Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Effects of rhetorical devices on audience responses with online videos: An augmented elaboration likelihood model

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Interactive Media, School of Communication, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong, China

Roles Data curation, Resources

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation College of Communication, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Roles Data curation

Affiliation College of Liberal Arts, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang City, Jiangxi, 330022, China

- Guangchao Charles Feng,

- Yiwen Luo,

- Zhenwei Yu,

- Jinlang Wen

- Published: March 16, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282663

- Reader Comments

The way in which information is linguistically presented can impact audience attention, emotion, and cognitive responses, even if the content remains unchanged. The present study aims to examine the effects of rhetorical devices on audience responses by introducing a new theoretical framework, the augmented elaboration likelihood model (A-ELM), which integrates elements of the Elaboration Likelihood Model and narrative theory. The results show that the mediation effects of attention on the relationships between rhetorical devices and affective and cognitive elaborations are moderated by involvement. Nonnarrative evidence, combined narrative and numerical evidence, source credibility, and tropes versus the lack of figures of speech, elicit better audience responses in low-involvement situations, whereas numerical evidence outperforms narratives in high-involvement situations. This study not only offers a novel theoretical framework in the form of A-ELM, but also has important implications for advancing methodologies and practical applications.

Citation: Feng GC, Luo Y, Yu Z, Wen J (2023) Effects of rhetorical devices on audience responses with online videos: An augmented elaboration likelihood model. PLoS ONE 18(3): e0282663. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282663

Editor: Krzysztof Stepaniuk, Bialystok University of Technology: Politechnika Bialostocka, POLAND

Received: December 12, 2022; Accepted: February 20, 2023; Published: March 16, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Feng et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from Figshare ( https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19498751.v1 ).

Funding: Specific grant numbers (grant no.: 18BXW082) Initials of authors who received each award (GF) Full names of commercial companies that funded the study or authors (no commercial companies are involved) Initials of authors who received salary or other funding from commercial companies (na) URLs to sponsors’ websites ( http://www.nopss.gov.cn/ ) The funder (National Social Science Fund of China) had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The manner in which information is linguistically presented has a profound impact on how audiences attend to, process, and respond to it emotionally, even when the content remains the same [ 1 ]. This is particularly relevant in today’s digital world, where online videos have become a prevalent form of media consumption. These videos are not only used for entertainment purposes, but they also serve as sources of information dissemination, product advertising, and political campaigning [ 2 ]. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the role of narratives and rhetorical strategies in shaping audience responses to online videos, particularly given the widespread influence of these videos on society.

Despite numerous studies exploring the persuasive effects of linguistic styles, there is still a gap in our understanding of how rhetorical strategies interact to influence audience responses in real-world settings. Most prior studies have relied on small-scale empirical studies to examine the effects of rhetorical figures on various outcomes, such as attention, ad attitudes, brand attitudes, purchase intention, preference, and memorability [ 3 – 7 ]. These studies have often ignored the potential interaction between rhetorical figures and other message features, such as narratives.

To fill this gap, the present study aims to investigate the effects of rhetorical devices and the possible interactions among them on audience responses to online videos. By combining big data mining and content analysis methods, this study seeks to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between narratives and rhetorical devices and audience responses. The study also proposes an integrated framework that incorporates theories from information processing and narratives, which has the potential to address the inconsistent and mixed findings of prior studies.

This new study is necessary as it has the potential to inform the development of more effective communication strategies and deepen our understanding of how language shapes the way in which we attend to, process, and respond to information, particularly in the context of online videos. With the growing influence of online videos, a better understanding of the interplay between message strategies and audience responses has the potential to lead to more impactful and effective communication.

Audience responses

Prior research has demonstrated that the use of rhetorical figures in messages can enhance audience engagement by eliciting responses in attention, cognitive (i.e., thoughts), and affective (i.e., feelings) elaborations [ 8 , 9 ]. These responses are susceptible to different message features and heuristic cues, and rhetorical devices serve as relevant influencers. For instance, Weber [ 10 ] discovered that less factual news is conducive to audiences’ perceived relevance and engagement among many news (message) factors. This finding alludes to the positive effect of narratives and other rhetorical devices on audience responses, each of which will be reviewed below.

Thoroughly examining the relationships among attentive (e.g., viewing or the first time clicking), cognitive (e.g., commenting), and affective (e.g., liking) responses is beyond the scope of the present study. Nevertheless, it is widely accepted that attention acts as a gatekeeper for both cognitive and affective responses [ 11 – 14 ]. This is especially relevant in the context of online videos, where users must click on the video to view it before they can engage with it through likes, shares, and comments. The relationship between cognition and affect, however, remains a topic of intense debate [ 15 – 17 ]. Rather than delving into this debate, this study considers affective and cognitive elaborations as parallel response variables of attention.

Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Attention to the headline is positively associated with subsequent affective (e.g., liking) (H1a) and cognitive elaborations [i.e., nonverbal (e.g., sharing) and verbal (e.g., commenting) elaborations (H1b)].

In what follows, various rhetorical devices, particularly narratives and figures of speech, and their effects on audience responses are reviewed, and hypotheses and research questions are raised accordingly.

Definitions.

Scholars from different disciplines have provided varying definitions of the term “narrative”. It is considered a symbolic representation of events [ 18 , 19 ]. [ 20 ] expanded the definition of narratives to include stories with plots and chronological sequences of events [ 19 , 21 ]. Although “narrative” often appears as a generic term in the literature, it can encompass various forms, such as personal stories, anecdotes, eyewitness accounts, entertainment-education content, and testimonials [ 20 , 22 ].

Narrative effects.

Previous research has consistently demonstrated the persuasive effects of narratives. The underlying mechanism is that once individuals become immersed in the story, there is a transportation effect that causes people to perceive the story as realistic and identify with its characters [ 23 ]. According to [ 23 ], individuals who are transported into a narrative world are likely to change their real-world beliefs through reduced negative cognitive responses and counterarguments, the realism of the experience, and strong affective responses [also see 24 ]. These findings are echoed by the extended elaboration likelihood model [ 24 ], the entertainment overcoming resistance model (EORM) [ 25 ], and exemplification theory [ 26 ].

While many studies have confirmed the persuasive effect of narrative content, some scholars have challenged these findings. Some have found a nonsignificant [ 27 ] or even reversed [ 28 ] effect of narratives versus nonnarratives on attitude changes or knowledge and perception. In addition [ 29 – 32 ], have found that a particular form of nonnarrative, i.e., numerical evidence, is more persuasive than narrative evidence. [ 33 ] contended that numerical evidence has a stronger effect than narrative evidence on beliefs and attitudes, whereas narrative evidence has a stronger influence on intentions. Follow-up studies by [ 29 , 34 ] found that a message combining narrative and numerical evidence is more persuasive than using either form of evidence alone. This finding was also replicated by [ 35 ].

Moderation effect of involvement on the relationship between narratives and responses.

[ 36 ] attributed mixed findings regarding the persuasive effects of narratives and numerical evidence to the influence of involvement. [ 36 ] also found that narrative testimonials are more compelling than numerical evidence under low involvement conditions. indicating that the effect of narrative is a heuristic process [ 36 ]. [ 37 ] suggested that individuals who are highly engaged in a narrative should have low levels of involvement and ability in scrutinizing a persuasive argument, while those highly involved in a compelling argument should concentrate on the quality of claims.

