Covidence website will be inaccessible as we upgrading our platform on Monday 23rd August at 10am AEST, / 2am CEST/1am BST (Sunday, 15th August 8pm EDT/5pm PDT)

How to write the methods section of a systematic review

Home | Blog | How To | How to write the methods section of a systematic review

Covidence breaks down how to write a methods section

The methods section of your systematic review describes what you did, how you did it, and why. Readers need this information to interpret the results and conclusions of the review. Often, a lot of information needs to be distilled into just a few paragraphs. This can be a challenging task, but good preparation and the right tools will help you to set off in the right direction 🗺️🧭.

Systematic reviews are so-called because they are conducted in a way that is rigorous and replicable. So it’s important that these methods are reported in a way that is thorough, clear, and easy to navigate for the reader – whether that’s a patient, a healthcare worker, or a researcher.

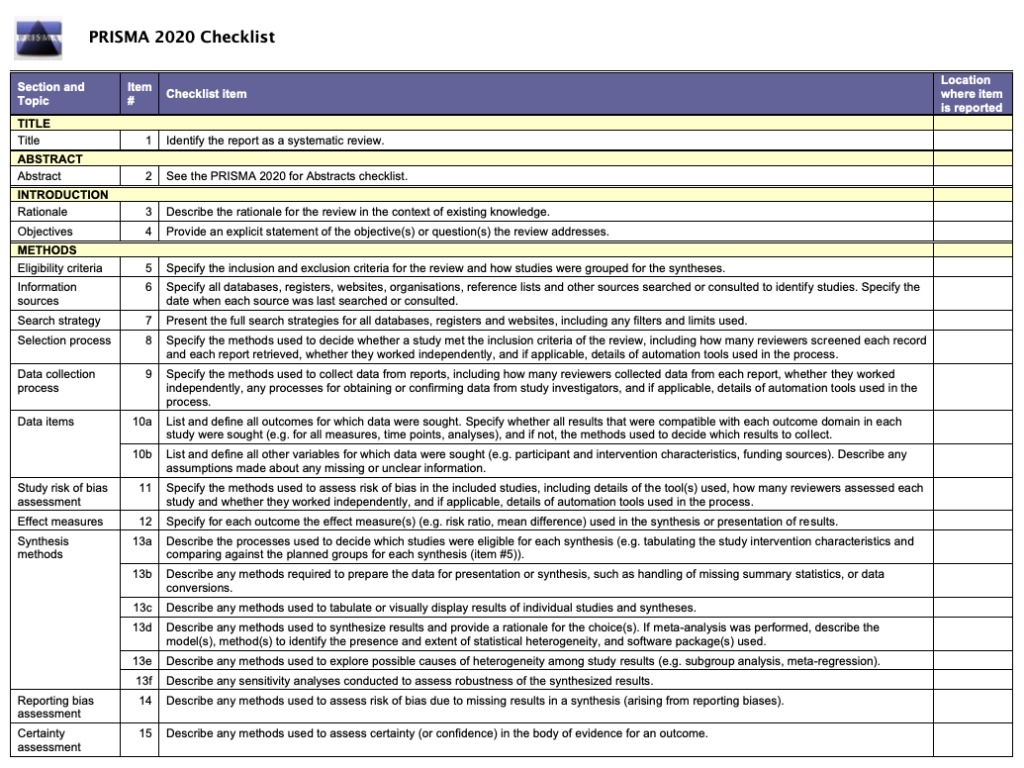

Like most things in a systematic review, the methods should be planned upfront and ideally described in detail in a project plan or protocol. Reviews of healthcare interventions follow the PRISMA guidelines for the minimum set of items to report in the methods section. But what else should be included? It’s a good idea to consider what readers will want to know about the review methods and whether the journal you’re planning to submit the work to has expectations on the reporting of methods. Finding out in advance will help you to plan what to include.

Describe what happened

While the research plan sets out what you intend to do, the methods section is a write-up of what actually happened. It’s not a simple case of rewriting the plan in the past tense – you will also need to discuss and justify deviations from the plan and describe the handling of issues that were unforeseen at the time the plan was written. For this reason, it is useful to make detailed notes before, during, and after the review is completed. Relying on memory alone risks losing valuable information and trawling through emails when the deadline is looming can be frustrating and time consuming!

Keep it brief

The methods section should be succinct but include all the noteworthy information. This can be a difficult balance to achieve. A useful strategy is to aim for a brief description that signposts the reader to a separate section or sections of supporting information. This could include datasets, a flowchart to show what happened to the excluded studies, a collection of search strategies, and tables containing detailed information about the studies.This separation keeps the review short and simple while enabling the reader to drill down to the detail as needed. And if the methods follow a well-known or standard process, it might suffice to say so and give a reference, rather than describe the process at length.

Follow a structure

A clear structure provides focus. Use of descriptive headings keeps the writing on track and helps the reader get to key information quickly. What should the structure of the methods section look like? As always, a lot depends on the type of review but it will certainly contain information relating to the following areas:

- Selection criteria ⭕

- Data collection and analysis 👩💻

- Study quality and risk of bias ⚖️

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

1. Selection criteria ⭕

The criteria for including and excluding studies are listed here. This includes detail about the types of studies, the types of participants, the types of interventions and the types of outcomes and how they were measured.

2. Search 🕵🏾♀️

Comprehensive reporting of the search is important because this means it can be evaluated and replicated. The search strategies are included in the review, along with details of the databases searched. It’s also important to list any restrictions on the search (for example, language), describe how resources other than electronic databases were searched (for example, non-indexed journals), and give the date that the searches were run. The PRISMA-S extension provides guidance on reporting literature searches.

