Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Nahuatl and spanish in contact: language practices in mexico.

1. Introduction

2. language shift and maintenance, 3. indigenous language use, studies on nahuatl language use, 4. methodology, 4.1. research question, 4.2. participants, 4.3. instrument, 4.4. data analysis, 5.2. community, 5.3. emotions, 6. discussion, 7. conclusions, 8. implications for language planning, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Austin, Peter K., and Julia Sallabank. 2011. Introduction. In The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages . Edited by Peter K. Austin and Julia Sallabank. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barreña, Andoni, Esti Amorrortu, Ane Ortega, Belen Uranga, Esti Izagirre, and Itziar Idiazabal. 2007. Does the number of speakers of a language determine its fate? International Journal of the Sociology of Language 186: 125–39. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Brenzinger, Matthias, Akira Yamamoto, Noriko Aikawa, Dmitri Koundiouba, Anahit Minasyan, Arienne Dwyer, Colette Grinevald, Michael Krauss, Osahito Miyaoka, Osamu Sakiyama, and et al. 2003. Language Vitality and Endangerment . Paris: UNESCO Expert Meeting on Safeguarding Endangered Languages. [ Google Scholar ]

- Caldas, Stephen J. 2012. Language policy in the family. In The Cambridge Handbook of Language Policy . Edited by Bernard Spolsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 351–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chambers, Natalie Alexandra. 2014. “They All Talk Okanagan and I Know What They Are Saying.” Language Nests in the Early Years: Insights, Challenges and Promising Practices. Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi, Jinny K. 2005. Bilingualism in Paraguay: Forty years after Rubin’s study. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 26: 233–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Christopher, Suzanne, Robin Saha, Paul Lachapelle, Derek Jennings, Yoshiko Colclough, Clarice Cooper, Crescentia Cummins, Margaret J. Eggers, Kris Fourstar, Kari Harris, and et al. 2011. Applying Indigenous community-based participatory research principles to partnership development in health disparities research. Family & Community Health 34: 246–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference Forlanguages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crystal, David. 2000. Language Death . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks, and Richard Dauenhauer. 1998. Technical, emotional and ideological issues in reversing language shift: Examples from Southeast Alaska. In Endangered Languages, Current Issues and Future Prospects . Edited by Lenore A. Grenoble and Lindsay J. Whaley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 57–98. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dawson, Alexander S. 2012. Histories and memories of the Indian boarding schools in Mexico, Canada, and the United States. Latin American Perspectives 39: 80–99. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Delaine, Brent. 2010. Talk medicine: Envisioning the effects of Aboriginal language revitalization in Manitoba schools. First Nations Perspectives 3: 65–88. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2010. Emotions in Multiple Languages . New York: Palgrave Macmillian. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2021. Ethnologue: Languages of the World , 24th ed. Dallas: SIL International. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 1990. XI Censo General de Población y Vivienda 1990. Tabulados básicos . Mexico City: INEGI. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 1995. I Conteo de Población y Vivienda 1995. Tabulados básicos . Mexico City: INEGI. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2000. XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000. Tabulados básicos . Mexico City: INEGI. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2005. II Conteo de Población y Vivienda 2005. Tabulados básicos . Mexico City: INEGI. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2010a. Volumen y crecimiento. Población Total Según Tamaño de Localidad para cada Entidad Federativa, 2010 . Mexico City: INEGI. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2010b. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. Tabulados del Cuestionario Básico . Mexico City: INEGI. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2015. Encuesta Intercensal 2015 . Mexico City: INEGI. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2018. Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica 2018 . Mexico City: INEGI. [ Google Scholar ]

- El Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI). 2012. Lenguas Indígenas Nacionales en Riesgo de Desaparición: Variantes Lingüísticas por Grado de Riesgo. 2000 . Mexico City: INALI. [ Google Scholar ]

- Endangered Languages Project. 2012. Catalogue of Endangered Languages . Hawai’i: Endangered Languages Project. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fishman, Joshua A. 1991. Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages . Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gal, Susan. 1979. Language Shift: Social Determinants of Linguistic Change in Bilingual Austria . San Francisco: Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garrido Cruz, Guillermo. 2015. Las Lenguas Indígenas de la Huasteca Poblana: Historia, Contacto y Vitalidad . Puebla: Programa de Desarrollo Cultural de la Huasteca. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gomashie, Grace A. 2019. Kanien’keha/Mohawk Indigenous language revitalisation efforts in Canada. McGill Journal of Education 54: 151–71. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Gomashie, Grace A. 2020a. Bilingual youth’s language choices and attitudes towards Nahuatl in Santiago Tlaxco, Mexico. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gomashie, Grace A. 2020b. The language vitality of Nahuatl in Santiago Tlaxco, Mexico. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, Ontario, ON, Canada. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gomashie, Grace A., and Roland Terborg. 2021. Nahuatl, selected vitality indicators and scales of vitality in an Indigenous language community in Mexico. Open Linguistics 7: 166–80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gómez-Retana, Denisse, Roland Terborg, and Samantha Estévez. 2019. En busca de los factores particulares de desplazamiento de lenguas indígenas de México. Comparación de dos casos: La comunidad náhuatl Cuacuila y la comunidad mazahua. LIAMES: Línguas Indígenas Americanas 19: 1–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haboud, Marleen, Rosaleen Howard, Josep Cru, and Jane Freeland. 2016. Linguistic Human Rights and Language Revitalization in Latin America and the Caribbean. In Indigenous Language Revitalization in the Americas . Edited by Serafín M. Coronel-Molina and Teresa L. McCarty. New York: Routledge, pp. 201–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hale, Ken, Michael Krauss, Lucille J. Watahomigie, Akira Y. Yamamoto, Collete Craig, LaVerne Masayesva Jeanne, and Nora C. England. 1992. Endangered languages. Language 68: 1–42. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hansen, Magnus. 2016. The difference language makes: The life-history of Nahuatl in two Mexican families. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 26: 81–97. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Hansen, Magnus Pharao. 2010. Nahuatl among Jehovah’s Witnesses of Hueyapan Morelos: A case of spontaneous revitalization. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 203: 125–37. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Heller, Monica. 2003. Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7: 473–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hill, Jane H. 1998. Don Francisco Marquez survives: A meditation on monolingualism. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 132: 167–82. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hill, Jane H., and Kenneth C. Hill. 1986. Speaking Mexicano: Dynamics of Syncretic Language in Central Mexico . Arizona: University of Arizona Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hornberger, Nancy H. 1988a. Bilingual education and language maintenance: A southern Peruvian Quechua case . Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hornberger, Nancy H. 1988b. Language ideology in Quechua communities of Puno, Peru. Anthropological Linguistics 30: 214–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jenni, Barbara, Adar Anisman, Onowa McIvor, and Peter Jacobs. 2017. An exploration of the effects of mentor–apprentice programs on mentors and apprentices’ wellbeing. International Journal of Indigenous Health 12: 25–42. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- King, Kendall A. 2000. Language ideologies and heritage language education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 3: 167–84. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- King, Kendall A., Lyn Fogle, and Aubrey Logan-Terry. 2008. Family language policy. Language and Linguistics Compass 2: 907–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Knockwood, Isabelle. 2015. Out of the Depths: The Experiences of Mi’kmaw Children at the Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia , 4th ed. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kulick, Don. 1992. Language Shift and Cultural Reproduction: Socialization, Self and Syncretism in a Papua New Guinean Village . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Jason Rothman. 2018. Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 564–82. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- La Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas (CDI). 2016. Indicadores Socioeconómicos de los Pueblos Indígenas de México, 2015 . Mexico City: CDI. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lam, Yvonne. 2009. The straw that broke the language’s back: Language shift in the Upper Necaxa Valley of Mexico. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 195: 219–33. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- LaVeaux, Deborah, and Suzanne Christopher. 2009. Contextualizing CBPR: Key principles of CBPR meet the indigenous research context. Pimatisiwin 7: 1–25. [ Google Scholar ] [ PubMed ]

- Lewis, M. Paul, and Gary F. Simons. 2010. Assessing endangerment: Expanding Fishman’s GIDS. Revue Roumaine de Linguistique (RRL) 55: 103–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- McCarty, Teresa L., Mary Eunice Romero, and Ofelia Zepeda. 2006. Reclaiming the gift: Indigenous youth counter-narratives on Native language loss and revitalization. American Indian Quarterly 30: 28–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- McIvor, Onowa, and Adar Anisman. 2018. Keeping our languages alive: Strategies for Indigenous language revitalization and maintenance. In Handbook of Cultural Security . Edited by Yasushi Watanabe. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, pp. 90–109. [ Google Scholar ]

- McIvor, Onowa. 2015. Adult Indigenous language learning in western Canada: What is holding us back? In Living Our Languages . Edited by Kathryn A. Michel, Patrick D. Walton, Emma Bourassa and Jack Miller. New York: Linus Learning, pp. 37–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Messing, Jacqueline. 2003. Ideological Multiplicity in Discourse: Language Shift and Bilingual Schooling in Mexico. Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Arizona. [ Google Scholar ]

- Messing, Jacqueline. 2007. Multiple ideologies and competing discourses: Language shift in Tlaxcala, Mexico. Language in Society 36: 555–77. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Messing, Jacqueline. 2009. Ambivalence and ideology among Mexicano youth in Tlaxcala, Mexico. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education 8: 350–64. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mojica Lagunas, R. 2019. Language keyholders for Mexicano: The case of an intergenerational community in Coatepec de los Coasteles, Mexico. In A World of Indigenous Languages: Policies, Pedagogies and Prospects for Language Reclamation . Edited by Teresa L. McCarty, Sheilah E. Nicholas and Gillian Wigglesworth. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 214–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Congress of American Indians. 2016. The National Congress of American Indians Resolution #PHX-16-013: Executive Order on Native Language Revitalization . Phoenix: National Congress of American Indians. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nettle, Daniel, and Suzanne Romaine. 2000. Vanishing Voices . Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Norris, Mary Jane. 2004. From generation to generation: Survival and maintenance of Canada’s Aboriginal languages, within families, communities and cities. TESL Canada Journal 21: 1–16. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Olko, Justyna, and John Sullivan. 2014. An integral approach to Nahuatl language revitalization. Zeszyty Łużyckie 48: 191–214. [ Google Scholar ]

