- Technical support

- Katie Terrell Hanna

What is K-12?

K-12, a term used in education and educational technology in the United States, Canada and some other countries, is a short form for the publicly supported school grades prior to college.

These grades are kindergarten (K) and first through 12th grade (1-12). (If the term were used, 13th grade would be the first year of college.)

What are the different levels of K-12?

K-12 schools are usually divided into three levels:

- elementary school (grades K-5);

- middle school or junior high school (grades 6-8); and

- high school (grades 9-12).

In some instances, these three groups are kept separate; in others, elementary and middle school are grouped together, but high school is kept separate. In other cases, all levels are held together on the same campus.

What are the benefits of K-12 education?

K-12 education is the foundation of a student's academic career. It provides the basic knowledge and skills necessary for success in college and the workplace .

K-12 education also plays an important role in developing responsible citizens and preparing young people for the challenges of adulthood.

Benefits of a K-12 education include the following:

- academic preparation for college and the workforce;

- social and emotional development;

- exposure to different cultures and perspectives; and

- opportunities for physical activity and extracurricular involvement.

Is K-12 private or publicly funded?

K-12 education is free in the U.S., with most schools being public (state-funded) schools, and is mandatory in the U.S. until age 16 or 18, depending on the state.

However, there are also a number of private K-12 schools, which are supported by tuition payments and other private sources of funding.

What subjects are studied in K-12?

K-12 education covers a wide range of topics, including the following:

- language arts (reading, writing and comprehension);

- mathematics ;

- social studies;

- physical education; and

- foreign languages.

What types of assignments are given to K-12 students?

Assignments at the K-12 level can vary greatly, depending on the age and level of the students.

They can range from simple tasks, such as math problems or reading comprehension exercises, to more complex projects, such as research papers or presentations.

In general, assignments are designed to assess a student's understanding of the material covered in class and their ability to apply it to real-world situations.

What types of assessments are given in K-12?

Like assignments, assessments at the K-12 level can vary greatly. They can be formal, such as standardized tests, or informal, such as class participation or homework completion.

Assessments are typically used to measure a student's progress over time and to identify areas in which they may need additional support.

How do you get enrolled in K-12?

Enrollment in K-12 schools is typically done through the school district in which a family lives.

If they are moving to a new area, they may need to contact the school district office to find out what the enrollment process is. In some cases, they may be able to enroll their child in a K-12 school online.

Are there any alternatives to K-12 education?

There are a number of alternatives to K-12 education, including the following:

- home schooling

- private schools

- charter schools

- online schools

Each of these options has its own advantages and disadvantages, so it is important to do your research before making a decision.

Continue Reading About K-12

- K-12 market: Channel takes on networking, storage, security projects

- RingCentral unveils UCaaS offerings for education

- FBI, CISA warn of growing ransomware attacks on K-12 schools

- Surge in ransomware attacks threatens student data

- Education technology market seeks stability in hybrid model

Related Terms

NBASE-T Ethernet is an IEEE standard and Ethernet-signaling technology that enables existing twisted-pair copper cabling to ...

SD-WAN security refers to the practices, protocols and technologies protecting data and resources transmitted across ...

Net neutrality is the concept of an open, equal internet for everyone, regardless of content consumed or the device, application ...

A proof of concept (PoC) exploit is a nonharmful attack against a computer or network. PoC exploits are not meant to cause harm, ...

A virtual firewall is a firewall device or service that provides network traffic filtering and monitoring for virtual machines (...

Cloud penetration testing is a tactic an organization uses to assess its cloud security effectiveness by attempting to evade its ...

Regulation SCI (Regulation Systems Compliance and Integrity) is a set of rules adopted by the U.S. Securities and Exchange ...

Strategic management is the ongoing planning, monitoring, analysis and assessment of all necessities an organization needs to ...

IT budget is the amount of money spent on an organization's information technology systems and services. It includes compensation...

ADP Mobile Solutions is a self-service mobile app that enables employees to access work records such as pay, schedules, timecards...

Director of employee engagement is one of the job titles for a human resources (HR) manager who is responsible for an ...

Digital HR is the digital transformation of HR services and processes through the use of social, mobile, analytics and cloud (...

A virtual agent -- sometimes called an intelligent virtual agent (IVA) -- is a software program or cloud service that uses ...

A chatbot is a software or computer program that simulates human conversation or "chatter" through text or voice interactions.

Martech (marketing technology) refers to the integration of software tools, platforms, and applications designed to streamline ...

- Society ›

Education & Science

K-12 education in the United States - statistics and facts

Public school politics, inequalities in education, key insights.

Detailed statistics

School enrollment in public and private institutions in the U.S. 2022

Expenditure on public and private elementary and secondary schools U.S. 1970-2021

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Educational Institutions & Market

Share of Americans who are concerned about select issues in public schools U.S. 2023

Top three reasons K-12 public school teachers fear for their safety U.S. 2023

U.S. states restricting schools from teaching race, sex, or inequality 2021-2023

Further recommended statistics

- Basic Statistic Number of elementary and secondary schools in the U.S. 2020/21, by type

- Premium Statistic Share of U.S. public schools 2021/22, by enrollment size and school type

- Basic Statistic School enrollment in public and private institutions in the U.S. 2022

- Basic Statistic Enrollment in public and private elementary schools 1960-2022

- Basic Statistic High school enrollment in public and private institutions U.S. 1965-2031

- Premium Statistic Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools U.S. 2022, by state

- Basic Statistic Primary and secondary school enrollment rates in the U.S. in 2022, by age group

- Basic Statistic Share of students enrolled in U.S. public K-12 schools 2021, by ethnicity and state

- Basic Statistic U.S. public school enrollment numbers 2000-2021, by ethnicity

Number of elementary and secondary schools in the U.S. 2020/21, by type

Number of elementary and secondary schools in the United States in 2020/21, by school type*

Share of U.S. public schools 2021/22, by enrollment size and school type

Share of public schools in the United States in 2021/22, by enrollment size and school type

Enrollment in public and private schools in the United States in 2022 (in millions)

Enrollment in public and private elementary schools 1960-2022

Enrollment in public and private elementary schools in the United States from 1960 to 2022 (in millions)

High school enrollment in public and private institutions U.S. 1965-2031

High school enrollment for public and private schools in the U.S. from 1965 to 2020, with projections up to 2031 (in 1,000s)

Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools U.S. 2022, by state

Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools in the United States in 2022, by state (in 1,000s)

Primary and secondary school enrollment rates in the U.S. in 2022, by age group

Share of population enrolled in primary and secondary education in the United States in 2022, by age group

Share of students enrolled in U.S. public K-12 schools 2021, by ethnicity and state

Share of students enrolled in K-12 public schools in the United States in 2021, by ethnicity and state

U.S. public school enrollment numbers 2000-2021, by ethnicity

K-12 public school enrollment numbers in the United States from 2000 to 2021 by ethnicity (in 1,000s)

Revenue and expenditure

- Basic Statistic School expenditure on public and private institutions 1970-2020

- Basic Statistic Expenditure on public and private elementary and secondary schools U.S. 1970-2021

- Premium Statistic U.S. per pupil public school expenditure FY 2023, by state

- Basic Statistic U.S. public schools - average expenditure per pupil 1980-2020

- Basic Statistic U.S. education - total expenditure per pupil in public schools 1990-2021

