How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.

Hugo Sarrazin: It is surprising how often people jump past this step and make a bunch of assumptions. The most powerful thing is to step back and ask the basic questions—“What are we trying to solve? What are the constraints that exist? What are the dependencies?” Let’s make those explicit and really push the thinking and defining. At McKinsey, we spend an enormous amount of time in writing that little statement, and the statement, if you’re a logic purist, is great. You debate. “Is it an ‘or’? Is it an ‘and’? What’s the action verb?” Because all these specific words help you get to the heart of what matters.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

Simon London: So this is a concise problem statement.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah. It’s not like “Can we grow in Japan?” That’s interesting, but it is “What, specifically, are we trying to uncover in the growth of a product in Japan? Or a segment in Japan? Or a channel in Japan?” When you spend an enormous amount of time, in the first meeting of the different stakeholders, debating this and having different people put forward what they think the problem definition is, you realize that people have completely different views of why they’re here. That, to me, is the most important step.

Charles Conn: I would agree with that. For me, the problem context is critical. When we understand “What are the forces acting upon your decision maker? How quickly is the answer needed? With what precision is the answer needed? Are there areas that are off limits or areas where we would particularly like to find our solution? Is the decision maker open to exploring other areas?” then you not only become more efficient, and move toward what we call the critical path in problem solving, but you also make it so much more likely that you’re not going to waste your time or your decision maker’s time.

How often do especially bright young people run off with half of the idea about what the problem is and start collecting data and start building models—only to discover that they’ve really gone off half-cocked.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah.

Charles Conn: And in the wrong direction.

Simon London: OK. So step one—and there is a real art and a structure to it—is define the problem. Step two, Charles?

Charles Conn: My favorite step is step two, which is to use logic trees to disaggregate the problem. Every problem we’re solving has some complexity and some uncertainty in it. The only way that we can really get our team working on the problem is to take the problem apart into logical pieces.

What we find, of course, is that the way to disaggregate the problem often gives you an insight into the answer to the problem quite quickly. I love to do two or three different cuts at it, each one giving a bit of a different insight into what might be going wrong. By doing sensible disaggregations, using logic trees, we can figure out which parts of the problem we should be looking at, and we can assign those different parts to team members.

Simon London: What’s a good example of a logic tree on a sort of ratable problem?

Charles Conn: Maybe the easiest one is the classic profit tree. Almost in every business that I would take a look at, I would start with a profit or return-on-assets tree. In its simplest form, you have the components of revenue, which are price and quantity, and the components of cost, which are cost and quantity. Each of those can be broken out. Cost can be broken into variable cost and fixed cost. The components of price can be broken into what your pricing scheme is. That simple tree often provides insight into what’s going on in a business or what the difference is between that business and the competitors.

If we add the leg, which is “What’s the asset base or investment element?”—so profit divided by assets—then we can ask the question “Is the business using its investments sensibly?” whether that’s in stores or in manufacturing or in transportation assets. I hope we can see just how simple this is, even though we’re describing it in words.

When I went to work with Gordon Moore at the Moore Foundation, the problem that he asked us to look at was “How can we save Pacific salmon?” Now, that sounds like an impossible question, but it was amenable to precisely the same type of disaggregation and allowed us to organize what became a 15-year effort to improve the likelihood of good outcomes for Pacific salmon.

Simon London: Now, is there a danger that your logic tree can be impossibly large? This, I think, brings us onto the third step in the process, which is that you have to prioritize.

Charles Conn: Absolutely. The third step, which we also emphasize, along with good problem definition, is rigorous prioritization—we ask the questions “How important is this lever or this branch of the tree in the overall outcome that we seek to achieve? How much can I move that lever?” Obviously, we try and focus our efforts on ones that have a big impact on the problem and the ones that we have the ability to change. With salmon, ocean conditions turned out to be a big lever, but not one that we could adjust. We focused our attention on fish habitats and fish-harvesting practices, which were big levers that we could affect.

People spend a lot of time arguing about branches that are either not important or that none of us can change. We see it in the public square. When we deal with questions at the policy level—“Should you support the death penalty?” “How do we affect climate change?” “How can we uncover the causes and address homelessness?”—it’s even more important that we’re focusing on levers that are big and movable.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Simon London: Let’s move swiftly on to step four. You’ve defined your problem, you disaggregate it, you prioritize where you want to analyze—what you want to really look at hard. Then you got to the work plan. Now, what does that mean in practice?

Hugo Sarrazin: Depending on what you’ve prioritized, there are many things you could do. It could be breaking the work among the team members so that people have a clear piece of the work to do. It could be defining the specific analyses that need to get done and executed, and being clear on time lines. There’s always a level-one answer, there’s a level-two answer, there’s a level-three answer. Without being too flippant, I can solve any problem during a good dinner with wine. It won’t have a whole lot of backing.

Simon London: Not going to have a lot of depth to it.

Hugo Sarrazin: No, but it may be useful as a starting point. If the stakes are not that high, that could be OK. If it’s really high stakes, you may need level three and have the whole model validated in three different ways. You need to find a work plan that reflects the level of precision, the time frame you have, and the stakeholders you need to bring along in the exercise.

Charles Conn: I love the way you’ve described that, because, again, some people think of problem solving as a linear thing, but of course what’s critical is that it’s iterative. As you say, you can solve the problem in one day or even one hour.

Charles Conn: We encourage our teams everywhere to do that. We call it the one-day answer or the one-hour answer. In work planning, we’re always iterating. Every time you see a 50-page work plan that stretches out to three months, you know it’s wrong. It will be outmoded very quickly by that learning process that you described. Iterative problem solving is a critical part of this. Sometimes, people think work planning sounds dull, but it isn’t. It’s how we know what’s expected of us and when we need to deliver it and how we’re progressing toward the answer. It’s also the place where we can deal with biases. Bias is a feature of every human decision-making process. If we design our team interactions intelligently, we can avoid the worst sort of biases.

Simon London: Here we’re talking about cognitive biases primarily, right? It’s not that I’m biased against you because of your accent or something. These are the cognitive biases that behavioral sciences have shown we all carry around, things like anchoring, overoptimism—these kinds of things.

Both: Yeah.

Charles Conn: Availability bias is the one that I’m always alert to. You think you’ve seen the problem before, and therefore what’s available is your previous conception of it—and we have to be most careful about that. In any human setting, we also have to be careful about biases that are based on hierarchies, sometimes called sunflower bias. I’m sure, Hugo, with your teams, you make sure that the youngest team members speak first. Not the oldest team members, because it’s easy for people to look at who’s senior and alter their own creative approaches.

Hugo Sarrazin: It’s helpful, at that moment—if someone is asserting a point of view—to ask the question “This was true in what context?” You’re trying to apply something that worked in one context to a different one. That can be deadly if the context has changed, and that’s why organizations struggle to change. You promote all these people because they did something that worked well in the past, and then there’s a disruption in the industry, and they keep doing what got them promoted even though the context has changed.

Simon London: Right. Right.

Hugo Sarrazin: So it’s the same thing in problem solving.

Charles Conn: And it’s why diversity in our teams is so important. It’s one of the best things about the world that we’re in now. We’re likely to have people from different socioeconomic, ethnic, and national backgrounds, each of whom sees problems from a slightly different perspective. It is therefore much more likely that the team will uncover a truly creative and clever approach to problem solving.

Simon London: Let’s move on to step five. You’ve done your work plan. Now you’ve actually got to do the analysis. The thing that strikes me here is that the range of tools that we have at our disposal now, of course, is just huge, particularly with advances in computation, advanced analytics. There’s so many things that you can apply here. Just talk about the analysis stage. How do you pick the right tools?

Charles Conn: For me, the most important thing is that we start with simple heuristics and explanatory statistics before we go off and use the big-gun tools. We need to understand the shape and scope of our problem before we start applying these massive and complex analytical approaches.

Simon London: Would you agree with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: I agree. I think there are so many wonderful heuristics. You need to start there before you go deep into the modeling exercise. There’s an interesting dynamic that’s happening, though. In some cases, for some types of problems, it is even better to set yourself up to maximize your learning. Your problem-solving methodology is test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, and iterate. That is a heuristic in itself, the A/B testing that is used in many parts of the world. So that’s a problem-solving methodology. It’s nothing different. It just uses technology and feedback loops in a fast way. The other one is exploratory data analysis. When you’re dealing with a large-scale problem, and there’s so much data, I can get to the heuristics that Charles was talking about through very clever visualization of data.

You test with your data. You need to set up an environment to do so, but don’t get caught up in neural-network modeling immediately. You’re testing, you’re checking—“Is the data right? Is it sound? Does it make sense?”—before you launch too far.

Simon London: You do hear these ideas—that if you have a big enough data set and enough algorithms, they’re going to find things that you just wouldn’t have spotted, find solutions that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of. Does machine learning sort of revolutionize the problem-solving process? Or are these actually just other tools in the toolbox for structured problem solving?

Charles Conn: It can be revolutionary. There are some areas in which the pattern recognition of large data sets and good algorithms can help us see things that we otherwise couldn’t see. But I do think it’s terribly important we don’t think that this particular technique is a substitute for superb problem solving, starting with good problem definition. Many people use machine learning without understanding algorithms that themselves can have biases built into them. Just as 20 years ago, when we were doing statistical analysis, we knew that we needed good model definition, we still need a good understanding of our algorithms and really good problem definition before we launch off into big data sets and unknown algorithms.

Simon London: Step six. You’ve done your analysis.

Charles Conn: I take six and seven together, and this is the place where young problem solvers often make a mistake. They’ve got their analysis, and they assume that’s the answer, and of course it isn’t the answer. The ability to synthesize the pieces that came out of the analysis and begin to weave those into a story that helps people answer the question “What should I do?” This is back to where we started. If we can’t synthesize, and we can’t tell a story, then our decision maker can’t find the answer to “What should I do?”

Simon London: But, again, these final steps are about motivating people to action, right?

Charles Conn: Yeah.

Simon London: I am slightly torn about the nomenclature of problem solving because it’s on paper, right? Until you motivate people to action, you actually haven’t solved anything.

Charles Conn: I love this question because I think decision-making theory, without a bias to action, is a waste of time. Everything in how I approach this is to help people take action that makes the world better.