- Olko, Justyna, and John Sullivan. 2016. Bridging gaps and empowering speakers: An inclusive, partnership-based approach to Nahuatl research and revitalization. In Integral Strategies for Language Revitalization . Edited by Justyna Olko, Tomasz Wicherkiewicz and Robert Borges. Warsaw: Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, University of Warsaw & Authors, pp. 345–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pérez Alvarado, Lillyan Arely, Veronica Aideé Ramos, and Roland Terborg. 2018. Diferentes etapas en el desplazamiento de una lengua indígena: Estudio comparativo entre las comunidades de Jesús María, Nayarit y San Juan Juquila Mixes, Oaxaca. LIAMES: Línguas Indígenas Americanas 18: 367–80. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pérez Báez, Gabriela. 2013. Family language policy, transnationalism, and the diaspora community of San Lucas Quiaviní of Oaxaca, Mexico. Language Policy 12: 27–45. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ritchie, Stephen D., Mary Jo Wabanoc, Jackson Beardy, Jeffrey Currane, Aaron Orkin, David VanderBurgh, and Nancy L. Young. 2013. Community-based participatory research with Indigenous communities: The proximity paradox. Health & Place 24: 183–89. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rubin, Joan. 1968. National Bilingualism in Paraguay . The Hague: Moulton. [ Google Scholar ]

- Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove. 1988. Multilingualism and the education of minority children. In Minority Education: From Shame to Struggle . Edited by Tove Skutnabb-Kangas and Jim Cummins. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 9–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove. 2015. Linguicism. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics . Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Smala, Simone, Jesus Bergas Paz, and Bob Lingard. 2013. Languages, cultural capital and school choice: Distinction and second-language immersion programmes. British Journal of the Sociology of Education 34: 373–91. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Statistics Canada. 2017. The Aboriginal Languages of First Nations People, Métis and Inuit . Ottawa: Statistics Canada. [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor, Shelley K. 2014. From "monolingual" multilingual classrooms to "multilingual" multilingual classrooms: Managing cultural and linguistic diversity in the Nepali educational system. In Managing Diversity in Education: Key Issues and Some Responses . Edited by David Little, Constant Leung and Piet Van Avermaet. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 259–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- Terborg, Roland, and Laura García Landa. 2011. Muerte y Vitalidad de las Lenguas Indígenas y las Presiones Sobre sus Hablantes . Ciudad de México: CELE/UNAM. [ Google Scholar ]

- Terborg, Roland, and Laura García Landa. 2013. The Ecology of pressures: Towards a tool to analyze the complex process of language shift and maintenance. In Complexity Perspectives on Language, Communication and Society . Edited by Àngels Massip-Bonet and Albert Bastardas-Boada. Berlin: Springer, pp. 219–39. [ Google Scholar ]

- Trujillo Tamez, A. I., R. Terborg, and V. Velázquez. 2007. La vitalidad de las lenguas indígenas en México: El caso de las lenguas otomí, matlazinca, atzinca y mixe. In La Romania en Interacción . Edited by L. Morgenthaler García and M. Schrader-Kniffki. Madrid: Iberoamericana Vervuert, pp. 611–29. [ Google Scholar ]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada . Ottawa: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. [ Google Scholar ]

- United Nations. 2007. United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples . New York: United Nations. [ Google Scholar ]

- United States Commission on Civil Rights. 2018. Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans . Washington, DC: United States Commission on Civil Rights. [ Google Scholar ]

- Valiñas, Leopoldo. 2019. Diccionario Enciclopédico de las Lenguas Indígenas de México . Ciudad de México: Academia Mexicana de la Lengua/Fundación para las Letras Mexicanas/Secretaria de Cultura. [ Google Scholar ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Domains | Locations | Institutions | Persons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | home: own, of family, of friends | family; social networks | spouses; offspring (preschoolers, children, adolescents, adults); parents, grandparents; siblings; other relatives; friends; neighbours |

| Public | public spaces: street, market, clinics, place of worship | community; public health; denominations | residents (preschoolers, children, adolescents, adults, elderly); merchants; doctors; nurses; curandero; priests; pastors; congregation; strangers |

| Occupational | workplaces: farms, stores, shops offices | small and medium-sized enterprises; family-owned businesses | employers; employees; workmates |

| Educational | schools | schools | teachers |

| Interlocutor | Age Group | Spanish | Nahuatl | Both | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Spouse | Group A | 7 (19.4%) | 13 (36.1%) | 16 (44.4%) | 36 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (7.4%) | 25 (92.6%) | 0 (0%) | 27 (100%) | |

| 2. Spouse in front children | Group A | 7 (21.2%) | 12 (36.4%) | 14 (42.4%) | 33 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (7.4%) | 22 (81.5%) | 3 (11.1%) | 27 (100%) | |

| 3. Children (0–5) | Group A | 11 (35.5%) | 3 (9.7%) | 17 (54.8%) | 31 (100%) |

| Group B | 5 (26.3%) | 11 (57.9%) | 3 (15.8%) | 19 (100%) | |

| 4. Children (6–12) | Group A | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (13.0%) | 17 (73.9%) | 23 (100%) |

| Group B | 5 (27.8%) | 10 (55.6%) | 3 (16.7%) | 18 (100%) | |

| 5. Children (13–18) | Group A | 2 (12.5%) | 3 (18.8%) | 11 (68.8%) | 16 (100%) |

| Group B | 5 (22.7%) | 14 (63.6%) | 3 (13.6%) | 22 (100%) | |

| 6. Adult children | Group A | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 7 (77.8%) | 9 (100%) |

| Group B | 3 (13.0%) | 16 (69.6%) | 4 (17.4%) | 23 (100%) | |

| 7. Parents | Group A | 5 (12.2%) | 28 (68.3%) | 8 (19.5%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 1 (4.0%) | 22 (88.0%) | 2 (8.0%) | 25 (100%) | |

| 8. Grandparents | Group A | 3 (9.4%) | 24 (75.0%) | 5 (15.6%) | 32 (100%) |

| Group B | 0 (0%) | 23 (95.8%) | 1 (4.2%) | 24 (100%) | |

| 9. Siblings | Group A | 7 (17.1%) | 23 (56.1%) | 11 (26.8%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (5.9%) | 29 (85.3%) | 3 (8.8%) | 34 (100%) | |

| 10. Other relatives | Group A | 0 (0%) | 20 (47.6%) | 22 (52.4%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (5.3%) | 26 (68.4%) | 10 (26.3%) | 38 (100%) |

| Interlocutor | Age Group | Spanish | Nahuatl | Both | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Friends in the neighbourhood | Group A | 1 (2.4%) | 26 (61.9%) | 15 (35.7%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 0 (0.0%) | 28 (73.7%) | 10 (26.3%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 12. Neighbours | Group A | 1 (2.4%) | 28 (68.3%) | 12 (29.3%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 1 (2.7%) | 30 (81.1%) | 6 (16.2%) | 37 (100%) | |

| 13. Work colleagues | Group A | 3 (8.1%) | 19 (51.4%) | 15 (40.5%) | 37 (100%) |

| Group B | 1 (3.3%) | 24 (80.0%) | 5 (16.7%) | 30 (100%) | |

| 14. Employees | Group A | 2 (14.3%) | 8 (57.1%) | 4 (28.6%) | 14 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (12.5% | 13 (81.3%) | 1 (6.3%) | 16 (100%) | |

| 15. Employer | Group A | 5 (23.8%) | 11 (52.4%) | 5 (23.8%) | 21 (100%) |

| Group B | 3 (16.7%) | 14 (77.8%) | 1 (5.6%) | 18 (100%) | |

| 16. Schoolteacher | Group A | 35 (87.5%) | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (5.0%) | 40 (100%) |

| Group B | 23 (76.7%) | 6 (20.0%) | 1 (3.3%) | 30 (100%) | |

| 17. Doctor | Group A | 40 (95.2%) | 2 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 27 (71.1%) | 10 (26.3%) | 1 (2.6%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 18. Nurse | Group A | 39 (95.1%) | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (2.4%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 27 (71.1%) | 10 (26.3%) | 1 (2.6%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 19. Curandero (witch doctor) | Group A | 12 (31.6%) | 14 (36.8%) | 12 (31.6%) | 38 (100%) |

| Group B | 9 (26.5%) | 15 (44.1%) | 10 (29.4%) | 34 (100%) | |

| 20. Priest or Pastor | Group A | 20 (48.8%) | 15 (36.6%) | 6 (14.6%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 13 (36.1%) | 20 (55.6%) | 3 (8.3%) | 36 (100%) | |

| 21. Children (0–5) | Group A | 9 (22.0%) | 8 (19.5%) | 24 (58.5%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 3 (7.9%) | 21 (55.3%) | 14 (36.8%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 22. Children (6–12) | Group A | 5 (12.5%) | 10 (25.0%) | 25 (62.5%) | 40 (100%) |

| Group B | 4 (10.5%) | 20 (52.6%) | 14 (36.8%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 23. Adolescents (13–17) | Group A | 4 (9.8%) | 11 (26.8%) | 26 (63.4%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 0 (0%) | 22 (57.9%) | 16 (42.1%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 24. Adults (18–60) | Group A | 0 (0%) | 21 (52.5%) | 19 (47.5%) | 40 (100%) |

| Group B | 1 (2.6%) | 27 (71.1%) | 10 (26.3%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 25. Elderly (over 60 years | Group A | 2 (5.0%) | 30 (75.0%) | 8 (20.0%) | 40 (100%) |

| Group B | 0 (0.0%) | 36 (94.7%) | 2 (5.3%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 26. Strangers | Group A | 18 (45.0%) | 6 (15.0%) | 16 (40.0%) | 40 (100%) |

| Group B | 17 (44.7%) | 11 (28.9%) | 10 (26.3%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 27. At market (merchants) | Group A | 5 (11.9%) | 7 (16.7%) | 30 (71.4%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 1 (2.6%) | 6 (15.8%) | 31 (81.6%) | 38 (100%) |

| Emotion | Age Group | Spanish | Nahuatl | Both | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28. When telling a joke | Group A | 10 (23.8%) | 11 (26.2%) | 21 (50.0%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (5.3%) | 29 (76.3%) | 7 (18.4%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 29. When rendering insults | Group A | 8 (19.5%) | 12 (29.3%) | 21 (51.2%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 1 (2.6%) | 28 (73.7%) | 9 (23.7%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 30. When cursing | Group A | 6 (14.6%) | 10 (24.4%) | 25 (61.0%) | 41 (100%) |

| Group B | 0 (0%) | 30 (78.9%) | 8 (21.1%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 31. When saying intimate things | Group A | 8 (19.0%) | 13 (31.0%) | 21 (50.0%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (5.3%) | 29 (76.3%) | 7 (18.4%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 32. When convincing someone | Group A | 5 (12.5%) | 10 (25.0%) | 25 (62.5%) | 40 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (5.4%) | 26 (70.3%) | 9 (24.3%) | 37 (100%) | |

| 33. When angry | Group A | 7 (16.7%) | 13 (31.0%) | 22 (52.4%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (5.3%) | 31 (81.6%) | 5 (13.2%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 34. When afraid | Group A | 6 (14.3%) | 11 (26.2%) | 25 (59.5%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (5.4%) | 29 (78.4%) | 6 (16.2%) | 37 (100%) | |

| 35. When happy | Group A | 9 (21.4%) | 9 (21.4%) | 24 (57.1%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 4 (10.5%) | 28 (73.7%) | 6 (15.8%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 36. When sad | Group A | 8 (19.0%) | 12 (28.6%) | 22 (52.4%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 2 (5.3%) | 27 (71.1%) | 9 (23.7%) | 38 (100%) | |

| 37. When remorseful | Group A | 8 (19.0%) | 13 (31.0%) | 21 (50.0%) | 42 (100%) |

| Group B | 1 (2.6%) | 30 (78.9%) | 7 (18.4%) | 38 (100%) |

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Gomashie, G.A. Nahuatl and Spanish in Contact: Language Practices in Mexico. Languages 2021 , 6 , 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030135

