The writer of the academic essay aims to persuade readers of an idea based on evidence. The beginning of the essay is a crucial first step in this process. In order to engage readers and establish your authority, the beginning of your essay has to accomplish certain business. Your beginning should introduce the essay, focus it, and orient readers.

Introduce the Essay. The beginning lets your readers know what the essay is about, the topic . The essay's topic does not exist in a vacuum, however; part of letting readers know what your essay is about means establishing the essay's context , the frame within which you will approach your topic. For instance, in an essay about the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech, the context may be a particular legal theory about the speech right; it may be historical information concerning the writing of the amendment; it may be a contemporary dispute over flag burning; or it may be a question raised by the text itself. The point here is that, in establishing the essay's context, you are also limiting your topic. That is, you are framing an approach to your topic that necessarily eliminates other approaches. Thus, when you determine your context, you simultaneously narrow your topic and take a big step toward focusing your essay. Here's an example.

The paragraph goes on. But as you can see, Chopin's novel (the topic) is introduced in the context of the critical and moral controversy its publication engendered.

Focus the Essay. Beyond introducing your topic, your beginning must also let readers know what the central issue is. What question or problem will you be thinking about? You can pose a question that will lead to your idea (in which case, your idea will be the answer to your question), or you can make a thesis statement. Or you can do both: you can ask a question and immediately suggest the answer that your essay will argue. Here's an example from an essay about Memorial Hall.

The fullness of your idea will not emerge until your conclusion, but your beginning must clearly indicate the direction your idea will take, must set your essay on that road. And whether you focus your essay by posing a question, stating a thesis, or combining these approaches, by the end of your beginning, readers should know what you're writing about, and why —and why they might want to read on.

Orient Readers. Orienting readers, locating them in your discussion, means providing information and explanations wherever necessary for your readers' understanding. Orienting is important throughout your essay, but it is crucial in the beginning. Readers who don't have the information they need to follow your discussion will get lost and quit reading. (Your teachers, of course, will trudge on.) Supplying the necessary information to orient your readers may be as simple as answering the journalist's questions of who, what, where, when, how, and why. It may mean providing a brief overview of events or a summary of the text you'll be analyzing. If the source text is brief, such as the First Amendment, you might just quote it. If the text is well known, your summary, for most audiences, won't need to be more than an identifying phrase or two:

Often, however, you will want to summarize your source more fully so that readers can follow your analysis of it.

Questions of Length and Order. How long should the beginning be? The length should be proportionate to the length and complexity of the whole essay. For instance, if you're writing a five-page essay analyzing a single text, your beginning should be brief, no more than one or two paragraphs. On the other hand, it may take a couple of pages to set up a ten-page essay.

Does the business of the beginning have to be addressed in a particular order? No, but the order should be logical. Usually, for instance, the question or statement that focuses the essay comes at the end of the beginning, where it serves as the jumping-off point for the middle, or main body, of the essay. Topic and context are often intertwined, but the context may be established before the particular topic is introduced. In other words, the order in which you accomplish the business of the beginning is flexible and should be determined by your purpose.

Opening Strategies. There is still the further question of how to start. What makes a good opening? You can start with specific facts and information, a keynote quotation, a question, an anecdote, or an image. But whatever sort of opening you choose, it should be directly related to your focus. A snappy quotation that doesn't help establish the context for your essay or that later plays no part in your thinking will only mislead readers and blur your focus. Be as direct and specific as you can be. This means you should avoid two types of openings:

- The history-of-the-world (or long-distance) opening, which aims to establish a context for the essay by getting a long running start: "Ever since the dawn of civilized life, societies have struggled to reconcile the need for change with the need for order." What are we talking about here, political revolution or a new brand of soft drink? Get to it.

- The funnel opening (a variation on the same theme), which starts with something broad and general and "funnels" its way down to a specific topic. If your essay is an argument about state-mandated prayer in public schools, don't start by generalizing about religion; start with the specific topic at hand.

Remember. After working your way through the whole draft, testing your thinking against the evidence, perhaps changing direction or modifying the idea you started with, go back to your beginning and make sure it still provides a clear focus for the essay. Then clarify and sharpen your focus as needed. Clear, direct beginnings rarely present themselves ready-made; they must be written, and rewritten, into the sort of sharp-eyed clarity that engages readers and establishes your authority.

Copyright 1999, Patricia Kain, for the Writing Center at Harvard University

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Essay Writing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource begins with a general description of essay writing and moves to a discussion of common essay genres students may encounter across the curriculum. The four genres of essays (description, narration, exposition, and argumentation) are common paper assignments you may encounter in your writing classes. Although these genres, also known as the modes of discourse, have been criticized by some composition scholars, the Purdue OWL recognizes the wide spread use of these genres and students’ need to understand and produce these types of essays. We hope these resources will help.

The essay is a commonly assigned form of writing that every student will encounter while in academia. Therefore, it is wise for the student to become capable and comfortable with this type of writing early on in her training.

Essays can be a rewarding and challenging type of writing and are often assigned either to be done in class, which requires previous planning and practice (and a bit of creativity) on the part of the student, or as homework, which likewise demands a certain amount of preparation. Many poorly crafted essays have been produced on account of a lack of preparation and confidence. However, students can avoid the discomfort often associated with essay writing by understanding some common genres.

Before delving into its various genres, let’s begin with a basic definition of the essay.

What is an essay?

Though the word essay has come to be understood as a type of writing in Modern English, its origins provide us with some useful insights. The word comes into the English language through the French influence on Middle English; tracing it back further, we find that the French form of the word comes from the Latin verb exigere , which means "to examine, test, or (literally) to drive out." Through the excavation of this ancient word, we are able to unearth the essence of the academic essay: to encourage students to test or examine their ideas concerning a particular topic.

Essays are shorter pieces of writing that often require the student to hone a number of skills such as close reading, analysis, comparison and contrast, persuasion, conciseness, clarity, and exposition. As is evidenced by this list of attributes, there is much to be gained by the student who strives to succeed at essay writing.

The purpose of an essay is to encourage students to develop ideas and concepts in their writing with the direction of little more than their own thoughts (it may be helpful to view the essay as the converse of a research paper). Therefore, essays are (by nature) concise and require clarity in purpose and direction. This means that there is no room for the student’s thoughts to wander or stray from his or her purpose; the writing must be deliberate and interesting.

This handout should help students become familiar and comfortable with the process of essay composition through the introduction of some common essay genres.

This handout includes a brief introduction to the following genres of essay writing:

- Expository essays

- Descriptive essays

- Narrative essays

- Argumentative (Persuasive) essays

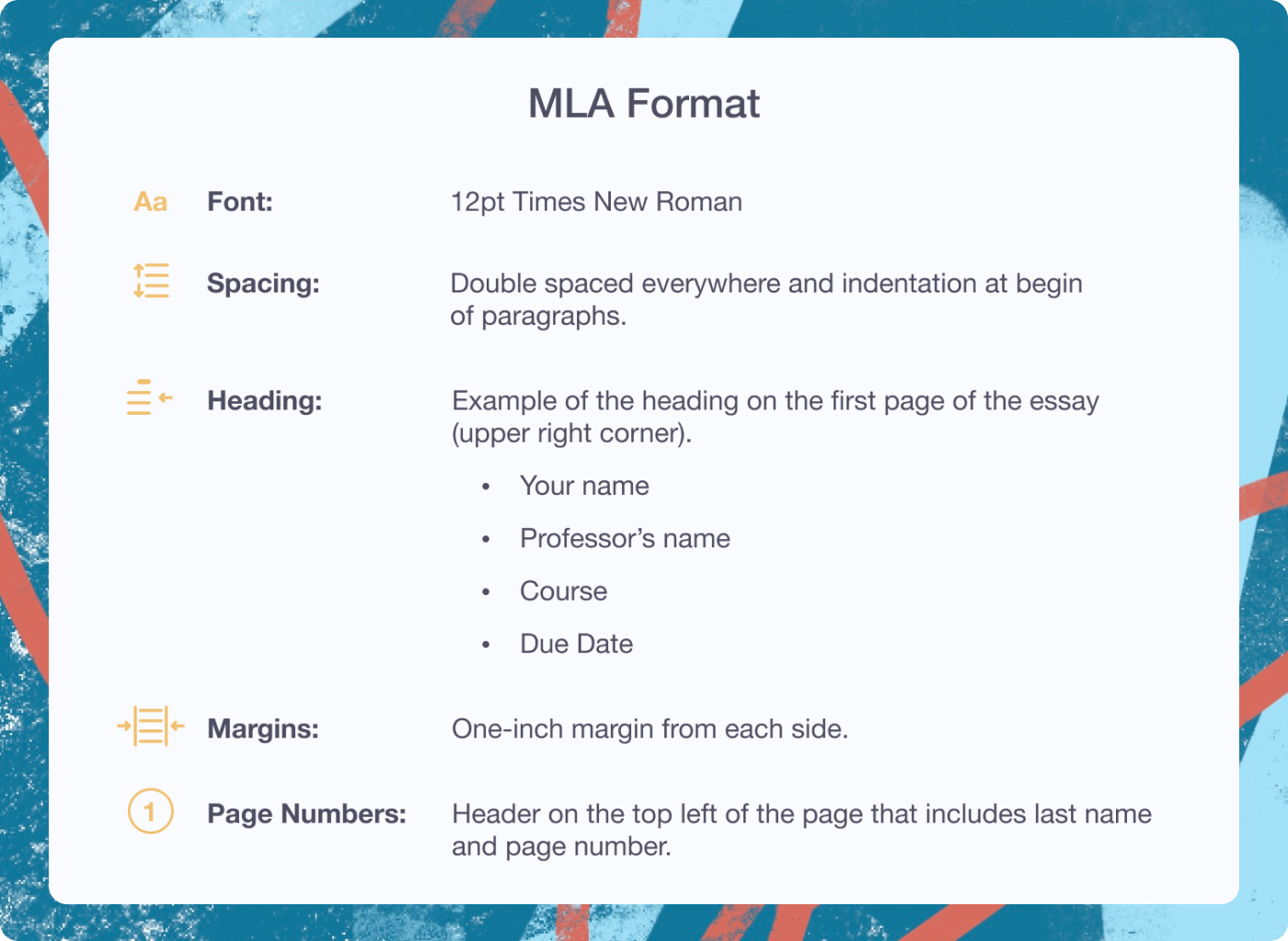

Learn the Standard Essay Format: MLA, APA, Chicago Styles

Being able to write an essay is a vital part of any student's education. However, it's not just about linearly listing ideas. A lot of institutions will require a certain format that your paper must follow; prime examples would be one of a basic essay format like MLA, the APA, and the Chicago formats. This article will explain the differences between the MLA format, the APA format, and the Chicago format. The application of these could range from high school to college essays, and they stand as the standard of college essay formatting. EssayPro — dissertation services , that will help to make a difference!

What is an Essay Format: Structure

Be it an academic, informative or a specific extended essay - structure is essential. For example, the IB extended essay has very strict requirements that are followed by an assigned academic style of writing (primarily MLA, APA, or Chicago):

This outline format for an extended essay is a great example to follow when writing a research essay, and sustaining a proper research essay format - especially if it is based on the MLA guidelines. It is vital to remember that the student must keep track of their resources to apply them to each step outlined above easily. And check out some tips on how to write an essay introduction .

Lost in the Labyrinth of Essay Formatting?

Navigate the complexities of essay structures with ease. Let our experts guide your paper to the format it deserves!

How to Format an Essay (MLA)

To write an essay in MLA format, one must follow a basic set of guidelines and instructions. This is a step by step from our business essay writing service.

Essay in MLA Format Example

Mla vs. apa.

Before we move on to the APA essay format, it is important to distinguish the two types of formatting. Let’s go through the similarities first:

- The formatting styles are similar: spacing, citation, indentation.

- All of the information that is used within the essay must be present within the works cited page (in APA, that’s called a reference page)

- Both use the parenthetical citations within the body of the paper, usually to show a certain quote or calculation.

- Citations are listed alphabetically on the works cited / reference page.

What you need to know about the differences is not extensive, thankfully:

- MLA style is mostly used in humanities, while APA style is focused more on social sciences. The list of sources has a different name (works cited - MLA / references - APA)

- Works cited differ on the way they display the name of the original content (MLA -> Yorke, Thom / APA -> Yorke T.)

- When using an in-text citation, and the author’s name is listed within the sentence, place the page number found at the end: “Yorke believes that Creep was Radiohead’s worst song. (4).” APA, on the other hand, requires that a year is to be inserted: “According to Yorke (2013), Creep was a mess.”

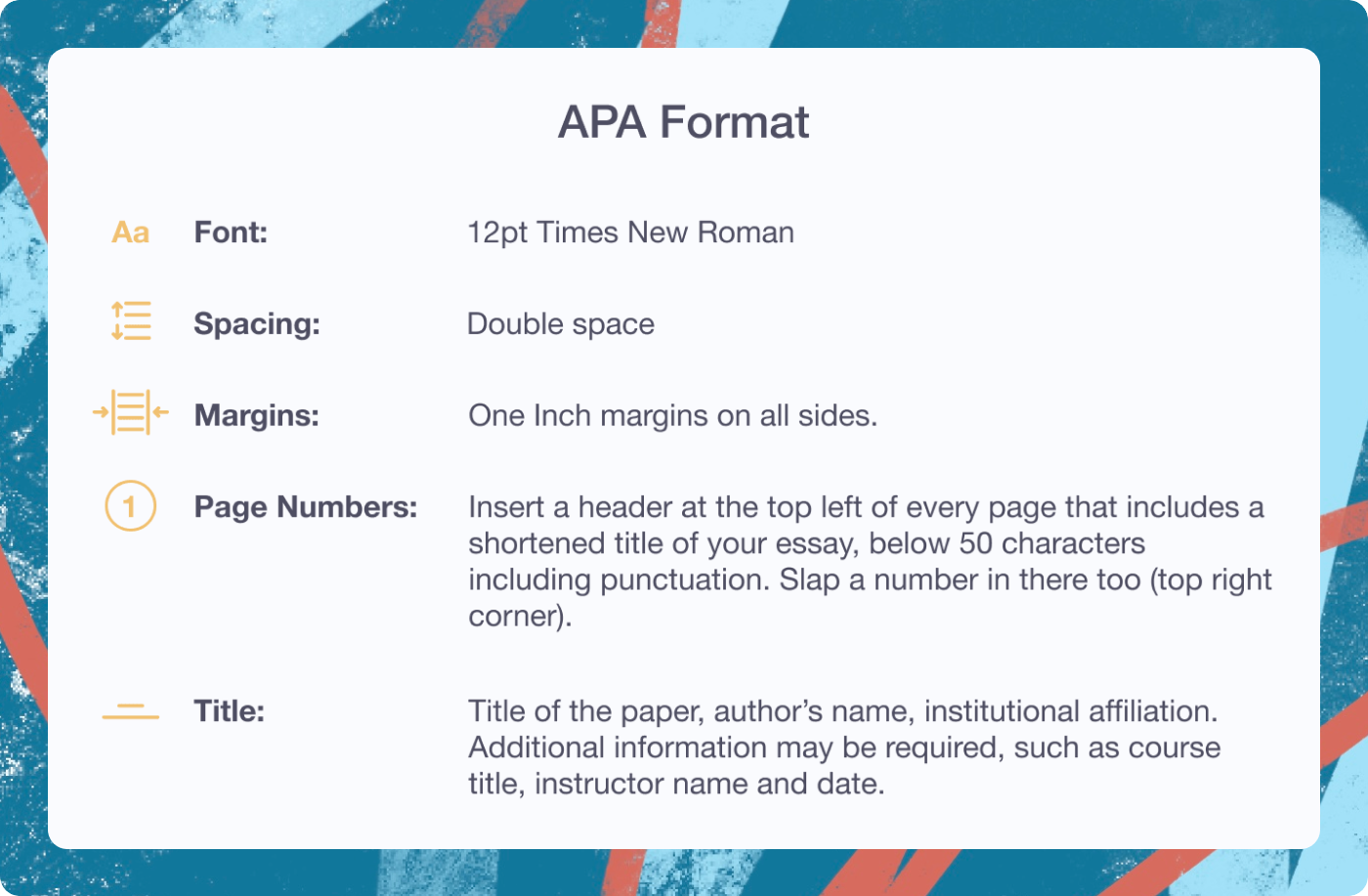

Alright, let’s carry over to the APA style specifics.