A series of related hypotheses are raised below:

H2: The effects of other forms of nonnarrative evidence, numerical evidence, and combined narrative and numerical evidence on attention are stronger than those of narrative evidence depending on the level of involvement. Specifically, narrative evidence receives greater attention than other forms of nonnarrative evidence (H2a), numerical evidence (H2b), and combined narrative and numerical evidence (H2c) under low involvement conditions.

H3: The indirect effects of other forms of nonnarrative evidence, numerical evidence, and combined narrative and numerical evidence on liking are stronger than those of narrative evidence depending on the level of involvement. Specifically, narrative evidence receives higher levels of liking than other forms of nonnarrative evidence (H3a), numerical evidence (H3b), and combined narrative and numerical evidence (H3c) under low involvement conditions.

H4: Similar to H3, narrative evidence receives higher levels of cognitive elaboration than other forms of nonnarrative evidence (H4a), numerical evidence (H4b), and combined narrative and numerical evidence (H4c) under low involvement conditions.

Figures of speech

Conceptualization..

A figure of speech (FoS), defined as “a form of speech artfully varied from common usage” [ 38 ], is a vital message style that affects persuasive effects [ 39 ]. Although over two hundred different figures have been cataloged, many are variants of approximately forty general types of figures of speech [ 40 ] [also cf. [ 41 ]]. These figures of speech can be divided into two major groups, i.e., tropes and schemes [ 38 ]. Tropes, including specific figures such as metaphors, puns, and associations, involve the substitution or destabilization of the meaning of a word that is a deviation from what it usually signifies. Schemes, which are characterized by the reversal of word order, omissions, insertions, repetitions, and rhyme, deviate from customary grammatical structure [ 5 , 38 , 40 ]. In the same vein, [ 42 ] classified rhetorical figures into two types, namely, metabolas and parataxis, which correspond to tropes and schemes, respectively.

The persuasive effects of rhetorical figures have been examined in various contexts and found to be effective, for example, advertisements that use rhetorical figures are more likely to garner greater attention [ 3 ], ad attitudes, brand attitudes, purchase intention [ 4 ], preference, and memorability [ 5 – 7 ].

Moderation effect of involvement on the relationship between FoS and responses.

The persuasive effects of a figure of speech (FoS) have also been found to be moderated by involvement. In studying a specific type of FoS, i.e., rhetorical questions, [ 43 ] found that the effect of rhetorical questions on message attention and elaboration is stronger at levels of low involvement. The reason for this is that rhetorical questions can distract message recipients from processing arguments and can also make recipients perceive pressure from the source [ 44 ]. A similar finding has been observed in a few ad copy studies [ 7 , 45 , 46 ]. Consequently, a series of related hypotheses are proposed below:

H5: Tropes (H5a) and schemes (H5b) receive greater attention than literal texts that do not use any figures of speech under low involvement conditions.

H6: The mediation effects of attention on the relationships between figures of speech and affective elaboration (liking) are moderated by involvement such that tropes (H6a) and schemes (H6b) receive higher levels of liking than literal texts that do not use figures of speech under low involvement conditions.

H7: The mediation effects of attention on the relationships between figures of speech and cognitive elaboration are moderated by involvement such that tropes (H7a) and schemes (H7b) receive higher elaboration than literal texts that do not use any figures of speech under low involvement conditions.

Source credibility

As reviewed above, the credibility of information sources [for a review of the conceptualization and operationalization, see 47 ] affects the effect of persuasion [ 48 ]. Previous studies have found that highly credible (trustworthy and competent) sources produce a more positive attitude toward advocacy than do sources that are perceived to be less credible [for a review, see [ 49 ]].

Moderation effect of involvement on the relationship between source credibility and responses.

The persuasive effect of source credibility is moderated by involvement [also cf. [ 50 , 51 ]]. When people have little involvement in an issue, a source with low credibility will induce a more positive attitude than will a more credible communicator [ 52 ]. According to the dual-process theories reviewed above, source credibility belongs to one of the peripheral cues that people rely on mainly under low involvement conditions in information processing [ 53 , 54 ] [for a review, see [ 55 ]]. That is, a highly credible source has a positive persuasive effect only when the level of involvement is low.

The following series of related hypotheses are raised accordingly:

H8: The effect of source credibility on attention is higher under low involvement conditions.

H9: The mediation effect of attention on the relationships between source credibility and liking is moderated by involvement such that higher levels of source credibility receives a higher level of liking under low involvement conditions.

H10: The mediation effect of attention on the relationships between source credibility and cognitive elaboration is moderated by involvement such that the higher level of source credibility receives higher levels of cognitive elaboration under low involvement conditions.

Augmented ELM (A-ELM)

The kind of processing strategy that a message recipient employs depends on the number of mental resources the recipient is motivated to allocate to such information processing [ 56 ]. Moreover, due to the varied mental resources (involvement, ability, and opportunity), the recipient will follow two relatively distinct routes in persuasion [ 57 ]. This theorizing is well documented in dual-process models, including the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) [ 57 , 58 ], the heuristics-systematic model (HSM) [ 59 ], the motivation, opportunity, and ability model (MOA) [ 60 ], and others.

The extended elaboration likelihood model (E-ELM) [ 24 , 61 ] hypothesizes that the processing process and outcome of entertainment content are determined by one’s engagement with the story plot and characters. Authors have argued that only involvement with the characters rather than issue involvement is relevant in such a context [ 24 ]. Nevertheless, such theorizing assumes that all entertainment content is homogeneous in substance, forms, and styles. [ 62 ] proposed the language complexity (simple vs. complex) × processing mode (automatic vs. controlled) framework (LCPMF), which considers the abovementioned variations of content. However, the relationship between language complexity and processing mode is entangled, and the LCPMF has never been empirically applied. In addition, language complexity may not fully account for the variation in processing strategies. For instance, a message recipient who is emotionally engaged with the story plot and characters or finds the message entertaining may maintain a constant processing mode, regardless of its level of complexity.

Moreover, the LCPMF fails to consider any cues other than language complexity, such as language intensity [ 63 ], narrative or numerical evidence, or the credibility of content creators, which might affect the processing strategies adopted. The present study proposes a new integrated theoretical framework called the augmented ELM (A-ELM) by incorporating narrative theory and the ELM. The A-ELM, as shown in Fig 1 , comprises all the hypotheses and research questions raised above. In summary, it maintains that the mediation effects of attention (click to view) on the relationships between rhetorical devices and elaborations are moderated by issue involvement.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282663.g001

Data mining.

Most data were collected from two major video-sharing websites in China, namely, Xigua Video (2,648,807 items or 35% of the total) and Bilibili (4,919,998 items or 65% of the total), through data scraping using a crawler programmed with Python. The elements of data to be scraped include the title of the video and the audience responses received for the content, which include the number of views, the number of likes, the number of saves, the number of shares, the number of danmaku (Danmu or bullet chats), and the number of comments, among others. In addition, the attribute information, including the visibility of the issue covered in the text and the author’s impact, e.g., the number of followers, was collected.

Content analysis and codebook.

