Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 11: Presenting Your Research

American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning Objectives

- Define APA style and list several of its most important characteristics.

- Identify three levels of APA style and give examples of each.

- Identify multiple sources of information about APA style.

What Is APA Style?

APA style is a set of guidelines for writing in psychology and related fields. These guidelines are set down in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2006) [1] . The Publication Manual originated in 1929 as a short journal article that provided basic standards for preparing manuscripts to be submitted for publication (Bentley et al., 1929) [2] . It was later expanded and published as a book by the association and is now in its seventh edition ( view the APA Style website online ). The primary purpose of APA style is to facilitate scientific communication by promoting clarity of expression and by standardizing the organization and content of research articles and book chapters. It is easier to write about research when you know what information to present, the order in which to present it, and even the style in which to present it. Likewise, it is easier to read about research when it is presented in familiar and expected ways.

APA style is best thought of as a “genre” of writing that is appropriate for presenting the results of psychological research—especially in academic and professional contexts. It is not synonymous with “good writing” in general. You would not write a literary analysis for an English class, even if it were based on psychoanalytic concepts, in APA style. You would write it in Modern Language Association (MLA) style instead. And you would not write a newspaper article, even if it were about a new breakthrough in behavioural neuroscience, in APA style. You would write it in Associated Press (AP) style instead. At the same time, you would not write an empirical research report in MLA style, in AP style, or in the style of a romance novel, an e-mail to a friend, or a shopping list. You would write it in APA style. Part of being a good writer in general is adopting a style that is appropriate to the writing task at hand, and for writing about psychological research, this is APA style.

The Levels of APA Style

Because APA style consists of a large number and variety of guidelines—the Publication Manual is nearly 300 pages long—it can be useful to think about it in terms of three basic levels. The first is the overall organization of an article (which is covered in Chapter 2 “Manuscript Structure and Content” of the Publication Manual ). Empirical research reports, in particular, have several distinct sections that always appear in the same order:

- Title page. Presents the article title and author names and affiliations.

- Abstract. Summarizes the research.

- Introduction. Describes previous research and the rationale for the current study.

- Method. Describes how the study was conducted.

- Results. Describes the results of the study.

- Discussion. Summarizes the study and discusses its implications.

- References. Lists the references cited throughout the article.

The second level of APA style can be referred to as high-level style (covered in Chapter 3 “Writing Clearly and Concisely” of the Publication Manual ), which includes guidelines for the clear expression of ideas. There are two important themes here. One is that APA-style writing is formal rather than informal. It adopts a tone that is appropriate for communicating with professional colleagues—other researchers and practitioners—who share an interest in the topic. Beyond this shared interest, however, these colleagues are not necessarily similar to the writer or to each other. A graduate student in British Columbia might be writing an article that will be read by a young psychotherapist in Toronto and a respected professor of psychology in Tokyo. Thus formal writing avoids slang, contractions, pop culture references, humour, and other elements that would be acceptable in talking with a friend or in writing informally.

The second theme of high-level APA style is that it is straightforward. This means that it communicates ideas as simply and clearly as possible, putting the focus on the ideas themselves and not on how they are communicated. Thus APA-style writing minimizes literary devices such as metaphor, imagery, irony, suspense, and so on. Again, humour is kept to a minimum. Sentences are short and direct. Technical terms must be used, but they are used to improve communication, not simply to make the writing sound more “scientific.” For example, if participants immersed their hands in a bucket of ice water, it is better just to write this than to write that they “were subjected to a pain-inducement apparatus.” At the same time, however, there is no better way to communicate that a between-subjects design was used than to use the term “between-subjects design.”

APA Style and the Values of Psychology

Robert Madigan and his colleagues have argued that APA style has a purpose that often goes unrecognized (Madigan, Johnson, & Linton, 1995) [3] . Specifically, it promotes psychologists’ scientific values and assumptions. From this perspective, many features of APA style that at first seem arbitrary actually make good sense. Following are several features of APA-style writing and the scientific values or assumptions they reflect.

| There are very few direct quotations of other researchers. | The phenomena and theories of psychology are objective and do not depend on the specific words a particular researcher used to describe them. |

| Criticisms are directed at other researchers’ work but not at them personally. | The focus of scientific research is on drawing general conclusions about the world, not on the personalities of particular researchers. |

| There are many references and reference citations. | Scientific research is a large-scale collaboration among many researchers. |

| Empirical research reports are organized with specific sections in a fixed order. | There is an ideal approach to conducting empirical research in psychology (even if this ideal is not always achieved in actual research). |

| Researchers tend to “hedge” their conclusions, e.g., “The results that…” | Scientific knowledge is tentative and always subject to revision based on new empirical results. |

Another important element of high-level APA style is the avoidance of language that is biased against particular groups. This is not only to avoid offending people—why would you want to offend people who are interested in your work?—but also for the sake of scientific objectivity and accuracy. For example, the term sexual orientation should be used instead of sexual preference because people do not generally experience their orientation as a “preference,” nor is it as easily changeable as this term suggests (APA Committee on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Concerns Joint Task Force on Guidelines for Psychotherapy With Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients, 2000) [4] .

The general principles for avoiding biased language are fairly simple. First, be sensitive to labels by avoiding terms that are offensive or have negative connotations. This includes terms that identify people with a disorder or other problem they happen to have. For example, patients with schizophrenia is better than schizophrenics . Second, use more specific terms rather than more general ones. For example, Chinese Canadians is better than Asian Canadians if everyone in the group is, in fact, Chinese Canadian. Third, avoid objectifying research participants. Instead, acknowledge their active contribution to the research. For example, “The students completed the questionnaire” is better than “The subjects were administered the questionnaire.” Note that this principle also makes for clearer, more engaging writing. Table 11.1 shows several more examples that follow these general principles.

| man, men | men and women, people |

| firemen | firefighters |

| homosexuals, gays, bisexuals | lesbians, gay men, bisexual men, bisexual women |

| minority | specific group label (e.g., African American) |

| neurotics | people scoring high in neuroticism |

| special children | children with learning disabilities |

The previous edition of the Publication Manual strongly discouraged the use of the term subjects (except for nonhumans) and strongly encouraged the use of participants instead. The current edition, however, acknowledges that subjects can still be appropriate in referring to human participants in areas in which it has traditionally been used (e.g., basic memory research). But it also encourages the use of more specific terms when possible: university students , children , respondents , and so on.

