- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Overcoming Speech Impediment: Symptoms to Treatment

There are many causes and solutions for impaired speech

- Types and Symptoms

- Speech Therapy

- Building Confidence

Speech impediments are conditions that can cause a variety of symptoms, such as an inability to understand language or speak with a stable sense of tone, speed, or fluidity. There are many different types of speech impediments, and they can begin during childhood or develop during adulthood.

Common causes include physical trauma, neurological disorders, or anxiety. If you or your child is experiencing signs of a speech impediment, you need to know that these conditions can be diagnosed and treated with professional speech therapy.

This article will discuss what you can do if you are concerned about a speech impediment and what you can expect during your diagnostic process and therapy.

FG Trade / Getty Images

Types and Symptoms of Speech Impediment

People can have speech problems due to developmental conditions that begin to show symptoms during early childhood or as a result of conditions that may occur during adulthood.

The main classifications of speech impairment are aphasia (difficulty understanding or producing the correct words or phrases) or dysarthria (difficulty enunciating words).

Often, speech problems can be part of neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders that also cause other symptoms, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) or autism spectrum disorder .

There are several different symptoms of speech impediments, and you may experience one or more.

Can Symptoms Worsen?

Most speech disorders cause persistent symptoms and can temporarily get worse when you are tired, anxious, or sick.

Symptoms of dysarthria can include:

- Slurred speech

- Slow speech

- Choppy speech

- Hesitant speech

- Inability to control the volume of your speech

- Shaking or tremulous speech pattern

- Inability to pronounce certain sounds

Symptoms of aphasia may involve:

- Speech apraxia (difficulty coordinating speech)

- Difficulty understanding the meaning of what other people are saying

- Inability to use the correct words

- Inability to repeat words or phases

- Speech that has an irregular rhythm

You can have one or more of these speech patterns as part of your speech impediment, and their combination and frequency will help determine the type and cause of your speech problem.

Causes of Speech Impediment

The conditions that cause speech impediments can include developmental problems that are present from birth, neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s disease , or sudden neurological events, such as a stroke .

Some people can also experience temporary speech impairment due to anxiety, intoxication, medication side effects, postictal state (the time immediately after a seizure), or a change of consciousness.

Speech Impairment in Children

Children can have speech disorders associated with neurodevelopmental problems, which can interfere with speech development. Some childhood neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders may cause a regression (backsliding) of speech skills.

Common causes of childhood speech impediments include:

- Autism spectrum disorder : A neurodevelopmental disorder that affects social and interactive development

- Cerebral palsy : A congenital (from birth) disorder that affects learning and control of physical movement

- Hearing loss : Can affect the way children hear and imitate speech

- Rett syndrome : A genetic neurodevelopmental condition that causes regression of physical and social skills beginning during the early school-age years.

- Adrenoleukodystrophy : A genetic disorder that causes a decline in motor and cognitive skills beginning during early childhood

- Childhood metabolic disorders : A group of conditions that affects the way children break down nutrients, often resulting in toxic damage to organs

- Brain tumor : A growth that may damage areas of the brain, including those that control speech or language

- Encephalitis : Brain inflammation or infection that may affect the way regions in the brain function

- Hydrocephalus : Excess fluid within the skull, which may develop after brain surgery and can cause brain damage

Do Childhood Speech Disorders Persist?

Speech disorders during childhood can have persistent effects throughout life. Therapy can often help improve speech skills.

Speech Impairment in Adulthood

Adult speech disorders develop due to conditions that damage the speech areas of the brain.

Common causes of adult speech impairment include:

- Head trauma

- Nerve injury

- Throat tumor

- Stroke

- Parkinson’s disease

- Essential tremor

- Brain tumor

- Brain infection

Additionally, people may develop changes in speech with advancing age, even without a specific neurological cause. This can happen due to presbyphonia , which is a change in the volume and control of speech due to declining hormone levels and reduced elasticity and movement of the vocal cords.

Do Speech Disorders Resolve on Their Own?

Children and adults who have persistent speech disorders are unlikely to experience spontaneous improvement without therapy and should seek professional attention.

Steps to Treating Speech Impediment

If you or your child has a speech impediment, your healthcare providers will work to diagnose the type of speech impediment as well as the underlying condition that caused it. Defining the cause and type of speech impediment will help determine your prognosis and treatment plan.

Sometimes the cause is known before symptoms begin, as is the case with trauma or MS. Impaired speech may first be a symptom of a condition, such as a stroke that causes aphasia as the primary symptom.

The diagnosis will include a comprehensive medical history, physical examination, and a thorough evaluation of speech and language. Diagnostic testing is directed by the medical history and clinical evaluation.

Diagnostic testing may include:

- Brain imaging , such as brain computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic residence imaging (MRI), if there’s concern about a disease process in the brain

- Swallowing evaluation if there’s concern about dysfunction of the muscles in the throat

- Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (aka nerve conduction velocity, or NCV) if there’s concern about nerve and muscle damage

- Blood tests, which can help in diagnosing inflammatory disorders or infections

Your diagnostic tests will help pinpoint the cause of your speech problem. Your treatment will include specific therapy to help improve your speech, as well as medication or other interventions to treat the underlying disorder.

For example, if you are diagnosed with MS, you would likely receive disease-modifying therapy to help prevent MS progression. And if you are diagnosed with a brain tumor, you may need surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation to treat the tumor.

Therapy to Address Speech Impediment

Therapy for speech impairment is interactive and directed by a specialist who is experienced in treating speech problems . Sometimes, children receive speech therapy as part of a specialized learning program at school.

The duration and frequency of your speech therapy program depend on the underlying cause of your impediment, your improvement, and approval from your health insurance.

If you or your child has a serious speech problem, you may qualify for speech therapy. Working with your therapist can help you build confidence, particularly as you begin to see improvement.

Exercises during speech therapy may include:

- Pronouncing individual sounds, such as la la la or da da da

- Practicing pronunciation of words that you have trouble pronouncing

- Adjusting the rate or volume of your speech

- Mouth exercises

- Practicing language skills by naming objects or repeating what the therapist is saying

These therapies are meant to help achieve more fluent and understandable speech as well as an increased comfort level with speech and language.

Building Confidence With Speech Problems

Some types of speech impairment might not qualify for therapy. If you have speech difficulties due to anxiety or a social phobia or if you don’t have access to therapy, you might benefit from activities that can help you practice your speech.

You might consider one or more of the following for you or your child:

- Joining a local theater group

- Volunteering in a school or community activity that involves interaction with the public

- Signing up for a class that requires a significant amount of class participation

- Joining a support group for people who have problems with speech

Activities that you do on your own to improve your confidence with speaking can be most beneficial when you are in a non-judgmental and safe space.

Many different types of speech problems can affect children and adults. Some of these are congenital (present from birth), while others are acquired due to health conditions, medication side effects, substances, or mood and anxiety disorders. Because there are so many different types of speech problems, seeking a medical diagnosis so you can get the right therapy for your specific disorder is crucial.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Language and speech disorders in children .

Han C, Tang J, Tang B, et al. The effectiveness and safety of noninvasive brain stimulation technology combined with speech training on aphasia after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(2):e36880. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000036880

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick statistics about voice, speech, language .

Mackey J, McCulloch H, Scheiner G, et al. Speech pathologists' perspectives on the use of augmentative and alternative communication devices with people with acquired brain injury and reflections from lived experience . Brain Impair. 2023;24(2):168-184. doi:10.1017/BrImp.2023.9

Allison KM, Doherty KM. Relation of speech-language profile and communication modality to participation of children with cerebral palsy . Am J Speech Lang Pathol . 2024:1-11. doi:10.1044/2023_AJSLP-23-00267

Saccente-Kennedy B, Gillies F, Desjardins M, et al. A systematic review of speech-language pathology interventions for presbyphonia using the rehabilitation treatment specification system . J Voice. 2024:S0892-1997(23)00396-X. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2023.12.010

By Heidi Moawad, MD Dr. Moawad is a neurologist and expert in brain health. She regularly writes and edits health content for medical books and publications.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

Speech and Communication Disorders

Living with, related issues, see, play and learn.

