Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: The Speech Communication Process

Speech Anxiety

What is it.

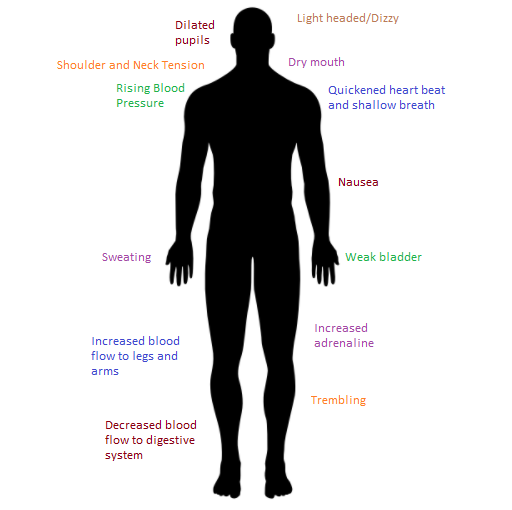

Speech anxiety is best defined as the nervousness that a speaker feels before and/or during a presentation. Sweating palms, a shaky voice, a dry throat, difficulty breathing, and even memory loss are all common symptoms of anxiety. The symptoms you, as an individual, will feel are hard to predict. But it helps if you remember that nearly every speaker has experienced some degree of speech anxiety. Even professional speakers occasionally feel a small amount of apprehension at times. Anxiety levels vary. Some speakers will report little to no anxiety while speaking; others will confess that they are petrified at the thought of speaking in public. Jerry Seinfeld used to joke that “at a funeral, the average person would rather be in the casket than giving the eulogy. ” Now that is fear!

Why Anxiety and Public Speaking?

Scholars at the University of Wisconsin-Stout (“Public Speaking Anxiety,” 2015) explain that anxiety in public speaking can result from one of several misperceptions:

• “all or nothing” thinking—a mindset that if your speech falls short of “perfection” (an unrealistic standard), then you are a failure as a public speaker;

• overgeneralization—believing that a single event (such as failing at a task) is a universal or “always” event; and

• fortune telling—the tendency to anticipate that things will turn out badly, no matter how much practice or rehearsal is done.

Likewise, many new college students operate under the false belief that intelligence and skill are “fixed.” In their minds, a person is either smart or skilled in something, or they are not. Some students apply this false belief to math and science subjects, saying things like “I’m just no good at math and I never will be,” or even worse, “I guess I am just not smart enough to be in college.” As you can tell, these beliefs can sabotage someone’s college career. Also unfortunately, the same kind of false beliefs are applied to public speaking, and people conclude that because public speaking is hard, they are just not “naturally good” at it and have no inborn skill. They give up on improving and avoid public speaking at all costs.

There is more to Dr. Dweck’s research. We would recommend her book Mindset . Many students enter a public speaking class thinking “I’m just no good at this and never will be,” just like some students feel about college algebra or science. Dr. Dweck and other learning psychologists show that learning a new skill might be hard work, but the difficulty is not a sign that learning is impossible. Modern research by Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck (2007) and others shows that intelligence and related skills are “malleable,” meaning that they are open to change and growth. Understanding and accepting that your intelligence and skill in different areas is not fixed or “stuck,” but open to growth, will have a significant influence on your success in life. It will also help you see that just because learning a subject or task is hard does not mean you are not or cannot be good at it. Obstacles and barriers that make learning hard are opportunities for growth, not “getting off places.”

Along with the wrong way of thinking about one’s learning and growth, two other fears contribute to anxiety in public speaking. The first is fear of failure. This fear can result from several sources: real or perceived bad experiences involving public speaking in the past, lack of preparation, lack of knowledge about public speaking, not knowing the context, and uncertainty about one’s task as a public speaker (such as being thrown into a situation at the last minute).

It is not the goal of this book to belittle that fear. It is real and justified to some extent because you might lack understanding of the public speaking task or lack good speaking experiences upon which to build. One of the goals and fringe benefits of this course is that you are not just going to learn about public speaking, but you are going to do it—at least four or five times—with a real audience. You will overcome some of your fears and feel that you have accomplished something of personal benefit.

The second fear is fear of rejection of one’s self or one’s ideas. This one is more serious in some respects. You may feel rejection because of fear of failure, or you may feel that the audience will reject your ideas, or worse, you as a person. Knowing how to approach the public speaking task and explain your ideas can help. However, you should ask yourself deep and probing questions as to why you believe that your audience will reject you because this fear is rooted in a belief. You should ask yourself what possibly false belief is causing your anxiety.

One of the core attitudes an effective and ethical public speaker must have is respect for and empathy with the audience. Your audience in this class is your peers who want to learn and want to get through the class success- fully (just like you do). Your audience also includes your instructor who wants to see you succeed in the course as well. Believe me, public speaking teachers get a lot of pleasure from hearing successful student speeches!

Your audience wants you to succeed if for no other reason than a good speech is much easier and pleasant to listen to than a poor one. Again, gaining practice in this class with a real, live audience can help you work through the roots of your fear of rejection.

Beyond dealing with the root fears that may cause you to have a “fright or flight” response when it comes to public speaking, there are some practical answers to dealing with fears about public speaking. Of course, fear responses can be reduced if you know how public speaking works, as you will see throughout this textbook. But there are some other strategies, and most of them have to do with preparation.

How Do I Overcome My Fear?

There are many reasons why a speaker might feel anxious, but there are several steps you can take to reduce your anxiety. First, remember that everyone has experienced some level of anxiety during a presentation. Knowing that you are not the only one feeling nervous should help a bit. Keep in mind that most listeners won’t even be aware of your anxiety. They often don’t see what you thought was glaringly obvious; they’re busy preparing themselves for their turn up front. It is perfectly normal to feel nervous when you find yourself in an unfamiliar setting or situation. You probably felt nervous the first time you had to shoot a foul shot in front of a large crowd of basketball fans. Or you might recall the anxiety you felt during your first piano recital as a child, or that first job interview. Think of this nervous feeling as your body readying itself for an important activity.

Also, you might feel anxious if you have not adequately prepared for the presentation. Preparing and practicing your presentation are two of the surest ways to minimize nervousness. No one wants to feel embarrassed in public, but knowing that you have done everything possible to ensure success should help you feel more confident. Do your research and organize your ideas logically. Then practice several times. Try to find someone to listen as you practice -your family, your friends, your roommate -and listen to their feedback. Even if they don’t know your topic, they know you. They may even be able to point out some areas in your presentation that still need improvement. The more you prepare and practice, the more successful your presentation will likely be.

Finally, be optimistic and focus on the positives. Use positive self-talk as you prepare. Don’t tell yourself that you’ll perform horribly or that you can’t do it. Have you ever heard of a self-fulfilling prophecy? What you expect to happen may be exactly what does happen. So tell yourself that you’re well prepared and that you will improve every time you speak. Remind yourself that you are calm and in control of the situation and be sure to take a deep breath whenever necessary. Imagine yourself speaking clearly and effortlessly. Find a couple of friendly faces in the crowd and focus on them. If they’re sending positive energy your way, grab it!

Addressing Public Speaking Anxiety

Mental Preparation

If your neighbor’s house were on fire, getting to the phone to call the fire department would be your main concern. You would want to get the ad- dress right and express the urgency. That is admittedly an extreme exam ple, but the point is about focus. To mentally prepare, you want to put your focus where it belongs, on the audience and the message. Mindfulness and full attention to the task are vital to successful public speaking. If you are concerned about a big exam or something personal going on in your life, your mind will be divided, and that division will add to your stress.

