Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application

- Open Access

- First Online: 22 November 2019

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Mark Newman 6 &

- David Gough 6

86k Accesses

145 Citations

2 Altmetric

This chapter explores the processes of reviewing literature as a research method. The logic of the family of research approaches called systematic review is analysed and the variation in techniques used in the different approaches explored using examples from existing reviews. The key distinctions between aggregative and configurative approaches are illustrated and the chapter signposts further reading on key issues in the systematic review process.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Reviewing Literature for and as Research

Methodological Approaches to Literature Review

The Role of Meta-analysis in Educational Research

1 what are systematic reviews.

A literature review is a scholarly paper which provides an overview of current knowledge about a topic. It will typically include substantive findings, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to a particular topic (Hart 2018 , p. xiii). Traditionally in education ‘reviewing the literature’ and ‘doing research’ have been viewed as distinct activities. Consider the standard format of research proposals, which usually have some kind of ‘review’ of existing knowledge presented distinctly from the methods of the proposed new primary research. However, both reviews and research are undertaken in order to find things out. Reviews to find out what is already known from pre-existing research about a phenomena, subject or topic; new primary research to provide answers to questions about which existing research does not provide clear and/or complete answers.

When we use the term research in an academic sense it is widely accepted that we mean a process of asking questions and generating knowledge to answer these questions using rigorous accountable methods. As we have noted, reviews also share the same purposes of generating knowledge but historically we have not paid as much attention to the methods used for reviewing existing literature as we have to the methods used for primary research. Literature reviews can be used for making claims about what we know and do not know about a phenomenon and also about what new research we need to undertake to address questions that are unanswered. Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that ‘how’ we conduct a review of research is important.

The increased focus on the use of research evidence to inform policy and practice decision-making in Evidence Informed Education (Hargreaves 1996 ; Nelson and Campbell 2017 ) has increased the attention given to contextual and methodological limitations of research evidence provided by single studies. Reviews of research may help address these concerns when carried on in a systematic, rigorous and transparent manner. Thus, again emphasizing the importance of ‘how’ reviews are completed.

The logic of systematic reviews is that reviews are a form of research and thus can be improved by using appropriate and explicit methods. As the methods of systematic review have been applied to different types of research questions, there has been an increasing plurality of types of systematic review. Thus, the term ‘systematic review’ is used in this chapter to refer to a family of research approaches that are a form of secondary level analysis (secondary research) that brings together the findings of primary research to answer a research question. Systematic reviews can therefore be defined as “a review of existing research using explicit, accountable rigorous research methods” (Gough et al. 2017 , p. 4).

2 Variation in Review Methods

Reviews can address a diverse range of research questions. Consequently, as with primary research, there are many different approaches and methods that can be applied. The choices should be dictated by the review questions. These are shaped by reviewers’ assumptions about the meaning of a particular research question, the approach and methods that are best used to investigate it. Attempts to classify review approaches and methods risk making hard distinctions between methods and thereby to distract from the common defining logics that these approaches often share. A useful broad distinction is between reviews that follow a broadly configurative synthesis logic and reviews that follow a broadly aggregative synthesis logic (Sandelowski et al. 2012 ). However, it is important to keep in mind that most reviews have elements of both (Gough et al. 2012 ).

Reviews that follow a broadly configurative synthesis logic approach usually investigate research questions about meaning and interpretation to explore and develop theory. They tend to use exploratory and iterative review methods that emerge throughout the process of the review. Studies included in the review are likely to have investigated the phenomena of interest using methods such as interviews and observations, with data in the form of text. Reviewers are usually interested in purposive variety in the identification and selection of studies. Study quality is typically considered in terms of authenticity. Synthesis consists of the deliberative configuring of data by reviewers into patterns to create a richer conceptual understanding of a phenomenon. For example, meta ethnography (Noblit and Hare 1988 ) uses ethnographic data analysis methods to explore and integrate the findings of previous ethnographies in order to create higher-level conceptual explanations of phenomena. There are many other review approaches that follow a broadly configurative logic (for an overview see Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009 ); reflecting the variety of methods used in primary research in this tradition.

Reviews that follow a broadly aggregative synthesis logic usually investigate research questions about impacts and effects. For example, systematic reviews that seek to measure the impact of an educational intervention test the hypothesis that an intervention has the impact that has been predicted. Reviews following an aggregative synthesis logic do not tend to develop theory directly; though they can contribute by testing, exploring and refining theory. Reviews following an aggregative synthesis logic tend to specify their methods in advance (a priori) and then apply them without any deviation from a protocol. Reviewers are usually concerned to identify the comprehensive set of studies that address the research question. Studies included in the review will usually seek to determine whether there is a quantitative difference in outcome between groups receiving and not receiving an intervention. Study quality assessment in reviews following an aggregative synthesis logic focusses on the minimisation of bias and thus selection pays particular attention to homogeneity between studies. Synthesis aggregates, i.e. counts and adds together, the outcomes from individual studies using, for example, statistical meta-analysis to provide a pooled summary of effect.

3 The Systematic Review Process

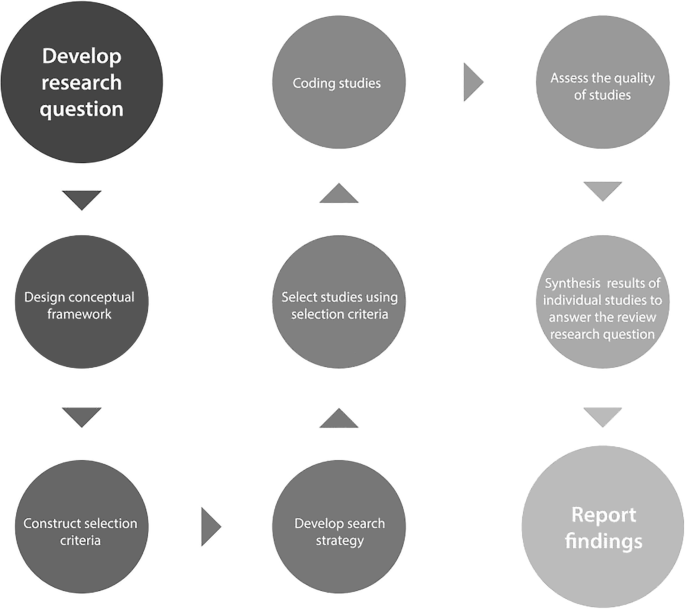

Different types of systematic review are discussed in more detail later in this chapter. The majority of systematic review types share a common set of processes. These processes can be divided into distinct but interconnected stages as illustrated in Fig. 1 . Systematic reviews need to specify a research question and the methods that will be used to investigate the question. This is often written as a ‘protocol’ prior to undertaking the review. Writing a protocol or plan of the methods at the beginning of a review can be a very useful activity. It helps the review team to gain a shared understanding of the scope of the review and the methods that they will use to answer the review’s questions. Different types of systematic reviews will have more or less developed protocols. For example, for systematic reviews investigating research questions about the impact of educational interventions it is argued that a detailed protocol should be fully specified prior to the commencement of the review to reduce the possibility of reviewer bias (Torgerson 2003 , p. 26). For other types of systematic review, in which the research question is more exploratory, the protocol may be more flexible and/or developmental in nature.

