What Is the Contact Hypothesis in Psychology?

Can getting to know members of other groups reduce prejudice?

Jacob Ammentorp Lund / Getty Images

- Archaeology

- Ph.D., Psychology, University of California - Santa Barbara

- B.A., Psychology and Peace & Conflict Studies, University of California - Berkeley

The contact hypothesis is a theory in psychology which suggests that prejudice and conflict between groups can be reduced if members of the groups interact with each other.

Key Takeaways: Contact Hypothesis

- The contact hypothesis suggests that interpersonal contact between groups can reduce prejudice.

- According to Gordon Allport, who first proposed the theory, four conditions are necessary to reduce prejudice: equal status, common goals, cooperation, and institutional support.

- While the contact hypothesis has been studied most often in the context of racial prejudice, researchers have found that contact was able to reduce prejudice against members of a variety of marginalized groups.

Historical Background

The contact hypothesis was developed in the middle of the 20th century by researchers who were interested in understanding how conflict and prejudice could be reduced. Studies in the 1940s and 1950s , for example, found that contact with members of other groups was related to lower levels of prejudice. In one study from 1951 , researchers looked at how living in segregated or desegregated housing units was related to prejudice and found that, in New York (where housing was desegregated), white study participants reported lower prejudice than white participants in Newark (where housing was still segregated).

One of the key early theorists studying the contact hypothesis was Harvard psychologist Gordon Allport , who published the influential book The Nature of Prejudice in 1954. In his book, Allport reviewed previous research on intergroup contact and prejudice. He found that contact reduced prejudice in some instances, but it wasn’t a panacea—there were also cases where intergroup contact made prejudice and conflict worse. In order to account for this, Allport sought to figure out when contact worked to reduce prejudice successfully, and he developed four conditions that have been studied by later researchers.

Allport’s Four Conditions

According to Allport, contact between groups is most likely to reduce prejudice if the following four conditions are met:

- The members of the two groups have equal status. Allport believed that contact in which members of one group are treated as subordinate wouldn’t reduce prejudice—and could actually make things worse.

- The members of the two groups have common goals.

- The members of the two groups work cooperatively. Allport wrote , “Only the type of contact that leads people to do things together is likely to result in changed attitudes.”

- There is institutional support for the contact (for example, if group leaders or other authority figures support the contact between groups).

