- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Berlin Wall

By: History.com Editors

Updated: November 16, 2023 | Original: December 15, 2009

On August 13, 1961, the Communist government of the German Democratic Republic (GDR, or East Germany) began to build a barbed wire and concrete “Antifascistischer Schutzwall,” or “antifascist bulwark,” between East and West Berlin. The official purpose of this Berlin Wall was to keep so-called Western “fascists” from entering East Germany and undermining the socialist state, but it primarily served the objective of stemming mass defections from East to West. The Berlin Wall stood until November 9, 1989, when the head of the East German Communist Party announced that citizens of the GDR could cross the border whenever they pleased. That night, ecstatic crowds swarmed the wall. Some crossed freely into West Berlin, while others brought hammers and picks and began to chip away at the wall itself. To this day, the Berlin Wall remains one of the most powerful and enduring symbols of the Cold War.

The Berlin Wall: The Partitioning of Berlin

As World War II came to an end in 1945, a pair of Allied peace conferences at Yalta and Potsdam determined the fate of Germany’s territories. They split the defeated nation into four “allied occupation zones”: The eastern part of the country went to the Soviet Union , while the western part went to the United States, Great Britain and (eventually) France.

Even though Berlin was located entirely within the Soviet part of the country (it sat about 100 miles from the border between the eastern and western occupation zones), the Yalta and Potsdam agreements split the city into similar sectors. The Soviets took the eastern half, while the other Allies took the western. This four-way occupation of Berlin began in June 1945.

The Berlin Wall: Blockade and Crisis

The existence of West Berlin, a conspicuously capitalist city deep within communist East Germany, “stuck like a bone in the Soviet throat,” as Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev put it. The Russians began maneuvering to drive the United States, Britain and France out of the city for good. In 1948, a Soviet blockade of West Berlin aimed to starve the western Allies out of the city. Instead of retreating, however, the United States and its allies supplied their sectors of the city from the air. This effort, known as the Berlin Airlift , lasted for more than a year and delivered more than 2.3 million tons of food, fuel and other goods to West Berlin. The Soviets called off the blockade in 1949.

Did you know? On October 22, 1961, a quarrel between an East German border guard and an American official on his way to the opera in East Berlin very nearly led to what one observer called "a nuclear-age equivalent of the Wild West Showdown at the O.K. Corral." That day, American and Soviet tanks faced off at Checkpoint Charlie for 16 hours. Photographs of the confrontation are some of the most familiar and memorable images of the Cold War.

After a decade of relative calm, tensions flared again in 1958. For the next three years, the Soviets–emboldened by the successful launch of the Sputnik satellite the year before during the “ Space Race ” and embarrassed by the seemingly endless flow of refugees from east to west (nearly 3 million since the end of the blockade, many of them young skilled workers such as doctors, teachers and engineers)–blustered and made threats, while the Allies resisted. Summits, conferences and other negotiations came and went without resolution.

Meanwhile, the flood of refugees continued. In June 1961, some 19,000 people left the GDR through Berlin. The following month, 30,000 fled. In the first 11 days of August, 16,000 East Germans crossed the border into West Berlin, and on August 12 some 2,400 followed—the largest number of defectors ever to leave East Germany in a single day.

The Berlin Wall: Building the Wall

That night, Premier Khrushchev gave the East German government permission to stop the flow of emigrants by closing its border for good. In just two weeks, the East German army, police force and volunteer construction workers had completed a makeshift barbed wire and concrete block wall –the Berlin Wall–that divided one side of the city from the other.

Before the wall was built, Berliners on both sides of the city could move around fairly freely: They crossed the East-West border to work, to shop, to go to the theater and the movies. Trains and subway lines carried passengers back and forth. After the wall was built, it became impossible to get from East to West Berlin except through one of three checkpoints: at Helmstedt (“Checkpoint Alpha” in American military parlance), at Dreilinden (“Checkpoint Bravo”) and in the center of Berlin at Friedrichstrasse (“Checkpoint Charlie”). (Eventually, the GDR built 12 checkpoints along the wall.) At each of the checkpoints, East German soldiers screened diplomats and other officials before they were allowed to enter or leave. Except under special circumstances, travelers from East and West Berlin were rarely allowed across the border.

The Berlin Wall: 1961-1989

The construction of the Berlin Wall did stop the flood of refugees from East to West, and it did defuse the crisis over Berlin. (Though he was not happy about it, President John F. Kennedy conceded that “a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.”) Almost two years after the Berlin Wall was erected, John F. Kennedy delivered one of the most famous addresses of his presidency to a crowd of more than 120,000 gathered outside West Berlin’s city hall, just steps from the Brandenburg Gate . Kennedy’s speech has been largely remembered for one particular phrase. “I am a Berliner.”

In all, at least 171 people were killed trying to get over, under or around the Berlin Wall. Escape from East Germany was not impossible, however: From 1961 until the wall came down in 1989, more than 5,000 East Germans (including some 600 border guards) managed to cross the border by jumping out of windows adjacent to the wall, climbing over the barbed wire, flying in hot air balloons, crawling through the sewers and driving through unfortified parts of the wall at high speeds.

The Berlin Wall: The Fall of the Wall

On November 9, 1989, as the Cold War began to thaw across Eastern Europe, an East German Communist Party spokesman announced a series of new policies regarding border crossings. When pressed on when the changes would take place, he said “As far as I know... effective immediately, without delay.” East Berliners flocked to border checkpoints, some chanting “Tor auf!” (“Open the gate!”). Within hours, the guards were letting the crowds through, where West Berliners greeted them with flowers and champagne.

More than 2 million people from East Berlin visited West Berlin that weekend to participate in a celebration that was, one journalist wrote, “the greatest street party in the history of the world.” People used hammers and picks to knock away chunks of the wall–they became known as “mauerspechte,” or “wall woodpeckers”—while cranes and bulldozers pulled down section after section. Soon the wall was gone and Berlin was united for the first time since 1945. “Only today,” one Berliner spray-painted on a piece of the wall, “is the war really over.”

The reunification of East and West Germany was made official on October 3, 1990, almost one year after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

HISTORY Vault: Declassified: Rise and Fall of the Wall

Mine formerly guarded vaults and archives around the world to reveal untold stories about the brutal life and catastrophic death of the Berlin Wall, a central symbol of the 20th century's longest and deadliest war.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Home — Essay Samples — Geography & Travel — Berlin — The history of Berlin wall

The History of Berlin Wall

- Categories: Berlin Germany

About this sample

Words: 1569 |

Published: Sep 20, 2018

Words: 1569 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Table of contents

Berlin wall essay outline, berlin wall essay example, introduction.

- The significance of the Berlin Wall in dividing East and West Berlin

- The political context of the Allies and Soviets in post-World War II Berlin

The Berlin Wall's Construction and Purpose

- Nikita Khrushchev and Walter Ulbricht's decision to build the Berlin Wall

- The role of the Berlin Wall in preventing East Berliners from fleeing to the West

- Efforts to retain essential workers in East Berlin

The Challenges of Crossing the Berlin Wall

- Description of the physical barriers, including the "Death Strip"

- The desperation of East Berliners and creative methods used to cross

- The impact on families and professional lives due to the wall

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

- Schabowski's announcement and its consequences

- The destruction of the wall by the people

- The broader implications of the Berlin Wall's fall, including the end of the Cold War and reunification of Germany

Consequences and Legacy

- The lasting impact of the Berlin Wall on the people of Berlin

- The role of the wall in shaping the city's landscape

- Reflections on the significance of both the rise and fall of the Berlin Wall

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Geography & Travel

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1235 words

2 pages / 761 words

2 pages / 842 words

2 pages / 1161 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Berlin

In June of 1987, the world looked to President Ronald Reagan as he traveled to Berlin to address the impact of one of the world’s greatest symbols of communism: The Berlin Wall. For nearly twenty years, the “Iron Curtain” stood [...]

