Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 09 December 2023

Research on metaphor processing during the past five decades: a bibliometric analysis

- Zhibin Peng 1 &

- Omid Khatin-Zadeh 2 , 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 928 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2039 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

Metaphor processing has been the subject of extensive research over the past five decades. A systematic review of metaphor processing publications through bibliometric tools can provide a clear overview of research on metaphor processing. In this study, we used the CiteSpace bibliometric tool to conduct a systematic review of publications related to metaphor processing. A total of 3271 works published and indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) were gathered. These works had been published between 1970 and 2022. We analyzed the co-citations of these works by CiteSpace to identify the most influential publications in metaphor processing research. A co-occurrence term analysis was done to identify dominant topics in this area of research. The results of this analysis showed that Language, comprehension, metaphor, figurative language , and context were the most frequent keywords. The most prominent clusters were students, figurative language, right hemisphere, embodied cognition, comprehension, N400 , and anger . Based on the results of this analysis, we suggest that task properties such as response format and linguistic features should be carefully taken into account in future studies on metaphor processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

The critical role of interference control in metaphor comprehension evidenced by the drift–diffusion model

COGMED: a database for Chinese olfactory and gustatory metaphor

Multimodal metaphors in a Sino-British co-produced documentary

Introduction.

How people understand and produce metaphors has long aroused the interest of scholars from various disciplines such as philosophy, linguistics, and psychology. From the 1970s, scholars began to study the processing of metaphors through experiments. Throughout the past five decades, a large body of experimental and theoretical works on metaphor have been produced, and many journals have started to publish papers related to metaphor. During this period, many researchers in neurolinguistics and psycholinguistics published their works on metaphor. These works have fundamentally changed the ways that researchers have been studying metaphors. This is particularly the case with research on metaphor processing. According to a study conducted by Han et al. ( 2022 ), research on metaphor processing has been the most active area of research on metaphor.

Metaphor processing research is an interdisciplinary area of study on metaphor that involves linguistics, psychology, and neuroscience. A large number of works on metaphor processing have been published in recent years, including reviews directed at selected subtopics. For instance, Rai and Chakraverty ( 2020 ) provided a systematic review of computational models and approaches to metaphor comprehension. This systemic review presented a concise yet representative picture of computational metaphor processing. In a related work, Kertész, Rákosi, and Csatár ( 2012 ) presented a review that was focused on the data, problems, heuristics, and results in cognitive research on metaphor. Some works have presented comprehensive reviews of studies conducted on metaphor comprehension in non-typical populations. For example, Morsanyi et al. ( 2020 ) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of metaphor processing in autism. Kalandadze et al. ( 2019 ) also presented a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on metaphor comprehension in individuals suffering from autism. This review specifically focused on task properties. However, among these works, except for a review paper published by Holyoak and Stamenković ( 2018 ), no other publication has specifically focused on theories and evidence related to metaphor processing. Furthermore, the past review papers have been primarily based on subjective judgment rather than bibliometric tools. Therefore, a systematic review conducted by bibliometric tools can shed new light on our understanding of metaphor processing research. In the literature of the field, we found just two works on bibliometrics of conceptual metaphor research (Han et al., 2022 ; Zhao et al., 2023 ). These two works have presented bibliometric assessments of published works on conceptual metaphor theory. However, they are only about conceptual metaphors in general. To fill this gap in the literature of the field, we used CiteSpace to present a systematic review of studies on metaphor processing.

CiteSpace is a bibliometric analysis tool that can provide an exhaustive account of research in any area over a certain period of time. In this way, it can suggest some directions for future research. Compared to those reviews relying on subjective judgment, a review conducted by CiteSpace can help us navigate through the key documents, research fields, and dominant topics in metaphor processing. Importantly, the results of such analysis can be presented in the form of easily understandable diagrams. We intended to identify the most productive and influential journals, authors, and institutions in the field of metaphor processing. Also, we intended to identify the most influential documents, active research areas, and dominant topics in metaphor processing research. Specifically, by analyzing the co-occurrence of keywords associated with metaphor processing, we aimed to depict a cluster picture of related keywords and dominant topics in this area of research. In this way, we intended to answer the following research questions:

Q1: What are the active research areas and dominant topics in metaphor processing research?

Q2: Is it possible to use a cluster picture of related keywords and research topics to identify research features that play a critical role in studies on metaphor processing?

We hypothesized that a cluster picture of related keywords and research topics in metaphor processing can be used to identify critical research properties that can be taken into account in future studies on metaphor processing.

Methodology

Data collection.

As the study was focused on metaphor processing, we collected and analyzed the published documents by conducting an advanced search in the Web of Science (WoS), Thomson Reuters Core Collection. This search incorporated Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A and HCI), Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED), and Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH). We chose WoS as the data source for two reasons. Firstly, WoS has established an independent and comprehensive editing process to ensure the excellent quality of the journals and has formed an unparalleled data structure based on more than 50 years of consistent, accurate, and complete indexing. The indexed journals in the Web of Science Core Collection have been carefully selected. Therefore, the articles indexed in WoS are of high quality. Secondly, WoS is CiteSpace’s primary data source. CiteSpace has been designed to work with WoS data. Datasets from other sources have to be transformed before they can be visualized in CiteSpace.

The following fields were used to retrieve the data:

TS = (metaphor*) AND (process* OR comprehen*)), which means that only articles with both “metaphor” and “process” or comprehen(sion) in the title or abstract, or keywords are retrieved.

Time span=1970–2022

Document Type=article OR review

(“*”is a wildcard in WoS that represents any group of characters, including no character. For example, metaphor*=metaphor, metaphors, and metaphorical, etc. In addition, the review articles in this research do not contain book reviews.)

Totally, 8358 papers were collected from 123 WoS categories, including experimental psychology, neurosciences, business, linguistics, management, music, nursing, and law. In our study, we specifically focused on metaphor-processing research in the fields of linguistics, psychology, and neurosciences. Therefore, we chose the WoS categories related to linguistics, psychology, neurosciences, literature, communication, sociology, philosophy, anthropology, religion, history, and law (i.e. “Linguistics” or “Language Linguistics” or “Psychology Experimental” or “Education Educational Research” or “Neurosciences” or “Psychology Multidisciplinary” or “Psychology Clinical” or “Psychology” or “Psychology Psychoanalysis” or “Psychology Educational” or “Psychology Applied” or “Psychology Social” or “Psychology Developmental” or “literature” or “communication” or “sociology” or “philosophy” or “anthropology” or “religion” or “history” and “law”). After excluding those works that were unrelated to metaphor processing, 3271 publications remained for further analysis.

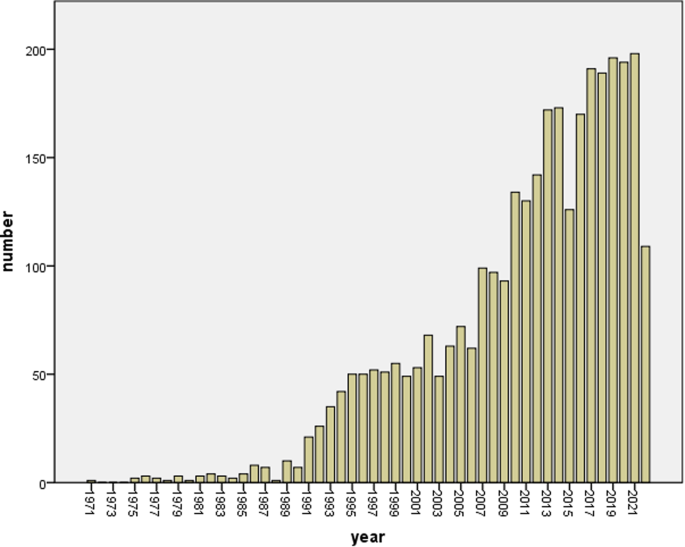

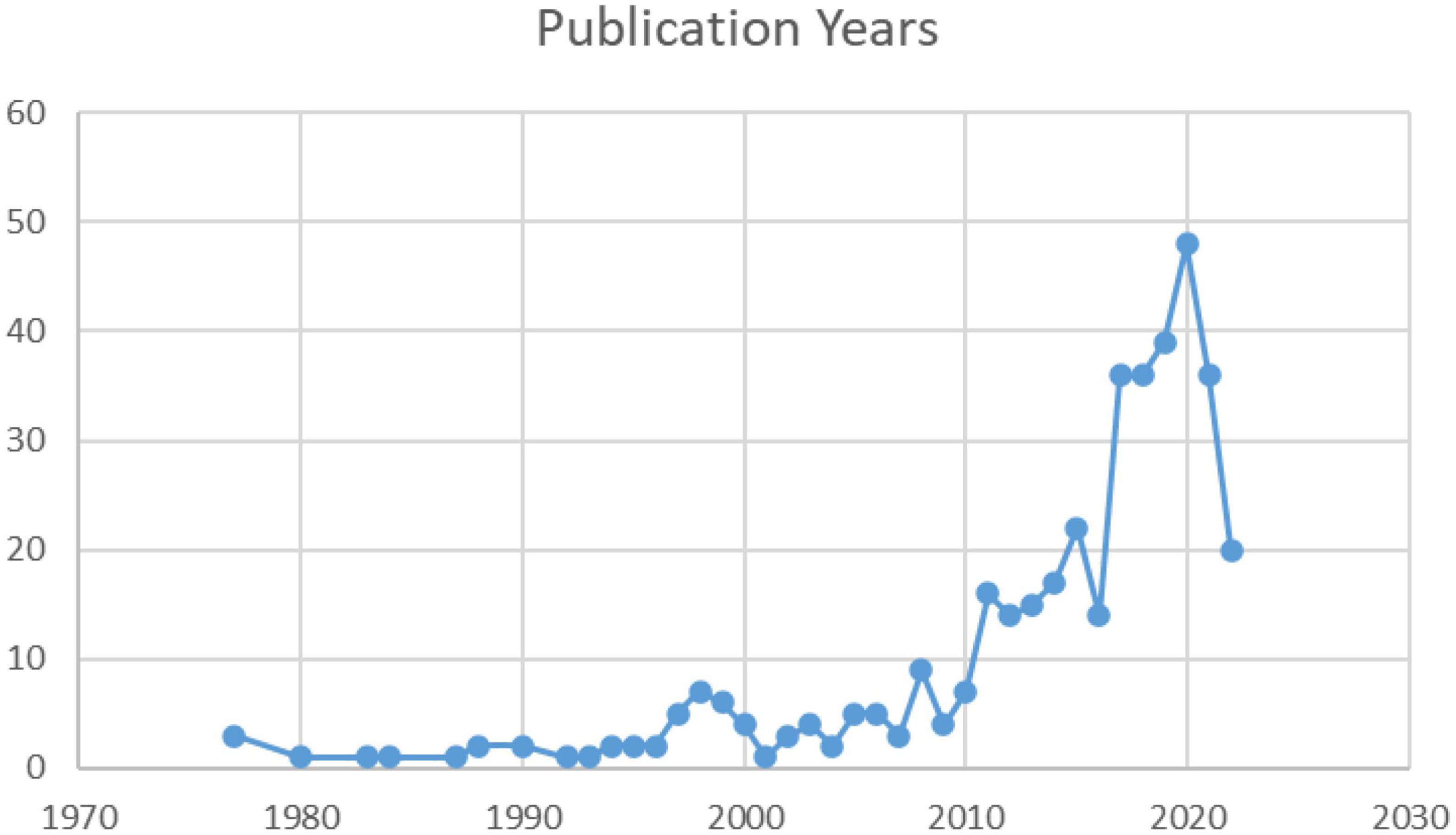

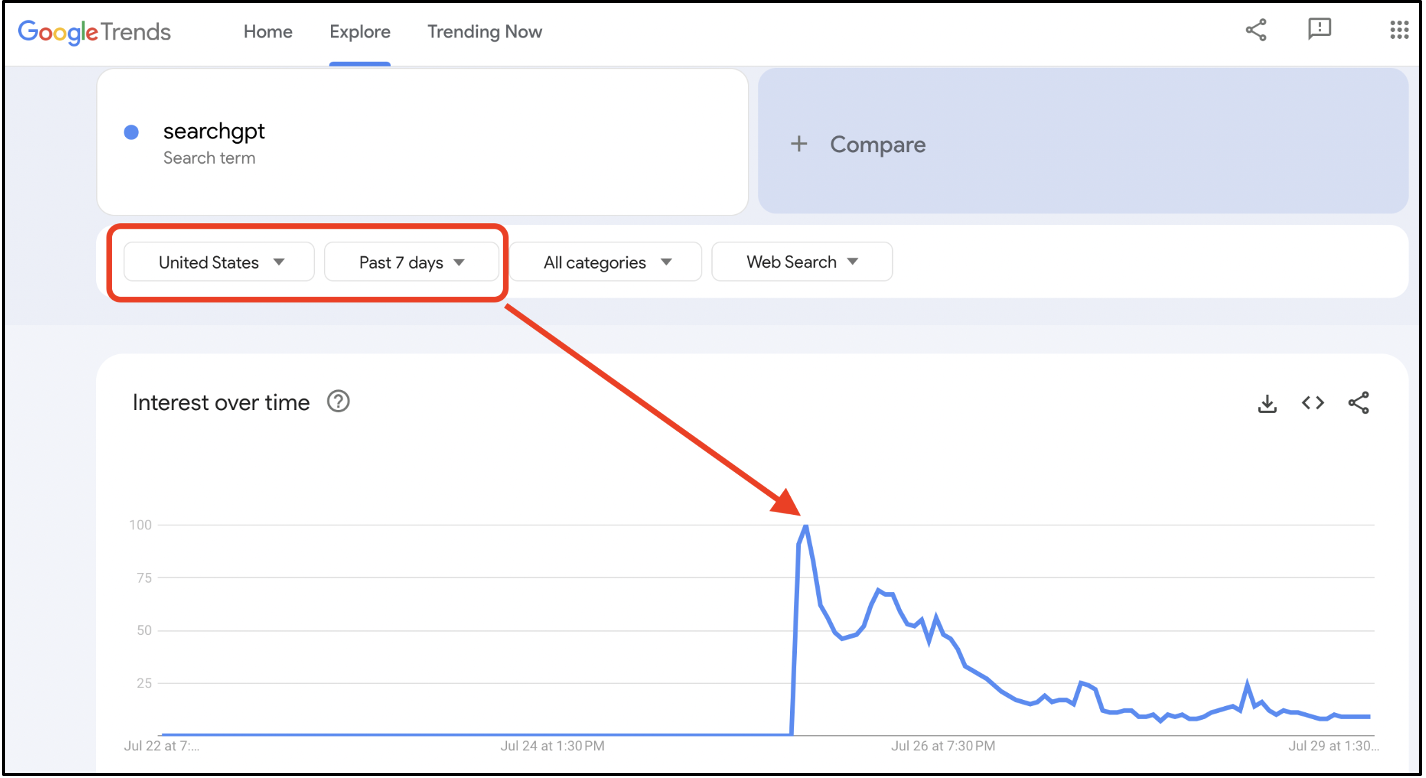

Descriptive analysis

Before visualization by CiteSpace, we conducted a descriptive analysis of yearly publication trends. Our aim was to identify the most productive journals, authors, and institutions. These descriptive analyses were directly done on the data obtained from the WoS website. The number of works published each year has been given on the WoS website. We used SPSS software to obtain the annual trend of publications (see Fig. 1 ). The numbers of publications for each journal, author, and institution have also been given on the WoS website. We selected the top ten for analysis.