Evaluating the Contact Hypothesis

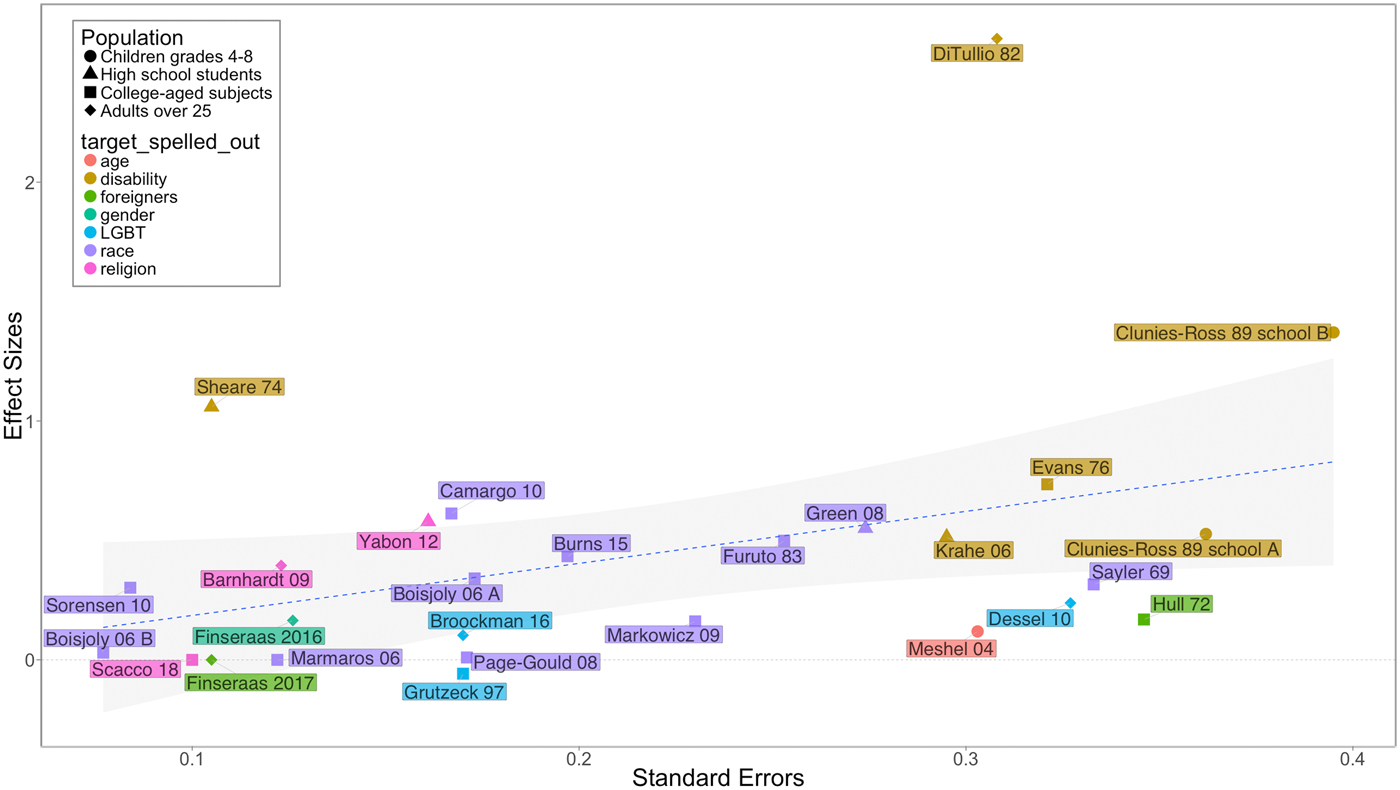

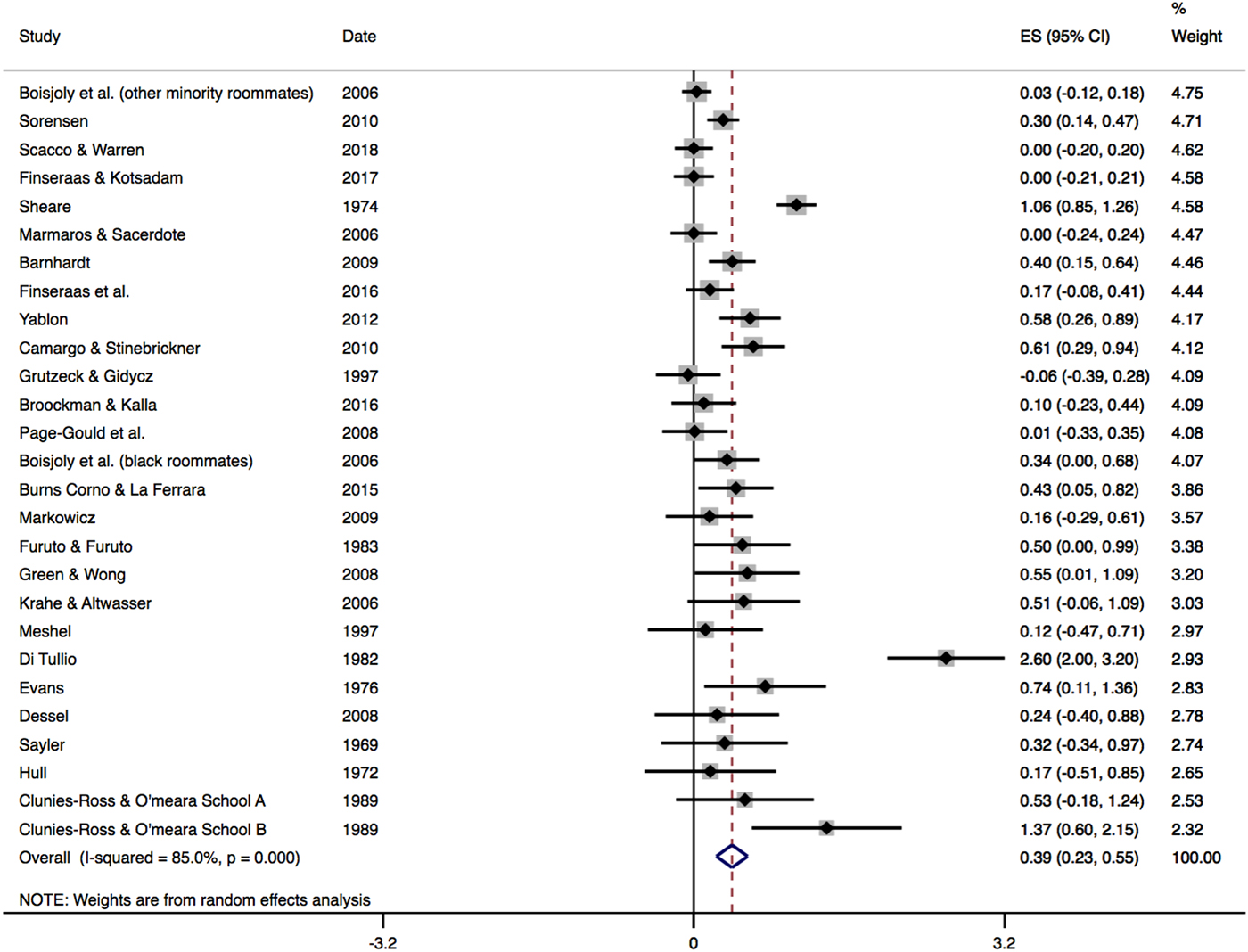

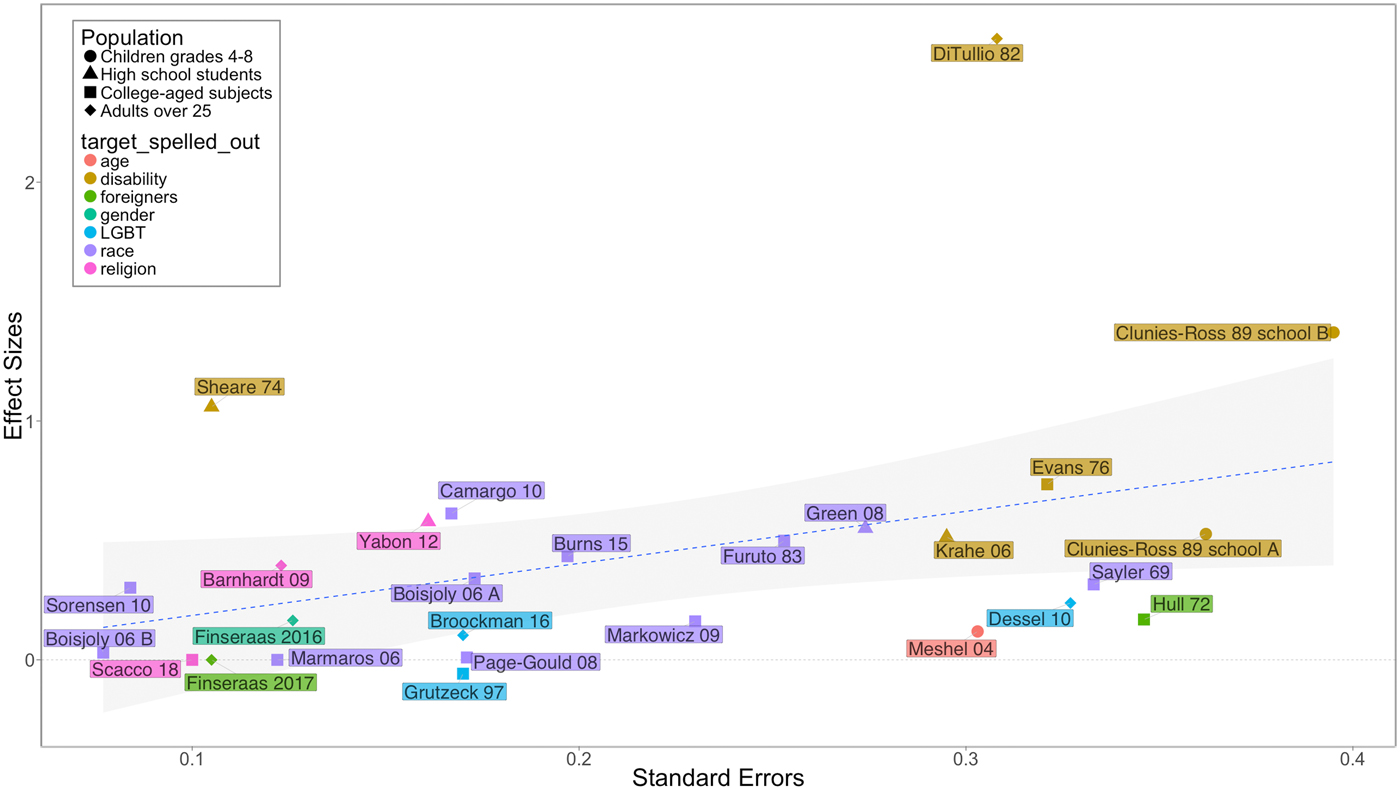

In the years since Allport published his original study, researchers have sought to test out empirically whether contact with other groups can reduce prejudice. In a 2006 paper, Thomas Pettigrew and Linda Tropp conducted a meta-analysis: they reviewed the results of over 500 previous studies—with approximately 250,000 research participants—and found support for the contact hypothesis. Moreover, they found that these results were not due to self-selection (i.e. people who were less prejudiced choosing to have contact with other groups, and people who were more prejudiced choosing to avoid contact), because contact had a beneficial effect even when participants hadn’t chosen whether or not to have contact with members of other groups.

While the contact hypothesis has been studied most often in the context of racial prejudice, the researchers found that contact was able to reduce prejudice against members of a variety of marginalized groups. For example, contact was able to reduce prejudice based on sexual orientation and prejudice against people with disabilities. The researchers also found that contact with members of one group not only reduced prejudice towards that particular group, but reduced prejudice towards members of other groups as well.

What about Allport’s four conditions? The researchers found a larger effect on prejudice reduction when at least one of Allport’s conditions was met. However, even in studies that didn’t meet Allport’s conditions, prejudice was still reduced—suggesting that Allport’s conditions may improve relationships between groups, but they aren’t strictly necessary.

Why Does Contact Reduce Prejudice?

Researchers have suggested that contact between groups can reduce prejudice because it reduces feelings of anxiety (people may be anxious about interacting with members of a group they have had little contact with). Contact may also reduce prejudice because it increases empathy and helps people to see things from the other group’s perspective. According to psychologist Thomas Pettigrew and his colleagues , contact with another group allows people “to sense how outgroup members feel and view the world.”

Psychologist John Dovidio and his colleagues suggested that contact may reduce prejudice because it changes how we categorize others. One effect of contact can be decategorization , which involves seeing someone as an individual, rather than as only a member of their group. Another outcome of contact can be recategorization , in which people no longer see someone as part of a group that they’re in conflict with, but rather as a member of a larger, shared group.

Another reason why contact is beneficial is because it fosters the formation of friendships across group lines.

Limitations and New Research Directions

Researchers have acknowledged that intergroup contact can backfire , especially if the situation is stressful, negative, or threatening, and the group members did not choose to have contact with the other group. In his 2019 book The Power of Human , psychology researcher Adam Waytz suggested that power dynamics may complicate intergroup contact situations, and that attempts to reconcile groups that are in conflict need to consider whether there is a power imbalance between the groups. For example, he suggested that, in situations where there is a power imbalance, interactions between group members may be more likely to be productive if the less powerful group is given the opportunity to express what their experiences have been, and if the more powerful group is encouraged to practice empathy and seeing things from the less powerful group’s perspective.

Can Contact Promote Allyship?

One especially promising possibility is that contact between groups might encourage more powerful majority group members to work as allies —that is, to work to end oppression and systematic injustices. For example, Dovidio and his colleagues suggested that “contact also provides a potentially powerful opportunity for majority-group members to foster political solidarity with the minority group.” Similarly, Tropp—one of the co-authors of the meta-analysis on contact and prejudice— tells New York Magazine’s The Cut that “there’s also the potential for contact to change the future behavior of historically advantaged groups to benefit the disadvantaged.”

While contact between groups isn’t a panacea, it’s a powerful tool to reduce conflict and prejudice—and it may even encourage members of more powerful groups to become allies who advocate for the rights of members of marginalized groups.

Sources and Additional Reading:

- Allport, G. W. The Nature of Prejudice . Oxford, England: Addison-Wesley, 1954. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1954-07324-000

- Dovidio, John F., et al. “Reducing Intergroup Bias Through Intergroup Contact: Twenty Years of Progress and Future Directions.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations , vol. 20, no. 5, 2017, pp. 606-620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217712052

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., et al. “Recent Advances in Intergroup Contact Theory.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations , vol. 35 no. 3, 2011, pp. 271-280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , vol. 90, no. 5, 2006, pp. 751-783. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

- Singal, Jesse. “The Contact Hypothesis Offers Hope for the World.” New York Magazine: The Cut , 10 Feb. 2017. https://www.thecut.com/2017/02/the-contact-hypothesis-offers-hope-for-the-world.html

- Waytz, Adam. The Power of Human: How Our Shared Humanity Can Help Us Create a Better World . W.W. Norton, 2019.