The main questions to ask yourself are “Why am I so anxiety-ridden about giving a presentation?” and “What is the worst that can happen?” For example, you probably won’t know most of your classmates at the beginning of the course, adding to your anxiety. By midterm, you should be developing relationships with them and be able to find friendly faces in the audience. However, very often we make situations far worse in our minds than they actually are, and we can lose perspective. One of the authors tells her students, “Some of you have been through childbirth and even through military service . That is much worse than public speaking!” Your instructor will probably try to help you get to know your classmates and minimize the “unknowns” that can cause you worry.

Physical preparation

The first step in physical preparation is adequate sleep and rest. You might be thinking such a thing is impossible in college, where sleep deprivation and late nights come with the territory. However, research shows the extreme effects a lifestyle of limited sleep can have, far beyond yawning or dozing off in class (Mitru, Millrood, & Mateika, 2002; Walker, 2017). As far as public speaking is concerned, your energy level and ability to be alert and aware during the speech will be affected by lack of sleep.

Secondly, you would be better off to eat something that is protein-based rather than processed sugar-based before speaking. In other words, cheese or peanut butter on whole grain toast, Greek yogurt, or eggs for breakfast rather than a donut and soft drink. Some traditionalists also discourage the drinking of milk because it is believed to stimulate mucus production, but this has not been scientifically proven (Lai & Kardos, 2013).

A third suggestion is to wear clothes that you know you look good in and are comfortable but also meet the context’s requirements (that is, your instructor may have a dress code for speech days). Especially, wear comfort- able shoes that give you a firm base for your posture. Flip- flops and really high heels may not fit these categories.

A final suggestion for physical preparation is to utilize some stretching or relaxation techniques that will loosen your limbs or throat. Essentially, your emotions want you to run away, but the social situation says you must stay, so all that energy for running must go somewhere. The energy might go to your legs, hands, stomach, sweat glands, or skin, with undesirable physical consequences. Tightening and stretching your hands, arms, legs, and throat (through intentional, wide yawns) for a few seconds before speaking can help release some of the tension. Your instructor may be able to help you with these exercises, or you can find some on the Internet.

Contextual preparation

The more you can know about the venue where you will be speaking, the better. For this class, of course, it will be your classroom, but for other situations where you might experience “communication apprehension,” you should check out the space beforehand or get as much information as possible. For example, if you were required to give a short talk for a job interview, you would want to know what the room will be like, if there is equipment for projection, how large the audience will be, and the seating arrangements. If possible, you will want to practice your presentation in a room that is similar to the actual space where you will deliver it.

The best advice for contextual preparation is to be on time, even early. If you have to rush in at the last minute, as so many students do, you will not be mindful, focused, or calm for the speech. Even more, if you are early, you can make sure equipment is working, and can converse with the audience as they enter. Professional speakers often do this to relax themselves, build credibility, and gain knowledge to adapt their presentations to the audience. Even if you don’t want to “schmooze” beforehand, being on time will help you create a good first impression and thus enhance your credibility before the actual speech.

Speech preparation

Procrastination, like lack of sleep, seems to just be part of the college life. Sometimes we feel that we just don’t get the best ideas until the last minute. Writing that essay for literature class at 3:00 a.m. just may work for you. However, when it comes to public speaking, there are some definite reasons you would not want to do that. First, of course, if you are finishing up your outline at 3:00 a.m. and have a 9:00 speech, you are going to be tired and unable to focus. Second, your instructor may require you to turn in your outline several days ahead of the speech date. However, the main reason is that public speaking requires active, oral, repeated practice before the actual delivery.

You do not want the first time that you say the words to be when you are in front of your audience. Practicing is the only way that you will feel confident, fluent, and in control of the words you speak. Practicing (and timing yourself) repeatedly is also the only way that you will be assured that your speech meets the assignment’s time limits, and speaking within the expected time limits is a fundamental rule of public speaking. You may think your speech is five minutes long but it may end up being ten minutes the first time you practice it—or only two minutes!

Your practicing should be out loud, standing up, with shoes on, with someone to listen, if possible (other than your dog or cat), and with your visual aids. If you can record yourself and watch it, that is even better. If you do record yourself, make sure you record yourself from the feet up- or at least the hips up—so you can see your body language. The need for oral practice will be emphasized over and over in this book and probably by your instructor. As you progress as a speaker, you will always need to practice but perhaps not to the extent you do as a novice speaker.

As hard as it is to believe, YOU NEVER LOOK AS NERVOUS AS YOU FEEL.

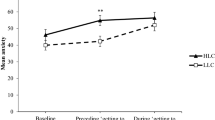

You may feel that your anxiety is at level seventeen on a scale of one to ten, but the audience does not perceive it the same way. They may perceive it at a three or four or even less. That’s not to say they won’t see any signs of your anxiety and that you don’t want to learn to control it, only that what you are feeling inside is not as visible as you might think. This principle relates back to focus. If you know you don’t look as nervous as you feel, you can focus and be mindful of the message and audience rather than your own emotions.

Also, you will probably find that your anxiety decreases throughout the class (Finn, Sawyer, & Schrodt, 2009). In her Ted Talk video , Harvard Business School social psychologist Amy Cuddy discusses nonverbal communication and suggests that instead of “faking it until you make it,” that you can, and should, “fake it until you become it.” She shares research that shows how our behavior affects our mindsets, not just the other way around. Therefore, the act of giving the speech and “getting through it” will help you gain confidence. Interestingly, Dr. Cuddy directs listeners to strike a “power pose” of strong posture, feet apart, and hands on hips or stretched over head to enhance confidence.

Final Note: If you are an audience member, you can help the speaker with his/her anxiety, at least a little bit. Mainly, be an engaged listener from beginning to end. You can imagine that a speaker is going to be more nervous if the audience looks bored from the start. A speaker with less anxiety is going to do a better job and be more interesting. Of course, do not walk into class during your classmates’ speeches, or get up and leave. In addition to being rude, it pulls their minds away from their message and distracts the audience. Your instructor will probably have a policy on this behavior, too, as well as a dress code and other expectations on speech days. There are good reasons for these policies, so respect them.

Fundamentals of Public Speaking Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Understanding And Overcoming Public Speaking Anxiety

Most of us might experience what is commonly known as stage fright or speaking anxiety, nervousness and stress experienced around speaking situations in front of audience members. Even for experienced speakers, this can be a normal response to pressurized situations in which we are the focus of attention—such as we might encounter in front of an audience. For some people, though, the fear of public speaking and nervous energy can be much more severe, and can be a sign of an anxiety disorder.

Speaking anxiety is considered by many to be a common but challenging form of social anxiety disorder that can produce serious symptoms, and can possibly impact an individual’s social life, career, and emotional and physical well-being.

In this article, we’ll explore what speaking anxiety is, common symptoms of it, and outline several tips for managing it.

Identifying public speaking anxiety: Definition, causes, and symptoms

According to the American Psychological Association, public speaking anxiety is the “fear of giving a speech or presentation in public because of the expectation of being negatively evaluated or humiliated by others”.

Often associated with a lack of self-confidence, the disorder is generally marked by severe worry and nervousness, in addition to several physical symptoms. The fear can be felt by many, whether they are in the middle of a speech or whether they are planning to speak at a future point. They may also generally fear contact with others in informal settings.

Public speaking anxiety can be a common condition, with an with an estimated prevalence of 15-30% among the general population.

Public speaking anxiety is considered by many to be a form of social anxiety disorder (SAD). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-V) includes a performance specifier that allows a SAD diagnosis to relate specifically to anxiety surrounding public speaking or performing. For some extreme forms of this mental health condition, a medical professional may prescribe medication that can help overcome severe symptoms—although for most people this won’t be necessary.