Order an Essay Now & and We Will Cite and Format It For Free :

How to format an essay (apa).

The APA scheme is one of the most common college essay formats, so being familiar with its requirements is crucial. In a basic APA format structure, we can apply a similar list of guidelines as we did in the MLA section:

If you ask yourself how to format an essay, you can always turn to us and request to write or rewrite essay in APA format if you find it difficult or don't have time.

Note that some teachers and professors may request deviations from some of the characteristics that the APA format originally requires, such as those listed above.

If you think: 'I want someone write a research paper for me ', you can do it at Essaypro.

Essay in APA Format Example

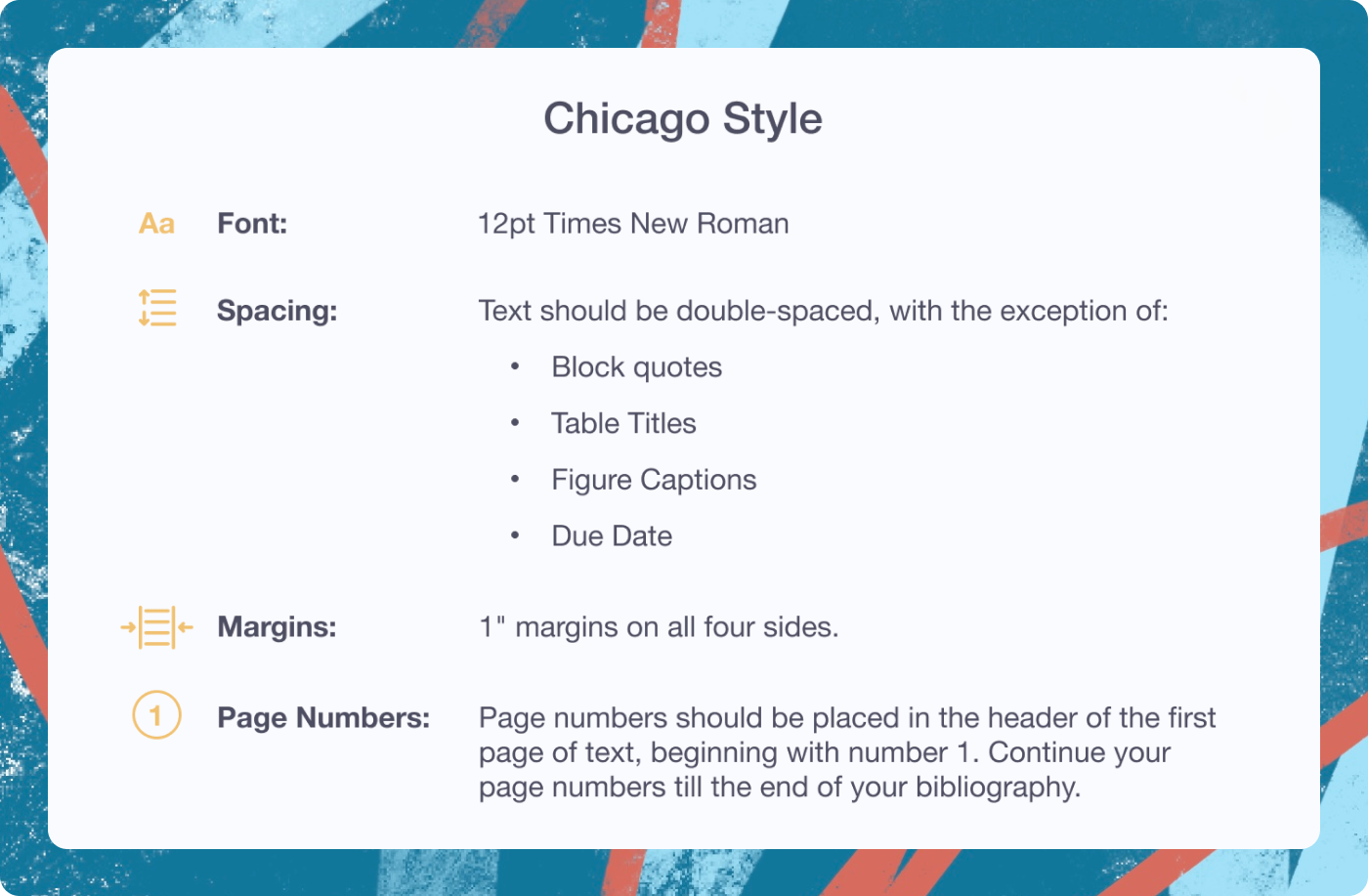

Apa format chronobiology, chicago style.

The usage of Chicago style is prevalent in academic writing that focuses on the source of origin. This means that precise citations and footnotes are key to a successful paper.

Chicago Style Essay Format

The same bullet point structure can be applied to the Chicago essay format.

Tips for Writing an Academic Paper

There isn’t one proper way of writing a paper, but there are solid guidelines to sustain a consistent workflow. Be it a college application essay, a research paper, informative essay, etc. There is a standard essay format that you should follow. For easier access, the following outline will be divided into steps:

Choose a Good Topic

A lot of students struggle with picking a good topic for their essays. The topic you choose should be specific enough so you can explore it in its entirety and hit your word limit if that’s a variable you worry about. With a good topic that should not be a problem. On the other hand, it should not be so broad that some resources would outweigh the information you could squeeze into one paper. Don’t be too specific, or you will find that there is a shortage of information, but don’t be too broad or you will feel overwhelmed. Don’t hesitate to ask your instructor for help with your essay writing.

Start Research as Soon as Possible

Before you even begin writing, make sure that you are acquainted with the information that you are working with. Find compelling arguments and counterpoints, trivia, facts, etc. The sky is the limit when it comes to gathering information.

Pick out Specific, Compelling Resources

When you feel acquainted with the subject, you should be able to have a basic conversation on the matter. Pick out resources that have been bookmarked, saved or are very informative and start extracting information. You will need all you can get to put into the citations at the end of your paper. Stash books, websites, articles and have them ready to cite. See if you can subtract or expand your scope of research.

Create an Outline

Always have a plan. This might be the most important phase of the process. If you have a strong essay outline and you have a particular goal in mind, it’ll be easy to refer to it when you might get stuck somewhere in the middle of the paper. And since you have direct links from the research you’ve done beforehand, the progress is guaranteed to be swift. Having a list of keywords, if applicable, will surely boost the informational scope. With keywords specific to the subject matter of each section, it should be much easier to identify its direction and possible informational criteria.

Write a Draft

Before you jot anything down into the body of your essay, make sure that the outline has enough information to back up whatever statement you choose to explore. Do not be afraid of letting creativity into your paper (within reason, of course) and explore the possibilities. Start with a standard 5 paragraph structure, and the content will come with time.

Ask for a Peer Review of Your Academic Paper

Before you know it, the draft is done, and it’s ready to be sent out for peer review. Ask a classmate, a relative or even a specialist if they are willing to contribute. Get as much feedback as you possibly can and work on it.

Final Draft

Before handing in the final draft, go over it at least one more time, focusing on smaller mistakes like grammar and punctuation. Make sure that what you wrote follows proper essay structure. Learn more about argumentative essay structure on our blog. If you need a second pair of eyes, get help from our service.

Want Your Essay to Stand Out in Structure and Style?

Don't let poor formatting overshadow your ideas. Find your essay on sale and ensure your paper gets the professional polish it deserves!

What Is Essay Format?

How to format a college essay, how to write an essay in mla format.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 177 college essay examples for 11 schools + expert analysis.

College Admissions , College Essays

The personal statement might just be the hardest part of your college application. Mostly this is because it has the least guidance and is the most open-ended. One way to understand what colleges are looking for when they ask you to write an essay is to check out the essays of students who already got in—college essays that actually worked. After all, they must be among the most successful of this weird literary genre.