Gomashie GA. Nahuatl and Spanish in Contact: Language Practices in Mexico. Languages . 2021; 6(3):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030135

Gomashie, Grace A. 2021. "Nahuatl and Spanish in Contact: Language Practices in Mexico" Languages 6, no. 3: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030135

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Kathryn A. Martin Library

- Research & Collections

- News & Events

Spanish Research Guide

- Find Articles and Databases

- Find Books and Films

- Cite Sources

Humanities & Fine Arts Librarian

Introduction

This guide serves as an introduction to the Spanish resources provided by the Kathryn A. Martin Library. However, this guide is by no means a complete list of resources. To see all the available digital resources in World Languages and Cultures, visit the A-Z databases list:

- World Languages & Cultures Subject Page

If you have questions, contact your librarian!

Databases for Spanish

These databases and journals contain articles relevant to the study of the Spanish language, as well as Spanish and Latin American politics and culture. In addition, they may contain articles related to a wide range of humanities and social science disciplines.

- List of Spanish and Latin American journals in print and electronic format The journals linked here are either in Spanish or contain articles concerning Spanish-speaking countries and cultures across the globe.

- Surrealist Journals from Argentina, Chile & Spain (1928-67)

Find Articles

After clicking the UMD Find It icon, if the article is not available online or in the library, UMD Library Catalog will say "Check availability":

- If you are not already logged into your library account, click Sign in to request

- Click Interlibrary Loan and log in using your UMD credentials.

- Choose "date needed by" and your department.

- Submit your request.

If you need assistance contact a librarian .

Do you have more questions about FindIt? Check out this video from UMN Libraries on the subject

- Next: Find Books and Films >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 12:34 PM

- URL: https://libguides.d.umn.edu/spanish

- Give to the Library

- Directories

- Topics, Keywords, & Search Tips

- Full List of Related Databases

- Books & Theses

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias & Overviews

- Spanish-language Films & TV

- Spanish-language News

- Digital Libraries & Collections

- Literary & Critical Theory This link opens in a new window

- Learn Spanish This link opens in a new window

- Ladino Language Resources

- Open Educational Resources for Language Learning: Spanish

- Collection Guidelines: Spanish & Portuguese Studies This link opens in a new window

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

- Spanish Studies

- Find Articles & E-Journals

Spanish Studies: Find Articles & E-Journals

Uw libraries search.

Advanced Search | FAQ | Known Issues

Spanish Language and Literature: Search topic by keyword

- Dialnet Index of Spanish academic journals, includes some full text. It is particularly useful for subjects related to Spain. Coverage is 1980 to the present.

View a complete list of databases for Spanish and Portuguese Languages & Literatures.

History and Social Sciences Databases: Search topic by keyword

- SciELO Access to scholarly literature in sciences, social sciences, arts and humanities published in leading open access journals from Latin America, Portugal, and Spain.

Search Google Scholar

Popular E-Journal Packages

Google scholar.

- Google Académico Spanish Google Scholar.

- Google Scholar How to: Connect Google Scholar to UW Holdings.

Journal Search

Journal Search Search or browse journal titles held at UW. Can't find it? Request it through Interlibrary Loan .

What is a scholarly article?

- << Previous: Topics, Keywords, & Search Tips

- Next: Full List of Related Databases >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2024 12:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/spanish

Libraries | Research Guides

* spanish & portuguese.

- Getting Started

- Find Books and Literature

Searching for Scholarly Articles

Finding scholarly journal articles in spanish/portuguese, scholarly articles on language and literatures.

- Find News, Music, Film, and Media

- Learn Spanish and Portuguese

- Latin American Jewish Authors & Filmmakers

- Printemps Littéraire Brésilien: Spring 2018

- Beyond Anthropophagy: Fall 2017

There are several places to find Spanish- or Portuguese-language scholarly articles. Northwestern University Libraries subscribes to several large databases which may include English-language scholarship on Spanish- or Portuguese-speaking countries. Check "Getting Started" Tab on this Research Guide, and/or the Research Guides for Anthropology , English , History , Latino Studies , Political Science , Sociology , and/or JSTOR for lists of general disciplinary databases for each subject. Below are more specialized resources in Spanish and Portuguese, on topics relevant to African, Caribbean, Iberian, or Latin American Studies.

- HAPI Online: Hispanic American Periodicals Index This link opens in a new window Provides citations to articles about Central and South America, Mexico, the Caribbean basin, the U.S.-Mexico border, and Hispanics in the U.S. Covers 1970-present.

- HLAS: Handbook of Latin American Studies This link opens in a new window The Handbook is a bibliography on Latin America consisting of works selected and annotated by scholars. Edited by the Hispanic Division of the Library of Congress, the multidisciplinary Handbook alternates annually between the social sciences and the humanities. Each year, more than 130 academics from around the world choose over 5,000 works for inclusion in the Handbook. Continuously published since 1936, the Handbook offers Latin Americanists an essential guide to available resources.

- Dialnet Provides access to tables of contents of more than 3,000 journals in the humanities, social sciences and sciences published in Spain and Latin America. more... less... Also, provides access to the full text of some Spanish doctoral dissertations as well as the full text of working papers from some research centers in Spain and Latin America.

- Bases de datos bibliográficas del CSIC Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) produces since 1971 three free access bibliographic databases with references to articles published in mainly Spanish scientific journals.

- Clase and Periodica This link opens in a new window Indexes materials published in Latin America in Spanish, Portuguese, French and English specializing in the social sciences, humanities, and science and technology. Contains information from articles, essays, book reviews, monographs, conference proceedings, technical reports, interviews and brief notes published in journals edited in 24 different countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as from publications that focus on Pan-American issues.

- Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO Single search database for Redalyc, Scielo, LatIndex, RevistALAS, DOAJ, Dialnet, and CLASE, sponsored by el Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales.

- SciELO - Scientific Electronic Library Online This link opens in a new window SciELO - Scientific Electronic Library Online is a model for cooperative electronic publishing of scientific journals on the Internet. Especially conceived to meet the scientific communication needs of developing countries, particularly Latin America and the Caribbean countries. It contains about 500 journals and nearly 150.000 articles published in Latin America, Caribbean countries, Portugal and Spain. Most of the titles are Open Access.

- CLASE CLASE es una base de datos bibliográfica creada en 1975 en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Ofrece alrededor de 350 mil registros bibliográficos de artículos, ensayos, reseñas de libro, revisiones bibliográficas, notas breves, editoriales, biografías, entrevistas, estadísticas y otros documentos publicados en cerca de 1 500 revistas de América Latina y el Caribe, especializadas en ciencias sociales y humanidades.

- DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) Indexes articles appearing in Open Access journals. As of September 2015, from a total of 10,529 Open Access journals registered in DOAJ, approximately 2000 journals are from Latin America and the Caribbean, of which around 1000 journals are from Brazil.

- Latindex Latindex es un sistema de Información sobre las revistas de investigación científica, técnico-profesionales y de divulgación científica y cultural que se editan en los países de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal. La idea de creación de Latindex surgió en 1995 en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) y se convirtió en una red de cooperación regional a partir de 1997.

- REDALYC Maintained by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), this open access online portal includes peer-reviewed and journal articles on the social sciences and humanities from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain, and Portugal.

- MLA International Bibliography This link opens in a new window Compiled by the Modern Language Association, the MLA International Bibliography lists articles and books in the fields of literature, language, and linguistics in the modern languages, as well as folklore, film studies, literary theory & criticism, dramatic arts, and historical aspects of printing and publishing.

- Gale Literature Criticism This link opens in a new window An extensive compilation of literary commentary available representing a range of modern and historical views on authors and their works across regions, eras, and genre.

- Film & Television Literature Index with Full Text This link opens in a new window A comprehensive index covering the entire spectrum of television and film writing and produced for a broad target audience, from film scholars to general viewers. Subject coverage includes: film & television theory, preservation & restoration, writing, production, cinematography, technical aspects, and reviews.

- Hispania The official journal of the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese (AATSP) includes articles on applied linguistics, cultural studies, culture, film, language, linguistics, literary criticism, literature, and pedagogy having to do with Spanish and Portuguese. 1917-present.