- No links available

Statistics and Research

Clinical trials.

- Journal Articles

Reference Desk

Find an expert, patient handouts.

Many disorders can affect our ability to speak and communicate. They range from saying sounds incorrectly to being completely unable to speak or understand speech. Causes include:

- Hearing disorders and deafness

- Voice problems , such as dysphonia or those caused by cleft lip or palate

- Speech problems like stuttering

- Developmental disabilities

- Learning disabilities

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Brain injury

Some speech and communication problems may be genetic. Often, no one knows the causes. By first grade, about 5% of children have noticeable speech disorders. Speech and language therapy can help.

NIH: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

- Speech and Language Impairments (Center for Parent Information and Resources) Also in Spanish

- Speech to Speech Relay Service (Federal Communications Commission)

- Telecommunications Relay Service (TRS) (Federal Communications Commission)

- Aphasia vs. Apraxia (American Stroke Association)

Journal Articles References and abstracts from MEDLINE/PubMed (National Library of Medicine)

- Article: Development and validation of a predictive model for poor prognosis of...

- Article: Communication strategies for adults in palliative care: the speech-language therapists' perspective.

- Article: Pain assessment tools in adults with communication disorders: systematic review and...

- Speech and Communication Disorders -- see more articles

- Speech Problems (Nemours Foundation)

- Apraxia (Medical Encyclopedia) Also in Spanish

- Dysarthria (Medical Encyclopedia) Also in Spanish

- Phonological disorder (Medical Encyclopedia) Also in Spanish

- Selective mutism (Medical Encyclopedia) Also in Spanish

- Speech impairment in adults (Medical Encyclopedia) Also in Spanish

The information on this site should not be used as a substitute for professional medical care or advice. Contact a health care provider if you have questions about your health.

- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Doctorate Degrees

- Certificate Programs

- Nursing Degrees

- Cybersecurity

- Human Services

- Science & Mathematics

- Communication

- Liberal Arts

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science

- Admissions Overview

- Tuition and Financial Aid

- Incoming Freshman and Graduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Military Students

- International Students

- Early Access Program

- About Maryville

- Our Faculty

- Our Approach

- Our History

- Accreditation

- Tales of the Brave

- Student Support Overview

- Online Learning Tools

- Infographics

Home / Blog

Speech Impediment Guide: Definition, Causes, and Resources

December 8, 2020

Tables of Contents

What Is a Speech Impediment?

Types of speech disorders, speech impediment causes, how to fix a speech impediment, making a difference in speech disorders.

Communication is a cornerstone of human relationships. When an individual struggles to verbalize information, thoughts, and feelings, it can cause major barriers in personal, learning, and business interactions.

Speech impediments, or speech disorders, can lead to feelings of insecurity and frustration. They can also cause worry for family members and friends who don’t know how to help their loved ones express themselves.

Fortunately, there are a number of ways that speech disorders can be treated, and in many cases, cured. Health professionals in fields including speech-language pathology and audiology can work with patients to overcome communication disorders, and individuals and families can learn techniques to help.

Commonly referred to as a speech disorder, a speech impediment is a condition that impacts an individual’s ability to speak fluently, correctly, or with clear resonance or tone. Individuals with speech disorders have problems creating understandable sounds or forming words, leading to communication difficulties.

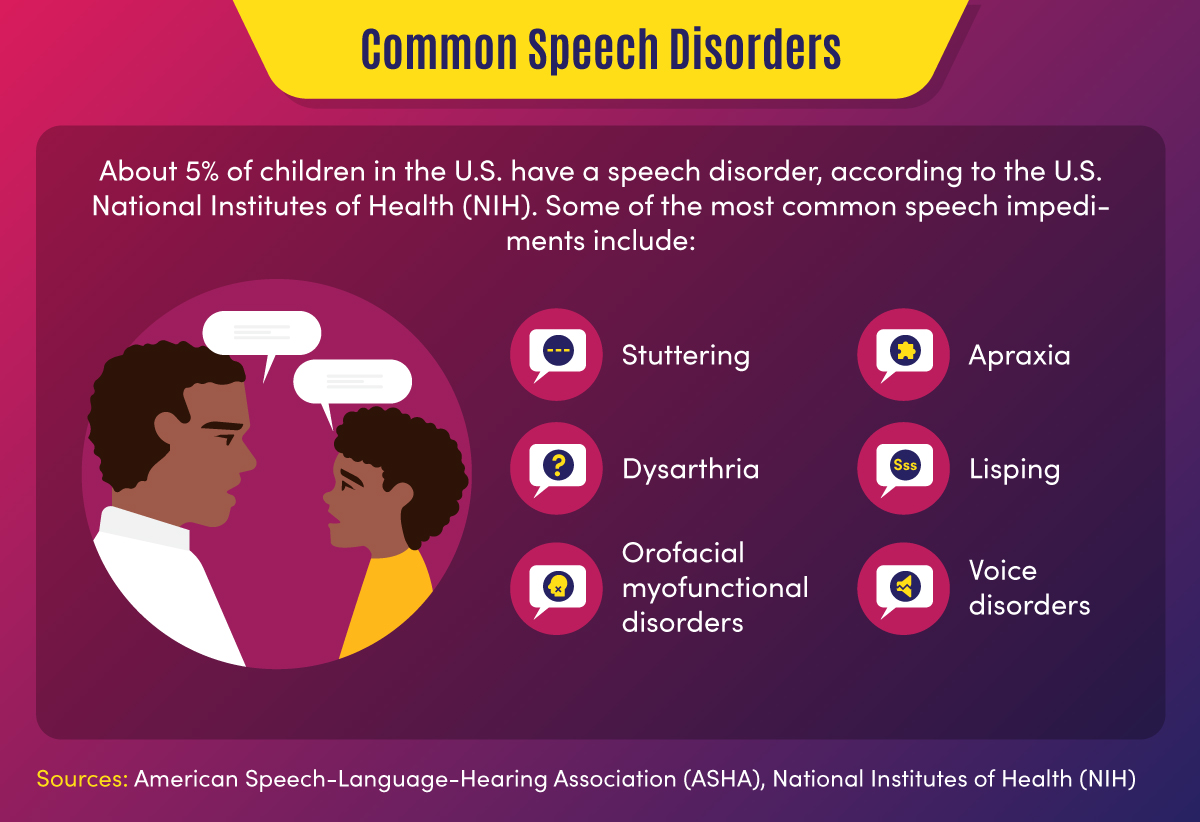

Some 7.7% of U.S. children — or 1 in 12 youths between the ages of 3 and 17 — have speech, voice, language, or swallowing disorders, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). About 70 million people worldwide, including some 3 million Americans, experience stuttering difficulties, according to the Stuttering Foundation.