Systematic reviewer pro-tip:

Copy and paste the search strategy to avoid introducing typos

3. Data collection and analysis 👩💻

This section describes:

- how studies were selected for inclusion in the review

- how study data were extracted from the study reports

- how study data were combined for analysis and synthesis

To describe how studies were selected for inclusion , review teams outline the screening process. Covidence uses reviewers’ decision data to automatically populate a PRISMA flow diagram for this purpose. Covidence can also calculate Cohen’s kappa to enable review teams to report the level of agreement among individual reviewers during screening.

To describe how study data were extracted from the study reports , reviewers outline the form that was used, any pilot-testing that was done, and the items that were extracted from the included studies. An important piece of information to include here is the process used to resolve conflict among the reviewers. Covidence’s data extraction tool saves reviewers’ comments and notes in the system as they work. This keeps the information in one place for easy retrieval ⚡.

To describe how study data were combined for analysis and synthesis, reviewers outline the type of synthesis (narrative or quantitative, for example), the methods for grouping data, the challenges that came up, and how these were dealt with. If the review includes a meta-analysis, it will detail how this was performed and how the treatment effects were measured.

4. Study quality and risk of bias ⚖️

Because the results of systematic reviews can be affected by many types of bias, reviewers make every effort to minimise it and to show the reader that the methods they used were appropriate. This section describes the methods used to assess study quality and an assessment of the risk of bias across a range of domains.

Steps to assess the risk of bias in studies include looking at how study participants were assigned to treatment groups and whether patients and/or study assessors were blinded to the treatment given. Reviewers also report their assessment of the risk of bias due to missing outcome data, whether that is due to participant drop-out or non-reporting of the outcomes by the study authors.

Covidence’s default template for assessing study quality is Cochrane’s risk of bias tool but it is also possible to start from scratch and build a tool with a set of custom domains if you prefer.

Careful planning, clear writing, and a structured approach are key to a good methods section. A methodologist will be able to refer review teams to examples of good methods reporting in the literature. Covidence helps reviewers to screen references, extract data and complete risk of bias tables quickly and efficiently. Sign up for a free trial today!

Laura Mellor. Portsmouth, UK

Perhaps you'd also like....

Top 5 Tips for High-Quality Systematic Review Data Extraction

Data extraction can be a complex step in the systematic review process. Here are 5 top tips from our experts to help prepare and achieve high quality data extraction.

How to get through study quality assessment Systematic Review

Find out 5 tops tips to conducting quality assessment and why it’s an important step in the systematic review process.

How to extract study data for your systematic review

Learn the basic process and some tips to build data extraction forms for your systematic review with Covidence.

Better systematic review management

Head office, working for an institution or organisation.

Find out why over 350 of the world’s leading institutions are seeing a surge in publications since using Covidence!

Request a consultation with one of our team members and start empowering your researchers:

By using our site you consent to our use of cookies to measure and improve our site’s performance. Please see our Privacy Policy for more information.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a systematic literature review [9 steps]

What is a systematic literature review?

Where are systematic literature reviews used, what types of systematic literature reviews are there, how to write a systematic literature review, 1. decide on your team, 2. formulate your question, 3. plan your research protocol, 4. search for the literature, 5. screen the literature, 6. assess the quality of the studies, 7. extract the data, 8. analyze the results, 9. interpret and present the results, registering your systematic literature review, frequently asked questions about writing a systematic literature review, related articles.

A systematic literature review is a summary, analysis, and evaluation of all the existing research on a well-formulated and specific question.

Put simply, a systematic review is a study of studies that is popular in medical and healthcare research. In this guide, we will cover:

- the definition of a systematic literature review

- the purpose of a systematic literature review

- the different types of systematic reviews

- how to write a systematic literature review

➡️ Visit our guide to the best research databases for medicine and health to find resources for your systematic review.

Systematic literature reviews can be utilized in various contexts, but they’re often relied on in clinical or healthcare settings.

Medical professionals read systematic literature reviews to stay up-to-date in their field, and granting agencies sometimes need them to make sure there’s justification for further research in an area. They can even be used as the starting point for developing clinical practice guidelines.

A classic systematic literature review can take different approaches:

- Effectiveness reviews assess the extent to which a medical intervention or therapy achieves its intended effect. They’re the most common type of systematic literature review.

- Diagnostic test accuracy reviews produce a summary of diagnostic test performance so that their accuracy can be determined before use by healthcare professionals.

- Experiential (qualitative) reviews analyze human experiences in a cultural or social context. They can be used to assess the effectiveness of an intervention from a person-centric perspective.

- Costs/economics evaluation reviews look at the cost implications of an intervention or procedure, to assess the resources needed to implement it.

- Etiology/risk reviews usually try to determine to what degree a relationship exists between an exposure and a health outcome. This can be used to better inform healthcare planning and resource allocation.

- Psychometric reviews assess the quality of health measurement tools so that the best instrument can be selected for use.

- Prevalence/incidence reviews measure both the proportion of a population who have a disease, and how often the disease occurs.

- Prognostic reviews examine the course of a disease and its potential outcomes.

- Expert opinion/policy reviews are based around expert narrative or policy. They’re often used to complement, or in the absence of, quantitative data.

- Methodology systematic reviews can be carried out to analyze any methodological issues in the design, conduct, or review of research studies.

Writing a systematic literature review can feel like an overwhelming undertaking. After all, they can often take 6 to 18 months to complete. Below we’ve prepared a step-by-step guide on how to write a systematic literature review.

- Decide on your team.

- Formulate your question.

- Plan your research protocol.

- Search for the literature.

- Screen the literature.

- Assess the quality of the studies.

- Extract the data.

- Analyze the results.

- Interpret and present the results.

When carrying out a systematic literature review, you should employ multiple reviewers in order to minimize bias and strengthen analysis. A minimum of two is a good rule of thumb, with a third to serve as a tiebreaker if needed.