- << Previous: Find Books and Literature

- Next: Find News, Music, Film, and Media >>

- Last Updated: Aug 23, 2024 2:01 PM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/spanport

- Search Grant Programs

- Application Review Process

- Manage Your Award

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- Search All Past Awards

- Divisions and Offices

- Professional Development

- Workshops, Resources, & Tools

- Sign Up to Be a Panelist

- Emergency and Disaster Relief

- Equity Action Plan

- States and Jurisdictions

- Featured NEH-Funded Projects

- Humanities Magazine

- Information for Native and Indigenous Communities

- Information for Pacific Islanders

- Search Our Work

- American Tapestry

- Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative

- Humanities Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence

- Pacific Islands Cultural Initiative

- United We Stand: Connecting Through Culture

- A More Perfect Union

- NEH Leadership

- Open Government

- Contact NEH

- Press Releases

- NEH in the News

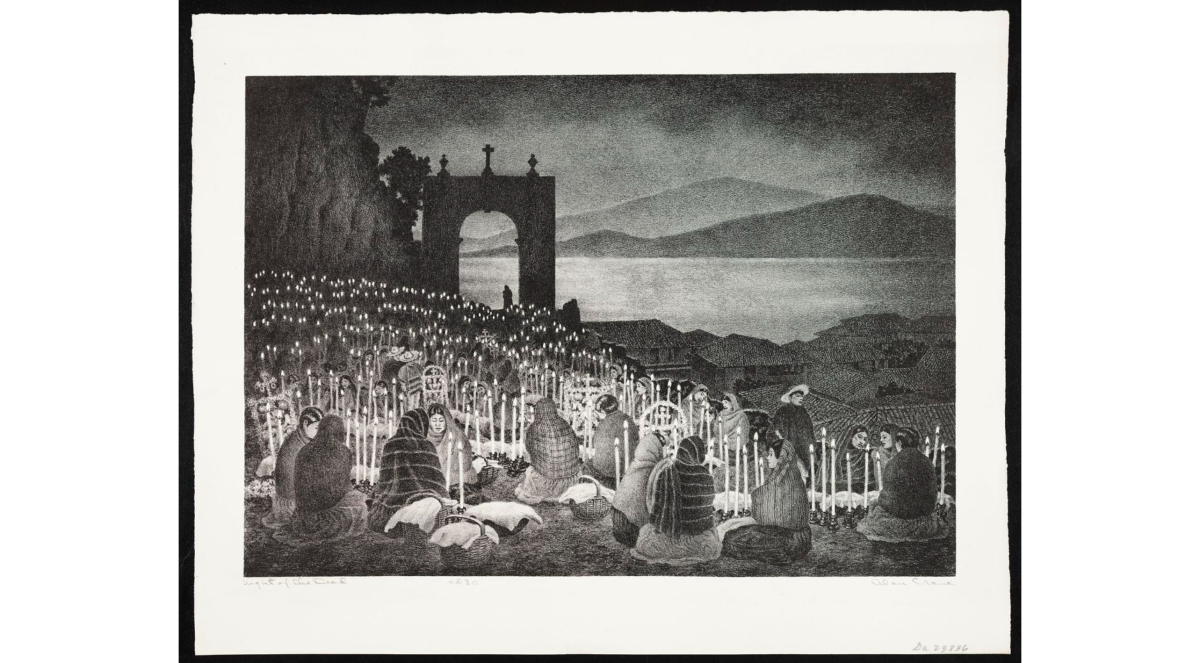

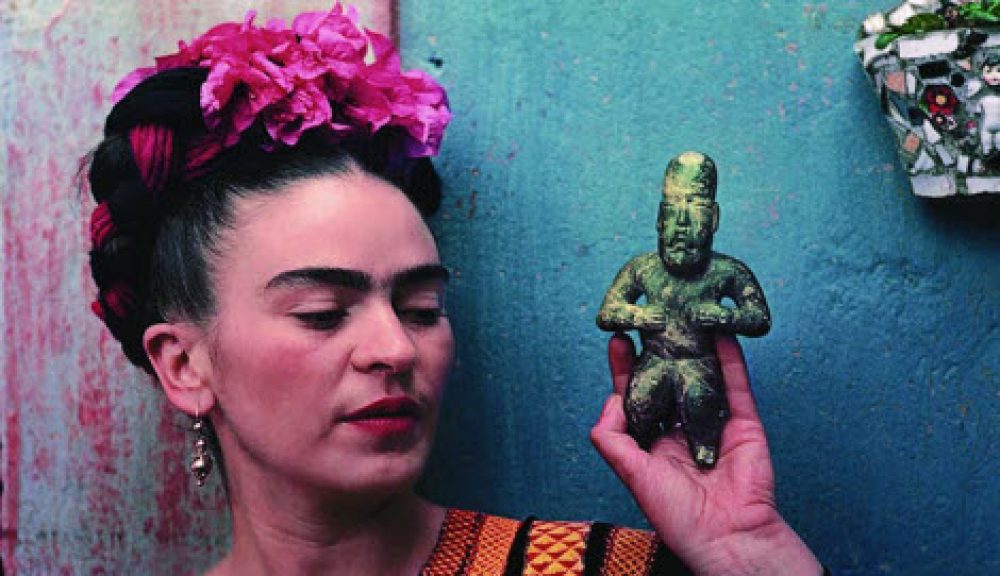

Celebrating Día de los Muertos : Humanities Research on Mexican History, Literature, and Culture

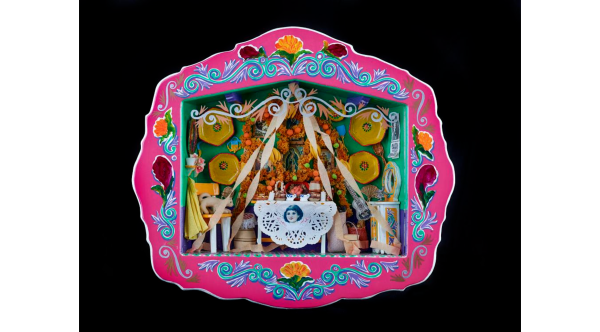

“Dia de los Muertos Altar Scene.”

Gift of Janice and Glenn Hatfield. Available at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

The Day of the Dead (or, in Spanish, Día de los Muertos ) is a commemorative holiday observed annually on November 1 and 2, both in its native Mexico and among Mexican people around the world. On the Day of the Dead, celebrants honor their deceased loved ones by leaving offerings at home altars ( ofrendas ), writing playful poems ( calaveras literarias ), and wearing colorful costumes, often including the holiday’s signature skull masks ( calacas ). Ahead of this year’s festivities, learn about thirteen projects funded by the NEH Division of Research Programs that explore Mexican history, literature, and culture.

Published Books

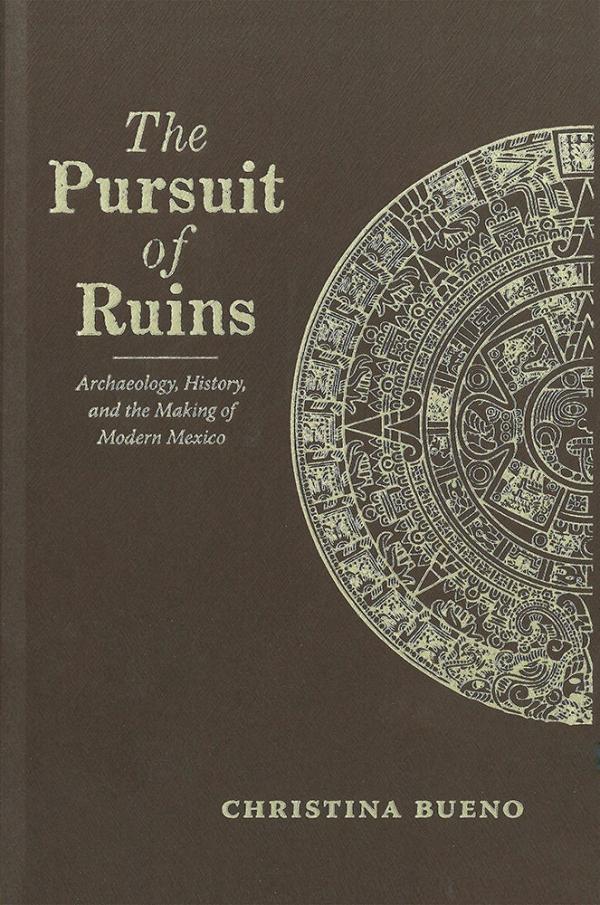

Bueno, Christina. The Pursuit of Ruins: Archaeology, History, and the Making of Modern Mexico (University of New Mexico Press, 2016).

During Porfirio Díaz’s thirty-one years as president in the late nineteenth century, Mexico’s state-sponsored history came to feature indigeneity more prominently, as Díaz sought to symbolically bind modern Mexico to the “great civilizations” of pre-colonial times. Yet, as Christina Bueno catalogs in The Pursuit of Ruins , even as Díaz’s government went to great lengths to preserve archaeological evidence of Mexico’s Indigenous past, the process of reframing the nation’s history excluded and denigrated its modern Indigenous population. Learn more about Bueno’s work here .