After the data had been collected from the websites, ten thousand randomly sampled items were subjected to further content analysis (9,244 were left after removing those titles with fewer than five characters). The tests addressing the hypotheses and research questions were based on the coding results of the content analysis. Five senior-year undergraduate and four postgraduate students majoring in the Chinese language were recruited to code the sampled data according to the codebook.

The codebook describes and explains the categories of each variable, which will work as the independent variables used in later hypothesis testing. The coded independent variables included figures of speech [three categories including 1) tropes, 2) schemes, and 3) none] and types of evidence [four categories including 1) narrative, 2) numerical, 3) the combination of the two, and 4) other Nonnarrative evidence].

Each of the coders was trained by one of the three research assistants (RAs) and allowed to start formal coding only after their coding results had satisfactory intercoder reliability with those of a corresponding RA. The RAs also randomly chose samples of coding results from each coder to check their coding quality every day. If intercoder reliability was a problem, the coder of concern was asked to recode certain content.

The intercoder reliability test using the frequently used indices showed that all the categories’ intercoder reliability was satisfactory [ 64 – 67 ]. In addition to the results of the intercoder reliability test, the tables are also presented in the online appendix ( https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19498751.v1 ) due to the space limit.

Audience responses to headlines.

As discussed above [ 8 , 9 ], audience responses to headlines include paying attention to the headline (viewing) and subsequent affective (e.g., liking the story) and cognitive (e.g., commenting) elaborations after watching the video. These metrics were collected by scraping the relevant websites.

Viewing was measured by the number of viewers ( M = 547,654, SD = 1,056,431, N = 9,244).

Affective Elaboration.

Affective elaboration, or liking, was measured by the number of likes ( M = 26,521, SD = 65,718, N = 8,182).

Cognitive Elaboration.

Cognitive elaboration was measured by the number of shares ( M = 2155, SD = 8,308, N = 8,168), the number of saves ( M = 6,311, SD = 24,119, N = 8,168), the number of comments ( M = 692, SD = 1,825, N = 9,242), and the number of Danmaku (overlaying comments on video displays) ( M = 3,398, SD = 8,747, N = 5,022).

Principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was performed to examine the scale’s dimensionality based on the big data ( N = 7,568,805). The number of extracted factors in the PCA was determined based on the eigenvalue-greater-than-one rule [ 68 ]. The PCA yielded two factors (verbal and nonverbal cognitive elaborations) that explained 85% of the variance in the items. The factor loadings of verbal elaboration were .86 (comments) and .90 (Danmaku), and the Cronbach’s α was .72. The factor loadings of nonverbal elaboration were .94 (shares) and .95 (saves), and the Cronbach’s α was .87. Given the acceptable performance on validity and reliability, the dimensionality results derived from PCA were used in the following structural equation modeling (SEM).

Independent variables

Types of evidence..

The four categories of evidence were coded as narrative (70.857%), numerical (.876%), the combination of the two (1.309%), and other nonnarrative evidence (26.958%).

Figures of Speech.

There were three included categories of figures of speech, i.e., tropes (18.714%), schemes (12.166%), and none (69.120%).

Source Credibility.

Source credibility was measured by the number of followers of content creators ( M = 1,025,659, SD = 3,386,276, N = 9,244) and the fame of content creators.

The Number of Followers.

The number of followers a content creator has is often used as a peripheral cue by consumers to gauge the creator’s trustworthiness and credibility [ 69 , 70 ]. Moreover, [ 69 ] discovered a positive effect of the number of followers a celebrity has on the subject’s perception of the celebrity’s attractiveness, trustworthiness, and competence [cf. 71 ]. This information was collected by scraping the existing data of the websites.

The Fame of Content Creators.

The authors of videos come from a variety of sources, including 1) traditional media, 2) new media platforms, 3) official organizations, 4) nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), 5) celebrities, 6) ordinary anchors (equivalent to YouTubers), and 7) famous anchors. A cluster analysis was performed to rank the content creators by the degree of fame. The result showed three ordered categories of fame, i.e., 6, 2 and 7 combined, and the rest combined.

The same PCA procedures as those discussed above were performed on the two items based on the big data ( N = 7,568,805). The PCA yielded one factor that explained 79% of the variance in the items. The factor loadings were .8 and .88, and the Cronbach’s α was .865.

Issue Involvement.

Involvement can indicate the importance of an issue and the amount of needed effort to process information [ 72 ] [for a taxonomy of involvement, see [ 73 ]]. The study’s data sources could be a natural proxy measure of involvement due to the difference in the needed effort of browsing. The two video platforms have very diverse user bases. The users of Bilibili are mostly generation Z and fans of ACGN (animations, comics, games, and novels) [ 74 , 75 ], while the users of Xigua are, in general, generally older people who care about serious topics [ 76 , 77 ]. Therefore, the users of Bilibili who aim to seek stimulation have a shorter attention span and are less likely to pay attention to the details in the text of titles [cf. 78 ] than those of Xigua. In light of the fundamental difference in the user characteristics of the two platforms, the level of involvement was measured by the sources of the videos. Bilibili (Bilibili = 2, 31.556%) and Xigua (Xigua = 1, 68.444%) indicate conditions of high and low involvement, respectively.

Control Variables.

There were two control variables that served as control variables, i.e., topic visibility and the date difference between publishing and crawling times.

Topic Visibility.

Topic visibility or familiarity, which might affect attention, worked as a control variable [cf. 79 ]. The visibility of the concerning event or people, as often displayed in social media metrics, indicates the object’s popularity [ 80 ]. This visibility also serves as a heuristic cue for the algorithms and the users of video websites alike to perceive that object as valuable and noteworthy [ 81 ]. This variable must be controlled because the trending topic easily dominates the attention of users, and people are hence less likely to be affected by the rhetorical strategies contained in the title that has recently been widely discussed on social media.

The visibility of the concerned topic was measured by the number of search times obtained by scraping the “hot searches” provided by Weibo, which is a Twitter-like website in China. The video titles are matched with the “hot searches” database during the same period. Those that were successfully matched received a rating score of visibility, whereas those that failed to match were left blank (NA) ( M = 812,146, SD = 1,062,156, N = 8,499).

Date Differences.

Videos published in earlier days will have more extended viewing periods and, hence, a better chance to be viewed ( M = 171, SD = 294, N = 8,473). Controlling for the effect of this date difference aimed to rule out the influence resulting from the artifact.

Model specification.

As stated in the hypotheses and RQs above, attention mediates the effects of rhetorical devices on affective and cognitive elaborations. Moreover, such a mediation process is moderated by the level of involvement, which forms the moderated mediation model [for a review of this method, see [ 82 ]]. In light of [ 82 ], the significant prediction of either a j (the prediction from predictor X to mediator M ) or b j (the prediction from M to dependent variable Y ) depending on moderator W indicates the presence of moderated mediation. The predictions of a j depending on W (involvement) have been included in H5 and H6, while the predictions of b j are not dependent on involvement due to a lack of theoretical support.

Dataset and analysis

The data were scraped, cleaned, and manipulated using Python 3.7. The dataset is stored on the online repository ( https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19498751.v1 ). Some analyses (e.g., PCA and reliability test) and data manipulation also employed R 3.6, and hypothesis testing using structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed with M plus 8.6 [ 83 ]. The collection and analysis method complied with the terms and conditions for the source of the data.

