Market equilibrium

- Definition of market equilibrium – A situation where for a particular good supply = demand. When the market is in equilibrium, there is no tendency for prices to change. We say the market-clearing price has been achieved.

- A market occurs where buyers and sellers meet to exchange money for goods.

- The price mechanism refers to how supply and demand interact to set the market price and amount of goods sold.

- At most prices, planned demand does not equal planned supply. This is a state of disequilibrium because there is either a shortage or surplus and firms have an incentive to change the price.

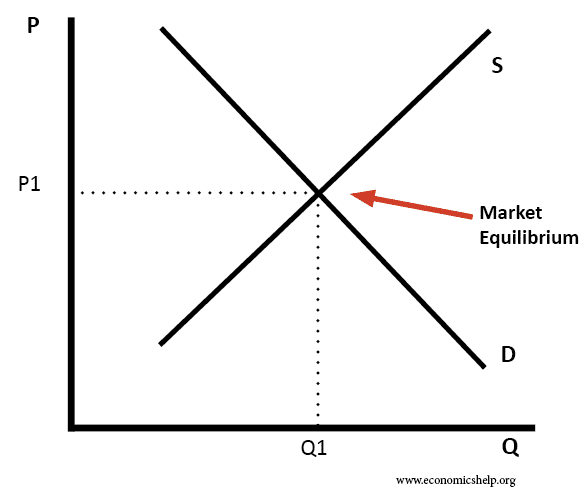

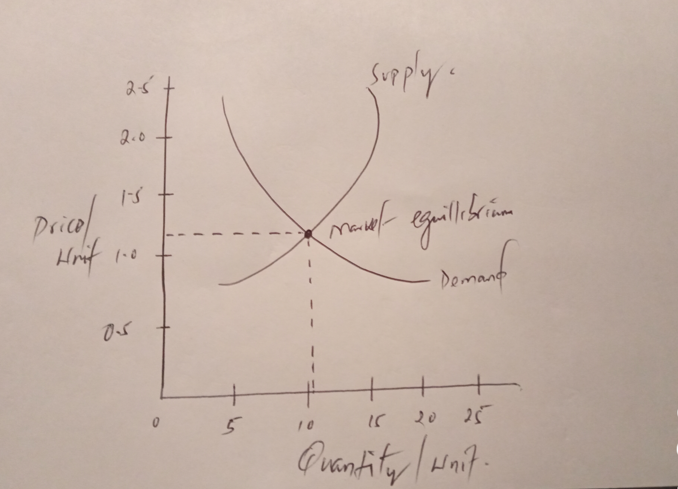

Market equilibrium can be shown using supply and demand diagrams

In the diagram below, the equilibrium price is P1. The equilibrium quantity is Q1.

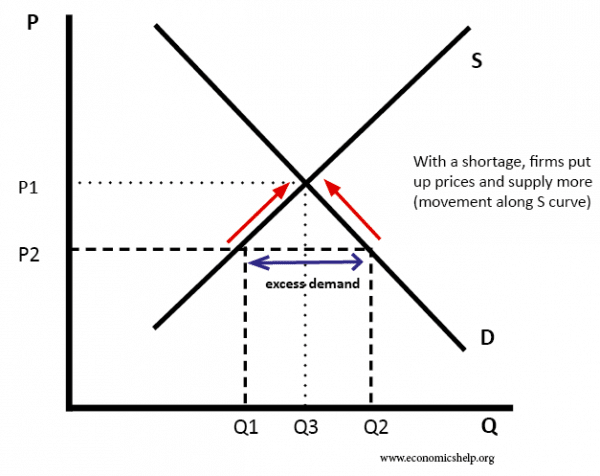

If price is below the equilibrium

- In the above diagram, price (P2) is below the equilibrium. At this price, demand would be greater than the supply. Therefore there is a shortage of (Q2 – Q1)

- If there is a shortage, firms will put up prices and supply more. As price rises, there will be a movement along the demand curve and less will be demanded.

- Therefore the price will rise to P1 until there is no shortage and supply = demand.

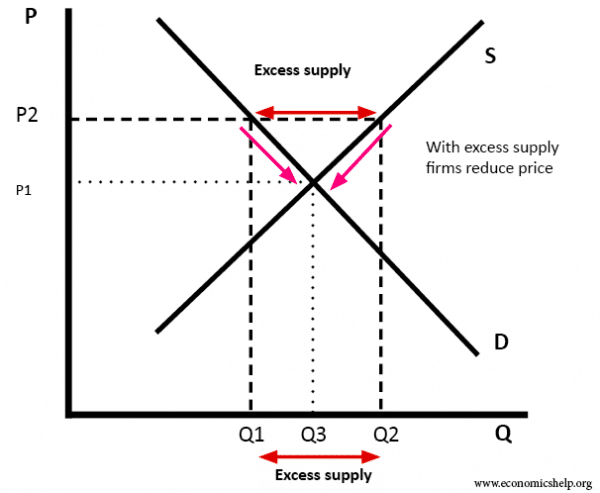

If price is above the equilibrium

- If price was at P2, this is above the equilibrium of P1. At the price of P2, then supply (Q2) would be greater than demand (Q1) and therefore there is too much supply. There is a surplus. (Q2-Q1)

- Therefore firms would reduce price and supply less. This would encourage more demand and therefore the surplus will be eliminated. The new market equilibrium will be at Q3 and P1.

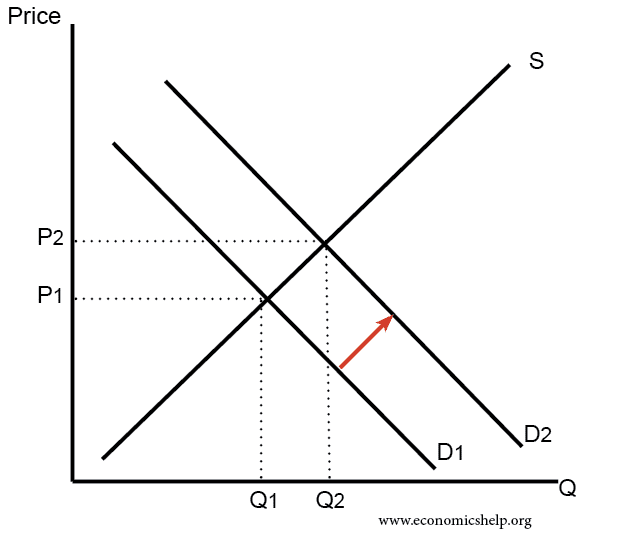

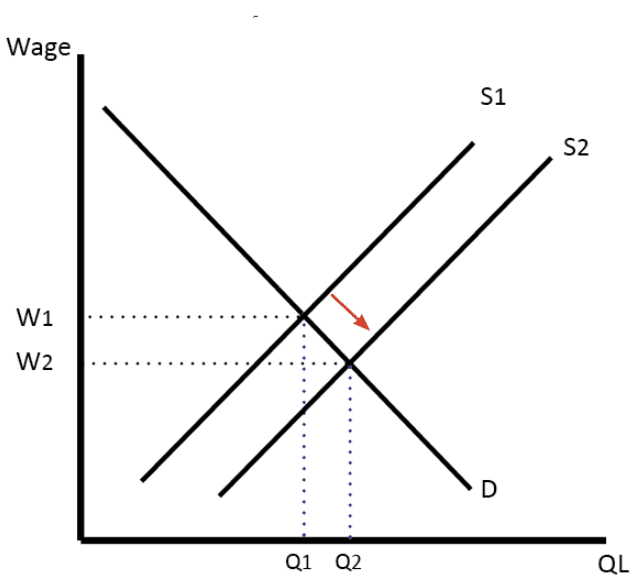

Movements to a new equilibrium

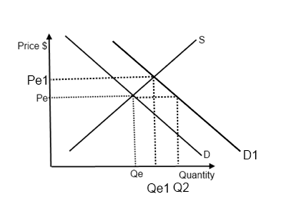

- Increase in demand

If there was an increase in income the demand curve would shift to the right (D1 to D2). Initially, there would be a shortage of the good. Therefore the price and quantity supplied will increase leading to a new equilibrium at Q2, P2.