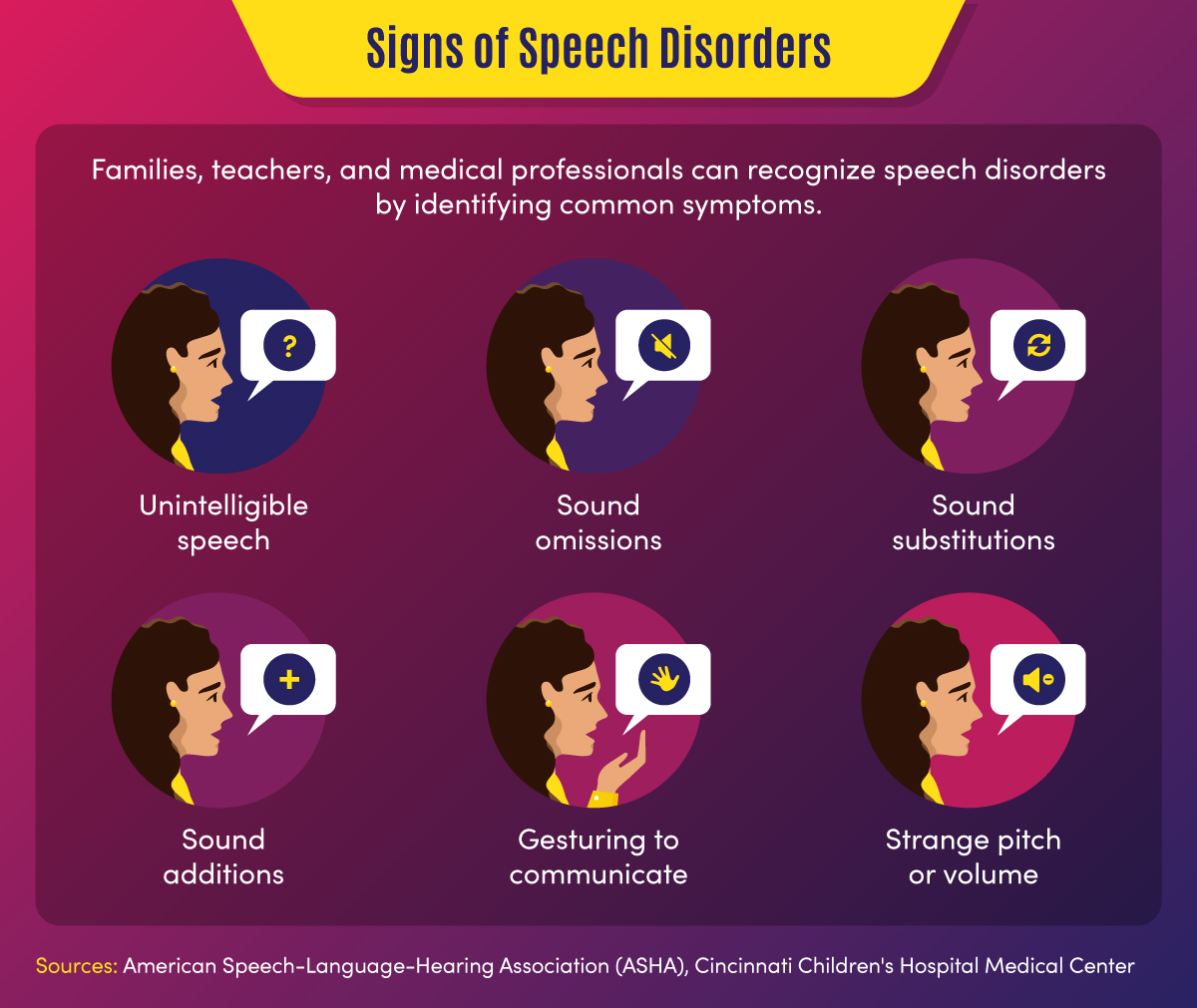

Common signs of a speech disorder

There are several symptoms and indicators that can point to a speech disorder.

- Unintelligible speech — A speech disorder may be present when others have difficulty understanding a person’s verbalizations.

- Omitted sounds — This symptom can include the omission of part of a word, such as saying “bo” instead of “boat,” and may include omission of consonants or syllables.

- Added sounds — This can involve adding extra sounds in a word, such as “buhlack” instead of “black,” or repeating sounds like “b-b-b-ball.”

- Substituted sounds — When sounds are substituted or distorted, such as saying “wabbit” instead of “rabbit,” it may indicate a speech disorder.

- Use of gestures — When individuals use gestures to communicate instead of words, a speech impediment may be the cause.

- Inappropriate pitch — This symptom is characterized by speaking with a strange pitch or volume.

In children, signs might also include a lack of babbling or making limited sounds. Symptoms may also include the incorrect use of specific sounds in words, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). This may include the sounds p, m, b, w, and h among children aged 1-2, and k, f, g, d, n, and t for children aged 2-3.

Back To Top

Categories of Speech Impediments

Speech impediments can range from speech sound disorders (articulation and phonological disorders) to voice disorders. Speech sound disorders may be organic — resulting from a motor or sensory cause — or may be functional with no known cause. Voice disorders deal with physical problems that limit speech. The main categories of speech impediments include the following:

Fluency disorders occur when a patient has trouble with speech timing or rhythms. This can lead to hesitations, repetitions, or prolonged sounds. Fluency disorders include stuttering (repetition of sounds) or (rapid or irregular rate of speech).

Resonance disorders are related to voice quality that is impacted by the shape of the nose, throat, and/or mouth. Examples of resonance disorders include hyponasality and cul-de-sac resonance.

Articulation disorders occur when a patient has difficulty producing speech sounds. These disorders may stem from physical or anatomical limitations such as muscular, neuromuscular, or skeletal support. Examples of articulation speech impairments include sound omissions, substitutions, and distortions.

Phonological disorders result in the misuse of certain speech sounds to form words. Conditions include fronting, stopping, and the omission of final consonants.

Voice disorders are the result of problems in the larynx that harm the quality or use of an individual’s voice. This can impact pitch, resonance, and loudness.

Impact of Speech Disorders

Some speech disorders have little impact on socialization and daily activities, but other conditions can make some tasks difficult for individuals. Following are a few of the impacts of speech impediments.

- Poor communication — Children may be unable to participate in certain learning activities, such as answering questions or reading out loud, due to communication difficulties. Adults may avoid work or social activities such as giving speeches or attending parties.

- Mental health and confidence — Speech disorders may cause children or adults to feel different from peers, leading to a lack of self-confidence and, potentially, self-isolation.

Resources on Speech Disorders

The following resources may help those who are seeking more information about speech impediments.

Health Information : Information and statistics on common voice and speech disorders from the NIDCD

Speech Disorders : Information on childhood speech disorders from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Speech, Language, and Swallowing : Resources about speech and language development from the ASHA

Children and adults can suffer from a variety of speech impairments that may have mild to severe impacts on their ability to communicate. The following 10 conditions are examples of specific types of speech disorders and voice disorders.

1. Stuttering

This condition is one of the most common speech disorders. Stuttering is the repetition of syllables or words, interruptions in speech, or prolonged use of a sound.

This organic speech disorder is a result of damage to the neural pathways that connect the brain to speech-producing muscles. This results in a person knowing what they want to say, but being unable to speak the words.

This consists of the lost ability to speak, understand, or write languages. It is common in stroke, brain tumor, or traumatic brain injury patients.

4. Dysarthria

This condition is an organic speech sound disorder that involves difficulty expressing certain noises. This may involve slurring, or poor pronunciation, and rhythm differences related to nerve or brain disorders.

The condition of lisping is the replacing of sounds in words, including “th” for “s.” Lisping is a functional speech impediment.

6. Hyponasality

This condition is a resonance disorder related to limited sound coming through the nose, causing a “stopped up” quality to speech.

7. Cul-de-sac resonance

This speech disorder is the result of blockage in the mouth, throat, or nose that results in quiet or muffled speech.

8. Orofacial myofunctional disorders

These conditions involve abnormal patterns of mouth and face movement. Conditions include tongue thrusting (fronting), where individuals push out their tongue while eating or talking.

9. Spasmodic Dysphonia

This condition is a voice disorder in which spasms in the vocal cords produce speech that is hoarse, strained, or jittery.

10. Other voice disorders

These conditions can include having a voice that sounds breathy, hoarse, or scratchy. Some disorders deal with vocal folds closing when they should open (paradoxical vocal fold movement) or the presence of polyps or nodules in the vocal folds.

Speech Disorders vs. Language Disorders

Speech disorders deal with difficulty in creating sounds due to articulation, fluency, phonology, and voice problems. These problems are typically related to physical, motor, sensory, neurological, or mental health issues.

Language disorders, on the other hand, occur when individuals have difficulty communicating the meaning of what they want to express. Common in children, these disorders may result in low vocabulary and difficulty saying complex sentences. Such a disorder may reflect difficulty in comprehending school lessons or adopting new words, or it may be related to a learning disability such as dyslexia. Language disorders can also involve receptive language difficulties, where individuals have trouble understanding the messages that others are trying to convey.

Resources on Types of Speech Disorders

The following resources may provide additional information on the types of speech impediments.