Results and discussions

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the mixed-effects null model was .295, indicating that 29.5% of the variance was accounted for by clustering. As a result, multilevel modeling was necessary. The hypotheses and research questions were addressed using multilevel moderated mediation modeling with SEM and the Monte Carlo and numerical integration method, which. However, this method made χ 2 and related fit statistics unavailable.

All the measurement models were significant. The number of shares and saves were significantly loaded on the factor of nonverbal cognitive elaboration, whereas the number of comments and danmaku were significantly loaded on the factor of verbal cognitive elaboration. Moreover, the two factors were significantly loaded on a single factor, which is simplified as cognitive elaboration. In addition, the number of followers and the fame of content creators were significantly loaded on a single factor, i.e., source credibility.

Both affective elaboration (i.e., the number of likes) and cognitive elaboration were significantly predicted by attention (i.e., the number of viewers) ( β = .713, p <.001; β = .423, p <.001). That is, higher levels of attention translate into higher levels of affective and cognitive elaborations. Consequently, H1 was supported.

Depending on the level of involvement, the effects of other forms of nonnarratives (vs. narratives) and combined narrative and numerical evidence on attention were significant ( β = .043, p <.01; β = .176, p <.01. That is, nonnarrative evidence and combined narrative and numerical evidence attract more viewers than narrative evidence under low involvement conditions. Numerical evidence attracts more viewers under high involvement conditions, as expected, but this effect was insignificant ( β = −.111, p = .179). Consequently, H2a and H2c were supported, but H2b was rejected.

Regarding the effect of figures of speech (FoS) on attention, only the effect of tropes (vs. nonuse of FoS) was significant ( β = .061, p <.01). That is, tropes can attract more viewers than literal texts under low involvement conditions. Nevertheless, there was no significant difference in attracting viewers between schemes and the nonuse of FoS. Consequently, H5a was supported, but H5b was rejected.

The effect of source credibility on attention was significant ( β = 32.211, p <.001). That is, the higher the source credibility is, the more viewers there are when the involvement level is low. Therefore, H8 was supported.

The effect of the control variables (i.e., visibility of the issue and date difference) on attention was also significant ( β = −.062, p <.001; β = .116, p <.001). Higher levels of visibility attract fewer viewers under low involvement conditions. The longer that videos are published, the more viewers they have. In summary, controlling for the effects of visibility and date difference, the effects of numerical and other forms of nonnarrative evidence, tropes, and source credibility on attention were significant depending on the varying level of involvement.

The moderated mediation effects of attention on the relationships between rhetorical devices (and source credibility) and affective elaboration (e.g., liking), and cognitive elaboration had mixed results. The effects of the combination of narrative and numerical evidence, other forms of nonnarrative (vs. narrative) evidence, tropes (vs. nonuse of figure of speech), and source credibility on both affective and cognitive elaborations were significantly mediated by attention depending on the level of involvement. There were significant moderated mediation effects of the combination of narrative and numerical evidence, other forms of nonnarrative evidence, tropes and source credibility on liking, i.e., affective elaboration( β = .251, p <.01; β = .061, p <.01; β = .087, p <.001; β = 45.957, p <.001) and cognitive elaboration ( β = .149, p <.01; β = .036, p <.01; β = .051, p <.05; β = 27.258, p <.001). Consequently, H3a, H3c, H4a, H4c, H6a, H7a, H9, and H10 were supported, but H3b, H4b, H6b, and H7b were rejected.

The relationships between the mediator (i.e., attention) and affective and cognitive elaborations were significant. Attention clearly plays the role of a gatekeeper for subsequent responses. Nevertheless, the effects of linguistic devices and source credibility on responses were not consistent.

There are significant and moderated (by involvement) mediation effects of attention on the relationships between the predictors [other forms of nonnarrative (vs. narrative) evidence, the combination of narrative and numerical evidence, tropes (vs. nonuse of figure of speech), and source credibility] and both affective and cognitive elaborations. When the level of involvement was low, the combination of narrative and numerical evidence, other forms of nonnarrative evidence, tropes, and source credibility had positive effects on audience responses. In contrast, visibility had positive effects on responses under high involvement conditions. The positive effects of other forms of nonnarrative evidence and the combination of narrative and numerical evidence under low involvement conditions could be attributed to two factors.

First, in the context of video viewing, the titles using narratives have already included a synopsis of their stories. If users have low issue involvement, then they lack the motivation to click to watch the video. Second, an untested three-way interaction may exist on top of the moderation of involvement. For instance, the genre of videos, which is an attribute not reported by Xigua Video, may moderate the interaction effect of involvement and evidence types. In addition, older age groups are more easily attracted by narratives, while members of generation Z [ 75 ], who comprise the staple user base of Bilibili, prefer nonnarratives with or without numbers over narratives in their browsing [cf. 84 ].

Research implications

This study has made substantial theoretical contributions by proposing an augmented ELM (A-ELM) that combines narrative theory and dual-process theories into a unified theoretical framework. The A-ELM represents an improvement over previous ELM(s) in multiple ways.

The A-ELM is different from the E-ELM [ 24 , 61 ], which holds that the audience’s emotional engagement (transportation) is only relevant to high levels of involvement with the plots and characters. Involvement with the plots and characters is different from issue involvement. The former, which is a core concept in the E-ELM, should be better conceptualized as narrative engagement, while the latter is simply involvement that the ELM refers to. Moreover, the E-ELM contends that communication outcomes are determined by involvement with the story plot and characters, while the A-ELM maintains that mere narrative evidence is detrimental to communication outcomes when issue involvement is low. The underlying reason is that users lack the motivation to process the information further when they are not interested in the issue per se.

The A-ELM provides a fresh perspective on the debate over the persuasive impact of narratives versus numerical evidence. Nonnarratives should be differentiated between numerical and nonnumerical ones. Numerical evidence indicating a higher argument quality works better under high involvement conditions. In contrast, other nonnarrative evidence is believed to have better audience responses under low involvement conditions.

In addition, tropes and source credibility have better effects on audience responses under the low involvement condition, while video titles that address social issues tend to attract users with high levels of involvement.

The present study employed two methods, i.e., big data mining and content analysis. The validity and reliability of the measurement scales were first confirmed based on big data collected from the natural setting, and then the hypotheses and research questions were examined based on randomly selected data subjected to content analysis. In addition, the study adopted innovative multilevel moderated mediation modeling based on Monte Carlo integration. Therefore, this study has made several methodological contributions to the field.

This study not only has theoretical and methodological implications, but also practical implications for video creators. Depending on the users that a video targets, video creators can choose specific rhetorical devices to grab attention. Specifically, creators should use nonnarrative evidence and figures such as metaphors, puns, and other similar tropes in video titles to engage young users who lack persistent levels of involvement. Nevertheless, video titles with numerical evidence and public issues work best to engage older users who are interested in serious topics.

