Advertisement

Environment

Destruction of nature is as big a threat to humanity as climate change.

By Michael Le Page

Farming and housing occupies large amounts of land globally

Steve Proehl/Getty

We are destroying nature at an unprecedented rate, threatening the survival of a million species – and our own future, too. But it’s not too late to save them and us, says a major new report.

“The evidence is incontestable. Our destruction of biodiversity and ecosystem services has reached levels that threaten our well-being at least as much as human-induced climate change.”

With these words chair Robert Watson launched a meeting in Paris to agree the final text of a major UN report on the state of nature around the world – the biggest and most thorough assessment to date, put together by 150 scientists from 50 countries.

The report, released today, is mostly grim reading. We humans have already significantly altered three-quarters of all land and two-thirds of the oceans. More than a third of land and three-quarters of freshwater resources are devoted to crops or livestock.

Around 700 vertebrates have gone extinct in the past few centuries. Forty per cent of amphibians and a third of coral species, sharks and marine mammals look set to follow.

Less room for wildlife

Preventing this is vital to save ourselves, the report says. “Ecosystems, species, wild populations, local varieties and breeds of domesticated plants and animals are shrinking, deteriorating or vanishing,” says one of the the report’s authors, Josef Settele. “This loss is a direct result of human activity and constitutes a direct threat to human well-being in all regions of the world.”

The main reason is simple. Our expanding farms and cities are leaving less room for wildlife. The other major causes are the direct exploitation of wildlife such as hunting, climate change, pollution and the spread of invasive species. Climate change is set to become ever more destructive.

Read more: Is life on Earth really at risk? The truth about the extinction crisis

But we can still turn things around, the report says. “Nature can be conserved, restored and used sustainably while simultaneously meeting other global societal goals through urgent and concerted efforts fostering transformative change,” it states.

It also says that where land is owned or managed by indigenous peoples and local communities, there has been less destruction and sometimes none at all.

The aim of the report, by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), is to provide an authoritative scientific basis for international action . The hope is that it will lead to the same pressure for action as the latest scientific report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), on limiting warming to 1.5°C.

“Good knowledge is absolutely essential for good governance,” says Watson, who chaired the IPCC from 1997 to 2002 . “I’m optimistic that this will make a difference.”

Bioenergy threat

But the challenge is immense. All countries except the US have ratified the 1992 UN Convention of Biodiversity and are supposed to be conserving biodiversity and promoting its sustainable use.

Despite this, more than 80 per cent of the agreed international targets for 2020 will not be met, says the report. In fact, as of 2016, half the signatory countries hadn’t yet drawn up plans on how to meet the targets .

The problem isn’t just our focus on economic growth regardless of the impact on the natural world. Current plans for reducing carbon dioxide emissions to net-zero to limit climate change rely heavily on bioenergy, which requires a lot of land. This will accelerate species loss as well as threatening food and water security, says the report.

Read more: Rewilding: Can we really restore ravaged nature to a pristine state?

In fact, the bioenergy push is already causing harm. For instance, rainforests are being cut down in Indonesia and Malaysia to grow palm oil to make biodiesel for cars in Europe .

Transforming our civilisation to make it more sustainable will require more connected thinking, the report says. “There’s a very fragmented approach,” says Watson. “We’ve got to think about all these things in a much more holistic way.”

For instance, there are ways of tackling climate change that will help biodiversity too, such as persuading people to eat less meat and planting more trees. But the devil is in the detail – artificial plantations would benefit wildlife far less than restoring natural forests.

Some of the solutions set out in the report may not be welcome to all. In particular, it effectively calls for wealthy people to consume less, suggesting that changing the habits of the affluent may be central to sustainable development worldwide.

Read more: Half the planet should be set aside for wildlife – to save ourselves

Sign up to our weekly newsletter.

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

'Unluckiest star' may be trapped in deadly dance with a black hole

Subscriber-only

Smartphone use can actually help teenagers boost their mood

Relax with aqua, a colourful board game about building coral reefs, mathematics, the monty hall problem shows how tricky judging the odds can be, popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

Essay on Human Destroying Nature

Students are often asked to write an essay on Human Destroying Nature in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Human Destroying Nature

Introduction.

Humans and nature have always shared a connection. But recently, this bond is being harmed by human activities.

The Destruction

Deforestation, pollution, and global warming are major issues. Trees are cut down for industries, harming wildlife and causing climate change.

Effects on Nature

Nature suffers as species lose their homes and pollution harms the air and water. This imbalance can lead to disasters like floods and droughts.

We must learn to respect nature. By reducing pollution and planting more trees, we can help protect our planet for future generations.

250 Words Essay on Human Destroying Nature

Human beings, in their quest for development, are significantly impacting the natural world. The anthropogenic activities, driven by industrialization and urbanization, are causing irreparable damage to nature.

Deforestation and Habitat Loss

Forests, the lungs of our planet, are being ruthlessly cut down for timber, agriculture, and infrastructure. This rampant deforestation is not just eradicating millions of species but also disrupting the carbon cycle, leading to climate change.

Overexploitation of Natural Resources

The insatiable human desire for resources is exhausting the Earth’s reserves. Overfishing, overhunting, and over-mining are pushing many species to the brink of extinction and depleting our non-renewable resources.

Climate Change

Human-induced climate change, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels, is causing global warming, ocean acidification, and extreme weather events. These changes threaten biodiversity, human health, and the stability of societies.

Plastic Pollution

The plastic menace is another significant issue. It not only pollutes our lands and oceans but also harms wildlife that mistake it for food.

The relentless human assault on nature is a ticking time bomb. It is crucial to understand that the survival of humanity is intertwined with the health of our planet. Sustainable development should be our guiding principle, where we meet our needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs. It’s high time we shifted from being nature’s conquerors to its custodians.

500 Words Essay on Human Destroying Nature

The human impact on nature.

The relationship between humans and nature is complex and multifaceted. While nature provides us with the resources necessary for survival and growth, our actions often lead to its degradation. This essay aims to examine the ways in which human activities are destroying nature and the potential repercussions of such actions.

The Industrial Revolution and Its Aftermath

The Industrial Revolution marked a significant turning point in human history. While it led to remarkable advancements in technology and living standards, it also ushered in an era of unprecedented environmental destruction. The increased demand for natural resources led to deforestation, soil erosion, and the extinction of several species. Industrial waste polluted rivers and oceans, while the burning of fossil fuels contributed to global warming.

Urbanization and Habitat Destruction

As the human population expands, so does the demand for land. Urbanization has led to the destruction of natural habitats, threatening biodiversity. Forests are cleared to make way for cities, roads, and agriculture, leading to the displacement of countless species. This not only disrupts the ecological balance but also increases the risk of human-animal conflict.

Climate Change: A Threat of Our Own Making

Human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation, are major contributors to climate change. The increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has led to a rise in global temperatures, resulting in melting ice caps, rising sea levels, and extreme weather conditions. These changes pose a significant threat to both humans and wildlife.

The Plastics Problem

The proliferation of plastic waste is another example of human-induced environmental harm. Non-biodegradable and toxic, plastics pollute our land and water bodies, harming wildlife and contaminating food chains. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a massive accumulation of plastic debris in the Pacific Ocean, is a stark reminder of our throwaway culture.

The Path Forward

Despite the grim picture painted above, all is not lost. We have the knowledge and tools to mitigate the harm we’ve inflicted on nature. Sustainable practices in agriculture, energy production, and waste management can help reduce our environmental footprint. Conservation efforts can protect endangered species and restore damaged ecosystems. Education and awareness can foster a culture of respect for nature.