The symptoms of performance-type social anxiety can include:

- Worry or fear surrounding public speaking opportunities or performing, even in front of friendly faces

- Avoiding situations in which public speaking or performing may be necessary

- Shaky voice, especially when one has to speak in public

- Stomach pain or gastrointestinal discomfort

- Rapid breathing

There are several strategies for addressing the symptoms of this and feeling more confident with your oratory skills, whether you need to use them at work, in formal social settings or simply in front of friends.

The following are several strategies you can employ to address the fear of public speaking and manage your fear when it arises.

While the primary concern for those who experience speaking anxiety might typically be the fear of judgment or embarrassment when speaking publicly, there can be other causes contributing to distress. To figure out how to address this, it can help to understand potential contributing factors—as well as how others may be dealing with it on their own.

First, it can be helpful to determine where the fear came from in the first place. Here are some common sources of public speaking anxiety :

- Negative past experiences with public speaking

- Lack of preparedness

- Low self-esteem (this possible cause can cause feelings of overwhelm if one has to give a speech)

- Inexperience with public speaking

- Unfamiliar subject matter

- Newness of environment

- Fear of rejection (such as from an audience)

Practice deep breathing

Public speaking anxiety might often be accompanied by feelings of stress, and also often affects physical factors such as increased speed of heart rate, tension, and rapid breathing. If you’re dealing with speaking anxiety and want to calm your nerves before a public speaking event, it can be helpful to practice deep breathing exercises. Deep breathing is considered by many to be a widely utilized technique that can help bring your nervous system out of fight-or-flight mode, relax your body, and quiet your mind. Many find it to be one of the most convenient ways to manage symptoms, as many can do it anywhere as needed.

To practice deep breathing prior to speaking, consider using a method called box breathing: breathe in for a four count, hold for a four-count, breathe out for a four count and hold again for a four count. You can repeat this process three to four times, possibly incorporating it with other relaxation techniques. It can also help to be mindful of your breathing as you’re presenting, which can help you steady your voice and calm your nerves.

Practice visualization

When we experience nervousness, we can sometimes focus on negative thoughts and worst-case scenarios, despite the reality of the situation. You can work to avoid this by practicing positive visualization—such as imagining friendly faces in the crowd or you acing the main content of your speech. Positive thinking can be an effective technique for managing performance anxiety.

Visualization is generally regarded as a research-backed method of addressing speaking anxiety that involves imagining the way a successful scenario will progress in detail.

Having a clear idea of how your presentation will go, even in your mind’s eye, can help you gain confidence and make you feel more comfortable with the task at hand.

Understand your subject matter

The fear of speaking in front of others can be related to potential embarrassment that may occur if we make a mistake. To reduce the risk of this possibility, it can help to develop a solid understanding of the material you’ll be presenting or performing and visualize success. For example, if you’re presenting your department’s sales numbers at work, familiarizing yourself with the important points and going over them multiple times can help you better retain the information and feel more comfortable as you give the presentation.

Set yourself up for success

Doing small things to prepare for a speech or performance can make a big difference in helping to alleviate public speaking anxiety. If possible, you may want to familiarize yourself with the location in which you’ll be speaking. It can also help to ensure any technology or other media you’ll be setting up is functional. For example, if you’re using visual aids or a PowerPoint deck, you might make sure it is being projected properly, the computer is charged and that you can easily navigate the slides as you present.

You might even conduct run-throughs of the presentation for your speaking experience. You can practice walking the exact route you’ll take to the podium, setting up any necessary materials, and then presenting the information within the time limit. Knowing how you’ll arrive, what the environment looks like and where exactly you’ll be speaking can set you up for success and help you feel more comfortable in the moment.

Practicing your presentation or performance is thought to be a key factor in reducing your fear of public speaking. You can use your practice time to recognize areas in which you may need improvement and those in which you excel as a speaker.

For example, you might realize that you start rushing through your points instead of taking your time so that your audience can take in the information you’re presenting. Allowing yourself the chance to practice can help you get rid of any filler words that may come out during a presentation and make sure all your points are clear to keep the audience’s interest. Additionally, a practice run can help you to know when it is okay to pause for effect, take some deep breaths, or work effective body language such as points of eye contact into your presentation.

It may also be helpful to practice speaking in smaller social situations, in front of someone you trust, or even a group of several familiar people. Research suggests that practicing in front of an audience of supportive, friendly faces can improve your performance—and that the larger the mock audience is, the better the potential results may be.

To do this, you can go through the process exactly like you would if they were real audience. Once you’re done, you can ask them for feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of your presentation. They may have insights you hadn’t considered and tips you can implement prior to presenting, as well as make you feel confident and relaxed about your material.

Self-care leading up to the moment you’re speaking in public can go a long way in helping you reduce nervousness. Regular physical activity is generally considered to be one proven strategy for reducing social anxiety symptoms . Exercise can help to release stress and boost your mood. If you’re giving a big presentation or speech, it may be helpful to go for a walk or do some mild cardio in the morning.

Additionally, eating a healthy diet and drinking enough water can also help promote a sense of well-being and calm. You may choose to be mindful of your consumption of caffeinated beverages, as caffeine may worsen anxiety.

How online therapy can help

If you experience anxiety when you need to speak in front of other people and want additional support for your communication apprehension, it can help to talk to a licensed mental health professional. According to the American Psychiatric Association, a therapist can work with you to find effective ways to manage public speaking anxiety and feel more confident performing in front of others.

Is Online Therapy Effective?

Studies suggest that online therapy can help individuals who experience anxiety related to presenting or performing in public. In a study of 127 participants with social anxiety disorder, researchers found that online cognitive behavioral therapy was effective in treating the fear of public speaking , with positive outcomes that were sustained for a year post-treatment. The study also noted the increased convenience that can often be experienced by those who use online therapy platforms.

Online therapy is regarded by many as a flexible and comfortable way of connecting with a licensed therapist to work through symptoms of social anxiety disorder or related mental disorders. With online therapy through BetterHelp , you can participate in therapy remotely, which can be helpful if speaking anxiety makes connecting in person less desirable.

BetterHelp works with thousands of mental health professionals—who have a variety of specialties—so you may be able to work with someone who can address your specific concerns about social anxiety.

Therapist reviews

“I had the pleasure of working with Ann for a few months, and she helped me so much with managing my social anxiety. She was always so positive and encouraging and helped me see all the good things about myself, which helped my self-confidence so much. I've been using all the tools and wisdom she gave me and have been able to manage my anxiety better now than ever before. Thank you Ann for helping me feel better!”

Brian has helped me immensely in the 5 months since I joined BetterHelp. I have noticed a change in my attitude, confidence, and communication skills as a result of our sessions. I feel like he is constantly giving me the tools I need to improve my overall well-being and personal contentment.”

If you are experiencing performance-type social anxiety disorder or feel nervous about public speaking, you may consider trying some of the tips detailed above—such as practicing with someone you trust, incorporating deep breathing techniques and visualizing positive thoughts and outcomes.

If you’re considering seeking additional support with social anxiety disorder, online therapy can help. With the right support, you can work through anxiety symptoms, further develop your oratory skills and feel more confidence speaking in a variety of forums.

Studies suggest that online therapy can help individuals who experience nervousness related to presenting or speaking in public. In a study of 127 participants with social anxiety disorder, researchers found that online cognitive behavioral therapy was effective in treating the fear of public speaking , with positive outcomes that were sustained for a year post-treatment. The study also noted the increased convenience that can often be experienced by those who use online therapy platforms.

