- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Rewinding to the Great Indian Empires Before the British Raj

Nandini das offers a reading list on indian colonial history.

To mention the British in India is to evoke memories of the Raj, of luxury and grandeur that went hand in hand with appropriation and exploitation, cricket and tea and pashminas that were products of the same set of conditions that brought famine and violence to multitudes, and left a sub-continent stripped, scarred and irrevocably divided.

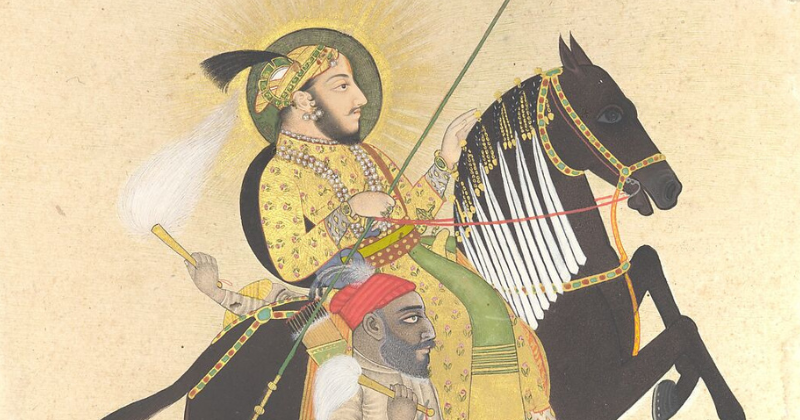

Yet there is a moment before that received history begins, when things were still in flux, and possibilities unrolled in multiple directions. The first decades of the seventeenth century represent just such a moment, when the Mughal empire in northern India was one of the wealthiest global powers, and England found itself a belated entrant into a world of trade and exchange in which others had already staked a claim.

My book, Courting India , is about the first English embassy to India, seen through the experiences of the man at its helm, Thomas Roe, charged with the responsibility of acquiring the elusive permits that would allow the English at last to set up permanent trading links with the sub-continent. This is not a moment that usually gets more than passing reference in histories of empire: the power-imbalance it sets up between India and England is too counter-intuitive, and Roe’s efforts too obviously lacking in results.

Yet that is precisely why, I argue, this moment demands our attention. It stands witness both to possible alternative roads down which the history of the two nations could have unfolded, and to the ways in which assumptions and expectations about other nations, other cultures, take shape and cohere, colored by our own memories and anxieties, fears and hopes.

In exploring the historical records of that moment, I wanted to pay attention not just to the unfolding of political and economic negotiations driven by those in power, but also to those who tend to get written out of the grand narratives of empire. Courting India is therefore not just about Roe, or even about the East India Company.

From the young Indian boy brought to England as part of a trading company’s attempts to demonstrate their civilizing mission, to the homesick English merchants terrified of dying far from home, from headstrong English women who insisted on entering unsuitable marriages, to equally headstrong Mughal women negotiating the world of the imperial politics, it is about multiple lives that were caught up in the process.

The list below has some of the books I returned to time and again, to understand the period, and the people, of both nations.

Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Europe’s India

Subrahmanyam’s book is a sprawling, thoroughly readable exploration of the evolution of European views of India in the roughly three centuries that lay between Vasco da Gama landing on the western coast of India, and the East India Company’s rise to power as the preeminent European presence in South Asia. This is a book that wears its prodigious range of learning lightly, moving from political history to literature, art to intellectual history with infinite ease. What it offers is a wonderfully sharp account of the intricate ways in which European ideas about India and what it meant to be ‘Indian’ went through layers of revision, even as the European commentators themselves changed as a result.

Richard M. Eaton, India in the Persianate Age, 1000-1765

Richard Eaton’s book is another history of extraordinary scholarship that still manages to remain accessible. It is a striking account of the linguistic and cultural complexity of pre-modern India, characterized by a degree of cultural and religious diversity which would shock and puzzle visitors from Protestant England, like Thomas Roe and his travel companions. It is also a useful reminder that the Mughals were not the only powers in the sub-continent. In the Deccan plateau, southern India, and Bengal, other powers flourished whose presence implicitly shaped Mughal worldview and actions—whether or not the newly-arrived Europeans fully grasped the implications of such internal interactions.

Jonathan Gil Harris, The First Firangis

Nations do not “encounter” each other in the abstract. That process takes place between individuals, each of whom carry their own assumptions and expectations. From physicians and artists, to pirates and priests, Jonathan Gil Harris’s collection introduces us to some of the very first travelers, from England, Europe, and beyond who arrived in pre-modern India, either willingly or unwillingly, and found themselves carving out new lives, and often, new identities.