In conclusion, the destruction of nature by human activities is a pressing issue that requires immediate attention. The survival of our species is intricately linked with the health of our planet. It is our responsibility to ensure that future generations inherit a world where nature thrives in all its diversity and splendor.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Importance of Nature

- Essay on Conservation of Nature

- Essay on Beauty of Nature

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

One Comment

this helped a lot thank you

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Nature Essay for Students and Children

500+ words nature essay.

Nature is an important and integral part of mankind. It is one of the greatest blessings for human life; however, nowadays humans fail to recognize it as one. Nature has been an inspiration for numerous poets, writers, artists and more of yesteryears. This remarkable creation inspired them to write poems and stories in the glory of it. They truly valued nature which reflects in their works even today. Essentially, nature is everything we are surrounded by like the water we drink, the air we breathe, the sun we soak in, the birds we hear chirping, the moon we gaze at and more. Above all, it is rich and vibrant and consists of both living and non-living things. Therefore, people of the modern age should also learn something from people of yesteryear and start valuing nature before it gets too late.

Significance of Nature

Nature has been in existence long before humans and ever since it has taken care of mankind and nourished it forever. In other words, it offers us a protective layer which guards us against all kinds of damages and harms. Survival of mankind without nature is impossible and humans need to understand that.

If nature has the ability to protect us, it is also powerful enough to destroy the entire mankind. Every form of nature, for instance, the plants , animals , rivers, mountains, moon, and more holds equal significance for us. Absence of one element is enough to cause a catastrophe in the functioning of human life.

We fulfill our healthy lifestyle by eating and drinking healthy, which nature gives us. Similarly, it provides us with water and food that enables us to do so. Rainfall and sunshine, the two most important elements to survive are derived from nature itself.

Further, the air we breathe and the wood we use for various purposes are a gift of nature only. But, with technological advancements, people are not paying attention to nature. The need to conserve and balance the natural assets is rising day by day which requires immediate attention.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conservation of Nature

In order to conserve nature, we must take drastic steps right away to prevent any further damage. The most important step is to prevent deforestation at all levels. Cutting down of trees has serious consequences in different spheres. It can cause soil erosion easily and also bring a decline in rainfall on a major level.

Polluting ocean water must be strictly prohibited by all industries straightaway as it causes a lot of water shortage. The excessive use of automobiles, AC’s and ovens emit a lot of Chlorofluorocarbons’ which depletes the ozone layer. This, in turn, causes global warming which causes thermal expansion and melting of glaciers.

Therefore, we should avoid personal use of the vehicle when we can, switch to public transport and carpooling. We must invest in solar energy giving a chance for the natural resources to replenish.

In conclusion, nature has a powerful transformative power which is responsible for the functioning of life on earth. It is essential for mankind to flourish so it is our duty to conserve it for our future generations. We must stop the selfish activities and try our best to preserve the natural resources so life can forever be nourished on earth.

{ “@context”: “https://schema.org”, “@type”: “FAQPage”, “mainEntity”: [ { “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “Why is nature important?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”: “Nature is an essential part of our lives. It is important as it helps in the functioning of human life and gives us natural resources to lead a healthy life.” } }, { “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “How can we conserve nature?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”: “We can take different steps to conserve nature like stopping the cutting down of trees. We must not use automobiles excessively and take public transport instead. Further, we must not pollute our ocean and river water.” } } ] }

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Friday essay: thinking like a planet - environmental crisis and the humanities

Emeritus Professor of History, Australian National University

Disclosure statement

Tom Griffiths does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Australian National University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Many of us joined the Global Climate Strike on Friday, 20 September, and together we constituted half a million Australians gathering peacefully and walking the streets of our cities and towns to protest at government inaction in the face of the gravest threat human civilisation has faced.

It was a global strike, but its Australian manifestation had a particular twist, for our own federal government is an international pariah on this issue. We have become the Ugly Australians, led by brazen climate deniers who trash the science and snub the UN Climate Summit.

Government politicians in Canberra constantly tell us the Great Barrier Reef is fine, coal is good for humanity, Pacific islands are floating not being flooded, wind turbines are obscene, power blackouts are due to renewables, “drought-proofing” is urgent but “climate-change” has nothing to do with it, science is a conspiracy, climate protesters are a “scourge” who deserve to be punished and jailed, the ABC spins the weather, the Bureau of Meteorology requires a royal commission, the United Nations is a bully, if we have to have emissions targets, well, we are exceeding them, and Australia is so insignificant in the world it doesn’t have to act anyway.

It’s a wilful barrage of lies, an insult to the public, a threat to civil society, and an extraordinary attack on our intelligence by our own elected representatives.

The international Schools4Climate movement is remarkable because it is led by children, teenagers still at school advocating a future they hope to have. I can’t think of another popular protest movement in world history led by children. This could be a transformative moment in global politics; it certainly needs to be. The active presence of so many engaged children gave the rally a spirit and a lightness in spite of its grim subject; there was a sense of fun, a family feeling about the occasion, but there was a steely resolve too.

A girl in a school uniform standing next to me at the rally held a copy of George Orwell’s 1984 in her hands. Many of the people around me would normally expect to see in the 22nd century. Their power, paradoxically, is they are not voters. They didn’t elect this government! They are protesting not just against the governments of the world but also against us adults, who did elect these politicians or who abide them. There was a moment at the rally when, with the mysterious organic coherence crowds possess, the older protesters stepped aside, parting like a wave, and formed a guard of honour through the centre of which the children marched holding their placards, their leadership acknowledged.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Orwell's 1984 and how it helps us understand tyrannical power today

One placard declared: “You’ll die of old age; I’ll die of climate change”; another said: “If Earth were cool, I’d be in school.” One held up a large School Report Card with subject results: “Ethics X, Responsibility X, Climate Action X. Needs to try harder.” Another explained: “You skip summits, we skip school.”

In Melbourne, as elsewhere, teenagers gave the speeches; and they were passionate and eloquent. The demands of the movement are threefold: no new coal, oil and gas projects; 100% renewable energy generation and exports by 2030; and fund a just transition and job creation for all fossil-fuel workers and communities. There were also Indigenous speakers. One declared: “We stand for you too, when we stand for Country.”

There were 150,000 people in the Melbourne Treasury Gardens, a crowd so large responsive cheers rippled like a Mexican wave up the hill from the speakers. I reflected on the historical parallels for what was unfolding, recalling the Vietnam moratorium demonstrations and the marches against the first Gulf War, the Freedom Rides and the civil rights movement, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy and the suffragettes’ campaigns.

Inspired by this history, we now have the Extinction Rebellion , a movement born in a small British town late last year which declares “only non-violent rebellion can now stop climate breakdown and social collapse”. Within six months, through civil disobedience, it brought central London to a standstill and the United Kingdom became the first country to declare a climate emergency. We are at a political tipping point.

In Australia, the result of this year’s election tells us there is no accountability for probably the most dysfunctional and discredited federal government in our history, and now we are left with a parliament unwilling to act on so many vital national and international issues. The 2019 federal election was no status quo outcome, as some political commentators have declared. Rather, it was a radical result, revealing deep structural flaws in our parliamentary democracy, our media culture and our political discourse. For me it ranks with two other elections in my voting lifetime: the “dark victory” of the 2001 Tampa election , and the 1975 constitutional crisis . Like those earlier dates, 2019 could shape and shadow a generation. It is time to get out on the streets again.