- Basic Statistic Revenue of public elementary and secondary schools U.S. 1980-2020

- Premium Statistic Average annual tuition for private K-12 schools U.S. 2024, by state

- Premium Statistic Estimated average salary of public school teachers U.S. 2021/22, by state

School expenditure on public and private institutions 1970-2020

School expenditure in public and private institutions in the United States from 1970 to 2020 (in billion U.S. dollars)

School expenditure on public and private elementary and secondary schools in the United States from 1970 to 2021 (in billion U.S. dollars)

U.S. per pupil public school expenditure FY 2023, by state

Per pupil public elementary and secondary school expenditure in the United States in the fiscal year of 2023, by state (in U.S. dollars)

U.S. public schools - average expenditure per pupil 1980-2020

Average expenditure per pupil in average daily attendance in public elementary and secondary schools from academic years 1980 to 2020 (in U.S. dollars)

U.S. education - total expenditure per pupil in public schools 1990-2021

Total expenditure per pupil in public elementary and secondary schools in the United States from 1990 to 2021 (in constant 2022-23 U.S. dollars)

Revenue of public elementary and secondary schools U.S. 1980-2020

Revenue of public elementary and secondary schools in the United States from the academic years 1980 to 2020 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Average annual tuition for private K-12 schools U.S. 2024, by state

Average annual tuition for private K-12 schools in the United States in 2024, by state (in U.S. dollars)

Estimated average salary of public school teachers U.S. 2021/22, by state

Estimated average salary of public school teachers in the United States in 2021-2022, by state (in constant 2020-21 U.S. dollars)

State laws and book bans

- Premium Statistic U.S. states restricting schools from teaching race, sex, or inequality 2021-2023

- Premium Statistic Proposed bans on sex or gender identity in K-12 schools U.S. 2023, by grade level

- Premium Statistic Share of transgender youth subject to bans on school sport participation U.S 2024

- Premium Statistic Share of U.S. transgender population subject to bathroom bills 2024

- Premium Statistic Instances of book bans in U.S. public schools 2022/23, by ban status

- Basic Statistic Books banned in schools in the U.S. H2 2022, by state

- Premium Statistic Book titles banned in schools in the U.S. H2 2022, by subject matter

- Premium Statistic Topics that K-12 librarians would ban from their school libraries U.S. 2023

Legal action taken to restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism, sexism, and systemic inequality in the United States from 2021 to 2023, by state

Proposed bans on sex or gender identity in K-12 schools U.S. 2023, by grade level

Number of proposed bans on instruction related to sexual orientation or gender identity in K-12 schools in the United States in 2023*, by grade level of ban

Share of transgender youth subject to bans on school sport participation U.S 2024

Share of transgender youth aged 13 to 17 living in states that restrict transgender students from participating in sports consistent with their gender identity in the United States as of March 14, 2024

Share of U.S. transgender population subject to bathroom bills 2024

Share of transgender population aged 13 and over living in states that ban transgender people from using bathrooms and facilities consistent with their gender identity in the United States as of March 14, 2024

Instances of book bans in U.S. public schools 2022/23, by ban status

Total number of instances of books banned from K-12 public libraries and classrooms in the United States in the 2022/23 school year, by ban status

Books banned in schools in the U.S. H2 2022, by state

Number of books banned in school classrooms and libraries in the United States from July 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022, by state

Book titles banned in schools in the U.S. H2 2022, by subject matter

Share of book titles banned in school classrooms and libraries in the United States from July 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022, by subject matter

Topics that K-12 librarians would ban from their school libraries U.S. 2023

Share of library staff working in K-12 schools and districts who believe that libraries in their district or school should not include any books that depict certain topics in the United States in 2023

- Premium Statistic Share of K-12 public students attending predominately same-race schools U.S 2021

- Premium Statistic Share of public schools who feel understaffed U.S. 2024, by students of color

- Premium Statistic Estimated average months of learning lost due to COVID-19 by ethnicity U.S. 2020

- Premium Statistic NAEP reading scores for nine year olds U.S. 2022, by race

- Premium Statistic NAEP math scores for nine year olds U.S. 2022, by race

- Premium Statistic Share of K-12 students who feel their school respects who they are U.S. 2023, by race

- Premium Statistic Schools in the U.S.: victims of threats/injuries by weapons, by ethnicity 2021

- Premium Statistic Share of students who have experienced school shootings U.S. 1999-2024, by race

- Basic Statistic Share of teachers afraid of school shootings U.S. 2022, by location and student race

Share of K-12 public students attending predominately same-race schools U.S 2021

Share of students attending K-12 public schools in which 75 percent or more of the students are of their own race or ethnicity in the United States in the 2020-21 school year

Share of public schools who feel understaffed U.S. 2024, by students of color

Share of public schools who feel that their school is understaffed in the United States entering the 2023-24 school year, by students of color

Estimated average months of learning lost due to COVID-19 by ethnicity U.S. 2020

Estimated average months of learning lost compared with in-classroom learning due to COVID-19 in the United States in 2020, by ethnicity

NAEP reading scores for nine year olds U.S. 2022, by race

Reading scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress for nine year old students in the United States from 2020 to 2022, by race

NAEP math scores for nine year olds U.S. 2022, by race

Mathematics scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress for nine year old students in the United States from 2020 to 2022, by race

Share of K-12 students who feel their school respects who they are U.S. 2023, by race

Share of K-12 students who feel that their school respects who they are, regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, or identity in the United States in 2023, by race

Schools in the U.S.: victims of threats/injuries by weapons, by ethnicity 2021

Percentage of U.S. students in grades 9–12 who reported being threatened or injured with a weapon at school in 2021, by ethnicity

Share of students who have experienced school shootings U.S. 1999-2024, by race

Share of students who have experienced school shootings in the United States from 1999 to 2024*, by race

Share of teachers afraid of school shootings U.S. 2022, by location and student race

Share of K-12 teachers who reported feeling afraid that they or their students would be a victim of attack or harm at school in the United States in 2022, by school locale and student racial composition

K-12 teachers

- Basic Statistic Teachers in elementary and secondary schools U.S. 1955-2031

- Basic Statistic U.S. elementary and secondary schools: pupil-teacher ratio 1955-2031

- Premium Statistic Impacts of restricting race, sex, and identity topics for K-12 teachers U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic Share of public K-12 teachers who limit political or social topics in class U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic Top reasons K-12 public school teachers limit political or social topics U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic K-12 teachers' views on how gender identity should be taught at school U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic K-12 teachers' support for parents to opt children out of race/gender topics U.S 2023

- Premium Statistic Top three reasons K-12 public school teachers fear for their safety U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic Share of school staff who received concerns from parents on K-12 curriculum 2023

Teachers in elementary and secondary schools U.S. 1955-2031

Number of teachers in public and private elementary and secondary schools in the United States from 1955 to 2031 (in 1,000s)

U.S. elementary and secondary schools: pupil-teacher ratio 1955-2031

Pupil-teacher ratio in public and private elementary and secondary schools in the United States from 1955 to 2031

Impacts of restricting race, sex, and identity topics for K-12 teachers U.S. 2023

Share of public K-12 teachers who say that current debates on how public K-12 schools should be teaching certain topics like race and gender identity has impacted their ability to do their job in the United States in 2023

Share of public K-12 teachers who limit political or social topics in class U.S. 2023

Have you ever decided on your own, without being directed by school or district leaders, to limit discussion of political and social issues in class?