You may also need to team up with a librarian to help with the search, literature screeners, a statistician to analyze the data, and the relevant subject experts.

Define your answerable question. Then ask yourself, “has someone written a systematic literature review on my question already?” If so, yours may not be needed. A librarian can help you answer this.

You should formulate a “well-built clinical question.” This is the process of generating a good search question. To do this, run through PICO:

- Patient or Population or Problem/Disease : who or what is the question about? Are there factors about them (e.g. age, race) that could be relevant to the question you’re trying to answer?

- Intervention : which main intervention or treatment are you considering for assessment?

- Comparison(s) or Control : is there an alternative intervention or treatment you’re considering? Your systematic literature review doesn’t have to contain a comparison, but you’ll want to stipulate at this stage, either way.

- Outcome(s) : what are you trying to measure or achieve? What’s the wider goal for the work you’ll be doing?

Now you need a detailed strategy for how you’re going to search for and evaluate the studies relating to your question.

The protocol for your systematic literature review should include:

- the objectives of your project

- the specific methods and processes that you’ll use

- the eligibility criteria of the individual studies

- how you plan to extract data from individual studies

- which analyses you’re going to carry out

For a full guide on how to systematically develop your protocol, take a look at the PRISMA checklist . PRISMA has been designed primarily to improve the reporting of systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses.

When writing a systematic literature review, your goal is to find all of the relevant studies relating to your question, so you need to search thoroughly .

This is where your librarian will come in handy again. They should be able to help you formulate a detailed search strategy, and point you to all of the best databases for your topic.

➡️ Read more on on how to efficiently search research databases .

The places to consider in your search are electronic scientific databases (the most popular are PubMed , MEDLINE , and Embase ), controlled clinical trial registers, non-English literature, raw data from published trials, references listed in primary sources, and unpublished sources known to experts in the field.

➡️ Take a look at our list of the top academic research databases .

Tip: Don’t miss out on “gray literature.” You’ll improve the reliability of your findings by including it.

Don’t miss out on “gray literature” sources: those sources outside of the usual academic publishing environment. They include:

- non-peer-reviewed journals

- pharmaceutical industry files

- conference proceedings

- pharmaceutical company websites

- internal reports

Gray literature sources are more likely to contain negative conclusions, so you’ll improve the reliability of your findings by including it. You should document details such as:

- The databases you search and which years they cover

- The dates you first run the searches, and when they’re updated

- Which strategies you use, including search terms

- The numbers of results obtained

➡️ Read more about gray literature .

This should be performed by your two reviewers, using the criteria documented in your research protocol. The screening is done in two phases:

- Pre-screening of all titles and abstracts, and selecting those appropriate

- Screening of the full-text articles of the selected studies

Make sure reviewers keep a log of which studies they exclude, with reasons why.

➡️ Visit our guide on what is an abstract?

Your reviewers should evaluate the methodological quality of your chosen full-text articles. Make an assessment checklist that closely aligns with your research protocol, including a consistent scoring system, calculations of the quality of each study, and sensitivity analysis.

The kinds of questions you'll come up with are:

- Were the participants really randomly allocated to their groups?

- Were the groups similar in terms of prognostic factors?

- Could the conclusions of the study have been influenced by bias?

Every step of the data extraction must be documented for transparency and replicability. Create a data extraction form and set your reviewers to work extracting data from the qualified studies.

Here’s a free detailed template for recording data extraction, from Dalhousie University. It should be adapted to your specific question.

Establish a standard measure of outcome which can be applied to each study on the basis of its effect size.

Measures of outcome for studies with:

- Binary outcomes (e.g. cured/not cured) are odds ratio and risk ratio

- Continuous outcomes (e.g. blood pressure) are means, difference in means, and standardized difference in means

- Survival or time-to-event data are hazard ratios

Design a table and populate it with your data results. Draw this out into a forest plot , which provides a simple visual representation of variation between the studies.

Then analyze the data for issues. These can include heterogeneity, which is when studies’ lines within the forest plot don’t overlap with any other studies. Again, record any excluded studies here for reference.

Consider different factors when interpreting your results. These include limitations, strength of evidence, biases, applicability, economic effects, and implications for future practice or research.

Apply appropriate grading of your evidence and consider the strength of your recommendations.

It’s best to formulate a detailed plan for how you’ll present your systematic review results. Take a look at these guidelines for interpreting results from the Cochrane Institute.

Before writing your systematic literature review, you can register it with OSF for additional guidance along the way. You could also register your completed work with PROSPERO .

Systematic literature reviews are often found in clinical or healthcare settings. Medical professionals read systematic literature reviews to stay up-to-date in their field and granting agencies sometimes need them to make sure there’s justification for further research in an area.

The first stage in carrying out a systematic literature review is to put together your team. You should employ multiple reviewers in order to minimize bias and strengthen analysis. A minimum of two is a good rule of thumb, with a third to serve as a tiebreaker if needed.

Your systematic review should include the following details:

A literature review simply provides a summary of the literature available on a topic. A systematic review, on the other hand, is more than just a summary. It also includes an analysis and evaluation of existing research. Put simply, it's a study of studies.

The final stage of conducting a systematic literature review is interpreting and presenting the results. It’s best to formulate a detailed plan for how you’ll present your systematic review results, guidelines can be found for example from the Cochrane institute .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved September 16, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 70, 2019, review article, how to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses.

