- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section New Historicism

Introduction, general overviews.

- Essay Collections

- Theoretical Influences

- Scholarly Influences

- Book-Length Studies

- Feminist Studies

- New New Historicism, or New Materialism

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Jonathan Goldberg

- Michel de Certeau

- Michel Foucault

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Black Atlantic

- Friedrich Schleiermacher

- Postcolonialism and Digital Humanities

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

New Historicism by Neema Parvini LAST REVIEWED: 26 July 2017 LAST MODIFIED: 26 July 2017 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780190221911-0015

New historicism has been a hugely influential approach to literature, especially in studies of William Shakespeare’s works and literature of the Early Modern period. It began in earnest in 1980 and quickly supplanted New Criticism as the new orthodoxy in early modern studies. Despite many attacks from feminists, cultural materialists, and traditional scholars, it dominated the study of early modern literature in the 1980s and 1990s. Arguably, since then, it has given way to a different, more materialist, form of historicism that some call “new new historicism.” There have also been variants of “new historicism” in other periods of the discipline, most notably the romantic period, but its stronghold has always remained in the Renaissance. At its core, new historicism insists—contra formalism—that literature must be understood in its historical context. This is because it views literary texts as cultural products that are rooted in their time and place, not works of individual genius that transcend them. New-historicist essays are thus often marked by making seemingly unlikely linkages between various cultural products and literary texts. Its “newness” is at once an echo of the New Criticism it replaced and a recognition of an “old” historicism, often exemplified by E. M. W. Tillyard, against which it defines itself. In its earliest iteration, new historicism was primarily a method of power analysis strongly influenced by the anthropological studies of Clifford Geertz, modes of torture and punishment described by Michel Foucault, and methods of ideological control outlined by Louis Althusser. This can be seen most visibly in new-historicist work of the early 1980s. These works came to view the Tudor and early Stuart states as being almost insurmountable absolutist monarchies in which the scope of individual agency or political subversion appeared remote. This version of new historicism is frequently, and erroneously, taken to represent its entire enterprise. Stephen Greenblatt argued that power often produces its own subversive elements in order to contain it—and so what appears to be subversion is actually the final victory of containment. This became known as the hard version of the containment thesis, and it was attacked and critiqued by many commentators as leaving too-little room for the possibility of real change or agency. This was the major departure point of the cultural materialists, who sought a more dynamic model of culture that afforded greater opportunities for dissidence. Later new-historicist studies sought to complicate the hard version of the containment thesis to facilitate a more flexible, heterogeneous, and dynamic view of culture.

Owing to its success, there has been no shortage of textbooks and anthology entries on new historicism, but it has often had to share space with British cultural materialism, a school that, though related, has an entirely distinct theoretical and methodological genesis. The consequence of this dual treatment has resulted in a somewhat caricatured view of both approaches along the axis of subversion and containment, with new historicism representing the latter. While there is some truth to this shorthand account, any sustained engagement with new-historicist studies will reveal its limitations. Readers should be aware, therefore, that while accounts that contrast new historicism with cultural materialism—for example, Dollimore 1990 , Wilson 1992 , and Brannigan 1998 —can be illuminating, they can also by the terms of that contrast tend to oversimplify. Be aware also that because new historicism has been a controversial development in the field, accounts are seldom entirely neutral. Mullaney 1996 , for example, was written by a new historicist, while Parvini 2012 was written by an author who has been strongly critical of the approach.

Brannigan, John. New Historicism and Cultural Materialism . Transitions. New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-349-26622-7

Introduction to new historicism and cultural materialism aimed at the general reader and student, which does much to elucidate the differences between those two schools. In doing so, however, it is perhaps guilty of oversimplification, especially as regards the new historicists, who, according to Brannigan, never progress beyond the hard version of the containment thesis.

Dollimore, Jonathan. “Critical Developments: Cultural Materialism, Feminism and Gender Critique, and New Historicism.” In Shakespeare: A Bibliographical Guide . New ed. Edited by Stanley Wells, 405–428. Oxford: Clarendon, 1990.

A cultural-materialist take on “critical developments” over the decade of the 1980s that elaborates on the differences between new historicism and cultural materialism. Useful document of its time, but be aware of identifying new historicists too closely with the containment thesis it outlines, which became softer and more nuanced in later new-historicist work.

Hamilton, Paul. Historicism . New Critical Idiom. New York: Routledge, 1996.

DOI: 10.4324/9780203426289

Guide to wider tradition of historicism from ancient Greece to the late 20th century. Chapters on Michel Foucault and new historicism usefully view both subjects through this wider lens, although some of the nuances (for example, the differences between new historicism and cultural materialism) are lost along the way. See especially pp. 115–150.

Harris, Jonathan Gil. “New Historicism and Cultural Materialism: Michel Foucault, Stephen Greenblatt, Alan Sinfield.” In Shakespeare and Literary Theory . By Jonathan Gil Harris, 175–192. Oxford Shakespeare Topics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Structured into three parts: the first on Foucault, the second on Greenblatt’s “Invisible Bullets” (see Greenblatt 1988 , cited under Essays ), and the third on the cultural materialist Sinfield. Concise, if cursory, overview. Its focus on practice rather than theory renders it too specific to serve as a lone entry point, but useful introductory material if considered alongside other accounts.

Mullaney, Steven. “After the New Historicism.” In Alternative Shakespeares . Vol. 2. Edited by Terence Hawkes, 17–37. New Accents. New York and London: Routledge, 1996.

By its own admission a “partisan account” (p. 21) of new-historicist practice by one of its own foremost practitioners. Argues that the view of new historicism become distorted through oversimplification. Reminds us of the extent of new historicism’s theoretical and methodological innovations, which detractors “sometimes fail to acknowledge” (p. 28).

Parvini, Neema. Shakespeare and Contemporary Theory: New Historicism and Cultural Materialism . New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2012.

DOI: 10.5040/9781472555113

More comprehensive in coverage than other available guides, perhaps owing to its more recent publication. Features a timeline of critical developments, a “Who’s Who” in new historicism and cultural materialism, and a glossary of theoretical terms. Includes sections on Clifford Geertz and Michel Foucault and offers clear distinctions between early new-historicist work and “cultural poetics.”

Robson, Mark. Stephen Greenblatt . Routledge Critical Thinkers. New York and London: Routledge, 2007.

Although centered on Greenblatt, this book effectively doubles as an introduction to new historicism and its concepts. Lucidly written, it features some incisive analysis and a comprehensive reading list to direct further study.

Wilson, Richard. “Introduction: Historicising New Historicism.” In New Historicism and Renaissance Drama . Edited by Richard Wilson and Richard Dutton, 1–18. Longman Critical Readers. New York and London: Longman, 1992.

Gains from being very theoretically well informed. Argues that new historicism is best understood, ironically, if historicized in the context of Ronald Reagan’s America and the final years of the Cold War. An excellent entry point to understanding new historicism and its concerns. A section contrasting cultural materialism with new historicism closes the piece.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Literary and Critical Theory »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Achebe, Chinua

- Adorno, Theodor

- Aesthetics, Post-Soul

- Affect Studies

- Afrofuturism

- Agamben, Giorgio

- Anzaldúa, Gloria E.

