- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

Major Environmental Movements in India

Last updated on April 22, 2024 by ClearIAS Team

Contemporary India experiences almost unrestricted exploitation of resources because of the lure of new consumerist lifestyles.

The balance of nature is disrupted. This has led to many conflicts in society.

In this article, we discuss the major environmental movements in India.

Table of Contents

What is an Environmental Movement?

- An environmental movement can be defined as a social or political movement, for the conservation of the environment or for the improvement of the state of the environment . The terms ‘green movement’ or ‘conservation movement’ are alternatively used to denote the same.

- The environmental movements favour the sustainable management of natural resources. The movements often stress the protection of the environment via changes in public policy . Many movements are centred on ecology, health and human rights .

- Environmental movements range from highly organized and formally institutionalized ones to radically informal activities.

- The spatial scope of various environmental movements ranges from being local to almost global.

Some of the major environmental movements in India during the period 1700 to 2000 are the following.

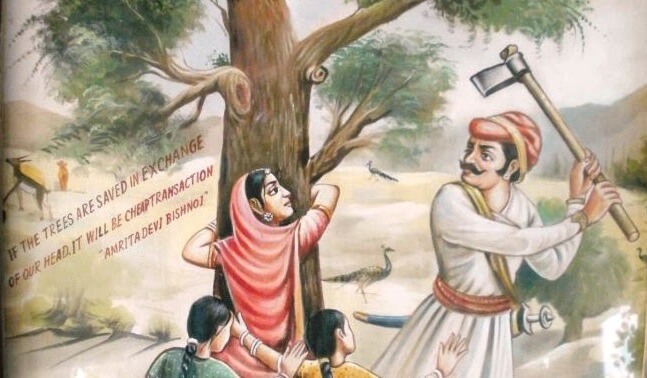

Bishnoi Movement

- Year: 1700s

- Place: Khejarli, Marwar region, Rajasthan state.

- Leaders: Amrita Devi along with Bishnoi villagers in Khejarli and surrounding villages.

- Aim: Save sacred trees from being cut down by the king’s soldiers for a new palace.

What was it all about : Amrita Devi, a female villager could not bear to witness the destruction of both her faith and the village’s sacred trees. She hugged the trees and encouraged others to do the same. 363 Bishnoi villagers were killed in this movement.

The Bishnoi tree martyrs were influenced by the teachings of Guru Maharaj Jambaji, who founded the Bishnoi faith in 1485 and set forth principles forbidding harm to trees and animals. The king who came to know about these events rushed to the village and apologized, ordering the soldiers to cease logging operations. Soon afterwards, the maharajah designated the Bishnoi state as a protected area, forbidding harm to trees and animals. This legislation still exists today in the region.

Chipko Movement

- Place: In Chamoli district and later in Tehri-Garhwal district of Uttarakhand.

- Leaders: Sundarlal Bahuguna, Gaura Devi, Sudesha Devi, Bachni Devi, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Govind Singh Rawat, Dhoom Singh Negi, Shamsher Singh Bisht and Ghanasyam Raturi.

- Aim: The main objective was to protect the trees on the Himalayan slopes from the axes of contractors of the forest.

What was it all about : Mr. Bahuguna enlightened the villagers by conveying the importance of trees in the environment which check the erosion of soil, cause rains and provide pure air. The women of Advani village of Tehri-Garhwal tied the sacred thread around the trunks of trees and they hugged the trees, hence it was called the ‘Chipko Movement’ or ‘hug the tree movement’.

The main demand of the people in these protests was that the benefits of the forests (especially the right to fodder) should go to local people. The Chipko movement gathered momentum in 1978 when the women faced police firings and other tortures.

The then state Chief Minister, Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna set up a committee to look into the matter, which eventually ruled in favour of the villagers. This became a turning point in the history of eco-development struggles in the region and around the world.

Save Silent Valley Movement

- Place: Silent Valley, an evergreen tropical forest in the Palakkad district of Kerala, India.

- Leaders: The Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP) an NGO, and the poet-activist Sughathakumari played an important role in the Silent Valley protests.

- Aim: To protect the Silent Valley, the moist evergreen forest from being destroyed by a hydroelectric project.

What was it all about: The Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) proposed a hydroelectric dam across the Kunthipuzha River that runs through Silent Valley. In February 1973, the Planning Commission approved the project at a cost of about Rs 25 crores. Many feared that the project would submerge 8.3 sq km of untouched moist evergreen forest. Several NGOs strongly opposed the project and urged the government to abandon it.

In January 1981, bowing to unrelenting public pressure, Indira Gandhi declared that Silent Valley will be protected. In June 1983 the Center re-examined the issue through a commission chaired by Prof. M.G.K. Menon. In November 1983 the Silent Valley Hydroelectric Project was called off. In 1985, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi formally inaugurated the Silent Valley National Park.

Jungle Bachao Andholan

- Place: Singhbhum district of Bihar

- Leaders: The tribals of Singhbhum.

- Aim: Against the government’s decision to replace the natural sal forest with Teak .

What was it all about: The tribals of the Singhbhum district of Bihar started the protest when the government decided to replace the natural sal forests with the highly-priced teak. This move was called by many “Greed Game Political Populism”. Later this movement spread to Jharkhand and Orissa.