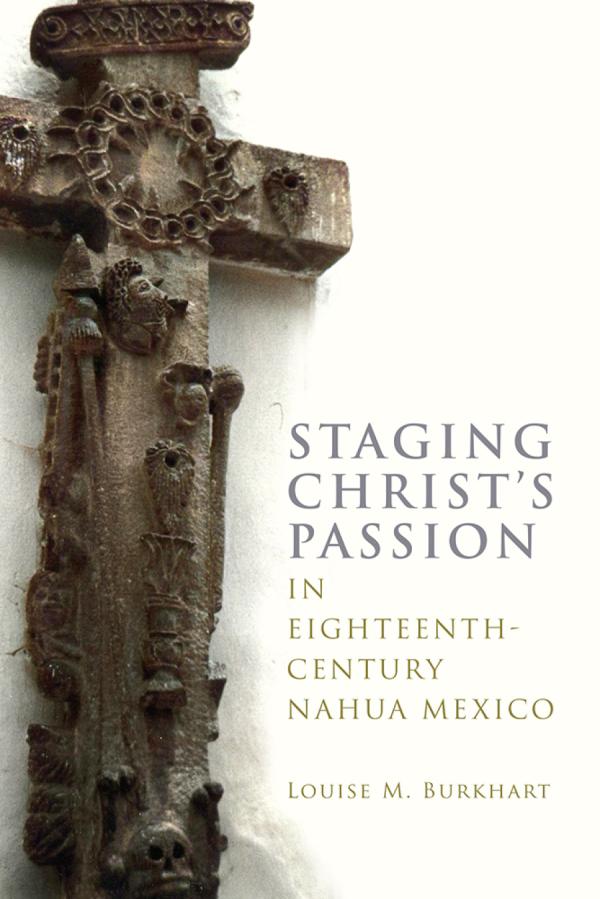

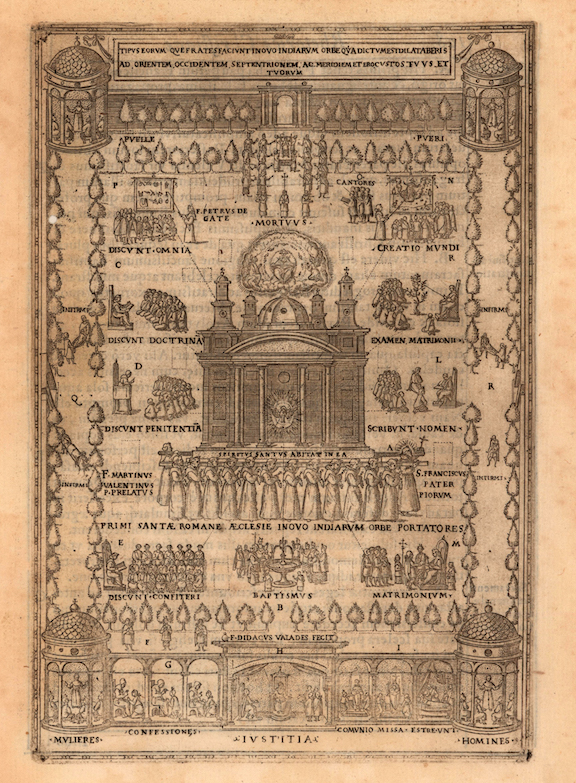

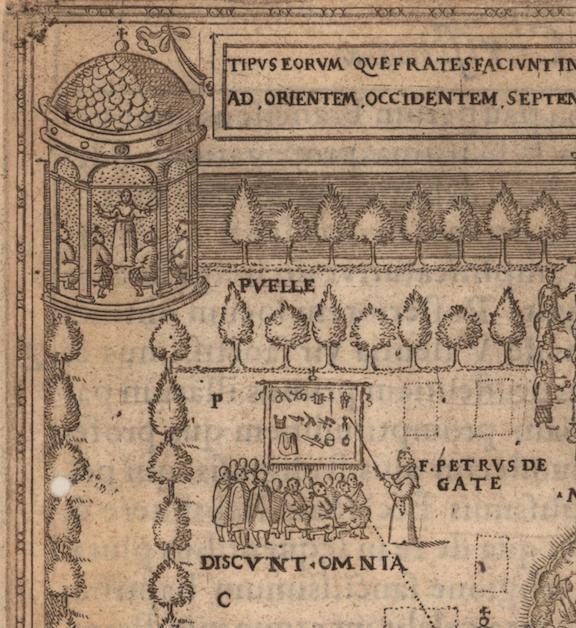

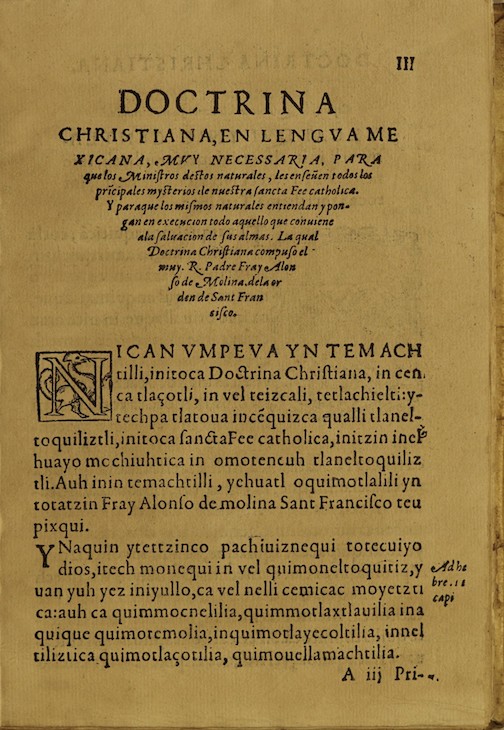

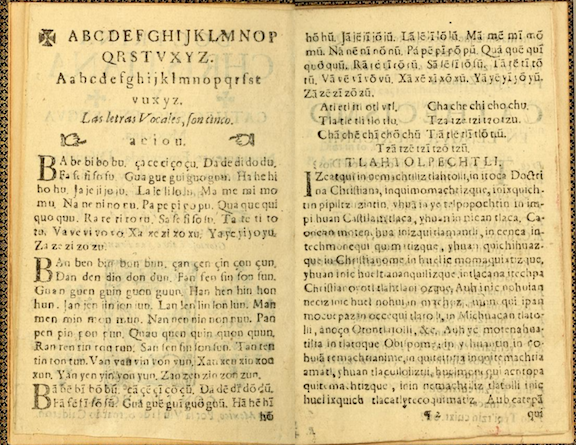

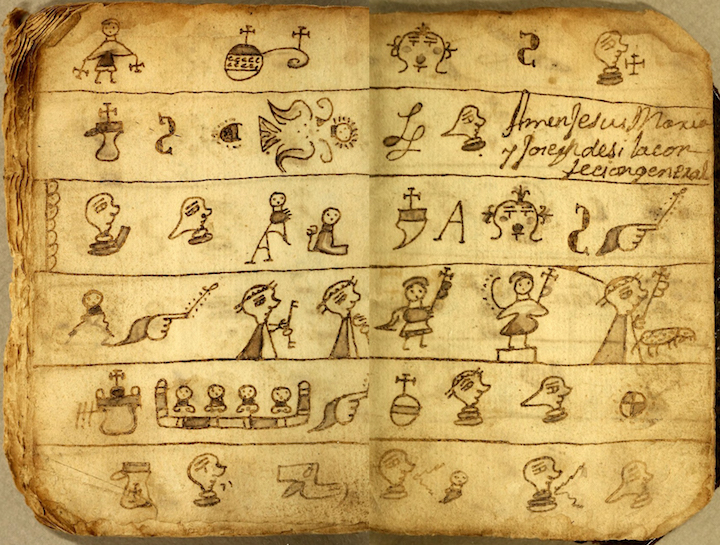

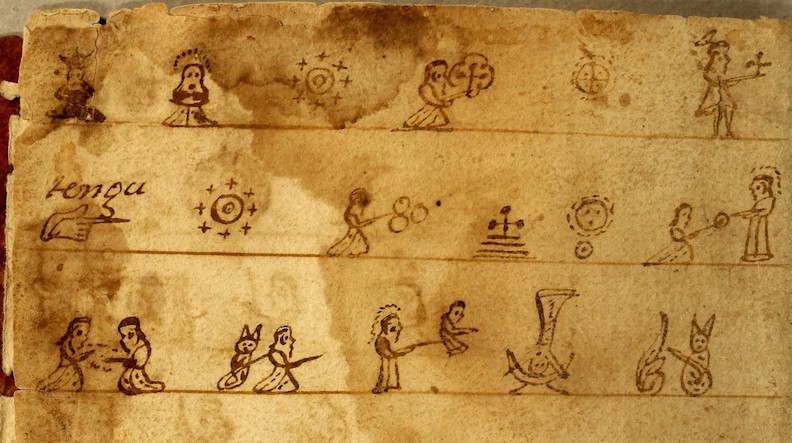

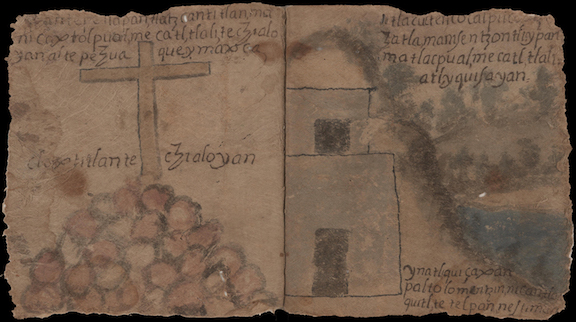

Burkhart, Louise M. Staging Christ's Passion in Eighteenth-Century Nahua Mexico (University Press of Colorado, 2023).

While living under eighteenth-century Spanish colonial rule, the Nahuas, a Mexican Indigenous group, performed their own versions of Christian “Passion plays” in the Nahuatl language. In Staging Christ’s Passion , Louise Burkhart characterizes the Nahuas’ dramaturgical modifications, which included depicting Jesus as a Nahua man, as an expression of Indigenous resistance to Spanish occupation. Learn more about Burkhart’s work here . Burkhart was also part of a team at SUNY Albany that was awarded an NEH grant to prepare digital translations of ten Nahuatl-language Passion plays.

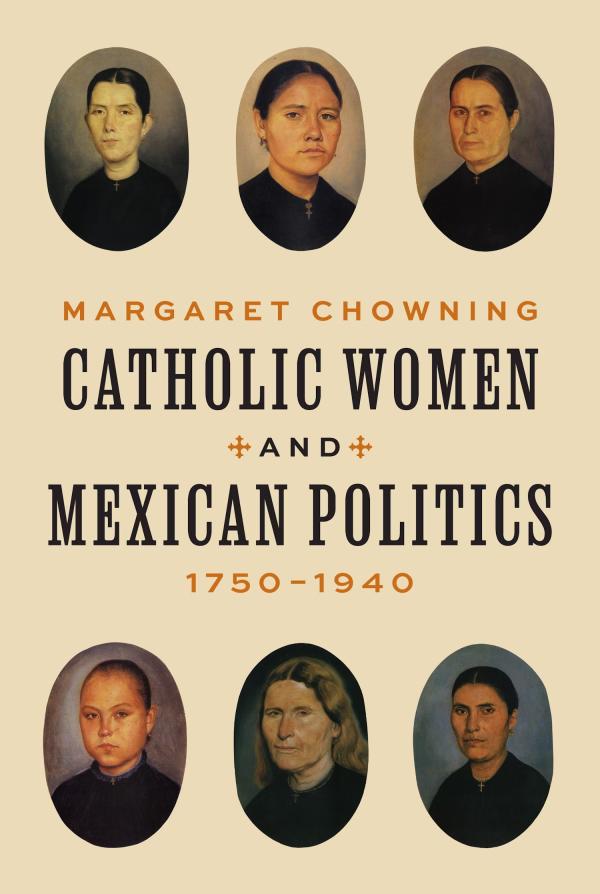

Chowning, Margaret. Catholic Women and Mexican Politics, 1750-1940 (Princeton University Press, 2023).

Throughout Mexico’s history of sustained anti-clericalism, women have been the key to the Catholic Church’s resilience, as Margaret Chowning argues in Catholic Women and Mexican Politics . For nearly 200 years, women ensured that Catholicism remained a central element of Mexican civil society by forming lay associations, which bolstered the church’s political influence. Consequently, Chowning demonstrates that women have long been in the vanguard of Mexican conservative politics. Learn more about Chowning’s work here .