- What Was the Robbers Cave Experiment in Psychology?

- What Is a Microaggression? Everyday Insults With Harmful Effects

- Understanding Social Identity Theory and Its Impact on Behavior

- What Is Deindividuation in Psychology? Definition and Examples

- What Is Social Loafing? Definition and Examples

- Definition of Scapegoat, Scapegoating, and Scapegoat Theory

- What Is Stereotype Threat?

- What Is the Mere Exposure Effect in Psychology?

- Implicit Bias: What It Means and How It Affects Behavior

- What Is Mindfulness in Psychology?

- What's the Difference Between Prejudice and Racism?

- What Is Groupthink? Definition and Examples

- Understanding the Big Five Personality Traits

- Definition and Examples of Social Distance in Psychology

- What Is Flirting? A Psychological Explanation

- What Is a Contact Language?

magazine issue 2 2013 / Issue 17

Justice seems not to be for all: exploring the scope of justice.

written by Aline Lima-Nunes, Cicero Roberto Pereira & Isabel Correia

That human touch that means so much: Exploring the tactile dimension of social life

written by Mandy Tjew A Sin & Sander Koole

Intergroup Contact Theory: Past, Present, and Future

- written by Jim A. C. Everett

- edited by Diana Onu

In the midst of racial segregation in the U.S.A and the ‘Jim Crow Laws’, Gordon Allport (1954) proposed one of the most important social psychological events of the 20th century, suggesting that contact between members of different groups (under certain conditions) can work to reduce prejudice and intergroup conflict . Indeed, the idea that contact between members of different groups can help to reduce prejudice and improve social relations is one that is enshrined in policy-making all over the globe. UNESCO, for example, asserts that contact between members of different groups is key to improving social relations. Furthermore, explicit policy-driven moves for greater contact have played an important role in improving social relations between races in the U.S.A, in improving relationships between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland, and encouraging a more inclusive society in post-Apartheid South Africa. In the present world, it is this recognition of the benefits of contact that drives modern school exchanges and cross-group buddy schemes. In the years since Allport’s initial intergroup contact hypothesis , much research has been devoted to expanding and exploring his contact hypothesis . In this article I will review some of the vast literature on the role of contact in reducing prejudice , looking at its success, mediating factors, recent theoretical extensions of the hypothesis and directions for future research. Contact is of utmost importance in reducing prejudice and promoting a more tolerant and integrated society and as such is a prime example of the real life applications that psychology can offer the world.

The Contact Hypothesis

The intergroup contact hypothesis was first proposed by Allport (1954), who suggested that positive effects of intergroup contact occur in contact situations characterized by four key conditions: equal status, intergroup cooperation , common goals, and support by social and institutional authorities (See Table 1). According to Allport, it is essential that the contact situation exhibits these factors to some degree. Indeed, these factors do appear to be important in reducing prejudice , as exemplified by the unique importance of cross-group friendships in reducing prejudice (Pettigrew, 1998). Most friends have equal status, work together to achieve shared goals, and friendship is usually absent from strict societal and institutional limitation that can particularly limit romantic relationships (e.g. laws against intermarriage) and working relationships (e.g. segregation laws, or differential statuses).

Since Allport first formulated his contact hypothesis , much work has confirmed the importance of contact in reducing prejudice . Crucially, positive contact experiences have been shown to reduce self-reported prejudice (the most common way of assessing intergroup attitudes) towards Black neighbors, the elderly, gay men, and the disabled - to name just a few (Works, 1961; Caspi, 1984; Vonofako, Hewstone, & Voci, 2007; Yuker & Hurley, 1987). Most interestingly, though, in a wide-scale meta-analysis (i.e., a statistical analysis of a number of published studies), it has been found that while contact under Allport’s conditions is especially effective at reducing prejudice , even unstructured contact reduces prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). What this means is that Allport’s proposed conditions should be best be seen as of a facilitating, rather than an essential, nature. This is important as it serves to show the importance of the contact hypothesis : even in situations which are not marked by Allport’s optimal conditions, levels of contact and prejudice have a negative correlation with an effect size comparable to those of the inverse relationship between condom use and sexually transmitted HIV and the relationship between passive smoking and the incidence of lung cancer at work (Al-Ramiah & Hewstone, 2011). Contact between groups, even in sub-optimal conditions, is strongly associated with reduced prejudice .

Importantly, contact does not just influence explicit self-report measures of prejudice , but also reduces prejudice as measured in a number of different ways. Explicit measures (e.g. ‘How much do you like gay men?’) are limited in that there can be a self-report bias: people often answer in a way that shows them in a good light. As such, research has examined the effects of contact on implicit measures: measures that involve investigating core psychological constructs in ways that bypass people’s willingness and ability to report their feelings and beliefs. Implicit measures have been shown to be a good complement to traditional explicit measures - particularly when there may be a strong chance of a self-report bias. In computer reaction time tasks, contact has been shown to reduce implicit associations between the participant’s own in-group and the concept ‘good’, and between an outgroup (a group the participant is not a member of) and the concept ‘bad’ (Aberson and Haag, 2007). Furthermore, positive contact is associated with reduced physiological threat responses to outgroup members (Blascovich et al., 2001), and reduced differences in the way that faces are processed in the brain, implying that contact helps to increase perceptions of similarity (Walker et al., 2008). Contact, then, has a real and tangible effect on reducing prejudice – both at the explicit and implicit level. Indeed, the role of contact in reducing prejudice is now so well documented that it justifies being referred to as intergroup contact theory (Hewstone & Swart, 2011).

How does it work?

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to explain just how contact reduces prejudice . In particular, “four processes of change” have been proposed: learning about the out-group , changing behavior, generating affective ties, and in-group reappraisal (Pettigrew, 1998). Contact can, and does, work through both cognitive (i.e. learning about the out-group , or reappraising how one thinks about one’s own in-group ), behavioural (changing one’s behavior to open oneself to potential positive contact experiences), and affective (generating affective ties and friendships, and reducing negative emotions) means. A particularly important mediating mechanism (i.e. the mechanisms or processes by which contact achieves its effect) is that of emotions, or affect, with evidence suggesting that contact works to reduce prejudice by diminishing negative affect (anxiety / threat) and inducing positive affect such as empathy (Tausch and Hewstone, 2010). In another meta-analysis , Pettigrew and Tropp (2008) supported this by looking specifically at mediating mechanisms in contact and found that contact situations which promote positive affect and reduce negative affect are most likely to succeed in conflict reduction. Contact situations are likely to be effective at improving intergroup relations insofar as they induce positive affect, and ineffective insofar as they induce negative affect such as anxiety or threat. If we feel comfortable and not anxious, the contact situation will be much more successful.

Generalizing the effect

An important issue that I have not yet addressed, however, is how these positive experiences after contact can be extended and generalized to other members of the outgroup . While contact may reduce an individual’s prejudice towards (for example) their Muslim colleague, its practical use is strongly limited if it doesn’t also diminish prejudice towards other Muslims. Contact with each and every member of an outgroup – let alone of all out-groups to which prejudice is directed – is clearly unfeasible and so a crucial question in intergroup contact research is how the positive effect can be generalized.

A number of approaches have been developed to explain how the positive effect of contact, including making group saliency low so that people focus on individual characteristics and not group-level attributes (Brewer & Miller, 1984), making group saliency high so that the effect is best generalized to others (Johnston & Hewstone, 1992), and making an overarching common ingroup identity salient (Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, & Rust, 1993). Each of these approaches have both advantages and disadvantages, and in particular each individual approach may be most effective at different stages of an extended contact situation. To deal with this issue Pettigrew (1998) proposed a three stage model to take place over time to optimize successful contact and generalization. First is the decategorization stage (as in Brewer & Miller, 1984), where participants’ personal (and not group) identities should be emphasized to reduce anxiety and promote interpersonal liking. Secondly, the individuals’ social categories should be made salient to achieve generalization of positive affect to the outgroup as a whole (as in Johnston & Hewstone, 1992). Finally, there is the recategorization stage, where participants’ group identities are replaced with a more superordinate group: changing group identities from ‘Us vs. Them’ to a more inclusive ‘We’ (as in Gaertner et al., 1993). This stage model could provide an effective method of generalizing the positive effects of intergroup contact.

