Religious Perspectives on the Death Penalty

Pro Death Penalty

Southern Baptist Association

Con Death Penalty

Catholic Church

Conservative Judaism

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

Episcopal Church

Orthodox Judaism

Presbyterian Church USA

Reconstructionist Judaism

Reform Judaism

Unitarian Universalist Association

United Church of Christ

United Methodist Church

Not Clearly Pro or Con

Assemblies of God

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

“God’s attitude toward the killing of innocents is clear. No one is guiltless who takes the life of another, with the possible scriptural exceptions of capital punishment administered by a system of justice (Genesis 9:6; Numbers 35:12), unintended killing in self-defense (Exodus 22:2), or deaths occasioned by duly constituted police and war powers (Romans 13:4,5)…

The Bible does provide precedents for justly administered death sentences for capital crimes as well as for the exercise of self defense and duly constituted police and war powers (Genesis 9:6; Exodus 22:2; Numbers 35:12; Romans 13:4,5). “

Source: Assemblies of God, “Sanctity of Human Life: Abortion and Reproductive Issues,” ag.org, Aug. 9-11, 2010

“There is no common position among Buddhists on capital punishment, but many emphasize nonviolence and appreciation for life. As a result, in countries with large Buddhist populations, such as Thailand, capital punishment is rare.”

Source: Pew Research Center, “Religious Groups’ Official Positions on Capital Punishment,” pewforum.org, Nov. 4, 2009

“There are two extreme situations that may come to be seen as solutions in especially dramatic circumstances, without realizing that they are false answers that do not resolve the problems they are meant to solve and ultimately do no more than introduce new elements of destruction in the fabric of national and global society. These are war and the death penalty…

Saint John Paul II stated clearly and firmly that the death penalty is inadequate from a moral standpoint and no longer necessary from that of penal justice. There can be no stepping back from this position. Today we state clearly that ‘the death penalty is inadmissible’ and the Church is firmly committed to calling for its abolition worldwide.”

Source: Pope Francis, “Encyclical Letter Fratelli Tutti of the Holy Father Francis on Fraternity and Social Friendship,” vatican.va, Oct. 3, 2020

“The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints regards the question of whether and in what circumstances the state should impose capital punishment as a matter to be decided solely by the prescribed processes of civil law. We neither promote nor oppose capital punishment.”

Source: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, “Capital Punishment,” newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org (accessed Aug. 26, 2021)

“In 1960, the Conservative Movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards approved a paper by Rabbi Ben Zion Bokser that advocated abolition of the death penalty.”

Source: Lewis Warshauer, “The Death Penalty and Conservative Judaism,” myjewishlearning.com (accessed Aug. 26, 2021)

“The Death Penalty stands in the Lutheran tradition recognizing that God entrusts the state with the power to take human life when failure to do so constitutes a clear danger to the common good. Never-the-less, it expresses ELCA opposition to the use of the death penalty, one that grows out of ministry with and to people affected by violent crime.

The statement acknowledges the existence of different points of view within the church and society on this question and the need for continued deliberation, but it objects to the use of the death penalty because it is not used fairly and has failed to make society safer. The practice of using the death penalty in contemporary society undermines any possible alternate moral message since the primary message conveyed by an execution is one of brutality and violence. This social statement was adopted by the 1991 ELCA Churchwide Assembly.”

Source: Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, “Death Penalty,” elca.org (accessed Aug. 26, 2021)

“Resolved, That the 79th General Convention of The Episcopal Church reaffirms the longstanding principle espoused by The Episcopal Church that the Death Penalty in the United States of America should be repealed; and be it further Resolved, That all persons who have been sentenced to Death in the United States of America have their Death Sentences reduced to a lesser Sentence or, if innocent, granted exoneration…

Source: Episcopal Church, “Reaffirm Opposition to the Death Penalty,” edtn.org, 2018

“There is no official position on capital punishment among Hindus, and Hindu theologians fall on both sides of the issue.”

“In the United States, where Islamic law – Shariah – is not legally enforced, there is no official Muslim position on the issue of the death penalty. In Islamic countries, however, capital punishment is sanctioned in only two instances: cases involving intentional murder or physical harm of another; and intentional harm or threat against the state, including the spread of terror.”

“The Orthodox Union supports efforts to place a moratorium on executions in the United States and the creation of a commission to review the death penalty procedures within the American judicial system.”

Source: Orthodox Union, “The Orthodox Union’s 108th Anniversary Convention Resolutions,” advocacy.ou.org, Nov. 22-26, 2006

“Despite the government’s constantly changing position on the death penalty, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) has been strong and consistent in its call for a moratorium on capital punishment. We believe that the death penalty challenges the redemptive power of the cross. God’s grace is sufficient for all humans regardless of their sin. As Christians, we must ‘seek the redemption of evildoers and not their death.’

For the past 60 years, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) has been advocating for an end to the death penalty.”

Source: Presbyterian Church USA Presbyterian Office of Public Witness, “Statement on the Federal Death Penalty,” presbyterianmission.org, Aug. 5, 2019

“Whereas the Jewish scriptural tradition teaches that all human beings are created B’tzelem Elohim (in the image of God) and upholds the sanctity of all life;

Whereas both in concept and in practice, Jewish leaders throughout over the past 2000 plus years have refused, with rare exception, to punish criminals by depriving them of their lives;

And whereas current evidence and technological advances have shown that as many as three hundred people (disproportionately from minority and poor populations) have been wrongly convicted of capital crimes in America in the last century, which underscores the Jewish concern over capital punishment since all human systems of justice are inherently fallible and imperfect –

Therefore, we resolve that the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association go on record opposing the death penalty under all circumstances, opposing the adoption of death penalty laws, and urging their abolition in states that already have adopted them.”

Source: Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association, “Resolution: Death Penalty 2003,” therra.org, 2003

“The Bible prescribes the death penalty for at least 36 transgressions, from intentional murder to cursing one’s parents, but the practice essentially ended when the rabbinic sages of the Talmud imposed preconditions and evidence requirements so rigorous as to make capital punishment a rarity. Jewish tradition essentially follows the position of Rabbis Tarfon and Akiba: never to impose capital punishment (Mishna Makkot 1:10).

The Reform Movement has formally opposed the death penalty since 1959, when the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (now the Union for Reform Judaism) resolved ‘that in the light of modern scientific knowledge and concepts of humanity, the resort to or continuation of capital punishment either by a state or by the national government is no longer morally justifiable.’ The resolution goes on to say that the death penalty ‘lies as a stain upon civilization and our religious conscience.’

In 1979, the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), the professional arm of the Reform rabbinate, resolved that ‘both in concept and in practice, Jewish tradition found capital punishment repugnant’ and there is no persuasive evidence ‘that capital punishment serves as a deterrent to crime.'”

Source: Aron Hirt-Manheimer, “Why Reform Judaism Opposes the Death Penalty,” reformjudaism.org (accessed Aug. 26, 2021)

Southern Baptist Convention

“WHEREAS, The Bible teaches that every human life has sacred value (Genesis 1:27) and forbids the taking of innocent human life (Exodus 20:13); and

WHEREAS, God has vested in the civil magistrate the responsibility of protecting the innocent and punishing the guilty (Romans 13:1-3); and

WHEREAS, We recognize that fallen human nature has made impossible a perfect judicial system; and

WHEREAS, God authorized capital punishment for murder after the Noahic Flood, validating its legitimacy in human society (Genesis 9:6); and

WHEREAS, God forbids personal revenge (Romans 12:19) and has established capital punishment as a just and appropriate means by which the civil magistrate may punish those guilty of capital crimes (Romans 13:4); and

WHEREAS, God requires proof of guilt before any punishment is administered (Deuteronomy 19:15-19); and

WHEREAS, God’s instructions require a civil magistrate to judge all people equally under the law, regardless of class or status (Leviticus 19:15; Deuteronomy 1:17); and

WHEREAS, All people, including those guilty of capital crimes, are created in the image of God and should be treated with dignity (Genesis 1:27).