Robert Walser’s “Berlin Stories” is a collection of vignettes that track his observation during his jaunts through the city. Walter Benjamin’s “Berlin Childhood Around 1900” is an attempt by Benjamin to recollect his urban [...]

Before the Second World War, Germany was a revered state due to its development that was characterised by exceptional infrastructure, beautiful cities, and factories. However, the outlook would change drastically after the [...]

In The Histories, Herodotus offers an account of the events leading to the Greco-Persian Wars between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states of 5th century BC and attempts to determine “the reason why they fought one [...]

The Irish National Accreditation Board (INAB) the state organization with the responsibility for the accreditation of laboratories, certification bodies, and inspection bodies. It provides accreditation in conjunction with the [...]

A democratic deficit occurs when government or government institutions fall short of fulfilling the principles of democracy in their practices or operation or where political representatives and institutions are discredited in [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Reflections on the Fall of the Berlin Wall

November 9, 2019, marked the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. On that day, Edwin J. Feulner was in Budapest, Hungary, giving a speech at a conference at the Danube Institute. This essay is adapted from Feulner’s remarks.

We have gathered today to remember an event that took place thirty years ago, in 1989—that “year of miracles” when the Warsaw Pact crumbled and when the Berlin Wall, which had been standing for twenty-eight years, was finally breached and torn down.

It was a keen personal moment for me. I had met freedom fighters from inside the Soviet Union and from the countries of Central Europe, yearning for the freedom we in the Western democracies enjoyed. These were heady days that tested the will, and the integrity, of men and women on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

As a college student in 1961, I had been traveling in West Germany with a group of my college classmates (and a Jesuit chaperone!). We were in Munich for my twentieth birthday—August 12, 1961. The next afternoon we planned to drive our VW minibuses on the Corridor through the DDR to West Berlin. Watching local television in a Munich beer hall that evening, we learned that East German and Soviet troops were massing in East Berlin. This gave us pause—that night the first barbed-wire Berlin Wall was erected. We didn’t make the trip to Berlin that day. And, of course, the reinforced wall stood for twenty-eight years as a grim reminder of its primary goal—to keep its people in.

That wall was a physical expression of the evils of totalitarianism, of the attempt to obliterate the will that lives in all of us to be free.

Another personal recollection: By the mid-1960s, after flitting from university to university in Denver, Philadelphia, London, Edinburgh, and Salzburg, I had found a niche at the Center for Strategic Studies in Washington, where the person occupying the nice windowed office in front of my modest desk was the legendary retired State Department desk officer for Berlin, Eleanor Lansing Dulles. Eleanor was the sister of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and CIA Director Allen Dulles. I helped Eleanor with research for her classic volume published in 1967, Berlin: The Wall Is Not Forever . [1]

I have been asked to provide an American perspective on this historic moment, and I want to do this by describing what the view of communism was from afar, the after-effects of the wall’s collapse on the American political landscape, and why the legacy of the Berlin Wall is still relevant to the United States today.

Simply stated: In my opinion, the fall of the Berlin Wall was one of the most significant events of the twentieth century.

As an American who took part in public-policy battles in Washington, but who was nonetheless watching from afar, seeing the wall come down was immensely satisfying and movingly emotional.

The wall symbolized what we already knew: that communism was a system built on a fragile foundation, one that would not last. Communism everywhere and all the time must rely on coercion. That means that its leaders can never ease up on repression. The moment they do, the people tear down the barriers that keep them down.

Since the Berlin Airlift of 1948–49, we had watched as the people of East Germany suffered under the iron grip of communism. While the rest of the world moved forward, the strongholds of communism remained stagnant, weighed down in the muck and mire of a failing ideology. Communism produced failure and decay even in Germany, among some of the most industrious and hardworking people anywhere.

The Failure of the Socialist System

The reason for this failure, from a technical standpoint, was economic in nature. By the time Mikhail Gorbachev became secretary-general of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1985, the Soviet Union could no longer afford the cost of maintaining its empire. Its demise seemed to be inevitable to many of us.

Several sensible economists, led by Professor G. Warren Nutter, with whom I served in Melvin Laird’s Pentagon in the late 1960s, described in detail the weakness of the Soviet economic system and the falsified data concerning it that so many had relied on and endorsed. [2] It is important to note, however, that even as late as the 1980s the Soviet Union still had fans among such American intellectuals as John Kenneth Galbraith. They were wrong and we were right, and finally, the Iron Curtain began to be dismantled, and the Berlin Wall came down.

For this we must thank, first and foremost, the people of Eastern and Central Europe.

And we must thank specifically the leaders of Poland’s Solidarity Movement, Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia (as it then was), and other heroes and heroines of the Captive Nations.

But the communist system had failed on a level far deeper than the economic. Like many before them, the Soviets failed to take into account one immutable fact: human nature.

Permit me to quote a person not often cited by Americans, but a real hero in the war against the totalitarian adversary of communism. I speak here of a man I first met in 1965 in the Bavarian town of Pocking, Otto von Habsburg. I had traveled from my temporary base in Salzburg, where I was studying the German language, to meet a man whom I had heard of and whom I admired from afar. In that first meeting, I boldly asked him to write an article—a “think piece”—about the future of communism for a new journal where I, as a graduate student, was a deputy editor, the Intercollegiate Review. He agreed, and a year later that article appeared in our journal . [3]

Dr. Habsburg concluded in this article:

This [the revolt of writers in the Eastern European states] reveals the decisive defeat the system has suffered—a defeat which is no longer directly related to economic success or crises, to foreign policy, or to the strategy of domestic politics. The cause of this defeat, rather, must be looked for in the human psyche which, in the long run, will not tolerate shackles.

Or, as an American political leader, Ronald Reagan, said it in less elevated language some years later:

Socialists ignore the side of man that is the spirit. They can provide you shelter, fill your belly with bacon and beans, treat you when you’re ill, all the things guaranteed to a prisoner or a slave. They don’t understand that we also dream.

In short, it is not obedience or deference to the state that motivates people. Nor is it the accumulation of material wealth that gives us purpose. Rather, it is the prospect to dream, to dare, and to improve our lot in life.

Communism ignored that individual freedom is the key to a prosperous and flourishing people and hence a prosperous and flourishing nation.

Communism in this sense is the heir to the traditions of Kant and Hegel, who argued that freedom can be realized only through the state. We Americans, and many of you here, are heirs to the Anglo-Scots Enlightenment, which saw government as being able only to protect liberties we received from God or nature.

In the Berlin Wall, we saw the physical manifestation of the tenets of communism: a structure built to hold a people hostage to tyranny—yet built on such a poor foundation that it would not, and could not, last. Communism, by nature, builds its house on the sands of repression.

The fall of the wall proved to the world that, despite what proponents of Marxism would have us believe, communism’s one and only function is to be the mechanism of the power-hungry, consigning the people under its rule to lives of poverty and spiritual misery, of obedience to the state, and a yearning to return to lives of freedom and opportunity once again.