In this article, I'll go through general guidelines for what makes great college essays great. I've also compiled an enormous list of 100+ actual sample college essays from 11 different schools. Finally, I'll break down two of these published college essay examples and explain why and how they work. With links to 177 full essays and essay excerpts , this article is a great resource for learning how to craft your own personal college admissions essay!

What Excellent College Essays Have in Common

Even though in many ways these sample college essays are very different from one other, they do share some traits you should try to emulate as you write your own essay.

Visible Signs of Planning

Building out from a narrow, concrete focus. You'll see a similar structure in many of the essays. The author starts with a very detailed story of an event or description of a person or place. After this sense-heavy imagery, the essay expands out to make a broader point about the author, and connects this very memorable experience to the author's present situation, state of mind, newfound understanding, or maturity level.

Knowing how to tell a story. Some of the experiences in these essays are one-of-a-kind. But most deal with the stuff of everyday life. What sets them apart is the way the author approaches the topic: analyzing it for drama and humor, for its moving qualities, for what it says about the author's world, and for how it connects to the author's emotional life.

Stellar Execution

A killer first sentence. You've heard it before, and you'll hear it again: you have to suck the reader in, and the best place to do that is the first sentence. Great first sentences are punchy. They are like cliffhangers, setting up an exciting scene or an unusual situation with an unclear conclusion, in order to make the reader want to know more. Don't take my word for it—check out these 22 first sentences from Stanford applicants and tell me you don't want to read the rest of those essays to find out what happens!

A lively, individual voice. Writing is for readers. In this case, your reader is an admissions officer who has read thousands of essays before yours and will read thousands after. Your goal? Don't bore your reader. Use interesting descriptions, stay away from clichés, include your own offbeat observations—anything that makes this essay sounds like you and not like anyone else.

Technical correctness. No spelling mistakes, no grammar weirdness, no syntax issues, no punctuation snafus—each of these sample college essays has been formatted and proofread perfectly. If this kind of exactness is not your strong suit, you're in luck! All colleges advise applicants to have their essays looked over several times by parents, teachers, mentors, and anyone else who can spot a comma splice. Your essay must be your own work, but there is absolutely nothing wrong with getting help polishing it.

And if you need more guidance, connect with PrepScholar's expert admissions consultants . These expert writers know exactly what college admissions committees look for in an admissions essay and chan help you craft an essay that boosts your chances of getting into your dream school.

Check out PrepScholar's Essay Editing and Coaching progra m for more details!

Links to Full College Essay Examples

Some colleges publish a selection of their favorite accepted college essays that worked, and I've put together a selection of over 100 of these.

Common App Essay Samples

Please note that some of these college essay examples may be responding to prompts that are no longer in use. The current Common App prompts are as follows:

1. Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story. 2. The lessons we take from obstacles we encounter can be fundamental to later success. Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. How did it affect you, and what did you learn from the experience? 3. Reflect on a time when you questioned or challenged a belief or idea. What prompted your thinking? What was the outcome? 4. Reflect on something that someone has done for you that has made you happy or thankful in a surprising way. How has this gratitude affected or motivated you? 5. Discuss an accomplishment, event, or realization that sparked a period of personal growth and a new understanding of yourself or others. 6. Describe a topic, idea, or concept you find so engaging that it makes you lose all track of time. Why does it captivate you? What or who do you turn to when you want to learn more?

7. Share an essay on any topic of your choice. It can be one you've already written, one that responds to a different prompt, or one of your own design.

Now, let's get to the good stuff: the list of 177 college essay examples responding to current and past Common App essay prompts.

Connecticut college.

- 12 Common Application essays from the classes of 2022-2025

Hamilton College

- 7 Common Application essays from the class of 2026

- 7 Common Application essays from the class of 2022

- 7 Common Application essays from the class of 2018

- 8 Common Application essays from the class of 2012

- 8 Common Application essays from the class of 2007

Johns Hopkins

These essays are answers to past prompts from either the Common Application or the Coalition Application (which Johns Hopkins used to accept).

- 1 Common Application or Coalition Application essay from the class of 2026

- 6 Common Application or Coalition Application essays from the class of 2025

- 6 Common Application or Universal Application essays from the class of 2024

- 6 Common Application or Universal Application essays from the class of 2023

- 7 Common Application of Universal Application essays from the class of 2022

- 5 Common Application or Universal Application essays from the class of 2021

- 7 Common Application or Universal Application essays from the class of 2020

Essay Examples Published by Other Websites

- 2 Common Application essays ( 1st essay , 2nd essay ) from applicants admitted to Columbia

Other Sample College Essays

Here is a collection of essays that are college-specific.

Babson College

- 4 essays (and 1 video response) on "Why Babson" from the class of 2020

Emory University

- 5 essay examples ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) from the class of 2020 along with analysis from Emory admissions staff on why the essays were exceptional

- 5 more recent essay examples ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) along with analysis from Emory admissions staff on what made these essays stand out

University of Georgia

- 1 “strong essay” sample from 2019

- 1 “strong essay” sample from 2018

- 10 Harvard essays from 2023

- 10 Harvard essays from 2022

- 10 Harvard essays from 2021

- 10 Harvard essays from 2020

- 10 Harvard essays from 2019

- 10 Harvard essays from 2018

- 6 essays from admitted MIT students

Smith College

- 6 "best gift" essays from the class of 2018

Books of College Essays

If you're looking for even more sample college essays, consider purchasing a college essay book. The best of these include dozens of essays that worked and feedback from real admissions officers.

College Essays That Made a Difference —This detailed guide from Princeton Review includes not only successful essays, but also interviews with admissions officers and full student profiles.

50 Successful Harvard Application Essays by the Staff of the Harvard Crimson—A must for anyone aspiring to Harvard .

50 Successful Ivy League Application Essays and 50 Successful Stanford Application Essays by Gen and Kelly Tanabe—For essays from other top schools, check out this venerated series, which is regularly updated with new essays.

Heavenly Essays by Janine W. Robinson—This collection from the popular blogger behind Essay Hell includes a wider range of schools, as well as helpful tips on honing your own essay.

Analyzing Great Common App Essays That Worked

I've picked two essays from the examples collected above to examine in more depth so that you can see exactly what makes a successful college essay work. Full credit for these essays goes to the original authors and the schools that published them.

Example 1: "Breaking Into Cars," by Stephen, Johns Hopkins Class of '19 (Common App Essay, 636 words long)

I had never broken into a car before.

We were in Laredo, having just finished our first day at a Habitat for Humanity work site. The Hotchkiss volunteers had already left, off to enjoy some Texas BBQ, leaving me behind with the college kids to clean up. Not until we were stranded did we realize we were locked out of the van.

Someone picked a coat hanger out of the dumpster, handed it to me, and took a few steps back.

"Can you do that thing with a coat hanger to unlock it?"

"Why me?" I thought.

More out of amusement than optimism, I gave it a try. I slid the hanger into the window's seal like I'd seen on crime shows, and spent a few minutes jiggling the apparatus around the inside of the frame. Suddenly, two things simultaneously clicked. One was the lock on the door. (I actually succeeded in springing it.) The other was the realization that I'd been in this type of situation before. In fact, I'd been born into this type of situation.

My upbringing has numbed me to unpredictability and chaos. With a family of seven, my home was loud, messy, and spottily supervised. My siblings arguing, the dog barking, the phone ringing—all meant my house was functioning normally. My Dad, a retired Navy pilot, was away half the time. When he was home, he had a parenting style something like a drill sergeant. At the age of nine, I learned how to clear burning oil from the surface of water. My Dad considered this a critical life skill—you know, in case my aircraft carrier should ever get torpedoed. "The water's on fire! Clear a hole!" he shouted, tossing me in the lake without warning. While I'm still unconvinced about that particular lesson's practicality, my Dad's overarching message is unequivocally true: much of life is unexpected, and you have to deal with the twists and turns.

Living in my family, days rarely unfolded as planned. A bit overlooked, a little pushed around, I learned to roll with reality, negotiate a quick deal, and give the improbable a try. I don't sweat the small stuff, and I definitely don't expect perfect fairness. So what if our dining room table only has six chairs for seven people? Someone learns the importance of punctuality every night.

