- Privacy Policy

Home » References in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

References in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

References in Research

Definition:

References in research are a list of sources that a researcher has consulted or cited while conducting their study. They are an essential component of any academic work, including research papers, theses, dissertations, and other scholarly publications.

Types of References

There are several types of references used in research, and the type of reference depends on the source of information being cited. The most common types of references include:

References to books typically include the author’s name, title of the book, publisher, publication date, and place of publication.

Example: Smith, J. (2018). The Art of Writing. Penguin Books.

Journal Articles

References to journal articles usually include the author’s name, title of the article, name of the journal, volume and issue number, page numbers, and publication date.

Example: Johnson, T. (2021). The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health. Journal of Psychology, 32(4), 87-94.

Web sources

References to web sources should include the author or organization responsible for the content, the title of the page, the URL, and the date accessed.

Example: World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

Conference Proceedings

References to conference proceedings should include the author’s name, title of the paper, name of the conference, location of the conference, date of the conference, and page numbers.

Example: Chen, S., & Li, J. (2019). The Future of AI in Education. Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Technology, Beijing, China, July 15-17, pp. 67-78.

References to reports typically include the author or organization responsible for the report, title of the report, publication date, and publisher.

Example: United Nations. (2020). The Sustainable Development Goals Report. United Nations.

Formats of References

Some common Formates of References with their examples are as follows:

APA (American Psychological Association) Style

The APA (American Psychological Association) Style has specific guidelines for formatting references used in academic papers, articles, and books. Here are the different reference formats in APA style with examples:

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example : Smith, J. K. (2005). The psychology of social interaction. Wiley-Blackwell.

Journal Article

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page numbers.

Example : Brown, L. M., Keating, J. G., & Jones, S. M. (2012). The role of social support in coping with stress among African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 218-233.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication or last update). Title of page. Website name. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, December 11). COVID-19: How to protect yourself and others. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

Magazine article

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of Magazine, volume number(issue number), page numbers.

Example : Smith, M. (2019, March 11). The power of positive thinking. Psychology Today, 52(3), 60-65.

Newspaper article:

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of Newspaper, page numbers.

Example: Johnson, B. (2021, February 15). New study shows benefits of exercise on mental health. The New York Times, A8.

Edited book

Editor, E. E. (Ed.). (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example : Thompson, J. P. (Ed.). (2014). Social work in the 21st century. Sage Publications.

Chapter in an edited book:

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of chapter. In E. E. Editor (Ed.), Title of book (pp. page numbers). Publisher.

Example : Johnson, K. S. (2018). The future of social work: Challenges and opportunities. In J. P. Thompson (Ed.), Social work in the 21st century (pp. 105-118). Sage Publications.

MLA (Modern Language Association) Style

The MLA (Modern Language Association) Style is a widely used style for writing academic papers and essays in the humanities. Here are the different reference formats in MLA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Smith, John. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Journal article

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal, volume number, issue number, Publication year, page numbers.

Example : Brown, Laura M., et al. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol. 22, no. 1, 2012, pp. 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name, Publication date, URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC, 11 Dec. 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Publication date, page numbers.

Example : Smith, Mary. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, Mar. 2019, pp. 60-65.

Newspaper article

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Publication date, page numbers.

Example : Johnson, Bob. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, 15 Feb. 2021, p. A8.

Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Thompson, John P., editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. Sage Publications, 2014.

Chapter in an edited book

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last name, Publisher, Publication year, page numbers.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, Sage Publications, 2014, pp. 105-118.

Chicago Manual of Style

The Chicago Manual of Style is a widely used style for writing academic papers, dissertations, and books in the humanities and social sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Chicago style:

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number, no. issue number (Publication year): page numbers.

Example : Brown, Laura M., John G. Keating, and Sarah M. Jones. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 22, no. 1 (2012): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. Publication date. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Publication date.

Example : Smith, Mary. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 2019.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Publication date.

Example : Johnson, Bob. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Example : Thompson, John P., ed. Social Work in the 21st Century. Sage Publications, 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, page numbers. Publisher, Publication year.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, 105-118. Sage Publications, 2014.

Harvard Style

The Harvard Style, also known as the Author-Date System, is a widely used style for writing academic papers and essays in the social sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Harvard Style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Smith, John. 2005. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number (issue number): page numbers.

Example: Brown, Laura M., John G. Keating, and Sarah M. Jones. 2012. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 22 (1): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL. Accessed date.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed April 1, 2023.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, month and date of publication.

Example : Smith, Mary. 2019. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 2019.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, month and date of publication.

Example : Johnson, Bob. 2021. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Year of publication. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Thompson, John P., ed. 2014. Social Work in the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of publication. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s First Name Last Name, page numbers. Place of publication: Publisher.

Example : Johnson, Karen S. 2014. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by John P. Thompson, 105-118. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Vancouver Style

The Vancouver Style, also known as the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals, is a widely used style for writing academic papers in the biomedical sciences. Here are the different reference formats in Vancouver Style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Abbreviated Journal Title. Year of publication; volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Example : Brown LM, Keating JG, Jones SM. The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents. J Res Adolesc. 2012;22(1):218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Webpage. Website Name [Internet]. Publication date. [cited date]. Available from: URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others [Internet]. 2020 Dec 11. [cited 2023 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Title of Magazine. Year of publication; month and day of publication:page numbers.

Example : Smith M. The Power of Positive Thinking. Psychology Today. 2019 Mar 1:32-35.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Title of Newspaper. Year of publication; month and day of publication:page numbers.

Example : Johnson B. New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health. The New York Times. 2021 Feb 15:A4.

Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Thompson JP, editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Chapter. In: Editor’s Last name, First name, editor. Title of Book. Edition number. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication. page numbers.

Example : Johnson KS. The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities. In: Thompson JP, editor. Social Work in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. p. 105-118.

Turabian Style

Turabian style is a variation of the Chicago style used in academic writing, particularly in the fields of history and humanities. Here are the different reference formats in Turabian style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Smith, John K. The Psychology of Social Interaction. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal volume number, no. issue number (Year of publication): page numbers.

Example : Brown, LM, Keating, JG, Jones, SM. “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Stress among African American Adolescents.” J Res Adolesc 22, no. 1 (2012): 218-233.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Name of Website. Publication date. Accessed date. URL.

Example : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19: How to Protect Yourself and Others.” CDC. December 11, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine, Month Day, Year of publication, page numbers.

Example : Smith, M. “The Power of Positive Thinking.” Psychology Today, March 1, 2019, 32-35.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper, Month Day, Year of publication.