Simon London: Hence, these are absolutely critical steps. If you don’t do this well, you’ve just got a bunch of analysis.

Charles Conn: We end up in exactly the same place where we started, which is people speaking across each other, past each other in the public square, rather than actually working together, shoulder to shoulder, to crack these important problems.

Simon London: In the real world, we have a lot of uncertainty—arguably, increasing uncertainty. How do good problem solvers deal with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: At every step of the process. In the problem definition, when you’re defining the context, you need to understand those sources of uncertainty and whether they’re important or not important. It becomes important in the definition of the tree.

You need to think carefully about the branches of the tree that are more certain and less certain as you define them. They don’t have equal weight just because they’ve got equal space on the page. Then, when you’re prioritizing, your prioritization approach may put more emphasis on things that have low probability but huge impact—or, vice versa, may put a lot of priority on things that are very likely and, hopefully, have a reasonable impact. You can introduce that along the way. When you come back to the synthesis, you just need to be nuanced about what you’re understanding, the likelihood.

Often, people lack humility in the way they make their recommendations: “This is the answer.” They’re very precise, and I think we would all be well-served to say, “This is a likely answer under the following sets of conditions” and then make the level of uncertainty clearer, if that is appropriate. It doesn’t mean you’re always in the gray zone; it doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view. It just means that you can be explicit about the certainty of your answer when you make that recommendation.

Simon London: So it sounds like there is an underlying principle: “Acknowledge and embrace the uncertainty. Don’t pretend that it isn’t there. Be very clear about what the uncertainties are up front, and then build that into every step of the process.”

Hugo Sarrazin: Every step of the process.

Simon London: Yeah. We have just walked through a particular structured methodology for problem solving. But, of course, this is not the only structured methodology for problem solving. One that is also very well-known is design thinking, which comes at things very differently. So, Hugo, I know you have worked with a lot of designers. Just give us a very quick summary. Design thinking—what is it, and how does it relate?

Hugo Sarrazin: It starts with an incredible amount of empathy for the user and uses that to define the problem. It does pause and go out in the wild and spend an enormous amount of time seeing how people interact with objects, seeing the experience they’re getting, seeing the pain points or joy—and uses that to infer and define the problem.

Simon London: Problem definition, but out in the world.

Hugo Sarrazin: With an enormous amount of empathy. There’s a huge emphasis on empathy. Traditional, more classic problem solving is you define the problem based on an understanding of the situation. This one almost presupposes that we don’t know the problem until we go see it. The second thing is you need to come up with multiple scenarios or answers or ideas or concepts, and there’s a lot of divergent thinking initially. That’s slightly different, versus the prioritization, but not for long. Eventually, you need to kind of say, “OK, I’m going to converge again.” Then you go and you bring things back to the customer and get feedback and iterate. Then you rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. There’s a lot of tactile building, along the way, of prototypes and things like that. It’s very iterative.

Simon London: So, Charles, are these complements or are these alternatives?

Charles Conn: I think they’re entirely complementary, and I think Hugo’s description is perfect. When we do problem definition well in classic problem solving, we are demonstrating the kind of empathy, at the very beginning of our problem, that design thinking asks us to approach. When we ideate—and that’s very similar to the disaggregation, prioritization, and work-planning steps—we do precisely the same thing, and often we use contrasting teams, so that we do have divergent thinking. The best teams allow divergent thinking to bump them off whatever their initial biases in problem solving are. For me, design thinking gives us a constant reminder of creativity, empathy, and the tactile nature of problem solving, but it’s absolutely complementary, not alternative.

Simon London: I think, in a world of cross-functional teams, an interesting question is do people with design-thinking backgrounds really work well together with classical problem solvers? How do you make that chemistry happen?

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah, it is not easy when people have spent an enormous amount of time seeped in design thinking or user-centric design, whichever word you want to use. If the person who’s applying classic problem-solving methodology is very rigid and mechanical in the way they’re doing it, there could be an enormous amount of tension. If there’s not clarity in the role and not clarity in the process, I think having the two together can be, sometimes, problematic.

The second thing that happens often is that the artifacts the two methodologies try to gravitate toward can be different. Classic problem solving often gravitates toward a model; design thinking migrates toward a prototype. Rather than writing a big deck with all my supporting evidence, they’ll bring an example, a thing, and that feels different. Then you spend your time differently to achieve those two end products, so that’s another source of friction.

Now, I still think it can be an incredibly powerful thing to have the two—if there are the right people with the right mind-set, if there is a team that is explicit about the roles, if we’re clear about the kind of outcomes we are attempting to bring forward. There’s an enormous amount of collaborativeness and respect.

Simon London: But they have to respect each other’s methodology and be prepared to flex, maybe, a little bit, in how this process is going to work.

Hugo Sarrazin: Absolutely.

Simon London: The other area where, it strikes me, there could be a little bit of a different sort of friction is this whole concept of the day-one answer, which is what we were just talking about in classical problem solving. Now, you know that this is probably not going to be your final answer, but that’s how you begin to structure the problem. Whereas I would imagine your design thinkers—no, they’re going off to do their ethnographic research and get out into the field, potentially for a long time, before they come back with at least an initial hypothesis.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

Hugo Sarrazin: That is a great callout, and that’s another difference. Designers typically will like to soak into the situation and avoid converging too quickly. There’s optionality and exploring different options. There’s a strong belief that keeps the solution space wide enough that you can come up with more radical ideas. If there’s a large design team or many designers on the team, and you come on Friday and say, “What’s our week-one answer?” they’re going to struggle. They’re not going to be comfortable, naturally, to give that answer. It doesn’t mean they don’t have an answer; it’s just not where they are in their thinking process.

Simon London: I think we are, sadly, out of time for today. But Charles and Hugo, thank you so much.

Charles Conn: It was a pleasure to be here, Simon.

Hugo Sarrazin: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Simon London: And thanks, as always, to you, our listeners, for tuning into this episode of the McKinsey Podcast . If you want to learn more about problem solving, you can find the book, Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything , online or order it through your local bookstore. To learn more about McKinsey, you can of course find us at McKinsey.com.

Charles Conn is CEO of Oxford Sciences Innovation and an alumnus of McKinsey’s Sydney office. Hugo Sarrazin is a senior partner in the Silicon Valley office, where Simon London, a member of McKinsey Publishing, is also based.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Strategy to beat the odds

Five routes to more innovative problem solving

- Quality Improvement

- Talk To Minitab

The Basics of Structured Problem-Solving Methodologies: DMAIC & 8D

Topics: Minitab Engage

When it comes to solving a problem, organizations want to get to the root cause of the problem, as quickly as possible. They also want to ensure that they find the most effective solution to that problem, make sure the solution is implemented fully, and is sustained into the future so that the problem no longer occurs. The best way to do this is by implementing structured problem-solving. In this blog post, we’ll briefly cover structured problem-solving and the best improvement methodologies to achieve operational excellence. Before we dive into ways Minitab can help, let’s first cover the basics of problem-solving.

WHAT IS STRUCTURED PROBLEM-SOLVING?

Structured problem-solving is a disciplined approach that breaks down the problem-solving process into discrete steps with clear objectives. This method enables you to tackle complex problems, while ensuring you’re resolving the right ones. It also ensures that you fully understand those problems, you've considered the reasonable solutions, and are effectively implementing and sustaining them.

WHAT IS A STRUCTURED PROBLEM-SOLVING METHODOLOGY?

A structured problem-solving methodology is a technique that consists of a series of phases that a project must pass through before it gets completed. The goal of a methodology is to highlight the intention behind solving a particular problem and offers a strategic way to resolve it. WHAT ARE THE BEST PROBLEM-SOLVING METHODOLOGIES?

That depends on the problem you’re trying to solve for your improvement initiative. The structure and discipline of completing all the steps in each methodology is more important than the specific methodology chosen. To help you easily visualize these methodologies, we’ve created the Periodic Table of Problem-Solving Methodologies. Now let’s cover two important methodologies for successful process improvement and problem prevention: DMAIC and 8D .

8D is known as the Eight Disciplines of problem-solving. It consists of eight steps to solve difficult, recurring, or critical problems. The methodology consists of problem-solving tools to help you identify, correct, and eliminate the source of problems within your organization. If the problem you’re trying to solve is complex and needs to be resolved quickly, 8D might be the right methodology to implement for your organization. Each methodology could be supported with a project template, where its roadmap corresponds to the set of phases in that methodology. It is a best practice to complete each step of a given methodology, before moving on to the next one.

MINITAB ENGAGE, YOUR SOLUTION TO EFFECTIVE PROBLEM-SOLVING

Minitab Engage TM was built to help organizations drive innovation and improvement initiatives. What makes our solution unique is that it combines structured problem-solving methodologies with tools and dashboards to help you plan, execute, and measure your innovation initiatives! There are many problem-solving methodologies and tools to help you get started. We have the ultimate end-to-end improvement solution to help you reach innovation success.

Ready to explore structured problem-solving?

Download our free eBook to discover the top methodologies and tools to help you accelerate your innovation programs.

See how our experts can train your company to better understand and utilize data. Find out more about our Training Services today!

You Might Also Like

- Trust Center

© 2023 Minitab, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Settings

Serving technical professionals globally for over 75 years. Learn more about us.