2. Increase in supply

An increase in supply would lead to a lower price and more quantity sold.

Related posts

- Finding market equilibrium with equations

- Price mechanism in the long-term

- Economic rent and transfer earnings

- The economics of the price of coffee

First published 28 Nov 2010. Last updated 28 Nov 2019

10 Market Equilibrium: Supply and Demand

Supply and Demand

The Policy Question Should the Government Provide Public Marketplaces?

In the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, DC, the Eastern Market is a large building and grounds owned and operated by the city government. Farmers, bakers, cheese makers, and other merchants of food, arts, and crafts assemble there to sell their wares. Marketplaces like it were once a common feature of cities in the United States and Europe but are now a relative rarity. Many have disappeared due to citizens questioning whether the government should be supporting these marketplaces.

So why does the government play a role in providing some markets? The answer is found in the way markets create benefits for the citizens they serve. In this chapter, we explore how prices and quantities are set in market equilibrium, how changes in supply and demand factors cause market equilibrium to adjust, and how we measure the benefit of markets to society.

Markets are often private in the sense that the government is not involved in their creation or presence; instead, they are generated by the desire of private individuals to engage in an exchange for a particular good. Sometimes, however, the government plays an active role in establishing and managing markets. At the end of the chapter, we will study why this occurs, using the Eastern Market as an example.

Exploring the Policy Question

- Is public investment in marketplaces justified and if so why?

Learning Objectives

10.1 what is a market.

Learning Objective 10.1 : Identify the characteristics of a market.

10.2 Market Equilibrium: The Supply and Demand Curves Together

Learning Objective 10.2 : Determine the equilibrium price and quantity for a market, both graphically and mathematically.

10.3 Excess Supply and Demand

Learning Objective 10.3 : Calculate and graph excess supply and excess demand.

10.4 Measuring Welfare and Pareto Efficiency

Learning Objective 10.4 : Calculate consumer surplus, producer surplus, and deadweight loss for a market.

10.5 Policy Example Should the Government Provide Public Marketplaces?

Learning Objective 10.5 : Apply the concept of economic welfare to the policy of publicly supported marketplaces.

10.1 What Is a Market?

In chapter 9 , we found out that the market supply curve comes from the cost structure of individual firms, which in turn comes from their technology, as we discovered in chapter 7 . In chapter 5 , we found out where the demand curve comes from—the individual utility maximization problems of individual consumers. In both cases, we assumed the demand for and supply of a specific good or service. In other words, we were describing a particular market.

A market is characterized as a particular location where a specific good or service is being sold at a defined time. So, for example, we might talk about

- the market for eggs in Nashville, Tennessee, in April 2016;

- the market for rolled aluminum in the United States in 2015; or

- the market for radiological diagnostic services worldwide in the last decade.

In addition, for whatever item, time, and place we describe, there must be both buyers and sellers in order for a market to exist. A market is where buyers and sellers exchange or where there is both demand and supply.

We tend to talk about markets somewhat loosely when studying economics. For example, we might discuss the market for orange juice and leave the time and place undefined in order to keep things simple. Or we might just say that we are looking at the market for denim jeans in the United States. The difficulty with these simplifications is that we can lose sight of the basic assumptions about markets that are necessary for our analysis of them.

The six necessary assumptions for markets are the following:

- A market is for a single good or service.

- All goods or services bought and sold in a market are identical.

- The good or service sells for a single price.

- All consumers know everything about the product, including how much they value it.

- There are many buyers and sellers, and they are known to each other and can interact.

- All the costs and benefits of a transaction accrue only to the buyers and sellers who engage in them.

These assumptions are actually pretty easy to understand. They guarantee that the buyers who value the good more than it costs sellers to produce it will find a seller willing to sell to them. In other words, there are no transactions that don’t happen because the buyer doesn’t know how much they like the product or because a buyer can’t find a seller, or vice versa.

Of course, the assumptions describe an ideal market. In reality, many markets are not exactly like this, and later, in chapters 20 , 21 , and 22 , we will examine what happens when these assumptions fail to hold.

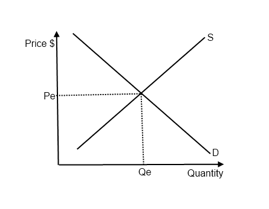

Market equilibrium is the point where the quantity supplied by producers and the quantity demanded by consumers are equal. When we put the demand and supply curves together, we can determine the equilibrium price : the price at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. In figure 10.1 , the equilibrium price is shown as [latex]P^*[/latex], and it is precisely where the demand curve and supply curve cross. This makes sense—the demand curve gives the quantity demanded at every price and the supply curve gives the quantity supplied at every price so there is one price that they have in common, which is at the intersection of the two curves.

Graphing the supply and demand curves to locate their intersection is one way to find the equilibrium price. We can also find this quantity mathematically. Consider a demand curve for stereo headphones that is described by the following function:

[latex]Q^D = 1,800 − 20P[/latex]

Note that in general, we draw graphs of functions with the independent variable on the horizontal axis and the dependent variable on the vertical axis. In the case of supply and demand curves, however, we draw them with quantity on the horizontal axis and price on the vertical. Because of this, it is sometimes easier to express the demand relationship as an inverse demand curve : the demand curve expressed as price as a function of quantity. In our example, this would be

[latex]P = 90 − 0.05Q^D[/latex].

This is just the original demand curve solved for [latex]P[/latex] instead of [latex]Q^D[/latex]. In the inverse demand curve, the vertical intercept is easy to see from the equation: demand for headphones stops at the price of $90. No consumer is willing to pay $90 or more for headphones.

Similarly, the supply curve can be represented as a mathematical function. For example, consider a supply curve described by the following function:

[latex]Q^S = 50P—1,000[/latex]

Similar to the demand curve, we can express this as an inverse supply curve : the supply curve expressed as price as a function of quantity. In this case, the inverse supply curve would be

[latex]P = 0.02Q^S + 20[/latex].

Here the vertical intercept, $20, gives us the minimum price to get a seller to sell headphones. At prices of $20 or less, there will be no supply. So we know that the equilibrium price should be between $20 and $90.

Solving for the equilibrium price and quantity is simply a matter of setting [latex]Q^D=Q^S[/latex] and solving for the price that makes this equality happen. In our example, setting [latex]Q^D=Q^S[/latex] yields

[latex]1,800 − 20P = 50P—1,000[/latex]

[latex]70P = 2,800[/latex]

[latex]P = $40[/latex]

At [latex]P = $40[/latex], the quantity demanded and supplied can be found from the demand and supply curves:

[latex]Q^D = 1,800 − 20(40) = 1,000[/latex]

[latex]Q^S = 50(40)—1,000 = 1,000[/latex]

That these two quantities match is no accident; this was the condition we set at the outset—that quantity supplied equals quantity demanded. So we know that a price of $40 per unit is the equilibrium price.

These supply and demand curves for headphones are graphed in figure 10.2 below, and their intersection confirms the equilibrium price we calculated mathematically.

Note that we have also identified the equilibrium quantity , [latex]Q^*[/latex]—the quantity at which supply equals demand. At $40 per unit, one thousand headphones are demanded, and exactly one thousand headphones are supplied. The equilibrium quantity has nothing to do with any kind of coordination or communication among the buyers and sellers; it has only to do with the price in the market. Seeing a unit price of $40, consumers demand one thousand units. Independently, sellers who see that price will choose to supply exactly one thousand units.

It makes sense that the equilibrium price is the one that equates quantity demanded with quantity supplied, but how does the market get to this equilibrium? Is this just an accident? No. The market price will automatically adjust to a point where supply matches demand. Excess supply or demand in a market will trigger such an adjustment.

To understand this equilibrating feature of the market price, let’s return to our headphones example. Suppose the price is $50 instead of $40. At this price, we know from the supply curve that fifteen hundred units will be supplied to the market. Also, from the demand curve, we know that eight hundred units will be demanded. Thus there will be an excess supply of seven hundred units, as shown in figure 10.3 .