Top reasons K-12 public school teachers limit political or social topics U.S. 2023

What are the top three reasons you decided, on your own, to limit discussion of political and social topics in your classroom?

K-12 teachers' views on how gender identity should be taught at school U.S. 2023

Share of public K-12 teachers with various beliefs on what students should learn about gender identity at school in the United States in 2023, by grade level

K-12 teachers' support for parents to opt children out of race/gender topics U.S 2023

Share of public K-12 teachers who believe parents should be able to opt their children out of learning about racism and racial inequality or sexual orientation and gender identity if the way they are taught conflicts with the parents' personal beliefs in the United States in 2023, by party

What are the top three reasons you fear for your physical safety when you are at school?

Share of school staff who received concerns from parents on K-12 curriculum 2023

About which topics have parents expressed concerns to you?

Parent perceptions

- Premium Statistic Main reasons why parents enroll their children in private or public schools U.S. 2024

- Premium Statistic Share of Americans with various views on what school type has the best education 2023

- Premium Statistic Share of parents with select views on what school type is best U.S 2024, by gender

- Premium Statistic Parents' beliefs on how gender identity is taught in school U.S. 2022, by party

- Premium Statistic Parents with select beliefs on how slavery is taught in school U.S. 2022, by party

- Premium Statistic Perceptions on the influence of K-12 parents or school boards U.S 2022, by party

- Premium Statistic Parents who believe teachers should lead students in prayers U.S. 2022, by party

- Premium Statistic Share of K-12 parents concerned about a violent intruder at school U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic K-12 parents' concerns on the effects of AI on their child's learning U.S. 2023

Main reasons why parents enroll their children in private or public schools U.S. 2024

Share of parents with various reasons why they chose to enroll their youngest child in a private or public school in the United States in 2024

Share of Americans with various views on what school type has the best education 2023

If it were your decision and you could select any type of school, and financial costs and transportation were of no concern, what type of school would you select in order to obtain the best education for your child?

Share of parents with select views on what school type is best U.S 2024, by gender

If given the option, what type of school would you select in order to obtain the best education for your child?

Parents' beliefs on how gender identity is taught in school U.S. 2022, by party

Share of parents of K-12 students with select beliefs on what children should learn about gender identity in school in the United States in 2022, by party

Parents with select beliefs on how slavery is taught in school U.S. 2022, by party

Share of parents of K-12 students with select beliefs on what children should learn about slavery in school in the United States in 2022, by party

Perceptions on the influence of K-12 parents or school boards U.S 2022, by party

Share of parents who believe that parents or the local school board have too much influence on what public K-12 schools are teaching in the United States in 2022, by political party

Parents who believe teachers should lead students in prayers U.S. 2022, by party

Share of parents who believe that public school teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers in the United States in 2022, by party

Share of K-12 parents concerned about a violent intruder at school U.S. 2023

Share of K-12 parents who were extremely concerned or very concerned about a violent intruder, such as a mass shooter, entering their child's/children's school in the United States in 2023, by grade of child

K-12 parents' concerns on the effects of AI on their child's learning U.S. 2023

How concerned are you about the effects of artificial intelligence, or AI, on your youngest/oldest child's learning this school year?

U.S. opinion

- Premium Statistic Share of Americans who are concerned about select issues in public schools U.S. 2023

- Premium Statistic U.S. views on who should influence LGBTQ-related school policies 2023

- Premium Statistic U.S. views on how slavery and racism should be taught in schools 2023

- Premium Statistic U.S. preferences for race-related curricula in K-12 schools 2023, by race

- Premium Statistic U.S. views on whether teachers should use students' preferred pronouns 2023

- Premium Statistic U.S. teens' comfortability with race and LGBTQ+ topics in the classroom 2023

- Premium Statistic Share of LBGTQ+ students with various reasons to drop out of high school U.S. 2021-22

- Premium Statistic Adults’ opinion on how K–12 schools should handle AI advances U.S. 2023-24

How concerned are you about the following issues in public schools in your local area?

U.S. views on who should influence LGBTQ-related school policies 2023

Share of adults who believe select groups should have a great deal of influence in deciding how to set school policy concerning discussion of LGBTQ people in the United States in 2023

U.S. views on how slavery and racism should be taught in schools 2023

Which of the following statements comes closest to your views?

U.S. preferences for race-related curricula in K-12 schools 2023, by race

Share of adults who believe various race-related curricula should be taught in K-12 schools in the United States in 2023, by race and ethnicity

U.S. views on whether teachers should use students' preferred pronouns 2023

If a teenager asks a teacher to use a particular pronoun – he, she or they – which do you think is the best policy?

U.S. teens' comfortability with race and LGBTQ+ topics in the classroom 2023

Share of teenagers who say they feel comfortable or uncomfortable when topics related to racism, racial inequality, sexual orientation, or gender identity come up in class in the United States in 2023

Share of LBGTQ+ students with various reasons to drop out of high school U.S. 2021-22

Share of LGBTQ+ students with various reasons why they do not plan to graduate high school or are unsure if they will graduate in the United States during the 2021-22 academic year

Adults’ opinion on how K–12 schools should handle AI advances U.S. 2023-24

Which of the following comes closest to your view on how K-12 schools should respond to advances in artificial intelligence (AI)?

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

What is K-12 Curriculum?

Natalie has been a teacher, educational consultant, and curriculum designer for 15 years and has a Master of Education degree in Instructional Design and Technology.

Table of Contents

What is k-12 curriculum, courses or subjects taught, learning objectives and activities, state or common core state standards, lesson summary.

In the field of education, K-12 refers to grades kindergarten through twelve where attendance is compulsory.

Curriculum can have multiple meanings, though the term generally describes, in some form or another, the learning experiences students have in the classroom. Curriculum can refer to:

- the courses or subjects students study in school

- the general learning goals and activities for a course, set of courses, or grade level

- the specific learning objectives or standards to be mastered

K-12 Curriculum as a general educational term typically refers to the content being taught and the learning experiences students have in the school setting in grades kindergarten through twelve. Now let's look at some more specific ways in which curriculum can be defined.

To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member. Create your account

An error occurred trying to load this video.

Try refreshing the page, or contact customer support.

You must c C reate an account to continue watching

Register to view this lesson.

As a member, you'll also get unlimited access to over 88,000 lessons in math, English, science, history, and more. Plus, get practice tests, quizzes, and personalized coaching to help you succeed.

Get unlimited access to over 88,000 lessons.

Already registered? Log in here for access

Resources created by teachers for teachers.

I would definitely recommend Study.com to my colleagues. It’s like a teacher waved a magic wand and did the work for me. I feel like it’s a lifeline.

You're on a roll. Keep up the good work!

Just checking in. are you still watching.

- 0:05 What Is K-12 Curriculum?