For the period 1982–93, under three American presidents of both political parties, I served, with U.S. Information Agency director Charles Wick, a longtime friend of President Reagan, as the part-time chairman of the United States Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy. Our bipartisan group traveled to more than forty countries on every continent, visited with governmental leaders and senior American representatives in all the world’s flashpoints. We worked with a bipartisan group in our Congress to increase funding for the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty, the Fulbright Program to promote academic exchanges, and programs around the world. Our theme was to focus U.S. governmental efforts to “tell America’s story around the world.”

Simultaneously, inside the White House, Ronald Reagan was being tested by Moscow. Reagan’s initial test came in the first month of his first term (January–February 1981). The Polish communist government declared martial law in order to clamp down on Solidarity. The new American president wanted to respond vigorously. As he said in his own memoirs, if Solidarity presented such a real challenge to the Polish government, and to Moscow, then “this is what we have been waiting for.” He realized that “what was happening in Poland might spread like a contagion throughout Eastern Europe.” [4] In several National Security Council meetings, the president met resistance from Secretary of State Alexander Haig and Vice President George H. W. Bush. But with strong support from CIA Director Bill Casey, Counselor Edwin Meese, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, and National Security Adviser Bill Clark, he followed a Casey plan for clandestine help to Solidarity in subsequent months and years. That transfusion of millions of dollars helped keep Solidarity alive.

Fast-forward two years, to March 13, 1983: Ronald Reagan announces his Strategic Defense Initiative, to replace the long-standing policy of Mutual Assured Destruction. In his speech he called on America’s scientists, who had created nuclear weapons, to turn their great talents to give us the “means of rendering these nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete.” [5]

Henry Kissinger, no particular friend of Reagan, said it well retrospectively: “These last words, ‘impotent and obsolete,’ must have had a chilling effect on the Kremlin. . . . Now with a single technological stroke, Reagan was proposing to erase everything that the Soviet Union had propelled itself into bankruptcy trying to accomplish.” [6]

I dwell on these early developments because they probably would not have occurred under another president, of either political party—certainly not Jimmy Carter (remember American hostages in Iran?), nor George H. W. Bush, for whom I have a great deal of respect, but who said, on several occasions, “I don’t do the ‘vision thing.’” And the “vision thing” was what Ronald Reagan advocated so ably.

1989: The Year of Miracles

Yes, 1989 was the “year of miracles,” and it started before November.

On June 20, 1989, Otto von Habsburg, a member of the European Parliament, addressed an audience at Hungary’s University of Debrecen with his vision of a Europe without borders and the prospective role of the European Parliament elections’ impact on Central Europe. On that occasion, his Hungarian hosts suggested a summer picnic near the border with Austria.

The historic Pan-European Movement’s picnic on the Bratislava Road at Sopron, Hungary, occurred in August 1989. Otto von Habsburg chaired the event at this small town, which had been a border crossing to Austria for almost a century.

And then the Hungarian government opened that border to Austria, permitting several hundred East German citizens to reach Austria. That was really the first break in the wall.

Demand for movement from thousands of visiting East Germans increased, and the Hungarian government completely opened its border with Austria on September 11, to enable thousands of Central Europeans to cross to the West from the formerly impenetrable Iron Curtain countries.

East Germany’s Erich Honecker said: “Habsburg distributed pamphlets right up to the Polish border, inviting East German holiday-makers to picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given presents, food, and Deutsche Marks, before being persuaded to go over to the West.” [7]

On November 9, the Berlin Wall fell after standing for twenty-eight years.

The Iron Curtain came down.

The Warsaw Pact disintegrated, and the Cold War was over.

“We have won!” so many proclaimed.

The wall came down on President George H. W. Bush’s watch, thanks to the efforts so many citizens of Central Europe and a host of unheralded leaders on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

But it came down most of all, as John O’Sullivan said, because of the extraordinary leadership of and collaboration among Pope John Paul II, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and especially President Ronald Reagan. [8]

American Reaction

Meanwhile, in the United States, euphoria was rampant at the Bush White House, even if our deliveries were not as great as they might (and should) have been.

In these heady months after the fall of the Berlin Wall, my Heritage Foundation colleagues and I made a dozen trips to Moscow, where we worked with reform members of the Duma, eventually including President Boris Yeltsin. Under the guidance of Ambassador Bill Middendorf, a Heritage Foundation trustee, we actually drafted a new constitution for the emerging Russian Republic. We hosted dinners and conferences to promote a new legal system and a privatized free economy. These efforts came to very little as the Russian system went through continual stress and strains. We tried hard, and even operated a Heritage Foundation full-time Moscow office for more than four years, before governmental regulations forced us to close.

The ripple effect of the crumbling of the Berlin Wall was felt strongly in America. It gave us the opportunity for a new start. According to our president, George H. W. Bush, we would enjoy a “peace dividend.”

The fall of the wall did usher in an era of openness toward a small-government, conservative policy that hadn’t been seen since the Second World War.

And yet, in hindsight, did we achieve all that we might have? Certainly not. Democracies don’t work that way. They are messy. Conflicting aims divided people and created obstacles to achieving shared values.

I believe that the United States should have cooperated with the leaders of the emerging governments to ensure that the debt inheritance from the communist predecessors did not hinder real economic growth in these emerging democracies of Central Europe. After what the United States had done with the Marshall Plan at the end of World War II, we should have done better in 1989. But we didn’t.

The United States moved from Bush to Bill Clinton in 1993. We went from focus on the fall of the wall to the disintegration of Yugoslavia and that internal civil war that would preoccupy Europe and us. President Clinton’s challenges shifted from integrating most of Central Europe into a whole Europe, into coping with Serb-Croat animosity, Rwanda genocide, and other crises around the world.

Politicians and executive branch officials moved on to other, “new and more exciting challenges.” Politicians, as a reflection of the people (the voters), tend to lose the longer-term perspective. Everything is decided in the context of the next election rather than the next generation. As I remind many friends who lament Washington’s short attention span, all often in Washington the urgent overwhelms the important.

And some of the work that had been done was undercut by bureaucrats and academics who didn’t comprehend the challenge we continued to face in communicating the message of freedom with people around the world.

An intellectual, not a bad one, even wrote a book proclaiming “The End of History.” [9] Imagine that.

I always reminded my colleagues at Heritage the opposite—that in Washington there are no permanent victories or permanent defeats, and we must remain ever watchful as we engage in what is permanent: the permanent battle for freedom. So, no, history did not end, and we are still struggling with freedom in the world.

Cold War Today

This brings us to the present. A fundamental reminder to all of America’s friends here and elsewhere:

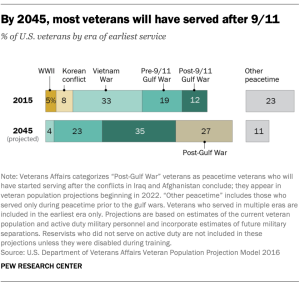

9/11/01 changed everything.

Our slow and unsteady progress in working with our Central European friends was pushed aside—as were all other foreign (and most domestic) policy considerations while we came face-to-face with a new enemy.

Remember, in the United States, by the accident of history or geography we are not accustomed to lengthy wars, such as the seventeenth-century Thirty Years’ War in Central Europe. Even today we are still dealing with the after-effects of 9/11, some eighteen years later, with American and allied troops deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq.

This is not an excuse, but rather it is an explanation for what some might call the less than robust response from the United States.

This was reinforced with contradictory decisions by successive U.S. administrations. For example, the Bush administration worked with the Czech and Hungarian governments to deploy U.S. facilities for the Strategic Defense Initiative on their soil. These governments met unfavorable public responses to their proposed cooperation, but they decided to cooperate with the United States. Then Barack Obama was elected president, and he revoked these agreements, to the distress of our host governments in Central Europe.