Example : Johnson, B. “New Study Shows Benefits of Exercise on Mental Health.” The New York Times, February 15, 2021.

Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Thompson, JP, ed. Social Work in the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Chapter.” In Title of Book, edited by Editor’s Last name, First name, page numbers. Place of publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Johnson, KS. “The Future of Social Work: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Social Work in the 21st Century, edited by Thompson, JP, 105-118. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014.

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) Style

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) style is commonly used in engineering, computer science, and other technical fields. Here are the different reference formats in IEEE style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of publication.

Example : Oppenheim, A. V., & Schafer, R. W. Discrete-Time Signal Processing. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2010.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Article.” Abbreviated Journal Title, vol. number, no. issue number, pp. page numbers, Month year of publication.

Example: Shannon, C. E. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 379-423, July 1948.

Conference paper

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Paper.” In Title of Conference Proceedings, Place of Conference, Date of Conference, pp. page numbers, Year of publication.

Example: Gupta, S., & Kumar, P. “An Improved System of Linear Discriminant Analysis for Face Recognition.” In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology, Harbin, China, Dec. 2011, pp. 144-147.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Webpage.” Name of Website. Date of publication or last update. Accessed date. URL.

Example : National Aeronautics and Space Administration. “Apollo 11.” NASA. July 20, 1969. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/apollo11.html.

Technical report

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Report.” Name of Institution or Organization, Report number, Year of publication.

Example : Smith, J. R. “Development of a New Solar Panel Technology.” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, NREL/TP-6A20-51645, 2011.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Patent.” Patent number, Issue date.

Example : Suzuki, H. “Method of Producing Carbon Nanotubes.” US Patent 7,151,019, December 19, 2006.

Standard Title. Standard number, Publication date.

Example : IEEE Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic. IEEE Std 754-2008, August 29, 2008

ACS (American Chemical Society) Style

ACS (American Chemical Society) style is commonly used in chemistry and related fields. Here are the different reference formats in ACS style:

Author’s Last name, First name; Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. Abbreviated Journal Title Year, Volume, Page Numbers.

Example : Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cui, Y.; Ma, Y. Facile Preparation of Fe3O4/graphene Composites Using a Hydrothermal Method for High-Performance Lithium Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2715-2721.

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title; Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication.

Example : Carey, F. A. Organic Chemistry; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2008.

Author’s Last name, First name. Chapter Title. In Book Title; Editor’s Last name, First name, Ed.; Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication; Volume number, Chapter number, Page Numbers.

Example : Grossman, R. B. Analytical Chemistry of Aerosols. In Aerosol Measurement: Principles, Techniques, and Applications; Baron, P. A.; Willeke, K., Eds.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 2001; Chapter 10, pp 395-424.

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Webpage. Website Name, URL (accessed date).

Example : National Institute of Standards and Technology. Atomic Spectra Database. https://www.nist.gov/pml/atomic-spectra-database (accessed April 1, 2023).

Author’s Last name, First name. Patent Number. Patent Date.

Example : Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, W. US Patent 9,999,999, December 31, 2022.

Author’s Last name, First name; Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Article. In Title of Conference Proceedings, Publisher: Place of Publication, Year of Publication; Volume Number, Page Numbers.

Example : Jia, H.; Xu, S.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Huang, X. Fast Adsorption of Organic Pollutants by Graphene Oxide. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2017; Volume 1, pp 223-228.

AMA (American Medical Association) Style

AMA (American Medical Association) style is commonly used in medical and scientific fields. Here are the different reference formats in AMA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Article Title. Journal Abbreviation. Year; Volume(Issue):Page Numbers.

Example : Jones, R. A.; Smith, B. C. The Role of Vitamin D in Maintaining Bone Health. JAMA. 2019;321(17):1765-1773.

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : Guyton, A. C.; Hall, J. E. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

Author’s Last name, First name. Chapter Title. In: Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: Page Numbers.

Example: Rajakumar, K. Vitamin D and Bone Health. In: Holick, M. F., ed. Vitamin D: Physiology, Molecular Biology, and Clinical Applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:211-222.

Author’s Last name, First name. Webpage Title. Website Name. URL. Published date. Updated date. Accessed date.

Example : National Cancer Institute. Breast Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)–Patient Version. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/patient/breast-prevention-pdq. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed April 1, 2023.

Author’s Last name, First name. Conference presentation title. In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Place of Conference.

Example : Smith, J. R. Vitamin D and Bone Health: A Meta-Analysis. In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; September 20-23, 2022; San Diego, CA.

Thesis or dissertation

Author’s Last name, First name. Title of Thesis or Dissertation. Degree level [Doctoral dissertation or Master’s thesis]. University Name; Year.

Example : Wilson, S. A. The Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Bone Health in Postmenopausal Women [Doctoral dissertation]. University of California, Los Angeles; 2018.

ASCE (American Society of Civil Engineers) Style

The ASCE (American Society of Civil Engineers) style is commonly used in civil engineering fields. Here are the different reference formats in ASCE style:

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Journal Title, volume number, issue number (year): page numbers. DOI or URL (if available).

Example : Smith, J. R. “Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Drainage Systems in Urban Areas.” Journal of Environmental Engineering, vol. 146, no. 3 (2020): 04020010. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0001668.

Example : McCuen, R. H. Hydrologic Analysis and Design. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2013.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Chapter Title.” In: Editor’s Last name, First name, ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: page numbers.

Example : Maidment, D. R. “Floodplain Management in the United States.” In: Shroder, J. F., ed. Treatise on Geomorphology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2013: 447-460.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Paper Title.” In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Location. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year: page numbers.

Example: Smith, J. R. “Sustainable Drainage Systems for Urban Areas.” In: Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure; November 6-9, 2019; Los Angeles, CA. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers; 2019: 156-163.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Report Title.” Report number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “Hurricane Sandy Coastal Risk Reduction Program, New York and New Jersey.” Report No. P-15-001. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; 2015.

CSE (Council of Science Editors) Style

The CSE (Council of Science Editors) style is commonly used in the scientific and medical fields. Here are the different reference formats in CSE style:

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Article Title.” Journal Title. Year;Volume(Issue):Page numbers.

Example : Smith, J.R. “Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Drainage Systems in Urban Areas.” Journal of Environmental Engineering. 2020;146(3):04020010.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Chapter Title.” In: Editor’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial., ed. Book Title. Edition number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year:Page numbers.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Paper Title.” In: Conference Title; Conference Date; Location. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example : Smith, J.R. “Sustainable Drainage Systems for Urban Areas.” In: Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure; November 6-9, 2019; Los Angeles, CA. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers; 2019.