- 0:51 Courses or Subjects Taught

- 1:20 Learning Objectives…

- 2:23 State or Common Core Standards

- 3:50 Lesson Summary

In a broad sense, K-12 Curriculum can refer to the courses or subjects taught in school. For example, in the early elementary or primary grades, the curriculum usually includes courses in reading, writing, and mathematics. It may also include courses in social studies, science, music, art, and/or physical education. In high school, the subjects taught may be more specialized, like algebra, art history, Latin, orchestra, or biology.

More commonly in the field of education, K-12 Curriculum refers to the learning objectives and activities taught across grade levels. An example of a general learning objective for grades K-12 is for students to become proficient readers of grade-level appropriate texts. Another general learning objective is for students to apply their knowledge of mathematics to solve real-world problems. An example of a more specific learning objective in elementary school is for students to be able to correctly solve multiplication problems involving two digit factors.

An example of a K-12 learning activity is for students to work in groups to conduct experiments using the scientific method. Or students might create historically accurate costumes from a specified era. Yet another learning activity might be for students to correctly label all fifty United States on a printed map.

When educators talk about the K-12 curriculum, they're often referring to these types of activities: learning experiences that students have in the classroom.

As of 2015, the Common Core State Standards have been adopted in forty-six of the fifty United States. These academic standards for learning outline and articulate exactly what teachers should teach and what students are expected to learn at each grade level in various subjects. The standards have been developed over time by panels of experts in education and provide a foundation for learning and assessment across subjects and grade levels. K-12 curriculum, therefore, is often made up of a sequence of state and Common Core State Standards.

The Common Core State Standards focus on learning objectives in English language arts and literacy and mathematics. State standards often include learning objectives for other subjects, like science, social studies and humanities, and even art, physical education, and music. Often, when educators talk about the K-12 Curriculum, they're talking about the scope and sequence of these learning standards as they are covered in schools across grade levels.

The standards not only help educators identify which concepts and skills to teach, but they also provide standards for measuring student mastery. A solid K-12 curriculum should align with the standards and follow a logical sequence or path for learning as students move through the grade levels. The K-12 curriculum usually aligns directly with the instruments and assessments adopted for measuring student success, including standardized statewide testing.

K-12 curriculum is a broad educational term with multiple meanings. While there is no single perfect definition for the term, here are a few key things to remember:

- K-12 curriculum can refer to the courses or subjects taught in school from grades kindergarten through twelve.

- As it is used in the field of education, K-12 curriculum usually refers to the specific learning objectives and activities experienced by students in grades kindergarten through twelve.

- The K-12 curriculum is most clearly defined by the state and/or Common Core State Standards of learning adopted in a school community and typically outlines a sequence of instruction and assessments directly aligned to those learning standards.

Unlock Your Education

See for yourself why 30 million people use study.com, become a study.com member and start learning now..

Already a member? Log In

Recommended Lessons and Courses for You

Related lessons, related courses, recommended lessons for you.

What is K-12 Curriculum? Related Study Materials

- Related Topics

Browse by Courses

- Psychology for Teachers: Professional Development

- Educational Psychology for Teachers: Professional Development

- Abnormal Psychology: Tutoring Solution

- Abnormal Psychology: Homework Help Resource

- Social Psychology Textbook

- Gerontology for Teachers: Professional Development

- Developmental Psychology: Certificate Program

- Life Span Developmental Psychology: Help and Review

- Life Span Developmental Psychology: Tutoring Solution

- UExcel Introduction to Psychology: Study Guide & Test Prep

- Intro to Psychology Syllabus Resource & Lesson Plans

- Abnormal Psychology Syllabus Resource & Lesson Plans

- DSST Lifespan Developmental Psychology Prep

- Social Psychology Syllabus Resource & Lesson Plans

- AP Psychology Textbook

Browse by Lessons

- Teaching Kids About the Brain

- Broaden-and-Build Theory | Overview, Examples & Criticisms

- How to Stop Bullying in School

- Student Behavior Contracts: Examples and Templates

- Using Cell Phones in the Classroom: Pros and Cons

- Managing Disruptive Behavior in the Classroom

- Structural Equation Modeling: Introduction & Example

- Content Domain: Definition & Explanation

- How to Teach Mental Math

- Teaching Decoding of Multisyllabic Words

Create an account to start this course today Used by over 30 million students worldwide Create an account

Explore our library of over 88,000 lessons

- Foreign Language

- Social Science

- See All College Courses

- Common Core

- High School

- See All High School Courses

- College & Career Guidance Courses

- College Placement Exams

- Entrance Exams

- General Test Prep

- K-8 Courses

- Skills Courses

- Teacher Certification Exams

- See All Other Courses

- Create a Goal

- Create custom courses

- Get your questions answered

Become an Insider

Sign up today to receive premium content.

Hybrid Learning: What is it & What Does it Mean For K-12 Schools?

Doug Bonderud is an award-winning writer capable of bridging the gap between complex and conversational across technology, innovation and the human condition.

Faced with ongoing and unpredictable pandemic challenges, K–12 schools have been forced to get creative — finding new ways to facilitate learning at a distance, sustain student engagement and deliver consistent success.

It’s been no easy task. Data collected by Education Week highlights the continually changing, state-by-state nature of the U.S. COVID-19 response: Some school districts have been ordered open, others remain completely closed and many are left to find a functional balance between in-person and virtual learning on their own.

Given unfamiliarity of the U.S. K-12 system with virtual learning at this scale, substantial confusion remains around effective application across online environments — and what this solution means for schools going forward in 2021.

To help clarify what hybrid learning means, and how it might differ from similar terms that preceded it, we need to start by examining the definition of the term.

What Is the Hybrid Learning Model and How Has it Evolved?

At its most basic, “hybrid learning uses online components for teaching and learning that replaces face-to-face classroom time,” says Verjeana McCotter-Jacobs, chief transformation officer for the National School Boards Association .

While initial hybrid learning approaches happened almost entirely at home — for both students and teachers — McCotter-Jacobs notes that in many cases, “teachers were in the classroom teaching both in-person and online as schools shifted from an all-remote approach to a combination of virtual and in-person classes.”

As a result, the hybrid model is now used to supplement multiple solutions for student success. In some schools, this means having students at home part time and in class part time; other districts have chosen to keep certain grade groups home full time and allow younger children to return in person.

How Does Hybrid Learning Differ from Blended Learning?

While the terms “hybrid learning” and “blended learning” are often used interchangeably, they’re not identical.

“It can be confusing, but when you think about blended learning, you’re not taking away from face time. Instead, it’s about providing online materials and tools that supplement learning rather than replacing the face-to-face experience,” says McCotter-Jacobs.

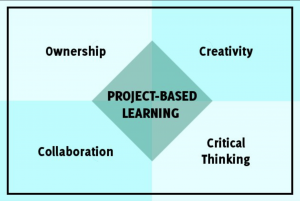

In practice, blended learning often takes the form of new initiatives such as project-based learning that add multimedia resources to common coursework and allow students to self-direct some of their learning to explore the holistic results of differing educational disciplines such as math, science or math and sciences.

Hybrid classes, meanwhile, take these online tools and provide them to students through remote learning portals and online learning management systems for use outside of the traditional school environment.

When it comes to hybrid learning vs. blended learning, here’s a good rule of thumb: If tools augment face-to-face frameworks, they’re blended learning models. If they facilitate the replacement of in-person instruction, they’re hybrid.

What Strategies Can Schools Use to Improve Hybrid Learning Models?