Then President Obama was succeeded by Donald Trump in 2017. Trump advocated a new form of “America First Nationalism,” which is bringing new challenges to America’s relationship with our friends in Central Europe. As Trump focuses on questions like burden sharing within NATO, he also encourages our allies to cooperate in shared endeavors such as the Middle East.

We watched the twentieth-century version of communism crumble and fall, but the fight against Marxist ideas is far from over.

Santayana’s dictum that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” comes to mind as we ponder the current state of political and philosophical debate in the United States.

We now find ourselves in the midst of another Cold War, similar, in many ways, to the conflict of years past. Only this time, the struggle is internal, and all the more fierce for it.

Instead of a physical takeover by communist-Soviet government forces, we are experiencing what Antonio Gramsci forecast: a “long march through the institutions,” a systematic takeover of the commanding heights of academia, of the entertainment industry, and of the media. This takeover of all of our culture-making institutions is promoting an alien, totalitarian system.

Instead of East and West, we are divided into socialism versus capitalism, government control versus individual freedom. We have seen the rise in popularity of left-wing politicians who speak in terms of class inequality and warfare and who express their support for growth of government power to rectify their concerns.

But perhaps more disturbing than the rhetoric of politicians is the brainwashing of the youth by our education systems into supporting this socialist rhetoric.

Students on college campuses have been indoctrinated into the Marxist cult, causing an alarming surge of support for big government among young people, who now look more favorably on socialist, collectivist policies and who support politicians who aggressively promote these ideas.

The younger American generation has largely forgotten—or never learned—the basics of the free society as outlined by academic leaders such as Friedrich von Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Hungary’s own Peter Bauer.

Fortunately, a new generation of true academic leaders, such as Stanford professor and Mont Pelerin Society president John Taylor, is teaching thousands of young people the basics of the free society. Taylor lists those principles as the rule of law, predictable policies from the government, reliance on market attention to incentives, and limitations on the size and scope of government. [10]

We find ourselves asking: How could the new generations want to live under a communist/socialist/Marxist regime?

The answer is: They don’t.

The problem is that the history of communism has been erased for this generation. New generations are being born and are being taught only the attractive points of the socialist ideology without learning about its inherent structural defects.

Something that our generation did not count on was that the new generations would not remember the Cold War. What to us is lived history is to them inconsequential, irrelevant, and unknown.

It is no wonder that they don’t see socialism as a threat to freedom. They didn’t live the history, they have not been taught it, and to top it all off, they are being educated on the wonders of Marxism from early primary school all the way through universities. They are being taught that socialism is a compassionate, moral system and that capitalism is the enemy.

Hope for the Future

I am one of Washington’s congenital optimists. Therefore, I do not believe that this is a hopeless cause. There are actions we can take to rectify this challenge, and it has much to do with messaging.

As conservative leaders, we must learn to communicate the message of the free market in terms of morality and transcendent standards. It is not enough to say that capitalism works. While we have been speaking in terms of efficiency, the left has been speaking in terms of morality. People are being taught that capitalism is immoral and corrupt, and that socialism is the more righteous system.

We can speak this language, too. And when we speak about it, we speak with real legitimacy. We should have never ceded this ground, and we must now reclaim it. We must emphasize not only why the free market is the most successful system but also why it is the most free and moral system.

People don’t just want to know that the system they benefit from is efficient; they also want to know that it is good.

If we can continue to explain to people that the free-market system allows for the most creativity, the most personal freedom, and the most opportunity for all people, and that it allows the individual and his family to enjoy nonmaterialist, spiritual rewards, then I believe we can stem the tide of socialist resurgence.

We must also continue to foster in our society an understanding of the principles and foundations of freedom and the histories that go along with them. Today’s young people must know about Venezuela, about North Korea, about Cuba, about China’s Great Leap Forward and their current repression of the Uyghurs in their own country, about the totalitarian history of the Soviet Union, and about the Berlin Wall.

And people need to know about the heroes of the struggle under communism—about Karol Wojtyła, about Vaclav Havel, about József Cardinal Mindszenty, and about so many others. We cannot allow these histories to be erased.

The fight for individual freedoms is a never-ending, eternal struggle. We all know this. It is what I and so many of us here have dedicated our lives to preserving and to advancing. It requires determination and steadfast optimism, but I’m hopeful for the future.

If we can keep history alive and begin to address modern-day socialism in moral terms, as Reagan did, then personal freedom will prove itself to be the most effective and moral way of living.

If we have learned anything from the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the communist regime thirty years ago, let it be this: there is hope for us today. If history has shown us anything, it is that tyranny has no place in a free society. It cannot stand under the will of a people unified and determined to be free.

Edwin J. Feulner is founder and former president of the Heritage Foundation. He has served on the Board of Trustees for the Intercollegiate Studies Institute for many years.

Image by Masami Ishikawa via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Eleanor Lansing Dulles, Berlin: The Wall Is Not Forever (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1967).

[2] G. Warren Nutter, The Growth of Industrial Production in the Soviet Union (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1962).

[3] Otto von Habsburg, “The Effects of Communism on Cultural and Psychological Politics in Eastern Europe,” Intercollegiate Review 3, no. 1 (September–October 1966), https://isi.org/intercollegiate-review/the-effects-of-communism-on-cultural-and-psychological-politics-in-eastern-europe/ .

[4] Ronald Reagan, An American Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 301.

[5] Henry A. Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994), 778.

[7] “Pan-European Picnic,” Wikipedia, accessed October 23, 2019.

[8] John O’Sullivan, The President, the Pope, and the Prime Minister (Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 2006).

[9] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992), based on his essay “The End of History,” 1989.

[10] John B. Taylor, First Principles: Five Keys to Restoring America’s Prosperity (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012).

Get the Collegiate Experience You Hunger For

Your time at college is too important to get a shallow education in which viewpoints are shut out and rigorous discussion is shut down.

Explore intellectual conservatism Join a vibrant community of students and scholars Defend your principles

Join the ISI community. Membership is free.

J.D. Vance on our Civilizational Crisis

J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....

In Memoriam: Gerald J. Russello (1971-2021)

Remembering a prominent ISI alumnus

In Memoriam: Angelo Codevilla (1943–2021)

Donate to the linda l. bean conference center.

Donate to renew America’s Roots

Berlin Wall’s Importance for Germany Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Reasons for berlin wall construction, berlin wall construction, effects of berlin wall, flattening of the wall.

The post Second World War was characterized by many political challenges in Europe. In Germany, the government struggled to consolidate its political power through various mechanisms.

In August 1961, “a fence was erected by the German Democratic Republic that is popularly referred to as East Germany” (Rose & Bailey 2004, p.34). The wall demarcated the West Berlin territory from East Germany. Watch towers were also erected strategically at various intervals along the wall with an aim of checking on illegal intrusion or exit from East Germany.

The Eastern Bloc contended that the barrier would save its masses from the fascist influence that was likely to jeopardize the development of socialism in the nation. Ideally, the wall was meant to suppress mass departure of citizens from East Germany after the Second World War. It was also meant to prevent the citizens from supporting fascist ideologies. This historic wall was formally known as the Anti-Fascist Defense Fortification.

Prior to the creation of the Berlin Wall, it is estimated that over three million citizens breached the stringent immigration codes and moved into Western Berlin territory (Tilman 1990, p. 78). From this place, they relocated to other Western European countries. These massive emigrations were proscribed in 1961 upon the creation of the Wall. The ban lasted until 1989 when the wall was flattened and it paved way for the reunification of Germany (Buckley 2004, p. 56).