Appiko Movement

- Place: Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts of Karnataka State

- Leaders: Appiko’s greatest strengths lie in it being neither driven by a personality nor having been formally institutionalised. However, it does have a facilitator in Pandurang Hegde. He helped launch the movement in 1983.

- Aim: Against the felling and commercialization of natural forest and the ruin of ancient livelihood.

What was it all about: It can be said that the Appiko movement is the southern version of the Chipko movement. The Appiko Movement was locally known as “Appiko Chaluvali”. The locals embraced the trees which were to be cut by contractors of the forest department. The Appiko movement used various techniques to raise awareness such as foot marches in the interior forest, slide shows, folk dances, street plays etc.

The second area of the movement’s work was to promote afforestation on denuded lands. The movement later focused on the rational use of the ecosphere by introducing alternative energy resource to reduce pressure on the forest. The movement became a success. The current status of the project is – stopped.

Narmada Bachao Andholan (NBA)

- Place: Narmada River, which flows through the states of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra.

- Leaders: Medha Patker, Baba Amte, Adivasis, farmers, environmentalists and human rights activists.

- Aim: A social movement against several large dams being built across the Narmada River.

What was it all about: The movement first started as a protest for not providing proper rehabilitation and resettlement for the people who have been displaced by the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Later on, the movement turned its focus on the preservation of the environment and the eco-systems of the valley. Activists also demanded the height of the dam to be reduced to 88 m from the proposed height of 130m. World Bank withdrew from the project.

The environmental issue was taken into court. In October 2000, the Supreme Court gave a judgment approving the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam with a condition that the height of the dam could be raised to 90 m. This height is much higher than the 88 m which anti-dam activists demanded, but it is definitely lower than the proposed height of 130 m. The project is now largely financed by the state governments and market borrowings. The project is expected to be fully completed by 2025.

Although not successful, as the dam could not be prevented, the NBA has created an anti-big dam opinion in India and outside. It questioned the paradigm of development. As a democratic movement, it followed the Gandhian way 100 per cent.

Tehri Dam Conflict

- Year: 1990’s

- Place: Bhagirathi River near Tehri in Uttarakhand.

- Leaders: Sundarlal Bahuguna

- Aim: The protest was against the displacement of town inhabitants and the environmental consequence of the weak ecosystem.

Tehri Dam attracted national attention in the 1980s and the 1990s. The major objections include seismic sensitivity of the region, the submergence of forest areas along with Tehri town etc. Despite the support from other prominent leaders like Sunderlal Bahuguna, the movement has failed to gather enough popular support at the national as well as international levels.

- Appiko – The Hindu

- NBA – The Hindu

Article by: Priyanka Sunil

Aim IAS, IPS, or IFS?

About ClearIAS Team

ClearIAS is one of the most trusted learning platforms in India for UPSC preparation. Around 1 million aspirants learn from the ClearIAS every month.

Our courses and training methods are different from traditional coaching. We give special emphasis on smart work and personal mentorship. Many UPSC toppers thank ClearIAS for our role in their success.

Download the ClearIAS mobile apps now to supplement your self-study efforts with ClearIAS smart-study training.

Reader Interactions

October 16, 2016 at 12:08 am

V.v.useful info.thank u so much sir

March 20, 2017 at 3:47 pm

Happy to help

October 16, 2016 at 4:53 pm

Thank you very much clearias.com .

October 18, 2016 at 10:43 pm

Tq very much to clear IAS team Wonder ful information In brief way

June 8, 2018 at 5:57 pm

Ty very much. It was really very helpful to me

October 24, 2016 at 2:47 pm

It is a very important issue for mains.Thank you clear IAS team.

November 26, 2016 at 3:05 pm

Hi, You are providing valuable information for competitive exam’s. Here in this article you have written about “Chipko Movement” is started from Tehri Garhwal. “Chipko Movement” was started from “Reni Village” of Chamoli ditrtict, which is near “Joshimath”.

So, plz correct that.

November 26, 2016 at 4:18 pm

Thanks Udit for pointing it out. We have updated the article.

The struggle Chipko’s first battle took place in early 1973 in Chamoli district, when the villagers of Mandal, led by Bhatt and the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal (DGSM), prevented the Allahabad-based sports goods company, Symonds, from felling 14 ash trees. In Tehri Garhwal, Chipko activists led by Sunderlal Bahuguna began organising villagers from May 1977 to oppose tree-felling in the Henwal valley.

February 2, 2017 at 11:26 pm

Very Nice Sir.

July 19, 2017 at 3:34 pm

Nice ,I came to know about few things today

December 20, 2020 at 2:12 pm

Thanku sir for explaination. It really helps me

November 9, 2017 at 11:17 am

Thank you so much it helped me to do my project

November 15, 2017 at 10:47 pm

very nice information sir

November 24, 2017 at 9:40 pm

Thank you so much. Keep it up👍!

January 19, 2018 at 4:43 pm

Thank you so much You helped me project😄👍

February 28, 2018 at 7:47 am

Hello sir my name pratap I live in jajpur,odisha . One request sir in jajpur tha environment is polluted because here 17 factory are avelebul .Sir my request is save our children ….Plz sir

April 26, 2018 at 6:44 pm

Thnq for the info sir ! This is quite interesting Nd also helpful for my xam tomorrow

May 2, 2018 at 7:58 pm

Good information. Sir. I. Gained some knowledge from this

August 18, 2023 at 8:01 pm

Thank you so much for giving such a important information

May 25, 2018 at 5:13 pm

Do you have youtube channel. As the information provided by you is awesome.

