance in a simple point-wise manner in conjunction with easy-to-understand illustrations to familiarize novice researchers with the anatomy of a basic scientific manuscript.

1. Background

Communication is the pivotal key to the growth of scientific literature. Successfully written scientific communication in the form of any type of paper is needed by researchers and academicians alike for various reasons such as receiving degrees, getting a promotion, becoming experts in the field, and having editorships [ 1 , 2 ].

Here, in this review, we present the organization and anatomy of a scientific manuscript enlisting the essential features that authors should keep in their mind while writing a manuscript.

2. Types of Manuscripts

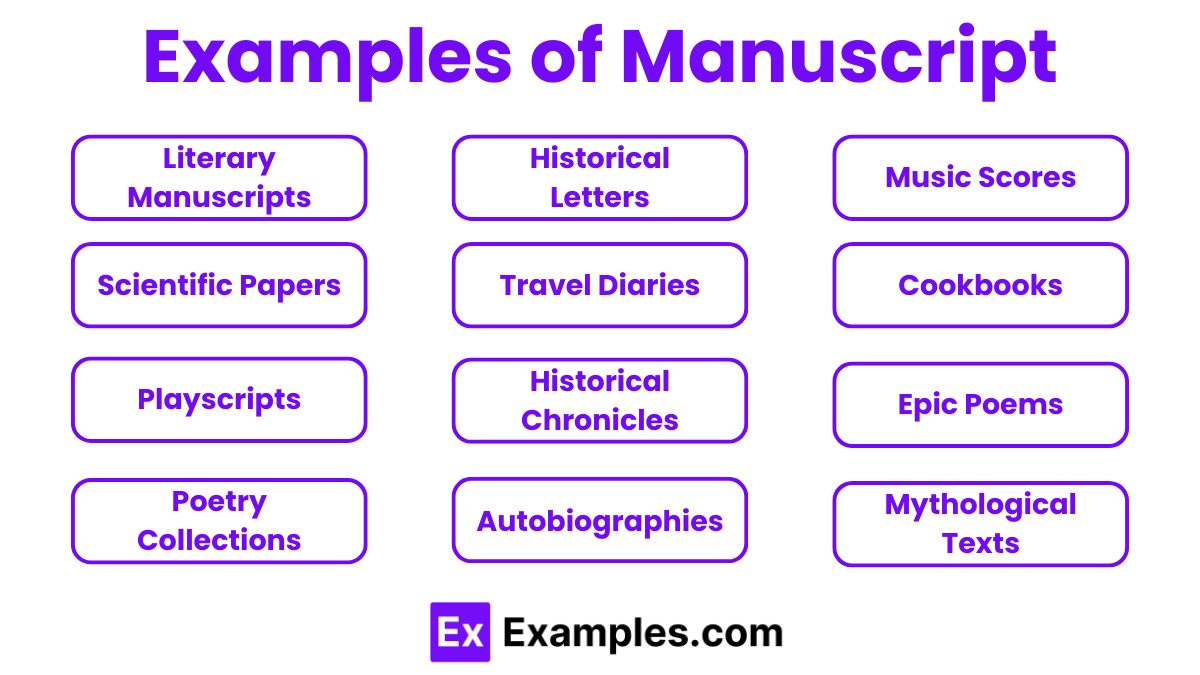

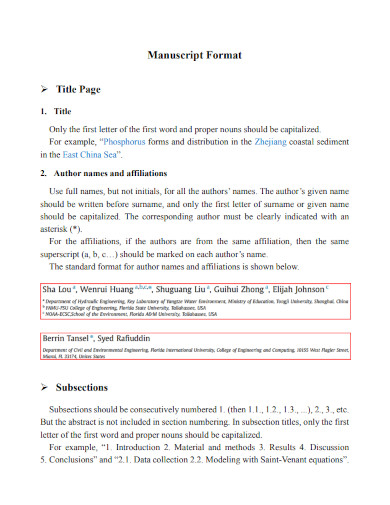

Numerous types of manuscripts do exist, which can be written by the authors for a possible publication ( Figure 1 ). Primarily, the choice is dependent upon the sort of communication authors want to make. The simplest among the scientific manuscripts is the “Letter to an Editor,” while “Systematic Review” is complex in its content and context [ 3 ].

Types of manuscripts based on complexity of content and context.

3. Anatomy of the Manuscript

Writing and publishing an effective and well-communicative scientific manuscript is arguably one of the most daunting yet important tasks of any successful research project. It is only through publishing the data that an author gets the recognition of the work, gets established as an expert, and becomes citable in the scientific field [ 4 ]. Among the numerous types of scientific manuscripts which an author can write ( Figure 1 ), original research remains central to most publications [ 4 – 10 ].

A good scientific paper essentially covers the important criteria, which define its worth such as structure, logical flow of information, content, context, and conclusion [ 5 ]. Among various guidelines that are available for the authors to follow, IMRAD scheme is the most important in determining the correct flow of content and structure of an original research paper [ 4 , 11 – 13 ]. IMRAD stands for introduction, methods, results, and discussion ( Figure 2 ). Besides these, other parts of the manuscript are equally essential such as title, abstract, keywords, and conclusion ( Figure 3 ).

Generalized anatomy of manuscript based on IMRAD format.

Three important contents of the title page—title, abstract, and keywords.

IMRAD scheme was introduced in the early 1900 by publishers to standardize the single format of the scientific manuscript and since then is the universal format used by most the publishing houses [ 6 , 14 – 17 ]. In the next sections, the contents and criteria of each of them are explained in detail. A list of the most common mistakes, which the author makes in these sections, is also provided in the tabulated form [ 18 ] ( Table 1 ).

Common mistakes authors make in their manuscripts.

- The title is the most important element of the paper, the first thing readers encounter while searching for a suitable paper [ 1 ]. It reflects the manuscript's main contribution and hence should be simple, appealing, and easy to remember [ 7 ].

- A good title should not be more than 15 words or 100 characters. Sometimes journals ask for a short running title, which should essentially be no more than 50% of the full title. Running titles need to be simple, catchy, and easy to remember [ 19 , 20 ].

- Keeping the titles extremely long can be cumbersome and is suggestive of the authors' lack of grasp of the true nature of the research done.

- It usually should be based on the keywords, which feature within the main rationale and/or objectives of the paper. The authors should construct an effective title from keywords existing in all sections of the main text of the manuscript [ 19 ].

- Having effective keywords within the title helps in the easy discovery of the paper in the search engines, databases, and indexing services, which ultimately is also reflected by the higher citations they attract [ 1 ].

- It is always better for the title to reflect the study's design or outcome [ 21 ]; thus, it is better for the authors to think of a number of different titles proactively and to choose the one, which reflects the manuscript in all domains, after careful deliberation. The paper's title should be among the last things to be decided before the submission of the paper for publication [ 20 ].

- Use of abbreviations, jargons, and redundancies such as “a study in,” “case report of,” “Investigations of,” and passive voice should be avoided in the title.