- Andy P. Siddaway 1 , Alex M. Wood 2 , and Larry V. Hedges 3

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 70:747-770 (Volume publication date January 2019) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

- First published as a Review in Advance on August 08, 2018

- Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- APA Publ. Commun. Board Work. Group J. Artic. Rep. Stand. 2008 . Reporting standards for research in psychology: Why do we need them? What might they be?. Am. Psychol . 63 : 848– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF 2013 . Writing a literature review. The Portable Mentor: Expert Guide to a Successful Career in Psychology MJ Prinstein, MD Patterson 119– 32 New York: Springer, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1995 . The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 : 497– 529 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1997 . Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 3 : 311– 20 Presents a thorough and thoughtful guide to conducting narrative reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ 1995 . Writing a review article for Psychological Bulletin. Psychol . Bull 118 : 172– 77 [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Hedges LV , Higgins JPT , Rothstein HR 2009 . Introduction to Meta-Analysis New York: Wiley Presents a comprehensive introduction to meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Higgins JPT , Hedges LV , Rothstein HR 2017 . Basics of meta-analysis: I 2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 8 : 5– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL , Thoemmes FJ , Rosenthal R 2014 . Continuously cumulating meta-analysis and replicability. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 333– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ 1994 . Vote-counting procedures. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 193– 214 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J 2014 . Priming, replication, and the hardest science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 40– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers I 2007 . The lethal consequences of failing to make use of all relevant evidence about the effects of medical treatments: the importance of systematic reviews. Treating Individuals: From Randomised Trials to Personalised Medicine PM Rothwell 37– 58 London: Lancet [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Collab. 2003 . Glossary Rep., Cochrane Collab. London: http://community.cochrane.org/glossary Presents a comprehensive glossary of terms relevant to systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn LD , Becker BJ 2003 . How meta-analysis increases statistical power. Psychol. Methods 8 : 243– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2003 . Editorial. Psychol. Bull. 129 : 3– 9 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2016 . Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 5th ed.. Presents a comprehensive introduction to research synthesis and meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM , Hedges LV , Valentine JC 2009 . The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G 2014 . The new statistics: why and how. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 7– 29 Discusses the limitations of null hypothesis significance testing and viable alternative approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Earp BD , Trafimow D 2015 . Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology. Front. Psychol. 6 : 621 [Google Scholar]

- Etz A , Vandekerckhove J 2016 . A Bayesian perspective on the reproducibility project: psychology. PLOS ONE 11 : e0149794 [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ , Brannick MT 2012 . Publication bias in psychological science: prevalence, methods for identifying and controlling, and implications for the use of meta-analyses. Psychol. Methods 17 : 120– 28 [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL , Berlin JA 2009 . Effect sizes for dichotomous data. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis H Cooper, LV Hedges, JC Valentine 237– 53 New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Garside R 2014 . Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how. Innovation 27 : 67– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Olkin I 1980 . Vote count methods in research synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 88 : 359– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Pigott TD 2001 . The power of statistical tests in meta-analysis. Psychol. Methods 6 : 203– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT , Green S 2011 . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 London: Cochrane Collab. Presents comprehensive and regularly updated guidelines on systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- John LK , Loewenstein G , Prelec D 2012 . Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol. Sci. 23 : 524– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Juni P , Witschi A , Bloch R , Egger M 1999 . The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 282 : 1054– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Klein O , Doyen S , Leys C , Magalhães de Saldanha da Gama PA , Miller S et al. 2012 . Low hopes, high expectations: expectancy effects and the replicability of behavioral experiments. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7 : 6 572– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Lau J , Antman EM , Jimenez-Silva J , Kupelnick B , Mosteller F , Chalmers TC 1992 . Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 327 : 248– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Light RJ , Smith PV 1971 . Accumulating evidence: procedures for resolving contradictions among different research studies. Harvard Educ. Rev. 41 : 429– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW , Wilson D 2001 . Practical Meta-Analysis London: Sage Comprehensive and clear explanation of meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Matt GE , Cook TD 1994 . Threats to the validity of research synthesis. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 503– 20 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE , Lau MY , Howard GS 2015 . Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? What does “failure to replicate” really mean?. Am. Psychol. 70 : 487– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Hopewell S , Schulz KF , Montori V , Gøtzsche PC et al. 2010 . CONSORT explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340 : c869 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Liberati A , Tetzlaff J , Altman DG PRISMA Group. 2009 . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339 : 332– 36 Comprehensive reporting guidelines for systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A , Polisena J , Husereau D , Moulton K , Clark M et al. 2012 . The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 28 : 138– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LD , Simmons J , Simonsohn U 2018 . Psychology's renaissance. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 511– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Noblit GW , Hare RD 1988 . Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies Newbury Park, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Olivo SA , Macedo LG , Gadotti IC , Fuentes J , Stanton T , Magee DJ 2008 . Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 88 : 156– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Open Sci. Collab. 2015 . Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 : 943 [Google Scholar]

- Paterson BL , Thorne SE , Canam C , Jillings C 2001 . Meta-Study of Qualitative Health Research: A Practical Guide to Meta-Analysis and Meta-Synthesis Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Patil P , Peng RD , Leek JT 2016 . What should researchers expect when they replicate studies? A statistical view of replicability in psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 : 539– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R 1979 . The “file drawer problem” and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 86 : 638– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow RL , Rosenthal R 1989 . Statistical procedures and the justification of knowledge in psychological science. Am. Psychol. 44 : 1276– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson S , Tatt ID , Higgins JP 2007 . Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int. J. Epidemiol. 36 : 666– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R , Crooks D , Stern PN 1997 . Qualitative meta-analysis. Completing a Qualitative Project: Details and Dialogue JM Morse 311– 26 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE , Rodgers JL 2018 . Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 487– 510 [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W , Strack F 2014 . The alleged crisis and the illusion of exact replication. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 59– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF , Berlin JA , Morton SC , Olkin I , Williamson GD et al. 2000 . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE): a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283 : 2008– 12 [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S , Jensen L , Kearney MH , Noblit G , Sandelowski M 2004 . Qualitative meta-synthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual. Health Res. 14 : 1342– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Tong A , Flemming K , McInnes E , Oliver S , Craig J 2012 . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12 : 181– 88 [Google Scholar]