Theoretical Extensions

Even with such work on generalization, however, it may still be unrealistic to expect that group members will have sufficient opportunities to engage in positive contact with outgroup members: sometimes positive contact between group members is incredibly difficult, if not impossible. For example, at the height of the Northern Ireland conflict, positive contact between Protestants and Catholics was nigh on impossible. As such, recent work on the role of intergroup contact in reducing prejudice has moved away from the idea that contact must necessarily include direct (face-to-face) contact between group members and instead includes the notion that indirect contact (e.g. imagined contact, or knowledge of contact among others) may also have a beneficial effect.

A first example of this approach comes from Wright, Aron, McLaughlin-Volpe, and Ropp’s (1997) extended contact hypothesis . Wright et al. propose that mere knowledge that an ingroup member has a close relationship with an outgroup member can improve outgroup attitudes, and indeed this has been supported by a series of experimental and correlational studies. For example, Shiappa, Gregg, & Hewes, (2005) have offered evidence suggesting that just watching TV shows that portrayed intergroup contact was associated with lower levels of prejudice . A second example of an indirect approach to contact comes from Crisp and Turner’s (2009) imagined contact hypothesis , which suggests that actual experiences may not be necessary to improve intergroup attitudes, and that simply imagining contact with outgroup members could improve outgroup attitudes. Indeed, this has been supported in a number of studies at both an explicit and implicit level: British Muslims (Husnu & Crisp, 2010), the elderly (Abrams, Crisp, & Marques 2008), and gay men (Turner, Crisp, & Lambert, 2007).

These more recent extensions of the contact hypothesis have offered important suggestions on how to most effectively generalize the benefits of the contact situation and make use of findings from work on mediating mechanisms. It seems that direct face-to-face contact is always not necessary, and that positive outcomes can be achieved by positive presentation of intergroup-friendships in the media and even simply by imagining interacting with an outgroup member.

Issues and Directions for Future Research

Contact, then, has important positive effects on improved intergroup relations. It does have its critics, however. Notably, Dixon, Durrheim, & Tredoux (2005) argue that while contact has been important in showing how we can promote a more tolerant society, the existing literature has an unfortunate absence of work on how intergroup contact can affect societal change: changes in outgroup attitudes from contact do not necessarily accompany changes in the ideological beliefs that sustain group inequality. For example, Jackson and Crane (1986) demonstrated that positive contact with Black individuals improved Whites’ affective reactions towards Blacks but did not change their attitudes towards policy in combating inequality in housing, jobs and education. Furthermore, contact may also have the unintended effect of weakening minority members’ motivations to engage in collective action aimed at reducing the intergroup inequalities. For example, Dixon, Durrheim, & Tredoux (2007) found that the more contact Black South Africans had with White South Africans, the less they supported policies aimed at reducing racial inequalities. Positive contact may have the unintended effect of misleading members of disadvantaged groups into believing inequality will be addressed, thus leaving the status differentials intact. As such, a fruitful direction for future research would be to investigate under what conditions contact could lead to more positive intergroup relations without diminishing legitimate protest aimed at reducing inequality. One promising suggestion is to emphasize commonalities between groups while also addressing unjust group inequalities during the contact situation. Such a contact situation could result in prejudice reduction without losing sight of group inequality (Saguy, Tausch, Dovidio, & Pratto, 2009).

A second concern with contact research is that while contact has shown to be effective for more prejudiced individuals, there can be problems with getting a more prejudiced individual into the contact situation in the first place. Crisp and Turner’s imagined contact hypothesis seems to be a good first step in tackling this problem (Crisp & Turner, 2013), though it remains to be seen if, and how, such imagined contact among prejudiced individuals can translate to direct contact. Greater work on individual differences in the efficacy of contact would provide an interesting contribution to existing work.

Conclusions

Contact, then, has been shown to be of utmost importance in reduction of prejudice and promotion of more positive intergroup attitudes. Such research has important implications for policy work. Work on contact highlights the importance of institutional support and advocation of more positive intergroup relations, the importance of equal status between groups, the importance of cooperation between groups and the importance of positive media presentations of intergroup friendships - to name just a few. As Hewstone and Swart (2011) argue,

“Theory-driven social psychology does matter, not just in the laboratory, but also in the school, the neighborhood, and the society at large” (Hewstone & Swart, 2011. p.380).

- Aberson, C. L., & Haag, S. C. (2007). Contact, perspective taking, and anxiety as predictors of stereotype endorsement, explicit attitudes, and implicit attitudes. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 10 , 179–201.

- Abrams, D. and Crisp, R.J. & Marques, S., (2008). Threat inoculation: Experienced and Imagined intergenerational contact prevent stereotype threat effects on older peoples math performance. Psychology and Aging, 23 (4), 934-939.

- Al Ramiah, A., & Hewstone, M. (2011). Intergroup difference and harmony: The role of intergroup contact. In P. Singh, P. Bain, C-H. Leong, G. Misra, and Y. Ohtsubo. (Eds.), Individual, group and cultural processes in changing societies. Progress in Asian Social Psychology (Series 8), pp. 3-22. Delhi: University Press.

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice . Cambridge/Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Aronson, E., & Patnoe, S. (1997). The jigsaw classroom: Building cooperation in the classroom (Vol. 978, p. 0673993830). New York: Longman.

- Blascovich, J., Mendes, W. B., Hunter, S. B., Lickel, B., & Kowai-Bell, N. (2001). Perceiver threat in social interactions with stigmatized others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 253–267.

- Brewer, M. B., & Kramer, R. M. (1985). The psychology of intergroup attitudes and behavior. Annual review of psychology, 36 (1), 219-243.

- Brewer, M. B., & Miller, N. (Eds.). (1984). Groups in contact: The psychology of desegregation. Academic Press.

- Caspi, A. (1984). Contact hypothesis and inter-age attitudes: A field study of cross-age contact. Social Psychology Quarterly, 74-80.

- Chu, D., & Griffey, D. (1985). The contact theory of racial integration: The case of sport. Sociology of Sport Journal, 2 (4), 323-333.

- Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (1995). Producing equal-status interaction in the heterogeneous classroom. American Educational Research Journal, 32 (1), 99-120.

- Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2009). Can imagined interactions produce positive perceptions? Reducing prejudice through simulated social contact. American Psychologist, 64, 231–240.

- Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2013). Imagined intergroup contact: Refinements, debates and clarifications. In G. Hodson & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Advances in intergroup contact. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Dixon, J., Durrheim, K., & Tredoux, C. (2005). Beyond the optimal contact strategy: A reality check for the contact hypothesis . American Psychologist, 60, 697–711.

- Dixon, J., Durrheim, K., & Tredoux, C. (2007). Intergroup contact and attitudes toward the principle and practice of racial equality. Psychological Science, 18, 867–872.

- Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., & Rust, M. C. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. European Review of Social Psychology, 4 (1), 1-26.

- Hewstone, M., & Swart, H. (2011). Fifty-odd years of inter-group contact: From hypothesis to integrated theory. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50 (3), 374-386.

- Husnu, S. & Crisp, R. J. (2010). Elaboration enhances the imagined contact effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 943-950

- Jackman, M.R., & Crane, M. (1986). “Some of my best friends are black...”: interracial friendship and whites’ racial attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly 50, pp. 459–86

- Johnston, L., & Hewstone, M. (1992). Cognitive models of stereotype change: 3. Subtyping and the perceived typicality of disconfirming group members. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28 (4), 360-386.

- Landis D., Hope R.O., & Day H.R. (1984). Training for desegregation in the military. In N. Miller & M. B. Brewer 1984, Groups in Contact: The Psychology of Desegregation, pp. 257–78. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Miller, N., & Brewer M. B., eds. (1984). Groups in Contact: The Psychology of Desegregation. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual review of psychology, 49 (1), 65-85.

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta- analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 (5), 751.

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice ? Meta- analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38 (6), 922-934.

- Saguy, T., Tausch, N., Dovidio, J. F., & Pratto, F. (2009). The irony of harmony: Intergroup contact can produce false expectations for equality. Psychological Science, 20 , 114–121.

- Schiappa, E., Gregg, P. B., & Hewes, D. E. (2006). Can One TV Show Make a Difference? Will & Grace and the Parasocial Contact Hypothesis . Journal of Homosexuality, 51 (4), 15-37.

- Tausch, N., & Hewstone, M. (2010). Intergroup contact and prejudice . In J. F. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, P. Glick, & V. M. Esses (Eds.), The Sage handbook of prejudice , stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 544–560). Newburg Park, CA: Sage.