5. Abstract

- The abstract should essentially be written to answer the three main questions—“What is new in this study?” “What does it add to the current literature?” and “What are the future perspectives?”

- A well-written abstract is a pivotal part of every manuscript. For most readers, an abstract is the only part of the paper that is widely read, so it should be aimed to convey the entire message of the paper effectively [ 1 ].

Two major types of abstract—structured and unstructured. Structured abstracts are piecemealed into five different things, each consisting of one or two sentences, while unstructured abstracts consist of single paragraph written about the same things.

- An effective abstract is a rationalized summary of the whole study and essentially should contain well-balanced information about six things: background, aim, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion [ 6 , 19 ].

Three C concept followed while writing the manuscript.

- An abstract should be written at the end, after finishing the writing of an entire manuscript to be able to stand-alone from the main text. It should reflect your study completely without any reference to the main paper [ 19 ].

- The authors need to limit/write their statements in each section to two or three sentences. However, it is better to focus on results and conclusions, as they are the main parts that interest the readers and should include key results and conclusions made thereof.

- Inclusion of excessive background information, citations, abbreviations, use of acronyms, lack of rationale/aim of the study, lack of meaningful data, and overstated conclusions make an abstract ineffective.

6. Keywords

- Keywords are the important words, which feature repeatedly in the study or else cover the main theme/idea/subject of the manuscript. They are used by indexing databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Embase in categorizing and cross-indexing the published article.

- It is always wise to enlist those words which help the paper to be easily searchable in the databases.

- Keywords can be of two types: (a) general ones that are provided by the journal or indexing services called as medical subject headings (MeSH) as available in NCBI ( https://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/mesh/ ) and (b) custom ones made by authors themselves based on the subject matter of the study [ 6 , 20 ].

- Upon submission, journals do usually ask for the provision of five to ten keywords either to categorize the paper into the subject areas or to assign it to the subspecialty for its quick processing.

7. Introduction

- (i) The whole idea of writing this section is to cover two important questions—“What are the gaps present in the current literature?” and “Why is the current study important?”

- (ii) Introduction provides an opportunity for the authors to highlight their area of study and provide rationale and justification as to why they are doing it [ 20 , 22 , 23 ].

- (iii) An effective introduction usually constitutes about 10–15% of the paper's word count [ 22 ].

- The first paragraph of the introduction should always cover “What is known about the area of study?” or “What present/current literature is telling about the problem?” All relevant and current literature/studies, i.e., original studies, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews, should be covered in this paragraph.

- The second paragraph should cover “What is unknown or not done about this issue/study area?” The authors need to indicate the aspects of what has not been answered about the broader area of the study until now.

- The third paragraph should identify the gaps in the current literature and answer “What gaps in the literature would be filled by their current study?” This part essentially identifies the shortcoming of the existing studies.

- The fourth paragraph should be dedicated to effectively writing “What authors are going to do to fill the gaps?” and “Why do they want to do it?” This paragraph contains two sections—one explains the rationale of the study and introduces the hypothesis of the study in form of questions “What did authors do? and Why they did do so?” and the second enlists specific objectives that the authors are going to explore in this study to answer “Why this study is going to be important?” or “What is the purpose of this study?”.

Funnel-down scheme followed while writing the introduction section of manuscript, moving from broader to specific information.

- (v) Introduction is regarded as the start of the storyline of manuscript, and hence, the three Cs' scheme ( Figure 5 ) becomes more relevant while writing it: the context in terms of what has been published on the current idea/problem around the world, content as to what you are going to do about the problem in hand (rationale), and conclusion as to how it is going to be done (specific objective of the study) [ 1 , 23 ].

- (vi) Introduction is the first section of the main manuscript, which talks about the story; therefore, while writing it authors should always try to think that “would this introduction be able to convince my readers?” [ 25 ]. To emphasize on the importance of the study in filling the knowledge gap is pivotal in driving the message through [ 23 ].

- (vii) Introduction should never be written like a review, any details, contexts, and comparisons should be dealt within the discussion part [ 16 ].

- (viii) While choosing the papers, it is wise to include the essential and recent studies only. Studies more than 10 years old should be avoided, as editors are inclined towards the recent and relevant ones only [ 20 , 22 ].

- (ix) In the last paragraph, enlisting the objectives has a good impact on readers. A clear distinction between the primary and secondary objectives of the study should be made while closing the introduction [ 22 ].

- (i) It is regarded as the skeleton of the manuscript as it contains information about the research done. An effective methods section should provide information about two essential aspects of the research—(a) precise description of how experiments were done and (b) rationale for choosing the specific experiments.

- Study Settings: describing the area or setting where the study was conducted. This description should cover the details relevant to the study topic.

Different guidelines available for perusal of the authors for writing an effective manuscript.

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique: mentioning what number of samples is needed and how they would be collected.

- Ethical Approvals: clearly identifying the study approval body or board and proper collection of informed consent from participants.

- Recruitment Methods: using at least three criteria for the inclusion or exclusion of the study subjects to reach an agreed sample size.

- Experimental and Intervention Details: exhaustively describing each and every detail of all the experiments and intervention carried out in the study for the readers to reproduce independently.

- Statistical Analysis: mentioning all statistical analysis carried out with the data which include all descriptive and inferential statistics and providing the analysis in meaningful statistical values such as mean, median, percent, standard deviation (SD), probability value (p), odds ratio (OR), and confidence interval (CI).

Methods and the seven areas which it should exhaustively describe.

- (iii) Methods should be elaborative enough that the readers are able to replicate the study on their own. If, however, the protocols are frequently used ones and are already available in the literature, the authors can cite them without providing any exhaustive details [ 26 ].

- (iv) Methods should be able to answer the three questions for which audience reads the paper—(1) What was done? (2) Where it was done? and (3) How it was done? [ 11 ].

- (v) Remember, methods section is all about “HOW” the data were collected contrary to “WHAT” data were collected, which should be written in the results section. Therefore, care should be taken in providing the description of the tools and techniques used for this purpose.

- (vi) Writing of the methods section should essentially follow the guidelines as per the study design right from the ideation of the project. There are numerous guidelines available, which author's must make use of, to streamline the writing of the methods section in particular (see Table xx for details).

- (vii) Provision of the information of the equipment, chemicals, reagents, and physical conditions is also vital for the readers for replication of the study. If any software is used for data analysis, it is imperative to mention it. All manufacturer's names, their city, and country should also be provided [ 6 , 11 ].

- The purpose of the results section of the manuscript is to present the finding of the study in clear, concise, and objective manner to the readers [ 7 , 27 , 28 ].

- Results section makes the heart of the manuscript, as all sections revolve around it. The reported findings should be in concordance with the objectives of the study and be able to answer the questions raised in the introduction [ 6 , 20 , 27 ].

- Results should be written in past tense without any interpretation [ 6 , 27 ].

Interdependence between methods and results of the manuscript.

- It is always better to take refuge in tables and figures to drive the exhaustive data through. Repetition of the data already carried in tables, figures, etc., should be avoided [ 4 , 6 , 20 ].

