Is MasterClass right for me?

Take this quiz to find out.

Get 50% off this Father's Day.

Offer Ends Soon

Higher-Order Thinking Skills: 5 Examples of Critical Thinking

Written by MasterClass

Last updated: Mar 7, 2022 • 3 min read

Fostering higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) is an important aspect of teaching students at all stages of their lives. These skills make students effective problem-solvers and form the building blocks of critical and creative thinking on a wider scale.

Higher Order Thinking: Bloom’s Taxonomy

Many students start college using the study strategies they used in high school, which is understandable—the strategies worked in the past, so why wouldn’t they work now? As you may have already figured out, college is different. Classes may be more rigorous (yet may seem less structured), your reading load may be heavier, and your professors may be less accessible. For these reasons and others, you’ll likely find that your old study habits aren’t as effective as they used to be. Part of the reason for this is that you may not be approaching the material in the same way as your professors. In this handout, we provide information on Bloom’s Taxonomy—a way of thinking about your schoolwork that can change the way you study and learn to better align with how your professors think (and how they grade).

Why higher order thinking leads to effective study

Most students report that high school was largely about remembering and understanding large amounts of content and then demonstrating this comprehension periodically on tests and exams. Bloom’s Taxonomy is a framework that starts with these two levels of thinking as important bases for pushing our brains to five other higher order levels of thinking—helping us move beyond remembering and recalling information and move deeper into application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation, and creation—the levels of thinking that your professors have in mind when they are designing exams and paper assignments. Because it is in these higher levels of thinking that our brains truly and deeply learn information, it’s important that you integrate higher order thinking into your study habits.

The following categories can help you assess your comprehension of readings, lecture notes, and other course materials. By creating and answering questions from a variety of categories, you can better anticipate and prepare for all types of exam questions. As you learn and study, start by asking yourself questions and using study methods from the level of remembering. Then, move progressively through the levels to push your understanding deeper—making your studying more meaningful and improving your long-term retention.

Level 1: Remember

This level helps us recall foundational or factual information: names, dates, formulas, definitions, components, or methods.

| Make and use flashcards for key terms. | How would you define…? |

| Make a list or timeline of the main events. | List the _________ in order. |

| List the main characteristics of something. | Who were…? |

Level 2: Understand

Understanding means that we can explain main ideas and concepts and make meaning by interpreting, classifying, summarizing, inferring, comparing, and explaining.

| Discuss content with or explain to a partner. | How would you differentiate between _____ and _____? |

| Explain the main idea of the section. | What is the main idea of ________? |

| Write a summary of the chapter in your own words. | Why did…? |

Level 3: Apply

Application allows us to recognize or use concepts in real-world situations and to address when, where, or how to employ methods and ideas.

| Seek concrete examples of abstract ideas. | Why does _________ work? |

| Work practice problems and exercises. | How would you change________? |

| Write an instructional manual or study guide on the chapter that others could use. | How would you develop a set of instructions about…? |

Level 4: Analyze

Analysis means breaking a topic or idea into components or examining a subject from different perspectives. It helps us see how the “whole” is created from the “parts.” It’s easy to miss the big picture by getting stuck at a lower level of thinking and simply remembering individual facts without seeing how they are connected. Analysis helps reveal the connections between facts.

| Generate a list of contributing factors. | How does this element contribute to the whole? |

| Determine the importance of different elements or sections | What is the significance of this section? |

| Think about it from a different perspective | How would _______ group see this? |

Level 5: Synthesize

Synthesizing means considering individual elements together for the purpose of drawing conclusions, identifying themes, or determining common elements. Here you want to shift from “parts” to “whole.”

| Generalize information from letures and readings. | Develop a proposal that would… |

| Condense and re-state the content in one or two sentences. | How can you paraphrase this information into 1-2 concise sentences? |

| Compare and contrast. | What makes ________ similar and different from __________? |

Level 6: Evaluate

Evaluating means making judgments about something based on criteria and standards. This requires checking and critiquing an argument or concept to form an opinion about its value. Often there is not a clear or correct answer to this type of question. Rather, it’s about making a judgment and supporting it with reasons and evidence.

| Decide if you like, dislike, agree, or disagree with an author or a decision. | What is your opinion about ________? What evidence and reasons support your opinion? |

| Consider what you would do if asked to make a choice. | How would you improve this? |

| Determine which approach or argument is most effective. | Which argument or approach is stronger? Why? |

Level 7: Create

Creating involves putting elements together to form a coherent or functional whole. Creating includes reorganizing elements into a new pattern or structure through planning. This is the highest and most advanced level of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

| Build a model and use it to teach the information to others. | How can you create a model and use it to teach this information to others? |

| Design an experiment. | What experiment can you make to demonstrate or test this information? |

| Write a short story about the concept. | How can this information be told in the form of a story or poem? |

Pairing Bloom’s Taxonomy with other effective study strategies

While higher order thinking is an excellent way to approach learning new information and studying, you should pair it with other effective study strategies. Check out some of these links to read up on other tools and strategies you can try:

- Study Smarter, Not Harder

- Simple Study Template

- Using Concept Maps

- Group Study

- Evidence-Based Study Strategies Video

- Memory Tips Video

- All of our resources

Other UNC resources

If you’d like some individual assistance using higher order questions (or with anything regarding your academic success), check out some of your UNC resources:

- Academic Coaching: Make an appointment with an academic coach at the Learning Center to discuss your study habits one-on-one.

- Office Hours : Make an appointment with your professor or TA to discuss course material and how to be successful in the class.

Works consulted

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D.R., Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Wittrock, M.C (2001). A taxonomy of learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York, NY: Longman.

“Bloom’s Taxonomy.” University of Waterloo. Retrieved from https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/teaching-resources/teaching-tips/planning-courses-and-assignments/course-design/blooms-taxonomy

“Bloom’s Taxonomy.” Retrieved from http://www.bloomstaxonomy.org/Blooms%20Taxonomy%20questions.pdf

Overbaugh, R., and Schultz, L. (n.d.). “Image of two versions of Bloom’s Taxonomy.” Norfolk, VA: Old Dominion University. Retrieved from https://www.odu.edu/content/dam/odu/col-dept/teaching-learning/docs/blooms-taxonomy-handout.pdf

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

Teach Starter, part of Tes Teach Starter, part of Tes

Search everything in all resources

Teaching Higher-Order Thinking Skills: Here's Why It Matters Matters So Much

Written by Alison Smith

Have you been hearing a lot about teaching and learning higher-order thinking skills lately? It may not be a new topic in educational circles, but higher-order thinking remains a hot topic of discussion, and there’s a real need to address ways to build higher-order thinking into your already crammed school year.

Imagine students leaving school without any number sense or reading comprehension skills . Imagine the outcry. Now, suppose for a moment students leave school without the life skills that they need to succeed in the 21st century. The sad reality is that many students do leave school without the ability to think for themselves and without the experience of thinking critically and creatively.

In order for our students to be equipped and prepared to live in the 21st Century, there is a very real need to teach our students to:

- think about the problems that we face in life

- explore possibilities

- come up with creative solutions to problems

- consider and appreciate other points of view

- critically evaluate what we read and hear

- make reasonable judgments

So how do you teach higher-order thinking? And for that matter, how do you define higher-order thinking? The Teach Starter teacher team did a deep dive into the educational research to save you time and get you primed on all the things you need to know to help your students!

What Is Higher-Order Thinking?

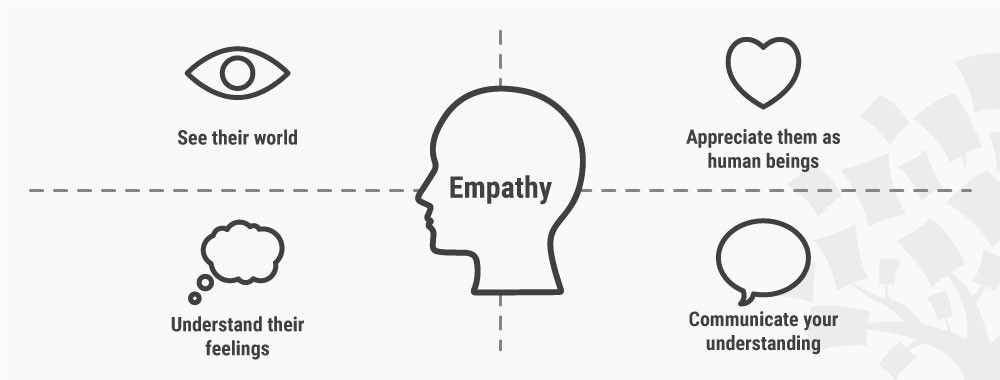

Maybe you’ve got this definition rattling around in your head, but it seemed right to start at the beginning here. When we talk about higher-order thinking, we are talking about the ability to think abstractly and make connections between concepts.

In that sense, higher-order thinking includes critical thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, as well as the ability to problem-solve and make decisions. Just as the name would imply, it is considered a more advanced level of cognitive processing than lower-order thinking, which mainly involves the recall of facts and information.

Bloom’s Taxonomy and Higher-Order Thinking

So where did higher-order thinking come from?

The classical Greek philosopher, Socrates, is often thought of as the founder of critical thinking skills. In a nutshell, Socrates introduced the idea of teaching by not providing answers but instead, teaching by asking questions: questions that explore, investigate, probe, stimulate, and engage.