Excess supply occurs when, at a given price, firms supply more of a good than what consumers demand. These are goods that have been produced by the firms that supply the market and have not found any willing buyers. Firms will want to sell these goods and know that by lowering the price, more buyers will appear. So this excess supply of goods will lead to a price decrease. The price will continue to fall as long as the excess supply conditions exist. In other words, price will continue to fall until it reaches $40.

The same logic applies to situations where the price is below the intersection of supply and demand. Suppose the price of headphones is $30. We know from the demand curve that at this price, consumers will demand twelve hundred units. We also know from the supply curve that at this price, suppliers will supply five hundred units. So at $30, there will be excess demand of seven hundred units, as shown in figure 10.4 .

Excess demand occurs when, at a given price, consumers demand more of a good than firms supply. Consumers who are not able to find goods to purchase will offer more money in an effort to entice suppliers to supply more. Suppliers who are offered more money will increase supply, and this will continue to happen as long as the price is below $40 and there is excess demand.

Only at a price of $40 is the pressure for prices to rise or fall relieved and will the price remain constant.

From our study of markets so far, it is clear that they can contribute to the economic well-being of both buyers and sellers. The term welfare , as it is used in economics, refers to the economic well-being of society as a whole, including producers and consumers. We can measure welfare for particular market situations.

To understand the economic concept of welfare—and how to quantify it—it is useful to think about the weekly farmers’ market in Ithaca, New York. The market is a place where local growers can sell their produce directly to consumers throughout the summer. It is very successful, and many local residents go to the market to buy produce. Now consider the specific example of tomatoes. What is this market worth to the tomato sellers and buyers that transact in the market?

Suppose a farmer has a minimum willingness-to-accept price of $1 for an heirloom tomato. This price could be based on the farmer’s cost of production or the value she places on consuming the tomato herself. Suppose also that there is a consumer who really wants an heirloom tomato to add to his salad that evening and is willing to pay up to $3 for one. If these two people meet each other at the market and agree on a price of $2, how much benefit do they each get?

The seller receives $2, and it cost her $1 to provide the tomato, so she is $1 better off, the difference between what she received and what she would have accepted for the tomato. Likewise, the buyer pays $2 but receives $3 in benefit from the tomato, since that was his willingness to pay; his net benefit is the difference, or $1. The seller and buyer are both $1 better off because they had the opportunity to meet and transact. Without this opportunity, the seller would have stayed at home with the tomato and been no better or worse off, and the buyer would not have a tomato for his salad but would be no better or worse off.

The difference between the price received and the willingness-to-accept price is called the producer surplus [latex](PS)[/latex]. The difference between the willingness-to-pay price and the price paid is called the consumer surplus [latex](CS)[/latex]. The sum of these two surpluses is called total surplus [latex](TS)[/latex]. So the producer surplus in the tomato example is $1, the consumer surplus is $1, and the total surplus is $2. This is the surplus generated by one transaction; if we add up all such transactions in the market, we get a measure of the consumer and producer surplus from the market.

Quantifying surplus for an entire market is easy to do with a graph. Let’s return to our previous example of headphones and find the consumer and producer surplus.

Figure 10.5 shows that the consumer surplus is the area above the equilibrium price and below the demand curve—the green triangle in the figure. Similarly, the producer surplus is the area below the equilibrium price and above the supply curve—the red triangle in the figure. The area of each surplus triangle is easy to calculate using the formula for the area of a triangle: [latex]\frac{1}{2}bh[/latex], where [latex]b[/latex] is base and [latex]h[/latex] is height.

In the case of consumer surplus, the triangle has a base of one thousand, the distance from the origin to [latex]Q^*[/latex], and a height of $50, the difference between $90, the vertical intercept, and [latex]P^*[/latex], which is $40.

[latex]\text{Consumer surplus} = \frac{1}{2}(1,000)($50) = $25,000[/latex]

[latex]\text{Producer surplus} = \frac{1}{2}(1,000)($20)= $10,000[/latex].

Total surplus created by this market is the sum of the two, or $35,000. This is the measure of how much value the market creates through its enabling of these transactions. Without the ability to come together in this market, the buyers and sellers would miss out on the opportunity to capture this surplus.

We say that a market is efficient when the entire potential surplus has been created. Such a market is an example of Pareto efficiency —an allocation of goods and services in which no redistribution can occur without making someone worse off. Think about the distribution of goods in the headphones example. All the buyers and sellers that transact are made better off by the transaction because they gain some surplus from it. If they didn’t, they would not voluntarily trade. None of the trades that shouldn’t happen do. For example, if there were more than one thousand units exchanged, it would mean sellers were selling to buyers who valued the good less than the sellers’ cost of production, where the supply curve is above the demand curve, and one or both of the parties would be worse off because of the exchange.

Another way to see that the market equilibrium outcome is efficient is if we arbitrarily limit the number of goods exchanged to nine hundred. Let’s call this maximum quantity restriction [latex]\overline Q[/latex], where the bar above the Q indicates that it is fixed at that quantity. There are one hundred surplus-creating transactions that don’t occur; this cannot be an efficient outcome because the entire potential surplus has not been created. The lost potential surplus has a name, deadweight loss [latex](DWL)[/latex]: the loss of total surplus that occurs when there is an inefficient allocation of resources. The blue triangle in figure 10.6 represents this deadweight loss.

We can calculate the value of the deadweight loss precisely, again using the formula for the area of a triangle. Since the demand function is [latex]Q^D=1,800 − 20P[/latex], the point on the demand curve that results in a demand of nine hundred is a price of $45. Similarly, if the supply function is given as [latex]Q^S=50P-1,000[/latex], the point on the supply curve that results in a quantity supplied of nine hundred is a price of $38. Thus the base of the triangle is $45 − $38, or $7, and the height is the difference between the one thousand units that are sold in the absence of a restriction and the nine-hundred-unit restricted quantity, or one hundred. So

[latex]DWL=\frac{1}{2}($7)(100)=$350[/latex].

The first question in determining whether a case can be made for the public provision of marketplaces, such as the Eastern Market in Washington, DC, is what would occur in the absence of such a market. If the buyers and sellers in these markets could easily access other markets, then it would be hard to argue that the marketplace is providing a net benefit. Similarly, if the commercial activity that takes place in this market is simply a diversion of similar activity that would have taken place elsewhere, then it is likely that there is little to no net benefit. So for the sake of this exercise, we will assume that the marketplace is providing an opportunity to these buyers and sellers that they would not otherwise have.

So given this assumption, are these marketplaces valuable? The simple answer, as long as transactions are occurring, is yes. We can see this from a simple diagram of a market for an individual good, let’s say fresh apples, that exists within the Eastern Market ( figure 10.7 ).

There is clearly a surplus being created by the apple transactions that take place within the market. This in itself is the primary argument for the marketplace. Buyers and sellers are able to transact and become better off for it. The value to those individuals is measured by surplus.

But a complete answer must compare the value to society of the markets to the cost to society of the marketplace itself. Does the total surplus created by the marketplace justify the cost?

Let’s return now to the key assumption—that a market for fresh apples would not exist without government support. Is this a reasonable assumption?

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when many public markets were founded, transportation was difficult, and bringing fresh food to support urban population centers was something local governments commonly did. Today, transportation is not nearly as difficult or costly. But although many areas are well served by grocery stores, where it is reasonable to expect customers will find fresh fruits and vegetables, other locations are characterized by food deserts . Food deserts are defined as urban neighborhoods and rural towns without ready access to fresh, healthy, and affordable food. Instead of supermarkets and grocery stores, these communities may have no food access or are served only by fast-food restaurants and convenience stores that offer few healthy, affordable food options. The lack of access contributes to a poor diet and can lead to higher levels of obesity and other diet-related diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease (US Department of Agriculture [USDA]).

The USDA estimates that 23.5 million people in the United States live in food deserts.

Although the Capitol Hill neighborhood experienced some hard times in the past, today it is prosperous and well served by grocery stores. So the need for government support of the Eastern Market there is less clear. In chapter 21 , we will explore public goods and externalities in detail and become better equipped to fully explore this issue.

- What other kinds of marketplaces can you think of that the government aids by providing infrastructure?

- Airports allow the market for airline travel to exist in a functional way. Most airports in the United States are run by local governments. Using the topics explored in this chapter, give a justification for government expenditures on airports.