The diagram reveals the publication number for each year and the general trend.

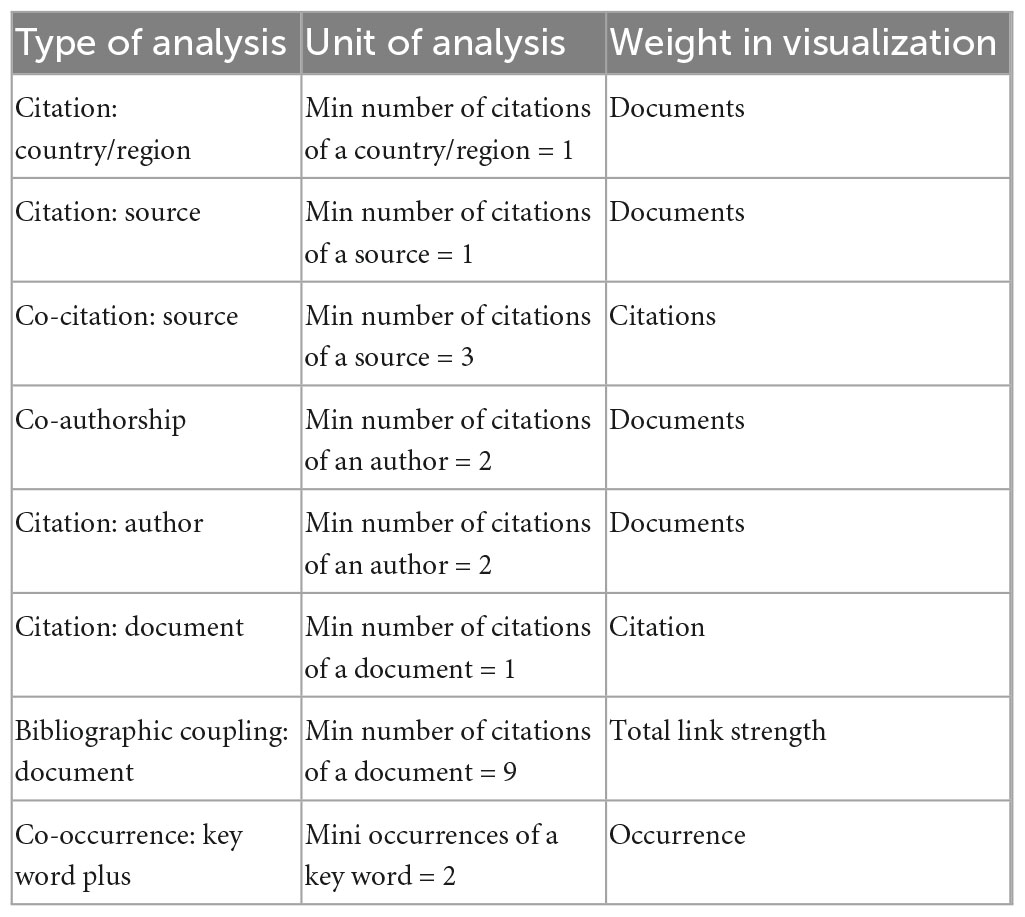

CiteSpace analysis

The descriptive analysis of WoS provides only a basic overview of the research field. It cannot provide an exhaustive account of the research projects over previous decades and directions for future research. Previous reviews without bibliometric tools mainly relied on prior knowledge and subjective judgment. To address this problem, we used CiteSpace to examine the structures of the knowledge of metaphor processing that have been developed over the past years.

In this study, we used CiteSpace, a bibliometric analysis program developed by Chen ( 2004 , 2006 , 2017 ; also see Chen et al., 2010 ; Chen and Song, 2019 ). Bibliometric analysis offers an objective and quantitative method for examining published works in a certain area of research (Mou et al., 2019 , p. 221; Chen, 2020 ). CiteSpace is a Java application for analyzing co-citations and presenting them in the form of visual co-citation networks (Chen, 2004 ). CiteSpace is one of the most well-known bibliometric tools. It offers a variety of analyses, such as keyword analysis and reference analysis, to help academics identify current and upcoming research trends in a field (Mou et al., 2019 ). The bibliographic data files we collected from WoS were in the field-tagged Institute for Scientific Information Export Format. The “full record and cited references” was selected as the content. In this way, CiteSpace could easily identify the files. Once the files were loaded into the CiteSpace, the following procedural operations were performed on them: time slicing, thresholding, modeling, pruning, merging, and mapping (Chen, 2004 ).

In this study, we conducted two separate visualizing analyses of the data. One was a document co-citation analysis, which helped us to identify the important documents in metaphor processing research. A co-cited reference was called a node, and when several nodes were strongly related to one another, they formed a cluster. The other was a keyword co-occurrence analysis. The purpose of this analysis was to identify the most-discussed areas in research on metaphor processing.

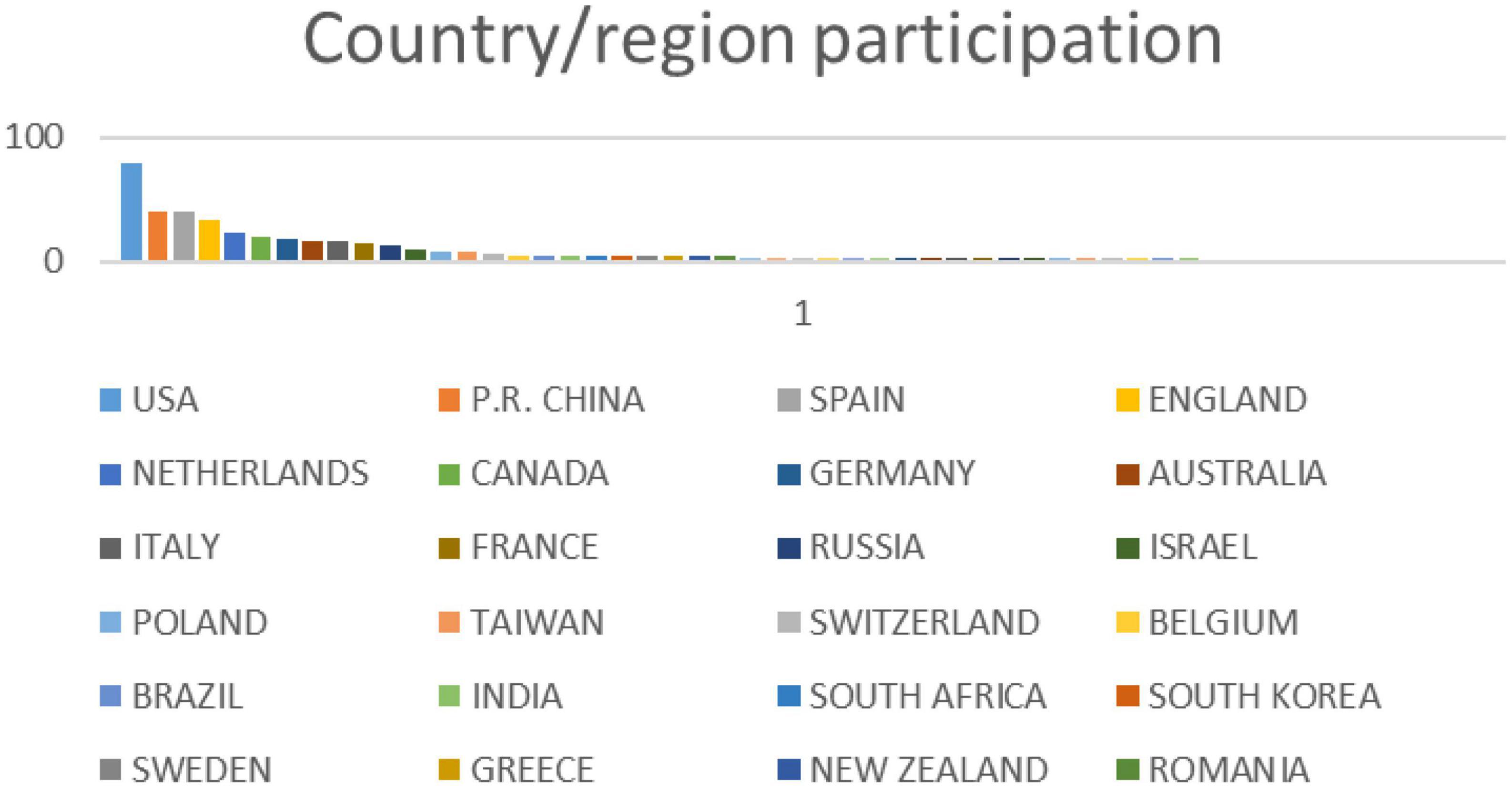

Publication years, journals, productive authors, and institutions on metaphor processing

In the Web of Science core collection, the first article about metaphor processing we obtained was published in 1971 by Laurette ( 1971 ). There was no publication on metaphor processing in the years 1972, 1973, and 1974. From 1995 to 2022, more than 50 works were done each year. The maximum number of annual publications belongs to 2021 with 198 published works. Figure 1 presents the annual publications on metaphor processing. Overall, the results show a steady increase in publications on metaphor processing. Therefore, it can clearly be seen that metaphor processing has caught the attention of more and more researchers worldwide.

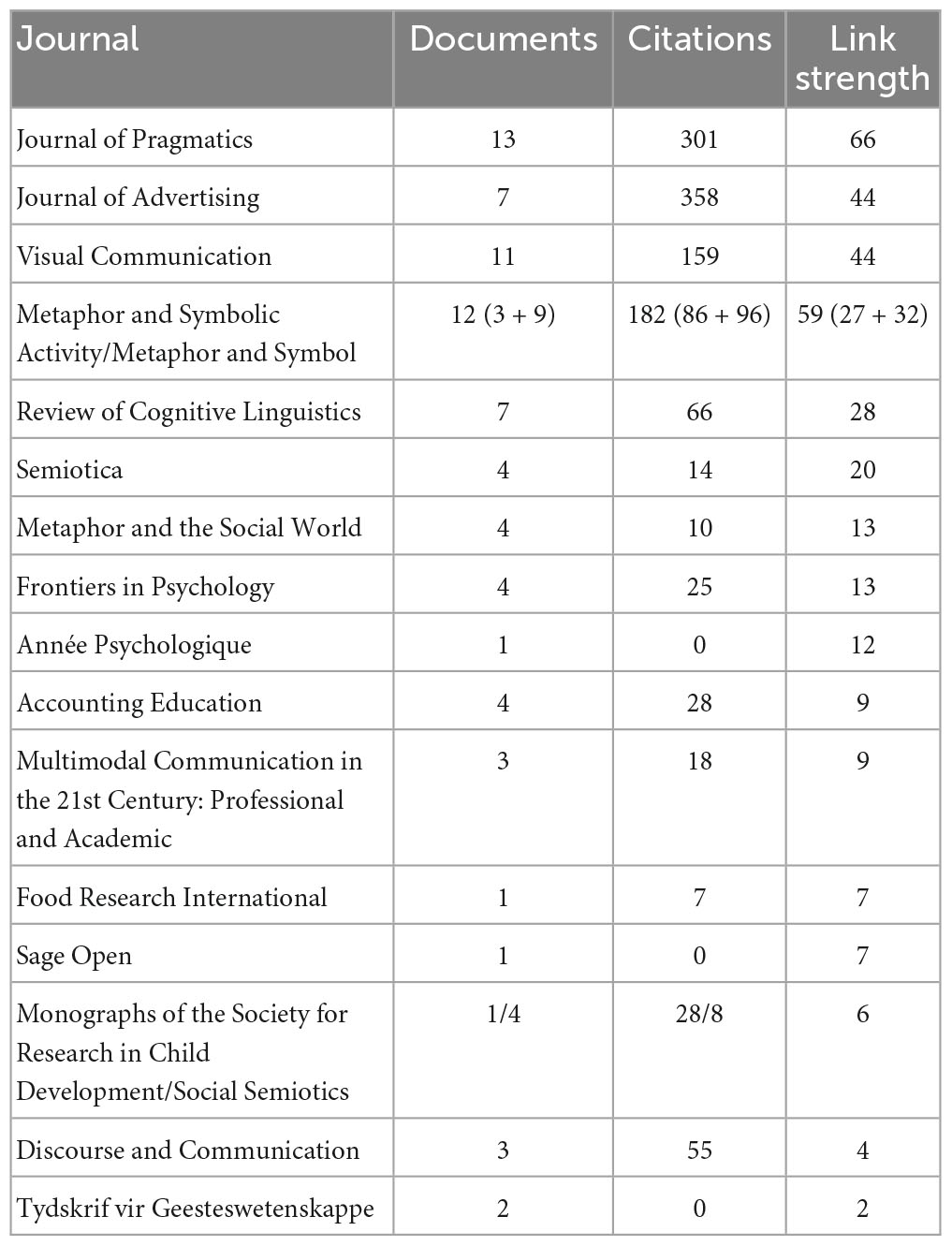

The 3271 articles or reviews that were examined in this study were published in a number of journals. Table 1 lists the 10 journals that published the highest number of papers in this area of research. With 116 publications on metaphor processing, Metaphor and Symbol , the only SSCI-indexed journal publishing works on metaphor research, was in first place among journals in terms of the number of publications. Frontiers in Psychology and Journal of Pragmatics were in second and third places, with 98 and 71 publications, respectively. The majority of the top 10 journals, as seen in Table 1 , are in the fields of psychology or neuroscience. When considering a submission, metaphor-processing researchers might use Table 1 to select appropriate journals for their papers.

The 10 authors having the highest number of publications in metaphor processing are listed in Table 2 . The author with the most papers published on metaphor processing was Mashal (36), followed by Faust (28) and Gibbs (26).