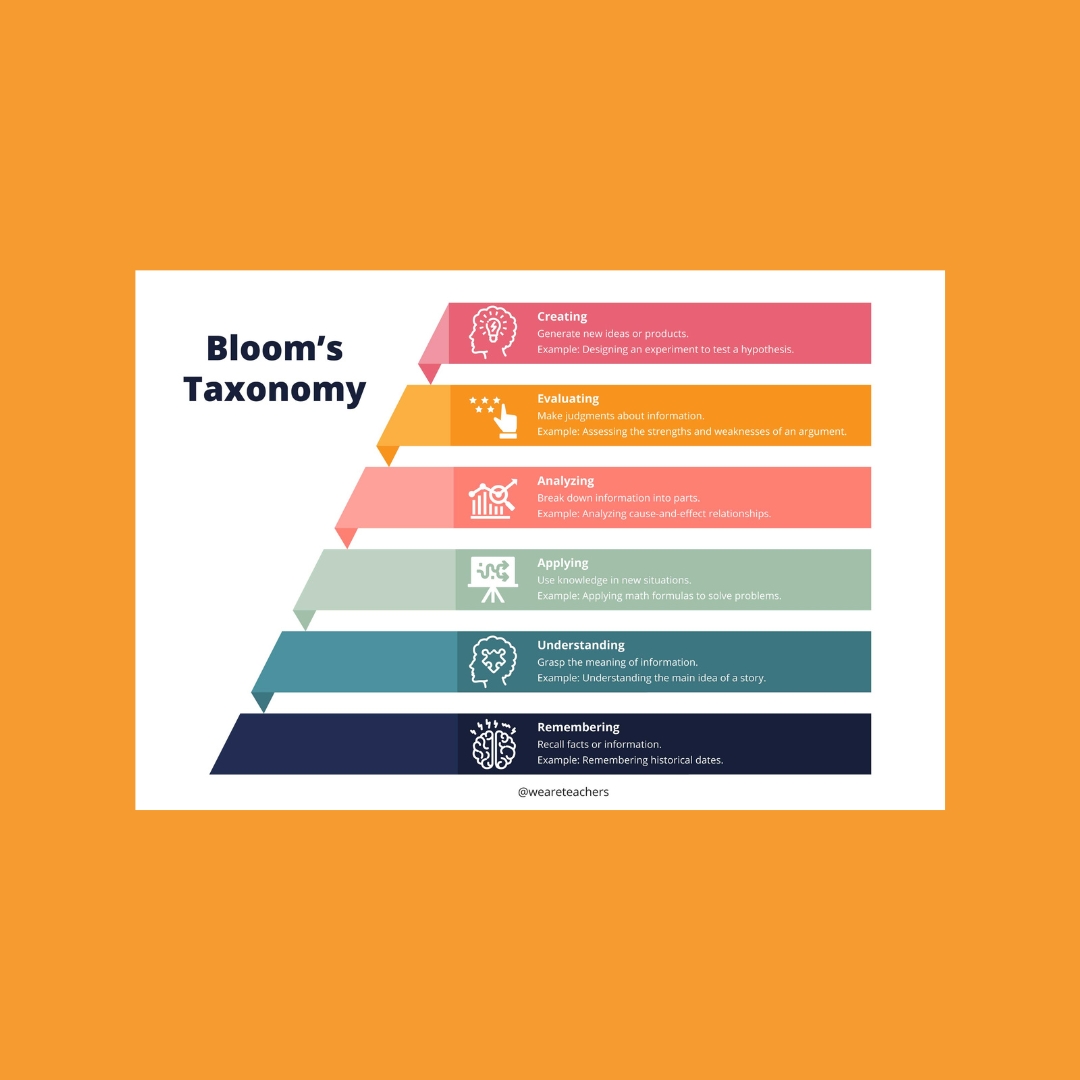

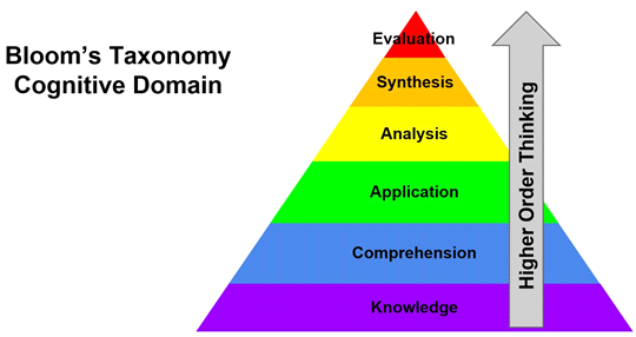

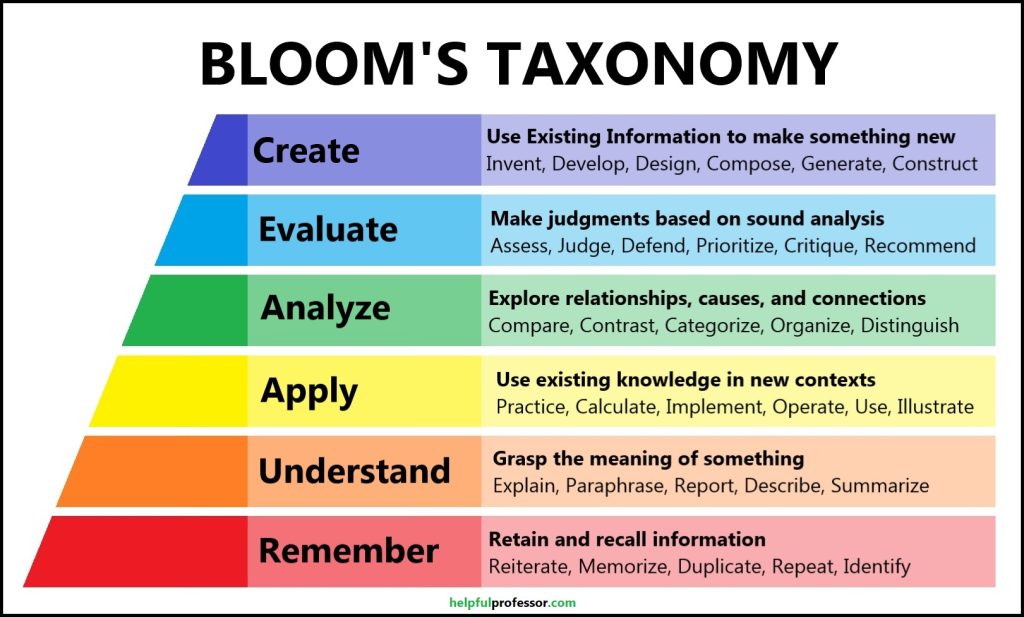

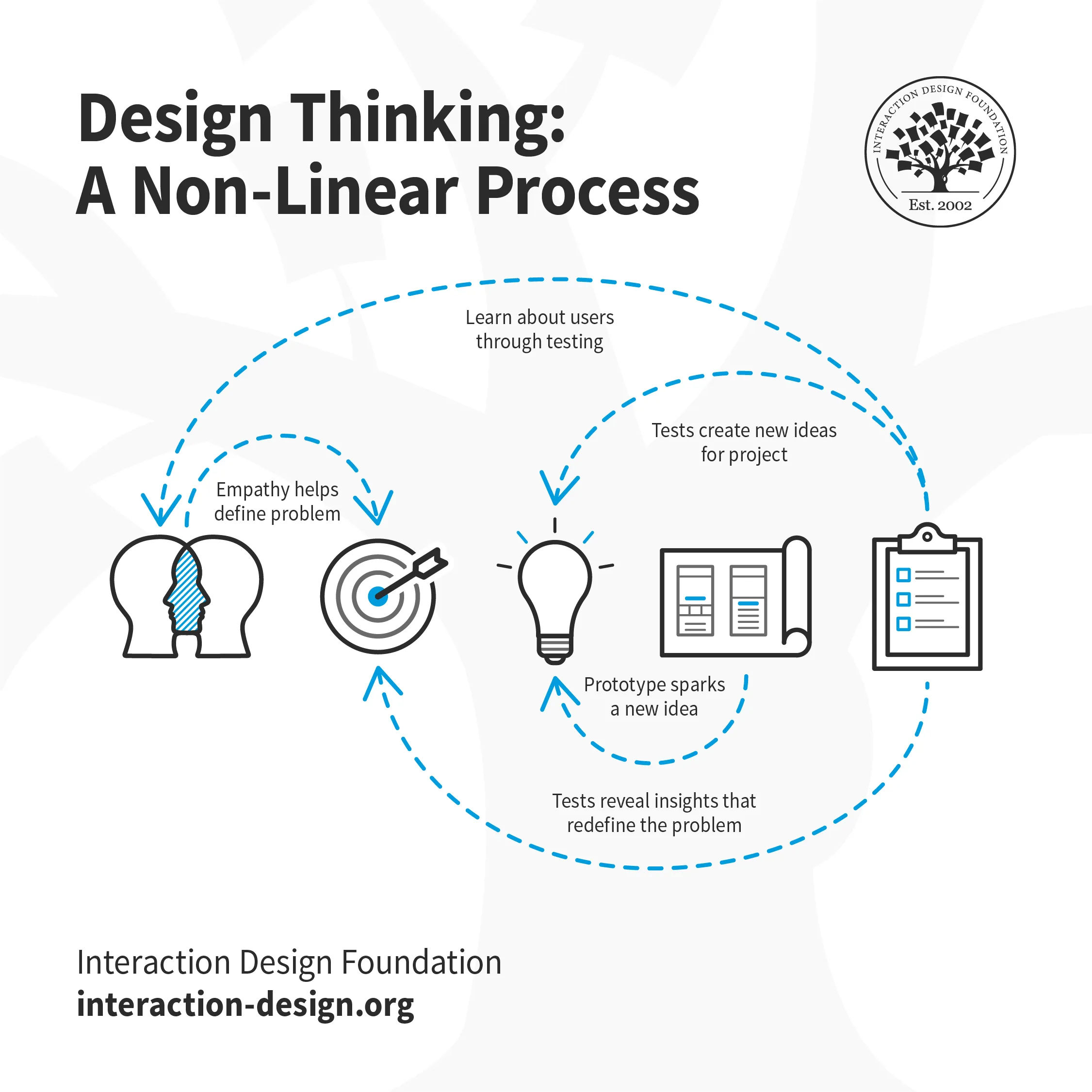

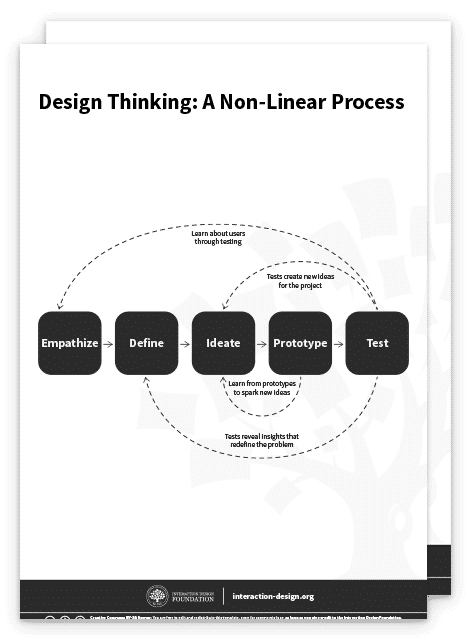

Far more recently, Bloom’s taxonomy was created by Benjamin Bloom in 1956. In one sentence, Bloom’s taxonomy is a set of six cognitive skills (in a specific order) that teachers, students, and anyone can use to promote higher-order thinking. Bloom’s framework was revised in 2001 by Lorin Anderson and David Krathwohl to produce the framework used by educators today. The six levels of the revised Bloom’s taxonomy are:

- remembering — recalling known facts

- understanding — explaining ideas or concepts

- applying — use information in new situations

- analyzing — drawing connections among ideas

- evaluating — justifying a point of view or decision

- creating — producing something new or original

Explore Bloom’s Taxonomy Teaching Tools for your classroom!

Higher-Order Thinking Skills in Kids

Children develop higher-order thinking skills at different rates, but generally, it is a gradual process that begins in early childhood and continues through adolescence and into adulthood.

According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, kids begin to develop higher-order thinking skills during the concrete operational stage, which typically occurs in upper elementary school, sometime between the ages of 7 and 11. During this stage, kids are able to think logically and understand cause-and-effect relationships .

As with all areas of the curriculum, there is a learning continuum for critical and creative thinking. Typically by the end of fourth grade , students will be able to:

- pose questions to expand their knowledge about the world

- identify main ideas and select and clarify information from a range of sources

- collect, compare and categorize facts and opinions found in a widening range of sources.

In early adolescence, children begin to develop formal operational thinking, which is characterized by the ability to think abstractly and make logical deductions. This stage is typically reached as they’re heading out of elementary school and into high school — sometime around ages 11 to 15.

Typically by the end of sixth grade, students should be able to:

- pose questions to clarify and interpret information and probe for causes and consequences

- identify and clarify relevant information and prioritize ideas

- analyze, condense, and combine relevant information from multiple sources

Focusing on helping your students build these skills has real benefits. Research has shown that teaching higher-order thinking skills can improve student achievement and prepare them for success in the 21st century.

One study by famed psychologist Richard Herrnstein (best known for his book The Bell Curve) and colleagues looked at 400 seventh graders and found that the students who were given critical thinking lessons made substantial and statistically significant improvements in language comprehension, inventive thinking, and IQ as compared to a control group. Other studies have found that students who receive instruction in higher-order thinking skills have better problem-solving abilities and are more likely to transfer their learning to novel situations.

How to Teach Higher-Order Thinking Skills

Teaching higher-order thinking skills in elementary school truly comes down to providing students with opportunities to question, connect concepts, and make inferences — much of the work you’re likely doing in your classroom right now. That said, here are some strategies you might want to employ in your classroom:

Use Graphic Organizers

Using graphic organizers, your students can actively engage with the material and make connections between different concepts, which can improve their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. The visual tools can be vital for kids as they learn to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information, which are all important aspects of higher-order thinking.

Download concept maps, Venn Diagrams, and more graphic organizers for your students!

Use Socratic Questioning

Asking a series of open-ended and probing questions to encourage critical thinking, problem-solving, and deep learning will help students to challenge assumptions, clarify concepts, and promote reasoning — all keys to improving their higher-order thinking skills.

Socratic questions can help your students to generate and test hypotheses — an important aspect of scientific thinking — as well as encouraging kids to synthesize information.

Using Question-Answer-Relationships or QARs helps students learn to make connections between the information they find in a text and their prior knowledge, boosting their higher-order thinking skills.

Use Cooperative Learning

When small groups of students work together to complete a task or achieve a goal, they have opportunities to engage in active, collaborative, and constructive learning. They’re more likely to ask questions, share ideas, and engage in critical thinking, which can lead to a deeper understanding of the material. On top of that, the social interactions that take place in a cooperative learning setting can help to build student motivation, engagement, and self-esteem, which can also contribute to the development of higher-order thinking skills.

Use Problem-Based Learning

Present your students with real-world problems that require them to apply critical thinking and problem-solving skills to find a solution. Students will also benefit from learning to use step-by-step methods for solving problems as it presents them with a methodology for tackling problems in alternative ways.