But more than punctuality and a special affinity for musical chairs, my family life has taught me to thrive in situations over which I have no power. Growing up, I never controlled my older siblings, but I learned how to thwart their attempts to control me. I forged alliances, and realigned them as necessary. Sometimes, I was the poor, defenseless little brother; sometimes I was the omniscient elder. Different things to different people, as the situation demanded. I learned to adapt.

Back then, these techniques were merely reactions undertaken to ensure my survival. But one day this fall, Dr. Hicks, our Head of School, asked me a question that he hoped all seniors would reflect on throughout the year: "How can I participate in a thing I do not govern, in the company of people I did not choose?"

The question caught me off guard, much like the question posed to me in Laredo. Then, I realized I knew the answer. I knew why the coat hanger had been handed to me.

Growing up as the middle child in my family, I was a vital participant in a thing I did not govern, in the company of people I did not choose. It's family. It's society. And often, it's chaos. You participate by letting go of the small stuff, not expecting order and perfection, and facing the unexpected with confidence, optimism, and preparedness. My family experience taught me to face a serendipitous world with confidence.

What Makes This Essay Tick?

It's very helpful to take writing apart in order to see just how it accomplishes its objectives. Stephen's essay is very effective. Let's find out why!

An Opening Line That Draws You In

In just eight words, we get: scene-setting (he is standing next to a car about to break in), the idea of crossing a boundary (he is maybe about to do an illegal thing for the first time), and a cliffhanger (we are thinking: is he going to get caught? Is he headed for a life of crime? Is he about to be scared straight?).

Great, Detailed Opening Story

More out of amusement than optimism, I gave it a try. I slid the hanger into the window's seal like I'd seen on crime shows, and spent a few minutes jiggling the apparatus around the inside of the frame.

It's the details that really make this small experience come alive. Notice how whenever he can, Stephen uses a more specific, descriptive word in place of a more generic one. The volunteers aren't going to get food or dinner; they're going for "Texas BBQ." The coat hanger comes from "a dumpster." Stephen doesn't just move the coat hanger—he "jiggles" it.

Details also help us visualize the emotions of the people in the scene. The person who hands Stephen the coat hanger isn't just uncomfortable or nervous; he "takes a few steps back"—a description of movement that conveys feelings. Finally, the detail of actual speech makes the scene pop. Instead of writing that the other guy asked him to unlock the van, Stephen has the guy actually say his own words in a way that sounds like a teenager talking.

Turning a Specific Incident Into a Deeper Insight

Suddenly, two things simultaneously clicked. One was the lock on the door. (I actually succeeded in springing it.) The other was the realization that I'd been in this type of situation before. In fact, I'd been born into this type of situation.

Stephen makes the locked car experience a meaningful illustration of how he has learned to be resourceful and ready for anything, and he also makes this turn from the specific to the broad through an elegant play on the two meanings of the word "click."

Using Concrete Examples When Making Abstract Claims

My upbringing has numbed me to unpredictability and chaos. With a family of seven, my home was loud, messy, and spottily supervised. My siblings arguing, the dog barking, the phone ringing—all meant my house was functioning normally.

"Unpredictability and chaos" are very abstract, not easily visualized concepts. They could also mean any number of things—violence, abandonment, poverty, mental instability. By instantly following up with highly finite and unambiguous illustrations like "family of seven" and "siblings arguing, the dog barking, the phone ringing," Stephen grounds the abstraction in something that is easy to picture: a large, noisy family.

Using Small Bits of Humor and Casual Word Choice

My Dad, a retired Navy pilot, was away half the time. When he was home, he had a parenting style something like a drill sergeant. At the age of nine, I learned how to clear burning oil from the surface of water. My Dad considered this a critical life skill—you know, in case my aircraft carrier should ever get torpedoed.

Obviously, knowing how to clean burning oil is not high on the list of things every 9-year-old needs to know. To emphasize this, Stephen uses sarcasm by bringing up a situation that is clearly over-the-top: "in case my aircraft carrier should ever get torpedoed."

The humor also feels relaxed. Part of this is because he introduces it with the colloquial phrase "you know," so it sounds like he is talking to us in person. This approach also diffuses the potential discomfort of the reader with his father's strictness—since he is making jokes about it, clearly he is OK. Notice, though, that this doesn't occur very much in the essay. This helps keep the tone meaningful and serious rather than flippant.

An Ending That Stretches the Insight Into the Future

But one day this fall, Dr. Hicks, our Head of School, asked me a question that he hoped all seniors would reflect on throughout the year: "How can I participate in a thing I do not govern, in the company of people I did not choose?"

The ending of the essay reveals that Stephen's life has been one long preparation for the future. He has emerged from chaos and his dad's approach to parenting as a person who can thrive in a world that he can't control.

This connection of past experience to current maturity and self-knowledge is a key element in all successful personal essays. Colleges are very much looking for mature, self-aware applicants. These are the qualities of successful college students, who will be able to navigate the independence college classes require and the responsibility and quasi-adulthood of college life.

What Could This Essay Do Even Better?

Even the best essays aren't perfect, and even the world's greatest writers will tell you that writing is never "finished"—just "due." So what would we tweak in this essay if we could?

Replace some of the clichéd language. Stephen uses handy phrases like "twists and turns" and "don't sweat the small stuff" as a kind of shorthand for explaining his relationship to chaos and unpredictability. But using too many of these ready-made expressions runs the risk of clouding out your own voice and replacing it with something expected and boring.

Use another example from recent life. Stephen's first example (breaking into the van in Laredo) is a great illustration of being resourceful in an unexpected situation. But his essay also emphasizes that he "learned to adapt" by being "different things to different people." It would be great to see how this plays out outside his family, either in the situation in Laredo or another context.

Example 2: By Renner Kwittken, Tufts Class of '23 (Common App Essay, 645 words long)

My first dream job was to be a pickle truck driver. I saw it in my favorite book, Richard Scarry's "Cars and Trucks and Things That Go," and for some reason, I was absolutely obsessed with the idea of driving a giant pickle. Much to the discontent of my younger sister, I insisted that my parents read us that book as many nights as possible so we could find goldbug, a small little golden bug, on every page. I would imagine the wonderful life I would have: being a pig driving a giant pickle truck across the country, chasing and finding goldbug. I then moved on to wanting to be a Lego Master. Then an architect. Then a surgeon.

Then I discovered a real goldbug: gold nanoparticles that can reprogram macrophages to assist in killing tumors, produce clear images of them without sacrificing the subject, and heat them to obliteration.

Suddenly the destination of my pickle was clear.

I quickly became enveloped by the world of nanomedicine; I scoured articles about liposomes, polymeric micelles, dendrimers, targeting ligands, and self-assembling nanoparticles, all conquering cancer in some exotic way. Completely absorbed, I set out to find a mentor to dive even deeper into these topics. After several rejections, I was immensely grateful to receive an invitation to work alongside Dr. Sangeeta Ray at Johns Hopkins.

In the lab, Dr. Ray encouraged a great amount of autonomy to design and implement my own procedures. I chose to attack a problem that affects the entire field of nanomedicine: nanoparticles consistently fail to translate from animal studies into clinical trials. Jumping off recent literature, I set out to see if a pre-dose of a common chemotherapeutic could enhance nanoparticle delivery in aggressive prostate cancer, creating three novel constructs based on three different linear polymers, each using fluorescent dye (although no gold, sorry goldbug!). Though using radioactive isotopes like Gallium and Yttrium would have been incredible, as a 17-year-old, I unfortunately wasn't allowed in the same room as these radioactive materials (even though I took a Geiger counter to a pair of shoes and found them to be slightly dangerous).

I hadn't expected my hypothesis to work, as the research project would have ideally been led across two full years. Yet while there are still many optimizations and revisions to be done, I was thrilled to find -- with completely new nanoparticles that may one day mean future trials will use particles with the initials "RK-1" -- thatcyclophosphamide did indeed increase nanoparticle delivery to the tumor in a statistically significant way.