After World War Two, the war torn Germany was split into four sub territories that were under the control of the Allied forces. The capital of Berlin that acted as the main operation zone of the Allied powers was also partitioned into four territories despite being situated within the Soviet territory.

After one and half years, political rivalries ensued between the occupying forces and the Soviets. One of the key disputes was the failure of the Soviets to accept the reconstruction strategies for revamping the economy and political stability of Germany. “Britain, France, the United States and the Benelux countries later combined the non-Soviet zones of the country into one zone for reconstruction and approved the extension of the Marshall Plan” (Waters 1990, p. 89).

In post 1945, Joseph Stalin governed an amalgamation of countries in the Western Border. He also desired to take control of the weakened Germany that was at that time under the management of the Soviet. Stalin, therefore, informed the leaders of Germany that he was planning to gradually destabilize the British occupation of German territories. According to Stalin, this was the most viable way to get rid of foreign powers and reunite Germany (Tusa 2008, p. 237).

The most important mission of the Leninist Party in the Soviet region was to direct Soviet instructions to both the government machinery and the other alliance parties. Leninist ideologies would eventually be exercised as internal procedures (Pearcy 2009, p.123). The teaching of Marxism ideologies was made mandatory in learning institutions (Morton & Adler 2010, p. 324).

From 1948, Stalin started reacting to the disagreements on how to rebuild the fallen Germany. In this case, he introduced the Berlin Cordon that debarred West Berlin from accessing necessary material supplies including food (Reeves 2011, p. 301). On the other hand, the Allied powers responded to Stalin’s actions by airlifting food and logistics to West Berlin.

The Soviets carried out public crusade in opposition to western strategy change. In late 1948, the members of the Communist Party tried to interfere with the food aids, but over three hundred Berliners picketed in demand for the continuation of the airlifts. Finally, Stalin withdrew the barricade in mid 1949; thus, allowing the hauling of supplies to Berlin (Miller 2008, p. 81).

West Germany embraced a capitalist economy and created a democratic legislative body. These political and economic reforms spurred quick economic growth in Western Germany. The robust economic growth that was witnessed in the western part of Germany attracted the people of Eastern Germany who were eying the better opportunities (Cherny 2009, p. 456).

In the 1950s, the Eastern Bloc also embraced the strategies that the Soviet applied to check on emigration. The restriction posed a great challenge to some countries that had gained economic prosperity in the Eastern Bloc. Before 1952, there was no limitation to frustrate movement of people from the Eastern Bloc to Western Germany.

This freedom of movement was curtailed in April 1952, when Eastern Germany officials held a meeting with Stalin (Soviet leader). “During the discussions, it was proposed that the East Germans should introduce a system of passes so as to stop the free movement of Western agents in the German Democratic Republic” (Childs 2001, p.156).

Stalin supported the idea and encouraged the Eastern Bloc to demarcate their territories by erecting a high rise wall. Therefore, the internal German boundary between East and West was totally cordoned with a fence. However, “the boundary between the Western and Eastern sectors of Berlin remained open, but traffic between the Soviet and Western sectors was somewhat restricted” (Harrison 2003, p.145).

Consequently, Berlin attracted immigrants that were fleeing the Eastern Bloc due to the unbearable living conditions. At first, East Germany would intermittently allow its citizens to visit the Western Bloc, but that freedom was short lived. In 1956, there was a total ban on emigration to West Germany after several citizens deserted East Germany.

The introduction of stringent immigration codes in 1952 led to the blockading of the interior Germany boundary. Therefore, East Germans used the Berlin border as the only gateway point to Western Germany. The German Democratic Republic acted very quickly to contain the exodus of its citizens by introducing more pass laws in late 1957. Individuals that were found crossing over to Berlin without authentic documentation were severely punished.

However, these emigration codes remained ineffective since people could still move to West Berlin by train. Besides, there were no physical barriers that could curb illegal movement of citizens out of East Germany. The Western Border was left open for some time to avoid disrupting connections to East Germany. The construction of an alternative railway that connected Western Berlin began in 1951 and ended in 1961. This led to the complete railing of the West Berlin boundary.

East German lost its industrious residents through massive emigrations; hence, it experienced a severe problem of brain drain. Most of the emigrants were in their formative years and were well trained in various disciplines. This meant that East Germany was left with no technocrats to spur industrial growth in the country.

On the other hand, West Germany gained considerably from the high supply of trained professionals which enabled it to improve its economy. “The brain drain of professionals had become so damaging to the political credibility and economic viability of East Germany that the re-securing of the German Communist frontier was imperative” (Dale 2005, p. 256).

“The East Germany officials authorized the construction of the wall on 12, August 1961 and the German military began securing it immediately” (Gaddis 2005, p. 312). The boundary was slightly erected within the land of East Berlin to avoid trespassing on the West Berlin soil.

During its construction, it was under strict surveillance of the German combat troops who were authorized to shoot any emigrant that made desperate efforts to escape. Additionally, “chain fences, walls, minefields and other obstacles were installed along the length of East Germany’s western borders with the West Germany proper” (Dowty 2009, p. 345).

An extensive no man’s territory was also created to facilitate shooting of fleeing individuals. However, some citizens still used dubious mechanisms to move to other territories. For example, “East Germans successfully defected by a variety of methods: digging long passageways under the wall, waiting for favorable winds and sliding along aerial wires” (Thackeray 2004, p. 52).

The creation of the Berlin Wall had serious implications on the lives of the Germans both in the Eastern and Western Blocs. After the construction of the fence, several individuals that had crossed over to the Western Bloc were completely detached from their families. Berliners that lived in the East, but worked in the West were all rendered jobless because they could not cross the border.

With the erection of the wall, West Berlin was separated; thus, West Berliners staged massive strikes in demand for the flattening of the wall. The Allied forces that had vested interests in post war Germany also encouraged the creation of the wall because they felt that it would thwart the ambitions of Eastern Germany to gain control of the entire Berlin. The wall, therefore, quelled the simmering tension in Germany Blocs which was likely to end in a serious military confrontation.

“The East German government claimed that the Berlin Wall was an anti-fascist protective rampart intended to dissuade aggression from the West” (Wettig 2008, p.189). Eastern German officials also complained that subsidized goods were being smuggled out of the country by West Berliners. The Wall caused extreme anxiety and repression in East Berlin because people were quarantined in their territories; thus, making it impossible for them to transact business.

West Berliners faced the most difficult challenge of gaining access to East German. Between 1961 and 1963, West Berliners were totally banned from entering the East German territory. However, negotiations between the two governments in 1963 led to slight revision of the immigration codes in East Germany.

Thus, West Berliners could visit the country intermittently. An Individual that wanted to travel to East Germany had to seek a visa. “Citizens of other East European countries were generally subjected to the same prohibition of visiting Western countries as East Germans, though the applicable exception varied from country to country” (Pearson 2008, p.318). During the ban, it is estimated that approximately 5,000 individuals desperately tried to jump over the fence and some of them lost their lives.

In late 1989, East Germans increasingly got disillusioned by emigration restrictions. Hence, they staged protests in various parts of East Germany in demand for the flattening of the wall. Most of the individuals that participated in the Peaceful Revolution were willing to defect to the Western Bloc.

The strike worsened in November when the majority of East Germans protested against the Wall. These demonstrations compelled the leaders of East Germany to amend the border laws. One of the amendments that were passed in the late 1989 favored the pulling down of the wall. The tearing down of the wall begun in late 1989, but its official flattening started on 13 th June 1990. However, “the West Germans and West Berliners were allowed visa-free travel starting from 23 December 1989” (Turner 2010, p. 456).