May 25, 2018 at 8:11 pm

Yes. We have @clearias. You can find the link in the footer section.

June 20, 2018 at 1:31 pm

thank you so much sir.It helped me very much

February 24, 2019 at 10:08 pm

Need more information

April 27, 2019 at 7:36 pm

Thanks…

December 10, 2022 at 10:19 am

Need more information plz

June 12, 2019 at 6:47 am

Amazingly described! Helped a alot !!!! Thanks 🙂

September 14, 2019 at 2:07 pm

Thanks for your help

December 19, 2019 at 3:36 am

Yes. This is the best Topic. Wonderful

January 26, 2020 at 10:38 pm

thank you its help to me for my semister examination

April 21, 2021 at 8:41 am

Thank You So Much for helping us with the valuable content.

April 30, 2021 at 8:23 pm

Thankyou so much clerias.com. Really it is very helpful to all.

May 17, 2021 at 7:20 am

Okeh😎 It’s my pleasure

June 3, 2021 at 12:12 pm

It’s really helpful . Thank you so much 💖🖤 But Silent movement is an environmental movement in Kerala so it’s a state movement according to my text book Any way this work really awesome and helpful for my project as a referring guide THANK YOU ❤💌

July 28, 2021 at 10:08 pm

Thank you clearias.com…..you save me …this notes is very helpful for my upcoming exams thanks a lot….keep it up…..

October 7, 2021 at 11:02 am

it’s good information, nice work.

October 21, 2021 at 9:48 am

Singhbhum district is not in Bihar it is Jharkhand. If you’re mentioning before the partition of the state then you shouldn’t mention the line ” then it was spread in Jharkhand and Orissa”. Please keep your information correct.

November 23, 2021 at 8:56 am

It’s really so useful

November 27, 2021 at 9:19 pm

Excellent information ..Thankyou

May 12, 2022 at 4:14 pm

It’s really very much helpful . Thank you But Silent movement is an environmental movement Which must be going in India and Worldwide for water and wastewater treatment. Any way this work really awesome and helpful for my research as a referring guide THANK YOU 💌

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don’t lose out without playing the right game!

Follow the ClearIAS Prelims cum Mains (PCM) Integrated Approach.

Join ClearIAS PCM Course Now

UPSC Online Preparation

- Union Public Service Commission (UPSC)

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

- Indian Police Service (IPS)

- IAS Exam Eligibility

- UPSC Free Study Materials

- UPSC Exam Guidance

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Prelims

- UPSC Interview

- UPSC Toppers

- UPSC Previous Year Qns

- UPSC Age Calculator

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- About ClearIAS

- ClearIAS Programs

- ClearIAS Fee Structure

- IAS Coaching

- UPSC Coaching

- UPSC Online Coaching

- ClearIAS Blog

- Important Updates

- Announcements

- Book Review

- ClearIAS App

- Work with us

- Advertise with us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Talk to Your Mentor

Featured on

and many more...

Take ClearIAS Mock Exams: Analyse Your Progress

Analyse Your Performance and Track Your All-India Ranking

Ias/ips/ifs online coaching: target cse 2025.

Are you struggling to finish the UPSC CSE syllabus without proper guidance?

- IAS Preparation

- UPSC Preparation Strategy

- Environmental Movements In India

Environmental Movements in India

An environmental movement is a type of social movement that involves an array of individuals, groups and coalitions that perceive a common interest in environmental protection and act to bring about changes in environmental policies and practices.

Environmental and ecological movements are among the important examples of the collective actions of several social groups.

This article will provide information about Environmental Movements in India in the context of the IAS Exam .

This is useful for the Environment section of the UPSC Syllabus .

The candidates can read more relevant articles from the links provided below:

Cause of Environmental Movements

- The increasing confrontation with nature in the form of industrial growth, degradation of natural resources, and occurrence of natural calamities, has resulted in imbalances in the bio-spheric system.

- Control over natural resources

- False developmental policies of the government

- Right of access to forest resources

- Non-commercial use of natural resources

- Social justice/human rights

- Socioeconomic reasons

- Environmental degradation/destruction and

- Spread of environmental awareness and media

Major Environmental Movements in India

Many environmental movements have emerged in India, especially after the 1970s. These movements have grown out of a series of independent responses to local issues in different places at different times.

Some of the best known environmental movements in India have been briefly described below:

The Silent Valley Movement

- The silent valley is located in the Palghat district of Kerala.

- It is surrounded by different hills of the State.

- The idea of a dam on the river Kunthipuzha in this hill system was conceived by the British in 1929.

- The technical feasibility survey was carried out in 1958 and the project was sanctioned by the Planning Commission of the Government of India in 1973.

- In 1978, the movement against the project from all corners was raised from all sections of the population.

- The movement was first initiated by the local people and was subsequently taken over by the Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP).

- Many environmental groups like the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) and Silent Valley Action Forum participated in the campaign.

To read more about the Silent valley movement , check the linked article.

Chipko Movement

- Chipko Movement started on April 24, 1973, at Mandal of Chamoli district of Gharwal division of Uttarakhand.