The third level of APA style can be referred to as low-level style (which is covered in Chapter 4 “The Mechanics of Style” through Chapter 7 “Reference Examples” of the Publication Manual .) Low-level style includes all the specific guidelines pertaining to spelling, grammar, references and reference citations, numbers and statistics, figures and tables, and so on. There are so many low-level guidelines that even experienced professionals need to consult the Publication Manual from time to time. Table 11.2 contains some of the most common types of APA style errors based on an analysis of manuscripts submitted to one professional journal over a 6-year period (Onwuegbuzie, Combs, Slate, & Frels, 2010) [5] . These errors were committed by professional researchers but are probably similar to those that students commit the most too. See also Note 11.8 “Online APA Style Resources” in this section and, of course, the Publication Manual itself.

| 1. Use of numbers | Failing to use numerals for 10 and above |

| 2. Hyphenation | Failing to hyphenate compound adjectives that precede a noun (e.g., “role playing technique” should be “role-playing technique”) |

| 3. Use of | Failing to use it after a reference is cited for the first time |

| 4. Headings | Not capitalizing headings correctly |

| 5. Use of | Using to mean |

| 6. Tables and figures | Not formatting them in APA style; repeating information that is already given in the text |

| 7. Use of commas | Failing to use a comma before or in a series of three or more elements |

| 8. Use of abbreviations | Failing to spell out a term completely before introducing an abbreviation for it |

| 9. Spacing | Not consistently double-spacing between lines |

| 10. Use of “&” in references | Using in the text or in parentheses |

Online APA Style Resources

The best source of information on APA style is the Publication Manual itself. However, there are also many good websites on APA style, which do an excellent job of presenting the basics for beginning researchers. Here are a few of them.

Purdue Online Writing Lab

Douglas Degelman’s APA Style Essentials [PDF]

Doc Scribe’s APA Style Lite [PDF]

APA-Style References and Citations

Because science is a large-scale collaboration among researchers, references to the work of other researchers are extremely important. Their importance is reflected in the extensive and detailed set of rules for formatting and using them.

At the end of an APA-style article or book chapter is a list that contains references to all the works cited in the text (and only the works cited in the text). The reference list begins on its own page, with the heading “References,” centred in upper and lower case. The references themselves are then listed alphabetically according to the last names of the first named author for each citation. (As in the rest of an APA-style manuscript, everything is double-spaced.) Many different kinds of works might be cited in APA-style articles and book chapters, including magazine articles, websites, government documents, and even television shows. Of course, you should consult the Publication Manual or Online APA Style Resources for details on how to format them. Here we will focus on formatting references for the three most common kinds of works cited in APA style: journal articles, books, and book chapters.

Journal Articles

For journal articles, the generic format for a reference is as follows:

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Title of article. Title of Journal, xx (yy), pp–pp. doi:xx.xxxxxxxxxx

Here is a concrete example:

Adair, J. G., & Vohra, N. (2003). The explosion of knowledge, references, and citations: Psychology’s unique response to a crisis. American Psychologist, 58 (1), 15–23. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.15

There are several things to notice here. The reference includes a hanging indent. That is, the first line of the reference is not indented but all subsequent lines are. The authors’ names appear in the same order as on the article, which reflects the authors’ relative contributions to the research. Only the authors’ last names and initials appear, and the names are separated by commas with an ampersand (&) between the last two. This is true even when there are only two authors. Only the first word of the article title is capitalized. The only exceptions are for words that are proper nouns or adjectives (e.g., “Freudian”) or if there is a subtitle, in which case the first word of the subtitle is also capitalized. In the journal title, however, all the important words are capitalized. The journal title and volume number are italicized; however, the issue number (listed within parentheses) is not. At the very end of the reference is the digital object identifier (DOI), which provides a permanent link to the location of the article on the Internet. Include this if it is available. It can generally be found in the record for the item on an electronic database (e.g., PsycINFO) and is usually displayed on the first page of the published article.

For a book, the generic format and a concrete example are as follows:

Author, A. A. (year). Title of book . Location: Publisher. Kashdan, T., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2014). The upside of your dark side. New York, NY: Hudson Street Press.

Book Chapters

For a chapter in an edited book, the generic format and a concrete example are as follows:

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Title of chapter. In A. A. Editor, B. B. Editor, & C. C. Editor (Eds.), Title of book (pp. xxx–xxx). Location: Publisher. Lilienfeld, S. O., & Lynn, S. J. (2003). Dissociative identity disorder: Multiple personalities, multiple controversies. In S. O. Lilienfeld, S. J. Lynn, & J. M. Lohr (Eds.), Science and pseudoscience in clinical psychology (pp. 109–142). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Notice that references for books and book chapters are similar to those for journal articles, but there are several differences too. For an edited book, the names of the editors appear with their first and middle initials followed by their last names (not the other way around)—with the abbreviation “Eds.” (or “Ed.,” if there is only one) appearing in parentheses immediately after the final editor’s name. Only the first word of a book title is capitalized (with the exceptions noted for article titles), and the entire title is italicized. For a chapter in an edited book, the page numbers of the chapter appear in parentheses after the book title with the abbreviation “pp.” Finally, both formats end with the location of publication and the publisher, separated by a colon.

Reference Citations

When you refer to another researcher’s idea, you must include a reference citation (in the text) to the work in which that idea originally appeared and a full reference to that work in the reference list. What counts as an idea that must be cited? In general, this includes phenomena discovered by other researchers, theories they have developed, hypotheses they have derived, and specific methods they have used (e.g., specific questionnaires or stimulus materials). Citations should also appear for factual information that is not common knowledge so that other researchers can check that information for themselves. For example, in an article on the effect of cell phone usage on driving ability, the writer might cite official statistics on the number of cell phone–related accidents that occur each year. Among the ideas that do not need citations are widely shared methodological and statistical concepts (e.g., between-subjects design, t test) and statements that are so broad that they would be difficult for anyone to argue with (e.g., “Working memory plays a role in many daily activities.”). Be careful, though, because “common knowledge” about human behaviour is often incorrect. Therefore, when in doubt, find an appropriate reference to cite or remove the questionable assertion.

When you cite a work in the text of your manuscript, there are two ways to do it. Both include only the last names of the authors and the year of publication. The first method is to use the authors’ last names in the sentence (with no first names or initials) followed immediately by the year of publication in parentheses. Here are some examples:

Burger (2008) conducted a replication of Milgram’s (1963) original obedience study.

Although many people believe that women are more talkative than men, Mehl, Vazire, Ramirez-Esparza, Slatcher, and Pennebaker (2007) found essentially no difference in the number of words spoken by male and female college students.

Notice several things. First, the authors’ names are treated grammatically as names of people, not as things. It is better to write “a replication of Milgram’s (1963) study” than “a replication of Milgram (1963).” Second, when there are two authors the names are not separated by commas, but when there are three or more authors they are. Third, the word and (rather than an ampersand) is used to join the authors’ names. Fourth, the year follows immediately after the final author’s name. An additional point, which is not illustrated in these examples but is illustrated in the sample paper in Section 11.2 “Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style”, is that the year only needs to be included the first time a particular work is cited in the same paragraph.

The second way to cite an article or a book chapter is parenthetically—including the authors’ last names and the year of publication in parentheses following the idea that is being credited. Here are some examples:

People can be surprisingly obedient to authority figures (Burger, 2008; Milgram, 1963).

Recent evidence suggests that men and women are similarly talkative (Mehl, Vazire, Ramirez-Esparza, Slatcher, & Pennebaker, 2007).