Therefore, be it RESOLVED, That the messengers to the Southern Baptist Convention, meeting in Orlando, Florida, June 13-14, 2000, support the fair and equitable use of capital punishment by civil magistrates as a legitimate form of punishment for those guilty of murder or treasonous acts that result in death”

Source: Southern Baptist Convention, “On Capital Punishment,” sbc.net, June 1, 2000

“WHEREAS, at this time, even though there has been no execution in the United States for the past seven years, twenty-eight states have already passed legislation seeking to re-establish capital punishment; and

WHEREAS, the act of execution of the death penalty by government sets an example of violence;

BE IT RESOLVED: That the 1974 General Assembly of the Unitarian Universalist Association continues to oppose the death penalty in the United States and Canada, and urges all Unitarian Universalists and their local churches and fellowships to oppose any attempts to restore or continue it in any form.”

Source: Unitarian Universalist Association, “Death Penalty 1974 General Resolution,” uua.org, June 1, 1974

“The United Church of Christ historically has opposed capital punishment. We first formalized this position in 1969 and we have reaffirmed it many times in the years since. In 2005 our General Synod passed a resolution calling for the common good as a foundational idea in the United States. We simply believe that murder is wrong, whether committed by individuals or the state. Currently our churches are working for abolition of the death penalty.”

Source: United Church of Christ, “Capital Punishment,” ucc.org (accessed Aug. 26, 2021)

“The United Methodist Church says, ‘The death penalty denies the power of Christ to redeem, restore, and transform all human beings.’ (Social Principles ¶164.G) As Wesleyans, we believe that God’s grace is ever reaching out to restore our relationship with God and with each other. The death penalty denies the possibility of new life and reconciliation.

The United Methodist Church also recognizes the unjust and flawed implementation of the death penalty, pointing out the example of Texas, where executions reveal racism, bias against mentally handicapped persons and the likely execution of at least one innocent person. (Book of Resolutions, 5037)

‘We oppose the death penalty (capital punishment) and urge its elimination from all criminal codes.’ (Social Principles ¶164.G)”

Source: United Methodist Church, “Death Penalty,” umcjustice.org (accessed Aug. 26, 2021)

Icon credits:

cancel by Braja Omar Justico from the Noun Project

help by Braja Omar Justico from the Noun Project

success by Braja Omar Justico from the Noun Project

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- History of the Death Penalty

- Top Pro & Con Quotes

- Historical Timeline

- Did You Know?

- States with the Death Penalty, Death Penalty Bans, and Death Penalty Moratoriums

- The ESPY List: US Executions 1608-2002

- Federal Capital Offenses

- Death Row Inmates

- Critical Thinking Video Series: Thomas Edison Electrocutes Topsy the Elephant, Jan. 4, 1903

Cite This Page

- Artificial Intelligence

- Private Prisons

- Space Colonization

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Toll of QAnon on families of followers

The urgent message coming from boys

Your kid can’t name three branches of government? He’s not alone.

Francis X. Clooney: “If we quote a verse out of Genesis or another verse out of the Letter to the Romans without due attention to context, we run the risk of ‘proof texting’: finding a verse in the Bible that justifies what you feel you should do today.”

File photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The death penalty and Christianity

Paul Massari

Harvard Divinity School Communications

A Q&A with Francis X. Clooney examines how both sides in an endless debate seek biblical backing

The botched execution of Oklahoma death row inmate Clayton Lockett in April ignited a national discussion about capital punishment that was followed by fresh debate over the executions of three felons last week in Missouri, Georgia, and Florida.

Christians on both sides of the issue have been weighing in on capital punishment, saying that Scripture supports their position.

R. Albert Mohler Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, has argued that “ the Bible clearly calls for capital punishment in the case of intentional murder .” But Christian activist and author Shane Claiborne has countered that the teachings of Jesus provide no support for the death penalty .

To add context and nuance to the conversation, Paul Massari of Harvard Divinity School Communications turned to Francis X. Clooney, Parkman Professor of Divinity and professor of comparative theology and director of the Center for the Study of World Religions at the School.

Clooney questions the reasoning of those who say Christians should support the death penalty, but also suggests that opponents who quote Jesus may not be comfortable with the logical extension of the teachings they cite. Absolute opposition to the death penalty may seem out of touch with a realistic view of the world; tolerance of it may seem far removed from the teachings of Jesus.

HARVARD DIVINITY SCHOOL (HDS): How do you understand the assertion, articulated by Christians like Dr. Mohler, that “God affirmed the death penalty for murder as he made his affirmation of human dignity clear” in the Bible?

CLOONEY: It strikes me as not unexpected, since Christians have often enough argued for such punishments, reconciling them with a view of God’s plan as set out in the Bible. But what Jesus would say is often treated differently. A few years ago, I went to Mass one Sunday at a local parish. The Gospel was the part of the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus says, “Turn the other cheek. Do not resist evil.” The homilist said, “The teaching of Jesus is radical nonviolence. But that’s not the teaching of the church, so let me now tell you about the teaching of the church.” He went on for another 20 minutes about just-war theory and the legitimate use of force by the state, and so on. The views of Jesus were not mentioned again.

This is a typical situation. On the one hand there’s Jesus, and we’ll never criticize Jesus. On the other hand there’s the way we do things — and the way most Christians have done things for a long time. It is not surprising that in Christian arguments for the death penalty, Jesus doesn’t really come up at all. Many of us find him too radical for everyday life.

HDS: But are they saying, “This is the way we do things,” or, “The Bible calls for capital punishment in the name of human dignity”?

CLOONEY: Many Christians — Southern Baptists, Protestants, and Catholics, too — will say both. They look at the Bible and say, “Clearly the death penalty can be found in the Bible,” and find guidance there for what the states should do in 2014. Most are not reckless in their calls for capital punishment. Leaders such as Dr. Mohler recognize the continuing need to respect human nature, the possibility of the abuse of government power, the dangers of state-sponsored violence, and the miscarriages of justice that not infrequently have taken place. They’re not saying, “Kill people without hesitation, or because they merely deserve to be killed.”

They’re also saying that the death penalty doesn’t permit individuals or lynch mobs to take the law into their own hands and go out and kill those they think should be killed. They recognize human dignity, but also legitimacy of the death penalty, and they try to make the case that these go together. In this way of thinking, such power is given over to the state, in accord with the theory of the legitimate role of state power, which goes back to the Middle Ages and before.

HDS: So, in this view, capital punishment and respect for human dignity are separate commandments from God, but not necessarily tied to one another?

CLOONEY: They’re interrelated in the sense that they both come from the plan of God. For Dr. Mohler, these commands are not contradictory either. Rather, respect human nature, and, in some rare cases, take the life of fellow human beings, particularly those who kill other humans. It is as if to say, “Because we respect life, we take life.” By this view, neither value replaces the other. They’re not saying, “We kill people because they don’t deserve human respect,” but they also refuse to say, “Respect for human beings means that you can never kill anyone.” Rather, the thinking goes, respect for human life and capital punishment are distinct issues, and a Christian can hold both.