Encourage Elaboration

When students provide answers in class or while completing tasks, encourage them to move beyond the basic answer and elaborate on the why with facts and ideas to support their answer.

Explore more higher-order thinking skills resources for teachers!

Banner image via Shutterstock/bernatets photo

30 Buzzing Facts About Bees to Excite Kids About Nature

Everyone benefits from the busyness of bees which is why these bee facts will help inspire your students to appreciate and protect them!

21 Epic Last Day of School Activities to Kick Off Summer Break

Looking for easy last day of school ideas for elementary or middle school? These quick and fun end of year classroom activities will help you finish off your year just right!

70 1st Grade Books to Add to Your Classroom Reading Corner This Year

Wondering which 1st grade books you should add to your classroom library? Look no further! We have a list of 70 that are teacher (and student) approved!

22 Fun Groundhog Facts to Share With Your Class on Groundhog Day

Need fun groundhog facts to share with your students this Groundhog Day? Find out what groundhogs eat, where they live and why we let them predict the weather!

How to Teach 1st Grade — The Ultimate Guide to What to Do, What to Buy and What to Teach

Looking for tips on teaching first grade? Our comprehensive 1st grade teacher guide will answer all your questions from what to buy to how to prepare for the first day of school and what to do throughout the school year.

10 Best Pencil Sharpeners for the Classroom — Recommended by Teachers

Need new pencil sharpeners in your classroom? We've rounded up 10 best pencil sharpeners recommended by teachers to get you started.

Thank you for this much needed teacher resource. I feel so much better equipped and prepared for this coming school year!

Hi Patricia. thanks for your positive feedback. I hope that you and your class have lots of higher-order thinking fun. You are amazing!!! Have a great day! Ali

Get more inspiration delivered to your inbox!

Sign up for a free membership and receive tips, news and resources directly to your email!

K-12 Resources By Teachers, For Teachers Provided by the K-12 Teachers Alliance

- Teaching Strategies

- Classroom Activities

- Classroom Management

- Technology in the Classroom

- Professional Development

- Lesson Plans

- Writing Prompts

- Graduate Programs

Teaching Strategies that Enhance Higher-Order Thinking

Janelle cox.

- October 16, 2019

One of the main 21st century components that teachers want their students to use is higher-order thinking. This is when students use complex ways to think about what they are learning.

Higher-order thinking takes thinking to a whole new level. Students using it are understanding higher levels rather than just memorizing facts. They would have to understand the facts, infer them, and connect them to other concepts.

Here are 10 teaching strategies to enhance higher-order thinking skills in your students.

1. Help Determine What Higher-Order Thinking Is

Help students understand what higher-order thinking is. Explain to them what it is and why they need it. Help them understand their own strengths and challenges. You can do this by showing them how they can ask themselves good questions. That leads us to the next strategy.

2. Connect Concepts

Lead students through the process of how to connect one concept to another. By doing this you are teaching them to connect what they already know with what they are learning. This level of thinking will help students learn to make connections whenever it is possible, which will help them gain even more understanding. For example, let’s say that the concept they are learning is “Chinese New Year.” An even broader concept would be “Holidays.”

3. Teach Students to Infer

Teach students to make inferences by giving them “real-world” examples. You can start by giving students a picture of a people standing in line at a soup kitchen. Ask them to look at the picture and focus on the details. Then, ask them to make inferences based on what they see in the picture. Another way to teach young students about how to infer is to teach an easy concept like weather. Ask students to put on their raincoat and boots, then ask them to infer what they think the weather looks like outside.

4. Encourage Questioning

A classroom where students feel free to ask questions without any negative reactions from their peers or their teachers is a classroom where students feel free to be creative. Encourage students to ask questions, and if for some reason you can’t get to their question during class time, show them how they can answer it themselves or have them save the question until the following day.

5. Use Graphic Organizers

Graphic organizers provide students with a nice way to frame their thoughts in an organized manner. By drawing diagrams or mind maps, students are able to better connect concepts and see their relationships. This will help students develop a habit of connecting concepts.

6. Teach Problem-Solving Strategies

Teach students to use a step-by-step method for solving problems. This way of higher-order thinking will help them solve problems faster and more easily. Encourage students to use alternative methods to solve problems as well as offer them different problem-solving methods.

7. Encourage Creative Thinking

Creative thinking is when students invent, imagine, and design what they are thinking. Using creative senses helps students process and understand information better. Research shows that when students utilize creative higher-order thinking skills , it indeed increases their understanding. Encourage students to think “outside of the box.”

