Asian Review of Political Economy

- Focuses on conventional and emerging topics of political economy.

- Promotes a comprehensive understanding of the political economy of Asia and beyond.

- Encourages interdisciplinary studies across different issue areas and fields of inquiry.

- Committed to publishing works valuable to the academy, governments, and non-governmental sectors.

- APC fully sponsored by Shanghai Jiao Tong University and a special fund from IIA, CUHK, Shenzhen, ensuring high visibility for your work with open access.

- Yongnian Zheng

Societies and partnerships

Latest articles

Asean four’s middle income trap dilemma: evidence of the middle technology trap.

Contesting coercion: U.S.-China strategic competition, the middle technology trap, and Chinese government-guided funds

- Xuanming Pan

- Chen Zhenzhen

The middle-income trap and the middle-technology trap in Latin America–practice comparison based on East Asian perspective

- Weichuang Fang

The middle technology trap: China in a comparative perspective

Nexus between digital trade and security: geopolitical implications for global economy in the digital age.

- Xuechen Chen

- Xinchuchu Gao

Journal updates

Call for papers: nexus between digital trade and security: geopolitical implications for global economy in the digital age.

This special issue aims to unpack the geopolitical and security aspects of digital trade in light of the swiftly changing landscape of the international trade regime in the digital age. Through our investigation, we seek to understand the impact of geopolitical and security considerations on the evolving landscape of digital trade at both regional (Asian) and global scales.

Guest editors:

Xuechen Chen, Faculty of Social Science, Northeastern University London, UK

Xinchuchu Gao, School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Lincoln, UK

Jilong Yang, College of International Relations, Huaqiao University, China

Chi Zhang, School of International Relations, University of St Andrews, UK

Call for papers: Governance in Southeast Asia in an Era of Uncertainty

This special issue aims to examine the trends and to explore the causes and consequences of governance in Southeast Asia. We welcome contributions that focus on international, domestic, and/or regional governance, and also encourage submissions that study the interaction among the three.

Guest Editors:

Thomas Pepinsky, Department of Government & Southeast Asian Program, Cornell University, US

Zhaohui Wang, School of International Relations & Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Xiamen University, China

Call for Papers: The Interplay between Basic Research, Research and Development (R&D), Commercialization of Scientific and Technological Achievements, and Sustainable Economic Development

This special issue aims to explore the complex relationships between basic research, research and development (R&D), commercialization of scientific and technological achievements, and sustainable economic development in countries in Asia and beyond, with a particular focus on implications of the interplay of these factors for developing economies.

Yongnian Zheng, The Institute for International Affairs, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China Ping Huang, The Institute for International Affairs, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China Randong Yuan, The Institute for International Affairs, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China

Apply to join now: ARPE Youth Editorial Board 2023-2026

To enhance the quality and impact of the journal and toto engage with your researchers, ARPE is now recruiting Young Editorial Board Members worldwide.

Journal information

- Google Scholar

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- TD Net Discovery Service

Rights and permissions

Editorial policies

© School of International and Public Affairs, Shanghai Jiao Tong University

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Political Economy

- In book: Encyclopedia of Law and Economics (pp.1599-1606)

- Publisher: Springer New York

- University of Münster

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Niyi Adegoke

- Samuel Anesu Muzhingi

- Niels Petersen

- Stephan Leibfried

- Matthew Lange

- Elinor Ostrom

- John Maynard Keynes

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Political Economy

The Political Economy Program examines the interactions among political institutions, participants in the political system, such as voters and elected officials, and economic outcomes broadly defined.

Codirectors

Francesco Trebbi is the Bernard T. Rocca Jr. Professor of Business and Public Policy at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. His research examines the impact of political institutions, including electoral rules, on economic outcomes, and the political economy of policy determination more generally. He has been an NBER affiliate since 2007.

Ebonya L. Washington is the Laurans A. and Arlene Mendelson Professor of Economics and a professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University. Her research explores the economic and institutional factors that influence voter turnout, the determinants of the policy preferences of voters and legislators, the interplay among race, gender, and political outcomes, and a range of other issues. She has been an NBER affiliate since 2004.