MIT Professional Education 700 Technology Square Building NE48-200 Cambridge, MA 02139 USA

Accessibility

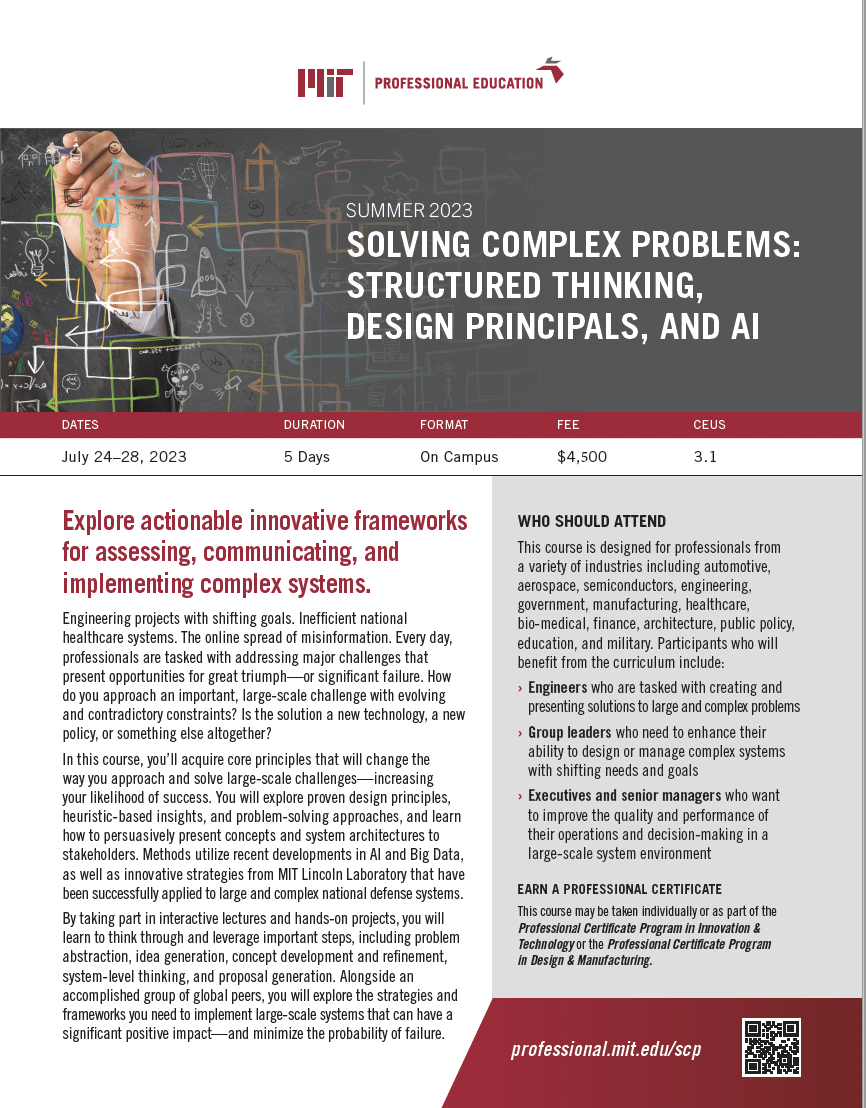

Solving Complex Problems: Structured Thinking, Design Principles, and AI

Sang-Gook Kim

Download the Course Schedule

How do you solve important, large-scale challenges with evolving and contradictory constraints? In this 5-day course, transform your approach to large-scale problem solving, from multi-stakeholder engineering projects to the online spread of misinformation. Alongside engineers and leaders from diverse industries, you’ll explore actionable innovative frameworks for assessing, communicating, and implementing complex systems—and significantly increase your likelihood of success.

THIS COURSE MAY BE TAKEN INDIVIDUALLY OR AS PART OF THE PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATE PROGRAM IN INNOVATION & TECHNOLOGY OR THE PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATE PROGRAM IN DESIGN & MANUFACTURING .

Engineering projects with shifting goals. Inefficient national healthcare systems. The online spread of misinformation. Every day, professionals are tasked with addressing major challenges that present opportunities for great triumph—or significant failure. How do you approach an important, large-scale challenge with evolving and contradictory constraints? Is the solution a new technology, a new policy, or something else altogether? In our new course Solving Complex Problems: Structured Thinking, Design Principles, and AI , you’ll acquire core principles that will change the way you approach and solve large-scale challenges—increasing your likelihood of success. Over the course of five days, you will explore proven design principles, heuristic-based insights, and problem-solving approaches, and learn how to persuasively present concepts and system architectures to stakeholders. Methods utilize recent developments in AI and Big Data, as well as innovative strategies from MIT Lincoln Laboratory that have been successfully applied to large and complex national defense systems. By taking part in interactive lectures and hands-on projects, you will learn to think through and leverage important steps, including problem abstraction, idea generation, concept development and refinement, system-level thinking, and proposal generation. Alongside an accomplished group of global peers, you will explore the strategies and frameworks you need to implement large-scale systems that can have a significant positive impact—and minimize the probability of failure.

Certificate of Completion from MIT Professional Education

- Approach and solve large and complex problems.

- Assess end-to-end processes and associated challenges, in order to significantly increase the likelihood of success in developing more complex systems.

- Implement effective problem-solving techniques, including abstracting the problem, idea generation, concept development and refinement, system-level thinking, and proposal generation.

- Utilize system-level thinking skills to evaluate, refine, down select, and evaluate best ideas and concepts.

- Apply the Axiomatic Design methodology to a broad range of applications in manufacturing, product design, software, and architecture.

- Generate and present proposals that clearly articulate innovative ideas, clarify the limits of current strategies, define potential customers and impact, and outline a success-oriented system development and risk mitigation plan.

- Effectively communicate ideas and persuade others, and provide valuable feedback.

- Confidently develop and execute large-scale system concepts that will drive significant positive impact.

Edwin F. David Head of the Engineering Division, MIT Lincoln Laboratory

Jonathan E. Gans Group Leader of the Systems and Architectures Group, MIT Lincoln Laboratory

Robert T-I. Shin Principal Staff in the Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) and Tactical Systems Division, MIT Lincoln Laboratory Director, MIT Beaver Works

This course is appropriate for professionals who design or manage complex systems with shifting needs and goals. It is also well suited to those who want to improve the quality and performance of their operations and decision-making in a large-scale system environment. Potential participants include engineers, group leaders, and senior managers in government and industries including automotive, aerospace, semiconductors, engineering, manufacturing, healthcare, bio-medical, finance, architecture, public policy, education, and military.

Computer Requirements

A laptop with PowerPoint is required.

Guide: A3 Problem Solving

Author: Daniel Croft

Daniel Croft is an experienced continuous improvement manager with a Lean Six Sigma Black Belt and a Bachelor's degree in Business Management. With more than ten years of experience applying his skills across various industries, Daniel specializes in optimizing processes and improving efficiency. His approach combines practical experience with a deep understanding of business fundamentals to drive meaningful change.