8. Use Mind Movies

When concepts that are being learned are difficult, encourage students to create a movie in their mind. Teach them to close their eyes and picture it like a movie playing. This way of higher-order thinking will truly help them understand in a powerful, unique way.

9. Teach Students to Elaborate Their Answers

Higher-order thinking requires students to really understand a concept, not repeat it or memorize it. Encourage students to elaborate their answers by asking the right questions that make students explain their thoughts in more detail.

10. Teach QARs

Question-Answer-Relationships, or QARs, teach students to label the type of question that is being asked and then use that information to help them formulate an answer. Students must decipher if the answer can be found in a text or online or if they must rely on their own prior knowledge to answer it. This strategy has been found to be effective for higher-order thinking because students become more aware of the relationship between the information in a text and their prior knowledge, which helps them decipher which strategy to use when they need to seek an answer.

- #CreativeThinking , #HigherOrderThinking , #TeachingStrategies

More in Teaching Strategies

Explaining the 5 Pillars of Reading

Reading is a fundamental skill that shapes the way we learn and communicate….

A Guide to Supporting Students with Bad Grades

Supporting students who are struggling academically as an educator can be challenging. Poor grades often…

Learning Where You Live: The Power of Place-Based Education

Place-based learning is an innovative approach that engages students in their community. By…

Write On! Fun Ways to Help Kids Master Pencil Grip

Teaching children proper pencil grip will lay the foundation for successful writing. Holding…

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

NEW: Classroom Clean-Up/Set-Up Email Course! 🧽

70 Higher-Order Thinking Questions To Challenge Your Students (Free Printable)

Plus 45 lower-order thinking questions too!

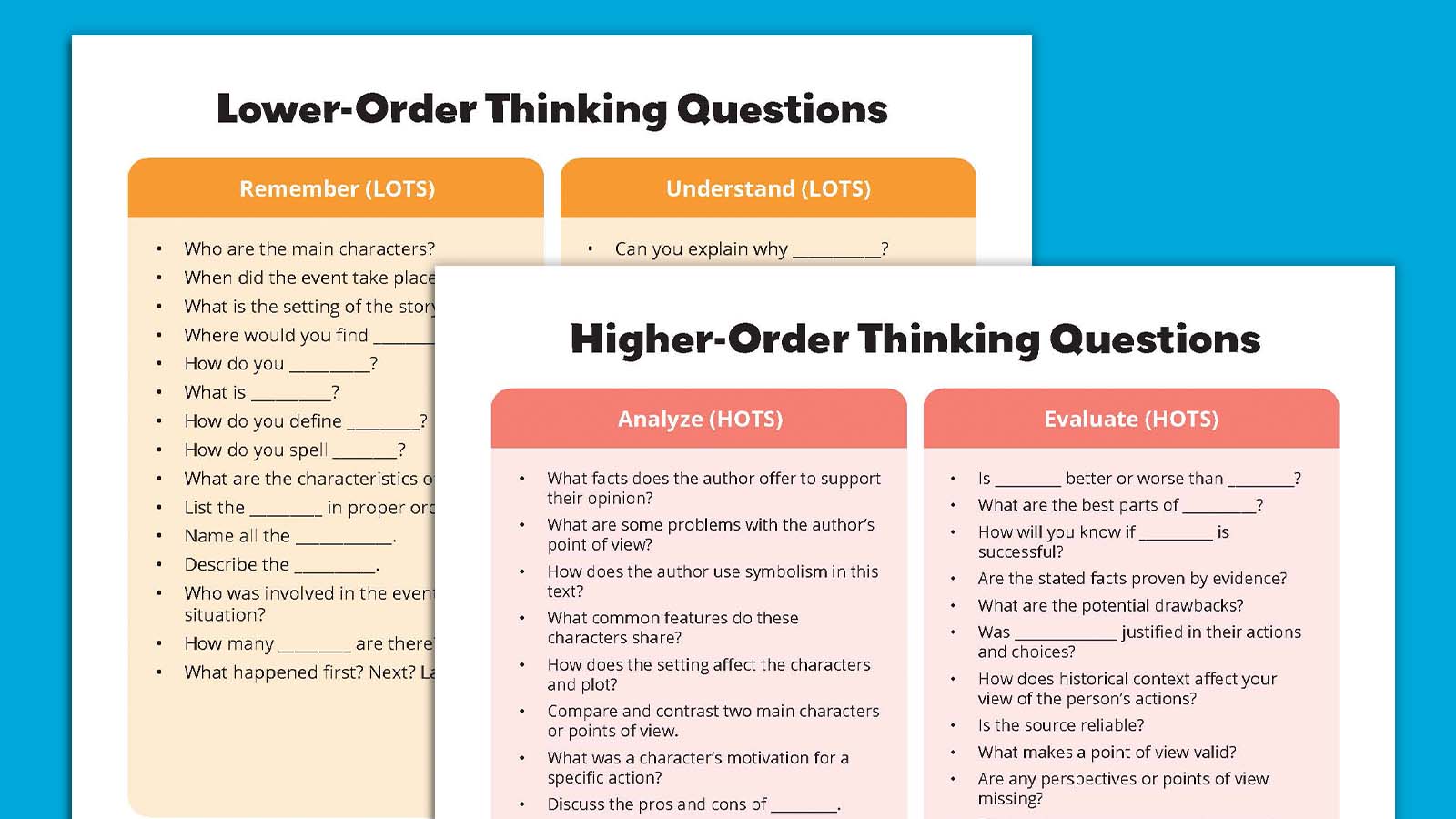

Want to help your students make strong connections with subject material? Ensure you’re using all six levels of cognitive thinking. This means asking lower-order thinking questions as well as higher-order thinking questions. Learn more about them here, and find plenty of examples for each.

Plus get a printable sheet featuring all the higher-order and lower-order thinking questions featured below.

Lower-Order Thinking Skills Questions

Higher-order thinking skills questions, what are lower-order and higher-order thinking questions.

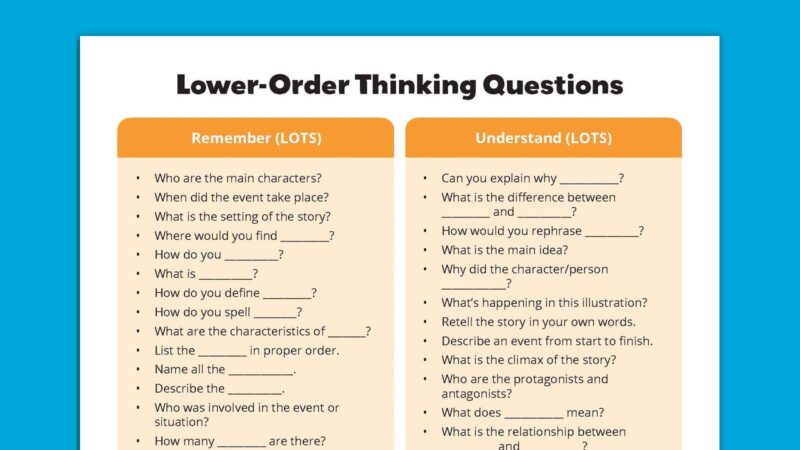

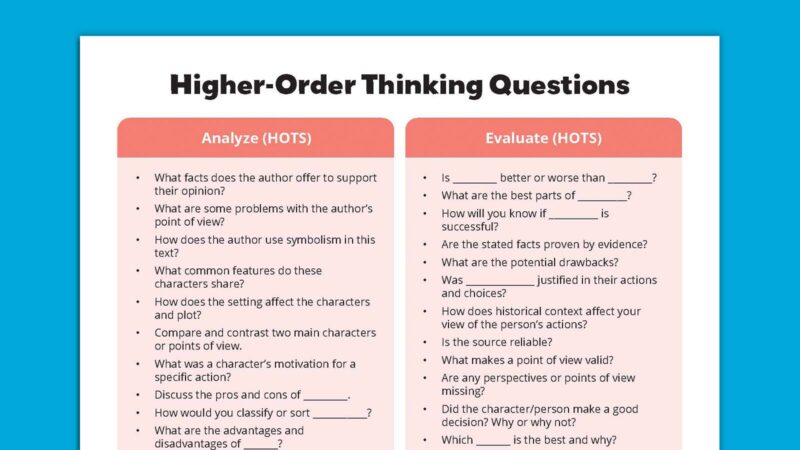

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a way of classifying cognitive thinking skills. The six main categories—remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create—are broken into lower-order thinking skills (LOTS) and higher-order thinking skills (HOTS). LOTS includes remember, understand, and apply. HOTS covers analyze, evaluate, and create.

While both LOTS and HOTS have value, higher-order thinking questions urge students to develop deeper connections with information. They also encourage kids to think critically and develop problem-solving skills. That’s why teachers like to emphasize them in the classroom.

New to higher-order thinking? Learn all about it here. Then use these lower- and higher-order thinking questions to inspire your students to examine subject material on a variety of levels.

Remember (LOTS)

- Who are the main characters?

- When did the event take place?

- What is the setting of the story?

- Where would you find _________?

- How do you __________?

- What is __________?

- How do you define _________?

- How do you spell ________?

- What are the characteristics of _______?

- List the _________ in proper order.

- Name all the ____________.

- Describe the __________.

- Who was involved in the event or situation?

- How many _________ are there?

- What happened first? Next? Last?

Understand (LOTS)

- Can you explain why ___________?

- What is the difference between _________ and __________?

- How would you rephrase __________?

- What is the main idea?

- Why did the character/person ____________?

- What’s happening in this illustration?

- Retell the story in your own words.

- Describe an event from start to finish.

- What is the climax of the story?

- Who are the protagonists and antagonists?

- What does ___________ mean?