One thing to notice about such parenthetical citations is that they are often placed at the end of the sentence, which minimizes their disruption to the flow of that sentence. In contrast to the first way of citing a work, this way always includes the year—even when the citation is given multiple times in the same paragraph. Notice also that when there are multiple citations in the same set of parentheses, they are organized alphabetically by the name of the first author and separated by semicolons.

There are no strict rules for deciding which of the two citation styles to use. Most articles and book chapters contain a mixture of the two. In general, however, the first approach works well when you want to emphasize the person who conducted the research—for example, if you were comparing the theories of two prominent researchers. It also works well when you are describing a particular study in detail. The second approach works well when you are discussing a general idea and especially when you want to include multiple citations for the same idea.

The third most common error in Table 11.2 has to do with the use of et al. This is an abbreviation for the Latin term et alia , which means “and others.” In APA style, if an article or a book chapter has more than two authors , you should include all their names when you first cite that work. After that, however, you should use the first author’s name followed by “et al.” Here are some examples:

Recall that Mehl et al. (2007) found that women and men spoke about the same number of words per day on average.

There is a strong positive correlation between the number of daily hassles and the number of symptoms people experience (Kanner et al., 1981).

Notice that there is no comma between the first author’s name and “et al.” Notice also that there is no period after “et” but there is one after “al.” This is because “et” is a complete word and “al.” is an abbreviation for the word alia .

Key Takeaways

- APA style is a set of guidelines for writing in psychology. It is the genre of writing that psychologists use to communicate about their research with other researchers and practitioners.

- APA style can be seen as having three levels. There is the organization of a research article, the high-level style that includes writing in a formal and straightforward way, and the low-level style that consists of many specific rules of grammar, spelling, formatting of references, and so on.

- References and reference citations are an important part of APA style. There are specific rules for formatting references and for citing them in the text of an article.

- Practice: Find a description of a research study in a popular magazine, newspaper, blog, or website. Then identify five specific differences between how that description is written and how it would be written in APA style.

- Walters, F. T., and DeLeon, M. (2010). Relationship Between Intrinsic Motivation and Accuracy of Academic Self-Evaluations Among High School Students. Educational Psychology Quarterly, 23, 234–256.

- Moore, Lilia S. (2007). Ethics in survey research. In M. Williams & P. L. Lee (eds.), Ethical Issues in Psychology (pp. 120–156), Boston, Psychological Research Press.

- Vang, C., Dumont, L. S., and Prescott, M. P. found that left-handed people have a stronger preference for abstract art than right-handed people (2006).

- This result has been replicated several times (Williamson, 1998; Pentecost & Garcia, 2006; Armbruster, 2011)

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (2010). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Bentley, M., Peerenboom, C. A., Hodge, F. W., Passano, E. B., Warren, H. C., & Washburn, M. F. (1929). Instructions in regard to preparation of manuscript. Psychological Bulletin, 26 , 57–63. ↵

- Madigan, R., Johnson, S., & Linton, P. (1995). The language of psychology: APA style as epistemology. American Psychologist, 50 , 428–436. ↵

- American Psychological Association, Committee on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Concerns Joint Task Force on Guidelines for Psychotherapy With Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients. (2000). Guidelines for psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients . Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20081022063811/http://www.apa.org:80/pi/lgbc/guidelines.html ↵

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Combs, J. P., Slate, J. R., & Frels, R. K. (2010). Editorial: Evidence-based guidelines for avoiding the most common APA errors in journal article submissions. Research in the Schools, 16 , ix–xxxvi. ↵

A set of guidelines for writing in psychology and related fields.

A book produced by the APA containing standards for preparing manuscripts to be submitted for publication in order to facilitate scientific communication by promoting clarity of expression and standardizing the organization and content of articles and book chapters.

Referring to an article, the sections that are included and what order they appear in.

The second level of APA style which includes guidelines for the clear expression of ideas through writing style.

Third level of APA style which includes all the specific guidelines pertaining to spelling, grammar, references and reference citations, numbers and statistic, figures and tables, and so on.

The source of information used in a research article.

The referral to another researcher’s idea that is written in the text, with the full reference appearing in the reference list.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Belk Library

Psychology Research Guide

- What are Empirical Articles?

- Developing a Topic

- Finding Sources

- Searching Effectively

- Scholarly and Popular Sources

- Additional Help

Citation Resources

The most often used citation style for Psychology is:

DOIs and URLs

Follow these instructions from the American Psychological Association to correctly include DOIs and URLs in your list of references.

DOIs & URLs in APA Style

What are empirical articles?

In psychology, empirical research articles are peer-reviewed and report on new research that answers one or more specific questions. Empirical research is based on measurable observation and experimentation. When reading an empirical article, think about what research question is being asked or what experiment is being conducted.

How are they organized?

Empirical research articles in psychology typically follow APA style guidelines. They are organized into the following major sections:

- Abstract (An abstract provides a summary of the study.)

- Introduction (This section includes a literature review.)

- Method (How was the experiment or study conducted?)

- Results (What are the findings?)

- Discussion (What did the researchers conclude? What are the implications of the research?)

How should I read an empirical article?

Because empirical research articles follow a particular format, you can dip into the article at multiple points and move around in a non-linear way. First, think about why you're reading the article. Are you looking for specific information or trying to get research ideas? Are you reading it for a course or for your own knowledge? Next, read the abstract to get an overview of the study. Skim the first and last paragraphs of the introduction and results to deepen your understanding of the article as a whole. Read the methods section to understand how the study was organized and conducted. Review the charts, graphs, and statistics to understand the analyses. Skim the remaining pieces of the article, before going back and reading it more closely from the beginning to the end. Don't forget that the references can be a great source for additional empirical articles.

Don't confuse empirical articles with other types of articles.

Be careful not to confuse an empirical article with other types of articles that you might find when researching a psychology topic. Meta-analyis, systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and other types of literature reviews are not empirical articles. Instead, these articles are designed to analyze and summarize the existing literature on a topic. Similarly, don't confuse book reviews with empirical articles. These types of articles might be helpful in your research, but they are not empirical research articles.

- << Previous: Developing a Topic

- Next: Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 1:11 PM

- URL: https://elon.libguides.com/Psychology

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

APA Formatting and Style Guide (7th Edition)

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

In-Text Citations

Resources on using in-text citations in APA style

Reference List

Resources on writing an APA style reference list, including citation formats

Other APA Resources

EDPS 260: Find and use empirical research articles

- About this guide

- Video: Find a peer-reviewed empirical research article

- Step 1: Use the best databases for your topic

- Step 2: Search for your topic

- Step 3: Find the full text

- Step 4: Confirm that the source is an empirical article

- Step 5: Confirm that the source is a peer reviewed article

- Get your URLs!

APA Citation Style

- Extended Online APA Citation Guide Online guide created by Ball State University Libraries giving detailed example citations for a wide variety of source types including modern media like Tweets, YouTube, etc.

- APA Citation Style Guide handout from the BSU Libraries This handout created by Ball State University Libraries will walk you through creating citations for sources in APA style.