- Turner, R. N., Crisp, R. J., & Lambert, E. (2007). Imagining intergroup contact can improve intergroup attitudes. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 10 , 427-441.

- Vonofakou, C., Hewstone, M., & Voci, A. (2007). Contact with outgroup friends as a predictor of meta-attitudinal strength and accessibility of attitudes towards gay men. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92 , 804–820.

- Works, E. (1961).The prejudice -interaction hypothesis from the point of view of the Negro minority group. American Journal of Sociology. 67 : 47–52

- Wright, S. C., Aron, A., McLaughlin-Volpe, T., & Ropp, S. A. (1997). The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73 , 73–90.

- Yuker, H. E., & Hurley, M. K. (1987). Contact with and attitudes toward persons with disabilities: The measurement of intergroup contact. Rehabilitation Psychology, 32 (3), 145.

From the editors

Everett (2013) presents an excellent overview of the research on Intergroup Contact Theory and how psychologists have used it to understand prejudice and conflict. As the article notes, friendship between members of different groups is one form of contact that helps dissolve inter-group conflict. Friendships are beneficial because of “self-expansion,” which is a fundamental motivational process that drives people to grow and integrate new things into their lives (Aron, Norman, & Aron, 1998). When an individual learns something or experiences something for the first time, his/her mind literally grows. When friendships are very intimate, people include aspects of their friends in their own self-concept (Aron, Aron, Tudor, & Nelson, 1991).

For example, if Scott (an American) becomes friends with Dan (a Russian), Scott might grow to appreciate Russian culture, because of their intimacy. Even the word “Russian” is now part of Scott’s own self-concept through this friendship, and Scott will have more positive feelings and attitudes toward Russians as a group. The same process happens for all kinds of other groups based race/ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, etc.

Importantly, self-expansion and intimacy through friendship do not work like magic; psychologists can’t wave a wand and make them appear. Nor does it happen through superficial small talk (e.g., “how about this crazy weather?”). Intimacy develops through deep communication: sustained, reciprocal, escalating conversations in which two friends come to know each other in a meaningful way. A Christian person might say, “I have a Jewish co-worker” (while talking about a casual acquaintance) or a Caucasian person might say, “I give money to an organization that helps starving people in Africa” or a straight person might say, “I support same-sex marriage equality because I know someone who is gay.” All of that is good, but it’s not as effective at reducing inter-group conflict as a true friendship with someone in those other groups; superficial contact has a small effect on racism, anti-Semitism, or homophobia. A recent meta-analysis (Davies, Tropp, Aron, Pettigrew, & Wright, 2011) revealed that spending lots of time with cross-group friends and having lots of in-depth communication with those friends were the two strongest predictors of change in positive attitudes and prejudice reduction.

At In-Mind, we work in a transnational team and we think this is enriching. What about you? Have you found friendships, or even working relations, across social groups? Did this lead you to have more open or positive attitudes? Or, do you have other experiences?

article author(s)

Jim A. C. Everett

Jim Everett studied for his undergraduate at the University of Oxford, gaining a First Class degree in Psychology, Philosophy, and Physiology. He completed... more

article keywords

- discrimination

- intergroup contact hypothesis

article glossary

- intergroup conflict

- recognition

- Intergroup Contact Hypothesis

- contact hypothesis

- cooperation

- meta-analysis

- stereotypes

- stereotype threat

- field study

Intergroup Contact Theory: Recent Developments and Future Directions

- Published: 17 August 2018

- Volume 31 , pages 374–385, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Ashley Lytle 1

3749 Accesses

15 Citations

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice . Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Google Scholar

Barlow, F. K., Paolini, S., Pedersen, A., Hornsey, M. J., Radke, H. M., Harwood, J., et al. (2012). The contact caveat: Negative contact predicts increased prejudice more than positive contact predicts reduced prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38 (12), 1629–1643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212457953 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., Roberts, H., & Zuckerman, E. (2017). Study: Breitbart-led right-wing media ecosystem altered broader media agenda. Retrieved June 2, 2018 from http://www.cjr.org/analysis/breitbart-media-trump-harvard-study.php .

Brown, R., & Hewstone, M. (2005). An integrative theory of intergroup contact. In M. P. Zanna & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 37, pp. 255–343). San Diego, CA, US: Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/s00652601(05)37005-5 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Davies, K., Tropp, L. R., Aron, A., Pettigrew, T. F., & Wright, S. C. (2011). Cross-group friendships and intergroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15 (4), 332–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311411103 .

Eller, A., & Abrams, D. (2003). ‘Gringos’ in Mexico: Cross-sectional and longitudinal effects of language school-promoted contact on intergroup bias. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 6 (1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430203006001012 .

Article Google Scholar

Fein, S., & Spencer, S. J. (2000). Prejudice as self-image maintenance: Affirming the self through derogating others. In C. Stangor & C. Stangor (Eds.), Stereotypes and prejudice: Essential readings (pp. 172–190). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press.

Hayward, L. E., Tropp, L. R., Hornsey, M. J., & Barlow, F. K. (2018). How negative contact and positive contact with whites predict collective action among racial and ethnic minorities. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57 (1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12220 .

Hodson, G. (2008). Interracial prison contact: The pros for (socially dominant) cons. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47 (2), 325–351. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466607X231109 .

Hodson, G. (2011). Do ideologically intolerant people benefit from intergroup contact? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20 (3), 154–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411409025 .

Kim, N., & Wojcieszak, M. (2018). Intergroup contact through online comments: Effects of direct and extended contact on outgroup attitudes. Computers in Human Behavior, 8163, 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.013 .

Lazer, D. (2015). The rise of the social algorithm: Does content curation by Facebook introduce ideological bias? Science, 348 (6239), 1090–1091. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab1422 .

Lemmer, G., & Wagner, U. (2015). Can we really reduce ethnic prejudice outside the lab? A meta-analysis of direct and indirect contact interventions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45 (2), 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2079 .

Lytle, A., Dyar, C., Levy, S. R., & London, B. (2017). Essentialist beliefs: Understanding contact with and attitudes towards lesbian and gay individuals. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56 (1), 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12154 .

Martens, A., Johns, M., Greenberg, J., & Schimel, J. (2006). Combating stereotype threat: The effect of self-affirmation on women’s intellectual performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42 (2), 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.04.010 .

McGregor, I., Haji, R., & Kang, S. (2008). Can ingroup affirmation relieve outgroup derogation? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44 (5), 1395–1401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.06.001 .

Miles, E., & Crisp, R. J. (2014). A meta-analytic test of the imagined contact hypothesis. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 17 (1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430213510573 .

Paolini, S., Harwood, J., & Rubin, M. (2010). Negative intergroup contact makes group memberships salient: Explaining why intergroup conflict endures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36 (12), 1723–1738. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210388667 .

Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact: Theory, research and new perspectives. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65 .

Pettigrew, T. F. (2008). Future directions for intergroup contact theory and research. International Journal Of Intercultural Relations , 32 (3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.12.002 .

Pettigrew, T. F., Christ, O., Wagner, U., & Stellmacher, J. (2007). Direct and indirect intergroup contact effects on prejudice: A normative interpretation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31 (4), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.11.003 .

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 (5), 751–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751 .

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38 (6), 922–934. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.504 .

Reimer, N. K., Becker, J. C., Benz, A., Christ, O., Dhont, K., Klocke, U., et al. (2017). Intergroup contact and social change: Implications of negative and positive contact for collective action in advantaged and disadvantaged groups: Erratum. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43 (6), 901–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217703392 .

Rosenthal, L. (2016). Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: An opportunity to promote social justice and equity. American Psychologist, 71 (6), 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040323 .

Rosenthal, L., & Levy, S. R. (2016). Endorsement of polyculturalism predicts increased positive intergroup contact and friendship across the beginning of college. Journal of Social Issues, 72 (3), 472–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12177 .

Saguy, T., & Kteily, N. (2014). Power, negotiations, and the anticipation of intergroup encounters. European Review of Social Psychology, 25 (1), 107–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2014.957579 .

Saguy, T., Tausch, N., Dovidio, J. F., & Pratto, F. (2009). The irony of harmony: Intergroup contact can produce false expectations for equality. Psychological Science, 20 (1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02261.x .

Sherman, D. K., Brookfield, J., & Ortosky, L. (2017). Intergroup conflict and barriers to common ground: A self-affirmation perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass . https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12364 .

Sherman, D. K., & Hartson, K. (2011). Reconciling self-defense with self-criticism: Self affirmation theory. In M. Alicke & C. Sedikides (Eds.), The handbook of self enhancement and self-protection (pp. 128–151). New York: Guilford Press.