Recent research from the Economic Policy Institute suggests that online teaching and learning models can be effective “if students have consistent access to the Internet and computers and if teachers have received targeted training and supports for online instruction.”

McCotter-Jacobs echoes this sentiment, noting that “teachers in many cases are older and are not necessarily equipped for this technology.”

In fact, some of the biggest pain points that have emerged have less to do with the technology used to facilitate remote learning and hybrid learning itself and more to do with tech-challenged educators tasked with using that technology.

“The training and support they need is critical, and it’s not just for the software itself. How do they create lesson plans under this new model? How do they help students who are struggling? What happens when the software fails?” she says.

For McCotter-Jacobs, there’s one rule to follow when it comes to tapping the benefits of hybrid learning: Keep it simple. From streamlining the volume of applications and services students use to reducing the number of passwords and logins required to gain access, simplicity benefits students, teachers and parents alike.

DISCOVER: 5 tips for an effective hybrid instruction experience.

What Technologies Are Required for Effective Hybrid Learning Plans?

Hybrid classes are only effective when backed by the right technologies . For McCotter-Jacobs, this starts with Wi-Fi in school buildings, especially as some kids head back to the classroom part time.

She also notes, however, that in-school Wi-Fi isn’t enough to create effective hybrid learning plans because many families lack access to reliable broadband internet at home. “There’s a vast deficiency here,” says McCotter-Jacobs, “with at least 17 million students lacking access to high-speed internet.”

To address this issue, McCotter-Jacobs notes, some districts equipped school buses with Wi-Fi and then drove these buses into underserved neighborhoods. Still, she says, there is a need for broader support to address the digital divide in education. As a result, she says, the NSBA has called for an additional $12 billion from the federal government to help deal with the homework gap and help facilitate effective hybrid learning.

What Does the Next Iteration of Hybrid Learning Look Like?

For those under the assumption that hybrid learning is a temporary stopgap, McCotter-Jacobs cautions that “the new normal is not going away.”

As schools prepare for a potential return to the classroom in fall 2021, several elements of hybrid learning will remain. This could take the form of families opting for at-home learning out of an abundance of caution until vaccine rollouts reach a certain threshold or schools choosing a partially hybrid model to reduce classroom overcrowding and improve one-on-one interaction.

That’s why it’s important for educators to embrace the hybrid learning shift as a foundational change to be absorbed and implemented into the broader plan and vision for the future of education.

“There’s an opportunity here for schools to get creative and shift the way students learn and the way teachers provide guidance,” says McCotter-Jacobs.

While she notes that this approach isn’t without its challenges, given “the many intangibles that we can’t put our finger on and the need for the right combination of funds, training and creative minds,” McCotter-Jacobs believes that hybrid learning can have a positive impact if it’s at the forefront of educational change.

“This shift can help take kids to the next iteration of learning,” she says, “and it’s not sitting in a classroom.”

MORE ON EDTECH: Google for education offers an effective ecosystem for hybrid learning.

- Blended Learning

- Online Learning

Related Articles

Unlock white papers, personalized recommendations and other premium content for an in-depth look at evolving IT

Copyright © 2024 CDW LLC 200 N. Milwaukee Avenue , Vernon Hills, IL 60061 Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- ProctorEdu Glossary →

- Terms starting with K →

- K-12 Education

K-12 Education - Definition & Meaning

Other terms starting with k, related articles.

| Make a request |

Integrated with

| Request a demo |

A primer on elementary and secondary education in the United States

Editor’s Note: This report is an excerpt, with minor edits, from Addressing Inequities in the US K-12 Education System , which first appeared in Rebuilding the Pandemic Economy , published by the Aspen Economic Strategy Group in 2021.

This report reviews the basics of the American elementary and secondary education system: Who does what and how do we pay for it? While there are some commonalities across the country, the answers to both questions, it turns out, vary considerably across states. 1

Who does what?

Schools are the institution most visibly and directly responsible for educating students. But many other actors and institutions affect what goes on in schools. Three separate levels of government—local school districts, state governments, and the federal government—are involved in the provision of public education. In addition, non-governmental actors, including teachers’ unions, parent groups, and philanthropists play important roles.

Most 5- to 17-year-old children – about 88%– attend public schools. 2 (Expanding universal schooling to include up to two years of preschool is an active area of discussion which could have far-reaching implications, but we focus on grades K-12 here.) About 9% attend private schools; about a quarter of private school students are in non-sectarian schools, and the remaining three-quarters are about evenly split between Catholic and other religious schools. The remaining 3% of students are homeschooled.

Magnet schools are operated by local school districts but enroll students from across the district; magnet schools often have special curricula—for example, a focus on science or arts—and were sometimes designed specifically to encourage racial integration. Charter schools are publicly funded and operate subject to state regulations; private school regulations and homeschooling requirements are governed by state law and vary across states. Nationally, 6.8% of public school students are enrolled in charter schools; the remainder attend “traditional public schools,” where students are mostly assigned to schools based on their home address and the boundaries school districts draw. Washington, D.C. and Arizona have the highest rates of charter enrollment, with 43 and 19% of their public school students attending charter schools. Several states have little or no charter school enrollment. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly all public schooling took place in person, with about 0.6% of students enrolled in virtual schools.

Local School Districts

Over 13,000 local education agencies (LEAs), also known as school districts, are responsible for running traditional public schools. The size and structure of local school districts, as well as the powers they have and how they operate, depend on the state. Some states have hundreds of districts, and others have dozens. District size is mostly historically determined rather than a reflection of current policy choices. But while districts can rarely “choose” to get smaller or larger, district size implicates important trade-offs . Having many school districts operating in a metropolitan area can enhance incentives for school and district administrators to run schools consistent with the preferences of residents, who can vote out leaders or vote with their feet by leaving the district. On the other hand, fragmentation can lead to more segregation by race and income and less equity in funding, though state laws governing how local districts raise revenue may address the funding issues. Larger districts can benefit from economies of scale as the fixed costs of operating a district are spread over more students and they are better able to operate special programs, but large districts can also be difficult to manage. And even though large districts have the potential to pool resources between more- and less-affluent areas, equity challenges persist as staffing patterns lead to different levels of spending at schools within the same district.

School boards can be elected or appointed, and they generally are responsible for hiring the chief school district administrator, the superintendent. In large districts, superintendent turnover is often cited as a barrier to sustained progress on long term plans, though the causation may run in the other direction: Making progress is difficult, and frustration with reform efforts leads to frequent superintendent departures. School districts take in revenue from local, state, and federal sources, and allocate resources—primarily staff—to schools. The bureaucrats in district “central offices” oversee administrative functions including human resources, curriculum and instruction, and compliance with state and federal requirements. The extent to which districts devolve authority over instructional and organizational decisions to the school level varies both across and within states.

State Governments

The U.S. Constitution reserves power over education for the states. States have delegated authority to finance and run schools to local school districts but remain in charge when it comes to elementary and secondary education. State constitutions contain their own—again, varying—language about the right to education, which has given rise to litigation over the level and distribution of school funding in nearly all states over the past half century. States play a major role in school finance, both by sending aid to local school districts and by determining how local districts are allowed to tax and spend, as discussed further below.