- Proper positioning and citations of the tables and figures within the main text are also critical for the flow of information and quality of the manuscript [ 6 , 11 ].

- Results section should carry clear descriptive and inferential statistics in tables and/or figures, for ease of reference to readers.

- Provision of the demographic data of the study participants takes priority in the results section; therefore, it should be made as its first paragraph. The subsequent paragraphs should introduce the inferential analysis of the data based on the rationale and objectives of the study. The last paragraphs mention what new results the study is going to offer [ 6 , 11 , 20 ].

- authors should not attempt to report all analysis of the data. Discussing, interpreting, or contextualizing the results should be avoided [ 20 ].

10. Discussion

- (i) The main purpose of writing a discussion is to fill the gap that was identified in the introduction of the manuscript and provide true interpretations of the results [ 6 , 11 , 20 ].

Pyramid scheme followed while writing the discussion section of manuscript, moving from the key results of the study to the specific conclusions.

- (iii) Discussion section toggles between two things—content and context. The authors need to exhaustively describe their interpretation of the analyzed data (content) and then compare it with the available relevant literature (context) [ 1 , 29 ]. Finally, it should justify everything in conclusion as to what all this means for the field of study.

- (iv) The comparison can either be concordant or discordant, but it needs to highlight the uniqueness and importance of the study in the field. Care should be taken not to cover up any deviant results, which do not gel with the current literature [ 30 ].

- (v) In discussion it is safe to use words such as “may,” “might,” “show,” “demonstrate,” “suggest,” and “report” while impressing upon your study's data and analyzed results.

- (vi) Putting results in context helps in identifying the strengths and weakness of the study and enables readers to get answers to two important questions—one “what are the implications of the study?” Second “how the study advance the field further?” [ 1 , 30 ].

- The first paragraph of the discussion is reserved for highlighting the key results of the study as briefly as possible [ 4 , 6 ]. However, care should be taken not to have any redundancy with the results section. The authors should utilize this part to emphasize the originality and significance of their results in the field [ 1 , 4 , 11 , 20 ].

- The second paragraph should deal with the importance of your study in relationship with other studies available in the literature [ 4 ].

- Subsequent paragraphs should focus on the context, by describing the findings in comparison with other similar studies in the field and how the gap in the knowledge has been filled [ 1 , 4 ].

- In the penultimate paragraph, authors need to highlight the strengths and limitations of the study [ 4 , 6 , 30 ].

- Final paragraph of the discussion is usually reserved for drawing the generalized conclusions for the readers to get a single take-home message.

- (viii) A well-balanced discussion is the one that effectively addresses the contribution made by this study towards the advancement of knowledge in general and the field of research in particular [ 7 ]. It essentially should carry enough information that the audience knows how to apply the new interpretation presented within that field.

11. Conclusion

- It usually makes the last part of the manuscript, if not already covered within the discussion part [ 6 , 20 ].

- Being the last part of the main text, it has a long-lasting impact on the reader and hence should be very clear in presenting the chief findings of the paper as per the rationale and objectives of the study [ 4 , 20 ].

Crux of the conclusion section.

12. References or Bibliography

- Every article needs a suitable and relevant citation of the available literature to carry the contextual message of their results to the readers [ 31 ].

- Inclusion of proper references in the required format, as asked by the target journal, is necessary.

A Google Scholar screenshot of different styles of formatting of references.

- Depending upon the journal and publishing house, usually, 30–50 citations are allowed in an original study, and they need to be relevant and recent.

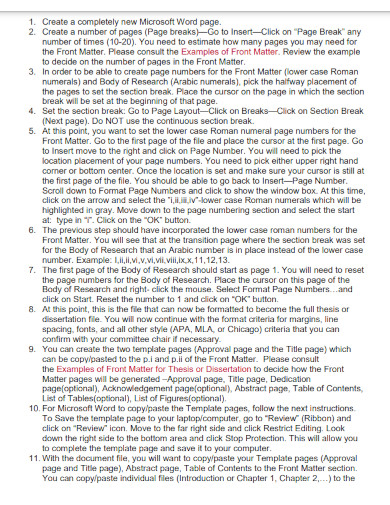

13. Organization of the Manuscript Package

Ideally, all manuscripts, no matter where they have to be submitted, should follow an approved organization, which is universally used by all publication houses. “Ready to submit” manuscript package should include the following elements:

- (i) Cover letter, addressed to the chief editor of the target journal.

- (ii) Authorship file, containing the list of authors, their affiliations, emails, and ORCIDs.

- (iii) Title page, containing three things—title, abstract, and keywords.

- Main text structured upon IMRAD scheme.

- References as per required format.

- Legends to all tables and figures.

- Miscellaneous things such as author contributions, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest, funding body, and ethical approvals.

- (v) Tables as a separate file in excel format.

- (vi) Figures or illustrations, each as a separate file in JPEG or TIFF format [ 32 ].

- (vii) Reviewers file, containing names of the suggested peer reviewers working or publishing in the same field.

- (viii) Supplementary files, which can be raw data files, ethical clearance from Institutional Review Board (IRBs), appendixes, etc.

14. Overview of an Editorial Process

Each scientific journal has a specific publication policies and procedures, which govern the numerous steps of the publication process. In general, all publication houses process the submission of manuscripts via multiple steps tightly controlled by the editors and reviewers [ 33 ]. Figure 12 provides general overview of the six-step editorial process of the scientific journal.

An overview of the journal's editorial process.

15. Summary

The basic criteria for writing any scientific communication are to know how to communicate the information effectively. In this review, we have provided the critical information of do's and don'ts for the naive authors to follow in making their manuscript enough impeccable and error-free that on submission manuscript is not desk rejected at all. but this goes with mentioning that like any other skill, and the writing is also honed by practicing and is always reflective of the knowledge the writer possesses. Additionally, an effective manuscript is always based on the study design and the statistical analysis done. The authors should always bear in mind that editors apart from looking into the novelty of the study also look at how much pain authors have taken in writing, following guidelines, and formatting the manuscript. Therefore, the organization of the manuscript as per provided guidelines such as IMRAD, CONSORT, and PRISMA should be followed in letter and spirit. Care should be taken to avoid the mistakes, already enlisted, which can be the cause of desk rejection. As a general rule, before submission of the manuscript to the journal, sanitation check involving at least two reviews by colleagues should be carried out to ensure all general formatting guidelines are followed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all academicians and researchers who have actively participated in the “Writing Manuscript Workshops” at the College of Medicine, KSAU-HS, Jeddah, which prompted them to write this review.

Data Availability

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Both authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript. SSA conceptualized the study, designed the study, surveyed the existing literature, and wrote the manuscript. SN edited, revised, and proofread the final manuscript.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 28 February 2018

- Correction 16 March 2018

How to write a first-class paper

- Virginia Gewin 0

Virginia Gewin is a freelance writer in Portland, Oregon.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Manuscripts may have a rigidly defined structure, but there’s still room to tell a compelling story — one that clearly communicates the science and is a pleasure to read. Scientist-authors and editors debate the importance and meaning of creativity and offer tips on how to write a top paper.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 555 , 129-130 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02404-4

Interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 16 March 2018 : This article should have made clear that Altmetric is part of Digital Science, a company owned by Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, which is also the majority shareholder in Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature. Nature Research Editing Services is also owned by Springer Nature.