Turner, R. N., & Crisp, R. J. (2010). Imagining intergroup contact reduces implicit prejudice. British Journal of Social Psychology, 49 (1), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466609X419901 .

Turner, R. N., Dhont, K., Hewstone, M., Prestwich, A., & Vonofakou, C. (2014). The role of personality factors in the reduction of intergroup anxiety and amelioration of outgroup attitudes via intergroup contact. European Journal of Personality, 28 (2), 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1927 .

Vezzali, L., Andrighetto, L., Di Bernardo, G. A., Nadi, C., & Bergamini, G. (2017). Negative intergroup contact and support for social policies toward the minority outgroup in the aftermath of a natural disaster. The Journal of Social Psychology, 157 (4), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2016.1184126 .

Vezzali, L., Andrighetto, L., Saguy, T. (2016). When intergroup contact can backfire: The content of intergroup encounters and desire for equality (under review).

Wright, S. C., Aron, A., McLaughlin-Volpe, T., & Ropp, S. A. (1997). The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73 (1), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.73 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Arts and Letters, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ, USA

Ashley Lytle

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ashley Lytle .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lytle, A. Intergroup Contact Theory: Recent Developments and Future Directions. Soc Just Res 31 , 374–385 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0314-9

Download citation

Published : 17 August 2018

Issue Date : December 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-018-0314-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

This page has been archived and is no longer being updated regularly.

All you need is contact

November 2001, Vol 32, No. 10

A longstanding line of research that aims to combat bias among conflicting groups springs from a theory called the "contact hypothesis." Developed in the 1950s by Gordon Allport, PhD, the theory holds that contact between two groups can promote tolerance and acceptance, but only under certain conditions, such as equal status among groups and common goals. Since the theory's inception, psychologists have added more and more criteria to what is required of groups in order for "contact" to work.

Recently, however, University of California, Santa Cruz research psychologist Thomas Pettigrew, PhD, has turned this research finding on its head. In a new meta-analysis of 500 studies, he finds that all that's needed for greater understanding between groups is contact, period, in all but the most hostile and threatening conditions. There is, however, a larger positive effect if some of the extra conditions are met.

His analysis turned up another unexpected finding that also runs counter to the direction of the field. The reason contact works, his analysis finds, is not purely or even mostly cognitive, but emotional.

"Your stereotypes about the other group don't necessarily change," Pettigrew explains, "but you grow to like them anyway."

Pettigrew is currently submitting his study for review; the basic findings can also be found in a chapter by him and Linda Tropp, PhD, in the book "Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination" (Erlbaum, 2000).

--T. DeANGELIS

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

- Memberships

Contact Hypothesis theory explained

Contact Hypothesis Theory: this article explains the Contact Hypothesis Theory in a practical way. Next to what it is, this article also highlights the intergroup contact and prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination, the conditions and contact hypothesis examples. After reading you will understand the basics of this psychology theory. Enjoy reading!

What is the Contact Hypothesis?

The contact hypothesis is a psychology theory suggesting that prejudice and conflict between groups can be reduced by allowing members of those groups to interact with one another. This notion is also called intra-group contact. Prejudice and conflict usually arise between majority and minority group members.

The background to the contact hypothesis

Social psychologist Gordon Allport is credited with conducting the first studies on intergroup contact.

Allport is also known for this research in the field of personalities . After the Second World War, social scientists and policymakers concentrated mainly on interracial contact. Allport brought these studies together in his study of intergroup contact.

In 1954, Allport published his first hypothesis concerning intergroup contact in the journal of personality and social psychology. The main premise of his article stated that intergroup contact was one of the most effective ways to reduce prejudice between groups.

Allport claimed that contact management and interpersonal contact could produce positive effects against with stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination, leading to better and more worthwhile interaction between two or more groups.

Over the years since Allport’s original article, the hypothesis has been expanded by social scientists and used for research into reducing prejudice relating to racism, disability, women and LGBTQ + people.

Empirical and meta analytical research into intergroup contact is still ongoing today.

Intergroup contact and prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination

The term “prejudice” is used to refer to a preconceived, negative view of another person, based on perceived qualities such as political affiliation, skin colour, faith, gender, disability, religion, sexuality, language, height, education, and more.

Prejudice can also refer to an unfounded belief, or to pigeonhole people or groups. Gordon Allport, the originator of the contact hypothesis, defined prejudice as a feeling, positive or negative, prior to actual experience, that is not based on fact.

Stereotypes, as defined in the contact hypothesis, are generalisations about groups of people. Stereotypes are often based on sexual orientation, religion, race, or age. Stereotypes can be positive, but are usually negative. Either way, a stereotype is a generalisation that does not take into account differences at the individual level.

Prejudice and stereotypes concern biased views regarding others, but discrimination consists of targeted action against individuals or groups based on race, religion, gender or other identifying features. Discrimination takes many forms, from pay gaps and glass ceilings to unfair housing policies.

In recent years, more and more new legislation and regulations have been introduced, designed to tackle discrimination and prejudice reduction in, for example, the workplace. It is not however possible to eliminate discrimination through legislation. Discrimination is a complex issue relating to the justice, education and political systems in a society.

Conditions for intergroup contact to reduce prejudice

Gordon Allport claimed that prejudice and conflict between groups can be reduced by having equal status contact between groups in pursuit of common goals. This effect is even greater when contact is officially sanctioned.

This can be achieved through legislation, but also through local customs and practice. In other words, there are four conditions under which prejudice can be reduced. These are:

Equal status

Both groups taking part in the contact situations must play equal roles in the relationship. The members of each group should have similar backgrounds, qualities and other features. Differences in academic background, prosperity or experience should be kept to a minimum.

Common goals

Both groups should seek to serve a higher purpose through the relationship and working together. This is a goal which can only be achieved when the two groups join forces and work together on common initiatives.

Working together

Both groups should work together to achieve their common goals, rather than in competition.

Support from the authorities through legislation

Both groups should recognise a single authority, to support contact and collaborative interaction between groups. This contact should be helpful, considerate, and foster the right attitude towards one another.

Examples of the contact hypothesis

The effect of greater contact between members of disparate groups has been the basis of many policy decisions advocating racial integration in settings such as schools, housing, workplaces and the military.

The contact hypothesis in the desegregation of education

An example of this is a 1954 landmark court decision by the US Supreme Court. The decision brought about the desegregation of schools. In this ruling, the contact hypothesis was used to demonstrate that this would increase self-esteem among racial minorities and respect between groups in general.

Studies into the implications of this decision in subsequent years did not always yield positive results. There have been studies showing that prejudice was actually reinforced and that self-esteem did not improve among minorities. The reason for this has already been set out above.

Contact between groups in schools, for example, was not always equal, nor did it take place with social supervision. These are two essential requirements or conditions for improving relationships between disparate groups.

The contact hypothesis in developing education strategies

The contact hypothesis has also proved invaluable in developing cooperative education strategies. The best known of these is the jigsaw classroom technique. This technique involves creating a particular classroom setting where students from various racial backgrounds are brought together in pursuit of a common goal.

In practice this means that students are placed in study groups of 6. The lesson is split into six elements, and each student is assigned one part of those six. That means that each student actually represents one piece in that jigsaw.

For the lesson to succeed, students need to trust one another based on their knowledge. This increases interdependence within the group, which is necessary for improving relationships between people.

Reducing prejudice

Besides it being very important to know how prejudice arises, studies on prejudice also focus on the potential to reduce prejudice. One technique widely believed to be highly effective is training people to become more empathetic towards members of other groups.

Putting yourself in someone else’s shoes makes it easier to think about what you would do in a similar situation.

Other techniques and methods used to reduce prejudice are:

- Contact with members of other groups

- Making others aware of the inconsistencies in their beliefs and values

- Legislation and regulations which promote fair and equal treatment of people in minority groups

- Creating public support and awareness

Implication of prejudice and discrimination in the workplace

Discrimination and prejudice can lead to wellbeing issues and substantial financial loss to the organisation, along with a sharp fall in employee and company morale. According to the American Psychological Association, 61% of adults face prejudice or discrimination at some time.

For some this happens at work; others face it as part of everyday life in society. Most people are aware of the negative effects this can have on employees, but discrimination and prejudice going unchecked can also have serious consequences.

Firstly, treating people unfairly can contribute to increased stress levels. This in turn leads to more wellbeing issues for those who are personally harmed or attacked. When someone is constantly worrying about discrimination or religion, he or she is forced to think about that thing all day long. Too much stress reduces sleep quality and suppresses appetite. When this becomes the norm for someone, they are going to feel chronically ill or down.

