We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

34: Tuberculosis

David Cluck

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Patient presentation.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Chief Complaint

“I have a cough that won’t go away.”

History of Present Illness

A 63-year-old male presents to the emergency department with complaints of cough/shortness of breath which he attributes to a “nagging cold.” He states he fears this may be something worse after experiencing hemoptysis for the past 3 days. He also admits to waking up in the middle of the night “drenched in sweat” for the past few weeks. When asked, the patient denies ever having a positive PPD and was last screened “several years ago.” His chart indicates he was in the emergency department last week with similar symptoms and was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia and discharged with azithromycin.

Past Medical History

Hypertension, dyslipidemia, COPD, atrial fibrillation, generalized anxiety disorder

Surgical History

Appendectomy at age 18

Family History

Father passed away from a myocardial infarction 4 years ago; mother had type 2 DM and passed away from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

Social History

Retired geologist recently moved from India to live with his son who is currently in medical school in upstate New York. Smoked ½ ppd × 40 years and drinks 6 to 8 beers per day, recently admits to drinking ½ pint of vodka “every few days” since the passing of his wife 6 months ago.

Sulfa (hives); penicillin (nausea/vomiting); shellfish (itching)

Home Medications

Albuterol metered-dose-inhaler 2 puffs q4h PRN shortness of breath

Aspirin 81 mg PO daily

Atorvastatin 40 mg PO daily

Budesonide/formoterol 160 mcg/4.5 mcg 2 inhalations BID

Clonazepam 0.5 mg PO three times daily PRN anxiety

Lisinopril 20 mg PO daily

Metoprolol succinate 100 mg PO daily

Tiotropium 2 inhalations once daily

Venlafaxine 150 mg PO daily

Warfarin 7.5 mg PO daily

Physical Examination

Vital signs.

Temp 100.8°F, P 96, RR 24 breaths per minute, BP 150/84 mm Hg, pO 2 92%, Ht 5′10″, Wt 56.4 kg

Slightly disheveled male in mild-to-moderate distress

Normocephalic, atraumatic, PERRLA, EOMI, pale/dry mucous membranes and conjunctiva, poor dentition

Bronchial breath sounds in RUL

Cardiovascular

NSR, no m/r/g

Soft, non-distended, non-tender, (+) bowel sounds

Genitourinary

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Emerg Infect Dis

- v.8(11); 2002 Nov

Two Cases of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis subsp. canetti

Jean miltgen.

* Hôpital d’instruction des armées Laveran, Marseille, France

Marc Morillon

Jean-louis koeck.

† Hôpital d’instruction des armées Val de Grâce, Paris, France

Anne Varnerot

‡ Institut Pasteur, Paris, France

Jean-François Briant

Gilbert nguyen, denis verrot, daniel bonnet, véronique vincent.

We identified an unusual strain of mycobacteria from two patients with pulmonary tuberculosis by its smooth, glossy morphotype and, primarily, its genotypic characteristics. Spoligotyping and restriction fragment length polymorphism typing were carried out with the insertion sequence IS6110 patterns. All known cases of tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium canetti have been contracted in the Horn of Africa.

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex includes the following mycobacteria, which are characterized by a slow growing rate: M. tuberculosis, M. africanum, M. bovis, and M. microti ( 1 ). In recently published reports of two cases of lymphatic node tuberculosis (TB), the strains were recognized as belonging to a new taxon of M. tuberculosis ( 2 , 3 ). These isolates were characterized by a highly particular growing pattern, and the colonies appeared smooth and glossy. A complete genetic study of these strains led to their integration into the M. tuberculosis complex. This strain, identified as M. tuberculosis subsp. canetti or, more simply, M. canetti, was first isolated in 1969 by Georges Canetti from a French farmer. The strain was preserved at the Pasteur Institute where its antigenic pattern was studied extensively. We report two cases of pulmonary TB caused by this strain. The two patients had also lived in East Africa.

In September 1998, a 36-year-old male soldier in the French Foreign Legion with hemoptysis was sent back to France from Djibouti. He expectorated bloody sputum after running and on a few other occasions. His medical history was not unusual. When the patient was hospitalized, 2 weeks after the initial symptoms, he began to experience progressive fatigue. He did not experience fever, weight loss, night sweats, anorexia, cough, dyspnea, or chest pain, and did not produce sputum.

Results of the clinical examination were normal. The Mantoux test, performed with 10 IU of purified tuberculin (Aventis-Pasteur-MSD, Lyon, France), yielded a maximum transverse diameter of induration of 15 mm. Laboratory values were normal ( Table ). The chest X-ray showed a triangular consolidation of the left upper lobe with blurred limits and small cavitary lesions. No other contiguous mediastinohilar anomalies were visible. A computed tomographic scan confirmed the cavitary syndrome: three excavated nodular images showed radiating spicules within a micronodular infiltrate. Bronchoscopy showed a moderate inflammation of airway mucosa, especially in the left upper lobe. Biopsy specimens exhibited nonspecific inflammation.

A bronchial washing smear from the left upper lobe was positive for acid-fast bacilli. Serologic tests for HIV-1 and HIV-2 were negative. No evidence of disease was found elsewhere; the patient did not experience bone pain. Results of neurologic and ophthalmologic examinations were normal; no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly were found and the genitalia were normal. Auscultation revealed no pericardial fremitus; no ascitic fluid was detected. The urinary sediment contained <1,000 red blood cells/L and <5,000 leukocytes/L. Antituberculosis chemotherapy was begun with four drugs: rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Cultures revealed a strain identified as M. tuberculosis subsp. canetti that was susceptible to all primary antituberculous drugs. Therefore, rifampicin and isoniazid were continued for 3 more months for a total treatment period of 6 months. The patient’s response to treatment was favorable, and he remained asymptomatic.

A 55-year-old male soldier in the French Foreign Legion, who returned from Djibouti, was hospitalized in September 1999 after his chest x-ray showed abnormal findings. He was a nurse and had been occasionally in charge at the Djibouti Hospital for 2 years. His medical history was unremarkable. Eight months before he returned to France, he experienced asthenia, anorexia, and a weight loss of 3 kg. The symptoms resolved spontaneously after 2 months, and he had been asymptomatic since then. He had no history of cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, dyspnea, fever, or night sweats.

Results of a clinical examination and of laboratory studies were normal ( Table ), except for hypereosinophilia. Serologic tests for schistosomiasis, hydatidosis, distomiasis, amebiasis, toxocariasis, and trichinosis were negative, and parasites were not found in stool samples. Thoracic radiographs performed when he came back from Djibouti showed parenchymal consolidation of the right upper lobe with small cavities. Sputum was not produced. A gastric aspirate smear was negative for acid-fast bacilli, and a bronchial aspiration smear was positive for acid-fast bacilli. HIV serology was negative, and no other site of the infection was found. Drug therapy was initiated with rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 2 months. Cultures of bronchial aspirates were positive within 14 days; later, cultures of two gastric aspirates were positive for acid-fast bacilli. An M. tuberculosis subsp. canetti isolate was identified, which was susceptible to all primary antituberculous drugs. The treatment was then extended for 4 months with rifampicin and isoniazid. The patient's response to treatment was favorable.

The following methods were used to identify the etiologic agent. First, the samples were decontaminated with N-acetyl-L-cysteine/NaOH. Acid-fast bacilli were detected by auramine staining, the positive smears also were stained with Ziehl-Nielsen stain. The samples were then seeded onto Löwenstein-Jensen and Coletsos slants and also into a liquid system, the BBL Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT, BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD).

The mycobacteria were identified by using a specific DNA probe (Gen-Probe, Gen-Probe Incorporated, San Diego, CA) and by performing the usual biochemical tests (nitrate reduction, 68°C catalase resistance, niacin production).