Skolstrejk för klimatet

The founder, symbol and the voice of the School Strike movement is, of course, Greta Thunberg. It is just over a year since August 2018 when she began to spend every Friday away from class sitting outside the Swedish parliament with a handmade sign declaring “School Strike for the Climate”.

When she told her parents about her plans, she reported “they weren’t very fond of it”. Addressing the UN Climate Change Conference in December 2018, she said : “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is. Even that burden you leave to your children.” Thunberg quietly invokes the carbon budget and the galling fact there is already so much carbon in the system “there is simply not enough time to wait for us to grow up and become the ones in charge.”

In late September, Thunberg gave a powerful presentation at the UN Climate Summit; Richard Flanagan compared her 495-word UN speech to Abraham Lincoln’s 273-word Gettysburg Address. It’s a reasonable parallel that reaches for some understanding of the enormity of this political moment.

It is sickening to see the speed with which privileged old white men have rushed to pour bile on this young woman. Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin quickly recognised her power and sought to neutralise and patronise her. Scott Morrison chimed in. Australia’s locker room of shock jocks laced the criticism with some misogyny. It’s amazing how they froth at the mouth about a calm and articulate schoolgirl. They are all – directly or indirectly – in the pockets of the fossil fuel industry.

Read more: Misogyny, male rage and the words men use to describe Greta Thunberg

Denialism is worthy of study . I don’t mean the conscious and fraudulent denialism of politicians and shock-jocks such as those I’ve mentioned. That’s pretty simple stuff – lies motivated by opportunism, greed and personal advancement, and funded by the carbon-polluting industries. It is appalling but boring.

There are more interesting forms of denialism, such as the emotional denialism we all inhabit. Emotional denialism in the face of the unthinkable can take many forms – avoidance, hope, anxiety, even a kind of torpor when people truly begin to understand what will happen to the world of their grandchildren. We are all prone to this willing blindness and comforting self-delusion. Overcoming that is our greatest challenge.

And there is a third kind of denialism that should especially interest scholars. It is when some of our own kind – scholars trained to respect evidence – fashion themselves as sceptics, but are actually dogged contrarians.

Read more: There are three types of climate change denier, and most of us are at least one

One example is Niall Ferguson, a Scottish historian and professor of history at Harvard University, who calls climate science “science fiction” and recently joined the ranks of old, white, privileged men commenting on the appearance of Greta Thunberg. I’m not arguing here with Ferguson’s politics – he is an arch-conservative and I do disagree with his politics, but I also believe engaged, reflective politics can drive good history.

Rather, Ferguson’s disregard for evidence and neglect of science and scholarship attracts my attention. His understanding of climate science and climate history is poor: in a recent article in the Boston Globe he assumed the Little Ice Age started in the 17th century, whereas its beginning was three centuries earlier .

How does a trained scholar, a professor of history, get themselves in this ignominious position? For Ferguson, contrarianism has been a productive intellectual strategy – going against the flow of fashion is a good scholarly instinct – but on climate change his politics and the truth have steadily travelled in different directions and caught him out. We can say the same of Geoffrey Blainey, another successful contrarian who has cornered himself on climate change . Like Ferguson he appears uninterested in decades of significant research in environmental history – and thus his healthy scepticism has morphed into foolish denialism.

Denialism matters because all kinds of it have delayed our global political response to climate change by 30 years. In those critical decades since the 1980s, when humans first understood the urgency of the climate crisis, total historical carbon emissions since the industrial revolution have doubled . And still global emissions are rising, every year.

The physics of this process are inexorable – and so simple, as Greta would say, even a child can understand. We are already committing ourselves to two degrees of warming, possibly three or four. Denialists have, knowingly and with malice aforethought, condemned future generations to what Tim Flannery calls a “grim winnowing”. Flannery wrote recently “the climate crisis has now grown so severe that the actions of the denialists have turned predatory: they are now an immediate threat to our children.”

Read more: The gloves are off: 'predatory' climate deniers are a threat to our children

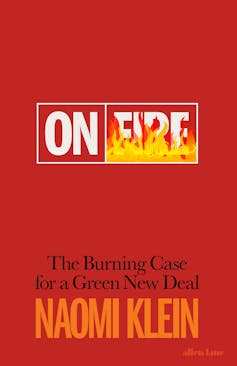

The history of denialism alerts us to a disastrous paradox: the very moment, in the 1980s, when it became clear global warming was a collective predicament of humanity, we turned away politically from the idea of the collective, with dire consequences. Naomi Klein, in her latest book On Fire , elucidates this fateful coincidence, which she calls “an epic case of historical bad timing”: just as the urgency of action on climate change became apparent, “the global neoliberal revolution went supernova”.

Unfettered free-market fanaticism and its relentless attack on the public sphere derailed the momentum building for corporate regulation and global cooperation. Ten years ago, thoughtful, informed climate activists could still argue that we can decouple the debates about economy and democracy from climate action. But now we can’t. At the 2019 election, Australia may have missed its last chance for incremental political change. If the far right had not politicised climate change and delayed action for so long then radical political transformation would not necessarily have been required. But now it will be, and it’s coming.

A great derangement

We are indeed living in what we might call “uncanny times”. They are weird, strange and unsettling in ways that question nature and culture and even the possibility of distinguishing between them.

The Bengali novelist Amitav Ghosh uses the term “uncanny” in his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable , published in 2016. The planet is alive, says Ghosh, and only for the last three centuries have we forgotten that. We have been suffering from “the great derangement”, a disturbing condition of wilful and systematic blindness to the consequences of our own actions, in which we are knowingly killing the planetary systems that support the survival of our species. That’s what’s uncanny about our times: we are half-aware of this predicament yet also paralysed by it, caught between horror and hubris.

We inhabit a critical moment in the history of the Earth and of life on this planet, and a most unusual one in terms of our own human history. We have developed two powerful metaphors for making sense of it. One is the idea of the Anthropocene , which is the insight we have entered a new geological epoch in the history of the Earth and have now left behind the 13,000 years of the relatively stable Holocene epoch, the period since the last great ice age. The new epoch recognises the power of humans in changing the nature of the planet, putting us on a par with other geophysical forces such as variations in the earth’s orbit, glaciers, volcanoes and asteroid strikes.

The other potent metaphor for this moment in Earth history is the Sixth Extinction . Humans have wiped out about two-thirds of the world’s wildlife in just the last half-century.

Let that sentence sink in. It has happened in less than a human lifetime. The current extinction rate is a hundred to a thousand times higher than was normal in nature. There have been other such catastrophic collapses in the diversity of life on Earth: five of them – sudden, shocking falls in the graph of biodiversity separated by tens of millions of years, the last one in the immediate aftermath of the asteroid impact that ended the age of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. We now have to ask ourselves: are we inhabiting – and causing – the Sixth Extinction?

These two metaphors – the Anthropocene and the Sixth Extinction – are both historical concepts that require us to travel in geological and biological time across hundreds of millions of years and then to arrive back at the present with a sense not of continuity but of discontinuity, of profound rupture. That’s what Earth system science has revealed: it’s now too late to go back to the Holocene. We’ve irrevocably changed the Earth system and unwittingly steered the planet into the Anthropocene; now we can’t take our hand off the tiller.