Featured Program Content

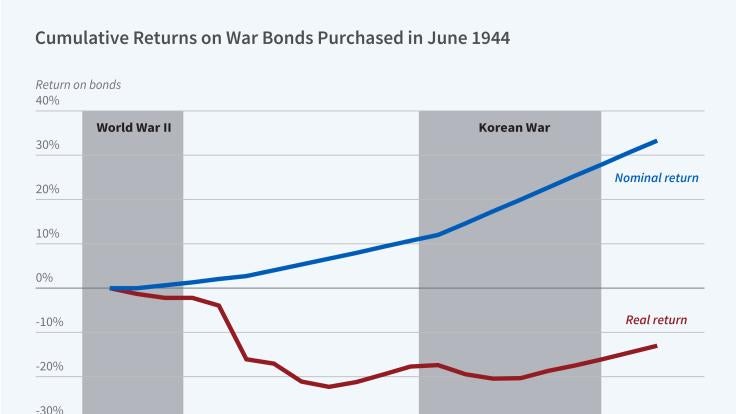

- Authors: Gillian Brunet , Eric Hilt & Matthew S. Jaremski

- Working Paper

- Authors: Francesco Ferlenga & Brian G. Knight

- Authors: Francesco Trebbi & Miao Ben Zhang

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Political Economy

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Last »

- Political Theory Follow Following

- Political Science Follow Following

- Marxism Follow Following

- International Political Economy Follow Following

- Political Philosophy Follow Following

- International Law Follow Following

- Law Follow Following

- Critical Theory Follow Following

- Neoliberalism Follow Following

- Comparative Politics Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Journals

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Penn State University Libraries

Pl sc 412: international political economy (world campus).

- Getting Started

- Exploring Topics

- Search Strategies Exercise

- Journal Articles

- Data Sources

- Specialized Sources

Term Paper Overview

- You will write a term paper on a relevant topic of interest to you. The basic idea is for you to apply a theory or small set of theories to an issue in international political economy to drive predictions regarding the likely course of events over the next 5-10 or 10- 20 years. You will work on the paper in stages and be graded on your work over the course of the semester. After submitting a rough draft, you will review another student’s paper and get peer feedback on your draft.

Term Paper Stages

1. Research Paper Topic : You will write a short paragraph outlining the general topic of your research paper. General topics include, but are not limited to, trade relations, hegemony, the exchange rate, development and globalization. You will then describe the specific subtopic you are interested in. If, for example, your general topic is globalization, some subtopics might be sweatshops or the effect of globalization on the environment.

2. Research Question: You will write one short paragraph that first presents your initial research question. Make sure that your research question asks what factors, variables, or conditions affect some aspect of your subtopic and focuses on cause-and-effect relationships.

- You should avoid descriptive and prescriptive questions. The former leads to research papers that simply describe a process or an event, while the latter results in research papers that tell us what we can or should do to change, fix, or prevent some undesirable situation.

- For example, if your subtopic is the effect of globalization on the environment under the general topic of the globalization, an appropriate research question might be “under what conditions will countries cooperate to reduce pollution?” Inappropriate research questions might be “which states are the biggest polluters?” and “what should be done to reduce pollution?”

3. Bibliography: You will submit a preliminary bibliography that should consist primarily of scholarly works associated with your research topic, such as books, journal articles, and other published studies that have been subjected to peer review. University presses, as well as many other reputable publishers, produce peer-reviewed books.

- American Political Science Review

- American Journal of Political Science

- International Organization

- International Studies Quarterly

- World Politics International

- Journal of Political Economy

- Your bibliography must follow the guidelines found in the American Political Science Association’s Style Manual for Political Science. (See the Citations page of this guide for link.)

4. Theory Overview : The reading you do will allow you to become acquainted with different theories (or "models" as they are often called) about the phenomenon that you’re interested in. Review the most prominent or compelling theories. If there are competing theories, highlight their distinguishing factors.