- How To Manage Travel Anxiety Medically reviewed by Paige Henry , LMSW, J.D.

- Depression And Anxiety: The Correlation Medically reviewed by Paige Henry , LMSW, J.D.

- Relationships and Relations

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Manage Public Speaking Anxiety

Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Luis Alvarez / Getty Images

Speech Anxiety and SAD

How to prepare for a speech.

Public speaking anxiety, also known as glossophobia , is one of the most commonly reported social fears.

While some people may feel nervous about giving a speech or presentation if you have social anxiety disorder (SAD) , public speaking anxiety may take over your life.

Public speaking anxiety may also be called speech anxiety or performance anxiety and is a type of social anxiety disorder (SAD). Social anxiety disorder, also sometimes referred to as social phobia, is one of the most common types of mental health conditions.

Public Speaking Anxiety Symptoms

Symptoms of public speaking anxiety are the same as those that occur for social anxiety disorder, but they only happen in the context of speaking in public.

If you live with public speaking anxiety, you may worry weeks or months in advance of a speech or presentation, and you probably have severe physical symptoms of anxiety during a speech, such as:

- Pounding heart

- Quivering voice

- Shortness of breath

- Upset stomach

Causes of Public Speaking Anxiety

These symptoms are a result of the fight or flight response —a rush of adrenaline that prepares you for danger. When there is no real physical threat, it can feel as though you have lost control of your body. This makes it very hard to do well during public speaking and may cause you to avoid situations in which you may have to speak in public.

How Is Public Speaking Anxiety Is Diagnosed

Public speaking anxiety may be diagnosed as SAD if it significantly interferes with your life. This fear of public speaking anxiety can cause problems such as:

- Changing courses at college to avoid a required oral presentation

- Changing jobs or careers

- Turning down promotions because of public speaking obligations

- Failing to give a speech when it would be appropriate (e.g., best man at a wedding)

If you have intense anxiety symptoms while speaking in public and your ability to live your life the way that you would like is affected by it, you may have SAD.

Public Speaking Anxiety Treatment

Fortunately, effective treatments for public speaking anxiety are avaible. Such treatment may involve medication, therapy, or a combination of the two.

Short-term therapy such as systematic desensitization and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can be helpful to learn how to manage anxiety symptoms and anxious thoughts that trigger them.

Ask your doctor for a referral to a therapist who can offer this type of therapy; in particular, it will be helpful if the therapist has experience in treating social anxiety and/or public speaking anxiety.

Research has also found that virtual reality (VR) therapy can also be an effective way to treat public speaking anxiety. One analysis found that students treated with VR therapy were able to experience positive benefits in as little as a week with between one and 12 sessions of VR therapy. The research also found that VR sessions were effective while being less invasive than in-person treatment sessions.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

If you live with public speaking anxiety that is causing you significant distress, ask your doctor about medication that can help. Short-term medications known as beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol) can be taken prior to a speech or presentation to block the symptoms of anxiety.

Other medications may also be prescribed for longer-term treatment of SAD, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). When used in conjunction with therapy, you may find the medication helps to reduce your phobia of public speaking.

In addition to traditional treatment, there are several strategies that you can use to cope with speech anxiety and become better at public speaking in general . Public speaking is like any activity—better preparation equals better performance. Being better prepared will boost your confidence and make it easier to concentrate on delivering your message.

Even if you have SAD, with proper treatment and time invested in preparation, you can deliver a successful speech or presentation.

Pre-Performance Planning

Taking some steps to plan before you give a speech can help you better control feelings of anxiety. Before you give a speech or public performance:

- Choose a topic that interests you . If you are able, choose a topic that you are excited about. If you are not able to choose the topic, try using an approach to the topic that you find interesting. For example, you could tell a personal story that relates to the topic as a way to introduce your speech. This will ensure that you are engaged in your topic and motivated to research and prepare. When you present, others will feel your enthusiasm and be interested in what you have to say.

- Become familiar with the venue . Ideally, visit the conference room, classroom, auditorium, or banquet hall where you will be presenting before you give your speech. If possible, try practicing at least once in the environment that you will be speaking in. Being familiar with the venue and knowing where needed audio-visual components are ahead of time will mean one less thing to worry about at the time of your speech.

- Ask for accommodations . Accommodations are changes to your work environment that help you to manage your anxiety. This might mean asking for a podium, having a pitcher of ice water handy, bringing in audiovisual equipment, or even choosing to stay seated if appropriate. If you have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder such as social anxiety disorder (SAD), you may be eligible for these through the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

- Don’t script it . Have you ever sat through a speech where someone read from a prepared script word for word? You probably don’t recall much of what was said. Instead, prepare a list of key points on paper or notecards that you can refer to.

- Develop a routine . Put together a routine for managing anxiety on the day of a speech or presentation. This routine should help to put you in the proper frame of mind and allow you to maintain a relaxed state. An example might be exercising or practicing meditation on the morning of a speech.

Practice and Visualization

Even people who are comfortable speaking in public rehearse their speeches many times to get them right. Practicing your speech 10, 20, or even 30 times will give you confidence in your ability to deliver.

If your talk has a time limit, time yourself during practice runs and adjust your content as needed to fit within the time that you have. Lots of practice will help boost your self-confidence .

- Prepare for difficult questions . Before your presentation, try to anticipate hard questions and critical comments that might arise, and prepare responses ahead of time. Deal with a difficult audience member by paying them a compliment or finding something that you can agree on. Say something like, “Thanks for that important question” or “I really appreciate your comment.” Convey that you are open-minded and relaxed. If you don’t know how to answer the question, say you will look into it.

- Get some perspective . During a practice run, speak in front of a mirror or record yourself on a smartphone. Make note of how you appear and identify any nervous habits to avoid. This step is best done after you have received therapy or medication to manage your anxiety.

- Imagine yourself succeeding . Did you know your brain can’t tell the difference between an imagined activity and a real one? That is why elite athletes use visualization to improve athletic performance. As you practice your speech (remember 10, 20, or even 30 times!), imagine yourself wowing the audience with your amazing oratorical skills. Over time, what you imagine will be translated into what you are capable of.

- Learn to accept some anxiety . Even professional performers experience a bit of nervous excitement before a performance—in fact, most believe that a little anxiety actually makes you a better speaker. Learn to accept that you will always be a little anxious about giving a speech, but that it is normal and common to feel this way.

Setting Goals

Instead of trying to just scrape by, make it a personal goal to become an excellent public speaker. With proper treatment and lots of practice, you can become good at speaking in public. You might even end up enjoying it!

Put things into perspective. If you find that public speaking isn’t one of your strengths, remember that it is only one aspect of your life. We all have strengths in different areas. Instead, make it a goal simply to be more comfortable in front of an audience, so that public speaking anxiety doesn’t prevent you from achieving other goals in life.

A Word From Verywell

In the end, preparing well for a speech or presentation gives you confidence that you have done everything possible to succeed. Give yourself the tools and the ability to succeed, and be sure to include strategies for managing anxiety. These public-speaking tips should be used to complement traditional treatment methods for SAD, such as therapy and medication.