The Pasteur Institute of Paris used two methods for typing: restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis and spoligotyping. In RFLP analysis, after digestion of the M. tuberculosis strain's genomic DNA with PvuII restriction enzyme and agarose gel migration, the DNA was transferred on a membrane, according to the Southern method, and then hybridized with an insertion sequence IS6110 probe ( 4 ). In the spoligotyping method, after DNA direct repeat amplification, the labeled polymerase chain reaction product was used as a probe to hybridize with 43 synthetic spacer oligonucleotides (DNA sequences derived from the direct repeat [DR] region of M. tuberculosis, H37Rv and M. bovis BCG P3), which were attached to a carrier membrane ( 5 ). The sensitivity to antituberculous drugs was determined by the indirect proportion method.

MGIT results were positive for the two cultures in 9 and 12 days, respectively. On Löwenstein-Jensen slants, the cultures were positive in 12 and 14 days, respectively. The white, smooth, and glossy colonies were characteristic of M. tuberculosis subsp. canetti ( Figure 1 ). The two strains had the same phenotypic and genotypic pattern; 68°C catalase was negative, and they reduced nitrate, as do other M. tuberculosis species, but they did not produce niacin. The DNA probe, Gen-Probe, confirmed that these strains belonged to the M. tuberculosis complex.

Colony morphology on Löwenstein-Jensen slants, showing M. canetti and M. tuberculosis strains. (A) Colonies of M. tuberculosis are rough, thick, wrinkled, have an irregular margin, and are faintly buff-colored. (B) M. canetti exhibits smooth, white and glossy colonies.

These strains contained two copies of IS6110. Spoligotyping showed that they shared only 2 of the 43 oligonucleotides reproducing the spacer DNA sequences of M. tuberculosis, H37Rv and M. bovis BCG P3. This profile is characteristic of M. tuberculosis subsp. canetti ( Figure 2 ).

(A) IS6110 hybridization patterns of PvuII-digested genomic DNA. Lane 1, Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mt 14323 (reference strain). Lane 2, M. canetti strain NZM 217/94. Lanes 3 and 4, the strains isolated from French legionnaires with pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). (B) Spoligotyping patterns. Lane 1, M. tuberculosis H37Rv (reference strain). Lane 2, M. canetti strain NZM 217/94. Lanes 3 and 4, the strains isolated from French legionnaires with pulmonary TB.

In 1997, van Soolingen reported a case of lymph node TB in a 2-year-old Somali child on the child’s arrival in the Netherlands in 1993 ( 2 ). In 1998, Pfyffer described abdominal lymphatic TB in a 56-year-old Swiss man (who lived in Kenya) with stage C2 HIV infection ( 3 ). These strains of M. canetti (So93 from the Somali child and NZM 217/94 from the Swiss man) have been studied extensively. In culture they grow faster than other strains in the M. tuberculosis complex. The So93 strain expands by one rough colony for every 500 smooth colonies. They appear smooth, white, and glossy because of the high amount of lipooligosaccharides in the membrane ( 6 ); the So93 rough colonies lack this amount ( 2 ).

Two copies of the IS6110 insertion sequence were found in the NZM 217/94 and So93 genome. This fingerprint matched none of the 5,000 other strains preserved in the laboratory of van Soolingen (Bilthoven, the Netherlands) ( 2 ). The strains we observed also showed two copies of IS6110.

So93, NZM 217/94, and our two strains share only 2 of 43 identical repeated sequences that have been observed by spoligotyping. Study of the IS6110 RFLP patterns and of the spacer DNA sequences of the DR locus confirmed that M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, M. microti, and M. canetti represent a closely related group of mycobacteria that are clearly distinct from other mycobacterial species. In the M. tuberculosis complex, M. canetti appears to be the most divergent strain ( 2 ).

We believe that this is the first published report of pulmonary disease caused by M. canetti. Our two cases confirm that M. canetti is able to involve lungs, like any other other member of the M. tuberculosis complex and is able to affect immunocompetent subjects. The clinical features of these two pulmonary cases of TB caused by M. canetti are not specific.

TB caused by M. canetti appears to be an emerging disease in the Horn of Africa. A history of a visit to the region should cause this strain to be considered promptly. As travel to this area becomes more frequent, and mycobacterial identification techniques improve, the number of diagnosed cases will likely increase.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michel Fabre for the photographs and Jan Eskandari for his translation of this article.

Dr. Miltgen is assistant head of the Pneumology Department at the Hôpital d’Instruction des Armées of Marseilles, where he specializes in tropical diseases.

Suggested citation for this article: Miltgen J, Morrillon M, Koeck J-L, Varnerot A, Briant J-F, Nguyen G. Two cases of pulmonary tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis subsp. canetti. Emerg Infect Dis [serial online] 2002 Nov [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol8no11/02-0017.htm

Case Report: Pulmonary tuberculosis and raised transaminases without pre-existing liver disease- Do we need to modify the antitubercular therapy?

Sanjeev Gautam Roles: Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation Keshav Raj Sigdel Roles: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing Sudeep Adhikari Roles: Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Buddha Basnyat Roles: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing Buddhi Paudyal Roles: Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing Jiwan Poudel Roles: Writing – Review & Editing Ujjwol Risal Roles: Writing – Review & Editing

This article is included in the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit (OUCRU) gateway.

tuberculosis, transaminitis, standard ATT, liver friendly regimen

Revised Amendments from Version 1

The changes have been made in the revised manuscript as suggested by the reviewers. The concerns of reviewers regarding limited workup of the patient for liver disease has been addressed in the manuscript. This is a single case report and further studies are required to make a firm recommendation for management of pulmonary tuberculosis with transaminitis without pre-existing liver disease. We have acknowledged the fact in the revised manuscript.

See the authors' detailed response to the review by Vivek Neelakantan See the authors' detailed response to the review by Neesha Rockwood See the authors' detailed response to the review by Prajowl Shrestha and Ashesh Dhungana

Tuberculosis is the biggest infectious disease killer in the world 1 , and is endemic in Nepal with the national prevalence at 416 cases per 100000 population 2 . Pulmonary tuberculosis is the most common form. In Nepal, tuberculosis prevalence is more in productive age group (25–64 years) and men. Poverty, malnutrition, overcrowding, immunocompromised state like HIV infection, alcohol, smoking, air pollution, diabetes and other comorbidities are important risk factors for acquiring the disease 3 . Though under-reported, involvement of liver with tuberculosis is encountered often in clinical practice in endemic areas like Nepal.Liver can be involved; a) diffusely as a part of disseminated miliary tuberculosis or as primary miliary tuberculosis of liver, or b) focal involvement as hepatic tuberculoma or abscess, as was classified by Reed in 1990 4 . The biochemical pattern of liver function abnormality in these forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis is cholestatic (predominantly raised alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase) rather than hepatocellular (predominantly raised transaminases) 5 , 6 . The hepatocellular pattern of liver injury is seen in cases with pre-existing liver disease including hepatotoxic drug use, which are unrelated to tuberculosis 7 , 8 .

As per national protocol of Nepal, any patient with tuberculosis receives combination antitubercular therapy (ATT) including four drugs; Isoniazid (H), Rifampicin (R), Pyrazinamide (Z) and Ethambutol (E) for initial 2 months popularly known as HRZE. This is followed by 4 months of two drugs; HR. Treatment is given under Directly Observed Treatment Short- Course (DOTS) to improve the patient compliance which could otherwise be compromised owing to lower socioeconomic status of patients, longer duration of treatment and side effects 9 . Patients with extrapulmonary hepatic tuberculosis are treated with full dose of standard ATT 5 , 6 . But three out of the four drugs (H, R and Z) are hepatotoxic 7 . So the patients having pre-existing liver disease usually require liver-friendly modified regimens to protect the liver but they may be suboptimal for eradicating underlying tuberculosis 8 . The protocol of Nepal does not warrant baseline investigations except chest X-ray and sputum smear microscopy to be done routinely before prescribing ATT in programmatic setting 9 . However in hospital setting like our case, baseline blood investigations including liver function tests are usually done before starting treatment even in absence of features suggesting liver injury and therapy modified accordingly.

Here we present a case of pulmonary tuberculosis with predominant transaminitis but there was no feature of pre-existing liver disease nor a history of hepatotoxic drug use. The liver injury was attributed to the pulmonary tuberculosis itself, and treated with standard first line ATT which led to resolution of liver function abnormalities.