A secondary, unexpected research project was living alone in Baltimore, a new city to me, surrounded by people much older than I. Even with moving frequently between hotels, AirBnB's, and students' apartments, I strangely reveled in the freedom I had to enjoy my surroundings and form new friendships with graduate school students from the lab. We explored The Inner Harbor at night, attended a concert together one weekend, and even got to watch the Orioles lose (to nobody's surprise). Ironically, it's through these new friendships I discovered something unexpected: what I truly love is sharing research. Whether in a presentation or in a casual conversation, making others interested in science is perhaps more exciting to me than the research itself. This solidified a new pursuit to angle my love for writing towards illuminating science in ways people can understand, adding value to a society that can certainly benefit from more scientific literacy.

It seems fitting that my goals are still transforming: in Scarry's book, there is not just one goldbug, there is one on every page. With each new experience, I'm learning that it isn't the goldbug itself, but rather the act of searching for the goldbugs that will encourage, shape, and refine my ever-evolving passions. Regardless of the goldbug I seek -- I know my pickle truck has just begun its journey.

Renner takes a somewhat different approach than Stephen, but their essay is just as detailed and engaging. Let's go through some of the strengths of this essay.

One Clear Governing Metaphor

This essay is ultimately about two things: Renner’s dreams and future career goals, and Renner’s philosophy on goal-setting and achieving one’s dreams.

But instead of listing off all the amazing things they’ve done to pursue their dream of working in nanomedicine, Renner tells a powerful, unique story instead. To set up the narrative, Renner opens the essay by connecting their experiences with goal-setting and dream-chasing all the way back to a memorable childhood experience:

This lighthearted–but relevant!--story about the moment when Renner first developed a passion for a specific career (“finding the goldbug”) provides an anchor point for the rest of the essay. As Renner pivots to describing their current dreams and goals–working in nanomedicine–the metaphor of “finding the goldbug” is reflected in Renner’s experiments, rejections, and new discoveries.

Though Renner tells multiple stories about their quest to “find the goldbug,” or, in other words, pursue their passion, each story is connected by a unifying theme; namely, that as we search and grow over time, our goals will transform…and that’s okay! By the end of the essay, Renner uses the metaphor of “finding the goldbug” to reiterate the relevance of the opening story:

While the earlier parts of the essay convey Renner’s core message by showing, the final, concluding paragraph sums up Renner’s insights by telling. By briefly and clearly stating the relevance of the goldbug metaphor to their own philosophy on goals and dreams, Renner demonstrates their creativity, insight, and eagerness to grow and evolve as the journey continues into college.

An Engaging, Individual Voice

This essay uses many techniques that make Renner sound genuine and make the reader feel like we already know them.

Technique #1: humor. Notice Renner's gentle and relaxed humor that lightly mocks their younger self's grand ambitions (this is different from the more sarcastic kind of humor used by Stephen in the first essay—you could never mistake one writer for the other).

My first dream job was to be a pickle truck driver.

I would imagine the wonderful life I would have: being a pig driving a giant pickle truck across the country, chasing and finding goldbug. I then moved on to wanting to be a Lego Master. Then an architect. Then a surgeon.

Renner gives a great example of how to use humor to your advantage in college essays. You don’t want to come off as too self-deprecating or sarcastic, but telling a lightheartedly humorous story about your younger self that also showcases how you’ve grown and changed over time can set the right tone for your entire essay.

Technique #2: intentional, eye-catching structure. The second technique is the way Renner uses a unique structure to bolster the tone and themes of their essay . The structure of your essay can have a major impact on how your ideas come across…so it’s important to give it just as much thought as the content of your essay!

For instance, Renner does a great job of using one-line paragraphs to create dramatic emphasis and to make clear transitions from one phase of the story to the next:

Suddenly the destination of my pickle car was clear.

Not only does the one-liner above signal that Renner is moving into a new phase of the narrative (their nanoparticle research experiences), it also tells the reader that this is a big moment in Renner’s story. It’s clear that Renner made a major discovery that changed the course of their goal pursuit and dream-chasing. Through structure, Renner conveys excitement and entices the reader to keep pushing forward to the next part of the story.

Technique #3: playing with syntax. The third technique is to use sentences of varying length, syntax, and structure. Most of the essay's written in standard English and uses grammatically correct sentences. However, at key moments, Renner emphasizes that the reader needs to sit up and pay attention by switching to short, colloquial, differently punctuated, and sometimes fragmented sentences.

Even with moving frequently between hotels, AirBnB's, and students' apartments, I strangely reveled in the freedom I had to enjoy my surroundings and form new friendships with graduate school students from the lab. We explored The Inner Harbor at night, attended a concert together one weekend, and even got to watch the Orioles lose (to nobody's surprise). Ironically, it's through these new friendships I discovered something unexpected: what I truly love is sharing research.

In the examples above, Renner switches adeptly between long, flowing sentences and quippy, telegraphic ones. At the same time, Renner uses these different sentence lengths intentionally. As they describe their experiences in new places, they use longer sentences to immerse the reader in the sights, smells, and sounds of those experiences. And when it’s time to get a big, key idea across, Renner switches to a short, punchy sentence to stop the reader in their tracks.

The varying syntax and sentence lengths pull the reader into the narrative and set up crucial “aha” moments when it’s most important…which is a surefire way to make any college essay stand out.

Renner's essay is very strong, but there are still a few little things that could be improved.

Connecting the research experiences to the theme of “finding the goldbug.” The essay begins and ends with Renner’s connection to the idea of “finding the goldbug.” And while this metaphor is deftly tied into the essay’s intro and conclusion, it isn’t entirely clear what Renner’s big findings were during the research experiences that are described in the middle of the essay. It would be great to add a sentence or two stating what Renner’s big takeaways (or “goldbugs”) were from these experiences, which add more cohesion to the essay as a whole.

Give more details about discovering the world of nanomedicine. It makes sense that Renner wants to get into the details of their big research experiences as quickly as possible. After all, these are the details that show Renner’s dedication to nanomedicine! But a smoother transition from the opening pickle car/goldbug story to Renner’s “real goldbug” of nanoparticles would help the reader understand why nanoparticles became Renner’s goldbug. Finding out why Renner is so motivated to study nanomedicine–and perhaps what put them on to this field of study–would help readers fully understand why Renner chose this path in the first place.

4 Essential Tips for Writing Your Own Essay

How can you use this discussion to better your own college essay? Here are some suggestions for ways to use this resource effectively.

#1: Get Help From the Experts

Getting your college applications together takes a lot of work and can be pretty intimidatin g. Essays are even more important than ever now that admissions processes are changing and schools are going test-optional and removing diversity standards thanks to new Supreme Court rulings . If you want certified expert help that really makes a difference, get started with PrepScholar’s Essay Editing and Coaching program. Our program can help you put together an incredible essay from idea to completion so that your application stands out from the crowd. We've helped students get into the best colleges in the United States, including Harvard, Stanford, and Yale. If you're ready to take the next step and boost your odds of getting into your dream school, connect with our experts today .

#2: Read Other Essays to Get Ideas for Your Own

As you go through the essays we've compiled for you above, ask yourself the following questions:

- Can you explain to yourself (or someone else!) why the opening sentence works well?

- Look for the essay's detailed personal anecdote. What senses is the author describing? Can you easily picture the scene in your mind's eye?

- Find the place where this anecdote bridges into a larger insight about the author. How does the essay connect the two? How does the anecdote work as an example of the author's characteristic, trait, or skill?

- Check out the essay's tone. If it's funny, can you find the places where the humor comes from? If it's sad and moving, can you find the imagery and description of feelings that make you moved? If it's serious, can you see how word choice adds to this tone?

Make a note whenever you find an essay or part of an essay that you think was particularly well-written, and think about what you like about it . Is it funny? Does it help you really get to know the writer? Does it show what makes the writer unique? Once you have your list, keep it next to you while writing your essay to remind yourself to try and use those same techniques in your own essay.

#3: Find Your "A-Ha!" Moment

All of these essays rely on connecting with the reader through a heartfelt, highly descriptive scene from the author's life. It can either be very dramatic (did you survive a plane crash?) or it can be completely mundane (did you finally beat your dad at Scrabble?). Either way, it should be personal and revealing about you, your personality, and the way you are now that you are entering the adult world.