- Should the District of Columbia government spend money on a market that primarily serves one neighborhood? Give reasons for and against.

REVIEW: TOPICS AND LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learn: key topics.

The point where the quantity supplied by producers and the quantity demanded by consumers are equal.

The demand curve expressed as price as a function of quantity:

[latex]P = 90 − 0.05Q^D[/latex]

The supply curve expressed as price as a function of quantity:

[latex]P = 20 - 0.03Q^S[/latex]

The price at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied.

[latex]Q^*[/latex]—the quantity at which supply equals demand.

When, at a given price, consumers demand more of a good than firms supply, i.e., the latest video game consoles.

When, at a given price, firms supply more of a good than what consumers demand, i.e., the sales of holiday merchandise once it has passed.

In economics, refers to the economic well-being of society as a whole, including producers and consumers.

The difference between the price received and the willingness-to-accept price.

The difference between the willingness-to-pay price and the price paid.

The sum of the consumer surplus and the producer surplus.

an allocation of goods and services in which no redistribution can occur without making someone worse off, i.e., both seller and buyer are gaining from the exchange–sellers are selling an amount that is equal to the demand curve and buyers are paying prices that indicate close to equilibrium price.

The loss of total surplus that occurs when there is an inefficient allocation of resources, i.e., a firm produces exactly 900 limited edition headphones worth $200 each. The demand tests out at 1000. There are 100 surplus-creating transactions that don’t occur–resources should have been allocated to make the 1000.

[latex]Q^S = 50P - 1000[/latex]

Determining Q* and P*

The above equation utilizes the relationship between quantity and price to determine a starting algorithm for drafting a supply curve. Review this relationship in chapter 9 .

Inverse supply curve

[latex]P = 20 − 0.03Q^S[/latex]

Derived from max production and minimum price to cover costs with profit.

Inverse demand curve

The original equation set to solve for P. In this inverse curve, the vertical intercept is very clear: demand for this product stops at $90. No one is willing to pay more than $90 for the product.

Solving for equilibrium price [latex](P^*)[/latex] and equilibrium quantity [latex]Q^*[/latex]

Solving for the equilibrium price and quantity is simply a matter of setting

[latex]Q^D=Q^S[/latex]

and solving for the price that makes this equality happen. In our example, setting [latex]Q^D=Q^S[/latex] yields

[latex]Q^D = 1,800 − 20(40) = 1,000[/latex] [latex]Q^S = 50(40)—1,000 = 1,000[/latex]

If the proper [latex]P^*[/latex] and [latex]Q^*[/latex] have been found, the two equations should be equal.

Issues of excess and deadweight loss [latex](DWL)[/latex]

Quantifying surplus is easy to do with a graph, see figure 10.5 in full-size via link or half-size below:

the consumer surplus is the area above the equilibrium price and below the demand curve—the green triangle in the figure. Similarly, the producer surplus is the area below the equilibrium price and above the supply curve—the red triangle in the figure. The area of each surplus triangle is easy to calculate using the formula for the area of a triangle, where [latex]b[/latex] is base and [latex]h[/latex] is height:

[latex]\frac{1}{2}bh[/latex]

Utilizing figures from the graph, the following formulas can be derived:

Consumer surplus

[latex]\text{Consumer surplus} = \frac{1}{2}(b)(h)[/latex]

where the area equals the total dollar amount of producer surplus, the base [latex](b)[/latex] is the distance from the origin to [latex]Q^*[/latex], and the height [latex](h)[/latex] is the difference between the maximum willing to pay price [latex]P_{max}[/latex], or the y-intercept, and [latex]P^*[/latex]. This can also be written thusly:

[latex]CS = \frac{1}{2}(Q^*-(O)((P_{max}-P^*))[/latex]

where [latex]O[/latex] is the origin of the supply curve and [latex]P_{max}[/latex] is the vertical intercept of the y-axis, and also the maximum price that anyone is willing to pay for the product.

Producer surplus

[latex]\text{Producer surplus} = \frac{1}{2}(1,000)($20)= $10,000[/latex]

[latex]\text{Producer surplus} = \frac{1}{2}(b)(h) = area[/latex]

where the area equals the total dollar amount of producer surplus, the base [latex](b)[/latex] is the distance from the origin to [latex]Q^*[/latex], and the height [latex](h)[/latex] is minimum price. This can also be written thusly:

[latex]PS = \frac{1}{2}(Q^*-O)(P_{min}) = area[/latex]

where [latex]O[/latex] is the origin of the supply curve and [latex]P_{min}[/latex] is the minimum willingness-to-accept price.

Total surplus

The sum of [latex]CS[/latex] and [latex]PS[/latex]

[latex]TS=CS+PS[/latex]

Deadweight loss [latex](DWL)[/latex]

The loss of total surplus that occurs when there is an inefficient allocation of resources.

[latex]DWL=\frac{1}{2}(P*^-P_Q)(Q*^-Q)[/latex]

Where [latex]P_Q[/latex] is the price determined by the supply/demand curves to be viable at the current output, [latex]Q[/latex]. See Figure 10.6 for full-size or see half-size below. Figure 10.6 illustrates utilizing a graph to develop a [latex]DWL[/latex] equation:

If a firm produces 900 headphones, but the [latex]Q^*[/latex] satates that 1000 is the optimum output, the lost surplus price would then equate to the difference between the price for 900 units [latex](P_Q, \text{in this case} P_900)[/latex], or $38, and the [latex]P^*[/latex], or $45. Thus the denominator would be 100 (1000-900) and the numerator $7 ($45-$38). The equation would look thus:

[latex]DWL=\frac{1}{2}($7)(100)=$350[/latex]

Media Attributions

- downtown-china-954864_1280 © binaryscalper is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1021Artboard-1 © Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 1022Artboard-1 © Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 1023Artboard-1 © Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 1024Artboard-1 © Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 1041Artboard-1 © Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 1042Artboard-1 © Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 1051Artboard-1 © Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

Intermediate Microeconomics Copyright © 2019 by Patrick M. Emerson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

3.1 Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium in Markets for Goods and Services

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain demand, quantity demanded, and the law of demand

- Explain supply, quantity supplied, and the law of supply

- Identify a demand curve and a supply curve

- Explain equilibrium, equilibrium price, and equilibrium quantity

First let’s first focus on what economists mean by demand, what they mean by supply, and then how demand and supply interact in a market.

Demand for Goods and Services

Economists use the term demand to refer to the amount of some good or service consumers are willing and able to purchase at each price. Demand is fundamentally based on needs and wants—if you have no need or want for something, you won't buy it. While a consumer may be able to differentiate between a need and a want, from an economist’s perspective they are the same thing. Demand is also based on ability to pay. If you cannot pay for it, you have no effective demand. By this definition, a person who does not have a drivers license has no effective demand for a car.

What a buyer pays for a unit of the specific good or service is called price . The total number of units that consumers would purchase at that price is called the quantity demanded . A rise in price of a good or service almost always decreases the quantity demanded of that good or service. Conversely, a fall in price will increase the quantity demanded. When the price of a gallon of gasoline increases, for example, people look for ways to reduce their consumption by combining several errands, commuting by carpool or mass transit, or taking weekend or vacation trips closer to home. Economists call this inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded the law of demand . The law of demand assumes that all other variables that affect demand (which we explain in the next module) are held constant.

We can show an example from the market for gasoline in a table or a graph. Economists call a table that shows the quantity demanded at each price, such as Table 3.1 , a demand schedule . In this case we measure price in dollars per gallon of gasoline. We measure the quantity demanded in millions of gallons over some time period (for example, per day or per year) and over some geographic area (like a state or a country). A demand curve shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded on a graph like Figure 3.2 , with quantity on the horizontal axis and the price per gallon on the vertical axis. (Note that this is an exception to the normal rule in mathematics that the independent variable (x) goes on the horizontal axis and the dependent variable (y) goes on the vertical axis. While economists often use math, they are different disciplines.)

Table 3.1 shows the demand schedule and the graph in Figure 3.2 shows the demand curve. These are two ways to describe the same relationship between price and quantity demanded.