Common Speech Disorders: A guide to the most common speech impediments from GreatSpeech

Speech impairment in adults: Descriptions of common adult speech issues from MedlinePlus

Stuttering Facts: Information on stuttering indications and causes from the Stuttering Foundation

Speech disorders may be caused by a variety of factors related to physical features, neurological ailments, or mental health conditions. In children, they may be related to developmental issues or unknown causes and may go away naturally over time.

Physical and neurological issues. Speech impediment causes related to physical characteristics may include:

- Brain damage

- Nervous system damage

- Respiratory system damage

- Hearing difficulties

- Cancerous or noncancerous growths

- Muscle and bone problems such as dental issues or cleft palate

Mental health issues. Some speech disorders are related to clinical conditions such as:

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Down syndrome or other genetic syndromes

- Cerebral palsy or other neurological disorders

- Multiple sclerosis

Some speech impairments may also have to do with family history, such as when parents or siblings have experienced language or speech difficulties. Other causes may include premature birth, pregnancy complications, or delivery difficulties. Voice overuse and chronic coughs can also cause speech issues.

The most common way that speech disorders are treated involves seeking professional help. If patients and families feel that symptoms warrant therapy, health professionals can help determine how to fix a speech impediment. Early treatment is best to curb speech disorders, but impairments can also be treated later in life.

Professionals in the speech therapy field include speech-language pathologists (SLPs) . These practitioners assess, diagnose, and treat communication disorders including speech, language, social, cognitive, and swallowing disorders in both adults and children. They may have an SLP assistant to help with diagnostic and therapy activities.

Speech-language pathologists may also share a practice with audiologists and audiology assistants. Audiologists help identify and treat hearing, balance, and other auditory disorders.

How Are Speech Disorders Diagnosed?

Typically, a pediatrician, social worker, teacher, or other concerned party will recognize the symptoms of a speech disorder in children. These individuals, who frequently deal with speech and language conditions and are more familiar with symptoms, will recommend that parents have their child evaluated. Adults who struggle with speech problems may seek direct guidance from a physician or speech evaluation specialist.

When evaluating a patient for a potential speech impediment, a physician will:

- Conduct hearing and vision tests

- Evaluate patient records

- Observe patient symptoms

A speech-language pathologist will conduct an initial screening that might include:

- An evaluation of speech sounds in words and sentences

- An evaluation of oral motor function

- An orofacial examination

- An assessment of language comprehension

The initial screening might result in no action if speech symptoms are determined to be developmentally appropriate. If a disorder is suspected, the initial screening might result in a referral for a comprehensive speech sound assessment, comprehensive language assessment, audiology evaluation, or other medical services.

Initial assessments and more in-depth screenings might occur in a private speech therapy practice, rehabilitation center, school, childcare program, or early intervention center. For older adults, skilled nursing centers and nursing homes may assess patients for speech, hearing, and language disorders.

How Are Speech Impediments Treated?

Once an evaluation determines precisely what type of speech sound disorder is present, patients can begin treatment. Speech-language pathologists use a combination of therapy, exercise, and assistive devices to treat speech disorders.

Speech therapy might focus on motor production (articulation) or linguistic (phonological or language-based) elements of speech, according to ASHA. There are various types of speech therapy available to patients.

Contextual Utilization — This therapeutic approach teaches methods for producing sounds consistently in different syllable-based contexts, such as phonemic or phonetic contexts. These methods are helpful for patients who produce sounds inconsistently.

Phonological Contrast — This approach focuses on improving speech through emphasis of phonemic contrasts that serve to differentiate words. Examples might include minimal opposition words (pot vs. spot) or maximal oppositions (mall vs. call). These therapy methods can help patients who use phonological error patterns.

Distinctive Feature — In this category of therapy, SLPs focus on elements that are missing in speech, such as articulation or nasality. This helps patients who substitute sounds by teaching them to distinguish target sounds from substituted sounds.

Core Vocabulary — This therapeutic approach involves practicing whole words that are commonly used in a specific patient’s communications. It is effective for patients with inconsistent sound production.

Metaphon — In this type of therapy, patients are taught to identify phonological language structures. The technique focuses on contrasting sound elements, such as loud vs. quiet, and helps patients with unintelligible speech issues.

Oral-Motor — This approach uses non-speech exercises to supplement sound therapies. This helps patients gain oral-motor strength and control to improve articulation.

Other methods professionals may use to help fix speech impediments include relaxation, breathing, muscle strengthening, and voice exercises. They may also recommend assistive devices, which may include:

- Radio transmission systems

- Personal amplifiers

- Picture boards

- Touch screens

- Text displays

- Speech-generating devices

- Hearing aids

- Cochlear implants

Resources for Professionals on How to Fix a Speech Impediment

The following resources provide information for speech therapists and other health professionals.

Assistive Devices: Information on hearing and speech aids from the NIDCD

Information for Audiologists: Publications, news, and practice aids for audiologists from ASHA

Information for Speech-Language Pathologists: Publications, news, and practice aids for SLPs from ASHA

Speech Disorder Tips for Families

For parents who are concerned that their child might have a speech disorder — or who want to prevent the development of a disorder — there are a number of activities that can help. The following are tasks that parents can engage in on a regular basis to develop literacy and speech skills.

- Introducing new vocabulary words

- Reading picture and story books with various sounds and patterns

- Talking to children about objects and events

- Answering children’s questions during routine activities

- Encouraging drawing and scribbling

- Pointing to words while reading books

- Pointing out words and sentences in objects and signs

Parents can take the following steps to make sure that potential speech impediments are identified early on.

- Discussing concerns with physicians

- Asking for hearing, vision, and speech screenings from doctors

- Requesting special education assessments from school officials

- Requesting a referral to a speech-language pathologist, audiologist, or other specialist

When a child is engaged in speech therapy, speech-language pathologists will typically establish collaborative relationships with families, sharing information and encouraging parents to participate in therapy decisions and practices.

SLPs will work with patients and their families to set goals for therapy outcomes. In addition to therapy sessions, they may develop activities and exercises for families to work on at home. It is important that caregivers are encouraging and patient with children during therapy.

Resources for Parents on How to Fix a Speech Impediment

The following resources provide additional information on treatment options for speech disorders.

Speech, Language, and Swallowing Disorders Groups: Listing of self-help groups from ASHA

ProFind: Search tool for finding certified SLPs and audiologists from ASHA

Baby’s Hearing and Communication Development Checklist: Listing of milestones that children should meet by certain ages from the NIDCD

If identified during childhood, speech disorders can be corrected efficiently, giving children greater communication opportunities. If left untreated, speech impediments can cause a variety of problems in adulthood, and may be more difficult to diagnose and treat.

Parents, teachers, doctors, speech and language professionals, and other concerned parties all have unique responsibilities in recognizing and treating speech disorders. Through professional therapy, family engagement, positive encouragement and a strong support network, individuals with speech impediments can overcome their challenges and develop essential communication skills.

Additional Sources

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Speech Sound Disorders

Identify the Signs, Signs of Speech and Language Disorders

Intermountain Healthcare, Phonological Disorders

MedlinePlus, Speech disorders – children

National Institutes of Health, National Institutes on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, “Quick Statistics About Voice, Speech, Language”

Bring us your ambition and we’ll guide you along a personalized path to a quality education that’s designed to change your life.

Take Your Next Brave Step

Receive information about the benefits of our programs, the courses you'll take, and what you need to apply.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Types of Speech Impediments

Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SanjanaGupta-d217a6bfa3094955b3361e021f77fcca.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Phynart Studio / Getty Images

Articulation Errors

Ankyloglossia, treating speech disorders.

A speech impediment, also known as a speech disorder , is a condition that can affect a person’s ability to form sounds and words, making their speech difficult to understand.

Speech disorders generally become evident in early childhood, as children start speaking and learning language. While many children initially have trouble with certain sounds and words, most are able to speak easily by the time they are five years old. However, some speech disorders persist. Approximately 5% of children aged three to 17 in the United States experience speech disorders.

There are many different types of speech impediments, including:

- Articulation errors

This article explores the causes, symptoms, and treatment of the different types of speech disorders.