State legislatures and state education agencies also influence education through mechanisms outside the school finance system. For example, states may set requirements for teacher certification and high school graduation, regulate or administer retirement systems, determine the ages of compulsory schooling, decide how charter schools will (or will not) be established and regulated, set home-schooling requirements, establish curricular standards or approve specific instructional materials, choose standardized tests and proficiency standards, set systems for school accountability (subject to federal law), and create (or not) education tax credits or vouchers to direct public funds to private schools. Whether and how states approach these issues—and which functions they delegate to local school districts—varies considerably.

Federal Government

The authority of the federal government to direct schools to take specific actions is weak. Federal laws protect access to education for specific groups of students, including students with disabilities and English language learners. Title IX prohibits sex discrimination in education, and the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of race. The U.S. Department of Education issues regulations and guidance on K-12 laws and oversees grant distribution and compliance. It also collects and shares data and funds research. The Bureau of Indian Education is housed in the Department of the Interior, not the Department of Education.

The federal government influences elementary and secondary education primarily by providing funding—and through the rules surrounding the use of those funds and the conditions that must be met to receive federal funding. Federal aid is typically allocated according to formulas targeting particular populations. The largest formula-aid federal programs are Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which provides districts funds to support educational opportunity, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), for special education. Both allocate funding in part based on child poverty rates. State and school district fiscal personnel ensure that districts comply with rules governing how federal funds can be spent and therefore have direct influence on school environments. Since 1965, in addition to specifying how federal funds can be spent, Congress has required states and districts to adopt other policies as a condition of Title I receipt. The policies have changed over time, but most notably include requiring school districts to desegregate, requiring states to adopt test-based accountability systems, and requiring the use of “evidence-based” approaches.

IDEA establishes protections for students with disabilities in addition to providing funding. The law guarantees their right to a free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive setting and sets out requirements for the use of Individualized Educational Programs. Because of these guarantees, IDEA allows students and families to pursue litigation. Federal law prohibits conditioning funding on the use of any specific curriculum. The Obama Administration’s Race to the Top program was also designed to promote specific policy changes—many related to teacher policy—but through a competitive model under which only select states or districts “won” the funds. For the major formula funds, like Title I and IDEA, the assumption (nearly always true) is that states and districts will adopt the policies required to receive federal aid and all will receive funds; in some cases, those policy changes may have more impact than the money itself. The federal government also allocated significant funding to support schools during the Great Recession and during the COVID-19 pandemic through specially created fiscal stabilization or relief funds; federal funding for schools during the COVID crisis was significantly larger than during the Great Recession.

The federal tax code, while perhaps more visible in its influence on higher education, also serves as a K-12 policy lever. The controversial state and local tax deduction, now limited to $10,000, reduces federal tax collections and subsidizes progressive taxation for state and local spending, including for education. As of 2018, 529 plans, which historically allowed tax-preferred savings only for higher education expenses, can also be used for private K-12 expenses.

Non-Governmental Actors

Notable non-governmental actors in elementary and secondary education include teachers’ unions and schools of education, along with parents, philanthropists, vendors, and other advocates.The nation’s three million public school teachers are a powerful political force, affecting more than just teachers’ compensation. For example, provisions of collective bargaining agreements meant to improve teachers working conditions also limit administrator flexibility. Teachers unions are also important political actors; they play an active role in federal, state, and school board elections and advocate for (or, more often, against) a range of policies affecting education. Union strength varies considerably across U.S. states.

Both states and institutions of higher education play important roles in determining who teaches and the preparation they receive. Policies related to teacher certification and preparation requirements, ranging from whether teachers are tested on academic content to which teachers are eligible to supervise student teachers, vary considerably across states. 3 Meanwhile, reviews of teacher training programs reveal many programs do not do a good job incorporating consensus views of research-based best practices in key areas. To date, schools of education have not been the focus of much policy discussion, but they would be critical partners in any changes to how teachers are trained.

Parents play an important role, through a wide range of channels, in determining what happens in schools. Parents choose schools for their children, either implicitly when they choose where to live or explicitly by enrolling in a charter school, private school, participating in a school district choice program, or homeschooling, though these choices are constrained by income, information, and other factors. They may also raise money through Parent Teacher Associations (PTAs) or other foundations—and determine how it is spent. And they advocate for (or against) specific policies, curriculum, or other aspects of schooling through parent organizations, school boards, or other levels of government. Parents often also advocate for their children to receive certain teachers, placements, evaluation, or services; this is particularly true for parents of students with disabilities, who often must make sure their children receive legally required services and accommodations. Though state and federal policymakers sometimes mandate parent engagement , these mechanisms do not necessarily provide meaningful pathways for parental input and are often dominated by white and higher-SES parents .

Philanthropy also has an important influence on education policy, locally and nationally. Not only do funders support individual schools in traditional ways, but they are also increasingly active in influencing federal and state laws. Part of these philanthropic efforts happen through advocacy groups, including civil rights groups, religious groups, and the hard-to-define “education reform” movement. Finally, the many vendors of curriculum, assessment, and “edtech” products and services bring their own lobbying power.

Paying for school

Research on school finance might be better termed school district finance because districts are the jurisdictions generating and receiving revenue, and districts, not schools, are almost always responsible for spending decisions. School districts typically use staffing models to send resources to schools, specifying how many staff positions (full-time equivalents), rather than dollars, each school gets.

Inflation-adjusted, per-pupil revenue to school districts has increased steadily over time and averaged about $15,500 in 2018-19 (total expenditure, which includes both ongoing and capital expenditure, is similar but we focus on revenue because we are interested in the sources of revenue). Per-pupil revenue growth tends to stall or reverse in recessions and has only recently recovered to levels seen prior to the Great Recession (Figure 1). On average, school districts generated about 46% of their revenue locally, with about 80% of that from property taxes; about 47% of revenue came from state governments and about 8% from the federal government. The share of revenue raised locally has declined from about 56% in the early 1960s to 46% today, while the state and federal shares have grown. Local revenue comes from taxes levied by local school districts, but local school districts often do not have complete control over the taxes they levy themselves, and they almost never determine exactly how much they spend because that depends on how much they receive in state and federal aid. State governments may require school districts to levy certain taxes, limit how much local districts are allowed to tax or spend, or they may implicitly or explicitly redistribute some portion of local tax revenue to other districts.

Both the level of spending and distribution of revenue by source vary substantially across states (Figure 2), with New York, the highest-spending state, spending almost $30,000 per pupil, while Idaho, Utah, and Oklahoma each spent under $10,000 per pupil. (Some, but far from all, of this difference is related to higher labor costs in New York.) Similarly, the local share of revenue varies from less than 5% in Hawaii and Vermont to about 60% in New Hampshire and Nebraska. On average, high-poverty states spend less, but there is also considerable variation in spending among states with similar child poverty rates.

Discussions of school funding equity—and considerable legal action—focus on inequality of funding across school districts within the same state . While people often assume districts serving disadvantaged students spend less per pupil than wealthier districts within a state, per-pupil spending and the child poverty rate are nearly always uncorrelated or positively correlated, with higher-poverty districts spending more on average. Typically, disadvantaged districts receive more state and federal funding, offsetting differences in funding from local sources. Meanwhile, considerable inequality exists between states, and poorer states spend less on average. Figure 3 illustrates an example of this dynamic, showing the relationship between district-level per-pupil spending and the child poverty rate in North Carolina (a relatively low-spending state with county- and city-based districts) and Illinois (a higher-spending state with many smaller districts). In North Carolina, higher poverty districts spend more on average; Illinois is one of only a few states in which this relationship is reversed. But this does not mean poor kids get fewer resources in Illinois than in North Carolina. Indeed, nearly all districts in Illinois spend more than most districts in North Carolina, regardless of poverty rate.