- What is the relationship between __________ and ___________?

- Provide more information about ____________.

- Why does __________ equal ___________?

- Explain why _________ causes __________.

Apply (LOTS)

- How do you solve ___________?

- What method can you use to __________?

- What methods or approaches won’t work?

- Provide examples of _____________.

- How can you demonstrate your ability to __________.

- How would you use ___________?

- Use what you know to __________.

- How many ways are there to solve this problem?

- What can you learn from ___________?

- How can you use ________ in daily life?

- Provide facts to prove that __________.

- Organize the information to show __________.

- How would this person/character react if ________?

- Predict what would happen if __________.

- How would you find out _________?

Analyze (HOTS)

- What facts does the author offer to support their opinion?

- What are some problems with the author’s point of view?

- How does the author use symbolism in this text?

- What common features do these characters share?

- How does the setting affect the characters and plot?

- What was a character’s motivation for a specific action?

- Compare and contrast two main characters or points of view.

- Discuss the pros and cons of _________.

- How would you classify or sort ___________?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of _______?

- How is _______ connected to __________?

- What caused __________?

- What are the effects of ___________?

- How would you prioritize these facts or tasks?

- How do you explain _______?

- What patterns can you identify in the data, and what might they mean?

- Which method of solving this equation is most efficient?

- Using the information in a chart/graph, what conclusions can you draw?

- What does the data show or fail to show?

- What is the theme of _________?

- Why do you think _______?

- What is the purpose of _________?

- What was the turning point?

Evaluate (HOTS)

- Is _________ better or worse than _________?

- What are the best parts of __________?

- How will you know if __________ is successful?

- Are the stated facts proven by evidence?

- What are the potential drawbacks?

- Was ______________ justified in their actions and choices?

- How does historical context affect your view of the person’s actions?

- Is the source reliable?

- What makes a point of view valid?

- Are any perspectives or points of view missing?

- Did the character/person make a good decision? Why or why not?

- Which _______ is the best and why?

- What biases can you identify in this text?

- How effective are/were the laws or policies in achieving their goals?

- What are the biases or assumptions in an argument?

- What is the value of _________?

- Is _________ morally or ethically acceptable?

- Does __________ apply to all people equally?

- How can you disprove __________?

- Does __________ meet the specified criteria?

- What could be improved about _________?

- Do you agree with ___________?

- Does the conclusion include all pertinent data?

- Does ________ really mean ___________?

Create (HOTS)

- How can you verify ____________?

- Design an experiment to __________.

- Defend your opinion on ___________.

- How can you solve this problem?

- Create a new character for the story, then describe their background and impact.

- How would you turn this story into a movie? What changes would you make to the plot and why?

- Rewrite a story with a better ending.

- How can you persuade someone to __________?

- Make a plan to complete a task or project.

- How would you improve __________?

- What changes would you make to ___________ and why?

- How would you teach someone to _________?

- What would happen if _________?

- What alternative can you suggest for _________?

- Write a new policy to solve a societal problem.

- How would you handle an emergency situation like ____________?

- What solutions do you recommend?

- How would you do things differently?

- What are the next steps?

- How can you improve the efficiency of this process?

- What factors would need to change in order for __________?

- Invent a _________ to __________.

- What is your theory about __________?

Get your free printable with higher-order and lower-order thinking skills questions

Just enter your email address in the form on this landing page to grab a copy of our printable sheet featuring all of the higher-order and lower-order thinking questions featured above. It’s perfect to keep on hand for use during lesson planning and instruction.

What are your favorite higher-order thinking questions? Come share in the We Are Teachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, 100+ critical thinking questions for students to ask about anything ., you might also like.

What Is Higher-Order Thinking and How Do I Teach It?

Go beyond basic remembering and understanding. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) in Education

Teaching Students to Think Critically

- Applied Behavior Analysis

- Behavior Management

- Lesson Plans

- Math Strategies

- Reading & Writing

- Social Skills

- Inclusion Strategies

- Individual Education Plans

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Homeschooling

Higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) is a concept popular in American education. It distinguishes critical thinking skills from low-order learning outcomes, such as those attained by rote memorization. HOTS include synthesizing, analyzing, reasoning, comprehending, application, and evaluation.

HOTS is based on various taxonomies of learning, particularly the one created by Benjamin Bloom in his 1956 book, " Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals . " Higher-order thinking skills are reflected by the top three levels in Bloom’s Taxonomy: analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Bloom's Taxonomy and HOTS

Bloom's taxonomy is taught in a majority of teacher-education programs in the United States. As such, it may be among the most well-known educational theories among teachers nationally. As the Curriculum & Leadership Journal notes:

"While Bloom’s Taxonomy is not the only framework for teaching thinking, it is the most widely used, and subsequent frameworks tend to be closely linked to Bloom’s work.... Bloom’s aim was to promote higher forms of thinking in education, such as analyzing and evaluating, rather than just teaching students to remember facts (rote learning)."

Bloom’s taxonomy was designed with six levels to promote higher-order thinking. The six levels were: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. (The taxonomy's levels were later revised as remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, revising, and creating.) The lower-order thinking skills (LOTS) involve memorization, while higher-order thinking requires understanding and applying that knowledge.

The top three levels of Bloom's taxonomy—which is often displayed as a pyramid, with ascending levels of thinking at the top of the structure—are analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. These levels of the taxonomy all involve critical or higher-order thinking. Students who are able to think are those who can apply the knowledge and skills they have learned to new contexts. Looking at each level demonstrates how higher-order thinking is applied in education.

Analysis , the fourth level of Bloom's pyramid, involves students use their own judgment to begin analyzing the knowledge they have learned. At this point, they begin understanding the underlying structure of knowledge and also are able to distinguish between fact and opinion. Some examples of analysis would be:

- Analyze each statement to decide whether it is fact or opinion.

- Compare and contrast the beliefs of W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington.

- Apply the rule of 70 to determine how quickly your money will double at 6 percent interest.

- Illustrate the differences between the American alligator and the Nile crocodile.

Synthesis, the fifth level of Bloom’s taxonomy pyramid, requires students to infer relationships among sources , such as essays, articles, works of fiction, lectures by instructors, and even personal observations. For example, a student might infer a relationship between what she has read in a newspaper or article and what she has observed herself. The high-level thinking of synthesis is evident when students put the parts or information they have reviewed together to create new meaning or a new structure.

At the synthesis level, students move beyond relying on previously learned information or analyzing items that the teacher is giving to them. Some questions in the educational setting that would involve the synthesis level of higher-order thinking might include:

- What alternative would you suggest for ___?

- What changes would you make to revise___?

- What could you invent to solve___?

Evaluation , the top level of Bloom's taxonomy, involves students making judgments about the value of ideas, items, and materials. Evaluation is the top level of Bloom’s taxonomy pyramid because at this level that students are expected to mentally assemble all they have learned to make informed and sound evaluations of the material. Some questions involving evaluation might be:

- Evaluate the Bill of Rights and determine which is the least necessary for a free society.

- Attend a local play and write a critique of the actor’s performance.

- Visit an art museum and offer suggestions on ways to improve a specific exhibit.

HOTS in Special Education and Reform

Children with learning disabilities can benefit from educational programming that includes HOTS. Historically, their disabilities engendered lowered expectations from teachers and other professionals and led to more low-order thinking goals enforced by drill and repetition activities. However, children with learning disabilities can develop the higher-level thinking skills that teach them how to be problem solvers.

Traditional education has favored the acquisition of knowledge, especially among elementary school-age children, over the application of knowledge and critical thinking. Advocates believe that without a basis in fundamental concepts, students cannot learn the skills they will need to survive in the work world.

Reform-minded educators, meanwhile, see the acquisition of problem-solving skills—higher-order thinking—to be essential to this very outcome. Reform-minded curricula, such as the Common Core , have been adopted by a number of states, often amid controversy from traditional education advocates. At heart, these curricula emphasize HOTS, over strict rote memorization as the means to help students achieve their highest potential.

- Questions for Each Level of Bloom's Taxonomy

- Bloom's Taxonomy in the Classroom

- Using Bloom's Taxonomy for Effective Learning

- Benjamin Bloom: Critical Thinking and Critical Thinking Models

- Asking Better Questions With Bloom's Taxonomy

- Higher Level Thinking: Synthesis in Bloom's Taxonomy

- 7 Buzzwords You're Most Likely to Hear in Education

- How to Construct a Bloom's Taxonomy Assessment

- Bloom's Taxonomy: Analysis Category

- Bloom's Taxonomy - Application Category

- Bloom's Taxonomy - Evaluation Category

- 7 Ways Teachers Can Improve Their Questioning Technique

- The 6 Most Important Theories of Teaching

- How Depth of Knowledge Drives Learning and Assessment

- Critical Thinking Definition, Skills, and Examples

- Creating Effective Lesson Objectives

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

- Critical Thinking and other Higher-Order Thinking Skills

Critical thinking is a higher-order thinking skill. Higher-order thinking skills go beyond basic observation of facts and memorization. They are what we are talking about when we want our students to be evaluative, creative and innovative.

When most people think of critical thinking, they think that their words (or the words of others) are supposed to get “criticized” and torn apart in argument, when in fact all it means is that they are criteria-based. These criteria require that we distinguish fact from fiction; synthesize and evaluate information; and clearly communicate, solve problems and discover truths.

Why is Critical Thinking important in teaching?

According to Paul and Elder (2007), “Much of our thinking, left to itself, is biased, distorted, partial, uninformed or down-right prejudiced. Yet the quality of our life and that of which we produce, make, or build depends precisely on the quality of our thought.” Critical thinking is therefore the foundation of a strong education.