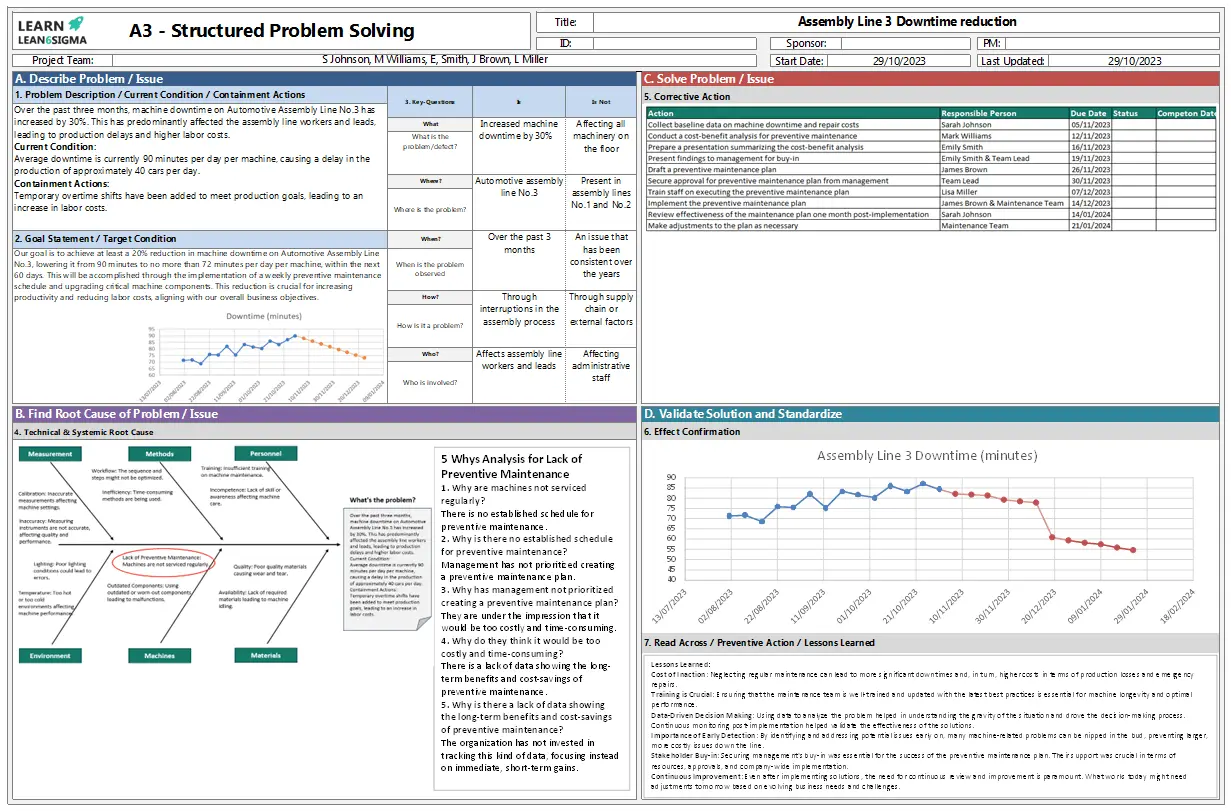

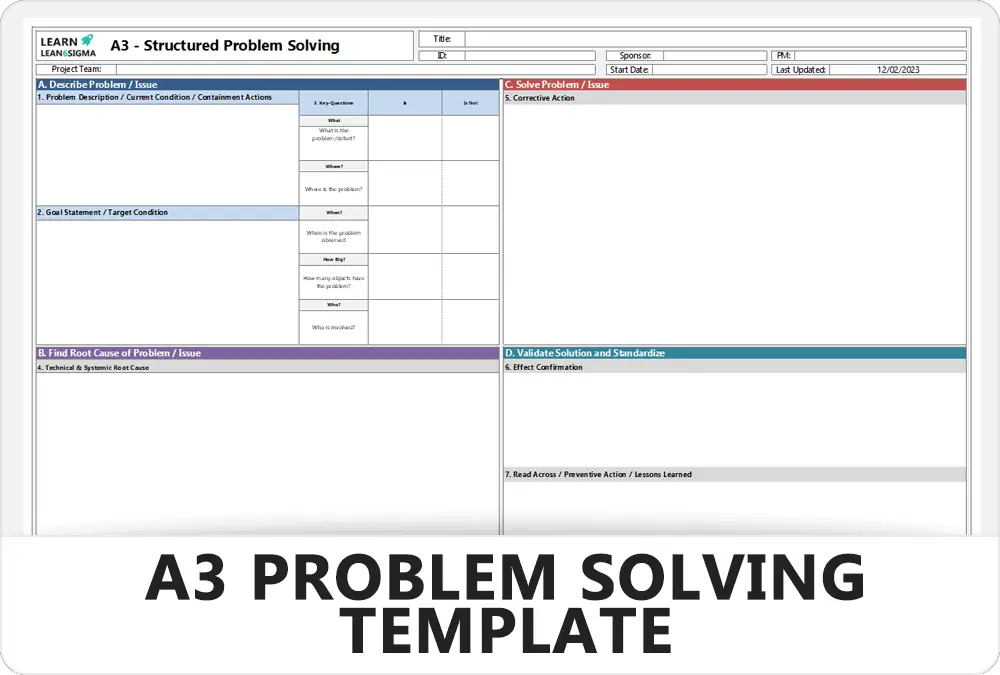

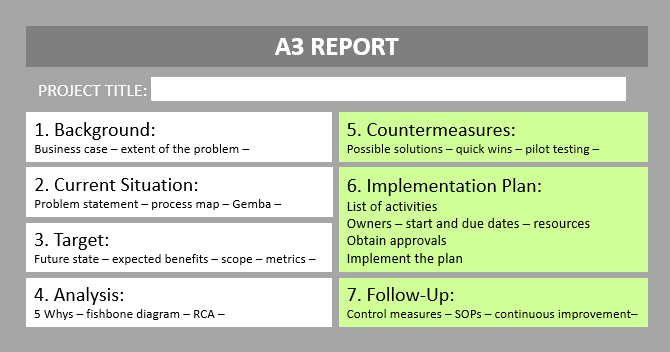

Problem-solving is one of the key tools a successful business needs to structure improvements and one I have been using to solve problems in a structured way in my career at a range of businesses over the years. When there is a problem in business that is leading to increased costs, waste , quality issues, etc., it is necessary to address these problems. A3 structured problem solving is a Lean Six Sigma methodology that has been designed and developed to support continuous improvement and solve complex business problems in a logical and structured process.

The guide will give you a full understanding of what A3 Problem solving is and a breakdown of all the steps of how to apply it within your business with an example of where I have made improvements with it previously.

Importance of A3 in Lean Management

The A3 problem-solving method is a key tool in Lean Six Sigma and continuous improvement in business, and in my experience, it is often the standard approach all improvement activities must follow and is particularly popular in the automotive industry. This is because of the following:

Focus on Root Causes : Rather than applying a quick fix to a problem or jumping to conclusions and solutionizing, A3 requires gaining a deep understanding of the root causes of the problem. By addressing these root causes, the chances of recurrence is reduced.

Standardization : With a consistent format, the A3 process ensures that problems are approached in a standardized way, regardless of the team or department. This standardization creates a common language and understanding across the organization and ensures all problems are addressed to the same standard and approach.

Team Involvement : An A3 isn’t an individual process. It requires a cross-functional team to work together on problem-solving, ensuring that a range of perspectives and expertise is considered. This collective approach builds a stronger understanding of the problem and ensures that solutions are well-rounded and robust.

Visual Storytelling : The A3 report serves as a visual storyboard, making it easier for stakeholders at all levels to understand the problem, the analysis, and the countermeasures. This visualization enhances communication and drives alignment.

The 6 Steps of A3 Problem Solving (With Real Example)

The A3 problem-solving process can initially seem difficult if you have never done one before and particularly if you have never been a team member in one. To help you with this we will break down the 6 steps into manageable activities, followed by a real-life example to help you apply this method within your business.

As a side note, the A3 problem-solving process was actually one of the first Lean Six Sigma tools I learned to use three weeks into my continuous improvement career after being thrown into the deep end due to resource availability, so I can understand how difficult it can be to understand.

Step 1: Describe the problem

Problem description.

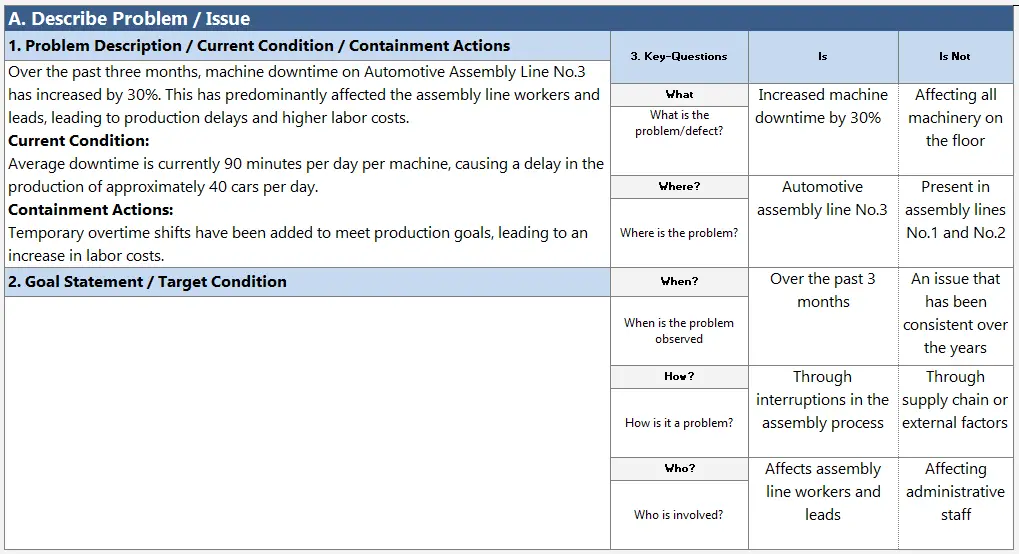

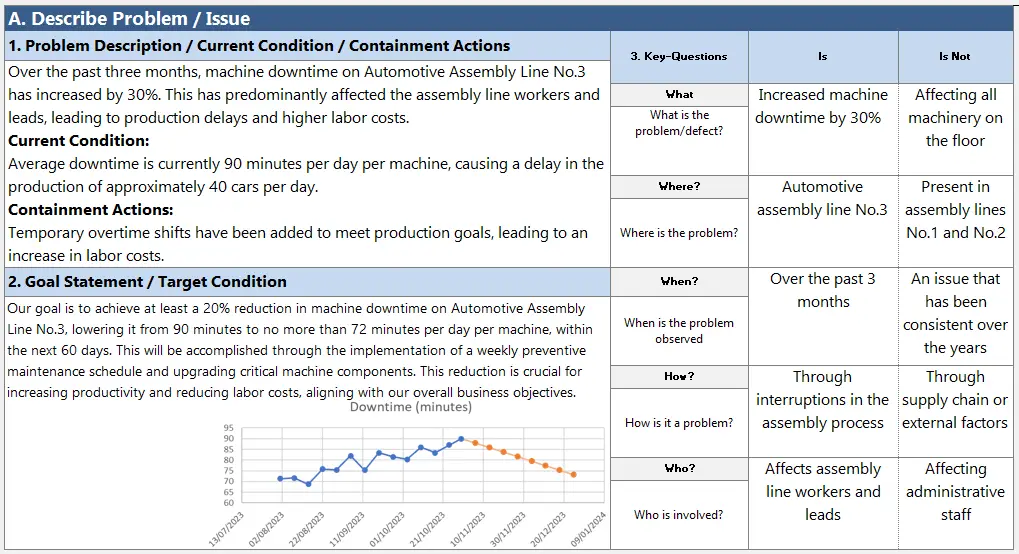

The problem description is an important first step in the process as it ensures a common understanding with the team of what the issue is that needs to be addressed. This can be done by using a technique called the 5W1H Is/Is Not method to help gain a clear understanding of the problem.

To understand the 5W1H Is/Is Not the Process, check out our guide for details of that technique. However, in short, it’s about asking key questions about the problem, for example, “What IS the problem?” and “What IS NOT the problem?”

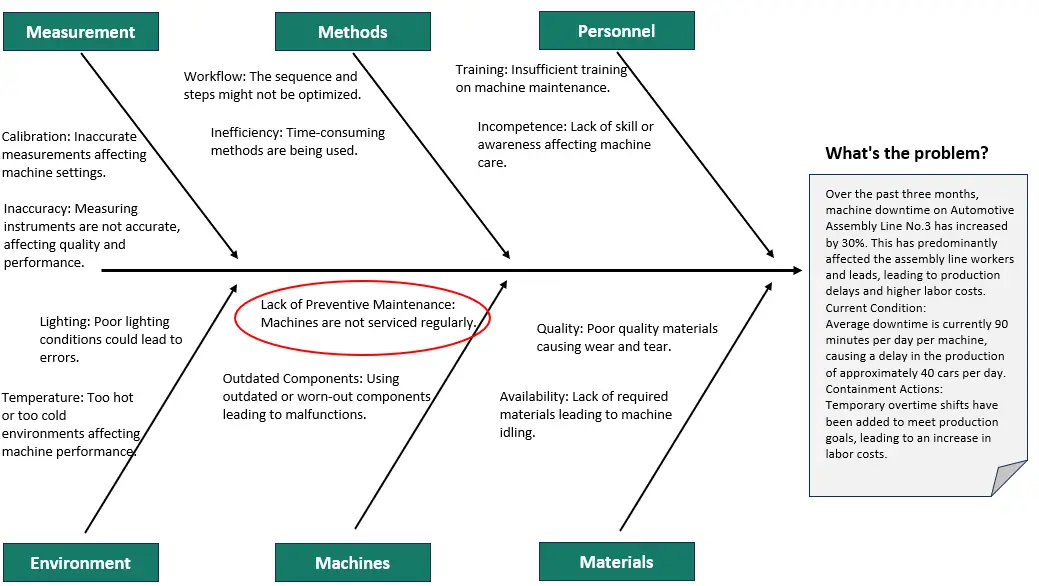

Let’s say you have been asked to look into a problem where “Machine downtime on the automotive assembly line has increased by 30% over the past three months, leading to production delays and increased costs.”