Table 3 lists the 10 institutions having the highest number of published works in metaphor processing. The University of California is at the top of this list with 131 publications in total, followed by the University of London with 76 articles and Bar Ilan University with 64 articles (Table 3 ).

Document co-citation analysis

A fundamental measure used by academic communities to assess the impact of a publication is the frequency of citations. The value of a published work and its impact on the field is at least partly dependent on the number of works that have been cited. We can identify the important documents in a knowledge domain by analyzing document co-citations. CiteSpace is an efficient tool that can conduct such analysis.

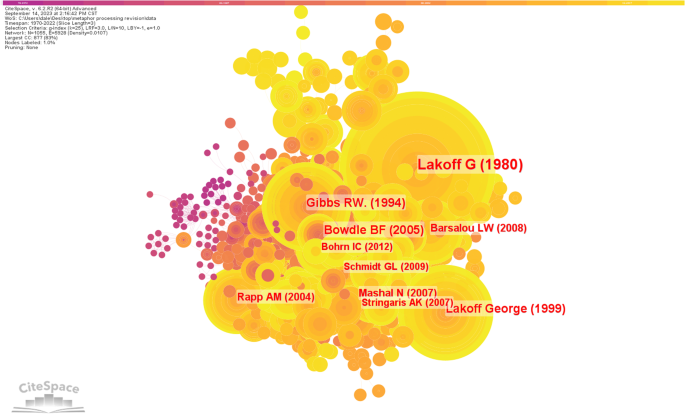

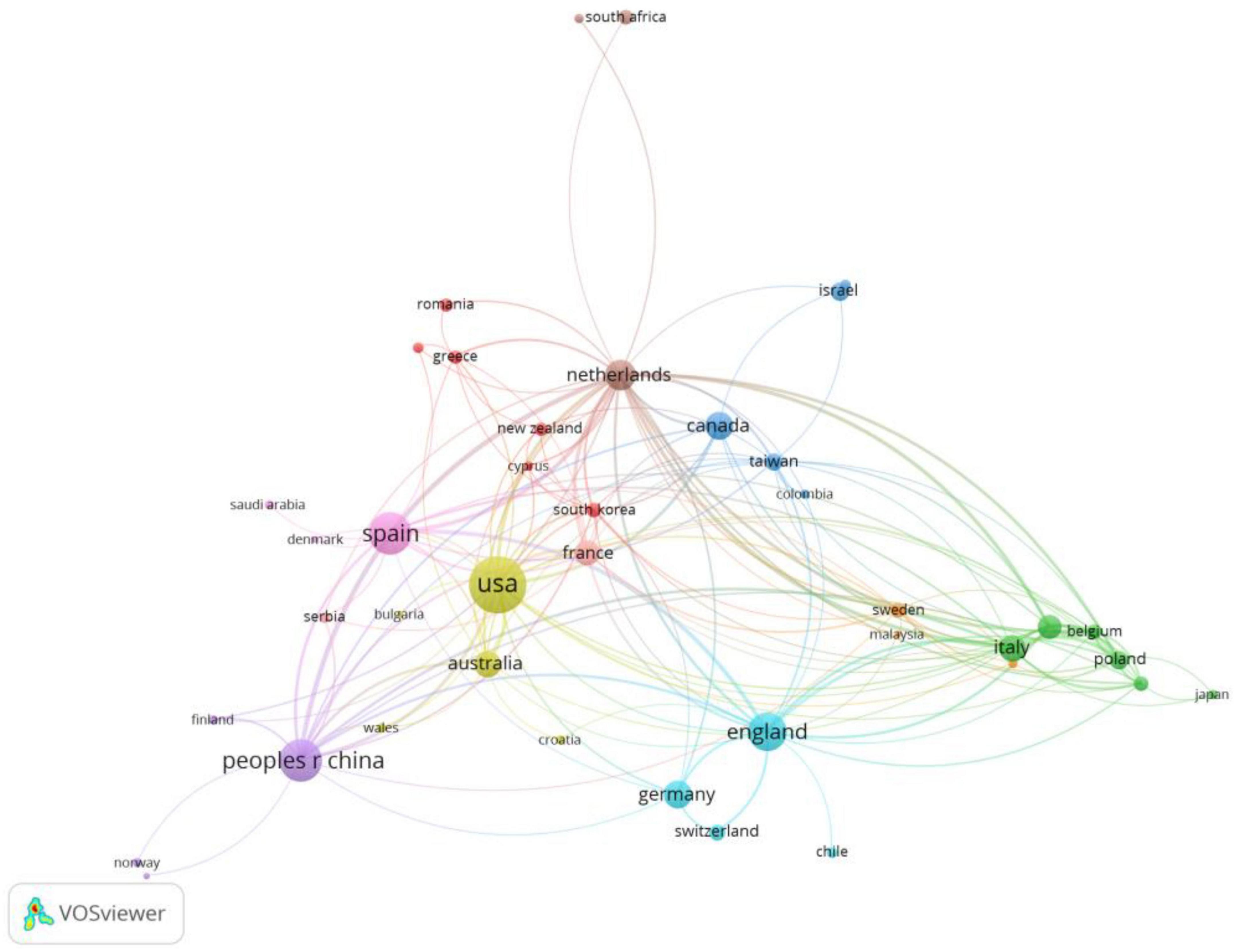

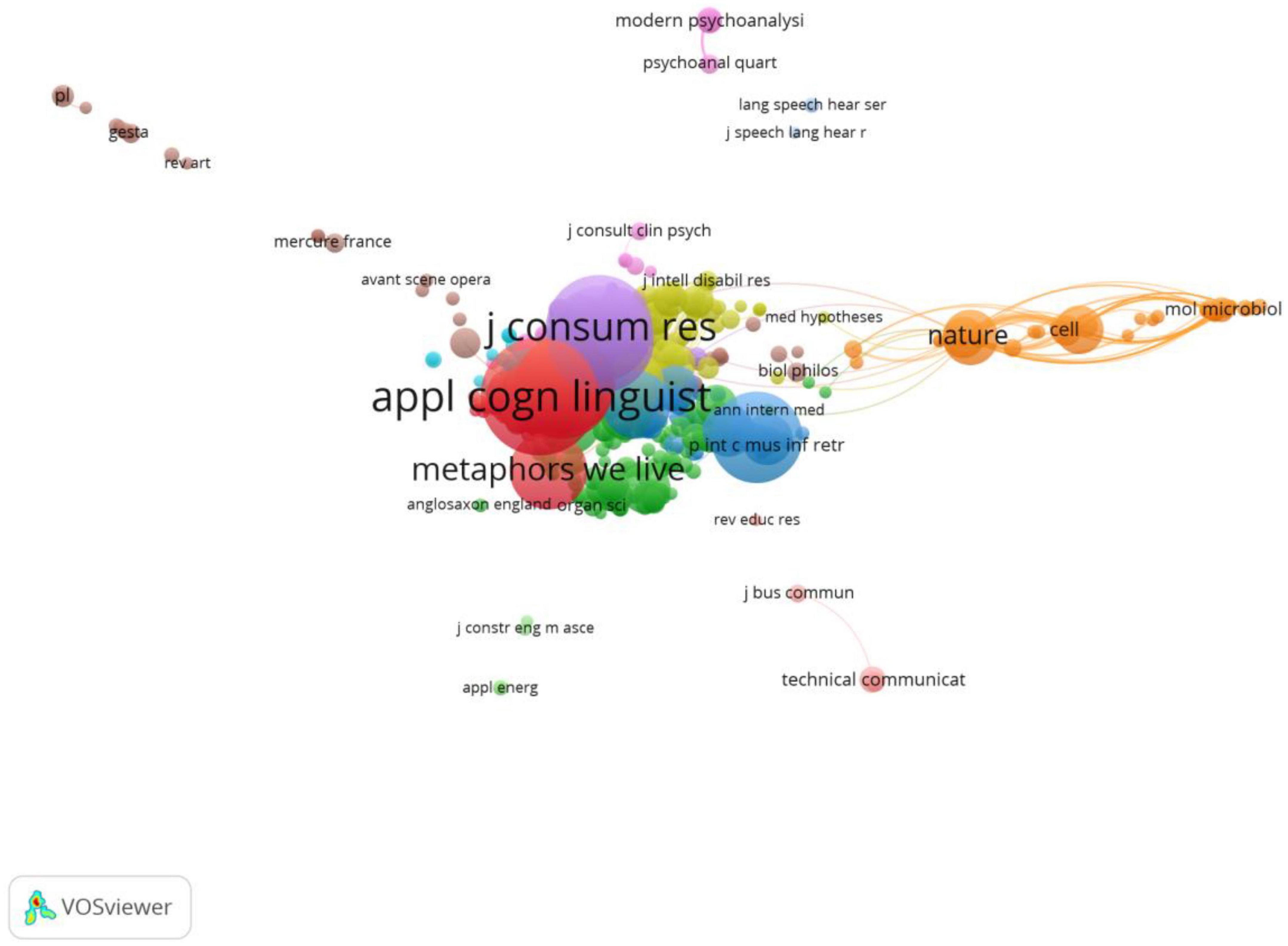

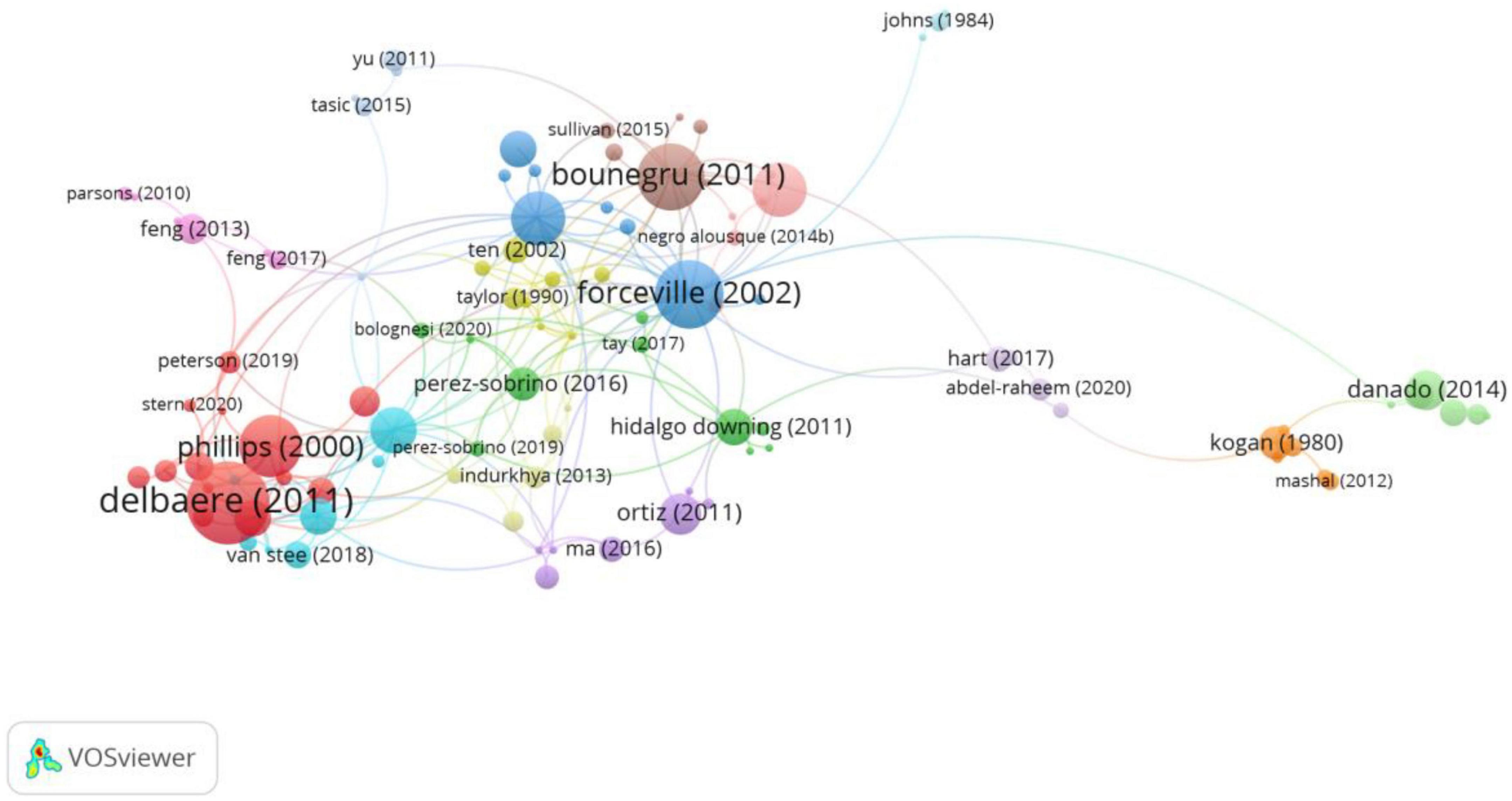

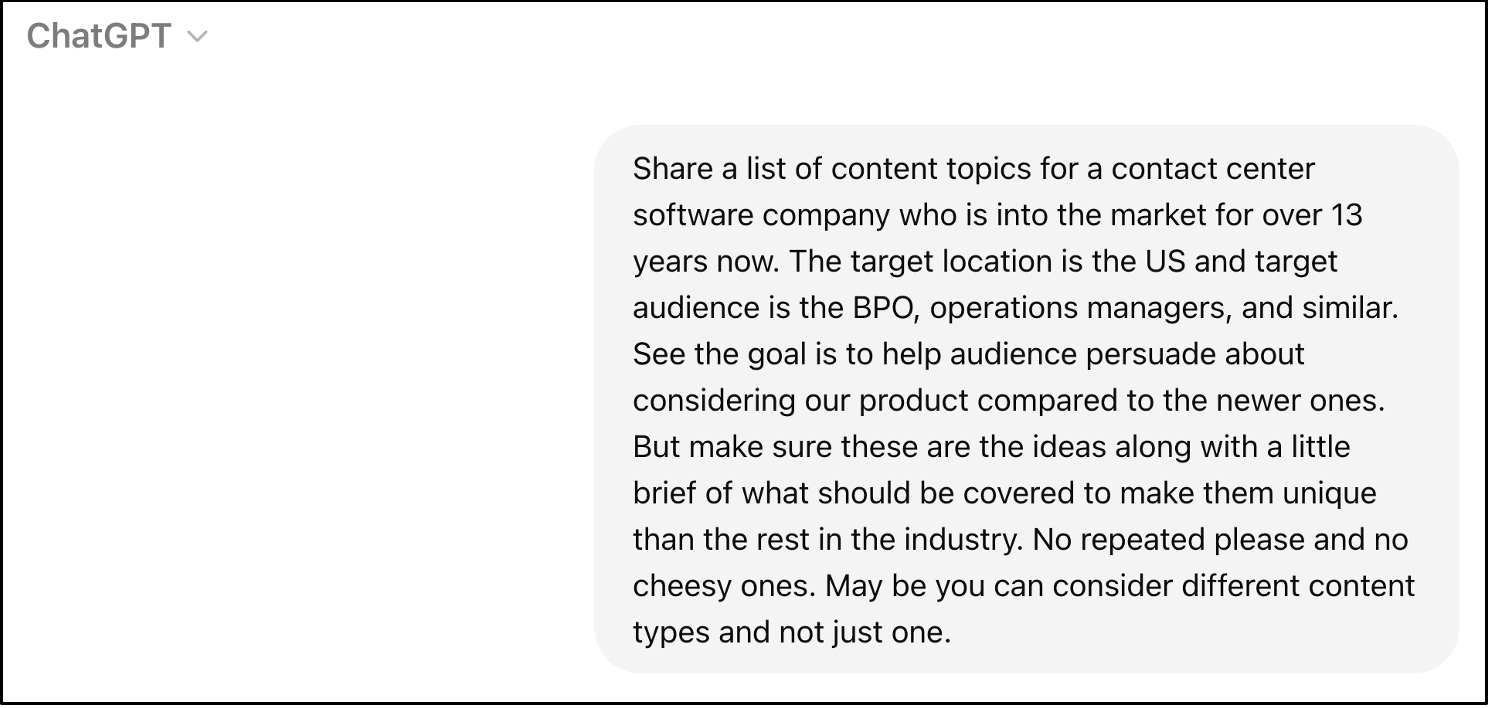

We analyzed document co-citations of 3271 publications collected from the WoS. We used CiteSpace to visualize the 3271 bibliographic recordings from 1970 to 2022. The top 50 papers having the highest number of citations in each 3-year were chosen using a time slice of three years. In order to include all the references cited in those documents regardless of when they were published, we set the Look Back Years (LBY) parameter to −1. Cutting off long-range citation linkages had a positive impact on the clarity of the results; it could increase the clarity of the network structure because long-distance links frequently go hand in hand with a spaghetti-like network. The results are shown in Fig. 2 . The cited publications and co-citation relationships across the entire data set were represented by 1055 distinct nodes and 5928 linkages, respectively. The top 10 articles in the area of metaphor processing research are shown in Table 4 .

The diagram of document co-citations reveals the top 10 most cited articles among the 3271 publications collected from the WoS.

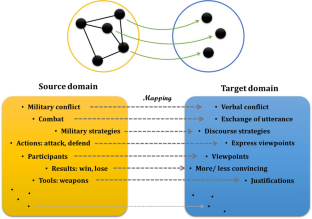

Totally, between 1970 and 2022, 39 documents were cited more than 50 times. The top three most-cited publications in the world’s publications related to metaphor processing are classic books about Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) in general, not about metaphor processing. The work that has received the most citations is “ Metaphors we Live by ” authored by Lakoff and Johnson ( 1980 ). This frequently cited book was a landmark that revolutionized research on metaphor processing. It contends that metaphor is a way of thinking, not just a rhetorical instrument. To put it simply, our conceptual system is fundamentally metaphorical. In contrast to earlier works that looked at metaphor as a purely linguistic figure of speech, this book emphasizes the conceptual nature of metaphor. It defines metaphor as a conceptual process in which a source domain is mapped into a target domain. For example, the conceptual metaphor ARGUMENT IS WAR, in which “argument” is the target and “war” is the source, can be used to explain a statement like “I defended my argument.” Since its introduction in 1980, Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) has gained popularity across various disciplines. The second-most quoted work is also written by Lakoff and Johnson ( 1999 ). This book challenged the Western traditional philosophy by proposing Embodied Philosophy based on the premise that our actions and our languages are based on our bodily experiences. Embodied Philosophy contends that abstract concepts are largely metaphorical. Embodied Philosophy is thus considered as the philosophical basis of Cognitive Linguistics. The third most cited document is a monograph by Gibbs ( 1994 ). Gibbs illustrates that human cognition is inherently poetic and that figurative imagination is central to how we comprehend ourselves and our surroundings. It challenges the traditional understanding of the mind by demonstrating how figurative characteristics of language reflect the poetic structure of the mind. Psychology, linguistics, philosophy, anthropology, and literary theory ideas and research are utilized to demonstrate fundamental ties between the poetic structure of the mind and daily language use. This monograph discusses methods and findings of psycholinguistic and cognitive psychology research to assess current philosophical, linguistic, and literary theories of figurative language. CMT aroused the interest of scholars from different disciplines such as linguistics, cognitive science, neuroscience, and psychology. Scholars in neurolinguistics and psycholinguistics are particularly interested in the cognitive processing of metaphors.