HDS: What about the Biblical passages cited by Christians who support capital punishment? Is there a larger context to these that adds some complexity?

CLOONEY: Passages can be found that sanction putting someone to death, and many a text reports the killing of individuals and groups. But the path from one or another Bible verse to state policy today is very complicated. If we quote a verse out of Genesis or another verse out of the Letter to the Romans without due attention to context, we run the risk of “proof texting”: finding a verse in the Bible that justifies what you feel you should do today. Centuries of modern Biblical scholarship have shown us that these texts don’t float free of their contexts. You have to read them according to the intentions of the author, the options of the time, and so on. Rarely can they be applied without modification to the world in which we live.

Take the Genesis text, where after the great flood God is bringing the world back to life. In that context, God stresses the sacredness of human life, and therefore predicts and warns: “Whoever sheds the blood of a human, by a human shall that person’s blood be shed;for in his own image God made humankind” [Genesis 9:6]. This saying could be taken a number of ways. It could sanction the death penalty, or it could simply remind us that violence leads to more violence. If you kill, your blood will be taken in turn.

Human life is always sacred. By elaborate reasoning, I suppose, it could be taken to justify killing those who kill, and thus to support the death penalty in 21st-century America. But it could more easily be argued as having very little to do with the death penalty in today’s America.

All of this is difficult. It is a problem to take any verse out of context. It is also a problem to think that in 2014 we can apply verses from the Bible directly to the policies of Texas or Oklahoma or the federal government, and thus justify the death penalty. Yet, to be honest, it would also be a problem to end up in a position where no Biblical verse ever provides guidance in 2014. So some balance of verse and context is needed. On the whole, I am not at all convinced that any biblical verses support the modern world’s use of the death penalty.

HDS: Is it ever possible for capital punishment to be applied in a way that makes moral sense?

CLOONEY: Since we live in a world tainted by sin, and since things that aren’t desirable or ideal are still part of what it takes to live in this imperfect world, then hard and realistic compromises are often necessary. Most of us most of the time do not live out the example of Jesus without compromise. Some believe that in a hard and violent world, the death penalty is a necessary evil. On a larger social scale, some Christians defend going to war and killing people either in direct combat or by bombing armies or cities. If we lived in an ideal world, there wouldn’t be any wars, or a death penalty. But the world is not ideal, and so we kill. Such is the logic.

HDS: So is the Christian view to say, “No more war. No more fighting. Conscientious objection. Never the death penalty,” and so on? Or is it to say, “In the world in which we live, let’s talk about the death penalty. What are the rationale and the evidence that the death penalty serves a useful social function?”

CLOONEY: This is exactly what each of us needs to decide. Even if we wish to follow the radical example of Jesus, we still need to use the intelligence God has given us.

Even aside from how we use the Bible in this debate, the death penalty is subject to doubt, and it’s quite possible to give a hard time to its proponents. Is there evidence that it does any good? Isn’t it rather often a matter of revenge? It is supposed to be a matter of warning people: “Don’t do that because you’ll get killed if you do”? But do such warnings work as a deterrent? And what are the collateral effects of trivializing human life by killing people for any reason? Where’s the evidence that the death penalty is applied fairly and that there’s no systemic bias involved?

In the end, I think a lot of people — maybe even a majority of people who think seriously about these issues — would say that the evidence is just not there that the death penalty achieves a good commensurate with the evil of giving the state permission to take life. Accordingly, arguments about all these points are quite common today, of course, and that is for the better. Quoting the Bible or any sacred text does not excuse us from debating the evidence for and against the death penalty.

HDS: So where do you draw the line in the discussion between morality and the real world? For instance, supporters might say that the death penalty would be a deterrent if cases weren’t tied up in court and we executed sentences more efficiently. If that were true, would capital punishment be OK?

CLOONEY: Good point. Certainly one can say, “Neither this nor that is absolute, so we just have to make a prudential judgment based on effectiveness.” Does the state have a right to control handguns, or enforce traffic laws, or to arrest someone who’s robbing a bank, abusing a child, running a corrupt Wall Street firm, or polluting the environment on a massive scale? Of course it does. And of course we have to try to be fair in the application of the law, improving an imperfect system.

In an ideal justice system, the death penalty might conceivably be carried out fairly and without bias. But since our justice system is not ideal, that hope is not very plausible. And so, in today’s society, we still have to debate whether the death penalty serves any good purpose, just as we can debate whether life imprisonment without the possibility of parole serves any legitimate purpose that does anyone any good.

HDS: Death penalty supporters say that the Bible doesn’t say that human life is an absolute value. People get killed in the Bible all the time. Other values have to come in.

CLOONEY: Yes, but we need to be very cautious in then making a list of values that are superior to human life. Moreover, values are interconnected, woven together. In the Catholic Church, for instance, there’s the ideal of the “seamless garment of life.” From conception to a natural death not hastened by poverty or injustice, life is an absolute value that must always be respected. You can’t sacrifice a human life for the sake of another good you have decided to be of greater value. You can’t say that human life is worth respecting only some of the time. If you do, where do you draw the line? Best to say, from conception to old age, all human life is to be respected, protected, and enabled to flourish. Neither abortion nor the death penalty is tolerable; neither is the ruining of lives by systemic poverty and the violence that makes so many suffer their whole lives long. In fact we tolerate many things that demean human flourishing, particularly when others, far away, are affected rather than ourselves. But in our better moments we can hardly condone such callousness.

HDS: Most Biblical citations of Christians who support the death penalty draw from the Old Testament. So where does Jesus come in?

CLOONEY: The worldly view, even among Christians, is that you can’t run society based on the principles of Jesus. If everybody turned the other cheek, then all the “bad” people would win. If everyone gave up his or her wealth, society would collapse. So you need to seek out other references in the Bible.

Opponents to the death penalty are surely right in holding that Jesus wouldn’t allow it. The incidents we see in the Gospels — the woman caught in adultery, for instance — reject killing, and reject the self-righteousness and anger that lead us to kill. Jesus clearly says, “Turn the other cheek.”

If Christian death penalty supporters want to adhere to the Bible, they need to face up to the exemplar of Jesus, too, and not leave him out of the picture when defending the death penalty. Every word of the Bible then needs to be reread in light of the teachings of Jesus.

To be fair, those of us defending the radical nonviolence of Jesus similarly need to read the whole of the Bible as well, not merely ignoring the parts we’d rather not think about.

HDS: Is it a matter of Christianity with Jesus or without Jesus? Every church wants to have Jesus at the center, but also wants to put in other principles, as well as accommodating moral and political issues. But is the example in the Gospels the only one for being a good Christian?

CLOONEY: No Christian will want to promote Christianity without Jesus at its center. A Christianity grounded in the Gospels and thus in the life and death of Jesus will end up being radical Christianity. It will hold to standards that resist merely coming to terms with any given political situation, catering to the whims of the state and the majority, and so on. But accommodation to political realities will still take place. Think of St. Paul’s “real world” accommodation of cultural conditions, the fact of empire, etc.

HDS: You mention St. Paul. Why do death penalty supporters often cite his writings?

CLOONEY: Paul lived in the Roman Empire and had to make space for the Christian community amidst Roman power. He had to show that Christians were not the enemy of the state, and that Christianity was not opposed to all civil power. And so Paul had to talk about respecting authority, paying taxes, the power that kings have, etc. In his Letter to the Romans, he writes: “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God” [Romans 13:1].

The radical alternative would have been to be a fringe group that the Romans would have sought to destroy — and that might well have died out, like many others. The history of how the church came to be amidst the empire is a well-known topic, and many scholars have written on how Christianity learned to live with — and benefit from — imperial power. That’s our history, right down to the death penalty, and there is much to be ashamed of.

And yet, to be fair, even Jesus seems to admit some accommodation. There’s the scene where he’s asked whether or not the Jews should pay the Roman tax, and he says, “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s” [Matthew 22:21]. He doesn’t say that it’s all God’s, as if Caesar has no power or realm of authority.

But still, there is no direct path from giving to Caesar what is Caesar’s to the death penalty in one or another American state today. Much exegesis and many prudential arguments must occur in between, before we might get anywhere near justifying the death penalty simply because Jesus spoke those words in Matthew 22.

HDS: So, are Christians like Dr. Mohler arguing for a position that is actually “worldly,” but portraying it as wisdom received from God?

CLOONEY: Again, this requires a difficult balance. On the one hand, he’s employing a certain kind of Biblical literalism, where we take the words at face value as assertive of truths that can be directly applied in 2014. God says it’s OK to kill people under certain circumstances, so the states have the authority to execute prisoners now.

Others among us remain very skeptical, and do not believe we honor God’s word by such direct and seemingly simplistic applications.

On the other hand, Dr. Mohler seems to be assuming that the death penalty is justified because it’s good for American society today. But the evidence for that opinion is open to dispute, as I mentioned above. Quoting some passages from the Bible does not end the debate. But in the end, perhaps the burden is still greater for those who oppose the death penalty because it is not in keeping with the teachings and life of Jesus. If we really believe that, then we need to act like Jesus all the time, not just when it is the death penalty that is up for debate.

Share this article

You might like.

New book by Nieman Fellow explores pain, frustration in efforts to help loved ones break free of hold of conspiracy theorists

When we don’t listen, we all suffer, says psychologist whose new book is ‘Rebels with a Cause’

Efforts launched to turn around plummeting student scores in U.S. history, civics, amid declining citizen engagement across nation

You want to be boss. You probably won’t be good at it.

Study pinpoints two measures that predict effective managers

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

God and the Executioner: The Influence of Western Religion on the Use of the Death Penalty By Davison M. Douglas / William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal, on 1 January 2000

In this essay, Professor Douglas conducts an historical review of religious attitudes toward capital punishment and the influence of those attitudes on the state’s use of the death penalty. He surveys the Christian Church’s strong support for capital punishment throughout most of its history, along with recent expressions of opposition from many Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish groups. Despite this recent abolitionist sentiment from an array of religious institutions, Professor Douglas notes a divergence of opinion between the “pulpit and the pew” as the laity continues to support the death penalty in large numbers. Professor Douglas accounts for this divergence by noting the declining influence of religious organizations over the social policy choices of their members. He concludes that the fate of the death penalty in America will therefore “most likely be resolved in the realm of the secular rather than the sacred.

United States

Retentionist Death penalty legal status

22nd World Day Against the Death Penalty – The death penalty protects no one.

Observed every 10 October, the World Day Against the Death Penalty unifies the global abolitionist movement and mobilizes civil society, political leaders, lawyers, public opinion and more to support the call for the universal abolition of capital punishment.

Helping the World Achieve a Moratorium on Executions

In 2007, the World Coalition made one of the most important decisions in its young history: to support the Resolution of the United Nations General Assembly for a moratorium on the use of the death penalty as a step towards universal abolition. A moratorium is temporary suspension of executions and, more rarely, of death sentences. […]

Can you be Christian and support the death penalty?

Professor of Religious Studies, College of the Holy Cross

Disclosure statement

Mathew Schmalz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

College of the Holy Cross provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Pope Francis has declared the death penalty “ inadmissible .” This means that the death penalty should not be used in any circumstance. It also alters the Catholic Catechism , a compendium of Catholic doctrine, and is now binding on Roman Catholics throughout the world.

But in spite of his definitive statement, Pope Francis’ act will probably only deepen the debate about whether Christians can support capital punishment.

As a Catholic scholar who writes about religion, politics and policy, I understand how Christians struggle with the death penalty – some cannot endure the idea and others support it as a way to deter and punish terrible crimes. Some Christian theologians have also observed that capital punishment could actually lead to a change of heart among criminals who might repent when faced with the finality of death.

Is the death penalty un-Christian?

The two sides

In its early centuries, Christianity was seen with suspicion by authorities. Writing in defense of Christians who were unfairly charged with crimes in second-century Rome, philosopher Anthenagoras of Athens condemned the death penalty and wrote that Christians “cannot endure even to see a man put to death, though justly.”

But as Christianity became more connected with state power, European Christian monarchs and governments regularly carried out the death penalty until its abolition in the 1950s through the European Convention on Human Rights. In the Western world, today, only the United States and Belarus retain capital punishment for crimes not committed during wartime. But China, and many nations in the Middle East, South Asia and Africa still apply the death penalty.

According to a 2015 Pew Research Center Survey , support for the death penalty is falling worldwide . However, in the United States a majority of white Protestants and Catholics continue to be in favor of it.

Critics of the American justice system argue that the deterrence value of capital punishment is debatable. There are also studies showing that, in the United States, capital punishment is unfairly applied , especially to African-Americans.

Christian views

In the Hebrew Bible, Exodus 21:12 states that “whoever strikes a man so that he dies shall be put to death.” In Matthew’s Gospel , Jesus, however, rejects the notion of retribution when he says “if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.”

While it is true that the Hebrew Bible prescribes capital punishment for a variety of offenses, it is also true that later Jewish jurists set out rigorous standards for the death penalty so that it could be used only in rare circumstances.

At issue in Christian considerations of the death penalty is whether the state has the obligation to punish criminals and defend its citizens.

St. Paul, an early Christian evangelist, wrote in his letter to the Romans that a ruler acts as “an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer.” The Middle Ages in Europe saw thousands of murderers, witches and heretics put to death. While church courts of this period generally did not carry out capital punishment , they did turn criminals over to secular authorities for execution.

Thirteenth-century Catholic philosopher Thomas Aquinas argued that the death penalty could be justified for the greater welfare of society. Later Protestant reformers also supported the right of the state to impose capital punishment. John Calvin , a Protestant theologian and reformer, argued that Christian forgiveness did not mean overturning established laws.

The position of Pope Francis

Among Christian leaders, Pope Francis has been at the forefront of arguing against the death penalty.

The letter accompanying the Pope’s declaration makes several points. First, it acknowledges that the Catholic Church has previously taught that the death penalty is appropriate in certain instances. Second, the letter argues that modern methods of imprisonment effectively protect society from criminals. Third, the letter states that this development of Catholic doctrine is consistent with the thought of the two previous popes: St. Pope John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

St. John Paul II maintained that capital punishment should be reserved only for “absolute necessity.” Benedict XVI also supported efforts to eliminate the death penalty.

Most important, however, is that Pope Francis is emphasizing an ethic of forgiveness. The Pope has argued that social justice applies to all citizens. He also believes that those who harm society should make amends through acts that affirm life, not death.

For Pope Francis, the dignity of the human person and the sanctity of life are the core values of Christianity, regardless of the circumstances.

This article, published originally in 20-18, is an updated version of an article first published in 2017.

- Human rights

- Christianity

- Death penalty

- Pope Francis

- African Americans

- Capital punishment

- Thomas Aquinas

- John Paul II

- Global perspectives

- Protestants

Admissions Officer

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Head of Evidence to Action

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Religion and the Death Penalty: a call for Reckoning – Edited by Erik C. Owens, John D. Carlson, and Eric P. Elshtain

2006, Religious Studies Review

Related Papers

Theology and Sexuality

Fiona Bowie

Religion, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 327-329

Carole Cusack

Jeannette Mulherin

The purpose of this paper is to identify and examine the ways in which traditional characteristics ascribed to Mary are used to justify women’s oppression in the Catholic Church. By isolating standard Marian attributes, I hope to clarify the differences between the Marian fantasy of what women are, what they should be and what they should aspire to, with a realistic understanding of flesh and blood human females.

Ken Ebacher

Antonia Lacey

Question Journal

Scottish Journal of Theology

Cynthia Rigby

Journal for the scientific study of religion

Anthony Stevens-Arroyo

Journal of English and Germanic Philology

Annemarie Carr

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Marian Library studies

Sr. Danielle Peters

Marian Studies

Gilbert Romero

Landas 19:1 (2005) 57-91

Antonio F . B . de Castro

Journal of Women's History

Amy Remensnyder

Journal of Global Catholicism

Ozan Can Yılmaz

Raffaello Manacorda

Andrews University Seminary Studies (AUSS)

Carina Prestes

Leonie Westenberg

Anna-Karina Hermkens

Myrto Theocharous

Katarzyna Zielinska

Journal of the American Academy of Religion

Cleo Kearns

Centre for Research on Women Jordanstown

Mary T Condren

Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies

Scandinavian Journal of History

Mette M. Ahlefeldt-Laurvig

Sage Handbook of Feminist Theory

Sian Melvill Hawthorne

Jacqueline Broad

Shanaka Mendis

Church History

Salvador Ryan

Alana Harris

Thomas Joseph White

Marian studies

Gloria Dodd

James V Spickard

Virginia Langum

Wiley-Blackwell eBooks

Mathew Schmalz

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Guided History

History Research Guides by Boston University Students

- About Guided History

- For Students

- Jewish History

- European History

- Russian History

- Law and Religion

- Other Topics

- Digital Archives

- Digital History Tools

- Other Resources

Religion and the Death Penalty

A bibliography focusing on religion, the death penalty, and the tsarnaev trial compiled collectively by hi/rn 295 religious controversies and the law , capital punishment and religion assignment.

Bedau, Hugo Adam. The Death Penalty in America: Current Controversies . New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Blecker, Robert. The Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice Among the Worst of the Worst . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Blesser, John D. Cruel And Unusual: The American Death Penalty and the Founder’s Eighth Amendment . Hanover, NH: Northeastern University Press, 2012.

Lester, David. The Death Penalty: Issues And Answers (Second Edition). Springfield, IL: C.C. Thomas, 1998.

Ogletree, Charles J., and Sarat, Austin, eds. 2012. Life Without Parole : America’s New Death Penalty? New York, NY, USA: New York University Press. (available on ProQuest ebrary)

Santoro, Anthony. Exile and Embrace: Contemporary Religious Discourse on the Death Penalty . Hanover , NH: Northeastern University Press, 2013.

Journal Articles

Bias, Thomas K., Abraham Goldberg, and Tara Hannum. “Catholics and the Death Penalty: Religion as a Filter for Political Beliefs.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 7 (2011) . (available on ProQuest)

Berg, Thomas C. “Religious Conservatives and the Death Penalty.” The William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal 9, no. 1 (2000): 31-60.

Chavez, Lyssette H. and Monica K. Miller. “Religious References In Death Sentence Phases Of Trials: Two Psychological Theories That Suggest Judicial Rulings And Assumptions May Affect Jurors.” Lewis & Clark Law Review 13 (2003): 1027-83.

Chester, Britt. “Race, Religion, and Support for the Death Penalty: A Research Note.” Justice Quarterly 15:175-91. (available on HeinOnline)

Cooey, Paula M. “Women’s Religious Conversions on Death Row: Theorizing Religion and State.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 70 (Dec. 2002): 699-717. (available on Jstor)

Davison, Douglas. “God and the Executioner: The Influence of Western Religion on the Use of the Death Penalty.” William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal 9, no. 1 (2001): 137-70.

Drinan, Robert F. “Religious Organizations and the Death Penalty.” William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal 9, no. 1 (2000): 171-78. (available on HeinOnline)

Echols, Micah. “Is the courtroom the right place for religion? Difficulties in restricting religious arguments during the sentencing phase of Pennsylvania death penalty cases: Commonwealth v. Spotz.” University of West Los Angeles Law Review 36 (2005):254-273. (available on Lexis-nexis)

Eisenberg, Theodore , Stephen P. Garvey, and Martin T. Wells. “Forecasting Life and Death: Juror Race, Religion, and Attitude toward the Death Penalty,” The Journal of Legal Studies , Vol. 30, No. 2 (June 2001), pp. 277-311. (available on Jstor)

Erskine, Hazel. “The Polls: Capital Punishment.” The Public Opinion Quarterly vol. 34, no. 2 (Summer 1970): 290-307. (available on Jstor)

Garnett, Richard. “Christian Witness, Moral Anthropology, and the Death Penalty (Symposium on Religion in the Public Square).” Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy 17(2) (2003): 541-59. (available on HeinOnline)

Grasmick, Harold G., John K. Cochran, Robert J. Bursik Jr., and M’Lou Kimpel. “Religion, Punitive Justice, and Support for the Death Penalty.” Justice Quarterly 10.2 (1993): 289-314.

Hiers, Richard H. “The death penalty and due process in biblical law.” University of Detroit Mercy Law Review, 81 (5) (2004): 751-843.

Levine, Samuel. “Capital Punishments and Religious Arguments: An Intermediate Approach.” William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal 9 , no. 1 (2000).

Loewy, Arnold H. “Religious Neutrality and the Death Penalty (mitigating circumstances) (Symposium: Religion’s Role in the Administration of the Death Penalty).” The William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal 9, no. 1 (2000): 191-200. (available on HeinOnline)

Megivern, James J. “Capital Punishment: The Curious History of Its Privileged Place in Christendom.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 147 (2003): 3-12. (available on Jstor)

Mathias, Matthew D. “The Sacralization of the Individual: Human Rights and the Abolition of the Death Penalty.” American Journal of Sociology 118 (March 2013): 1246-1283. (available on Jstor)

Miller, Monica K. and Brian H. Bornstein. “The Use of Religion in Death Penalty Sentencing Trials.” Law and Human Behavior 30, no. 6 (2006): 675-684.

Miller, Monica K., and R. David Hayward. “Religious Characteristics and the Death Penalty.” Law and Human Behavior 32, no. 2 (2007): 113-23. (available on Jstor)

Schabas, William A. “Islam and the Death Penalty.” The William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal 9, no. 1 (2000): 223-36.

Simpson, Gary J and Stephen P. Garvey. “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door: Rethinking the Role of Religion in Death Penalty Cases.” Cornell Law Review vol. 86 (2000-2001): 1090-1130. (available on HeinOnline)

Jeffery T. Ulmer, Christopher Bader and Martha Gault “Do Moral Communities Play a Role in Criminal Sentencing? Evidence from Pennsylvania.” The Sociological Quarterly , Vol. 49, No. 4 (Fall, 2008): 737-768. (available on Jstor)

Young, Robert L. “Religious Orientation, Race and Support for the Death Penalty ,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion Vol. 31, No. 1 (Mar., 1992): 76-87. (available on Jstor)

Berns, Walter. “Religion and the Death Penalty: Can’t have one without the other?” The Weekly Standard. February 8, 2008.

“Bishops say Tsarnaev should not receive death penalty.” Washington Times (AP). April 6, 2015.

Basu, Moni. “‘Dead Man Walking’ Nun: ‘Botched’ Executions Unmask a Botched System.” CNN: Fighting Death: At 75, Nuns Soul Still Stirs For Cause. August 6, 2014.

Berman, Mark. “Why the Death Penalty Is So Crucial to the Boston Marathon Bombing Trial.” Washington Post. January 6, 2015.

Biale, Rachel. “Judaism Casts Doubt on Lethal Injection.” JWeekly , January 18, 2008.

Cullen, Kevin. “Tsarnaev Trial Not about Guilt, but about Punishment.” The Boston Globe. April 8, 2015.

O’Neill, Ann. “The 13th Juror: Showdown in Watertown” CNN.com. March 21, 2015.

Rodriguez, Samuel. “Botched Oklahoma Execution Should Prompt Moral Outcry Among Evangelicals.” Time Magazine , May 5, 2014.

Shetty, Salil. “Humans Do Not Deserve Executions (Opinion)” CNN.com. April 1, 2015.

Santoro, Anthony. “If not Him, then Whom? Boston Marathon Bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and the Death Penalty. The Marginalia Review of Books. April 15, 2014.

Santoro, Anthony. “The ‘Religious Freedom’ Issue that May Cost the Accused Boston Bomber his Life.” Religion Dispatches. January 15, 2015.

Serrano, Richard A. . “Defense’s goal in Boston Marathon bombing trial: Save Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s life.” Los Angeles Times. March 19, 2015.

Shimron, Yonat. “N.C. Muslims Pleased with Death Penalty Option but Want Focus on Hate Crimes Probe.” Washington Post. March 4, 2015.

Other Sources

“Capital Punishment and Christianity.” BBC.co.uk. August 3, 2009.

“Capital Punishment and Islam.” BBC.co.uk. September 16, 2009.

“Capital Punishment and Judaism.” BBC.co.uk. July 21, 2009.

Carroll, Joseph. “Who Supports the Death Penalty?” Gallup, Inc., 16 Nov. 2004.

“The Death Penalty in Jewish Teachings.” Bend the Arc a Jewish Partnership for Justice. October 4, 2012.

Weinstein, Jack B. “Death Penalty: The Torah and Today.” deathpenaltyinfo.org. August 23, 2000.

Religious Perspectives

Christian Citizenship – The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod .

Mohler Jr., R. Albert. “Why Christians Should Support the Death Penalty.” CNN Belief Blog RSS. May 1, 2014.

Olasky, Marvin. “Five Religious Views of Capital Punishment.” World Magazine , October 15, 2013.

Search Guided History

BU Blogs | Guided History | Disclaimer | Contact Author

God and the Executioner: The Influence of Western Religion on the Use of the Death Penalty

William & Mary Bill of Rights, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2000

William & Mary Law School Research Paper No. 09-73

35 Pages Posted: 15 Feb 2011

Davison M. Douglas

William & Mary Law School

Date Written: 2001

The attitude of religious groups towards the use of capital punishment has ebbed and flowed throughout history. This essay contains an historical review of religious attitudes towards capital punishment and the influence of those attitudes on the state’s use of the death penalty. The Christian Church has expressed strong support for capital punishment throughout most of its history, but in recent decades, opposition to the death penalty within the Catholic Church and many Protestant groups has emerged. The same is true with Judaism. Despite this recent abolitionist sentiment from an array of religious institutions, there has been a divergence of opinion between the "pulpit and the pew" as the laity in the United States continues to support the death penalty in large numbers. This divergence is due in part to the declining influence of religious organizations over the social policy choices of their members. Consequently, the fate of the death penalty in the United States will most likely be resolved in the realm of the secular rather than the sacred.

Keywords: death penalty, capital punishment, religion and death penalty, Catholic Church and death penalty, Judaism and death penalty, support for death penalty, religious attitudes towards the death penalty

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Davison M. Douglas (Contact Author)

William & mary law school ( email ).

South Henry Street P.O. Box 8795 Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795 United States 757-221-3853 (Phone) 757-221-3775 (Fax)

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, william & mary law school legal studies research paper series.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Law & Society: Public Law - Crime, Criminal Law, & Punishment eJournal

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Law & Religion eJournal

Home > Journals > WMBORJ > Vol. 9 (2000-2001) > Iss. 1 (2000)

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal

Davison M. Douglas , William & Mary Law School Follow

God and the Executioner: The Influence of Western Religion on the Use of the Death Penalty

In this Essay, Professor Douglas conducts an historical review of religious attitudes toward capital punishment and the influence of those attitudes on the state's use of the death penalty. He surveys the Christian Church's strong support for capital punishment throughout most of its history, along with recent expressions of opposition from many Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish groups. Despite this recent abolitionist sentiment from an array of religious institutions, Professor Douglas notes a divergence of opinion between the "pulpit and the pew" as the laity continues to support the death penalty in large numbers. Professor Douglas accounts for this divergence by noting the declining influence of religious organizations over the social policy choices of their members. He concludes that the fate of the death penalty in America will therefore "most likely be resolved in the realm of the secular rather than the sacred"

Repository Citation

Publication information.

9 William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal 137-170 (2000)

Since October 11, 2010

Included in

Criminal Law Commons , Religion Commons

ISSN: 1065-8254 (print); 1943-135X (online)

Search the Site

Advanced Search

Journal Information

- Journal Home

- BORJ website

W&M Law Links

- Our Faculty

- The Wolf Law Library

- Receive Email Notices or RSS

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Death Penalty Can Ensure ‘Justice Is Being Done’

A top Justice Department official says for many Americans the death penalty is a difficult issue on moral, religious and policy grounds. But as a legal issue, it is straightforward.

By Jeffrey A. Rosen

Mr. Rosen is the deputy attorney general.

This month, for the first time in 17 years , the United States resumed carrying out death sentences for federal crimes.

On July 14, Daniel Lewis Lee was executed for the 1996 murder of a family, including an 8-year-old girl, by suffocating and drowning them in the Illinois Bayou after robbing them to fund a white-supremacist organization. On July 16, Wesley Purkey was executed for the 1998 murder of a teenage girl, whom he kidnapped, raped, killed, dismembered and discarded in a septic pond. The next day, Dustin Honken was executed for five murders committed in 1993, including the execution-style shooting of two young girls, their mother, and two prospective witnesses against him in a federal prosecution for methamphetamine trafficking.

The death penalty is a difficult issue for many Americans on moral, religious and policy grounds. But as a legal issue, it is straightforward. The United States Constitution expressly contemplates “capital” crimes, and Congress has authorized the death penalty for serious federal offenses since President George Washington signed the Crimes Act of 1790. The American people have repeatedly ratified that decision, including through the Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994 signed by President Bill Clinton, the federal execution of Timothy McVeigh under President George W. Bush and the decision by President Barack Obama’s Justice Department to seek the death penalty against the Boston Marathon bomber and Dylann Roof .

The recent executions reflect that consensus, as the Justice Department has an obligation to carry out the law. The decision to seek the death penalty against Mr. Lee was made by Attorney General Janet Reno (who said she personally opposed the death penalty but was bound by the law) and reaffirmed by Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder.

Mr. Purkey was prosecuted during the George W. Bush administration, and his conviction and sentence were vigorously defended throughout the Obama administration. The judge who imposed the death sentence on Mr. Honken, Mark Bennett, said that while he generally opposed the death penalty, he would not lose any sleep over Mr. Honken’s execution.

In a New York Times Op-Ed essay published on July 17 , two of Mr. Lee’s lawyers criticized the execution of their client, which they contend was carried out in a “shameful rush.” That objection overlooks that Mr. Lee was sentenced more than 20 years ago, and his appeals and other permissible challenges failed, up to and including the day of his execution.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Death Penalty From the Point of Religion Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Even though several governments are still currently practicing death penalties, globally it is viewed as an abuse of human rights. It is also evident that death sentence is not in any way correlated with stoppage of murder.

This implies that, the cases of murder have continued to increase in a very alarming rate even in those countries where death penalties are constantly applied. A very typical example is Iran where death penalties are so frequent even amongst juvenile offenders and yet the capital offences are common events in the country.

It is also very true that the real healing con not be fully granted by mere cruel killing of the offenders. This is because the key motive of undertaking death penalty is basically revenge which is not an aspect of healing. The true healing is only realized through repentance and forgiveness and not through acts of revenge.

The methods on which the killing of the alleged offender is undertaken are inhuman and ungodly and all government should undertake moratorium on the application of death penalties. A very good example is the lethal injection method which is practiced in United States of America. This method has proven beyond reasonable doubts that there is evidence of cruel and lengthy death in its usage.

This is a big mockery to human rights and dignity of human life. In this case we are going to look at various reasons against the death penalty practice. The views of various religious groups will also be visited (Stephen, 2009, p. 1). Finally the enormous contributions of international organizations in fight against the practice of death penalties by various governments globally will also be seen.

There are various reasons against the death penalty practices. One among these reasons is the mere fact that the costs of the death penalty are too huge. This is because of the sensitivity and weight which death sentence carries.

Thus this calls for adequate lengthy procedures of law to be followed which are too costly from the time of arrest to the point of execution. These costs are compared to an alternative form of administering justice which is life imprisonment. It is a documented fact that administering life sentence is far much cheaper compared to death penalty.

Thus, this has led to public outcry to replace death penalty with life sentence with no possibility of the victims being granted parole. Secondly, the mentorship services offered by inmates on life sentence who could have otherwise been hanged are very vital.

This has been quite evident in the correctional institutes commonly known as prisons. Most of these inmates who could have been removed from death rows to life sentence are quite instrumental in mentorship especially after undergoing spiritual re-formation. These inmates usually involve themselves with helping the young men and women to undergo a successful process of rehabilitation.

This mentorship services are usually most effective if the correctional institutions are undertaking vital programs such as drug treatment, education programs, spiritual and moral programs. Thus, life imprisonment leads to positive utilisation of the inmates who could have be killed under the practice of death penalty.

The other reasons may also include the observance of the logical ethics of life .in this case every person has a basic right which is right to life. This basic right must be universal to all people.

Also it should be noted that the right to life should be treated sacred as much as possible. The basic right to life should not be subject to forfeiture. Secondly, the impacts of the death penalty are too severe on the lives of the victims’ families and close kinsmen and on the settlement of the case. It is also evident that death penalty only continues the cycle of violence by killing another person.

The truth of the matter is that the needs of the affected family cannot be adequately addressed to the errors of judicially. Thirdly, there is sufficient and adequate evidence that the courts have continued to rely on the discretion of the judges. Thus, such decisions from some judges are biased. This is because the alleged person may emerge to be innocent after through scrutiny of the evidence.

There are several cases where by after undertaking DNA evidences many people have been found to have faced death penalty innocently. Thus, it is argued that it is far much better to acquit thousands of people on life sentence than to kill an innocent person due of these judges can be biased due to personal interests vested on specific cases. It is also true that some people are unfairly in prison.

Thus, implementing death penalty on such unfair grounds will mean gross abuse of human rights and disrespect to human dignity and sanctity of human life. It is also feared that several governments have continued to use death penalty to silence their opponents. This is evident in Iraq whereby political rivals have been subjected to death penalty by the government of the day.

The list of reasons why we should totally abolish the death penalty in all countries globally is endless. First, it is a proven evidence that death sentence does not stop the perpetuation of crime. This is clearly seen in Iran where death penalties are frequently administered but no impact is felt on crime reduction.

Thus, an alternative method is highly effective and recommended. This is because an alternative method such as life imprisonment can create an opportunity of rehabilitation. In this case the inmates who are on life sentence can offer mentorship to other inmates.

This makes people to co-exist with others well when out of prison for fear of going back in prison for good. Thus, the cases of crime will definitely go down due to successful rehabilitation of inmates. Secondly, the methods of execution are wild. For example the lethal injection method is proven to amount to cruel and delayed death which is inhuman (Browne, 2002, p. 1).

The practice of death penalty is unbiblical and immoral. Even though some people may try to justify death penalty from scriptures in the Old Testament it still remains unbiblical. This is because it is a common knowledge from the teachings of Jesus Christ that everybody is given a chance to understand the value attached to human life. Thus, need to preserve and respect life under all situations.

In Christianity, several affiliate religious groups have varying opinions on the issue of death penalty. Despite all this, it is very clear from the teachings of Jesus Christ in the New Testament that human life must be respected. This is seen when Jesus confronted the people who wanted to stone the adulterous women.

Also the action of Jesus in forgiving the thief whom he was crucified with on the cross clearly shows that shows Christianity does not condone death penalty. The Roman Catholic Church has a very controversial opinion as it regards to death penalty.

This church strongly believes that the Jesus’ teachings on doctrine of peace relates only to personal ethics. The Roman Catholic Church believes that the civil government has a duty to punish the crimes perpetuated by any person in the best way it opts. This is contrary to the commandment which stipulates that one should not kill another person or help in the deliberate termination of human life (Robinson, 2010, p. 1).

In the Buddhism religion it is very clear that death penalty is condemned. This is well demonstrated by chapter ten on the dhammapada. It is shown that everyone fears suffering, punishment and above all everyone has extreme fear for death. This chapter goes ahead and states that one should not kill or cause death of another person.

The love for life is highly emphasized in this chapter. Also the first five precepts of Buddhism teach their own followers the need to abstain from deliberate attempt on destruction of life. The chapter twenty six of the dhammapada goes ahead and declares a person who is abrahimin. It says that abrahimin is a person who has dropped weapons and condemned violence against all human beings. This emphasizes the need for not killing or helping to kill under all circumstances.

It is now clear that majority of religious group are built on foundations which strongly condemn death penalty. An exception is Islam which advocate for death penalty most especially on cases of adultery. But this practice is drastically losing popularity amongst Muslim community because it is unfairly administered (Brandon, 2009, p. 37). Evidence shows that it is only women who are affected by adultery in which they are mercilessly stoned to death in front of large crowd.

The international organisations have continued in their efforts to get rid of death penalty. For example the United Nations has established various resolutions in its assembly in view of establishing moratorium. The moratorium on the usage of death penalty by various governments is aimed at stopping the death sentence. The European Union has put some entry conditions on its members on issues of the death penalty. Thus, the countries who are members of European Union are not expected to practice death penalty.

The miscarriage of justice has been evident in the process of implementing the death penalty. In this case several innocent people have been put to a miserable end by capital punishment. The death penalty is noted to have completely been administered unfairly upon the disadvantaged groups in the society. It is a common argument that death penalty falls on those without good lawyers to represent them.