Crome E, Baillie A. Mild to severe social fears: Ranking types of feared social situations using item response theory . J Anxiety Disord . 2014;28(5):471-479. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.05.002

Pull CB. Current status of knowledge on public-speaking anxiety . Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(1):32-8. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834e06dc

Goldstein DS. Adrenal responses to stress . Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30(8):1433-40. doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9606-9

Anderson PL, Zimand E, Hodges LF, Rothbaum BO. Cognitive behavioral therapy for public-speaking anxiety using virtual reality for exposure . Depress Anxiety. 2005;22(3):156-8. doi:10.1002/da.20090

Hinojo-Lucena FJ, Aznar-Díaz I, Cáceres-Reche MP, Trujillo-Torres JM, Romero-Rodríguez JM. Virtual reality treatment for public speaking anxiety in students. advancements and results in personalized medicine . J Pers Med . 2020;10(1):14. doi:10.3390/jpm10010014

Steenen SA, van Wijk AJ, van der Heijden GJ, van Westrhenen R, de Lange J, de Jongh A. Propranolol for the treatment of anxiety disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis . J Psychopharmacol (Oxford). 2016;30(2):128-39. doi:10.1177/0269881115612236

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

PUBLIC SPEAKING ANXIETY

The fear of public speaking is the most common phobia ahead of death, spiders, or heights. The National Institute of Mental Health reports that public speaking anxiety, or glossophobia, affects about 40%* of the population. The underlying fear is judgment or negative evaluation by others. Public speaking anxiety is considered a social anxiety disorder. * Gallup News Service, Geoffrey Brewer, March 19, 2001.

The fear of public speaking is worse than the fear of death

Evolution psychologists believe there are primordial roots. Our prehistoric ancestors were vulnerable to large animals and harsh elements. Living in a tribe was a basic survival skill. Rejection from the group led to death. Speaking to an audience makes us vulnerable to rejection, much like our ancestors’ fear.

A common fear in public speaking is the brain freeze. The prospect of having an audience’s attention while standing in silence feels like judgment and rejection.

Why the brain freezes

The pre-frontal lobes of our brain sort our memories and is sensitive to anxiety. Dr. Michael DeGeorgia of Case Western University Hospitals, says: “If your brain starts to freeze up, you get more stressed and the stress hormones go even higher. That shuts down the frontal lobe and disconnects it from the rest of the brain. It makes it even harder to retrieve those memories.”

The fight or flight response activates complex bodily changes to protect us. A threat to our safety requires immediate action. We need to respond without debating whether to jump out of the way of on oncoming car while in an intersection. Speaking to a crowd isn’t life threatening. The threat area of the brain can’t distinguish between these threats.

Help for public speaking anxiety

We want our brains to be alert to danger. The worry of having a brain freeze increases our anxiety. Ironically, it increases the likelihood of our mind’s going blank as Dr. DeGeorgia described. We need to recognize that the fear of brain freezing isn’t a life-or-death threat like a car barreling towards us while in a crosswalk.

Change how we think about our mind going blank.

De-catastrophize brain freezes . It might feel horrible if it happens in the moment. The audience will usually forget about it quickly. Most people are focused on themselves. We’ve handled more difficult and challenging situations before. The long-term consequence of this incident is minimal.

Leave it there . Don’t dwell on the negative aspects of the incidents. Focus on what we can learn from it. Worry that it will happen again will become self-fulfilling. Don’t avoid opportunities to create a more positive memory.

Perfectionism won’t help . Setting unachievable standards of delivering an unblemished speech increases anxiety. A perfect speech isn’t possible. We should aim to do our best instead of perfect.

Silence is gold . Get comfortable with silence by practicing it in conversations. What feels like an eternity to us may not feel that way to the audience. Silence is not bad. Let’s practice tolerating the discomfort that comes with elongated pauses.

Avoidance reinforces . Avoiding what frightens us makes it bigger in our mind. We miss out on the opportunity to obtain disconfirming information about the trigger.

Rehearse to increase confidence

Practice but don’t memorize . There’s no disputing that preparation will build confidence. Memorizing speeches will mislead us into thinking there is only one way to deliver an idea. Forgetting a phrase or sentence throw us off and hastens the brain freeze. Memorizing provides a false sense of security.

Practice with written notes. Writing out the speech may help formulate ideas. Practice speaking extemporaneously using bullet points to keep us on track.

Practice the flow of the presentation . Practice focusing on the message that’s delivered instead of the precise words to use. We want to internalize the flow of the speech and remember the key points.

Practice recovering from a brain freeze . Practice recovery strategies by purposely stopping the talk and shifting attention to elsewhere. Then, refer to notes to find where we left off. Look ahead to the next point and decide what we’d like to say next. Finally, we’ll find someone in the audience to start talking to and begin speaking.

Be prepared for the worst . If we know what to do in the worst-case scenario (and practice it), we’ll have confidence in our ability to handle it. We do that by preparing what to say to the audience if our mind goes blank. Visualizing successful recovery of the worst will help us figure out what needs to be done to get back on track.

Learn to relax

Remember to breathe . We can reduce anxiety by breathing differently. Take slow inhalations and even slower exhalations with brief pauses in between. We’ll be more likely to use this technique if practiced in times of low stress.

Speak slowly . It’s natural to speed up our speech when we are anxious. Practice slowing speech while rehearsing. When we talk quickly, our brain sees it is a threat. Speaking slowly and calmly gives the opposite message to our brain.

Make eye contact with the audience . Our nerves might tell us to avoid eye contact. Making deliberate eye contact with a friendly face will build confidence and slow our speaking.

Join a group . Practice builds confident in public speaking. Groups like Toastmasters International provide peer support to hone our public speaking skill. Repeated exposure allows us to develop new beliefs about our fear and ability to speak in public.

The fear of our mind going blank during a speech is common. Job advancement or college degree completion may be hampered by not addressing this fear.

Get additional practical suggestions on overcoming public speaking anxiety in this CNBC article by the director of NSAC Brooklyn, Chamin Ajjan, LCSW, A-CBT, CST.

How to Get Help for Social Anxiety

The National Social Anxiety Center (NSAC) is an association of independent Regional Clinics and Associates throughout the United States with certified cognitive-behavioral therapists (CBT) specializing in social anxiety and other anxiety-related problems.

Find an NSAC Regional Clinic or Associate which is licensed to help people in the state where you are located.

Places where nsac regional clinics and associates are based.

Speech Anxiety

Cite this chapter.

- William J. Fremouw 2 &

- Joseph L. Breitenstein 2

1517 Accesses

5 Citations

Speech anxiety is a popularly researched area, probably due to its prevalence, the availability of subjects (usually college students), and its similarity to common clinical presentations of anxiety (Turner, Beidel, & Larkin, 1986). Of adults, 25% report “much” fear when speaking before a group (Borkovec & O’Brien, 1976). Interestingly, the definition of speech anxiety is often ambiguous and frequently goes unstated, but it is most often defined by the particular dependent measures used (e.g., questionnaires; Watson & Friend, 1969). For this chapter, speech anxiety is defined as maladaptive cognitive and physiological reactions to environmental events that result in ineffective public speaking behaviors.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Fear of Losing Control in Social Anxiety: An Experimental Approach

Development and Validation of a New Measure of Fear of Negative and Positive Evaluation

Rasch analysis reveals multidimensionality in the public speaking anxiety scale

Beck, A. (1976). Cognitive therapy and emotional disorders . New York: Plenum.

Google Scholar

Bernstein, D. A., & Borkovec, T. D. (1973). Progressive muscle relaxation: A manual for the helping professions . Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Borkovec, T. D. (1973). The effects of instructional and physiological cues on analogue fear. Behavior Therapy, 4 , 185–192.

Article Google Scholar

Borkovec, T. D., & O’Brien, G. T. (1976). Methodological and target issues in analogue therapy outcome research. In M. Hersen, E. Eisler, & P. Miller (Eds.), Progress in behavior modification (Vol. 3). New York: Academic Press.