- Purdue OWL: APA Format and Style Guide For instruction and examples of in-text and Reference List citations, see this website from the Purdue OWL. Also includes example APA papers.

- APA Style Blog Do you ever have sources that you are not sure how to document and can't seem to find the details in APA style guides? If so, check out the APA Style Blog. The entries cover trickier aspects of APA Style and the blog is searchable using the Google custom search box in the upper right corner.

- The Writing Center Need one-on-one help with writing your citations? Contact the Writing Center.

APA Style: In-depth

- << Previous: Get your URLs!

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 11:28 AM

- URL: https://bsu.libguides.com/EDPS260

Journal Article References

This page contains reference examples for journal articles, including the following:

- Journal article

- Journal article with an article number

- Journal article with missing information

- Retracted journal article

- Retraction notice for a journal article

- Abstract of a journal article from an abstract indexing database

- Monograph as part of a journal issue

- Online-only supplemental material to a journal article

1. Journal article

Grady, J. S., Her, M., Moreno, G., Perez, C., & Yelinek, J. (2019). Emotions in storybooks: A comparison of storybooks that represent ethnic and racial groups in the United States. Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 8 (3), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000185

- Parenthetical citation : (Grady et al., 2019)

- Narrative citation : Grady et al. (2019)

- If a journal article has a DOI, include the DOI in the reference.

- Always include the issue number for a journal article.

- If the journal article does not have a DOI and is from an academic research database, end the reference after the page range (for an explanation of why, see the database information page ). The reference in this case is the same as for a print journal article.

- Do not include database information in the reference unless the journal article comes from a database that publishes works of limited circulation or original, proprietary content, such as UpToDate .

- If the journal article does not have a DOI but does have a URL that will resolve for readers (e.g., it is from an online journal that is not part of a database), include the URL of the article at the end of the reference.

2. Journal article with an article number

Jerrentrup, A., Mueller, T., Glowalla, U., Herder, M., Henrichs, N., Neubauer, A., & Schaefer, J. R. (2018). Teaching medicine with the help of “Dr. House.” PLoS ONE , 13 (3), Article e0193972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193972

- Parenthetical citation : (Jerrentrup et al., 2018)

- Narrative citation : Jerrentrup et al. (2018)

- If the journal article has an article number instead of a page range, include the word “Article” and then the article number instead of the page range.

3. Journal article with missing information

Missing volume number.

Lipscomb, A. Y. (2021, Winter). Addressing trauma in the college essay writing process. The Journal of College Admission , (249), 30–33. https://www.catholiccollegesonline.org/pdf/national_ccaa_in_the_news_-_nacac_journal_of_college_admission_winter_2021.pdf

Missing issue number

Sanchiz, M., Chevalier, A., & Amadieu, F. (2017). How do older and young adults start searching for information? Impact of age, domain knowledge and problem complexity on the different steps of information searching. Computers in Human Behavior , 72 , 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.038

Missing page or article number

Butler, J. (2017). Where access meets multimodality: The case of ASL music videos. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy , 21 (1). http://technorhetoric.net/21.1/topoi/butler/index.html

- Parenthetical citations : (Butler, 2017; Lipscomb, 2021; Sanchiz et al., 2017)

- Narrative citations : Butler (2017), Lipscomb (2021), and Sanchiz et al. (2017)

- If the journal does not use volume, issue, and/or article or page numbers, omit the missing element(s) from the reference.

- If the journal is published quarterly and the month or season (Fall, Winter, Spring, Summer) is noted, include that with the date element; see the Lipscomb example.

- If the volume, issue, and/or article or page numbers have simply not yet been assigned, use the format for an advance online publication (see Example 7 in the Publication Manual ) or an in-press article (see Example 8 in the Publication Manual ).

4. Retracted journal article

Joly, J. F., Stapel, D. A., & Lindenberg, S. M. (2008). Silence and table manners: When environments activate norms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 34 (8), 1047–1056. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208318401 (Retraction published 2012, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38 [10], 1378)

- Parenthetical citation : (Joly et al., 2008)

- Narrative citation : Joly et al. (2008)

- Use this format to cite the retracted article itself, for example, to discuss the contents of the retracted article.

- First provide publication details of the original article. Then provide information about the retraction in parentheses, including its year, journal, volume, issue, and page number(s).

5. Retraction notice for a journal article

de la Fuente, R., Bernad, A., Garcia-Castro, J., Martin, M. C., & Cigudosa, J. C. (2010). Retraction: Spontaneous human adult stem cell transformation. Cancer Research , 70 (16), 6682. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2451

The Editors of the Lancet. (2010). Retraction—Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. The Lancet , 375 (9713), 445. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60175-4

- Parenthetical citations : (de la Fuente et al., 2010; The Editors of the Lancet, 2010)

- Narrative citations : de la Fuente et al. (2010) and The Editors of the Lancet (2010)

- Use this format to cite a retraction notice rather than a retracted article, for example, to provide information on why an article was retracted.

- The author of the retraction notice may be an editor, editorial board, or some or all authors of the article. Examine the retraction notice to determine who to credit as the author.

- Reproduce the title of the retraction notice as shown on the work. Note that the title may include the words “retraction,” “retraction notice,” or “retraction note” as well as the title of the original article.

6. Abstract of a journal article from an abstract indexing database

Hare, L. R., & O'Neill, K. (2000). Effectiveness and efficiency in small academic peer groups: A case study (Accession No. 200010185) [Abstract from Sociological Abstracts]. Small Group Research , 31 (1), 24–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649640003100102

- Parenthetical citation : (Hare & O’Neill, 2000)

- Narrative citation : Hare and O’Neill (2000)

- Although it is preferable to cite the whole article, the abstract can be cited if that is your only available source.

- The foundation of the reference is the same as for a journal article.

- If the abstract has a database accession number, place it in parentheses after the title.

- Note that you retrieved only the abstract by putting the words “Abstract from” and then the name of the abstract indexing database in square brackets. Place this bracketed description after the title and any accession number.

- Accession numbers are sometimes referred to as unique identifiers or as publication numbers (e.g., as PubMed IDs); use the term provided by the database in your reference.

7. Monograph as part of a journal issue

Ganster, D. C., Schaubroeck, J., Sime, W. E., & Mayes, B. T. (1991). The nomological validity of the Type A personality among employed adults [Monograph]. Journal of Applied Psychology , 76 (1), 143–168. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.1.143

- Parenthetical citation : (Ganster et al., 1991)

- Narrative citation : Ganster et al. (1991)

- For a monograph with an issue (or whole) number, include the issue number in parentheses followed by the serial number, for example, 58 (1, Serial No. 231).

- For a monograph bound separately as a supplement to a journal, give the issue number and supplement or part number in parentheses after the volume number, for example, 80 (3, Pt. 2).

8. Online-only supplemental material to a journal article

Freeberg, T. M. (2019). From simple rules of individual proximity, complex and coordinated collective movement [Supplemental material]. Journal of Comparative Psychology , 133 (2), 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/com0000181

- Parenthetical citation : (Freeberg, 2019)

- Narrative citation : Freeberg (2019)

- Include the description “[Supplemental material]” in square brackets after the article title.