- Trickey D , Siddaway AP , Meiser-Stedman R , Serpell L , Field AP 2012 . A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32 : 122– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC , Biglan A , Boruch RF , Castro FG , Collins LM et al. 2011 . Replication in prevention science. Prev. Sci. 12 : 103– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

A guide to systematic literature reviews

- September 2009

- Surgery (Oxford) 27(9):381-384

- 27(9):381-384

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Syed Muzzamil Hussain Shah

- Siva Avudaiappan

- Jes She Teo

- David Moher

- Alessandro Liberati

- Elliott M. Antman

- Bruce Kupelnick

- Thomas C. Chalmers

- Jeanette Jimenez-Silva

- D R Matthews

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

State-of-the-art literature review methodology: A six-step approach for knowledge synthesis

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 05 September 2022

- Volume 11 , pages 281–288, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Erin S. Barry ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0788-7153 1 , 2 ,

- Jerusalem Merkebu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3707-8920 3 &

- Lara Varpio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1412-4341 3

32k Accesses

25 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Introduction

Researchers and practitioners rely on literature reviews to synthesize large bodies of knowledge. Many types of literature reviews have been developed, each targeting a specific purpose. However, these syntheses are hampered if the review type’s paradigmatic roots, methods, and markers of rigor are only vaguely understood. One literature review type whose methodology has yet to be elucidated is the state-of-the-art (SotA) review. If medical educators are to harness SotA reviews to generate knowledge syntheses, we must understand and articulate the paradigmatic roots of, and methods for, conducting SotA reviews.

We reviewed 940 articles published between 2014–2021 labeled as SotA reviews. We (a) identified all SotA methods-related resources, (b) examined the foundational principles and techniques underpinning the reviews, and (c) combined our findings to inductively analyze and articulate the philosophical foundations, process steps, and markers of rigor.

In the 940 articles reviewed, nearly all manuscripts (98%) lacked citations for how to conduct a SotA review. The term “state of the art” was used in 4 different ways. Analysis revealed that SotA articles are grounded in relativism and subjectivism.

This article provides a 6-step approach for conducting SotA reviews. SotA reviews offer an interpretive synthesis that describes: This is where we are now. This is how we got here. This is where we could be going. This chronologically rooted narrative synthesis provides a methodology for reviewing large bodies of literature to explore why and how our current knowledge has developed and to offer new research directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

An analysis of current practices in undertaking literature reviews in nursing: findings from a focused mapping review and synthesis

Reviewing the literature, how systematic is systematic.

Reading and interpreting reviews for health professionals: a practical review

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Literature reviews play a foundational role in scientific research; they support knowledge advancement by collecting, describing, analyzing, and integrating large bodies of information and data [ 1 , 2 ]. Indeed, as Snyder [ 3 ] argues, all scientific disciplines require literature reviews grounded in a methodology that is accurate and clearly reported. Many types of literature reviews have been developed, each with a unique purpose, distinct methods, and distinguishing characteristics of quality and rigor [ 4 , 5 ].

Each review type offers valuable insights if rigorously conducted [ 3 , 6 ]. Problematically, this is not consistently the case, and the consequences can be dire. Medical education’s policy makers and institutional leaders rely on knowledge syntheses to inform decision making [ 7 ]. Medical education curricula are shaped by these syntheses. Our accreditation standards are informed by these integrations. Our patient care is guided by these knowledge consolidations [ 8 ]. Clearly, it is important for knowledge syntheses to be held to the highest standards of rigor. And yet, that standard is not always maintained. Sometimes scholars fail to meet the review’s specified standards of rigor; other times the markers of rigor have never been explicitly articulated. While we can do little about the former, we can address the latter. One popular literature review type whose methodology has yet to be fully described, vetted, and justified is the state-of-the-art (SotA) review.

While many types of literature reviews amalgamate bodies of literature, SotA reviews offer something unique. By looking across the historical development of a body of knowledge, SotA reviews delves into questions like: Why did our knowledge evolve in this way? What other directions might our investigations have taken? What turning points in our thinking should we revisit to gain new insights? A SotA review—a form of narrative knowledge synthesis [ 5 , 9 ]—acknowledges that history reflects a series of decisions and then asks what different decisions might have been made.

SotA reviews are frequently used in many fields including the biomedical sciences [ 10 , 11 ], medicine [ 12 , 13 , 14 ], and engineering [ 15 , 16 ]. However, SotA reviews are rarely seen in medical education; indeed, a bibliometrics analysis of literature reviews published in 14 core medical education journals between 1999 and 2019 reported only 5 SotA reviews out of the 963 knowledge syntheses identified [ 17 ]. This is not to say that SotA reviews are absent; we suggest that they are often unlabeled. For instance, Schuwirth and van der Vleuten’s article “A history of assessment in medical education” [ 14 ] offers a temporally organized overview of the field’s evolving thinking about assessment. Similarly, McGaghie et al. published a chronologically structured review of simulation-based medical education research that “reviews and critically evaluates historical and contemporary research on simulation-based medical education” [ 18 , p. 50]. SotA reviews certainly have a place in medical education, even if that place is not explicitly signaled.