The other publications in Table 4 are not about metaphor in general but about metaphor processing in particular. In an article entitled “An fMRI investigation of the neural correlates underlying the processing of novel metaphoric expressions”, Mashal et al. ( 2007 ) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate the neural networks involved in the processing of related pairs of words that formed literal, novel, and conventional metaphorical expressions. Four different kinds of linguistic expressions were read by the participants, who then determined the relation between the two words (metaphoric, literal, or unrelated). The results showed that the degree of meaning salience of a linguistic expression, rather than literality or nonliterality, modulated the degree of left hemisphere (LH) and right hemisphere (RH) processing of metaphors. This supported the Graded Salience Hypothesis (GSH, Giora, 1997 , 2003 ), which predicts a selective RH involvement in the processing of novel and nonsalient meanings. In this study, the salient interpretations were represented by conventional metaphors and literal expressions, whereas the nonsalient interpretations were represented by novel metaphorical expressions. Right posterior superior temporal sulcus, right inferior frontal gyrus, and left middle frontal gyrus showed considerably stronger activity when the novel metaphors were directly compared to the conventional metaphors. These findings back up the GSH and point to a unique function of the RH in the processing of novel metaphors. Additionally, verbal creativity may be selectively influenced by the right PSTS.

In order to look into the neural substrates underlying the processing of three different sentence types, Stringarisa et al. ( 2007 ) combined a novel cognitive paradigm with event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging (ER-fMRI). Participants were required to read sentences that were either metaphorical, literal, or meaningless before deciding whether or not they made sense. The results of this experiment showed that various types of sentences were processed by various neural mechanisms. Both meaningless and metaphorical sentences activated the left inferior frontal gyrus (LIFG), but not literal sentences. Furthermore, despite the lack of difference between reaction times of literal and metaphoric sentences, the left thalamus is activated only in deriving meaning from metaphoric utterances. The authors attribute this to metaphoric interpretation’s flexibility and ad hoc concept formation. Their findings do not support the idea that the right hemisphere is primarily involved in metaphor comprehension, in contrast to earlier studies.

The two publications mentioned above used new research methods, such as fMRI and ER-fMRI. Additional research methods, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) by Pobric et al. ( 2008 ) and positron emission tomography (PET) by Bohrn et al. ( 2012 ), were also used in other highly cited papers.

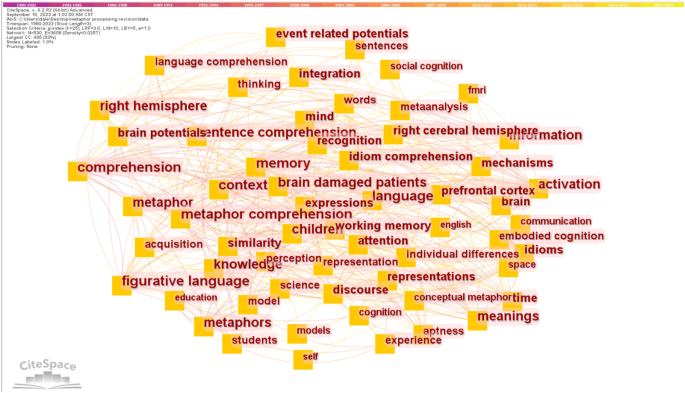

Co-occurring terms analysis

Keywords of any paper present its theme and some kind of summary of the subject that is going to be discussed in it. The occurrence of two keywords in a piece of writing indicates that these words are closely related to one another in the content of the work. The prevailing view is that if two or more terms appear together more frequently, they are more closely related. Betweenness Centrality is one of the functions of CiteSpace that specifies the strength of the relation between two or more terms. This gives us the ability to predict the occurrence of a given term with other terms even in other related topics. If a keyword displays a high Betweenness Centrality value, the keyword may be very significant. In this study, the research areas and dominant topics can be determined utilizing keyword co-occurrence analysis.