- Apel, Karl-Otto

- Appadurai, Arjun

- Badiou, Alain

- Baudrillard, Jean

- Belsey, Catherine

- Benjamin, Walter

- Bettelheim, Bruno

- Bhabha, Homi K.

- Biopower, Biopolitics and

- Blanchot, Maurice

- Bloom, Harold

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Brecht, Bertolt

- Brooks, Cleanth

- Caputo, John D.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh

- Conversation Analysis

- Cosmopolitanism

- Creolization/Créolité

- Crip Theory

- Critical Theory

- Cultural Materialism

- de Certeau, Michel

- de Man, Paul

- de Saussure, Ferdinand

- Deconstruction

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Derrida, Jacques

- Dollimore, Jonathan

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Eagleton, Terry

- Eco, Umberto

- Ecocriticism

- English Colonial Discourse and India

- Environmental Ethics

- Fanon, Frantz

- Feminism, Transnational

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Freud, Sigmund

- Frye, Northrop

- Genet, Jean

- Girard, René

- Global South

- Goldberg, Jonathan

- Gramsci, Antonio

- Greimas, Algirdas Julien

- Grief and Comparative Literature

- Guattari, Félix

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Haraway, Donna J.

- Hartman, Geoffrey

- Hawkes, Terence

- Hemispheric Studies

- Hermeneutics

- Hillis-Miller, J.

- Holocaust Literature

- Human Rights and Literature

- Humanitarian Fiction

- Hutcheon, Linda

- Žižek, Slavoj

- Imperial Masculinity

- Irigaray, Luce

- Jameson, Fredric

- JanMohamed, Abdul R.

- Johnson, Barbara

- Kagame, Alexis

- Kolodny, Annette

- Kristeva, Julia

- Lacan, Jacques

- Laclau, Ernesto

- Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe

- Laplanche, Jean

- Leavis, F. R.

- Levinas, Emmanuel

- Levi-Strauss, Claude

- Literature, Dalit

- Lonergan, Bernard

- Lotman, Jurij

- Lukács, Georg

- Lyotard, Jean-François

- Metz, Christian

- Morrison, Toni

- Mouffe, Chantal

- Nancy, Jean-Luc

- Neo-Slave Narratives

- New Historicism

- New Materialism

- Partition Literature

- Peirce, Charles Sanders

- Philosophy of Theater, The

- Postcolonial Theory

- Posthumanism

- Postmodernism

- Post-Structuralism

- Psychoanalytic Theory

- Queer Medieval

- Race and Disability

- Rancière, Jacques

- Ransom, John Crowe

- Reader Response Theory

- Rich, Adrienne

- Richards, I. A.

- Ronell, Avital

- Rosenblatt, Louse

- Said, Edward

- Settler Colonialism

- Socialist/Marxist Feminism

- Stiegler, Bernard

- Structuralism

- Theatre of the Absurd

- Thing Theory

- Tolstoy, Leo

- Tomashevsky, Boris

- Translation

- Transnationalism in Postcolonial and Subaltern Studies

- Virilio, Paul

- Warren, Robert Penn

- White, Hayden

- Wittig, Monique

- World Literature

- Zimmerman, Bonnie

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.7: New Historicism

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40496

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The Relationship Between History and Literature

Early scholars of literature thought of history as a progression: events and ideas built on each other in a linear and causal way. History, consequently, could be understood objectively, as a series of dates, people, facts, and events. Once known, history became a static entity. We can see this in the previous example from Wonderland . The Mouse notes that the "driest thing" he knows is that "William the Conqueror, whose cause was favoured by the pope, was soon submitted to by the English, who wanted leaders, and had been of late much accustomed to usurpation and conquest. Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria—" I think we would all agree to moan "Ugh!" In other words, the Mouse sees history as a list of great dead people that must be remembered and recited, a list that refers only to the so-called great events of history: battles, rebellions, and the rise and fall of leaders. Corresponding to this view, literature was thought to directly or indirectly mirror historical reality. Scholars believed that history shaped literature, but literature didn't shape history.

While this view of history as a static amalgamation of facts is still considered important, other scholars in the movement called New Historicism see the relationship between history and literature quite differently. Today, most literary scholars think of history as a dynamic interplay of cultural, economic, artistic, religious, political, and social forces. They don't necessarily concentrate solely on kings and nobles, or battles and coronations. In addition, they also focus on the smaller details of history, including the plight of the common person, popular songs and art, periodicals and advertisements — and, of course, literature. New Historical scholarship, it follows, is interdisciplinary , drawing on materials from a number of academic fields that were once thought to be separate or distinct from one another: history, religious studies, political science, sociology, psychology, philosophy, and even the natural sciences. In fact, New Historicism is also called cultural materialism since a text—whether it’s a piece of literature, a religious tract, a political polemic, or a scientific discovery—is seen as an artifact of history, a material entity that reflects larger cultural issues.

Exercise 10.7.1

How have you learned to connect literature and history? Jot down two or three examples from previous classes.

History Influences Literature

Sometimes it's obvious the way history can help us understand a piece of literature. When reading William Butler Yeats’s poem “ Easter, 1916 ,” for instance, readers immediately wonder how the date named in the poem's title shapes the poem's meaning. Curious readers might quickly look up that Easter date and discover that leaders of the Irish independence movement staged a short-lived revolt against British rule during Easter week in 1916. The rebellion was quickly ended by British forces, and the rebel leaders were tried and executed. Those curious readers might then understand the allusions that Yeats makes to each of the executed Irish leaders in his poem and gain a better sense of what Yeats hopes to convey about Ireland's past and future through his poem's symbols and language. Many writers, like Yeats, use their art to directly address social, political, military, or economic debates in their cultures. These writers enter into the social discourse of their time, this discourse being formed by the cultural conditions that define the age. Furthermore, this discourse reflects the ideology of the society at the time, which is the collective ideas—including political, economic, and religious ideas—that guide the way a culture views and talks about itself. This cultural ideology, in turn, reflects the power structures that control—or attempt to control—the discourse of a society and often control the way literature is published, read, and interpreted. Literature, then, as a societal discourse comments on and is influenced by the other cultural discourses, which reflect or resist the ideology that is based on the power structures of society.

Literature Influences History

Let's turn to another example to illuminate these issues. One of the most influential books in American history was Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), which Stowe wrote to protest slavery in the South before the Civil War. Uncle Tom's Cabin was an instant bestseller that did much to popularize the abolitionist movement in the northern United States. Legend has it that when Abraham Lincoln met Stowe during the Civil War, he greeted her by saying, "So you're the little woman that wrote the book that started this great war." In the case of Uncle Tom's Cabin , then, it's clear that understanding the histories of slavery, abolitionism, and antebellum regional tensions can help us make sense of Stowe's novel.