An example of a 5W1H Is/Is Not on this may result in the following output:

| 5W1H | Is | Is Not |

|---|---|---|

| Who | Affects assembly line workers and leads | Affecting administrative staff |

| What | Increased machine downtime by 30% | This affects all machinery on the floor |

| When | Over the past 3 months | An issue that has been consistent over the years |

| Where | Automotive assembly line No.3 | Present in assembly lines No.1 and No.2 |

| Why | Lack of preventive maintenance and outdated components | Due to manual errors by operators |

| How | Through interruptions in the assembly process | Through supply chain or external factors |

Based on this we can create a clear problem description as the focus of the project that give the team a clear and common understanding of the issue looking to be resolved in the next steps of the process. The problem description could then be written as:

“Over the past three months, machine downtime on Automotive Assembly Line No.3 has increased by 30%. This has predominantly affected the assembly line workers and leads, leading to production delays and higher labour costs. “

Current Condition

Next is demonstrating the current condition and demonstrating the impact on the business. This can often be done with data and charts to back up the problem that might show trends or changes in outputs.

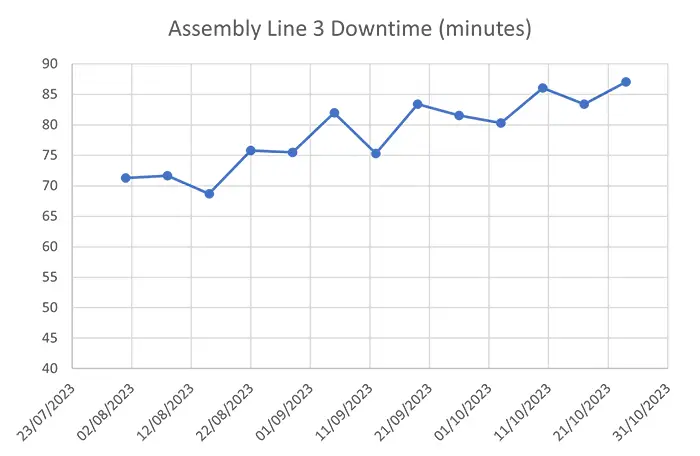

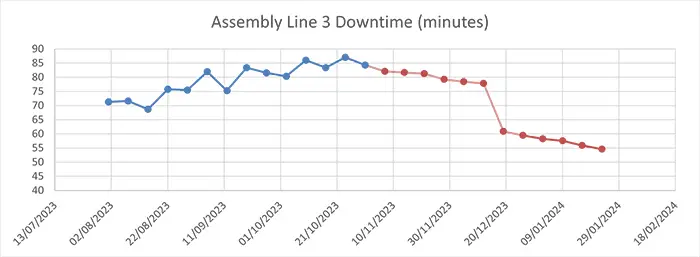

This might look something like the below and demonstrate a good baseline for confirming the improvement at the end of the A3

Containment Actions

Next is containment actions. Since you have identified a problem, there is likely an impact on the business or the customer. As a team, you should consider what can be done to limit or eliminate this problem in the short term. Remember this is just a containment action and should not be seen as a long-term fix.

In our situation we decided to “Implement temporary overtime shifts to meet production goals, leading to an increase in labor costs.”

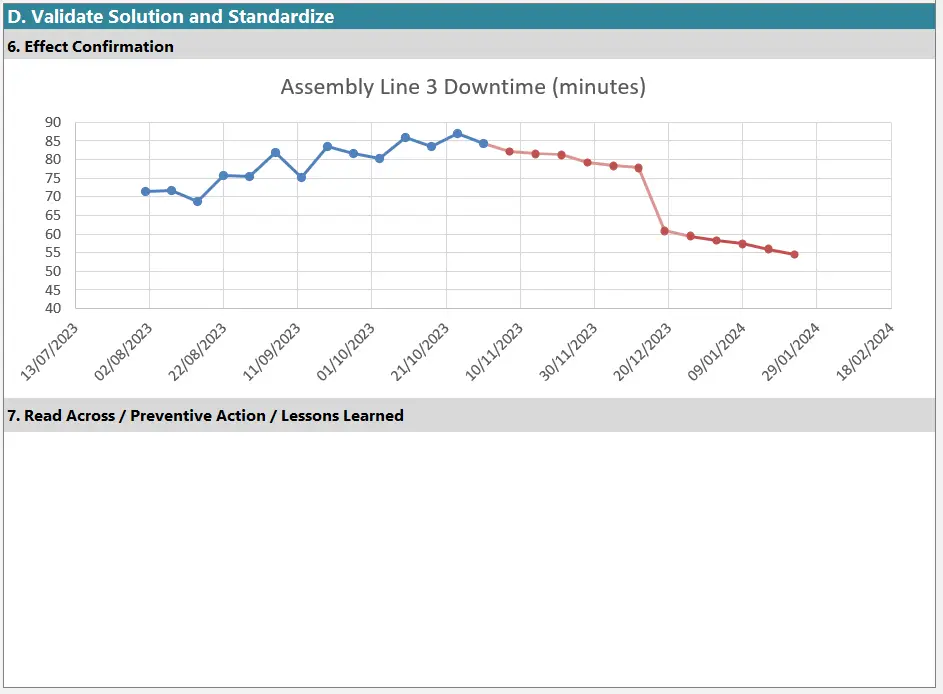

At this stage, the A3 should look similar to the one below; you can use charts and graphics to represent the current state as well if they fit within the limit area. Remember, we must include the content of the A3 within the 1-page A3 Document.

Step 2: Set the A3 Goals

The next step of the A3 is to, as a team, set the goal for the project. As we have a clear understanding of the current condition of the problem, we can use that as our baseline for improvement and set a realistic target for improvement.

A suggested method for setting the Target condition would be to use the SMART Target method.

If you are not familiar with SMART Targets , read our guide; it will cover the topic in much more detail. In short, a SMART target creates a goal statement that is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

By doing this you make it very clear what the goal of the project is, how it will be measured, it is something that can be achieved, relevant to the needs of the business and has a deadline for when results need to be seen.

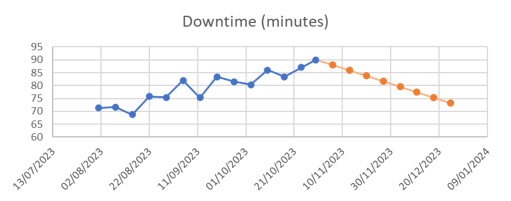

For our A3 we decided that the goal would be “Our goal is to achieve at least a 20% reduction in machine downtime on Automotive Assembly Line No.3, lowering it from 90 minutes to no more than 72 minutes per day per machine, within the next 60 days. This reduction is crucial for increasing productivity and reducing labour costs, aligning with our overall business objectives.”

I also recommend using charts in this section to visualize the benefit or improvement to ensure you have stakeholder and sponsor support. Visuals are much easier and faster for people to understand.

At this point, your A3 might look something like the one below, with the first 1/4 or section complete. The next step is to move on to the root cause analysis to get to the root of the problem and ensure the improvement does not focus on addressing the symptoms of the problem.

Step 3: Root Cause Analysis

Root cause analysis is the next step in the process, often referred to as gap analysis, as this step focuses on how to get to the goal condition from the current condition.

Tip: If at this point you find the team going off-topic and focusing on other issues, Ask the question, “Is this preventing us from hitting our goal statement?” I have found this very useful for keeping on track in my time as an A3 facilitator.

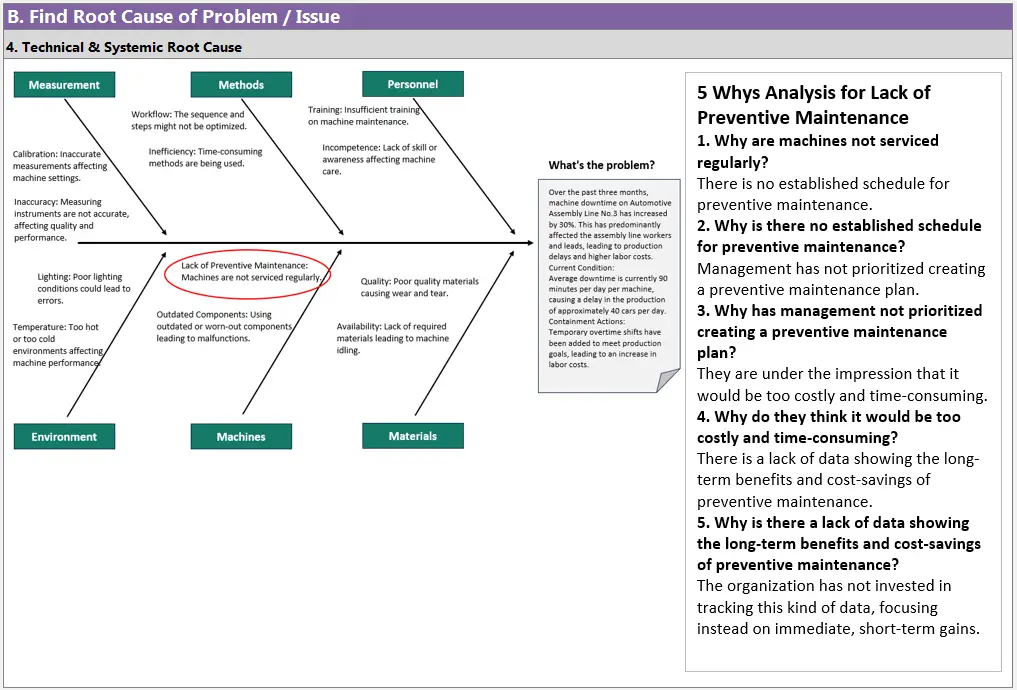

For root cause analysis, a couple of key tools are usually used: a fishbone diagram and a five-why Analysis . Again, we won’t go into the full details of these tools within this guide, as they have been covered in extensive detail in their own guides.

But the aim at this point is as a team, to brainstorm what is preventing us from achieving our target condition. This is done by allowing all members of the team to input the reasons they think it is not being achieved. These inputs are often written on sticky notes and placed on the fishbone diagram. Following this, you may have results similar to the ones below. Note: it is important that the inputs are specific so they can be understood. e.g. “Calibration” alone is not specific to how it’s causing the problem; specify it with “Calibration: Inaccurate measurements affecting machine settings.”

After the fishbone diagram has been populated and the team has exhausted all ideas, the team should then vote on the most likely cause to explore with a 5 Whys analysis. This is done because, due to resource limitations, it is unlikely all of the suggestions can be explored and actioned.