5. Thesis Statement : You will write one or two sentences that represent your thesis statement. This thesis statement should be a concise summary of your research paper’s argument or analysis. In other words, the thesis statement summarizes your findings, your predictions and your argument. It is “the punch line” of your paper and what follows fills out and supports this statement.

6. Detailed Outline : You will provide a detailed outline of the various sections of your research paper. These sections may include, but are not limited to, the introduction (including your thesis statement), theory review, analysis, and conclusions.

7. Rough Draft : You will submit a rough draft of your research paper for peer review. This draft does not have to be perfect. It simply represents your first attempt to put your thoughts in final form. However, the more work you put into this rough draft, the more likely it is that you will receive useful feedback from the peer review. You will get full credit for submitting the draft. (I will not be grading content at this point.) If you do not submit the rough draft you WILL NOT get any credit for completing a peer review.

8. Peer Review: You will provide constructive feedback on one classmate’s rough draft. Using track changes and the insertion of comments, offer as much constructive criticism on your classmate’s paper as possible. Constructive criticism is criticism that is intended to improve the paper and often identifies solutions to problems in a positive and productive way. You might want to think about this peer review as a valuable opportunity to improve your own writing; as you edit and comment upon your classmate's work, you might discover things that you should or should not do in future essays and research papers. You will not get credit for this portion if you do not submit a rough draft yourself.

9. Final Paper: Your final paper must be between 6-8 pages in length, double-spaced with 12-point Times New Roman font and 1-inch margins. Your paper must also include proper parenthetical citations and bibliography, following the guidelines found in the American Political Science Association’s Style Manual for Political Science. (See the Citations page of this guide for link.) Please upload your paper in Word (or Pages), not pdf.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Exploring Topics >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2024 8:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/WorldCampus/PLSC412

IMAGES

COMMENTS

View content coverage periods and institutional full-run subscription rates for the Journal of Political Economy. *Journal Impact Factor and 5-Year Impact Factor courtesy of the 2023 Journal Citation Reports (JCR) (Clarivate 2024). Scopus CiteScore (Elseview B.V.). Retrieved September 2022, from Scopus.

ABOUT THE JOURNAL. Frequency: 4 issues/year. Journal of Political Economy Macroeconomics (JPE Macro) strives to publish high-quality theoretical and empirical research papers that address issues of relevance to macroeconomics. Macroeconomics is interpreted in a broad sense and includes issues related to the traditional macroeconomic topics of growth, fluctuations, and distribution, as well as ...

Current issues are now on the Chicago Journals website. Read the latest issue. One of the oldest and most prestigious journals in economics, the Journal of Political Economy (JPE) presents significant and essential scholarship in economic theory and practice.The journal publishes highly selective and widely cited analytical, interpretive, and empirical studies in a number of areas, including ...

About the journal. The aim of the European Journal of Political Economy is to disseminate original theoretical and empirical research on economic phenomena within a scope that encompasses collective decision making, political behavior, and the role of institutions. Contributions are invited from the international …. View full aims & scope ...

This lecture by PERI researcher James Boyce, delivered at the ceremony for the inaugural Global Inequality Research Award at Sciences Po in Paris, provides a trajectory of Boyce's work on inequality and the environment that was recognized by the award. Thirty years ago, many economists and environmentalists saw inequality as a non-issue.

The Review of Political Economy is a double anonymized peer-reviewed journal welcoming constructive and critical contributions in all areas of political economy, including Behavioural economics, Ecological economics, Feminist economics, Institutional economics, Kaleckian economics, Marxian economics, Polanyian economics, Post-Keynesian economics, Schumpeterian economics, Sraffian economics, as ...

Review of International Political Economy, Volume 31, Issue 4 (2024) See all volumes and issues. Volume 31, 2024 Vol 30, 2023 Vol 29, 2022 Vol 28, 2021 Vol 27, 2020 Vol 26, 2019 Vol 25, 2018 Vol 24, 2017 Vol 23, 2016 Vol 22, 2015 Vol 21, 2014 Vol 20, 2013 Vol 19, 2012 Vol 18, 2011 Vol 17, 2010 Vol 16, 2009 Vol 15, 2007-2008 Vol 14, 2007 Vol 13 ...