Earth is alive

I’ve been considering metaphors of deep time, but what of deep space? It has also enlarged our imaginations in the last half century. In July this year, we commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing. I was 12 at the time of the Apollo 11 voyage and found myself in a school debate about whether the money for the Moon mission would be better spent on Earth. I argued it would be, and my team lost.

But what other result was allowable in July 1969? Conquering the Moon, declared Dr Wernher von Braun, Nazi scientist turned US rocket maestro, assured man of immortality . I followed the Apollo missions with a sense of wonder, staying up late to watch the Saturn V launch, joining my schoolmates in a large hall with tiny televisions to witness Armstrong take his Giant Leap, and saving full editions of The Age newspaper reporting those fabled days.

The rhetoric of space exploration was so future-oriented that NASA did not foresee Apollo’s greatest legacy: the radical effect of seeing the Earth. In 1968, the historic Apollo 8 mission launched humans beyond Earth’s orbit for the first time, into the gravitational power of another heavenly body. For three lunar orbits, the three astronauts studied the strange, desolate, cratered surface below them and then, as they came out from the dark side of the Moon for the fourth time, they looked up and gasped :

Frank Borman: Oh my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, that is pretty! Bill Anders: Hey, don’t take that, it’s not scheduled.

They did take the unscheduled photo, excitedly, and it became famous, perhaps the most famous photograph of the 20th century, the blue planet floating alone, finite and vulnerable in space above a dead lunar landscape. Bill Anders declared : “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

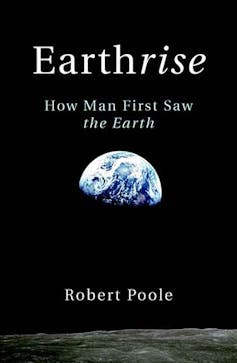

In his fascinating book, Earthrise (2010), British historian Robert Poole explains this was not supposed to happen. The cutting edge of the future was to be in space. Leaving the Earth’s atmosphere was seen as a stage in human evolution comparable to our amphibian ancestor crawling out of the primeval slime onto land.

Furthermore, this new dominion was seen to offer what Neil Armstrong called a “survival possibility” for a world shadowed by the nuclear arms race. In the words of Buzz Lightyear (who is sometimes hilariously confused with Buzz Aldrin), the space age looked to infinity and beyond!

Earthrise had a profound impact on environmental politics and sensibilities. Within a few years, the American scientist James Lovelock put forward “ the Gaia hypothesis ”: that the Earth is a single, self-regulating organism. In the year of the Apollo 8 mission, Paul Ehrlich published his book, The Population Bomb , an urgent appraisal of a finite Earth. British economist Barbara Ward wrote Spaceship Earth and Only One Earth , revealing how economics failed to account for environmental damage and degradation, and arguing that exponential growth could not continue forever.

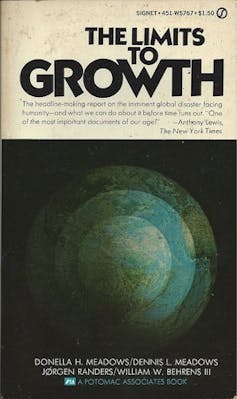

Earth Day was established in 1970, a day to honour the planet as a whole, a total environment needing protection. In 1972, the Club of Rome released its controversial and influential report The Limits to Growth , which sold over 13 million copies. In their report, Donella Meadows and Dennis Meadows wrestled with the contradiction of trying to force infinite material growth on a finite planet. The cover of their book depicted a whole Earth, a shrinking Earth.

Earth systems science developed in the second half of the 20th century and fostered a keen understanding of planetary boundaries – thresholds in planetary ecology - and the extent to which they were being violated. The same industrial capitalism that unleashed carbon enabled us to extract ice cores from the poles and construct a deep history of the air. The fossil fuels that got humans to the Moon, it now emerged, were endangering our civilisation.

The American ecologist and conservationist Aldo Leopold wrote in 1949 of the need for a new “land ethic” . Leopold envisaged a gradual historical expansion of human ethics, from the relations between individuals to those between the individual and society, and ultimately to those between humans and the land. He hoped for an enlargement of the community to which we imagine ourselves belonging, one that includes soil, water, plants and animals.

In his book of essays, A Sand County Almanac , there is a short, profound reflection called “Thinking like a mountain.” He tells of going on the mountain and shooting a wolf and her cubs and then watching “a fierce green fire” die in her eyes.

He shot her because he thought fewer wolves meant more deer, but over the years he watched the overpopulated deer herd die as the wolfless mountain became a dustbowl. Leopold came to understand the beautiful delicacy of the ecosystem, which holds “a deeper meaning, known only to the mountain itself. Only the mountain has lived long enough to listen objectively to the howl of a wolf.”

Today, 70 years after Leopold’s philosophical leap, we are being challenged to scale up from a land ethic to an earth ethic, to an environmental vision and philosophy of action that sees the planet as an integrated whole and all of life upon it as an interdependent historical community with a common destiny, to think not only like a mountain, but also like a planet. We are belatedly remembering the planet is alive.

Climate science is climate history

Climate change and ecological crisis are often seen as purely scientific issues. But as humanities scholars we know all environmental problems are at heart human ones; “scientific” issues are pre-eminently challenges for the humanities. Historical perspective can offer much in this time of ecological crisis, and many historians are reinventing their traditional scales of space and time to tell different kinds of stories, ones that recognise the agency of other creatures and the unruly power of nature.

There is a tendency among denialists to lazily use history against climate science, arguing for example “the climate’s always changing”, or “this has happened before”. Good recent historical scholarship about the last 2000 years of human civilisation is so important because it corrects these misunderstandings. That’s why it’s so disappointing when celebrity historians like Niall Ferguson and Geoffrey Blainey seek to represent their discipline by ignoring the work of their colleagues.

Climate science is unavoidably climate history; it’s an empirical, historical interpretation of life on earth, full of new insights into the impact and predicament of humanity in the long and short term. Recent histories of the last 2,000 years have been crucial in helping us to appreciate the fragile relationship between climate and society, and why future average temperature changes of more than 2°C can have dire consequences for human civilisation.

We now have environmental histories of antiquity, and of medieval and early modern Europe – studies casting new light on familiar human dramas, including the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, the Black Death in the medieval period, and the unholy trinity of famine, war and disease during the Little Ice Age of the 17th century.

These books draw on natural as well as human history, on the archives of ice, air and sediment as well as bones, artefacts and documents. And then there is John McNeill’s history of the 20th century, Something New Under the Sun , which argues “the human race, without intending anything of the sort, has undertaken a gigantic uncontrolled experiment on earth”.

These new histories encompass the planet and the human species, and provocatively blur biological evolution and cultural history (Yuval Noah Harari’s “brief history of humankind”, Sapiens , is a bestselling example). They investigate the vast elemental nature of the heavens as well as the interior, microbial nature of human bodies: nature inside and out, with the striving human as a porous vessel for its agency.

In Australia, we have outstanding new histories linking geological and human time, such as Charles Massy’s Call of the Reed Warbler: A New Agriculture – A New Earth and Tony Hughes d’Aeth’s Like Nothing on This Earth: A Literary History of the Wheatbelt .

Australians seem predisposed to navigate the Anthropocene. I think it’s because the challenge of Australian history in the 21st century is how to negotiate the rupture of 1788, how to relate geological and human scales, how to get our heads and hearts around a colonial history of 200 years that plays out across a vast Indigenous history in deep time.