- The Chipko is one of the world-known environmental movements in India.

- The movement was raised out of ecological destabilisation in the hills.

- The fall in the productivity of the forest produces forced the hill dwellers to depend on the market, which became a central concern for the inhabitants.

- Forest resource exploitation was considered the reason behind natural calamities like floods, and landslides.

- On March 27 the decision was taken to ‘Chipko” that is ‘to hug’ the trees that were threatened by the axe and thus the chipko Andolan (movement) was born.

- This form of protest was instrumental in driving away the private companies from felling the ash trees.

To read more about the Chipko movement in detail, check the linked article.

Bishnoi Movement

- This movement was led by Amrita Devi, in which around 363 people sacrificed their lives for the protection of their forests.

- This movement was the first of its kind to have developed the strategy of hugging or embracing the trees for their protection spontaneously.

To read more about Bishnoi Movement in detail, check the linked article.

Appiko Movement

- It is a movement inspired by the Chipko movement by the villagers of Western Ghats,

- In the Uttar Kannada region of Karnataka, the villagers of Western Ghats started the Appiko Chalewali movement during the month of September – November 1983.

- Here, the destruction of forest was caused due to commercial felling of trees for timber extraction.

- Natural forests of the region were felled by the contractors, which resulted in soil erosion and drying up of perennial water resources.

- In the Saklani village in Sirsi, the forest dwellers were prevented from collecting usufructs like twigs and dried branches and non-timber forest products for the purposes of fuelwood, fodder, honey etc. They were denied their customary rights to these products.

- In September 1983, women and youth of the region decided to launch a movement similar to Chipko, in South India.

- The agitation continued for 38 days, and this forced the state government to finally concede to their demands and withdraw the order for the felling of trees.

To read more about Appiko Movement in detail, check the linked article.

Narmada Bachao Andolan

- Narmada is one of the major rivers of the Indian Peninsula.

- The scope of the Sardar Sarovar project, a terminal reservoir on Narmada in Gujurat in fact is the main issue in the Narmada Water dispute.

To read more about Narmada Bachao Andolan in detail, check the linked article.

Jungle Bachao Andolan

- Jungle Bachao Andolan began in the 1980s in the Singhbhum district of Bihar (presently in Jharkhand).

- It was a movement against the government’s decision to grow commercial teak by replacing the natural Sal forests.

- The tribal community is the most affected by this decision as it disturbs the rights and livelihood of Adivasis of that region.

- This movement was widely spread in states like Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha in various other forms.

To read more about Jungle Bachao Andolan in detail, check the linked article.

Environmental Movements in India [UPSC Notes]:- Download PDF Here

Other related links:

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation, register with byju's & download free pdfs, register with byju's & watch live videos.

History of the Environmental Movement

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 31 May 2022

- Cite this living reference work entry

- László Erdös 2

53 Accesses

For a long time during our evolution, the effect humans had on their environment was not qualitatively different from the effect of several other mammal species. The agricultural revolution changed the nature-human relationship fundamentally. From this time on, the non-human world was regarded as mere raw material: nature (and indigenous peoples living in harmony with nature) had to be destroyed, subdued, dominated, or exploited. This world view was dominant until the era of Romanticism, when poets, writers, painters, and philosophers recognized the beauty of nature. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were among these pioneers. National parks have been set up everywhere on the globe, non-governmental conservation organizations have been launched, and international agreements have come into force. Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring and the 1970 Earth Day boosted the green movement. The 1986 ban on commercial whaling, the 1987 Montreal Protocol to phase out the chemicals destroying ozone, and the 1991 treaty to protect Antarctica are among the few global successes of the green movement, while efforts to combat climate change have not yet been crowned with success. Today, the importance of green issues is increasingly recognized. John Muir said, “The battle for conservation […] is part of the universal warfare between right and wrong.” Whether we can win this war may well depend on our ability to change our relationship with nature and to abandon the tragically obsolete myth of human superiority.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Nature Conservation and Its Bedfellows: The Politics of Preserving Nature

A Commons for Whom? Racism and the Environmental Movement

Adams WM (2004) Against extinction: the story of conservation. Earthscan, Abingdon

Google Scholar

Archibald S, Staver AC, Levin SA (2012) Evolution of human-driven fire regimes in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:847–852. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118648109

Article Google Scholar

Bekoff M (2013) Who lives, who dies, and why? How speciesism undermines compassionate conservation and social justice. In: Corbey R, Lanjouw A (eds) The politics of species. Reshaping our relationships with other animals. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 15–26

Chapter Google Scholar

Boulding KE (1966) The economics of the coming spaceship earth. In: Jarrett H (ed) Environmental quality issues in a growing economy. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 3–14

Callicott JB (1990) Whither conservation ethics? Conserv Biol 4:15–20

Carson R (1962) Silent spring. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Centeri C, Penksza K, Gyulai F (2008) A világ természetvédelmének története a II. világháború alatt. Tájökológiai Lapok 6:209–220

Coletta WJ (2001a) William Wordsworth. In: Palmer JA (ed) Fifty key thinkers on the environment. Routledge, London, pp 74–83

Coletta WJ (2001b) John Clare. In: Palmer JA (ed) Fifty key thinkers on the environment. Routledge, London, pp 83–93

Cronon W (1996) The trouble with wilderness: or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environ Hist 1:7–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/3985059