Check out essays by authors like John Jeremiah Sullivan , Leslie Jamison , Hanif Abdurraqib , and Esmé Weijun Wang to get more examples of how to craft a compelling personal narrative.

#4: Start Early, Revise Often

Let me level with you: the best writing isn't writing at all. It's rewriting. And in order to have time to rewrite, you have to start way before the application deadline. My advice is to write your first draft at least two months before your applications are due.

Let it sit for a few days untouched. Then come back to it with fresh eyes and think critically about what you've written. What's extra? What's missing? What is in the wrong place? What doesn't make sense? Don't be afraid to take it apart and rearrange sections. Do this several times over, and your essay will be much better for it!

For more editing tips, check out a style guide like Dreyer's English or Eats, Shoots & Leaves .

What's Next?

Still not sure which colleges you want to apply to? Our experts will show you how to make a college list that will help you choose a college that's right for you.

Interested in learning more about college essays? Check out our detailed breakdown of exactly how personal statements work in an application , some suggestions on what to avoid when writing your essay , and our guide to writing about your extracurricular activities .

Working on the rest of your application? Read what admissions officers wish applicants knew before applying .

The recommendations in this post are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Anna scored in the 99th percentile on her SATs in high school, and went on to major in English at Princeton and to get her doctorate in English Literature at Columbia. She is passionate about improving student access to higher education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- Computers & Technology

- Computer Science

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -20% $31.99 $ 31 . 99 FREE delivery Tuesday, June 4 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $14.86 $ 14 . 86 FREE delivery Monday, June 3 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Daily Deals 504

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Design of Design, The: Essays from a Computer Scientist 1st Edition

Purchase options and add-ons.

The author tracks the evolution of the design process, treats collaborative and distributed design, and illuminates what makes a truly great designer. He examines the nuts and bolts of design processes, including budget constraints of many kinds, aesthetics, design empiricism, and tools, and grounds this discussion in his own real-world examples—case studies ranging from home construction to IBM's Operating System/360. Throughout, Brooks reveals keys to success that every designer, design project manager, and design researcher should know.

- ISBN-10 0201362988

- ISBN-13 978-0201362985

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Addison-Wesley Professional

- Publication date March 22, 2010

- Language English

- Dimensions 1.1 x 6.1 x 9.1 inches

- Print length 448 pages

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

From the back cover.

Making Sense of Design

Effective design is at the heart of everything from software development to engineering to architecture. But what do we really know about the design process? What leads to effective, elegant designs? The Design of Design addresses these questions.

These new essays by Fred Brooks contain extraordinary insights for designers in every discipline. Brooks pinpoints constants inherent in all design projects and uncovers processes and patterns likely to lead to excellence. Drawing on conversations with dozens of exceptional designers, as well as his own experiences in several design domains, Brooks observes that bold design decisions lead to better outcomes.

The author tracks the evolution of the design process, treats collaborative and distributed design, and illuminates what makes a truly great designer. He examines the nuts and bolts of design processes, including budget constraints of many kinds, aesthetics, design empiricism, and tools, and grounds this discussion in his own real-world examples―case studies ranging from home construction to IBM's Operating System/360. Throughout, Brooks reveals keys to success that every designer, design project manager, and design researcher should know.

About the Author

Frederick P. Brooks, Jr. , is Kenan Professor of Computer Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the recipient of the National Medal of Technology, for his work on IBM’s Operating System/360, and the A. M. Turing Award, for his “landmark contributions to computer architecture, operating systems, and software engineering.” He is the author of the best-selling book The Mythical Man-Month, Anniversary Edition (Addison-Wesley, 1995).

Product details

- Publisher : Addison-Wesley Professional; 1st edition (March 22, 2010)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 448 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0201362988

- ISBN-13 : 978-0201362985

- Item Weight : 1.34 pounds

- Dimensions : 1.1 x 6.1 x 9.1 inches

- #204 in Computer Systems Analysis & Design (Books)

- #1,327 in Software Design, Testing & Engineering (Books)

- #1,524 in Computer Software (Books)

About the author

Frederick p. brooks, jr..

Frederick P. Brooks, Jr., is Kenan Professor of Computer Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He was an architect of the IBM Stretch and Harvest computers. He was Corporate Project Manager for the System/360, including development of the System/360 computer family hardware and the decision to switch computer byte size from 6 to 8 bits. He then managed the initial development of the Operating System/360 software suite: operating system, 16 compilers, communications, and utilities.

He founded the UNC Department of Computer Science in 1964 and chaired it for 20 years. His research there has been in computer architecture, software engineering, and interactive 3-D computer graphics (protein visualization graphics and "virtual reality"). His best-known books are The Mythical Man-Month (1975, 1995); Computer Architecture: Concepts and Evolution (with G.A. Blaauw, 1997); and The Design of Design (2010).

Dr. Brooks has received the National Medal of Technology, the A.M. Turing award of the ACM, the Bower Award and Prize of the Franklin Institute, the John von Neumann Medal of the IEEE, and others. He is a member of the U.S. National Academies of Engineering and of Science, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Royal Academy of Engineering (U.K.) and of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

He became a Christian at age 31 and has taught an adult Sunday school class for 35 years. He chaired the Executive Committee for the 1973 Research Triangle Billy Graham Crusade. He and Mrs. Nancy Greenwood Brooks are faculty advisors to a graduate student chapter of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. They have three children and nine grandchildren.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, design – the visual language that shapes our world.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Design refers to much more than how something looks or works: Design is a powerful tool of communication that empowers writers, graphic designers, and product developers to reach their target audience at a viscera, visual level. Good design makes information easier to understand, more engaging, and more memorable. It creates emotional connections, influences perceptions, and shapes decisions. If your design is unappealing or confusing, you've lost your chance at engaging your audience in the 8 seconds they're willing to give attention to your work. The essay below defines design based on research and scholarship, explores the importance of design in our contemporary information ecology, and serves as an introduction to design resources @ Writing Commons.

What is Design?

Design , most conventionally, refers to how something looks or works . For instance, by any measure, the Apple iPhone is well designed: the colors it displays are brilliant; it fits in your pocket; it’s easy to use as a camera, a recording device, or phone; and it provides easy access to friends, music, and the internet.

Yet, design may refer to more than whether or not a text or product looks good or accomplishes its aims . For instance, d esign may also be defined as

- a social construct

- a form of visual language , a mode of human communication

- a signifier of identity and community

- a subject of study, an academic discipline, a catechism regarding usr, an interpretative framework , based on principles of design .

Related Concepts: Composition ; Composing Processes ; Design Thinking ; Gestalt ; Information Architecture ; Information Design ; Semiotics

Definitions of Design

1. design refers to how a text, application, or product looks or works.

“ Design is a fun word. Some people think design means how it looks. But of course, if you dig deeper, it’s really how it works.” Steve Jobs

Design refers to the aesthetics and functionality of a text , application, or product—concepts often encapsulated under the banner of “look and feel.”

Aesthetics (Look):

This dimension of design involves the visual, tactile, and sometimes auditory elements of a product or system. It encompasses attributes such as color , shape , texture , typography , and layout . In terms of a digital application, for example, the choice of icons , the color scheme , typography , and the overall user interface (UI) fall under aesthetic considerations. These elements contribute to the overall visual appeal and user experience.

Functionality (Works):

This refers to the operational aspect of a design. It involves how well the product, application, or system serves its intended purpose. The functionality of a design is often evaluated based on its efficiency, effectiveness, and ease of use. In the case of a digital application, it would include aspects like navigation flow, load times, responsiveness, and overall usability.

In essence, the balance between aesthetics and functionality is key in design. A design that excels in both dimensions creates an engaging, user-friendly, and effective product or system. This outlook is crucial in fields like product design, web design, graphic design, and user experience (UX) design, among others.

For writers, d esign largely concerns

- the use of data visualizations and other elements of design and visual language

- the page design & scannability of a text .

2. Design is a Social, Historical Construct

Design, a social and historical construct, stands at the intersection of art, culture, history, and technology. It serves as a mirror to our collective intellect, reflecting our beliefs, history, and advancements. Each culture, each epoch has its unique interpretation and manifestation of design, thus weaving a rich, multifaceted tapestry of human creativity and evolution.