From the beginnings of colonisation, Australia’s new arrivals commonly alleged Aboriginal people had no history, had been here no more than a few thousand years, and were caught in the fatal thrall of a continental museum. But from the early 1960s, archaeologists confirmed what Aboriginal people had always known: Australia’s human history went back aeons, into the Pleistocene, well into the last ice age. In the late 20th century, the timescale of Australia’s human history increased tenfold in just 30 years and the journey to the other side of the frontier became a journey back into deep time.

Read more: Friday essay: when did Australia’s human history begin?

It’s no wonder the idea of big history was born here, or environmental history has been so innovative here. This is a land of a radically different ecology, where climatic variation and uncertainty have long been the norm – and are now intensifying. Australia’s long human history spans great climatic change and also offers a parable of cultural resilience.

Even the best northern-hemisphere scholars struggle to digest the implications of the Australian time revolution. They often assume, for example, “civilisation” is a term associated only with agriculture, and still insist 50,000 years is a possible horizon for modern humanity. Australia offers a distinctive and remarkable human saga for a world trying to come to terms with climate change and the rupture of the Anthropocene. Living on a precipice of deep time has become, I think, an exhilarating dimension of what it means to be Australian. Our nation’s obligation to honour the Uluru Statement is not just political; it is also metaphysical. It respects another ethical practice and another way of knowing.

Earthspeaking

In 2003, in its second issue, Griffith Review put the land at the centre of the nation. The edition was called Dreams of Land and it’s full of gold, including an essay by Ian Lowe sounding the alarm on the ecological and climate emergency – which reminds us how long we’ve had these eloquent warnings. As Graeme Davison said on launching the edition in December 2003:

At the threshold of the 21st century Australia has suddenly come down to earth. […] Earth, water, wind and fire are not just natural elements; they are increasingly the great issues of the day.

It is instructive to compare this issue of the Griffith Review, with the edition entitled Writing the Country , published 15 years later last summer. In the intervening decade and a half, sustainability morphed into survival, native title into Treaty and the Voice, the Anthropocene infiltrated our common vocabulary, the republic and Aboriginal recognition are no longer separable, and land decisively became Country with a capital “C”. In 2003 the reform hopes of the 1990s had not entirely died, but by 2019 it’s clear the dead hand of the Howard government and its successors has thoroughly throttled trust in the workings of the state.

Perhaps the most powerful contribution in GR2 – and it was given the honour of appearing first – was an essay by Melissa Lucashenko called “Not quite white in the head”. This year’s Miles Franklin winner, Lucashenko was already in great form in 2003. Tough, poetic and confronting, the words of her essay still resonate. Lucashenko writes of “earthspeaking”.

“I am earthspeaking,” she says, “talking about this place, my home and it is first, a very small story […] This earthspeaking is a small, quiet story in a human mouth.”

“Big stories are failing us as a nation,” suggests Lucashenko. “But we are citizens and inheritors and custodians of tiny landscapes too. It is the small stories that attach to these places […] which might help us find a way through.”

I think earthspeaking is a companion to thinking like a planet. Instead of beginning from the outside with a view of Earth in deep space and deep time, earthspeaking works from the ground up; it is inside-out; it begins with beloved Country. So it is with earthspeaking I want to finish.

Four months ago I was privileged to sit in a circle with Mithaka people, the traditional Aboriginal owners of 33,000 square kilometres of the Kirrenderi/Channel Country of the Lake Eyre Basin in south-western Queensland. In 2015, the Federal Court handed down a native title consent determination for the Mithaka enabling them to return to Country. Now they have begun a process of assessing and renewing their knowledge.

I was invited to be involved because I have studied the major white writer about this region, a woman called Alice Duncan-Kemp who was born on this land in 1901 where her family ran a cattle farm, and grew up with Mithaka people who worked on the station and were her carers and teachers. Young Alice spent her childhood days with her Aboriginal friends and teachers, especially Mary Ann and Moses Youlpee, who took her on walks and taught her the names and meanings and stories that connected every tree, bird, plant, animal, rock, dune and channel.

From the 1930s to the 1960s Alice wrote four books – half a million words – about the world of her childhood and the people and nature of the Channel Country, and although she did find a wide readership, her books were dismissed by authorities, landowners and locals as “romantic” and “nostalgic” and “fictional”.

Her writing was systematically marginalised: she was a woman in cattle country, a sympathiser with Aboriginal people, she refused to ignore the violence of the frontier and she challenged the typical heroic western style of narrative. The huge Kidman pastoral company bought her family’s land in 1998, bulldozed the historic pisé homestead into the creek, threw out the collection of Aboriginal artefacts, and continues to deny Alice’s writings have any historical authenticity. Yet her books were respected in the native title process and were crucial to the Mithaka in their fight to regain access to Country.

It was very moving to be present this year when Alice’s descendants and Moses’ people met for the first time. It was not just a social and symbolic occasion: we had come together as researchers and we had work to do. Across a weekend we pored over maps and talked through evidence, combining legend, memory, oral history, letters and manuscripts, published books, archaeological studies, surveyors’ records, and even recent drone footage of the remote terrain, all with the purpose of retrieving and reactivating knowledge, recovering language and reanimating Country. We could literally map Alice’s stories back onto features of the land, with the aim of bringing it under caring attention again.

This process is going on in beloved places right across the continent. Grace Karskens and Kim Mahood write beautifully in GR63 about similar quests, and of their hope written words dredged from the archive “might again be spoken as part of living language and shared geographies.”

Earthspeaking and thinking like a planet are profoundly linked. As the Indigenous speaker at the Melbourne Climate Strike said, “We stand for you when we stand for Country.” In these frightening and challenging times, we need radical storytelling and scholarly histories, narratives that weave together humans and nature, history and natural history, that move from Earth systems to the earth beneath our feet, from the lonely, living planet spinning through space to the intimately known and beloved local worlds over which we might, if we are lucky, exert some benevolent influence.

We need them not only because they help us to better understand our predicament, but also because they might enable us to act, with intelligence and grace.

This essay was adapted from the Showcase Lecture, Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, Griffith University, Queensland, Wednesday, 9 October 2019

- Climate change

- Anthropocene

- Friday essay

- Environmental history

- Greta Thunberg

- Extinction Rebellion

- Extinction crisis

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

Communications Coordinator

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

- CEO and Chairperson

- Focal Points

- Secretariat Staff

Stakeholder Engagement

- GEF Agencies

- Conventions

- Civil Society Organizations

- Private Sector

- Feature Stories

- Press Releases

- Publications

'By destroying nature we destroy ourselves'

Loss of nature carries a huge economic cost, but embracing it as a solution pays handsome dividends

The coronavirus might have its origins in the caves of Yunnan province, but make no mistake: nature did not create this crisis, we did. When we encroach on the natural world, we do more than cause environmental damage. The huge economic cost of the coronavirus pandemic is an illustration of a larger truth: we pay dearly when we destroy nature.

The emergence of COVID-19 might have appeared an act of nature, but it was entirely predictable. David Quammen explained why in his prophetic book, Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Pandemic , published in 2012. “We disrupt ecosystems, and we shake viruses loose from their natural hosts. When that happens, they need a new host. Often, we are it.”

New diseases, however, are just the beginning. From coastal erosion to the decline of natural resources such as fisheries and forests, the loss of nature carries a huge economic cost. WWF , the international conservation non-governmental organization, estimates that the total figure over the next 30 years could be as much as £8 trillion.

While some may disagree with the moral imperative to preserve the natural world, and the global commons, there can be no disagreement on the economic imperative of doing so, or the urgency of acting with speed and at scale. The economy, after all, is a wholly owned subsidiary of nature – not the other way around. And we are bankrupting it.