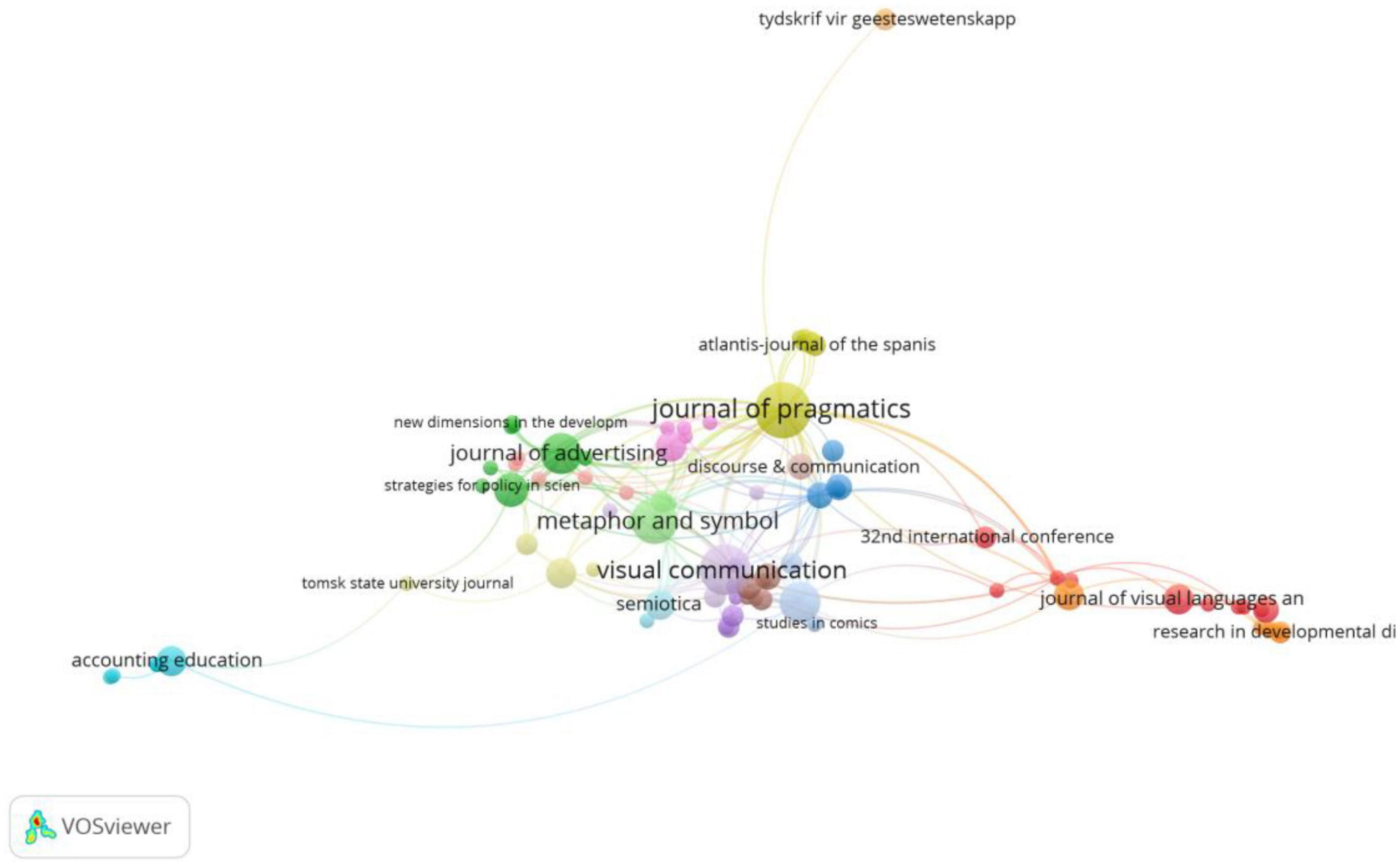

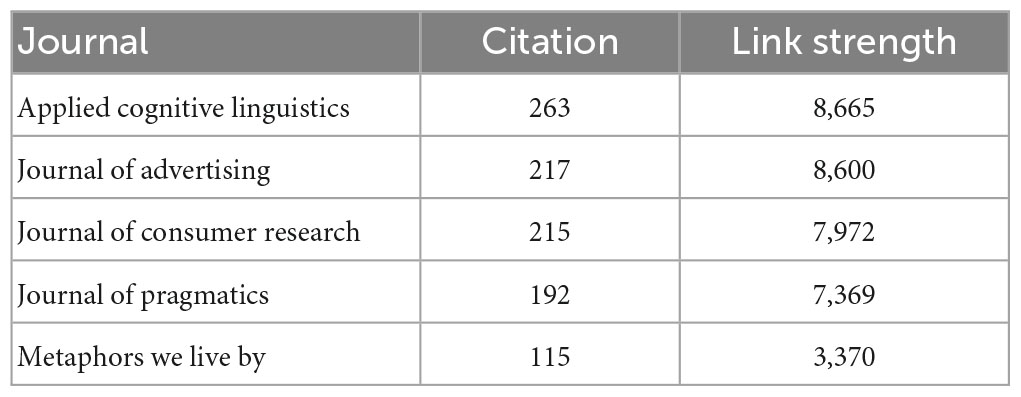

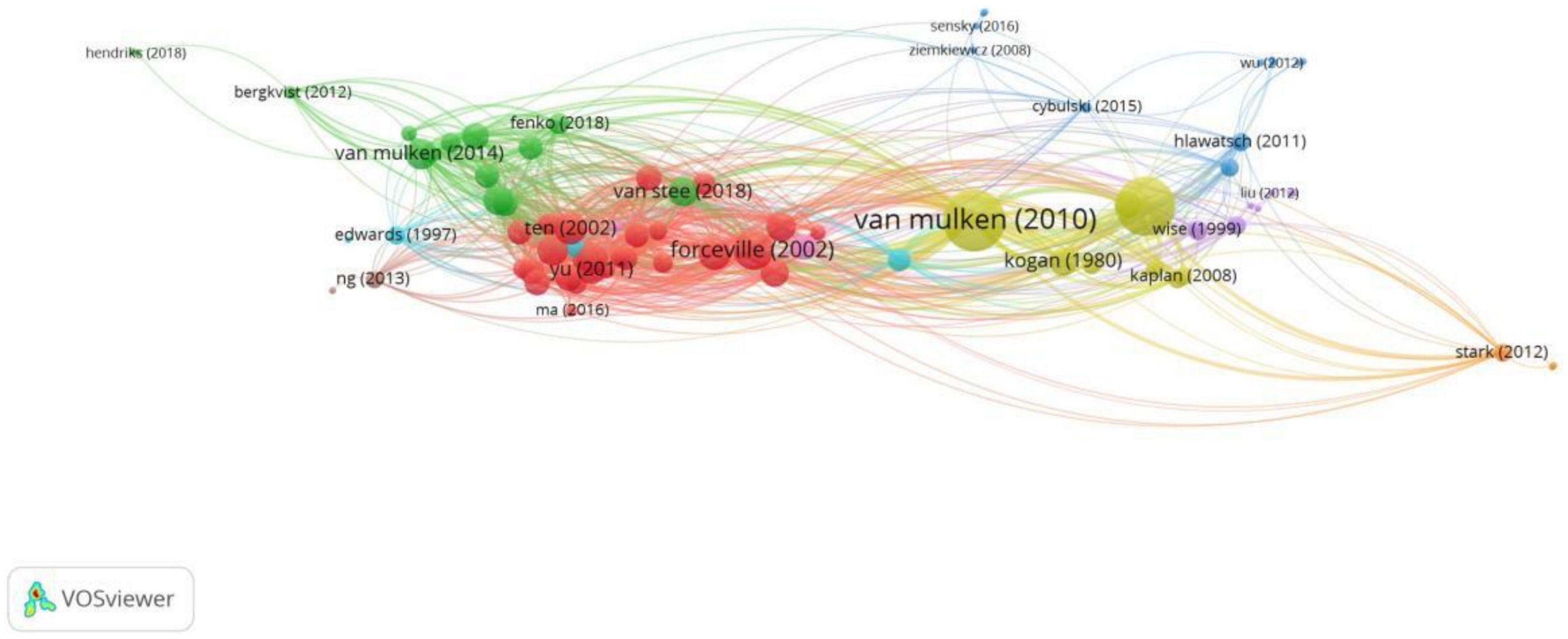

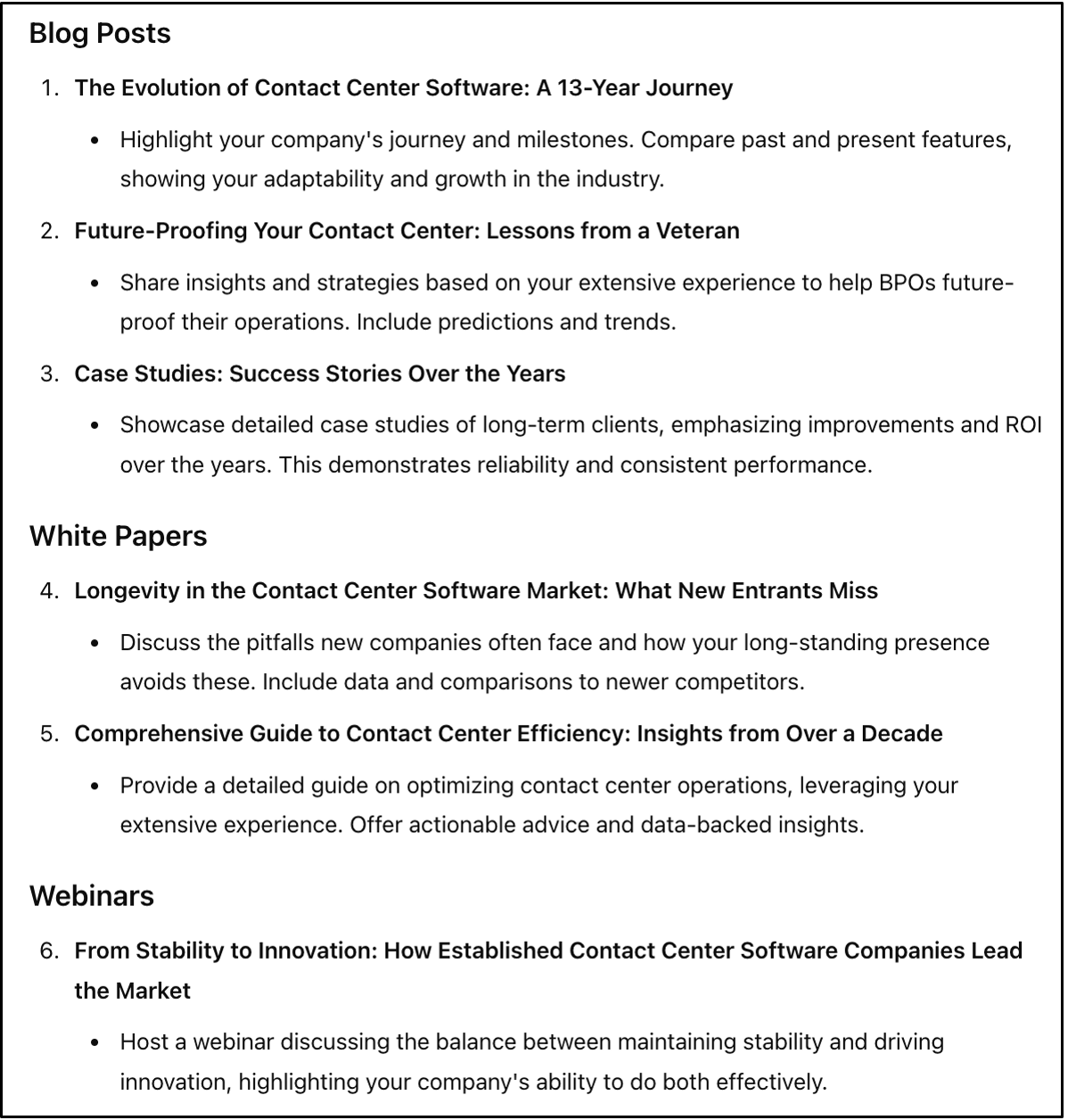

We analyzed the keywords to identify the terms and phrases that had co-occurred in at least two separate publications. Highly-frequent terms can show hotspots in a specific field of research (Chen, 2004 ). In this study, we chose the slice length of 3 years, and we set the LBY to 5 years. The results showed language, comprehension, metaphor, figurative language and context were the top 5 key terms having the highest frequencies. The network of related keywords is shown in Fig. 3 , and the terms with a frequency of more than 40 are listed in Table 5 .

The keyword co-occurrence network diagram reveals the most popular keywords of metaphor processing research.

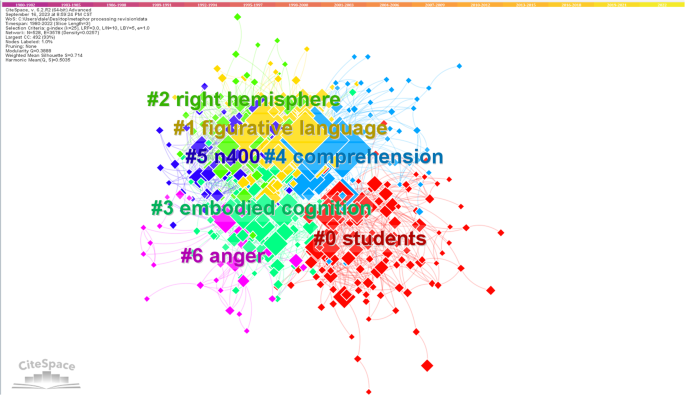

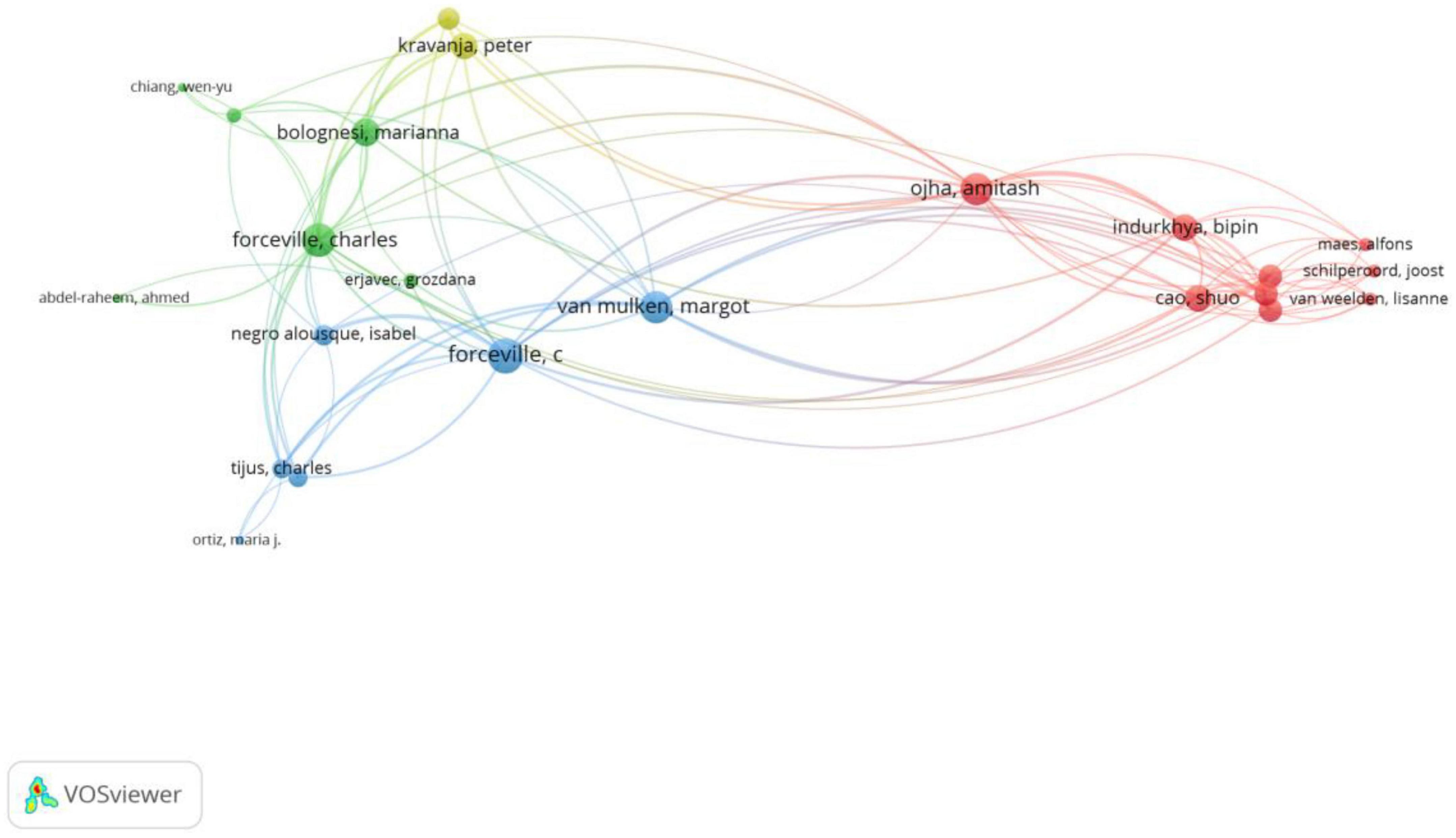

Cluster interpretations

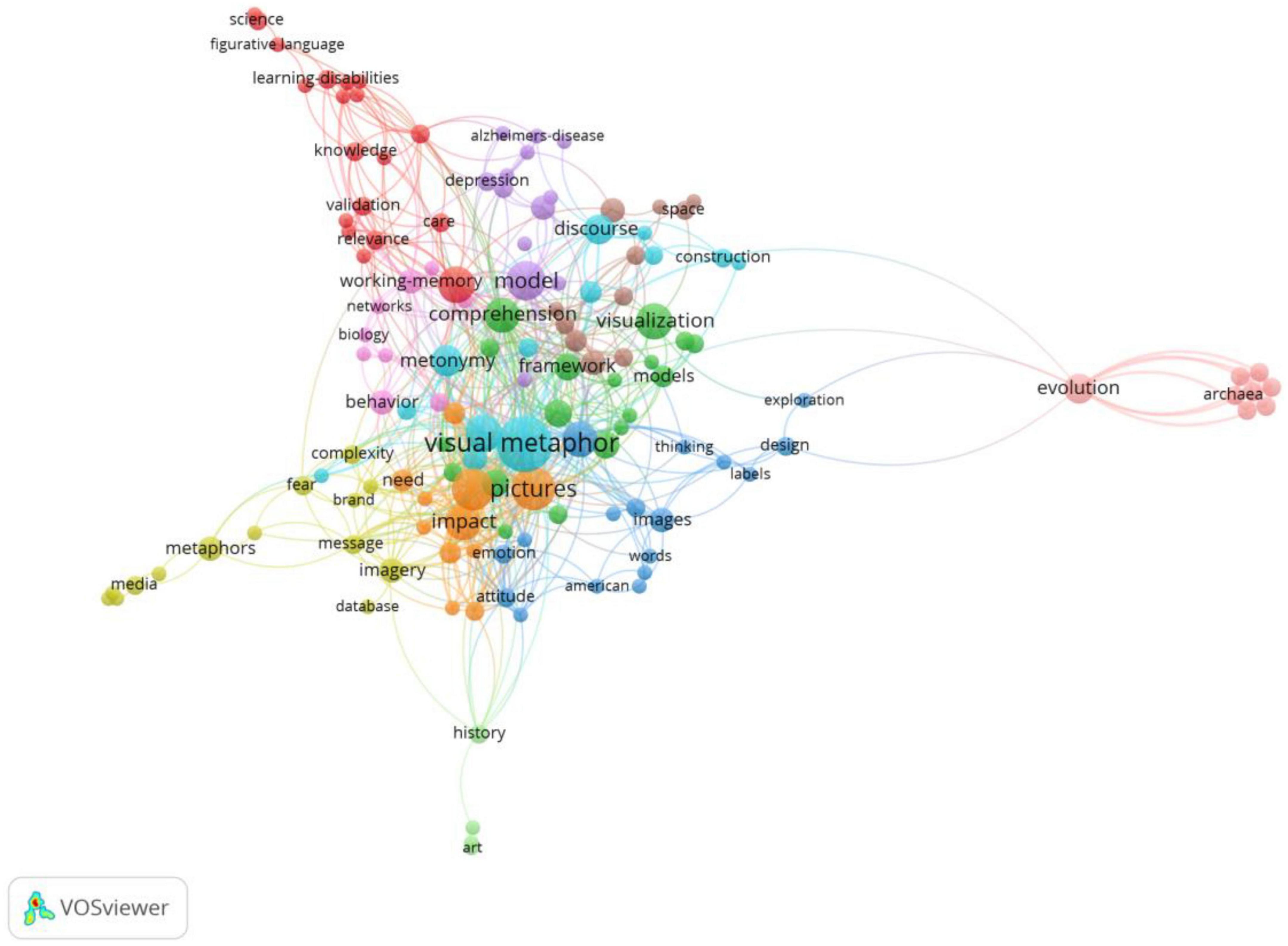

We used CiteSpace to perform a cluster analysis on the basis of keyword co-occurrences. Totally, 528 nodes in the co-citation network with a 3-year time slice were obtained from the analysis. The seven greatest clusters in the research area of metaphor processing are displayed in Fig. 4 . Warmer colors represent more current research subjects, whereas cooler colors represent older research topics in the clusters.