Graziano, Frank. Miraculous Images and Votive Offerings in Mexico (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Exploring the role of artwork in contemporary Mexico, Frank Graziano’s Miraculous Images and Votive Offerings analyzes numerous Mexican statues and paintings that are believed to have “miraculous” capabilities. Along with analyses of the artworks themselves, the book discusses votive offerings, which are left at shrines dedicated to individual artworks as thanks for performing miracles. Thus, Graziano’s project not only offers insight into Mexican artwork and art history; it also provides insight into a distinctive dimension of the nation’s spiritual culture. Learn more about Graziano’s work here .

Rashkin, Elissa J. The Stridentist Movement in Mexico: The Avant-Garde and Cultural Change in the 1920s (Lexington Books, 2009).

In the turbulent decade after the Mexican Revolution, the Stridentist Movement gained traction in multiple Central Mexican cities before, eventually, finding the most success in Xalapa, Veracruz. The Stridentists championed modernity and technological innovation by publishing books and manifestos, staging theatrical performances, and producing artwork and literature. In The Stridentist Movement in Mexico , Elissa Rashkin illustrates that while the Stridentist Movement disbanded by 1928, its message reverberated throughout the Americas and influenced other cultural movements well after the 1920s. Learn more about Rashkin’s work here .

Rodríguez-Alegría, Enrique. How to Make a New Spain: The Material Worlds of Colonial Mexico City (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Stevens, Donald Fithian. Mexico in the Time of Cholera (University of New Mexico Press, 2019).

Although its title alludes to public health, Mexico in the Time of Cholera offers an expansive history of daily life in Mexico's early years of independence. Using the second cholera pandemic as his book’s axis, Donald Stevens explores the everyday experiences of Mexican citizens as their nation confronted contagion, emerged from colonial rule, transitioned into the modern era, and disestablished the Catholic Church. Stevens is particularly interested in Catholicism in mid nineteenth-century Mexico, and the book cites parish archives to probe the role of religion in Mexico at a time of national crisis. Learn more about Stevens’s work here .

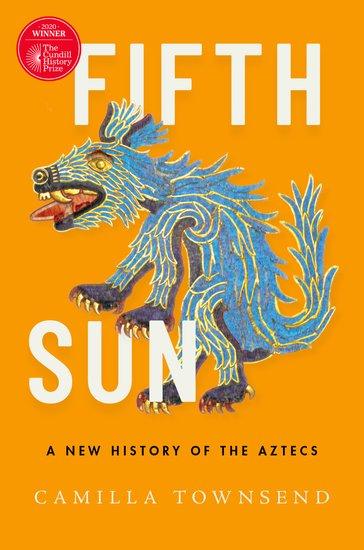

Townsend, Camilla. Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs (Oxford University Press, 2019).

In Fifth Sun , Camilla Townsend recounts the Spanish conquest of Mexico solely from the perspective of the Aztec people. To accomplish this feat, Townsend uses infrequently referenced Nahuatl-language sources, in which the Aztecs not only cataloged their experience of Spanish colonization, but also their history prior to European incursion. By relying exclusively on these self-narratives, Townsend provides a revised account of Mexico’s early history. Learn more about Townsend’s work here . Additionally, Fifth Sun received the Cundill History Prize, awarded annually by McGill University to the best book of history, in 2020. As part of this award, Townsend gave the 2021 Cundill Lecture, which can be viewed here .

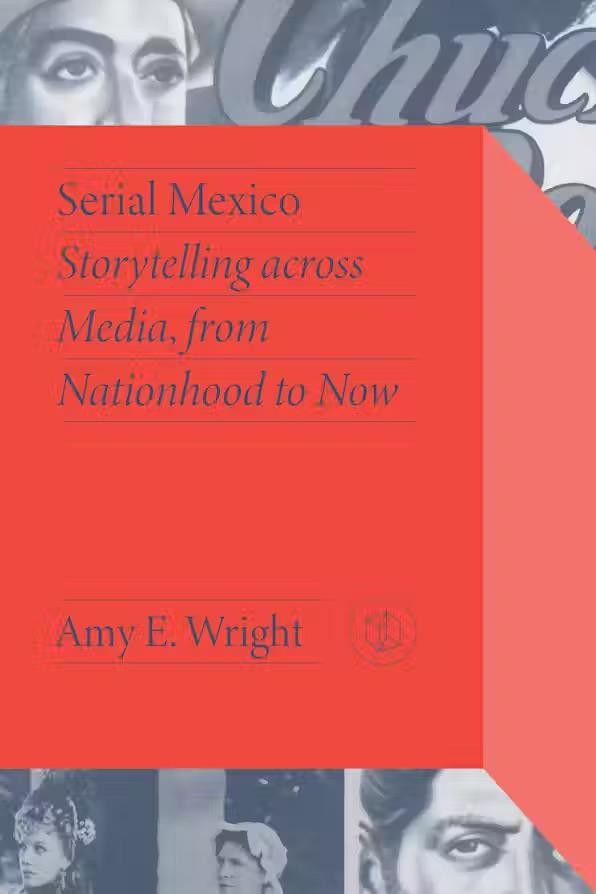

Wright, Amy E. Serial Mexico: Storytelling Across Media, from Nationhood to Now (Vanderbilt University Press, 2023).

Originating in oral tradition, serial narratives are fixtures in Mexican popular culture. Amy Wright, in Serial Mexico , explains how these time-honored stories document both change and continuity in Mexican culture. While serial narratives’ characters and story arcs may remain relatively fixed, their transmutation in the digital age—into forms ranging from comics to telenovelas—reflects evolving social and political beliefs in Mexico. Learn more about Wright’s work here .

Upcoming Books

“Revolutionary Forms: U.S. Literary Modernism and the Mexican Vogue, 1910-1940” by Geneva M. Gano

Analyzing artwork and writing produced by Mexican and U.S. artists in the early twentieth century, Geneva Gano’s upcoming book will highlight the Mexican Revolution’s influence on literary modernism in the United States. Unlike canonical scholarship on modernist literature, which typically exalts European impact in the U.S., Gano’s study will situate the works of prominent modernists in the context of the Americas, demonstrating the under-documented confluence of U.S. and Mexican literature. Learn more about Gano’s work here .

“Mexican Soundscapes of the Colonial Era” by Alexander Hidalgo

Although Alexander Hidalgo’s upcoming book will draw on print archival sources, his subject cannot be fully captured in written media. Focusing on Mexico’s colonial era, Hidalgo will explore the varied “soundscapes” of early Mexican history, from the cannon blasts that colonizers used to enforce obedience to the riotous shouts of anti-colonial protestors. With sound as its focal point, Hidalgo’s book promises to provide an account of Spanish colonialism in Mexico unlike any written previously. Learn more about Hidalgo’s work here .

“Protestant Women and Political Activism in Mexico, 1900-1955” by Kathleen Mary McIntyre

In what will be the first history of its kind, Kathleen McIntyre’s upcoming book will document the distinct forms that Protestant women’s citizenship took in post-revolutionary Mexico. Despite prevailing beliefs that politics were antithetical to both Protestantism and femininity, these women organized numerous civil society groups—including suffrage clubs and temperance organizations—that advanced both evangelical and feminist aims. McIntyre will also discuss contemporary relations between Catholic and Protestant Mexican women at a time when their nation’s religious culture was exceptionally fraught. Learn more about McIntyre’s work here .

“Making Paper in Mexico: A Material, Political, and Environmental History” by Corinna Zeltsman

In her upcoming material history, Corinna Zeltsman will explore the wide-ranging implications of papermaking in Mexico’s past. While paper was a source of political power during the nation’s early years of independence, it quickly became a locus of economic and political contention in the nineteenth century as various industries—from logging to paper mills, to newspapers—became increasingly dependent on paper for their prosperity. Learn more about Zeltsman’s work here .

Division/Office

SPANISH: Find Articles

- Get Started

- Find Articles

- Find Internet Resources

- Writing & Citing

- Search Tips & Tutorials

Key Databases

These databases contain a combination of full text articles (ready to read online) and citation information about articles, book chapters, or books. Check out our full Database A-Z list and choose a Subject from the drop-down menu to find other databases for your research topic.

Arts & Literature

- MLA International Bibliography This link opens in a new window literary criticism - search in Spanish or English

- Literature Resource Center This link opens in a new window Biographies, bibliographies and full-text critical analysis of authors from all genres and eras.

- Film & Television Literature Index with Full Text This link opens in a new window Articles on film and television theory, writing, production, cinematography, reviews, and more, 1914 to present.

- Art Full Text This link opens in a new window Find articles on all aspects of art, including fine, decorative and commercial art, folk art, photography, film, and architecture.

- RILM Abstracts of Music Literature This link opens in a new window Citations and abstracts for significant writings on music: journal articles, conference proceedings, Festschrifts, books & dissertations, 1967 to present

History, Politics, & Society

- Historical Abstracts with Full Text This link opens in a new window Articles on world history from 1450, excluding US & Canada, written since 1955. Can be co-searched with America: History & Life

- GenderWatch This link opens in a new window With a focus on how gender impacts a broad spectrum of subject areas, this collection gathers historical perspectives on the evolution of the women's movement, men's studies, the transgender community, and changes in gender roles, including articles dating back as far as the 1970s.

- Women's Studies International This link opens in a new window Find journal articles and books on women's studies, feminism, and gender studies.

- Social Science Premium Collection This link opens in a new window Search many social science databases at once. Disciplines covered include sociology, political science, education, economics, anthropology, linguistics, and criminology. Component databases can also be searched individually.

Multidisciplinary

Full text scholarly articles in all disciplines.

- JSTOR This link opens in a new window Collection of key scholarly journals in the humanities, social sciences & natural sciences, starting from the first issue but not the latest 3-5 years.

An interdisciplinary, bilingual (English and Spanish), full text database of newspapers, magazines, and journals from ethnic, minority and native presses, 1960 to present.

Spanish-language portals

- Redalyc Redalyc serves as a portal to more than 15,000 full text articles published in over 700 journals that come from 15 countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal, mostly in Spanish. Subject coverage includes topics in the social sciences, arts and humanities, and the natural sciences.

- Dialnet An open-access portal that provides access to citations and some full text for journal articles, books, and other scholarly materials from the Hispanic world. Can't find the full text? Request it through Interlibrary Loan!