Borkovec, T. D., Wall, R. L., & Stone, N. M. (1974). False physiological feedback and the maintenance of speech anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 83 , 164–168.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Borkovec, T. D., Weerts, T. C., & Bernstein, D. A. (1977). Assessment of anxiety. In A. R. Ciminero, K. S. Calhoun, & H. E. Adams (Eds.), Handbook of Behavioral Assessment . New York: Wiley.

Calef, R. A., & McLean, G. D. (1970). A comparison of reciprocal inhibition and reactive inhibition theories in the treatment of speech anxiety. Behavior Therapy, 1 , 51–58.

Casas, J. M. (1975). A comparison of two mediational self-control techniques for the treatment of speech anxiety . Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University.

Clevenger, T., Jr., & King, T. T. (1961). A factor analysis of the visible symptoms of stage fright. Speech Monographs, 28 , 296–298.

Craddock, C., Cotler, S., & Jason, L. (1978). Primary prevention: Immunization of children for speech anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 2 , 389–396.

Cronbach, L. J. (1957). The two disciplines of scientific psychology. American Psychologist, 12 , 671–689.

Daly, J. (1978). The assessment of social-communicative anxiety via self-reports: A comparison of measures. Communication Monographs, 45 , 204–218.

Davidson, R. J., & Schwartz, G. E. (1976). The psychobiology of relaxation and related state. In D. I. Mostofsky (Ed.), Behavior control and modification of physiological activity (pp. 280–306). New York: Prentice-Hall.

DiLoreto, A. O. (1971). Comparative psychotherapy: An experimental analysis . Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy . New York: Lyle Stuart.

Fawcett, S. B., & Miller, L. K. (1975). Training public speaking behavior: An experimental analysis of social validation. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis, 8 , 125–135.

Fremouw, W. J., & Gross, R. (1983). Issues in cognitive-behavioral treatment of performance anxiety. In P. Kendall & J. Hollon (Eds.), Advances in Cognitive-behavioral Research and Therapy (Vol. 2, pp. 279–306). New York: Academic Press.

Fremouw, W. J., Gross, R. T., Monroe, J., & Rapp, S. (1982). Empirical subtypes of performance anxiety. Behavioral Assessment, 4 , 179–193.

Fremouw, W. J., & Harmatz, M. G. (1975). A helper model for behavioral treatment of speech anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43 , 653–660.

Fremouw, W. J., & Zitter, R. E. (1978). A comparison of skills training and cognitive restructuring for the treatment of speech anxiety. Behavior Therapy, 9 , 248–259.

Garfield, S. L. (1978). Research on client variables in psychotherapy. In S. L. Garfield & A. E. Bergin (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (2nd ed., pp. 191–232). New York: Wiley.

Geer, J. H. (1965). The development of a scale to measure fear. Behavior Research and Therapy, 3 ,45–53.

Glass, C. R., Merluzzi, T. V., Biever, J. L., Larsen, K. H. (1982). Cognitive assessment of social anxiety: Development and validation of a self-statement questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6 , 37–55.

Glogower, F., Fremouw, W. J., & McCroskey, J. (1978). A component analysis of cognitive restructuring. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 2 , 209–223.

Goldfried, M. R., & Trier, C. (1974). Effectiveness of relaxation as an active coping skill. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 83 , 348–355.

Gross, R. T., & Fremouw, W. J. (1982). Progressive relaxation and cognitive restructuring for empirical subtypes of performance anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6 , 429–436.

Grossberg, J. M. (1965). Successful behavior therapy in a case of speech phobia (“stage fright”). Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 30 , 285–288.

PubMed Google Scholar

Hammen, C. L., Jacobs, M., Mayol, A., & Cochran, S. D. (1980). Dysfunctional cognitions and the effectiveness of skills and cognitive-behavioral assertion training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48 , 685–695.

Hayes, B. J., & Marshall, W. I. (1984). Generalization of treatment effects in training public speakers. Behavior Research and Therapy, 22 , 519–533.

Heimberg, R. G., Dodge, C. S., & Becker, R. E. (1987). Social phobia. In L. Michelson & M. Ascher (Eds.), Anxiety and stress disorders (pp. 280–309). New York: Guilford Press.

Horan, J. J., Hackett, G., Buchanan, J. D., Stone, C. I., & Demchik-Stone, D. (1977). Coping with pain: A component analysis of stress inoculation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1 , 211–221.

Hosford, R. E. (1969). Overcoming fear of speaking in a group. In J. D. Krumboltz & C. E. Thoreson (Eds.), Behavioral counseling . New York: Holt.

Husek, T. R., & Alexander, S. (1963). The effectiveness of the anxiety differential in examination stress situations. Education and Psychological Measurement, 23 , 309–318.

Jacobson, E. (1938). Progressive relaxation . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jaremko, M. E. (1978). A component analysis of stress inoculation: Review and prospectus. Cognitive Research and Therapy, 3 , 35–48.

Jaremko, M. E., Hadfield, R., & Walker, W. (1980). Contribution of an educational phase to stress inoculation of speech anxiety. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 50 , 495–501.

Johnson, S. C. (1967). Hierarchical clustering schemes. Psychometrika, 32 , 241–254.

Jones, R. G. (1968). A factored measure of Ellis’s irrational belief systems . Wichita: Test Systems.

Karst, T. O., & Trexler, L. D. (1970). Initial study using fixed-role and rational-emotive therapy in treating public speaking anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 34 , 360–366.

Kazdin, A. E. (1980). Research and design in clinical psychology . New York: Harper.

Kendall, P. C., & Wilcox, L. E. (1980). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for impulsivity: Concrete versus conceptual training in non-self-controlled problem children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48 , 80–91.

Kiesler, D. J. (1966). Some myths and psychotherapy research and the search for a paradigm. Psychological Bulletin, 65 , 110–136.

Kirsch, I., Wolpin, M., & Knutson, J. L. (1975). A comparison of in vivo methods for rapid reduction of “stage fright” in the college classroom: A field experiment. Behavior Therapy, 6 , 165–171.

Lang, P. J. (1977). Physiological assessment of anxiety and fear. In J. D. Cone & R. P. Hawkins (Eds.), Behavioral assessment: New directions in clinical psychology (pp. 177–195). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Lang, P. J. (1969). The mechanics of desensitization and the laboratory study of human fear. In C. Franks (Ed.), Assessment and status of the behavior therapies . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Last, C. G., & Hersen, M. (Eds.). (1988). Handbook of anxiety disorders . New York: Pergamon Press.

Lazarus, R. (1972). A cognitively oriented psychologist takes a look at biofeedback. American Psychologist, 30 , 553–560.

Lent, R. W., Russell, R. K., & Zamostny, K. P. (1981). Comparison of cue-controlled desensitization, rational restructuring, and a credible placebo in the treatment of speech anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49 , 235–243.

Lindemann, H. (1973). Relieve tension the autogenic way . New York: Wyden.

Luthe, W. (1969). Autogenic therapy . New York: Grune & Stratton.

Malleson, N. (1959). Panic and phobia. Lancet, 1 , 225–227.

Mandler, G., Mandler, J., & Uviller, E. (1958). Autonomic feedback: The perception of autonomic activity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 56 , 367–373.

Mannion, N. E., & Levine, B. A. (1984). Effects of stimulus representation and cue category level on exposure (flooding) therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23 , 1–7.

Marshall, W. L., Preese, L., & Andrews, W. R. (1976). A self-administered program for public speaking anxiety. Behavior Research and Therapy, 14 , 33–39.

McCroskey, J. C. (1970). Measures of communication-bound anxiety. Speech Monographs, 37 , 269–277.

Meichenbaum, D. (1969). The effects of instructions and reinforcement on thinking and language behaviors of schizophrenics. Behavior Research and Therapy, 7 , 101–114.