Figure 4 gives a flavor of the wide variation in per-pupil school spending. Nationally, the district at the 10th percentile had per-pupil current expenditure of $8,800, compared to $18,600 at the 90th percentile (for these calculations we focus on current expenditure, which is less volatile year-to-year, rather than revenue). Figure 4 shows that this variation is notably not systematically related to key demographics. For example, on average, poor students attend school in districts that spent $13,023 compared to $13,007 for non-poor students. The average Black student attends school in a district that spent $13,485 per student, compared to $12,918 for Hispanic students and $12,736 for White students. 4 School districts in high-wage areas need to spend more to hire the same staff, but adjusting spending to account for differences in prevailing wages of college graduates (the second set of bars) does not change the picture much.

Does this mean the allocation of spending is fair? Not really. First, to make progress reducing the disparities in outcomes discussed above, schools serving more disadvantaged students will need to spend more on average. Second, these data are measured at the school district level, lumping all schools together. This potentially masks inequality across (as well as within) schools in the same district.

The federal government now requires states to report some spending at the school level; states have only recently released these data. One study using these new data finds that within districts, schools attended by students of color and economically-disadvantaged students tend to have more staff per pupil and to spend more per pupil. These schools also have more novice teachers. How could within-district spending differences systematically correlate with student characteristics, when property taxes and other revenues for the entire district feed into the central budget? Most of what school districts buy is staff, and compensation is largely based on credentials and experience. So schools with less-experienced teachers spend less per pupil than those with more experienced ones, even if they have identical teacher-to-student ratios. Research suggests schools enrolling more economically disadvantaged students, or more students of color, on average have worse working conditions for teachers and experience more teacher turnover. Together, this means that school districts using the same staffing rules for each school—or even allocating more staff to schools serving more economically disadvantaged students—would have different patterns in spending per pupil than staff per pupil.

[1] : For state-specific information, consult state agency websites (e.g., Maryland State Department of Education) for more details. You can find data for all 50 states at the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics , and information on state-specific policies at the Education Commission of the States .

[2] : The numbers in this section are based on the most recent data available in the Digest of Education Statistics, all of which were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

[3] : See the not-for-profit National Council on Teacher Quality for standards and reviews of teacher preparation programs, and descriptions of state teacher preparation policies.

[4] : These statistics may be particularly surprising to people given the widely publicized findings of the EdBuild organization that, “ Nonwhite school districts get $23 billion less than white school districts. ” The EdBuild analysis estimates gaps between districts where at least 75% of students are non-White versus at least 75% of students are White. These two types of districts account for 53% of enrollment nationally. The $23 billion refers to state and local revenue (excluding federal revenue), whereas we focus on current expenditure (though patterns for total expenditure or total revenue are similar).

Disclosures: The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here . The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation .

About the Authors

Sarah reber, joseph a. pechman senior fellow – economic studies, nora gordon, professor – mccourt school of public policy, georgetown university.

Global Mobility

Global leadership, global education.

- Global (home)

Brazil & Latin America

Australasia

New Zealand

Europe & the UK

Isle of Man

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Switzerland

Middle East

- Think Global People

K-12 Curriculum and pupil assessment

What is the K-12 system and how are pupils assessed along the way? Relocate takes a look at how the US education system differs from other countries around the world.

| Year in England | Age of student | Grade in the US |

| Nursery | 3–4 | Preschool |

| Reception | 4–5 | Preschool |

| Year 1 | 5–6 | Kindergarten |

| Year 2 | 6–7 | Grade 1 |

| Year 3 | 7–8 | Grade 2 |

| Year 4 | 8–9 | Grade 3 |

| Year 5 | 9–10 | Grade 4 |

| Year 6 | 10–11 | Grade 5 |

| Year 7 | 11–12 | Grade 6 |

| Year 8 | 12–13 | Grade 7 |

| Year 9 | 13–14 | Grade 8 |

| Year 10 | 14–15 | Grade 9 |

| Year 11 | 15–16 | Grade 10 |

| Year 12 | 16–17 | Grade 11 |

| Year 13 | 17–18 | Grade 12 |

- China's expanding international school options

- Education in Germany

- Relocating to the US

Common Core standardised testing in the US

Relocate global’s new annual guide to international education & schools provides a wealth of advice to anyone searching for a new school in the uk and in an international setting, and offers insights into what it takes to make the right school choice. .

©2024 Re:locate magazine, published by Profile Locations, Spray Hill, Hastings Road, Lamberhurst, Kent TN3 8JB. All rights reserved. This publication (or any part thereof) may not be reproduced in any form without the prior written permission of Profile Locations. Profile Locations accepts no liability for the accuracy of the contents or any opinions expressed herein.

Related Articles

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Merging Innovation with Tradition at Mougins School

Mougins School

New release International Education & Schools' Fair webinars

The Benefits of a Bilingual Education

Choosing a school in Malaysia

Editor's Choice

Global News

Immigration

International Assignments

Mobility Industry

Employee Benefits

Partner & Family Support

Residential Property

Remote Working

Serviced Apartments

Global Expansion

Leadership & Management

Talent Management

Human Resources

Business Travel

Culture & Language

Learning and Development

Education & Schools

Country Guides to Education & Schools

Featured Schools and Directory

Guide to International Education and Schools Articles

Schools' Fair

Online Schools Webinars

Education Webinars

Research and Higher Education

Education Consultants

School Groups

Online Schools

About Relocate Global

Contact Relocate Global

Meet the Relocate team

Employment Opportunities

Newsletters

Relocate Global Mobility App

Get in touch

+44 (0)1892 891334

Relocate Global Privacy Policy

Privacy and Cookies

U.S. Government Accountability Office

K-12 Education

Issue summary.

The U.S. Department of Education and other federal agencies work to ensure that 50 million students in K-12 public schools have access to a safe, quality education. However, a history of discriminatory practices has contributed to inequities in education, which are intertwined with disparities in wealth, income, and housing. Moreover, there are ongoing concerns about the safety and well-being of all students. To help address these issues, Education should strengthen its oversight of key programs, policies, and data collections.

For example:

- The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted learning for millions of students during the 2020-21 school year. Certain student populations were more likely to face significant obstacles to learning in a virtual environment—such as high-poverty students and students learning English. Some children also never attended class during the 2020-2021 school year.

- As the COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased use of remote education, K-12 schools across the nation have increasingly reported ransomware and other types of cyberattacks. Federal agencies offer products and services to help schools prevent and respond to cyberattacks. But Education's plan for addressing risks to schools was issued in 2010 and needs an update to deal with changing cybersecurity risks.

- The U.S. is experiencing a shortage of teachers – a problem that worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic amid reports of teachers leaving the profession, fewer new teachers entering, and schools struggling to hire teachers. While Education has introduced a strategy to address these issues, progress can be made to ensure its efforts are working.