This lack of labeling is problematic since it conceals the purpose of, and work involved in, the SotA review synthesis. In a SotA review, the author(s) collects and analyzes the historical development of a field’s knowledge about a phenomenon, deconstructs how that understanding evolved, questions why it unfolded in specific ways, and posits new directions for research. Senior medical education scholars use SotA reviews to share their insights based on decades of work on a topic [ 14 , 18 ]; their junior counterparts use them to critique that history and propose new directions [ 19 ]. And yet, SotA reviews are generally not explicitly signaled in medical education. We suggest that at least two factors contribute to this problem. First, it may be that medical education scholars have yet to fully grasp the unique contributions SotA reviews provide. Second, the methodology and methods of SotA reviews are poorly reported making this form of knowledge synthesis appear to lack rigor. Both factors are rooted in the same foundational problem: insufficient clarity about SotA reviews. In this study, we describe SotA review methodology so that medical educators can explicitly use this form of knowledge synthesis to further advance the field.

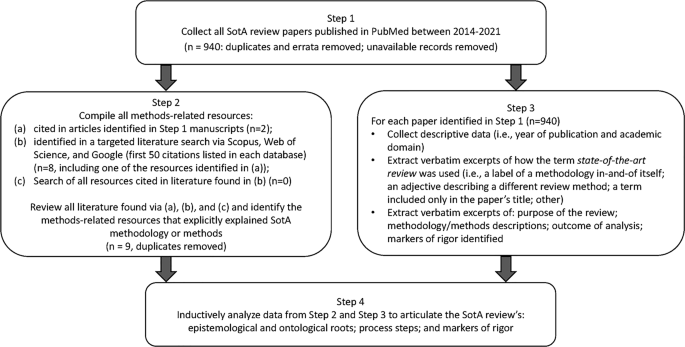

We developed a four-step research design to meet this goal, illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Four-step research design process used for developing a State-of-the-Art literature review methodology

Step 1: Collect SotA articles

To build our initial corpus of articles reporting SotA reviews, we searched PubMed using the strategy (″state of the art review″[ti] OR ″state of the art review*″) and limiting our search to English articles published between 2014 and 2021. We strategically focused on PubMed, which includes MEDLINE, and is considered the National Library of Medicine’s premier database of biomedical literature and indexes health professions education and practice literature [ 20 ]. We limited our search to 2014–2021 to capture modern use of SotA reviews. Of the 960 articles identified, nine were excluded because they were duplicates, erratum, or corrigendum records; full text copies were unavailable for 11 records. All articles identified ( n = 940) constituted the corpus for analysis.

Step 2: Compile all methods-related resources

EB, JM, or LV independently reviewed the 940 full-text articles to identify all references to resources that explained, informed, described, or otherwise supported the methods used for conducting the SotA review. Articles that met our criteria were obtained for analysis.

To ensure comprehensive retrieval, we also searched Scopus and Web of Science. Additionally, to find resources not indexed by these academic databases, we searched Google (see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] for the search strategies used for each database). EB also reviewed the first 50 items retrieved from each search looking for additional relevant resources. None were identified. Via these strategies, nine articles were identified and added to the collection of methods-related resources for analysis.

Step 3: Extract data for analysis

In Step 3, we extracted three kinds of information from the 940 articles papers identified in Step 1. First, descriptive data on each article were compiled (i.e., year of publication and the academic domain targeted by the journal). Second, each article was examined and excerpts collected about how the term state-of-the-art review was used (i.e., as a label for a methodology in-and-of itself; as an adjective qualifying another type of literature review; as a term included in the paper’s title only; or in some other way). Finally, we extracted excerpts describing: the purposes and/or aims of the SotA review; the methodology informing and methods processes used to carry out the SotA review; outcomes of analyses; and markers of rigor for the SotA review.

Two researchers (EB and JM) coded 69 articles and an interrater reliability of 94.2% was achieved. Any discrepancies were discussed. Given the high interrater reliability, the two authors split the remaining articles and coded independently.

Step 4: Construct the SotA review methodology

The methods-related resources identified in Step 2 and the data extractions from Step 3 were inductively analyzed by LV and EB to identify statements and research processes that revealed the ontology (i.e., the nature of reality that was reflected) and the epistemology (i.e., the nature of knowledge) underpinning the descriptions of the reviews. These authors studied these data to determine if the synthesis adhered to an objectivist or a subjectivist orientation, and to synthesize the purposes realized in these papers.

To confirm these interpretations, LV and EB compared their ontology, epistemology, and purpose determinations against two expectations commonly required of objectivist synthesis methods (e.g., systematic reviews): an exhaustive search strategy and an appraisal of the quality of the research data. These expectations were considered indicators of a realist ontology and objectivist epistemology [ 21 ] (i.e., that a single correct understanding of the topic can be sought through objective data collection {e.g., systematic reviews [ 22 ]}). Conversely, the inverse of these expectations were considered indicators of a relativist ontology and subjectivist epistemology [ 21 ] (i.e., that no single correct understanding of the topic is available; there are multiple valid understandings that can be generated and so a subjective interpretation of the literature is sought {e.g., narrative reviews [ 9 ]}).

Once these interpretations were confirmed, LV and EB reviewed and consolidated the methods steps described in these data. Markers of rigor were then developed that aligned with the ontology, epistemology, and methods of SotA reviews.

Of the 940 articles identified in Step 1, 98% ( n = 923) lacked citations or other references to resources that explained, informed, or otherwise supported the SotA review process. Of the 17 articles that included supporting information, 16 cited Grant and Booth’s description [ 4 ] consisting of five sentences describing the overall purpose of SotA reviews, three sentences noting perceived strengths, and four sentences articulating perceived weaknesses. This resource provides no guidance on how to conduct a SotA review methodology nor markers of rigor. The one article not referencing Grant and Booth used “an adapted comparative effectiveness research search strategy that was adapted by a health sciences librarian” [ 23 , p. 381]. One website citation was listed in support of this strategy; however, the page was no longer available in summer 2021. We determined that the corpus was uninformed by a cardinal resource or a publicly available methodology description.