Related Articles

How researchers in remote regions handle the isolation

Career Feature 24 MAY 24

What steps to take when funding starts to run out

Brazil’s plummeting graduate enrolments hint at declining interest in academic science careers

Career News 21 MAY 24

Who will make AlphaFold3 open source? Scientists race to crack AI model

News 23 MAY 24

Egypt is building a $1-billion mega-museum. Will it bring Egyptology home?

News Feature 22 MAY 24

Pay researchers to spot errors in published papers

World View 21 MAY 24

Professor, Division Director, Translational and Clinical Pharmacology

Cincinnati Children’s seeks a director of the Division of Translational and Clinical Pharmacology.

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati Children's Hospital & Medical Center

Data Analyst for Gene Regulation as an Academic Functional Specialist

The Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn is an international research university with a broad spectrum of subjects. With 200 years of his...

53113, Bonn (DE)

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität

Recruitment of Global Talent at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

The Institute of Zoology (IOZ), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), is seeking global talents around the world.

Beijing, China

Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

Full Professorship (W3) in “Organic Environmental Geochemistry (f/m/d)

The Institute of Earth Sciences within the Faculty of Chemistry and Earth Sciences at Heidelberg University invites applications for a FULL PROFE...

Heidelberg, Brandenburg (DE)

Universität Heidelberg

Postdoc: deep learning for super-resolution microscopy

The Ries lab is looking for a PostDoc with background in machine learning.

Vienna, Austria

University of Vienna

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- About This Blog

- Official PLOS Blog

- EveryONE Blog

- Speaking of Medicine

- PLOS Biologue

- Absolutely Maybe

- DNA Science

- PLOS ECR Community

- All Models Are Wrong

- About PLOS Blogs

A Brief Guide To Writing Your First Scientific Manuscript

I’ve had the privilege of writing a few manuscripts in my research career to date, and helping trainees write them. It’s hard work, but planning and organization helps. Here’s some thoughts on how to approach writing manuscripts based on original biomedical research.

Getting ready to write

Involve your principal investigator (PI) early and throughout the process. It’s our job to help you write!

Write down your hypothesis/research question. Everything else will be spun around this.

Gather your proposed figures and tables in a sequence that tells a story. This will form the basis of your Results section. Write bulleted captions for the figures/tables, including a title that explains the key finding for each figure/table, an explanation of experimental groups and associated symbols/labels, and details on biological and technical replicates and statements (such as “one of four representative experiments are shown.”)

Generate a bulleted outline of the major points for each section of the manuscript. This depends on the journal, but typically, and with minor variations: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion. Use Endnote, Reference Manager, Mendeley, or other citation software to start inserting references to go with bullets. Decide from the beginning what word processing software you’ll use (Word, Google Docs, etc.). Google Docs can be helpful for maintaining a single version of the manuscript, but citation software often doesn’t play well with Google Docs (whereas most software options can automatically update citation changes in Word). Here’s what should go in each of these sections:

Introduction: What did you study, and why is it important? What is your hypothesis/research question?

Methods: What techniques did you use? Each technique should be its own bullet, with sub-bullets for key details. If you used animal or human subjects, include a bullet on ethics approval. Important methodologies and materials, i.e., blinding for subjective analyses, full names of cell lines/strains/reagents and your commercial/academic sources for them.

Results: What were your findings? Each major finding should be its own bullet, with sub-bullets going into more detail for each major finding. These bullets should refer to your figures.

Discussion: Summarize your findings in the context of prior work. Discuss possible interpretations. It is important to include a bullet describing the limitations of the presented work. Mention possible future directions.

Now read the entire outline (including the figures). Is it a complete story? If so, you’re ready to prepare for submission. If not, you should have a good idea of what it will take to finish the manuscript.

Writing your manuscript

You first need to decide where you want to submit your manuscript. I like to consider my ideal target audience. I also like to vary which journals I publish in, both to broaden the potential readers of my papers and to avoid the appearance of having an unfair “inside connection” to a given journal. Your academic reputation is priceless.

Once you’ve chosen your journal, look at the journal’s article types. Decide which article type you would like to submit and reformat your outline according to the journal’s standards (including citation style).

Convert your outline (including the figure captions) to complete sentences. Don’t focus on writing perfect prose for the first draft. Write your abstract after the first draft is completed. Make sure the manuscript conforms to the target journal’s word and figure limits.

Discuss all possible authors with your PI. If the study involved many people, create a table of possible authors showing their specific contributions to the manuscript. (This is helpful to do in any case as many journals now require this information.) Assigning authorship is sometimes complicated, but keep in mind that the Acknowledgements can be used to recognize those who made minor contributions (including reading the manuscript to provide feedback). “Equal contribution” authorship positions for the first and last authors is a newer option for a number of journals. An alternative is to generate the initial outline or first draft with the help of co-authors. This can take a lot more work and coordination, but may make sense for highly collaborative and large manuscripts.

Decide with your PI who will be corresponding author. Usually you or the PI.

Circulate the manuscript draft to all possible authors. Thank them for their prior and ongoing support. Inform your co-authors where you would like to send the manuscript and why. Give them a reasonable deadline to provide feedback (minimum of a few weeks). If you use Microsoft Word, ask your co-authors to use track changes.

Collate comments from your co-authors. The Combine Documents function in Word can be very helpful. Consider reconciling all comments and tracked changes before circulating another manuscript draft so that co-authors can read a “clean” copy. Repeat this process until you and your PI (and co-authors) are satisfied that the manuscript is ready for submission.

Some prefer to avoid listing authors on manuscript drafts until the final version is generated because the relative contributions of authors can shift during manuscript preparation.

Submit your manuscript

Write a cover letter for your manuscript. Put it on institutional letterhead, if you are permitted by the journal’s submission system. This makes the cover letter, and by extension, the manuscript, more professional. Some journals have required language for cover letters regarding simultaneous submissions to other journals. It’s common for journals to require that cover letters include a rationale explaining the impact and findings of the manuscript. If you need to do this, include key references and a citation list at the end of the cover letter.

Most journals will require you to provide keywords, and/or to choose subject areas related to the manuscript. Be prepared to do so.

Conflicts of interest should be declared in the manuscript, even if the journal does not explicitly request this. Ask your co-authors about any such potential conflicts.

Gather names and official designations of any grants that supported the work described in your manuscript. Ask your co-authors and your PI. This is very important for funding agencies such as the NIH, which scrutinize the productivity of their funded investigators and take this into account when reviewing future grants.

It’s common for journals to allow you to suggest an editor to handle your manuscript. Editors with expertise in your area are more likely to be able to identify and recruit reviewers who are also well-versed in the subject matter of your manuscript. Discuss this with your PI and co-authors.