Case presentation

A 33 year old Newar housewife from Kathmandu, Nepal, with no known comorbidity, presented to Patan Hospital Emergency Department in November, 2019 with a history of cough with occasional sputum production over the previous 20 days and low grade fever for 10 days. There was no history of chest pain, difficulty breathing, headache, vomiting, altered mentation, abdominal pain, yellowish discoloration of eyes, burning urine, hair loss, photosensitivity, joint pain, or rash but she had decreased appetite and weight loss. There was no past history of tuberculosis or jaundice. She did not consume alcohol or any drugs including acetaminophen, aflatoxin or herbal products. Her father-in-law had been diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis five years earlier, but there was no family history of liver disease.

Initial examination showed temperature of 101 o F with pulse of 110 beats/minute and respiratory rate of 26 breaths/minute. There was diffuse fine crepitation on the left side on auscultation of the chest. There was no lymphadenopathy, icterus, peripheral edema or wheezes. Neck veins were not distended. Liver and spleen were not palpable, and abdomen examination was normal.

Laboratory parameters with normal ranges in parenthesis are as follow:

Complete blood count before transfusion: white cell count 7.8 (4–10) × 10 9 /L; neutrophils 80%; lymphocytes 16%; monocytes 4%; red blood cells 3.6 (4.2–5.4) × 10 12 /L; haemoglobin 10.6 (12–15) g/dL; platelets 410 (150–400) × 10 9 /L.

Biochemistry: random blood sugar 126 (65–110) mg/dL; urea 39 (17–45) mg/dL; creatinine 1.1 (0.8–1.3) mg/dL; sodium 138 (135–145) mmol/L and potassium 4 (3.5–5) mmol/L.

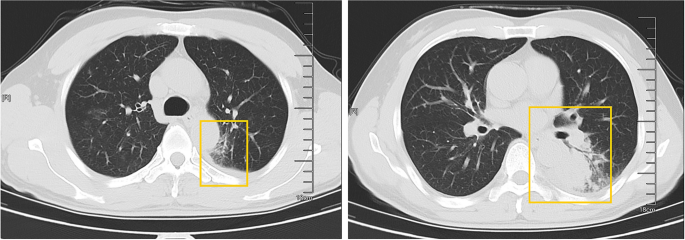

Chest X-ray ( Figure 1 ) showed thick walled cavitating lesions in the left upper lobe and patchy infiltrates in left middle and lower zones. There were hyperinflated lung fields with blunting of left costophrenic angle. Sputum smear examination showed 3+ acid fast bacilli. Sputum Gene Xpert was positive for Rifampicin sensitive tubercle bacilli. A diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis was made, and planned for starting ATT.

Figure 1. Chest X-ray showing thick walled cavitating lesions in the left upper lobe and patchy infiltrates in left middle and lower zones.

Liver function test was performed as baseline workup before starting treatment which showed the following results (with normal ranges in parenthesis): bilirubin total 1.1 (0.1–1.2) mg/dL and direct 0.5 (0–0.4) mg/dL; alanine transaminase 308 (5–30) units/L; aspartate transaminase 605 (5–30) units/L; alkaline phosphatase 149 (50–100) IU/L; gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase66 (9–48) units/L. The raised transaminases led us to perform further workup for liver disease. There was no clinical evidence of chronic liver disease or portal hypertension. Liver synthetic functions were as following;albumin 3.5 (3.5–5) g/dL; total protein 6.5 (6–8.3) g/dL; prothrombin time 14 (11–13.5) s. Serologies for HIV, HBsAg, Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Hepatitis A virus (HAV) and Hepatitis E virus (HEV) were nonreactive. Testing for other hepatotropic viruses was not done because of unavailability of the tests. Neurological examinations and the slit lamp examination of eye were normal. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed a normal sized liver with smooth outline and echotexture. However fibroscan, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, abdominal CT scan and liver biopsy were not done due to financial constraints of the patient.

She was admitted to the respiratory isolation unit. At first there was some hesitation in starting the full treatment for her pulmonary tuberculosis because of her liver function tests. But taking into consideration her presentation and laboratory findings, we opted for the full treatment rather than a modified TB regimen. We started standard four drugs ATT based on her weight as per national TB guidelines which included three tablets of HRZE given once daily with each tablet containing 75 mg isoniazid (H), 150 mg rifampicin (R), 400 mg pyrazinamide (Z) and 275 mg ethambutol (E). This led to improvement in her clinical status. She was closely observed for possible worsening of her liver disease due to the hepatotoxic antitubercular drugs. Providentially, at 1 week after starting treatment, she was afebrile and continuing to improve and her liver function test showed a total bilirubin of 0.7 mg/dl, aspartate transaminase of 40 IU/L and alanine transaminase of 62 IU/L.

She was discharged with advice to follow up in 1 month. At 1 month follow up she had no symptoms and therefore no further tests were done. At 2 months, she was still asymptomatic and her sputum smear was negative for acid fast bacilli. Her liver function test showed a total bilirubin of 0.6 mg/dl, aspartate transaminase of 30 IU/L and alanine transaminase of 35 IU/L. She was switched to3 tablets of HR to be taken for 4 months.

Our patient with pulmonary tuberculosis had predominantly raised transaminases (hepatocellular pattern)during the initial presentation, with only modest elevation in alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyltranspeptidase. The workup for liver disease could not be performed completely because of resource limitation. Looking for clinical evidences by history and examination, and performing liver function tests, abdominal ultrasound and serology for common hepatotropic viruses are usually considered sufficient in our limited setup. We perform further tests only if the initial workup hints towards another etiology. There were no clinical features of chronic liver disease or portal hypertension. She had no risk factors for liver disease such as family history, alcohol, drugs, toxins, features suggesting autoimmune or metabolic liver diseases. Her viral hepatitis serologies were negative. Ultrasound also showed normal liver architecture and size.Though incomplete, the initial workup led us to believe that she had no pre-existing liver injury.

Patients with extrapulmonary hepatic tuberculosis as classified by Reed (diffuse or focal)usually present withnonspecific symptoms like abdominal pain, jaundice, fever, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss and hepatomegaly. They havecholestatic pattern of liver function abnormality with normal transaminases, increased protein- albumin gap owing to raised serum globulin. Hepatic imaging with ultrasound or CT scan reveal abnormalities in 76 and 88% cases respectively. Liver biopsy and demonstration of caseating granuloma and mycobacterial culture remain gold standard for diagnosing hepatic tuberculosis 4 – 6 . Following points in our patient precluded making the diagnosis of hepatic tuberculosis; a) absence of abdominal symptoms and hepatomegaly; b) predominantly raised transaminases (hepatocellular pattern) and normal protein- albumin gap; and c) normal ultrasound finding (though CT and biopsy were not done).

There is another classification schema, given by Levine in 1990 which has incorporated additional entity under hepatic tuberculosis which is ‘pulmonary tuberculosis withliver involvement’ 10 . In the absence of obvious pre-existing liver disease or drug and the presence of active cavitary tuberculosis in lungs, we attributed the transaminitisin our patient to the pulmonary tuberculosis itself. In our anecdotal experience, we have found many such patients though we do not have any formal data to back this up. They are often managed with modified liver-friendly antitubercular regimens for fear of increasing the hepatotoxicity and causing acute liver failure with the use of standard regimen. Few case reports are available in literature reporting the use of the modified regimens 11 , 12 . We believe such cases are underreported, and firm guidelines have not been established to guide clinicians in these cases. Given this, many clinicians in low-middle income countries, including Nepal, who have been treating tuberculosis patients tend to be skeptical in using full doses of first line ATT in such patients and tend to use a modified regimen. However, this practice may potentially lead to under-treatment and therefore increase fatality 13 . The use of modified regimen may also increase the risk of developing drug-resistant tuberculosis because of exclusion of more potent drugs 14 . Though there was some hesitation at first in our case, we soon started treatment with the standard ATT in our patient with close monitoring. This we believe led to the resolution of liver injury, evidenced by the normalization of transaminases.