Demand curves will appear somewhat different for each product. They may appear relatively steep or flat, or they may be straight or curved. Nearly all demand curves share the fundamental similarity that they slope down from left to right. Demand curves embody the law of demand: As the price increases, the quantity demanded decreases, and conversely, as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

Confused about these different types of demand? Read the next Clear It Up feature.

Clear It Up

Is demand the same as quantity demanded.

In economic terminology, demand is not the same as quantity demanded. When economists talk about demand, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities demanded at those prices, as illustrated by a demand curve or a demand schedule. When economists talk about quantity demanded, they mean only a certain point on the demand curve, or one quantity on the demand schedule. In short, demand refers to the curve and quantity demanded refers to a (specific) point on the curve.

Supply of Goods and Services

When economists talk about supply , they mean the amount of some good or service a producer is willing to supply at each price. Price is what the producer receives for selling one unit of a good or service . A rise in price almost always leads to an increase in the quantity supplied of that good or service, while a fall in price will decrease the quantity supplied. When the price of gasoline rises, for example, it encourages profit-seeking firms to take several actions: expand exploration for oil reserves; drill for more oil; invest in more pipelines and oil tankers to bring the oil to plants for refining into gasoline; build new oil refineries; purchase additional pipelines and trucks to ship the gasoline to gas stations; and open more gas stations or keep existing gas stations open longer hours. Economists call this positive relationship between price and quantity supplied—that a higher price leads to a higher quantity supplied and a lower price leads to a lower quantity supplied—the law of supply . The law of supply assumes that all other variables that affect supply (to be explained in the next module) are held constant.

Still unsure about the different types of supply? See the following Clear It Up feature.

Is supply the same as quantity supplied?

In economic terminology, supply is not the same as quantity supplied. When economists refer to supply, they mean the relationship between a range of prices and the quantities supplied at those prices, a relationship that we can illustrate with a supply curve or a supply schedule. When economists refer to quantity supplied, they mean only a certain point on the supply curve, or one quantity on the supply schedule. In short, supply refers to the curve and quantity supplied refers to a (specific) point on the curve.

Figure 3.3 illustrates the law of supply, again using the market for gasoline as an example. Like demand, we can illustrate supply using a table or a graph. A supply schedule is a table, like Table 3.2 , that shows the quantity supplied at a range of different prices. Again, we measure price in dollars per gallon of gasoline and we measure quantity supplied in millions of gallons. A supply curve is a graphic illustration of the relationship between price, shown on the vertical axis, and quantity, shown on the horizontal axis. The supply schedule and the supply curve are just two different ways of showing the same information. Notice that the horizontal and vertical axes on the graph for the supply curve are the same as for the demand curve.

The shape of supply curves will vary somewhat according to the product: steeper, flatter, straighter, or curved. Nearly all supply curves, however, share a basic similarity: they slope up from left to right and illustrate the law of supply: as the price rises, say, from $1.00 per gallon to $2.20 per gallon, the quantity supplied increases from 500 gallons to 720 gallons. Conversely, as the price falls, the quantity supplied decreases.

Equilibrium—Where Demand and Supply Intersect

Because the graphs for demand and supply curves both have price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis, the demand curve and supply curve for a particular good or service can appear on the same graph. Together, demand and supply determine the price and the quantity that will be bought and sold in a market.

Figure 3.4 illustrates the interaction of demand and supply in the market for gasoline. The demand curve (D) is identical to Figure 3.2 . The supply curve (S) is identical to Figure 3.3 . Table 3.3 contains the same information in tabular form.

Remember this: When two lines on a diagram cross, this intersection usually means something. The point where the supply curve (S) and the demand curve (D) cross, designated by point E in Figure 3.4 , is called the equilibrium . The equilibrium price is the only price where the plans of consumers and the plans of producers agree—that is, where the amount of the product consumers want to buy (quantity demanded) is equal to the amount producers want to sell (quantity supplied). Economists call this common quantity the equilibrium quantity . At any other price, the quantity demanded does not equal the quantity supplied, so the market is not in equilibrium at that price.

In Figure 3.4 , the equilibrium price is $1.40 per gallon of gasoline and the equilibrium quantity is 600 million gallons. If you had only the demand and supply schedules, and not the graph, you could find the equilibrium by looking for the price level on the tables where the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied are equal.

The word “equilibrium” means “balance.” If a market is at its equilibrium price and quantity, then it has no reason to move away from that point. However, if a market is not at equilibrium, then economic pressures arise to move the market toward the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity.

Imagine, for example, that the price of a gallon of gasoline was above the equilibrium price—that is, instead of $1.40 per gallon, the price is $1.80 per gallon. The dashed horizontal line at the price of $1.80 in Figure 3.4 illustrates this above-equilibrium price. At this higher price, the quantity demanded drops from 600 to 500. This decline in quantity reflects how consumers react to the higher price by finding ways to use less gasoline.

Moreover, at this higher price of $1.80, the quantity of gasoline supplied rises from 600 to 680, as the higher price makes it more profitable for gasoline producers to expand their output. Now, consider how quantity demanded and quantity supplied are related at this above-equilibrium price. Quantity demanded has fallen to 500 gallons, while quantity supplied has risen to 680 gallons. In fact, at any above-equilibrium price, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. We call this an excess supply or a surplus .

With a surplus, gasoline accumulates at gas stations, in tanker trucks, in pipelines, and at oil refineries. This accumulation puts pressure on gasoline sellers. If a surplus remains unsold, those firms involved in making and selling gasoline are not receiving enough cash to pay their workers and to cover their expenses. In this situation, some producers and sellers will want to cut prices, because it is better to sell at a lower price than not to sell at all. Once some sellers start cutting prices, others will follow to avoid losing sales. These price reductions in turn will stimulate a higher quantity demanded. Therefore, if the price is above the equilibrium level, incentives built into the structure of demand and supply will create pressures for the price to fall toward the equilibrium.

Now suppose that the price is below its equilibrium level at $1.20 per gallon, as the dashed horizontal line at this price in Figure 3.4 shows. At this lower price, the quantity demanded increases from 600 to 700 as drivers take longer trips, spend more minutes warming up the car in the driveway in wintertime, stop sharing rides to work, and buy larger cars that get fewer miles to the gallon. However, the below-equilibrium price reduces gasoline producers’ incentives to produce and sell gasoline, and the quantity supplied falls from 600 to 550.

When the price is below equilibrium, there is excess demand , or a shortage —that is, at the given price the quantity demanded, which has been stimulated by the lower price, now exceeds the quantity supplied, which has been depressed by the lower price. In this situation, eager gasoline buyers mob the gas stations, only to find many stations running short of fuel. Oil companies and gas stations recognize that they have an opportunity to make higher profits by selling what gasoline they have at a higher price. As a result, the price rises toward the equilibrium level. Read Demand, Supply, and Efficiency for more discussion on the importance of the demand and supply model.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/3-1-demand-supply-and-equilibrium-in-markets-for-goods-and-services

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Submit Content

- Business And Management

- Social Anthropology

- World Religions

- Biology 2016

- Design Technology

- Environmental Systems And Societies

- Sports Exercise And Health Science

- Mathematics Studies

- Mathematics SL

- Mathematics HL

- Computer Science

- Visual Arts

- Theory Of Knowledge

- Extended Essay

- Creativity Activity Service

- Video guides

- External links

1 Competitive markets: Demand and supply

Markt equilibrium.

- The role of the price mechanism

- Market efficiency

2 Elasticity

- Price elasticity of demand (PED)

- Cross price elasticity of demand (XED)

- Income elasticity of demand (YED)

- Price elasticity of supply (PES)

3 Government intervention

- Indirect taxes

- Price controls

4 Market failure

- The meaning of market failure

- Types of market failure

11 Supply-side policies

- The role of supply-side policies

- Interventionist supply-side policies

- Market-based supply-side policies

- Evaluation of supply-side policies

Equilibrium and changes to equilibrium

Market equilibrium : is where the supply equals to the demand.

Figure 1.5 - Market equilibrium

Calculating and illustrating equilibrium using linear equations

The market is in equilibrium at Pe, when the amount of that product consumers wish to buy, Qe, is equal to the amount of coffee producer wish to sell.