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy of thinking skills, the goal is to move students from lower- to higher-order thinking:

- from knowledge (information gathering) to comprehension (confirming)

- from application (making use of knowledge) to analysis (taking information apart)

- from evaluation (judging the outcome) to synthesis (putting information together) and creative generation

This provides students with the skills and motivation to become innovative producers of goods, services, and ideas. This does not have to be a linear process but can move back and forth, and skip steps.

How do I incorporate critical thinking into my course?

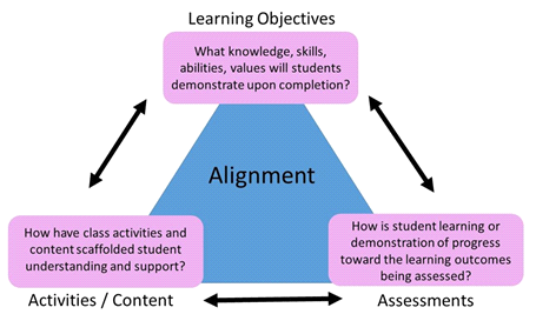

The place to begin, and most obvious space to embed critical thinking in a syllabus, is with student-learning objectives/outcomes. A well-designed course aligns everything else—all the activities, assignments, and assessments—with those core learning outcomes.

Learning outcomes contain an action (verb) and an object (noun), and often start with, “Student’s will....” Bloom’s taxonomy can help you to choose appropriate verbs to clearly state what you want students to exit the course doing, and at what level.

- Students will define the principle components of the water cycle. (This is an example of a lower-order thinking skill.)

- Students will evaluate how increased/decreased global temperatures will affect the components of the water cycle. (This is an example of a higher-order thinking skill.)

Both of the above examples are about the water cycle and both require the foundational knowledge that form the “facts” of what makes up the water cycle, but the second objective goes beyond facts to an actual understanding, application and evaluation of the water cycle.

Using a tool such as Bloom’s Taxonomy to set learning outcomes helps to prevent vague, non-evaluative expectations. It forces us to think about what we mean when we say, “Students will learn…” What is learning; how do we know they are learning?

The Best Resources For Helping Teachers Use Bloom’s Taxonomy In The Classroom by Larry Ferlazzo

Consider designing class activities, assignments, and assessments—as well as student-learning outcomes—using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a guide.

The Socratic style of questioning encourages critical thinking. Socratic questioning “is systematic method of disciplined questioning that can be used to explore complex ideas, to get to the truth of things, to open up issues and problems, to uncover assumptions, to analyze concepts, to distinguish what we know from what we don’t know, and to follow out logical implications of thought” (Paul and Elder 2007).

Socratic questioning is most frequently employed in the form of scheduled discussions about assigned material, but it can be used on a daily basis by incorporating the questioning process into your daily interactions with students.

In teaching, Paul and Elder (2007) give at least two fundamental purposes to Socratic questioning:

- To deeply explore student thinking, helping students begin to distinguish what they do and do not know or understand, and to develop intellectual humility in the process

- To foster students’ abilities to ask probing questions, helping students acquire the powerful tools of dialog, so that they can use these tools in everyday life (in questioning themselves and others)

How do I assess the development of critical thinking in my students?

If the course is carefully designed around student-learning outcomes, and some of those outcomes have a strong critical-thinking component, then final assessment of your students’ success at achieving the outcomes will be evidence of their ability to think critically. Thus, a multiple-choice exam might suffice to assess lower-order levels of “knowing,” while a project or demonstration might be required to evaluate synthesis of knowledge or creation of new understanding.

Critical thinking is not an “add on,” but an integral part of a course.

- Make critical thinking deliberate and intentional in your courses—have it in mind as you design or redesign all facets of the course

- Many students are unfamiliar with this approach and are more comfortable with a simple quest for correct answers, so take some class time to talk with students about the need to think critically and creatively in your course; identify what critical thinking entail, what it looks like, and how it will be assessed.

Additional Resources

- Barell, John. Teaching for Thoughtfulness: Classroom Strategies to Enhance Intellectual Development . Longman, 1991.

- Brookfield, Stephen D. Teaching for Critical Thinking: Tools and Techniques to Help Students Question Their Assumptions . Jossey-Bass, 2012.

- Elder, Linda and Richard Paul. 30 Days to Better Thinking and Better Living through Critical Thinking . FT Press, 2012.

- Fasko, Jr., Daniel, ed. Critical Thinking and Reasoning: Current Research, Theory, and Practice . Hampton Press, 2003.

- Fisher, Alec. Critical Thinking: An Introduction . Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Paul, Richard and Linda Elder. Critical Thinking: Learn the Tools the Best Thinkers Use . Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

- Faculty Focus article, A Syllabus Tip: Embed Big Questions

- The Critical Thinking Community

- The Critical Thinking Community’s The Thinker’s Guides Series and The Art of Socratic Questioning

Quick Links

- Developing Learning Objectives

- Creating Your Syllabus

- Active Learning

- Service Learning

- Case Based Learning

- Group and Team Based Learning

- Integrating Technology in the Classroom

- Effective PowerPoint Design

- Hybrid and Hybrid Limited Course Design

- Online Course Design

Consult with our CETL Professionals

Consultation services are available to all UConn faculty at all campuses at no charge.

- Our Mission

How to Lead Students to Engage in Higher Order Thinking

Asking students a series of essential questions at the start of a course signals that deep engagement is a requirement.

I teach multigrade, theme-based courses like Spirituality in Literature and The Natural World in Literature to high school sophomores, juniors, and seniors. And like most English language arts teachers, I’ve taught courses built around the organizing principles of genre (Introduction to Drama), time period and geography (American Literature From 1950), and even assessment instrument (A.P. Literature).

No matter what conceptual framework guides the course I’m teaching, though, I begin and anchor it with what I call a thinking inventory.

Thinking Inventories and Essential Questions

Essential questions—a staple of project-based learning—call on students’ higher order thinking and connect their lived experience with important texts and ideas. A thinking inventory is a carefully curated set of about 10 essential questions of various types, and completing one the first thing I ask students to do in every course I teach.

Although a thinking inventory is made up of questions, it’s more than a questionnaire. When we say we’re “taking inventory”—whether we’re in a warehouse or a relationship—we mean we’re taking stock of where things stand at a given moment in time, with the understanding that those things are fluid and provisional. With a thinking inventory, we’re taking stock of students’ thinking, experiences, and sense-making at the beginning of the course.

A well-designed thinking inventory formalizes the essential questions of any course and serves as a touchpoint for both teacher and students throughout that course. For a teacher, writing a course’s thinking inventory can help separate the essential from the nonessential when planning. And starting your class with a thinking inventory signals to students that higher order thinking is both required and valued.

How to Design an Effective Thinking Inventory

I tell students the thinking inventory is a document we’ll be living with—revisiting and referring to often—and that they should spend time mulling their answers before writing them down. The inventory should include a variety of essential questions, including ones that invite students to share relevant experiences.

I may ask students about their current knowledge base or life experience (What’s the best example of empathy you’ve ever witnessed?). I may ask them to make predictions or imagine scenarios (How will an American Literature course in 100 years look different from today’s American Literature course?). Or I may ask perennial questions (To what extent is it possible for human beings to change fundamentally?).

Here are a few of the questions I asked students to address at the start of a course called The Outsider in Literature:

- Who is the most visionary person you know? How do you know they’re visionary? Is there anything about them you want to emulate? Anything about them that frightens you?

- What are the risks of rebelling? Of not rebelling? Explain.

- What would happen if there were no outsiders? How would the world, and your world, be different?

- Do you think there are any ongoing conflicts between groups that are intractable—that will likely never be resolved? What is the root of the intractability? What would need to happen in order to resolve the conflict? Be specific.

- Who is the most deviant, threatening outsider you can think of? Tell us what makes them threatening.

- To what extent do you think that teenagers, as a group, are (by definition) outsiders?

How I Use Thinking Inventories

On the first day of class, I give students the inventory for homework. Because I expect well-thought-out answers and generative thinking, I assign it in chunks over two nights, and we spend at least the second and third class meetings discussing their answers.

Throughout the course, I use the inventory both implicitly and explicitly. I purposefully weave inventory questions into discussions and student writing prompts. More explicitly, I use inventory questions as a framework for pre- and post-reading activities, and as prompts for reading responses, formal writing, and journaling.

The inventory functions as a kind of time stamp that documents each student’s habits of mind, opinions, and ways of framing experience at the start of the year or semester. At the midpoint and at the end of the course, I have students return to their inventory, choose a question they’d now answer differently, and reflect on why and how their thinking has changed.

The Inventory as a Bridge Between Students and Content

By including a variety of essential questions (practical and experiential, conceptual and theoretical) and making a course’s aims explicit, the inventory invites all students into the conversation and the material from day one. It gives a deep thinker with slower processing speed or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, for example, time to orient themselves to the course’s core questions. Meanwhile, the inventory challenges students who see themselves as high achievers to respond authentically to thorny questions that have no right answers.

In addition, using a thinking inventory models how to ask good questions; gives introverts and anxious students an entry point because cold calling becomes warmer (I can ask, “What did you say on your inventory?”); and cultivates a community of learners connected by real, worthwhile inquiry and communal discourse.

Recently, a student reflecting on his inventory at the end of a course wrote that he was taken aback by how intolerant of “loser characters” he’d seemed just a few months prior on his inventory. He noted that he’d been through some upheaval since then. And he ended his paper with the observation that empathy—for people and characters—grows “when you know their backstory.”

Problem Solving Classroom

Tips from a master teacher (this is a work in progress.), higher-order thinking.

Aim Your Curriculum Correctly

We often answer the wrong question: “What’s in the curriculum?” While having a curriculum is important, you better make sure that curriculum serves the students. The question we should always return to is “What do my students need in order to thrive?”