The more important question, therefore, is what we can do. There are, I think, two answers – and neither will succeed without the other.

The first is that we need to reset our relationship with nature by valuing it as the indispensable resource that it is. Rather than destroying our natural world, we need to apply “nature-based solutions” to our greatest challenges and create more robust resilience to systemic shocks in the future. Examples include the restoration of forests, wetlands, and peatlands in our countryside to help regulate water supply and protect communities from floods and landslides.

Other approaches include protecting and restoring coastal ecosystems such as reefs and salt marshes, which guard coasts from storm surges and erosion. For centuries, we have encroached on natural habitats, but through collective action we can help turn back that tide.

If we are to resolve the climate crisis, reduce inequality, maintain the wealth of nations and feed a growing global population, we must protect, restore, and sustainably manage nature. It is no longer enough for businesses to be “less bad,” or even “not bad.” We need to be good. We need to actively reverse the damage we have done.

Besides being the right thing to do, this also makes economic and financial sense. The cost of inaction is simply too high. The World Economic Forum’s Nature Risk Rising report has identified more than half of global GDP as moderately or highly dependent on nature.

Embracing nature as a solution is an investment, not a cost, and it is an investment that pays handsome dividends. Allowing a climate crisis to unfold is a risk that can be described, without overstatement, as existential.

The Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU) has shown that a $350 billion annual investment in climate solutions would unlock $4.5 trillion in new business opportunities and save $5.7 trillion of damage to people and the planet by 2030. The World Economic Forum has estimated that the nature-positive economy could create nearly 400 million jobs in the next 10 years.

Yet, with some exceptions, few countries and companies are integrating nature-based solutions in their strategies. They would be well advised to do so.

What is missing, then, is my second solution: enough ambitious leaders who are willing to take bold action. Recent data suggests that the likelihood of our overshooting our Paris climate targets within the next five years has doubled. As the summer fires in Brazil and Siberia remind us, we are running out of time to avert a runaway climate crisis.

So 2020 must be the year that leaders across the world step up to act with courage and urgency. And without putting nature and nature-based solutions front and center of decision-making, they will not be able to meet the 1.5C climate targets set in the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 or prevent a catastrophic loss of biodiversity in the “sixth great extinction."

Businesses have an indispensable role to play. First, they should get their own house in order, individually and collectively, by acting together across their value chains and with each other to become nature-positive and carbon-neutral – giving back to nature and the climate more than they take. Examples of this are underway in the fashion and food industry.

In Malaysia, Nestlé restored more than 2,400 hectares of native forest along the Kinabatangan River by incentivizing local people to plant trees. In Mongolia, the luxury fashion brand Kering reduced grazing pressure on native grasslands and lowered costs by teaching cashmere farmers innovative herding and packing methods.

Such initiatives are welcome, but there are too few of them. We need to expand and accelerate our efforts dramatically. Given the lack of effective governance so evident around the world today, we need more than ever courageous business leaders to speak up and advocate for the right actions and policies, to use their voice and commitment to derisk the needed, more ambitious political action.

I encourage all businesses to sign up to Business for Nature’s global campaign Nature is Everyone’s Business to do that and to join a powerful collective business voice calling on governments to reverse nature loss this decade.

While 2020 will forever be remembered as a year of pandemic, what will follow remains – for now – within our hands.

We have seen what happens when we make nature our enemy. If we instead make it our ally, helping us to help ourselves and in doing so create healthy societies, resilient economies and thriving businesses, we will have learnt the greatest lesson from this terrible period. The result will be a world that is not just safer, healthier and more equitable, but one that is prosperous too.

This piece was originally published for the GEF-Telegraph Partnership .

Investing in nature makes more sense than ever

Preserving nature is a strategic business imperative, to build a resilient world, we must go circular. here's how to do it, related news.

Connected technology is accelerating the green revolution

'We want to make Machu Picchu the first carbon neutral Wonder of the World'

The post-COVID environmental changes to aim for

Gef updates.

Subscribe to our distribution list to receive the GEF Newsletter.

A Summary and Analysis of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ‘Nature’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Nature’ is an 1836 essay by the American writer and thinker Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82). In this essay, Emerson explores the relationship between nature and humankind, arguing that if we approach nature with a poet’s eye, and a pure spirit, we will find the wonders of nature revealed to us.

You can read ‘Nature’ in full here . Below, we summarise Emerson’s argument and offer an analysis of its meaning and context.

Emerson begins his essay by defining nature, in philosophical terms, as anything that is not our individual souls. So our bodies, as well as all of the natural world, but also all of the world of art and technology, too, are ‘nature’ in this philosophical sense of the world. He urges his readers not to rely on tradition or history to help them to understand the world: instead, they should look to nature and the world around them.

In the first chapter, Emerson argues that nature is never ‘used up’ when the right mind examines it: it is a source of boundless curiosity. No man can own the landscape: it belongs, if it belongs to anyone at all, to ‘the poet’. Emerson argues that when a man returns to nature he can rediscover his lost youth, that wide-eyed innocence he had when he went among nature as a boy.

Emerson states that when he goes among nature, he becomes a ‘transparent eyeball’ because he sees nature but is himself nothing: he has been absorbed or subsumed into nature and, because God made nature, God himself. He feels a deep kinship and communion with all of nature. He acknowledges that our view of nature depends on our own mood, and that the natural world reflects the mood we are feeling at the time.

In the second chapter, Emerson focuses on ‘commodity’: the name he gives to all of the advantages which our senses owe to nature. Emerson draws a parallel with the ‘useful arts’ which have built houses and steamships and whole towns: these are the man-made equivalents of the natural world, in that both nature and the ‘arts’ are designed to provide benefit and use to mankind.

The third chapter then turns to ‘beauty’, and the beauty of nature comprises several aspects, which Emerson outlines. First, the beauty of nature is a restorative : seeing the sky when we emerge from a day’s work can restore us to ourselves and make us happy again. The human eye is the best ‘artist’ because it perceives and appreciates this beauty so keenly. Even the countryside in winter possesses its own beauty.

The second aspect of beauty Emerson considers is the spiritual element. Great actions in history are often accompanied by a beautiful backdrop provided by nature. The third aspect in which nature should be viewed is its value to the human intellect . Nature can help to inspire people to create and invent new things. Everything in nature is a representation of a universal harmony and perfection, something greater than itself.

In his fourth chapter, Emerson considers the relationship between nature and language. Our language is often a reflection of some natural state: for instance, the word right literally means ‘straight’, while wrong originally denoted something ‘twisted’. But we also turn to nature when we wish to use language to reflect a ‘spiritual fact’: for example, that a lamb symbolises innocence, or a fox represents cunning. Language represents nature, therefore, and nature in turn represents some spiritual truth.

Emerson argues that ‘the whole of nature is a metaphor of the human mind.’ Many great principles of the physical world are also ethical or moral axioms: for example, ‘the whole is greater than its part’.

In the fifth chapter, Emerson turns his attention to nature as a discipline . Its order can teach us spiritual and moral truths, but it also puts itself at the service of mankind, who can distinguish and separate (for instance, using water for drinking but wool for weaving, and so on). There is a unity in nature which means that every part of it corresponds to all of the other parts, much as an individual art – such as architecture – is related to the others, such as music or religion.