However, acknowledging that the patient may develop drug induced liver injury (DILI) with the hepatotoxic antitubercular drugs, we should monitorsuch patients closely in an inpatient basis to look forclinical deterioration or any feature suggesting liver failureand liver function test repeated regularly. Though there is no firm recommendation for when to repeat the tests, patient should not be discharged till there is significant improvement in the transaminases level. The close monitoring is important in those with higher risks for developing DILI associated with ATT such as elderly, females, alcohol consumers, the malnourished and those with genetic susceptibility like slow acetylators 7 . Such monitoring is even more important in our setup because there are possibilities of missing occult hepatic diseases owing tolimited workup.Our patient had improving transaminases evidenced till 2 months follow up.

Though limited by incomplete investigations, we concluded pulmonary tuberculosis as the cause for transaminitis in our patient, and the normalization of transaminases after starting the standard dose of ATT further supports this conclusion. We believe pulmonary TB presenting with transaminitis is a common problem and that treatment may often be compromised because of decreased dosing of ATT.We further aim to perform case series study to explore the magnitude of problem and reach specific conclusions.

When treating a tuberculosis patient with transaminitis, it is important to look for any possibility of pre-existing liver disease or drug use. If none is found, then the use of standard ATT from the beginning with close inpatient monitoring of the patient may be essential for optimal management of tuberculosis, and this may help resolve any liver injury caused by the tuberculosis. This is a single case report, so further case series or cohort studies would be helpful to reach some conclusion and provide concrete recommendations.

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the patient.

Data availability

Underlying data.

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

- 1. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis . .

- 2. https://nepalntp.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NEPAL-NATIONAL-TB-PREVALENCE-SURVEY-BRIEF-March-24-2020.pdf . .

- 3. https://nepalntp.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NTP-Annual-Report-2075-76-2018-19.pdf .

- 4. Reed DH, Nash AF, Valabhji P: Radiological diagnosis and management of a solitary tuberculous hepatic abscess. Br J Radiol. 1990; 63 (755): 902–4. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 5. Hickey AJ, Gounder L, Moosa MY, et al. : A systematic review of hepatic tuberculosis with considerations in human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2015; 15 : 209. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 6. Wu Z, Wang WL, Zhu Y, et al. : Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic tuberculosis: report of five cases and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013; 6 (9): 845–50. PubMed Abstract | Free Full Text

- 7. Ramappa V, Aithal GP: Hepatotoxicity related to anti-tuberculosis drugs: mechanisms and management. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013; 3 (1): 37–49. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 8. Sonika U, Kar P: Tuberculosis and liver disease: management issues. Trop Gastroenterol. 2012; 33 (2): 102–6. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 9. https://nepalntp.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National-Tuberculosis-Management-Guidelines-2019_Nepal.pdf . .

- 10. Levine C: Primary macronodular hepatic tuberculosis: US and CT appearances. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990; 15 (4): 307–9. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 11. Sanchez-Codez M, Hunt WG, Watson J, et al. : Hepatitis in children with tuberculosis: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Pulm Med. 2020; 20 (1): 173. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 12. Shastri M, Kausadikar S, Jariwala J, et al. : Isolated hepatic tuberculosis: An uncommon presentation of a common culprit. Australas Med J. 2014; 7 (6): 247–50. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 13. Essop AR, Posen JA, Hodkinson JH, et al. : Tuberculosis hepatitis: a clinical review of 96 cases. Q J Med. 1984; 53 (212): 465–77. PubMed Abstract

- 14. Kumar N, Kedarisetty CK, Kumar S, et al. : Antitubercular therapy in patients with cirrhosis: challenges and options. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20 (19): 5760–72. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

Comments on this article Comments (0)

Open peer review.

Competing Interests: No competing interests were disclosed.

Reviewer Expertise: Tuberculosis, Interventional Pulmonology, ILD

- Respond or Comment

- COMMENT ON THIS REPORT

Reviewer Expertise: History of Tuberculosis, Global Health, South and Southeast Asia, Medical Humanities

Is the background of the case’s history and progression described in sufficient detail?

Are enough details provided of any physical examination and diagnostic tests, treatment given and outcomes?

Is sufficient discussion included of the importance of the findings and their relevance to future understanding of disease processes, diagnosis or treatment?

Is the case presented with sufficient detail to be useful for other practitioners?

Reviewer Expertise: Management of HIV/tuberculosis; PK/PD for tuberculosis

- Author Response 16 Oct 2020 Sudeep Adhikari , Internal Medicine, Patan Academy of Health Sciences, Lalitpur, Nepal 16 Oct 2020 Author Response We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. The title needs to convey that ... Continue reading We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. The title needs to convey that this is new onset transaminitis attributed to tuberculosis prior to commencement of anti tubercular therapy Response: Title has been modified. Thank you Background Please outline the baseline work up for TB in programmatic setting in Nepal. Do all patients have baseline LFTs done? Response: Programmatic setting does not require any baseline workup except sputum smear and in chest Xray. But in hospital setting, we perform baseline blood investigations like blood counts, renal function, electrolytes and liver function tests before starting treatment, so that treatment can be modified accordingly. Changes have been made in the background section. Case presentation Has this patient had normal LFTs recorded prior to current TB presentation? Response: No prior LFT testing was done by the patient Mention drug history incl. paracetamol, aflatoxin exposure, family history of liver disease. Text has been modified to state the fact. Thank you The liver screen is incomplete - e.g. autoimmune and inherited liver disease, paracetamol levels, ferritin, occult hep B. Also liver fibrosis assessment. Baseline GGT and clotting needs to be given. Please give a table of ALT, AST, GGT, Alk phos, Albumin and clotting during first 2 weeks of treatment (and any further tests during 6 months of treatment) Of note, there is no clear evidence of disseminated miliary TB on CXR. Abdominal or liver CT was not done. Hence, no comment can be made regarding liver/splenic micronodular abscesses. It appears no mycobacterial blood cultures were taken to assess for bacteraemia. Nor was a liver biopsy done. All relevant negatives and limitations should be mentioned. Response: The liver disease screen is incomplete as the reviewer pointed out. However, because of resource limitation and financial constraints, it is not usually possible to perform full liver disease screening in Nepal. So we usually opt for limited screen, and rely more on history, physical examination and initial limited investigations. Then we perform further tests only if the initial workup hints towards another etiology. Text has been modified to include investigations and other limitations. When was she discharged? Response: She was discharged after 1 week after becoming afebrile and improvement in transaminases. Considering she was never symptomatic from the point of view of GI/hepatobiliary system, was there no further blood work to monitor LFTs since discharge? Response: LFT was repeated first at 1 week before discharge, then at 2 months follow up after discharge. Discussion: Briefly explain classifications of liver TB e.g. Reed, Alvarez, Levine. The authors do not clearly say what clinical, biochemical, radiological and histopathological presentation would be seen with disseminated TB involving liver. This case does not clearly illustrate steps to confirm a transaminitis secondary disseminated miliary TB. Response: Text has been modified to include further discussion. Thank you The implications of this case report would have greater impact and relevance for practitioners in the context of a case series or retrospective cohort and the authors should consider doing this. Response: Yes we hope further case reports and case series would be published in future, and we look forward to do case series and we have included this notion in the ms. Thank you. Further discussion is needed of considerations such as potentiated toxicity with pharmacogenomic factors e.g. slow acetylators, the need for individualized monitoring e.g. therapeutic drug monitoring. Response: Further discussion has been added. Unfortunately such therapeutic drug monitoring is not widely available in Nepal. How long should these patients have monitoring of their LFTs? Is there are risk of paradoxical reactions? Unlike Drug induced liver injury, there is no specific monitoring protocols for patients described in our case. The monitoring should be done till the deranged tests normalize and patient becomes clinically well. We have not encountered paradoxical reactions so far. We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. The title needs to convey that this is new onset transaminitis attributed to tuberculosis prior to commencement of anti tubercular therapy Response: Title has been modified. Thank you Background Please outline the baseline work up for TB in programmatic setting in Nepal. Do all patients have baseline LFTs done? Response: Programmatic setting does not require any baseline workup except sputum smear and in chest Xray. But in hospital setting, we perform baseline blood investigations like blood counts, renal function, electrolytes and liver function tests before starting treatment, so that treatment can be modified accordingly. Changes have been made in the background section. Case presentation Has this patient had normal LFTs recorded prior to current TB presentation? Response: No prior LFT testing was done by the patient Mention drug history incl. paracetamol, aflatoxin exposure, family history of liver disease. Text has been modified to state the fact. Thank you The liver screen is incomplete - e.g. autoimmune and inherited liver disease, paracetamol levels, ferritin, occult hep B. Also liver fibrosis assessment. Baseline GGT and clotting needs to be given. Please give a table of ALT, AST, GGT, Alk phos, Albumin and clotting during first 2 weeks of treatment (and any further tests during 6 months of treatment) Of note, there is no clear evidence of disseminated miliary TB on CXR. Abdominal or liver CT was not done. Hence, no comment can be made regarding liver/splenic micronodular abscesses. It appears no mycobacterial blood cultures were taken to assess for bacteraemia. Nor was a liver biopsy done. All relevant negatives and limitations should be mentioned. Response: The liver disease screen is incomplete as the reviewer pointed out. However, because of resource limitation and financial constraints, it is not usually possible to perform full liver disease screening in Nepal. So we usually opt for limited screen, and rely more on history, physical examination and initial limited investigations. Then we perform further tests only if the initial workup hints towards another etiology. Text has been modified to include investigations and other limitations. When was she discharged? Response: She was discharged after 1 week after becoming afebrile and improvement in transaminases. Considering she was never symptomatic from the point of view of GI/hepatobiliary system, was there no further blood work to monitor LFTs since discharge? Response: LFT was repeated first at 1 week before discharge, then at 2 months follow up after discharge. Discussion: Briefly explain classifications of liver TB e.g. Reed, Alvarez, Levine. The authors do not clearly say what clinical, biochemical, radiological and histopathological presentation would be seen with disseminated TB involving liver. This case does not clearly illustrate steps to confirm a transaminitis secondary disseminated miliary TB. Response: Text has been modified to include further discussion. Thank you The implications of this case report would have greater impact and relevance for practitioners in the context of a case series or retrospective cohort and the authors should consider doing this. Response: Yes we hope further case reports and case series would be published in future, and we look forward to do case series and we have included this notion in the ms. Thank you. Further discussion is needed of considerations such as potentiated toxicity with pharmacogenomic factors e.g. slow acetylators, the need for individualized monitoring e.g. therapeutic drug monitoring. Response: Further discussion has been added. Unfortunately such therapeutic drug monitoring is not widely available in Nepal. How long should these patients have monitoring of their LFTs? Is there are risk of paradoxical reactions? Unlike Drug induced liver injury, there is no specific monitoring protocols for patients described in our case. The monitoring should be done till the deranged tests normalize and patient becomes clinically well. We have not encountered paradoxical reactions so far. Competing Interests: none Close Report a concern Reply -->