In this situation the team decided the “lack of preventative machines: machines not being serviced regularly” was the cause of increased downtime. This was explored with the 5 Whys to get to the root cause of why Assembly Line 3 did not have preventative maintenance implemented.

The result of this root cause analysis can be seen below, and you may end up with more ideas on the fishbone, as generally there are a lot of ideas generated by a diverse team during brainstorming.

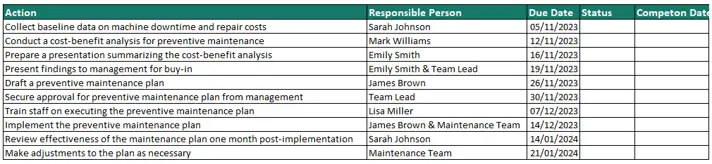

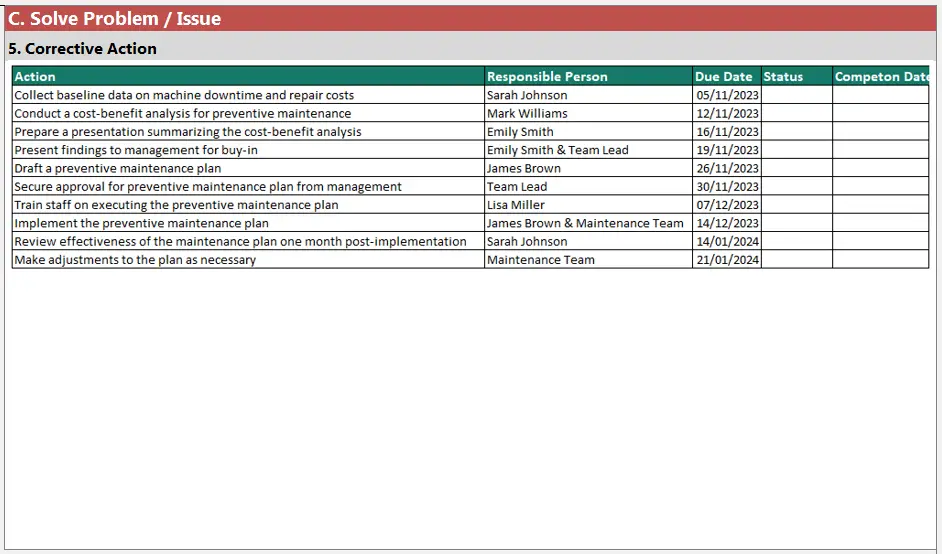

Step 4: Solutions and Corrective Actions

Now that we understand what the root cause of the problem is, we need to address it with solutions and corrective actions. Again, as a team, consider the root cause of the problem and discuss what actions need to be taken by the team, who will do them, and when they will be done. The result should be an action plan, for example, like the one below:

This action plan needs to be carried out and implemented.

The result of this section will likely just be an action list and look like the below section.

Step 5: Validate Solution and Standardize

Within step 5 it is time to collect data to validate and confirm the actions that have been implemented resulting in solving the problem and meeting the target state of the problem. This is done by continuing to collect data that demonstrates the problem in the baseline to see if the problem is being reduced.

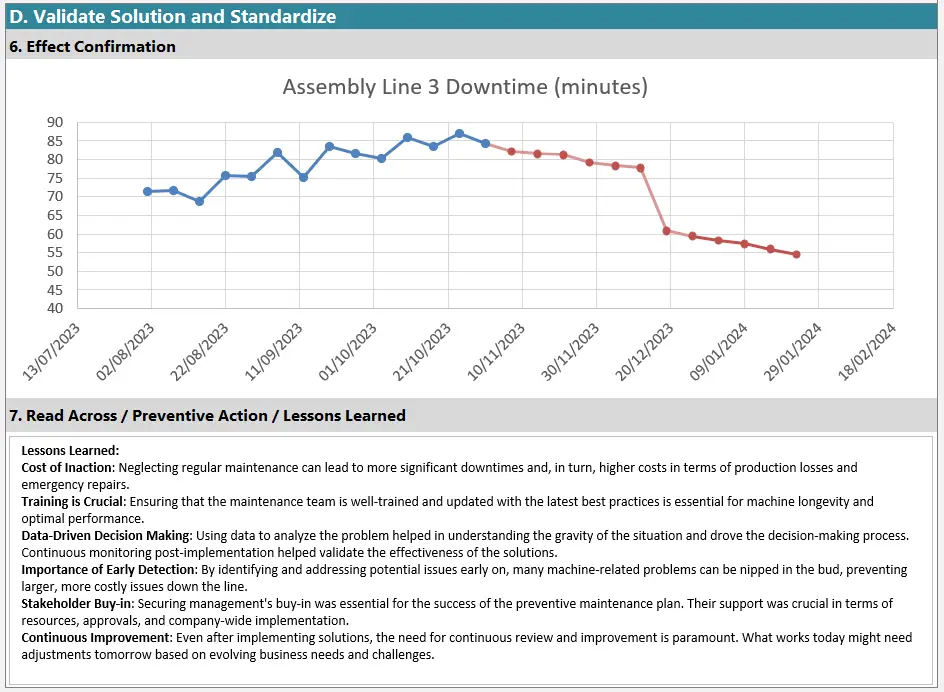

For example, below, the project team continued to collect Assembly Line 3 downtime data on a weekly basis. Initially, there was a steady reduction, likely due to the focus of the project on the problem, which had some impact. However, once the majority of the action was implemented, a huge drop in product downtime was seen, exceeding the target. This showed the actions have been successful

If, in the validation stage, you find that the improvement required is not being made, you should go back to step 3 and reconsider the root cause analysis with the team, pick another area to focus on, and create an action plan for that following the same steps.

Step 6: Preventive Actions and Lessons Learned

In step 6 after the confirmation of project success you should look at preventive actions and lessons learned to be shared from this project:

- Preventive Action: The new preventive maintenance schedule will be standardized across all assembly lines. This will prevent other lines having similar issues and make further improvements

- Lessons Learned: A formal review will be conducted to document the process, including challenges faced and how they were overcome, which will then be archived for future reference.

In our project, this looked like the one below and will be used as a reference point in the future for similar issues.

And that is the successful completion of a structured A3 problem-solving technique.

The complete A3 looks like the below image. Yours may slightly differ as the problem and information vary between projects.

Downloadable A3 Reporting Template

To support you with your A3 problem solving, you can download our free A3 problem solving report from the template section of the website.

Problem-solving is important in businesses, specifically when faced with increased costs or quality issues. A3 Structured Problem Solving, rooted in Lean Six Sigma, addresses complex business challenges systematically.

Originally from Toyota’s lean methodology, A3, named after the 11″x17″ paper size, visually maps problem-solving processes. This method ensures concise communication and focuses on crucial details, as illustrated by the provided example.

Emphasized in Lean Management, A3 stresses understanding root causes, standardization across teams, team collaboration, and visual representation for clarity. This tool is not only a guide to understanding the issue but is a standardized format ensuring robust solutions. Particularly for novices, breaking down its six steps, from problem description to setting A3 goals and root cause analysis, provides clarity. Visual aids further enhance comprehension and alignment across stakeholders.

- Sobek II, D.K. and Jimmerson, C., 2004. A3 reports: tool for process improvement. In IIE Annual Conference. Proceedings (p. 1). Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers (IISE).

- Matthews, D.D., 2018. The A3 workbook: unlock your problem-solving mind . CRC Press.

Q: What is A3 problem solving?

A: A3 problem solving is a structured approach used to tackle complex problems and find effective solutions. It gets its name from the A3-sized paper that is typically used to document the problem-solving process.

Q: What are the key benefits of using A3 problem solving?

A: A3 problem solving provides several benefits, including improved communication, enhanced teamwork, better problem understanding, increased problem-solving effectiveness, and the development of a culture of continuous improvement.

Q: How does A3 problem solving differ from other problem-solving methods?

A: A3 problem solving emphasizes a systematic and structured approach, focusing on problem understanding, root cause analysis, and the development and implementation of countermeasures. It promotes a holistic view of the problem and encourages collaboration and learning throughout the process.

Q: What are the main steps in the A3 problem-solving process?

A: The A3 problem-solving process typically involves the following steps: problem identification and description, current condition analysis, goal setting, root cause analysis, countermeasure development, implementation planning, action plan execution, and follow-up and evaluation.

Q: What is the purpose of the problem identification and description step?

A: The problem identification and description step is crucial for clarifying the problem, its impact, and the desired outcome. It helps establish a common understanding among the team members and ensures everyone is working towards the same goal.

Daniel Croft

Hi im Daniel continuous improvement manager with a Black Belt in Lean Six Sigma and over 10 years of real-world experience across a range sectors, I have a passion for optimizing processes and creating a culture of efficiency. I wanted to create Learn Lean Siigma to be a platform dedicated to Lean Six Sigma and process improvement insights and provide all the guides, tools, techniques and templates I looked for in one place as someone new to the world of Lean Six Sigma and Continuous improvement.

Free Lean Six Sigma Templates

Improve your Lean Six Sigma projects with our free templates. They're designed to make implementation and management easier, helping you achieve better results.

Was this helpful?

Continuous Improvement Toolkit

Effective Tools for Business and Life!

A3 Thinking: A Structured Approach to Problem Solving

- 5 MINUTES READ

Also known as A3 Problem Solving.

Variants include 8D and CAPA.

A significant part of a leader’s role involves addressing problems as they arise. Various approaches and tools are available to facilitate problem-solving which is the driving force behind continuous improvement. These methods range from the advanced and more complex methodologies like Six Sigma to the simpler and more straightforward A3 thinking approach.

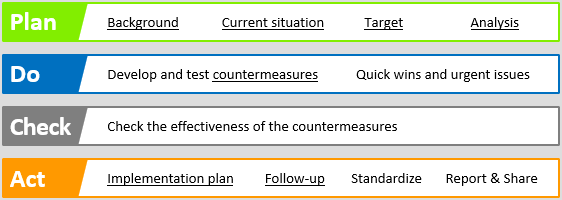

The power of the A3 approach lies in its systematic and structured approach to problem-solving. Although it appears to be a step-by-step process, A3 is built around the PDCA philosophy. It relies on the principle that it is much better to address the real root-cause rather than trying to find a solution. Hence, it’s important not to jump to the solution when solving a problem as it is likely to be less effective.