But history informs literature in less direct ways, as well. In fact, many literary scholars—in particular, New Historical scholars—would insist that every work of literature, whether it explicitly mentions a historical event or not, is shaped by the moment of its composition (and that works of literature shape their moment of composition in turn). The American history of the Vietnam war is a great example, for we continue to interpret and revise that history, and literature (including memoirs) is a key material product that influences that revision: think of Michael Herr's Dispatches (1977); Philip Caputo's A Rumor of War (1977); Bobbie Anne Mason's In Country (1985); Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried (1990); Robert Olen Butler's A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992); and, most recently, Karl Marlantes's Matterhorn (2010) (Michael Herr, Dispatches (New York: Vintage, 1977); Philip Carputo, A Rumor of War (New York: Ballantine, 1977); Bobbie Anne Mason, In Country (New York: HarperCollins, 2005); Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried (New York: Mariner, 2009); Robert Olen Butler, A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain: Stories (New York: Holt, 1992); Karl Marlantes, Matterhorn (New York: Atlantic Monthly, 2010)).

Exercise 10.7.2

Pick something you've read or watched recently. It doesn't matter what you choose: Dear White People , the Harry Potter series, Twilight , The Hunger Games , even Jersey Shore or American Idol . Now reflect on what that book, movie, or television show tells you about your culture. What discourses or ideologies (values, priorities, concerns) does your cultural artifact reveal? Jot down your thoughts.

New Historicism Practice

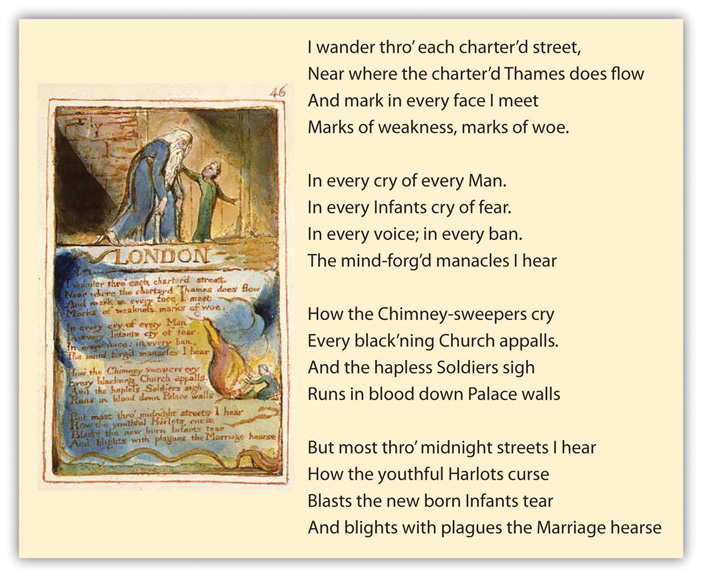

As you can see, authors influence their cultures and they, in turn, are influenced by the social, political, military, and economic concerns of their cultures. To review the connection between literature and history, let's look at one final example, " London ", written by the poet William Blake in 1794.

Illustration by William Blake for "London" from his Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794).

Unlike Yeats or Stowe, Blake does not refer directly to specific events or people from the late eighteenth century. Yet this poem directly confronts many of the most pressing social issues of Blake's day. The first stanza, for example, refers to the "charter'd streets" and "charter'd Thames." If we look up the meaning of the word "charter," we find that the word has several meanings. " Charter " can refer to a deed or a contract. When Blake refers to "charter'd" streets, he might be alluding to the growing importance of London as a center of industry and commerce. A "charter" also defines boundaries and control. When Blake refers to "charter'd Thames," then, he implies that nature—the Thames is the river that runs through London—has been constricted by modern society. If you look through the rest of the poem, you can see many other historical issues that a scholar might be interested in exploring: the plight of child laborers ("the Chimney-sweepers cry"); the role of the Church ("Every black'ning Church"), the monarchy ("down Palace walls"), or the military ("the hapless Soldiers sigh") in English society; or even the problem of sexually transmitted disease ("blights with plagues the Marriage hearse"). You will also notice that Blake provided an etching for this poem and the poems that compose The Songs of Innocence (1789) and The Songs of Experience (in which "London" was published), so Blake is also engaging in the artistic movement of his day and the very production of bookmaking itself. And we would be remiss if we did not mention that Blake wrote these poems during the French Revolution (1789–99), where he initially hoped that the revolution would bring freedom to all individuals but soon recognized the brutality of the movement. That's a lot to ask of a sixteen-line poem! But each of these topics is ripe for further investigation that might lead to an engaging critical paper.

When scholars dig into one historical aspect of a literary work, we call that process parallel reading . Parallel reading involves examining the literary text in light of other contemporary texts: newspaper articles, religious pamphlets, economic reports, political documents, and so on. These different types of texts, considered equally, help scholars construct a richer understanding of history. Scholars learn not only what happened but also how people understood what happened. By reading historical and literary texts in parallel, scholars create, to use a phrase from anthropology, a thick description that centers the literary text as both a product and a contributor to its historical moment. A story might respond to a particular historical reality, for example, and then the story might help shape society’s attitude toward that reality, as Uncle Tom's Cabin sparked a national movement to abolish slavery in the United States.

Apply New Historicism To Your Reading

When reading a work through a New Historicism reading, apply the following steps:

- Determine the time and place, or historical context of the literature.

- Choose a specific aspect of the text you feel would be illuminated by learning more about the history of the text.

- Research the history.

- Analyze the ways in which the text may be influenced by its history or the text may have influenced the culture of the time.

Apply New Historicism To Your Writing

To review, New Historicism provides us with a particular lens to use when we read and interpret works of literature. Such reading and interpreting, however, never happens after just a first reading; in fact, all critics reread works multiple times before venturing an interpretation. You can see, then, the connection between reading and writing: as Chapter 1 indicates, writers create multiple drafts before settling for a finished product. The writing process, in turn, is dependent on the multiple rereadings you have performed to gather evidence for your essay. It's important that you integrate the reading and writing process together. As a model, use the following ten-step plan as you write using a new historical approach:

- Carefully read the work you will analyze.

- Formulate a general question after your initial reading that identifies a problem—a tension—related to a historical or cultural issue.

- Reread the work , paying particular attention to the question you posed. Take notes, which should be focused on your central question. Write an exploratory journal entry or blog post that allows you to play with ideas.

- What does the work mean?

- How does the work demonstrate the theme you've identified using a new historical approach?

- "So what" is significant about the work? That is, why is it important for you to write about this work? What will readers learn from reading your interpretation? How does the theory you apply illuminate the work's meaning?

- Reread the text to gather textual evidence for support.

- Construct an informal outline that demonstrates how you will support your interpretation.

- Write a first draft.

- Receive feedback from peers and your instructor via peer review and conferencing with your instructor (if possible).

- Revise the paper , which will include revising your original thesis statement and restructuring your paper to best support the thesis. Note: You probably will revise many times, so it is important to receive feedback at every draft stage if possible.

- Edit and proofread for correctness, clarity, and style.

We recommend that you follow this process for every paper that you write from this textbook. Of course, these steps can be modified to fit your writing process, but the plan does ensure that you will engage in a thorough reading of the text as you work through the writing process, which demands that you allow plenty of time for reading, reflecting, writing, reviewing, and revising.

For more strategies, read on here .

Contributors and Attributions

- Adapted from "New Historical Criticism: An Overview" from Creating Literary Analysis by Ryan Cordell and John Pennington, licensed CC BY NC-SA 4.0

Open Yale Courses

You are here, engl 300: introduction to theory of literature, - the new historicism.

In this lecture, Professor Paul Fry examines the work of two seminal New Historicists, Stephen Greenblatt and Jerome McGann. The origins of New Historicism in Early Modern literary studies are explored, and New Historicism’s common strategies, preferred evidence, and literary sites are explored. Greenblatt’s reliance on Foucault is juxtaposed with McGann’s use of Bakhtin. The lecture concludes with an extensive consideration of the project of editing of Keats’s poetry in light of New Historicist concerns.

Lecture Chapters

- Origins of New Historicism

- The New Historicist Method and Foucault

- The Reciprocal Relationship Between History and Discourse

- The Historian and Subjectivity

- Jerome McGann and Bakhtin

- McGann on Keats

- Tony the Tow Truck Revisited

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

27 Practicing New Historicism and Cultural Studies

For our New Historicism and cultural studies theoretical response, we will take a slightly different approach compared with previous chapters. Everyone will read an excerpt from The Great Gatsby (1925) by F. Scott Fitzgerald and review four film trailers and reviews below. You’ll then choose between two options to complete your theoretical response. Note that in both cases, your theoretical response will be slightly longer (750-1000 words) this week because you’ll need to integrate multiple sources.

Option One: New Historicism

Using the artifacts listed below, apply the techniques of New Historicism to explore how these texts exist and interact within their contexts. Here are the four required artifacts:

- Excerpt from The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

- “Lament for Dark Peoples” by Langston Hughes (1926)

- The 1926 film trailer for The Great Gatsby (below)

- The 1926 New York Times film review for The Great Gatsby (note: you will need to use your free student account to access this article).

You may also want to do some brief research about the historical conditions of 1925-1926 in the United States. Focus on the artifacts as evidence of their historical contexts. Your response should be 750-1000 words and include a brief thesis statement that reflects your critical approach.

Here are some questions to consider as you write your response:

- What do we need to know about F. Scott Fitzgerald to understand The Great Gatsby as a cultural artifact? What do we need to know about Langston Hughes? And how does purely biographical criticism differ from a New Historicism approach?

- What are some of the main historical events that occurred in the period when the book, poem, and film were created? Do you see these historical events reflected in these three artifacts?

- How might this historical context shape the creation of these three cultural artifacts? How does the 1926 film review affect your understanding of this context?

- Do we see congruity in messaging around social norms in these three artifacts? What are those social norms? Are there any missing or excluded voices in these artifacts? If so, why?

- What other artifacts might you consider if you wanted to learn more or confirm your theories about the historical context for these three artifacts? For example, what kinds of advertisements would you expect to see in this issue of the New York Times ?

- How do we view these artifacts and their societal/cultural norms from our modern perspective? In other words, have our cultural/societal norms remained stable in the 60 years since these cultural artifacts were published? If not, what significant changes have occurred?

Option Two: Cultural Studies

Film and media studies are common cultural studies approaches. For this option, you’ll have more choice over your artifacts, and you’ll be considering the text and the film artifacts as examples of the cultures that produced them. You’ll need to use the following artifact:

Then choose any two film trailers and reviews from the 1949, 1974, and 2013 versions linked below.

In addition to considering the historical and cultural context of the novel, you should also do some brief historical research about the two film years that you choose. Focus on the artifacts as evidence of the culture that produced and received them, and consider how and why that reception has changed over time. Your response should be 750-1000 words and include a brief thesis statement that reflects your critical approach.

- What do we need to know about F. Scott Fitzgerald to understand The Great Gatsby as a cultural artifact? What did “popular culture” look like in the mid 1920s in the United States?

- What cultural norms do you see reflected in the two film adaptations you chose? How do the cultural norms when these movies were made compare with the cultural norms in the novel excerpt?

- How do the film reviews affect your understanding of this cultural context?

- How have social norms and the messaging around them changed in these three artifacts? What are those social norms? Are there any missing or excluded voices in these artifacts? If so, why?

- What other artifacts might you consider if you wanted to learn more or confirm your theories about societal and cultural norms in these three artifacts? For example, what kinds of advertisements would you expect to see in this issue of the New York Times ?

- How do we view these artifacts and their societal/cultural norms from our modern perspective? Have our views changed since these cultural artifacts were published? (This may be an especially interesting question if you choose the 2013 version).

Post your short essay (using either option one or option two) to the New Historicism/Cultural Studies Theoretical Response discussion board. Please include the option you have chosen in your post title. I have included the theoretical response assignment instructions at the end of this chapter.

Excerpt from “The Great Gatsby” (1925)

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

I believe that on the first night I went to Gatsby’s house I was one of the few guests who had actually been invited. People were not invited—they went there. They got into automobiles which bore them out to Long Island, and somehow they ended up at Gatsby’s door. Once there they were introduced by somebody who knew Gatsby, and after that they conducted themselves according to the rules of behaviour associated with an amusement park. Sometimes they came and went without having met Gatsby at all, came for the party with a simplicity of heart that was its own ticket of admission. I had been actually invited. A chauffeur in a uniform of robin’s-egg blue crossed my lawn early that Saturday morning with a surprisingly formal note from his employer: the honour would be entirely Gatsby’s, it said, if I would attend his “little party” that night. He had seen me several times, and had intended to call on me long before, but a peculiar combination of circumstances had prevented it—signed Jay Gatsby, in a majestic hand. Dressed up in white flannels I went over to his lawn a little after seven, and wandered around rather ill at ease among swirls and eddies of people I didn’t know—though here and there was a face I had noticed on the commuting train. I was immediately struck by the number of young Englishmen dotted about; all well dressed, all looking a little hungry, and all talking in low, earnest voices to solid and prosperous Americans. I was sure that they were selling something: bonds or insurance or automobiles. They were at least agonizingly aware of the easy money in the vicinity and convinced that it was theirs for a few words in the right key. As soon as I arrived I made an attempt to find my host, but the two or three people of whom I asked his whereabouts stared at me in such an amazed way, and denied so vehemently any knowledge of his movements, that I slunk off in the direction of the cocktail table—the only place in the garden where a single man could linger without looking purposeless and alone. I was on my way to get roaring drunk from sheer embarrassment when Jordan Baker came out of the house and stood at the head of the marble steps, leaning a little backward and looking with contemptuous interest down into the garden. Welcome or not, I found it necessary to attach myself to someone before I should begin to address cordial remarks to the passersby. “Hello!” I roared, advancing toward her. My voice seemed unnaturally loud across the garden. “I thought you might be here,” she responded absently as I came up. “I remembered you lived next door to—” She held my hand impersonally, as a promise that she’d take care of me in a minute, and gave ear to two girls in twin yellow dresses, who stopped at the foot of the steps. “Hello!” they cried together. “Sorry you didn’t win.” That was for the golf tournament. She had lost in the finals the week before. “You don’t know who we are,” said one of the girls in yellow, “but we met you here about a month ago.” “You’ve dyed your hair since then,” remarked Jordan, and I started, but the girls had moved casually on and her remark was addressed to the premature moon, produced like the supper, no doubt, out of a caterer’s basket. With Jordan’s slender golden arm resting in mine, we descended the steps and sauntered about the garden. A tray of cocktails floated at us through the twilight, and we sat down at a table with the two girls in yellow and three men, each one introduced to us as Mr. Mumble. “Do you come to these parties often?” inquired Jordan of the girl beside her. “The last one was the one I met you at,” answered the girl, in an alert confident voice. She turned to her companion: “Wasn’t it for you, Lucille?” It was for Lucille, too. “I like to come,” Lucille said. “I never care what I do, so I always have a good time. When I was here last I tore my gown on a chair, and he asked me my name and address—inside of a week I got a package from Croirier’s with a new evening gown in it.” “Did you keep it?” asked Jordan. “Sure I did. I was going to wear it tonight, but it was too big in the bust and had to be altered. It was gas blue with lavender beads. Two hundred and sixty-five dollars.” “There’s something funny about a fellow that’ll do a thing like that,” said the other girl eagerly. “He doesn’t want any trouble with any body.” “Who doesn’t?” I inquired. “Gatsby. Somebody told me—” The two girls and Jordan leaned together confidentially. “Somebody told me they thought he killed a man once.” A thrill passed over all of us. The three Mr. Mumbles bent forward and listened eagerly. “I don’t think it’s so much that ,” argued Lucille sceptically; “It’s more that he was a German spy during the war.” One of the men nodded in confirmation. “I heard that from a man who knew all about him, grew up with him in Germany,” he assured us positively. “Oh, no,” said the first girl, “it couldn’t be that, because he was in the American army during the war.” As our credulity switched back to her she leaned forward with enthusiasm. “You look at him sometimes when he thinks nobody’s looking at him. I’ll bet he killed a man.” She narrowed her eyes and shivered. Lucille shivered. We all turned and looked around for Gatsby. It was testimony to the romantic speculation he inspired that there were whispers about him from those who had found little that it was necessary to whisper about in this world. The first supper—there would be another one after midnight—was now being served, and Jordan invited me to join her own party, who were spread around a table on the other side of the garden. There were three married couples and Jordan’s escort, a persistent undergraduate given to violent innuendo, and obviously under the impression that sooner or later Jordan was going to yield him up her person to a greater or lesser degree. Instead of rambling, this party had preserved a dignified homogeneity, and assumed to itself the function of representing the staid nobility of the countryside—East Egg condescending to West Egg and carefully on guard against its spectroscopic gaiety. “Let’s get out,” whispered Jordan, after a somehow wasteful and inappropriate half-hour; “this is much too polite for me.” We got up, and she explained that we were going to find the host: I had never met him, she said, and it was making me uneasy. The undergraduate nodded in a cynical, melancholy way. The bar, where we glanced first, was crowded, but Gatsby was not there. She couldn’t find him from the top of the steps, and he wasn’t on the veranda. On a chance we tried an important-looking door, and walked into a high Gothic library, panelled with carved English oak, and probably transported complete from some ruin overseas. A stout, middle-aged man, with enormous owl-eyed spectacles, was sitting somewhat drunk on the edge of a great table, staring with unsteady concentration at the shelves of books. As we entered he wheeled excitedly around and examined Jordan from head to foot. “What do you think?” he demanded impetuously. “About what?” He waved his hand toward the bookshelves. “About that. As a matter of fact you needn’t bother to ascertain. I ascertained. They’re real.” “The books?” He nodded. “Absolutely real—have pages and everything. I thought they’d be a nice durable cardboard. Matter of fact, they’re absolutely real. Pages and—Here! Lemme show you.” Taking our scepticism for granted, he rushed to the bookcases and returned with Volume One of the Stoddard Lectures . “See!” he cried triumphantly. “It’s a bona-fide piece of printed matter. It fooled me. This fella’s a regular Belasco. It’s a triumph. What thoroughness! What realism! Knew when to stop, too—didn’t cut the pages. But what do you want? What do you expect?” He snatched the book from me and replaced it hastily on its shelf, muttering that if one brick was removed the whole library was liable to collapse. “Who brought you?” he demanded. “Or did you just come? I was brought. Most people were brought.” Jordan looked at him alertly, cheerfully, without answering. “I was brought by a woman named Roosevelt,” he continued. “Mrs. Claud Roosevelt. Do you know her? I met her somewhere last night. I’ve been drunk for about a week now, and I thought it might sober me up to sit in a library.” “Has it?” “A little bit, I think. I can’t tell yet. I’ve only been here an hour. Did I tell you about the books? They’re real. They’re—” “You told us.” We shook hands with him gravely and went back outdoors. There was dancing now on the canvas in the garden; old men pushing young girls backward in eternal graceless circles, superior couples holding each other tortuously, fashionably, and keeping in the corners—and a great number of single girls dancing individually or relieving the orchestra for a moment of the burden of the banjo or the traps. By midnight the hilarity had increased. A celebrated tenor had sung in Italian, and a notorious contralto had sung in jazz, and between the numbers people were doing “stunts” all over the garden, while happy, vacuous bursts of laughter rose toward the summer sky. A pair of stage twins, who turned out to be the girls in yellow, did a baby act in costume, and champagne was served in glasses bigger than finger-bowls. The moon had risen higher, and floating in the Sound was a triangle of silver scales, trembling a little to the stiff, tinny drip of the banjoes on the lawn. I was still with Jordan Baker. We were sitting at a table with a man of about my age and a rowdy little girl, who gave way upon the slightest provocation to uncontrollable laughter. I was enjoying myself now. I had taken two finger-bowls of champagne, and the scene had changed before my eyes into something significant, elemental, and profound. At a lull in the entertainment the man looked at me and smiled. “Your face is familiar,” he said politely. “Weren’t you in the First Division during the war?” “Why yes. I was in the Twenty-eighth Infantry.” “I was in the Sixteenth until June nineteen-eighteen. I knew I’d seen you somewhere before.” We talked for a moment about some wet, grey little villages in France. Evidently he lived in this vicinity, for he told me that he had just bought a hydroplane, and was going to try it out in the morning. “Want to go with me, old sport? Just near the shore along the Sound.” “What time?” “Any time that suits you best.” It was on the tip of my tongue to ask his name when Jordan looked around and smiled. “Having a gay time now?” she inquired. “Much better.” I turned again to my new acquaintance. “This is an unusual party for me. I haven’t even seen the host. I live over there—” I waved my hand at the invisible hedge in the distance, “and this man Gatsby sent over his chauffeur with an invitation.” For a moment he looked at me as if he failed to understand. “I’m Gatsby,” he said suddenly. “What!” I exclaimed. “Oh, I beg your pardon.” “I thought you knew, old sport. I’m afraid I’m not a very good host.” He smiled understandingly—much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced—or seemed to face—the whole eternal world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favour. It understood you just so far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself, and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey. Precisely at that point it vanished—and I was looking at an elegant young roughneck, a year or two over thirty, whose elaborate formality of speech just missed being absurd. Some time before he introduced himself I’d got a strong impression that he was picking his words with care. Almost at the moment when Mr. Gatsby identified himself a butler hurried toward him with the information that Chicago was calling him on the wire. He excused himself with a small bow that included each of us in turn. “If you want anything just ask for it, old sport,” he urged me. “Excuse me. I will rejoin you later.” When he was gone I turned immediately to Jordan—constrained to assure her of my surprise. I had expected that Mr. Gatsby would be a florid and corpulent person in his middle years. “Who is he?” I demanded. “Do you know?” “He’s just a man named Gatsby.” “Where is he from, I mean? And what does he do?” “Now you ’re started on the subject,” she answered with a wan smile. “Well, he told me once he was an Oxford man.” A dim background started to take shape behind him, but at her next remark it faded away. “However, I don’t believe it.” “Why not?” “I don’t know,” she insisted, “I just don’t think he went there.” Something in her tone reminded me of the other girl’s “I think he killed a man,” and had the effect of stimulating my curiosity. I would have accepted without question the information that Gatsby sprang from the swamps of Louisiana or from the lower East Side of New York. That was comprehensible. But young men didn’t—at least in my provincial inexperience I believed they didn’t—drift coolly out of nowhere and buy a palace on Long Island Sound. “Anyhow, he gives large parties,” said Jordan, changing the subject with an urban distaste for the concrete. “And I like large parties. They’re so intimate. At small parties there isn’t any privacy.” There was the boom of a bass drum, and the voice of the orchestra leader rang out suddenly above the echolalia of the garden. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he cried. “At the request of Mr. Gatsby we are going to play for you Mr. Vladmir Tostoff’s latest work, which attracted so much attention at Carnegie Hall last May. If you read the papers you know there was a big sensation.” He smiled with jovial condescension, and added: “Some sensation!” Whereupon everybody laughed. “The piece is known,” he concluded lustily, “as ‘Vladmir Tostoff’s Jazz History of the World!’ ” The nature of Mr. Tostoff’s composition eluded me, because just as it began my eyes fell on Gatsby, standing alone on the marble steps and looking from one group to another with approving eyes. His tanned skin was drawn attractively tight on his face and his short hair looked as though it were trimmed every day. I could see nothing sinister about him. I wondered if the fact that he was not drinking helped to set him off from his guests, for it seemed to me that he grew more correct as the fraternal hilarity increased. When the “Jazz History of the World” was over, girls were putting their heads on men’s shoulders in a puppyish, convivial way, girls were swooning backward playfully into men’s arms, even into groups, knowing that someone would arrest their falls—but no one swooned backward on Gatsby, and no French bob touched Gatsby’s shoulder, and no singing quartets were formed with Gatsby’s head for one link. “I beg your pardon.” Gatsby’s butler was suddenly standing beside us. “Miss Baker?” he inquired. “I beg your pardon, but Mr. Gatsby would like to speak to you alone.” “With me?” she exclaimed in surprise. “Yes, madame.” She got up slowly, raising her eyebrows at me in astonishment, and followed the butler toward the house. I noticed that she wore her evening-dress, all her dresses, like sports clothes—there was a jauntiness about her movements as if she had first learned to walk upon golf courses on clean, crisp mornings. I was alone and it was almost two. For some time confused and intriguing sounds had issued from a long, many-windowed room which overhung the terrace. Eluding Jordan’s undergraduate, who was now engaged in an obstetrical conversation with two chorus girls, and who implored me to join him, I went inside. The large room was full of people. One of the girls in yellow was playing the piano, and beside her stood a tall, red-haired young lady from a famous chorus, engaged in song. She had drunk a quantity of champagne, and during the course of her song she had decided, ineptly, that everything was very, very sad—she was not only singing, she was weeping too. Whenever there was a pause in the song she filled it with gasping, broken sobs, and then took up the lyric again in a quavering soprano. The tears coursed down her cheeks—not freely, however, for when they came into contact with her heavily beaded eyelashes they assumed an inky colour, and pursued the rest of their way in slow black rivulets. A humorous suggestion was made that she sing the notes on her face, whereupon she threw up her hands, sank into a chair, and went off into a deep vinous sleep. “She had a fight with a man who says he’s her husband,” explained a girl at my elbow. I looked around. Most of the remaining women were now having fights with men said to be their husbands. Even Jordan’s party, the quartet from East Egg, were rent asunder by dissension. One of the men was talking with curious intensity to a young actress, and his wife, after attempting to laugh at the situation in a dignified and indifferent way, broke down entirely and resorted to flank attacks—at intervals she appeared suddenly at his side like an angry diamond, and hissed: “You promised!” into his ear. The reluctance to go home was not confined to wayward men. The hall was at present occupied by two deplorably sober men and their highly indignant wives. The wives were sympathizing with each other in slightly raised voices. “Whenever he sees I’m having a good time he wants to go home.” “Never heard anything so selfish in my life.” “We’re always the first ones to leave.” “So are we.” “Well, we’re almost the last tonight,” said one of the men sheepishly. “The orchestra left half an hour ago.” In spite of the wives’ agreement that such malevolence was beyond credibility, the dispute ended in a short struggle, and both wives were lifted, kicking, into the night. As I waited for my hat in the hall the door of the library opened and Jordan Baker and Gatsby came out together. He was saying some last word to her, but the eagerness in his manner tightened abruptly into formality as several people approached him to say goodbye. Jordan’s party were calling impatiently to her from the porch, but she lingered for a moment to shake hands. “I’ve just heard the most amazing thing,” she whispered. “How long were we in there?” “Why, about an hour.” “It was… simply amazing,” she repeated abstractedly. “But I swore I wouldn’t tell it and here I am tantalizing you.” She yawned gracefully in my face. “Please come and see me… Phone book… Under the name of Mrs. Sigourney Howard… My aunt…” She was hurrying off as she talked—her brown hand waved a jaunty salute as she melted into her party at the door. Rather ashamed that on my first appearance I had stayed so late, I joined the last of Gatsby’s guests, who were clustered around him. I wanted to explain that I’d hunted for him early in the evening and to apologize for not having known him in the garden. “Don’t mention it,” he enjoined me eagerly. “Don’t give it another thought, old sport.” The familiar expression held no more familiarity than the hand which reassuringly brushed my shoulder. “And don’t forget we’re going up in the hydroplane tomorrow morning, at nine o’clock.” Then the butler, behind his shoulder: “Philadelphia wants you on the phone, sir.” “All right, in a minute. Tell them I’ll be right there… Good night.” “Good night.” “Good night.” He smiled—and suddenly there seemed to be a pleasant significance in having been among the last to go, as if he had desired it all the time. “Good night, old sport… Good night.”

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. “Excerpt from Chapter Three” The Great Gatsby, 1925. https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/64317/pg64317-images.html Public Domain.

Film Trailers and New York Times Reviews

After reading the excerpt from The Great Gatsby , watch these four film trailers. If you choose to take a New Historicism approach, you should use the 1926 version. For a cultural studies approach, please choose two trailers/reviews from the 1949, 1974, and 2013 versions.

1926 Version

Review: Hall, Mordaunt. “Gold and Cocktails.” The New York Times. November 22, 1926. https://www.nytimes.com/1926/11/22/archives/gold-and-cocktails.html

1949 Version

Review: Crowther, Bosley. “The Screen in Review: ‘The Great Gatsby,’ Based on the Novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Opens at the Paramount.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1949/07/14/archives/the-screen-in-review-the-great-gatsby-based-on-novel-of-f-scott.htm l

1974 Version

Review: Canby, Vincent. “A Lavish ‘Gatsby’ Loses the Book’s Spirit.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/03/28/archives/a-lavish-gatsby-loses-book-s-spirit.html%20%0d2013

2013 Version

Review: Scott, A.O. “Shimmying Off the Literary Mantle.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/10/movies/the-great-gatsby-interpreted-by-baz-luhrmann.html

Theoretical Response Assignment Instructions

Instructions.

- 15 points: theoretical response

- 10 points: online discussion (5 points per response) OR class attendance.

Critical Worlds Copyright © 2024 by Liza Long is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Basic Principles of New Historicism in the Light of Stephen Greenblatt's Resonance and Wonder and Invisible Bullets

Related Papers

Shlomy Mualem

This discussion revolves around Greenblatt's The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. Yet, it has a more fundamental purpose—namely, to critically examine Greenblatt's theoretical premise regarding the relations between history, ideology and literary texts in light of Ludwik Fleck's notion of thought-style (denkkollektiv). The analysis of Greenblatt's Lucretian argument demonstrates that when applied to the study of literature, despite its overwhelming creativity and rhetorical charm the neo-historical thought-style is both reductive and woefully speculative. It thus needs to be adopted far more cautiously. In line with Aristotle's notion of mimesis, I finally suggest that studies of this nature should be presented as the embodiment of historical possibilities—i.e., a fictional stance à la " alternative history " approach.

The Johns Hopkins Guide to …

Bryce Traister

Comparative Literature

Anne Coldiron

Tanya Agathocleous , Emily Bartels

Z. S. Baldwin

In this age of instability, when the semiotic paradigm seems to have effectively established the postmodern destabilization of authority by requiring the production of knowledge to be situated in terms of total contingency, Stephen Greenblatt’s position on the central issues of critical theory seems to be situated in the unstable spaces between positions, and it is, I argue, precisely this liminality that allows his productive practice to explore the space between the discourses of Anthropological and Literary analysis, between a work of art and its social context, and between the agency of an existential self and the deconstruction of that self in language. The fecundity of a strategic negotiation of these conceptual conflicts between agency and contingency appears to be at the heart of Greenblatt’s methodological confessions in his essay “The Touch of the Real,” and thus, understanding this negotiation is key to understanding Greenblatt’s ability to produce literary knowledge. In this paper, I examine Greenblatt's ability to mobilize a broad range of linked but distinctive contradictory theoretical positions, and how the tactical negotiations he develops exposes the problematic nature of how the rhetorical strategy of New Historicism fits into the semiotic paradigm.

Res Cogitans

Rasmus Vangshardt

In a metahistorical perspective, the present articles demonstrates that identifications of radical rupture in history often work as an attempt to deny the role of the historical within the humanities and especially within the discipline of comparative literature; it furthermore argues that it also influences the possibility of general cultural criticism because it presupposes certain ontological assumptions of time and history and a specific idea of what ‘modern society’ is. The article concludes by discussing two strategies for a more coherent notion of literary history in C.S. Lewis’ historiographical essays and Bruno Latour’s theory of science respectively. This leads to the claim of the inevitability of history within the humanities: One cannot get dispose of it, even if that were desirable; luckily that is not even the case.

Comparative Literature Studies

Tanya Agathocleous

History and Theory

Jürgen Pieters

edebiyatdergisi.hacettepe.edu.tr

Serpil Oppermann

Pieter Vermeulen

RELATED PAPERS

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVANCED ACADEMIC RESEARCH

Kenneth Azaigba

익산아로마마사지【dalpΦcha5` cΦm】익산오피〄익산오피

nene sbsbsb

La estetización de la ciudad. Políticas de la regeneración urbana

Isabel Fraile Martín

Salāmat-i ijtimā̒ī

simin kazemi

The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance

Bernard Malamud

Christopher Duffin

Sleep and Breathing

anamaria facina

Jessica Rosati

EDULEARN proceedings

Zuzana Sikorová

Grand Dictionnaire des Voisins Orthographiques Non Diacritiques du Français

Cornéliu Tocan

Türk Numismatik Derneği Yayınları

Koray Gürleyük

Revista Argentina de Anatomía Clínica

Francisco Lezcano

Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation

Gitte Sommer Harboe

CALL GIRL IN Majnu Ka Tilla DELHI NCR

delhi munirka

Proceedings of SPIE

Karin Weiss-Wrana

Investigación en Educación Médica

Delia Aguirre

Matheus Denny

Infection, Genetics and Evolution

Keith Crandall

专业办理国外各大文凭 毕业证成绩单录取通知书offer

Isabelle Cherqui-Houot

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, new historicist criticism.

- © 2023 by Angela Eward-Mangione - Hillsborough Community College

New Historicist Criticism is

- a research method , a type of textual research , that literary critics use to interpret texts

- a genre of discourse employed by literary critics used to share the results of their interpretive efforts.

Key Terms: Dialectic ; Hermeneutics ; Semiotics ; Text & Intertextuality ; Tone

American critic Stephen Greenblatt coined the term “New Historicism” (5) in the Introduction to The Power of Forms in the English Renaissance (1982). New Historicism, or Cultural Materialism, considers a literary work within the context of the author’s historical milieu. A key premise of New Historicism is that art and literature are integrated into the material practices of culture. Consequently, literary and non-literary texts circulate together in society. Analyzing a text alongside its historical milieu and relevant documents can demonstrate how a text addresses the social or political concerns of its time period.

New Historicism, or Cultural Materialism, considers a literary work within the context of the author’s historical milieu. A key premise of New Historicism is that art and literature are integrated into the material practices of culture; consequently, literary and non-literary texts circulate together in society. New Historicism may focus on the life of the author; the social, economic, and political circumstances (and non-literary works) of that era; as well as the cultural events of the author’s historical milieu. The cultural events with which a work correlates may be big (social and cultural) or small. Scholars view Raymond Williams as a major figure in the development of Cultural Materialism. American critic Stephen Greenblatt coined the term “New Historicism” (5) in the Introduction of one of his collections of essays about English Renaissance Drama, The Power of Forms in the English Renaissance . Many New Historicist critics have studied Shakespeare’s The Tempest alongside The Bermuda Pamphlets and various travel narratives from the early modern era, speculating about how England’s colonial expeditions in the New World may have influenced Shakespeare’s decision to set The Tempest on an island near Bermuda. Some critics also situate The Tempest during the period of time during in which King James I ruled England and advocated the absolute authority of Kings in both political and spiritual matters. Since Prospero maintains complete authority on the island on which The Tempest is set, some New Historicist critics find a parallel between King James I and Prospero in The Tempest . Additionally, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe can be interpreted in light of the true story of a shipwrecked man named Alexander Selkirk. Analyzing a text alongside its historical milieu and relevant documents can demonstrate how a text addresses the social or political concerns of its time period.

Foundational Questions of New Historicist Criticism

- Does the text address the political or social concerns of its time period? If so, what issues does the text examine?

- What historical events or controversies does the text overtly address or allude to? Does the text comment on those events?

- What types of historical documents (e.g., wills, laws, religious tracts, narratives, art, etc.) might illuminate the meaning and the purpose of the literary text?

- How does the text relate to other literary texts of the same time period?

Online Example: Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress”: A New Historicist Reading

Discussion Questions and Activities: New Historical/Cultural Materialist Criticism

- Identify and define key words that you would consider when approaching a text from a new historical/cultural materialist position.

- Discuss the significance of the fact that art and literature are integrated into the material practices of culture.

- Employ a New Historicist approach to demonstrate how a specific literary text addresses a social topic of its historical milieu.

- Using the Folger Digital Texts from the Folger Shakespeare Library , examine act one, scene two, lines 385-450 of The Tempest . What political concerns, social controversies, or historical events of this time period do you think The Tempest treats?

- What research would you conduct to argue whether or not The Tempest addresses either slavery or colonialism? Support your viewpoint with a few examples of sources that you would explore and include in a research paper about the topic.

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › New Historicism’s Deviation from Old Historicism

New Historicism’s Deviation from Old Historicism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on October 20, 2016 • ( 0 )

New Historicism envisages and practises a mode of study where the literary text and the non-literary cotext are given “equal weighting”, whereas old historicism considers history as a “background” of facts to the “foreground” of literature. While Old historicism follows a hierarchical approach by creating a historical framework and placing the literary text within it, New Historicism, upholding the Derridean view that there is nothing outside the text, or that everything is available to us in “textual” or narrative form, breaks such hierarchies, and follows a parallel reading of literature and history, and looks at history as represented and recorded in literary texts. In short, while Old Historicism is concerned with the “world” of the past, New Historicism deals with the “word” of the past.

This radical difference can be attributed to the remarkable influence of a who Foucault , who thought his “historical” works Madness and Civilization, The Birth of the Clinic, and The Order of Things examined the discursive powers that influenced the development of psychiatry, medicine and the human sciences, respectively. Introducing the archaeological concept of history as archive, Foucault maintained that history is an intersection of multiple discourses with gaps and discontinuities, and suggested an approach of historical analysis to discover/uncover discontinuities in the conditions of human knowledge.

Foucault argues that old historians aimed at reconstituting the past by referring to documents about the past, and, appropriating facts and details such that the incoherent elements are concealed, and create a seemingly unified narrative of history, that complies with the discourse of the time and age. On the contrary, new historicists, work on reference documents from within to understand the inherent fissures. This new approach serves the purpose of proliferation of discontinuities in the history of ideas, in the place of a continuous chronology of reason. This idea is corollary to Foucault’s understanding of knowledge as a manifestation of power:Thus, in a typical poststructuralist manner, new historicists foreground and take pride in discontinuities.

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: Foucault , Literary Theory , Madness and Civilization , New Historicism , New Historicism's Deviation from Old Historicism , Old Historicism , The Birth of the Clinic , The History of Sexuality , The Order of Things

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Introduction to New Historicism

Back to: Literary Theory in English Literature

New Historicism is a literary theory that proposes to understand Literature in connection with culture, politics, history and social realities. New Historicism argues that artistic work is not detached from the social and cultural practices of the times. It was first developed around 1980 by Stephen Greenblatt .

New Historicism proposed that an artistic entity is a product of the social and cultural circumstances in times in which the entity was produced. It is based on the following principles –

A work of art is a part of material practices within society. It states that a work of fiction cannot be totally detached from non-fiction. It further states that a fictional entity is attached to history.

New Historicism fundamentally is defined as a theory that analyzes a text in connection with political and historical realities. Thus New Historicism is the opposite of New Criticism . While New Criticism focused only on the purity of the text , on the other hand, New Historicism rejects the idea of text as an isolated, pure concept.

New Historicism states that a text is not divorced from external agents of influence such as economics, societal influences, and material circumstances. New Historicism also proposes that there is no absolute boundary between fiction and history.

Thus fiction is to be understood through history and history is to be understood through fiction. New Historicism also tells that fiction and non-fiction are not totally separate from each other.

So any artistic production also becomes a medium of political expression. The act of reading and understanding a text happens at the site of performance in the outside world. For instance – A particular book may also tell a lot about its historical backdrop through its storytelling.

New Historicism rejects the idea of art as a purely aesthetic concept. It instead argues that art is connected with material realities in which an artistic entity was produced. Within New Historicism, the emphasis is not on the internal details of a text.

The emphasis of New Historicism is on the external agents surrounding a text. Stephen Greenblatt’s discourse on Shakespeare has led to a breakthrough in the field of New Historicism in which Greenblatt has proposed to rewrite Shakespeare’s legacy through interaction with political, cultural, material, social, economic and historical themes.

For instance – Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest, at a certain point was only read as an artistic work. But New Historicism has given a chance to read the play through a post-colonial lens. Some of the scholars associated with New Historicism are Stuart Hall, Raymond William, and Stephen Greenblatt.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

New-historicist essays are thus often marked by making seemingly unlikely linkages between various cultural products and literary texts. Its "newness" is at once an echo of the New Criticism it replaced and a recognition of an "old" historicism, often exemplified by E. M. W. Tillyard, against which it defines itself.

New Historicism and Cultural Studies criticism are both literary theories and critical approaches that emerged in the latter part of the 20th century. They both focus on the relationship between literature and its historical/cultural context. New Historicism rejects the idea of literary works as isolated, timeless creations and instead emphasizes their embeddedness in the socio-political and ...

New Historicism, a form of literary theory which aims to understand intellectual history through literature and literature through its cultural context, follows the 1950s field of history of ideas and refers to itself as a form of cultural poetics.It first developed in the 1980s, primarily through the work of the critic Stephen Greenblatt, and gained widespread influence in the 1990s.

New Historicism By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on October 22, 2020 • ( 0). In 1982 Stephen Greenblatt edited a special issue of Genre on Renaissance writing, and in his introduction to this volume he claimed that the articles he had solicited were engaged in a joint enterprise, namely, an effort to rethink the ways that early modern texts were situated within the larger spectrum of discourses and ...

New historicism focuses on the history of the human body and the human subject, specifically in relation to life and death, or illness and health. Gallagher and Greenblatt use the example of the potato riots in the 1790s. They explain that economic historians have tended to view the riots as a response to hunger.

26. Student Example Essay: New Historicism. The following student essay example of New Historicism is taken from Beginnings and Endings: A Critical Edition . This is the publication created by students in English 211. This essay discusses Lorrie Moore's short story, "Terrific Mother.".

Greenblatt elaborated his statements about New Historicism in a subsequent influential essay, Towards a Poetics of Culture (1987). He begins by noting that he will not attempt to "define" the New Historicism but rather to "situate it as a practice." What distinguishes it from the "positivist historical scholarship" of the early twentieth century is its openness to recent theory ...

When reading a work through a New Historicism reading, apply the following steps: Determine the time and place, or historical context of the literature. Choose a specific aspect of the text you feel would be illuminated by learning more about the history of the text. Research the history.

The term "New Historicism" posits itself on two fronts against New Criticism and the "old historicism." Joining the words "new" and "his-toricism," Stephen Greenblatt coined the phrase in 1982 as a punning opposition to the term "New Criticism," not as a conscious reference to German historicism.7 Greenblatt, editing a collection of essays on ...