The sixth chapter is devoted to idealism . How can we sure nature does actually exist, and is not a mere product within ‘the apocalypse of the mind’, as Emerson puts it? He believes it doesn’t make any practical difference either way (but for his part, Emerson states that he believes God ‘never jests with us’, so nature almost certainly does have an external existence and reality).

Indeed, we can determine that we are separate from nature by changing out perspective in relation to it: for example, by bending down and looking between our legs, observing the landscape upside down rather than the way we usually view it. Emerson quotes from Shakespeare to illustrate how poets can draw upon nature to create symbols which reflect the emotions of the human soul. Religion and ethics, by contrast, degrade nature by viewing it as lesser than divine or moral truth.

Next, in the seventh chapter, Emerson considers nature and the spirit . Spirit, specifically the spirit of God, is present throughout nature. In his eighth and final chapter, ‘Prospects’, Emerson argues that we need to contemplate nature as a whole entity, arguing that ‘a dream may let us deeper into the secret of nature than a hundred concerted experiments’ which focus on more local details within nature.

Emerson concludes by arguing that in order to detect the unity and perfection within nature, we must first perfect our souls. ‘He cannot be a naturalist until he satisfies all the demands of the spirit’, Emerson urges. Wisdom means finding the miraculous within the common or everyday. He then urges the reader to build their own world, using their spirit as the foundation. Then the beauty of nature will reveal itself to us.

In a number of respects, Ralph Waldo Emerson puts forward a radically new attitude towards our relationship with nature. For example, although we may consider language to be man-made and artificial, Emerson demonstrates that the words and phrases we use to describe the world are drawn from our observation of nature. Nature and the human spirit are closely related, for Emerson, because they are both part of ‘the same spirit’: namely, God. Although we are separate from nature – or rather, our souls are separate from nature, as his prefatory remarks make clear – we can rediscover the common kinship between us and the world.

Emerson wrote ‘Nature’ in 1836, not long after Romanticism became an important literary, artistic, and philosophical movement in Europe and the United States. Like Wordsworth and the Romantics before him, Emerson argues that children have a better understanding of nature than adults, and when a man returns to nature he can rediscover his lost youth, that wide-eyed innocence he had when he went among nature as a boy.

And like Wordsworth, Emerson argued that to understand the world, we should go out there and engage with it ourselves, rather than relying on books and tradition to tell us what to think about it. In this connection, one could undertake a comparative analysis of Emerson’s ‘Nature’ and Wordsworth’s pair of poems ‘ Expostulation and Reply ’ and ‘ The Tables Turned ’, the former of which begins with a schoolteacher rebuking Wordsworth for sitting among nature rather than having his nose buried in a book:

‘Why, William, on that old gray stone, ‘Thus for the length of half a day, ‘Why, William, sit you thus alone, ‘And dream your time away?

‘Where are your books?—that light bequeathed ‘To beings else forlorn and blind! ‘Up! up! and drink the spirit breathed ‘From dead men to their kind.

Similarly, for Emerson, the poet and the dreamer can get closer to the true meaning of nature than scientists because they can grasp its unity by viewing it holistically, rather than focusing on analysing its rock formations or other more local details. All of this is in keeping with the philosophy of Transcendentalism , that nineteenth-century movement which argued for a kind of spiritual thinking instead of scientific thinking based narrowly on material things.

Emerson, along with Henry David Thoreau, was the most famous writer to belong to the Transcendentalist movement, and ‘Nature’ is fundamentally a Transcendentalist essay, arguing for an intuitive and ‘poetic’ engagement with nature in the round rather than a coldly scientific or empirical analysis of its component parts.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

How we must stop destroying nature

Filed under Coronavirus Climate Emergency

12 April 2021

At TTU we highlight cutting edge trends to alert leaders on why they must change how they think. We also share examples of great leadership and insights as an inspiration for others.

Here we publish a powerful alert on the urgent challenges we confront to save the planet that we all take for granted. The details and warnings are sobering. But none of us can afford to ignore them. To save nature we must all urgently change the way we conduct our lives.

This is an edited and shortened version of remarks delivered by Inger Andersen , Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) at the London School of Economics on 20 January 2021

As we seek to overcome this terrible pandemic, we must do so in the knowledge that it is not something that we can just fix, wash our hands of, and return to normal. Why? Because it is normal that brought us where we are today.

The pandemic has shown that we must rethink our very relationship with nature. It is our destruction of wild species, which is implicated in the emergence of the many diseases that jump from animals to humans, such as COVID-19.

The pandemic is a warning from the planet. Unless we change our ways, much worse lies in store. It’s a warning that we must heed. After years of promise - but not enough action - we must finally hear that warning and get on top of three planetary crises that threaten our collective future.

Existential crises

These are: the climate crisis, the biodiversity and nature crisis, and the pollution and waste crisis. These are three existential crises that threaten all of humanity.

In 2020 when we were consumed by the pandemic, climate change didn’t let up. 2020 was a year where we broke even, with both 2016 as the hottest year on record.

In 2020 we saw Atlantic hurricane season with more storms than ever recorded. We saw plagues of locusts from Yemen to East Africa, devouring our crops. We saw right now 2 billion people living in water stress. We’ve seen wildfires, floods, droughts. They have become so commonplace that many times they don’t even make the news.

And then there is the water, the biodiversity and nature crisis. Even as we talk about climate, we have to look at nature too, where our existence threatens nature severely.

Nature unravels

Nature is declining at an unprecedented speed. Around 1 million species of about 7.8 million that exist on our planet, are facing extinction. Humans have altered about 75% of the terrestrial surface of our planet. And we have altered about 66% of our oceans.

But while nature has intrinsic value, we also need to understand that nature’s loss is more than losing an orchid here, or a butterfly there. As we degrade our ecosystems, we are chipping away at the very foundations that make life possible.

Food, rainfall, temperature regulation, economic growth, pollination, the roofs over our heads, the clothes we wear, just to name but a few of nature’s services to us.

And then waste and pollution. There is that toxic trail of our economic growth. Every year pollution causes millions of premature deaths. Around one third of all rivers in Latin America, Asia and Africa suffer from severe pollution.

We throw away 50 million tonnes of electronic waste every year, roughly equal to the weight of all commercial airlines ever made.

The pandemic is obviously worsening the waste problem. Millions of disposable masks and PPE which we need making its way into the garbage stream.

We have known about these problems for some time. But the sad truth is that the world hasn’t acted strongly enough on the science before us.

That applies to the three planetary crisis and to every international agreement from the Sustainable Development Goals to the Paris Agreement to the Biodiversity Convention.

Failed commitments

Promises have been made. But now is the age of promises behind us. Now is the era of action.

As the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said in his State of the Planet speech in December 2020, making peace with nature is a defining task of the 21st century.

But the question is how to make that happen?

There are four areas where we can act: the economic and business sphere, governance, science and our everyday lives.

1. Economy and business

The starting point for making economic and business decisions that address the three planetary crisis is this. Instead of short term gain that brings long term pain, it is to recognise the true value of nature, and the Earth’s systems that regulate our seasons, our weather, our rainfall, and assures our very existence on this planet.

The Dasgupta review on the economics of biodiversity, makes clear that human health and prosperity cannot happen without nature. Over half of the global gross domestic product depends on nature.

Never mind the services that nature provides free of charge, such as climate regulation, water filtering, protection against natural disasters, and so on.

Economic benefit of biodiversity

Protecting nature and the climate, and limiting pollution and waste, is not only smart economic decision. Quite frankly they are non-negotiable for future economic prosperity.