Conclusions

This study found that attention (number of viewers) is a significant predictor of affective (number of likes) and cognitive (e.g., number of comments) elaborations. Higher levels of attention result in higher levels of affective and cognitive elaborations. This study also found that nonnarrative evidence and combined narrative and numerical evidence attract more viewers than narrative evidence under low involvement. The use of tropes in figures of speech was found to attract more viewers than literal texts under low involvement. It implies that when reading texts with tropes and non-narratives, users apparently process those messages effortlessly as peripheral cues. Users, however, process numerical information, particularly concerning trending social issues, in an effortful and systematic way.

Source credibility was found to have a significant effect on attention, with higher credibility leading to more viewers under low involvement. The control variables, i.e., visibility of the issue and date difference, were also found to have a significant effect on attention.

Limitations

The mixed results of the study could be attributed to several limitations. Firstly, the study only utilized data from two major video-sharing websites in China, which may have resulted in the exclusion of other important sources and websites. Secondly, the impact of narratives on communication could be influenced by transportation and narrative involvement, but the extent of narrative involvement was not accessible to the study. Finally, due to the use of secondary data, many constructs were measured using a limited number of items, leading to concerns about reliability.

Future research directions

Based on the limitations mentioned above, future research directions in this area could include:

- To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the communication effects of rhetorical devices and narratives, the scope of data sources could be expanded to include additional video-sharing websites, such as those in China and beyond, including YouTube [cf. 2].

- Enhancing Measurement Reliability. To address the reliability concerns in the measurement of constructs, future research could utilize multiple items or more robust measures. Furthermore, while the primary users of the two video-sharing platforms were originally comprised of Generation Z and older adults, these platforms are now evolving to attract a more diverse range of age groups. Therefore, the measurement of involvement could be improved by using additional variables such as content focus (e.g. political vs entertainment).

- Investigating the effects of rhetorical devices and narratives in different contexts. The effects of rhetorical devices and narratives may vary across different communication contexts, such as in politics, entertainment, advertising, or health. Future research could examine the effects in these different contexts and compare the results to the findings of this study.

- Conducting qualitative studies to complement the quantitative findings, and explore the underlying mechanisms and processes that explain the communication effects of rhetorical devices and narratives.

These future research directions could help to further our understanding of the effects of rhetorical devices and narratives on communication outcomes and inform the development of more effective communication strategies that use rhetorical devices and narratives.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 3. Berlyne DE. Aesthetics and psychobiology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1971.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 12. Lazarus RS. The cognition–emotion debate: A bit of history. In: Dalgleish T, Power M, editors. Handbook of cognition and emotion. New York, NY, US: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1999. p. 3–19.

- 14. Wilson BJ, Gottman JM. Attention—The Shuttle Between Emotion and Cognition: Risk, Resiliency, and Physiological Bases. Stress, Coping, and Resiliency in Children and Families: Psychology Press; 1996.

- 18. Abbott HP. Defining narrative. 2 ed. Abbott HP, editor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. 13–27 p.

- 19. Gabriel Y. Stories and Narratives. 2018 2021/07/28. In: The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: Methods and Challenges [Internet]. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/the-sage-handbook-of-qualitative-business-and-management-research-methods-v2 .

- 38. Corbett EP. Classical rhetoric. NEW YORK: Oxford University Press; 1965.

- 39. Shen L, Bigsby E. The effects of message features: Content, structure, and style. The SAGE handbook of persuasion: Developments in theory and practice, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 2013. p. 20–35.

- 42. Barthes R. Rhetoric of the Image. Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang; 1977. p. 32–51.

- 58. Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York, NY: Springer New York; 1986. p. 1–24.

- 59. Chaiken S. The heuristic model of persuasion. Social influence: The Ontario symposium, Vol 5. Ontario symposium on personality and social psychology. Hillsdale, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1987. p. 3–39.

- 61. Slater MD. Involvement as Goal-Directed Strategic Processing: Extending the Elaboration Likelihood Model. In: Dillard JP, Pfau M, editors. The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2002.

- 77. Fang W. Zhongshipin Sanwanjia Luxian Zhizheng: Xigua de Suanfa, B zhan de Quanzi, Zhihu de Da V China: Jiemian Xinwen; 2021. Available from: https://www.jiemian.com/article/5634681.html .

- 80. Marwick AE. Status update—celebrity, publicity, and branding in the social media age. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2013.

- 83. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: the comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers: user’s guide. 8.3 ed. Los Angeles, CA: MuthÈn & MuthÈn; 2019.

Using rhetorical appeals to credibility, logic, and emotions to increase your persuasiveness

- The Writer’s Craft

- Open access

- Published: 07 May 2018

- Volume 7 , pages 207–210, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lara Varpio 1

63k Accesses

12 Citations

68 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Wherever there is meaning there is persuasion. —Kenneth Burke [ 1 ]

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the Writer’s Craft section we offer simple tips to improve your writing in one of three areas: Energy, Clarity and Persuasiveness. Each entry focuses on a key writing feature or strategy, illustrates how it commonly goes wrong, teaches the grammatical underpinnings necessary to understand it and offers suggestions to wield it effectively. We encourage readers to share comments on or suggestions for this section on Twitter, using the hashtag: #how’syourwriting?

Scientific research is, for many, the epitome of objectivity and rationality. But, as Burke reminds us, conveying the meaning of our research to others involves persuasion. In other words, when I write a research manuscript, I must construct an argument to persuade the reader to accept my rationality .

While asserting that scientific findings must be persuasively conveyed may seem contradictory, it is simply a consequence of how we conduct research. Scientific research is a social activity centred on answering challenging questions. When these questions are answered, the solutions we propose are just that—propositions. Our solutions are accepted by the community until another, better proposition offers a more compelling explanation. In other words, everything we know is accepted for now but not forever .

This means that when we write up our research findings, we need to be persuasive. We must convince readers to accept our findings and the conclusions we draw from them. That acceptance may require dethroning widely held perspectives. It may require having the reader adopt new ways of thinking about a phenomenon. It may require convincing the audience that other, highly respected researchers are wrong. Regardless of the argument I want the reader to accept, I have to persuade the reader to agree with me .

Therefore, being a successful researcher requires developing the skills of persuasion—the skills of a rhetorician. Fortunately for the readers of Perspectives on Medical Education, The Writer’s Craft series offers a treasure trove of rhetorical tools that health professions education researchers can mine.

A primary lesson of rhetoric was developed by Aristotle. He studied rhetoric analytically, investigating all the means of persuasion available in a given situation. He identified three appeals at play in all acts of persuasion: ethos, logos and pathos. The first is focused on the author, the second on the argument, the third on the reader. Together, they support effective persuasion, and so can be harnessed by researchers to powerfully convey the meaning of their research.

Ethos is the appeal focused on the writer. It refers to the character of the writer, including her credibility and trustworthiness. The reader must be convinced that the author is an authority and merits attention. In scientific research, the author must establish her credibility as a rigorous and expert researcher. Much of an author’s ethos, then, lies in using well-reasoned and justified research methodologies and methods. But, a writer’s credibility can be bolstered using a number of rhetorical techniques including similitude and deference .

Similitude appeals to similarities between the author and the reader to create a sense of mutual identification. Using pronouns like we and us, the writer reinforces commonality with the reader and so encourages a sense of cohesion and community. To illustrate, consider the following:

While burnout continues to plague our residents , medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. We owe it to our residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service.

While burnout continues to plague residents , medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. Medical educators owe it to their residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service.