Art and Culture

Art and cultural norms seep deep into the core of design, infusing it with distinctive colors and patterns. Take, for example, the traditional Mexican design. Its bright geometric patterns symbolize the nation’s vibrant culture and rich historical narratives. It’s a testament to the cultural sensibilities that pervade design.

But look closer, and you see a paradox: despite periods of hardship and scarcity, Mexican people devoted resources to create opulent gold temples and intricate religious artifacts for the Catholic Church. This underscores design’s role as a reflection of cultural priorities and beliefs, sometimes extending beyond immediate practical needs.

Design reflects the dialogues , epistemologies , and circumstances of particular cultures and specific time periods. Consider, e.g., in the heart of the desert, the ancient Egyptians designed pyramids and temples that continue to astound us millennia later. These structures, built with an extraordinary precision that baffles modern engineers, stand as a testament to the design sensibilities of a civilization that existed over 4,000 years ago. Their hieroglyphic scripts and symbolic art formed a design language that communicated spiritual beliefs and pharaonic authority.

Fast forward to the Victorian era, characterized by its industrial growth and prosperity, and you see a markedly different design narrative. The Victorian designs embraced opulence and ornamentation, with an emphasis on detailing and a penchant for grandeur. This was reflected in their architecture, fashion, and even their typography.

In stark contrast, the 21st century has been marked by a shift towards minimalism in design. Embodying the mantra ‘less is more,’ modern design trends advocate simplicity and functionality. From the sleek lines of contemporary architecture to the user-friendly design of digital interfaces, the present-day design ethos emphasizes usability and clarity .

3. Design is a Form of Visual Language

Design refers to much more than how something looks or works. Design, at its core, is a sophisticated form of visual language . More than just aesthetically pleasing arrangements of elements, it holds the power to communicate, provoke thought, and stir emotions.

This communication occurs at a fundamental, prelinguistic level–as a form of felt sense . While conventional languages use words and syntax to convey meaning, design communicates through a rich vocabulary of visual elements: lines, shapes, colors, spaces, and typography. These elements are arranged using principles like alignment, balance, and contrast to create a cohesive visual message.

When the audience interacts with a design, they are not just passively observing. They are actively ‘reading’ these visual elements and interpreting them. This interpretation often happens instinctively, tapping into our innate human capacity for visual perception. We are, as a species, highly attuned to visual information. Our brains are wired to recognize patterns, discern contrasts, and respond to visual stimuli.

Audiences read the design of a text or product just as they read words and sentences . Yet rather than words or sentences , they read design elements : They trace the line on the page or screen. They note the images, colors , shapes , contrast , spaces , and typography of the copy . They consider the alignment , balance , proximity , repetition of symbols. And then they interpret these symbolic elements to mean something. Their interpretation may be experienced as a form of felt sense of gestalt . In other words, they engage in acts of communication .

4. Design May Function as a Signifier of Identity and Community

In business, companies spend small fortunes defining their brand. They aim to distinguish their products and services. Thus, it’s fairly commonplace for business and nonprofit organizations to have style guidelines.

Typically style guidelines

- call for standard written English

- call for a professional writing style

- call for a particular citation style

- define logo, color, and photo-usage guidelines.

5. Design May Refer to a Curriculum, a Catechism, a Subject of Study

Design is an extraordinarily broad field, a convergence point where disciplines such as arts, engineering, sciences, and humanities intersect and engage in a dynamic discourse . Its interdisciplinary nature stems from the fact that design problems often require diverse perspectives and multi-faceted solutions. Hence, design isn’t just about aesthetics or usability; it’s about crafting solutions that reconcile functionality, sustainability, social impact, and user experience.

In academic settings, design manifests as a robust field of study, encompassing a broad spectrum of topics, including

- accommodation s(how designs cater to different user needs)

- aesthetics (the principles that guide visual harmony and appeal)

- information architecture (how information is organized and structured in a design),

- information design (how information is presented)

- usability (how user-friendly a design is).

Communities of Practice: Shaping the Design Landscape

Alongside academia, communities of practice contribute significantly to the evolution of design as a field. These communities, composed of practitioners and scholars, engage in rigorous scholarship and empirical research. Their primary objective is to enhance clarity in communication and improve design outcomes.

These communities continually shape the design landscape through the development of conventions and best practices. They respond dynamically to technological advancements and societal shifts, adapting design practices to better fit new paradigms. This iterative process of exploration, adaptation, and refinement is what keeps design relevant and effective in a rapidly changing world.

Through this ongoing conversation of humankind and the ever-evolving technological landscape, design continues to evolve, offering innovative solutions to both old and new problems. This is a testament to design’s versatile nature and its inherent capacity to adapt, innovate, and inspire.

Related Concepts

Writers, designers, and usability experts design texts and products by composing with design elements (e.g., Color – Color Theory ; Line ; Shape ; Space ; Typography ). Additionally, they consult their knowledge of design principles — (e.g., alignment ; balance ; color ; Contrast ; Emphasis ; Gestalt, Gestalt Theory ; Proximity ; Repetition ) in order to inform their compositions.

Recommended Books on Design

- Cooper, A., Reimann, R., Cronin, D., & Noessel, C. (2014). About face: The essentials of interaction design (4th ed.). Wiley.

- Krug, S. (2013). Don’t make me think, revisited: A common sense approach to web usability (3rd ed.). New Riders.

- Norman, D. (2013). The design of everyday things: Revised and expanded edition . Basic Books.

- Williams, R. (2014). Non-designer’s design book (4th ed.). Peachpit Press.

Why does design matter?

In 2023, we’re living in a world where attention spans are shrinking, digital content is proliferating, and consumer expectations are escalating. The average person spent around 6 hours and 42 minutes online every day, and this time is scattered across various platforms – social media, news sites, video streaming, online shopping, and much more. The explosion of digital content means people are inundated with information, choices, and distractions, making it harder than ever to stand out. In this context, excellent design isn’t just nice to have – it’s a necessary tool for survival. It’s a way to respect your audience’s time, to reward their attention, and to rise above the noise.

Related Articles:

Data Visualization - Information Visualization - The Art of Visualizing Meaning For Better Decision-Making

Design Principles - The Big Design Principles You Need to Know to Create Compelling Messages

Elements of Art - How to Leverage the Power of Art to Make Visually Compelling Documents

Elements of design – master the fundamentals of visual composition.

Page Design - How to Design Messages for Maximum Impact

Universal design principles - how to design for everyone.

Usability - How to Research & Improve Usability

Visual representation, suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Review research and theory on the information visualization. Unlock the power of data visualization to make complex data accessible and engaging. Learn the art and science of transforming numbers into...

- Joseph M. Moxley

Principles of design refer to the discourse conventions, artistic traditions, and theories that inform the design of messages, products, and services. P.A.R.C. refers to the four primary design principles (proximity,...

The Elements of Art (also known as The Elements of Design) refers to color, form, line, shape, space, texture, and value. Working as a gestalt that communicates with audiences at...

Page design refers to the strategic placement of information on a page or digital screen: Good page design can help you hook your readers’ curiosity and improve readability. Good page...

Universal design focuses on all potential users’ needs, abilities, and limitations. Rather than target a narrow user/customer segment, universal design values inclusivity: designers practicing universal design aim to make their...

Usability refers to the ease with which audiences can accurately interpret your message, understand your purpose, and navigate your information architecture. Whether you’re writing an essay, a research paper, or...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

The Essay: History and Definition

Attempts at Defining Slippery Literary Form

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

"One damned thing after another" is how Aldous Huxley described the essay: "a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything."

As definitions go, Huxley's is no more or less exact than Francis Bacon's "dispersed meditations," Samuel Johnson's "loose sally of the mind" or Edward Hoagland's "greased pig."

Since Montaigne adopted the term "essay" in the 16th century to describe his "attempts" at self-portrayal in prose , this slippery form has resisted any sort of precise, universal definition. But that won't an attempt to define the term in this brief article.

In the broadest sense, the term "essay" can refer to just about any short piece of nonfiction -- an editorial, feature story, critical study, even an excerpt from a book. However, literary definitions of a genre are usually a bit fussier.