Speech impediments that break the flow of speech are known as disfluencies. Stuttering is the most common form of disfluency, however there are other types as well.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Disfluencies

These are some of the characteristics of disfluencies:

- Repeating certain phrases, words, or sounds after the age of 4 (For example: “O…orange,” “I like…like orange juice,” “I want…I want orange juice”)

- Adding in extra sounds or words into sentences (For example: “We…uh…went to buy…um…orange juice”)

- Elongating words (For example: Saying “orange joooose” instead of "orange juice")

- Replacing words (For example: “What…Where is the orange juice?”)

- Hesitating while speaking (For example: A long pause while thinking)

- Pausing mid-speech (For example: Stopping abruptly mid-speech, due to lack of airflow, causing no sounds to come out, leading to a tense pause)

In addition, someone with disfluencies may also experience the following symptoms while speaking:

- Vocal tension and strain

- Head jerking

- Eye blinking

- Lip trembling

Causes of Disfluencies

People with disfluencies tend to have neurological differences in areas of the brain that control language processing and coordinate speech, which may be caused by:

- Genetic factors

- Trauma or infection to the brain

- Environmental stressors that cause anxiety or emotional distress

- Neurodevelopmental conditions like attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Articulation disorders occur when a person has trouble placing their tongue in the correct position to form certain speech sounds. Lisping is the most common type of articulation disorder.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Articulation Errors

These are some of the characteristics of articulation disorders:

- Substituting one sound for another . People typically have trouble with ‘r’ and ‘l’ sounds. (For example: Being unable to say “rabbit” and saying “wabbit” instead)

- Lisping , which refers specifically to difficulty with ‘s’ and ‘z’ sounds. (For example: Saying “thugar” instead of “sugar” or producing a whistling sound while trying to pronounce these letters)

- Omitting sounds (For example: Saying “coo” instead of “school”)

- Adding sounds (For example: Saying “pinanio” instead of “piano”)

- Making other speech errors that can make it difficult to decipher what the person is saying. For instance, only family members may be able to understand what they’re trying to say.

Causes of Articulation Errors

Articulation errors may be caused by:

- Genetic factors, as it can run in families

- Hearing loss , as mishearing sounds can affect the person’s ability to reproduce the sound

- Changes in the bones or muscles that are needed for speech, including a cleft palate (a hole in the roof of the mouth) and tooth problems

- Damage to the nerves or parts of the brain that coordinate speech, caused by conditions such as cerebral palsy , for instance

Ankyloglossia, also known as tongue-tie, is a condition where the person’s tongue is attached to the bottom of their mouth. This can restrict the tongue’s movement and make it hard for the person to move their tongue.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Ankyloglossia

Ankyloglossia is characterized by difficulty pronouncing ‘d,’ ‘n,’ ‘s,’ ‘t,’ ‘th,’ and ‘z’ sounds that require the person’s tongue to touch the roof of their mouth or their upper teeth, as their tongue may not be able to reach there.

Apart from speech impediments, people with ankyloglossia may also experience other symptoms as a result of their tongue-tie. These symptoms include:

- Difficulty breastfeeding in newborns

- Trouble swallowing

- Limited ability to move the tongue from side to side or stick it out

- Difficulty with activities like playing wind instruments, licking ice cream, or kissing

- Mouth breathing

Causes of Ankyloglossia

Ankyloglossia is a congenital condition, which means it is present from birth. A tissue known as the lingual frenulum attaches the tongue to the base of the mouth. People with ankyloglossia have a shorter lingual frenulum, or it is attached further along their tongue than most people’s.

Dysarthria is a condition where people slur their words because they cannot control the muscles that are required for speech, due to brain, nerve, or organ damage.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Dysarthria

Dysarthria is characterized by:

- Slurred, choppy, or robotic speech

- Rapid, slow, or soft speech

- Breathy, hoarse, or nasal voice

Additionally, someone with dysarthria may also have other symptoms such as difficulty swallowing and inability to move their tongue, lips, or jaw easily.

Causes of Dysarthria

Dysarthria is caused by paralysis or weakness of the speech muscles. The causes of the weakness can vary depending on the type of dysarthria the person has:

- Central dysarthria is caused by brain damage. It may be the result of neuromuscular diseases, such as cerebral palsy, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. Central dysarthria may also be caused by injuries or illnesses that damage the brain, such as dementia, stroke, brain tumor, or traumatic brain injury .

- Peripheral dysarthria is caused by damage to the organs involved in speech. It may be caused by congenital structural problems, trauma to the mouth or face, or surgery to the tongue, mouth, head, neck, or voice box.

Apraxia, also known as dyspraxia, verbal apraxia, or apraxia of speech, is a neurological condition that can cause a person to have trouble moving the muscles they need to create sounds or words. The person’s brain knows what they want to say, but is unable to plan and sequence the words accordingly.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Apraxia

These are some of the characteristics of apraxia:

- Distorting sounds: The person may have trouble pronouncing certain sounds, particularly vowels, because they may be unable to move their tongue or jaw in the manner required to produce the right sound. Longer or more complex words may be especially harder to manage.

- Being inconsistent in their speech: For instance, the person may be able to pronounce a word correctly once, but may not be able to repeat it. Or, they may pronounce it correctly today and differently on another day.

- Grasping for words: The person may appear to be searching for the right word or sound, or attempt the pronunciation several times before getting it right.

- Making errors with the rhythm or tone of speech: The person may struggle with using tone and inflection to communicate meaning. For instance, they may not stress any of the words in a sentence, have trouble going from one syllable in a word to another, or pause at an inappropriate part of a sentence.

Causes of Apraxia

Apraxia occurs when nerve pathways in the brain are interrupted, which can make it difficult for the brain to send messages to the organs involved in speaking. The causes of these neurological disturbances can vary depending on the type of apraxia the person has:

- Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS): This condition is present from birth and is often hereditary. A person may be more likely to have it if a biological relative has a learning disability or communication disorder.

- Acquired apraxia of speech (AOS): This condition can occur in adults, due to brain damage as a result of a tumor, head injury , stroke, or other illness that affects the parts of the brain involved in speech.

If you have a speech impediment, or suspect your child might have one, it can be helpful to visit your healthcare provider. Your primary care physician can refer you to a speech-language pathologist, who can evaluate speech, diagnose speech disorders, and recommend treatment options.

The diagnostic process may involve a physical examination as well as psychological, neurological, or hearing tests, in order to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other causes.

Treatment for speech disorders often involves speech therapy, which can help you learn how to move your muscles and position your tongue correctly in order to create specific sounds. It can be quite effective in improving your speech.

Children often grow out of milder speech disorders; however, special education and speech therapy can help with more serious ones.

For ankyloglossia, or tongue-tie, a minor surgery known as a frenectomy can help detach the tongue from the bottom of the mouth.

A Word From Verywell

A speech impediment can make it difficult to pronounce certain sounds, speak clearly, or communicate fluently.

Living with a speech disorder can be frustrating because people may cut you off while you’re speaking, try to finish your sentences, or treat you differently. It can be helpful to talk to your healthcare providers about how to cope with these situations.

You may also benefit from joining a support group, where you can connect with others living with speech disorders.

National Library of Medicine. Speech disorders . Medline Plus.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Language and speech disorders .

Cincinnati Children's Hospital. Stuttering .

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick statistics about voice, speech, and language .

Cleveland Clinic. Speech impediment .

Lee H, Sim H, Lee E, Choi D. Disfluency characteristics of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms . J Commun Disord . 2017;65:54-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.12.001

Nemours Foundation. Speech problems .

Penn Medicine. Speech and language disorders .

Cleveland Clinic. Tongue-tie .

University of Rochester Medical Center. Ankyloglossia .

Cleveland Clinic. Dysarthria .

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Apraxia of speech .

Cleveland Clinic. Childhood apraxia of speech .

Stanford Children’s Hospital. Speech sound disorders in children .

Abbastabar H, Alizadeh A, Darparesh M, Mohseni S, Roozbeh N. Spatial distribution and the prevalence of speech disorders in the provinces of Iran . J Med Life . 2015;8(Spec Iss 2):99-104.