Likewise, journals often allow authors to suggest reviewers. Some meta-literature indicates that manuscripts with suggested reviewers have an overall higher acceptance rate. It also behooves you to have expert reviewers that can evaluate your manuscript fairly, but also provide feedback that can improve your paper if revisions are recommended. Avoid suggesting reviewers at your own institution or who have recently written papers or been awarded grants with you. Savvy editors look for these types of relationships between reviewers and authors, and will nix a suggested reviewer with any potential conflict of interest. Discuss suggested reviewers with your PI and co-authors.

On the flip side, many journals will allow you to list opposed reviewers. If you believe that someone specific will provide a negatively biased review for non-scientific reasons, that is grounds for opposing them as your manuscript’s reviewer. In small fields, it may not be possible to exclude reviewers and still undergo expert peer review. Definitely a must-discuss with your PI and co-authors.

Generate a final version of the manuscript. Most journals use online submission systems that mandate uploading individual files for the manuscript, cover letter, etc. You may have to use pdf converting software (i.e., Adobe Acrobat) to change Word documents to pdf’s, or to combine documents into a single pdf. Review the final version, including the resolution and appearance of figures. Make sure that no edges of text or graphics near page margins are cut off (Adobe Acrobat sometimes does this with Microsoft Word). Send the final version to your PI and co-authors. Revise any errors. Then submit! Good luck!

Edited by Bill Sullivan, PhD, Indiana University School of Medicine.

Michael Hsieh is the Stirewalt Scientific Director of the Biomedical Research Institute and an Associate Professor at the George Washington University, where he studies host-pathogen interactions in the urinary tract. Michael has published over 90 peer-reviewed scientific papers. His work has been featured on PBS and in the New York Times.

Your article is wonderful. just read it. you advise very correctly. I am an experienced writer. I write articles on various scientific topics. and even I took some information for myself, who I have not used before. Your article will help many novice writers. I’m sure of it. You very well described all the points of your article. I completely agree with them. most difficult to determine the target audience. Thanks to your article, everyone who needs some kind of help can get it by reading your article. Thanks you

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name and email for the next time I comment.

Written by Jessica Rech an undergraduate student at IUPUI and coauthored by Brandi Gilbert, director of LHSI. I am an undergraduate student…

As more learning occurs online and at home with the global pandemic, keeping students engaged in learning about science is a challenge…

By Brad Parks A few years back, while driving to my favorite daily writing haunt, the local radio station spit out one…

A Guide on How to Write a Manuscript for a Research Paper

This article teaches how to write a manuscript for a research paper and recommended practices to produce a well-written manuscript.

For scientists, publishing a research paper is a huge accomplishment; they typically spend a large amount of time researching the appropriate subject, the right material, and, most importantly, the right place to publish their hard work. To be successful in publishing a research paper, it must be well-written and meet all of the high standards.

Although there is no quick and easy method to get published, there are certain manuscript writing strategies that can help earn the awareness and visibility you need to get it published.

In this Mind The Graph step-by-step tutorial, we give practical directions on how to write a manuscript for a research paper, to increase your research as well as your chances of publishing.

What is the manuscript of a research paper?

A manuscript is a written, typed, or word-processed document submitted to a publisher by the researcher. Researchers meticulously create manuscripts to communicate their unique ideas and fresh findings to both the scientific community and the general public.

Overall, the manuscript must be outstanding and deeply represent your professional attitude towards work; it must be complete, rationally structured, and accurate. To convey the results to the scientific community while complying with ethical rules, scientific articles must use a specified language and structure.

Furthermore, the standards for title page information, abstract structure, reference style, font size, line spacing, margins, layout, and paragraph style must also be observed for effective publishing. This is a time-consuming and challenging technique, but it is worthwhile in the end.

How to structure a manuscript?

The first step in knowing how to write a manuscript for a research paper is understanding how the structure works.

Title or heading

A poorly chosen title may deter a potential reader from reading deeper into your manuscript. When an audience comes across your manuscript, the first thing they notice is the title, keep in mind that the title you choose might impact the success of your work.

Abstracts are brief summaries of your paper. The fundamental concept of your research and the issues you intend to answer should be contained within the framework of the abstract. The abstract is a concise summary of the research that should be considered a condensed version of the entire article.

Introduction

The purpose of the research is disclosed in the body of the introduction. Background information is provided to explain why the study was conducted and the research’s development.

Methods and materials

The technical parts of the research have to be thoroughly detailed in this section. Transparency is required in this part of the research. Colleagues will learn about the methodology and materials you used to analyze your research, recreate it, and expand concepts further.

This is the most important portion of the paper. You should provide your findings and data once the results have been thoroughly discussed. Use an unbiased point of view here; but leave the evaluation for your final piece, the conclusion.

Finally, explain why your findings are meaningful. This section allows you to evaluate your results and reflect on your process. Remember that conclusions are expressed in a succinct way using words rather than figures. The content presented in this section should solely be based on the research conducted.

The reference list contains information that readers may use to find the sources you mentioned in your research. Your reference page is at the end of your piece. Keep in mind that each publication has different submission criteria. For effective reference authentication, journal requirements should be followed.

Steps on how to write a manuscript for a research paper

It is not only about the format while writing a successful manuscript, but also about the correct strategy to stand out above other researchers trying to be published. Consider the following steps to a well-written manuscript:

1. Read the author’s guide

Many journals offer a Guide for Authors kind of document, which is normally printed yearly and is available online. In this Guide for Authors, you will discover thorough information on the journal’s interests and scope, as well as information regarding manuscript types and more in-depth instructions on how to do the right formatting to submit your research.

2. Pay special attention to the methods and materials section

The section on methods and materials is the most important part of the research. It should explain precisely what you observed in the research. This section should normally be less than 1,000 words long. The methods and materials used should be detailed enough that a colleague could reproduce the study.

3. Identify and describe your findings

The second most crucial aspect of your manuscript is the findings. After you’ve stated what you observed (methods and materials), you should go through what you discovered. Make a note to organize your findings such that they make sense without further explanation.

4. The research’s face and body

In this part you need to produce the face and body of your manuscript, so do it carefully and thoroughly.

Ensure that the title page has all of the information required by the journal. The title page is the public face of your research and must be correctly structured to meet publication requirements.

Write an introduction that explains why you carried out the research and why anybody should be interested in the results (ask yourself “so what?”).

Concentrate on creating a clear and accurate reference page. As stated in step 1, you should read the author’s guide for the journal you intend to submit to thoroughly to ensure that your research reference page is correctly structured.

The abstract should be written just after the manuscript is finished. Follow the author’s guide and be sure to keep it under the word limit.

5. Rapid Rejection Criteria double-check

Now that you’ve completed the key aspects of your research, it’s time to double-check everything according to the Rapid Rejection Criteria. The “Rapid Rejection Criteria” are errors that lead to an instantaneous rejection. The criteria are:

- The answered question was not interesting enough

- The question has been satisfactorily answered before

- Wrong hypothesis

- The method cannot address the hypothesis

- Research is underpowered

- Contradictory manuscript

- The conclusion doesn’t support the data

Rewrite your manuscript now that you’ve finished it. Make yourself your fiercest critic. Consider reading the document loudly to yourself, keeping an ear out for any abrupt breaks in the logical flow or incorrect claims.