A3 thinking provides an effective way to bring together many of the problem-solving tools into one place. For example, techniques such as the 5 Whys and fishbone analysis can be used during the ‘Analysis’ stage to help identifying the root causes. Additionally, visual aids and graphs are highly recommended in the A3 report, as they are more effective than text in communicating ideas and providing concise project updates.

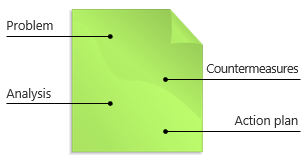

A3 thinking involves the practice of consolidating the problem, analysis, countermeasures, and action plan onto a single sheet of paper, commonly an A3-sized sheet. This brief document serves as a summary of the project at hand and is regarded as a valuable storytelling tool for project communication. Utilizing the A3 approach doesn’t require any specialized software or advanced computer skills. You may however use readily available A3 templates , or rely on basic tools such as paper, pencil and an eraser as you will need to erase and rewrite several times.

One of the characteristics of the A3 approach is that it does not get into specific details. Detailed documents are usually attached to the A3 report to prevent overwhelming the reader with an excess of information.

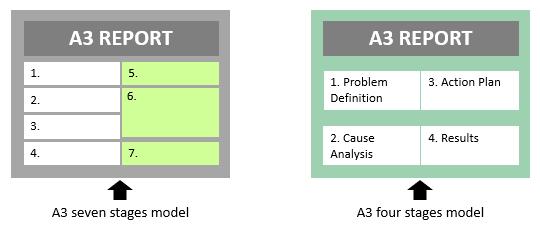

The A3 process is typically structured in multiple stages based on the PDCA model. The primary focus is on developing understanding of the current situation and defining the desired outcome before thinking about the solution. While the exact number of stages may vary depending on the preference of the company, what truly matters is adhering to a structured approach to problem-solving.

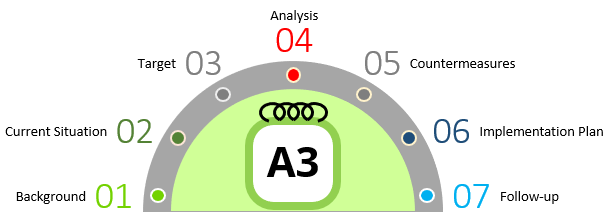

A3 Seven Stages Model

An A3 process is often managed by an individual who should own and maintain the A3 report. This individual takes the lead in steering the process, facilitating team involvement, and preparing the A3 report with team input. One of the most common models for A3 thinking is the seven stages model which is described in the following.

1. Background – The first step is to identify the business reason for choosing this problem or opportunity. In this stage, you need to identify the gap in performance and the extent of the problem.

2. Current situation – The purpose of this stage is to document the current state of the problem. You may need to refer to the process map or go to the Gemba to truly understand the current situation.

3. Target – The purpose of this stage is to define the desired future state. Clearly identify the expected benefits from solving the problem, the scope, and the key metrics that will help measure the success of the project.

4. Analysis – The objective of this stage is to conduct an in-depth analysis of the problem and understand why it’s happening. It might involve tools like the 5 Whys and cause-and-effect analysis, as well as advanced statistical methods.

5. Countermeasures – Countermeasures are the actions to be taken to eliminate root causes or reduce their effects. The team should brainstorm and evaluate possible countermeasures based on the analysis conducted earlier.

6. Implementation Plan – To achieve the target, develop a workable plan to implement the countermeasures. Gantt charts are great ways to manage implementation plans very simply and easily. Once the action plan is finalized, the team should begin working on the activities needed to implement the countermeasures.

7. Follow-up – The final stage involves evaluating the implementation of the plan and the results achieved. Follow-up actions are important to ensure the benefits extend beyond the project’s completion.

A3 thinking is considered to be the practical form of the PDCA model.

There are many online templates that can be used to manage your problem-solving efforts. One of the simplest and most straightforward ways is to use this A3 problem solving template .

Wrapping Up

A3 thinking represents a logical and structured approach for problem solving and continuous improvement. This approach can be used for most kinds of problems and in any part of the business. Originating from the Toyota Production System (TPS), it has been adopted by many Lean organizations around the world.

A3 thinking not only provides a systematic approach for problem-solving. The development of a continuous improvement culture is at the core of A3 thinking. It has become one of the most popular Lean tools today where people and teams work together to solve problems, share results and learn from each other.

Other Formats

Do you want to use the slides in your training courses?

A3 Thinking Training Material – $18.85

Related Articles

Project Charter

Gantt Chart

Related Templates

A3 Problem Solving

Written by:

CIToolkit Content Team

Critical Thinking and Structured Problem Solving

Effective critical thinking and problem-solving skills are indispensable for professionals who strive to help their organizations make well-informed business decisions rooted in robust evidence. While the complexity of problems may vary, a structured approach can be applied to nearly all situations, bolstering the prospects of long-term organizational success. In this intensive course, participants will learn about various analytical thinking techniques that can mitigate the influence of cognitive biases in decision-making.

Course Methodology

This course structure emphasizes a hands-on, practical approach to learning critical thinking and problem-solving skills, with activities designed to be directly applicable in a professional context.

Course Objectives

By the end of the course, participants will be able to:

- Apply critical thinking models to understand problems accurately and develop reasoned arguments

- Evaluate and synthesize information to devise innovative solutions to complex problems

- Implement developed solutions into organizational processes and measure their impact

Target Audience

This course is suitable for analysts, professionals, managers, and leaders at all levels within the organization.

Target Competencies

- Critical thinking

- Problem solving

- Solution implementation

- Results based decision-making

- Understanding how we think and reason

- Confirmation bias

- Critical thinking principles

- Models and frameworks for critical analysis

- Defining the right issue

- Structuring complex problems

- Using logic trees in problem solving

- Data gathering and synthesis

- Evaluating solutions

- Feasibility analysis

- Translating outcomes into actionable plans

- Monitoring and measuring implementation outcomes

2024 Schedule & Fees

Per participant.

Fees + VAT as applicable

(including coffee breaks and a buffet lunch daily)

Location & Date

There are no public sessions remaining for the course this year. Please contact us if you wish to have a customized in-house session, or to find out how an additional public session can be scheduled.

Meirc reserves the right to alter dates, content, venue, trainer, and to offer courses in an integrated virtual learning (IVL) format whereby face to face classroom participants and virtual learners participate simultaneously in the same course in an interactive learning experience.

Tax Registration Number: 100239834300003

Course Outline

Schedule & fees.

Search Here

Call me back.

Give us your details and we’ll call you!

Quick Enquiry

Download brochure.

- 1st Floor, Building 13, Bay Square, Business Bay

- PO Box 5883, Dubai, UAE

- +971 4 556 7171 | 800 7100

- [email protected]

- Offices 901 & 902, Sultan International Tower, Corniche Road

- PO Box 62182, Abu Dhabi, UAE

- +971 2 491 0700 | 800 7100

UAE Tax Registration Number

100239834300003

- Al Awad Building, RUQA 7523 (DMS), Said bin Zaid Street, Qurtubah

- PO Box 220460, Riyadh 11311, KSA

- +966 11 451 7017 | 9200 13917

- Office 206, Sultana Square, Prince Sultan Road

- PO Box 1394, Jeddah 21414, KSA

KSA Tax Registration Number

311655469100003

Other Links

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Course Selector

© 2024 Meirc Training & Consulting. All rights reserved.

McKinsey Problem Solving: Six steps to solve any problem and tell a persuasive story

The McKinsey problem solving process is a series of mindset shifts and structured approaches to thinking about and solving challenging problems. It is a useful approach for anyone working in the knowledge and information economy and needs to communicate ideas to other people.

Over the past several years of creating StrategyU, advising an undergraduates consulting group and running workshops for clients, I have found over and over again that the principles taught on this site and in this guide are a powerful way to improve the type of work and communication you do in a business setting.

When I first set out to teach these skills to the undergraduate consulting group at my alma mater, I was still working at BCG. I was spending my day building compelling presentations, yet was at a loss for how to teach these principles to the students I would talk with at night.

Through many rounds of iteration, I was able to land on a structured process and way of framing some of these principles such that people could immediately apply them to their work.

While the “official” McKinsey problem solving process is seven steps, I have outline my own spin on things – from experience at McKinsey and Boston Consulting Group. Here are six steps that will help you solve problems like a McKinsey Consultant:

Step #1: School is over, stop worrying about “what” to make and worry about the process, or the “how”

When I reflect back on my first role at McKinsey, I realize that my biggest challenge was unlearning everything I had learned over the previous 23 years. Throughout school you are asked to do specific things. For example, you are asked to write a 5 page paper on Benjamin Franklin — double spaced, 12 font and answering two or three specific questions.

In school, to be successful you follow these rules as close as you can. However, in consulting there are no rules on the “what.” Typically the problem you are asked to solve is ambiguous and complex — exactly why they hire you. In consulting, you are taught the rules around the “how” and have to then fill in the what.

The “how” can be taught and this entire site is founded on that belief. Here are some principles to get started:

Step #2: Thinking like a consultant requires a mindset shift

There are two pre-requisites to thinking like a consultant. Without these two traits you will struggle:

- A healthy obsession looking for a “better way” to do things

- Being open minded to shifting ideas and other approaches

In business school, I was sitting in one class when I noticed that all my classmates were doing the same thing — everyone was coming up with reasons why something should should not be done.

As I’ve spent more time working, I’ve realized this is a common phenomenon. The more you learn, the easier it becomes to come up with reasons to support the current state of affairs — likely driven by the status quo bias — an emotional state that favors not changing things. Even the best consultants will experience this emotion, but they are good at identifying it and pushing forward.

Key point : Creating an effective and persuasive consulting like presentation requires a comfort with uncertainty combined with a slightly delusional belief that you can figure anything out.

Step #3: Define the problem and make sure you are not solving a symptom

Before doing the work, time should be spent on defining the actual problem. Too often, people are solutions focused when they think about fixing something. Let’s say a company is struggling with profitability. Someone might define the problem as “we do not have enough growth.” This is jumping ahead to solutions — the goal may be to drive more growth, but this is not the actual issue. It is a symptom of a deeper problem.