The network diagram of the keyword co-occurrence cluster reveals the most significant clusters of metaphor processing research.

Table 6 shows the top 7 clusters of keywords in metaphor processing research. It is obtained by using index terms as labels for clusters. Also, the clusters were shown by log-likelihood ratio (LLR). The top 7 clusters are named students, figurative language, right hemisphere, embodied cognition, comprehension, N400 , and anger .

Cluster #0, as the largest cluster, is labeled as ‘students’. For native speakers, using and understanding metaphors is simple. However, understanding figurative statements might be challenging for non-native speakers. Littlemore et al. ( 2011 ) found that at a British university, second-language learners had trouble understanding 40% of metaphorical terms that were easily understood by native speakers. Results of another study showed that second-language learners tended to use metaphors incorrectly and in the wrong contexts (Kathpalia and Carmel, 2011 ). It may be challenging for second-language speakers to comprehend and generate metaphors since the metaphorical meaning of a term is developed in the social and cultural context of native speakers. Metaphorical expressions that are easily and automatically understandable for native speakers of a certain language may not be easily interpretable for second-language speakers of that language due to not having enough exposure to that language and culture (Kecskes, 2006 ). Therefore, one of the main concerns for second-language teachers is to enhance second-language learners’ ability in understanding metaphoric language and to use it efficiently in the cultural context of the second language. As a result, there is a lot of discussion in metaphor research about how to improve students’ ability in using metaphors. For instance, Hu et al. ( 2022 ) performed a randomized controlled trial to assess how metaphors affected the symptoms of anxiety in Chinese graduate students.

Cluster #1 is labeled as ‘figurative language’. This cluster shows that two key components of executive functions (working memory and inhibition) could play significant roles in figurative language processing. Since working memory holds information for a short period of time, it plays an active role in discourse comprehension. Therefore, this component of executive functions helps the individual use discourse clues and contextual information in the process of metaphor interpretation. Contextually relevant information and metaphorically relevant information are put together (Wilson and Sperber, 2012 ), enabling the individual to extract the intended metaphorical meaning from an expression. This is done by the active involvement of working memory. Also, the role of inhibition, as another component of executive functions, has been documented in many studies (e.g., Glucksberg et al., 2001 ). These two components can be in close interaction with one another in the process of metaphor comprehension.

Cluster #2 is labeled as ‘right hemisphere’ by LSI test (Chen et al., 2010 ). This cluster shows that functional magnetic resonance imaging has been a common technique in research on the role of the right hemisphere in metaphor processing. Over the past 20 years, researchers in the fields of neurolinguistics and psycholinguistics have intensively studied the role of hemispheres in metaphor processing. Some scholars have hypothesized that the right hemisphere (RH) may have a special role in the processing of metaphorical language. However, many behavioral studies (e.g., Bohrn et al., 2012 ; Faust and Mashal, 2007 ; Mashal et al., 2007 ; Mashal and Faust, 2008 ) have evidence suggesting that the processing of familiar or conventional metaphors requires more left-lateralized processing, compared to the processing of unfamiliar metaphors. Additionally, bilateral processing of traditional metaphors was also supported by the findings of several studies (e.g., Bambini et al., 2011 ; Diaz et al., 2011 ). These results lend credence to the Graded Salience Hypothesis (GSH), according to which semantic salience plays a key role in metaphor processing (Giora, 1997 , 2003 ). According to this hypothesis, conventional, frequent, recognizable, and prototypical meanings are simpler to process than less-prominent meanings. Therefore, the meaning of a conventional metaphor is more salient and more accessible than its literal counterpart. On the other hand, in a novel metaphor, the literal meaning is more evident and the figurative meaning is disclosed later with the support of contextual clues. The GSH claims that unlike novel metaphors, whose meanings are acquired through integration and inferential processes, conventional metaphors’ prominent meanings are stored in the mental lexicon. The GSH also predicts that the left hemisphere (LH) is more active in comprehending conventional and salient metaphorical meanings, while the right hemisphere (RH) is more active in comprehending innovative and non-salient metaphorical meanings (Giora, 2003 ).

Cluster #3 is labeled as ‘embodied cognition’. Theories of embodied cognition challenge the traditional theories of cognition that are based on amodal symbols. These theories offer new perspectives on human cognitive processes. These theories hold that simulation, situated action, and bodily states play a crucial role in cognitive processes. Cognitive linguistics gave rise to some of the first set of theories that supported grounded cognition. Theories of embodied language processing emphasized the role of body, situation, and simulation in language as opposed to the amodal theories of grammar that emerged in the Cognitive Revolution (e.g., Chomsky, 1957 ). The study of embodiment has caught the interest of researchers working in traditional cognitive science, who have started to incorporate the ideas of embodiment in their works. The role of embodiment in language processing was developed and promoted by George Lakoff, Mark Johnson, Mark Turner, and Rafael Núñez based on advancements in the field of cognitive science (Lakoff, 1987 ; Lakoff and Johnson, 1980 ; Lakoff and Johnson, 1999 ; Lakoff and Turner, 1989 ; Lakoff and Núñez, 2000 ). In their studies, they have found evidence suggesting that people draw on their knowledge of everyday physical phenomena to comprehend concepts. According to theories of embodiment and embodied language processing, cognition and cognitive processes are based on the knowledge that comes from the body. There has been an increase in interest in studying the relationship between embodied cognition and language over the last four decades. According to theories of embodied cognition, when people understand words, their sensorimotor systems are engaged in simulating the concepts the words refer to (Jirak et al., 2010 ). Lakoff and Johnson’s ( 1980 , 1999 ) conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) is one of the most prominent theories of embodied cognition. This theory holds that situated and embodied knowledge serves as the metaphorical foundation for abstract concepts. Specifically, Lakoff and Johnson ( 1980 ) argued that abstract concepts are metaphorically understood in terms of concrete concepts with the support of sensorimotor systems. Many studies in various languages have demonstrated how individuals frequently use physical metaphors to discuss abstract concepts. Literature also uses a lot of these metaphors (e.g., Turner, 1996 ). A crucial question is whether these metaphors only reflect linguistic convention or whether they genuinely represent how we think (e.g., Murphy, 1997 ). There is mounting evidence that these metaphors are essential to our thought (e.g., Boroditsky and Ramscar, 2002 ; Gibbs, 2006 ).

Cluster #4 is labeled as ‘comprehension’. One of the keywords in this cluster is the term context . This supports the key role of context in the process of metaphor comprehension. Context of a conversation can provide some information that contributes to metaphor processing (e.g., Steen et al., 2010 ). It helps the individual disregard non-relevant literal meanings and keeps the metaphorically relevant information to derive the intended metaphorical meaning.

Cluster #5 is labeled as ‘N400’. The N400 is a part of time-locked EEG signals called event-related potentials (ERP). It is a negative-going deflection that normally peaks over centro-parietal electrode sites and occurs 400 ms after the stimulus begins, though it can also last between 250 and 500 ms. The N400 is a typical brain response to words and other meaningful (or potentially meaningful) stimuli, such as visual and auditory words, sign language signs, images, faces, environmental sounds, and odors (Kutas and Federmeier, 2000 , 2011 ). During the past 4 decades, ERP has been one of the techniques most frequently employed in cognitive neuroscience research to examine the physiological correlates of sensory, perceptual, and cognitive activities associated with information processing (Handy, 2005 ). ERP is also widely employed in metaphor processing studies, along with other imaging techniques such as fMRI, PET, and MEG.

Cluster #6 is labeled as ‘anger’. This cluster includes the key terms figurative language and eye tracking . This suggests that the metaphoric conceptualization of some emotional states and emotional terms such as anger can be reflected in eye movements. Interestingly, some works have suggested that this can happen not only for emotion-related concepts but also for other categories of abstract concepts that are metaphorically described in terms of movement (e.g., Singh and Mishra, 2010 ).

This clustering of keywords offers an organized and clear picture of key concepts that have been involved in various lines of research on metaphor processing. This clustering shows which lines of investigation have had a strong relationship with one another in research on metaphor processing. Therefore, the suggested clustering of keywords in metaphor comprehension offers a map for research on metaphor processing. This can be a guiding tool for researchers to have a clearer idea and organized map of how various lines of research on metaphor processing intersect with one another.

Discussion and implication for future studies

Over the past 50 years, metaphor processing has been a widely discussed topic among scholars in various disciplines, particularly researchers in neurolinguistics and psycholinguistics. Through the aforementioned document co-citation analysis, co-occurring word analysis, and cluster visualization which were done by CiteSpace, this study showed that research on metaphor processing has mainly focused on hemispheric processing of metaphors, metaphor comprehension, the embodied cognition basis of metaphor processing, behavioral-experiments study, ERP method and other techniques (fMRI, PET, and MEG, etc.), and the comparision of metaphor processing of adults with children.

Results of this study showed that research projects on metaphor processing are mainly conducted by experiments, including behavioral experiments, ERPs, and other imaging techniques such as fMRI, PET, and MEG. However, there is some conflicting evidence in the research findings. For instance, many studies have shown no statistically significant difference between ASD and TD groups in the understanding of metaphors and figurative language (Hermann et al., 2013 ; Kasirer and Mashal, 2014 ; Mashal and Kasirer, 2011 ; Norbury, 2005 ). These results suggest that factors other than disease-specific traits may account for the differences in results between studies. In the past, it has been discovered that group matching strategy and general language proficiency can account for part of the between-study variability in figurative language comprehension (Kalandadze, et al., 2018 ). However, further pertinent variables need to be examined in order to fully explain the observed variabilities. One reason for these different results may be due to the different theories the researchers adhere to. Another reason for mixed results may be due to the task properties of those experiments.

As for the theories on metaphor processing, there are two models that are widely used to study the processing of metaphors, namely, the Direct Access View (Gibbs, 1984 , 1994 ; Gibbs and Gerrig, 1989 ) and the Graded Salience Hypothesis (Giora, 1997 , 2003 ). According to the Direct Access View, in metaphor processing, the non-literal meaning of the metaphor can be directly processed, without inferring and discarding the literal meaning in an initial stage. Based on the Direct Access View, the Parallel Hypothesis was proposed, which holds that understanding figurative language is not different from that of literal language. Therefore, it is not necessary to assume any special cognitive mechanisms to process figurative language such as metaphors (Glucksberg et al., 1982 ). However, the Parallel Hypothesis can only hold if the literal and figurative meanings are fully understood. When the literal and figurative meanings are inconsistent, the coexistence of literal and figurative meanings cannot be explained by the Parallel Hypothesis. This does not mean that the literal meaning is abandoned before it is processed. Rather, the context facilitates the understanding of the inconsistent literal meanings. Therefore, the Direct Access View also supports the Context-dependent Hypothesis, which holds that we have a direct understanding of the figurative meanings with the help of sufficient contextual information.

Another theory on metaphor processing that is widely used to support metaphor research findings is the GSH (Giora, 1997 , 2003 ). As mentioned, the GSH holds that metaphor processing is influenced by the degree of semantic prominence. That is, conventional, frequent, recognizable, and prototypical meanings are easier to assimilate than less-salient meanings. One prediction of GSH is that the right hemisphere (RH) is more active in perceiving creative and non-salient metaphorical meanings, while the left hemisphere (LH) is more active in comprehending conventional and salient metaphorical meanings (Giora, 2003 ).

While the Direct Access View holds that metaphorical meaning is directly accessible, the Graded Salience Hypothesis assumes that metaphorical meaning is activated after the activation of the salient literal meaning. Depending on which theoretical framework is taken for certain research, different and conflicting results may be obtained. However, it should be noted that metaphor processing is a complex phenomenon and a large number of factors may be involved in it. Therefore, a single theory may not be able to describe all aspects of metaphor processing for all types of metaphors. The Direct Access View can describe the processing of highly conventional metaphors and idiomatic expressions. In daily conversations, people can easily produce and understand conventional metaphors and idiomatic expressions automatically. But, in some cases, this theory fails to describe the processing of novel metaphors. On the other hand, the Graded Salience Hypothesis may provide a better picture of how novel metaphors are processed. Therefore, in order to explain the discrepancies in research findings, we may need to take broader frameworks. When a single theoretical framework cannot explain discrepancies, two complementary frameworks can be taken and combined to explain and reconcile the conflicting results. Furthermore, a given theoretical framework may be more applicable to certain groups of people. For example, the GSH may be more applicable to ASD than the AD group, while the Direct Access View may be more applicable to TD than the ASD group. In other words, types of metaphors (e.g., conventional vs. novel metaphor), features of comprehenders (ASD vs. TD group), and possibly many other factors determine which theory of metaphor processing is most applicable. Putting various theoretical frameworks together and trying to make broader theoretical frameworks is a potential solution for responding to some questions that have not been answered yet.