The destruction of the wall sparked-off mixed reactions from foreign powers. Some European countries became very jittery when they learnt that the Germans were planning to come together. In September 1989, “British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher pleaded with the Soviet president not to let the Berlin Wall fall” (Cate 2007, p. 178). Indeed, Britain was comfortable with the division and chaos in Germany because its reunion could cause the altering of the post war territorial demarcations.

They also felt that a unified Germany would destabilize international economy and possibly frustrate the post 1945 initiatives that were meant to restore international peace (Gaddis 2005, p. 249). The Germans saw the flattening of the wall as a great development that would guarantee them both economic and political prosperity which they had been yearning for over two decades.

Buckley, W 2004, The Fall of the Berlin Wall, Wiley, New York.

Cate, C 2007, The Ideas of August: The Berlin Wall Crisis—1961, M. Evans, New York.

Cherny, A 2009, The Candy Bombers: The Untold Story of the Berlin Airlift and America’s Finest Hour, Berkley Trade, Berkley.

Childs, D 2001, The Fall of the GDR, Longman, London.

Dale, G 2005, Popular Protest in East Germany, 1945–1989: Judgements on the Street, Routledge, Routledge.

Dowty, A 2009, Closed Borders: The Contemporary Assault on Freedom of Movement, Yale University Press, New York.

Gaddis, L 2005, The Cold War: A New History, Penguin Press, New York.

Harrison, M 2003, Driving the Soviets Up the Wall: Soviet-East German Relations, 1953–1961, Princenton University Press, New York.

Miller, R 2008, To Save a City: The Berlin Airlift, 1948-1949, Texas A&M University Press, Houston.

Morton, J & Adler, P 2010, American Experience: The Berlin Airlift, Wiley, New York.

Pearcy, A 2009, Berlin Airlift, Swan Hill Press, Berlin.

Pearson, R 2008, The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Empire, Wiley, Chicago.

Reeves, R 2011, Daring Young Men: The Heroism and Triumph of The Berlin Airlift-June 1948-May 1949, Simon & Schuster, Berlin.

Rose, B & Bailey, A 2004, The Lost Border: The Landscape of the Iron Curtain, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

Thackeray, F 2004, Events that changed Germany, Greenwood Publishing Group, London.

Tilman, T 1990, The Writings on the Wall: Peace at the Berlin Wall, Prenctice Hall, Ohio.

Turner, A 2010, The Two Germanies Since 1945: East and West, Yale University Press, New York.

Tusa, J 2008, Berlin Airlift, Da Capo Press, Berlin.

Waters, R 1990, Wall: Live in Berlin 1990, Oxford University Press, London.

Wettig, G 2008, Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, Berlin.

- The World Is Flat by Thomas Friedman: Changes in the Modern World

- The Public Speeches by Kennedy, Mac Arthur and King

- The Innovation Process: Successes and Failures

- The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815)

- Dahrendorf and Eley on the Rise of Nazism in Germany

- Origins and trajectory of the French Revolution

- A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present

- History of the Imperialism Era in 1848 to 1914

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, November 30). Berlin Wall's Importance for Germany. https://ivypanda.com/essays/berlin-wall/

"Berlin Wall's Importance for Germany." IvyPanda , 30 Nov. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/berlin-wall/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Berlin Wall's Importance for Germany'. 30 November.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Berlin Wall's Importance for Germany." November 30, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/berlin-wall/.

1. IvyPanda . "Berlin Wall's Importance for Germany." November 30, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/berlin-wall/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Berlin Wall's Importance for Germany." November 30, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/berlin-wall/.

The Rise and Fall of the Berlin Wall

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

A Divided Germany and Berlin

The economic differences.

- Mass Emigration From the East

What to Do About West Berlin

The berlin wall goes up, the size and scope of the berlin wall, the checkpoints of the wall, escape attempts and the death line, the 50th victim of the berlin wall, communism is dismantled, the fall of the berlin wall.

- B.A., History, University of California at Davis

Erected in the dead of night on August 13, 1961, the Berlin Wall (known as Berliner Mauer in German) was a physical division between West Berlin and East Germany. Its purpose was to keep disaffected East Germans from fleeing to the West.

When the Berlin Wall fell on November 9, 1989, its destruction was nearly as instantaneous as its creation. For 28 years, the Berlin Wall had been a symbol of the Cold War and the Iron Curtain between Soviet-led Communism and the democracies of the West. When it fell, the event was celebrated around the world.

At the end of World War II , the Allied powers divided conquered Germany into four zones. As agreed at the July 1945 Potsdam Conference , each was occupied by either the United States, Great Britain, France, or the Soviet Union . The same was done in Germany's capital city, Berlin.

The relationship between the Soviet Union and the other three Allied powers quickly disintegrated. As a result, the cooperative atmosphere of the occupation of Germany turned competitive and aggressive. One of the best-known incidents was the Berlin Blockade in June of 1948 during which the Soviet Union stopped all supplies from reaching West Berlin.

Although an eventual reunification of Germany had been intended, the new relationship between the Allied powers turned Germany into West versus East and democracy versus Communism .

In 1949, this new organization of Germany became official when the three zones occupied by the United States, Great Britain, and France combined to form West Germany (the Federal Republic of Germany, or FRG). The zone occupied by the Soviet Union quickly followed by forming East Germany (the German Democratic Republic, or GDR).

This same division into West and East occurred in Berlin. Since the city of Berlin had been situated entirely within the Soviet Zone of Occupation, West Berlin became an island of democracy within Communist East Germany.

Within a short period of time after the war, living conditions in West Germany and East Germany became distinctly different.

With the help and support of its occupying powers, West Germany set up a capitalist society . The economy experienced such a rapid growth that it became known as the "economic miracle." With hard work, individuals living in West Germany were able to live well, buy gadgets and appliances, and travel as they wished.

Nearly the opposite was true in East Germany. The Soviet Union had viewed their zone as a spoil of war. They pilfered factory equipment and other valuable assets from their zone and shipped them back to the Soviet Union.

When East Germany became its own country in 1949, it was under the direct influence of the Soviet Union and a Communist society was established. The economy of East Germany dragged and individual freedoms were severely restricted.

Mass Emigration From the East

Outside of Berlin, East Germany had been fortified in 1952. By the late 1950s, many people living in East Germany wanted out. No longer able to stand the repressive living conditions, they decided to head to West Berlin. Although some of them would be stopped on their way, hundreds of thousands made it across the border.

Once across, these refugees were housed in warehouses and then flown to West Germany. Many of those who escaped were young, trained professionals. By the early 1960s, East Germany was rapidly losing both its labor force and its population.

Scholars estimate that between 1949 and 1961, nearly 3 million of the GDR's 18 million populace fled East Germany. The government was desperate to stop this mass exodus, and the obvious leak was the easy access East Germans had to West Berlin.

With the support of the Soviet Union, there had been several attempts to simply take over the city of West Berlin. Although the Soviet Union even threatened the United States with the use of nuclear weapons over this issue, the United States and other Western countries were committed to defending West Berlin.

Desperate to keep its citizens, East Germany knew that something needed to be done. Famously, two months before the Berlin Wall appeared, Walter Ulbricht, Head of the State Council of the GDR (1960–1973) said, " Niemand hat die Absicht, eine Mauer zu errichten ." These iconic words mean, "No one intends to build a wall."

After this statement, the exodus of East Germans only increased. Over those next two months of 1961, nearly 20,000 people fled to the West.

