- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did American literature begin?

- Who are some important authors of American literature?

- What are the periods of American literature?

Langston Hughes

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Annenberg Learner - Langston Hughes (1902-1967)

- My Hero - Langston Hughes

- The Poetry Archive - Biography of Langston Hughes

- Case Western Reserve University - Encyclopedia of Cleveland History - Langston Hughes

- All Poetry - Biography of Langston Hughes

- Historic Missourians - Langston Hughes

- Lehigh University Scalar - Langston Hughes: Poems, Biography, and Timeline of his early career

- Black Past - Langston Hughes

- Poetry Foundation - Biography of Langston Hughes

- Poets.org - Langston Hughes

- Langston Hughes - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Langston Hughes - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Langston Hughes (born February 1, 1902?, Joplin , Missouri , U.S.—died May 22, 1967, New York , New York) was an American writer who was an important figure in the Harlem Renaissance and made the African American experience the subject of his writings, which ranged from poetry and plays to novels and newspaper columns.

While it was long believed that Hughes was born in 1902, new research released in 2018 indicated that he might have been born the previous year. His parents separated soon after his birth, and he was raised by his mother and grandmother. After his grandmother’s death, he and his mother moved to half a dozen cities before reaching Cleveland, where they settled. He wrote the poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” the summer after his graduation from high school in Cleveland; it was published in The Crisis in 1921 and brought him considerable attention. After attending Columbia University in New York City in 1921–22, he explored Harlem , forming a permanent attachment to what he called the “great dark city,” and worked as a steward on a freighter bound for Africa. Back in New York City from seafaring and sojourning in Europe, he met in 1924 the writers Arna Bontemps and Carl Van Vechten , with whom he would have lifelong influential friendships. Hughes won an Opportunity magazine poetry prize in 1925. That same year, Van Vechten introduced Hughes’s poetry to the publisher Alfred A. Knopf , who accepted the collection that Knopf would publish as The Weary Blues in 1926.

(Read W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1926 Britannica essay on African American literature.)

While working as a busboy in a hotel in Washington, D.C. , in late 1925, Hughes put three of his own poems beside the plate of Vachel Lindsay in the dining room. The next day, newspapers around the country reported that Lindsay, among the most popular white poets of the day, had “discovered” an African American busboy poet, which earned Hughes broader notice. Hughes received a scholarship to, and began attending, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in early 1926. That same year, he received the Witter Bynner Undergraduate Poetry Award, and he published “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” in The Nation , a manifesto in which he called for a confident, uniquely Black literature:

We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either.

By the time Hughes received his degree in 1929, he had helped launch the influential magazine Fire!! , in 1926, and he had also published a second collection of poetry, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927), which was criticized by some for its title and for its frankness, though Hughes himself felt that it represented another step forward in his writing.

A few months after Hughes’s graduation, Not Without Laughter (1930), his first prose volume, had a cordial reception. In the 1930s he turned his poetry more forcefully toward racial justice and political radicalism. He traveled in the American South in 1931 and decried the Scottsboro case ; he then traveled widely in the Soviet Union , Haiti, Japan , and elsewhere and served as a newspaper correspondent (1937) during the Spanish Civil War . He published a collection of short stories, The Ways of White Folks (1934), and became deeply involved in theatre. His play Mulatto , adapted from one of his short stories, premiered on Broadway in 1935, and productions of several other plays followed in the late 1930s. He also founded theatre companies in Harlem (1937) and Los Angeles (1939). In 1940 Hughes published The Big Sea , his autobiography up to age 28. A second volume of autobiography, I Wonder As I Wander , was published in 1956.

(Read Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s Britannica essay on "Monuments of Hope.")

Hughes documented African American literature and culture in works such as A Pictorial History of the Negro in America (1956) and the anthologies The Poetry of the Negro (1949) and The Book of Negro Folklore (1958; with Bontemps). He continued to write numerous works for the stage, including the lyrics for Street Scene , an opera with music by Kurt Weill that premiered in 1947. Black Nativity (1961; film 2013) is a gospel play that uses Hughes’s poetry, along with gospel standards and scriptural passages, to retell the story of the birth of Jesus . It was an international success, and performances of the work—often diverging substantially from the original—became a Christmas tradition in many Black churches and cultural centres. He also wrote poetry until his death; The Panther and the Lash , published posthumously in 1967, reflected and engaged with the Black Power movement and, specifically, the Black Panther Party , which was founded the previous year.

Among his other writings, Hughes translated the poetry of Federico García Lorca and Gabriela Mistral . He was also widely known for his comic character Jesse B. Semple, familiarly called Simple, who appeared in Hughes’s columns in the Chicago Defender and the New York Post and later in book form and on the stage. The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes , edited by Arnold Rampersad and David Roessel, appeared in 1994. Some of his political exchanges were collected as Letters from Langston: From the Harlem Renaissance to the Red Scare and Beyond (2016).

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Langston Hughes

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 15, 2023 | Original: January 24, 2023

Langston Hughes was a defining figure of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance as an influential poet, playwright, novelist, short story writer, essayist, political commentator and social activist. Known as a poet of the people, his work focused on the everyday lives of the Black working class, earning him renown as one of America’s most notable poets.

Hughes was born February 1, 1902 (although some evidence shows it may have been 1901 ), in Joplin, Missouri, to James and Caroline Hughes. When he was a young boy, his parents divorced, and, after his father moved to Mexico, and his mother, whose maiden name was Langston, sought work elsewhere, he was raised by his grandmother, Mary Langston, in Lawrence, Kansas. Mary Langston died when Hughes was around 12 years old, and he relocated to Illinois to live with his mother and stepfather. The family eventually landed in Cleveland.

According to the first volume of his 1940 autobiography, The Big Sea , which chronicled his life until the age of 28, Hughes said he often used reading to combat loneliness while growing up. “I began to believe in nothing but books and the wonderful world in books—where if people suffered, they suffered in beautiful language, not in monosyllables, as we did in Kansas,” he wrote.

In his Ohio high school, he started writing poetry, focusing on what he called “low-down folks” and the Black American experience. He would later write that he was influenced at a young age by Carl Sandburg, Walt Whitman and Paul Laurence Dunbar. Upon graduating in 1920, he traveled to Mexico to live with his father for a year. It was during this period that, still a teenager, he wrote “ The Negro Speaks of Rivers ,” a free-verse poem that ran in the NAACP ’s The Crisis magazine and garnered him acclaim. It read, in part:

“I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

6 Key Figures of the Harlem Renaissance’s Queer Scene

Harlem in the 1920s and '30s offered the Black creative class a sense of pride and possibility. It also had cross‑dressing blues singers, extravagant drag balls and literary and artistic salons.

7 Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

These writers were part of the larger cultural movement centered in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood and offered complex portraits of Black life in America.

How 19th‑Century Drag Balls Evolved into House Balls, Birthplace of Voguing

Harlem drag balls thrived during the post‑Civil War era, creating a space where trans and queer people of color later broke out to develop House Ballroom.

Traveling the World

Hughes returned from Mexico and spent one year studying at Columbia University in New York City . He didn’t love the experience, citing racism, but he became immersed in the burgeoning Harlem cultural and intellectual scene, a period now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Hughes worked several jobs over the next several years, including cook, elevator operator and laundry hand. He was employed as a steward on a ship, traveling to Africa and Europe, and lived in Paris, mingling with the expat artist community there, before returning to America and settling down in Washington, D.C. It was in the nation’s capital that, while working as a busboy, he slipped his poetry to the noted poet Vachel Lindsay, cited as the father of modern singing poetry, who helped connect Hughes to the literary world.

Hughes’ first book of poetry, The Weary Blues was published in 1926, and he received a scholarship to and, in 1929, graduated from, Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University. He soon published Not Without Laughter , his first novel, which was awarded the Harmon Gold Medal for literature.

Jazz Poetry

Called the “Poet Laureate of Harlem,” he is credited as the father of jazz poetry, a literary genre influenced by or sounding like jazz, with rhythms and phrases inspired by the music.

“But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile,” he wrote in the 1926 essay, “ The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain .”

Writing for a general audience, his subject matter continued to focus on ordinary Black Americans. Hughes wrote that his 1927 work, “Fine Clothes to the Jew,” was about “workers, roustabouts, and singers, and job hunters on Lenox Avenue in New York, or Seventh Street in Washington or South State in Chicago—people up today and down tomorrow, working this week and fired the next, beaten and baffled, but determined not to be wholly beaten, buying furniture on the installment plan, filling the house with roomers to help pay the rent, hoping to get a new suit for Easter—and pawning that suit before the Fourth of July."

He also did not shy from writing about his experiences and observations.

“We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame,” he wrote in the The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain . “If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.”

Ever the traveler, Hughes spent time in the South, chronicling racial injustices, and also the Soviet Union in the 1930s, showing an interest in communism . (He was called to testify before Congress during the McCarthy hearings in 1953.)

In 1930, Hughes wrote “Mule Bone” with Zora Neale Hurston , his first play, which would be the first of many. “Mulatto: A Tragedy of the Deep South,” about race issues, was Broadway’s longest-running play written by a Black author until Lorraine Hansberry’s 1958 play, “A Raisin in the Sun.” Hansberry based the name of her play on Hughes’ 1951 poem, “ Harlem ” in which he writes,

"What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?...”

Hughes wrote the lyrics for “Street Scene,” a 1947 Broadway musical, and set up residence in a Harlem brownstone on East 127th Street. He co-founded the New York Suitcase Theater, as well as theater troupes in Los Angeles and Chicago. He attempted screenwriting in Hollywood, but found racism blocked his efforts.

He worked as a newspaper war correspondent in 1937 for the Baltimore Afro American , writing about Black American soldiers fighting for the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War . He also wrote a column from 1942-1962 for the Chicago Defender , a Black newspaper, focusing on Jim Crow laws and segregation , World War II and the treatment of Black people in America. The column often featured the fictitious Jesse B. Semple, known as Simple.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Hughes wrote a “First Book” series of children's books, patriotic stories about Black culture and achievements, including The First Book of Negroes (1952), The First Book of Jazz (1955), and The Book of Negro Folklore (1958). Among the stories in the 1958 volume is "Thank You, Ma'am," in which a young teenage boy learns a lesson about trust and respect when an older woman he tries to rob ends up taking him home and giving him a meal.

Hughes died in New York from complications during surgery to treat prostate cancer on May 22, 1967, at the age of 65. His ashes are interred in Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. His Harlem home was named a New York landmark in 1981, and a National Register of Places a year later.

"I, too, am America," a quote from his 1926 poem, " I, too, " is engraved on the wall of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“ Langston Hughes ,” The Library of Congress

“ Langston Hughes: The People's Poet ,” Smithsonian Magazine

“ The Blues and Langston Hughes ,” Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

“ Langston Hughes ,” Poets.org

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

(1926) langston hughes, “the negro artist and the racial mountain”.

One of the most promising of the young Negro poets said to me once, “I want to be a poet—not a Negro poet,” meaning, I believe, “I want to write like a white poet”; meaning subconsciously, “I would like to be a white poet”; meaning behind that, “I would like to be white.” And I was sorry the young man said that, for no great poet has ever been afraid of being himself. And I doubted then that, with his desire to run away spiritually from his race, this boy would ever be a great poet. But this is the mountain standing in the way of any true Negro art in America—this urge within the race toward whiteness, the desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of American standardization, and to be as little Negro and as much American as possible.

But let us look at the immediate background of this young poet. His family is of what I suppose one would call the Negro middle class: people who are by no means rich yet never uncomfortable nor hungry—smug, contented, respectable folk, members of the Baptist church. The father goes to work every morning. He is a chief steward at a large white club. The mother sometimes does fancy sewing or supervises parties for the rich families of the town. The children go to a mixed school. In the home they read white papers and magazines. And the mother often says “Don’t be like niggers” when the children are bad. A frequent phrase from the father is, “Look how well a white man does things.” And so the word white comes to be unconsciously a symbol of all virtues. It holds for the children beauty, morality, and money. The whisper of “I want to be white” runs silently through their minds. This young poet’s home is, I believe, a fairly typical home of the colored middle class. One sees immediately how difficult it would be for an artist born in such a home to interest himself in interpreting the beauty of his own people. He is never taught to see that beauty. He is taught rather not to see it, or if he does, to be ashamed of it when it is not according to Caucasian patterns.

For racial culture the home of a self-styled “high-class” Negro has nothing better to offer. Instead there will perhaps be more aping of things white than in a less cultured or less wealthy home. The father is perhaps a doctor, lawyer, landowner, or politician. The mother may be a social worker, or a teacher, or she may do nothing and have a maid. Father is often dark but he has usually married the lightest woman he could find. The family attend a fashionable church where few really colored faces are to be found. And they themselves draw a color line. In the North they go to white theaters and white movies. And in the South they have at least two cars and house “like white folks.” Nordic manners, Nordic faces, Nordic hair, Nordic art (if any), and an Episcopal heaven. A very high mountain indeed for the would-be racial artist to climb in order to discover himself and his people.

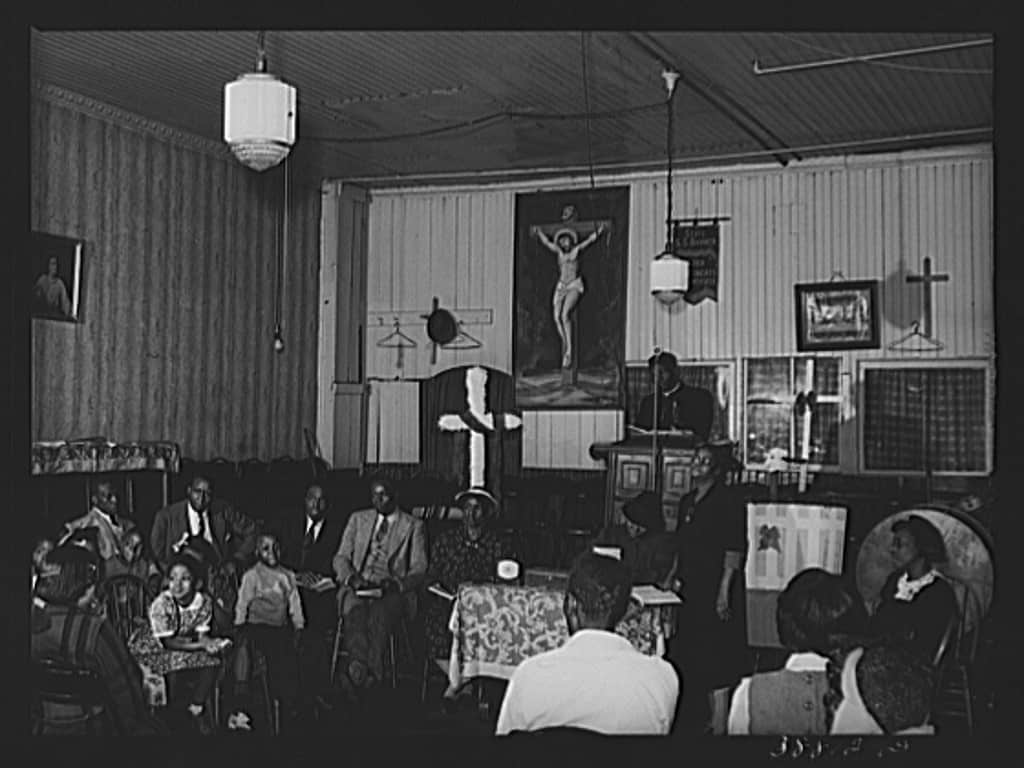

But then there are the low-down folks, the so-called common element, and they are the majority—may the Lord be praised! The people who have their hip of gin on Saturday nights and are not too important to themselves or the community, or too well fed, or too learned to watch the lazy world go round. They live on Seventh Street in Washington or State Street in Chicago and they do not particularly care whether they are like white folks or anybody else. Their joy runs, bang! into ecstasy. Their religion soars to a shout. Work maybe a little today, rest a little tomorrow. Play awhile. Sing awhile. O, let’s dance! These common people are not afraid of spirituals, as for a long time their more intellectual brethren were, and jazz is their child. They furnish a wealth of colorful, distinctive material for any artist because they still hold their own individuality in the face of American standardizations. And perhaps these common people will give to the world its truly great Negro artist, the one who is not afraid to be himself. Whereas the better-class Negro would tell the artist what to do, the people at least let him alone when he does appear. And they are not ashamed of him—if they know he exists at all. And they accept what beauty is their own without question.

Certainly there is, for the American Negro artist who can escape the restrictions the more advanced among his own group would put upon him, a great field of unused material ready for his art. Without going outside his race, and even among the better classes with their “white” culture and conscious American manners, but still Negro enough to be different, there is sufficient matter to furnish a black artist with a lifetime of creative work. And when he chooses to touch on the relations between Negroes and whites in this country, with their innumerable overtones and undertones surely, and especially for literature and the drama, there is an inexhaustible supply of themes at hand. To these the Negro artist can give his racial individuality, his heritage of rhythm and warmth, and his incongruous humor that so often, as in the Blues, becomes ironic laughter mixed with tears. But let us look again at the mountain.

A prominent Negro clubwoman in Philadelphia paid eleven dollars to hear Raquel Meller sing Andalusian popular songs. But she told me a few weeks before she would not think of going to hear “that woman,” Clara Smith, a great black artist, sing Negro folksongs. And many an upper-class Negro church, even now, would not dream of employing a spiritual in its services. The drab melodies in white folks’ hymnbooks are much to be preferred. “We want to worship the Lord correctly and quietly. We don’t believe in ‘shouting.’ Let’s be dull like the Nordics,” they say, in effect.

The road for the serious black artist, then, who would produce a racial art is most certainly rocky and the mountain is high. Until recently he received almost no encouragement for his work from either white or colored people. The fine novels of Chesnutt go out of print with neither race noticing their passing. The quaint charm and humor of Dunbar’s’ dialect verse brought to him, in his day, largely the same kind of encouragement one would give a sideshow freak (A colored man writing poetry! How odd!) or a clown (How amusing!).

The present vogue in things Negro, although it may do as much harm as good for the budding artist, has at least done this: it has brought him forcibly to the attention of his own people among whom for so long, unless the other race had noticed him beforehand, he was a prophet with little honor.

The Negro artist works against an undertow of sharp criticism and misunderstanding from his own group and unintentional bribes from the whites. “Oh, be respectable, write about nice people, show how good we are,” say the Negroes. “Be stereotyped, don’t go too far, don’t shatter our illusions about you, don’t amuse us too seriously. We will pay you,” say the whites. Both would have told Jean Toomer not to write Cane. The colored people did not praise it. The white people did not buy it. Most of the colored people who did read Cane hate it. They are afraid of it. Although the critics gave it good reviews the public remained indifferent. Yet (excepting the work of Du Bois) Cane contains the finest prose written by a Negro in America. And like the singing of Robeson, it is truly racial.

But in spite of the Nordicized Negro intelligentsia and the desires of some white editors we have an honest American Negro literature already with us. Now I await the rise of the Negro theater. Our folk music, having achieved world-wide fame, offers itself to the genius of the great individual American composer who is to come. And within the next decade I expect to see the work of a growing school of colored artists who paint and model the beauty of dark faces and create with new technique the expressions of their own soul-world. And the Negro dancers who will dance like flame and the singers who will continue to carry our songs to all who listen-they will be with us in even greater numbers tomorrow.

Most of my own poems are racial in theme and treatment, derived from the life I know. In many of them I try to grasp and hold some of the meanings and rhythms of jazz. I am as sincere as I know how to be in these poems and yet after every reading I answer questions like these from my own people: Do you think Negroes should always write about Negroes? I wish you wouldn’t read some of your poems to white folks. How do you find anything interesting in a place like a cabaret? Why do you write about black people? You aren’t black. What makes you do so many jazz poems?

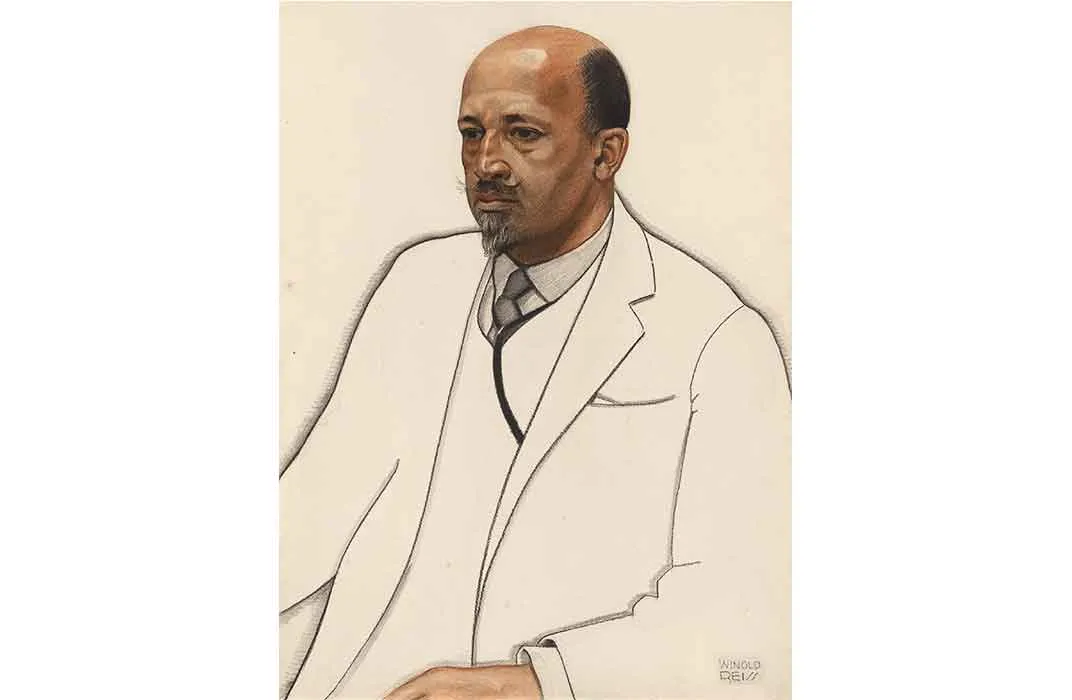

But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile. Yet the Philadelphia clubwoman is ashamed to say that her race created it and she does not like me to write about it, The old subconscious “white is best” runs through her mind. Years of study under white teachers, a lifetime of white books, pictures, and papers, and white manners, morals, and Puritan standards made her dislike the spirituals. And now she turns up her nose at jazz and all its manifestations—likewise almost everything else distinctly racial. She doesn’t care for the Winold Reiss’ portraits of Negroes because they are “too Negro.” She does not want a true picture of herself from anybody. She wants the artist to flatter her, to make the white world believe that all negroes are as smug and as near white in soul as she wants to be. But, to my mind, it is the duty of the younger Negro artist, if he accepts any duties at all from outsiders, to change through the force of his art that old whispering “I want to be white,” hidden in the aspirations of his people, to “Why should I want to be white? I am a Negro—and beautiful”?

So I am ashamed for the black poet who says, “I want to be a poet, not a Negro poet,” as though his own racial world were not as interesting as any other world. I am ashamed, too, for the colored artist who runs from the painting of Negro faces to the painting of sunsets after the manner of the academicians because he fears the strange unwhiteness of his own features. An artist must be free to choose what he does, certainly, but he must also never be afraid to do what he must choose.

Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing the Blues penetrate the closed ears of the colored near intellectuals until they listen and perhaps understand. Let Paul Robeson singing “Water Boy,” and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem, and Jean Toomer holding the heart of Georgia in his hands, and Aaron Douglas’s drawing strange black fantasies cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty. We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.

THE NATION, 1926

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes (1901–1967) was a poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, columnist, and a significant figure of the Harlem Renaissance.

Born in Joplin, Missouri, Hughes was the descendant of enslaved African American women and white slave owners in Kentucky. He attended high school in Cleveland, Ohio, where he wrote his first poetry, short stories, and dramatic plays. After a short time in New York, he spent the early 1920s traveling through West Africa and Europe, living in Paris and England.

Hughes returned to the United States in 1924 and to Harlem after graduating from Lincoln University in 1929. His first poem was published in 1921 in The Crisis and he published his first book of poetry, T he Weary Blues in 1926. Hughes’s influential work focused on a racial consciousness devoid of hate. In 1926, he published what would be considered a manifesto of the Harlem Renaissance in The Nation : “The younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly, too. The tom-tom cries, and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn't matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain free within ourselves.”

Portrait of Langston Hughes , ca. 1960.

Photograph by Louis H. Draper

Hughes penned novels, short stories, plays, operas, essays, works for children, and an autobiography. Hughes’s sexuality is debated by scholars, with some finding homosexual codes and unpublished poems to an alleged black male lover to indicate he was homosexual. His primary biographer, Arnold Rampersad, notes that Hughes exhibited a preference for African American men in his work and his life, but was likely asexual.

View objects relating to Langston Hughes

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Elusive Langston Hughes

By the time the British artist Isaac Julien’s iconic short essay-film “Looking for Langston” was released, in 1989, Julien’s ostensible subject, the enigmatic poet and race man Langston Hughes, had been dead for twenty-two years, but the search for his “real” story was still ongoing. There was a sense—particularly among gay men of color, like Julien, who had so few “out” ancestors and wanted to claim the prolific, uneven, but significant writer as one of their own—that some essential things about Hughes had been obscured or disfigured in his work and his memoirs. Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, and transplanted to New York City as a strikingly handsome nineteen-year-old, Hughes became, with the publication of his first book of poems, “The Weary Blues” (1926), a prominent New Negro: modern, pluralistic in his beliefs, and a member of what the folklorist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston called “the niggerati,” a loosely formed alliance of black writers and intellectuals that included Hurston, the author and diplomat James Weldon Johnson, the openly gay poet and artist Richard Bruce Nugent, and the novelists Nella Larsen, Jessie Fauset, and Wallace Thurman (whose 1929 novel about color fixation among blacks, “The Blacker the Berry,” conveys some of the energy of the time).

In a 1926 essay for The Nation , “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Hughes described the group, which came together during the Harlem Renaissance, when hanging out uptown was considered a lesson in cool:

We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.

And yet, in his personal life, Hughes did not stand on top of the mountain, proclaiming who he was or what he thought. One of the architects of black political correctness, he saw as threatening any attempt to expose black difference or weakness in front of a white audience. In his approach to the work of other black artists, in particular, he was excessively inclusive, enthusiastic to the point of self-effacement, as if black creativity were a great wave that would wash away the psychic scars of discrimination. Hughes was uncomfortable when younger black writers, such as James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison (whom Hughes mentored from the day after he arrived in Harlem, in 1936, until it was no longer convenient for Ellison to be associated with the less careful craftsman), criticized other black writers. Hughes’s reluctance to reveal the cracks in the black world—which is to say, his own world—curtailed not only what he was able to achieve as an artist but what he was able to express as a man.

Instead of coming to grips with himself and his potential, he developed what he considered to be a palatable or marketable public persona. There he is, smiling, humble, industrious, and hidden, in Arnold Rampersad’s two-volume biography, “The Life of Langston Hughes” (1986 and 1988), not to mention in such important recent works about the period as Carla Kaplan’s “Miss Anne in Harlem” and Farah Jasmine Griffin’s “Harlem Nocturne” (both 2013). Even in much of his own correspondence—in the recently published “The Selected Letters of Langston Hughes,” edited by Rampersad and David Roessel, with Christa Fratantoro—one senses that Hughes is performing a version of himself that he feels is socially acceptable. (While “The Selected Letters” is a good place to start finding out about Hughes and his world, one sees more of his naughtiness and sense of play in some of the narrower collections, including “Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten,” which was edited with verve and insight by Emily Bernard.) The Hughes persona also appears in his most celebrated verses, which marry down-home Southern locutions with urban rhythms. From “The Weary Blues”:

I heard a Negro play. Down on Lenox Avenue the other night By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light He did a lazy sway. . . . He did a lazy sway. . . . To the tune o’ those Weary Blues. With his ebony hands on each ivory key He made that poor piano moan with melody. . . . In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan— “Ain’t got nobody in all this world, Ain’t got nobody but ma self. I’s gwine to quit ma frownin’ And put ma troubles on the shelf.”

Writing about Hughes’s “Selected Poems” in the Times in 1959, Baldwin—who chastised his elder for reducing blackness to a kind of pleasant Negro simplicity—began with a bang:

Every time I read Langston Hughes I am amazed all over again by his genuine gifts—and depressed that he has done so little with them. . . . Hughes, in his sermons, blues and prayers, has working for him the power and the beat of Negro speech and Negro music. Negro speech is vivid largely because it is private. It is a kind of emotional shorthand—or sleight of hand—by means of which Negroes express not only their relationship to each other but their judgment of the white world. . . . Hughes knows the bitter truth behind these hieroglyphics: what they are designed to protect, what they are designed to convey. But he has not forced them into the realm of art, where their meaning would become clear and overwhelming.

Possibly, Baldwin—the author of the landmark gay love story “Giovanni’s Room”—was upset less by Hughes’s failures as a poet than by his refusal to reveal the truth behind his own hieroglyphics: his sexuality, which appears only in glimpses in his work. (And in the work of others, including Richard Bruce Nugent’s 1926 story “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,” which Hughes published in Fire!! , a literary magazine that Wallace Thurman edited, and in which a young man walking in Harlem bumps into “Langston,” who’s in the company of a striking boy.) Thurman, expressing his frustration at how little he knew about Hughes’s private self, wrote to him once, “You are in the final analysis the most consarned and diabolical creature, to say nothing of being either the most egregiously simple or excessively complex person I know.” Even Rampersad’s biography, which is as rich a study of a life as one could wish for, was criticized by gay readers for its emphatic I-don’t-know-anything-specific-about-his-romantic-life pronouncements. In Rampersad’s work, Hughes emerges as a constantly striving, almost asexual entity—which is pretty much the image that Hughes himself put forth.

Reading Hughes’s work, one is reminded of these lines by the black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, one of Hughes’s early enthusiasms:

We wear the mask that grins and lies, It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,— This debt we pay to human guile; With torn and bleeding hearts we smile, And mouth with myriad subtleties.

That mask was what kept Hughes from including such works as “Café: 3 A.M. ” in his “Selected Poems,” which he edited:

Detectives from the vice squad with weary sadistic eyes spotting fairies. Degenerates , some folks say. But God, Nature, or somebody made them that way. Police lady or Lesbian over there? Where?

And where was Langston? His tight-lippedness when it came to his own “degenerate” behavior kept him from identifying such people as “F.S.,” the dedicatee of another poem (who may have been Ferdinand Smith, a Jamaican merchant seaman Hughes met in Harlem) that appeared in “The Weary Blues”:

I loved my friend. He went away from me. There is nothing more to say. The poem ends, Soft as it began— I loved my friend.

Hughes’s genial, generous, and guarded persona was self-protective, certainly. It’s important to remember that he came of age in an era during which gay men—and blacks—were physically and mentally abused for being what they were. (He was self-preserving in other areas of his life as well. To protect his career, he testified at the House Un-American Activities Committee proceedings, which cost him his friendships with W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson.) Hughes’s mask was likely also a bulwark against his personal history, which he rarely discussed, even in his elusive autobiographies, “The Big Sea” (1940) and “I Wonder as I Wander” (1956), one of the most apt titles ever penned by Hughes: his memoir is littered with short sojourns and partings, a pattern he learned in a home where the laughter was often derisive and love was a form of humiliation.

Hughes’s mother, the impulsive and vibrant Carrie Langston, was born in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1873, of African, Native American, and French ancestry. Her father, Charles Langston, an enterprising farmer and grocer, was also a fierce abolitionist, whose youngest brother, John Mercer Langston, became a prominent figure in nineteenth-century black America—a professor of law, a dean, and then the acting president of Howard University. As a girl, Carrie Langston was known as “the Belle of Black Lawrence.” Hungry for attention, she aspired to a career on the stage, but her dreams were stymied by prejudice and by the limits of a nineteenth-century woman’s life. With few real options open to her, she completed a course in elementary-school education, and in 1898, already in love with travel, moved to Guthrie, in the Oklahoma Territory, some ten miles from Langston, a town named for her famous uncle. There the light-skinned Carrie met and married James Nathaniel Hughes, a handsome, hardworking man of color, with African, Native American, French, and Jewish blood. (His grandfathers were both slave traders.) But there was a crucial difference between the newlyweds: whereas Carrie had been brought up to be proud of her race, the color-struck James despised blackness, which he equated with poverty and powerlessness.

In 1899, the young, ambitious couple moved to Joplin, where Carrie gave birth to Langston in 1902. (Their first child, a boy, born in 1900, died in infancy.) A year later, when James secured a position in Mexico City, where he felt that he stood a better chance of success, Carrie dropped Langston off at her mother’s, and followed him south. The couple bickered, reconciled, parted, sometimes with Langston in tow, often not; for the most part, the boy was reared by his judicious but loving grandmother, Mary. By 1907, they had separated permanently.

There’s nothing like family to remind you of life’s essential loneliness. As a boy, Hughes absorbed his mother’s bitterness about her marriage and her thwarted career, as well as his father’s anxiety and rancor over racism in America and what he presumed to be its cause: blacks themselves. (Hughes recalled a train journey through Arkansas, during which his father, seeing some blacks at work in a cotton field, sneered, “Look at the niggers.”) Carrie never hesitated to tell her son that he resembled his father—“that devil”—and that he was as “evil as Jim Hughes.” His grandmother, angry about segregation—as a black person, she couldn’t join the church of her choice—forbade her grandson to go out after school: Why risk degradation in their sty?

Hughes grew up in an atmosphere of hatred and small-mindedness. While he was in elementary school, a white teacher warned one of Hughes’s white classmates against eating licorice, for fear that he would end up looking like Langston. A bright, genial boy, Hughes also suffered for his talents. From his poem “Genius Child”:

Nobody loves a genius child. Can you love an eagle, Tame or wild? Can you love an eagle, Wild or tame? Can you love a monster Of frightening name? Nobody loves a genius child. Kill him —and let his soul run wild.

Still, there was solace. There were books by W. E. B. Du Bois, and the formality and strange wisdom of the Bible. (Hughes read widely and deeply in the black and white American canons. And, throughout his career, he excitedly read the writers of color who were published in Europe, the Caribbean, and Africa, including René Maran, Graziella Garbalosa, and Richard Rive.) There was black pride, too. In 1910, Mary and her grandson went to Osawatomie, Kansas, where former President Theodore Roosevelt honored her first husband, Lewis Sheridan Leary, who had died during the 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry.

Mary herself died in 1915, and the thirteen-year-old Hughes soon left Kansas for Lincoln, Illinois, where his mother now lived with her second husband, Homer Clark, a sometime “chef cook,” and his son. In Lincoln, a teacher asked Hughes’s eighth-grade class to appoint a class poet who understood rhythm. Hughes’s fellow-students unanimously nominated Hughes, the only black boy in the class. Hughes wrote his first poem for the class graduation, and was so impressed by the applause he received that he wondered whether he had found his vocation. As Homer sought better career opportunities that never seemed to materialize, Hughes followed his mother and her new family to Cleveland, where he began contributing poems and stories to his high-school magazine. When his mother and his stepfather moved on again, to Chicago, Hughes stayed behind to finish high school, which he did in 1920. Although he was pretty much on his own from then on, his parents exercised a pull over him for as long as they lived. (“My Dear Boy: Carrie Hughes’s Letters to Langston Hughes, 1926-1938,” edited by Carmaletta M. Williams and John Edgar Tidwell, is valuable testimony to Carrie’s never-ending attempts to manipulate her son.)

Open to Hughes was the great wide world, the adventure of travel, and those writers—Carl Sandburg, Walt Whitman—who not only freed the young writer from traditional literary forms but showed him that he could sing his America, too. In 1921, he moved to New York to study at Columbia University, but what he fell in love with was the “Negro city”: Harlem. (He eventually dropped out of Columbia, and graduated from Lincoln University, in Pennsylvania, in 1929.) Before coming to New York, he had spent more than a year in patriarchal purgatory in Mexico; now he was “hungry” to be with his people. Exiting the subway at 135th Street, he said, “I stood there, dropped my bags, took a deep breath and felt happy again.”

Harlem in the twenties offered up a cultural richness that made everything seem possible. Jervis Anderson, writing in this magazine in 1981, noted, “Harlem has never been more high-spirited and engaging than it was during the nineteen-twenties. Blacks from all over America and the Caribbean were pouring in, reviving the migration that had abated toward the end of the war—word having reached them about the ‘city,’ in the heart of Manhattan, that blacks were making their own.” The headquarters for Du Bois’s magazine Crisis , to which Hughes had been contributing from Mexico, was there; so was Messenger , co-edited by the activist A. Philip Randolph. Soon Hughes found a new source of the kind of support that his grandmother had given him as a boy: a wealthy white woman named Charlotte Osgood Mason, who provided Hughes and other black artists, including Hurston, with financial backing, as long as they promoted blackness. (Despite the awkwardness of the arrangement, Hughes remained loyal to Mason—“I want to be your spirit child forever,” he wrote to her—and when he ceased to be a favorite, in 1930, he was devastated. That pain shows in his forced 1933 short story “Slave on the Block,” which he included in his passionate but ill-considered collection “The Ways of White Folks,” the following year.)

The charming Hughes also managed to melt the heart of the glacial Du Bois, who had lost a son, and counted Jessie Fauset, an editor at Crisis , and the poet Countee Cullen as champions of a sort. In 1923, Cullen introduced Hughes to Alain Locke, a gay Harvard-educated thinker, who published the influential anthology “The New Negro” in 1925. As one can intuit from “The Selected Letters,” the two embarked on a kind of cat-and-mouse game: Hughes needed Locke’s patronage, and, sensing the older man’s attraction to him, kept him at arm’s length to increase the mystery. Soon Hughes was a citizen of a bright black world that included Paul Robeson, who, in 1924, would star downtown in Eugene O’Neill’s “The Emperor Jones.” Putting his ear to the concrete, he heard poems like “Aesthete in Harlem,” which combined, within a short, intense form, the sound of the laughing and crying tom-tom he described in his 1926 Nation essay:

Strange, That in this nigger place I should meet life face to face; When, for years, I had been seeking Life in places gentler speaking— Before I came to this vile street And found Life—stepping on my feet!

The poem, like many of Hughes’s early lyrics, is both interesting and uninspiring. We admire him for the pre-spoken-word cadences and the energy of the enterprise, but without ever knowing who his “I” is we have no anchor in the poem. The ungrounded first-person voice allows Hughes to be humanity, but not a specific human.

Once the Depression put an end to all the champagne and sexy miscegenation of the Harlem Renaissance, the “niggerati” scattered to other gigs, some in other countries. Hughes travelled in Russia during the thirties, finding in Communism, at least for a time, the political hope that was missing in his own country, but he always returned to Harlem, even as the neighborhood suffered through race riots and the drug and civic wars of the fifties and sixties. It was his home until he died, in 1967—his ashes are now entombed in the lobby of the Langston Hughes Auditorium at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, in Harlem—visible evidence of all that Hughes’s father despised and he embraced, in what may very well have been the most unresolvable relationship of his life.

In 1961, twenty-seven years after James Hughes died, his son wrote a brief, intense tale called “Blessed Assurance.” Published posthumously, it begins:

Unfortunately (and to John’s distrust of God) it seemed his son was turning out to be a queer. He was a brilliant queer, on the Honor Roll in high school, and likely to be graduated in the spring at the head of the class. But the boy was colored. Since colored parents always like to put their best foot forward, John was more disturbed about his son’s transition than if they had been white. Negroes have enough crosses to bear.

When the boy sings a solo in the church choir and his voice soars, a male organist faints, and the boy’s father pleads for him to shut up. But the song goes on. What is natural to John’s son is the music, a world of sound which he can both hide behind and expose himself through.

In the final years of his life, Hughes did seem to see the tide turning. His last, and best, collection of poems, “The Panther and the Lash” (1967), reflects, with a haiku-like flatness and lift, a Vietnam-era world that was changing and needed to change. His poem “Corner Meeting”:

Ladder, flag, and amplifier now are what the soapbox used to be.

The speaker catches fire, Looking at listeners’ faces.

His words jump down to stand in their places.

Here Hughes writes with the force of a good journalist; he is no longer an abstract Negro everyman but a reporter weighing in on the heat and confusion of the time, without too much self-conscious hipster jive.

The novelist Paule Marshall recalls, in her 2009 memoir, “Triangular Road,” a 1965 government-sponsored tour of Europe on which she accompanied Hughes. It was during the heady days of the civil-rights movement. In Paris, a city that Hughes loved—“There you can be whatever you want to be. Totally yourself,” he said—Marshall noticed that when the subject of the movement came up Hughes let others do the talking. He knew what his own struggles had been, and he knew that the present struggle would lead to if not a different day then a different kind of day, one in which erasing lines from one’s own story might make less sense than just saying them. ♦

Breaking Ground

A Smithsonian magazine special report

AT THE SMITHSONIAN

What langston hughes’ powerful poem “i, too” tells us about america’s past and present.

Smithsonian historian David Ward reflects on the work of Langston Hughes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

David C. Ward

:focal(515x96:516x97)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/e9/0ee9e32c-4783-4c24-a21f-66ad0e7ad8e8/npg7282hughesrweb.jpg)

In large graven letters on the wall of the newly opened National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall is a quote from poet Langston Hughes: “I, too, am America.”

The line comes from the Hughes’s poem “I, too,” first published in 1926.

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

From THE COLLECTED POEMS OF LANGSTON HUGHES. By permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated

The poem is a singularly significant affirmation of the museum’s mission to tell the history of United States through the lens of the African-American experience. It embodies that history at a particular point in the early 20 th century when Jim Crow laws throughout the South enforced racial segregation; and argues against those who would deny that importance—and that presence.

Its mere 18 lines capture a series of intertwined themes about the relationship of African-Americans to the majority culture and society, themes that show Hughes’ recognition of the painful complexity of that relationship.

There is a multi-dimensional pun in the title, “I, too” in the lines that open and close the poem. If you hear the word as the number two, it suddenly shifts the terrain to someone who is secondary, subordinate, even, inferior .

Hughes powerfully speaks for the second-class, those excluded. The full-throated drama of the poem portrays African-Americans moving from out of sight, eating in the kitchen, and taking their place at the dining room table co-equal with the “company” that is dining.

Intriguingly, Langston doesn’t amplify on who owns the kitchen. The house, of course, is the United States and the owners of the house and the kitchen are never specified or seen because they cannot be embodied. Hughes’ sly wink is to the African-Americans who worked in the plantation houses as slaves and servants. He honors those who lived below stairs or in the cabins. Even excluded, the presence of African-Americans was made palpable by the smooth running of the house, the appearance of meals on the table, and the continuity of material life. Enduring the unendurable, their spirit lives now in these galleries and among the scores of relic artifacts in the museum’s underground history galleries and in the soaring arts and culture galleries at the top of the bronze corona-shaped building.

The other reference if you hear that “too” as “two” is not subservience, but dividedness.

Hughes’ pays homage to his contemporary, the intellectual leader and founder of the NAACP, W.E.B. DuBois whose speeches and essays about the dividedness of African-American identity and consciousness would rivet audiences; and motivate and compel the determined activism that empowered the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century.

The African-American, according to DuBois in his seminal work, The Souls of Black Folks, existed always in two ‘places” at once:

“One ever feels his two-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

DuBois makes the body of the African-American—the body that endured so much work and which is beautifully rendered in Hughes’ second stanza “I am the darker brother”—as the vessel for the divided consciousness of his people.

DuBois writes of the continual desire to end this suffering in the merging of this “double self into a better and truer self.” Yet in doing so, DuBois argued, paradoxically, that neither “of the older selves to be lost.”

The sense of being divided in two was not just the root of the problem not just for the African-American, but for the United States. As Lincoln had spoken about the coexistence of slavery with freedom: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”

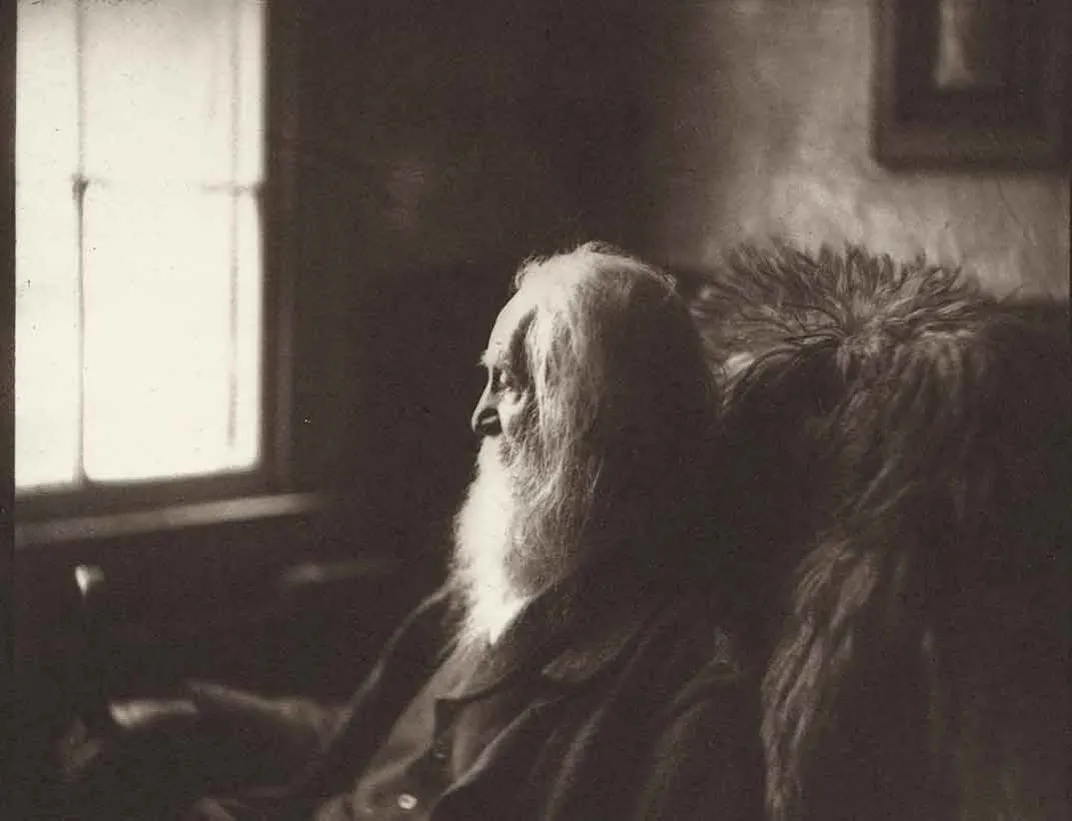

Hughes ties together this sense of the unity of the separate and diverse parts of the American democracy by beginning his poem with a near direct reference to Walt Whitman.

Whitman wrote, “I sing the body electric” and went on to associate the power of that body with all the virtues of American democracy in which power was vested in each individual acting in concert with their fellows. Whitman believed that the “electricity” of the body formed a kind of adhesion that would bind people together in companionship and love: “I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear. . .”

Hughes makes Whitman—his literary hero—more explicitly political with his assertion “I, too, sing America.”

The verb here is important because it suggests the implicit if unrecognized creative work that African-Americans provided to make America. African-Americans helped sing America into existence and for that work deserve a seat at the table, dining as coequals with their fellows and in the company of the world.

At the end of the poem, the line is changed because the transformation has occurred.

“I, too, am America.”

Presence has been established and recognized. The house divided is reconciled into a whole in which the various parts sing sweetly in their separate harmonies. The problem for the politics of all this, if not for the poem itself, is that the simple assertion of presence—“They’ll see how beautiful I am. . .” —may not be enough.

The new African American Museum on the National Mall is a powerful assertion of presence and the legitimacy of a story that is unique, tragic and inextricably linked to the totality of American history. “I, too” is Hughes at his most optimistic, reveling in the bodies and souls of his people and the power of that presence in transcendent change. But he fully realized the obstacles to true African-American emancipation and acceptance in the house of American democracy. He was the poet, remember, who also wrote “What will happen to a dream deferred?”

Get the latest on what's happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

David C. Ward | READ MORE

David C. Ward is senior historian emeritus at the National Portrait Gallery, and curator of the upcoming exhibition “The Sweat of their Face: Portraying American Workers."

The Model Short Story

On "salvation" by langston hughes.

Matthew Sharpe

“Salvation” is the third chapter of Langston Hughes’s memoir The Big Sea , but this two-page tour de force of prose is also a compact and complete story. Here are five things I like about it:

- The control of time. As the story opens, time breezes along in the weeks leading up to the revival meeting at twelve-year-old Langston’s church. Time then slows down paragraph by paragraph until, as Langston’s decisive moment approaches, it creeps.

- The control of space. Sometimes we see close-ups from twelve-year-old Langston’s point of view of “old women with jet-black faces and braided hair, old men with work-gnarled hands”; other times we see long shots, as if from up in the church’s rafters: “Suddenly the whole room broke into a sea of shouting. Waves of rejoicing swept the place.” And, as the church does, the author imbues with enormous significance the ten feet of space between the front row of pews and the altar, which the boy must cross to be saved.

- The doubleness of the narrator. His diction and sensibility move fluidly back and forth between the man’s and the boy’s.

- Polyphony. Not only the two Langstons’, but his Auntie Reed’s, the preacher’s, and his friend Westley’s voices are heard, as is the voice of the church via the liturgy.

- Irony. The verbal irony of the title, “Salvation,” is a kind of shorthand for the dramatic irony of the plot, wherein the more lost young Langston feels, the more his fellow congregants are convinced they are saving him.

“Salvation” by Langston Hughes

I was saved from sin when I was going on thirteen. But not really saved. It happened like this. There was a big revival at my Auntie Reed’s church. Every night for weeks there had been much preaching, singing, praying, and shouting, and some very hardened sinners had been brought to Christ, and the membership of the church had grown by leaps and bounds. Then just before the revival ended, they held a special meeting for children, “to bring the young lambs to the fold.” My aunt spoke of it for days ahead. That night I was escorted to the front row and placed on the mourners’ bench with all the other young sinners, who had not yet been brought to Jesus.

My aunt told me that when you were saved you saw a light, and something happened to you inside! And Jesus came into your life! And God was with you from then on! She said you could see and hear and feel Jesus in your soul. I believed her. I had heard a great many old people say the same thing and it seemed to me they ought to know. So I sat there calmly in the hot, crowded church, waiting for Jesus to come to me.

The preacher preached a wonderful rhythmical sermon, all moans and shouts and lonely cries and dire pictures of hell, and then he sang a song about the ninety and nine safe in the fold, but one little lamb was left out in the cold. Then he said: “Won’t you come? Won’t you come to Jesus? Young lambs, won’t you come?” And he held out his arms to all us young sinners there on the mourners’ bench. And the little girls cried. And some of them jumped up and went to Jesus right away. But most of us just sat there.

A great many old people came and knelt around us and prayed, old women with jet-black faces and braided hair, old men with work-gnarled hands. And the church sang a song about the lower lights are burning, some poor sinners to be saved. And the whole building rocked with prayer and song.

Still I kept waiting to see Jesus.

Finally all the young people had gone to the altar and were saved, but one boy and me. He was a rounder’s son named Westley. Westley and I were surrounded by sisters and deacons praying. It was very hot in the church, and getting late now. Finally Westley said to me in a whisper: “God damn! I’m tired o’ sitting here. Let’s get up and be saved.” So he got up and was saved.

Then I was left all alone on the mourners’ bench. My aunt came and knelt at my knees and cried, while prayers and song swirled all around me in the little church. The whole congregation prayed for me alone, in a mighty wail of moans and voices. And I kept waiting serenely for Jesus, waiting, waiting – but he didn’t come. I wanted to see him, but nothing happened to me. Nothing! I wanted something to happen to me, but nothing happened.

I heard the songs and the minister saying: “Why don’t you come? My dear child, why don’t you come to Jesus? Jesus is waiting for you. He wants you. Why don’t you come? Sister Reed, what is this child’s name?”

“Langston,” my aunt sobbed.

“Langston, why don’t you come? Why don’t you come and be saved? Oh, Lamb of God! Why don’t you come?”

Now it was really getting late. I began to be ashamed of myself, holding everything up so long. I began to wonder what God thought about Westley, who certainly hadn’t seen Jesus either, but who was now sitting proudly on the platform, swinging his knickerbockered legs and grinning down at me, surrounded by deacons and old women on their knees praying. God had not struck Westley dead for taking his name in vain or for lying in the temple. So I decided that maybe to save further trouble, I’d better lie, too, and say that Jesus had come, and get up and be saved.

So I got up.

Suddenly the whole room broke into a sea of shouting, as they saw me rise. Waves of rejoicing swept the place. Women leaped in the air. My aunt threw her arms around me. The minister took me by the hand and led me to the platform.

When things quieted down, in a hushed silence, punctuated by a few ecstatic “Amens,” all the new young lambs were blessed in the name of God. Then joyous singing filled the room.

That night, for the first time in my life but one for I was a big boy twelve years old – I cried. I cried, in bed alone, and couldn’t stop. I buried my head under the quilts, but my aunt heard me. She woke up and told my uncle I was crying because the Holy Ghost had come into my life, and because I had seen Jesus. But I was really crying because I couldn’t bear to tell her that I had lied, that I had deceived everybody in the church, that I hadn’t seen Jesus, and that now I didn’t believe there was a Jesus anymore, since he didn’t come to help me.

“Salvation” from The Big Sea by Langston Hughes. Copyright © 1940 by Langston Hughes. Copyright renewed 1968 by Arna Bontemps and George Houston Bass. Reprinted by permission of Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. www.fsgbooks.com

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was a poet, novelist, playwright, columnist, memoirist, and short story writer. The author of more than 30 books and a dozen plays, he was extremely influential during the Harlem Renaissance and in the decades beyond; he also had a profound influence on a younger generation of writers, including Paule Marshall and Alice Walker. “Salvation” is taken from his memoir, The Big Sea .

About this series

In The Model Short Story, acclaimed authors choose a short story and discuss its importance to them and how it has assisted them in their own writing practice.

Discover Our Fiction, Essays & More

Little Star

The Monsters of Dr. Daedalus Gall

Polyphemus the Kind

Biking Home

Remnants of My Homeland

A Raised Eyebrow

Falling into the Culture of In-Between

The Story of the Skipping Stone

San and Bert

All the Buttons

Public Park Therapy

An Excerpt from Brad Kessler's North

An Excerpt from Myriam J. A. Chancy's What Storm, What Thunder

As They Imagine Us on Summer Nights

A Letter to Mama

Recalcitrance

Clairvoyance

The Thing in the Wall

Langston Hughes Essay

James Langston Hughes was born in Joplin on Feb. 1, 1902. Although he did not live there for long, he was always proud of his connection to the state. Until 1915 he lived in Lawrence, Kansas, close to the Missouri border. He had close relatives who lived in Kansas City, Missouri. But his link to Missouri ran deep into history. From his maternal grandmother, Mary Langston, he learned much about the Kansas-Missouri border wars and their historic consequences for blacks especially. Her first husband had died fighting alongside John Brown at Harpers Ferry, and her second, Hughes’s grandfather, had also been a militant abolitionist. Such events cast a long shadow over Hughes as he grew up in increasingly segregated Lawrence. His rich career should be seen as his calculated response to the challenges of this history, but by the time of his death he clearly had made peace with Missouri. Elected a trustee of the Missouri Society of New York in 1963, he was proud to be part of a great literary tradition that includes Mark Twain, T.S. Eliot, and Hughes’s good friend the poet Marianne Moore. Hughes’s parents, James Nathaniel and Carrie Mercer Langston Hughes, met in Oklahoma. She was an aspiring actress and writer; his great goal was to be a lawyer and successful businessman. They were married in Guthrie, Oklahoma, but soon moved to Joplin when he found a promising job there. Being black, however, he found it virtually impossible to gain admission to the bar. When Langston was born, James was probably far away. His ambition took him first to Cuba and then to Mexico, where he found jobs commensurate with his talents and training. He lived in Mexico for the rest of his life. (He and his family barely missed the horror that struck Joplin in April 1903. A white mob stormed the city jail, lynched a black man accused of killing a policeman, and violently expelled many blacks from the town.) Hughes saw little of his father after that. Materialistic and cold, as Langston saw him, James disapproved of his son’s passion for poetry and his sympathy for the black masses. Attempts at reconciliation in Mexico failed. They did not see one another after 1921. Mainly Langston grew up in Lawrence, Kansas with Mary Langston. After her second husband’s death, the family fell into poverty. Langston’s mother was often away, searching for work. Hughes grew up a lonely child who came to believe less in people than in fiction and poetry. In 1915, when his grandmother died, he joined his mother and her second husband in Lincoln, Illinois. There he wrote his first poem. They moved next to Cleveland. He lived there from 1916 to 1920. Sometimes he lived alone, as his stepfather scrambled to find work. However, at the progressive Central High School he received a first-rate education. In the school magazine he published several poems and stories. In 1921, funded reluctantly by his father, he entered Columbia University in New York, but left after a disillusioning year in search of freedom and literary inspiration. In 1921 he published in The Crisis his signature poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” in his first appearance as a writer in a national magazine. Its opening line (“I’ve known rivers”) had come to him just as he was crossing the Mississippi at sunset on a train from Kansas into Missouri, going to join his father in Mexico. The four years after Columbia found him roaming the coast of Africa as a seaman, or working in Paris and in Washington–but always writing. In 1926, his first book, The Weary Blues, confirmed his status as a star of the Harlem Renaissance. That month, January, he also entered Lincoln University in Pennsylvania (his B.A. came in 1929). Also in 1926 The Nation magazine published his manifesto for younger black writers, the essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” In 1930 he published his first novel, Not Without Laughter. Politically, Hughes moved in the 1930s to the far left, as did many other Americans also pushed by the Great Depression. In 1931-1932 he toured the South and the West by car, taking his poetry to the people. In 1932 he joined a group of young blacks invited to the Soviet Union to make a movie about American race relations. The project collapsed, but he spent many months living in Moscow and also touring the Asian republics of the USSR. Returning to the US in 1933 via Japan and China, he lived in California for a year. In 1934, he published a hard hitting collection of stories, The Ways of White Folks (1934). Also in the 1930s he worked hard at writing plays. His tragedy about miscegenation, Mulatto, opened on Broadway in 1935. In 1936, still haunted by the Depression, he published his memorable political anthem “Let America Be America Again.” Often broke, he tried to work in Hollywood but found it demeaning to blacks. In 1940 came an autobiography, The Big Sea. About this time Hughes found himself hunted because of radical poems he had published in the early 1930s, especially one (“Goodbye Christ”) about charlatans who exploit religious faith. Retreating, he turned to safer themes, including the nascent modern civil rights struggle. Attacks on him continued, however, culminating in a somewhat humiliating appearance in 1953 before Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communistic subcommittee. But by this time, by dint of hard work and his versatility, he had also enjoyed some success. In 1947, his work on the Broadway opera Street Scene enabled him to buy a modest townhouse in Harlem. He lived there for the rest of his life. Hughes continued to publish books. They included more poetry but also another autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander; books for children, such as The First Book of Jazz and The First Book of Africa; histories such as Fight for Freedom, the story of the NAACP; various plays; and anthologies of African American and African writing. He pioneered the development of the gospel musical, notably his Black Nativity. In 1960, the NAACP awarded him its highest honor, the Spingarn Medal. He toured Africa on behalf of the U.S. State Department. He was still an active force when complications after surgery ended his life in a New York hospital on May 22, 1967. Langston Hughes was arguably the premier poet of the black American experience, the most versatile of black writers, and one of the finest authors in American literature. Widespread academic attention to him began, fittingly, at a conference in 1983 organized in Joplin at Missouri Southern University, when Joplin reclaimed and celebrated him as a favorite son. Arnold Rampersad Stanford University

Poems & Poets

Jazz as Communication

BY Langston Hughes

Introduction

Langston Hughes, a central poet of the Harlem renaissance, was significantly influenced by the sounds and traditions of the blues and jazz. He presented “Jazz and Communication” at a panel led by Marshall Stearns at the Newport Casino Theater during the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival. The essay opens on a practical note, as Hughes questions those who feel that jazz can exist only outside of commercial spheres. He points out that all the great blues musicians, by performing, have been “communicating for money,” and that this in no way compromised their craft. Hughes argues that jazz is everywhere, encompassing the blues and rock and roll. To those who would deny the connections between musical traditions, Hughes states, “Jazz is a great big sea. It washes up all kinds of fish and shells and spume and waves with a steady old beat, or off-beat.” Throughout the essay, Hughes cites the singers and musicians who have influenced his writing. He also notes other authors who have been “putting jazz into words,” such as Dorothy Baker, Jean Paul Sartre, and W.C. Handy. Turning to the audience, Hughes states, “Jazz is a heartbeat—its heartbeat is yours. You will tell me about its perspectives when you get ready.”

You can start anywhere—Jazz as Communication—since it’s a circle, and you yourself are the dot in the middle. You, me. For example, I’ll start with the Blues. I’m not a Southerner. I never worked on a levee. I hardly ever saw a cotton field except from the highway. But women behave the same on Park Avenue as they do on a levee: when you’ve got hold of one part of them the other part escapes you. That’s the Blues!

Life is as hard on Broadway as it is in Blues-originating-land. The Brill Building Blues is just as hungry as the Mississippi Levee Blues. One communicates to the other, brother! Somebody is going to rise up and tell me that nothing that comes out of Tin Pan Alley is jazz. I disagree. Commercial, yes. But so was Storeyville, so was Basin Street. What do you think Tony Jackson and Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver and Louis Armstrong were playing for?(1) Peanuts? No, money, even in Dixieland. They were communicating for money. For fun, too—because they had fun. But the money helped the fun along.

Now; To skip a half century, somebody is going to rise up and tell me Rock and Roll isn’t jazz. First, two or three years ago, there were all these songs about too young to know —but . . . . The songs are right. You’re never too young to know how bad it is to love and not have love come back to you. That’s as basic as the Blues. And that’s what Rock and Roll is—teenage Heartbreak Hotel —the old songs reduced to the lowest common denominator. The music goes way back to Blind Lemon and Leadbelly—Georgia Tom merging into the Gospel Songs—Ma Rainey, and the most primitive of the Blues.(2) It borrows their gut-bucket heartache. It goes back to the jubilees and stepped-up Spirituals—Sister Tharpe—and borrows their I’m-gonna-be-happy-anyhow-in-spite-of-this-world kind of hope. It goes back further and borrows the steady beat of the drums of Congo Square—that going-on beat—and the Marching Bands’ loud and blatant yes!! Rock and Roll puts them all together and makes a music so basic it’s like the meat cleaver the butcher uses—before the cook uses the knife—before you use the sterling silver at the table on the meat that by then has been rolled up into a commercial filet mignon.

A few more years and Rock and Roll will no doubt be washed back half forgotten into the sea of jazz. Jazz is a great big sea. It washes up all kinds of fish and shells and spume and waves with a steady old beat, or off-beat. And Louis must be getting old if he thinks J. J. and Kai—and even Elvis—didn’t come out of the same sea he came out of, too. Some water has chlorine in it and some doesn’t. There’re all kinds of water. There’s salt water and Saratoga water and Vichy water, Quinine water and Pluto water—and Newport rain. And it’s all water. Throw it all in the sea, and the sea’ll keep on rolling along toward shore and crashing and booming back into itself again. The sun pulls the moon. The moon pulls the sea. They also pull jazz and me. Beyond Kai to Count to Lonnie to Texas Red, beyond June to Sarah to Billy to Bessie to Ma Rainey. And the Most is the It—the all of it.(3)

Jazz seeps into words—spelled out words. Nelson Algren is influenced by jazz. Ralph Ellison is, too. Sartre, too. Jacques Prévert. Most of the best writers today are. Look at the end of the Ballad of the Sad Cafe. Me as the public, my dot in the middle—it was fifty years ago, the first time I heard the Blues on Independence Avenue in Kansas City. Then State Street in Chicago. Then Harlem in the twenties with J. P. and J. C. Johnson and Fats and Willie the Lion and Nappy playing piano—with the Blues running all up and down the keyboard through the ragtime and the jazz.(4) House rent party cards. I wrote The Weary Blues:

Downing a drowsy syncopated tune . . . . . . etc. . . . .

Shuffle Along was running then—the Sissle and Blake tunes. A little later Runnin’ Wild and the Charleston and Fletcher and Duke and Cab. Jimmie Lunceford, Chick Webb, and Ella. Tiny Parham in Chicago. And at the end of the Depression times, what I heard at Minton’s. A young music—coming out of young people. Billy—the male and female of them—both the Eckstein and the Holiday—and Dizzy and Tad and the Monk.(5) Some of it came out in poems of mine in Montage of a Dream Deferred later. Jazz again putting itself into words.

But I wasn’t the only one putting jazz into words. Better poets of the heart of jazz beat me to it. W. C. Handy a long time before. Benton Overstreet. Mule Bradford. Then Buddy DeSilva on the pop level. Ira Gershwin. By and by Dorothy Baker in the novel—to name only the most obvious—the ones with labels. I mean the ones you can spell out easy with a-b-c’s—the word mongers—outside the music. But always the ones of the music were the best—Charlie Christian, for example, Bix, Louis, Joe Sullivan, Count.(6)