In the first sentence, the author aligns herself with the community of medical educators involved in residency education. The writer is part of the we who has to support residents. She makes the burnout problem something she and the reader are both called upon to address. In the second sentence, the author separates herself from this community of educators. She creates social distance between herself and the reader, and thus places the burden of resolving the problem more squarely on the shoulders of the reader than herself.

Both phrasings are equally correct, grammatically. One creates social connection, the other social distance.

Deference is a way for the author to signal respect for others, and personal humility. The writer can demonstrate deference by using phrases such as in my opinion , or through the use of adjectives (e.g., Smith rigorously studied) or adverbs (e.g., the important work by Jones). For example:

The thoughtful research conducted by Jane Doe et al. suggests that resident burnout is more prevalent among those learners who were shamed by attending physicians. Echoing the calls of others [ 1 ], we contend that this work should be extended to also consider the role of fellow learners as potential contributors to resident experiences of burnout.

In this sentence, the author does not present Jane Doe and colleagues as weak researchers, nor as developing findings that should be rejected. Instead, it shows deference to these researchers by acknowledging the quality of their research and a willingness to build on the foundation provided by their findings. (Note how the author also builds ethos via similitude with other scholars by calling the reader’s attention to the fact that other researchers have also called for more research on the author’s suggested extension of Doe’s work).

Readers pick up on the respect authors pay to other researchers. Being rude or unkind in our writing rarely achieves anything except reflecting poorly on the writer.

In sum, as my grandmother used to say: ‘You’ll slide farther on honey than gravel.’ Establishing similitude and showing deference helps to establish your ethos as an author. They help the writer make honey, not gravel.

Logos is the rhetorical appeal that focuses on the argument being presented by the author. It is an appeal to rationality, referring to the clarity and logical integrity of the argument. Logos is, therefore, primarily rooted in the reasoning that holds different elements of the manuscript’s argument together. Do the findings logically connect to support the conclusion being drawn? Are there errors in the author’s reasoning (i.e., logical fallacies) that undermine the logic presented in the manuscript? Logical fallacies will undercut the persuasive power of a manuscript. Authors are well advised to spend time mapping out the premises of their arguments and how they logically lead to the conclusions being drawn, avoiding common errors in reasoning (see Purdue’s on-line writing lab [ 2 ] for 12 of the most common logical fallacies that plague authors, complete with definitions and examples).

However, logos is not merely contained in the logic of the argument itself. Logos is only achieved if the reader is able to follow the author’s logic. To support the reader’s ability to process the logical argument presented in the manuscript, authors can use signposting. Signposting is often accomplished via words (e.g., first, next, specifically, alternatively, also, consequently, etc.) and phrases (e.g., as a result, and yet, for example, in conclusion, etc.) that help the reader to follow the line of reasoning as it moves through the manuscript. Signposts indicate to the reader the structure of the argument to come, where they are in the argument at the moment, and/or what they can expect to come next. Consider the following sentence from one of my own manuscripts. This is the last sentence in the Introduction [ 3 ]:

This study addresses these gaps by investigating the following questions: 1. How often are residents taught informally by physicians and nurses in clinical settings? 2. What competencies are informally taught to residents by physicians and nurses? 3. What teaching techniques are used by physicians and nurses to deliver informal education?

At the end of the Introduction, this sentence offers a map to the reader of how the paper’s argument will develop. The reader can now expect that the manuscript will address each of these questions, in this order. I could also use large-scale signposting, such as sub-headings in the Results, to organize the reading of data related to each of these questions. In the Discussion, I can use small-scale signpost terms and phrases (i.e., however, in contrast, in addition, finally, etc.) to help the reader follow the progression of the argument I am presenting .

I must offer one word of caution here: be sure to use your signposts precisely. If not, your writing will not be logically developed and you will weaken the logos at work in the manuscript. For instance, however signposts a contrasting or contradicting idea:

I enjoy working with residents; however , I loathe completing in-training evaluation reports.

If the writer uses the wrong signpost, the meaning of the sentence falls apart, and so does the logos:

I enjoy working with residents; alternatively , I loathe completing in-training evaluation reports.

Alternatively indicates a different option or possibility. This sentence does not present two different alternatives; it presents two contrasting ideas. Using alternatively confuses the meaning of the sentence, and thus impairs logos.

With clear and precise signposting, the reader will easily follow your argument across the manuscript. This supports the logos you develop as you guide the reader to your conclusions.

Pathos is the rhetorical appeal that focuses on the reader. Pathos refers to the emotions that are stirred in the reader while reading the manuscript. The author should seek to trigger specific emotional reactions in their writing. And, yes, there is room for emotions in scientific research articles. Some of my favourite manuscripts in The Writer’s Craft series are those that help authors elicit specific emotions from the reader.

For instance, in Joining the conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic Lingard highlights the importance of ‘hooking’ your audience. The hook ‘convinces readers that this gap [in the current literature] is of consequence’ [ 4 ]. The author must persuade the reader that the argument is important and worthy of the reader’s attention. This is an appeal to the readers’ emotions.

Another example is found in Bonfire red titles. As Lingard explains, the title of your manuscript is ‘advertising for what is inside your research paper’ [ 5 ]. The title must attract the readers’ attention and create a desire within them to read your manuscript. Here, again, is pathos in action in a scientific research paper: grab the reader’s attention from the very first word of the title.

Beyond those already addressed in The Writer’s Craft series, another rhetorical technique that appeals to the emotions of the reader is the strategic use of God-terms [ 1 ] . Burke defined God-terms as words or phrases that are ‘the ultimates of motivation,’ embodying characteristics that are fundamentally valued by humans. To use an analogy from card games (e.g., bridge or euchre), God-terms are like emotional trump cards. God-terms like freedom, justice, and duty call on shared human values, trumping contradictory feelings. By alluding to God-terms in our research, we increase the emotional appeal of our writing. Let us reconsider the example from above:

While burnout continues to plague our residents, medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. We owe it to our residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service .

Here, the author reminds the reader that residents will be in service as physicians for their lifetime, and that we have a duty (i.e., we owe it ) to support them in that calling to meet the public’s healthcare needs. Invoking the God-terms of service and duty, the writer taps into the reader’s sense of responsibility to support these learners.

It is important not to overplay pathos in a scientific research paper—i.e., readers are keenly intelligent scholars who will easily identify emotional exaggeration. Consider this variation on the previous example:

While burnout continues to ruin the lives of our residents, medical educators have neglected to identify the root causes of this problem. We have a moral obligation to our residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service.

This rephrasing is likely to create a sense of unease in the reader because of the emotional exaggerations it uses. By over-amplifying the appeals to emotion, this rephrasing elicits feelings of refusal and rejection in the reader. Instead of drawing the reader in, it pushes the reader away. When it comes to pathos, a light hand is best.

Peter Gould famously stated: ‘data can never speak for themselves’ [ 6 ]. Researchers must explain them. In that explaining, we endeavour to convince the audience that our propositions should be accepted. While the science in our research is at the core of that persuasion, there are techniques from rhetoric that can help us convince readers to accept our arguments. Ethos, logos and pathos are appeals that, when used intentionally and judiciously, can buoy the persuasive power of your manuscripts.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States of America’s Department of Defense or other federal agencies.