Your Creations, Ready within Minutes!

Aside from a step-by-step guide to writing a decent manuscript for your research, Mind The Graph includes a specialized tool for creating and providing templates for infographics that may maximize the potential and worth of your research. Check the website for more information.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Unlock Your Creativity

Create infographics, presentations and other scientifically-accurate designs without hassle — absolutely free for 7 days!

About Jessica Abbadia

Jessica Abbadia is a lawyer that has been working in Digital Marketing since 2020, improving organic performance for apps and websites in various regions through ASO and SEO. Currently developing scientific and intellectual knowledge for the community's benefit. Jessica is an animal rights activist who enjoys reading and drinking strong coffee.

Content tags

How to Write a Successful Scientific Manuscript

Writing a scientific manuscript is an endeavor that challenges the best minds, yet it is very rewarding once the body of work comes to fruition. Researchers carefully draft manuscripts allowing them to share their original ideas and new discoveries with the scientific community as well as to the general population. A significant amount of time and effort is spent during the investigative stages conducting the required research before it is released into the public domain. Therefore, the manuscript drafted to present this research must be thorough, logically presented, and factual. Scientific manuscripts must adhere to a specific language and format to communicate the results to the scientific community whilst adhering to ethical guidelines. When completed the final written product will allow colleagues to debate and reflect on the newly minted work embedded in the manuscript.

Organization

Scientific manuscripts are organized in a logical format, which fits specific criteria as determined by the scientific community. This methodology has been standardized in journals which communicate information to those in the field being discussed. Since the researcher has a storyline he or she is trying to transmit, it must be clear and upfront on the exact question and or problem that his research answers. Readers of the manuscript will be energized to review this work when its content is spelled out early in the paper. A well-written manuscript has the following components included: a clear title, abstract, introductory paragraph, methods and materials section, discussion of results, conclusion and a list of references. Each component of a journal article should follow a logical sequence, which members of the science community have become accustomed.

Related: Need some tips on manuscript drafting? Check out this section today!

Structural Contents

Title or heading.

Titles are extremely important. A crisp detailed title is the first element an audience notices when encountering your manuscript. The significance of a title cannot be overstated in that it introduces your reader to the subject matter you intend to discuss in the next thousand or more words. A poorly formatted title could dissuade a potential reader from delving into your manuscript further. In addition, your paper is indexed in a certain manner, which search engine algorithms will track. To rise to the top of the search index, keywords should be emphasized. Thinking of the right title could determine the size of your audience and the eventual success of your work.

Abstracts are abbreviated versions of your manuscript. Contained within the abstract’s structure should be the major premise of your research and the questions you seek to answer. Also included in the context of the abstract is a brief summary of the methods taken to achieve your goals along with a short version of the results. The abstract may be the only part of the paper read, therefore, it should be considered a concise version of your complete manuscript.

Introduction

The Introduction amplifies certain aspects of the abstract. Within the body of the introduction, the rationale for the research is revealed. Background material is supplied indicating why the research performed is important along with the direction the research took. A brief summary (in a few sentences) discussing the technical aspects of the experimental approach utilized to reach the article’s stated conclusions is included here. Written well the introduction will influence readers to delve further into the body of the paper.

Methodology and Materials

In this section, the technical aspects of the research are described extensively. Clarity in this part of the manuscript is mandatory. Fellow researchers will glean from this section the methods and materials you utilized either to validate your work, reproduce it, and/or develop the concepts further. Detailed protocols are presented here, similar to a road map, explaining the experiments performed, agents or technologies used, and any biology involved. Statistical analysis and tests should be presented here. Do not approximate anything in this part of the manuscript. Suspicion may be cast in your direction questioning the validity of the research if too many approximations are detected.

Discussion of Results

This part of the manuscript may be considered its core. Elaboration on data generated, utilizing tables and graphs, communicating the essence of the research and the outcomes they generate. Once the results are given a lengthy discussion, it should follow by including the interpretation of data, implications of these findings, and potential future research to follow. Ambiguous findings and current controversies in this type of research should be analyzed and examined in this section.

Conclusions

This is the endpoint in the manuscript. Conclusions are written in a concise manner utilizing words not numbers. Information conveyed in this section should only be taken from the research performed. Do not place your references here. Full and complete interpretation of your findings in this part of the manuscript is imperative. Clarity of thought is also essential because misinterpretation of the results is always a possibility. Comparisons to similar work in your field may be discussed here. Absolutely avoid interpretation of your results that cannot be justified by the work performed.

Every journal has submission requirements. Journal guidelines should be followed for proper authentication of references. There exist several formats for reference creation. Familiarize yourself with them. In addition, the sequence of references listed should be in the order in which they appear in the research paper . A number, usually in parenthesis, follows the sentence where they are noted.

Production of a scientific manuscript is a necessity to introduce your research to a wide audience. The complexity of the research and the results generated must be written in a manner that is clear and concise, follows the current journal formats, and is verifiable. The guidelines embedded in this paper will help the researcher place his work in the best light possible. Never write anything that cannot be justified by the research performed. With these simple rules in mind, your scientific manuscript will be a success.

Thanks for the succinct guidance on successful scientific manuscript

I found that your notes are quite joined up! But my query is what should be the scientific content of a discussion section? what if our data are the pioneer?

Thanks for it

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Improving Research Manuscripts Using AI-Powered Insights: Enago reports for effective research communication

Language Quality Importance in Academia AI in Evaluating Language Quality Enago Language Reports Live Demo…

- Reporting Research

Beyond Spellcheck: How copyediting guarantees error-free submission

Submitting a manuscript is a complex and often an emotional experience for researchers. Whether it’s…

How to Find the Right Journal and Fix Your Manuscript Before Submission

Selection of right journal Meets journal standards Plagiarism free manuscripts Rated from reviewer's POV

- Manuscripts & Grants

Research Aims and Objectives: The dynamic duo for successful research

Picture yourself on a road trip without a destination in mind — driving aimlessly, not…

How Academic Editors Can Enhance the Quality of Your Manuscript

Avoiding desk rejection Detecting language errors Conveying your ideas clearly Following technical requirements

Top 4 Guidelines for Health and Clinical Research Report

Top 10 Questions for a Complete Literature Review

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Open access

- Published: 16 November 2020

Navigating the qualitative manuscript writing process: some tips for authors and reviewers

- Chris Roberts ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8613-682X 1 ,

- Koshila Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8504-1052 2 &

- Gabrielle Finn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0419-694X 3

BMC Medical Education volume 20 , Article number: 439 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

10 Citations

27 Altmetric

Metrics details

An Editorial to this article was published on 04 August 2022

Qualitative research explores the ‘black box’ of how phenomena are constituted. Such research can provide rich and diverse insights about social practices and individual experiences across the continuum of undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing education, sectors and contexts. Qualitative research can yield unique data that can complement the numbers generated in quantitative research, [ 1 ] by answering “how” and “why” research questions. As you will notice in this paper, qualitative research is underpinned by specific philosophical assumptions, quality criteria and has a lexicon or a language specific to it.