- The authors describe a patient with pulmonary tuberculosis and raised liver enzymes (Transaminases). They do mention that the patient did not have any preexisting liver disease or drug use, but do not mention how they systematically ruled out other causes of tansaminitis (other non A-E viral hepatitis like GBV, Hep G, EBV,TT virus and other tropical infections).

- “In this report, we gave full dose standard antitubercular drugs, and the liver injury resolved evidenced by normalization of transaminases”. The authors should make their message more clear to “presence of transamnitis with no obvious common underlying etiology may not warrant a modification of standard antitubercular regimen”

- Evaluation of patient: Diagnostic work-up is incomplete and should also include evaluation for degree of hepatocellular injury. Prothrombin time is not mentioned, GGT levels not mentioned, Serum globulin levels not mentioned (hepatic TB has inverted albumin to globulin ration), imaging was limited (only USG performed, CT not done), liver biopsy not performed. More investigations should have been performed to rule out underlying chronic liver diseases: Fibroscan, upper GI endoscopy for Portal HTN)

- Figure 1: The quality of the image is suboptimal. The entire bony cage is not visible. Right costophrenic angle is not visible. Finding of hyperinflated lung fields and blunting of left CP angle are not described. Did the patient have underlying obstructive airway disease? If so did she also have pulmonary hypertension?. Could hepatic congestion due to RHF explain the raised liver enzymes?

- Follow up: The patient improved significantly at 1 month follow up. It would be desirable to have a complete follow up of the patient with evaluation of liver enzymes at least once during treatment as patient initially also did not have any liver specific symptoms.

- The authors argue that the patient did not have underlying liver disease or liver involvement due to tuberculosis as there was no features of Granuloma and cholestatic pattern of liver enzyme elevation. To ascribe the transamnitis to be caused by TB would be an arbitrary statement especially in the absence of liver biopsy.

- The authors mention that they have found many patients of pulmonary TB to have predominant transamnitis and without any preexisting liver disease in their experience. Such statement is not backed by any formal data.

- The authors conclude that pulmonary TB was the cause of transamnitis in their patient, not hepatic TB or underlying liver disease. In the absence of complete workup, such strong conclusions should not be made.