Burke K. A rhetoric of motives. Berkley: University of California Press; 1969. p. 72.

Google Scholar

Purdue Online Writing Lab. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University. 1995. 2018. https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/659/03/ . Accessed 3 Mar 2018.

Varpio L, Bidlake E, Casimiro L, et al. Resident experiences of informal education: how often, from whom, about what and how. Med Educ. 2014;48:1220–34.

Article Google Scholar

Lingard L. Joining a conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4:252–3.

Lingard L. Bonfire red titles. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5:179–81.

Gould P. Letting the data speak for themselves. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2005;71:166–76.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, USA

Lara Varpio

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lara Varpio .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Varpio, L. Using rhetorical appeals to credibility, logic, and emotions to increase your persuasiveness. Perspect Med Educ 7 , 207–210 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0420-2

Download citation

Published : 07 May 2018

Issue Date : June 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0420-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Reading Skills

Analyzing rhetorical devices.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: December 22, 2023

What We Review

Introduction

Welcome to an exciting exploration of rhetoric and its powerful tools, known as rhetorical devices. Rhetoric is the art of using language effectively to persuade and communicate. Rhetorical devices are like special tricks that speakers and writers use to make their messages more convincing and impactful. These techniques are crucial because they shape the way we understand what people say or write, whether it’s in old speeches and books or in things we see and hear today.

Understanding rhetorical devices is crucial for anyone looking to enhance their analytical skills, as it allows for a deeper understanding of how arguments are constructed and what makes them effective. This knowledge is not just academic; it’s a practical tool that can improve your critical thinking, reading, and writing abilities.

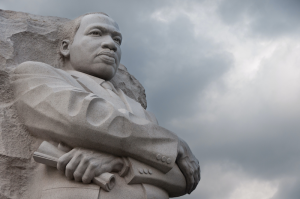

In this guide, we will delve into the most common rhetorical devices, break down why they’re used, and show you how to spot them in different texts. We’ll also explore the principles of ethos, pathos, and logos, which are the foundation of persuasive communication. To make these ideas come to life, we’ll analyze Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” a text that’s filled with rhetorical strategies.

Get ready to embark on a journey that will deepen your understanding of language and its incredible power to persuade, inform, and move people. Let’s begin by unlocking the secrets of rhetorical devices and their role in shaping compelling communication.

Why Is Rhetoric Important?

Rhetoric is a very old skill that goes back to ancient Greece, where thinkers like Aristotle first talked about it. It’s all about using language in a smart way to achieve different goals, like convincing, informing, entertaining, or motivating people. What makes it important is that you can use it in many different situations, whether you want to shape what people think about something or just talk to someone.

In today’s world, where we have a lot of information, knowing about rhetoric is super useful. It helps us make messages that are interesting and strong, and it also helps us look carefully at what others are saying and decide if it makes sense. Understanding rhetoric isn’t just about talking well; it’s also about listening carefully and being part of good conversations. It’s a basic skill for talking effectively, thinking carefully, and being an active member of society.

When we study rhetoric, we learn not only how to say things in a way that convinces others but also how to figure out when others are trying to convince us. This double skill is really important in today’s world, where there’s a lot of talking and sharing ideas. It helps us understand and take part in important discussions.

What are Rhetorical Devices?

Rhetorical devices are tools and techniques that writers, speakers, and everyday people use to make their messages more effective. These tools are important because they help us build strong arguments, stir up emotions, and make complex ideas easier to understand. They’re not just fancy tricks; they’re essential for good communication.

Rhetorical Devices Examples

Rhetorical devices are the tools used to enhance persuasion and understanding in communication. They can add clarity, depth, and emotional impact to your message. Here’s a look at some widely recognized and powerful rhetorical devices, each with its unique influence on the audience.

Ethos is all about making the person who’s talking or writing seem believable and trustworthy. It’s like showing that they know what they’re talking about and that they’re honest. When people do this, it helps convince others that they can be trusted. For instance, when a doctor talks about health, they might mention their medical degree to show that they really know what they’re talking about, and that way, people will trust what they say.

Pathos is when you try to make the people you’re talking to feel something. It’s about making a connection by sharing emotions, wants, or fears. When you make people feel something, it can really change how they think and what they do. For instance, think about a commercial for a sports brand. It might tell a story about an athlete who faced tough challenges and came out on top. This story can make you feel inspired and determined. When you feel that way, you start to like the brand because it gave you those good feelings. That’s how pathos works.

Logos is all about using logic and good reasoning. It means showing information like data, facts, or numbers to make a strong and clear argument. For example, imagine a climate activist who wants to convince people that we need to take care of the environment. They might use facts and statistics about how global temperatures are going up to logically explain why we should take action. This way, they’re using logos to make their point.

Metaphors and Similes

These devices compare one thing to another, often in a way that helps clarify complex ideas or make a message more memorable. A writer might say, “Injustice is a poison that corrupts society,” using a metaphor to liken injustice to poison to emphasize its harmful effects.

This involves deliberate exaggeration to emphasize a point or evoke strong feelings. For instance, a person might say, “I’ve told you a million times.” This hyperbole highlights their frustration or repeated efforts.

Repeating words, phrases, or ideas can reinforce a message and make it more memorable. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech is an excellent example of repetition. The phrase “I have a dream” is reiterated multiple times throughout the speech, powerfully underscoring his vision for equality and justice. Each repetition of this phrase reinforces his hopeful message and leaves a lasting impact on the audience

Identifying Rhetorical Devices in a Text

Recognizing rhetorical devices in text is an essential reading skill that deepens your understanding of how authors convey meaning and persuade their audience. Here’s how you can sharpen your ability to identify these devices as you read:

1. Familiarize Yourself with Common Devices

Start by building a strong foundation. Understand the definitions, purposes, and effects of common rhetorical devices like ethos, pathos, logos, metaphors, hyperbole, and repetition. Knowing what each device looks like and how it typically operates in text will prepare you to spot them more easily.

- Practice Tip: Create a reference chart of devices with definitions and examples. Refer to this chart as you read, and try to match passages with the relevant device. You can also refer to this handy list for a great starting point!

2. Read Actively and Critically

Engage with the text on a deeper level. As you read, be mindful of the author’s word choice, sentence structure, and the overall tone. Ask yourself why the author might have chosen a particular word or phrase and what effect it creates.

- Practice Tip: Highlight or note down sentences or passages where you suspect a rhetorical device is at play. Then, analyze why you think a device is used and what it’s achieving.

3. Look for Patterns and Anomalies

Rhetorical devices often manifest as patterns in the text. Repetition of words, phrases, or ideas; patterns in imagery or metaphors; or even a sudden change in tone or style can all be clues. Conversely, anomalies or deviations from the norm can also signal rhetorical emphasis.

- Practice Tip : As you read, mark recurring themes or language patterns. Consider how these repetitions or anomalies contribute to the text’s persuasive or emotional impact.

4. Consider the Context

Every text exists within a specific context that influences its content and style. Understand the historical, cultural, and personal background of the text. Consider the intended audience and the author’s purpose. This context can provide valuable clues about why certain rhetorical devices are used.

