Media Studies @ Guilsborough Academy

Centre Number: 27214

Stuart Hall – Representation Theory

Stuart Hall – representation theory

What is the theory?

Stuart Hall’s REPRESENTATION theory (please do not confuse with RECEPTION ) is that there is not a true representation of people or events in a text, but there are lots of ways these can be represented. So, producers try to ‘fix’ a meaning (or way of understanding) people or events in their texts.

What is the more advanced version?

Representation is not about whether the media reflects or distorts reality, as this implies that there can be one ‘true’ meaning, but the many meanings a representation can generate. Meaning is constituted by representation, by what is present, what is absent, and what is different. Thus, meaning can be contested.

A representation implicates the audience in creating its meaning. Power – through ideology or by stereotyping – tries to fix the meaning of a representation in a ‘preferred meaning’. To create deliberate anti-stereotypes is still to attempt to fix the meaning (albeit in a different way). A more effective strategy is to go inside the stereotype and open it up from within, to deconstruct the work of representation.

Where can I use it?

Any time a producer of a text tries to ‘fix’ a meaning of a person or event – this will usually reveal viewpoints and bias (political or otherwise) – usually newspapers attempt to demonise groups of people. However, anti-stereotypical representations also try to fix meanings too – so these groups of people who were demonised in some papers might be presented as heroic in others.

Look at the representations of a previous British Prime Minister below:

How have the papers attempted to fix different meanings and how does this reveal their bias (political, gender)?

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Blog at WordPress.com.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Media Studies

- Communication

- Linguistics

Stuart Hall | Pioneering Diversity & Inclusivity in Media

- July 9, 2023 March 31, 2024

Have you ever wondered how media influences our thoughts and society? Well, lets introduce you to a brilliant scholar named Stuart Hall. He dedicated his life to studying media and culture. Thus, Hall’s ideas have greatly shaped the field of media and communications. Let’s further explore some of his key theories and concepts.

Stuart Hall (1932-2014) was a renowned British cultural theorist and sociologist. Hall made significant contributions to the field of media and cultural studies. Born in Jamaica, Hall then moved to the United Kingdom in the 1950s. It was here where he played a pivotal role in shaping the intellectual landscape. He co-founded the influential Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) at the University of Birmingham. This then ended up becoming a hub for critical analysis of media, culture, and society.

Hall’s work focused on examining the interplay between media, power, identity, and representation. As a result, he emphasises the role of media in shaping our perceptions of the world. Hall further highlights the ways in which cultural identities are constructed and negotiated. Hall’s theories, such as encoding and decoding, have been instrumental in understanding how media messages are produced and interpreted.

Also throughout his career, Hall advocates for Multiculturalism and social justice, emphasising the importance of inclusivity and diversity in media representation. Furthermore, his insightful ideas and scholarship continue to inspire scholars, activists, and students worldwide. Thus, Hall leaves a lasting impact on the field of media and communications.

Stuart Hall on Media Representations

According to Hall, media plays a crucial role in shaping our understanding of the world. He believes that media representations are not neutral, but rather they are constructed based on social and cultural factors. For instance, television shows, movies, and advertisements often present certain groups of people in stereotypical ways. Thus, these representations can influence our perceptions and reinforce existing power structures.

Stuart Hall on Multiculturalism

Stuart Hall was also an advocate for multiculturalism, which recognises and celebrates the diversity of cultures within a society. He believes that media should reflect the multicultural nature of society and give voice to marginalised communities. Hall further argues that media representation should not perpetuate stereotypes or exclude certain cultural groups. Instead, it should promote inclusivity and provide a platform for different voices and perspectives.

Stuart Hall’s Encoding & Decoding

Hall introduced the concept of Encoding/Decoding in media messages, expanding the well known Reception Theory . He argued that when media producers create content, they encode their intended meaning into it. However, audiences don’t always interpret the messages in the same way. They also bring their own cultural and social backgrounds, which influence how they decode the messages. This means that the audience actively interprets media texts instead of passively accepting them.

Stuart Hall on Cultural Identity & Hybridity

Hall was interested in the concept of cultural identity, particularly in the context of diaspora and migration. He emphasised that cultural identity is not fixed but constantly negotiated and constructed. Hall also believes that individuals have multiple identities that are shaped by their cultural backgrounds, experiences, and interactions with others. He also explores the idea of Cultural Hybridity , where different cultures blend together, creating new and unique forms of identity.

Hegemony & Resistance

Another significant contribution by Hall is the theory of hegemony. He argues that those in power use the media to maintain their dominance over society. Therefore, media messages often promote the interests and values of the ruling class, creating a dominant ideology. However, Hall also believes in the potential for resistance. He further emphasises that audiences can actively challenge and reinterpret media messages, creating alternative meanings and resisting dominant ideologies.

Stuart Hall’s theories have revolutionised the field of media and communications. His ideas on media representations, encoding and decoding, cultural identity, and hegemony have provided valuable insights into how media shapes our understanding of the world. Therefore, understanding Hall’s work helps us become critical consumers of media and empowers us to challenge dominant narratives.

Hall , S. (1973). Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse . Discussion Paper. University of Birmingham, Birmingham.

Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/Decoding . In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-79 (pp. 128-138). Routledge.

Hall, S. (1982). The Rediscovery of “Ideology”: Return of the Repressed in Media Studies . In M. Gurevitch, T. Bennett, J. Curran, & J. Woollacott (Eds.), Culture, Society, and the Media (pp. 56-90). Routledge.

Hall, S. (1992). The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power . In S. Hall & B. Gieben (Eds.), Formations of Modernity (pp. 275-332). Polity Press.

Hall, S. (1990). Cultural Identity and Diaspora . In J. Rutherford (Ed.), Identity: Community, Culture, Difference (pp. 222-237). London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices . SAGE Publications.

Representation Theorists

Baudrillard – Hyper Reality: “Some texts are difficult to distinguish in terms of the representation of reality from a simulation of reality e.g. Big Brother. The boundaries are blurred as codes and conventions create a set of signifiers which we understand but in fact the representation is a copy of a copy”.

Judith Butler – Queer Theory: “Gender is what you do, not who you are with the theory contesting the categorization of gender and sexuality – identities are not fixed and they cannot be labelled e.g. potentially androgynous representations like Gok Wan.

Carol Clover – Last Girl Theory (Horror): “In many horror films, like Halloween typically the last girl that survives is pure, chaste and virginal while all of her friends with looser morals have been killed. Even the name of the last girl is often unisex e.g. Sidney, Teddy or Billie and has elements of androgyny and sometimes also a shared history with the killer”.

Richard Dyer – Stereotypes Legitimize Inequality: “A way to ensure unequal power relations are maintained is to continually stereotype – GTAV is a misogynist video game where players have the opportunity to kill prostitutes in their own violent way – the game is entirely male point of view and arguably serves to maintain dominant male culture”.

Stuart Hall – Dominant, Oppositional and Negotiated Readings of Representation: “Stuart Hall’s theory (see audiences) is also useful in understanding how some representations reflect the dominant culture e.g. patriarchy, women in The Sun and in Men’s Magazines like FHM. However, some representations can be negotiated or even misunderstood (oppositional) as in Four Lions which was accused of being a racist text due to its representation of British Pakistani Muslims”.

Angela McRobbie – Post Feminist Icon Theory: “Lara Croft, Lady Gaga and Madonna for example could be identified as post feminist icons as they exhibit the stereotypical characteristics of both the male and female – strength, courage, control and logic but also are willing to be sexualized for the male gaze. This control element of their own representation is crucial in understanding the theory”.

Andy Medhurst – Stereotyping is Shorthand for Identification: “One way that texts like Waterloo Road and Skins for example allow for audience identification is through stereotyping and giving characters an extreme representation”.

Laura Mulvey – Male Gaze/Female Gaze: “Women on the front cover of FHM are sexualized and objectified for the male audience while the same can be said for male models in perfume adverts, sexualized for a female demographic”.

Tessa Perkins – Stereotyping has Elements of Truth: “Although stereotyping can have negative effects often it is based of some degree of reality but distorted and manipulated for the purpose of entertainment values”.

Levi-Strauss – Binary Oppositions and Subordinate Groups: “Levi-Strauss’ theory (see narrative theorists), like Dyer is a way of understanding how representation are deliberately placed in binary opposition to ensure the dominant culture is maintained and the minority representations is seen as subordinate and marginalized. In Game of Thrones southern regional identity is often seen as the preferred culture through representation within the mise-en-scene – there is more money in the south, the southern King speaks with an elaborated language code, the buildings have cleaner lines, dress code is smarter and there is significant daytime shooting. In the North the scenes are often shot at night, characters are rougher, have long hair and beards and are often seen heavy drinking and shouting, talking in an aggressive way about battles and conflict”.