Prejudice also has a negative effect on the company in general. Companies may even suffer financial loss as a consequence. Employees who feel ill or down because of social issues are more likely to resign. The company then incurs substantial costs training new people.

Another obvious negative outcome for organisations is employees who hate management if they feel they are not being treated fairly. This negative attitude from employees has an effect on individual employee performance and ultimately also on the performance of the organisation as a whole.

The contact hypothesis in summary

The contact hypothesis, of which the intergroup contact theory is a part, is a theory from sociology and psychology which suggests that problems such as discrimination and prejudice can be drastically reduced by having more contact with people from different social groups. This notion is also called intergroup contact. Prejudice and conflict usually arise between majority and minority group members.

The social psychologist credited for his contributions in this field is Gordon Allport. Allport brought together several studies of interracial contact after the Second World War and developed the intergroup contact theory from those. His hypothesis was published in 1954. In the decades which followed, the theory was widely used in initiatives to tackle these social problems.

Prejudice is often a negative evaluation of others based on qualities such as political affiliation, age, skin colour, height, gender or other identifying features. Stereotyping resembles prejudice, but is in fact making generalisations about groups of people.

This social failing is also based on religion, gender or other identifying features which say nothing about the group as a whole. Discrimination goes a step further than prejudice and stereotypes. Discrimination is about actually treating people in a negative way based on particular identifying features such as race or education.

Gordon Allport developed four requirements or conditions necessary for reducing prejudice through increased intergroup contact. The first is that both groups should have an equal status. The members of each group should have similar backgrounds, qualities or social status.

Differences in academic background, prosperity or experience should be kept to a minimum. The second is to have common goals. The groups should not be brought together without some purpose. As mentioned too in the example above in the jigsaw classroom section, dependence on one another is stimulating, which is a prerequisite for social equality and improved relationships. This is linked to the third condition: working together.

Now it is your turn

What do you think? Are you familiar with the explanation of the contact hypothesis? Have you ever faced prejudice or discrimination? Have you ever experienced the positive effects of contact? Had you ever heard of this theory before? Do you think eliminating discrimination and prejudice is possible? What is your view on opportunity of outcome vs opportunity of equality? Do you have any other advice or additional comments?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Amir, Y. (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations . Psychological bulletin, 71(5), 319.

- Brewer, M. B., & Miller, N. (1984). Beyond the contact hypothesis: Theoretical . Groups in contact: The psychology of desegregation, 281.

- Paluck, E. L., Green, S. A., & Green, D. P. (2019). The contact hypothesis re-evaluated . Behavioural Public Policy, 3(2), 129-158.

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2005). Allport’s intergroup contact hypothesis: Its history and influence . On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport, 262-277.

How to cite this article: Janse, B. (2021). Contact Hypothesis Theory . Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/psychology/contact-hypothesis/

Original publication date: 05/25/2021 | Last update: 08/21/2023

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/psychology/contact-hypothesis/”>Toolshero: Contact Hypothesis Theory</a>

Did you find this article interesting?

Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4.2 / 5. Vote count: 13

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Ben Janse is a young professional working at ToolsHero as Content Manager. He is also an International Business student at Rotterdam Business School where he focusses on analyzing and developing management models. Thanks to his theoretical and practical knowledge, he knows how to distinguish main- and side issues and to make the essence of each article clearly visible.

Related ARTICLES

Victor Vroom biography and books

Friedrich Engels biography, quotes and books

Relative Deprivation Theory by Garry Runciman

Social Learning Theory by Albert Bandura

Respondents: the definition, meaning and the recruitment

Social Intelligence (SI) explained

Also interesting.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Herzberg Two Factor Theory of Motivation

Psychological Safety by Amy Edmondson

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BOOST YOUR SKILLS

Toolshero supports people worldwide ( 10+ million visitors from 100+ countries ) to empower themselves through an easily accessible and high-quality learning platform for personal and professional development.

By making access to scientific knowledge simple and affordable, self-development becomes attainable for everyone, including you! Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero.

POPULAR TOPICS

- Change Management

- Marketing Theories

- Problem Solving Theories

- Psychology Theories

ABOUT TOOLSHERO

- Free Toolshero e-book

- Memberships & Pricing

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

The contact hypothesis reconsidered: interacting via internet, conditions and challenges of the contact hypothesis, practicality and contact, anxiety in contact, generalization from contact, the net advantage, ameliorating anxiety through online interaction, supersize it: generalizing from the contact to the group, getting more than just skin deep, beyond the cookie-cutter contact: tailoring the net contact to fit specific needs, conclusions, about the authors.

- < Previous

The Contact Hypothesis Reconsidered: Interacting via the Internet

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Yair Amichai-Hamburger, Katelyn Y. A. McKenna, The Contact Hypothesis Reconsidered: Interacting via the Internet, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , Volume 11, Issue 3, 1 April 2006, Pages 825–843, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00037.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

One of the leading theories advocated for reducing intergroup conflict is the contact hypothesis. According to this theory, contact under certain conditions, such as equal status, cooperation towards a superordinate goal, and institutional support, will create a positive intergroup encounter, which, in turn, will bring about an improvement in intergroup relations. Despite its promise, the contact hypothesis appears to suffer from three major defects: (1) practicality—creating a contact situation involves overcoming some serious practical obstacles; (2) anxiety—the anxiety felt by the participants may cause a contact to be unsuccessful or at least not reach its potential; (3) generalization—the results of a contact, however sucessful, tend to to be limited to the context of the meeting and to the participants. The Internet has, in recent years, become an accessible and important medium of communication. The Internet creates a protected environment for users where they have more control over the communication process. This article suggests that the Internet’s unique qualities may help in the creation of positive contact between rival groups. The major benefits of using the Internet for contact are examined in this article.

The contact hypothesis has been described as one of the most successful ideas in the history of social psychology ( Brown, 2000 ). Allport (1954) presented the first widely-accepted outline of the contact hypothesis, claiming that true acquaintance lessens prejudice. In other words, knowledge, on its own, will not cause people to negate their prejudices and stereotypes about others, since they are very likely to accept only those pieces of information that fit into their preconceived schema of the world. It is through getting to know the other that people may be able to break down their stereotypes of him or her.

The Internet has, to date, been perhaps the most successful means of facilitating and enabling contact among individuals—particularly those who otherwise would not have had the opportunity, nor perhaps the inclination, to meet ( McKenna & Bargh, 2000 ). As we will argue here, the Internet is uniquely suited to the implementation of the various requirements of the contact hypothesis that are necessary for consistently producing successful outcomes. Indeed, the Internet may be the best tool yet for effectively putting the contact hypothesis into practice.

The article begins with a brief overview of the requirements necessary to create an ideal and successful contact situation and the challenges to putting these requirements into practice in traditional settings. We then discuss the ways in which the Internet can be used to meet these challenges and, in some areas, do so more successfully than can be achieved through traditional interaction contexts (e.g., in person, over the phone). We conclude with a short section providing ideas for how various aspects of the online contact environment and interaction process can be tweaked to fit specific situational needs and to improve the chances for a successful contact to occur.

Under ideal circumstances, when a member of a majority group meets with a minority group member and the experience is a positive one, an attitude change on two levels will result ( Allport, 1954 ). First, there will be an attitude change that is target-specific. That is, initial assumptions about the other that arise from the (negative) stereotypes associated with his or her group are replaced by more positive perceptions of the individual. Second, these new positive associations with the individual will become extended to that individual’s group as a whole, thus ameliorating negative attitudes toward the group. Allport delineated four key conditions for such a meeting: equal-group status within the situation; common goals; intergroup cooperation; and institutional support. Several other conditions were later added, the most important of these being voluntary participation and intimate contact ( Amir, 1969 , 1976 ).

There is strong empirical support demonstrating that, when effectively implemented, the conditions described above do indeed lead to a positive attitude change that is target-specific (e.g., Brown & Wade, 1987 ; Hewstone & Brown, 1986 ; Riordan & Ruggiero, 1980 ). The evidence is less clear regarding a global attitude change toward the group, however. A majority of studies do not find that the positive attitude toward the individual translates into a more positive attitude toward the group nor into more positive behavior toward other individual group members (see Hewstone & Brown, 1986 for a review). Scarberry, Ratcliff, Lord, Lanicek and Desforges (1997) demonstrate that a global attitude change can be consistently achieved, however, under carefully controlled conditions.

The contact hypothesis contains a long list of conditions for a sucessful contact. However, Pettigrew and Tropp (2000) , in their meta-analysis of contact studies, have found that it is not necessary that all of Allport’s (1954) conditions be present simultaneously for bias to be reduced. Mere contact can be a sufficient condition for bias reduction that is lasting and generalizes beyond the individuals to their larger group. Importantly, however, each of Allport’s conditions further enhances the bias-reducing effects of mere contact and thus the more conditions that are co-present, the more likely a successful and lasting outcome will be achieved.