By Sanjana Gupta Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

- Follow Us On:

- What is the CPIR?

- What’s on the Hub?

- CPIR Resource Library

- Buzz from the Hub

- Event Calendar

- Survey Item Bank

- CPIR Webinars

- What are Parent Centers?

- National RAISE Center

- RSA Parent Centers

- Regional PTACs

- Find Your Parent Center

- CentersConnect (log-in required)

- Parent Center eLearning Hub

Select Page

Speech and Language Impairments

- En español | In Spanish

- See fact sheets on other disabilities

Table of Contents

A Day in the Life of an SLP

Christina is a speech-language pathologist. She works with children and adults who have impairments in their speech, voice, or language skills. These impairments can take many forms, as her schedule today shows.

First comes Robbie. He’s a cutie pie in the first grade and has recently been diagnosed with childhood apraxia of speech—or CAS. CAS is a speech disorder marked by choppy speech. Robbie also talks in a monotone, making odd pauses as he tries to form words. Sometimes she can see him struggle. It’s not that the muscles of his tongue, lips, and jaw are weak. The difficulty lies in the brain and how it communicates to the muscles involved in producing speech. The muscles need to move in precise ways for speech to be intelligible. And that’s what she and Robbie are working on.

Next, Christina goes down the hall and meets with Pearl in her third grade classroom. While the other students are reading in small groups, she works with Pearl one on one, using the same storybook. Pearl has a speech disorder, too, but hers is called dysarthria. It causes Pearl’s speech to be slurred, very soft, breathy, and slow. Here, the cause is weak muscles of the tongue, lips, palate, and jaw. So that’s what Christina and Pearl work on—strengthening the muscles used to form sounds, words, and sentences, and improving Pearl’s articulation.

One more student to see—4th grader Mario , who has a stutter. She’s helping Mario learn to slow down his speech and control his breathing as he talks. Christina already sees improvement in his fluency.

Tomorrow she’ll go to a different school, and meet with different students. But for today, her day is…Robbie, Pearl, and Mario.

Back to top

There are many kinds of speech and language disorders that can affect children. In this fact sheet, we’ll talk about four major areas in which these impairments occur. These are the areas of:

Articulation | speech impairments where the child produces sounds incorrectly (e.g., lisp, difficulty articulating certain sounds, such as “l” or “r”);

Fluency | speech impairments where a child’s flow of speech is disrupted by sounds, syllables, and words that are repeated, prolonged, or avoided and where there may be silent blocks or inappropriate inhalation, exhalation, or phonation patterns;

Voice | speech impairments where the child’s voice has an abnormal quality to its pitch, resonance, or loudness; and

Language | language impairments where the child has problems expressing needs, ideas, or information, and/or in understanding what others say. ( 1 )

These areas are reflected in how “speech or language impairment” is defined by the nation’s special education law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, given below. IDEA is the law that makes early intervention services available to infants and toddlers with disabilities, and special education available to school-aged children with disabilities.

Definition of “Speech or Language Impairment” under IDEA

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, defines the term “speech or language impairment” as follows:

Development of Speech and Language Skills in Childhood

Speech and language skills develop in childhood according to fairly well-defined milestones (see below). Parents and other caregivers may become concerned if a child’s language seems noticeably behind (or different from) the language of same-aged peers. This may motivate parents to investigate further and, eventually, to have the child evaluated by a professional.

______________________

More on the Milestones of Language Development

What are the milestones of typical speech-language development? What level of communication skill does a typical 8-month-old baby have, or a 18-month-old, or a child who’s just celebrated his or her fourth birthday?

You’ll find these expertly described in How Does Your Child Hear and Talk? , a series of resource pages available online at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA): http://www.asha.org/public/speech/development/chart.htm

Having the child’s hearing checked is a critical first step. The child may not have a speech or language impairment at all but, rather, a hearing impairment that is interfering with his or her development of language.

It’s important to realize that a language delay isn’t the same thing as a speech or language impairment. Language delay is a very common developmental problem—in fact, the most common, affecting 5-10% of children in preschool. ( 2 ) With language delay, children’s language is developing in the expected sequence, only at a slower rate. In contrast, speech and language disorder refers to abnormal language development. ( 3 ) Distinguishing between the two is most reliably done by a certified speech-language pathologist such as Christina, the SLP in our opening story.

Characteristics of Speech or Language Impairments

The characteristics of speech or language impairments will vary depending upon the type of impairment involved. There may also be a combination of several problems.

When a child has an articulation disorder , he or she has difficulty making certain sounds. These sounds may be left off, added, changed, or distorted, which makes it hard for people to understand the child.

Leaving out or changing certain sounds is common when young children are learning to talk, of course. A good example of this is saying “wabbit” for “rabbit.” The incorrect articulation isn’t necessarily a cause for concern unless it continues past the age where children are expected to produce such sounds correctly. ( 4 ) ( ASHA’s milestone resource pages , mentioned above, are useful here.)

Fluency refers to the flow of speech. A fluency disorder means that something is disrupting the rhythmic and forward flow of speech—usually, a stutter. As a result, the child’s speech contains an “abnormal number of repetitions, hesitations, prolongations, or disturbances. Tension may also be seen in the face, neck, shoulders, or fists.” ( 5 )

Voice is the sound that’s produced when air from the lungs pushes through the voice box in the throat (also called the larnyx), making the vocal folds within vibrate. From there, the sound generated travels up through the spaces of the throat, nose, and mouth, and emerges as our “voice.”

A voice disorder involves problems with the pitch, loudness, resonance, or quality of the voice. ( 6 ) The voice may be hoarse, raspy, or harsh. For some, it may sound quite nasal; others might seem as if they are “stuffed up.” People with voice problems often notice changes in pitch, loss of voice, loss of endurance, and sometimes a sharp or dull pain associated with voice use. ( 7 )

Language has to do with meanings, rather than sounds. ( 8 ) A language disorder refers to an impaired ability to understand and/or use words in context. ( 9 ) A child may have an expressive language disorder (difficulty in expressing ideas or needs), a receptive language disorder (difficulty in understanding what others are saying), or a mixed language disorder (which involves both).

Some characteristics of language disorders include:

- improper use of words and their meanings,

- inability to express ideas,

- inappropriate grammatical patterns,

- reduced vocabulary, and

- inability to follow directions. ( 10 )

Children may hear or see a word but not be able to understand its meaning. They may have trouble getting others to understand what they are trying to communicate. These symptoms can easily be mistaken for other disabilities such as autism or learning disabilities, so it’s very important to ensure that the child receives a thorough evaluation by a certified speech-language pathologist.

What Causes Speech and Language Disorders?

Some causes of speech and language disorders include hearing loss, neurological disorders, brain injury, intellectual disabilities, drug abuse, physical impairments such as cleft lip or palate, and vocal abuse or misuse. Frequently, however, the cause is unknown.

Of the 6.1 million children with disabilities who received special education under IDEA in public schools in the 2005-2006 school year, more than 1.1 million were served under the category of speech or language impairment. ( 11 ) This estimate does not include children who have speech/language problems secondary to other conditions such as deafness, intellectual disability, autism, or cerebral palsy. Because many disabilities do impact the individual’s ability to communicate, the actual incidence of children with speech-language impairment is undoubtedly much higher.

Finding Help

Because all communication disorders carry the potential to isolate individuals from their social and educational surroundings, it is essential to provide help and support as soon as a problem is identified. While many speech and language patterns can be called “baby talk” and are part of children’s normal development, they can become problems if they are not outgrown as expected.

Therefore, it’s important to take action if you suspect that your child has a speech or language impairment (or other disability or delay). The next two sections in this fact sheet will tell you how to find this help.

Help for Babies and Toddlers

Since we begin learning communication skills in infancy, it’s not surprising that parents are often the first to notice—and worry about—problems or delays in their child’s ability to communicate or understand. Parents should know that there is a lot of help available to address concerns that their young child may be delayed or impaired in developing communication skills. Of particular note is the the early intervention system that’s available in every state.