- If you cite both the main article and the supplemental material, provide only a reference for the article.

Journal article references are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Section 10.1 and the Concise Guide Section 10.1

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.1 American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning objectives.

- Define APA style and list several of its most important characteristics.

- Identify three levels of APA style and give examples of each.

- Identify multiple sources of information about APA style.

What Is APA Style?

APA style is a set of guidelines for writing in psychology and related fields. These guidelines are set down in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2006). The Publication Manual originated in 1929 as a short journal article that provided basic standards for preparing manuscripts to be submitted for publication (Bentley et al., 1929). It was later expanded and published as a book by the association and is now in its sixth edition. The primary purpose of APA style is to facilitate scientific communication by promoting clarity of expression and by standardizing the organization and content of research articles and book chapters. It is easier to write about research when you know what information to present, the order in which to present it, and even the style in which to present it. Likewise, it is easier to read about research when it is presented in familiar and expected ways.

APA style is best thought of as a “genre” of writing that is appropriate for presenting the results of psychological research—especially in academic and professional contexts. It is not synonymous with “good writing” in general. You would not write a literary analysis for an English class, even if it were based on psychoanalytic concepts, in APA style. You would write it in Modern Language Association (MLA) style instead. And you would not write a newspaper article, even if it were about a new breakthrough in behavioral neuroscience, in APA style. You would write it in Associated Press (AP) style instead. At the same time, you would not write an empirical research report in MLA style, in AP style, or in the style of a romance novel, an e-mail to a friend, or a shopping list. You would write it in APA style. Part of being a good writer in general is adopting a style that is appropriate to the writing task at hand, and for writing about psychological research, this is APA style.

The Levels of APA Style

Because APA style consists of a large number and variety of guidelines—the Publication Manual is nearly 300 pages long—it can be useful to think about it in terms of three basic levels. The first is the overall organization of an article (which is covered in Chapter 2 “Getting Started in Research” of the Publication Manual ). Empirical research reports, in particular, have several distinct sections that always appear in the same order:

- Title page. Presents the article title and author names and affiliations.

- Abstract. Summarizes the research.

- Introduction. Describes previous research and the rationale for the current study.

- Method. Describes how the study was conducted.

- Results. Describes the results of the study.

- Discussion. Summarizes the study and discusses its implications.

- References. Lists the references cited throughout the article.

The second level of APA style can be referred to as high-level style (covered in Chapter 3 “Research Ethics” of the Publication Manual ), which includes guidelines for the clear expression of ideas. There are two important themes here. One is that APA-style writing is formal rather than informal. It adopts a tone that is appropriate for communicating with professional colleagues—other researchers and practitioners—who share an interest in the topic. Beyond this shared interest, however, these colleagues are not necessarily similar to the writer or to each other. A graduate student in California might be writing an article that will be read by a young psychotherapist in New York City and a respected professor of psychology in Tokyo. Thus formal writing avoids slang, contractions, pop culture references, humor, and other elements that would be acceptable in talking with a friend or in writing informally.

The second theme of high-level APA style is that it is straightforward. This means that it communicates ideas as simply and clearly as possible, putting the focus on the ideas themselves and not on how they are communicated. Thus APA-style writing minimizes literary devices such as metaphor, imagery, irony, suspense, and so on. Again, humor is kept to a minimum. Sentences are short and direct. Technical terms must be used, but they are used to improve communication, not simply to make the writing sound more “scientific.” For example, if participants immersed their hands in a bucket of ice water, it is better just to write this than to write that they “were subjected to a pain-inducement apparatus.” At the same time, however, there is no better way to communicate that a between-subjects design was used than to use the term “between-subjects design.”

APA Style and the Values of Psychology

Robert Madigan and his colleagues have argued that APA style has a purpose that often goes unrecognized (Madigan, Johnson, & Linton, 1995). Specifically, it promotes psychologists’ scientific values and assumptions. From this perspective, many features of APA style that at first seem arbitrary actually make good sense. Following are several features of APA-style writing and the scientific values or assumptions they reflect.

| APA style feature | Scientific value or assumption |

|---|---|

| There are very few direct quotations of other researchers. | The phenomena and theories of psychology are objective and do not depend on the specific words a particular researcher used to describe them. |

| Criticisms are directed at other researchers’ work but not at them personally. | The focus of scientific research is on drawing general conclusions about the world, not on the personalities of particular researchers. |

| There are many references and reference citations. | Scientific research is a large-scale collaboration among many researchers. |

| Empirical research reports are organized with specific sections in a fixed order. | There is an ideal approach to conducting empirical research in psychology (even if this ideal is not always achieved in actual research). |

| Researchers tend to “hedge” their conclusions, e.g., “The results that…” | Scientific knowledge is tentative and always subject to revision based on new empirical results. |

Another important element of high-level APA style is the avoidance of language that is biased against particular groups. This is not only to avoid offending people—why would you want to offend people who are interested in your work?—but also for the sake of scientific objectivity and accuracy. For example, the term sexual orientation should be used instead of sexual preference because people do not generally experience their orientation as a “preference,” nor is it as easily changeable as this term suggests (Committee on Lesbian and Gay Concerns, APA, 1991).

The general principles for avoiding biased language are fairly simple. First, be sensitive to labels by avoiding terms that are offensive or have negative connotations. This includes terms that identify people with a disorder or other problem they happen to have. For example, patients with schizophrenia is better than schizophrenics . Second, use more specific terms rather than more general ones. For example, Mexican Americans is better than Hispanics if everyone in the group is, in fact, Mexican American. Third, avoid objectifying research participants. Instead, acknowledge their active contribution to the research. For example, “The students completed the questionnaire” is better than “The subjects were administered the questionnaire.” Note that this principle also makes for clearer, more engaging writing. Table 11.1 “Examples of Avoiding Biased Language” shows several more examples that follow these general principles.

Table 11.1 Examples of Avoiding Biased Language

| Instead of… | Use… |

|---|---|

| man, men | men and women, people |

| firemen | firefighters |

| homosexuals, gays, bisexuals | lesbians, gay men, bisexual men, bisexual women |

| minority | specific group label (e.g., African American) |

| neurotics | people scoring high in neuroticism |

| special children | children with learning disabilities |

The previous edition of the Publication Manual strongly discouraged the use of the term subjects (except for nonhumans) and strongly encouraged the use of participants instead. The current edition, however, acknowledges that subjects can still be appropriate in referring to human participants in areas in which it has traditionally been used (e.g., basic memory research). But it also encourages the use of more specific terms when possible: college students , children , respondents , and so on.