Rumors had spread that something might happen to tighten the border of East and West Berlin. No one was expecting the speed—nor the absoluteness—of the Berlin Wall.

Just after midnight on the night of August 12–13, 1961, trucks with soldiers and construction workers rumbled through East Berlin. While most Berliners were sleeping, these crews began tearing up streets that entered into West Berlin. They dug holes to put up concrete posts and strung barbed wire all across the border between East and West Berlin. Telephone wires between East and West Berlin were also cut and railroad lines were blocked.

Berliners were shocked when they woke up that morning. What had once been a very fluid border was now rigid. No longer could East Berliners cross the border for operas, plays, soccer games, or any other activity. No longer could the approximately 50,000–70,000 commuters head to West Berlin for well-paying jobs. No longer could families, friends, and lovers cross the border to meet their loved ones.

Whichever side of the border one went to sleep on during the night of August 12, they were stuck on that side for decades.

The total length of the Berlin Wall was 96 miles (155 kilometers). It cut not only through the center of Berlin, but also wrapped around West Berlin, entirely cutting it off from the rest of East Germany.

The wall itself went through four major transformations during its 28-year history. It started out as a barbed-wire fence with concrete posts. Just days later, on August 15, it was quickly replaced with a sturdier, more permanent structure. This one was made out of concrete blocks and topped with barbed wire. The first two versions of the wall were replaced by the third version in 1965, consisting of a concrete wall supported by steel girders.

The fourth version of the Berlin Wall, constructed from 1975 to 1980, was the most complicated and thorough. It consisted of concrete slabs reaching nearly 12-feet high (3.6 meters) and 4-ft wide (1.2 m). It also had a smooth pipe running across the top to hinder people from scaling it.

By the time the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, there was a 300-foot No Man's Land established on the exterior, and an additional inner wall. Soldiers patrolled with dogs and a raked ground revealed any footprints. The East Germans also installed anti-vehicle trenches, electric fences, massive light systems, 302 watchtowers, 20 bunkers, and even minefields.

Over the years, propaganda from the East German government would say that the people of East Germany welcomed the Wall. In reality, the oppression they suffered and the potential consequences they faced kept many from speaking out to the contrary.

Although most of the border between East and West consisted of layers of preventative measures, there were little more than a handful of official openings along the Berlin Wall. These checkpoints were for the infrequent use of officials and others with special permission to cross the border.

The most famous of these was Checkpoint Charlie , located on the border between East and West Berlin at Friedrichstrasse. Checkpoint Charlie was the main access point for Allied personnel and Westerners to cross the border. Soon after the Berlin Wall was built, Checkpoint Charlie became an icon of the Cold War, one that has frequently been featured in movies and books set during this time period.

The Berlin Wall did prevent the majority of East Germans from emigrating to the West, but it did not deter everyone. During the history of the Berlin Wall, it is estimated that about 5,000 people made it safely across.

Some early successful attempts were simple, like throwing a rope over the Berlin Wall and climbing up. Others were brash, like ramming a truck or bus into the Berlin Wall and making a run for it. Still others were suicidal as some people jumped from the upper-story windows of apartment buildings that bordered the Berlin Wall.

In September 1961, the windows of these buildings were boarded up and the sewers connecting East and West were shut off. Other buildings were torn down to clear space for what would become known as the Todeslinie , the "Death Line" or "Death Strip." This open area allowed a direct line of fire so East German soldiers could carry out Shiessbefehl , a 1960 order that they were to shoot anyone trying escape. At least 12 were killed within the first year.

As the Berlin Wall became stronger and larger, escape attempts became more elaborately planned. Some people dug tunnels from the basements of buildings in East Berlin, under the Berlin Wall, and into West Berlin. Another group saved scraps of cloth and built a hot air balloon and flew over the Wall.

Unfortunately, not all escape attempts were successful. Since the East German guards were allowed to shoot anyone nearing the eastern side without warning, there was always a chance of death in any and all escape plots. At least 140 people died at the Berlin Wall.

One of the most infamous cases of a failed attempt occurred on August 17, 1962. In the early afternoon, two 18-year-old men ran toward the Wall with the intention of scaling it. The first of the young men to reach it was successful. The second one, Peter Fechter , was not.

As he was about to scale the Wall, a border guard opened fire. Fechter continued to climb but ran out of energy just as he reached the top. He then tumbled back onto the East German side. To the shock of the world, Fechter was just left there. The East German guards did not shoot him again nor did they go to his aid.

Fechter shouted in agony for nearly an hour. Once he had bled to death, East German guards carried off his body. He became a permanent symbol of the struggle for freedom.

The fall of the Berlin Wall happened nearly as suddenly as its rise. There had been signs that the Communist bloc was weakening, but the East German Communist leaders insisted that East Germany just needed a moderate change rather than a drastic revolution. East German citizens did not agree.

Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev (1985–1991) was attempting to save his country and decided to break off from many of its satellites. As Communism began to falter in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia in 1988 and 1989, new exodus points were opened to East Germans who wanted to flee to the West.

In East Germany, protests against the government were countered by threats of violence from its leader, Erich Honecker (served 1971–1989). In October 1989, Honecker was forced to resign after losing support from Gorbachev. He was replaced by Egon Krenz who decided that violence was not going to solve the country's problems. Krenz also loosened travel restrictions from East Germany.

Suddenly, on the evening of November 9, 1989, East German government official Günter Schabowski blundered by stating in an announcement, "Permanent relocations can be done through all border checkpoints between the GDR [East Germany] into the FRG [West Germany] or West Berlin."

People were in shock. Were the borders really open? East Germans tentatively approached the border and indeed found that the border guards were letting people cross.

Very quickly, the Berlin Wall was inundated with people from both sides. Some began chipping at the Berlin Wall with hammers and chisels. There was an impromptu and massive celebration along the Berlin Wall, with people hugging, kissing, singing, cheering, and crying.

The Berlin Wall was eventually chipped away into smaller pieces (some the size of a coin and others in big slabs). The pieces have become collectibles and are stored in both homes and museums. There is also now a Berlin Wall Memorial at the site on Bernauer Strasse.

After the Berlin Wall came down, East and West Germany reunified into a single German state on October 3, 1990.

Harrison, Hope M. Driving the Soviets up the Wall: Soviet-East German Relations, 1953-1961 . Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Major, Patrick. “ Walled In: Ordinary East Germans' Responses to 13 August 1961 .” German Politics & Society, vol. 29, no. 2, 2011, pp. 8–22.

Friedman, Peter. " I was a Reverse Commuter Across the Berlin Wall ." The Wall Street Journal , 8 Nov. 2019.

" Berlin Wall: Facts & Figures ." National Cold War Exhibition , Royal Air Force Museum.

Rottman, Gordon L. The Berlin Wall and the Intra-German Border 1961–89 . Bloomsbury, 2012.

" The Wall ." Mauer Museum: Haus am Checkpoint Charlie.

Hertle, Hans-Hermann and Maria Nooke (eds.). The Victims at the Berlin Wall, 1961–1989. A Biographical Handbook . Berlin: Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam and Stiftung Berliner Mauer, Aug. 2017.

- Cold War Timeline

- The Cold War in Europe

- Germany's Capital Moves From Bonn to Berlin

- Ostpolitik: West Germany Talks to the East

- Geography of Germany

- The Downfall of Communism

- Why Did the Soviet Union Collapse?