Another reason for the differences in results between studies on metaphor processing may be the task properties of those experiments. There is a consensus in the literature of behavioral and neuroimaging studies that factors such as clinical populations, task characteristics, response format (i.e., multiple-choice vs. verbal explanation task), and lack of linguistic context can affect participants’ capacity to interpret metaphors (Pouscoulous, 2011 , 2014 , Rossetti et al., 2018 ). For instance, when assessed with an act-out rather than a verbal explanation task, children with TD demonstrate earlier proficiency in metaphor understanding. This may be because verbal and other types of tasks place different demands on a child’s linguistic and cognitive abilities (Pouscoulous, 2011 ). A similar explanation for how people with ASD perform metaphor tasks is based on response format. For instance, people with ASD may grasp metaphors similarly to people with TD, but they may have more trouble conveying them orally because of problems with expressive language (Kwok et al., 2015 ). Other aspects of the metaphors may also play a role, such as the amount and type of contextual information that is available to interpret the expression, or the degree of familiarity with the expression (Pouscoulous, 2011 , 2014 ). By combining the preceding studies utilizing the techniques of systematic review and a meta-analysis, Kalandadze et al. ( 2019 ) collated the knowledge that is currently available concerning task properties. Their aim was to find out how task properties affect metaphor comprehension ability in people with ASD compared to people with TD. They discovered that previous studies had used various kinds of materials and tasks that were either created by the researchers who designed the studies or were adapted from earlier research. The possible impact of the task properties was rarely taken into account in the previous studies, despite the fact that the task properties varied widely. Degree of individual’s familiarity with the metaphor (conventionality/novelty), degree of complexity of syntactic structure, linguistic and non-linguistic context (physical context) of the metaphoric expression, modality of stimulus (e.g., audio, visual), response format (verbal or non-verbal), and timing of the task are important task properties that can affect results of studies and their interpretations. Therefore, in order to obtain more accurate results, these factors need to be taken into account.

Implication for future studies

Based on the discussion in the section “Discussion”, we suggest that two issues deserve more consideration in future studies on metaphor processing. The first one is the theories that are employed to support the findings of metaphor processing studies. As different theories on metaphor processing may generate different conclusions, it is suggested that researchers discuss the results from different theoretical perspectives, rather than a single theory.

The second issue that merits more consideration is task properties. Task properties are important but have been neglected. The existing research on metaphor processing has paid little attention to the relevance of task properties in performance on metaphor comprehension tasks. Therefore, we contend that task properties including response format and linguistic features (i.e., metaphor familiarity, the syntactic structure of the metaphor, linguistic context, and stimulus modality) should be carefully considered in future investigations on metaphor processing. The systematic review and meta-analysis by Kalandadze et al. ( 2019 ) revealed that some task properties, including metaphor familiarity, are more frequently taken into account than others when determining the impact of a task. The least studied property in previous research is syntactic structure. Also, research on metaphor processing has not done a good job to examine the influence of contextual information on different groups of people. In future metaphor processing studies, these task properties merit additional consideration. When creating and reporting task properties in metaphor studies, researchers need to be extremely careful.

It should be noted that metaphor processing is a complex and multidimensional process. Therefore, in order to obtain a clear picture of various aspects of metaphor processing, researchers of various fields need to collaborate in interdisciplinary research projects. Neuroimaging data collected by neurolinguistics experts, behavioral data collected by researchers in psycholinguistics and cognitive science, and even corpus-based data can be combined to offer a broader picture of metaphor processing. Various types of evidence can complement each other and fill the gaps. This is a crucial point that should be considered in future research on metaphor processing.

As noted by Han et al. ( 2022 ), metaphor processing has been the most studied research area in metaphor research. Since the 1970s, how metaphors are processed in the brain has been extensively investigated by scholars in linguistics, neurolinguistics, and psycholinguistics. However, up to now, bibliometric tools like CiteSpace have not been used to systematically review literature on metaphor processing. In our study, a total of 3271 bibliometric recordings were collected from the Web of Science Core Collection. These documents had been published between 1970 and 2022. The descriptive analysis revealed a yearly increase in the number of publications, indicating that metaphor processing has caught the interest of academics from a variety of disciplines. Metaphor and Symbol , the sole SSCI-indexed journal devoted to metaphor research, took the first position among journals in terms of publishing yield with 116 publications on metaphor processing. Mashal, Faust, and Gibbs are the three most prolific authors in terms of publications on metaphor processing.

These bibliometric analyses through the CiteSpace software showed that language, comprehension, metaphor, figurative language , and context were the five most frequent keywords. Also, the most prominent clusters were students, figurative language, right hemisphere, embodied cognition, comprehension, N400 , and anger . These findings showed that research on metaphor processing has largely focused on the hemispheric processing of metaphors, metaphor comprehension, and embodiment in metaphor processing. Behavioral experiments, ERP and other techniques, such as fMRI, PET, and MEG were the common techniques in metaphor processing research. The current review through CiteSpace indicates that putting various theoretical frameworks together and trying to make broader theoretical frameworks is a potential solution for responding to some questions that have not been answered yet. This review also suggests that in future studies on metaphor processing, task properties such as response format and linguistic features should be carefully taken into account.

Although the current study aimed to be comprehensive within its defined scope, it was subject to some inevitable limitations. Firstly, being limited to WoS documents was one of the limitations of this study. Other databases such as Scopus, Google Scholar, Index Medicus, and Microsoft Academic Search were not included in this study. Secondly, publishers’ labeling of document types was not always correct. Some articles presented as reviews by WoS, for example, were not review papers at all (Yeung, 2021 ). Thirdly, we used only one scientometric instrument. Fourthly, while several prospective papers have recently been published, these studies were not acknowledged. Furthermore, because of obliteration, the citation count for some earlier published works was low.

Nonetheless, this study comprises a ground-breaking bibliometric assessment of global research on metaphor processing and provides a clear overview of global publications related to metaphor processing. Hence, it can be a helpful source for researchers interested in metaphor and metaphor processing. The results of this review have both theoretical and practical implications for the study of metaphor processing and metaphor in general.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JFRP5W .

Bambini V, Gentili C, Ricciardi E, Bertinetto PM, Pietrini P (2011) Decomposing metaphor processing at the cognitive and neural level through functional magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Res Bull 86:203–216

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barsalou W (2008) Grounded cognition. Annu Rev Psychol 59:617–645

Bohrn IC, Altmann U, Jacobs AM (2012) Looking at the brains behind figurative language—a quantitative meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on metaphor, idiom, and irony processing. Neuropsychologia 55:2669–2683

Article Google Scholar

Bowdle BF, Gentner D (2005) The career of metaphor. Psychol Rev 112(1):193–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.112.1.193

Boroditsky L, Ramscar M (2002) The roles of body and mind in abstract thought. Psychol Sci 13:185–188

Chen C (2004) Searching for intellectual turning points: progressive knowledge domain visualization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(Suppl 1):5303–5310

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chen C (2006) CiteSpace II: detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 57(3):359–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317

Chen C (2017) Science mapping: a systematic review of the literature. J Data Inf Sci 2(2):1–40. https://doi.org/10.1515/jdis-2017-0006

Article CAS Google Scholar

Chen C (2020) A glimpse of the first eight months of the COVID-19 literature on microsoft academic graph: themes, citation contexts, and uncertainties. Front Res Metr Anal 5:607286. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2020.607286

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chen C, Ibekwe-SanJuan F, Hou J (2010) The structure and dynamics of cocitation clusters: a multiple-perspective cocitation analysis. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 61(7):1386–1409. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21309

Chen C, Song M (2019) Visualizing a field of research: a methodology of systematic scientometric reviews. PLoS ONE 14(10):e0223994. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223994

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chomsky N (1957) Syntactic structures. Mouton, The Hague

Diaz MT, Barrett KT, Hogstrom LJ (2011) The influence of sentence novelty and figurativeness on brain activity. Neuropsychologia 49:320–330

Faust M, Mashal N (2007) The role of the right cerebral hemisphere in processing novel metaphoric expressions taken from poetry: a divided visual field study. Neuropsychologia 45:860–870

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gibbs RW (1984) Literal meaning and psychological theory. Cogn Sci 813:275–304

Gibbs RW (1994) The poetics of mind. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Google Scholar

Gibbs RW (2006) Embodiment and cognitive science. Cambridge University Press, New York

Gibbs RW, Gerrig RG (1989) How context makes metaphor comprehension seem “special”. Metaphor Symbol Activity 4/3:144–158

Giora R (1997) Understanding figurative and literal language: The graded salience hypothesis. Cogn Linguist 8:183–206

Giora R (2003) On our mind: salience, context, and figurative language. Oxford University Press

Glucksberg S, Gildea P, Bookin HB (1982) On understanding nonliteral speech: can people ignore metaphors. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav 21:85–98

Glucksberg S, Newsome MR, Goldvarg Y (2001) Inhibition of the literal: filtering metaphor-irrelevant information during metaphor comprehension. Metaphor Symbol 16(3-4):277–293. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327868MS1603&4_8

Han Y, Peng Z, Chen H (2022) Bibliometric assessment of world scholars’ international publications related to conceptual metaphor. Front Psychol 13:1071121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1071121

Handy TC (2005) Event related potentials: a methods handbook. Bradford/MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Hermann I, Haser V, van Elst LT, Ebert D, Müller-Feldmeth D, Riedel A, Konieczny L (2013) Automatic metaphor processing in adults with Asperger syndrome: a metaphor interference effect task. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 263(Suppl 2):S177–S187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-013-0453-9

Holyoak KJ, Stamenković D (2018) Metaphor comprehension: a critical review of theories and evidence. Psychol Bull 144(6):641–671. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000145

Hu J, Zhang X, Li R, Zhang J, Zhang W (2022) A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of metaphors on anxiety symptoms among Chinese graduate students: the mediation effect of worry. Appl Res Qual Life https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-022-10107-2

Jirak D, Menz MM, Buccino G, Borghi AM, Binkofski F (2010) Grasping language—a short story on embodiment. Conscious Cogn 19(3):711–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.06.020

Kalandadze T, Bambini V, Næss K (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on metaphor comprehension in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: do task properties matter? Appl Psycholinguist 40:1421–1454. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716419000328

Kalandadze T, Norbury C, Nærland T, Næss BK-A (2018) Figurative language comprehension in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analytic review. Autism 22:99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316668652

Kathpalia SS, Carmel HLH (2011) Metaphorical competence in ESL student writing. RELC J 42(3):273–290

Kasirer A, Mashal N (2014) Verbal creativity in autism: comprehension and generation of metaphoric language in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder and typical development. Front Hum Neurosci 8:615. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00615

Kecskes I (2006) On my mind: thoughts about salience, context and figurative language from a second language perspective. Second Language Res 22:219–237

Kertész A, Rákosi C, Csatár P (2012) Data, problems, heuristics and results in cognitive metaphor research. Language Sci 34(6):715–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2012.04.011

Kutas M, Federmeier KD (2000) Electrophysiology reveals semantic memory use in language comprehension. Trends Cogn Sci 4(12):463–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01560-6

Kutas M, Federmeier KD (2011) Thirty years and counting: finding meaning in the N400 component of the event-related brain potential (ERP). Annu Rev Psychol 62:621–647. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.131123

Kwok EYL, Brown HM, Smyth RE, Cardy JO (2015) Meta-analysis of receptive and expressive language skills in autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectrum Disord 9:202–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.008

Lakoff G, Johnson M (1980) Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lakoff G, Johnson M (1999) Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. Basic Books

Lakoff G, Turner M (1989) More than cool reason: a field guide to poetic metaphor. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Lakoff G (1987) Women, fire, and dangerous things: what categories reveal about the mind. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lakoff G, Núñez RE (2000) Where mathematics comes from. Basic Books

Laurette P (1971) Metaphoric process and metonymic process-consideration of poem by valery. Linguistics 66:34–55

Littlemore J, Chen PT, Koester A, Barnden J (2011) Difficulties in metaphor comprehension faced by international students whose first language is not English. Appl Linguist 32:408–429

Mashal N, Faust M (2008) Right hemisphere sensitivity to novel metaphoric relations: application of the signal detection theory. Brain Language 104:103–112

Mashal N, Faust M, Hendler T, Jung-Beemane M (2007) An fMRI investigation of the neural correlates underlying the processing of novel metaphoric expressions. Brain Language 100(2):115–126

Mashal N, Kasirer A (2011) Thinking maps enhance metaphoric competence in children with autism and learning disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 32:2045–2054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.012

Morsanyi K, Stamenković D, Holyoak K (2020) Metaphor processing in autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Rev 57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2020.100925

Mou J, Cui Y, Kurcz K (2019) Bibliometric and visualized analysis of research on major e-commerce journals using CiteSpace. J Electron Commer Res 20(4):219–237

Murphy GL (1997) Reasons to doubt the present evidence for metaphoric representation. Cognition 62:99–108

Norbury CF (2005) The relationship between theory of mind and metaphor: evidence from children with language impairment and autistic spectrum disorder. Br J Dev Psychol 23:383–399. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X26732

Pobric G, Mashal N, Faust M, Lavidor M (2008) The role of the right cerebral hemisphere in processing novel metaphoric expressions: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J Cogn Neurosci 20(1):170–181. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2008.20005

Pouscoulous N (2011) Metaphor: for adults only? Belg J Linguist 25:51–79. https://doi.org/10.1075/bjl.25.04pou

Pouscoulous N (2014) “The elevator’s buttocks” metaphorical abilities in children. In: Matthews D (ed.) Pragmatic development in first language acquisition. Benjamins, Amsterdam

Rai S, Chakraverty S (2020) A survey on computational metaphor processing. ACM Comput Entertain 53:2. https://doi.org/10.1145/3373265 . Article 24, 35 pp

Rapp A, Leube D, Erb M, Grodd W, Kircher T (2004) Neural correlates of metaphor processing. Cogn Brain Res 20(3):395–402

Rossetti I, Brambilla P, Papagno C (2018) Metaphor comprehension in schizophrenic patients. Front Psychol 9:670. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00670

Schmidt G, Seger C (2009) Neural correlates of metaphor processing: the roles of figurativeness, familiarity and difficulty. Brain Cogn 71(3):375–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.06.001

Singh N, Mishra RK (2010) Simulating motion in figurative language comprehension. Open Neuroimaging J 4:46–52. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874440001004010046

Steen GJ, Dorst A, Herrmann JB, Kaal AA, Krennmayr T (2010) Metaphor in usage. Cogn Linguist 21(4):765–796. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.2010.024

Stringarisa A, Medford N, Giampietro V, Brammer M, Davida A (2007) Deriving meaning: distinct neural mechanisms for metaphoric, literal, and non-meaningful sentences. Brain Language 100(2):150–162

Turner M (1996) The literary mind. Oxford University Press, New York

Wilson D, Sperber D (2012) Meaning and relevance. Cambridge University Press, New York

Yeung AWK (2021) Is the influence of Freud declining in psychology and psychiatry? A bibliometric analysis. Front Psychol 12:631516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631516

Zhao X, Zheng Y, Zhao X (2023) Global bibliometric analysis of conceptual metaphor research over the recent two decades. Front Psychol 14:1042121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1042121