The third level of APA style can be referred to as low-level style (which is covered in Chapter 4 “Theory in Psychology” through Chapter 7 “Nonexperimental Research” of the Publication Manual .) Low-level style includes all the specific guidelines pertaining to spelling, grammar, references and reference citations, numbers and statistics, figures and tables, and so on. There are so many low-level guidelines that even experienced professionals need to consult the Publication Manual from time to time. Table 11.2 “Top 10 APA Style Errors” contains some of the most common types of APA style errors based on an analysis of manuscripts submitted to one professional journal over a 6-year period (Onwuegbuzie, Combs, Slate, & Frels, 2010). These errors were committed by professional researchers but are probably similar to those that students commit the most too. See also Note 11.8 “Online APA Style Resources” in this section and, of course, the Publication Manual itself.

Table 11.2 Top 10 APA Style Errors

| Error type | Example |

|---|---|

| 1. Use of numbers | Failing to use numerals for 10 and above |

| 2. Hyphenation | Failing to hyphenate compound adjectives that precede a noun (e.g., “role playing technique” should be “role-playing technique”) |

| 3. Use of | Failing to use it after a reference is cited for the first time |

| 4. Headings | Not capitalizing headings correctly |

| 5. Use of | Using to mean |

| 6. Tables and figures | Not formatting them in APA style; repeating information that is already given in the text |

| 7. Use of commas | Failing to use a comma before or in a series of three or more elements |

| 8. Use of abbreviations | Failing to spell out a term completely before introducing an abbreviation for it |

| 9. Spacing | Not consistently double-spacing between lines |

| 10. Use of in references | Using in the text or in parentheses |

Online APA Style Resources

The best source of information on APA style is the Publication Manual itself. However, there are also many good websites on APA style, which do an excellent job of presenting the basics for beginning researchers. Here are a few of them.

http://www.apastyle.org

Doc Scribe’s APA Style Lite

http://www.docstyles.com/apalite.htm

Purdue Online Writing Lab

http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/01

Douglas Degelman’s APA Style Essentials

http://www.vanguard.edu/Home/AcademicResources/Faculty/DougDegelman/APAStyleEssentials.aspx

APA-Style References and Citations

Because science is a large-scale collaboration among researchers, references to the work of other researchers are extremely important. Their importance is reflected in the extensive and detailed set of rules for formatting and using them.

At the end of an APA-style article or book chapter is a list that contains references to all the works cited in the text (and only the works cited in the text). The reference list begins on its own page, with the heading “References,” centered in upper and lower case. The references themselves are then listed alphabetically according to the last names of the first named author for each citation. (As in the rest of an APA-style manuscript, everything is double-spaced.) Many different kinds of works might be cited in APA-style articles and book chapters, including magazine articles, websites, government documents, and even television shows. Of course, you should consult the Publication Manual or Online APA Style Resources for details on how to format them. Here we will focus on formatting references for the three most common kinds of works cited in APA style: journal articles, books, and book chapters.

Journal Articles

For journal articles, the generic format for a reference is as follows:

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Title of article. Title of Journal, xx , pp–pp. doi:xx.xxxxxxxxxx

Here is a concrete example:

Adair, J. G., & Vohra, N. (2003). The explosion of knowledge, references, and citations: Psychology’s unique response to a crisis. American Psychologist, 58 , 15–23. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.15

There are several things to notice here. The reference includes a hanging indent. That is, the first line of the reference is not indented but all subsequent lines are. The authors’ names appear in the same order as on the article, which reflects the authors’ relative contributions to the research. Only the authors’ last names and initials appear, and the names are separated by commas with an ampersand (&) between the last two. This is true even when there are only two authors. Only the first word of the article title is capitalized. The only exceptions are for words that are proper nouns or adjectives (e.g., “Freudian”) or if there is a subtitle, in which case the first word of the subtitle is also capitalized. In the journal title, however, all the important words are capitalized. The journal title and volume number are italicized. At the very end of the reference is the digital object identifier (DOI), which provides a permanent link to the location of the article on the Internet. Include this if it is available. It can generally be found in the record for the item on an electronic database (e.g., PsycINFO) and is usually displayed on the first page of the published article.

For a book, the generic format and a concrete example are as follows:

Author, A. A. (year). Title of book . Location: Publisher.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Book Chapters

For a chapter in an edited book, the generic format and a concrete example are as follows:

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Title of chapter. In A. A. Editor, B. B. Editor, & C. C. Editor (Eds.), Title of book (pp. xxx–xxx). Location: Publisher.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Lynn, S. J. (2003). Dissociative identity disorder: Multiple personalities, multiple controversies. In S. O. Lilienfeld, S. J. Lynn, & J. M. Lohr (Eds.), Science and pseudoscience in clinical psychology (pp. 109–142). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Notice that references for books and book chapters are similar to those for journal articles, but there are several differences too. For an edited book, the names of the editors appear with their first and middle initials followed by their last names (not the other way around)—with the abbreviation “Eds.” (or “Ed.,” if there is only one) appearing in parentheses immediately after the final editor’s name. Only the first word of a book title is capitalized (with the exceptions noted for article titles), and the entire title is italicized. For a chapter in an edited book, the page numbers of the chapter appear in parentheses after the book title with the abbreviation “pp.” Finally, both formats end with the location of publication and the publisher, separated by a colon.

Reference Citations

When you refer to another researcher’s idea, you must include a reference citation (in the text) to the work in which that idea originally appeared and a full reference to that work in the reference list. What counts as an idea that must be cited? In general, this includes phenomena discovered by other researchers, theories they have developed, hypotheses they have derived, and specific methods they have used (e.g., specific questionnaires or stimulus materials). Citations should also appear for factual information that is not common knowledge so that other researchers can check that information for themselves. For example, in an article on the effect of cell phone usage on driving ability, the writer might cite official statistics on the number of cell phone–related accidents that occur each year. Among the ideas that do not need citations are widely shared methodological and statistical concepts (e.g., between-subjects design, t test) and statements that are so broad that they would be difficult for anyone to argue with (e.g., “Working memory plays a role in many daily activities.”). Be careful, though, because “common knowledge” about human behavior is often incorrect. Therefore, when in doubt, find an appropriate reference to cite or remove the questionable assertion.

When you cite a work in the text of your manuscript, there are two ways to do it. Both include only the last names of the authors and the year of publication. The first method is to use the authors’ last names in the sentence (with no first names or initials) followed immediately by the year of publication in parentheses. Here are some examples:

Burger (2008) conducted a replication of Milgram’s (1963) original obedience study.

Although many people believe that women are more talkative than men, Mehl, Vazire, Ramirez-Esparza, Slatcher, and Pennebaker (2007) found essentially no difference in the number of words spoken by male and female college students.

Notice several things. First, the authors’ names are treated grammatically as names of people, not as things. It is better to write “a replication of Milgram’s (1963) study” than “a replication of Milgram (1963).” Second, when there are two authors the names are not separated by commas, but when there are three or more authors they are. Third, the word and (rather than an ampersand) is used to join the authors’ names. Fourth, the year follows immediately after the final author’s name. An additional point, which is not illustrated in these examples but is illustrated in the sample paper in Section 11.2 “Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style” , is that the year only needs to be included the first time a particular work is cited in the same paragraph.