Unfortunately, there are significant barriers to meeting many of the conditions and, indeed, even to arranging for a “mere contact” to take place. This, in turn, limits the number of contacts that actually take place. The major challenges are: (1) The practicality issue: Contact between rival groups according to the conditions required by the contact hypothesis might be very complicated to arrange and expensive to run. (2) Anxiety: Despite the fact that participation in a contact is voluntary, the high anxiety involved in the contact situation may hinder its success. (3) Generalization: How can a generalization be created from a specific contact with certain outgroup members to the outgroup as a whole? We turn to a more detailed discussions of these difficulties below.

Organizing a meeting among members of opposing groups raises both logistical and financial issues. Groups that are segregated and/or geographically distant from each other will be harder to bring together and any meeting will be more costly. Even when the different groups are geographically close, linking them may still prove an expensive undertaking. Joint holiday plans for Catholic and Protestant children in Northern Ireland are one such example ( Trew, 1986 ). As the undertaking becomes more expensive, the chances of it taking place decline. In addition, there may be barriers of language or of status. Language barriers may cause feelings of distance, misunderstanding, and miscommunication among the different groups. The issue of equal status is also problematic; in some cases rival groups are characterized by extreme status differences ( Pettigrew, 1971 ).

Intergroup interactions are often more anxiety-provoking than interpersonal ones and such anxiety may not be conducive to harmonious social relations ( Islam & Hewstone, 1993 ; Stephan & Stephan, 1985 ; Wilder, 1993 ). Intergroup anxiety is the result of anticipation of negative reactions during the intergroup encounter ( Stephan & Cookie, 2001 ; Stephan & Stephan, 1996 ). When an individual is anxious, he or she is more likely to use heuristics. Thus, if an intergroup contact produces significant levels of anxiety in the individual or individuals involved, he or she is more likely to apply stereotypes to the outgroup ( Bodenhausen, 1990 ; Bodenhausen & Wyer, 1985 ).

Wilder (1993) pointed out that when in a state of anxiety, group members are likely to ignore any disconfirming information supplied in the contact context. Under such conditions, as Wilder and Shapiro (1989) demonstrated, when a member of the outgroup behaves in a positive manner that contradicts the expectations of the other side, members of the ingroup do not alter their opinions and recall the outgroup as behaving in a manner consistent with the stereotype. In such a case, the contact between these members is unlikely to bring about any change in the group stereotype.

One of the greatest challenges to the contact hypothesis is the issue of whether or not the results of a positive contact with a member of the outgroup will be generalized further. Group saliency during the interaction appears to be of critical importance to successful generalization. However, there is much debate among researchers as to what level that salience should be. Hewstone and Brown (1986) argued that a general contact is likely to be perceived on the interpersonal level and therefore not have any impact on the intergroup level. In other words, if the individual is perceived only as an individual rather than also as a representative member of his or her group, then any attitude change will remain target-specific. They suggested that, for a positive contact to have a wider group-level impact, individual participants need to be seen as representatives of their group so that the (out)group identity is highly salient. Conversely, Brewer and Miller (1984) among others have suggested that in order for a contact to succeed, group saliency should be low.

Hamburger (1994) suggested that when the central tendency of the stereotype is the only component to be measured, a large part of the picture is ignored. He added that this component may be the most resistant to change. Thus, negative results of group generalization based solely on central tendency measures may lead to erroneous conclusions regarding the contact theory in general. The inclusion of more sensitive measurements, such as variability, will give a more accurate picture, as well as allow an investigation into the background processes. Several recent studies have demonstrated Hamburger’s suggestion that the central tendency is likely to be the more rigid component in the stereotype ( Garcia-Marques & Mackie, 1999 ; Hewstone & Hamberger, 2000 ).

Clearly, when all the necessary ingredients are present, positive and beneficial results may be obtained, but just as clearly, “getting the recipe right” to produce such an outcome may be difficult at best under traditional circumstances. Yet the major literature dealing with the contact hypothesis (for a review see Brown & Hewstone, 2005 ) fails to take into account the potential role of the Internet in helping towards the success of an intergroup contact. Below we examine the ways in which contact over the Internet may overcome the practical difficulties inherent in the creation of a face-to-face contact situation according to the conditions set out in the contact hypothesis.

Internet contact and practicality

Leveling the field.

The contact hypothesis requires that there should be equal status between the members of both groups taking part in the contact. According to McClendon (1974) , equal status increases the likelihood for perceived similarities between the groups and so enhances the likelihood for improvement in their relationship and in the reduction of stereotypes ( Pettigrew, 1971 ). Optimally, there should be both external equal status (in real life) and internal equal status (within the contact) between the people taking part in the encounter. In face-to-face encounters, even very subtle differences in manner of dress, body language, use of personal space, and the seating positions taken in the room can belie real (or perceived) status differences. As Hogg (1993) has shown, within group interactions people tend to be highly sensitive in discerning subtle cues that may be indicative of status. Online interactions have the advantage here because many, although not all, of the cues individuals typically rely on to gauge the internal and external status of others are not typically in evidence.

For instance, when contact takes place in text-based environments on the Internet, regular status symbols are not part of the interaction; “on the Internet no one knows that I am wearing a diamond necklace or have teeth missing.” This point is particularly pertinent with regard to face-to-face contact, where organizers may have gone to extraordinary lengths to ensure that all participants are of equal status only to have one arrive with a Rolex watch or a similarly inappropriate status symbol.

Even when status differences are known, electronic interaction tends to ameliorate some of the effects of status differentials. For instance, when bringing together members of two established groups, the members are likely to be well aware of the internal pecking order within their own group even if they do not have knowledge of the established hierarchy among the other group’s members. In face-to-face interactions such distinctions within the groups often quickly become apparent to all, as those who stand lower tend to speak up less often and, in ways both obvious and subtle, give deference to those with higher status within their group.

Such is not the case in electronic interactions. One aspect of electronic communications that has long been decried (e.g., Sproull & Kiesler, 1991 ) is the tendency, within organizational settings, for there to be a reduction in the usual inhibitions that typically operate when interacting with one’s superiors. In other words, existing internal status does not carry as much weight and does not affect the behavior of the group members to such an extent. Underlings are more likely to speak up, to speak “out of turn,” and to speak their mind. Thus electronic interaction makes power less of an issue during discussion which leads group members, regardless of status, to contribute more to the discussion ( Spears, Postmes, Lea, & Wolbert, 2002 ). While this can prove to be problematic within a corporate setting, it is advantageous in the present context, as the medium serves to reduce the constraining effects of status both within and between the two groups.

Connecting from afar and with the comforts of home

As noted above, organizers may face significant difficulties in arranging a meeting among individuals and groups when it comes to finding a suitable meeting place, transporting the participants involved, and compensating participants for lost time due to travel incurred. This is particularly true when the groups in question or their various members live at some distance from one another. Participation may be limited to only those members of the groups who have the financial resources and job flexibility to enable their attendance or those who live in close proximity to the meeting site, rather than to all members who have the inclination (but not the resources) to attend. Thus the size and number of contacts possible are severely restricted when such meetings are face-to-face affairs.

The advent of computer-mediated interaction has opened the doors to connection possibilities that were previously not feasible. Time differences and physical distance are no longer obstacles to bringing people “together,” at least in the developed countries of the world. Electronic meetings are neither costly to set up nor are they time consuming for the participants. All that is required is for the participants to log onto the Internet and into the virtual meeting space at the specified day and time from an office, public library, or a home computer.

Indeed, having participants engage in the contact from the privacy of their respective homes has distinct advantages. Participants are likely to feel more comfortable and less anxious in their familiar surroundings. Further, research has shown that public, as opposed to private, settings can exacerbate the activation and use of stereotypes, especially when it comes to those tied to racial prejudice (e.g., Lambert, Payne, et al., 2003 ). As Zajonc (1965) has shown, an individual’s habitual or dominant response is more likely to emerge in public settings, whereas the individual is likely to be more open and receptive to altering the habitual response when in a private sphere. Even when participants interact in quite “public” electronic venues but do so from the privacy of their homes, they tend to feel that it is a private affair (e.g., McKenna & Bargh, 2000 ; McKenna, Green, & Gleason, 2002 ). Thus, interacting electronically from home should serve to inhibit the activation of stereotypes as compared to a more public and face-to-face setting in a new environment.

Cooperation toward superordinate goals