Meichenbaum, D. (1972). Cognitive modification of test anxious college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 39(3), 370–380.

Meichenbaum, D. (1977). Cognitive-behavior modification: An integrative approach . New York: Plenum.

Book Google Scholar

Meichenbaum, D. (1985). Stress inoculation training . New York: Pergamon Press.

Meichenbaum, D. H., Gilmore, J. B., & Fedoravicius, A. (1971). Group insight versus group systematic desensitization in treating speech anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 36 , 410–421.

Mikulas, W. L. (1976). A televised self-control clinic. Behavior Therapy, 7 , 564–566.

Mulac, A., & Sherman, A. R. (1974). Behavioral assessment of speech anxiety. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 60 , 134–143. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Osberg, J. W. (1981). The effectiveness of applied relaxation in the treatment of speech anxiety. Behavior Therapy, 12 , 723–729.

Paul, G. L. (1966). Insight versus desensitization in psychotherapy . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Paul, G. (1988). Two year follow-up of systematic desensitization in therapy groups. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 73 , 119–130.

Paul, G. L. (1969). Behavior modification research: Design and tactics. In C. M. Franks (Ed.), Behavior therapy: Appraisal and status . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Polin, A. T. (1959). The effects of flooding and physical suppression as extinction techniques on an anxiety motivated avoidance locomotor response. Journal of Psychology, 47 , 235–245.

Rimm, D. C., & Masters, J. C. (1979). Behavior therapy . New York: Academic Press.

Schwartz, R., & Gottman, J. (1976). Toward a task analysis of assertive behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 44 , 910–920.

Sherman, A. R., & Plummer, I. L. (1973). Training in relaxation as a behavioral self-management skill: An exploratory investigation. Behavior Therapy, 4 , 543–550.

Slivken, K. E., & Buss, A. H. (1984). Misattribution and speech anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47 , 396–402.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory . Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press.

Stampfl, T. G. (1961). Implosive therapy: A learning theory derived psychodynamic therapeutic technique. In K. Lebarba, & G. Dent (Eds.), Critical issues in clinical psychology . New York: Academic Press.

Thorpe, G., Amatu, H., Blakey, R., & Burns, L. (1976). Contribution of overt instructional rehearsal and “specific insight” to the effectiveness of self-instructional training: A preliminary study. Behavior Therapy, 7 , 504–511.

Trexler, L., & Karst, T. O. (1972). Rational emotive therapy, placebo, and no treatment effects on public speaking anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 79 , 60–67.

Trussell, R. P. (1978). Use of graduated behavior rehearsal, feedback, and systematic desensitization for speech anxiety. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 25 , 14–20.

Turner, S. M., & Beidel, D. C. (1985). Empirically derived subtypes of social anxiety. Behavior Therapy, 16 , 384–392.

Turner, S. M., Beidel, D. C., & Larkin, K. T. (1986). Situational determinants of social anxiety in clinic and nonclinic samples: Physiological and cognitive correlates. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54 , 523–527.

Watson, D., & Friend, R. (1969). Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33 , 448–457.

Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Wolpe, J. (1969). The practice of behavior therapy . Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Wolpe, J. (1973). The practice of behavior therapy (2nd ed.). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Worthington, E. L., Jr., Tipton, R. M., Cromely, J. S., Richards, T., & Janke, R. H. (1984). Speech and coping skills training and paradox as treatment for college students anxious about public speaking. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 59 , 394.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia, 26506-6040, USA

William J. Fremouw & Joseph L. Breitenstein

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, USA

Harold Leitenberg

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1990 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Fremouw, W.J., Breitenstein, J.L. (1990). Speech Anxiety. In: Leitenberg, H. (eds) Handbook of Social and Evaluation Anxiety. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2504-6_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2504-6_15

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4899-2506-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-4899-2504-6

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Speech anxiety

Being nervous and anxious are normal reactions when preparing and delivering a speech. There is no real way to completely remove these feelings, but there are some ways to lessen them or to even use them to enhance the speech.

Confidence in the content and importance of a speech will take away most anxiety. It is hard to be confident if time has not been spent preparing and practicing. Remember a speech does NOT have to be perfect. They are meant to be a conversation with the audience.

Procrastination is the enemy

- Information will come more naturally to you as you are speaking

- The need to refer to notes lessens the more you practice making you more confident

Topic selection

- Select a topic that is familiar—allows you to have a connection with the topic. This connection will show as you relate information to the audience.

- Convey your enthusiasm about your topic to your audience

- Keep the speech conversational—comfort with the topic will make it easier for you to relay your thoughts and findings to the audience.

Be prepared

The more prepared you are for your speech the more familiar the information will be to you, allowing for your memory to fill in gaps as you are giving the speech.

- The more you know about the topic, the more confident you will be with the information you are relaying

- Having a prepared outline gives you a safety net. You may never refer to it, but it is there if you need a reminder of where you are

- The more comfortable you are with your speech the more relaxed and less anxious you will appear

Know the introduction and conclusion

- The audience may not remember the details in the middle of speech but they will remember the beginning and ending

- Audience will believe you covered all of your points

- Words will come naturally and not feel as though you are forcing the topic

Remember to breathe

Take a few deep breaths before standing up to speak—studies show this actually helps to reduce stress and anxiety.

- Try to relax your entire body—will make you appear at ease to the audience

Remember general health

Make sure you eat, get sleep and drink water prior to your speech.

- One time when caffeine may not be your friend—treat yourself to Starbucks after your speech

Nervous energy

The goal is to appear as calm, relaxed, and poised as possible to build credibility with the audience and boost your confidence.

- Take a slow walk before your speech—clears your mind and helps you focus

- Keep both feet planted on the floor as you wait—keeps you from toe tapping or looking too antsy

- Gently squeeze the edge of the chair—eases tension in your upper body and helps avoid fidgeting

- Think and act calm—especially during the walk to front of room. The calmer you appear the more you will believe you are calm.

- Take a moment—look for a friendly face, then begin

Additional tips to remember

- The audience doesn’t want you to fail (all your peers in the room are going through the same thing)

- Some nervous energy is good—it can be channeled into your delivery

- Focus on the audience (how can you relate to them or bring them into the speech?)

- Be in the moment. Enjoy telling and conversing with the audience about your topic

Beebe, S. A., & Beebe, S. J. (2012). A concise public speaking handbook . Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Lucas, S. (2012). The art of public speaking . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Sprague, J. & Stuart, D. (2013). The speaker's compact handbook, 4th ed . Portland: Ringgold, Inc.

Vrooman, S. S. (2013). The zombie guide to public speaking: Why most presentations fail, and what you can do to avoid joining the horde . Place of publication not identified: CreateSpace.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3: Managing Speech Anxiety

This chapter, except where otherwise noted, is adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 .

How do I manage my speech anxiety?

Now that you have an understanding of how important it is for you to use ethical principles in creating an effective speech, let’s move to the topic you have all been either dreading or can’t wait to learn about: how to manage speech anxiety.

Take a look at this scene from the Albert Meets Hitch video and see if you can relate to how nervous these people are.

Hitch: Albert meets Hitch HD CLIP , by Binge Society – The Greatest Movie Scenes , Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MIBzVc3kJAM

You can imagine how much better this interaction would have gone had the participants not been so anxious. The question is, is it possible to manage your speech anxiety during a conversation, a job interview, or a speech?