A simple search of BMC Medical Education suggests that there are over 800 papers that employ qualitative methods either on their own or as part of a mixed methods study to evaluate various phenomena. This represents a considerable investment in time and effort for both researchers and reviewers. This paper is aimed at maximising this investment by helping early career researchers (ECRs) and reviewers new to the qualitative research field become familiar with quality criteria in qualitative research and how these can be applied in the qualitative manuscript writing process. Fortunately, there are numerous guidelines for both authors and for reviewers of qualitative research, including practical “how to” checklists [ 2 , 3 ]. These checklists can be valuable tools to confirm the essential elements of a qualitative study for early career researchers (ECRs). Our advice in this article is not intended to replace such “how to” guidance. Rather, the suggestions we make are intended to help ECRs increase their likelihood of getting published and reviewers to make informed decisions about the quality of qualitative research being submitted for publication in BMC Medical Education. Our advice is themed around long-established criteria for the quality of qualitative research developed by Lincoln and Guba [ 4 ]. (see Table 1 ) Each quality criterion outlined in Table 1 is further expanded in Table 2 in the form of several practical steps pertinent to the process of writing up qualitative research.

As a general starting point, the early career writer is advised to consult previously published qualitative papers in the journal to identify the genre (style) and relative emphasis of different components of the research paper. Patton [ 5 ] advises researchers to “FOCUS! FOCUS! FOCUS!” in deciding which components to include in the paper, highlighting the need to exclude side topics that add little to the narrative and reduce the cognitive load for readers and reviewers alike. Authors are also advised to do significant re-writing, rephrasing, re-ordering of initial drafts, to remove faulty grammar, and addresses stylistic and structural problems [ 6 ]. They should be mindful of “the golden thread,” that is their central argument that holds together the literature review, the theoretical and conceptual framework, the research questions, methodology, the analysis and organisation of the data and the conclusions. Getting a draft reviewed by someone outside of the research/writing team is one practical strategy to ensure the manuscript is well presented and relates to the plausibility element.

The introduction of a qualitative paper can be seen as beginning a conversation. Lingard advises that in this conversation, authors need to persuade the reader and reviewer of the strength, originality and contributions of their work [ 7 ]. In constructing a persuasive rationale, ECRs need to clearly distinguish between the qualitative research phenomenon (i.e. the broad research issue or concept under investigation) and the research context (i.e. the local setting or situation) [ 5 ]. The introduction section needs to culminate in a qualitative research question/s. It is important that ECRs are aware that qualitative research questions need to be fine-tuned from their original state to reflect gaps in the literature review, the researcher/s’ philosophical stance, the theory used, or unexpected findings [ 8 ]. This links to the elements of plausibility and consistency outlined in Table 1 .

Also, in the introduction of a qualitative paper, ECRs need to explain the multiple “lenses” through which they have considered complex social phenomena; including the underpinning research paradigm and theory. A research paradigm reveals the researcher/s’ values and assumptions about research and relates to axiology (what do you value?), ontology (what is out there to know?) epistemology (what and how can you know it?), and methodology (how do you go about acquiring that knowledge?) [ 9 ] ECRs are advised to explicitly state their research paradigm and its underpinning assumptions. For example, Ommering et al., state “We established our research within an interpretivist paradigm, emphasizing the subjective nature in understanding human experiences and creation of reality.” [ 10 ] Theory refers to a set of concepts or a conceptual framework that helps the writer to move beyond description to ‘explaining, predicting, or prescribing responses, events, situations, conditions, or relationships.’ [ 11 ] Theory can provide comprehensive understandings at multiple levels, including: the macro or grand level of how societies work, the mid-range level of how organisations operate; and the micro level of how people interact [ 12 ]. Qualitative studies can involve theory application or theory development [ 5 ]. ECRs are advised to briefly summarise their theoretical lens and identify what it means to consider the research phenomenon, process, or concept being studied with that specific lens. For example, Kumar and Greenhill explain how the lens of workplace affordances enabled their paper to draw “attention to the contextual, personal and interactional factors that impact on how clinical educators integrate their educational knowledge and skills into the practice setting, and undertake their educational role.” [ 13 ] Ensuring that the elements of theory and research paradigm are explicit and aligned, enhances plausibility, consistency and transparency of qualitative research. The use of theory can also add to the currency of research by enabling a new lens to be cast on a research phenomenon, process, or concept and reveal something previously unknown or surprising.

Moving to the methods, methodology is a general approach to studying a research topic and establishes how one will go about studying any phenomenon. In contrast, methods are specific research techniques and in qualitative research, data collection methods might include observation or interviewing, or photo elicitation methods, while data analysis methods may include content analysis, narrative analysis, or discourse analysis to mention a few [ 8 ]. ECRs will need to ensure the philosophical assumptions, methodology and methods follow from the introduction of a manuscript and the research question/s, [ 3 ] and this enhances the consistency and transparency elements. Moreover, triangulation or the combining of multiple observers, theories, methods, and data sources, is vital to overcome the limitation of singular methods, lone analysts, and single-perspective theories or models [ 8 ]. ECRs should report on not only what was triangulated but also how it was performed, thereby enhancing the elements of plausibility and consistency. For example, Touchie et al., describe using three researchers, three different focus groups, and representation of three different participant cohorts to ensure triangulation [ 14 ]. When it comes to the analysis of qualitative data, ECRs may claim they have used a specific methodological approach (e.g. interpretative phenomenological approach or a grounded theory approach) whereas the analytical steps are more congruent with a more generalist approach, such as thematic analysis [ 15 ]. ECRs are advised that such methodological approaches are founded on a number of philosophical considerations which need to inform the framing and conduct of a study, not just the analysis process. Alignment between the methodology and the methods informs the consistency, transparency and plausibility elements.

Comprehensively describing the research context in a way that is understandable to an international audience helps to illuminate the specific ‘laboratory’ for the research, and how the processes applied or insights generated in this ‘laboratory’ can be adapted or translated to other contexts. This addresses the relevancy element. To further enhance plausibility and relevance, ECRs should situate their work clearly on the evaluation–research continuum. Although not a strictly qualitative research consideration, evaluation focuses mostly on understanding how specific local practices may have resulted in specific outcomes for learners. While evaluation is vital for quality assurance and improvement, research has a broader and strategic focus and rates more highly against the currency and relevancy criteria. ECRs are more likely to undertake evaluation studies aimed at demonstrating the impact and outcomes of an educational intervention in their local setting, consistent with level one of Kirkpatrick’s criteria [ 16 ]. For example, Palmer and colleagues explain that they aimed to “develop and evaluate a continuing medical education (CME) course aimed at improving healthcare provider knowledge” [ 17 ]. To be competitive for publication, evaluation studies need to (measure and) report on at least level two and above of Kirkpatrick’s criteria. Learning how to problematise and frame the investigation of a problem arising from practice as research, provides ECRs with an opportunity to adopt a more critical and scholarly stance.