Early intervention is a system of services designed to help infants and toddlers with disabilities (until their 3rd birthday) and their families. It’s mandated by the IDEA. Through early intervention, parents can have their young one evaluated free of charge, to identify developmental delays or disabilities, including speech and language impairments.

If a child is found to have a delay or disability, staff work with the child’s family to develop what is known as an Individualized Family Services Plan , or IFSP . The IFSP will describe the child’s unique needs as well as the services he or she will receive to address those needs. The IFSP will also emphasize the unique needs of the family, so that parents and other family members will know how to support their young child’s needs. Early intervention services may be provided on a sliding-fee basis, meaning that the costs to the family will depend upon their income.

To identify the EI program in your neighborhood | Ask your child’s pediatrician for a referral to early intervention or the Child Find in the state. You can also call the local hospital’s maternity ward or pediatric ward, and ask for the contact information of the local early intervention program.

Back to top

Help for School-Aged Children, including Preschoolers

Just as IDEA requires that early intervention be made available to babies and toddlers with disabilities, it requires that special education and related services be made available free of charge to every eligible child with a disability, including preschoolers (ages 3-21). These services are specially designed to address the child’s individual needs associated with the disability—in this case, a speech or language impairment.

Many children are identified as having a speech or language impairment after they enter the public school system. A teacher may notice difficulties in a child’s speech or communication skills and refer the child for evaluation. Parents may ask to have their child evaluated. This evaluation is provided free by the public school system.

If the child is found to have a disability under IDEA—such as a speech-language impairment—school staff will work with his or her parents to develop an Individualized Education Program , or IEP . The IEP is similar to an IFSP. It describes the child’s unique needs and the services that have been designed to meet those needs. Special education and related services are provided at no cost to parents.

There is a lot to know about the special education process, much of which you can learn at the Center for Parent Information and Resources (CPIR). We offer a wide range of publications and resource pages on the topic. Enter our special education information at: http://www.parentcenterhub.org/repository/schoolage/

Educational Considerations

Communication skills are at the heart of the education experience. Eligible students with speech or language impairments will want to take advantage of special education and related services that are available in public schools.

The types of supports and services provided can vary a great deal from student to student, just as speech-language impairments do. Special education and related services are planned and delivered based on each student’s individualized educational and developmental needs.

Most, if not all, students with a speech or language impairment will need speech-language pathology services . This related service is defined by IDEA as follows:

(15) Speech-language pathology services includes—

(i) Identification of children with speech or language impairments;

(ii) Diagnosis and appraisal of specific speech or language impairments;

(iii) Referral for medical or other professional attention necessary for the habilitation of speech or language impairments;

(iv) Provision of speech and language services for the habilitation or prevention of communicative impairments; and

Thus, in addition to diagnosing the nature of a child’s speech-language difficulties, speech-language pathologists also provide:

- individual therapy for the child;

- consult with the child’s teacher about the most effective ways to facilitate the child’s communication in the class setting; and

- work closely with the family to develop goals and techniques for effective therapy in class and at home.

Speech and/or language therapy may continue throughout a student’s school years either in the form of direct therapy or on a consultant basis.

Assistive technology (AT) can also be very helpful to students, especially those whose physical conditions make communication difficult. Each student’s IEP team will need to consider if the student would benefit from AT such as an electronic communication system or other device. AT is often the key that helps students engage in the give and take of shared thought, complete school work, and demonstrate their learning.

Tips for Teachers

— Learn as much as you can about the student’s specific disability. Speech-language impairments differ considerably from one another, so it’s important to know the specific impairment and how it affects the student’s communication abilities.

— Recognize that you can make an enormous difference in this student’s life! Find out what the student’s strengths and interests are, and emphasize them. Create opportunities for success.

—If you are not part of the student’s IEP team, a sk for a copy of his or her IEP . The student’s educational goals will be listed there, as well as the services and classroom accommodations he or she is to receive.

— Make sure that needed accommodations are provided for classwork, homework, and testing. These will help the student learn successfully.

— Consult with others (e.g., special educators, the SLP) who can help you identify strategies for teaching and supporting this student, ways to adapt the curriculum, and how to address the student’s IEP goals in your classroom.

— Find out if your state or school district has materials or resources available to help educators address the learning needs of children with speech or language impairments. It’s amazing how many do!

— Communicate with the student’s parents . Regularly share information about how the student is doing at school and at home.

Tips for Parents

— Learn the specifics of your child’s speech or language impairment. The more you know, the more you can help yourself and your child.

— Be patient. Your child, like every child, has a whole lifetime to learn and grow.

— Meet with the school and develop an IEP to address your child’s needs. Be your child’s advocate. You know your son or daughter best, share what you know.

— Be well informed about the speech-language therapy your son or daughter is receiving. Talk with the SLP, find out how to augment and enrich the therapy at home and in other environments. Also find out what not to do!

— Give your child chores. Chores build confidence and ability. Keep your child’s age, attention span, and abilities in mind. Break down jobs into smaller steps. Explain what to do, step by step, until the job is done. Demonstrate. Provide help when it’s needed. Praise a job (or part of a job) well done.

— Listen to your child. Don’t rush to fill gaps or make corrections. Conversely, don’t force your child to speak. Be aware of the other ways in which communication takes place between people.

— Talk to other parents whose children have a similar speech or language impairment. Parents can share practical advice and emotional support. See if there’s a parent nearby by visiting the Parent to Parent USA program and using the interactive map.

— Keep in touch with your child’s teachers. Offer support. Demonstrate any assistive technology your child uses and provide any information teachers will need. Find out how you can augment your child’s school learning at home.

Readings and Articles

We urge you to read the articles identified in the References section. Each provides detailed and expert information on speech or language impairments. You may also be interested in:

Speech-Language Impairment: How to Identify the Most Common and Least Diagnosed Disability of Childhood http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2491683/

Organizations to Consult

ASHA | American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Information in Spanish | Información en español. 1.800.638.8255 | [email protected] | www.asha.org

NIDCD | National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders 1.800.241.1044 (Voice) | 1.800.241.1055 (TTY) [email protected] | http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/

American Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Association (ACPA) 1.800.242.5338 | https://acpacares.org/

Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America | CASANA http://www.apraxia-kids.org

National Stuttering Foundation 1.800.937.8888 | [email protected] | http://www.nsastutter.org/

Stuttering Foundation 1.800.992.9392 | [email protected] | http://www.stuttersfa.org/

1 | Minnesota Department of Education. (2010). Speech or language impairments . Online at: http://education.state.mn.us/MDE/EdExc/SpecEdClass/DisabCateg/SpeechLangImpair/index.html

2 | Boyse, K. (2008). Speech and language delay and disorder . Retrieved from the University of Michigan Health System website: http://www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/topics/speech.htm

4 | American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Speech sound disorders: Articulation and phonological processes . Online at: http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/speechsounddisorders.htm

5 | Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. (n.d.). Speech disorders . Online at: http://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/health/s/speech-disorder/

6 | National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2002). What is voice? What is speech? What is language? Online at: http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/voice/pages/whatis_vsl.aspx

7 | American Academy of Otolaryngology — Head and Neck Surgery. (n.d.). About your voice . Online at: http://www.entnet.org/content/about-your-voice

8 | Boyse, K. (2008). Speech and language delay and disorder . Retrieved from the University of Michigan Health System website: http://www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/topics/speech.htm

9 | Encyclopedia of Nursing & Allied Health. (n.d.). Language disorders . Online at: http://www.enotes.com/nursing-encyclopedia/language-disorders

10 | Ibid .

11 | U.S. Department of Education. (2010, December). Twenty-ninth annual report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act: 2007 . Online at: http://www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2007/parts-b-c/index.html

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Speech and Language Impairments

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, defines the term “speech or language impairment” as follows:

“(11) Speech or language impairment means a communication disorder, such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, or a voice impairment, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.” [34 CFR §300.8(c)(11]

(Parent Information and Resources Center, 2015)

Table of Contents

What is a Speech and Language Impairment?

Characteristics of speech or language impairments, interventions and strategies, related service provider-slp.