The systematic review process

3.1 Systematic Review Questions and the Conceptual Framework

The review question gives each review its particular structure and drives key decisions about what types of studies to include; where to look for them; how to assess their quality; and how to combine their findings. Although a research question may appear to be simple, it will include many assumptions. Whether implicit or explicit, these assumptions will include: epistemological frameworks about knowledge and how we obtain it, theoretical frameworks, whether tentative or firm, about the phenomenon that is the focus of study.

Taken together, these produce a conceptual framework that shapes the research questions, choices about appropriate systematic review approach and methods. The conceptual framework may be viewed as a working hypothesis that can be developed, refined or confirmed during the course of the research. Its purpose is to explain the key issues to be studied, the constructs or variables, and the presumed relationships between them. The framework is a research tool intended to assist a researcher to develop awareness and understanding of the phenomena under scrutiny and to communicate this (Smyth 2004 ).

A review to investigate the impact of an educational intervention will have a conceptual framework that includes a hypothesis about a causal link between; who the review is about (the people), what the review is about (an intervention and what it is being compared with), and the possible consequences of intervention on the educational outcomes of these people. Such a review would follow a broadly aggregative synthesis logic. This is the shape of reviews of educational interventions carried out for the What Works Clearing House in the USA Footnote 1 and the Education Endowment Foundation in England. Footnote 2

A review to investigate meaning or understanding of a phenomenon for the purpose of building or further developing theory will still have some prior assumptions. Thus, an initial conceptual framework will contain theoretical ideas about how the phenomena of interest can be understood and some ideas justifying why a particular population and/or context is of specific interest or relevance. Such a review is likely to follow a broadly configurative logic.

3.2 Selection Criteria

Reviewers have to make decisions about which research studies to include in their review. In order to do this systematically and transparently they develop rules about which studies can be selected into the review. Selection criteria (sometimes referred to as inclusion or exclusion criteria) create restrictions on the review. All reviews, whether systematic or not, limit in some way the studies that are considered by the review. Systematic reviews simply make these restrictions transparent and therefore consistent across studies. These selection criteria are shaped by the review question and conceptual framework. For example, a review question about the impact of homework on educational attainment would have selection criteria specifying who had to do the homework; the characteristics of the homework and the outcomes that needed to be measured. Other commonly used selection criteria include study participant characteristics; the country where the study has taken place and the language in which the study is reported. The type of research method(s) may also be used as a selection criterion but this can be controversial given the lack of consensus in education research (Newman 2008 ), and the inconsistent terminology used to describe education research methods.

3.3 Developing the Search Strategy

The search strategy is the plan for how relevant research studies will be identified. The review question and conceptual framework shape the selection criteria. The selection criteria specify the studies to be included in a review and thus are a key driver of the search strategy. A key consideration will be whether the search aims to be exhaustive i.e. aims to try and find all the primary research that has addressed the review question. Where reviews address questions about effectiveness or impact of educational interventions the issue of publication bias is a concern. Publication bias is the phenomena whereby smaller and/or studies with negative findings are less likely to be published and/or be harder to find. We may therefore inadvertently overestimate the positive effects of an educational intervention because we do not find studies with negative or smaller effects (Chow and Eckholm 2018 ). Where the review question is not of this type then a more specific or purposive search strategy, that may or may not evolve as the review progresses, may be appropriate. This is similar to sampling approaches in primary research. In primary research studies using aggregative approaches, such as quasi-experiments, analysis is based on the study of complete or representative samples. In primary research studies using configurative approaches, such as ethnography, analysis is based on examining a range of instances of the phenomena in similar or different contexts.

The search strategy will detail the sources to be searched and the way in which the sources will be searched. A list of search source types is given in Box 1 below. An exhaustive search strategy would usually include all of these sources using multiple bibliographic databases. Bibliographic databases usually index academic journals and thus are an important potential source. However, in most fields, including education, relevant research is published in a range of journals which may be indexed in different bibliographic databases and thus it may be important to search multiple bibliographic databases. Furthermore, some research is published in books and an increasing amount of research is not published in academic journals or at least may not be published there first. Thus, it is important to also consider how you will find relevant research in other sources including ‘unpublished’ or ‘grey’ literature. The Internet is a valuable resource for this purpose and should be included as a source in any search strategy.

Box 1: Search Sources

The World Wide Web/Internet

Google, Specialist Websites, Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic

Bibliographic Databases

Subject specific e.g. Education—ERIC: Education Resources Information Centre

Generic e.g. ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts

Handsearching of specialist journals or books

Contacts with Experts

Citation Checking

New, federated search engines are being developed, which search multiple sources at the same time, eliminating duplicates automatically (Tsafnat et al. 2013 ). Technologies, including text mining, are being used to help develop search strategies, by suggesting topics and terms on which to search—terms that reviewers may not have thought of using. Searching is also being aided by technology through the increased use (and automation) of ‘citation chasing’, where papers that cite, or are cited by, a relevant study are checked in case they too are relevant.

A search strategy will identify the search terms that will be used to search the bibliographic databases. Bibliographic databases usually index records according to their topic using ‘keywords’ or ‘controlled terms’ (categories used by the database to classify papers). A comprehensive search strategy usually involves searching both a freetext search using keywords determined by the reviewers and controlled terms. An example of a bibliographic database search is given in Box 2. This search was used in a review that aimed to find studies that investigated the impact of Youth Work on positive youth outcomes (Dickson et al. 2013 ). The search is built using terms for the population of interest (Youth), the intervention of interest (Youth Work) and the outcomes of Interest (Positive Development). It used both keywords and controlled terms, ‘wildcards’ (the *sign in this database) and the Boolean operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ to combine terms. This example illustrates the potential complexity of bibliographic database search strings, which will usually require a process of iterative development to finalise.

Box 2: Search string example To identify studies that address the question What is the empirical research evidence on the impact of youth work on the lives of children and young people aged 10-24 years?: CSA ERIC Database

((TI = (adolescen* or (“young man*”) or (“young men”)) or TI = ((“young woman*”) or (“young women”) or (Young adult*”)) or TI = ((“young person*”) or (“young people*”) or teen*) or AB = (adolescen* or (“young man*”) or (“young men”)) or AB = ((“young woman*”) or (“young women”) or (Young adult*”)) or AB = ((“young person*”) or (“young people*”) or teen*)) or (DE = (“youth” or “adolescents” or “early adolescents” or “late adolescents” or “preadolescents”))) and(((TI = ((“positive youth development “) or (“youth development”) or (“youth program*”)) or TI = ((“youth club*”) or (“youth work”) or (“youth opportunit*”)) or TI = ((“extended school*”) or (“civic engagement”) or (“positive peer culture”)) or TI = ((“informal learning”) or multicomponent or (“multi-component “)) or TI = ((“multi component”) or multidimensional or (“multi-dimensional “)) or TI = ((“multi dimensional”) or empower* or asset*) or TI = (thriv* or (“positive development”) or resilienc*) or TI = ((“positive activity”) or (“positive activities”) or experiential) or TI = ((“community based”) or “community-based”)) or(AB = ((“positive youth development “) or (“youth development”) or (“youth program*”)) or AB = ((“youth club*”) or (“youth work”) or (“youth opportunit*”)) or AB = ((“extended school*”) or (“civic engagement”) or (“positive peer culture”)) or AB = ((“informal learning”) or multicomponent or (“multi-component “)) or AB = ((“multi component”) or multidimensional or (“multi-dimensional “)) or AB = ((“multi dimensional”) or empower* or asset*) or AB = (thriv* or (“positive development”) or resilienc*) or AB = ((“positive activity”) or (“positive activities”) or experiential) or AB = ((“community based”) or “community-based”))) or (DE=”community education”))

Detailed guidance for finding effectiveness studies is available from the Campbell Collaboration (Kugley et al. 2015 ). Guidance for finding a broader range of studies has been produced by the EPPI-Centre (Brunton et al. 2017a ).