The second way to cite an article or a book chapter is parenthetically—including the authors’ last names and the year of publication in parentheses following the idea that is being credited. Here are some examples:

People can be surprisingly obedient to authority figures (Burger, 2008; Milgram, 1963).

Recent evidence suggests that men and women are similarly talkative (Mehl, Vazire, Ramirez-Esparza, Slatcher, & Pennebaker, 2007).

One thing to notice about such parenthetical citations is that they are often placed at the end of the sentence, which minimizes their disruption to the flow of that sentence. In contrast to the first way of citing a work, this way always includes the year—even when the citation is given multiple times in the same paragraph. Notice also that when there are multiple citations in the same set of parentheses, they are organized alphabetically by the name of the first author and separated by semicolons.

There are no strict rules for deciding which of the two citation styles to use. Most articles and book chapters contain a mixture of the two. In general, however, the first approach works well when you want to emphasize the person who conducted the research—for example, if you were comparing the theories of two prominent researchers. It also works well when you are describing a particular study in detail. The second approach works well when you are discussing a general idea and especially when you want to include multiple citations for the same idea.

The third most common error in Table 11.2 “Top 10 APA Style Errors” has to do with the use of et al. This is an abbreviation for the Latin term et alia , which means “and others.” In APA style, if an article or a book chapter has more than two authors, you should include all their names when you first cite that work. After that, however, you should use the first author’s name followed by “et al.” Here are some examples:

Recall that Mehl et al. (2007) found that women and men spoke about the same number of words per day on average.

There is a strong positive correlation between the number of daily hassles and the number of symptoms people experience (Kanner et al., 1981).

Notice that there is no comma between the first author’s name and “et al.” Notice also that there is no period after “et” but there is one after “al.” This is because “et” is a complete word and “al.” is an abbreviation for the word alia .

Key Takeaways

- APA style is a set of guidelines for writing in psychology. It is the genre of writing that psychologists use to communicate about their research with other researchers and practitioners.

- APA style can be seen as having three levels. There is the organization of a research article, the high-level style that includes writing in a formal and straightforward way, and the low-level style that consists of many specific rules of grammar, spelling, formatting of references, and so on.

- References and reference citations are an important part of APA style. There are specific rules for formatting references and for citing them in the text of an article.

- Practice: Find a description of a research study in a popular magazine, newspaper, blog, or website. Then identify five specific differences between how that description is written and how it would be written in APA style.

Practice: Find and correct the errors in the following fictional APA-style references and citations.

- Walters, F. T., and DeLeon, M. (2010). Relationship Between Intrinsic Motivation and Accuracy of Academic Self-Evaluations Among High School Students. Educational Psychology Quarterly , 23, 234–256.

- Moore, Lilia S. (2007). Ethics in survey research. In M. Williams & P. L. Lee (eds.), Ethical Issues in Psychology (pp. 120–156), Boston, Psychological Research Press.

- Vang, C., Dumont, L. S., and Prescott, M. P. found that left-handed people have a stronger preference for abstract art than right-handed people (2006).

- This result has been replicated several times (Williamson, 1998; Pentecost & Garcia, 2006; Armbruster, 2011)

American Psychological Association. (2006). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bentley, M., Peerenboom, C. A., Hodge, F. W., Passano, E. B., Warren, H. C., & Washburn, M. F. (1929). Instructions in regard to preparation of manuscript. Psychological Bulletin, 26 , 57–63.

Committee on Lesbian and Gay Concerns, American Psychological Association. (1991). Avoiding heterosexual bias in language. American Psychologist, 46 , 973–974. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/language.aspx .

Madigan, R., Johnson, S., & Linton, P. (1995). The language of psychology: APA style as epistemology. American Psychologist, 50 , 428–436.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Combs, J. P., Slate, J. R., & Frels, R. K. (2010). Editorial: Evidence-based guidelines for avoiding the most common APA errors in journal article submissions. Research in the Schools, 16 , ix–xxxvi.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- How to write an APA methods section

How to Write an APA Methods Section | With Examples

Published on February 5, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

The methods section of an APA style paper is where you report in detail how you performed your study. Research papers in the social and natural sciences often follow APA style. This article focuses on reporting quantitative research methods .

In your APA methods section, you should report enough information to understand and replicate your study, including detailed information on the sample , measures, and procedures used.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Structuring an apa methods section.

Participants

Example of an APA methods section

Other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing an apa methods section.

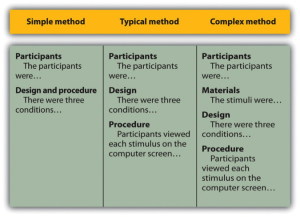

The main heading of “Methods” should be centered, boldfaced, and capitalized. Subheadings within this section are left-aligned, boldfaced, and in title case. You can also add lower level headings within these subsections, as long as they follow APA heading styles .

To structure your methods section, you can use the subheadings of “Participants,” “Materials,” and “Procedures.” These headings are not mandatory—aim to organize your methods section using subheadings that make sense for your specific study.

| Heading | What to include |

|---|---|

| Participants | |

| Materials | |

| Procedure |

Note that not all of these topics will necessarily be relevant for your study. For example, if you didn’t need to consider outlier removal or ways of assigning participants to different conditions, you don’t have to report these steps.

The APA also provides specific reporting guidelines for different types of research design. These tell you exactly what you need to report for longitudinal designs , replication studies, experimental designs , and so on. If your study uses a combination design, consult APA guidelines for mixed methods studies.

Detailed descriptions of procedures that don’t fit into your main text can be placed in supplemental materials (for example, the exact instructions and tasks given to participants, the full analytical strategy including software code, or additional figures and tables).

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

Begin the methods section by reporting sample characteristics, sampling procedures, and the sample size.

Participant or subject characteristics

When discussing people who participate in research, descriptive terms like “participants,” “subjects” and “respondents” can be used. For non-human animal research, “subjects” is more appropriate.

Specify all relevant demographic characteristics of your participants. This may include their age, sex, ethnic or racial group, gender identity, education level, and socioeconomic status. Depending on your study topic, other characteristics like educational or immigration status or language preference may also be relevant.

Be sure to report these characteristics as precisely as possible. This helps the reader understand how far your results may be generalized to other people.

The APA guidelines emphasize writing about participants using bias-free language , so it’s necessary to use inclusive and appropriate terms.

Sampling procedures

Outline how the participants were selected and all inclusion and exclusion criteria applied. Appropriately identify the sampling procedure used. For example, you should only label a sample as random if you had access to every member of the relevant population.

Of all the people invited to participate in your study, note the percentage that actually did (if you have this data). Additionally, report whether participants were self-selected, either by themselves or by their institutions (e.g., schools may submit student data for research purposes).

Identify any compensation (e.g., course credits or money) that was provided to participants, and mention any institutional review board approvals and ethical standards followed.

Sample size and power

Detail the sample size (per condition) and statistical power that you hoped to achieve, as well as any analyses you performed to determine these numbers.

It’s important to show that your study had enough statistical power to find effects if there were any to be found.