In Step 2 we identified nine resources [ 4 , 5 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]; none described the methodology and/or processes of carrying out SotA reviews. Nor did they offer explicit descriptions of the ontology or epistemology underpinning SotA reviews. Instead, these resources provided short overview statements (none longer than one paragraph) about the review type [ 4 , 5 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. Thus, we determined that, to date, there are no available methodology papers describing how to conduct a SotA review.

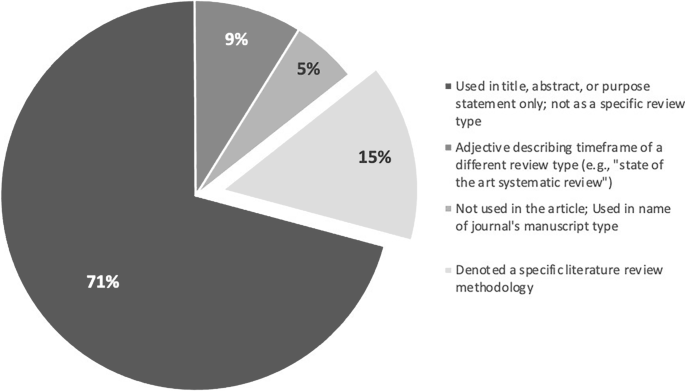

Step 3 revealed that “state of the art” was used in 4 different ways across the 940 articles (see Fig. 2 for the frequency with which each was used). In 71% ( n = 665 articles), the phrase was used only in the title, abstract, and/or purpose statement of the article; the phrase did not appear elsewhere in the paper and no SotA methodology was discussed. Nine percent ( n = 84) used the phrase as an adjective to qualify another literature review type and so relied entirely on the methodology of a different knowledge synthesis approach (e.g., “a state of the art systematic review [ 29 ]”). In 5% ( n = 52) of the articles, the phrase was not used anywhere within the article; instead, “state of the art” was the type of article within a journal. In the remaining 15% ( n = 139), the phrase denoted a specific methodology (see ESM for all methodology articles). Via Step 4’s inductive analysis, the following foundational principles of SotA reviews were developed: (1) the ontology, (2) epistemology, and (3) purpose of SotA reviews.

Four ways the term “state of the art” is used in the corpus and how frequently each is used

Ontology of SotA reviews: Relativism

SotA reviews rest on four propositions:

The literature addressing a phenomenon offers multiple perspectives on that topic (i.e., different groups of researchers may hold differing opinions and/or interpretations of data about a phenomenon).

The reality of the phenomenon itself cannot be completely perceived or understood (i.e., due to limitations [e.g., the capabilities of current technologies, a research team’s disciplinary orientation] we can only perceive a limited part of the phenomenon).

The reality of the phenomenon is a subjective and inter-subjective construction (i.e., what we understand about a phenomenon is built by individuals and so their individual subjectivities shape that understanding).

The context in which the review was conducted informs the review (e.g., a SotA review of literature about gender identity and sexual function will be synthesized differently by researchers in the domain of gender studies than by scholars working in sex reassignment surgery).

As these propositions suggest, SotA scholars bring their experiences, expectations, research purposes, and social (including academic) orientations to bear on the synthesis work. In other words, a SotA review synthesizes the literature based on a specific orientation to the topic being addressed. For instance, a SotA review written by senior scholars who are experts in the field of medical education may reflect on the turning points that have shaped the way our field has evolved the modern practices of learner assessment, noting how the nature of the problem of assessment has moved: it was first a measurement problem, then a problem that embraced human judgment but needed assessment expertise, and now a whole system problem that is to be addressed from an integrated—not a reductionist—perspective [ 12 ]. However, if other scholars were to examine this same history from a technological orientation, learner assessment could be framed as historically constricted by the media available through which to conduct assessment, pointing to how artificial intelligence is laying the foundation for the next wave of assessment in medical education [ 30 ].

Given these foundational propositions, SotA reviews are steeped in a relativist ontology—i.e., reality is socially and experientially informed and constructed, and so no single objective truth exists. Researchers’ interpretations reflect their conceptualization of the literature—a conceptualization that could change over time and that could conflict with the understandings of others.

Epistemology of SotA reviews: Subjectivism

SotA reviews embrace subjectivism. The knowledge generated through the review is value-dependent, growing out of the subjective interpretations of the researcher(s) who conducted the synthesis. The SotA review generates an interpretation of the data that is informed by the expertise, experiences, and social contexts of the researcher(s). Furthermore, the knowledge developed through SotA reviews is shaped by the historical point in time when the review was conducted. SotA reviews are thus steeped in the perspective that knowledge is shaped by individuals and their community, and is a synthesis that will change over time.

Purpose of SotA reviews

SotA reviews create a subjectively informed summary of modern thinking about a topic. As a chronologically ordered synthesis, SotA reviews describe the history of turning points in researchers’ understanding of a phenomenon to contextualize a description of modern scientific thinking on the topic. The review presents an argument about how the literature could be interpreted; it is not a definitive statement about how the literature should or must be interpreted. A SotA review explores: the pivotal points shaping the historical development of a topic, the factors that informed those changes in understanding, and the ways of thinking about and studying the topic that could inform the generation of further insights. In other words, the purpose of SotA reviews is to create a three-part argument: This is where we are now in our understanding of this topic. This is how we got here. This is where we could go next.

The SotA methodology

Based on study findings and analyses, we constructed a six-stage SotA review methodology. This six-stage approach is summarized and guiding questions are offered in Tab. 1 .

Stage 1: Determine initial research question and field of inquiry

In Stage 1, the researcher(s) creates an initial description of the topic to be summarized and so must determine what field of knowledge (and/or practice) the search will address. Knowledge developed through the SotA review process is shaped by the context informing it; thus, knowing the domain in which the review will be conducted is part of the review’s foundational work.