3.4 The Study Selection Process

Studies identified by the search are subject to a process of checking (sometimes referred to as screening) to ensure they meet the selection criteria. This is usually done in two stages whereby titles and abstracts are checked first to determine whether the study is likely to be relevant and then a full copy of the paper is acquired to complete the screening exercise. The process of finding studies is not efficient. Searching bibliographic databases, for example, leads to many irrelevant studies being found which then have to be checked manually one by one to find the few relevant studies. There is increasing use of specialised software to support and in some cases, automate the selection process. Text mining, for example, can assist in selecting studies for a review (Brunton et al. 2017b ). A typical text mining or machine learning process might involve humans undertaking some screening, the results of which are used to train the computer software to learn the difference between included and excluded studies and thus be able to indicate which of the remaining studies are more likely to be relevant. Such automated support may result in some errors in selection, but this may be less than the human error in manual selection (O’Mara-Eves et al. 2015 ).

3.5 Coding Studies

Once relevant studies have been selected, reviewers need to systematically identify and record the information from the study that will be used to answer the review question. This information includes the characteristics of the studies, including details of the participants and contexts. The coding describes: (i) details of the studies to enable mapping of what research has been undertaken; (ii) how the research was undertaken to allow assessment of the quality and relevance of the studies in addressing the review question; (iii) the results of each study so that these can be synthesised to answer the review question.

The information is usually coded into a data collection system using some kind of technology that facilitates information storage and analysis (Brunton et al. 2017b ) such as the EPPI-Centre’s bespoke systematic review software EPPI Reviewer. Footnote 3 Decisions about which information to record will be made by the review team based on the review question and conceptual framework. For example, a systematic review about the relationship between school size and student outcomes collected data from the primary studies about each schools funding, students, teachers and school organisational structure as well as about the research methods used in the study (Newman et al. 2006 ). The information coded about the methods used in the research will vary depending on the type of research included and the approach that will be used to assess the quality and relevance of the studies (see the next section for further discussion of this point).

Similarly, the information recorded as ‘results’ of the individual studies will vary depending on the type of research that has been included and the approach to synthesis that will be used. Studies investigating the impact of educational interventions using statistical meta-analysis as a synthesis technique will require all of the data necessary to calculate effect sizes to be recorded from each study (see the section on synthesis below for further detail on this point). However, even in this type of study there will be multiple data that can be considered to be ‘results’ and so which data needs to be recorded from studies will need to be carefully specified so that recording is consistent across studies

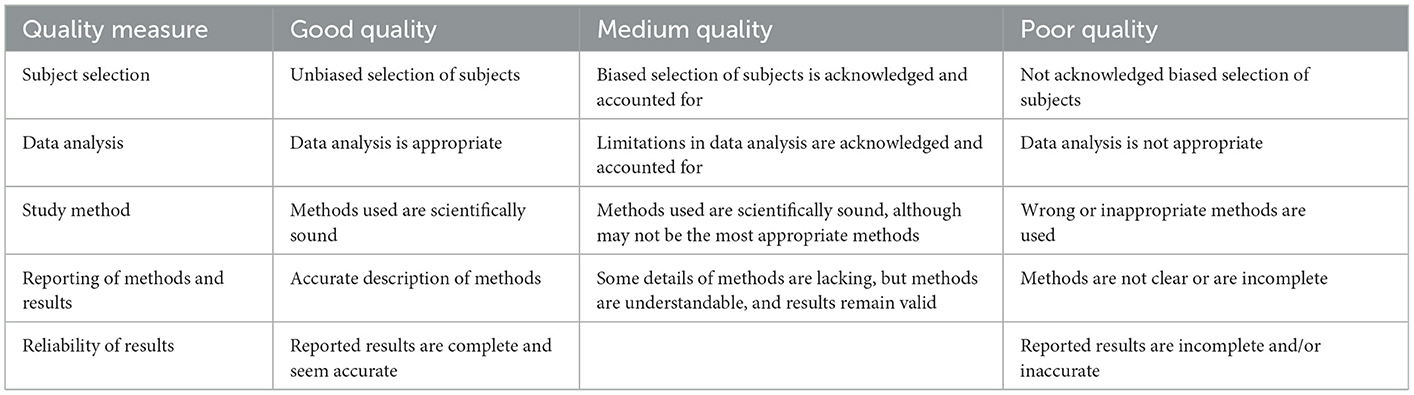

3.6 Appraising the Quality of Studies

Methods are reinvented every time they are used to accommodate the real world of research practice (Sandelowski et al. 2012 ). The researcher undertaking a primary research study has attempted to design and execute a study that addresses the research question as rigorously as possible within the parameters of their resources, understanding, and context. Given the complexity of this task, the contested views about research methods and the inconsistency of research terminology, reviewers will need to make their own judgements about the quality of the any individual piece of research included in their review. From this perspective, it is evident that using a simple criteria, such as ‘published in a peer reviewed journal’ as a sole indicator of quality, is not likely to be an adequate basis for considering the quality and relevance of a study for a particular systematic review.

In the context of systematic reviews this assessment of quality is often referred to as Critical Appraisal (Petticrew and Roberts 2005 ). There is considerable variation in what is done during critical appraisal: which dimensions of study design and methods are considered; the particular issues that are considered under each dimension; the criteria used to make judgements about these issues and the cut off points used for these criteria (Oancea and Furlong 2007 ). There is also variation in whether the quality assessment judgement is used for excluding studies or weighting them in analysis and when in the process judgements are made.

There are broadly three elements that are considered in critical appraisal: the appropriateness of the study design in the context of the review question, the quality of the execution of the study methods and the study’s relevance to the review question (Gough 2007 ). Distinguishing study design from execution recognises that whilst a particular design may be viewed as more appropriate for a study it also needs to be well executed to achieve the rigour or trustworthiness attributed to the design. Study relevance is achieved by the review selection criteria but assessing the degree of relevance recognises that some studies may be less relevant than others due to differences in, for example, the characteristics of the settings or the ways that variables are measured.

The assessment of study quality is a contested and much debated issue in all research fields. Many published scales are available for assessing study quality. Each incorporates criteria relevant to the research design being evaluated. Quality scales for studies investigating the impact of interventions using (quasi) experimental research designs tend to emphasis establishing descriptive causality through minimising the effects of bias (for detailed discussion of issues associated with assessing study quality in this tradition see Waddington et al. 2017 ). Quality scales for appraising qualitative research tend to focus on the extent to which the study is authentic in reflecting on the meaning of the data (for detailed discussion of the issues associated with assessing study quality in this tradition see Carroll and Booth 2015 ).

3.7 Synthesis

A synthesis is more than a list of findings from the included studies. It is an attempt to integrate the information from the individual studies to produce a ‘better’ answer to the review question than is provided by the individual studies. Each stage of the review contributes toward the synthesis and so decisions made in earlier stages of the review shape the possibilities for synthesis. All types of synthesis involve some kind of data transformation that is achieved through common analytic steps: searching for patterns in data; Checking the quality of the synthesis; Integrating data to answer the review question (Thomas et al. 2012 ). The techniques used to achieve these vary for different types of synthesis and may appear more or less evident as distinct steps.