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Report Title.” Report number. Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Bluebook Style

The Bluebook style is commonly used in the legal field for citing legal documents and sources. Here are the different reference formats in Bluebook style:

Case citation

Case name, volume source page (Court year).

Example : Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Statute citation

Name of Act, volume source § section number (year).

Example : Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7401 (1963).

Regulation citation

Name of regulation, volume source § section number (year).

Example: Clean Air Act, 40 C.F.R. § 52.01 (2019).

Book citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. Book Title. Edition number (if applicable). Place of Publication: Publisher; Year.

Example: Smith, J.R. Legal Writing and Analysis. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Aspen Publishers; 2015.

Journal article citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Article Title.” Journal Title. Volume number (year): first page-last page.

Example: Garcia, C. “The Right to Counsel: An International Comparison.” International Journal of Legal Information. 43 (2015): 63-94.

Website citation

Author’s Last name, First Initial. Middle Initial. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed month day, year).

Example : United Nations. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Oxford Style

The Oxford style, also known as the Oxford referencing system or the documentary-note citation system, is commonly used in the humanities, including literature, history, and philosophy. Here are the different reference formats in Oxford style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Smith, John. The Art of Writing. New York: Penguin, 2020.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Journal Title volume, no. issue (year): page range.

Example: Garcia, Carlos. “The Role of Ethics in Philosophy.” Philosophy Today 67, no. 3 (2019): 53-68.

Chapter in an edited book citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Chapter Title.” In Book Title, edited by Editor’s Name, page range. Place of Publication: Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Lee, Mary. “Feminism in the 21st Century.” In The Oxford Handbook of Feminism, edited by Jane Smith, 51-69. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Author’s Last name, First name. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed day month year).

Example : Jones, David. “The Importance of Learning Languages.” Oxford Language Center. https://www.oxfordlanguagecenter.com/importance-of-learning-languages/ (accessed 3 January 2023).

Dissertation or thesis citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of Dissertation/Thesis.” PhD diss., University Name, Year of Publication.

Example : Brown, Susan. “The Art of Storytelling in American Literature.” PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2020.

Newspaper article citation

Author’s Last name, First name. “Article Title.” Newspaper Title, Month Day, Year.

Example : Robinson, Andrew. “New Developments in Climate Change Research.” The Guardian, September 15, 2022.

AAA (American Anthropological Association) Style

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) style is commonly used in anthropology research papers and journals. Here are the different reference formats in AAA style:

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. Book Title. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example : Smith, John. 2019. The Anthropology of Food. New York: Routledge.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Article Title.” Journal Title volume, no. issue: page range.

Example : Garcia, Carlos. 2021. “The Role of Ethics in Anthropology.” American Anthropologist 123, no. 2: 237-251.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Chapter Title.” In Book Title, edited by Editor’s Name, page range. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example: Lee, Mary. 2018. “Feminism in Anthropology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Feminism, edited by Jane Smith, 51-69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Page Title.” Website Title. URL (accessed day month year).

Example : Jones, David. 2020. “The Importance of Learning Languages.” Oxford Language Center. https://www.oxfordlanguagecenter.com/importance-of-learning-languages/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Title of Dissertation/Thesis.” PhD diss., University Name.

Example : Brown, Susan. 2022. “The Art of Storytelling in Anthropology.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley.

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Article Title.” Newspaper Title, Month Day.

Example : Robinson, Andrew. 2021. “New Developments in Anthropology Research.” The Guardian, September 15.

AIP (American Institute of Physics) Style

The American Institute of Physics (AIP) style is commonly used in physics research papers and journals. Here are the different reference formats in AIP style:

Example : Johnson, S. D. 2021. “Quantum Computing and Information.” Journal of Applied Physics 129, no. 4: 043102.

Example : Feynman, Richard. 2018. The Feynman Lectures on Physics. New York: Basic Books.

Example : Jones, David. 2020. “The Future of Quantum Computing.” In The Handbook of Physics, edited by John Smith, 125-136. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Conference proceedings citation

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. “Title of Paper.” Proceedings of Conference Name, date and location: page range. Place of Publication: Publisher.

Example : Chen, Wei. 2019. “The Applications of Nanotechnology in Solar Cells.” Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Nanotechnology, July 15-17, Tokyo, Japan: 224-229. New York: AIP Publishing.

Example : American Institute of Physics. 2022. “About AIP Publishing.” AIP Publishing. https://publishing.aip.org/about-aip-publishing/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

Patent citation

Author’s Last name, First name. Year of Publication. Patent Number.

Example : Smith, John. 2018. US Patent 9,873,644.

References Writing Guide

Here are some general guidelines for writing references:

- Follow the citation style guidelines: Different disciplines and journals may require different citation styles (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). It is important to follow the specific guidelines for the citation style required.

- Include all necessary information : Each citation should include enough information for readers to locate the source. For example, a journal article citation should include the author(s), title of the article, journal title, volume number, issue number, page numbers, and publication year.

- Use proper formatting: Citation styles typically have specific formatting requirements for different types of sources. Make sure to follow the proper formatting for each citation.

- Order citations alphabetically: If listing multiple sources, they should be listed alphabetically by the author’s last name.

- Be consistent: Use the same citation style throughout the entire paper or project.

- Check for accuracy: Double-check all citations to ensure accuracy, including correct spelling of author names and publication information.

- Use reputable sources: When selecting sources to cite, choose reputable and authoritative sources. Avoid sources that are biased or unreliable.

- Include all sources: Make sure to include all sources used in the research, including those that were not directly quoted but still informed the work.

- Use online tools : There are online tools available (e.g., citation generators) that can help with formatting and organizing references.

Purpose of References in Research

References in research serve several purposes:

- To give credit to the original authors or sources of information used in the research. It is important to acknowledge the work of others and avoid plagiarism.

- To provide evidence for the claims made in the research. References can support the arguments, hypotheses, or conclusions presented in the research by citing relevant studies, data, or theories.

- To allow readers to find and verify the sources used in the research. References provide the necessary information for readers to locate and access the sources cited in the research, which allows them to evaluate the quality and reliability of the information presented.

- To situate the research within the broader context of the field. References can show how the research builds on or contributes to the existing body of knowledge, and can help readers to identify gaps in the literature that the research seeks to address.

Importance of References in Research

References play an important role in research for several reasons:

- Credibility : By citing authoritative sources, references lend credibility to the research and its claims. They provide evidence that the research is based on a sound foundation of knowledge and has been carefully researched.

- Avoidance of Plagiarism : References help researchers avoid plagiarism by giving credit to the original authors or sources of information. This is important for ethical reasons and also to avoid legal repercussions.

- Reproducibility : References allow others to reproduce the research by providing detailed information on the sources used. This is important for verification of the research and for others to build on the work.

- Context : References provide context for the research by situating it within the broader body of knowledge in the field. They help researchers to understand where their work fits in and how it builds on or contributes to existing knowledge.

- Evaluation : References provide a means for others to evaluate the research by allowing them to assess the quality and reliability of the sources used.

Advantages of References in Research

There are several advantages of including references in research:

- Acknowledgment of Sources: Including references gives credit to the authors or sources of information used in the research. This is important to acknowledge the original work and avoid plagiarism.

- Evidence and Support : References can provide evidence to support the arguments, hypotheses, or conclusions presented in the research. This can add credibility and strength to the research.

- Reproducibility : References provide the necessary information for others to reproduce the research. This is important for the verification of the research and for others to build on the work.

- Context : References can help to situate the research within the broader body of knowledge in the field. This helps researchers to understand where their work fits in and how it builds on or contributes to existing knowledge.

- Evaluation : Including references allows others to evaluate the research by providing a means to assess the quality and reliability of the sources used.

- Ongoing Conversation: References allow researchers to engage in ongoing conversations and debates within their fields. They can show how the research builds on or contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Background of The Study – Examples and Writing...

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

Purpose of Research – Objectives and Applications

Dissertation vs Thesis – Key Differences

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and...

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing...

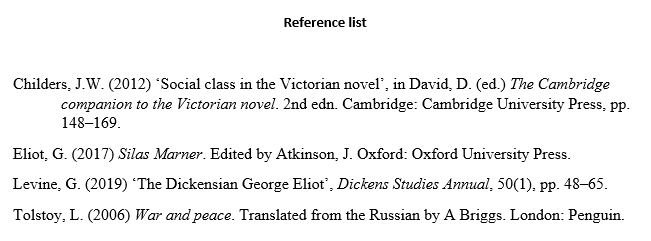

Write it Right - A guide to Harvard referencing style

- Referencing

- Referencing & Citing

- Paraphrasing

The Reference List

Differences between a reference list and a bibliography, compiling your reference list or bibliography.

- Elements in References

- Journal articles

- Online journals

- Newspaper articles

- Online newspapers

- Internet sources

- Government and legal publications

- Patents and standards

- Miscellaneous

- The reference list is a detailed list of all the sources that you have cited within your work, including books, eBooks, journal articles, theses, webpages etc.

- Items are listed in alphabetical order in the reference list according to the main author/editor’s surname.

- This means that regardless of the order in which the in-text citations appear within your work, these items are all listed alphabetically by author/editor in the reference list.

- This explains why the Harvard referencing style is also known as the ‘author-date’ style.

- The reference list is an alphabetical list of all the sources that you cited in the text of your assignment.

- A bibliography is a separate list, presented in the same format as a reference list, however, it includes all the sources you consulted in the preparation of your assignment, not just those you cited.

- In other words, a bibliography presents the same items as a reference list, but it also includes references to all the additional research you carried out, so it shows your extra effort.

- All in-text references must be included in an alphabetical list, by author/editor’s surname, at the end of the work. As stated earlier, this is known as the reference list. A bibliography is a list of all works you used in preparation of the work, but which were not necessarily cited/referred to.

- This list must not be numbered.

- When there is no author/editor, use the title (book, journal, newspaper etc.)

- References in your reference list must be a full description of the in–text citations.

- If there is more than one publication by the same author, arrange the works in chronological order.

- In your reference list/bibliography the following abbreviations are accepted:

- (ed.) editor - (eds) editors - col. column - comp(s). compiler/compilers - edn. edition - et al. and others - n.d. no knowledge of the date - no. number - par. paragraph - s.l. no place of publication - s.n. publisher unknown - vol. volume

- << Previous: Paraphrasing

- Next: Elements in References >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 10:19 AM

- URL: https://lit.libguides.com/Write-it-Right

The Library, Technological University of the Shannon: Midwest

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 15 September 2023.

Referencing is an important part of academic writing. It tells your readers what sources you’ve used and how to find them.

Harvard is the most common referencing style used in UK universities. In Harvard style, the author and year are cited in-text, and full details of the source are given in a reference list .

| In-text citation | Referencing is an essential academic skill (Pears and Shields, 2019). |

| Reference list entry | Pears, R. and Shields, G. (2019) 11th edn. London: MacMillan. |

Harvard Reference Generator

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Harvard in-text citation, creating a harvard reference list, harvard referencing examples, referencing sources with no author or date, frequently asked questions about harvard referencing.

A Harvard in-text citation appears in brackets beside any quotation or paraphrase of a source. It gives the last name of the author(s) and the year of publication, as well as a page number or range locating the passage referenced, if applicable:

Note that ‘p.’ is used for a single page, ‘pp.’ for multiple pages (e.g. ‘pp. 1–5’).

An in-text citation usually appears immediately after the quotation or paraphrase in question. It may also appear at the end of the relevant sentence, as long as it’s clear what it refers to.

When your sentence already mentions the name of the author, it should not be repeated in the citation:

Sources with multiple authors

When you cite a source with up to three authors, cite all authors’ names. For four or more authors, list only the first name, followed by ‘ et al. ’:

| Number of authors | In-text citation example |

|---|---|

| 1 author | (Davis, 2019) |

| 2 authors | (Davis and Barrett, 2019) |

| 3 authors | (Davis, Barrett and McLachlan, 2019) |

| 4+ authors | (Davis , 2019) |

Sources with no page numbers

Some sources, such as websites , often don’t have page numbers. If the source is a short text, you can simply leave out the page number. With longer sources, you can use an alternate locator such as a subheading or paragraph number if you need to specify where to find the quote:

Multiple citations at the same point

When you need multiple citations to appear at the same point in your text – for example, when you refer to several sources with one phrase – you can present them in the same set of brackets, separated by semicolons. List them in order of publication date:

Multiple sources with the same author and date

If you cite multiple sources by the same author which were published in the same year, it’s important to distinguish between them in your citations. To do this, insert an ‘a’ after the year in the first one you reference, a ‘b’ in the second, and so on:

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

A bibliography or reference list appears at the end of your text. It lists all your sources in alphabetical order by the author’s last name, giving complete information so that the reader can look them up if necessary.

The reference entry starts with the author’s last name followed by initial(s). Only the first word of the title is capitalised (as well as any proper nouns).

Sources with multiple authors in the reference list

As with in-text citations, up to three authors should be listed; when there are four or more, list only the first author followed by ‘ et al. ’:

| Number of authors | Reference example |

|---|---|

| 1 author | Davis, V. (2019) … |

| 2 authors | Davis, V. and Barrett, M. (2019) … |

| 3 authors | Davis, V., Barrett, M. and McLachlan, F. (2019) … |

| 4+ authors | Davis, V. (2019) … |

Reference list entries vary according to source type, since different information is relevant for different sources. Formats and examples for the most commonly used source types are given below.

- Entire book

- Book chapter

- Translated book

- Edition of a book

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) . City: Publisher. |

| Example | Smith, Z. (2017) . London: Penguin. |

| Notes |

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) ‘Chapter title’, in Editor name (ed(s).) . City: Publisher, page range. |

| Example | Greenblatt, S. (2010) ‘The traces of Shakespeare’s life’, in De Grazia, M. and Wells, S. (eds.) . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–14. |

| Notes |

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) . Translated from the [language] by Translator name. City: Publisher. |

| Example | Tokarczuk, O. (2019) . Translated from the Polish by A. Lloyd-Jones. London: Fitzcarraldo. |

| Notes |

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) . Edition. City: Publisher. |

| Example | Danielson, D. (ed.) (1999) . 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

| Notes |

Journal articles

- Print journal

- Online-only journal with DOI

- Online-only journal with no DOI

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) ‘Article title’, , Volume(Issue), pp. page range. |

| Example | Thagard, P. (1990) ‘Philosophy and machine learning’, , 20(2), pp. 261–276. |

| Notes |

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) ‘Article title’, , Volume(Issue), page range. DOI. |

| Example | Adamson, P. (2019) ‘American history at the foreign office: Exporting the silent epic Western’, , 31(2), pp. 32–59. doi: https://10.2979/filmhistory.31.2.02. |

| Notes | if available. |

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) ‘Article title’, , Volume(Issue), page range. Available at: URL (Accessed: Day Month Year). |

| Example | Theroux, A. (1990) ‘Henry James’s Boston’, , 20(2), pp. 158–165. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20153016 (Accessed: 13 February 2020). |

| Notes |

- General web page

- Online article or blog

- Social media post

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) . Available at: URL (Accessed: Day Month Year). |

| Example | Google (2019) . Available at: https://policies.google.com/terms?hl=en-US (Accessed: 27 January 2020). |

| Notes |

| Format | Author surname, initial. (Year) ‘Article title’, , Date. Available at: URL (Accessed: Day Month Year). |

| Example | Leafstedt, E. (2020) ‘Russia’s constitutional reform and Putin’s plans for a legacy of stability’, , 29 January. Available at: https://blog.politics.ox.ac.uk/russias-constitutional-reform-and-putins-plans-for-a-legacy-of-stability/ (Accessed: 13 February 2020). |

| Notes |

| Format | Author surname, initial. [username] (Year) or text [Website name] Date. Available at: URL (Accessed: Day Month Year). |

| Example | Dorsey, J. [@jack] (2018) We’re committing Twitter to help increase the collective health, openness, and civility of public conversation … [Twitter] 1 March. Available at: https://twitter.com/jack/status/969234275420655616 (Accessed: 13 February 2020). |

| Notes |

Sometimes you won’t have all the information you need for a reference. This section covers what to do when a source lacks a publication date or named author.

No publication date

When a source doesn’t have a clear publication date – for example, a constantly updated reference source like Wikipedia or an obscure historical document which can’t be accurately dated – you can replace it with the words ‘no date’:

| In-text citation | (Scribbr, no date) |

| Reference list entry | Scribbr (no date) . Available at: https://www.scribbr.co.uk/category/thesis-dissertation/ (Accessed: 14 February 2020). |

Note that when you do this with an online source, you should still include an access date, as in the example.

When a source lacks a clearly identified author, there’s often an appropriate corporate source – the organisation responsible for the source – whom you can credit as author instead, as in the Google and Wikipedia examples above.

When that’s not the case, you can just replace it with the title of the source in both the in-text citation and the reference list:

| In-text citation | (‘Divest’, no date) |

| Reference list entry | ‘Divest’ (no date) Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/divest (Accessed: 27 January 2020). |

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.

Vancouver referencing uses a numerical system. Sources are cited by a number in parentheses or superscript. Each number corresponds to a full reference at the end of the paper.

| Harvard style | Vancouver style | |

|---|---|---|

| In-text citation | Each referencing style has different rules (Pears and Shields, 2019). | Each referencing style has different rules (1). |

| Reference list | Pears, R. and Shields, G. (2019). . 11th edn. London: MacMillan. | 1. Pears R, Shields G. Cite them right: The essential referencing guide. 11th ed. London: MacMillan; 2019. |

A Harvard in-text citation should appear in brackets every time you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source.

The citation can appear immediately after the quotation or paraphrase, or at the end of the sentence. If you’re quoting, place the citation outside of the quotation marks but before any other punctuation like a comma or full stop.

In Harvard referencing, up to three author names are included in an in-text citation or reference list entry. When there are four or more authors, include only the first, followed by ‘ et al. ’

| In-text citation | Reference list | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 author | (Smith, 2014) | Smith, T. (2014) … |

| 2 authors | (Smith and Jones, 2014) | Smith, T. and Jones, F. (2014) … |

| 3 authors | (Smith, Jones and Davies, 2014) | Smith, T., Jones, F. and Davies, S. (2014) … |

| 4+ authors | (Smith , 2014) | Smith, T. (2014) … |

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a difference in meaning:

- A reference list only includes sources cited in the text – every entry corresponds to an in-text citation .

- A bibliography also includes other sources which were consulted during the research but not cited.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, September 15). A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 7 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/referencing/harvard-style/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, harvard in-text citation | a complete guide & examples, harvard style bibliography | format & examples, referencing books in harvard style | templates & examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

Referencing

Referencing is one of the most important aspects of any academic research and poor or lack of referencing will not only diminish your marks, but such practices may also be perceived as plagiarism by your university and disciplinary actions may follow that may even result in expulsion from the course.

Difference between References and Bibliography

It is very important to be able to distinguish between References and Bibliography. Under References you list resources that you referred to within the body of the work that also include quotations. For example,

It has been noted that “time and the management of time is an important issue, and the supply of time management products – books, articles, CDs, workshops, etc. – reflects the huge demand for these products” (Walsh, 2007, p.3).

Interchangeability of identical parts and a high level of straightforwardness of attaching these parts through the assembly line can be considered as revolutionary components of Fordism for the first part of the 20 th century (Nolan, 2008).

Under Bibliography, on the other hand, you need to list resources that you have read during the research process in order to widen your knowledge about the research area , but specific piece of information from these resources have not been used in your research in the direct manner. You do not need to refer to Bibliography within the body of the text.

There are various methods of referencing such as Harvard, APA and Vancouver referencing systems. You should check with your dissertation handbook for the exact type of referencing required and follow this requirement thoroughly.

John Dudovskiy

Citation Guide

- What is a Citation?

- Citation Generator

- Chicago/Turabian Style

- Paraphrasing and Quoting

- Examples of Plagiarism

What is a Bibliography?

What is an annotated bibliography, introduction to the annotated bibliography.

- Writing Center

- Writer's Reference Center

- Helpful Tutorials

- the authors' names

- the titles of the works

- the names and locations of the companies that published your copies of the sources

- the dates your copies were published

- the page numbers of your sources (if they are part of multi-source volumes)

Ok, so what's an Annotated Bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is the same as a bibliography with one important difference: in an annotated bibliography, the bibliographic information is followed by a brief description of the content, quality, and usefulness of the source. For more, see the section at the bottom of this page.

What are Footnotes?

Footnotes are notes placed at the bottom of a page. They cite references or comment on a designated part of the text above it. For example, say you want to add an interesting comment to a sentence you have written, but the comment is not directly related to the argument of your paragraph. In this case, you could add the symbol for a footnote. Then, at the bottom of the page you could reprint the symbol and insert your comment. Here is an example:

This is an illustration of a footnote. 1 The number “1” at the end of the previous sentence corresponds with the note below. See how it fits in the body of the text? 1 At the bottom of the page you can insert your comments about the sentence preceding the footnote.

When your reader comes across the footnote in the main text of your paper, he or she could look down at your comments right away, or else continue reading the paragraph and read your comments at the end. Because this makes it convenient for your reader, most citation styles require that you use either footnotes or endnotes in your paper. Some, however, allow you to make parenthetical references (author, date) in the body of your work.

Footnotes are not just for interesting comments, however. Sometimes they simply refer to relevant sources -- they let your reader know where certain material came from, or where they can look for other sources on the subject. To decide whether you should cite your sources in footnotes or in the body of your paper, you should ask your instructor or see our section on citation styles.

Where does the little footnote mark go?

Whenever possible, put the footnote at the end of a sentence, immediately following the period or whatever punctuation mark completes that sentence. Skip two spaces after the footnote before you begin the next sentence. If you must include the footnote in the middle of a sentence for the sake of clarity, or because the sentence has more than one footnote (try to avoid this!), try to put it at the end of the most relevant phrase, after a comma or other punctuation mark. Otherwise, put it right at the end of the most relevant word. If the footnote is not at the end of a sentence, skip only one space after it.

What's the difference between Footnotes and Endnotes?

The only real difference is placement -- footnotes appear at the bottom of the relevant page, while endnotes all appear at the end of your document. If you want your reader to read your notes right away, footnotes are more likely to get your reader's attention. Endnotes, on the other hand, are less intrusive and will not interrupt the flow of your paper.

If I cite sources in the Footnotes (or Endnotes), how's that different from a Bibliography?

Sometimes you may be asked to include these -- especially if you have used a parenthetical style of citation. A "works cited" page is a list of all the works from which you have borrowed material. Your reader may find this more convenient than footnotes or endnotes because he or she will not have to wade through all of the comments and other information in order to see the sources from which you drew your material. A "works consulted" page is a complement to a "works cited" page, listing all of the works you used, whether they were useful or not.

Isn't a "works consulted" page the same as a "bibliography," then?

Well, yes. The title is different because "works consulted" pages are meant to complement "works cited" pages, and bibliographies may list other relevant sources in addition to those mentioned in footnotes or endnotes. Choosing to title your bibliography "Works Consulted" or "Selected Bibliography" may help specify the relevance of the sources listed.

This information has been freely provided by plagiarism.org and can be reproduced without the need to obtain any further permission as long as the URL of the original article/information is cited.

How Do I Cite Sources? (n.d.) Retrieved October 19, 2009, from http://www.plagiarism.org/plag_article_how_do_i_cite_sources.html

The Importance of an Annotated Bibliography

An Annotated Bibliography is a collection of annotated citations. These annotations contain your executive notes on a source. Use the annotated bibliography to help remind you of later of the important parts of an article or book. Putting the effort into making good notes will pay dividends when it comes to writing a paper!

Good Summary

Being an executive summary, the annotated citation should be fairly brief, usually no more than one page, double spaced.

- Focus on summarizing the source in your own words.

- Avoid direct quotations from the source, at least those longer than a few words. However, if you do quote, remember to use quotation marks. You don't want to forget later on what is your own summary and what is a direct quotation!

- If an author uses a particular term or phrase that is important to the article, use that phrase within quotation marks. Remember that whenever you quote, you must explain the meaning and context of the quoted word or text.

Common Elements of an Annotated Citation

- Summary of an Article or Book's thesis or most important points (Usually two to four sentences)

- Summary of a source's methodological approach. That is, what is the source? How does it go about proving its point(s)? Is it mostly opinion based? If it is a scholarly source, describe the research method (study, etc.) that the author used. (Usually two to five sentences)

- Your own notes and observations on the source beyond the summary. Include your initial analysis here. For example, how will you use this source? Perhaps you would write something like, "I will use this source to support my point about . . . "

- Formatting Annotated Bibliographies This guide from Purdue OWL provides examples of an annotated citation in MLA and APA formats.

- << Previous: Examples of Plagiarism

- Next: ACM Style >>

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 2:14 PM

- URL: https://libguides.limestone.edu/citation

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Citing sources

Citation Styles Guide | Examples for All Major Styles

Published on June 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on November 7, 2022.

A citation style is a set of guidelines on how to cite sources in your academic writing . You always need a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize a source to avoid plagiarism . How you present these citations depends on the style you follow. Scribbr’s citation generator can help!

Different styles are set by different universities, academic associations, and publishers, often published in an official handbook with in-depth instructions and examples.

There are many different citation styles, but they typically use one of three basic approaches: parenthetical citations , numerical citations, or note citations.

Parenthetical citations

- Chicago (Turabian) author-date

CSE name-year

Numerical citations

CSE citation-name or citation-sequence

Note citations

- Chicago (Turabian) notes and bibliography

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Types of citation: parenthetical, note, numerical, which citation style should i use, parenthetical citation styles, numerical citation styles, note citation styles, frequently asked questions about citation styles.

The clearest identifying characteristic of any citation style is how the citations in the text are presented. There are three main approaches:

- Parenthetical citations: You include identifying details of the source in parentheses in the text—usually the author’s last name and the publication date, plus a page number if relevant ( author-date ). Sometimes the publication date is omitted ( author-page ).

- Numerical citations: You include a number in brackets or in superscript, which corresponds to an entry in your numbered reference list.

- Note citations: You include a full citation in a footnote or endnote, which is indicated in the text with a superscript number or symbol.

Citation styles also differ in terms of how you format the reference list or bibliography entries themselves (e.g., capitalization, order of information, use of italics). And many style guides also provide guidance on more general issues like text formatting, punctuation, and numbers.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

In most cases, your university, department, or instructor will tell you which citation style you need to follow in your writing. If you’re not sure, it’s best to consult your institution’s guidelines or ask someone. If you’re submitting to a journal, they will usually require a specific style.

Sometimes, the choice of citation style may be left up to you. In those cases, you can base your decision on which citation styles are commonly used in your field. Try reading other articles from your discipline to see how they cite their sources, or consult the table below.

| Discipline | Typical citation style(s) |

|---|---|

| Economics | |

| Engineering & IT | |

| Humanities | ; ; |

| Law | ; |

| Medicine | ; ; |

| Political science | |

| Psychology | |

| Sciences | ; ; ; ; |

| Social sciences | ; ; ; |

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) recommends citing your sources using Chicago author-date style . AAA style doesn’t have its own separate rules. This style is used in the field of anthropology.

| AAA reference entry | Clarke, Kamari M. 2013. “Notes on Cultural Citizenship in the Black Atlantic World.” 28, no. 3 (August): 464–474. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43898483. |

| AAA in-text citation | (Clarke 2013) |

APA Style is defined by the 7th edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . It was designed for use in psychology, but today it’s widely used across various disciplines, especially in the social sciences.

| Wagemann, J. & Weger, U. (2021). Perceiving the other self: An experimental first-person account of nonverbal social interaction. , (4), 441–461. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.134.4.0441 | |

| (Wagemann & Weger, 2021) |

Generate accurate APA citations with Scribbr

The citation style of the American Political Science Association (APSA) is used mainly in the field of political science.

| APSA reference entry | Ward, Lee. 2020. “Equity and Political Economy in Thomas Hobbes.” , 64 (4): 823–35. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12507. |

| APSA in-text citation | (Ward 2020) |

The citation style of the American Sociological Association (ASA) is used primarily in the discipline of sociology.

| ASA reference entry | Kootstra, Anouk. 2016. “Deserving and Undeserving Welfare Claimants in Britain and the Netherlands: Examining the Role of Ethnicity and Migration Status Using a Vignette Experiment.” 32(3): 325–338. doi:10.1093/esr/jcw010. |

| ASA in-text citation | (Kootstra 2016) |

Chicago author-date

Chicago author-date style is one of the two citation styles presented in the Chicago Manual of Style (17th edition). It’s used mainly in the sciences and social sciences.

| Encarnação, João, and Gonçalo Calado. 2018. “Effects of Recreational Diving on Early Colonization Stages of an Artificial Reef in North-East Atlantic.” 22, no. 6 (December): 1209–1216. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45380397. | |

| (Encarnação and Calado 2018) |

The citation style of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) is used in various scientific disciplines. It includes multiple options for citing your sources, including the name-year system.

| CSE name-year reference entry | Graham JR. 2019. The structure and stratigraphical relations of the Lough Nafooey Group, South Mayo. Irish Journal of Earth Sciences. 37: 1–18. |

| CSE name-year citation | (Graham 2019) |

Harvard style is often used in the field of economics. It is also very widely used across disciplines in UK universities. There are various versions of Harvard style defined by different universities—it’s not a style with one definitive style guide.

| Hoffmann, M. (2016) ‘How is information valued? Evidence from framed field experiments’, , 126(595), pp. 1884–1911. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12401. | |

| (Hoffmann, 2016) |

Check out Scribbr’s Harvard Reference Generator

MLA style is the official style of the Modern Language Association, defined in the MLA Handbook (9th edition). It’s widely used across various humanities disciplines. Unlike most parenthetical citation styles, it’s author-page rather than author-date.

| Davidson, Clare. “Reading in Bed with .” , vol. 55, no. 2, Apr. 2020, pp. 147–170. https://doi.org/10.5325/chaucerrev.55.2.0147. | |

| (Davidson 155) |

Generate accurate MLA citations with Scribbr

The American Chemical Society (ACS) provides guidelines for a citation style using numbers in superscript or italics in the text, corresponding to entries in a numbered reference list at the end. It is used in chemistry.

| ACS reference entry | 1. Hutchinson, G.; Alamillo-Ferrer, C.; Fernández-Pascual, M.; Burés, J. Organocatalytic Enantioselective α-Bromination of Aldehydes with -Bromosuccinimide. , 87, 7968–7974. |

The American Medical Association ( AMA ) provides guidelines for a numerical citation style using superscript numbers in the text, which correspond to entries in a numbered reference list. It is used in the field of medicine.

| 1. Jabro JD. Predicting saturated hydraulic conductivity from percolation test results in layered silt loam soils. . 2009;72(5):22–27. |

CSE style includes multiple options for citing your sources, including the citation-name and citation-sequence systems. Your references are listed alphabetically in the citation-name system; in the citation-sequence system, they appear in the order in which you cited them.

| CSE citation-sequence or citation-name reference entry | 1. Nell CS, Mooney KA. Plant structural complexity mediates trade-off in direct and indirect plant defense by birds. Ecology. 2019;100(10):1–7. |

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers ( IEEE ) provides guidelines for citing your sources with IEEE in-text citations that consist of numbers enclosed in brackets, corresponding to entries in a numbered reference list. This style is used in various engineering and IT disciplines.

| IEEE reference entry | 1. J. Ive, A. Max, and F. Yvon, “Reassessing the proper place of man and machine in translation: A pre-translation scenario,” , vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 279–308, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.1007/s10590-018-9223-9. |

The National Library of Medicine (NLM) citation style is defined in Citing Medicine: The NLM Style Guide for Authors, Editors, and Publishers (2nd edition).

| NLM reference entry | 1. Hage J, Valadez JJ. Institutionalizing and sustaining social change in health systems: the case of Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2017 Nov;32(9):1248–55. doi:10.1093/heapol/czx066. |

Vancouver style is also used in various medical disciplines. As with Harvard style, a lot of institutions and publications have their own versions of Vancouver—it doesn’t have one fixed style guide.

| Vancouver reference entry | 1. Bute M. A backstage sociologist: Autoethnography and a populist vision. Am Soc. 2016 Mar 23; 47(4):499–515. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12108-016-9307-z doi:10.1007/s12108-016-9307-z |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation is the main style guide for legal citations in the US. It’s widely used in law, and also when legal materials need to be cited in other disciplines.

| Bluebook footnote citation | David E. Pozen, , 165, U. P🇦. L. R🇪🇻. 1097, 1115 (2017). |

Chicago notes and bibliography

Chicago notes and bibliography is one of the two citation styles presented in the Chicago Manual of Style (17th edition). It’s used mainly in the humanities.

| Best, Jeremy. “Godly, International, and Independent: German Protestant Missionary Loyalties before World War I.” 47, no. 3 (September 2014): 585–611. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008938914001654. | |

| 1. Jeremy Best, “Godly, International, and Independent: German Protestant Missionary Loyalties before World War I,” 47, no. 3 (September 2014): 599. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008938914001654. |

The Oxford University Standard for the Citation of Legal Authorities ( OSCOLA ) is the main legal citation style in the UK (similar to Bluebook for the US).

| OSCOLA footnote citation | 1. Chris Thornhill, ‘The Mutation of International Law in Contemporary Constitutions: Thinking Sociologically about Political Constitutionalism’ [2016] MLR 207. |

There are many different citation styles used across different academic disciplines, but they fall into three basic approaches to citation:

- Parenthetical citations : Including identifying details of the source in parentheses —usually the author’s last name and the publication date, plus a page number if available ( author-date ). The publication date is occasionally omitted ( author-page ).

- Numerical citations: Including a number in brackets or superscript, corresponding to an entry in your numbered reference list.

- Note citations: Including a full citation in a footnote or endnote , which is indicated in the text with a superscript number or symbol.

Check if your university or course guidelines specify which citation style to use. If the choice is left up to you, consider which style is most commonly used in your field.

- APA Style is the most popular citation style, widely used in the social and behavioral sciences.

- MLA style is the second most popular, used mainly in the humanities.

- Chicago notes and bibliography style is also popular in the humanities, especially history.

- Chicago author-date style tends to be used in the sciences.

Other more specialized styles exist for certain fields, such as Bluebook and OSCOLA for law.

The most important thing is to choose one style and use it consistently throughout your text.

A scientific citation style is a system of source citation that is used in scientific disciplines. Some commonly used scientific citation styles are:

- Chicago author-date , CSE , and Harvard , used across various sciences

- ACS , used in chemistry

- AMA , NLM , and Vancouver , used in medicine and related disciplines

- AAA , APA , and ASA , commonly used in the social sciences

APA format is widely used by professionals, researchers, and students in the social and behavioral sciences, including fields like education, psychology, and business.

Be sure to check the guidelines of your university or the journal you want to be published in to double-check which style you should be using.

MLA Style is the second most used citation style (after APA ). It is mainly used by students and researchers in humanities fields such as literature, languages, and philosophy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, November 07). Citation Styles Guide | Examples for All Major Styles. Scribbr. Retrieved June 7, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/citing-sources/citation-styles/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, apa vs. mla | the key differences in format & citation, the basics of in-text citation | apa & mla examples, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Postgrad Med

- v.69(1); Jan-Mar 2023

The art of referencing: Well begun is half done!

Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Sultanate of Oman

Department of Pediatrics, Seth G.S. Medical College and K.E.M. Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Introduction

The value of scientific research lies in its wide visibility and access/availability to others; this is generally achieved by a scientific publication as an original (research) paper. The scientific inquiry typically advances based on previously laid ideas/research, making it essential to acknowledge the contribution of the previous authors. The references list is a catalog of literature sources chosen by the researcher to represent the most relevant documents pertaining to his/her study.[ 1 ] The British Standards Institution defines reference as “a set of data describing a document, sufficiently precise and detailed to identify it and enable it to be located.” [ 2 ] References lay the foundation of the paper, providing context for the hypothesis, methodology, interpretation, and justification of the study.[ 3 ] Using other's ideas/thoughts without due credit amounts to plagiarism, compromising the academic integrity of research. A well-referenced paper is thus accurate and complete, adds value and credibility to both the researcher and the source author, and enhances the scientific prestige of the chosen journal.[ 3 ] A bibliography also lists the sources used during research. However, while references only include those sources (journals, books, web information, etc.) which are actually cited in the publication, bibliography comprises all accessed sources (works consulted), irrespective of whether they are cited in the study publication or not.[ 4 ] Thus, referencing in academic writing is an important research tool to display as well as integrate knowledge on a particular subject or topic.[ 5 ]

Importance of Proper Referencing

Scientific research is usually developed on previously established ideas/scientific knowledge. A meticulous literature review at the beginning of the study enables the researcher to identify the work done in the field, identify the gaps in knowledge, and recognize the need for further research.[ 6 ] The most relevant sources from this literature search (essentially) form the list of references. Use of proper referencing is thus beneficial in many ways, such as the following:

- a) It helps the readers to identify and locate the sources used in the research and provides evidence to verify the need/rationale of the study, methodology, inferences, and implications of the study.[ 3 ]

- b) It provides an overview of the techniques/tools used, supports/convinces the reader about the appropriateness of the methodology, and offers a proper perspective in which the research findings need to be interpreted.[ 3 , 7 ]

- c) It is a proof of the author's in-depth reading and knowledge on the subject pertaining to his/her research. References not only highlight similarities in research, but also differentiate the author's ideas from his sources, indirectly acknowledging the author's own contribution to that topic.[ 4 ]

- d) References chosen by a researcher not only credit the individual author/s whose work is cited, but also demonstrate his/her appreciation toward cited authors, at times leading readers toward hitherto lesser-known/unknown author's research.[ 4 , 8 ] By providing acknowledgment to the cited idea/thought, the author also avoids being accused of plagiarism and adds credibility to his/her own work.[ 4 ]

- e) Referenced works steer the readers toward literature pertaining to a particular topic, thus advancing the readers’ interest.[ 4 ] It also allows to trace the origins of ideas and integrates newer ideas (from current research) with previous ones, thus building a web of learning about the topic of interest.[ 9 ]

- f) The reference list provides a list of experts in a specific field, thus helping editors to identify appropriate reviewers.[ 3 ]

- g) It provides peer reviewers with related sources of information to evaluate the manuscript with respect to the cited work.[ 6 ]

Organizing the References