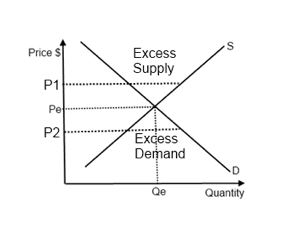

Figure 1.6 - Excess in supply and demand at different price levels

- Excess supply: More is being supplied than demanded at P1 → in order to eliminate the surplus, producer must lower the price

- Excess demand: More is being demanded than supplied at P2 → in order to eliminate this shortage, producer must raise the price

Changes in determinants cause changes in equilibrium

- When there’s a change in determinants of demand/supply other than the price of the product, it would lead to a shift of a curve.

- When Demand shifts to D1, Qe is the quantity supplied, but Q2 is the quantity demanded, there is excess demand (of xxx units).

- Due to price mechanism (see below), the price will rise until Pe1, where the new equilibrium quantity, is both demanded and supplied.

IBDP Economics

Website by Mark Johnson & Alex Smith

Updated 4 June 2024

InThinking Subject Sites

Subscription websites for IB teachers & their classes

Find out more

- thinkib.net

- IBDP Biology

- IBDP Business Management

- IBDP Chemistry

- IBDP English A Literature

- IBDP English A: Language & Literature

- IBDP English B

- IBDP Environmental Systems & Societies

- IBDP French B

- IBDP Geography

- IBDP German A: Language & Literature

- IBDP History

- IBDP Maths: Analysis & Approaches

- IBDP Maths: Applications & Interpretation

- IBDP Physics

- IBDP Psychology

- IBDP Spanish A

- IBDP Spanish Ab Initio

- IBDP Spanish B

- IBDP Visual Arts

- IBMYP English Language & Literature

- IBMYP Resources

- IBMYP Spanish Language Acquisition

- IB Career-related Programme

- IB School Leadership

Disclaimer : InThinking subject sites are neither endorsed by nor connected with the International Baccalaureate Organisation.

InThinking Subject Sites for IB Teachers and their Classes

Supporting ib educators.

- Comprehensive help & advice on teaching the IB diploma.

- Written by experts with vast subject knowledge.

- Innovative ideas on ATL & pedagogy.

- Detailed guidance on all aspects of assessment.

Developing great materials

- More than 14 million words across 24 sites.

- Masses of ready-to-go resources for the classroom.

- Dynamic links to current affairs & real world issues.

- Updates every week 52 weeks a year.

Integrating student access

- Give your students direct access to relevant site pages.

- Single student login for all of your school’s subscriptions.

- Create reading, writing, discussion, and quiz tasks.

- Monitor student progress & collate in online gradebook.

Meeting schools' needs

- Global reach with more than 200,000 users worldwide.

- Use our materials to create compelling unit plans.

- Save time & effort which you can reinvest elsewhere.

- Consistently good feedback from subscribers.

For information about pricing, click here

Download brochure

See what users are saying about our Subject Sites:

Find out more about our Student Access feature:

- Unit 2.3: Competitive market equilibrium

- Chapter 2: Microeconomics

Equilibrium in markets occurs where demand equals supply and the market-clearing price and output are established. The equilibrium price is known as the market-clearing price because at that moment in time all the consumers who are willing and able to buy the product at the equilibrium price can purchase the good and all the producers who are willing and able to sell the product at the equilibrium price can sell it....

To access the entire contents of this site, you need to log in or subscribe to it.

Alternatively, you can request a one month free trial .

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Marketing

Market Equilibrium Essay

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Marketing , Market , Demand , Equals , Equilibrium Point , Function , Excess , Curve

Published: 03/19/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Equilibrium in the market is attained when the quantity offered by the suppliers equals the quantity demanded by the buyers. We define equilibrium as the price at which quantity demanded equals quantity supplied. Graphically, this is the point of intersection of the demand and the supply curve. This is shown in the figure below. P S P1

Q1d Q0 Q1s Q2d Q

In the above figure the demand and the supply curve intersects at the point E. This is the equilibrium point. The equilibrium price is P0 and the equilibrium quantity is Q0. At a price higher than this market clearing price P0 the quantity supplied is higher than the quantity demanded. An excess supply condition arises. We can see this at price P1 the quantity supplied Q1s is higher than the quantity demanded Q1d. So the price falls. At a price lower than P0, say P2, the quantity demanded Q2d is higher than the quantity supplied. So, there is an excess demand situation, The price goes up until it reaches the equilibrium point.

The equilibrium point can also be derived mathematically. Suppose the demand function is given as:

Qd = 20 – 3P

The supply function is given as:

Qs = 5 + 2P

We can obtain the equilibrium price by equating Qd with Qs:

20 – 3P = 5 + 2P Or, 5P = 15 Or P = 3 At price 3 units, the demand equals supply. This is the equilibrium price. We can obtain the equilibrium quantity by substituting the value of P in the demand or the supply equation: Qd =20 -3P = 20 – 3*3 = 20 – 9 = 11units. Thus the equilibrium price is 3 units and the equilibrium quantity is 11 units.

Works Cited

Koutsoyiannis, A. (2003). Microeconomics. Pulgrave Macmillan.

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 1939

This paper is created by writer with

ID 265884910

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Global financial crisis research papers, urban planning research papers, tennessee williams research papers, genetic engineering research papers, globe case studies, magazine case studies, attraction case studies, slave case studies, excess case studies, panic case studies, republic case studies, street case studies, termination book reviews, richard polenberg war and society the united states 1941 1945 book review, film studies movie review, nationstate and transnationalism course work, essay on early childhood, pirandello essay, case study on examination of qantas etoms restructuring, the state of unemployment in colombia course work, using budgets case study, social conflict theories of the family course work, research paper on social security, gender and job satisfaction case study examples, example of hitler s reign in germany and his hatred of jews research paper, solving the healthcare crisis critical thinking examples, war and state building process research paper example, buffet s berkshire battle case study examples, children s functional health pattern assessment essay examples, avatar essays, earth science essays, job search essays, django unchained essays, attachment theory essays, divergent essays, gay adoption essays, easter island essays, easter essays, growth mindset essays, siddhartha essays, kobe bryant essays, pes cavus essays, particularity essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Supply and Demand and Market Equilibrium Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

In the New York Times article titled ‘How the supply chain broke and why it won’t be fixed anytime soon’, Peter Goodman analyses the scarcity of basic commodities such as computer chips, exercise equipment and breakfast cereals, among others. The author talks about the current era of coronavirus pandemic that has disrupted the global chain to the extent of compromising the color of cars and delaying airplanes and crews waiting for food deliveries. From the author’s point of view, the demand has gone higher than the supply, as shown in Figure 1 below. The manufacturing capacity has found a challenge in the distribution of the products due to the transportation and logistics of the goods, probing the price of many commodities to go higher than before (Goodman, 2021). The determinant of supply, in this case, is production factories and shipping companies that have experienced a profound shortage of production units and freight containers, respectively, as Goodman (2021) suggests. The determinant of demand is the consumer who waits for the finished product from the factories.

When the consumer pays, and there is a delay or no delivery, the demand in the market grows, which means any existing product in the region will witness hiked prices. Where demand is high, and supplies are low, the demand curve shifts rightward while the supply curve goes towards left (Kiseleva, 2021). As a result of increased demand, there is an increase in equilibrium price where the effect on quantity is not determinable due to the existing uncertainty.

The production possibilities curve (PPC) will indicate a point outside the curve showing the likelihood of producing more goods due to the challenge of supplying them. With time, the curve may show that the resources are not being used, a redundancy that may happen to production companies in covid-hit countries in the world. The US is currently operating at point A in PPC since there has been a gradual reopening of pathways to transport goods in various parts of the world (Kiseleva, 2021). From the article, it is clear that coronavirus is a dragging force that has led to low supply and high demand due to restrictions in distribution of goods across many countries. The price of sensitive commodities may remain high until there is a global curl for the current pandemic.

Goodman, P. (2021). How the supply chain broke, and why it won’t be fixed anytime soon . Nytimes.com .

Kiseleva, I. (2021). Simulations of supply and demand forecasting in a market economy. Journal of Economic Affairs. 11 (4), 1669-1684. Web.