Latin-American Studies

- Handbook of Latin American Studies This link opens in a new window Selective annotated bibliography of articles, book chapters, and papers on Latin American life and culture, 1936 to present. Disciplines covered include anthropology (archeology and ethnology), art, geography, government and politics, history, international relations, literature, music, philosophy, political economy, and sociology.

- << Previous: Find Books

- Next: News >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2024 4:29 PM

- URL: https://libguides.wellesley.edu/spanish

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cell Stress Chaperones

- v.22(6); 2017 Nov

The reality of scientific research in Latin America; an insider’s perspective

Daniel r. ciocca.

1 Oncology Laboratory, Institute of Experimental Medicine and Biology, CONICET, CCT, 5500 Mendoza, Argentina

Gabriela Delgado

2 Immunotoxicology Research Group, Pharmacy Department, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Carrera 30 No. 45-03, Edificio 450, Bogotá, Colombia

There is tremendous disparity in scientific productivity among nations, particularly in Latin America. At first sight, this could be linked to the relative economic health of the different countries of the region, but even large and relatively rich Latin American countries do not produce a good level of science. Although Latin America has increased the number of its scientists and research institutions in recent years, the gap between developed countries and Latin American countries is startling. The prime importance of science and technology to the development of a nation remains unacknowledged. The major factors contributing to low scientific productivity are the limited access to grant opportunities, inadequate budgets, substandard levels of laboratory infrastructure and equipment, the high cost and limited supply of reagents, and inadequate salaries and personal insecurity of scientists. The political and economic instability in several Latin America countries results in a lack of long-term goals that are essential to the development of science. In Latin America, science is not an engine of the economy. Most equipment and supplies are imported, and national industries are not given the incentives to produce these goods at home. It is a pity that Latin American society has become accustomed to expect new science and technological developments to come from developed countries rather than from their own scientists. In this article, we present a critical view of the Latin American investigator’s daily life, particularly in the area of biomedicine. Too many bright young minds continue to leave Latin America for developed countries, where they are very successful. However, we still have many enthusiastic young graduates who want to make a career in science and contribute to society. Governments need to improve the status of science for the sake of these young graduates who represent the intellectual and economic future of their countries.

Social and economic disparities in Latin America

The day-to-day life of Latin Americans is greatly affected by the political composition of their ruling governments. Policies implemented by parties that come and go have a great impact on the economy; health care; and education; and not surprisingly, scientific activity. Latin America is made up of many countries with different histories, different economies, and different political situations (Schneider 2014 ). However, even relatively stable countries like Chile and Uruguay (currently politically and economically healthy) have suffered in recent history from dictatorial, autocratic, and/or populist governments (Puhle 1987 ; Arenas 2006 ; Donghi 2013 ). None of these countries give enough priority to scientific and technological developments (Schneider 2014 ), which has a tremendous impact on the life of their citizens. In some countries, the existence of a well-equipped research laboratory depends on whether the investigator shares the ideology of the ruling government. Moreover, Latin American countries have the most unequal income distribution in the world (United Nations Commission on Science and Technology for Development 2013 ) which results in research inequalities across the region (Van Noorden 2014 ). The macro-economy reflected in the gross domestic product (GDP) of nations like Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina is far higher than of other Latin American countries (World Development Indicators), but these countries are coping with the same problems as others in the region. Brazil is fighting political and economic instability, corruption, crime, and narco-traffickers and is slowly emerging out of its recession; Mexico has high levels of corruption, crime, and narco-trafficking; and Argentina has a very high level of inflation and is fighting corruption, crime, and narco-traffickers. Colombia has been at war with guerrillas and narco-traffickers for years, Venezuela is suffering from a decaying economy after years of populism, Peruvians are clamoring for less discrimination and inequality, Chileans are demanding better educational options and lower inequality, and Cubans are still trying to identify and solve their own problems. All this creates stress for ordinary citizens and scientists alike and makes us pessimistic about the economic forecast for Latin America (Cottani and Oliveros-Rosen 2016 ).

Importance of science

The contributions of science to society are obvious in many discoveries in medicine (e.g., antibiotics) and in the development of technologies (e.g., computers). For this reason, developed countries spend a large proportion of their annual budgets on research. Unfortunately, this paradigm has not been adopted by Latin American countries where research is still a minor activity performed by an “elite” class of individuals. Thus, countries with a weak research tradition are reliant on nations with a robust research culture and remain mainly providers of raw materials. Moreover, problems unique to a particular developing country will remain ignored by the global scientific community until they too are affected, as was clearly shown in the case of the Ebola epidemic (Omoleke et al. 2016 ). Latin American scientists have been very successful in global scientific work; several Latin American investigators have been Nobel Laureates in the Natural Sciences (LaRosa and Mejia 2015 ). The low scientific productivity in Latin America is not the result of a lack of creativity but is rather the product of a negative environment created by the leadership of each nation. The allocation of resources for research in Latin America is in great disproportion with that in developed countries (Table (Table1 1 ).

Funds assigned for research and other data in Latin America

| Country | Population | Inflation | UR | GDP (R + D) | Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 41.45 M | 28.3 (2014) | 7.3 (2014) | 0.58 (2017) | 1121 (2010) |

| Brazil | 200.4 | 9–11 (2015) | 8.5 (2015) | 1.24 (2013) | 698 (2010) |

| Bolivia | 11 | 3–4 (2015) | 4 (2015) | 0.16 (2009) | 166 (2010) |

| Chile | 17.62 | 4.4 (2015) | 6.3 (2015) | 0.36 (2012) | 320 (2012) |

| Colombia | 48.32 | 5–6 (2015) | 8.9 (2015) | 0.23 (2013) | 193 (2010) |

| Costa Rica | 4.87 | −1 (2015) | 9.7 (2014) | 0.47 (2011) | 1233 (2010) |

| Cuba | 11.27 | 6 (2013) | NA | 0.47 (2013) | NA |

| Ecuador | 15.74 | 4 (2015) | 5.4 (2015) | 0.34 (2011) | 141 (2010) |

| El Salvador | 6.34 | 1 (2015) | 7 (2014) | 0.03 (2012) | NA |

| Guatemala | 15.47 | 2–3 (2015) | NA | 0.04 (2012) | 25 (2010) |

| México | 122.3 | 2.7 (2015) | 4 (2015) | 0.50 (2013) | 312 (2010) |

| Panamá | 3.86 | 0.3 (2015) | 5.1 (2015) | 0.18 (2011) | NA (2010) |

| Paraguay | 6.8 | 3.1 (2015) | 5.8 (2015) | 0.09 (2012) | NA |

| Peru | 30.9 | 3–4 (2015) | 6.5 (2015) | 0.15 (2014) | NA |

| Puerto Rico | 3.54 | −1 (2015) | 14 (2014) | 0.44 (2013) | NA |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1.34 | 1–4 (2015) | 3.4 (2015) | 0.05 (2012) | NA |

| Uruguay | 3.40 | 8–9 (2015) | 7.5 (2015) | 0.32 (2013) | 549 (2010) |

| Venezuela | 30 | 140 (2015) | 6.8 (2015) | 0.2–0.5 (2006) | 200 (2010) |

| Developed countries (added for comparative purposes) | |||||

| USA | 316 | 3.29 (2015) | 5.5 (2015) | 2.73 (2013) | 3867 (2010) |

| China | 1357 | 1.44 (2015) | 3.1 (2016) | 2.01 (2013) | 903 (2010) |

| Japan | 127 | 0,80 (2015) | 4.1 (2015) | 3.47 (2013) | 5153 (2010) |

Some countries are not mentioned because we were unable to locate their GDP for R + D

NA not available

a Population for the year 2013, expressed in millions (M)

b,c Annual inflation and UR: unemployment rate from http://www.focus-economics.com/regions/latin-america

d Percentage of the GDP assigned to Research and Development. From http://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/GB.XPD.RSDV.GD.ZS

e Per million people. Data from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.SCIE.RD.P6

We acknowledge some progress in the sciences however; Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina have been leading in several parameters of science in Latin America (Albornoz 2002 ). Mexico increased its expenditures in research and development between 2012 and 2016 (Sánchez 2016 ). But, all Latin American countries are still functioning far below developed countries (Ruiz 2000 ; Piñón 2003 ; Kuramoto 2013 ). It is clear that in Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Paraguay, and Peru, the resources assigned for research and development (by both public funds and by private businesses) are not priorities for their governments (Table (Table1). 1 ). In addition, Latin American countries are not using scientific developments to solve their problems in health care, education, poverty, and the unequal distribution of wealth. According to the Chilean scientist P. Astudillo, a scientific policy was adopted in Chile that reduced research to its economic dimension only and which has proved a failure (Astudillo 2016 ). This author also emphasizes that in today’s society, decision-making in practically all areas must be accompanied by scientific knowledge (Astudillo 2016 ). In a global world, scientific and technological development will generate jobs of both high quality and high human capital and those nations that do not keep pace will suffer the greatest loss (Schuster 2017 ).

Research funding in Latin America

Although Latin American institutions have high expectations for their investigators and require them to publish in high impact journals (Thomaz and Mormul 2014 ), the financial support for research is inadequate to meet these high standards. Most grants in Latin America are provided by governmental institutions and are insufficient for the needs of a competitive research enterprise. A typical governmental grant for a research group or laboratory in Latin America is in the order of $5,000 to $40,000 per year, which is well below typical grants provided by well-developed countries.

Unlike in the USA where science is truly an engine of the economy, private industries in Latin America are in general reluctant to invest in scientific development. Latin America and the Caribbean countries invest less in research than other developed and emerging countries, and the participation of private companies is very limited (Lemarchand 2010 , United Nations Commission on Science and Technology for Development 2013 ). There are some government programs designed to encourage private companies to invest in scientific and technological developments, such as the FONTAR program in Argentina that assigned almost $50 million to develop manufacturing of computerized machinery and equipment. However, these possibilities are limited and are basically driven by the government (Erben 2016 ).

A major problem in Latin America is a lack of clear rules for the distribution of research funding, which is sometimes distributed based on political alliances and aggravated by economic instability, resulting in a negative impact on the development of innovative technologies. Moreover, government taxes are high without a corresponding investment in resources. Most reagents and equipment have to be imported from other countries. When asked to provide goods for research, Latin American industries argue that scientists prefer to purchase products from recognized international companies and that they cannot compete with foreign companies.