Also, in the methods, ECRs may provide detail about the study context and participants but little in the way of personal reflexive statements. Unlike quantitative research which claims that knowledge is objective and seeks to remove subjective influences, qualitative research recognises that subjectivity is inherent and that the researcher is directly involved in interpreting and constructing meanings [ 8 ]. For example, Bindels and colleagues provide a clear and concise description about their own backgrounds making their ‘lens’ explicit and enabling the reader to understand the multiple perspectives that have informed their research process [ 18 ]. Therefore, a clear description of the researcher/s position and relationship to the research phenomenon, context and participants, is vital for transparency, relevance and plausibility. We three are all experienced qualitative researchers, writers, reviewers and are associate editors for BMC Medical Education. We are situated in this research landscape as consumers, architects, and arbiters and we engage in these roles in collaboration with others. This provides a useful vantage point from which to provide commentary on key elements which can cause frustration for would-be authors and reviewers of qualitative research papers [ 19 ].

In the discussion of a qualitative paper, ECRs are encouraged to make detailed comments about the contributions of their research and whether these reinforce, extend, or challenge existing understandings based on an analysis that is theoretically or socially significant [ 20 ]. As an example, Barratt et al., found important data to inform the training of medical interns in the use of personal protective equipment during the COVID 19 pandemic [ 21 ]. ECRs are also expected to address the “so what” question which relates to the the consequence of findings for policy, practice and theory. Authors will need to explicitly outline the practical, theoretical or methodological implications of the study findings in a way that is actionable, thereby enhancing relevance and plausibility. For example, Burgess et al., presented their discussion according to four themes and outlined associated implications for individuals and institutions [ 22 ]. A balanced view of the research can be presented by ensuring there is congruence between the data and the claims made and searching the data and/or literature for evidence that disconfirms the findings. ECRs will also need to put forward the sources of uncertainty (rather than limitations) in their research and argue what these may mean for the interpretations made and how the contributions to knowledge could be adopted by others in different contexts [ 23 ]. This links to the plausibility and transparency elements.

In conclusion

Qualitative research is underpinned by specific philosophical assumptions, quality criteria and a lexicon, which ECRs and reviewers need to be mindful of as they navigate the qualitative manuscript writing and reviewing processes. We hope that the guidance provided here is helpful for ECRs in preparing submissions and for reviewers in making informed decisions and providing quality feedback.

Silverman D. Introducing Qualitative Research in Silverman D (Ed) Qualitative Research, 4th Edn. London: Sage; 1984. p. 3–14.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Article Google Scholar

Tai J, Ajjawi R. Undertaking and reporting qualitative research. Clin Teach. 2016;13(3):175–82.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1985. p. 1995.

Google Scholar

Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th Edn. Thousan Oaks: Sage publications; 2014.

Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage; 2013.

Lingard L. Joining a conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(5):252–3.

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research Methods in Education. 8th Edn. Abingdon: Routledge; 2019.

Brown MEL, Dueñas AN. A medical science Educator’s guide to selecting a research paradigm: building a basis for better research. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(1):545–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-019-00898-9 .

Ommering BWC, Wijnen-Meijer M, Dolmans DHJM, Dekker FW, van Blankenstein FM. Promoting positive perceptions of and motivation for research among undergraduate medical students to stimulate future research involvement: a grounded theory study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):204. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02112-6 .

Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J, Herber O. How theory is used and articulated in qualitative research: development of a new typology. Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:135–41.

Reeves S, Albert M, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Why use theories in qualitative research? BMJ. 2008;7;337:a949. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a949 .

Kumar K, Greenhill J. Factors shaping how clinical educators use their educational knowledge and skills in the clinical workplace: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0590-8 .

Touchie C, Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L. Teaching and assessing procedural skills: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-69 .

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Yardley S, Dornan T. Kirkpatrick’s levels and education ‘evidence’. Med Educ. 2012;46(1):97–106.

Palmer RC, Samson R, Triantis M, Mullan ID. Development and evaluation of a web-based breast cancer cultural competency course for primary healthcare providers. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):59.

Bindels E, Verberg C, Scherpbier A, Heeneman S, Lombarts K. Reflection revisited: how physicians conceptualize and experience reflection in professional practice – a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1218-y .

Finlay L. “Outing” the researcher: the provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:531–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973202129120052 .

Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE guide no. 70. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):850–61. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.704439 .

Barratt R, Wyer M, Hor S-y, Gilbert GL. Medical interns’ reflections on their training in use of personal protective equipment. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):328. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02238-7 .

Burgess A, Roberts C, Clark T, Mossman K. The social validity of a national assessment Centre for selection into general practice training. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):261.

Lingard L. The art of limitations. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(3):136–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-015-0181-0 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Education Office, Sydney Medical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Chris Roberts

Prideaux Centre for Research in Health Professions Education, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Koshila Kumar

Division of Medical Education, School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, The University of Manchester, M13 9NT, Manchester, UK

Gabrielle Finn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CR and KK wrote the first draft. All three authors contributed to severally revising the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chris Roberts .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Roberts, C., Kumar, K. & Finn, G. Navigating the qualitative manuscript writing process: some tips for authors and reviewers. BMC Med Educ 20 , 439 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02370-4

Download citation

Published : 16 November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02370-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Preparing your manuscript.

What are you submitting? The main manuscript document The title page How do I format my article? Sage Author Services

What are you submitting?

Sage journals publish a variety of different article types, from original research, review articles, to commentaries and opinion pieces. Please view your chosen journal’s submission guidelines for information on what article types are published and what the individual requirements are for each. Below are general guidelines for submitting an original research article.

Whatever kind of article you are submitting, remember that the language you use is important. We are committed to promoting equity throughout our publishing program, and we believe that using language is a simple and powerful way to ensure the communities we serve feel welcomed, respected, safe, and able to fully engage with the publishing process and our published content. Inclusive language considerations are especially important when discussing topics like age, appearance, disability, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, race, religion, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, emigration status, and weight. We have produced an Inclusive Language Guide that recommends preferred terminology on these topics. We recognize that language is constantly evolving and we’re committed to ensuring that this guide is continuously updated to reflect changing practices. The guide isn't exhaustive, but we hope it serves as a helpful starting point.

The main manuscript document

Have a look at your chosen journal’s submission guidelines for information on what sections should be included in your manuscript. Generally there will be an Abstract, Introduction, Methodology, Results, Discussion, Conclusion, Acknowledgments, Statements and Declarations section, and References. Be sure to remove any identifying information from the main manuscript if you are submitting to a journal that has a double-anonymized peer review policy and instead include this on a separate title page. See the Sage Journal Author Gateway for detailed guidance on making an anonymous submission .

Your article title, keywords, and abstract all contribute to its position in search engine results, directly affecting the number of people who see your work. For details of what you can do to influence this, visit How to help readers find your article online .