- Demand for the Products of the Psychiatric and Pharmaceutical Industry

- The Supply and Demand Simulation

- Reality of Achilles in “The Iliad”

- Regulation and Deregulation in Transportation

- Logistics Management: Assignment

- A Supply Chain for the Big Mac

- Maaza Mango Drink's Supply Chain

- Sustainable Supply Chain Management Principles

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, May 22). Supply and Demand and Market Equilibrium. https://ivypanda.com/essays/supply-and-demand-and-market-equilibrium/

"Supply and Demand and Market Equilibrium." IvyPanda , 22 May 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/supply-and-demand-and-market-equilibrium/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Supply and Demand and Market Equilibrium'. 22 May.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Supply and Demand and Market Equilibrium." May 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/supply-and-demand-and-market-equilibrium/.

1. IvyPanda . "Supply and Demand and Market Equilibrium." May 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/supply-and-demand-and-market-equilibrium/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Supply and Demand and Market Equilibrium." May 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/supply-and-demand-and-market-equilibrium/.

Efficiency and Market Equilibrium

Checked : Luis G. , Vallary O.

Latest Update 21 Jan, 2024

12 min read

Table of content

Describing efficiency

Economic efficiency, market efficiency, operational efficiency, why is efficiency important, market equilibrium.

In life, we all want to get the best from everything we do without having the spend too much. Both consumers and producers expect the market to be perfect so that demand and supply are all at the same level. This way, consumers will get enough goods while producers will make enough profit to incentivize the production of more goods and services. When the economy is good, it means everyone is happy, and every process has been perfectly measured and achieved. But then, economic cycles do not let the markets hit perfection, and both consumers and producers have to find a way to coexist.

There are two aspects of economic development that makes everything count. One is efficiency, and the other is equilibrium. In life, we are always faced by different situations that force us to make decisions. And there is no way anyone will live without having to make these decisions. There are many factors that influence these decisions, among the scarcity and budget constraints. According to consumer and producer theories, individuals and firms make decisions based on the best outcome. In other words, they are loss aversive, avoiding anything that seems to cause a loss for them.

And this is where efficiency and equilibrium. When companies want to introduce a new product on the market, they look at existing data to see whether or not consumers will like the product. Data is one of the most critical aspects of understanding and using economic theory. For instance, statistical information about a different company that has launched the same product in the past can help the firm decide on the best ways to succeed where others have failed. On the other hand, consumers use information like price and brand awareness of their buying decisions. But most importantly, they look at their budget and choose the decision of the most appropriate method. Take, for instance, a family that has been saving for a long time, and now they are held between the decision of buying a car or going on a dream vacation. It all comes down to the importance of consumer goods vs. luxury in their lives—the income of the decision-maker determines the utilization of either product.

Both firms and consumers require to make the right judgments and way carefully the outcome of their actions. Such decisions are better discarded if it leads to the harm of themselves or other people around them. It does not make sense for anyone to make a decision that causes a loss for them. It is like humanity to coexist and affect each other in everything they do. A single’ individual’s indecision to buy or not to buy a product will not majorly affect a company, but when a large group of people is involved, things may get worse or better for the markets. When one producer decides to raise the price of commodities, it may not have any major impact on the consumer as they can simply choose to go for another producer.

When looking at efficiency and equilibrium, we need to understand these factors because they are important in microeconomic theory. For instance, the mathematical approach to microeconomics demands the presentation of statistical data. If there is no data, then there is no mathematics because the subject deals widely with numbers and figures.

Now that we have laid the background for these subjects, we can get into their description and see their importance in economic processes. Efficiency means the highest level of performance whereby the involved party uses the least amount of inputs to achieve that highest output. It can be compared to the peak of an economic bubble, and that in this case, resources are directly involved. For efficiency to be counted, there must be a reduction in the number of unnecessary resources when producing a given output, and it may include personal time and energy. Efficiency is a measurable concept that be derived from the application of the ration of important output to total output. The main idea of efficiency is to minimize the wastage of resources and maximize profits. Things like physical material, energy, and time are cut down while ensuring the desired output is achieved. Efficiency is important because it helps both consumers and producers are benefiting from economic processes. When one buys a product, they put it to maximum use without risking loss. But it is within the company setting that we get to understand the real meaning of efficiency?

Generally, something is efficient when nothing goes to waste, and all the processes are fully optimized. In the fields of finance and economics, efficiency is very important because it used in a number of ways to get the most out of the process. It is critical for one to discern different terms used in efficiency. Consider the following:

This is efficiency in terms of individual decisions and processes. It is a form of optimization of resources to serve the best interests of an individual within an economic state. There are no set threshold determinants for the effectiveness of an economy. There is no telling how much a certain economy will succeed through economic cycles. However, the indicators of economic efficiency include products bought in to the market at the lowest cost and labor that offers the best possible outcome.

Markets, too, have their share of economic ups are down. When a certain company makes decisions on a large scale, they generally affect what happens within that economy. And since firms make up markets, their decisions are essential in the growth of these markets. Market efficiency explains how well prices integrate available information. Hence, markets are considered to be efficient when all data and information are already included in the prices, meaning it is impossible to ‘beat’ the market as there is not any less valued securities are any that are overvalued within markets. Everything is said to be at the equilibrium with the market setting, with prices all at the same level. Economist Eugene Fama (1970) described market efficiency, where his efficient market hypothesis (EMH), says the investor cannot outperform the market, and market anomalies should not be there because they will be arbitraged with immediate effect.

This is the type of efficiency that measures how good profits are gained as a function of operating costs. Great efficiency means more profit for the firm, and vice versa. Companies need to make maximum profits through their operations, and they can do this by reducing costs. This happens especially because the entity can make more income or profits than if it used an alternative method. Operational efficiency is more critical and profound in financial markets , where it occurs with the reduction in transaction costs and fees.

There has been so much development in economic efficiency over the years. It has always existed coincidently with the invention of new tools that improve labor. These processes can be traced back to the ages of the wheel and horse-collar – the hoarse collar redistributes the weight on the back of a horse, helping the animal to carry more without feeling overburdened. The steam engines and motor vehicles came up during the industrial revolution, which allowed people to move further and faster, thus contributing to travel and trade efficiencies. More of these efficiencies were achieved during the Industrial Revolution, where the discovery of new power sources such as fossil fuels made processes cheaper, more effective, and versatile.

Even better, the Industrial Revolution and other movements that came after it brought efficiencies in time. For instance, the factory system introduced production lines where one participant focused on one area of specialization, which brought about an increase in production while saving time. At this time, many scientists came up and developed practices that would optimize specific task performance.

If a society is efficient, it will be able to serve its dweller and function in the best way possible. Economies need to have efficient processes so that the goods produced are sold at a lower price, enabling local consumers to enjoy better living standards. It is all about giving people a better life and ensuring the everyone withing an economy is having the best time of their lives. When people are supplied with electricity in their homes, running water in their taps, and they can travel easily, nothing will stop them from living their lives to the fullest. Efficiency brings down hunger levels as well as unemployment rates within a society. Advances in efficiency allow for greater productivity within a shorter amount of time, and use lesser resources, saving much for the future.

As we already know, all inputs are scarce. Human demands are unlimited and cannot be quenched by limited resources, which leads to great levels of scarcity. Time, money, and raw material do not exist in maximum fulness, and it is vital to conserve them while ensuring acceptable levels of output.

When it comes to understanding economics, one must be ready to learn and fully understand the concept of market equilibrium. This concept helps firms and individuals to make informed decisions whenever they are confronted by the need to do so – which happens at every turn. Markets are described as imperfect because there is no day production and supply will be on the same level. A perf market is where all factors are in perfect supply, including market information and data. But this only happens in theory.

However, this does not mean that firms and firms cannot achieve a state of equilibrium. There are certain situations that can be termed as good for the market. Equilibrium is a state where the supply within markets is equal to the demand. In this case, the equilibrium price is the price of a product when demand and supply are at the same level. Price does not change in an equal market unless other factors like demand and supply are changed, in which case it leads to the disruption of the equilibrium.