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Humanities and Social Science Research Projects of the Chinese Ministry of Education [Grant Number: 19YJA740044].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Foreign Language Research Department, Beijing Foreign Studies University, No. 2, North Street of West Sanhuan Road, Haidian District, 100089, Beijing, P. R. China

Zhibin Peng

School of Foreign Languages, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, No. 2006, Xiyuan Avenue, West Hi-Tech Zone, 611731, Chengdu, Sichuan, P. R. China

Omid Khatin-Zadeh

University of Religions and Denominations, Pasdaran, 37185-178, Qom, Iran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ZP performed the data collection and analyses, and wrote the first version of the manuscript; ZP and OK-Z contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zhibin Peng .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

3,271 bibliometric recordings from the web of science, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Peng, Z., Khatin-Zadeh, O. Research on metaphor processing during the past five decades: a bibliometric analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 928 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02465-5

Download citation

Received : 06 June 2023

Accepted : 27 November 2023

Published : 09 December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02465-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Metaphor research as a research strategy in social sciences and humanities

- Published: 11 March 2023

- Volume 58 , pages 227–248, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Sepehr Ghazinoory ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6761-4694 1 &

- Parvaneh Aghaei ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5185-3589 1

995 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

Metaphors have so far inspired many researchers to explain complex concepts or new theorizing. But there is no clear instruction for metaphor-based research and its validation principles. Here, we first locate metaphor research in social sciences and humanities (SSH) and classify different types of its use. Then we describe the basics of metaphor including its concept, types, components and characteristics. Since the methodology is of special importance in SSH, we introduce the metaphor research strategy in the research onion. Then, inspired by the stages of creative thinking, we present a specific process to carry out this strategy. The stages of proposed process include "expression of rationale and research question", "identification of possible metaphors and selection of preferable one", "evidence collection and cross-domain mapping", and "fitting test". We also propose a fitting test consisting of seven essential principles, which ensure that the final design of the metaphor is appropriate and works properly. The results of this research can formalize and validate the metaphor research as an efficient strategy for theorizing, futurology and describing complex concepts.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Using Metaphors in Sociology: Pitfalls and Potentials

The Role of Metaphors in Model-Building Within the Sciences of Meaning

Do Metaphors Mean or Point? Davidson’s Hypothesis Revisited

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Humanities is the subjective study of humans and their history, culture, and societies with an analytical and critical approach (2021), while social science is the objective study that deals with human behavior in its social and cultural aspects with a scientific and evidence-based approach (Webster 1981 ).

Adams, R.B., Funk, P.: Beyond the glass ceiling: does gender matter? Manage. Sci. 58 , 219–235 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1452

Article Google Scholar

Afshari-Mofrad, M., Ghazinoory, S., Montazer, G.A., Rashidirad, M.: Groping toward the next stages of technology development and human society: a metaphor from an Iranian poet. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 109 , 87–95 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.04.029

Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K., Walter, P.: Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th edition. New York: Garland Science (2002)

Alty, J.L., Knott, R.P., Anderson, B., Smyth, M.: A framework for engineering metaphor at the user interface. Interact. Comput. 13 (2), 301–322 (2000)

Bager-Elsborg, A., Greve, L.: Establishing a method for analysing metaphors in higher education teaching: a case from business management teaching. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 38 , 1329–1342 (2019)

Barnet-Verzat, C., Wolff, F.C.: Gender wage gap and the glass ceiling effect: a firm-level investigation. Int. J. Manpow. 29 , 486–502 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720810904185

Bartee, L., Shriner, W., Creech, C.: Principles of Biology: Biology 211, 212, and 213. Open Oregon Educational Resources (2017)

Baxter, J., Wright, E.O.: The glass ceiling hypothesis: a comparative study of the United States, Sweden, and Australia. Gender Soc. 14 (2), 275–294 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1177/089124300014002004

Beaty, R.E., Silvia, P.J.: Metaphorically speaking: cognitive abilities and the production of figurative language. Mem. Cognit. 41 , 255–267 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-012-0258-5

Benton, T., Craib, I.: Philosophy of social science: The philosophical foundations of social thought. Macmillan Education UK (2010)

Birdsell, B.J.: Creative Metaphor Production in a First and Second Language and the Role of Creativity Doctoral Dissertation. University of Birmingham, Birmingham (2018)

Google Scholar

Botha, E.: Why metaphor matters in education. South African J. Educ. 29 , 431–444 (2009). https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n4a287

Boxenbaum, E., Rouleau, L.: New knowledge products as bricolage: metaphors and scripts in organizational theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 36 , 272–296 (2011). https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0213

Boyd, R.N.: Metaphor and theory change. In: Ortony, A. (ed.) Metaphor and Thought. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1993)

Brown, N.: Identity boxes: using materials and metaphors to elicit experiences. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 22 , 487–501 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2019.1590894

Burke, K.: A grammar of motives. Univ of California Press, California (1969)

Book Google Scholar

Burnyeat, M.: The Theaetetus of Plato. Hackett Publishing, Indianapolis (1990)

Cao, M., Zhang, Q.: Supply chain collaboration: impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. J. Op. Manag. 29 , 163–180 (2011)

Cassell, C., Lee, B.: Driving, steering, leading, and defending: journey and warfare metaphors of change agency in trade union learning initiatives. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 48 , 248–271 (2012)

Chang, L.P.L., Jonathan, L.Y.: The role of scientific terminology and metaphors in management education. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 6 , 33–43 (2019)

Chiesa, V., Manzini, R.: Organizing for technological collaborations: a managerial perspective. R&D Manag. 28 , 199–212 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9310.00096

Chowdhury, R.: An appreciation of metaphors in management consulting from the conceptual lens of holistic flexibility. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 38 , 137–157 (2021)

Chun, L.: Cognitive Linguistics and Metaphoric Study. Foreign Language Teaching and Research press, Beijing (2005)

Cornelissen, J.P.: Beyond compare: metaphor in organization theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 30 , 751–764 (2005)

Cornelissen, J.P.: Making sense of theory construction: metaphor and disciplined imagination. Organ. Stud. 27 , 1579–1597 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840606068333

Cornelissen, J.P., Kafouros, M.: Metaphors and theory building in organization theory: what determines the impact of a metaphor on theory? *. Br. J. Manag. 19 , 365–379 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00550.x

Cornelissen, J.P., Oswick, C., Thøger Christensen, L., Phillips, N.: Metaphor in organizational research: context, modalities and implications for research—Introduction. Org. Stud. 29 , 7–22 (2008)

Crisp, P.: Allegory: conceptual metaphor in history. Lang. Lit. Int. J. Stylist. 10 , 5–19 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1177/0963-9470-20011001-01

Cruz, E.F., Cruz, A.M.R. Da: Design Science Research for IS/IT Projects: Focus on Digital Transformation. In: 2020 15th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), IEEE, pp. 1–6. (2020)

Danaeifard, H., Javan Ali Azar, M.: Methodology of metaphorizing in organizational and management studies: a descriptive approach. Working paper (2021)

Dancygier, B., Sweetser, E.: Figurative Language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2014)

Dastranj, R., Ghazinoory, S., Dastranj, N., Shayan, A.: Assessment of big data ecosystem in Iran with metaphor of millennium ecosystem assessment model. Iran. J. Inf. Process. Manag. 34 , 1613–1642 (2019)

Demjén, Z., Semino, E.: Using metaphor in healthcare: Physical health. In: The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language. pp. 403–417. Routledge (2016)

Doctorow, E.L.: “False Documents.” American Review 26, (1977)

Dörfler, V., Baracskai, Z., Velencei, J.: Understanding creativity. Trans. Adv. Res. 6 (2), 18–26 (2010)

Fadaee, E.: Symbols, metaphors and similes in literature: a case study of “Animal Farm.” J. English Lit. 2 , 19–27 (2011)

Ghazinoory, S., Phillips, F., Afshari-Mofrad, M., Bigdelou, N.: Innovation lives in ecotones, not ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 135 , 572–580 (2021)

Ghazinoory, S., Nasri, S., Dastranj, R., Sarkissian, A.: “Bio to bits”: the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) as a metaphor for Big Data ecosystem assessment. Inf. Technol. People 35 (2), 835–858 (2022)

Harvey, M.: Human resource management in Africa: Alice’s adventures in wonderland. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 13 , 1119–1145 (2002)

Hazy, J.K.: More than a Metaphor: Complexity and the New Rules of Management. In: Allen, P., Maguire, S., and McKelvey, B. (eds.) Sage Handbook of Complexity and Leadership. Sage Publications (2011)

Hekkala, R., Stein, M., Rossi, M.: Metaphors in managerial and employee sensemaking in an information systems project. Inf. Syst. J. 28 , 142–174 (2018)

Hidalgo-Downing, L., Kraljevic-Mujic, B.: Metaphor and Persuasion in Commercial Advertising. Routledge Handbook Publications, Routledge (2017)

Humanities: https://www.britannica.com/topic/humanities (2021)

Hunt, S.D., Menon, A.: Metaphors and competitive advantage: evaluating the use of metaphors in theories of competitive strategy. J. Bus. Res. 33 , 81–90 (1995)

Johnson-Sheehan, R.D.: The emergence of a root metaphor in modern physics: max Planck’s ‘quantum’metaphor. J. Tech. Writ. Commun. 27 , 177–190 (1997)

Judge, A.J.N.: Metaphor and the language of futures. Futures 25 , 275–288 (1993)

Koch, S., Deetz, S.: Metaphor analysis of social reality in organizations. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 9 , 1–15 (1981)

Konttinen, J.: Managing the Creative Process in Game Development. Bachelor’s thesis, School of Business and Management, LUT University, Finland (2018)

Kövecses, Z.: Conceptual metaphor theory. In: Semino, Elena, and Zsófia Demjén, (eds.) The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language. pp. 31–45. Routledge (2016)

Kuhn, T.S.: Metaphor in science. Metaphor Thought 2 , 533–542 (1979)

Lakoff, G.: The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor Metaphor and Thought. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1993)

Lakoff, G., Johnson, M.: Conceptual metaphor in everyday language. J. Philos. 77 , 453 (1980). https://doi.org/10.2307/2025464

Lakoff, G., Johnson, M.: Metaphors We Live By. The university of Chicago press, London (2008)

Lubart, T.I.: Models of the creative process: past, present and future. Creat Res. J. 13 , 295–308 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1334_07

Lubart, T.I., Getz, I.: Emotion, Metaphor, and the creative process. Creat Res. J. 10 , 285–301 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1004_1

MacCormac, E.R.: Metaphor and Myth in Science and Religion. Duke Univ Press, Durham (1976)

Mahootian, F.: Metaphor in chemistry: an examination of chemical metaphor. Philos. Chem. Growth New Discip. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9364-3_9

Martin, R.M.: Of time and the null individual. J. Philos. 62 , 723–736 (1965)

McCulloch, W.S., Pitts, W.: A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 5 , 115–133 (1943)

McMullen, J.S.: Organizational hybrids as biological hybrids: Insights for research on the relationship between social enterprise and the entrepreneurial ecosystem. J. Bus. Ventur. 33 (5), 575–590 (2018)

Moore, J.F.: The death of competition: Leadership and strategy in the age of business ecosystem. Harper Paperbacks (1996)

Morgan, G.: Paradigms, metaphors, and puzzle solving in organization theory. Adm. Sci. Q. (1980). https://doi.org/10.2307/2392283

Morgan, G.: Images of Organization. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, California (1998)

Morgan, G.: Images of organization. Berrett-Koehler Publishers (1986)

Nasrollahi, M., Ramezani, J.: A model to evaluate the organizational readiness for big data adoption. International Journal of Computers, Communications and Control. 15, (2020)

Oakley, T.: Conceptual integration. In: Handbook of Pragmatics. pp. 1–24. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam (2011)

Oswick, C., Keenoy, T., Grant, D.: Note: metaphor and analogical reasoning in organization theory: Beyond orthodoxy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 27 , 294–303 (2002)

Paley, W.: Natural theology. Evolution and creationism 22–26 (2007)

Pulaczewska, H.: Aspects of Metaphor in Physics: Examples and Case Studies. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin (2011)

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., Thornhill, A.: Reserach methods for business students. Essex: Prentice Hall: Financial Times (2009)

Sawyer, R.K.: The Stages of the Creative Process. In: Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press (2006)

Shaw, M.P.: The Eureka Process: a structure for the creative experience in science and engineering. Creat Res. J. 2 , 286–298 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1080/10400418909534325

Simpson, J., Weiner, E.: Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press (1989)

Steinhart, E.: The Logic of Metaphor: Analogous Parts of Possible Worlds. Springer, Berlin (2001)

Tesch, B.J., Wood, H.M., Helwig, A.L., Nattinger, A.B.: Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine: glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA 273 , 1022–1025 (1995)

Van Mulken, M., Le Pair, R., Forceville, C.: The impact of perceived complexity, deviation and comprehension on the appreciation of visual metaphor in advertising across three European countries. J. Pragmat. 42 , 3418–3430 (2010)

Van Mulken, M., Van Hooft, A., Nederstigt, U.: Finding the tipping point: visual metaphor and conceptual complexity in advertising. J. Advert. 43 , 333–343 (2014)

Veblen, T.: Why is economics not an evolutionary science? Q. J. Econ. 12 , 373 (1898). https://doi.org/10.2307/1882952

Vu, N.N.: Structural, orientational, ontological conceptual metaphors and implications for language teaching. Ho Chi Minh City Open Univ. J. Sci. Soc. Sci. 5 (1), 49–53 (2015)

Wallas, G.: The Art of Thought. Harcourt, Brace (1926)

Webster, N.: Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. Merriam-Webster, Springfield (1981)

Wexler, M.: Uncertainty as a root metaphor in social science. Free Inq. Creat. Sociol. 9 , 31–38 (1981)

Williams, L.: V: Teaching for the Two-Sided Mind. Simon and Schuster, New York (1986)

Winter, G.: Liberating creation: Foundations of religious social ethics. Crossroad (1981)

Zhang, X.: Development and critiques of conceptual metaphor theory. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 11 , 1487–1491 (2021). https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1111.18

Zhang, F., Hu, J.: A study of metaphor and its application in language learning and teaching. Int. Educ. Stud. 2 , 77–81 (2009)

Download references

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Information Technology Management, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

Sepehr Ghazinoory & Parvaneh Aghaei

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Parvaneh Aghaei .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ghazinoory, S., Aghaei, P. Metaphor research as a research strategy in social sciences and humanities. Qual Quant 58 , 227–248 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-023-01641-8

Download citation

Accepted : 22 February 2023

Published : 11 March 2023

Issue Date : February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-023-01641-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Conceptual metaphor

- Metaphor research

- Research strategy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics