Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.2 Steps in the Marketing Research Process

Learning objective.

- Describe the basic steps in the marketing research process and the purpose of each step.

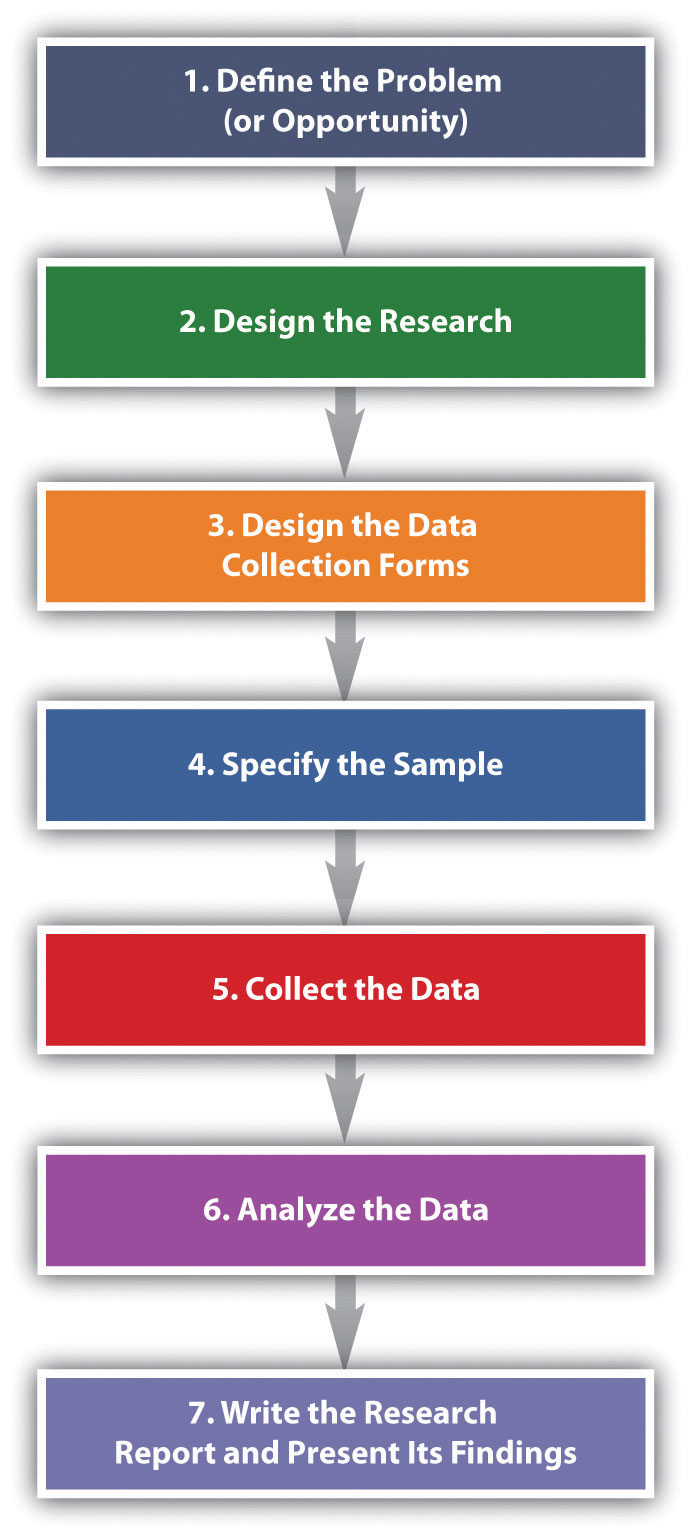

The basic steps used to conduct marketing research are shown in Figure 10.6 “Steps in the Marketing Research Process” . Next, we discuss each step.

Figure 10.6 Steps in the Marketing Research Process

Step 1: Define the Problem (or Opportunity)

There’s a saying in marketing research that a problem half defined is a problem half solved. Defining the “problem” of the research sounds simple, doesn’t it? Suppose your product is tutoring other students in a subject you’re a whiz at. You have been tutoring for a while, and people have begun to realize you’re darned good at it. Then, suddenly, your business drops off. Or it explodes, and you can’t cope with the number of students you’re being asked help. If the business has exploded, should you try to expand your services? Perhaps you should subcontract with some other “whiz” students. You would send them students to be tutored, and they would give you a cut of their pay for each student you referred to them.

Both of these scenarios would be a problem for you, wouldn’t they? They are problems insofar as they cause you headaches. But are they really the problem? Or are they the symptoms of something bigger? For example, maybe your business has dropped off because your school is experiencing financial trouble and has lowered the number of scholarships given to incoming freshmen. Consequently, there are fewer total students on campus who need your services. Conversely, if you’re swamped with people who want you to tutor them, perhaps your school awarded more scholarships than usual, so there are a greater number of students who need your services. Alternately, perhaps you ran an ad in your school’s college newspaper, and that led to the influx of students wanting you to tutor them.

Businesses are in the same boat you are as a tutor. They take a look at symptoms and try to drill down to the potential causes. If you approach a marketing research company with either scenario—either too much or too little business—the firm will seek more information from you such as the following:

- In what semester(s) did your tutoring revenues fall (or rise)?

- In what subject areas did your tutoring revenues fall (or rise)?

- In what sales channels did revenues fall (or rise): Were there fewer (or more) referrals from professors or other students? Did the ad you ran result in fewer (or more) referrals this month than in the past months?

- Among what demographic groups did your revenues fall (or rise)—women or men, people with certain majors, or first-year, second-, third-, or fourth-year students?

The key is to look at all potential causes so as to narrow the parameters of the study to the information you actually need to make a good decision about how to fix your business if revenues have dropped or whether or not to expand it if your revenues have exploded.

The next task for the researcher is to put into writing the research objective. The research objective is the goal(s) the research is supposed to accomplish. The marketing research objective for your tutoring business might read as follows:

To survey college professors who teach 100- and 200-level math courses to determine why the number of students referred for tutoring dropped in the second semester.

This is admittedly a simple example designed to help you understand the basic concept. If you take a marketing research course, you will learn that research objectives get a lot more complicated than this. The following is an example:

“To gather information from a sample representative of the U.S. population among those who are ‘very likely’ to purchase an automobile within the next 6 months, which assesses preferences (measured on a 1–5 scale ranging from ‘very likely to buy’ to ‘not likely at all to buy’) for the model diesel at three different price levels. Such data would serve as input into a forecasting model that would forecast unit sales, by geographic regions of the country, for each combination of the model’s different prices and fuel configurations (Burns & Bush, 2010).”

Now do you understand why defining the problem is complicated and half the battle? Many a marketing research effort is doomed from the start because the problem was improperly defined. Coke’s ill-fated decision to change the formula of Coca-Cola in 1985 is a case in point: Pepsi had been creeping up on Coke in terms of market share over the years as well as running a successful promotional campaign called the “Pepsi Challenge,” in which consumers were encouraged to do a blind taste test to see if they agreed that Pepsi was better. Coke spent four years researching “the problem.” Indeed, people seemed to like the taste of Pepsi better in blind taste tests. Thus, the formula for Coke was changed. But the outcry among the public was so great that the new formula didn’t last long—a matter of months—before the old formula was reinstated. Some marketing experts believe Coke incorrectly defined the problem as “How can we beat Pepsi in taste tests?” instead of “How can we gain market share against Pepsi?” (Burns & Bush, 2010)

New Coke Is It! 1985

(click to see video)

This video documents the Coca-Cola Company’s ill-fated launch of New Coke in 1985.

1985 Pepsi Commercial—“They Changed My Coke”

This video shows how Pepsi tried to capitalize on the blunder.

Step 2: Design the Research

The next step in the marketing research process is to do a research design. The research design is your “plan of attack.” It outlines what data you are going to gather and from whom, how and when you will collect the data, and how you will analyze it once it’s been obtained. Let’s look at the data you’re going to gather first.

There are two basic types of data you can gather. The first is primary data. Primary data is information you collect yourself, using hands-on tools such as interviews or surveys, specifically for the research project you’re conducting. Secondary data is data that has already been collected by someone else, or data you have already collected for another purpose. Collecting primary data is more time consuming, work intensive, and expensive than collecting secondary data. Consequently, you should always try to collect secondary data first to solve your research problem, if you can. A great deal of research on a wide variety of topics already exists. If this research contains the answer to your question, there is no need for you to replicate it. Why reinvent the wheel?

Sources of Secondary Data

Your company’s internal records are a source of secondary data. So are any data you collect as part of your marketing intelligence gathering efforts. You can also purchase syndicated research. Syndicated research is primary data that marketing research firms collect on a regular basis and sell to other companies. J.D. Power & Associates is a provider of syndicated research. The company conducts independent, unbiased surveys of customer satisfaction, product quality, and buyer behavior for various industries. The company is best known for its research in the automobile sector. One of the best-known sellers of syndicated research is the Nielsen Company, which produces the Nielsen ratings. The Nielsen ratings measure the size of television, radio, and newspaper audiences in various markets. You have probably read or heard about TV shows that get the highest (Nielsen) ratings. (Arbitron does the same thing for radio ratings.) Nielsen, along with its main competitor, Information Resources, Inc. (IRI), also sells businesses scanner-based research . Scanner-based research is information collected by scanners at checkout stands in stores. Each week Nielsen and IRI collect information on the millions of purchases made at stores. The companies then compile the information and sell it to firms in various industries that subscribe to their services. The Nielsen Company has also recently teamed up with Facebook to collect marketing research information. Via Facebook, users will see surveys in some of the spaces in which they used to see online ads (Rappeport, Gelles, 2009).

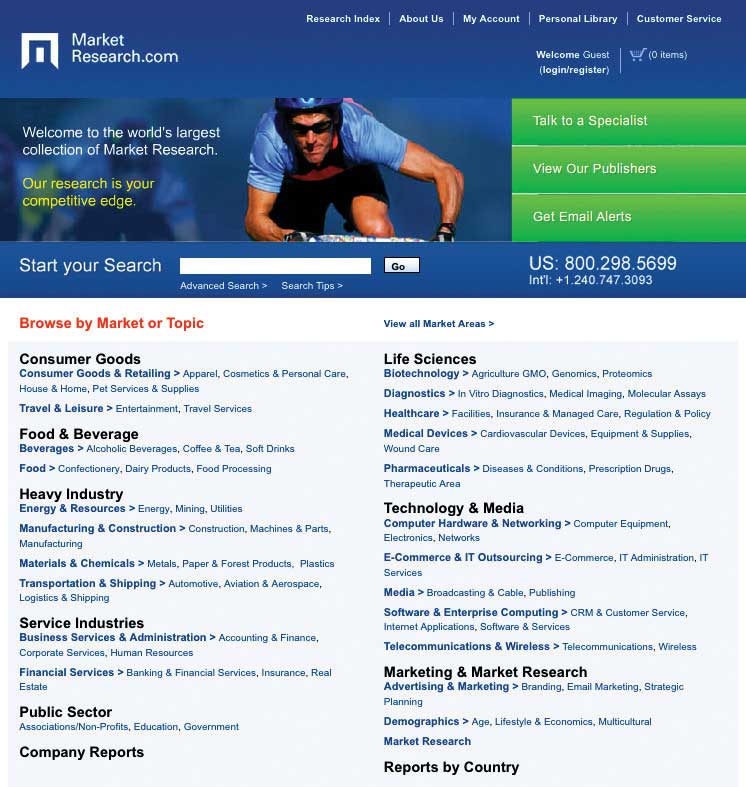

By contrast, MarketResearch.com is an example of a marketing research aggregator. A marketing research aggregator is a marketing research company that doesn’t conduct its own research and sell it. Instead, it buys research reports from other marketing research companies and then sells the reports in their entirety or in pieces to other firms. Check out MarketResearch.com’s Web site. As you will see there are a huge number of studies in every category imaginable that you can buy for relatively small amounts of money.

Figure 10.7

Market research aggregators buy research reports from other marketing research companies and then resell them in part or in whole to other companies so they don’t have to gather primary data.

Source: http://www.marketresearch.com .

Your local library is a good place to gather free secondary data. It has searchable databases as well as handbooks, dictionaries, and books, some of which you can access online. Government agencies also collect and report information on demographics, economic and employment data, health information, and balance-of-trade statistics, among a lot of other information. The U.S. Census Bureau collects census data every ten years to gather information about who lives where. Basic demographic information about sex, age, race, and types of housing in which people live in each U.S. state, metropolitan area, and rural area is gathered so that population shifts can be tracked for various purposes, including determining the number of legislators each state should have in the U.S. House of Representatives. For the U.S. government, this is primary data. For marketing managers it is an important source of secondary data.

The Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan also conducts periodic surveys and publishes information about trends in the United States. One research study the center continually conducts is called the “Changing Lives of American Families” ( http://www.isr.umich.edu/home/news/research-update/2007-01.pdf ). This is important research data for marketing managers monitoring consumer trends in the marketplace. The World Bank and the United Nations are two international organizations that collect a great deal of information. Their Web sites contain many free research studies and data related to global markets. Table 10.1 “Examples of Primary Data Sources versus Secondary Data Sources” shows some examples of primary versus secondary data sources.

Table 10.1 Examples of Primary Data Sources versus Secondary Data Sources

| Primary Data Sources | Secondary Data Sources |

|---|---|

| Interviews | Census data |

| Surveys | Web sites |

| Publications | |

| Trade associations | |

| Syndicated research and market aggregators |

Gauging the Quality of Secondary Data

When you are gathering secondary information, it’s always good to be a little skeptical of it. Sometimes studies are commissioned to produce the result a client wants to hear—or wants the public to hear. For example, throughout the twentieth century, numerous studies found that smoking was good for people’s health. The problem was the studies were commissioned by the tobacco industry. Web research can also pose certain hazards. There are many biased sites that try to fool people that they are providing good data. Often the data is favorable to the products they are trying to sell. Beware of product reviews as well. Unscrupulous sellers sometimes get online and create bogus ratings for products. See below for questions you can ask to help gauge the credibility of secondary information.

Gauging the Credibility of Secondary Data: Questions to Ask

- Who gathered this information?

- For what purpose?

- What does the person or organization that gathered the information have to gain by doing so?

- Was the information gathered and reported in a systematic manner?

- Is the source of the information accepted as an authority by other experts in the field?

- Does the article provide objective evidence to support the position presented?

Types of Research Design

Now let’s look specifically at the types of research designs that are utilized. By understanding different types of research designs, a researcher can solve a client’s problems more quickly and efficiently without jumping through more hoops than necessary. Research designs fall into one of the following three categories:

- Exploratory research design

- Descriptive research design

- Causal research design (experiments)

An exploratory research design is useful when you are initially investigating a problem but you haven’t defined it well enough to do an in-depth study of it. Perhaps via your regular market intelligence, you have spotted what appears to be a new opportunity in the marketplace. You would then do exploratory research to investigate it further and “get your feet wet,” as the saying goes. Exploratory research is less structured than other types of research, and secondary data is often utilized.

One form of exploratory research is qualitative research. Qualitative research is any form of research that includes gathering data that is not quantitative, and often involves exploring questions such as why as much as what or how much . Different forms, such as depth interviews and focus group interviews, are common in marketing research.

The depth interview —engaging in detailed, one-on-one, question-and-answer sessions with potential buyers—is an exploratory research technique. However, unlike surveys, the people being interviewed aren’t asked a series of standard questions. Instead the interviewer is armed with some general topics and asks questions that are open ended, meaning that they allow the interviewee to elaborate. “How did you feel about the product after you purchased it?” is an example of a question that might be asked. A depth interview also allows a researcher to ask logical follow-up questions such as “Can you tell me what you mean when you say you felt uncomfortable using the service?” or “Can you give me some examples?” to help dig further and shed additional light on the research problem. Depth interviews can be conducted in person or over the phone. The interviewer either takes notes or records the interview.

Focus groups and case studies are often utilized for exploratory research as well. A focus group is a group of potential buyers who are brought together to discuss a marketing research topic with one another. A moderator is used to focus the discussion, the sessions are recorded, and the main points of consensus are later summarized by the market researcher. Textbook publishers often gather groups of professors at educational conferences to participate in focus groups. However, focus groups can also be conducted on the telephone, in online chat rooms, or both, using meeting software like WebEx. The basic steps of conducting a focus group are outlined below.

The Basic Steps of Conducting a Focus Group

- Establish the objectives of the focus group. What is its purpose?

- Identify the people who will participate in the focus group. What makes them qualified to participate? How many of them will you need and what they will be paid?

- Obtain contact information for the participants and send out invitations (usually e-mails are most efficient).

- Develop a list of questions.

- Choose a facilitator.

- Choose a location in which to hold the focus group and the method by which it will be recorded.

- Conduct the focus group. If the focus group is not conducted electronically, include name tags for the participants, pens and notepads, any materials the participants need to see, and refreshments. Record participants’ responses.

- Summarize the notes from the focus group and write a report for management.

A case study looks at how another company solved the problem that’s being researched. Sometimes multiple cases, or companies, are used in a study. Case studies nonetheless have a mixed reputation. Some researchers believe it’s hard to generalize, or apply, the results of a case study to other companies. Nonetheless, collecting information about companies that encountered the same problems your firm is facing can give you a certain amount of insight about what direction you should take. In fact, one way to begin a research project is to carefully study a successful product or service.

Two other types of qualitative data used for exploratory research are ethnographies and projective techniques. In an ethnography , researchers interview, observe, and often videotape people while they work, live, shop, and play. The Walt Disney Company has recently begun using ethnographers to uncover the likes and dislikes of boys aged six to fourteen, a financially attractive market segment for Disney, but one in which the company has been losing market share. The ethnographers visit the homes of boys, observe the things they have in their rooms to get a sense of their hobbies, and accompany them and their mothers when they shop to see where they go, what the boys are interested in, and what they ultimately buy. (The children get seventy-five dollars out of the deal, incidentally.) (Barnes, 2009)

Projective techniques are used to reveal information research respondents might not reveal by being asked directly. Asking a person to complete sentences such as the following is one technique:

People who buy Coach handbags __________.

(Will he or she reply with “are cool,” “are affluent,” or “are pretentious,” for example?)

KFC’s grilled chicken is ______.

Or the person might be asked to finish a story that presents a certain scenario. Word associations are also used to discern people’s underlying attitudes toward goods and services. Using a word-association technique, a market researcher asks a person to say or write the first word that comes to his or her mind in response to another word. If the initial word is “fast food,” what word does the person associate it with or respond with? Is it “McDonald’s”? If many people reply that way, and you’re conducting research for Burger King, that could indicate Burger King has a problem. However, if the research is being conducted for Wendy’s, which recently began running an advertising campaign to the effect that Wendy’s offerings are “better than fast food,” it could indicate that the campaign is working.

Completing cartoons is yet another type of projective technique. It’s similar to finishing a sentence or story, only with the pictures. People are asked to look at a cartoon such as the one shown in Figure 10.8 “Example of a Cartoon-Completion Projective Technique” . One of the characters in the picture will have made a statement, and the person is asked to fill in the empty cartoon “bubble” with how they think the second character will respond.

Figure 10.8 Example of a Cartoon-Completion Projective Technique

In some cases, your research might end with exploratory research. Perhaps you have discovered your organization lacks the resources needed to produce the product. In other cases, you might decide you need more in-depth, quantitative research such as descriptive research or causal research, which are discussed next. Most marketing research professionals advise using both types of research, if it’s feasible. On the one hand, the qualitative-type research used in exploratory research is often considered too “lightweight.” Remember earlier in the chapter when we discussed telephone answering machines and the hit TV sitcom Seinfeld ? Both product ideas were initially rejected by focus groups. On the other hand, relying solely on quantitative information often results in market research that lacks ideas.

The Stone Wheel—What One Focus Group Said

Watch the video to see a funny spoof on the usefulness—or lack of usefulness—of focus groups.

Descriptive Research

Anything that can be observed and counted falls into the category of descriptive research design. A study using a descriptive research design involves gathering hard numbers, often via surveys, to describe or measure a phenomenon so as to answer the questions of who , what , where , when , and how . “On a scale of 1–5, how satisfied were you with your service?” is a question that illustrates the information a descriptive research design is supposed to capture.

Physiological measurements also fall into the category of descriptive design. Physiological measurements measure people’s involuntary physical responses to marketing stimuli, such as an advertisement. Elsewhere, we explained that researchers have gone so far as to scan the brains of consumers to see what they really think about products versus what they say about them. Eye tracking is another cutting-edge type of physiological measurement. It involves recording the movements of a person’s eyes when they look at some sort of stimulus, such as a banner ad or a Web page. The Walt Disney Company has a research facility in Austin, Texas, that it uses to take physical measurements of viewers when they see Disney programs and advertisements. The facility measures three types of responses: people’s heart rates, skin changes, and eye movements (eye tracking) (Spangler, 2009).

Figure 10.9

A woman shows off her headgear for an eye-tracking study. The gear’s not exactly a fashion statement but . . .

lawrencegs – Google Glass – CC BY 2.0.

A strictly descriptive research design instrument—a survey, for example—can tell you how satisfied your customers are. It can’t, however, tell you why. Nor can an eye-tracking study tell you why people’s eyes tend to dwell on certain types of banner ads—only that they do. To answer “why” questions an exploratory research design or causal research design is needed (Wagner, 2007).

Causal Research

Causal research design examines cause-and-effect relationships. Using a causal research design allows researchers to answer “what if” types of questions. In other words, if a firm changes X (say, a product’s price, design, placement, or advertising), what will happen to Y (say, sales or customer loyalty)? To conduct causal research, the researcher designs an experiment that “controls,” or holds constant, all of a product’s marketing elements except one (or using advanced techniques of research, a few elements can be studied at the same time). The one variable is changed, and the effect is then measured. Sometimes the experiments are conducted in a laboratory using a simulated setting designed to replicate the conditions buyers would experience. Or the experiments may be conducted in a virtual computer setting.

You might think setting up an experiment in a virtual world such as the online game Second Life would be a viable way to conduct controlled marketing research. Some companies have tried to use Second Life for this purpose, but the results have been somewhat mixed as to whether or not it is a good medium for marketing research. The German marketing research firm Komjuniti was one of the first “real-world” companies to set up an “island” in Second Life upon which it could conduct marketing research. However, with so many other attractive fantasy islands in which to play, the company found it difficult to get Second Life residents, or players, to voluntarily visit the island and stay long enough so meaningful research could be conducted. (Plus, the “residents,” or players, in Second Life have been known to protest corporations invading their world. When the German firm Komjuniti created an island in Second Life to conduct marketing research, the residents showed up waving signs and threatening to boycott the island.) (Wagner, 2007)

Why is being able to control the setting so important? Let’s say you are an American flag manufacturer and you are working with Walmart to conduct an experiment to see where in its stores American flags should be placed so as to increase their sales. Then the terrorist attacks of 9/11 occur. In the days afterward, sales skyrocketed—people bought flags no matter where they were displayed. Obviously, the terrorist attacks in the United States would have skewed the experiment’s data.

An experiment conducted in a natural setting such as a store is referred to as a field experiment . Companies sometimes do field experiments either because it is more convenient or because they want to see if buyers will behave the same way in the “real world” as in a laboratory or on a computer. The place the experiment is conducted or the demographic group of people the experiment is administered to is considered the test market . Before a large company rolls out a product to the entire marketplace, it will often place the offering in a test market to see how well it will be received. For example, to compete with MillerCoors’ sixty-four-calorie beer MGD 64, Anheuser-Busch recently began testing its Select 55 beer in certain cities around the country (McWilliams, 2009).

Figure 10.10

Select 55 beer: Coming soon to a test market near you? (If you’re on a diet, you have to hope so!)

Martine – Le champagne – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Many companies use experiments to test all of their marketing communications. For example, the online discount retailer O.co (formerly called Overstock.com) carefully tests all of its marketing offers and tracks the results of each one. One study the company conducted combined twenty-six different variables related to offers e-mailed to several thousand customers. The study resulted in a decision to send a group of e-mails to different segments. The company then tracked the results of the sales generated to see if they were in line with the earlier experiment it had conducted that led it to make the offer.

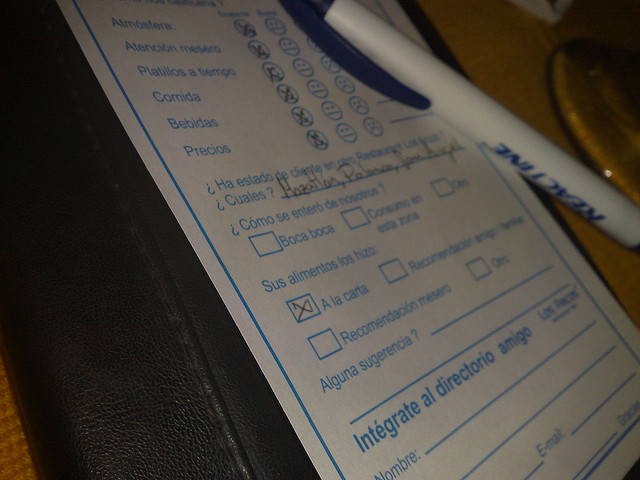

Step 3: Design the Data-Collection Forms

If the behavior of buyers is being formally observed, and a number of different researchers are conducting observations, the data obviously need to be recorded on a standardized data-collection form that’s either paper or electronic. Otherwise, the data collected will not be comparable. The items on the form could include a shopper’s sex; his or her approximate age; whether the person seemed hurried, moderately hurried, or unhurried; and whether or not he or she read the label on products, used coupons, and so forth.

The same is true when it comes to surveying people with questionnaires. Surveying people is one of the most commonly used techniques to collect quantitative data. Surveys are popular because they can be easily administered to large numbers of people fairly quickly. However, to produce the best results, the questionnaire for the survey needs to be carefully designed.

Questionnaire Design

Most questionnaires follow a similar format: They begin with an introduction describing what the study is for, followed by instructions for completing the questionnaire and, if necessary, returning it to the market researcher. The first few questions that appear on the questionnaire are usually basic, warm-up type of questions the respondent can readily answer, such as the respondent’s age, level of education, place of residence, and so forth. The warm-up questions are then followed by a logical progression of more detailed, in-depth questions that get to the heart of the question being researched. Lastly, the questionnaire wraps up with a statement that thanks the respondent for participating in the survey and information and explains when and how they will be paid for participating. To see some examples of questionnaires and how they are laid out, click on the following link: http://cas.uah.edu/wrenb/mkt343/Project/Sample%20Questionnaires.htm .

How the questions themselves are worded is extremely important. It’s human nature for respondents to want to provide the “correct” answers to the person administering the survey, so as to seem agreeable. Therefore, there is always a hazard that people will try to tell you what you want to hear on a survey. Consequently, care needs to be taken that the survey questions are written in an unbiased, neutral way. In other words, they shouldn’t lead a person taking the questionnaire to answer a question one way or another by virtue of the way you have worded it. The following is an example of a leading question.

Don’t you agree that teachers should be paid more ?

The questions also need to be clear and unambiguous. Consider the following question:

Which brand of toothpaste do you use ?

The question sounds clear enough, but is it really? What if the respondent recently switched brands? What if she uses Crest at home, but while away from home or traveling, she uses Colgate’s Wisp portable toothpaste-and-brush product? How will the respondent answer the question? Rewording the question as follows so it’s more specific will help make the question clearer:

Which brand of toothpaste have you used at home in the past six months? If you have used more than one brand, please list each of them 1 .

Sensitive questions have to be asked carefully. For example, asking a respondent, “Do you consider yourself a light, moderate, or heavy drinker?” can be tricky. Few people want to admit to being heavy drinkers. You can “soften” the question by including a range of answers, as the following example shows:

How many alcoholic beverages do you consume in a week ?

- __0–5 alcoholic beverages

- __5–10 alcoholic beverages

- __10–15 alcoholic beverages

Many people don’t like to answer questions about their income levels. Asking them to specify income ranges rather than divulge their actual incomes can help.

Other research question “don’ts” include using jargon and acronyms that could confuse people. “How often do you IM?” is an example. Also, don’t muddy the waters by asking two questions in the same question, something researchers refer to as a double-barreled question . “Do you think parents should spend more time with their children and/or their teachers?” is an example of a double-barreled question.

Open-ended questions , or questions that ask respondents to elaborate, can be included. However, they are harder to tabulate than closed-ended questions , or questions that limit a respondent’s answers. Multiple-choice and yes-and-no questions are examples of closed-ended questions.

Testing the Questionnaire

You have probably heard the phrase “garbage in, garbage out.” If the questions are bad, the information gathered will be bad, too. One way to make sure you don’t end up with garbage is to test the questionnaire before sending it out to find out if there are any problems with it. Is there enough space for people to elaborate on open-ended questions? Is the font readable? To test the questionnaire, marketing research professionals first administer it to a number of respondents face to face. This gives the respondents the chance to ask the researcher about questions or instructions that are unclear or don’t make sense to them. The researcher then administers the questionnaire to a small subset of respondents in the actual way the survey is going to be disseminated, whether it’s delivered via phone, in person, by mail, or online.

Getting people to participate and complete questionnaires can be difficult. If the questionnaire is too long or hard to read, many people won’t complete it. So, by all means, eliminate any questions that aren’t necessary. Of course, including some sort of monetary incentive for completing the survey can increase the number of completed questionnaires a market researcher will receive.

Step 4: Specify the Sample

Once you have created your questionnaire or other marketing study, how do you figure out who should participate in it? Obviously, you can’t survey or observe all potential buyers in the marketplace. Instead, you must choose a sample. A sample is a subset of potential buyers that are representative of your entire target market, or population being studied. Sometimes market researchers refer to the population as the universe to reflect the fact that it includes the entire target market, whether it consists of a million people, a hundred thousand, a few hundred, or a dozen. “All unmarried people over the age of eighteen who purchased Dirt Devil steam cleaners in the United States during 2011” is an example of a population that has been defined.

Obviously, the population has to be defined correctly. Otherwise, you will be studying the wrong group of people. Not defining the population correctly can result in flawed research, or sampling error. A sampling error is any type of marketing research mistake that results because a sample was utilized. One criticism of Internet surveys is that the people who take these surveys don’t really represent the overall population. On average, Internet survey takers tend to be more educated and tech savvy. Consequently, if they solely constitute your population, even if you screen them for certain criteria, the data you collect could end up being skewed.

The next step is to put together the sampling frame , which is the list from which the sample is drawn. The sampling frame can be put together using a directory, customer list, or membership roster (Wrenn et. al., 2007). Keep in mind that the sampling frame won’t perfectly match the population. Some people will be included on the list who shouldn’t be. Other people who should be included will be inadvertently omitted. It’s no different than if you were to conduct a survey of, say, 25 percent of your friends, using friends’ names you have in your cell phone. Most of your friends’ names are likely to be programmed into your phone, but not all of them. As a result, a certain degree of sampling error always occurs.

There are two main categories of samples in terms of how they are drawn: probability samples and nonprobability samples. A probability sample is one in which each would-be participant has a known and equal chance of being selected. The chance is known because the total number of people in the sampling frame is known. For example, if every other person from the sampling frame were chosen, each person would have a 50 percent chance of being selected.

A nonprobability sample is any type of sample that’s not drawn in a systematic way. So the chances of each would-be participant being selected can’t be known. A convenience sample is one type of nonprobability sample. It is a sample a researcher draws because it’s readily available and convenient to do so. Surveying people on the street as they pass by is an example of a convenience sample. The question is, are these people representative of the target market?

For example, suppose a grocery store needed to quickly conduct some research on shoppers to get ready for an upcoming promotion. Now suppose that the researcher assigned to the project showed up between the hours of 10 a.m. and 12 p.m. on a weekday and surveyed as many shoppers as possible. The problem is that the shoppers wouldn’t be representative of the store’s entire target market. What about commuters who stop at the store before and after work? Their views wouldn’t be represented. Neither would people who work the night shift or shop at odd hours. As a result, there would be a lot of room for sampling error in this study. For this reason, studies that use nonprobability samples aren’t considered as accurate as studies that use probability samples. Nonprobability samples are more often used in exploratory research.

Lastly, the size of the sample has an effect on the amount of sampling error. Larger samples generally produce more accurate results. The larger your sample is, the more data you will have, which will give you a more complete picture of what you’re studying. However, the more people surveyed or studied, the more costly the research becomes.

Statistics can be used to determine a sample’s optimal size. If you take a marketing research or statistics class, you will learn more about how to determine the optimal size.

Of course, if you hire a marketing research company, much of this work will be taken care of for you. Many marketing research companies, like ResearchNow, maintain panels of prescreened people they draw upon for samples. In addition, the marketing research firm will be responsible for collecting the data or contracting with a company that specializes in data collection. Data collection is discussed next.

Step 5: Collect the Data

As we have explained, primary marketing research data can be gathered in a number of ways. Surveys, taking physical measurements, and observing people are just three of the ways we discussed. If you’re observing customers as part of gathering the data, keep in mind that if shoppers are aware of the fact, it can have an effect on their behavior. For example, if a customer shopping for feminine hygiene products in a supermarket aisle realizes she is being watched, she could become embarrassed and leave the aisle, which would adversely affect your data. To get around problems such as these, some companies set up cameras or two-way mirrors to observe customers. Organizations also hire mystery shoppers to work around the problem. A mystery shopper is someone who is paid to shop at a firm’s establishment or one of its competitors to observe the level of service, cleanliness of the facility, and so forth, and report his or her findings to the firm.

Make Extra Money as a Mystery Shopper

Watch the YouTube video to get an idea of how mystery shopping works.

Survey data can be collected in many different ways and combinations of ways. The following are the basic methods used:

- Face-to-face (can be computer aided)

- Telephone (can be computer aided or completely automated)

- Mail and hand delivery

- E-mail and the Web

A face-to-face survey is, of course, administered by a person. The surveys are conducted in public places such as in shopping malls, on the street, or in people’s homes if they have agreed to it. In years past, it was common for researchers in the United States to knock on people’s doors to gather survey data. However, randomly collected door-to-door interviews are less common today, partly because people are afraid of crime and are reluctant to give information to strangers (McDaniel & Gates, 1998).

Nonetheless, “beating the streets” is still a legitimate way questionnaire data is collected. When the U.S. Census Bureau collects data on the nation’s population, it hand delivers questionnaires to rural households that do not have street-name and house-number addresses. And Census Bureau workers personally survey the homeless to collect information about their numbers. Face-to-face surveys are also commonly used in third world countries to collect information from people who cannot read or lack phones and computers.

A plus of face-to-face surveys is that they allow researchers to ask lengthier, more complex questions because the people being surveyed can see and read the questionnaires. The same is true when a computer is utilized. For example, the researcher might ask the respondent to look at a list of ten retail stores and rank the stores from best to worst. The same question wouldn’t work so well over the telephone because the person couldn’t see the list. The question would have to be rewritten. Another drawback with telephone surveys is that even though federal and state “do not call” laws generally don’t prohibit companies from gathering survey information over the phone, people often screen such calls using answering machines and caller ID.

Probably the biggest drawback of both surveys conducted face-to-face and administered over the phone by a person is that they are labor intensive and therefore costly. Mailing out questionnaires is costly, too, and the response rates can be rather low. Think about why that might be so: if you receive a questionnaire in the mail, it is easy to throw it in the trash; it’s harder to tell a market researcher who approaches you on the street that you don’t want to be interviewed.

By contrast, gathering survey data collected by a computer, either over the telephone or on the Internet, can be very cost-effective and in some cases free. SurveyMonkey and Zoomerang are two Web sites that will allow you to create online questionnaires, e-mail them to up to one hundred people for free, and view the responses in real time as they come in. For larger surveys, you have to pay a subscription price of a few hundred dollars. But that still can be extremely cost-effective. The two Web sites also have a host of other features such as online-survey templates you can use to create your questionnaire, a way to set up automatic reminders sent to people who haven’t yet completed their surveys, and tools you can use to create graphics to put in your final research report. To see how easy it is to put together a survey in SurveyMonkey, click on the following link: http://help.surveymonkey.com/app/tutorials/detail/a_id/423 .

Like a face-to-face survey, an Internet survey can enable you to show buyers different visuals such as ads, pictures, and videos of products and their packaging. Web surveys are also fast, which is a major plus. Whereas face-to-face and mailed surveys often take weeks to collect, you can conduct a Web survey in a matter of days or even hours. And, of course, because the information is electronically gathered it can be automatically tabulated. You can also potentially reach a broader geographic group than you could if you had to personally interview people. The Zoomerang Web site allows you to create surveys in forty different languages.

Another plus for Web and computer surveys (and electronic phone surveys) is that there is less room for human error because the surveys are administered electronically. For instance, there’s no risk that the interviewer will ask a question wrong or use a tone of voice that could mislead the respondents. Respondents are also likely to feel more comfortable inputting the information into a computer if a question is sensitive than they would divulging the information to another person face-to-face or over the phone. Given all of these advantages, it’s not surprising that the Internet is quickly becoming the top way to collect primary data. However, like mail surveys, surveys sent to people over the Internet are easy to ignore.

Lastly, before the data collection process begins, the surveyors and observers need to be trained to look for the same things, ask questions the same way, and so forth. If they are using rankings or rating scales, they need to be “on the same page,” so to speak, as to what constitutes a high ranking or a low ranking. As an analogy, you have probably had some teachers grade your college papers harder than others. The goal of training is to avoid a wide disparity between how different observers and interviewers record the data.

Figure 10.11

Training people so they know what constitutes different ratings when they are collecting data will improve the quality of the information gathered in a marketing research study.

Ricardo Rodriquez – Satisfaction survey – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

For example, if an observation form asks the observers to describe whether a shopper’s behavior is hurried, moderately hurried, or unhurried, they should be given an idea of what defines each rating. Does it depend on how much time the person spends in the store or in the individual aisles? How fast they walk? In other words, the criteria and ratings need to be spelled out.

Collecting International Marketing Research Data

Gathering marketing research data in foreign countries poses special challenges. However, that doesn’t stop firms from doing so. Marketing research companies are located all across the globe, in fact. Eight of the ten largest marketing research companies in the world are headquartered in the United States. However, five of these eight firms earn more of their revenues abroad than they do in the United States. There’s a reason for this: many U.S. markets were saturated, or tapped out, long ago in terms of the amount that they can grow. Coke is an example. As you learned earlier in the book, most of the Coca-Cola Company’s revenues are earned in markets abroad. To be sure, the United States is still a huge market when it comes to the revenues marketing research firms generate by conducting research in the country: in terms of their spending, American consumers fuel the world’s economic engine. Still, emerging countries with growing middle classes, such as China, India, and Brazil, are hot new markets companies want to tap.

What kind of challenges do firms face when trying to conduct marketing research abroad? As we explained, face-to-face surveys are commonly used in third world countries to collect information from people who cannot read or lack phones and computers. However, face-to-face surveys are also common in Europe, despite the fact that phones and computers are readily available. In-home surveys are also common in parts of Europe. By contrast, in some countries, including many Asian countries, it’s considered taboo or rude to try to gather information from strangers either face-to-face or over the phone. In many Muslim countries, women are forbidden to talk to strangers.

And how do you figure out whom to research in foreign countries? That in itself is a problem. In the United States, researchers often ask if they can talk to the heads of households to conduct marketing research. But in countries in which domestic servants or employees are common, the heads of households aren’t necessarily the principal shoppers; their domestic employees are (Malhotra).

Translating surveys is also an issue. Have you ever watched the TV comedians Jay Leno and David Letterman make fun of the English translations found on ethnic menus and products? Research tools such as surveys can suffer from the same problem. Hiring someone who is bilingual to translate a survey into another language can be a disaster if the person isn’t a native speaker of the language to which the survey is being translated.

One way companies try to deal with translation problems is by using back translation. When back translation is used, a native speaker translates the survey into the foreign language and then translates it back again to the original language to determine if there were gaps in meaning—that is, if anything was lost in translation. And it’s not just the language that’s an issue. If the research involves any visual images, they, too, could be a point of confusion. Certain colors, shapes, and symbols can have negative connotations in other countries. For example, the color white represents purity in many Western cultures, but in China, it is the color of death and mourning (Zouhali-Worrall, 2008). Also, look back at the cartoon-completion exercise in Figure 10.8 “Example of a Cartoon-Completion Projective Technique” . What would women in Muslim countries who aren’t allowed to converse with male sellers think of it? Chances are, the cartoon wouldn’t provide you with the information you’re seeking if Muslim women in some countries were asked to complete it.

One way marketing research companies are dealing with the complexities of global research is by merging with or acquiring marketing research companies abroad. The Nielsen Company is the largest marketing research company in the world. The firm operates in more than a hundred countries and employs more than forty thousand people. Many of its expansions have been the result of acquisitions and mergers.

Step 6: Analyze the Data

Step 6 involves analyzing the data to ensure it’s as accurate as possible. If the research is collected by hand using a pen and pencil, it’s entered into a computer. Or respondents might have already entered the information directly into a computer. For example, when Toyota goes to an event such as a car show, the automaker’s marketing personnel ask would-be buyers to complete questionnaires directly on computers. Companies are also beginning to experiment with software that can be used to collect data using mobile phones.

Once all the data is collected, the researchers begin the data cleaning , which is the process of removing data that have accidentally been duplicated (entered twice into the computer) or correcting data that have obviously been recorded wrong. A program such as Microsoft Excel or a statistical program such as Predictive Analytics Software (PASW, which was formerly known as SPSS) is then used to tabulate, or calculate, the basic results of the research, such as the total number of participants and how collectively they answered various questions. The programs can also be used to calculate averages, such as the average age of respondents, their average satisfaction, and so forth. The same can done for percentages, and other values you learned about, or will learn about, in a statistics course, such as the standard deviation, mean, and median for each question.

The information generated by the programs can be used to draw conclusions, such as what all customers might like or not like about an offering based on what the sample group liked or did not like. The information can also be used to spot differences among groups of people. For example, the research might show that people in one area of the country like the product better than people in another area. Trends to predict what might happen in the future can also be spotted.

If there are any open-ended questions respondents have elaborated upon—for example, “Explain why you like the current brand you use better than any other brand”—the answers to each are pasted together, one on top of another, so researchers can compare and summarize the information. As we have explained, qualitative information such as this can give you a fuller picture of the results of the research.

Part of analyzing the data is to see if it seems sound. Does the way in which the research was conducted seem sound? Was the sample size large enough? Are the conclusions that become apparent from it reasonable?

The two most commonly used criteria used to test the soundness of a study are (1) validity and (2) reliability. A study is valid if it actually tested what it was designed to test. For example, did the experiment you ran in Second Life test what it was designed to test? Did it reflect what could really happen in the real world? If not, the research isn’t valid. If you were to repeat the study, and get the same results (or nearly the same results), the research is said to be reliable . If you get a drastically different result if you repeat the study, it’s not reliable. The data collected, or at least some it, can also be compared to, or reconciled with, similar data from other sources either gathered by your firm or by another organization to see if the information seems on target.

Stage 7: Write the Research Report and Present Its Findings

If you end up becoming a marketing professional and conducting a research study after you graduate, hopefully you will do a great job putting the study together. You will have defined the problem correctly, chosen the right sample, collected the data accurately, analyzed it, and your findings will be sound. At that point, you will be required to write the research report and perhaps present it to an audience of decision makers. You will do so via a written report and, in some cases, a slide or PowerPoint presentation based on your written report.

The six basic elements of a research report are as follows.

- Title Page . The title page explains what the report is about, when it was conducted and by whom, and who requested it.

- Table of Contents . The table of contents outlines the major parts of the report, as well as any graphs and charts, and the page numbers on which they can be found.

- Executive Summary . The executive summary summarizes all the details in the report in a very quick way. Many people who receive the report—both executives and nonexecutives—won’t have time to read the entire report. Instead, they will rely on the executive summary to quickly get an idea of the study’s results and what to do about those results.

Methodology and Limitations . The methodology section of the report explains the technical details of how the research was designed and conducted. The section explains, for example, how the data was collected and by whom, the size of the sample, how it was chosen, and whom or what it consisted of (e.g., the number of women versus men or children versus adults). It also includes information about the statistical techniques used to analyze the data.

Every study has errors—sampling errors, interviewer errors, and so forth. The methodology section should explain these details, so decision makers can consider their overall impact. The margin of error is the overall tendency of the study to be off kilter—that is, how far it could have gone wrong in either direction. Remember how newscasters present the presidential polls before an election? They always say, “This candidate is ahead 48 to 44 percent, plus or minus 2 percent.” That “plus or minus” is the margin of error. The larger the margin of error is, the less likely the results of the study are accurate. The margin of error needs to be included in the methodology section.

- Findings . The findings section is a longer, fleshed-out version of the executive summary that goes into more detail about the statistics uncovered by the research that bolster the study’s findings. If you have related research or secondary data on hand that back up the findings, it can be included to help show the study did what it was designed to do.

- Recommendations . The recommendations section should outline the course of action you think should be taken based on the findings of the research and the purpose of the project. For example, if you conducted a global market research study to identify new locations for stores, make a recommendation for the locations (Mersdorf, 2009).

As we have said, these are the basic sections of a marketing research report. However, additional sections can be added as needed. For example, you might need to add a section on the competition and each firm’s market share. If you’re trying to decide on different supply chain options, you will need to include a section on that topic.

As you write the research report, keep your audience in mind. Don’t use technical jargon decision makers and other people reading the report won’t understand. If technical terms must be used, explain them. Also, proofread the document to ferret out any grammatical errors and typos, and ask a couple of other people to proofread behind you to catch any mistakes you might have missed. If your research report is riddled with errors, its credibility will be undermined, even if the findings and recommendations you make are extremely accurate.

Many research reports are presented via PowerPoint. If you’re asked to create a slideshow presentation from the report, don’t try to include every detail in the report on the slides. The information will be too long and tedious for people attending the presentation to read through. And if they do go to the trouble of reading all the information, they probably won’t be listening to the speaker who is making the presentation.

Instead of including all the information from the study in the slides, boil each section of the report down to key points and add some “talking points” only the presenter will see. After or during the presentation, you can give the attendees the longer, paper version of the report so they can read the details at a convenient time, if they choose to.

Key Takeaway

Step 1 in the marketing research process is to define the problem. Businesses take a look at what they believe are symptoms and try to drill down to the potential causes so as to precisely define the problem. The next task for the researcher is to put into writing the research objective, or goal, the research is supposed to accomplish. Step 2 in the process is to design the research. The research design is the “plan of attack.” It outlines what data you are going to gather, from whom, how, and when, and how you’re going to analyze it once it has been obtained. Step 3 is to design the data-collection forms, which need to be standardized so the information gathered on each is comparable. Surveys are a popular way to gather data because they can be easily administered to large numbers of people fairly quickly. However, to produce the best results, survey questionnaires need to be carefully designed and pretested before they are used. Step 4 is drawing the sample, or a subset of potential buyers who are representative of your entire target market. If the sample is not correctly selected, the research will be flawed. Step 5 is to actually collect the data, whether it’s collected by a person face-to-face, over the phone, or with the help of computers or the Internet. The data-collection process is often different in foreign countries. Step 6 is to analyze the data collected for any obvious errors, tabulate the data, and then draw conclusions from it based on the results. The last step in the process, Step 7, is writing the research report and presenting the findings to decision makers.

Review Questions

- Explain why it’s important to carefully define the problem or opportunity a marketing research study is designed to investigate.

- Describe the different types of problems that can occur when marketing research professionals develop questions for surveys.

- How does a probability sample differ from a nonprobability sample?

- What makes a marketing research study valid? What makes a marketing research study reliable?

- What sections should be included in a marketing research report? What is each section designed to do?

1 “Questionnaire Design,” QuickMBA , http://www.quickmba.com/marketing/research/qdesign (accessed December 14, 2009).

Barnes, B., “Disney Expert Uses Science to Draw Boy Viewers,” New York Times , April 15, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/14/arts/television/14boys.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1 (accessed December 14, 2009).

Burns A. and Ronald Bush, Marketing Research , 6th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2010), 85.

Malhotra, N., Marketing Research: An Applied Approach , 6th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall), 764.

McDaniel, C. D. and Roger H. Gates, Marketing Research Essentials , 2nd ed. (Cincinnati: South-Western College Publishing, 1998), 61.

McWilliams, J., “A-B Puts Super-Low-Calorie Beer in Ring with Miller,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch , August 16, 2009, http://www.stltoday.com/business/next-matchup-light-weights-a-b-puts-super-low-calorie/article_47511bfe-18ca-5979-bdb9-0526c97d4edf.html (accessed April 13, 2012).

Mersdorf, S., “How to Organize Your Next Survey Report,” Cvent , August 24, 2009, http://survey.cvent.com/blog/cvent-survey/0/0/how-to-organize-your-next-survey-report (accessed December 14, 2009).

Rappeport A. and David Gelles, “Facebook to Form Alliance with Nielsen,” Financial Times , September 23, 2009, 16.

Spangler, T., “Disney Lab Tracks Feelings,” Multichannel News 30, no. 30 (August 3, 2009): 26.

Wagner, J., “Marketing in Second Life Doesn’t Work…Here Is Why!” GigaOM , April 4, 2007, http://gigaom.com/2007/04/04/3-reasons-why-marketing-in-second-life-doesnt-work (accessed December 14, 2009).

Wrenn, B., Robert E. Stevens, and David L. Loudon, Marketing Research: Text and Cases , 2nd ed. (Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press, 2007), 180.

Zouhali-Worrall, M., “Found in Translation: Avoiding Multilingual Gaffes,” CNNMoney.com , July 14, 2008, http://money.cnn.com/2008/07/07/smallbusiness/language_translation.fsb/index.htm (accessed December 14, 2009).

Principles of Marketing Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Module 6: Marketing Information and Research

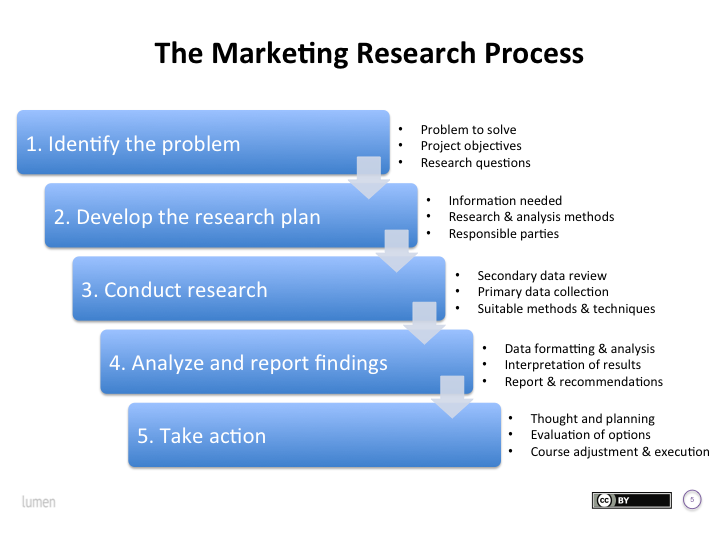

The marketing research process, learning objectives.

- Identify the steps of conducting a marketing research project

A Standard Approach to Research Inquiries

Marketing research is a useful and necessary tool for helping marketers and an organization’s executive leadership make wise decisions. Carrying out marketing research can involve highly specialized skills that go deeper than the information outlined in this module. However, it is important for any marketer to be familiar with the basic procedures and techniques of marketing research.

It is very likely that at some point a marketing professional will need to supervise an internal marketing research activity or to work with an outside marketing research firm to conduct a research project. Managers who understand the research function can do a better job of framing the problem and critically appraising the proposals made by research specialists. They are also in a better position to evaluate their findings and recommendations.

Periodically marketers themselves need to find solutions to marketing problems without the assistance of marketing research specialists inside or outside the company. If you are familiar with the basic procedures of marketing research, you can supervise and even conduct a reasonably satisfactory search for the information needed.

Step 1: Identify the Problem

The first step for any marketing research activity is to clearly identify and define the problem you are trying to solve. You start by stating the marketing or business problem you need to address and for which you need additional information to figure out a solution. Next, articulate the objectives for the research: What do you want to understand by the time the research project is completed? What specific information, guidance, or recommendations need to come out of the research in order to make it a worthwhile investment of the organization’s time and money?

It’s important to share the problem definition and research objectives with other team members to get their input and further refine your understanding of the problem and what is needed to solve it. At times, the problem you really need to solve is not the same problem that appears on the surface. Collaborating with other stakeholders helps refine your understanding of the problem, focus your thinking, and prioritize what you hope to learn from the research. Prioritizing your objectives is particularly helpful if you don’t have the time or resources to investigate everything you want.

To flesh out your understanding of the problem, it’s useful to begin brainstorming actual research questions you want to explore. What are the questions you need to answer in order to get to the research outcomes? What is the missing information that marketing research will help you find? The goal at this stage is to generate a set of preliminary, big-picture questions that will frame your research inquiry. You will revisit these research questions later in the process, but when you’re getting started, this exercise helps clarify the scope of the project, whom you need to talk to, what information may already be available, and where to look for the information you don’t yet have.

Applied Example: Marketing Research for Bookends

To illustrate the marketing research process, let’s return to Uncle Dan and his ailing bookstore, Bookends. You need a lot of information if you’re going to help Dan turn things around, so marketing research is a good idea. You begin by identifying the problem and then work to set down your research objectives and initial research questions:

| Identifying Problems, Objectives, and Questions | |

|---|---|

| Core business problem Dan needs to solve | How to get more people to spend more money at Bookends |

| Research objectives | 1) Identify promising target audiences for Bookends; 2) Identify strategies for rapidly increasing revenue from these target audiences |

| Initial research questions | Who are Bookends’ current customers? How much do they spend? Why do they come to Bookends? What do they wish Bookends offered? Who isn’t coming to Bookends, and why? |

Step 2: Develop a Research Plan

Once you have a problem definition, research objectives, and a preliminary set of research questions, the next step is to develop a research plan. Essential to this plan is identifying precisely what information you need to answer your questions and achieve your objectives. Do you need to understand customer opinions about something? Are you looking for a clearer picture of customer needs and related behaviors? Do you need sales, spending, or revenue data? Do you need information about competitors’ products, or insight about what will make prospective customers notice you? When do need the information, and what’s the time frame for getting it? What budget and resources are available?

Once you have clarified what kind of information you need and the timing and budget for your project, you can develop the research design. This details how you plan to collect and analyze the information you’re after. Some types of information are readily available through secondary research and secondary data sources. Secondary research analyzes information that has already been collected for another purpose by a third party, such as a government agency, an industry association, or another company. Other types of information need to from talking directly to customers about your research questions. This is known as primary research , which collects primary data captured expressly for your research inquiry. Marketing research projects may include secondary research, primary research, or both.

Depending on your objectives and budget, sometimes a small-scale project will be enough to get the insight and direction you need. At other times, in order to reach the level of certainty or detail required, you may need larger-scale research involving participation from hundreds or even thousands of individual consumers. The research plan lays out the information your project will capture—both primary and secondary data—and describes what you will do with it to get the answers you need. (Note: You’ll learn more about data collection methods and when to use them later in this module.)

Your data collection plan goes hand in hand with your analysis plan. Different types of analysis yield different types of results. The analysis plan should match the type of data you are collecting, as well as the outcomes your project is seeking and the resources at your disposal. Simpler research designs tend to require simpler analysis techniques. More complex research designs can yield powerful results, such as understanding causality and trade-offs in customer perceptions. However, these more sophisticated designs can require more time and money to execute effectively, both in terms of data collection and analytical expertise.

The research plan also specifies who will conduct the research activities, including data collection, analysis, interpretation, and reporting on results. At times a singlehanded marketing manager or research specialist runs the entire research project. At other times, a company may contract with a marketing research analyst or consulting firm to conduct the research. In this situation, the marketing manager provides supervisory oversight to ensure the research delivers on expectations.

Finally, the research plan indicates who will interpret the research findings and how the findings will be reported. This part of the research plan should consider the internal audience(s) for the research and what reporting format will be most helpful. Often, senior executives are primary stakeholders, and they’re anxious for marketing research to inform and validate their choices. When this is the case, getting their buy-in on the research plan is recommended to make sure that they are comfortable with the approach and receptive to the potential findings.

Applied Example: A Bookends Research Plan

You talk over the results of your problem identification work with Dan. He thinks you’re on the right track and wants to know what’s next. You explain that the next step is to put together a detailed plan for getting answers to the research questions.

Dan is enthusiastic, but he’s also short on money. You realize that such a financial constraint will limit what’s possible, but with Dan’s help you can do something worthwhile. Below is the research plan you sketch out:

| Identifying Data Types, Timing and Budget, Data Collection Methods, Analysis, and Interpretation | |

|---|---|

| Types of data needed | 1) Demographics and attitudes of current Bookends customers; 2) current customers’ spending patterns; 3) metro area demographics (to determine types of people who aren’t coming to the store) |

| Timing & budget | Complete project within 1 month; no out-of-pocket spending |

| Data collection methods | 1) Current customer survey using free online survey tool, 2) store sales data mapped to customer survey results, 3) free U.S. census data on metro-area demographics, 4) 8–10 intercept (“man on the street”) interviews with non-customers |

| Analysis plan | Use Excel or Google Sheets to tabulate data; Marina (statistician cousin) to assist in identifying data patterns that could become market segments |

| Interpretation and reporting | You and Dan will work together to comb through the data and see what insights it produces. You’ll use PowerPoint to create a report that lays out significant results, key findings, and recommendations. |

Step 3: Conduct the Research

Conducting research can be a fun and exciting part of the marketing research process. After struggling with the gaps in your knowledge of market dynamics—which led you to embark on a marketing research project in the first place—now things are about to change. Conducting research begins to generate information that helps answer your urgent marketing questions.

Typically data collection begins by reviewing any existing research and data that provide some information or insight about the problem. As a rule, this is secondary research. Prior research projects, internal data analyses, industry reports, customer-satisfaction survey results, and other information sources may be worthwhile to review. Even though these resources may not answer your research questions fully, they may further illuminate the problem you are trying to solve. Secondary research and data sources are nearly always cheaper than capturing new information on your own. Your marketing research project should benefit from prior work wherever possible.

After getting everything you can from secondary research, it’s time to shift attention to primary research, if this is part of your research plan. Primary research involves asking questions and then listening to and/or observing the behavior of the target audience you are studying. In order to generate reliable, accurate results, it is important to use proper scientific methods for primary research data collection and analysis. This includes identifying the right individuals and number of people to talk to, using carefully worded surveys or interview scripts, and capturing data accurately.

Without proper techniques, you may inadvertently get bad data or discover bias in the responses that distorts the results and points you in the wrong direction. The module on Marketing Research Techniques discusses these issues in further detail, since the procedures for getting reliable data vary by research method.

Applied Example: Getting the Data on Bookends

Dan is on board with the research plan, and he’s excited to dig into the project. You start with secondary data, getting a dump of Dan’s sales data from the past two years, along with related information: customer name, zip code, frequency of purchase, gender, date of purchase, and discounts/promotions (if any).

You visit the U.S. Census Bureau Web site to download demographic data about your metro area. The data show all zip codes in the area, along with population size, gender breakdown, age ranges, income, and education levels.

The next part of the project is customer-survey data. You work with Dan to put together a short survey about customer attitudes toward Bookends, how often and why they come, where else they spend money on books and entertainment, and why they go other places besides Bookends. Dan comes up with the great idea of offering a 5 percent discount coupon to anyone who completes the survey. Although it eats into his profits, this scheme gets more people to complete the survey and buy books, so it’s worth it.

For a couple of days, you and Dan take turns doing “man on the street” interviews (you interview the guy in the red hat, for instance). You find people who say they’ve never been to Bookends and ask them a few questions about why they haven’t visited the store, where else they buy books and other entertainment, and what might get them interested in visiting Bookends sometime. This is all a lot of work, but for a zero-budget project, it’s coming together pretty well.

Step 4: Analyze and Report Findings

Analyzing the data obtained in a market survey involves transforming the primary and/or secondary data into useful information and insights that answer the research questions. This information is condensed into a format to be used by managers—usually a presentation or detailed report.

Analysis starts with formatting, cleaning, and editing the data to make sure that it’s suitable for whatever analytical techniques are being used. Next, data are tabulated to show what’s happening: What do customers actually think? What’s happening with purchasing or other behaviors? How do revenue figures actually add up? Whatever the research questions, the analysis takes source data and applies analytical techniques to provide a clearer picture of what’s going on. This process may involve simple or sophisticated techniques, depending on the research outcomes required. Common analytical techniques include regression analysis to determine correlations between factors; conjoint analysis to determine trade-offs and priorities; predictive modeling to anticipate patterns and causality; and analysis of unstructured data such as Internet search terms or social media posts to provide context and meaning around what people say and do.

Good analysis is important because the interpretation of research data—the “so what?” factor—depends on it. The analysis combs through data to paint a picture of what’s going on. The interpretation goes further to explain what the research data mean and make recommendations about what managers need to know and do based on the research results. For example, what is the short list of key findings and takeaways that managers should remember from the research? What are the market segments you’ve identified, and which ones should you target? What are the primary reasons your customers choose your competitor’s product over yours, and what does this mean for future improvements to your product?

Individuals with a good working knowledge of the business should be involved in interpreting the data because they are in the best position to identify significant insights and make recommendations from the research findings. Marketing research reports incorporate both analysis and interpretation of data to address the project objectives.

The final report for a marketing research project may be in written form or slide-presentation format, depending on organizational culture and management preferences. Often a slide presentation is the preferred format for initially sharing research results with internal stakeholders. Particularly for large, complex projects, a written report may be a better format for discussing detailed findings and nuances in the data, which managers can study and reference in the future.

Applied Example: Analysis and Insights for Bookends

Getting the data was a bit of a hassle, but now you’ve got it, and you’re excited to see what it reveals. Your statistician cousin, Marina, turns out to be a whiz with both the sales data and the census data. She identified several demographic profiles in the metro area that looked a lot like lifestyle segments. Then she mapped Bookends’ sales data into those segments to show who is and isn’t visiting Bookends. After matching customer-survey data to the sales data, she broke down the segments further based on their spending levels and reasons they visit Bookends.

Gradually a clearer picture of Bookends’ customers is beginning to emerge: who they are, why they come, why they don’t come, and what role Bookends plays in their lives. Right away, a couple of higher-priority segments—based on their spending levels, proximity, and loyalty to Bookends—stand out. You and your uncle are definitely seeing some possibilities for making the bookstore a more prominent part of their lives. You capture these insights as “recommendations to be considered” while you evaluate the right marketing mix for each of the new segments you’d like to focus on.

Step 5: Take Action

Once the report is complete, the presentation is delivered, and the recommendations are made, the marketing research project is over, right? Wrong.

What comes next is arguably the most important step of all: taking action based on your research results.

If your project has done a good job interpreting the findings and translating them into recommendations for the marketing team and other areas of the business, this step may seem relatively straightforward. When the research results validate a path the organization is already on, the “take action” step can galvanize the team to move further and faster in that same direction.

Things are not so simple when the research results indicate a new direction or a significant shift is advisable. In these cases, it’s worthwhile to spend time helping managers understand the research, explain why it is wise to shift course, and explain how the business will benefit from the new path. As with any important business decision, managers must think deeply about the new approach and carefully map strategies, tactics, and available resources to plan effectively. By making the results available and accessible to managers and their execution teams, the marketing research project can serve as an ongoing guide and touchstone to help the organization plan, execute, and adjust course as it works toward desired goals and outcomes.