Stage 2: Determine timeframe

This stage involves determining the period of time that will be defined as SotA for the topic being summarized. The researcher(s) should engage in a broad-scope overview of the literature, reading across the range of literature available to develop insights into the historical development of knowledge on the topic, including the turning points that shape the current ways of thinking about a topic. Understanding the full body of literature is required to decide the dates or events that demarcate the timeframe of now in the first of the SotA’s three-part argument: where we are now . Stage 2 is complete when the researcher(s) can explicitly justify why a specific year or event is the right moment to mark the beginning of state-of-the-art thinking about the topic being summarized.

Stage 3: Finalize research question(s) to reflect timeframe

Based on the insights developed in Stage 2, the researcher(s) will likely need to revise their initial description of the topic to be summarized. The formal research question(s) framing the SotA review are finalized in Stage 3. The revised description of the topic, the research question(s), and the justification for the timeline start year must be reported in the review article. These are markers of rigor and prerequisites for moving to Stage 4.

Stage 4: Develop search strategy to find relevant articles

In Stage 4, the researcher(s) develops a search strategy to identify the literature that will be included in the SotA review. The researcher(s) needs to determine which literature databases contain articles from the domain of interest. Because the review describes how we got here , the review must include literature that predates the state-of-the-art timeframe, determined in Stage 2, to offer this historical perspective.

Developing the search strategy will be an iterative process of testing and revising the search strategy to enable the researcher(s) to capture the breadth of literature required to meet the SotA review purposes. A librarian should be consulted since their expertise can expedite the search processes and ensure that relevant resources are identified. The search strategy must be reported (e.g., in the manuscript itself or in a supplemental file) so that others may replicate the process if they so choose (e.g., to construct a different SotA review [and possible different interpretations] of the same literature). This too is a marker of rigor for SotA reviews: the search strategies informing the identification of literature must be reported.

Stage 5: Analyses

The literature analysis undertaken will reflect the subjective insights of the researcher(s); however, the foundational premises of inductive research should inform the analysis process. Therefore, the researcher(s) should begin by reading the articles in the corpus to become familiar with the literature. This familiarization work includes: noting similarities across articles, observing ways-of-thinking that have shaped current understandings of the topic, remarking on assumptions underpinning changes in understandings, identifying important decision points in the evolution of understanding, and taking notice of gaps and assumptions in current knowledge.

The researcher(s) can then generate premises for the state-of-the-art understanding of the history that gave rise to modern thinking, of the current body of knowledge, and of potential future directions for research. In this stage of the analysis, the researcher(s) should document the articles that support or contradict their premises, noting any collections of authors or schools of thinking that have dominated the literature, searching for marginalized points of view, and studying the factors that contributed to the dominance of particular ways of thinking. The researcher(s) should also observe historical decision points that could be revisited. Theory can be incorporated at this stage to help shape insights and understandings. It should be highlighted that not all corpus articles will be used in the SotA review; instead, the researcher(s) will sample across the corpus to construct a timeline that represents the seminal moments of the historical development of knowledge.

Next, the researcher(s) should verify the thoroughness and strength of their interpretations. To do this, the researcher(s) can select different articles included in the corpus and examine if those articles reflect the premises the researcher(s) set out. The researcher(s) may also seek out contradictory interpretations in the literature to be sure their summary refutes these positions. The goal of this verification work is not to engage in a triangulation process to ensure objectivity; instead, this process helps the researcher(s) ensure the interpretations made in the SotA review represent the articles being synthesized and respond to the interpretations offered by others. This is another marker of rigor for SotA reviews: the authors should engage in and report how they considered and accounted for differing interpretations of the literature, and how they verified the thoroughness of their interpretations.

Stage 6: Reflexivity

Given the relativist subjectivism of a SotA review, it is important that the manuscript offer insights into the subjectivity of the researcher(s). This reflexivity description should articulate how the subjectivity of the researcher(s) informed interpretations of the data. These reflections will also influence the suggested directions offered in the last part of the SotA three-part argument: where we could go next. This is the last marker of rigor for SotA reviews: researcher reflexivity must be considered and reported.

SotA reviews have much to offer our field since they provide information on the historical progression of medical education’s understanding of a topic, the turning points that guided that understanding, and the potential next directions for future research. Those future directions may question the soundness of turning points and prior decisions, and thereby offer new paths of investigation. Since we were unable to find a description of the SotA review methodology, we inductively developed a description of the methodology—including its paradigmatic roots, the processes to be followed, and the markers of rigor—so that scholars can harness the unique affordances of this type of knowledge synthesis.

Given their chronology- and turning point-based orientation, SotA reviews are inherently different from other types of knowledge synthesis. For example, systematic reviews focus on specific research questions that are narrow in scope [ 32 , 33 ]; in contrast, SotA reviews present a broader historical overview of knowledge development and the decisions that gave rise to our modern understandings. Scoping reviews focus on mapping the present state of knowledge about a phenomenon including, for example, the data that are currently available, the nature of that data, and the gaps in knowledge [ 34 , 35 ]; conversely, SotA reviews offer interpretations of the historical progression of knowledge relating to a phenomenon centered on significant shifts that occurred during that history. SotA reviews focus on the turning points in the history of knowledge development to suggest how different decisions could give rise to new insights. Critical reviews draw on literature outside of the domain of focus to see if external literature can offer new ways of thinking about the phenomenon of interest (e.g., drawing on insights from insects’ swarm intelligence to better understand healthcare team adaptation [ 36 ]). SotA reviews focus on one domain’s body of literature to construct a timeline of knowledge development, demarcating where we are now, demonstrating how this understanding came to be via different turning points, and offering new research directions. Certainly, SotA reviews offer a unique kind of knowledge synthesis.