Speech Anxiety/Communication Apprehension

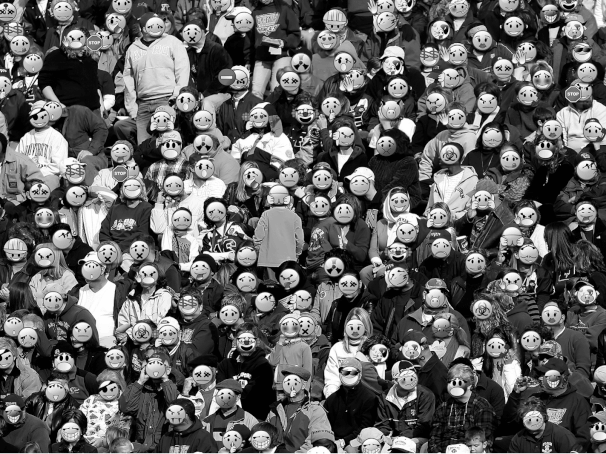

Many different social situations can make us feel uncomfortable if we anticipate that we will be evaluated and judged by others. The process of revealing ourselves and knowing that others are evaluating us can be threatening whether we are meeting new acquaintances, participating in group discussions, or speaking in front of an audience.

Definition of Communication Apprehension

According to James McCroskey, communication apprehension is the broad term that refers to an individual’s “fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” (McCroskey, 2001). At its heart, communication apprehension is a psychological response to evaluation. This psychological response, however, quickly becomes physical as our body responds to the threat the mind perceives. Our bodies cannot distinguish between psychological and physical threats, so we react as though we are facing a Mack truck barreling in our direction. The body’s circulatory and adrenal systems shift into overdrive, preparing us to function at maximum physical efficiency, kicking in the “flight or fight” response (Sapolsky, 2004). Yet instead of running away or fighting, all we need to do is stand and talk.

The excess energy our body creates can make it harder for us to be effective public speakers. But because communication apprehension is rooted in our minds, if we understand more about the body’s responses to stress, we can better develop mechanisms for managing the body’s misguided attempts to help us cope with social judgment fears.

Physiological Symptoms of Communication Apprehension

There are various physical sensations associated with communication apprehension. We might notice our heart pounding or our hands feeling clammy. We may break out in a sweat, have stomach butterflies, or even feel nauseated. Our hands and legs might start to shake, or we may begin to pace nervously. Our voices may quiver, and we may have a dry-mouth sensation that makes it difficult to articulate even simple words. Breathing becomes more rapid, and, in extreme cases, we might feel dizzy or light-headed. Communication anxiety is profoundly disconcerting because we feel powerless to control our bodies. We may become so anxious that we fear we will forget our name, much less remember the main points of the speech we are about to deliver.

The physiological changes our bodies produce at critical moments are designed to contribute to ensure our muscles work efficiently and expand available energy. Circulation and breathing become more rapid so that additional oxygen can reach the muscles. Increased circulation causes us to sweat. Adrenaline rushes through our body, instructing the body to speed up its movements. If we stay immobile behind a lectern, this hormonal urge to speed up may produce shaking and trembling. Additionally, digestive processes are inhibited so we will not lapse into the relaxed, sleepy state that is typical after eating. Instead of feeling sleepy, we feel butterflies in the pit of our stomach. By understanding what is happening to our bodies in response to public speaking stress, we can better cope with these reactions and channel them in constructive directions.

Watch this Ted Ed video, The Science of Stage Fright by Mikael Cho. In it, Cho shares what physically happens when we become anxious. It is now called the “fight, flight, or freeze” response because sometimes we hold very still when frightened.

The video can make you feel scared just watching it, but try and notice that there is an actual science to stage fright or speech anxiety, and you are not alone in feeling nervous or scared.

Pay particular attention near the end when Cho gives you one option to help manage your anxiety.

The science of stage fright (and how to overcome it) – Mikael Cho , by TED-Ed , Standard YouTube License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K93fMnFKwfI

After watching the video, did you realize that anxiety is a normal human reaction? We can help reduce the anxiety, but not totally eliminate it. As you continue with this module you will learn strategies to reduce anxiety.

- Any conscious emotional state, such as anxiety or excitement consists of two components:

- A primary reaction of the central nervous system.

- An intellectual interpretation of these physiological responses.

The physiological state we label as communication anxiety does not differ from those that we label rage or excitement. Even seasoned effective speakers and performers experience some communication apprehension. What differs is the mental label that we put on the experience. Effective speakers have learned to channel their body’s reactions, using the energy released by these physiological reactions to create animation and stage presence.

It has been documented that famous speakers throughout history such as Cicero, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln, Eleanor Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Gloria Steinem conquered significant public speaking fears. Celebrities who experience performance anxiety include actor Harrison Ford, Beyonce, Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Rihanna, Matt Damon, and George Clooney (Hickson, 2016).

Myths about Communication Apprehension

Before we look at how to manage our speech anxiety, let’s dispel some myths.

- People who suffer from speaking anxiety are neurotic. As we have explained, speaking anxiety is a normal reaction. Good speakers can get nervous, too, just as poor speakers do.

- Telling a joke or two is always a good way to begin a speech. Humor is some of the toughest material to deliver effectively because it requires an exquisite sense of timing. Nothing is worse than waiting for a laugh that does not come. Moreover, one person’s joke is another person’s slander. It is extremely easy to offend when using humor. The same material can play very differently with different audiences. For these reasons, it is not a good idea to start with a joke, particularly if it is not well related to your topic. Humor is just too unpredictable and difficult for many novice speakers. If you insist on using humor, make sure the joke is on you, not on someone else. Another tip is never to pause and wait for a laugh that may not come. If the audience catches the joke, fine. If not, you’re not left standing in awkward silence waiting for a reaction.

- Imagine the audience is naked. This tip just plain doesn’t work because imagining the audience naked will do nothing to calm your nerves. The audience is not some abstract image in your mind. It consists of real individuals who you can connect with through your material.

- Any mistake means that you have “blown it.” We all make mistakes. What matters is how well we recover, not whether we make a mistake. A speech does not have to be perfect. You just have to make an effort to relate to the audience naturally and be willing to accept your mistakes.

- Audiences are out to get you. An audience’s natural state is empathy, not antipathy. Most face-to-face audiences are interested in your material, not in your image. Watching someone who is anxious tends to make audience members anxious themselves. Particularly in public speaking classes, audiences want to see you succeed. They know that they will soon be in your shoes, and they identify with you, most likely hoping you’ll succeed and give them ideas for how to make their own speeches better. If you establish direct eye contact with real individuals in your audience, you will see them respond to what you are saying, and this response lets you know that you are succeeding.

- You will look as nervous as you feel. Empirical research has shown that audiences do not perceive the level of nervousness that speakers report feeling (Clevenger, 1959). Most listeners judge speakers as less anxious than the speakers rate themselves. In other words, the audience is not likely to perceive accurately your anxiety level. Some of the most effective speakers will return to their seats after their speech and exclaim they were so nervous. Listeners will respond, “You didn’t look nervous.” Audiences do not necessarily perceive our fears. Consequently, don’t apologize for your nerves. There is a good chance the audience will not notice that you’re nervous if you do not point it out to them.

- TRUE. A little nervousness helps you give a better speech. This myth is true! Professional speakers, actors, and other performers consistently rely on their nervous heightened arousal to channel extra energy into their performance. People would much rather listen to a speaker who is alert and enthusiastic than one who is relaxed to the point of boredom. Many professional speakers say that the day they stop feeling nervous is the day they should stop public speaking. The goal is to control those nerves and channel them into your presentation.

Common yet unexpected difficulties can increase speech anxiety: how do we cope?

The following sections are adapted from Stand up, Speak out: The Practice and Ethics of Public Speaking , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 .

Speech Content Issues