Daly HE (1972) In defense of a steady-state economy. Am J Agric Econ 54:945–954. https://doi.org/10.2307/1239248

Diamond JM (1992) The third chimpanzee: The evolution and future of the human animal. HarperCollins, New York

Diamond JM (2002) Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature 418:700–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01019

Emerson RW (1836) Nature. James Munroe and Company, Boston

Erdős L (2019) Green heroes from Buddha to Saint Francis of Assisi. Springer, Cham

Erdős L, Tölgyesi C, Bátori Z, Magnes M, Tolnay D, Bruers S (2017) Three sides of the same coin? The main directions of the environmental movement. Appl Ecol Environ Res 15:177–194. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1504_177194

Gadgil M, Guha R (1993) This fissured land: an ecological history of India. University of California Press, Berkeley

Glied V (2016) A halványtól a mélyzöldig: a globális környezetvédelmi mozgalom negyed százada. Publikon Kiadó, Pécs

Grove RH (1992) Origins of western environmentalism. Sci Am 267:42–47

Grove RH (1997) Green imperialism: colonial expansion, tropical island edens and the origins of environmentalism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Haila Y (2012) Genealogy of nature conservation: a political perspective. Nat Conserv 1:27–52

Hunter ML, Gibbs J (2007) Fundamentals of conservation biology, 3rd edn. Blackwell, Malden

Kerényi A (2003) Európa természet- és környezetvédelme. Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, Budapest

Kline B (2011) First along the river: a brief history of the U.S. environmental movement, 4th edn. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham

Krasińska M, Krasiński ZA (2013) The European bison and the aurochs on polish territory. In: Krasińska M, Krasiński ZA (eds) European bison. Springer, Berlin, pp 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-36555-3_6

Leopold A (1949) A Sand County almanac and sketches here and there. Oxford University Press, New York

Marsh GP (1864) Man and nature; or, physical geography as modified by human action. Charles Scribdner, New York

Book Google Scholar

McNeill JR (2000) Something new under the sun: an environmental history of the twentieth century. W.W. Norton and Company, New York

Meadows DH, Meadows DL, Randers J, Behrens WW III (1972) The limits to growth. Potomac Associates, New York

Meffe GK, Carroll CR, Groom MJ (2006) What is conservation biology? In: Groom MJ, Meffe GK, Carroll CR (eds) Principles of conservation biology, 3rd edn. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, pp 3–25

Muir J (1916) A thousand-mile walk to the Gulf. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston

Noss R (1999) Is there a special conservation biology? Ecography 22:113–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.1999.tb00459.x

Schumacher EF (1973) Small is beautiful: a study of economics as if people mattered. Blond & Briggs, London

Scott P, Burton JA, Fitter R (1987) Red data books: the historical background. In: Fitter R, Fitter M (eds) The road to extinction. IUCN, Gland, pp 1–5

Silveira S (2004) The American environmental movement: surviving through diversity. Boston Coll Environ Aff Law Rev 28:497–532

Standovár T, Primack RB (2001) A természetvédelmi biológia alapjai. Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, Budapest

Strong DH (1988) Dreamers and defenders: American conservationists. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln

Takács-Sánta A (2004) The major transitions in the history of human transformation of the biosphere. Hum Ecol Rev 11:51–66

Thoreau HD (1854) Walden; or, life in the woods. Ticknor and Field, Boston

Van Dyke F (2008) Conservation biology: foundations, concepts, applications, 2nd edn. Springer, Dordrecht

Weart SR (2004) The discovery of global warming. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Wellock TR (2007) Preserving the nation: the conservation and environmental movements 1870–2000. Harlan Davidson, Wheeling

Wildes FT (1995) Recent themes in conservation philosophy and policy in the United States. Environ Conserv 22:143–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900010195

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

MTA-DE Lendület Functional and Restoration Ecology Research Group, Debrecen, Hungary

László Erdös

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Erdös, L. (2022). History of the Environmental Movement. In: The Palgrave Handbook of Global Sustainability. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38948-2_144-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38948-2_144-1

Received : 10 November 2021

Accepted : 06 January 2022

Published : 31 May 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-38948-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-38948-2

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Earth and Environm. Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Essay on Green Movement

Students are often asked to write an essay on Green Movement in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Green Movement

Introduction to green movement.

The Green Movement is a broad global campaign aimed at promoting environmental sustainability. It encourages people to adopt eco-friendly practices like recycling and conservation.

Origins of the Green Movement

The Green Movement began in the 1960s in response to growing concerns about pollution and environmental damage. It has since grown into a worldwide effort.

Impact of the Green Movement

The Green Movement has led to significant changes in laws and practices. It has raised awareness about the importance of protecting our planet for future generations.

In conclusion, the Green Movement plays a crucial role in ensuring a healthy and sustainable environment. It is up to us to continue this important work.

Also check:

- Speech on Green Movement

250 Words Essay on Green Movement

Introduction to the green movement.

The Green Movement, also known as the environmental movement, is a broad-based, global initiative focused on advocating for policies that protect the environment and promote sustainability. It emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, in response to growing public concern about ecological degradation and pollution.

Driving Forces of the Green Movement

The Green Movement is driven by a variety of factors, including the recognition of the finite nature of natural resources, the impact of industrialization and urbanization on the environment, and the need for sustainable development. It is propelled by individuals, non-governmental organizations, and governments alike, all recognizing the urgent need for change.