Consider the following information:

- Costs have remained relatively constant and are actually below industry average so revenue must be the issue

- Revenue has been increasing, but at a slowing rate

- This company sells widgets and have had no slowdown on the number of units it has sold over the last five years

- However, the price per widget is actually below where it was five years ago

- There have been new entrants in the market in the last three years that have been backed by Venture Capital money and are aggressively pricing their products below costs

In a real-life project there will definitely be much more information and a team may take a full week coming up with a problem statement . Given the information above, we may come up with the following problem statement:

Problem Statement : The company is struggling to increase profitability due to decreasing prices driven by new entrants in the market. The company does not have a clear strategy to respond to the price pressure from competitors and lacks an overall product strategy to compete in this market.

Step 4: Dive in, make hypotheses and try to figure out how to “solve” the problem

Now the fun starts!

There are generally two approaches to thinking about information in a structured way and going back and forth between the two modes is what the consulting process is founded on.

First is top-down . This is what you should start with, especially for a newer “consultant.” This involves taking the problem statement and structuring an approach. This means developing multiple hypotheses — key questions you can either prove or disprove.

Given our problem statement, you may develop the following three hypotheses:

- Company X has room to improve its pricing strategy to increase profitability

- Company X can explore new market opportunities unlocked by new entrants

- Company X can explore new business models or operating models due to advances in technology

As you can see, these three statements identify different areas you can research and either prove or disprove. In a consulting team, you may have a “workstream leader” for each statement.

Once you establish the structure you you may shift to the second type of analysis: a bottom-up approach . This involves doing deep research around your problem statement, testing your hypotheses, running different analysis and continuing to ask more questions. As you do the analysis, you will begin to see different patterns that may unlock new questions, change your thinking or even confirm your existing hypotheses. You may need to tweak your hypotheses and structure as you learn new information.

A project vacillates many times between these two approaches. Here is a hypothetical timeline of a project:

Step 5: Make a slides like a consultant

The next step is taking the structure and research and turning it into a slide. When people see slides from McKinsey and BCG, they see something that is compelling and unique, but don’t really understand all the work that goes into those slides. Both companies have a healthy obsession (maybe not to some people!) with how things look, how things are structured and how they are presented.

They also don’t understand how much work is spent on telling a compelling “story.” The biggest mistake people make in the business world is mistaking showing a lot of information versus telling a compelling story. This is an easy mistake to make — especially if you are the one that did hours of analysis. It may seem important, but when it comes down to making a slide and a presentation, you end up deleting more information rather than adding. You really need to remember the following:

Data matters, but stories change hearts and minds

Here are four quick ways to improve your presentations:

Tip #1 — Format, format, format

Both McKinsey and BCG had style templates that were obsessively followed. Some key rules I like to follow:

- Make sure all text within your slide body is the same font size (harder than you would think)

- Do not go outside of the margins into the white space on the side

- All titles throughout the presentation should be 2 lines or less and stay the same font size

- Each slide should typically only make one strong point

Tip #2 — Titles are the takeaway

The title of the slide should be the key insight or takeaway and the slide area should prove the point. The below slide is an oversimplification of this:

Even in consulting, I found that people struggled with simplifying a message to one key theme per slide. If something is going to be presented live, the simpler the better. In reality, you are often giving someone presentations that they will read in depth and more information may make sense.

To go deeper, check out these 20 presentation and powerpoint tips .

Tip #3 — Have “MECE” Ideas for max persuasion

“MECE” means mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive — meaning all points listed cover the entire range of ideas while also being unique and differentiated from each other.

An extreme example would be this:

- Slide title: There are seven continents

- Slide content: The seven continents are North America, South America, Europe, Africa Asia, Antarctica, Australia

The list of continents provides seven distinct points that when taken together are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive . The MECE principle is not perfect — it is more of an ideal to push your logic in the right direction. Use it to continually improve and refine your story.

Applying this to a profitability problem at the highest level would look like this:

Goal: Increase profitability

2nd level: We can increase revenue or decrease costs

3rd level: We can increase revenue by selling more or increasing prices

Each level is MECE. It is almost impossible to argue against any of this (unless you are willing to commit accounting fraud!).

Tip #4 — Leveraging the Pyramid Principle

The pyramid principle is an approach popularized by Barbara Minto and essential to the structured problem solving approach I learned at McKinsey. Learning this approach has changed the way I look at any presentation since.

Here is a rough outline of how you can think about the pyramid principle as a way to structure a presentation:

As you build a presentation, you may have three sections for each hypothesis. As you think about the overall story, the three hypothesis (and the supporting evidence) will build on each other as a “story” to answer the defined problem. There are two ways to think about doing this — using inductive or deductive reasoning:

If we go back to our profitability example from above, you would say that increasing profitability was the core issue we developed. Lets assume that through research we found that our three hypotheses were true. Given this, you may start to build a high level presentation around the following three points:

These three ideas not only are distinct but they also build on each other. Combined, they tell a story of what the company should do and how they should react. Each of these three “points” may be a separate section in the presentation followed by several pages of detailed analysis. There may also be a shorter executive summary version of 5–10 pages that gives the high level story without as much data and analysis.

Step 6: The only way to improve is to get feedback and continue to practice

Ultimately, this process is not something you will master overnight. I’ve been consulting, either working for a firm or on my own for more than 10 years and am still looking for ways to make better presentations, become more persuasive and get feedback on individual slides.

The process never ends.

The best way to improve fast is to be working on a great team . Look for people around you that do this well and ask them for feedback. The more feedback, the more iterations and more presentations you make, the better you will become. Good luck!

If you enjoyed this post, you’ll get a kick out of all the free lessons I’ve shared that go a bit deeper. Check them out here .

Do you have a toolkit for business problem solving? I created Think Like a Strategy Consultant as an online course to make the tools of strategy consultants accessible to driven professionals, executives, and consultants. This course teaches you how to synthesize information into compelling insights, structure your information in ways that help you solve problems, and develop presentations that resonate at the C-Level. Click here to learn more or if you are interested in getting started now, enroll in the self-paced version ($497) or hands-on coaching version ($997). Both versions include lifetime access and all future updates.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Get the Free Mini-Course

Learn to solve complex problems, write compellingly, and upgrade your thinking with our free mini-course.

Work With Us

Join 1,000+ professionals and students learning consulting skills and accelerating their careers

The Lean Post / Articles / How to A3: Resources for Developing Structured Problem-Solving and Leadership Skills

Problem Solving

How to A3: Resources for Developing Structured Problem-Solving and Leadership Skills

June 18, 2020

As LEI prepares its next course on Managing to Learn, here's a popular article rounding up a wealth of resources about practicing A3 Thinking by Tom Ehrenfeld

A3 reports have become one of the most popular lean tools today, a way for people and teams to work together to solve problems; and their widespread adoption could easily be viewed in lean terms as…a problem.

Tools often provide traction for getting started with lean practice, and A3s often deliver immediate results. The A3 ‘problem’ (a gap, in this case, between the intended purpose and actual usage) echoes the broader challenge facing widespread adoption of any proven TPS methodology: moving from lean tools to lean management , according to Jim Womack. As he notes, “Tools—for process analysis and for management—are wonderful things. And they are absolutely necessary. And managers love them because they seem to provide shortcuts to doing a better job. But they can’t achieve their potential results, and often can’t achieve any results, without managers with a lean state of mind to wield them.”

Let’s keep in mind the purpose of A3s, from the Introduction to John Shook’s key book on the topic, Managing to Learn ( MtL ).

“Writing an A3 is the first step toward learning to use the A3 process, toward learning to learn. Some benefits in improved problem-solving, decision-making, and communications ability can be expected when individual A3 authors adopt this approach.”

All well and good. Unfortunately most organizations stop there, and don’t proceed to the next step. As Shook cautions, “unless the broader organization embraces the broader process, the much greater benefit will be unrealized. The entire effort may degenerate into a ‘check-the-box’ exercise, as A3s will join unused SPC charts, ignored standardized work forms, and disregarded value-stream maps as corporate wallpaper.”

So what exactly are A3 reports? A3 reports are a way of structuring and sharing knowledge that enables teams and their members to practice scientific thinking as a way of discovering and learning together. The tool promises immediate benefits by helping people structure and design more effective approaches to problems (framing them in solvable ways, taking a data-based approach, using root-cause-analysis to find the point of origin for problems (gaps), encouraging careful problem analysis over quick abstract “solutions,” and so forth).

Definitions include:

- A storyboard

- 5S for information

- Standardized story-telling

- A “visual manifestation of a problem-solving thought process involving continual dialogue between the owner of an issue and others in an organization.”

They are all that, and more. Essentially, A3 reports, named for the international-sized A3 paper (a larger page of roughly 11 by 17 inches), enable people in organizations to capture issues through a commonly understood template, permitting people to see problems through the same lens. The sequence is designed along the logic of scientific thinking—the PDCA cycle at the heart of lean thinking. You can download A3 templates from LEI here .

The basic thinking process captured by this format is relatively simple, and has been around in many other forms and formats for a long time. There are different types of A3s , according to the situation. But don’t work too hard to find the precisely right format; in fact, veterans such as David Verble stress the importance of starting your A3 not by writing but by thinking .

“The most fundamental use of the A3 is as a simple problem-solving tool. But the underlying principles and practices can be applied in any organizational setting. Given that the first use of the A3 as a tool is to standardize a methodology to understand and respond to problems, A3s encourage root cause analysis, reveal processes, and represent goals and actions in a format that triggers conversation and learning,” says John Shook in this piece sharing his purpose for writing MtL .

There’s no doubt that those with deep experience have found great power in A3 practice. For example, lean veteran Gary Convis says that he, “used the A3 format as a way of seeing inside the minds of the 113 plant managers,” citing his experience at Dana Holdings Corp , as well as elaborating on using A3 problem solving to make the thinking process visible .

Toyota veteran Tracey Richardson shares a hugely practical step-by-step tour of the A3 thinking process in her great article Create a Real A3, Do More than Fill In Boxes . In so doing she explains how an A3 is “a way of thinking with deeper benefits, a process based on the PDCA (plan, do, check, adjust) cycle designed to “share wisdom” with the rest of the organization.” Another terrific A3 “stroll” is provided in this recent piece by Jon Miller .