- Author Response 16 Oct 2020 Sudeep Adhikari , Internal Medicine, Patan Academy of Health Sciences, Lalitpur, Nepal 16 Oct 2020 Author Response We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. Title: The title ... Continue reading We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. Title: The title is unclear as to whether the transaminitis in the index patient is caused by tuberculosis (as proposed by the authors in the subsequent report) or a consequence of other coexisting condition. The title needs to be rephrased as to impart a message that the authors want to convey Response: Title has been modified to make our message clearer. Thank you Abstract: The authors describe a patient with pulmonary tuberculosis and raised liver enzymes (Transaminases). They do mention that the patient did not have any preexisting liver disease or drug use, but do not mention how they systematically ruled out other causes of tansaminitis (other non A-E viral hepatitis like GBV, Hep G, EBV,TT virus and other tropical infections). ○ References: DOI: 10.5812/hepatmon.188651; Alter HJ, Bradley DW. Non-A, non-B hepatitis unrelated to the hepatitis C virus (non ABC) Semin Liver Dis 1995; 15:110-1202; Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases: October 2002 - Volume 15 - Issue 5 - p 529-5343. Testing of other viruses were not done due to unavailability.Since raised transaminases resolved after starting ATT we assumed tuberculosis was most likely explanation. “In this report, we gave full dose standard antitubercular drugs, and the liver injury resolved evidenced by normalization of transaminases”. The authors should make their message more clear to “presence of transaminitis with no obvious common underlying etiology may not warrant a modification of standard antitubercular regimen” Response: Text has been modified to make our message clearer. Thank you Case report Evaluation of patient: Diagnostic work-up is incomplete and should also include evaluation for degree of hepatocellular injury. Prothrombin time is not mentioned, GGT levels not mentioned, Serum globulin levels not mentioned (hepatic TB has inverted albumin to globulin ration), imaging was limited (only USG performed, CT not done), liver biopsy not performed. More investigations should have been performed to rule out underlying chronic liver diseases: Fibroscan, upper GI endoscopy for Portal HTN) Response: The liver disease screen is incomplete as the reviewers pointed out. However, because of resource limitation and financial constraints, it is not usually possible to perform full liver disease screening in Nepal. So we usually opt for limited screen, and rely more on history, physical examination and initial limited investigations. Then we perform further tests only if the initial workup hints towards another etiology. Text has been modified to include further lab reports. The limitations have been acknowledged. Figure 1: The quality of the image is suboptimal. The entire bony cage is not visible. Right costophrenic angle is not visible. Finding of hyperinflated lung fields and blunting of left CP angle are not described. Did the patient have underlying obstructive airway disease? If so did she also have pulmonary hypertension?. Could hepatic congestion due to RHF explain the raised liver enzymes? Response: There was no history of underlying lung disease. Although echocardiography was not done hepatic congestion due to RHF is unlikely as there was no suggestive history and examination findings and patient responded without any diuretics or fluid restrictions. Follow up: The patient improved significantly at 1 month follow up. It would be desirable to have a complete follow up of the patient with evaluation of liver enzymes at least once during treatment as patient initially also did not have any liver specific symptoms. Response: Text has been modified to include follow up reports. LFT was repeated first at 1 week before discharge, then at 2 months follow up after discharge. Discussion: The authors argue that the patient did not have underlying liver disease or liver involvement due to tuberculosis as there was no features of Granuloma and cholestatic pattern of liver enzyme elevation. To ascribe the transaminitis to be caused by TB would be an arbitrary statement especially in the absence of liver biopsy. Response: Imaging and further investigations were limited, so hepatic tuberculosis could not be ruled out with certainty especially without biopsy of liver. However this would not make much difference. Because even if the diagnosis of hepatic tuberculosis had been considered in our patient, the management would be the same, i.e. with standard ATT as we did in our patient. The point we wanted to make here is that modification in treatment may not be required in the absence of pre-existing liver disease. Text has been modified to include the limitations. Thank you The authors mention that they have found many patients of pulmonary TB to have predominant transaminitis and without any preexisting liver disease in their experience. Such statement is not backed by any formal data. Response: We need more data but unfortunately not much is being published from low middle income countries even for endemic diseases like tuberculosis. There is no formal data to back up our claim, and this has been acknowledged as limitation. The authors conclude that pulmonary TB was the cause of transaminitis in their patient, not hepatic TB or underlying liver disease. In the absence of complete workup, such strong conclusions should not be made. Response: Due to rapid resolution of raised transaminases after starting ATT, preexisting liver disease would be unlikely cause. Although hepatic tb is a possibility, it was our opinion that standard dose ATT can be safely started in the patient and further imaging would not be cost effective in terms of treatment. We agree with the reviewer that the strong conclusions are not justified due to incomplete workup and this section has been toned down and modified to highlight the limitations. Thank you Conclusion The authors recommend use of full dose standard ATT for patients with transaminitis and no underlying liver disease. This recommendation should not be made based on a single case report. Response: We agree. Text have been modified to include our limitations. Thank you. Opinion: The case report describes a common scenario especially in low income countries while treating patients with tuberculosis. The availability of resources limit the diagnostic workup of such patients in our settings. I opine that this case report is suitable for indexing with modifications. Response: Thank you We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. Title: The title is unclear as to whether the transaminitis in the index patient is caused by tuberculosis (as proposed by the authors in the subsequent report) or a consequence of other coexisting condition. The title needs to be rephrased as to impart a message that the authors want to convey Response: Title has been modified to make our message clearer. Thank you Abstract: The authors describe a patient with pulmonary tuberculosis and raised liver enzymes (Transaminases). They do mention that the patient did not have any preexisting liver disease or drug use, but do not mention how they systematically ruled out other causes of tansaminitis (other non A-E viral hepatitis like GBV, Hep G, EBV,TT virus and other tropical infections). ○ References: DOI: 10.5812/hepatmon.188651; Alter HJ, Bradley DW. Non-A, non-B hepatitis unrelated to the hepatitis C virus (non ABC) Semin Liver Dis 1995; 15:110-1202; Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases: October 2002 - Volume 15 - Issue 5 - p 529-5343. Testing of other viruses were not done due to unavailability.Since raised transaminases resolved after starting ATT we assumed tuberculosis was most likely explanation. “In this report, we gave full dose standard antitubercular drugs, and the liver injury resolved evidenced by normalization of transaminases”. The authors should make their message more clear to “presence of transaminitis with no obvious common underlying etiology may not warrant a modification of standard antitubercular regimen” Response: Text has been modified to make our message clearer. Thank you Case report Evaluation of patient: Diagnostic work-up is incomplete and should also include evaluation for degree of hepatocellular injury. Prothrombin time is not mentioned, GGT levels not mentioned, Serum globulin levels not mentioned (hepatic TB has inverted albumin to globulin ration), imaging was limited (only USG performed, CT not done), liver biopsy not performed. More investigations should have been performed to rule out underlying chronic liver diseases: Fibroscan, upper GI endoscopy for Portal HTN) Response: The liver disease screen is incomplete as the reviewers pointed out. However, because of resource limitation and financial constraints, it is not usually possible to perform full liver disease screening in Nepal. So we usually opt for limited screen, and rely more on history, physical examination and initial limited investigations. Then we perform further tests only if the initial workup hints towards another etiology. Text has been modified to include further lab reports. The limitations have been acknowledged. Figure 1: The quality of the image is suboptimal. The entire bony cage is not visible. Right costophrenic angle is not visible. Finding of hyperinflated lung fields and blunting of left CP angle are not described. Did the patient have underlying obstructive airway disease? If so did she also have pulmonary hypertension?. Could hepatic congestion due to RHF explain the raised liver enzymes? Response: There was no history of underlying lung disease. Although echocardiography was not done hepatic congestion due to RHF is unlikely as there was no suggestive history and examination findings and patient responded without any diuretics or fluid restrictions. Follow up: The patient improved significantly at 1 month follow up. It would be desirable to have a complete follow up of the patient with evaluation of liver enzymes at least once during treatment as patient initially also did not have any liver specific symptoms. Response: Text has been modified to include follow up reports. LFT was repeated first at 1 week before discharge, then at 2 months follow up after discharge. Discussion: The authors argue that the patient did not have underlying liver disease or liver involvement due to tuberculosis as there was no features of Granuloma and cholestatic pattern of liver enzyme elevation. To ascribe the transaminitis to be caused by TB would be an arbitrary statement especially in the absence of liver biopsy. Response: Imaging and further investigations were limited, so hepatic tuberculosis could not be ruled out with certainty especially without biopsy of liver. However this would not make much difference. Because even if the diagnosis of hepatic tuberculosis had been considered in our patient, the management would be the same, i.e. with standard ATT as we did in our patient. The point we wanted to make here is that modification in treatment may not be required in the absence of pre-existing liver disease. Text has been modified to include the limitations. Thank you The authors mention that they have found many patients of pulmonary TB to have predominant transaminitis and without any preexisting liver disease in their experience. Such statement is not backed by any formal data. Response: We need more data but unfortunately not much is being published from low middle income countries even for endemic diseases like tuberculosis. There is no formal data to back up our claim, and this has been acknowledged as limitation. The authors conclude that pulmonary TB was the cause of transaminitis in their patient, not hepatic TB or underlying liver disease. In the absence of complete workup, such strong conclusions should not be made. Response: Due to rapid resolution of raised transaminases after starting ATT, preexisting liver disease would be unlikely cause. Although hepatic tb is a possibility, it was our opinion that standard dose ATT can be safely started in the patient and further imaging would not be cost effective in terms of treatment. We agree with the reviewer that the strong conclusions are not justified due to incomplete workup and this section has been toned down and modified to highlight the limitations. Thank you Conclusion The authors recommend use of full dose standard ATT for patients with transaminitis and no underlying liver disease. This recommendation should not be made based on a single case report. Response: We agree. Text have been modified to include our limitations. Thank you. Opinion: The case report describes a common scenario especially in low income countries while treating patients with tuberculosis. The availability of resources limit the diagnostic workup of such patients in our settings. I opine that this case report is suitable for indexing with modifications. Response: Thank you Competing Interests: none Close Report a concern Reply -->