When markets fail to reach an equilibrium, forces with it tend to move towards the equilibrium line. This means, if the market price is above the equilibrium line, it means there is excess supply within the market – supply is higher than demand, an effect that leads to a surplus. Companies may not be able to clear inventories unless they apply specific strategies like reducing the price of their goods. Some situations may force them to slow down their production or cease ordering inventory. As long as price keeping reducing, people will keep buying, and it may continue so until supply is further reduced. While supply reducing, demand, on the other hand, will be increasing.

We Will Write an Essay for You Quickly

In a situation where the market price is below the equilibrium, it means demand is in plenty and supply in shortage. This case compels buyers to bid up the price of goods and serves so that they can get them. As prices increase, buyers will quit trying, not because they don’t want to, but because of the scarcity of cash and budget constraints. Apart from this, sellers will be excited to see a surge in demand and want to produce more of the product. This condition may continue until the upward pressure on prices and supply stabilize – a market equilibrium.

Determining market equilibrium is one of the best ways to understand economic prices. Fortunately, it is very easy as long as you have the required sets of data. Let’s say, for instance, you are and economist working with a Global Economy Agency, and you are tasked to study the market of peaches in Congo, a developing economy. You have received transaction data for this factor from the past two years, which shows the government has incentivized farmers to grow more Peaches, and now they are seeking to attract international investors. You can allow your team to create a Supply and Demand Equation where:

P is the price per container of the product.

Supply X = 300 + 3p

Demand X = 1,800 – 2p

You can use this information to fine Q by balancing them.

300 + 3p = 1800 – 2p

Hence, 300 + 3p + 2p = 1800

Working further, we get 300 + 5p = 1,800, and then 5p = 1800 – 300

Therefore, 5p = 1,200

Let’s say P = $300, then

Supply Q = 300 + 3 x 300 = 1200.

Hence, you have the equilibrium point as 1,200 containers selling at $300.

Looking for a Skilled Essay Writer?

- Montana Tech University Master of Science (MS),

No reviews yet, be the first to write your comment

Write your review

Thanks for review.

It will be published after moderation

Latest News

What happens in the brain when learning?

10 min read

20 Jan, 2024

How Relativism Promotes Pluralism and Tolerance

Everything you need to know about short-term memory

Navigation menu

Help | Advanced Search

Quantitative Finance > Mathematical Finance

Title: mean field equilibrium asset pricing model with habit formation.

Abstract: This paper presents an asset pricing model in an incomplete market involving a large number of heterogeneous agents based on the mean field game theory. In the model, we incorporate habit formation in consumption preferences, which has been widely used to explain various phenomena in financial economics. In order to characterize the market-clearing equilibrium, we derive a quadratic-growth mean field backward stochastic differential equation (BSDE) and study its well-posedness and asymptotic behavior in the large population limit. Additionally, we introduce an exponential quadratic Gaussian reformulation of the asset pricing model, in which the solution is obtained in a semi-analytic form.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

Subscribe to the PwC Newsletter

Join the community, edit social preview.

Add a new code entry for this paper

Remove a code repository from this paper, mark the official implementation from paper authors, add a new evaluation result row, remove a task, add a method, remove a method, edit datasets, generalized bayesian nash equilibrium with continuous type and action spaces.

30 May 2024 · Yuan Tao , Huifu Xu · Edit social preview

Bayesian game is a strategic decision-making model where each player's type parameter characterizing its own objective is private information: each player knows its own type but not its rivals' types, and Bayesian Nash equilibrium (BNE) is an outcome of this game where each player makes a strategic optimal decision according to its own type under the Nash conjecture. In this paper, we advance the literature by considering a generalized Bayesian game where each player's action space depends on its own type parameter and the rivals' actions. This reflects the fact that in practical applications, a firm's feasible action is often related to its own type (e.g. marginal cost) and the rivals' actions (e.g. common resource constraints in a competitive market). Under some moderate conditions, we demonstrate existence of continuous generalized Bayesian Nash equilibria (GBNE) and uniqueness of such an equilibrium when each player's action space is only dependent on its type. In the case that each player's action space is also dependent on rivals' actions, we give a simple example to show that uniqueness of GBNE is not guaranteed under standard monotone conditions. To compute an approximate GBNE, we restrict each player's response function to the space of polynomial functions of its type parameter and consequently convert the GBNE problem to a stochastic generalized Nash equilibrium problem (SGNE). To justify the approximation, we discuss convergence of the approximation scheme. Some preliminary numerical test results show that the approximation scheme works well.

Current Time In Tomsk, Tomsk Oblast, Russia

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

5 December 2019 by Tejvan Pettinger. Definition of market equilibrium - A situation where for a particular good supply = demand. When the market is in equilibrium, there is no tendency for prices to change. We say the market-clearing price has been achieved. A market occurs where buyers and sellers meet to exchange money for goods.

Demand, Supply and Market Equilibrium Essay. Demand is the quantity of products customers are willing to buy at a particular price while supply is the quantity of products firms are willing to offer for sell. There is an inverse relationship between demand and supply when all other factors remain constant. On the other hand, market equilibrium ...

The equilibrium is the only price where quantity demanded is equal to quantity supplied. At a price above equilibrium, like 1.8 dollars, quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded, so there is excess supply. At a price below equilibrium, such as 1.2 dollars, quantity demanded exceeds quantity supplied, so there is excess demand.

Market Equilibrium refers to a business phenomenon where buyers bid against one another in an attempt to realize the selling price for the product. Therefore, it is to the discretion of the sellers to offer higher or accept lower prices for their commodities. We will write a custom essay on your topic. 812 writers online.

in a market setting, disequilibrium occurs when quantity supplied is not equal to the quantity demanded; when a market is experiencing a disequilibrium, there will be either a shortage or a surplus. equilibrium price. the price in a market at which the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied of a good are equal to one another; this is also ...

Supply and demand are the most basic concepts of economics. Demand is the quantity of goods desired by consumers while supply is the amount of goods the producers can offer to the market (Begg & Dornbusch, 2005). We will write a custom essay on your topic. Quality demanded is the amount of goods consumers are willing to buy at a certain price ...

Changes in equilibrium price and quantity when supply and demand change. Changes in equilibrium price and quantity: the four-step process. Economists define a market as any interaction between a buyer and a seller. How do economists study markets, and how is a market influenced by changes to the supply of goods that are available, or to changes ...

Market equilibrium is the point where the quantity supplied by producers and the quantity demanded by consumers are equal. When we put the demand and supply curves together, we can determine the equilibrium price: the price at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. In figure 10.1, the equilibrium price is shown as P ∗ P ∗ ...

However, if a market is not at equilibrium, then economic pressures arise to move the market toward the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity. Imagine, for example, that the price of a gallon of gasoline was above the equilibrium price—that is, instead of $1.40 per gallon, the price is $1.80 per gallon.

The market is in equilibrium at Pe, when the amount of that product consumers wish to buy, Qe, is equal to the amount of coffee producer wish to sell. Figure 1.6 - Excess in supply and demand at different price levels. When there's a change in determinants of demand/supply other than the price of the product, it would lead to a shift of a curve.

Chapter 2: Microeconomics. Unit 2.3: Competitive market equilibrium. Equilibrium in markets occurs where demand equals supply and the market-clearing price and output are established. The equilibrium price is known as the market-clearing price because at that moment in time all the consumers who are willing and able to buy the product at the ...

Equilibrium in the Market Essay. Good Essays. 1210 Words. 5 Pages. Open Document. As with all markets and their respective economies, having equilibrium is one of the key factors of a successful system. Although most markets do not reach equilibrium, they attempt at getting close. There are numerous methods devised to reach equilibrium, whether ...

Market Equilibrium Individual market equilibration process The laws of supply and demand as they relate to market equilibrium are manifested every Christmas, when children's toys are bought and sold. Quite often there is a hot toy that all children suddenly seem to want. Suppliers cannot manufacture enough toys to suit the demand of parents.

Words: 300. Published: 03/19/2020. Equilibrium in the market is attained when the quantity offered by the suppliers equals the quantity demanded by the buyers. We define equilibrium as the price at which quantity demanded equals quantity supplied. Graphically, this is the point of intersection of the demand and the supply curve.