Impacts and Achievements

The Green Movement has had significant impacts on public policy, corporate behavior, and public awareness. It has led to the establishment of environmental laws, the promotion of renewable energy, and the development of sustainable practices. It has also played a crucial role in raising awareness about climate change and other environmental issues.

Challenges and the Future

Despite its achievements, the Green Movement faces challenges. These include resistance from industries dependent on fossil fuels, economic factors, and political obstacles. However, with the increasing urgency of environmental issues, the movement’s relevance and influence are likely to grow. The future of the Green Movement lies in its capacity to adapt, innovate, and mobilize towards a sustainable future.

500 Words Essay on Green Movement

The Green Movement, also known as the environmental movement, is a socio-political and cultural phenomenon that began in the mid-20th century. It encompasses various environmental issues including conservation, preservation, and the sustainable management of resources. The movement has been instrumental in raising awareness about environmental degradation and the urgent need for sustainable practices.

Origins and Evolution

The Green Movement originated in the 1960s, a time marked by rapid industrialization and urbanization. The publication of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” in 1962, which highlighted the detrimental effects of pesticides on the environment, is often credited as the catalyst. The subsequent decades saw the movement evolve from local and national campaigns into a global agenda. Milestones such as the United Nations’ Stockholm Conference in 1972 and the Earth Summit in 1992 underscored the international recognition of environmental concerns.

Key Principles and Goals

The Green Movement is guided by principles like sustainability, biodiversity, ecological integrity, social justice, and non-violence. Its primary goal is to ensure the earth’s resources are used responsibly, conserving them for future generations. The movement also advocates for policies to reduce pollution, halt deforestation, and mitigate climate change.

Impact and Achievements

The Green Movement has significantly influenced public policy, corporate behavior, and individual lifestyles. It has led to the establishment of environmental laws and regulations, the creation of national parks and protected areas, and the rise of renewable energy. The movement has also fostered the growth of ‘green’ industries, such as organic farming and green building, and has encouraged consumers to make more environmentally friendly choices.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its successes, the Green Movement faces several challenges. These include political resistance, corporate pushback, economic constraints, and public apathy. Additionally, the movement must contend with the complex, interconnected nature of environmental problems, which often require multidisciplinary solutions and international cooperation.

Looking ahead, the Green Movement must continue to innovate and adapt. It will need to engage more effectively with diverse stakeholders, harness new technologies, and develop strategies that integrate environmental, social, and economic considerations.

In conclusion, the Green Movement has played a crucial role in highlighting the importance of environmental stewardship. While significant strides have been made, much work remains to be done. As we face the escalating threats of climate change and biodiversity loss, the principles and goals of the Green Movement are more relevant than ever. Ultimately, the success of the movement will depend on our collective willingness to embrace sustainable practices and make the necessary changes to protect our planet.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Green Day

- Essay on Grapes

- Essay on Your Grandmother

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

48 The Impacts of Environmental Movements

Christopher Rootes is Professor of Environmental Politics and Political Sociology; and Director of the Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements at University of Kent

Eugene Nulman is a PhD Candidate and Assistant Lecturer in the School of Socil Policy, Sociology, and Social Research at University of Kent

- Published: 09 July 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The impacts of environmental movements (EMs) are indirect and mediated outcomes of efforts by actors ranging from environmental NGOs to grass-roots activists to influence environmental policies and practices of governments and corporations, usually by mobilizing public opinion. With fewer resources than industry groups, EMs’ impacts are dependent on mass media coverage, the fluctuating salience of environmental issues, and political opportunities. EMs influence policy by deploying scientific knowledge, more successfully where they have special expertise. In international negotiations, EMs have acted as brokers between North and South to influence global environmental policies. In authoritarian states, EMs have enlarged scope for civil society and democratic participation.

In the academic and—especially—in the activist literature, claims or assumptions about the impacts of environmental movements upon policy, practice, and outcomes are legion. Indeed, grand, often inflated claims have been made for the influence of environmental movements by their activists and opponents alike. Yet, because the impacts of social movements are notoriously difficult to assess, the impacts of environmental movements have been relatively under-investigated, and because such competing claims are so difficult to assess, the impact of environmental movements remains highly contested.

From the 1970s onwards, the history of environmental movements in North America, western Europe, and Australia has generally been told as one of a series of inspiring victories as one relatively unspoiled fragment of the natural environment after another has been spared from developers, and as some of the most egregious instances of pollution of air, land, and water have been mitigated. Yet, even since the 1960s, the great strides that have been made toward effective environmental protection have not been solely the products of environmental movements. The US Clean Air Acts, for example, resulted from initiatives of Congress even before anything recognizable as an environmental movement emerged. In many cases, despite the undoubted value of the efforts of environmental movements, there is a pervasive chicken and egg problem: did the movement discover the problem or did it, rather, amplify existing public or elite opinion and, by mobilizing some of the public, channel it into the policy arena?

Environmental Movements

Since the 1960s, we have become accustomed to speaking of “the environmental movement.” Although many of its constituents do not take action as demonstrative or conflictual, even confrontational, as that we commonly associate with other social movements, some do. Indeed, “environmental movement” is a problematic denotation of a phenomenon that is highly diverse in its forms of organization and action, from the radical, but sometimes covert, direct action of the “green” movement ( Doherty 2002 ), through demonstrative public protest, to the often publicly invisible actions of bureaucratized formal organizations that lobby governments or work in concert with governments and/or corporations to achieve desired environmental outcomes.

The latter end of the continuum presents particular difficulties, and some have suggested that it is better referred to as a “public interest lobby” or an “advocacy coalition” rather than a movement ( Bosso 2005 ). Some environmental NGOs, however, rarely lobby, let alone protest, but are preoccupied with practical action to remedy environmental degradation or to protect remnants of relatively pristine natural environments.

To define “environmental movements” restrictively would be at odds with the discourse of environmentalists themselves, which is generally inclusive and recognizes commonalities among environmental groups and organizations that are rooted in the shared concern to protect the natural environment that exists among the members and supporters of environmental organizations of various kinds. Thus, we define an environmental movement as a loose, non-institutionalized network of informal interactions that includes, as well as individuals and groups who have no organizational affiliation, organizations of varying degrees of formality, and is engaged in collective action motivated by shared identity or concern about environmental issues ( Rootes 2004 ).

Much grass-roots environmental activism is only loosely linked to mainstream environmental movement organizations (EMOs) or, indeed, to other instances of grass-roots action. Yet though the links and networks may be precarious, such local action is informed by the climate of opinion to which EMOs have contributed, and has often played a discovery role for national EMOs ( Carmin 1999 ) and served to train activists who have gone on to rejuvenate wider environmental movements.

The Bases of Impact

The impact of environmental movements, and the pressure they exert on governments, corporations, and other actors, is not simply proportional to the frequency or intensity of their mobilization of public protests or, indeed, of the numbers of participants therein. Indeed, recourse to street demonstrations may mark not the strength but the weakness of a movement, and its embrace of confrontational tactics may reflect the desperation of the politically excluded. For the most part, in highly economically developed Northern states, especially in Europe, the environment has generally been a valence issue that attracts a relatively high measure of endorsement across the political spectrum and does not sharply divide mainstream political parties. Under such conditions, environmentalists may enjoy relatively easy access to policy makers and decision makers.

Environmental NGOs, especially in the North, generally ground their influence and legitimacy upon their insistence that their claims are based on the best available scientific evidence. Sometimes they commission original research; more generally, they deploy published research. As a result of long engagement with particular issues, such NGOs earn respect for their expertise and are, as a result, sometimes drawn into advising or acting as contractors to governments and corporations that lack either scientific expertise or the capacity effectively to communicate to the public the environmental issues that they confront.

Nevertheless, if their reliance upon scientific evidence gives such environmental NGOs credibility with the powerful, it inhibits NGOs’ ability to campaign on issues where scientific evidence is weak. This is especially problematic where public concern about an issue, such as incinerator emissions, cannot be warranted by scientific evidence of harm. Even in the absence of such evidence, and without overt support from established NGOs, local environmental campaigns may nevertheless be successful in mobilizing against proposed developments, not only in Northern countries with nominally democratically accountable governments and officials, but even in authoritarian states such as China ( Lang and Xu 2013 ) where governments’ desire to avoid sustained civil unrest may outweigh concern to implement development policies. Although it is by no means inevitable, the frequency of local environmental campaigns may lead governments and corporations to avoid particular strategies and technologies altogether, and so local campaigners may achieve impacts where environmental NGOs cannot.

The impacts of environmental movements may be direct or indirect, negative or positive. Thus environmental movements may embrace action designed to head-off, derail or obstruct the formation or development of draft or mooted policies, or they may promote the formation or development of policies designed to achieve desired environmental ends. Equally, once policy is formulated and promulgated, environmental movements may oppose or obstruct its implementation, or contrive to make the implementation of environmentally desirable policy more effective.

Impacts on Policy Formation

Examples of the negative impacts of environmental movements on policy formation or development are legion. In the United States, anti-nuclear and anti-incineration campaigners have been credited with preventing the commissioning of any new nuclear power stations or waste incinerators for three decades from 1980. In the UK, the Blair/Brown Labour government (1997–2010) essayed a series of policies concerning genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and new housing on greenfield sites, and repeatedly backed down when faced by environmental movement protests. Similarly, that government’s coalition successor watered down proposed changes to land-use planning in the face of concerted opposition.

Of the many cases in which EMOs have positively influenced the shaping of environmental policy, perhaps none is more iconic than the role EMOs played in securing passage of the UK Climate Change Act 2008, then the most ambitious and potentially consequential environmental legislation in the world. Beginning in 2005, Friends of the Earth (FoE) and other EMOs began to mobilize public support for decisive action to combat climate change. FoE proposed a draft Climate Change Bill requiring annual 3 per cent reductions in greenhouse gas emissions leading to an 80 per cent reduction by 2050, and worked with representatives of each major political party to steer the issue into parliamentary debate. FoE encouraged its supporters to lobby their Members of Parliament to sign declarations of support for the Bill, which 412 of the 646 MPs eventually did. This led the government to adopt the Bill, whilst watering down its more ambitious provisions. However, as the Bill proceeded through the parliamentary process, FoE urged its members to continue to lobby MPs to strengthen the Bill. Public and private lobbying persuaded many MPs to press the government to accept the 80 per cent reduction target and to include annual indicative targets while maintaining five-year binding targets ( Nulman 2015 ).

Not the least interesting aspect of this case is the extent to which an EMO successfully engaged with the formal political and legislative process to secure passage of legislation that realized most of its objectives; even when it sought to mobilize its supporters it did so by conventional means: a petition, albeit online, and a campaign of writing letters and sending emails and postcards to MPs. In securing passage of unprecedentedly ambitious legislation, FoE undoubtedly made an impact, but it did so by means not generally central to the repertoires of social movements. Yet FoE’s methods were appropriate to the circumstances. Whilst it is unlikely that any such ambitious legislation would have made its way to the statute books without FoE’s initiative and persistence, it was widely perceived to be timely, as the ease with which so many MPs were persuaded to support it attests.

The experience of the US environmental movement with respect to climate change is in stark contrast. With federal government action on climate change blocked by hostile Republican majorities in Congress, the US climate movement has more often taken the form of protest, and its impacts have been greatest in states and cities where legislators have been sympathetic.

Although the influence of environmental movements is mediated by the variety of other actors and interests, and identifying specifically movement impacts is accordingly difficult, it appears that the influence of environmental movements upon policy is greatest in the early, agenda-setting stages of policy formation, when policy preferences are malleable rather than entrenched ( Olzak and Soule 2009 ). Thus, at this liminal stage, movement organizations may strategically frame policy issues so as to shape the preferences of elite actors. Some, however, may seek to raise awareness even of issues on which attitudes are culturally embedded or politically entrenched in order to problematize them and to mobilize public opinion to demand policy change.

Impacts on Policy Implementation

The impacts of environmental movements upon policy implementation may be positive as well as negative. Thus environmental campaigns and mobilizations may ensure local implementation of national policies and international treaties. In many countries, wildlife conservation organizations campaign principally to ensure the implementation of protective legislation.

Often, however, environmental campaigners have resisted, and sometimes successfully obstructed the implementation of government policy. In some cases the impact of the environmental movement appears clear, as, for example, in the case of the protests in Germany that disrupted the transport of nuclear waste. In both Germany and the United States, protests have prevented the construction of permanent nuclear waste repositories. Yet although it was sustained pressure from environmentalists that maintained the high profile of the nuclear issue in Germany from the 1970s onward, it was an external event—the nuclear disaster at Fukushima, Japan—that triggered the decision to close Germany’s nuclear reactors.

The 1990s campaign against the UK road-building program stimulated a series of protracted and innovative protests that delayed and escalated the costs of road-building, but it is less clear that it was their impact, rather than a recession-induced state fiscal crisis, that brought the program to a premature end.

In general, the impact of environmental movements upon policy implementation is often indirect and difficult to distinguish from the impacts of other actors, processes, and events.

Impacts on Public Opinion

Social movements are usually conceived of as phenomena of civil society. However large the initial mobilization, most movements, in the attempt to build a constituency for social and/or political change, appeal to wider sections of the public, either directly to change social practice or in order to enlist public opinion in the struggle to persuade governments or corporations to change policy and/or practice. Indeed, Burstein (1999) concludes that movements influence policy outcomes only when their actions are mediated by public opinion.

Many of the achievements of environmental movements have resulted from lobbying and persuasion that is not usually publicly visible. Precisely because it is not visible, the extent of its impact is disputable and cannot easily be assessed ( Giugni 2004 ). But even where the actions of environmental movements are highly visible, determining the extent and significance of their impact is more art than science. Studies that purport to demonstrate the impact of movements on public opinion are generally correlational, observing the correlation between a movement’s articulation of a discourse and the appearance of its traces in public opinion, ideally after a plausible elapse of time. In a notably sophisticated study of the impact of protest upon public policy, Agnone (2007) found that, controlling for media attention, legislative context, and election cycles, more federal environmental protection legislation was passed in the United States when environmental movement protest amplified, or raised the salience of, pro-environmental public opinion. Such impacts may be amplified by the relatively high levels of public approval of the environmental movement and trust in environmental NGOs ( Dunlap and Scarce 1991 ; Inglehart 1995 ).

In general, in democratic states, the impact of environmental movements upon public policy is greatest where it runs with the grain of public opinion, and especially where the movement’s diagnostic and prognostic frames resonate with (significant parts of) the public. In an apparently infinite iterative process, environmental activists seek to shape public opinion and thereby influence the formation of environmental policy. In this the mass media have been an indispensable tool, for it is through the mass media that most people gain information about the environment as about other issues. Of environmental NGOs, Greenpeace has been the most consistently adroit and assiduous in its exploitation of the opportunities provided by mass media to reach the public and thence to bring pressure to bear upon governments and corporations. Whether campaigning against nuclear weapons testing, whaling or sealing, or latterly against transnational oil companies, Greenpeace has highlighted environmental degradation and parlayed public opinion into persuading governments and corporations to change policy and practice ( Zelko 2013 ).

By engaging the public, environmental movements have often been credited with setting the agenda for public policy on environmental matters, but in general their impact is perhaps better conceived not as agenda-setting so much as highlighting neglected issues, maintaining their salience, keeping public concern alive even at times when the attentions of policy makers are diverted elsewhere by other pressing issues such as those of economic crisis management, and pressing their advantage when windows of political opportunity are opened.