- Author Response 16 Oct 2020 Sudeep Adhikari , Internal Medicine, Patan Academy of Health Sciences, Lalitpur, Nepal 16 Oct 2020 Author Response We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. Title: ... Continue reading We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. Title: Drug-resistant TB is a hot topic in medicine today. Research on TB treatment-associated transaminitis would further the existing scholarly understanding on drug-resistant TB. A close keyword search on PubMed revealed only 17 hit on TB AND transaminitis. For this reason, the case report is potentially publishable but suffers from several drawbacks in its current draft that must be remedied before the contribution is re-refereed. But the title itself is unclear. “With” is repeated twice. It is not clear to a medical historian what transaminitis is. A better framing of the title is urgently needed. A cogent argument can be organised around the title. What is four-drugs therapy? It is clear to medical practitioners but not clear to the larger scholarly community. Avoid jargons in the title. 1) What is transaminitis? Why not provide a brief explanation at the start so that the general reader can follow the rest of the article. 2) The two levels of transaminitis: (a) pre-existing liver disease leads to transaminitis. (b) Hepatoxicity of anti-TB drugs. This needs to be made explicit in the very beginning. The authors have not been explicit about the two levels of transaminitis and that is where the problem begins. “While encountering such patients, it is important to differentiate if the patient had pre-existing liver disease or if the present infection with tuberculosis has impacted on the liver, as the approach to management differs given the hepatotoxicity associated with first line drugs.” Rewrite this sentence. Make more explicit. Response: Title and text have been modified to make our message clearer. Thank you Summary and Abstract: The writers present a case of pulmonary TB with transaminitis without pre-existing liver damage. The therapeutic regimen of the authors included anti-TB drugs and liver injury resolved evidenced by normalization of transaminase. The abstract merits rewriting for clarity. Response: Abstract has been modified to make our message clearer Background: Needs to sketch out the larger socio-economic picture of TB patients in Nepal. Medicine for whom? Response: Background has been modified to make it clear. The socioeconomic picture of TB patients in Nepal has been highlighted. In Nepal, tuberculosis prevalence is more in productive age group (25-64 years) and men. Poverty, malnutrition, overcrowding, immunocompromised state like HIV infection, alcohol, smoking, air pollution, diabetes and other comorbidities are important risk factors for acquiring the disease. All patients diagnosed with TB receive treatment as per the national protocol which has been mentioned in the text. Case Presentation: How do you define compliance with TB treatment? How socio-economic factors militate against the successful completion of treatment? Response: To improve the treatment compliance, treatment of TB is done under DOTS program all over Nepal, which stands for ‘Directly Observed Treatment Short Course’. Otherwise the compliance would be compromised owing to the lower socioeconomic status of patients, longer duration of therapy and side effects of drugs. Specific quote from the report: “In our anecdotal experience, we have found many patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, similarly to subject of this case report, present with predominant transaminitis and without pre-existing liver disease or drugs-use. They are often managed with modified liver-friendly antitubercular regimens for fear of increasing the hepatotoxicity and causing acute liver failure with the use of standard regimen. Few case reports are available in literature reporting the use of the modified regimens. We believe such cases are underreported, and firm guidelines have not been established to guide clinicians in these cases. Given this, many clinicians in low-middle income countries, including Nepal, who have been treating tuberculosis patients tend to be skeptical in using full doses of first line ATT in such patients and tend to use a modified regimen. However, this practice may potentially lead to undertreatment and therefore increase fatality9. Though there was some hesitation at first in our case, we soon started treatment with the standard ATT in our patient with close monitoring. This we believe led to the resolution of liver injury, evidenced by the normalization of transaminases.” What is your sample size? Unclear. What guidelines can be established with the aid of the study?" Make explicit and elaborate Response: Our opinion is that there are cases of pulmonary tb with some hepatic involvement, which are sometimes being managed with modified regimen when it can be safely managed with standard regimen. Unfortunately very few published research is available from low middle income countries. Text has been edited to include limitation of evidence. This is a case report only and further research is needed. Conclusion: The report lacks an inevitable conclusion. The conclusion needs to point to the “so what” question? So, what are the implications of this study? What protocols could be devised? How does this case history further medical practitioners’ as well as policymakers’ understanding of drug-resistant TB? Response: Being a case report and paucity of previous research, we have toned down our previous strong conclusions, also as suggested above by another reviewer. We hope that further reports will be published. The use of modified drug regimen excluding more potent drugs, instead of standard regimen may promote drug resistance, and how far such practices are prevalent can be another area of further study. Other points: Please make sure that the manuscript is thoroughly copyedited for legibility of prose, clarity of argument, and grammar. The social context of TB in Nepal merits attention (alcoholism is a contributing factor). You need to compare transaminitis with case studies from other countries. Carefully refer to the PLoS Response: Text has been revised to correct errors. Social context of TB in Nepal has been mentioned in the text. Thank you Murphy, Richard A., Vincent C. Marconi, Rajesh T. Gandhi, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, and Henry Sunpath. "Coadministration of lopinavir/ritonavir and rifampicin in HIV and tuberculosis co-infected adults in South Africa." PLoS One 7, no. 9 (2012): e447931. Sarda, Pawan, S. K. Sharma, Alladi Mohan, Govind Makharia, Arvind Jayaswal, R. M. Pandey, and Sarman Singh. "Role of acute viral hepatitis as a confounding factor in antituberculosis treatment induced hepatotoxicity." Indian Journal of Medical Research 129, no. 1 (2009): 642. How does your case differ from the 2 references mentioned above? Response: As compared to first article our patient did not have HIV. As compared to second article, our patient did not have antituberculous drug induced hepatotoxicity but liver injury likely due to tuberculosis itself. Thank you We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. Title: Drug-resistant TB is a hot topic in medicine today. Research on TB treatment-associated transaminitis would further the existing scholarly understanding on drug-resistant TB. A close keyword search on PubMed revealed only 17 hit on TB AND transaminitis. For this reason, the case report is potentially publishable but suffers from several drawbacks in its current draft that must be remedied before the contribution is re-refereed. But the title itself is unclear. “With” is repeated twice. It is not clear to a medical historian what transaminitis is. A better framing of the title is urgently needed. A cogent argument can be organised around the title. What is four-drugs therapy? It is clear to medical practitioners but not clear to the larger scholarly community. Avoid jargons in the title. 1) What is transaminitis? Why not provide a brief explanation at the start so that the general reader can follow the rest of the article. 2) The two levels of transaminitis: (a) pre-existing liver disease leads to transaminitis. (b) Hepatoxicity of anti-TB drugs. This needs to be made explicit in the very beginning. The authors have not been explicit about the two levels of transaminitis and that is where the problem begins. “While encountering such patients, it is important to differentiate if the patient had pre-existing liver disease or if the present infection with tuberculosis has impacted on the liver, as the approach to management differs given the hepatotoxicity associated with first line drugs.” Rewrite this sentence. Make more explicit. Response: Title and text have been modified to make our message clearer. Thank you Summary and Abstract: The writers present a case of pulmonary TB with transaminitis without pre-existing liver damage. The therapeutic regimen of the authors included anti-TB drugs and liver injury resolved evidenced by normalization of transaminase. The abstract merits rewriting for clarity. Response: Abstract has been modified to make our message clearer Background: Needs to sketch out the larger socio-economic picture of TB patients in Nepal. Medicine for whom? Response: Background has been modified to make it clear. The socioeconomic picture of TB patients in Nepal has been highlighted. In Nepal, tuberculosis prevalence is more in productive age group (25-64 years) and men. Poverty, malnutrition, overcrowding, immunocompromised state like HIV infection, alcohol, smoking, air pollution, diabetes and other comorbidities are important risk factors for acquiring the disease. All patients diagnosed with TB receive treatment as per the national protocol which has been mentioned in the text. Case Presentation: How do you define compliance with TB treatment? How socio-economic factors militate against the successful completion of treatment? Response: To improve the treatment compliance, treatment of TB is done under DOTS program all over Nepal, which stands for ‘Directly Observed Treatment Short Course’. Otherwise the compliance would be compromised owing to the lower socioeconomic status of patients, longer duration of therapy and side effects of drugs. Specific quote from the report: “In our anecdotal experience, we have found many patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, similarly to subject of this case report, present with predominant transaminitis and without pre-existing liver disease or drugs-use. They are often managed with modified liver-friendly antitubercular regimens for fear of increasing the hepatotoxicity and causing acute liver failure with the use of standard regimen. Few case reports are available in literature reporting the use of the modified regimens. We believe such cases are underreported, and firm guidelines have not been established to guide clinicians in these cases. Given this, many clinicians in low-middle income countries, including Nepal, who have been treating tuberculosis patients tend to be skeptical in using full doses of first line ATT in such patients and tend to use a modified regimen. However, this practice may potentially lead to undertreatment and therefore increase fatality9. Though there was some hesitation at first in our case, we soon started treatment with the standard ATT in our patient with close monitoring. This we believe led to the resolution of liver injury, evidenced by the normalization of transaminases.” What is your sample size? Unclear. What guidelines can be established with the aid of the study?" Make explicit and elaborate Response: Our opinion is that there are cases of pulmonary tb with some hepatic involvement, which are sometimes being managed with modified regimen when it can be safely managed with standard regimen. Unfortunately very few published research is available from low middle income countries. Text has been edited to include limitation of evidence. This is a case report only and further research is needed. Conclusion: The report lacks an inevitable conclusion. The conclusion needs to point to the “so what” question? So, what are the implications of this study? What protocols could be devised? How does this case history further medical practitioners’ as well as policymakers’ understanding of drug-resistant TB? Response: Being a case report and paucity of previous research, we have toned down our previous strong conclusions, also as suggested above by another reviewer. We hope that further reports will be published. The use of modified drug regimen excluding more potent drugs, instead of standard regimen may promote drug resistance, and how far such practices are prevalent can be another area of further study. Other points: Please make sure that the manuscript is thoroughly copyedited for legibility of prose, clarity of argument, and grammar. The social context of TB in Nepal merits attention (alcoholism is a contributing factor). You need to compare transaminitis with case studies from other countries. Carefully refer to the PLoS Response: Text has been revised to correct errors. Social context of TB in Nepal has been mentioned in the text. Thank you Murphy, Richard A., Vincent C. Marconi, Rajesh T. Gandhi, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, and Henry Sunpath. "Coadministration of lopinavir/ritonavir and rifampicin in HIV and tuberculosis co-infected adults in South Africa." PLoS One 7, no. 9 (2012): e447931. Sarda, Pawan, S. K. Sharma, Alladi Mohan, Govind Makharia, Arvind Jayaswal, R. M. Pandey, and Sarman Singh. "Role of acute viral hepatitis as a confounding factor in antituberculosis treatment induced hepatotoxicity." Indian Journal of Medical Research 129, no. 1 (2009): 642. How does your case differ from the 2 references mentioned above? Response: As compared to first article our patient did not have HIV. As compared to second article, our patient did not have antituberculous drug induced hepatotoxicity but liver injury likely due to tuberculosis itself. Thank you Competing Interests: none Close Report a concern Reply -->