But somehow, this seems to be a lesson that many have yet to learn. And it’s confounding to me.

It should be glaringly obvious that the old understanding that it’s economy versus environment just doesn’t hold true.

The increase in our wealth has come at the expense of our natural wealth, our natural capital, the planet stock of renewable and non renewable resources. They have declined by 40%.

In the same period, the WEF’s Global Risk Report 2020 ranked biodiversity and ecosystem collapse as one of the top five risks we would face within the next 10 years.

On the other hand, of course, ecosystems and biodiversity can bring huge economic benefits.

Overall the business opportunities from transforming the food, the land in the ocean systems could generate $3.6 trillion of additional revenue, while creating hundreds of millions of jobs.

Nature is an asset

So any way we slice and dice it, nature is an asset, an asset class that we need to think about. And we are eating into it much faster than it can regenerate.

To fix this error, we need to ensure that nature enters economic and financial decision making. We can’t assume that it is a free public good. The best way to assure that is one of the key ways is to move away from GDP as an indicator and use an inclusive wealth measure that measures all forms of capital.

The Global Commission on economy and climate told us that transitioning to low carbon growth could generate some $26 trillion and create over 65 million jobs by 2030. So tackling the three planetary crisis is a smart decision for economists and business.

2. Governance

Yes, the world has made many promises through the Sustainable Development Goals, through the Paris Agreement, through international goals and biodiversity and through goals on chemicals and pollution. But we haven’t done enough to move beyond the good intentions across the board.

Promises alone are not enough. Six years ago, nations arrived at this historic agreement in Paris to limit global warming this century to well below two degrees and to pursue 1.5. Yet now, our UNEP’s emissions gap report of December 2020 tells us that the pledges and actions under the Paris Agreement must get much stronger this year, or we are set towards a rise of over three degrees this century.

The pandemic-linked economic slowdown where we saw a dip in greenhouse gas emissions - yes, that did happen. But it will have a very, very, very negligible next-to-no-impact on global long term temperatures. That is because the CO2 bathtub was already full. So turning off the tap for a couple of seconds does not make it empty now.

Governments must deliver on commitments

To get back on track for a two degree world, we have no choice, but to cut one third of our emissions off by 2030. And if we want to, and we really do, aim for the 1.5 degree world, we have to halve our emissions.

It’s the same for biodiversity. In 2010 we agreed on a series of biodiversity targets that we had said we would reach by 2020. And by 2020 we have reached none of them. None!

So to catch up, governments must now act on three fronts. They must deliver on commitments made. They must strengthen and better focus their commitments. And they must ensure that actions on these three crises are joined up.

Clearly, the post pandemic recovery is a great way to speed up delivery. Every bit of UNEP research that we have produced in recent months shows us that for the pandemic recovery stimulus packages and this massive opportunity, never before have we put so much money - public money - into the economy.

We have calculated the potential to cut by around 25% our emissions by 2030 if we green these stimulus packages.

That would mean clearly ensuring that we do not borrow from the future generation and then leave them both with a broken planet and a mountain of debt.

What we therefore need to do is to put money into decarbonisation, into nature positive agriculture, into sustainable infrastructure, into climate change adaptation measures that protect the vulnerable, etc.

All-of-government dimension

That’s our target to make those recovery packages - stimulus packages – green on all fronts on all three crisis. And governments must make stronger, smarter and more trackable commitments right now.

So we need to be careful about not making just promises.

Like the person who pledges on January 1 to run a marathon by the end of the year, we have to get ready for that race. Net Zero commitments have been made. We celebrate that. But we cannot wait to turn these net zero commitments by 2050 into strong near term policies with time bound commitments that deliver action on the ground.

They must be included in what are called the NDC (Nationally Determined Contributions) which are essentially the plans that countries would submit under Paris every five years.

So let’s submit stronger and more determined NDC’s so that we ensure we fold in the stimulus promises they are in. And the same for biodiversity.

We need to ensure that these targets are made. That we shift towards better managed conservation areas, that we deliver nature positive agriculture and fisheries, that we end harmful subsidies, that we move to sustainable patterns of production and consumption.

And the same goes for chemicals. We need chemicals in our economy. But we have to use them safely.

What can governments do?

They need to act in a joined up manner between governments, business, communities and citizens. Think what that means - a cooler climate, that will protect biodiversity, slow desertification, conserve nature, drive down poverty, help provide healthier lives and a healthier nature, store carbon, create buffers to impact on climate change.

Each one reinforces the other. Governments need to understand this and not delegate to the ministries of environment, or one department or the other. They must have an all-of-government dimension to the action plans that they roll out.

Science has done its job. Science has spoken. But like with good economics, it now needs to get into policies so we can and must do better. Science has to seek and speak out. It must understand diverse opinions and experiences.

Here we must accept that like with economics, science has not done as good a job as it could have done. Science and the world have been woken up to covert, overt, quiet, blind racism, sexism, white privilege. It is important that science of today understands bias and tackles the realities and the histories of the community that it touches.

We at UNEP work in science and we are very much aware of this. So we work to make science open, make it accessible and make it available to all. We have to digitise scientific knowledge and democratise its availability, so that people can access it, understand it and use it.

Ensuring that science speaks within the four walls of our homes is also critical. Without strong science that travels we cannot influence unsustainable consumption and production patterns which underpin our planetary crisis. People need to understand the impact that they have on the planet.

4. Our everyday lives

The fourth area is the personal responsibility that each one of us carries. Often when I speak to people they say “Yes! But this is so big that my actions don’t matter”.

So let me disabuse you of that notion. The fact is that if we live in the developed world, we are impacting on the planetary health unless we live off grid and we grow our own food. And we live with a rainwater that we’ve harvested. And we don’t travel, which we don’t do, most of us. But two thirds - two thirds - of all greenhouse gas emissions are linked to private households while our growing demands of food and materials are stripping the earth bare.

So right now, we require 1.6 Earths to maintain the current population and living standards. And of course, living standards are rising as they should. Many people need to move beyond the poverty in which they are now living. This means that there is an onus on those of us living wealthier lives, globally speaking.

This is an equity issue. The combined emissions of the richest 1% of the global population account for more than twice of the poorest 50%. Let that sink in for a moment.

Everyone has a responsibility

This global elite have no alternatives but to reduce our footprint, and significantly. Very significantly, So that we can stay within the Paris targets.

And just to be clear, an annual salary of $40,000 puts you in the top 10 of global earners, while around $110,000 puts you in the top 1%. So the top 1%, the global elite is at $110,000. This means that each one of us - whether we are in the top 10 – has a responsibility.

So we’re not talking about the mega wealthy. We’re talking about a responsibility that falls on us all. Each one of us have to look at our own lives.

I’m not here going to list everything that we can do because information is freely available. Let’s be honest: most of us know what we must do, from avoiding single use plastic to avoiding food waste, to being mindful of our travel and dietary choices, etc, etc. and our overall footprint.

We have a systems problem

It can be difficult to make choices that are good for the planet, particularly for those who struggle to make ends meet. But our societies depend heavily on fossil fuels, monoculture crops, wasteful packaging, and so much more.

So it is essential that we change that system. We do that politically, but we do that also by the individual choices. And by voting with our pound bills, or dollar bills or euros.

This will take time. But until then, we have to do what we can within the constraints of our circumstances - no matter how small - to change our lifestyles.

There’s no doubt that we have made progress on environmental issues in the last few decades. And we’ve made more commitments than ever.