- A Day in the Life of an SLP

Assistive Technology

Speech and language impairment are basic categories that might be drawn in issues of communication involve hearing, speech, language, and fluency.

A speech impairment is characterized by difficulty in articulation of words. Examples include stuttering or problems producing particular sounds. Articulation refers to the sounds, syllables, and phonology produced by the individual. Voice, however, may refer to the characteristics of the sounds produced—specifically, the pitch, quality, and intensity of the sound. Often, fluency will also be considered a category under speech, encompassing the characteristics of rhythm, rate, and emphasis of the sound produced.

A language impairment is a specific impairment in understanding and sharing thoughts and ideas, i.e. a disorder that involves the processing of linguistic information. Problems that may be experienced can involve the form of language, including grammar, morphology, syntax; and the functional aspects of language, including semantics and pragmatics.

(Wikipedia, n.d./ Speech and Language Impairment)

*It’s important to realize that a language delay isn’t the same thing as a speech or language impairment. Language delay is a very common developmental problem—in fact, the most common, affecting 5-10% of children in preschool. With language delay, children’s language is developing in the expected sequence, only at a slower rate. In contrast, speech and language disorder refers to abnormal language development. Distinguishing between the two is most reliably done by a certified speech-language pathologist. (CPIR, 2015)

The characteristics of speech or language impairments will vary depending upon the type of impairment involved. There may also be a combination of several problems.

When a child has an articulation disorder , he or she has difficulty making certain sounds. These sounds may be left off, added, changed, or distorted, which makes it hard for people to understand the child.

Leaving out or changing certain sounds is common when young children are learning to talk, of course. A good example of this is saying “wabbit” for “rabbit.” The incorrect articulation isn’t necessarily a cause for concern unless it continues past the age where children are expected to produce such sounds correctly

Fluency refers to the flow of speech. A fluency disorder means that something is disrupting the rhythmic and forward flow of speech—usually, a stutter. As a result, the child’s speech contains an “abnormal number of repetitions, hesitations, prolongations, or disturbances. Tension may also be seen in the face, neck, shoulders, or fists.”

Voice is the sound that’s produced when air from the lungs pushes through the voice box in the throat (also called the larnyx), making the vocal folds within vibrate. From there, the sound generated travels up through the spaces of the throat, nose, and mouth, and emerges as our “voice.”

A voice disorder involves problems with the pitch, loudness, resonance, or quality of the voice. The voice may be hoarse, raspy, or harsh. For some, it may sound quite nasal; others might seem as if they are “stuffed up.” People with voice problems often notice changes in pitch, loss of voice, loss of endurance, and sometimes a sharp or dull pain associated with voice use.

Language has to do with meanings, rather than sounds. A language disorder refers to an impaired ability to understand and/or use words in context. A child may have an expressive language disorder (difficulty in expressing ideas or needs), a receptive language disorder (difficulty in understanding what others are saying), or a mixed language disorder (which involves both).

Some characteristics of language disorders include:

- improper use of words and their meanings,

- inability to express ideas,

- inappropriate grammatical patterns,

- reduced vocabulary, and

- inability to follow directions.

Children may hear or see a word but not be able to understand its meaning. They may have trouble getting others to understand what they are trying to communicate. These symptoms can easily be mistaken for other disabilities such as autism or learning disabilities, so it’s very important to ensure that the child receives a thorough evaluation by a certified speech-language pathologist.

(CPIR, 2015)

- Use the (Cash, Wilson, and DeLaCruz, n.d) reading and/or the [ESU 8 Wednesday Webinar] to develop this section of the summary.

Cash, A, Wilson, R. and De LaCruz, E.(n,d.) Practical Recommendations for Teachers: Language Disorders. https://www.education.udel.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/LanguageDisorders.pdf

[ESU 8 Wednesday Webinar] Speech Language Strategies for Classroom Teachers.- video below

Video: Speech Language Strategies for Classroom Teachers (15:51 minutes)’

[ESU 8 Wednesday Webinars]. (2015, Nov. 19) . Speech Language Strategies for Classroom Teachers. [Video FIle]. From https://youtu.be/Un2eeM7DVK8

Most, if not all, students with a speech or language impairment will need speech-language pathology services . This related service is defined by IDEA as follows:

(15) Speech-language pathology services include—

(i) Identification of children with speech or language impairments;

(ii) Diagnosis and appraisal of specific speech or language impairments;

(iii) Referral for medical or other professional attention necessary for the habilitation of speech or language impairments;

(iv) Provision of speech and language services for the habilitation or prevention of communicative impairments; and

(v) Counseling and guidance of parents, children, and teachers regarding speech and language impairments. [34 CFR §300.34(c)(15)]

Thus, in addition to diagnosing the nature of a child’s speech-language difficulties, speech-language pathologists also provide:

- individual therapy for the child;

- consult with the child’s teacher about the most effective ways to facilitate the child’s communication in the class setting; and

- work closely with the family to develop goals and techniques for effective therapy in class and at home.

Speech and/or language therapy may continue throughout a student’s school years either in the form of direct therapy or on a consultant basis.

A Day in the Life of an SLP

Christina is a speech-language pathologist. She works with children and adults who have impairments in their speech, voice, or language skills. These impairments can take many forms, as her schedule today shows.

First comes Robbie. He’s a cutie pie in the first grade and has recently been diagnosed with childhood apraxia of speech—or CAS. CAS is a speech disorder marked by choppy speech. Robbie also talks in a monotone, making odd pauses as he tries to form words. Sometimes she can see him struggle. It’s not that the muscles of his tongue, lips, and jaw are weak. The difficulty lies in the brain and how it communicates to the muscles involved in producing speech. The muscles need to move in precise ways for speech to be intelligible. And that’s what she and Robbie are working on.

Next, Christina goes down the hall and meets with Pearl in her third grade classroom. While the other students are reading in small groups, she works with Pearl one on one, using the same storybook. Pearl has a speech disorder, too, but hers is called dysarthria. It causes Pearl’s speech to be slurred, very soft, breathy, and slow. Here, the cause is weak muscles of the tongue, lips, palate, and jaw. So that’s what Christina and Pearl work on—strengthening the muscles used to form sounds, words, and sentences, and improving Pearl’s articulation.

One more student to see—4th grader Mario , who has a stutter. She’s helping Mario learn to slow down his speech and control his breathing as he talks. Christina already sees improvement in his fluency.

Tomorrow she’ll go to a different school, and meet with different students. But for today, her day is…Robbie, Pearl, and Mario.

Assistive technology (AT) can also be very helpful to students, especially those whose physical conditions make communication difficult. Each student’s IEP team will need to consider if the student would benefit from AT such as an electronic communication system or other device. AT is often the key that helps students engage in the give and take of shared thought, complete school work, and demonstrate their learning. (CPIR, 2015)

Project IDEAL , suggests two major categories of AT computer software packages to develop the child’s speech and language skills and augmentative or alternative communication (AAC).

Augmentative and alternative communication ( AAC ) encompasses the communication methods used to supplement or replace speech or writing for those with impairments in the production or comprehension of spoken or written language. Augmentative and alternative communication may used by individuals to compensate for severe speech-language impairments in the expression or comprehension of spoken or written language. AAC can be a permanent addition to a person’s communication or a temporary aid.

(Wikipedia, (n.d. /Augmentative and alternative communication)

Center for Parent Information and Resources (CPIR) (2015), Speech and Language Impairments, Newark, NJ, Author, Retrieved 4.1.19 from https://www.parentcenterhub.org/speechlanguage/

Wikipedia (n.d.) Augmentative and alternative communication. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augmentative_and_alternative_communication

Wikipedia, (n.d.) Speech and Language Impairment. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speech_and_language_impairment

Updated 8.8.23

Understanding and Supporting Learners with Disabilities Copyright © 2019 by Paula Lombardi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Healthy Habits

- Data and Statistics

- Resources for Child Development

- Positive Parenting Tips

- Keeping Children with Disabilities Safe

Developmental Disability Basics

What to know.

- Developmental disabilities are a group of conditions due to an impairment in physical, learning, language, or behavior areas.