Reviewer Status

Alongside their report, reviewers assign a status to the article:

Reviewer Reports

- Vivek Neelakantan , Independent Medical Historian, Mumbai, India

- Prajowl Shrestha , Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal Ashesh Dhungana , Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal

- Neesha Rockwood , University of Cape Town, London, UK; University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa; University of Colombo, Colombu, Sri Lanka

Comments on this article

All Comments (0)

Competing Interests Policy

Provide sufficient details of any financial or non-financial competing interests to enable users to assess whether your comments might lead a reasonable person to question your impartiality. Consider the following examples, but note that this is not an exhaustive list:

- Within the past 4 years, you have held joint grants, published or collaborated with any of the authors of the selected paper.

- You have a close personal relationship (e.g. parent, spouse, sibling, or domestic partner) with any of the authors.

- You are a close professional associate of any of the authors (e.g. scientific mentor, recent student).

- You work at the same institute as any of the authors.

- You hope/expect to benefit (e.g. favour or employment) as a result of your submission.

- You are an Editor for the journal in which the article is published.

- You expect to receive, or in the past 4 years have received, any of the following from any commercial organisation that may gain financially from your submission: a salary, fees, funding, reimbursements.

- You expect to receive, or in the past 4 years have received, shared grant support or other funding with any of the authors.

- You hold, or are currently applying for, any patents or significant stocks/shares relating to the subject matter of the paper you are commenting on.

Stay Updated

Sign up for content alerts and receive a weekly or monthly email with all newly published articles

Register with Wellcome Open Research

Already registered? Sign in

Not now, thanks

Are you a Wellcome-funded researcher?

If you are a previous or current Wellcome grant holder, sign up for information about developments, publishing and publications from Wellcome Open Research.

We'll keep you updated on any major new updates to Wellcome Open Research

The email address should be the one you originally registered with F1000.

You registered with F1000 via Google, so we cannot reset your password.

To sign in, please click here .

If you still need help with your Google account password, please click here .

You registered with F1000 via Facebook, so we cannot reset your password.

If you still need help with your Facebook account password, please click here .

If your email address is registered with us, we will email you instructions to reset your password.

If you think you should have received this email but it has not arrived, please check your spam filters and/or contact for further assistance.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 17 January 2019

Bacteriologically confirmed extra pulmonary tuberculosis and treatment outcome of patients consulted and treated under program conditions in the littoral region of Cameroon

- Teyim Pride Mbuh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0593-6831 1 , 3 ,

- Irene Ane-Anyangwe 1 ,

- Wandji Adeline 3 ,

- Benjamin D. Thumamo Pokam 2 ,

- Henry Dilonga Meriki 1 &

- Wilfred Fon Mbacham 4

BMC Pulmonary Medicine volume 19 , Article number: 17 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

7777 Accesses

22 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) is defined as any bacteriologically confirmed or clinically diagnosed case of TB involving organs other than the lungs. It is frequently a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge with paucity of data available. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of bacteriologically confirmed EPTB; to determine the most affected organs and to evaluate the therapeutic outcome of EPTB patients treated under program conditions in the littoral region of Cameroon.

A descriptive cross-sectional laboratory-based epidemiological survey was conducted from January 2016 to December 2017 and 109 specimens from 15 of the 39 diagnosis and treatment centers in the littoral region were obtained.

Two diagnostic methods (Gene Xpert MTB and culture (LJ and MGIT) were used for EPTB diagnosis. Determine HIV1/2 and SD Biolinewere used for HIV diagnosis. Confirmed EPTB cases were treated following the national tuberculosis guide.

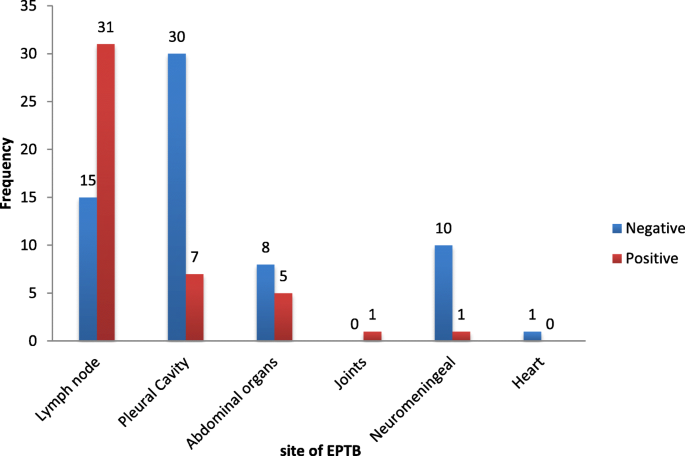

The prevalence of bacteriologically confirmed EPTB was 41.3% (45). All 45 cases were sensitive to rifampicin. Males were predominately more infected [26 (57.8%)] likewise the age group 31–45 years with 15 (33.3%) cases. The overall prevalence for HIV was 33.6% (36). HIV infection was present in 28.9% (13) of patients with EPTB. The most affected sites with EPTB were: Lymph nodes (66.5%), pleural cavity (15.6%), abdominal organs (11.1%), neuromeningeal (2.2%), joints (2.2%) and heart (2.2%). Overall, 84.4% of the study participants had a therapeutic success with males responding better 57.9% ( p = 0.442). Therapeutic success was better (71.7%) in HIV negative EPTB patients ( p = 0.787).

The prevalence of bacteriologically confirmed EPTB patients treated under program conditions in the littoral region of Cameroon is high with a therapeutic success of 84.4% and the lymph nodes is the most affected site.

Peer Review reports

Tuberculosis (TB) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for about 9.6 million new cases and 1.5 million deaths annually [ 1 ].