A Road Map We Already Have

We don’t have to look far to answer this question. We were all given a road map when we trained to be teachers: Bloom’s Taxonomy . At the time, we understood the importance and relevance of helping our students develop higher-order thinking skills. Did you remember this when you landed in a district ruled by checklists of skills that could easily be assessed and marked as completed?

Skills for the 21st Century

If you wanted to bring your company or organization to the next level, which of these skills would you be looking for in job applicants? Would you want someone who could memorize theorems and complete worksheets of single-step problems, or would you be more interested in someone who could analyze complicated systems to develop cost-saving measures or innovative new directions?

If you’re thinking beyond jobs, which skills do you want to develop in the young people who will be solving tomorrow’s big problems? After all, you are partially responsible for developing the minds of the next generation.

It became clear to me early in my 35-year teaching career that knowledge was not enough. I wanted to help my students become stronger thinkers and not just puppets who were trained to demonstrate proficiency with memorized routines. This led me to develop original materials that went beyond what textbooks asked of students, and I later translated these materials into a form that other teachers could use at Trapeze Education .

Reshaping Bloom

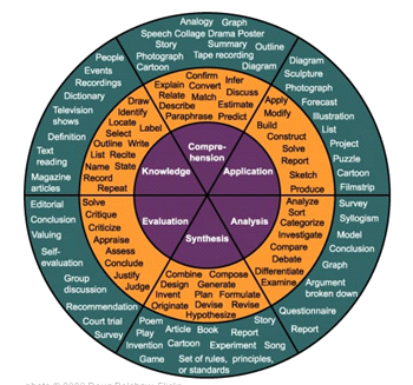

I like this depiction of Bloom’s Taxonomy that I adapted from Fractus Learning because it doesn’t show the higher-order skills as the tinier blocks at the top of a pyramid. Their sizes are more proportional to their importance. Take a few moments to look at verbs in the diagram in the context of your own teaching. What changes do you need to make either to what you do or to your school’s curriculum? While you may think that the Secant-Secant Theorem is essential to your students’ lives, are you as focused as you’d like to be on giving your students the thinking skills they need to thrive in the today’s world? Ask yourselves how your students would do on the Squirrel Problem.

Article Topics

In a nutshell, related articles, creativity in math, assessing challenging problems.

- Campus Life

- ...a student.

- ...a veteran.

- ...an alum.

- ...a parent.

- ...faculty or staff.

- UTC Learn (Canvas)

- Class Schedule

- Crisis Resources

- People Finder

- Change Password

UTC RAVE Alert

Critical thinking and problem-solving, jump to: , what is critical thinking, characteristics of critical thinking, why teach critical thinking.

- Teaching Strategies to Help Promote Critical Thinking Skills

References and Resources

When examining the vast literature on critical thinking, various definitions of critical thinking emerge. Here are some samples:

- "Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action" (Scriven, 1996).

- "Most formal definitions characterize critical thinking as the intentional application of rational, higher order thinking skills, such as analysis, synthesis, problem recognition and problem solving, inference, and evaluation" (Angelo, 1995, p. 6).

- "Critical thinking is thinking that assesses itself" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996b).

- "Critical thinking is the ability to think about one's thinking in such a way as 1. To recognize its strengths and weaknesses and, as a result, 2. To recast the thinking in improved form" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996c).

Perhaps the simplest definition is offered by Beyer (1995) : "Critical thinking... means making reasoned judgments" (p. 8). Basically, Beyer sees critical thinking as using criteria to judge the quality of something, from cooking to a conclusion of a research paper. In essence, critical thinking is a disciplined manner of thought that a person uses to assess the validity of something (statements, news stories, arguments, research, etc.).

Back

Wade (1995) identifies eight characteristics of critical thinking. Critical thinking involves asking questions, defining a problem, examining evidence, analyzing assumptions and biases, avoiding emotional reasoning, avoiding oversimplification, considering other interpretations, and tolerating ambiguity. Dealing with ambiguity is also seen by Strohm & Baukus (1995) as an essential part of critical thinking, "Ambiguity and doubt serve a critical-thinking function and are a necessary and even a productive part of the process" (p. 56).

Another characteristic of critical thinking identified by many sources is metacognition. Metacognition is thinking about one's own thinking. More specifically, "metacognition is being aware of one's thinking as one performs specific tasks and then using this awareness to control what one is doing" (Jones & Ratcliff, 1993, p. 10 ).

In the book, Critical Thinking, Beyer elaborately explains what he sees as essential aspects of critical thinking. These are:

- Dispositions: Critical thinkers are skeptical, open-minded, value fair-mindedness, respect evidence and reasoning, respect clarity and precision, look at different points of view, and will change positions when reason leads them to do so.

- Criteria: To think critically, must apply criteria. Need to have conditions that must be met for something to be judged as believable. Although the argument can be made that each subject area has different criteria, some standards apply to all subjects. "... an assertion must... be based on relevant, accurate facts; based on credible sources; precise; unbiased; free from logical fallacies; logically consistent; and strongly reasoned" (p. 12).

- Argument: Is a statement or proposition with supporting evidence. Critical thinking involves identifying, evaluating, and constructing arguments.

- Reasoning: The ability to infer a conclusion from one or multiple premises. To do so requires examining logical relationships among statements or data.

- Point of View: The way one views the world, which shapes one's construction of meaning. In a search for understanding, critical thinkers view phenomena from many different points of view.

- Procedures for Applying Criteria: Other types of thinking use a general procedure. Critical thinking makes use of many procedures. These procedures include asking questions, making judgments, and identifying assumptions.

Oliver & Utermohlen (1995) see students as too often being passive receptors of information. Through technology, the amount of information available today is massive. This information explosion is likely to continue in the future. Students need a guide to weed through the information and not just passively accept it. Students need to "develop and effectively apply critical thinking skills to their academic studies, to the complex problems that they will face, and to the critical choices they will be forced to make as a result of the information explosion and other rapid technological changes" (Oliver & Utermohlen, p. 1 ).

As mentioned in the section, Characteristics of Critical Thinking , critical thinking involves questioning. It is important to teach students how to ask good questions, to think critically, in order to continue the advancement of the very fields we are teaching. "Every field stays alive only to the extent that fresh questions are generated and taken seriously" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996a ).

Beyer sees the teaching of critical thinking as important to the very state of our nation. He argues that to live successfully in a democracy, people must be able to think critically in order to make sound decisions about personal and civic affairs. If students learn to think critically, then they can use good thinking as the guide by which they live their lives.

Teaching Strategies to Help Promote Critical Thinking

The 1995, Volume 22, issue 1, of the journal, Teaching of Psychology , is devoted to the teaching critical thinking. Most of the strategies included in this section come from the various articles that compose this issue.

- CATS (Classroom Assessment Techniques): Angelo stresses the use of ongoing classroom assessment as a way to monitor and facilitate students' critical thinking. An example of a CAT is to ask students to write a "Minute Paper" responding to questions such as "What was the most important thing you learned in today's class? What question related to this session remains uppermost in your mind?" The teacher selects some of the papers and prepares responses for the next class meeting.

- Cooperative Learning Strategies: Cooper (1995) argues that putting students in group learning situations is the best way to foster critical thinking. "In properly structured cooperative learning environments, students perform more of the active, critical thinking with continuous support and feedback from other students and the teacher" (p. 8).

- Case Study /Discussion Method: McDade (1995) describes this method as the teacher presenting a case (or story) to the class without a conclusion. Using prepared questions, the teacher then leads students through a discussion, allowing students to construct a conclusion for the case.

- Using Questions: King (1995) identifies ways of using questions in the classroom:

- Reciprocal Peer Questioning: Following lecture, the teacher displays a list of question stems (such as, "What are the strengths and weaknesses of...). Students must write questions about the lecture material. In small groups, the students ask each other the questions. Then, the whole class discusses some of the questions from each small group.

- Reader's Questions: Require students to write questions on assigned reading and turn them in at the beginning of class. Select a few of the questions as the impetus for class discussion.

- Conference Style Learning: The teacher does not "teach" the class in the sense of lecturing. The teacher is a facilitator of a conference. Students must thoroughly read all required material before class. Assigned readings should be in the zone of proximal development. That is, readings should be able to be understood by students, but also challenging. The class consists of the students asking questions of each other and discussing these questions. The teacher does not remain passive, but rather, helps "direct and mold discussions by posing strategic questions and helping students build on each others' ideas" (Underwood & Wald, 1995, p. 18 ).

- Use Writing Assignments: Wade sees the use of writing as fundamental to developing critical thinking skills. "With written assignments, an instructor can encourage the development of dialectic reasoning by requiring students to argue both [or more] sides of an issue" (p. 24).

- Written dialogues: Give students written dialogues to analyze. In small groups, students must identify the different viewpoints of each participant in the dialogue. Must look for biases, presence or exclusion of important evidence, alternative interpretations, misstatement of facts, and errors in reasoning. Each group must decide which view is the most reasonable. After coming to a conclusion, each group acts out their dialogue and explains their analysis of it.

- Spontaneous Group Dialogue: One group of students are assigned roles to play in a discussion (such as leader, information giver, opinion seeker, and disagreer). Four observer groups are formed with the functions of determining what roles are being played by whom, identifying biases and errors in thinking, evaluating reasoning skills, and examining ethical implications of the content.

- Ambiguity: Strohm & Baukus advocate producing much ambiguity in the classroom. Don't give students clear cut material. Give them conflicting information that they must think their way through.

- Angelo, T. A. (1995). Beginning the dialogue: Thoughts on promoting critical thinking: Classroom assessment for critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 6-7.