The contribution to science by universities differs from country to country. Argentina mandates that professors combine their teaching with high-impact scientific work; however, the government and university support for academic research is very limited (Dallanegra Pedraza 2004 ). In Colombia and Brazil, support for research activities is significant at private universities. In Colombia, public universities invest even more in research and development than private universities do. In Chile, universities play a significant role, with about 80% of the total number of researchers having a doctoral degree (Quiroz 2016 ). In Cuba, despite the existence of a set of laws and resolutions to organize science financing, these resources are often not well used due to the poor organization of this financing system (Benet Rodríguez et al. 2010 ).

In summary, economic resources assigned for research grants in Latin America fall short of what is needed. The UNESCO Science Report (UNESCO 2015 ) emphasized that most Latin American countries have not used their valuable exports in recent years to stimulate scientific and technological competitiveness, such as in the development of pharmaceutical and/or equipment industries to avoid the high cost of medical supplies.

Purchasing products for scientific research: the economic drain

The international scientific community is probably unaware of the difficulties Latin American researchers face daily to acquire the reagents and equipment necessary for their work. Prices are disproportionately high compared with those in developed countries. Two factors drive up the cost of scientific reagents and equipment in Latin America. The import of scientific supplies is not excluded from a heavy tax intended to protect national products and which does not apply to research products that are locally produced. Indeed, many Latin American countries do not support free trade agreements with the USA, and research goods are considerably more expensive. In addition, customs bureaucracy is responsible for the delay of merchandise delivery which affects the quality of the products. Finally, there is no free competition among reagent suppliers, which form a monopoly directed at speculation. Most Latin American countries concentrate their resources and researchers in large cities, placing smaller cities at a disadvantage for the distribution of reagents and supplies and making collaboration among scientists more difficult. In a relatively small city (1 million), when one research laboratory has a broken flow cytometer, there may be no replacement in the same city.

The economic and social burden of Latin American scientists

In many Latin America countries, scientists do not have a salary in accordance with their education, knowledge, and contribution to society. Scientists’ salaries are markedly lower than those of judges and elected officials (Table (Table2). 2 ). The low purchasing power of scientists makes it difficult to buy a home and support the education of their children. In addition, increased crime has forced scientists to live in gated communities, and the deterioration of public education has forced them to send their children to private schools. Scientists expend a large proportion of their salaries on these important items. Many young graduates see the scientific environment as too restricted, too competitive, and too poorly funded to provide a certain future in research institutions. Because a career in science is poorly paid, most medical doctors are better off pursuing a clinical practice rather than participating in research, even part time. Indeed, there are fewer than 10% of medical doctors in the Commission of Medical Sciences in the Argentine National Research Council (CONICET).

Data comparing salaries and prices of apartments and cars in Latin America

| Country | Researcher | Judge | Senator | Professor | Apartment | Car |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 1200–3000 | 10,000 | 6000 | 2000 | ≅180,000 | ≅24,000 |

| Brazil | 1700–4000 | 10,000 | 8000 | 4000 | 200,000 | ≅18,500 |

| Chile | 2000–5000 | 7000 | 12,000 | 5000 | ≅150,000 | ≅14,000 |

| Colombia | 3000–7000 | 5000 | 10,000 | 3000–8000 | ≅200,000 | ≅19,000 |

| Mexico | 2200–3500 | 6300 | 6700 | 3600 | ≅190,000 | ≅15,500 |

| Uruguay | 2600–3500 | 4300 | 3400 | 3500 | ≅190,000 | ≅22,000 |

The salary in USD per month, in the case of researches considering the first position (young investigator) and the last position (about 30 years) in the main research institutions. These data have been provided by researchers from the different countries and the salaries are considering the basic + additional (pocket money). Judge: federal, with 30 years. Senator: national. Professor: full time in a National University. Apartment: price of a two bedrooms apartment in the capital of the country in a good location. Car: price of a brand new, medium-sized car (taken as example Renault Duster)

Nowadays, a publication fee of $3400–5000 applies to high-impact factor journals; these journals offer publication fee discounts for papers whose corresponding authors are based in HINARI countries (the world’s lowest-income countries as defined by the World Bank): Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua are in the free-access group while Argentina, Bolivia, and El Salvador are in the low-cost access. Therefore, many Latin American scientists prefer to publish their scientific discoveries in journals that do not charge for publication costs since it is very difficult to pay page charges from their modest grants. These journals are the ones with lower impact factors, which may make Latin American science seem second rate. In addition, most governments or academic institutions have not signed agreements for access to open-access articles, creating difficulties for Latin American scientists to obtain high-impact research articles; the cost of subscriptions is a serious problem for Latin American institutions with very limited budgets.

Bureaucracy and other problems

At first sight, the number of research institutions, programs, commissions, and other research-related entities in Latin America is overwhelming (Lemarchand 2010 ). However, most of these institutions are plagued with bureaucracy. For example, the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Productive Innovation of Argentina has 19 independent agencies, programs, foundations, and offices, of which CONICET is one. The administrative structure is at odds with the reduced grant support, and therefore, it is not surprising that in CONICET, almost 95% of the resources are destined to pay wages. It is clear that science has not been a priority for Latin American governments; in 2014, Argentina spent about $150 million dollars on the program “Soccer for All” (a program that supported the free televising of soccer games), a budget similar to that of the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Productive Innovation (this soccer program has since been discontinued).

The lack of vision that science and technology are of prime importance to the development of a nation is a chronic problem. Latin American countries are still very far from other countries in scientific performance. For the period 2000–2015, Brazil ranked 14th, while Mexico ranked 30th, whereas Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Venezuela, Cuba, Peru, Uruguay, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Panama appeared even lower in the list (in that order) (Zanotto et al. 2016 ). This report stressed the importance of scientific collaboration, which is still far from what it should be. The low number of patents is another parameter to be considered (Kreimer 2016 ). The statement that Chile needs long and medium-term (public) policies to establish clear goals bringing together its political class, citizens, entrepreneurs, and scientists (Quiroz 2016 ) is applicable to most Latin American countries.

Latin American scientists have to be at an international level to win grants and promotions in the scientific careers and have to compete on research topics of international interest. It could be argued that science in Latin America should be directed to solve specific local problems, such as the impact of Dengue and Zika infections, and Chagas disease, or to find cheaper diagnostic methods and new regional phytochemicals that could be used to treat diseases. However, grants to support applied research are not easy to obtain because national priorities are unfocused and because it is difficult to publish the results in high-impact journals, which is against the interests of the investigators, thus creating a vicious circle. The World Health Organization has stressed the importance of research into local problems to improve health systems, priorities, and research goals for low- and middle-income countries (Xue et al. 2014 ).

The problem of brain drain

Latin America has a long history of “brain drain” while developed countries have the advantage of “brain gain.” In Chile, many young researchers and post-doctoral students find it difficult to get a foothold in the scientific system and only obtain precarious research jobs (Astudillo 2016 ). Central to this problem is the question: Are there enough research institutions to hire and retain scientists in their home countries? We mentioned earlier that the number of research institutions in Latin America is surprisingly large (Lemarchand 2010 ). However, the facilities are often inadequate; laboratories are not up to date; grants are relatively low; salaries are not at an international level; and scientists, like other citizens, feel personally insecure. In Argentina, the number of people with a doctoral education has increased noticeably in recent years, but only 50% have been absorbed into the national scientific system, with 20% leaving the country and the rest being lost to science (Estado y Perspectivas de las Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales en la Argentina 2015 ). In recent years, 1269 researchers wanted to return to Argentina from overseas to continue their research careers but there were not enough research positions to absorb this outstanding group of investigators. Moreover, Latin American researchers in developed countries feel more appreciated than at home. Salary is not the only reason; researchers find more freedom, stability, resources, and grants to develop their scientific capacity to the fullest extent. Therefore, the temptation to continue a scientific career abroad is high. In Colombia, approximately 70–80% of the resources of COLCIENCIAS (Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation) are directed to support post-doctoral fellows, but there are no funds to support the scientific project locally. Therefore, if institutions do not provide the resources for research, fellowship recipients leave to pursue investigations abroad in well-equipped laboratories, which usually results in their not returning home. Indeed, many post-doctoral fellows prefer to pay back their credit-fellowship rather than return to Colombia. Brazil’s brain drain issues continue to grow after the endemic problem of the Brazilian body politic (Murati 2016 ). In contrast, despite losing many highly qualified professionals, Mexico has attracted foreign scientists to their institutions thanks to programs for the consolidation of science and technology and to the success of international cooperation programs (Didou and Durand 2013 ).

Conclusions

Although the picture presented in this essay is discouraging, we want to finish on a positive note. Our region has many young graduates who enthusiastically wish to make a career in science. Senior scientists must guide and stimulate these younger scientists to increase the depth of their scientific inquiries (Thomaz and Mormul 2014 ) and encourage them to contribute to the improvement of science in their home countries. The Latin American society has got used to expecting new science and technological developments to come from developed countries rather than from their own scientists. We need to generate closeness between our citizens and scientists through science education and the active participation of researchers in activities within the community (Quiroz 2016 ). There is still hope that Latin America will again be the scientific powerhouse it was in the past. Latin American scientists are bright, innovative visionaries and hard workers, as shown by the great success of Latin American scientists when they are provided with stability, resources, and the freedom to investigate. Latin American governments must follow the example of developed countries and invest in long-term research goals that are not subject to change by the transition from one political party to another. The scientific/technological base of a country is constructed in a cumulative, interdependent, and competitive way (Gonçalves da Silva 2016 ). A robust commitment to research has a great influence on education and social justice too. We must all work together to advance the future of science in Latin America to create a productive environment for future generations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank colleagues from Latin America who helped with their opinions, discussions, and data. The referee comments contributed to improve significantly the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Daniel R. Ciocca, Email: ra.bog.tecinoc-azodnem@accoicd .

Gabriela Delgado, Email: oc.ude.lanu@modagledgl .

- Albornoz M (2002) Situación de la ciencia y la tecnología en las Américas. Centro de Estudios sobre Ciencia, Desarrollo y Educación Superior. Buenos Aires, Octubre de 2002, pp. 1–52

- Arenas N (2006) El proyecto chavista. Entre el viejo y el nuevo populismo. Desacatos núm. 22, septiembre-diciembre 2006, pp. 151–170

- Astudillo P (2016) Manifiesto por la Ciencia. Editorial: CATALONIA - Fundación Ciencia & Vida Colección: Ciencia & Vida. ISBN: 9789563244670