This evidently puts the marginalised groups to be victims of this death sentences. Examples of these groups of people include the poor, mentally challenged, illiterate and religious minorities. It is for this grave concern that all governments should abolish death penalty. Also, this calls for an alternative method of administering justice. The life imprisonment is highly preferred under these circumstances.

This is for the reason of preserving the divine dignity of human life and also at the same time to punish the offenders accordingly. In this case we have addressed reasons against death penalty. The various views from religious groups and international organisations pertaining death penalty have also been discussed.

Bibliography

Brandon, C. (2009). The Electric Chair: An Unnatural American History . California. Wadsworth Publishers.

Browne, A. (2002). Death penalty abolished on all British territory . Web.

Robinson, B. (2010). Capital Punishment: All viewpoints on the death penalty . Web.

Stephen, M. (2009). History of UK Capital Punishment . Web.

- Daniel Valerio Child Abuse

- Violent Crime: Rape and Sexual Assault

- Facets of the Death Penalty

- Administering a UNIX User Environment

- Development Theories Applied to Ted Kaczynski and Alice Walker

- The Practice of Death Penalty

- Simpson ‘S Criminal Case

- Prevention of Date Rapes With the SARA Model

- Rewards and Punishments based on Relative Deserts: A Critical Analysis of Pojman’s Proposition

- The Aurora Gun Issue Overview

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 4). Death Penalty From the Point of Religion. https://ivypanda.com/essays/death-penalty/

"Death Penalty From the Point of Religion." IvyPanda , 4 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/death-penalty/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Death Penalty From the Point of Religion'. 4 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Death Penalty From the Point of Religion." July 4, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/death-penalty/.

1. IvyPanda . "Death Penalty From the Point of Religion." July 4, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/death-penalty/.

IvyPanda . "Death Penalty From the Point of Religion." July 4, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/death-penalty/.

Religious Values and Death Penalty

This essay will explore the relationship between religious values and the death penalty. It will discuss various religious perspectives on capital punishment and how these beliefs influence the ethical debate on this issue. PapersOwl offers a variety of free essay examples on the topic of Crime.

How it works

Religious and moral values tell us that killing is wrong. Thou shall not kill. To me, the death penalty is inhumane. Killing people makes us like the murderers that most of us despise. No imperfect system should have the right to decide who lives and who dies. The government is made up of imperfect humans, who make mistakes. The only person that should be able to take life, is god.

“An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind”. (Gandhi) Two wrongs do not make a right.

You simply can’t justify a wrong by doing something equally as wrong. I believe everyone deserves a second chance. I think many people are on death row and in our prisons because they never got any first chances. The death penalty doesn’t seem to recognize that guilty people have the possibility to change, and it rejects their chance to ever rejoin and contribute to society.

Anyone can change and be rehabilitated. We live in troubling times and the easiest path would be to get rid of criminals altogether but imagine a world where we can change lives instead of taking them. You cannot introduce new ideas into someone’s head by chopping it off.

The risk of executing innocent people exists in any imperfect justice system. Since 1973, 123 people in 25 states have been released from death row with evidence of innocence. Innocent people are imprisoned and executed all the time. As in ‘Just Mercy, police officers and prosecutors, whether they are under pressure from the public, or trying to further their careers, seem to make quick arrests and completely ignore evidence that might point to innocence. There have been and always will be cases of executions of innocent people. No matter how developed a justice system seems to be, it will always remain at risk for human failure. Unlike prison sentences, where people can be released upon new evidence, the death penalty is permanent and non-reparable.

The death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment. I read that In April 2005, in (The Lancet) a team of medical researchers found flaws in how lethal injections were being given, which caused extreme suffering to the person being executed. The report found “that in 43 of the 49 executed prisoners studied the anesthetic administered during lethal injection was lower than required for surgery. In 43 percent of cases, drug levels were consistent with awareness.”

Here is an article I read on botched executions. “On December 13, 2006, a man named Angel Nieves Diaz was the victim of a botched execution so terrible that it led Florida’s Republican Governor and death penalty enthusiast Jeb Bush to issue an executive order halting executions in the state. Technicians wrongly inserted the needles carrying the poisons that were to kill Diaz. The chemicals poured into his soft tissues instead of his veins. This left Diaz struggling and mouthing words in pain for over 34 minutes, when a second set of needles were inserted. The county medical examiner found 12-inch chemical burns inside both of his arms after the execution”. I also watched a video at home of a prisoner with a botched execution and it was horrific to watch, and it actually brought tears to my eyes.

Cite this page

Religious values and Death penalty. (2020, Mar 23). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/religious-values-and-death-penalty/

"Religious values and Death penalty." PapersOwl.com , 23 Mar 2020, https://papersowl.com/examples/religious-values-and-death-penalty/

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Religious values and Death penalty . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/religious-values-and-death-penalty/ [Accessed: 4 Sep. 2024]

"Religious values and Death penalty." PapersOwl.com, Mar 23, 2020. Accessed September 4, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/religious-values-and-death-penalty/

"Religious values and Death penalty," PapersOwl.com , 23-Mar-2020. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/religious-values-and-death-penalty/. [Accessed: 4-Sep-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2020). Religious values and Death penalty . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/religious-values-and-death-penalty/ [Accessed: 4-Sep-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Opinion Polls: Death Penalty Support and Religious Views

- Facebook Share

- Tweet Tweet

- Email Email

Pew Research Center: Atheists and Agnostics Tend to Support Death Penalty Less Than Other Religious Groups

According to a Pew Research Center survey from April 2021, a majority of adults in the United States support the use of the death penalty for individuals convicted of murder, but these views tend to vary by religion. Approximately two-thirds of atheists and six-in-ten agnostics are at least ‘somewhat’ opposed to the use of capital punishment for those convicted of murder, while 60% of U.S. adults favors the death penalty. For particular religious groups, this support is even higher: roughly 75% of white Evangelicals and Protestants favor capital punishment, as well as 61% of Hispanic Catholics. For Black Protestants, capital punishment is a divisive issue, with 50% supporting its use and 47% opposing its use. This division reflects the overall lower support for the death penalty among Black Americans, regardless of religiosity.

The survey also addresses moral qualms about the use of the death penalty, whether capital punishment has a deterrent effect, whether sentencing for the same crime varies by race, and whether there are adequate protections to prevent against the execution of an innocent person. Amongst this set of answers, approximately half of the atheists and agnostics believe the death penalty is morally unjustifiable, while less than a quarter of the white Protestants and evangelicals shared the same sentiment. According to Sarah Kramer, “generally speaking, people with any religious affiliation are more likely than those without one to say that the threat of the death penalty deters serious crime.” The survey revealed a large difference in whether each group thinks the death penalty is applied equally by race. Nearly 90% of Black Protestants believe that Black people are more likely than White people to be sentenced to death for crimes with similar circumstances, while almost 70% of white evangelicals believe the death penalty is equally applied to white and Black people. This number was lesser among white non-evangelicals (53%) and Catholics (47%). Every religious group that participated in the survey agreed, with large majorities, that there is some risk associated with an innocent person being put to death in the United States.

S. Kramer, Unlike other U.S. religious groups, most atheists and agnostics oppose the death penalty (June 15, 2021)

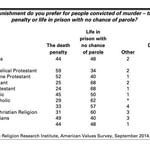

2014 Public Religion Research Institute Poll Finds That Most Religious Affiliations in the United States Prefer Life in Prison Without Parole to the Death Penalty