Media Studies

- Developing a Research Question

- Finding Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Writing Tips

- Citing Sources

- News & Newspapers

- Television & Ratings Data

- Accessing Our Collections

- Foundational Texts

- Reference Sources

- Primary Sources & Archival Collections

- Journals and Newspapers

- Image, Stock Photo, and Audiovisual Resources

- Open Access & Additional Resources

- Resources & Services for Scholars

- Instructional Support

- MSCH F306 Writing Media Criticism

- MSCH J450 History of Journalism

- Campus & Community Resources

- Monthly Community Celebrations

- Collection & Subject Spotlights

- Representation in Media

Introduction: What is Representation?

Asian american representation in the media, human/non-human relationships in media, queer representation in media.

- Other Features

- Indigenous Heritage & History Month

- Defining Representation

- Academic Books

- Scholarly Articles

Welcome! This is our series on representations in media, highlighting how creators have portrayed various communities in the past and present, and where we hope to move in the future. On this page you will find features highlighting the portrayal of Asian American communities, Queer communities, and Animal/non-human species in film and television. These features contain resources for further research along with information on some of the common stereotypes/tropes associated with portrayals of these groups. We will continue to add new features periodically. This box serves as an introduction to the concept of representation in media featuring academic texts and scholarly articles on the topic.

In the broadest stokes, representation refers to the portrayal of people, groups, and communities in the media (including television, film, and books). Recently, audiences have asked for increased representation of underrepresented groups in media including of women, people of color, the queer community, transgender/nonbinary people, disabled people, and others. Audiences have also called for a greater diversity of religions, body types, nationality, and more to be portrayed on screen.

In trying to increase representation, however characters and plot lines can often fall into stereotypical depictions or tired tropes , especially when stories and characters are written or portrayed by members who are not part of a given group. According to Maja Hardikar, "the line between stereotype and representation is thin...it may be tempting to view the difference between “stereotype” and “representation” as the simple difference between good and bad; “representation” is when we see ourselves reflected up onscreen and feel empowered, “stereotype” is when the representation fails to represent us" (6). The features on this page discuss the histories of various stereotypes, which often originated from the first appearances members of a said group on screen (take, for example, The Dragon Lady or The Gay Best Friend).

Though representation might seem trivial, studies have shown that in some instances, the dissemination of diverse media is actually a transformative action . For example, a 2015 study found that when straight people are more exposed to gay characters on TV they become more accepting of gay equality, with a 2020 survey by GLAAD and P&G finding that queer representation increased queer acceptance by up to 45% (Bond and Compton; GLAAD).

Representation is only the beginning of a more equitable world for people whose identities do not afford them safety in the societies in which they live. Systemic, liberatory change requires deeper, more sustained movement, political activism, and community building. It is important to remember, however, that diverse representation can have dramatic, empowering , and beneficial effects on people's lives, especially when those representations depict complex characters in robust, nuanced stories.

Sources: Bond, B. J., & Compton, B. L. (2015). Gay On-Screen: The Relationship Between Exposure to Gay Characters on Television and Heterosexual Audiences’ Endorsement of Gay Equality. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media , 59 (4), 717–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1093485; GLAAD. (2020, May 27). Procter & Gamble and GLAAD Study: Exposure to LGBTQ Representation in Media and Advertising Leads to Greater Acceptance of the LGBTQ Community . https://glaad.org/releases/procter-gamble-and-glaad-study-exposure-lgbtq-representation-media-and-advertising-leads/ ; Hardikar, M. (2023). A Real Gay Person: Representation and Stereotypes in Queer Romantic Comedies . Georgetown University.

- Cross-cultural representation of ‘otherness’ in media discourse Caldas-Coulthard, C. R. (2003). Cross-cultural representation of ‘otherness’ in media discourse. In Critical discourse analysis: Theory and interdisciplinarity (pp. 272-296). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Gender, race, and media representation Brooks, D. E., & Hébert, L. P. (2006). Gender, race, and media representation. Handbook of gender and communication , 16, 297-317.

- Media and the representation of Others Fürsich, E. (2010). Media and the representation of Others. International social science journal , 61(199), 113-130.

- Diaspora in the digital era: Minorities and media representation Georgiou, M. (2013). Diaspora in the digital era: Minorities and media representation. Jemie , 12, 80.

- Media constructions of culture, race, and ethnicity Dixon, T. L., Weeks, K. R., & Smith, M. A. (2019). Media constructions of culture, race, and ethnicity. In Oxford research encyclopedia of communication .

- Media beyond representation Angus, I. H. (2022). Media beyond representation. In Cultural politics in contemporary America (pp. 333-346). Routledge.

- Introduction

- Academic Texts

The Model Minority Myth

- The "Dragon Lady"

- Techno-Orientalism

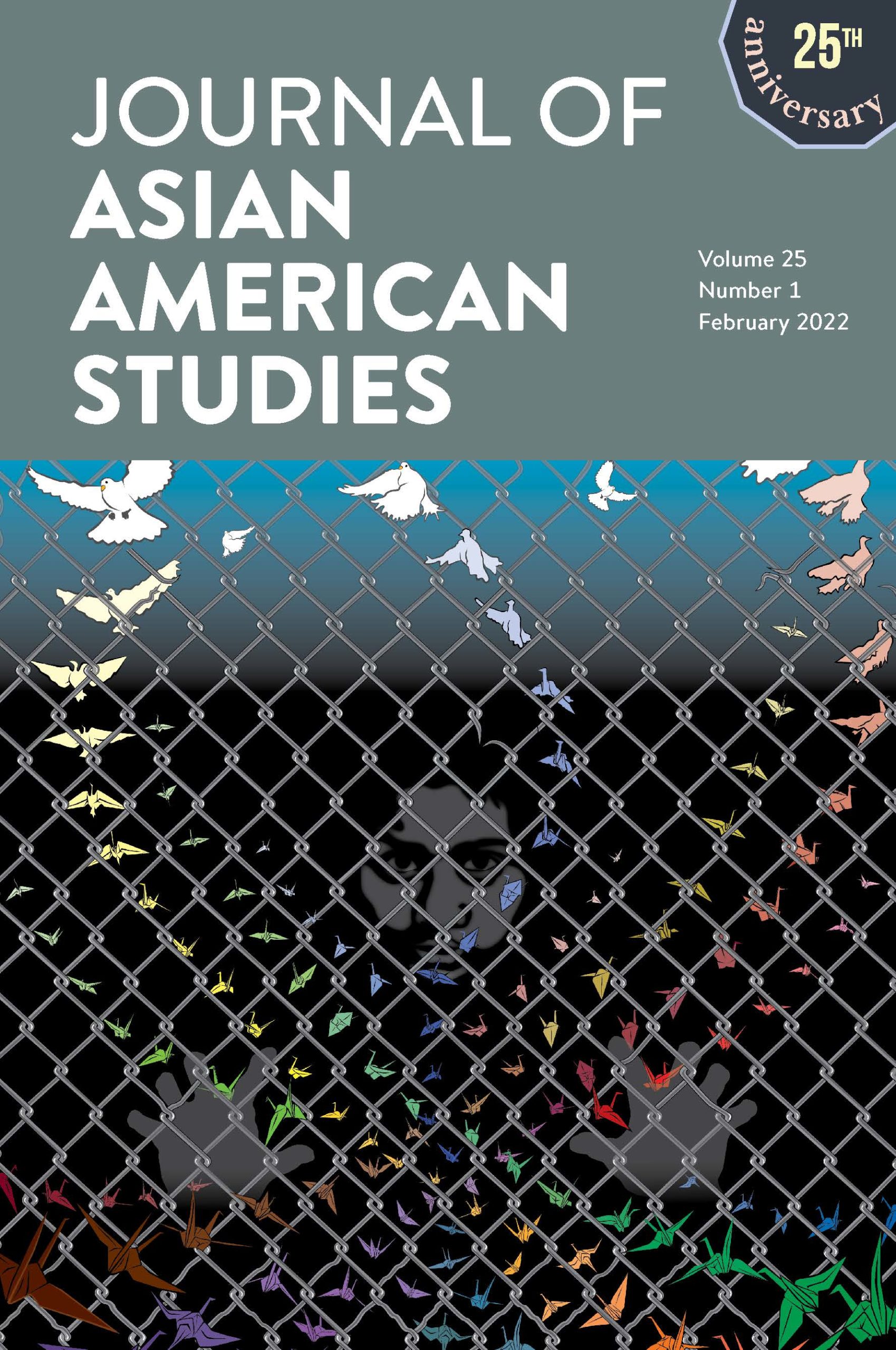

Images: Films (from left to right), Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), Bitter Melon (2018), PEN15 (2019-), Minari (2020).

Welcome to the Asian American Representation in the Media LibGuide. This guide will discuss the history of Asian American representation in the media—primarily in Hollywood—and examine some common tropes/stereotypes applied to Asian characters in film and television. Here, you will find brief discussions of the Model Minority Myth, the Dragon Lady trope, techno-orientalism, and whitewashing/yellowface, along with a selections of books and films written/created by Asian Americans featuring nuanced characters and portrayals of Asian experiences, including the movies and films in the above images.

In a recent study, “ I Am Not a Fetish or Model Minority ” (2021) from the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media and the Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment, researchers found that Asian and Pacific Islanders (API) actors made up only 4.5% of leads or co-leads in the top 10 grossing domestic films from 2010-2019. In films featuring API characters in the main cast, about a third of API characters "embody at least one common API trope or stereotype (35.2%)" such as the “Martial Artist,” the “Model Minority,” or the “Exotic Woman.” There is a long and continuing history of the whitewashing and stereotyping of Asian characters in Hollywood films. In 1935, MGM refused to consider Anna May Wong for the leading role O-Lan in the The Good Earth— instead casting Luise Rainer to play O-Lan in yellowface. In the 2023 biography Tetris , Taron Egerton, a Welsh actor was been cast to play video game publisher Henk Rogers, who is Dutch-Indonesian.

The guide serves only as an introduction and highlights texts in our collection that focus on Asian American representation in the media. For more information, see our companion guides including our Feminist Media Studies guid e which features brief explanations of stereotypes inflicted on women in the media:

- Asian American, Native Hawaiian, & Pacific Islander Heritage Month (Media Studies)

- Asian American Representation in the Media (Media Studies)

- Korea Remixed (Media Studies)

- Spotlight on Queer & Trans* Asian Literature and Poetics (Gender Studies)

- Asian American and Pacific Islander Philosophies (Philosophy)

- Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month Media Resources (Media Services)

- Asian American Artists, Architects, and Designers (Art, Art History, & Architecture)

- AAPI Identity - Recommended Reads from the Children's Collection (Education Library)

Video: The History of Asian Representation in Film . VICE News (2021).

Citations: Almost Half of All Asian Roles Serve as a Punchline, Study Finds . Sakshi Venkatraman, NBC News, 5 Aug. 2021.

Video: Why Do We Call Asian Americans The Model Minority? AJ+ (2017).

The Model Minority Myth is a stereotype of certain minority groups, particularly Asian Americans, as successful, well-adjusted, and therefore requiring little or no social and economic assistance. The phrase "model minority" originated in a 1966 New York Times article by William Peterson who used the phrase to describe the economic prosperity of Japanese Americans after WWII. Since then, the term has been applied to many other groups including Chinese Americans, Indian Americans, and Korean Americans. The model minority stereotype is not only harmful to Asian Americans because it groups them into a monolith but also in that it perpetuates the idea that other minority groups should be able to achieve model minority status not through the removal of systemic barriers but through hard work alone. This stereotype can be found in media, journalism, academia, popular culture, and more. For example, in 1987 TIME published their magazine with a cover photo of " Those Asian-American Whiz Kids ."

Images: (Left) Success Story, Japanese-American Style: Success Story, Japanese-American Style. William Peterson, New York Times, (1966) . (Right) Those Asian-American Whiz Kids. TIME Magazine (1987).

The Term "Asian American"

Scholars and activists have long critiqued the terms AAPI and Asian American as "masking differences in histories and needs among communities, as well as supporting the myth that Asian Americans are a monolithic group" ( Connie Hanzhang Jin, 2021 ). This monolithic mindset contributes society often overlooking diversity in the Asian American community in terms of ethnic groups, experience, immigration status, and economic circumstances . In fact, contrary to the Model Minority Myth which states that Asian Americans are an economically prosperous demographic that does not require financial assistance or investment, Asian Americans are actually the most economically divided racial group in America :

Graph: Key disparities in income and education among Asian American groups . Connie Hanzhang Jin, NPR (2021).

The perception of Asian Americans being economically and academically successful hides the fact that many Asian American communities experience high rates of poverty and Asian American students often feel intense academic pressure which leads to heightened rates of anxiety and stress. While the release of films and shows such as "Crazy Rich Asians" (the first film by a major Hollywood studio to feature a majority cast of Chinese descent in a modern setting since The Joy Luck Club in 1993) and Netflix's "Bling Empire " have undoubtedly increased Asian American representation in Hollywood, it is important to note that these films do play into stereotypes about the prevalence of extremely rich and successful Asian Americans. Of course, if there were more representation of Asian Americans in Hollywood, this would not be a concern—all communities deserve to be represented in a multitude of nuanced ways—but it is important to consider which portrayals of Asian Americans receive studio/Hollywood funding, win prestigious awards, and draw large audiences.

Video: The Complicated Discussion Surrounding Crazy Rich Asians . Quality Culture (2022).

The model minority myth manifests in television and film characters who are portrayed as one-dimensional nerds, high-achievers, and stoic, diligent workers. To keep learning about this myth, explore some the resources listed below:

- Video: Adam Ruins Everything—How America Created the “Model Minority” Myth (truTV)

- Video: Asian Americans: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO)

- Video: The Model Minority Trope, Explained (The Take)

- Video: The Origins of the Model Minority Myth (Project Lotus)

- Website: Deconstructing the Model Minority at UM (University of Michigan)

- Confronting Asian-American Stereotypes (Adeel Hassan, The New York Times)

Peterson, W. " Success Story, Japanese-American Style: Success Story, Japanese-American Style. " New York Times (1923-) , Jan 09, 1966, pp. 180 . ProQuest.

“ TIME Magazine Cover: Asian-American Whiz Kids - Aug. 31, 1987.” TIME.Com . Accessed 10 May 2023.

The Dragon Lady is a stereotype of Asian women, particularly East Asian women, as strong, deceitful, domineering, mysterious, and sexually alluring. The Dragon Lady might be seen wearing 'traditional' dress when no one else around her is, speaking in cryptic/flowery metaphors, or utilizing Asian fighting styles. The term comes from the U.S. comic strip "Terry and the Pirates," which featured a character called Dragon Lady, also known as Madam Deal .

Image: Terry and the Pirates: Enter the Dragon Lady . Milton Caniff (1975). Featuring the Dragon Lady, a character based on Lai Choi San , a 1900s Chinese pirate.

Inspired by the characters played by actress Anna May Wong , the term is often applied in opposition to the "Lotus Blossom" stereotype of an overly submissive and hyper-sexualized Asian woman. The Dragon Lady has often been used to refer to powerful Asian women—such as Soong Mei-ling (Madame Chiang Kai-shek) and Devika Rani —in a derogatory fashion. The term dragon lady is applied to Asian women and not to their non-Asian counterparts as Lucy Liu highlights in her discussion of Kill Bill: Volume I:

"Kill Bill' features three other female professional killers in addition to Ishii. Why not call Uma Thurman, Vivica A. Fox or Daryl Hannah a dragon lady? I can only conclude that it's because they are not Asian, I could have been wearing a tuxedo and a blond wig, but I still would have been labeled a dragon lady because of my ethnicity.

"Kill Bill," includes many female assassins but shows Liu's character committing her assassinations in traditional Japanese costume.

Images: Poster for Daughter of the Dragon (1931) and Anna May Wong as Princess Ling Moy.

The Dragon Lady trope has its roots in the Page Act of 1875 , a United States law which prohibited the immigration of “Oriental” laborers brought against their will or for “lewd and immoral purposes.” In practice, this law banned all East Asian women from entering the US. On the perception of Asian women during this time, Nancy Wang Yuen states: “They were characterized as potentially carrying sexual diseases. They were also characterized as being temptations for white men” ( qtd. in Pham 2021 ). The Dragon Lady is a result of centuries of Anti-Asian bias, yellow peril, and racist assumptions about Asian women. It is important to note that until recently, these were some of the only roles that Asian women in Hollywood were allowed to play—actors needed to take these positions lest they not be cast at all. The problem with the Dragon Lady stereotype is not that it depicts Asian women as strong, attractive, and mysterious, but that media would often refuse to show Asian women as anything else ( Pham, 2021 ). For more on the nuanced reality of this stereotype see Sarah Kuhn's article "Enter the Dragon Lady" and explore the resources listed below:

- Hollywood Played a Role in Hypersexualizing Asian Women (India Roby, Teen Vogue)

- Here's how pop culture has perpetuated harmful stereotypes of Asian women (Elise Pham, Today.com)

- Twitter thread (CAPE—Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment)

Video: Virtually Asian (English subtitles) . Astria Suparak, Berkeley Art Center (2021).

In 2020, Astria Suparak launched the " Asian futures, without Asians " series, a "a visual analysis of over half a century of American science fiction cinema. A multipart research project, it draws from the histories of art, architecture, design, fashion, film, food, and weaponry." In this series, Suparak analyzes how science fiction utilizes stereotypical Asian signifiers that serve as the backdrop for an almost exclusively white cast.

“The piece is part of a larger project examining 40 years of sci-fi films and how white filmmakers envision a future that is inflected by Asian culture but devoid of actual Asian people."

—Astria Suparak qtd, in " Asian-American Artists, Now Activists, Push Back Against Hate "

Learn more about Suparak's ongoing project and explore additional resources below:

- How Sci-Fi Films Use Asian Characters to Telegraph the Future While Also Dehumanizing Them (Evan Nicole Brown, The Hollywood Reporter).

- Orientalism, Cyberpunk 2077, and Yellow Peril in Science Fiction (George Yang, Wired). Cyberpunk as a genre, and Cyberpunk 2077 the game, are both rooted in a type of other-ization that can’t be ignored—but it can be examined.

- After Yang (Anna Maitland)

- Video: Techno-Orientalism with Dr. Terry K. Park (IU East)

Video: Yellowface is a bad look, Hollywood. Vox (2016).

Whitewashing is a casting practice in the film industry in which white actors are cast in non-white roles. Yellowface is a form of whitewashing where non-Asian actors are cast to play Asian characters. The practice of yellowface extends from the beginning of Hollywood to today. Famous early examples include Warner Oland playing Charlie Chan in "Charlie Chan Carries On" (1931) and Dr. Fu Manchu in "The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu" (1929). In the 1960s, Mickey Rooney wore yellowface to portray I. Y. Yunioshi in "Breakfast at Tiffany's" (1961). More recently, you might recall Scarlett Johansson , Pilou Asbæk, and Michael Pitt playing Japanese animated characters in "Ghost in the Shell" (2017), Emma Stone as Allison Ng in "Aloha" (2015), and white actors playing Asian and Inuit characters in the film adaptation of Avatar: The Last Airbender.

Images: (Left to right) Scarlett Johansson in "Ghost in a Shell" , Emma Stone in "Aloha" , and the cast of "The Last Airbender"

Whitewashing is prominent in Hollywood for Asian characters as well as any non-white characters. For an extensive list, check out this Wikipedia page. Many directors and producers are pressured by Hollywood executives to cast non-Asian actors in Asian roles. For example. Lulu Wang, the director of The Farewell (a film about here Chinese American family), has stated that many American financiers wanted to include a " prominent white character into the narrative, and punch up the nuanced drama to turn it into a broad comedy ."

To learn more about the history of whitewashing and yellowface, explore the resources below:

- Is a Disappointing Ghost in the Shell the Nail in the Coffin of Hollywood Whitewashing? (Joanna Robinson, Vanity Fair)

- When white actors play other races (Tom Brook, BBC)

- Yellowface, Whitewashing, and the History of White People Playing Asian Characters (Jenn Fang, TeenVogue)

- Video: The History of Yellowface (Teen Vogue)

The following are films by and featuring Asian directors, writers, and actors. For additional lists, see below:

- 11 Films by Asian American and Pacific Islander Directors to Fill Your May Days (Sundance Institute)

- Five AAPI Directors Who Are Refiguring American Cinema (Focus Features)

- 57 Asian Actors and Actresses in Hollywood You Should Know (Isis Briones, Tommy Taso, Kristi Kellogg, and Sara Li, Teen Vogue)

Content Warning: Gore

Video: Happy (Official Music Video) . Mitski (2016).

Asian Americans have been exploring media representation through their writing, music, cinema, and essays. Below is a small selection of books written by Asian Americans about the Asian American experience.

The Center for Asian American Media (CAAM)

is a nonprofit organization dedicated to presenting stories that convey the richness and diversity of Asian American experiences to the broadest audience possible. We do this by funding, producing, distributing and exhibiting works in film, television and digital media. For 40 years, CAAM has exposed audiences to new voices and communities, advancing our collective understanding of the American experience through programs specifically designed to engage the Asian American community and the public at large. CAAM has put together a collection titled "Memories to Light," a project to collect and digitize home movies and to share them–and the stories they tell—to a broad public.

Video: Memories to Light 2.0: The Bohulano Family . CAAMChannel (2014).

Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAAJ)

"Asian Americans have been part of the American story since its earliest days, and are now the U.S.'s fastest-growing racial group with the potential and power to shape our nation and the policies that affect us. Our mission is to advance civil and human rights for Asian Americans and to build and promote a fair and equitable society for all." Explore their Media Diversity Page .

Asian Film Archive: The Asian Film Archive was founded in January 2005 as a non-profit organisation to preserve the rich film heritage of Singapore and Asian Cinema, to encourage scholarly research on film, and to promote a wider critical appreciation of this art form.

- Introductory Texts

- Animals in Literature

- Animals in the Media

- Music, Podcasts, Miscellany

- Organizations & Movements

During April, we celebrate both Earth Month and Earth Day (April 26th). Earth Day has been celebrated since 1970 and marks the anniversary of the birth of the modern environmental movement . In celebration of this month and day, we have developed a guide focusing on human relationships with the non-human world. This feature will center on representation of animals in the media, literature, and culture. You will find poetry, nonfiction, and novels that allow you to witness how writers and creatives are thinking, and have been thinking, about human/non-human relations.

Image: Still from Hayao Miyazaki's My Neighbor Totoro (1988).

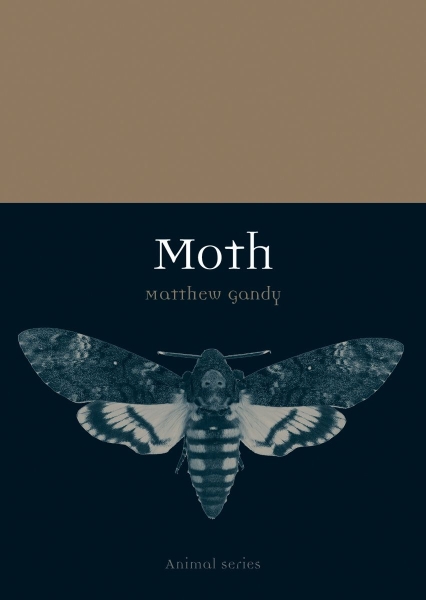

If you are looking to learn more about the history of a specific animal, look into The Animal Series from Reaktion Books which explores the natural history of animals alongside their historical and cultural impact on humankind. Each short book is a wonderful introduction to an animal with which you are probably familiar and maybe even encounter daily!

Image: The Animal Series from Reaktion Books. Moth , Hare , Nightingale , Lizard .

Check out our companion feature in the Philosophy guide for more information on the scholarly fields of Animal Studies and Critical Animal Studies, as well as other philosophies of the non-human.

If you'd like to explore more thematic content relevant to climate change, environmental justice, and nature, try the Environmental Justice & Earth Day feature , which includes music, novels, feature films, and documentaries on these topics, and the highlight on Environmental Ethics & Aesthetics at the Philosophy Research Guide .

From Winnie the Pooh to Moby Dick, animals can be found in a wide variety of novels, children's stories, folktales, and other writings from the medieval to contemporary eras. Literary animal studies explores the figurative significance of animals in literature, offering critical insight into the portrayal of animals in literature. Scholars discuss how writers represent animal experience in human language, whether it is truly possible to develop a non-anthropocentric mode of writing, and how representations of nonhuman subjects might affect our perception of certain species.

When exploring literary animal studies in IUCAT, try looking under the following subject headings: "Human animal relationships in literature" and "Animals in literature." See also: "Palgrave studies in animals and literature" series .

Images: (Left) The Cricket in Times Square . George Selden (1960). (Right): Author: Zakariya ibn Muhammad Qazwini (ca. 1203-1283), Scribe: Muhammad ibn Muhammad Shakir Ruzmah-'i Nathani. Illustration: A Wild Cat and an Animal Called Sirayis . 1121 AH/AD 1717 (Ottoman). Artstor.

Explore the following subject headings in IUCAT to learn more about animals and animal representation in the media:

- "Animals in motion pictures"

- "Animal films--History and criticism"

- "Animals in mass media"

- "Human animal relationships in mass media"

Image: Hachicko Statue in Tokyo, Japan . Go Tokyo.

Images: Album covers, clockwise from left to right: Alex G God Save the Animals ; Ia Clua & Jordi Batiste Chichonera’s Cat ; The Birdsong Project For The Birds : Vol. 1; Fiona Apple Fetch the Boltcutters ; Nyokabi Kariũki peace places: kenyan memories ; Pink Floyd Animals .

About the Playlist

The nonhuman world, including animals, have long captured the cultural and musical imaginations of people. In this playlist, we have curated a selection of songs about, referring to, or in any way inspired by our fellow critters, whether literally or symbolically. To learn more about the music we've included, the history of nonhuman animal references in music, and animals' own relationships with music, consult some of the resources below:

- "How Birds and Animals Have Inspired Classical Music" ( BBC Music )

- "The Specialist's Guide to Animals in Music" ( Gramophone )

- "Animals in Music" Playlist ( Naxos )

- "Readers Recommend: Songs About Animals" ( The Guardian )

- "Zoomusicology" ( Wikipedia )

- "Are Humans the Only Music Species?" ( MIT Press Reader )

- "Do Any Other Animals Play Music?" ( BBC Science Focus )

- "7 Scientific Studies About How Animals React to Music" ( Mental Floss )

Note : To enjoy the playlist in full, click on the white Spotify icon in the upper-right corner of the playlist, and press the "like" (♡) button in the application to save.

This American Life

- The Feather Heist A flute player breaks into a British museum and makes off with a million dollars worth of dead birds.

- Spark Bird Stories about birds and the hearts they sway, the havoc they wreak, the lives they change.

In Dog We Trust Exactly how much are the animals that live in our homes caught up in our everyday family dynamics?

Ologies with Alie Ward

- Chickenology (Hens & Roosters) Part 1 with Tove Danovich

- Diplopodology (Millipedes & Centipedes) with Dr. Derek Hennen

- Carnivore Ecology (Lions, Tigers, & Bears) with Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant

The Ezra Klein Show

- Mark Bittman Cooked Everything. Now He Wants to Change Everything The acclaimed food writer offers a sweeping indictment of our modern food system.

- The Hidden Costs of Cheap Meat The animal rights activist Leah Garcés discusses how modern meat production harms animals, people and the environment.

- A Conversation With Ada Limón, in Six Poems The award-winning poet shares how she stays open to wonder and beauty in a difficult world.

- For ‘Gender’, See ‘Turtles’: Experiments in Empathetic Biology (Callum Angus)

- excerpts from "every dog i pet in 2016" (joseph parker okay)

- Why I Write About Animals, or, My Body Is the Animal I Write About (Hannah Gamble)

Miscellany

There are many ways to get involved with Animal Rights and Environmental movements right here in and around Bloomington. From incorporating animal studies into your scholarship to donating money and participating in direct action campaigns, see the following list for organizations supporting animals and the environment in the Bloomington area:

- Bloomington Animal Shelter Run by Bloomington Animal Care and Control, whose mission is to address and respond to all animal needs in the community through education, enforcement and support in order to build a community where animals are valued and treated with kindness and respect. The Animal Shelter is accepting donations and foster applications.

- Monroe County Humane Association (MCHA) "Dedicated to promoting the welfare of animals, strengthening the human-animal bond, and providing access to veterinary care & humane education across our community."

- Sunrise Bloomington "We are a group of undergrads, grads, faculty, high schoolers and Bloomington community members who are dedicated to bringing about positive changes towards climate justice initiative through grassroots movement building!"

- IU Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Student Animal Legal Defense Fund was established at IU Maurer School of Law in 2010 to provide a forum for education, advocacy, and scholarship aimed at improving the lives of animals and advancing their interests through the legal system.

- BloomingVeg "An all-ages social and advocacy group for vegetarians, vegans, and veggie-lovers alike in Bloomington, Indiana."

- Indy VegFest A "nonprofit organization whose mission is to increase the public’s acceptance of the compassionate, environmental, and health facets of a vegan lifestyle through an annual event and year-round outreach and education opportunities."

- Rainbow Bakery Vegan bakery in Bloomington, IN.

- Vegan, Vegetarian & Gluten-Free Restaurants in Bloomington (Visit Bloomington)

- Uplands PEAK Sanctuary Indiana's first farmed animal sanctuary, providing lifelong care to their residents, educational tours, and volunteer opportunities.

The following are national organizations fighting for animal rights, liberation, and environmental justice. For more information on the impact of a few of the organizations listed below, check out Animal Charity Evaluators , which researches animal welfare organizations.

- Native American Humane Society "Shares our expertise to help tribal communities learn how to humanely manage and care for the animal populations in their own communities. NAHS connects tribal communities and animal welfare service providers, NGOs, foundations, and other agencies to assist tribal communities in resolving their challenges with animals through regular animal care, population management, and community activities."

- The Humane League "We exist to end the abuse of animals raised for food by influencing the policies of the world’s biggest companies, demanding legislation, and empowering others to take action and leave animals off their plates."

- Good Food Institute "A nonprofit think tank working to make the global food system better for the planet, people, and animals. Alongside scientists, businesses, and policymakers, GFI’s teams focus on making plant-based and cultivated meat delicious, affordable, and accessible."

- The Green New Deal Network "A coalition of grassroots organizations, labor, and climate and environmental justice organizations growing a movement to pass local, state, and national policies that create millions of family-sustaining union jobs, ensure racial and gender equity, and take action on climate at the scale and scope the crisis demands."

- Indigenous Environmental Network "IEN was formed by grassroots Indigenous peoples and individuals to address environmental and economic justice issues (EJ). IEN’s activities include building the capacity of Indigenous communities and tribal governments to develop mechanisms to protect our sacred sites, land, water, air, natural resources, health of both our people and all living things, and to build economically sustainable communities."

- Queerbaiting

- The Gay Best Friend

- Bury Your Gays

Welcome! In this feature, we will explore the representation of queer people in media, particularly in film and television. We will explore some common tropes/stereotypes, consider the use of representation as a concept, and track where queer representation has been and where it is going. The representation of queer people falls into categories: negative representation (harmful stereotypes that vilify and misrepresent the lives and motivations of queer folks), no representation (complete exclusion of queer people), token representation (virtue signalling through the placement of a queer character), queerbaiting (the inclusion of scenes that suggest a character might be LGBTQ+, while maintaining a distinct lack of evidence in the story to confirm or deny it), retroactive representation (when creators explicitly (and retroactively) claim that certain characters are LGBTQ+), idealistic representation (a depiction set in a world where queerness isn’t stigmatized or discriminated against), and complex representation (a nuanced, compelling depiction of queer characters that addresses the intersectional nature many queer folk's lived experiences). This feature considers a few of these representations and provides a selection of academic texts that may be helpful to your research on this or related topics.

In this feature, will highlight common tropes like The Gay Best Friend, Bury Your Gays, and Queerbaiting. Alongside these tropes, however, we highlight media that depicts nuanced and complex queer characters and reflections on queerness in the media (you will find these under the non-fiction, film, and television tabs).

For a brief history of queer cinema, check out the " Queer Film Classics " series by Arsenal Pulp Press. See a selection here:

From left to right: Winter Kept Us Warm , Paris is Burning , Anders Als Die Andern , Fire , and Midnight Cowboy

Further reading

- Queer representation in media: the good, the bad, and the ugly ( Tessa Kaur)

- Revision as Resistance: Fanfiction as an Empowering Community for Female and Queer Fans (Diana Koehm, UConn Honors thesis)

- A Real Gay Person: Representation and Stereotypes in Queer Romantic Comedies (Maja Hardikar, Georgetown University Master's Theses)

- Gaysploitation Upends the Stereotypes That Make Us Wince (Erik Piepenburg, The New York Times)

- A History of Queerness in Cinema with Alonso Duralde (Bulls Eye with Jesse Thorn, NPR)

- Placing the Queer Audience: Literature on Gender & Sexual Diversity in Film and TV Reception (Rob Cover & Duc Dau, Mai Feminism)

- After Decades In The Background, Queer Characters Step To The Front In Kids' Media (Victoria Whitley-Berry, NPR)

To get started with your research, explore the " Sexual minorities in mass media ," " Homosexuality in motion pictures ," and " Lesbianism in motion pictures " subject headings in IUCAT. If there is a book you are particularly interested in, scroll down on its catalog record to find its subject headings. You can then browse by subject heading and find books similar to the one that you have already identified.

For more films, see the following lists:

- 40 Essential LGBTQ+ Documentaries (Manuel Betancourt, Rotten Tomatoes)

- Pride Month Movie Guide: 30 Films By, For and About the LGBTQ+ Community (A.Frame)

- The 60 Best Queer Movies of All Time (Marley Marius, Liam Hess, Lisa Wong Macabasco, Emma Specter, Gia Yetikyel &Taylor Antrim, Vogue)

- The Trans Horror Masterlist (ashley, Letterboxd)

- Queer Films Everyone Must See (Zā, Letterboxd)

- A history of LGBTQ+ representation in film (Stacker)

Documentaries

For more shows, see the following lists:

- The 28 Best LGBTQ+ TV Shows to Stream Right Now (Tyler Breitfeller, Vanity Fair)

- The 25 Most Essential LGBTQ TV Shows of the 21st Century (Wilson Chapman, IndieWire)

- 39 binge-worthy LGBTQ TV shows to watch this Pride (Alison Foreman & Oliver Whitney, Mashable)

Queerbaiting is a (marketing) technique for fiction and entertainment in which creators hint at, but do not depict, queer romance or other LGBTQ+ representation. Queerbaiting attracts a queer/straight ally audience without isolation viewers who are opposed to seeing queer people in media. Some prominent characters that were used to queerbait fans include Dumbledore from Harry Potter, Finn and Poe from Star Wars, Holmes and Watson from Sherlock, numerous characters from the Marvel franchise , and Dean and Castiel from Supernatural. Subtext in general became popular in film in the 1930s when the Hays Code (guidelines for the self-censorship of content that was applied to most motion pictures released by major studios in the United States) limited what could be shown on screen. Today, queerbaiting is a way to keep media viewership up without actually representing queer people on screen, contribution to further marginalization of the LGBTQ+ community.

Further Reading

- The Problem With the Internet’s Obsession With Queerbaiting (James Factora, them)

- Queerbaiting: The (Mis)representation Of The Queer Community (Natalie Biele, odyssey)

- I s Celebrity ‘Queer Baiting’ Really Such a Crime? (Mark Harris, T Magazine)

- Is it ever OK to use the term queerbaiting? (Katie Baskerville, Mashable)

- How Do We Solve A Problem Like “Queerbaiting”?: On TV’s Not-So-Subtle Gay Subtext (rose, Autostraddle)

- 'Killing Eve', 'Dead to Me', and The Confusing State of Queerbaiting on TV (Jill Gutowitz, Cosmopolitan)

- Harry Potter and the History of Queerbaiting (Ellen Ricks, The Mary Sue)

- Is Disney continuing to queerbait fans with The Rise of Skywalker press tour? (Molly Catherine Turner, Culturess)

- Avengers: Endgame's Gay Representation Is Bullshit (Charles Pulliam-Moore, Gizmodo)

- Netflix’s Wednesday series sparks debate with LGBTQ+ viewers: ‘A metaphor for people in the closet’ (Asyia Iftikhar, PinkNews)

“Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore” Called Out for Erasing Queer Dialogue (Sara Li, Teen Vogue)

Video : The Evolution Of Queerbaiting: From Queercoding to Queercatching . Rowan Ellis (2019).

The Gay Best Friend is a trope where a gay male friend of the main character (often a straight woman) "exists mostly to add variety, funny mannerisms, and cheap laughs to an otherwise all-straight story" ("Gay Best Friend," TV Tropes ). Though the Gay Best Friend is often a stereotypical depiction of a gay man, the first Gay Best Friends were positive developments in queer representation, depicting queer people on screen at a time when representation was completely absent.

Video : The Gay Best Friend - How It Became a Stereotype . The Take (2021).

The Advocate writes, "often an important first step in introducing queer storylines to mainstream audiences, the GBF trope had a tendency to reinforce stereotypes about gay men: that their only interests are makeovers, shopping and drama, that their struggles and relationships fade into the background unless they're supporting a straight person's story, and that they only exist to be wise oracles about love and romance. In early film, the trope of the Sissy emerged as a way for filmmakers to code a character as queer (by depicting them as effeminate and outside of conventional masculinity) without explicitly stating the character's sexuality."

From more stereotypical depictions of effeminate white men, the gay best friend evolved to include characters of diverse identities and with deeper interior lives. For example, Wilson Cruz (right) played the character Rickie Vasquez in My So-Called Life. Cruz was the first openly gay actor to play an openly gay character in a leading role in an American television show.

- A History of the Gay Best Friend in Film and TV (Advocate)

- Missing the Gay Best Friend ( Mark Harris, T Magazine)

- The Evolution Of The “Gay Best Friend,” From Harmful Trope To TV Gold (Dylan Kickham, Elite Daily)

- Rethinking the ‘gay best friend’ (Caroline O’Donoghue, The Guardian)

The Bury Your Gays trope refers to the presentation of excessive deaths of LGBTQ+ characters, depicting these characters as more expendable than their heterosexual counterparts. This trope is related to the sad gay movie (which depicts queer characters in extremely traumatic situations, heartbreaking coming out stories, general suffering, etc.).

Video: The "Bury Your Gays" Trope, Explained . The Take (2020).

Studies have show that, in aggregate , queer characters are more likely to die than straight characters. "Indeed, it may be because they seem to have less purpose compared to straight characters, or that the supposed natural conclusion of their story is an early death" (Bury your gays, TV tropes ). "Though the term has been widely attributed to any queer character that meets a tragic fate in media, the history it stems from is one where the characters are punished and killed specifically for the sin of being gay on screen" (Hardikar 4-5). This trope is so prevalent that the website " Does an LGBT Person Die " warns viewers of when a queer person will die in a film or television show.

- Queer women have been killed on television for decades. Now The 100's fans are fighting back (Caroline Framke, Vox)

- All 235 Dead Lesbian and Bisexual Characters On TV, And How They Died (Riese, Autostraddle)

- 'Bury Your Gays': Why Are So Many Lesbian TV Characters Dying Off? (Alamin Yohannes, NBC News)

- 15 Recent, Especially Brutal, Examples of the Bury Your Gays Trope (Mey Rude, Out)

- Hollywood's "Bury Your Gays" Trope Explained: History & Controversy (Emily Clute, Screen Rant)

- Bury Your Gays: History, Usage, and Context Hulan, Haley (2017) "Bury Your Gays: History, Usage, and Context," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 21: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol21/iss1/6

- The “Bury Your Gays” Trope in Contemporary Television: Generational Shifts in Production Responses to Audience Dissent Cover, Rob; Milne, Cassandra. 2023. The “Bury Your Gays” Trope in Contemporary Television: Generational Shifts in Production Responses to Audience Dissent.” The Journal of Popular Culture 56 (5-6): 810–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.13255.

Source: Hardikar, M. (2023). A Real Gay Person: Representation and Stereotypes in Queer Romantic Comedies . Georgetown University.

- << Previous: Collection & Subject Spotlights

- Next: Other Features >>

- Last Updated: Sep 13, 2024 2:35 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.indiana.edu/mediastudies

Social media

- Instagram for Herman B Wells Library

- Facebook for IU Libraries

Additional resources

Featured databases.

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) OneSearch@IU

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) Academic Search (EBSCO)

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) ERIC (EBSCO)

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) Nexis Uni

- Resource available without restriction HathiTrust Digital Library

- Databases A-Z

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) Google Scholar

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) JSTOR

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) Web of Science

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) Scopus

- Resource available to authorized IU Bloomington users (on or off campus) WorldCat

IU Libraries

- Diversity Resources

- About IU Libraries

- Alumni & Friends

- Departments & Staff

- Jobs & Libraries HR

- Intranet (Staff)

- IUL site admin

Mass Media Representation, Identity-Building and Social Conflicts: Towards a Recognition-Theoretical Approach

Cite this chapter.

- Rousiley C. M. Maia 2

289 Accesses

1 Citations

Since its inception, mass media has become a crucial site of struggle. By surveying television dramas, films, journalism, commercial and non-commercial advertisements, etc., a number of scholars have attempted to understand social conflict through approaches such as the “struggle around the image” (Hall, 1997b, p. 257), “struggle over representation” (Shohat & Stam, 1994, p. 178), “struggles for and over social and cultural life” (Gray, 1995, p. 55; see also, Larson, 2006, p. 14). The mass media is also seen as a “site of ideological-democratic struggle” (Carpentier, 2011) and an “arena” for civic debate (Butsch, 2007; Dahlgren & Sparks, 1993; Ferree, Gamson, Gerhards, & Rucht, 2002; Gomes & Maia, 2008; Maia, 2008, 2012a; Norris, 2000; Page, 1996; Peters, 2008; Wessler & Schultz, 2007; Wessler, Peters, Brüggemann, Königslöw & Sifft, 2008).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Audiences and Readership of Revolutionary Leftist Media: The “Media Leader” Hypothesis

Social Media as Civic Space for Media Criticism and Journalism Hate

The Donald: Media, Celebrity, Authenticity, and Accountability

Author information, authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Communication, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil

Rousiley C. M. Maia ( Associate Professor )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© 2014 Rousiley C.M. Maia

About this chapter

Maia, R.C.M. (2014). Mass Media Representation, Identity-Building and Social Conflicts: Towards a Recognition-Theoretical Approach. In: Recognition and the Media. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137310439_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137310439_3

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-45664-2

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-31043-9

eBook Packages : Palgrave Political Science Collection Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Media constructions of culture, race, and ethnicity.

- Travis L. Dixon , Travis L. Dixon Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Kristopher R. Weeks Kristopher R. Weeks Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- , and Marisa A. Smith Marisa A. Smith Department of Communication, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.502

- Published online: 23 May 2019

Racial stereotypes flood today’s mass media. Researchers investigate these stereotypes’ prevalence, from news to entertainment. Black and Latino stereotypes draw particular concern, especially because they misrepresent these racial groups. From both psychological and sociological perspectives, these misrepresentations can influence how people view their racial group as well as other groups. Furthermore, a racial group’s lack of representation can also reduce the group’s visibility to the general public. Such is the case for Native Americans and Asian Americans.

Given mass media’s widespread distribution of black and Latino stereotypes, most research on mediated racial portrayals focuses on these two groups. For instance, while black actors and actresses appear often in prime-time televisions shows, black women appear more often in situational comedies than any other genre. Also, when compared to white actors and actresses, television casts blacks in villainous or despicable roles at a higher rate. In advertising, black women often display Eurocentric features, like straight hair. On the other hand, black men are cast as unemployed, athletic, or entertainers. In sports entertainment, journalists emphasize white athletes’ intelligence and black athletes’ athleticism. In music videos, black men appear threatening and sport dark skin tones. These music videos also sexualize black women and tend to emphasize those with light skin tones. News media overrepresent black criminality and exaggerate the notion that blacks belong to the undeserving poor class. Video games tend to portray black characters as either violent outlaws or athletic.

While mass media misrepresent the black population, it tends to both misrepresent and underrepresent the Latino population. When represented in entertainment media, Latinos assume hypersexualized roles and low-occupation jobs. Both news and entertainment media overrepresent Latino criminality. News outlets also overly associate Latino immigration with crime and relate Latino immigration to economic threat. Video games rarely portray Latino characters.

Creators may create stereotypic content or fail to fairly represent racial and ethnic groups for a few reasons. First, the ethnic blame discourse in the United States may influence creators’ conscious and unconscious decision-making processes. This discourse contends that the ethnic and racial minorities are responsible for their own problems. Second, since stereotypes appeal to and are easily processed by large general audiences, the misrepresentation of racial and ethnic groups facilitates revenue generation. This article largely discusses media representations of blacks and Latinos and explains the implications of such portrayals.

- content analysis

- African American portrayals

- Latino portrayals

- ethnic blame discourse

- structural limitations and economic interests

- social identity theory

- Clark’s Stage Model of Representations

Theoretical Importance of Media Stereotypes

Media constructions of culture, race, and ethnicity remain important to study because of their potential impact on both sociological and psychological phenomena. Specifically, researchers have utilized two major theoretical constructs to understand the potential impact of stereotyping: (a) priming and cognitive accessibility (Dixon, 2006 ; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007 ; Shrum, 2009 ), and (b) social identity and social categorization theory (Mastro, 2004 ; Mastro, Behm-Morawitz, & Kopacz, 2008 ; Tajfel & Turner, 2004 ).

Priming and Cognitive Accessibility

Priming and cognitive accessibility suggests that media consumption encourages the creation of mental shortcuts used to make relevant judgments about various social issues. For example, if a news viewer encounters someone cognitively related to a given stereotype, he or she might make a judgment about that person based on repeated exposure to the mediated stereotype. As an illustration, repeated exposure to the Muslim terrorist stereotype may lead news viewers to conclude that all Muslims are terrorists. This individual may also support punitive policies related to this stereotype, such as a Muslim ban on entry to the United States. Therefore, this cognitive linkage influences race and crime judgments (e.g., increased support for criminalizing Muslims and deporting them).

Social Identity Theory and Media Judgments

Other scholars have noted that our own identities are often tied to how people perceive their groups’ relationships to other groups. Social categorization theory argues that the higher the salience of the category to the individual, the greater the in-group favoritism one will demonstrate. Media scholars demonstrated that exposure to a mediated out-group member can increase in-group favoritism (Mastro, 2004 ). For example, researchers found that negative stories about Latino immigrants can contribute to negative out-group emotions that lead to support for harsher immigration laws (Atwell Seate & Mastro, 2016 , 2017 ).

Both the priming/cognitive accessibility approach and the social identity approach demonstrate that cultural stereotypes have significant implications for our psychology, social interactions, and policymaking. It remains extremely important for us to understand the nature and frequency of mediated racial and ethnic stereotypes to further our understanding of how these stereotypes impact viewers. This article seeks to facilitate our understanding.

Stage Model of Representation

In order to provide the reader with an introduction to this topic, this article relies on the published content-analytic literature regarding race and media. Clark’s Stage Model of Representation articulates a key organizing principle for understanding how media may construct various depictions of social groups (Clark, 1973 ; Harris, 2013 ). This model purports that race/ethnic groups move through four stages of representation in the media. In the first stage, invisibility or non-recognition , a particular race or ethnic group rarely appears on the screen at all. In the second stage, ridicule , a racial group will appear more frequently, yet will be depicted in consistently stereotypical ways. In the third stage, regulation , an ethnic group might find themselves depicted primarily in roles upholding the social order, such as judges or police officers. Finally, a particular social group reaches the respect stage in which members of the group occupy diverse and nuanced roles. Given Clark’s model, this article contends that Native Americans and Asian Americans tend to fall into the non-recognition stage (Harris, 2013 ). It follows that few empirical studies have investigated these groups because empirical content analyses have difficulty scientifically assessing phenomena that lack presence (Krippendorff, 2004 ).

Bearing in mind Clark’s stages, Latinos appear to vacillate between non-recognition and ridicule. Meanwhile, blacks move between the ridicule and regulation stages, while whites remain permanently fixed in the respect stage. In other words, in this article, our lack of deep consideration of Native Americans and Asian Americans is rooted in a lack of representation which generates few empirical studies and thus leaves us little to review. The article offers a quick overview of their portrayal and then moves on to describe the social groups that receive more media and empirical attention.

Native American and Asian American Depictions

Although severely underrepresented, there are a few consistent stereotypical portrayals that regularly emerge for these groups. In some ways, both Native American and Asian Americans are often relegated to “historical” and/or fetishized portrayals (Lipsitz, 1998 ). Native American “savage” imagery was commonly depicted in Westerns and has been updated with images of alcoholism, along with depictions of shady Native American casino owners (Strong, 2004 ). Many news images of Native Americans tend to focus on Native festivals, relegating this group to a presentation as “mysterious” spiritual people (Heider, 2000 ). Meanwhile, various school and professional team mascots embody the savage Native American Warrior trope (Strong, 2004 ).

Asian Americans overall have often been associated with being the model minority (Harris, 2009 ; Josey, Hurley, Hefner, & Dixon, 2009 ). They typically represent “successful” non-whites. Specifically, media depictions associate Asian American men with technology and Asian American women with sexual submissiveness (Harris & Barlett, 2009 ; Schug, Alt, Lu, Gosin, & Fay, 2017 ).

Overall, scholars know very little about how either of these groups are regularly portrayed based on empirical research, although novelists and critical scholars have offered useful critiques (Wilson, Gutiérrez, & Chao, 2003 ). Hopefully, future quantitative content analyses will further delineate the nature of Native American and Asian American portrayals. Consider the discussion about entertainment, news, and digital imagery of blacks, Latinos, and whites presented in the next section.

Entertainment Constructions of Race, Culture, and Ethnicity

Entertainment media receives a great deal of consideration, given that Americans spend much of their time using media for entertainment purposes (Harris, 2013 ; Sparks, 2016 ). This section begins with an analysis of black portrayals, then moves on to Latino portrayals to understand the prevalence of stereotyping . When appropriate, black and Latino representations are compared to white ones. Two measures describe a group’s representation: (a) the numerical presence of a particular racial/ethnic group, and (b) the distribution of roles or stereotypes regarding each group. When researchers have often engaged in examinations of race they typically begin by comparing African American portrayals to white portrayals (Entman & Rojecki, 2000 ). As a result, there is a substantial amount of research on black portrayals.

Black Entertainment Television Imagery

Overall, a number of studies have found that blacks receive representation in prime-time television at parity to their actual proportion in the US population with their proportion ranging from 10% to 17% of prime-time characters (Mastro & Greenberg, 2000 ; Signorielli, 2009 ; Tukachinsky, Mastro, & Yarchi, 2015 ). African Americans currently compose approximately 13% of the US population (US Census Bureau, 2018 ). When considering the type of characters (e.g., major or minor) portrayed by this group, the majority of black (61%) cast members land roles as major characters (Monk-Turner, Heiserman, Johnson, Cotton, & Jackson, 2010 ). Black women also fare well in these representations, accounting for 73% of black appearances on prime-time television (Monk-Turner et al., 2010 ).

However, recent content analyses reveal an instability in black prime-time television representation over the last few decades. Tukachinsky et al. ( 2015 ) found that the prevalence of black characters dropped in 1993 and remain diminished compared to previous decades. Similarly, Signorielli ( 2009 ) found a significant linear decrease in the proportion of black representation from 2001 (17%) to 2008 (12%). Signorielli ( 2009 ) attributes this decrease in black representation to the decrease in situation comedy programming. Indeed, African Americans appear most frequently in situation comedies. Sixty percent of black women featured in prime-time television are cast in situation comedies, and 25% of black male prime-time portrayals occur in situation comedies (Signorielli, 2009 ). However, between 2001 and 2008 , situational comedies decreased, while action and crime programs increased.

The previously discussed analyses describe the frequency of black representation. However, frequent depictions do not equate to favorable representation. Considering role quality (i.e., respectability) and references made to stereotypes, entertainment media offers a mixed bag. On the one hand, some recent analyses found that the majority of blacks are depicted as likable, and as “good characters,” as opposed to “bad character”-like villains (Tukachinsky, Mastro, & Yarchi, 2015 ). In addition, the majority of black characters are depicted as intelligent (Tukachinsky et al., 2015 ). On the other hand, the rate of blacks shown as immoral and despicable (9%) is higher than that of whites (2% and 3%, respectively) (Monk-Turner et al., 2010 ). In addition, black depictions exhibiting high social status and professionalism trended downward. Between 2003 and 2005 , higher status depictions reached their peak at 74.3% but sharply fell in subsequent years to 31.5%, with black women faring worse than black men (Tukachinsky et al., 2015 ). Classic studies of entertainment representations found that blacks tend to be the most negatively represented of any race or ethnic group, often being depicted as lazy and disheveled (Mastro & Greenberg, 2000 ). Overall, black characters tend to be portrayed in less respectful ways compared to whites in content intended for general audiences, although they sometime fare better when the targeted audience is African American (Messineo, 2008 ). For example, crime drama television frequently depicts white women as at risk for murder, but FBI statistics demonstrate that murder victims are more often likely to be black males (Parrott & Parrott, 2015 ).

Black Representations in Magazines and Advertising

African Americans remain well represented in magazines, though they are not as prominent in this medium as in television (Schug et al., 2017 ). Moreover, the trend in the representation of African Americans, particularly women, appears to be improving (Covert & Dixon, 2008 ). Images of black women represent 6% of advertisements in women’s magazines and 4% of advertisements in men’s magazines (Baker, 2005 ). However, both black-oriented and white-oriented magazines appear to advance portrayals of black women with Eurocentric rather than Afrocentric features, referencing whiteness as a beauty standard. Overall, compared to black-oriented magazines, white-oriented magazines feature more black women with fair skin and thin figures. Black-oriented magazines feature more black women with straight hair. Moreover, straight hair textures outnumber other natural styles (i.e., wavy, curly, or braided) in both white- and black-oriented magazines.

Conversely, black men typically assume unemployed, athletic, or entertainment roles in these ads (Bailey, 2006 ). Moreover, mainstream magazines are most likely to depict black men as unemployed. Meanwhile, black-oriented magazines tend to portray African Americans in more managerial roles.

Black Representations in Sports Entertainment

Besides prime-time television, black stereotypes in sports coverage and music receive substantial attention in the literature. The unintelligent or “dumb” yet naturally talented black athlete remains a programming staple (Angelini, Billings, MacArthur, Bissell, & Smith, 2014 ; Rada & Wulfemeyer, 2005 ). For example, Angelini et al. ( 2014 ) found that black athletes receive less success-based comments related to intelligence than white athletes (Angelini et al., 2014 ). The findings echo previous research arguing that black athletes receive fewer positive comments regarding their intelligence than do white athletes (Rada & Wulfemeyer, 2005 ). Fairly similar depictions exist in broadcast commentary (Primm, DuBois, & Regoli, 2007 ). For example, Mercurio and Filak ( 2010 ) content-analyzed descriptions of NFL quarterback prospects featured on the Sports Illustrated website from 1998 to 2007 . The descriptions portray black athletes as possessing physical abilities while lacking intelligence . Conversely, Sports Illustrated described white prospects as intelligent but lacking in athleticism.

Black Representations in Music Videos

Music videos tend to sexualize black women, reinforcing the black jezebe l stereotype (i.e., a sassy African American woman who is sexually promiscuous) (Givens & Monahan, 2005 ). Also, black men appear aggressive and violent in music videos (e.g., like a criminal, thug, or brute ) (Ford, 1997 ). According to rap research, blacks appear in provocative clothes at a higher rate than whites, and black women are the most provocatively dressed in music videos (Turner, 2011 ). Even black female artists are twice as likely to wear provocative clothing than are white female artists (Frisby & Aubrey, 2012 ). Furthermore, Zhang, Dixon, and Conrad ( 2010 ) and Conrad, Zhang, and Dixon ( 2009 ) found that black women appeared in rap videos as sexualized, thin, and light-skinned while black men appeared dark-skinned and threatening .

Latino Entertainment Television Representation

Unlike African Americans, Latinos remain significantly underrepresented in English-language television outlets. For instance, Tukachinsky et al. ( 2015 ) found that of all characters, the number of Latino characters was less than 1% in the 1980s and increased to over 3% in the 2000s. However, these numbers fall significantly below the proportion of people who are Latino within the United States (about 18%) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018 ). Similarly, Signorelli ( 2009 ) also found that the percentage of Latinos in the United States Latino population and the percentage of Latino characters in prime-time programming differed by approximately 10%.

Latinos continue to be underrepresented in a variety of genres and outlets. For instance, Latinos remain consistently underrepresented in gay male blogs. For example, Grimm and Schwarz ( 2017 ) found that white gay models (80.2%) were most prevalent, followed by black gay models (4.5%). However, Latino models were the least prevalent (1.5%). In addition, Hetsroni ( 2009 ) found that the Latino population makes up 14% of patients in real hospitals, yet they only comprise 4% of the patients in hospital dramas. Conversely, whites make up 72% of real patients but comprise 80% of hospital drama patients.

Latino Underrepresentation in Advertising

Latino underrepresentation extends to the advertising realm. For example, Seelig ( 2007 ) determined that there was a significant difference between the Latino proportion of the US population and the Latino proportion of models found in mainstream magazines (1%). Another study that investigated Superbowl commercials conducted by Brooks, Bichard, and Craig ( 2016 ) found that only 1.22% of the characters were Latino.

Prominent Stereotypes of Latinos in Entertainment Media

Although underrepresented, Latinos are also stereotypically represented in entertainment media. For example, Tukachinsky et al. ( 2015 ) discovered that over 24% of Latino characters were hypersexualized in prime-time television. Furthermore, Latinos tended to occupy low-professional-status roles. This trend also occurred more often with Latina females than Latino males.