Statistical meta-analysis is an aggregative synthesis approach in which the outcome results from individual studies are transformed into a standardized, scale free, common metric and combined to produce a single pooled weighted estimate of effect size and direction. There are a number of different metrics of effect size, selection of which is principally determined by the structure of outcome data in the primary studies as either continuous or dichotomous. Outcome data with a dichotomous structure can be transformed into Odds Ratios (OR), Absolute Risk Ratios (ARR) or Relative Risk Ratios (RRR) (for detailed discussion of dichotomous outcome effect sizes see Altman 1991 ). More commonly seen in education research, outcome data with a continuous structure can be translated into Standardised Mean Differences (SMD) (Fitz-Gibbon 1984 ). At its most straightforward effect size calculation is simple arithmetic. However given the variety of analysis methods used and the inconsistency of reporting in primary studies it is also possible to calculate effect sizes using more complex transformation formulae (for detailed instructions on calculating effect sizes from a wide variety of data presentations see Lipsey and Wilson 2000 ).

The combination of individual effect sizes uses statistical procedures in which weighting is given to the effect sizes from the individual studies based on different assumptions about the causes of variance and this requires the use of statistical software. Statistical measures of heterogeneity produced as part of the meta-analysis are used to both explore patterns in the data and to assess the quality of the synthesis (Thomas et al. 2017a ).

In configurative synthesis the different kinds of text about individual studies and their results are meshed and linked to produce patterns in the data, explore different configurations of the data and to produce new synthetic accounts of the phenomena under investigation. The results from the individual studies are translated into and across each other, searching for areas of commonality and refutation. The specific techniques used are derived from the techniques used in primary research in this tradition. They include reading and re-reading, descriptive and analytical coding, the development of themes, constant comparison, negative case analysis and iteration with theory (Thomas et al. 2017b ).

4 Variation in Review Structures

All research requires time and resources and systematic reviews are no exception. There is always concern to use resources as efficiently as possible. For these reasons there is a continuing interest in how reviews can be carried out more quickly using fewer resources. A key issue is the basis for considering a review to be systematic. Any definitions are clearly open to interpretation. Any review can be argued to be insufficiently rigorous and explicit in method in any part of the review process. To assist reviewers in being rigorous, reporting standards and appraisal tools are being developed to assess what is required in different types of review (Lockwood and Geum Oh 2017 ) but these are also the subject of debate and disagreement.

In addition to the term ‘systematic review’ other terms are used to denote the outputs of systematic review processes. Some use the term ‘scoping review’ for a quick review that does not follow a fully systematic process. This term is also used by others (for example, Arksey and O’Malley 2005 ) to denote ‘systematic maps’ that describe the nature of a research field rather than synthesise findings. A ‘quick review’ type of scoping review may also be used as preliminary work to inform a fuller systematic review. Another term used is ‘rapid evidence assessment’. This term is usually used when systematic review needs to be undertaken quickly and in order to do this the methods of review are employed in a more minimal than usual way. For example, by more limited searching. Where such ‘shortcuts’ are taken there may be some loss of rigour, breadth and/or depth (Abrami et al. 2010 ; Thomas et al. 2013 ).

Another development has seen the emergence of the concept of ‘living reviews’, which do not have a fixed end point but are updated as new relevant primary studies are produced. Many review teams hope that their review will be updated over time, but what is different about living reviews is that it is built into the system from the start as an on-going developmental process. This means that the distribution of review effort is quite different to a standard systematic review, being a continuous lower-level effort spread over a longer time period, rather than the shorter bursts of intensive effort that characterise a review with periodic updates (Elliott et al. 2014 ).

4.1 Systematic Maps and Syntheses

One potentially useful aspect of reviewing the literature systematically is that it is possible to gain an understanding of the breadth, purpose and extent of research activity about a phenomenon. Reviewers can be more informed about how research on the phenomenon has been constructed and focused. This type of reviewing is known as ‘mapping’ (see for example, Peersman 1996 ; Gough et al. 2003 ). The aspects of the studies that are described in a map will depend on what is of most interest to those undertaking the review. This might include information such as topic focus, conceptual approach, method, aims, authors, location and context. The boundaries and purposes of a map are determined by decisions made regarding the breadth and depth of the review, which are informed by and reflected in the review question and selection criteria.

Maps can also be a useful stage in a systematic review where study findings are synthesised as well. Most synthesis reviews implicitly or explicitly include some sort of map in that they describe the nature of the relevant studies that they have identified. An explicit map is likely to be more detailed and can be used to inform the synthesis stage of a review. It can provide more information on the individual and grouped studies and thus also provide insights to help inform choices about the focus and strategy to be used in a subsequent synthesis.

4.2 Mixed Methods, Mixed Research Synthesis Reviews

Where studies included in a review consist of more than one type of study design, there may also be different types of data. These different types of studies and data can be analysed together in an integrated design or segregated and analysed separately (Sandelowski et al. 2012 ). In a segregated design, two or more separate sub-reviews are undertaken simultaneously to address different aspects of the same review question and are then compared with one another.

Such ‘mixed methods’ and ‘multiple component’ reviews are usually necessary when there are multiple layers of review question or when one study design alone would be insufficient to answer the question(s) adequately. The reviews are usually required, to have both breadth and depth. In doing so they can investigate a greater extent of the research problem than would be the case in a more focussed single method review. As they are major undertakings, containing what would normally be considered the work of multiple systematic reviews, they are demanding of time and resources and cannot be conducted quickly.

4.3 Reviews of Reviews

Systematic reviews of primary research are secondary levels of research analysis. A review of reviews (sometimes called ‘overviews’ or ‘umbrella’ reviews) is a tertiary level of analysis. It is a systematic map and/or synthesis of previous reviews. The ‘data’ for reviews of reviews are previous reviews rather than primary research studies (see for example Newman et al. ( 2018 ). Some review of reviews use previous reviews to combine both primary research data and synthesis data. It is also possible to have hybrid review models consisting of a review of reviews and then new systematic reviews of primary studies to fill in gaps in coverage where there is not an existing review (Caird et al. 2015 ). Reviews of reviews can be an efficient method for examining previous research. However, this approach is still comparatively novel and questions remain about the appropriate methodology. For example, care is required when assessing the way in which the source systematic reviews identified and selected data for inclusion, assessed study quality and to assess the overlap between the individual reviews (Aromataris et al. 2015 ).

5 Other Types of Research Based Review Structures

This chapter so far has presented a process or method that is shared by many different approaches within the family of systematic review approaches, notwithstanding differences in review question and types of study that are included as evidence. This is a helpful heuristic device for designing and reading systematic reviews. However, it is the case that there are some review approaches that also claim to use a research based review approach but that do not claim to be systematic reviews and or do not conform with the description of processes that we have given above at all or in part at least.

5.1 Realist Synthesis Reviews

Realist synthesis is a member of the theory-based school of evaluation (Pawson 2002 ). This means that it is underpinned by a ‘generative’ understanding of causation, which holds that, to infer a causal outcome/relationship between an intervention (e.g. a training programme) and an outcome (O) of interest (e.g. unemployment), one needs to understand the underlying mechanisms (M) that connect them and the context (C) in which the relationship occurs (e.g. the characteristics of both the subjects and the programme locality). The interest of this approach (and also of other theory driven reviews) is not simply which interventions work, but which mechanisms work in which context. Rather than identifying replications of the same intervention, the reviews adopt an investigative stance and identify different contexts within which the same underlying mechanism is operating.

Realist synthesis is concerned with hypothesising, testing and refining such context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations. Based on the premise that programmes work in limited circumstances, the discovery of these conditions becomes the main task of realist synthesis. The overall intention is to first create an abstract model (based on the CMO configurations) of how and why programmes work and then to test this empirically against the research evidence. Thus, the unit of analysis in a realist synthesis is the programme mechanism, and this mechanism is the basis of the search. This means that a realist synthesis aims to identify different situations in which the same programme mechanism has been attempted. Integrative Reviewing, which is aligned to the Critical Realist tradition, follows a similar approach and methods (Jones-Devitt et al. 2017 ).

5.2 Critical Interpretive Synthesis (CIS)

Critical Interpretive Synthesis (CIS) (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006 ) takes a position that there is an explicit role for the ‘authorial’ (reviewer’s) voice in the review. The approach is derived from a distinctive tradition within qualitative enquiry and draws on some of the tenets of grounded theory in order to support explicitly the process of theory generation. In practice, this is operationalised in its inductive approach to searching and to developing the review question as part of the review process, its rejection of a ‘staged’ approach to reviewing and embracing the concept of theoretical sampling in order to select studies for inclusion. When assessing the quality of studies CIS prioritises relevance and theoretical contribution over research methods. In particular, a critical approach to reading the literature is fundamental in terms of contextualising findings within an analysis of the research traditions or theoretical assumptions of the studies included.

5.3 Meta-Narrative Reviews

Meta-narrative reviews, like critical interpretative synthesis, place centre-stage the importance of understanding the literature critically and understanding differences between research studies as possibly being due to differences between their underlying research traditions (Greenhalgh et al. 2005 ). This means that each piece of research is located (and, when appropriate, aggregated) within its own research tradition and the development of knowledge is traced (configured) through time and across paradigms. Rather than the individual study, the ‘unit of analysis’ is the unfolding ‘storyline’ of a research tradition over time’ (Greenhalgh et al. 2005 ).

6 Conclusions

This chapter has briefly described the methods, application and different perspectives in the family of systematic review approaches. We have emphasized the many ways in which systematic reviews can vary. This variation links to different research aims and review questions. But also to the different assumptions made by reviewers. These assumptions derive from different understandings of research paradigms and methods and from the personal, political perspectives they bring to their research practice. Although there are a variety of possible types of systematic reviews, a distinction in the extent that reviews follow an aggregative or configuring synthesis logic is useful for understanding variations in review approaches and methods. It can help clarify the ways in which reviews vary in the nature of their questions, concepts, procedures, inference and impact. Systematic review approaches continue to evolve alongside critical debate about the merits of various review approaches (systematic or otherwise). So there are many ways in which educational researchers can use and engage with systematic review methods to increase knowledge and understanding in the field of education.

https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/

https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/teaching-learning-toolkit

https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=2914

Abrami, P. C. Borokhovski, E. Bernard, R. M. Wade, CA. Tamim, R. Persson, T. Bethel, E. C. Hanz, K. & Surkes, M. A. (2010). Issues in conducting and disseminating brief reviews of evidence. Evidence & Policy , 6 (3), 371–389.

Google Scholar

Altman, D.G. (1991) Practical statistics for medical research . London: Chapman and Hall.

Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework, International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 8 (1), 19–32,

Article Google Scholar

Aromataris, E. Fernandez, R. Godfrey, C. Holly, C. Khalil, H. Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare , 13 .

Barnett-Page, E. & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review, BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9 (59), https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 .

Brunton, G., Stansfield, C., Caird, J. & Thomas, J. (2017a). Finding relevant studies. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd edition, pp. 93–132). London: Sage.

Brunton, J., Graziosi, S., & Thomas, J. (2017b). Tools and techniques for information management. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd edition, pp. 154–180), London: Sage.

Carroll, C. & Booth, A. (2015). Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: Is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Research Synthesis Methods 6 (2), 149–154.

Caird, J. Sutcliffe, K. Kwan, I. Dickson, K. & Thomas, J. (2015). Mediating policy-relevant evidence at speed: are systematic reviews of systematic reviews a useful approach? Evidence & Policy, 11 (1), 81–97.

Chow, J. & Eckholm, E. (2018). Do published studies yield larger effect sizes than unpublished studies in education and special education? A meta-review. Educational Psychology Review 30 (3), 727–744.

Dickson, K., Vigurs, C. & Newman, M. (2013). Youth work a systematic map of the literature . Dublin: Dept of Government Affairs.

Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwa, S., Annandale, E. Arthur, A., Harvey, J., Hsu, R., Katbamna, S., Olsen, R., Smith, L., Riley R., & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology 6:35 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 .

Elliott, J. H., Turner, T., Clavisi, O., Thomas, J., Higgins, J. P. T., Mavergames, C. & Gruen, R. L. (2014). Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Medicine, 11 (2): e1001603. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001603 .

Fitz-Gibbon, C.T. (1984) Meta-analysis: an explication. British Educational Research Journal , 10 (2), 135–144.

Gough, D. (2007). Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research Papers in Education , 22 (2), 213–228.

Gough, D., Thomas, J. & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1( 28).

Gough, D., Kiwan, D., Sutcliffe, K., Simpson, D. & Houghton, N. (2003). A systematic map and synthesis review of the effectiveness of personal development planning for improving student learning. In: Research Evidence in Education Library. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

Gough, D., Oliver, S. & Thomas, J. (2017). Introducing systematic reviews. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd edition, pp. 1–18). London: Sage.

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., Kyriakidou, O. & Peacock, R. (2005). Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 61 (2), 417–430.

Hargreaves, D. (1996). Teaching as a research based profession: possibilities and prospects . Teacher Training Agency Annual Lecture. Retrieved from https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=2082 .

Hart, C. (2018). Doing a literature review: releasing the research imagination . London. SAGE.

Jones-Devitt, S. Austen, L. & Parkin H. J. (2017). Integrative reviewing for exploring complex phenomena. Social Research Update . Issue 66.

Kugley, S., Wade, A., Thomas, J., Mahood, Q., Klint Jørgensen, A. M., Hammerstrøm, K., & Sathe, N. (2015). Searching for studies: A guide to information retrieval for Campbell Systematic Reviews . Campbell Method Guides 2016:1 ( http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/images/Campbell_Methods_Guides_Information_Retrieval.pdf ).

Lipsey, M.W., & Wilson, D. B. (2000). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Lockwood, C. & Geum Oh, E. (2017). Systematic reviews: guidelines, tools and checklists for authors. Nursing & Health Sciences, 19, 273–277.

Nelson, J. & Campbell, C. (2017). Evidence-informed practice in education: meanings and applications. Educational Research, 59 (2), 127–135.

Newman, M., Garrett, Z., Elbourne, D., Bradley, S., Nodenc, P., Taylor, J. & West, A. (2006). Does secondary school size make a difference? A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 1 (1), 41–60.

Newman, M. (2008). High quality randomized experimental research evidence: Necessary but not sufficient for effective education policy. Psychology of Education Review, 32 (2), 14–16.

Newman, M., Reeves, S. & Fletcher, S. (2018). A critical analysis of evidence about the impacts of faculty development in systematic reviews: a systematic rapid evidence assessment. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 38 (2), 137–144.

Noblit, G. W. & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Oancea, A. & Furlong, J. (2007). Expressions of excellence and the assessment of applied and practice‐based research. Research Papers in Education 22 .

O’Mara-Eves, A., Thomas, J., McNaught, J., Miwa, M., & Ananiadou, S. (2015). Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Systematic Reviews 4 (1): 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-5 .

Pawson, R. (2002). Evidence-based policy: the promise of “Realist Synthesis”. Evaluation, 8 (3), 340–358.

Peersman, G. (1996). A descriptive mapping of health promotion studies in young people, EPPI Research Report. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

Petticrew, M. & Roberts, H. (2005). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide . London: Wiley.

Sandelowski, M., Voils, C. I., Leeman, J. & Crandell, J. L. (2012). Mapping the mixed methods-mixed research synthesis terrain. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6 (4), 317–331.

Smyth, R. (2004). Exploring the usefulness of a conceptual framework as a research tool: A researcher’s reflections. Issues in Educational Research, 14 .

Thomas, J., Harden, A. & Newman, M. (2012). Synthesis: combining results systematically and appropriately. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (pp. 66–82). London: Sage.

Thomas, J., Newman, M. & Oliver, S. (2013). Rapid evidence assessments of research to inform social policy: taking stock and moving forward. Evidence and Policy, 9 (1), 5–27.

Thomas, J., O’Mara-Eves, A., Kneale, D. & Shemilt, I. (2017a). Synthesis methods for combining and configuring quantitative data. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An Introduction to Systematic Reviews (2nd edition, pp. 211–250). London: Sage.

Thomas, J., O’Mara-Eves, A., Harden, A. & Newman, M. (2017b). Synthesis methods for combining and configuring textual or mixed methods data. In D. Gough, S. Oliver & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd edition, pp. 181–211), London: Sage.

Tsafnat, G., Dunn, A. G., Glasziou, P. & Coiera, E. (2013). The automation of systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 345 (7891), doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f139 .

Torgerson, C. (2003). Systematic reviews . London. Continuum.

Waddington, H., Aloe, A. M., Becker, B. J., Djimeu, E. W., Hombrados, J. G., Tugwell, P., Wells, G. & Reeves, B. (2017). Quasi-experimental study designs series—paper 6: risk of bias assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 89 , 43–52.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Education, University College London, England, UK

Mark Newman & David Gough

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mark Newman .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Oldenburg, Germany

Olaf Zawacki-Richter

Essen, Germany

Michael Kerres

Svenja Bedenlier

Melissa Bond

Katja Buntins

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Newman, M., Gough, D. (2020). Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application. In: Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K. (eds) Systematic Reviews in Educational Research. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7_1

Published : 22 November 2019

Publisher Name : Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-27601-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-27602-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses

Affiliations.

- 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom.

- 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected].

- PMID: 30089228

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Keywords: evidence; guide; meta-analysis; meta-synthesis; narrative; systematic review; theory.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- The future of Cochrane Neonatal. Soll RF, Ovelman C, McGuire W. Soll RF, et al. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Nov;150:105191. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105191. Epub 2020 Sep 12. Early Hum Dev. 2020. PMID: 33036834

- A Primer on Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Nguyen NH, Singh S. Nguyen NH, et al. Semin Liver Dis. 2018 May;38(2):103-111. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1655776. Epub 2018 Jun 5. Semin Liver Dis. 2018. PMID: 29871017 Review.

- Publication Bias and Nonreporting Found in Majority of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses in Anesthesiology Journals. Hedin RJ, Umberham BA, Detweiler BN, Kollmorgen L, Vassar M. Hedin RJ, et al. Anesth Analg. 2016 Oct;123(4):1018-25. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001452. Anesth Analg. 2016. PMID: 27537925 Review.

- Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Aromataris E, et al. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015 Sep;13(3):132-40. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015. PMID: 26360830

- RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. Wong G, et al. BMC Med. 2013 Jan 29;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-20. BMC Med. 2013. PMID: 23360661 Free PMC article.

- Surveillance of Occupational Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds at Gas Stations: A Scoping Review Protocol. Mendes TMC, Soares JP, Salvador PTCO, Castro JL. Mendes TMC, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024 Apr 23;21(5):518. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21050518. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024. PMID: 38791733 Free PMC article. Review.

- Association between poor sleep and mental health issues in Indigenous communities across the globe: a systematic review. Fernandez DR, Lee R, Tran N, Jabran DS, King S, McDaid L. Fernandez DR, et al. Sleep Adv. 2024 May 2;5(1):zpae028. doi: 10.1093/sleepadvances/zpae028. eCollection 2024. Sleep Adv. 2024. PMID: 38721053 Free PMC article.

- Barriers to ethical treatment of patients in clinical environments: A systematic narrative review. Dehkordi FG, Torabizadeh C, Rakhshan M, Vizeshfar F. Dehkordi FG, et al. Health Sci Rep. 2024 May 1;7(5):e2008. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.2008. eCollection 2024 May. Health Sci Rep. 2024. PMID: 38698790 Free PMC article.

- Studying Adherence to Reporting Standards in Kinesiology: A Post-publication Peer Review Brief Report. Watson NM, Thomas JD. Watson NM, et al. Int J Exerc Sci. 2024 Jan 1;17(7):25-37. eCollection 2024. Int J Exerc Sci. 2024. PMID: 38666001 Free PMC article.

- Evidence for Infant-directed Speech Preference Is Consistent Across Large-scale, Multi-site Replication and Meta-analysis. Zettersten M, Cox C, Bergmann C, Tsui ASM, Soderstrom M, Mayor J, Lundwall RA, Lewis M, Kosie JE, Kartushina N, Fusaroli R, Frank MC, Byers-Heinlein K, Black AK, Mathur MB. Zettersten M, et al. Open Mind (Camb). 2024 Apr 3;8:439-461. doi: 10.1162/opmi_a_00134. eCollection 2024. Open Mind (Camb). 2024. PMID: 38665547 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ingenta plc

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 13 October 2014

Considering methodological options for reviews of theory: illustrated by a review of theories linking income and health

- Mhairi Campbell 1 ,

- Matt Egan 2 ,

- Theo Lorenc 3 ,

- Lyndal Bond 4 ,

- Frank Popham 1 ,

- Candida Fenton 1 &

- Michaela Benzeval 1 , 5

Systematic Reviews volume 3 , Article number: 114 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

39 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Review of theory is an area of growing methodological advancement. Theoretical reviews are particularly useful where the literature is complex, multi-discipline, or contested. It has been suggested that adopting methods from systematic reviews may help address these challenges. However, the methodological approaches to reviews of theory, including the degree to which systematic review methods can be incorporated, have received little discussion in the literature. We recently employed systematic review methods in a review of theories about the causal relationship between income and health.

This article discusses some of the methodological issues we considered in developing the review and offers lessons learnt from our experiences. It examines the stages of a systematic review in relation to how they could be adapted for a review of theory. The issues arising and the approaches taken in the review of theories in income and health are considered, drawing on the approaches of other reviews of theory.

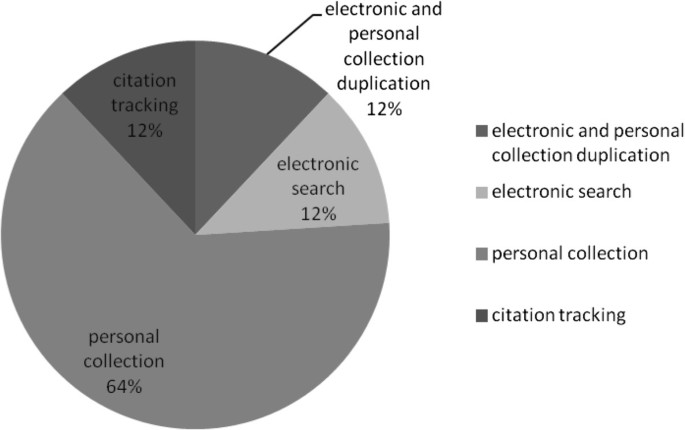

Different approaches to searching were required, including electronic and manual searches, and electronic citation tracking to follow the development of theories. Determining inclusion criteria was an iterative process to ensure that inclusion criteria were specific enough to make the review practical and focused, but not so narrow that key literature was excluded. Involving subject specialists was valuable in the literature searches to ensure principal papers were identified and during the inductive approaches used in synthesis of theories to provide detailed understanding of how theories related to another. Reviews of theory are likely to involve iterations and inductive processes throughout, and some of the concepts and techniques that have been developed for qualitative evidence synthesis can be usefully translated to theoretical reviews of this kind.

Conclusions

It may be useful at the outset of a review of theory to consider whether the key aim of the review is to scope out theories relating to a particular issue; to conduct in-depth analysis of key theoretical works with the aim of developing new, overarching theories and interpretations; or to combine both these processes in the review. This can help decide the most appropriate methodological approach to take at particular stages of the review.

Peer Review reports

Theory is fundamental to research and rational thought. The term ‘theory’ has been variously defined, and is frequently used without definition, but often refers to an explanatory framework for observations. In science, theories generally purport to explain empirical observations and form the basis on which testable hypotheses are generated to provide support for, or challenge, the theory. Gorelick defines theory as ‘the creative, inductive, and synthetic discipline of forming hypotheses’ [ 1 ], p. 7. Popper defined a scientific theory as one that is experimentally falsifiable [ 2 ]. Merton has contrasted ‘grand’ social theories such as Marxism, functionalism, and post-modernism with ‘middle-range theories’ that start with an empirical phenomenon and abstract from it to create general statements that can be verified by data [ 3 ]. Mid-range theories are dominant within empirical and scientific approaches to research. Gough usefully categorises such research as aiming to generate, explore, or test theories. Of particular importance in health literature are studies which include theories about cause and effect; such studies may test these theories in a ‘black box’ way or attempt to generate, explore, and test more clearly articulated causal-pathway frameworks, such as those presented in logic models [ 4 ]. For this discussion, the terms ‘causal pathway’, ‘causal maps’, and ‘logic model’ refer to qualitative models used to identify key concepts and the links between them [ 5 ].

Within the health sciences, it is widely understood that individual and population health are influenced by a wide array of interconnecting factors, so theoretical models can be complex and, at times, contested [ 6 ]. However, different disciplines approach such research in different ways and are not always well connected. Reviews of theory may aid our attempts to navigate a diverse literature and potentially lead to insights into how factors relate to one another [ 6 – 9 ]. Theory reviews could have one or more of the following aims: identifying and mapping a comprehensive range of relevant theories; assessing which theories have become influential and which have been, or have become over time, largely overlooked; and integrating complementary theories and facilitating the analysis and synthesis of theories into more generalised or abstract ‘meta-theories’. By focusing on theory, rather than diverse empirical studies, reviews can be useful devices to describe complex topics across different disciplines and inform policy debates.

The purpose of this article is to consider the ways in which theoretical reviews might be conducted and in particular the role of systematic approaches within this. It illustrates the discussion by drawing on the approach of a recent theoretical review the authors undertook of income and health [ 10 ]. It discusses some of the methodological challenges and options that reviewers may face when planning and conducting reviews that focus on theoretical literature. We think the discussion will be particularly relevant to reviewers considering the degree to which they might attempt to use and adapt methods commonly associated with systematic reviews, which tend to have been developed around reviews of empirical research and thus not specifically designed to assess descriptions of theories underpinning research. We will discuss the extent to which methods developed and used for reviews of empirical research may, or indeed may not, be usefully adapted to meet the challenges posed when reviewing theories on the phenomena of interest. In particular, we will discuss some of the methods we (the authors) employed when conducting our own recent review of theories of income and health [ 10 ]. Reviews of theory are part of a growing methodological advancement, and we think this would be an opportune time to contribute lessons learnt from our project and others and discuss some of the methodological considerations that inform such a review. Some of our reflections are based on the methods we employed in our review; others result from critical thinking and discussions that took place following the review’s completion.

Below, we outline general approaches in the literature to conducting reviews of theories. We then describe the broad principles of our approach before providing a detailed summary of each stage of the review and the way in which we incorporated systematic approaches into them. We examine how this contributed to our understanding of the literature on income and health and reflect on the value of this approach.

Existing approaches to reviews of theory

There is often substantial variation in the methodologies of reviews that consider theory. Some take the form of traditional literature reviews, often reliant on expert knowledge in the relevant field. Such expert knowledge allows in-depth understanding of theories and links between them. However, it can be limited to the disciplinary perspective of the reviewer, not necessarily identifying less popular or emerging theories, and cannot provide a sense of the extent to which different theories are employed in the literature. Given these limitations, some reviewers of theory have employed methodologies associated with systematic reviews such as comprehensive searches and clear criteria for including, appraising, and synthesising the literature to provide a more comprehensive picture [ 11 , 12 ]. Reviews of theory are thus rather different to reviews of empirical data. In particular, the primary goal of using systematic methods in the latter case is to minimise bias. In theory reviews—where it is not even clear that the concept of ‘bias’ is substantively meaningful—their main contribution may be more in ‘opening up’ reviewers’ thinking about the research topic and widening the potential space of hypothesis generation.

Often reviews of theory are conducted to assist reviewers involved in carrying out systematic reviews of intervention effectiveness. Realist review [ 13 , 14 ] is currently a key area of methodological development around the integration of theory into reviews of interventions. Realist reviews aim to draw out and test ‘programme theories’ about the causal pathways through which interventions work, in order to bring together evidence on effectiveness with data on implementation and context. In some cases, theory reviews may have relatively narrow inclusion criteria tied to theories about a specific intervention. However, narrow criteria do not necessarily lead to small-scale review. Two systematic reviews of theory conducted in relation to larger reviews are Baxter and Allmark’s [ 12 ] review of chest pain and medical assistance and Bonell et al.’s [ 11 ] review of theories on school environment and health: the former has a narrower research question with a search result of around 100 papers, but the latter entailed screening more than 62,000 papers.

A recent systematic review of interventions on crime, fear of crime, health, and the environment was preceded by a mapping broad review of theories that attempted to explain associations between these factors [ 5 ]. The crime review used a pragmatic approach to searching and selecting literature and did not attempt to provide a comprehensive systematic review of all theories related to the topic. Rather, the theory review aimed to construct a coherent framework for integrating relevant theories, in order to contextualise and better understand the empirical data.