- Beyer, B. K. (1995). Critical thinking. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996a). The role of questions in thinking, teaching, and learning. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996b). Structures for student self-assessment. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univclass/trc.nclk

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996c). Three definitions of critical thinking [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Cooper, J. L. (1995). Cooperative learning and critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 7-8.

- Jones, E. A. & Ratcliff, G. (1993). Critical thinking skills for college students. National Center on Postsecondary Teaching, Learning, and Assessment, University Park, PA. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 358 772)

- King, A. (1995). Designing the instructional process to enhance critical thinking across the curriculum: Inquiring minds really do want to know: Using questioning to teach critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22 (1) , 13-17.

- McDade, S. A. (1995). Case study pedagogy to advance critical thinking. Teaching Psychology, 22(1), 9-10.

- Oliver, H. & Utermohlen, R. (1995). An innovative teaching strategy: Using critical thinking to give students a guide to the future.(Eric Document Reproduction Services No. 389 702)

- Robertson, J. F. & Rane-Szostak, D. (1996). Using dialogues to develop critical thinking skills: A practical approach. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 39(7), 552-556.

- Scriven, M. & Paul, R. (1996). Defining critical thinking: A draft statement for the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Strohm, S. M., & Baukus, R. A. (1995). Strategies for fostering critical thinking skills. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 50 (1), 55-62.

- Underwood, M. K., & Wald, R. L. (1995). Conference-style learning: A method for fostering critical thinking with heart. Teaching Psychology, 22(1), 17-21.

- Wade, C. (1995). Using writing to develop and assess critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 24-28.

Other Reading

- Bean, J. C. (1996). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, & active learning in the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

- Bernstein, D. A. (1995). A negotiation model for teaching critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 22-24.

- Carlson, E. R. (1995). Evaluating the credibility of sources. A missing link in the teaching of critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 39-41.

- Facione, P. A., Sanchez, C. A., Facione, N. C., & Gainen, J. (1995). The disposition toward critical thinking. The Journal of General Education, 44(1), 1-25.

- Halpern, D. F., & Nummedal, S. G. (1995). Closing thoughts about helping students improve how they think. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 82-83.

- Isbell, D. (1995). Teaching writing and research as inseparable: A faculty-librarian teaching team. Reference Services Review, 23(4), 51-62.

- Jones, J. M. & Safrit, R. D. (1994). Developing critical thinking skills in adult learners through innovative distance learning. Paper presented at the International Conference on the practice of adult education and social development. Jinan, China. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 373 159)

- Sanchez, M. A. (1995). Using critical-thinking principles as a guide to college-level instruction. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 72-74.

- Spicer, K. L. & Hanks, W. E. (1995). Multiple measures of critical thinking skills and predisposition in assessment of critical thinking. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association, San Antonio, TX. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 391 185)

- Terenzini, P. T., Springer, L., Pascarella, E. T., & Nora, A. (1995). Influences affecting the development of students' critical thinking skills. Research in Higher Education, 36(1), 23-39.

On the Internet

- Carr, K. S. (1990). How can we teach critical thinking. Eric Digest. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://ericps.ed.uiuc.edu/eece/pubs/digests/1990/carr90.html

- The Center for Critical Thinking (1996). Home Page. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/

- Ennis, Bob (No date). Critical thinking. [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://www.cof.orst.edu/cof/teach/for442/ct.htm

- Montclair State University (1995). Curriculum resource center. Critical thinking resources: An annotated bibliography. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.montclair.edu/Pages/CRC/Bibliographies/CriticalThinking.html

- No author, No date. Critical Thinking is ... [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://library.usask.ca/ustudy/critical/

- Sheridan, Marcia (No date). Internet education topics hotlink page. [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://sun1.iusb.edu/~msherida/topics/critical.html

Walker Center for Teaching and Learning

- 433 Library

- Dept 4354

- 615 McCallie Ave

- 423-425-4188

63 Higher-Order Thinking Skills Examples

Higher-order thinking skills are used for advanced cognitive processing of information. It occurs when a person engages in a deep level of processing and manipulating information in the mind.

The term “higher-order” is used because these forms of thinking are difficult to perform. It goes beyond just memorizing dates and facts. They are skills necessary for the generation of new knowledge and solving of complex problems.

Examples of higher-order thinking skills include critical thinking, analytical thinking , problem solving, evaluation, metacognition, and synthesis of knowledge.

Higher Order Thinking Definition (Bloom’s Taxonomy)

Educators often utilize Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956) to organize types of thinking processes into a structure that ranges from simple to advanced, or lower-order to higher-order.

The taxonomy is organized into levels of understanding and thinking, as follows:

- Remembering (Lower-Order): This is the most fundamental level of understanding that involves remembering basic information regarding a subject matter. This means that students will be able to define concepts, list facts, repeat key arguments, memorize details, or repeat information.

- Understanding (Lower-Order): Understanding means being able to explain. This can involve explaining the meaning of a concept or an idea.

- Applying (Middle-Order): Applying refers to the ability to use information in situations other than the situation in which it was learned. This represents a deeper level of understanding.

- Analyzing (Higher-Order): Conducting an analysis independently is the next level of understanding, requiring more cognitive effort . This includes the ability to draw logical conclusions based on given facts or make connections between various constructs.

- Evaluating (Higher-Order): Evaluating means determining correctness. Here, students will be able to identify the merits of an argument or point of view and weigh the relative strengths of each point.

- Creating (Higher-Order): The final level of Bloom’s taxonomy is when students can create something new. It is characterized by inventing, designing, and creating something that did not exist previously.

The premise of Bloom’s taxonomy is that thinking exists on a continuum that reflects degrees of understanding and cognitive abilities. The thinking processes toward the top of bloom’s taxonomy are considered higher-order.

The education system in many countries strive to improve higher order thinking skills such as critical thinking and innovation. Teachers around the world are constantly working to design educational activities with this aim. Their successful efforts are demonstrated in many forms, as illustrated below.

Higher Order Thinking Skills Examples

- Critical thinking – Critical thinking refers to the capacity to engage with information with an independent and analytical mindset. Instead of taking things on face value, a critical thinker uses logic and reason to evaluate the information.

- Creative thinking – According to Bloom’s taxonomy, creative thinking is the highest form of higher-order thinking. If we create something new, we are going beyond receiving and evaluating knowledge. We move up a step to generating new knowledge based on our experiences and intellect.

- Lateral thinking – Lateral thinkers take alternative routes to develop under-utilized or creative solutions to problems. ‘Lateral’ means to approach from the side rather than head-on.

- Divergent thinking – Divergent thinking refers to the process of generating multiple possible ideas from one question. It is common when we engage in brainstorming , and allows people to find creative solutions to problems.

- Convergent thinking – Convergent thinking is about gathering facts to come up with an answer or solution. It’s seen as the opposite of divergent thinking because you’re gathering information together to come up with one single solution rather than searching around and comparing multiple different solutions.

- Counterfactual thinking – Counterfactual thinking involves asking “what if?” questions in order to think of alternatives that may have happened if there were small changes made here and there. It is useful for reflective thinking and self-improvement.

- Synthesizing – When we synthesize information, we are gathering information from multiple sources, identifying trends and themes, and bringing it together into one review or evaluation of the knowledge base.

- Invention – Invention occurs when something entirely new is created for the first time. In order for this to occur, a person usually needs to have thorough understanding of existing knowledge and then have the critical and creative thinking skills to build upon it.

- Metacognition – Metacognition refers to “thinking about thinking”. It’s a thinking skill that involves reflecting on your own thinking processes and how you engaged with a task in order to seek improvements in your own thinking processes.

- Evaluation – Evaluation goes beyond reding for understanding. It moves up to the level of assessing the correctness, quality, or merits of information presented to you.

- Abstract thinking – Abstraction refers to engaging with ideas in theoretical rather than practical ways. The step up from learning about practical issues to applying practical knowledge to abstract, theoretical, and hypothetical contexts is considered higher-order.

- Identifying logical fallacies – In philosophy classes, students are asked to look at arguments and critique their use of logic. When students identify fallacies and heuristics , they are demonstrating higher-order skills like critique , judgment, and logic.

Additional Examples

- Data manipulation

- Troubleshooting

- Metaphorical thinking

- Problem solving

- Out of the box thinking

- Media literacy

- Concept mapping

- Applying to new contexts

- Compare and Contrast

- Categorizing

- Distinguishing difference and similarity

- Identifying correlation

- Deconstructing texts

- Find Patterns

- Integrating knowledge

- Structuring knowledge

- Questioning established facts

- Discriminating between concepts

- Connecting the dots

- Classifying

- Inquiring (see: inquiry based learning )

- Finding Strengths

- Finding Weaknesses

- Prioritizing

- Creating Hierarchies

- Making value judgements

- Developing a thesis statement

- Constructing something new

- Formulating

- Socratic questioning

- Hypothesizing

- Pushing boundaries

- Proposing something new

- Mind-Mapping

How to Develop Higher-Order Thinking Skills in Education

Educators expend a great deal of time trying to build up their students’ higher-order thinking skills. Generally, this starts with curriculum design.

During curriculum design, educators often consult bloom’s taxonomy verbs to create lessons and assessment tasks that directly assess higher-order thinking.

With learning outcomes that have higher-order thinking verbs embedded in them, lesson plans and the actual activities in class are more likely to target higher-order thinking skills.

In the classroom, teachers should focus on strategies used to instil higher-order thinking. These are often constructivist learning strategies , such as:

- Open-ended questioning: Instead of just asking yes/no questions, teachers try to ask higher-order thinking questions that require full-sentence responses. This can lead students to think through and articulate responses based upon critique and analysis rather than simple memorization.

- Active learning : When students are simply told information and asked to memorize, they are engaged in what we call passive learning. By contrast, when students actually complete tasks themselves, they are engaging in active learning.