- These 4 Quotes Completely Changed the History of the World

- Berlin Airlift and Blockade in the Cold War

- The Postwar World After World War II

- Origins of the Cold War in Europe

- The History of Containment Policy

- The Warsaw Pact History and Members

- Sigmar Polke, German Pop Artist and Photographer

- World War II: Battle of Berlin

- Cold War Glossary

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Fall of the Berlin Wall in Photos: An Accident of History That Changed The World

The Communist regime was prepared for everything “except candles and prayers.” East Germany’s peaceful 1989 revolution showed that societies that don’t reform, die.

By Katrin Bennhold

BERLIN — When Werner Krätschell, an East German pastor and dissident, heard that the Berlin Wall was open, he did not quite believe it. But he grabbed his daughter and her friend and drove to the nearest checkpoint to see for himself.

It was the night of Nov. 9, 1989. As their yellow Wartburg advanced unimpeded into what had always been an off-limits security zone, Mr. Krätschell rolled down the window and asked a border guard: “Am I dreaming or is this reality?”

“You are dreaming,” the guard replied.

It had long been a dream for East Berliners like Mr. Krätschell to see this towering symbol of unfreedom running like a scar of cement and barbed wire through the heart of their home city ripped open.

And when it finally became reality, when the Cold War’s most notorious armed border opened overnight, and was torn apart in the days that followed, it was not in the end the result of some carefully crafted geopolitical grand bargain.

It was, at the most basic level at least, the wondrous result of human error, spontaneity and individual courage.

“It was not predestined,” said Anne Applebaum, the historian and columnist. “It was not a triumph of good over evil. It was basically incompetence — and chance.”

In the early evening of that fateful November day, a news conference took a historic turn.

Against the backdrop of mass protests and a wave of eastern German refugees that had already fled the country via Hungary and what was then Czechoslovakia, Günter Schabowski, the leader of the East Berlin Communist Party, convened journalists to announce a series of reforms to ease travel restrictions.

When asked when the new rules would take effect, Mr. Schabowski paused and studied the notes before him with a furrowed brow. Then he stumbled through a partially intelligible answer, declaring, “It takes effect, as far as I know... it is now... immediately.”

It was a mistake. The Politburo had planned nothing of the sort. The idea had been to appease the growing resistance movement with minor adjustments to visa rules — and also to retain the power to deny travel.

But many took Mr. Schabowski by his word. After West Germany’s main evening news, popular with East Germans who had long stopped trusting their own state-controlled media, effectively declared the wall open, crowds started heading for checkpoints at the Berlin Wall, demanding to cross.

At one of those checkpoints, a Stasi officer who had always been loyal to the regime, was working the night shift. His name was Lt. Col. Harald Jäger. And his order was to turn people away.

As the crowd grew, the colonel repeatedly called his superiors with updates. But no new orders were forthcoming. At some point he listened in to a call with the ministry, where he overheard one senior official questioning his judgment.

“Someone in the ministry asked whether Comrade Jäger was in a position to assess the situation properly or whether he was acting out of fear,” Mr. Jäger recalled years later in an interview with Der Spiegel . “When I heard that, I’d had enough.”

“If you don’t believe me, then just listen!” he shouted down the line, then took the receiver and held it out the window.

Shortly after, Mr. Jäger defied his superiors and opened the crossing, starting a domino effect that eventually hit all checkpoints in Berlin. By midnight, triumphant easterners had climbed on top of the wall in the heart of the city, popping champagne corks and setting off fireworks in celebration.

Not a single shot was fired. And no Soviet tanks appeared.

That, said Axel Klausmeier, director of the Berlin Wall Foundation, was perhaps the greatest miracle of that night. “It was a peaceful revolution, the first of its kind,” he said. “They were prepared for everything, except candles and prayers.”

Through its history more than 140 people had died at the Berlin Wall, the vast majority of them trying to escape.

There was Ida Siekmann, 58, who became the first victim on Aug. 22, 1961, just nine days after the wall was finished. She died jumping from her third-floor window after the front of her house on Bernauer Strasse had become became part of the border, the front door filled in with bricks.

Peter Fechter, 18, became the most famous victim a year later. Shot several times in the back as he scaled the wall, he fell back onto the eastern side where he lay for over an hour, shouting for help and bleeding to death, as eastern guards looked on and western cameras whirled.

The youngest victim was 15-month-old Holger H., who suffocated when his mother tried to quiet him while the truck his family was hiding in was being searched on Jan. 22, 1971. The parents made it across before realizing that their baby was dead.

For the first half of 1989, it was still nearly impossible to get out of East Germany: The last killing at the wall took place in February that year, the last shooting, a close miss, in April.

The Soviets had squashed an East German uprising in June 1953 and suppressed similar rebellions in Hungary in 1956 and Prague in 1968 .

In June 1989, just five months before the Berlin Wall fell, the Communist Party of China committed a massacre against democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square.

“They had been shooting people for 40 years,” said Ms. Applebaum, the historian. “No one knew what they would do in 1989.”

But 1989 proved different. In the end, what gave people courage to resist were a series of shocks that had already shaken Soviet Communism to the core.

Poland’s successful Solidarity movement, which had culminated in a semi-free election that year, was one. Others included a series of social and political reforms across Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe with which the Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev hoped to preserve — not end — his Communist Party’s control.

And perhaps most important, Ms. Applebaum said, belief in the system had long evaporated.

“The ideology had collapsed and people just didn’t believe in it anymore,” she said.

That is how the little things that culminated in this historic moment could become big things, said Timothy Garton Ash, professor of European history at Oxford University. But that is sometimes misunderstood.

“We took one of the most non-linear events and turned it into a linear version of history,” said Mr. Garton Ash.

The fall of the Berlin Wall became the end of history and liberalism the unchallenged model of modernity. Now illiberalism, Chinese-style, is challenging the West.

Complacency is dangerous, said Ms. Applebaum: “The lesson is: Societies that don’t reform, die.”

Mr. Krätschell, the pastor, had been among those demanding reforms and protesting the system with peaceful means. He held dissident meetings in his home and was harassed by the Stasi, East Germany’s fearsome secret police, for years. The churches played an important role in the resistance movement against East Germany’s Communist authorities.

“We knew: All the phone calls were bugged,” said Mr. Krätschell, now 79.

Years later, after reading his own Stasi file, he learned that special commandos had bugged his home, updating the technology whenever he was on holiday with his family.

Soon after Mr. Krätschell, the pastor, had driven across the border on Nov. 9, 1989, a friend of his daughter who was also in the car asked him to pull over. She was 21 and pregnant and had never set foot in the West before.

Once Mr. Krätschell had parked, she opened the door, stuck her leg out, and touched the floor with her foot. Then she smiled triumphantly.

“It was like the moon landing,” recalled Mr. Krätschell, “a kind of Neil Armstrong moment.”

Later, back in the East, she had called her parents and said, “Guess what, I was in the West.”

Christopher F. Schuetze contributed reporting.

Produced by Gaia Tripoli.

An earlier version of a picture caption misstated the positions of the territories shown on either side to the Berlin Wall. East Berlin is on the right, and West Berlin on the left.

How we handle corrections

Katrin Bennhold is The New York Times's Berlin bureau chief. Previously she reported from London and Paris, covering a range of topics from the rise of populism to gender. More about Katrin Bennhold

The Berlin Wall

Thierry Noir and The Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall is perhaps the most famous human artefact in modern world history. Built in 1961 at the height of the Cold War, the Wall symbolised in physical form the ideological and political divide between the Western Bloc and the USSR. 15 years after Winston Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech in Fulton, Missouri, a monolithic and impenetrable barrier that cut across Europe became a reality, situating the city of Berlin at the fulcrum of Cold War antagonisms.