The income and health review of theory

We conducted a review of theories about causal relationships between income and health (see Additional file 1 for brief description). Given the wide-ranging literatures across disciplines, and the contested nature of many debates, we felt that a systematic approach to the review would help shed light on the range of casual paths that had been posited. Our intention was to gain some of the benefits of applying systematic review methods to a review of theory, such as clarity, comprehensiveness, and transparency. By making the literature search as systematic and transparent as possible, a review can extend beyond researcher knowledge and disciplinary background [ 15 ]. Developing inclusion criteria and devising methods to uniformly capture data across included papers strengthens objectivity [ 15 ]. By the time the included papers have been assessed, it is hoped that the explicit methods used reduce subjectivity. Once the theories are gathered through the systematic searching, screening, and extracting, the interpretation of their content at the synthesis stage may be still be at risk of subjectivity.

Reviews of theory may be particularly valuable in seeking to develop a synoptic understanding of questions where a number of different disciplines overlap. In our recent review of theories describing pathways linking individual and family income to health [ 10 ], we included theories from public health, psychology, social policy, sociology, and economics, all of which have distinct traditions and vocabularies. In addition, many of the causal pathways between income and health described by these theories are long and complex. In cases such as these, syntheses of theory can help to produce new insights about complex fields by drawing together different paradigms and translating concepts between disciplines.

The techniques developed in the crime theory review were adapted by the authors of the present article for a review of theories linking income to health across the lifecourse [ 10 ]. In the income and health review, an attempt was made to incorporate more techniques from systematic reviews, including a priori inclusion criteria, comprehensive electronic searching, and standardised data extraction. These methods were employed to capture theories from literature in disciplines with which we may have been less familiar. The methods used for our review are indebted to those developed by realist reviewers. However, our review focused less specifically on evaluating mid-range theories of the mechanisms and contexts of interventions and more on mapping and synthesising the whole landscape of theories around income, health, and the lifecourse. The resulting review was a methodological hybrid including elements of the earlier crime review, drawing on seminal literature to create a framework, and more standard systematic reviews. Below, we outline key review stages, illustrated by the methods used in the income and health review of theory. Challenges faced and tactics to address, these are described. The aim was to generate guidance and discussion of methods that may be useful when planning and conducting a review of theory.

Results and discussion

Developing the research question.

An explicitly stated research question is a characteristic of systematic reviews that can be adopted for reviews of theory. The question should be designed following consideration of what the end users will find useful, so consultations with potential end users may be part of the process [ 15 ]. As stated above, review questions can be broad or narrow in scope. A broad question may reflect the reviewers’ aim to scope out and map a wide range of theories within a subject area. The purpose of this income and health review was to use theory as a tool to support a larger programme of work exploring the importance of income and other aspects of family resources in determining a wide range of health and social outcomes. In contrast, if the aim is to identify theories relating to a specific phenomenon or intervention, then a narrow question may be more appropriate. For example, the review of theories of behaviour change in limiting gestational weight gain [ 16 ]; and in another review, Sherman et al. [ 17 ] used self regulatory theory to examine psychological adjustment among male partners in response to women’s cancer. Both these reviews of theory have a narrow topic, distinct from the broad scope of the income and health review.

Assembling the team

Guidance for conducting a systematic review recommends gathering a team that includes an experienced reviewer, a subject specialist, and an information scientist with advanced knowledge of bibliographic search strategies [ 15 ], p. 85; [ 18 ]. For theory reviews, the role of the subject specialists and the stages at which their contribution is valuable may become particularly crucial. Besides helping to ensure that key papers within the field are identified for inclusion in the review, specialists can provide a detailed understanding of how different theories came to be developed, how one theory relates to another, and where the points of controversy lie. It may be useful to have input from more than one specialist if the scope of the review is multi-disciplinary or covers a subject area that is divided by rival theoretical ‘camps’. Conducting the income and health review was aided by the team including members with experience of systematic reviews, theory reviews, and information science, as well as reviewers with backgrounds in lifecourse epidemiology, social policy, and economics. We also worked with an advisory group that included end users and researchers with a range of experience in social science research.

The degree of specialist input required will be influenced by the depth of analysis required. Reviews that aim to provide in-depth synthesis, including attempts to develop meta-theories, are likely to require greater specialist input than reviews that aim to scope the various theories in the literature. This echoes guidance for other types of review. For example, Cochrane’s Qualitative and Implementation Methods group states that greater subject expertise is required to appraise the theoretical contributions made by qualitative research compared to that required simply to include or exclude relevant evidence [ 19 ]. Hence, the most appropriate team for any particular review will depend not only on the subject matter being reviewed, but also on the degree to which the review is intended primarily to be a scoping exercise or a more specialist theoretical analysis.

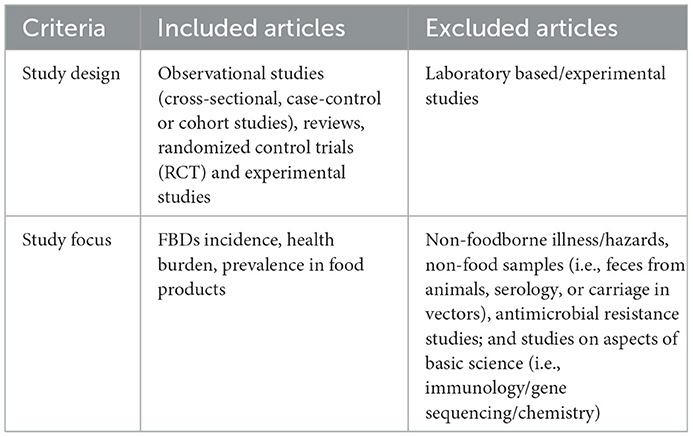

Inclusion and exclusion

A priori inclusion and exclusion criteria are a mainstay of systematic reviews, helping to guide the literature search and ensure clear focus and transparency in the selection of studies. Frameworks for developing such criteria have been developed. For example, Cochrane advocates the use of criteria that specifies population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study (PICOS) design. Qualitative reviewers have an alternative framework: sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and research type (SPIDER) [ 20 ]. No comparable frameworks currently exist for theory reviews. When conducting reviews of theory, the task of creating inclusion/exclusion criteria can present challenges. First, the term ‘theory’ needs to be defined with enough precision to enable reviewers to consistently filter out papers that are insufficiently theoretical. Generic definitions, such as those highlighted at the beginning of this article, are conceptually helpful, but in practice, reviewers may find themselves struggling to decide whether a text is describing a theory or a hypothesis or speculation (and wondering how crucial these distinctions might be for the review). They may also struggle to find a consistent way of distinguishing a general discussion of issues from a more fully expounded theory. The decisions that were taken of includable theory during the income and health review were guided by screening for substantial hypothesis of exposure—mechanism—outcome and study design. We found considering papers in relation to these criteria a useful tool to clarify the theory content of papers, although we would emphasise that in this particular example it is theories of cause and effect that is being examined. Reviews of alternative types of theory would require alternative criteria.

A second challenge relates to the tension between having inclusion criteria that are specific enough to make the review practical and focused, but not so specific that key literature is excluded. Although this issue is not exclusive to reviews of theory, we found that a particular problem with the income and health theory review was that some of the most widely recognised theoretical texts did not originate from literature that focused on income, health, or lifecourse (i.e. not all three of these elements simultaneously) specifically. The Black Report [ 21 ], for instance, continues to exert a huge influence on how researchers think about the causes of health inequalities, and its theoretical framework can be seen to underpin some of the literature that was relevant to our review. However, the Black Report itself generally refers to the broader concept of socio-economic status rather than more specifically to the issue of income. We did not want to exclude the theoretical framework outlined in the Black Report nor did we want to open up our inclusion criteria so that it included all theories of socio-economic status and health (to do so would have been an enormous undertaking).