- While nearly all public school districts require students to adhere to dress codes, concerns about equity in school dress codes have included the detrimental effects of removing students from the classroom for dress code violations. A review of a nationally representative sample of public school district dress codes revealed school dress codes more frequently restrict items typically worn by girls. Additionally, rules about hair and head coverings can disproportionately affect Black students and those of certain religions and cultures.

- School districts spend billions of dollars a year (primarily from local government sources) on building and renovating facilities at the nearly 100,000 K-12 public schools nationwide. A survey of school facilities brought up common issues and priorities, such as improving security , expanding technology, and addressing health hazards. Additionally, about half of districts reported needing to update or replace multiple systems like heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) or plumbing. Accessing public school facilities was also reported as a challenge, with survey results showing that two-thirds of school districts had facilities with physical barriers that may limit access for students with disabilities.

- Even before the pandemic, virtual public school enrollment was growing—mostly in virtual charter schools. Compared to students in brick-and-mortar public schools, 2018-2019 data showed that a lower percentage of virtual school students took state achievement tests, and their scores were significantly lower. Also, Education officials said the virtual environment makes it harder to monitor attendance. Certain federal funds are allocated using attendance data, so there's a risk that virtual schools could get more or less funding than they should.

- Education requires public school districts to biennially report incidents of restraint (restricting a student’s movement) and seclusion (confining a student to a space alone). However, Education’s data quality checks may not catch misreporting or statistical outliers. For instance, 70% of districts reported 0 incidents of restraint and seclusion, but Education’s quality check only applies to fewer than 100 large districts. Education also doesn’t have a quality check for districts reporting relatively high incident rates—such as one that reported an average of 71 restraint incidents per student per year.

- A review of school shooting data found that half were committed by current or former students. Suburban and rural, wealthier, and low-minority schools had more school-targeted shootings; such shootings were the most fatal and most commonly committed by students. Urban, poor, and high-minority schools had more shootings overall and were more motivated by disputes; these shootings were often committed by non-students or unknown shooters.

Recent Reports

K-12 Education: DOD Should Assess Whether Troops-to-Teachers is Meeting Program Goals

K-12 Education: Additional Guidance Could Improve the Equitable Services Process for School Districts and Private Schools

K-12 Education: New Charter Schools Receiving Grants to Open Grew Faster Than Peers

K-12 Education: Education Should Assess Its Efforts to Address Teacher Shortages

K-12 Education: Department of Education Should Provide Information on Equity and Safety in School Dress Codes

K-12 Education: Charter Schools That Received Federal Funding to Open or Expand Were Generally Less Likely to Close Than Other Similar Charter Schools

K-12 Education: Student Population Has Significantly Diversified, but Many Schools Remain Divided Along Racial, Ethnic, and Economic Lines

Pandemic Learning: Less Academic Progress Overall, Student and Teacher Strain, and Implications for the Future

Pandemic Learning: Teachers Reported Many Obstacles for High-Poverty Students and English Learners As Well As Some Mitigating Strategies

Special Education: DOD Programs and Services for Military-Dependent Students with Disabilities

District of Columbia Charter Schools: DC Public Charter School Board Should Include All Required Elements in Its Annual Report

Related Pages

Related Coronavirus Oversight

Related Race in America

GAO Contacts

What Is Critical Race Theory, and Why Is It Under Attack?

- Share article

Education Week is the #1 source of high-quality news and insights on K-12 education. Sign up for our EdWeek Update newsletter to get stories like this delivered to your inbox daily.

Is “critical race theory” a way of understanding how American racism has shaped public policy, or a divisive discourse that pits people of color against white people? Liberals and conservatives are in sharp disagreement.

The topic has exploded in the public arena this spring—especially in K-12, where numerous state legislatures are debating bills seeking to ban its use in the classroom.

In truth, the divides are not nearly as neat as they may seem. The events of the last decade have increased public awareness about things like housing segregation, the impacts of criminal justice policy in the 1990s, and the legacy of enslavement on Black Americans. But there is much less consensus on what the government’s role should be in righting these past wrongs. Add children and schooling into the mix and the debate becomes especially volatile.

School boards, superintendents, even principals and teachers are already facing questions about critical race theory, and there are significant disagreements even among experts about its precise definition as well as how its tenets should inform K-12 policy and practice. This explainer is meant only as a starting point to help educators grasp core aspects of the current debate.

Just what is critical race theory anyway?

Critical race theory is an academic concept that is more than 40 years old. The core idea is that race is a social construct, and that racism is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies.

The basic tenets of critical race theory, or CRT, emerged out of a framework for legal analysis in the late 1970s and early 1980s created by legal scholars Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Richard Delgado, among others.

A good example is when, in the 1930s, government officials literally drew lines around areas deemed poor financial risks, often explicitly due to the racial composition of inhabitants. Banks subsequently refused to offer mortgages to Black people in those areas.

Today, those same patterns of discrimination live on through facially race-blind policies, like single-family zoning that prevents the building of affordable housing in advantaged, majority-white neighborhoods and, thus, stymies racial desegregation efforts.

CRT also has ties to other intellectual currents, including the work of sociologists and literary theorists who studied links between political power, social organization, and language. And its ideas have since informed other fields, like the humanities, the social sciences, and teacher education.

This academic understanding of critical race theory differs from representation in recent popular books and, especially, from its portrayal by critics—often, though not exclusively, conservative Republicans. Critics charge that the theory leads to negative dynamics, such as a focus on group identity over universal, shared traits; divides people into “oppressed” and “oppressor” groups; and urges intolerance.

Thus, there is a good deal of confusion over what CRT means, as well as its relationship to other terms, like “anti-racism” and “social justice,” with which it is often conflated.

To an extent, the term “critical race theory” is now cited as the basis of all diversity and inclusion efforts regardless of how much it’s actually informed those programs.

One conservative organization, the Heritage Foundation, recently attributed a whole host of issues to CRT , including the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, LGBTQ clubs in schools, diversity training in federal agencies and organizations, California’s recent ethnic studies model curriculum, the free-speech debate on college campuses, and alternatives to exclusionary discipline—such as the Promise program in Broward County, Fla., that some parents blame for the Parkland school shootings. “When followed to its logical conclusion, CRT is destructive and rejects the fundamental ideas on which our constitutional republic is based,” the organization claimed.

(A good parallel here is how popular ideas of the common core learning standards grew to encompass far more than what those standards said on paper.)

Does critical race theory say all white people are racist? Isn’t that racist, too?

The theory says that racism is part of everyday life, so people—white or nonwhite—who don’t intend to be racist can nevertheless make choices that fuel racism.

Some critics claim that the theory advocates discriminating against white people in order to achieve equity. They mainly aim those accusations at theorists who advocate for policies that explicitly take race into account. (The writer Ibram X. Kendi, whose recent popular book How to Be An Antiracist suggests that discrimination that creates equity can be considered anti-racist, is often cited in this context.)

Fundamentally, though, the disagreement springs from different conceptions of racism. CRT puts an emphasis on outcomes, not merely on individuals’ own beliefs, and it calls on these outcomes to be examined and rectified. Among lawyers, teachers, policymakers, and the general public, there are many disagreements about how precisely to do those things, and to what extent race should be explicitly appealed to or referred to in the process.