The Review of International Political Economy (RIPE) has successfully established itself as a leading international journal dedicated to the systematic exploration of the international political economy from a plurality of perspectives.. The journal encourages a global and interdisciplinary approach across issues and fields of inquiry. It seeks to act as a point of convergence for political ...

New Political Economy aims to create a forum for work which combines the breadth of vision which characterised the classical political economy of the nineteenth century with the analytical advances of twentieth century social science.. It seeks to represent the terrain of political economy scholarship across different disciplines, emphasising original and innovative work which explores new ...

DOI 10.3386/w32507. Issue Date May 2024. We examine the ways in which political realities shape industrial policy through the lens of modern political economy. We consider two broad "governance constraints": i) the political forces that shape how industrial policy is chosen and ii) the ways in which state capacity affects implementation.

It is argued in this paper that the term economics should be replaced with the earlier term political economy. To do so, the paper ... the authors realized the research potential of modern ...

The political economy plays an important role in good governance with institutionalisation and environmental scanning. This can assist in alleviating social injustice and reducing income inequality in an emerging economy, alongside an expanded formal sector and equitable growth.

Overview. Asian Review of Political Economy publishes theory-driven and policy-oriented research on diverse political economy issues. Focuses on conventional and emerging topics of political economy. Promotes a comprehensive understanding of the political economy of Asia and beyond. Encourages interdisciplinary studies across different issue ...

ABOUT THE JOURNAL. Frequency: 4 issues/year. Journal of Political Economy Microeconomics (JPE Micro) strives to publish high-quality theoretical, empirical, and econometric research papers and replication studies that address issues of relevance to microeconomics.Microeconomics is interpreted in the broadest possible sense and includes issues related to how individuals, households, firms, and ...

DOI 10.3386/w30511. Issue Date September 2022. Culture - the set of socially transmitted values and beliefs held by individuals - has important implications for a wide variety of economic outcomes. Both the causes and consequences of culture have been the subject of work in Historical Political Economy. I first outline several theories on ...

The term "Political Economy" (PE) is mainly used in two related contexts. First, it is used to denote a multidisciplinary research field in which political scientists, economists, legal scholars ...

Volume 25 1995. Volume 24 1994. Volume 23 1993. Volume 22 1992. Volume 21 1991. Volume 20 1990. Volume 19 1989. Volume 18 1988. Browse the list of issues and latest articles from International Journal of Political Economy.

Political Economy. The Political Economy Program examines the interactions among political institutions, participants in the political system, such as voters and elected officials, and economic outcomes broadly defined. Read summaries of presentations at the latest program meeting Read the latest Program Report Affiliated scholars.

1 According to Groenewegen Ž 1987 . , the term ''political economy'' for economics origi-nated in France in the 17th century. He attributes the first use to Montchretien ́ in 1615. Sir James Steurt Ž 1761 . was the first English economist to put the term in the title of a book on economics, An Inquiry into the Principles of Political ...

Copies of working papers are available from the author. #07-037. Abstract. Capitalism is often defined as an economic system where private actors are allowed to own and control the use of property in accord with their own interests, and where the invisible hand of the pricing mechanism coordinates supply and demand in markets in a way that is ...

The research will develop a broad theoretical framework informed by critical political economy and the cycling-related mobility, anthropology, public health, planning, and transportation literature. I review the regime of automobility (the private car and the infrastructure that supports it).

This paper is a development of research carried out by the first author (Andreas Citation 2019). In the UK, themes such as transformation, innovation, ... Such research, using a political economy analysis framework, might include: international comparison of construction sectors. comparison with other sectors of industry.

The basic idea is for you to apply a theory or small set of theories to an issue in international political economy to drive predictions regarding the likely course of events over the next 5-10 or 10- 20 years. ... Research Paper Topic: You will write a short paragraph outlining the general topic of your research paper. General topics include ...