Additionally, state whether your final sample differed from the intended sample. Your interpretations of the study outcomes should be based only on your final sample rather than your intended sample.

Write up the tools and techniques that you used to measure relevant variables. Be as thorough as possible for a complete picture of your techniques.

Primary and secondary measures

Define the primary and secondary outcome measures that will help you answer your primary and secondary research questions.

Specify all instruments used in gathering these measurements and the construct that they measure. These instruments may include hardware, software, or tests, scales, and inventories.

- To cite hardware, indicate the model number and manufacturer.

- To cite common software (e.g., Qualtrics), state the full name along with the version number or the website URL .

- To cite tests, scales or inventories, reference its manual or the article it was published in. It’s also helpful to state the number of items and provide one or two example items.

Make sure to report the settings of (e.g., screen resolution) any specialized apparatus used.

For each instrument used, report measures of the following:

- Reliability : how consistently the method measures something, in terms of internal consistency or test-retest reliability.

- Validity : how precisely the method measures something, in terms of construct validity or criterion validity .

Giving an example item or two for tests, questionnaires , and interviews is also helpful.

Describe any covariates—these are any additional variables that may explain or predict the outcomes.

Quality of measurements

Review all methods you used to assure the quality of your measurements.

These may include:

- training researchers to collect data reliably,

- using multiple people to assess (e.g., observe or code) the data,

- translation and back-translation of research materials,

- using pilot studies to test your materials on unrelated samples.

For data that’s subjectively coded (for example, classifying open-ended responses), report interrater reliability scores. This tells the reader how similarly each response was rated by multiple raters.

Report all of the procedures applied for administering the study, processing the data, and for planned data analyses.

Data collection methods and research design

Data collection methods refers to the general mode of the instruments: surveys, interviews, observations, focus groups, neuroimaging, cognitive tests, and so on. Summarize exactly how you collected the necessary data.

Describe all procedures you applied in administering surveys, tests, physical recordings, or imaging devices, with enough detail so that someone else can replicate your techniques. If your procedures are very complicated and require long descriptions (e.g., in neuroimaging studies), place these details in supplementary materials.

To report research design, note your overall framework for data collection and analysis. State whether you used an experimental, quasi-experimental, descriptive (observational), correlational, and/or longitudinal design. Also note whether a between-subjects or a within-subjects design was used.

For multi-group studies, report the following design and procedural details as well:

- how participants were assigned to different conditions (e.g., randomization),

- instructions given to the participants in each group,

- interventions for each group,

- the setting and length of each session(s).

Describe whether any masking was used to hide the condition assignment (e.g., placebo or medication condition) from participants or research administrators. Using masking in a multi-group study ensures internal validity by reducing research bias . Explain how this masking was applied and whether its effectiveness was assessed.

Participants were randomly assigned to a control or experimental condition. The survey was administered using Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com). To begin, all participants were given the AAI and a demographics questionnaire to complete, followed by an unrelated filler task. In the control condition , participants completed a short general knowledge test immediately after the filler task. In the experimental condition, participants were asked to visualize themselves taking the test for 3 minutes before they actually did. For more details on the exact instructions and tasks given, see supplementary materials.

Data diagnostics

Outline all steps taken to scrutinize or process the data after collection.

This includes the following:

- Procedures for identifying and removing outliers

- Data transformations to normalize distributions

- Compensation strategies for overcoming missing values

To ensure high validity, you should provide enough detail for your reader to understand how and why you processed or transformed your raw data in these specific ways.

Analytic strategies

The methods section is also where you describe your statistical analysis procedures, but not their outcomes. Their outcomes are reported in the results section.

These procedures should be stated for all primary, secondary, and exploratory hypotheses. While primary and secondary hypotheses are based on a theoretical framework or past studies, exploratory hypotheses are guided by the data you’ve just collected.

Are your APA in-text citations flawless?

The AI-powered APA Citation Checker points out every error, tells you exactly what’s wrong, and explains how to fix it. Say goodbye to losing marks on your assignment!

Get started!

This annotated example reports methods for a descriptive correlational survey on the relationship between religiosity and trust in science in the US. Hover over each part for explanation of what is included.

The sample included 879 adults aged between 18 and 28. More than half of the participants were women (56%), and all participants had completed at least 12 years of education. Ethics approval was obtained from the university board before recruitment began. Participants were recruited online through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk; www.mturk.com). We selected for a geographically diverse sample within the Midwest of the US through an initial screening survey. Participants were paid USD $5 upon completion of the study.

A sample size of at least 783 was deemed necessary for detecting a correlation coefficient of ±.1, with a power level of 80% and a significance level of .05, using a sample size calculator (www.sample-size.net/correlation-sample-size/).

The primary outcome measures were the levels of religiosity and trust in science. Religiosity refers to involvement and belief in religious traditions, while trust in science represents confidence in scientists and scientific research outcomes. The secondary outcome measures were gender and parental education levels of participants and whether these characteristics predicted religiosity levels.

Religiosity

Religiosity was measured using the Centrality of Religiosity scale (Huber, 2003). The Likert scale is made up of 15 questions with five subscales of ideology, experience, intellect, public practice, and private practice. An example item is “How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God or something divine intervenes in your life?” Participants were asked to indicate frequency of occurrence by selecting a response ranging from 1 (very often) to 5 (never). The internal consistency of the instrument is .83 (Huber & Huber, 2012).

Trust in Science

Trust in science was assessed using the General Trust in Science index (McCright, Dentzman, Charters & Dietz, 2013). Four Likert scale items were assessed on a scale from 1 (completely distrust) to 5 (completely trust). An example question asks “How much do you distrust or trust scientists to create knowledge that is unbiased and accurate?” Internal consistency was .8.

Potential participants were invited to participate in the survey online using Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com). The survey consisted of multiple choice questions regarding demographic characteristics, the Centrality of Religiosity scale, an unrelated filler anagram task, and finally the General Trust in Science index. The filler task was included to avoid priming or demand characteristics, and an attention check was embedded within the religiosity scale. For full instructions and details of tasks, see supplementary materials.

For this correlational study , we assessed our primary hypothesis of a relationship between religiosity and trust in science using Pearson moment correlation coefficient. The statistical significance of the correlation coefficient was assessed using a t test. To test our secondary hypothesis of parental education levels and gender as predictors of religiosity, multiple linear regression analysis was used.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

In your APA methods section , you should report detailed information on the participants, materials, and procedures used.

- Describe all relevant participant or subject characteristics, the sampling procedures used and the sample size and power .

- Define all primary and secondary measures and discuss the quality of measurements.

- Specify the data collection methods, the research design and data analysis strategy, including any steps taken to transform the data and statistical analyses.

You should report methods using the past tense , even if you haven’t completed your study at the time of writing. That’s because the methods section is intended to describe completed actions or research.

In a scientific paper, the methodology always comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion . The same basic structure also applies to a thesis, dissertation , or research proposal .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). How to Write an APA Methods Section | With Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/methods-section/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, how to write an apa results section, apa format for academic papers and essays, apa headings and subheadings, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".