- Practice Tip: Before diving into a text, do a quick research on its background. As you read, keep the context in mind and think about how it might shape the choice of rhetorical devices.

5. Analyze the Structure

The organization of a text can reveal a lot about its rhetorical strategies. Look at the structure of arguments, the progression of ideas, and the placement of particularly persuasive or emotional sections.

- Practice Tip: Create an outline of the text’s structure as you read. Note where key devices appear and how they contribute to the overall argument or message.

By focusing on these specific reading strategies, you’ll become more adept at noticing and understanding the subtle ways authors use rhetorical devices to enhance their messages. Remember, like any skill, identifying rhetorical devices improves with regular practice and thoughtful engagement with a wide range of texts.

Analyzing the Effectiveness of Rhetorical Devices

After you’ve identified rhetorical devices in a text, the next step is to analyze their effectiveness. This involves understanding not just how these devices are used, but why they’re used, and what impact they have on the audience. Here’s how you can approach this analysis:

1. Assess the Context

Understanding when and where a piece of writing was created is key to knowing why the author used certain words or phrases. Think about the time period and the place it comes from. Also, consider who the author was speaking to and what was going on at that time. These details can help you understand why the writer chose to use certain language and how well it worked.

2. Evaluate the Purpose

Next, ask yourself what the writer wanted to achieve. Did they want to convince the readers, give them information, entertain them, or inspire them? Writers use different ways of speaking to reach their goals. By figuring out the writer’s main goal, you can better judge if they used the right approach and how effective it was.

3. Consider the Audience’s Reaction

4. check how the rhetorical devices fit in.

See how well the rhetorical devices fit into the writing. Do they blend in smoothly, or do they stick out awkwardly? When used well, these tools should make the writing better and clearer. If they don’t fit well, they might make the writing hard to understand or take away from the main point.

5. Think About Right and Wrong

Think about whether the language tools are used in a good and honest way. Are they used to share the truth and respect the readers, or are they used to trick or mislead them? Using these tools in the right way can make the writer seem more believable and trustworthy. But using them in the wrong way can make people doubt what the writer is saying.

6. Compare Other Texts

To put your analysis into perspective, compare the use of rhetorical devices in the text with their use in other well-known works. How are the strategies different? What makes some more effective than others? This comparative approach can deepen your understanding of rhetorical effectiveness.

7. Reflect on Personal Impact

Finally, think about your own reaction to the text. Were you persuaded, moved, or inspired? Your personal response can be a powerful indicator of the rhetorical devices’ effectiveness

By closely looking at these parts, you’ll learn more about how language tools work and what makes them good or not so good. This skill is useful for school and helps you think more about the different ways people talk and write in everyday life.

Analyzing Rhetorical Devices in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail ” by Martin Luther King, Jr

Analyzing rhetorical devices isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a way to deepen your understanding of influential texts and the strategies that make them powerful. A prime example for this kind of analysis is Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” an important text in the Civil Rights movement. Here’s how you can use this letter to practice your reading skills through rhetorical analysis:

Before you read “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” know the background. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote it in 1963 while he was in jail in Birmingham, Alabama. He was there because he was protesting for equal rights. He wrote the letter to respond to some church leaders who didn’t agree with his protests. Understanding this time and why King was in jail helps you see why he wrote what he did.

King wrote the letter to explain why he believed protesting against unfair laws was right and needed. He wanted to convince his critics and others that not fighting against racism was wrong. Knowing what King wanted to achieve with his letter helps you understand why he chose certain words and ways of explaining his thoughts.

Think about how the people King was writing to, the eight church leaders, and others might have felt when they read his letter. King used religious references and talked about moral issues because he thought these points would really hit home for them. Also, think about how others who were for or against equal rights at the time might have reacted to his words

4. Check How the Rhetorical Devices Fit It

Look at how King uses rhetorical devices in his letter.

Ethos (Credibility/Trustworthiness):

- King’s Role and Experience: King tells readers he’s the leader of an important group that works all over the south. He says, “I am the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.” This makes people see him as a leader with a lot of experience.

- Moral Standing: King talks about his strong beliefs and compares himself to people from the Bible to show he’s doing the right thing. He mentions famous religious figures, making people see him as someone with good values. He mentions, “Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their ‘thus saith the Lord’ far beyond the boundaries of their home towns…” highlighting the comparison between him and other religious figures the clergy would have respected.

Pathos (Emotional Appeal)

- The Pain and Struggle: King vividly describes the experiences of African Americans, evoking emotions to make the readers feel the urgency and pain of the racial situation.He talks about families being hurt and people living in fear.

- Hope and Despair: He contrasts the hope of the civil rights movement with the despair caused by racism, creating an emotional rollercoaster that compels the audience to empathize and act. He expresses, “We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people.”

Logos (Logical Appeal)

- Reasons for Protests: King explains clearly why they need to protest. He says they’re protesting because promises are broken and people are treated unfairly. He makes it clear that they have to stand up for what’s right.

- Counterarguments: He thinks about what his critics say and answers them. For example, when people call him an “outsider,” he responds by saying, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” This phrase emphasizes his right to be involved in these matters because injustice is a universal issue that needs to be addressed.

- Phrasal Repetition: King repeats certain phrases to make his message stronger. For instance, he starts many sentences with “When you” to show how often immoral actions happen to the African American community. This helps make his point clearer and stick in the reader’s mind.

- Anaphora (Repeating the start of sentences): He often starts sentences with the same words, like “I am here because,” to stress his reasons for being in Birmingham. This makes his reasons stand out and easier to remember.

Reflect on how King uses his words in a fair and honest way. He makes strong points about what’s morally right and wrong but does it respectfully. He’s not trying to trick anyone; he’s trying to show them the truth and get them to think differently about the situation.

6. Compare with Other Texts

Look at King’s letter and compare it with other important writings or speeches from the same time or even other works by King himself. Notice how they are similar or different in the way they try to convince and inspire people. This can help you understand more about how words can be used to make a big impact.

Lastly, think about how the letter makes you feel. Are there certain parts that stand out to you or make you feel strongly? Thinking about your own reactions can help you see just how powerful King’s words are and why they are still remembered and talked about today.

By looking closely at “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” you not only improve your ability to notice and analyze the rhetorical devices King uses but also grow to appreciate this powerful and important letter in a new way. This study will help you become a better reader who understands and thinks more about what you read, seeing beyond just the words on the page.

Practice Makes Perfect

Like any skill, proficiency in identifying and analyzing rhetorical devices comes with practice. It’s one thing to understand these strategies in theory, but it’s another to apply this knowledge actively and see it in action. That’s why we encourage you to take what you’ve learned here and put it into practice.

Albert provides many opportunities for you to practice these rhetorical analysis skills. Whether you want to improve before the AP® Language and Composition Exam or gain a deeper understanding of how authors used rhetoric in essential historic texts , Albert has you covered! Every question includes a detailed explanation of the correct answer and the distractors so you can learn as you go.

Remember, the more you practice, the more intuitive and insightful your rhetorical analysis will become. Rhetorical devices are not just academic concepts; they are practical tools that can enhance your reading, writing, and critical thinking skills. So, take advantage of Albert’s resources, and start practicing today. With dedication and practice, you’ll soon find yourself mastering the art of persuasion and the nuances of effective communication.

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.