As an expatriate living in India, Harris is particularly adept at illuminating sensory and bodily transformations, the ways in which sight and smell, the food we ingest and the sounds we hear become a part of us. His approach through micro-histories is very different from that of the more expansive books above, but no less illuminating, particularly when tackling the problem of recording lives of which the barest traces remain.

David Lindley, The Trials of Frances Howard: Fact and Fiction at the Court of King James

In 1615, the trial of Frances Howard and her husband, James I’s erstwhile favorite, Robert Carr, the Earl of Somerset, took England by storm. It had all the ingredients of a perfect scandal—sex, fraud, a whiff of same-sex intrigue, corruption, and murder. Howard was accused of poisoning her husband’s best friend, Sir Thomas Overbury. Roe had known Overbury in England, and while he was in India by the time the news broke, the Howard trials provide a superb and utterly gripping lens to understand the royal court and the country from which Roe had arrived at the Mughal court.

It is a portrait of a country in crisis, where misogyny, political paranoia, and intense competition for power held sway. If travelers carry their own worldviews with them, Roe’s was tinged with the same shades of anxiety and suspicion that we see in David Lindley’s account of the court of James I.

Ruby Lal, Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan

If Lindley’s book allows us a close look at the inner workings of James I’s court and contemporary English society, Ruby Lal does the same for Jahangir’s court, through another woman who has attracted as much criticism as Frances Howard, and significantly more fear, because of the power she was seen to wield. Lal’s biography of Nur Jahan, the favorite wife and consort of the Mughal emperor Jahangir, identifies itself as feminist historiography, that must often “look around” the towering male figures in received history. It excavates records either ignored or distorted by the biases of men who had written about Nur Jahan since her own lifetime and afterwards, and the result is a striking re-evaluation of both Nur and Jahangir, as well as the world they occupied.

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy

There are numerous books about the history of the East India Company, but Dalrymple brings a particular immediacy to the story of its fortunes in the century and half following Roe’s embassy. Historians have often returned to the way in which the East India Company’s ruthless rise coincided with their equally ruthless exploitation of civil strife in India following the collapse of the Mughal empire. Dalrymple draws attention particularly to the Company’s profiteering turned it into a mega-corporation of its time, wielding huge military as well as economic power.

Trade and war are mutually incompatible, Thomas Roe had warned the early East India Company during his embassy. Yet by the eighteenth century, the Company’s opinion about the use of military force had changed completely, and large-scale territorial conquests had laid increasingly larger swathes of India open to their pillaging. A new chapter in the history of both nations was about to begin.

__________________________________

Nandini Das is the author of Courting India: Seventeenth-Century England, Mughal India, and the Origins of Empire , available now from Pegasus Books.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Nandini Das

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Tiffany Clarke Harrison on Embracing the Fragmentary in Her Debut Novel

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- British Colonial Rule

The famous Kohinoor diamond has been doing rounds in the news. It was a prized possession of pre-colonial India which the British took with them on their way back home. The talks of taking it back have caused a stir in the recent past. However, it forms a very small fraction of what our colonizers took away. As a consequence, our country was in a grim state when they left. This forms the basis that governs our current policies and future prospects.

Suggested Videos

The pre-colonial state.

Before the advent of colonial rule , India was a self-sufficient and flourishing economy. Evidently, our country was popularly known as the golden eagle. India had already established itself on the world map with a decent amount of exports. Although primarily it was an agrarian economy, many manufacturing activities were budding in the pre-colonial India.

Indian craftsmanship was widely popular around the world and garnered huge demands . The economy was well-known for its handicraft industries in the fields of cotton and silk textiles, metal and precious stone works etc. Such developments lured the British to paralyze our state and use it for their home country’s benefits.

Browse more Topics under Indian Economy On The Eve Of Independence

- Agricultural Sector

- Industrial Sector

- Foreign Trade

- Demographic Condition

- Occupational Structure

- Infrastructure

India: The British Colony

The British came to India with the motive of colonization. Their plans involved using India as a feeder colony for their own flourishing economy back at Britain. This exploitation continued for about two centuries, till we finally got independence on 15 August 1947. Consequently, this rendered our country’s economy hollow. Hence, a study of this relationship between the colonizers and its colony is important to understand the present developments and future prospects of India.

The colonial rule is marked with periods of heavy exploitation. The British took steps that ensured development and promotion of the interests of their home country. They were in no way concerned about the course of Indian economy. Such steps transformed our economy for the worse- it effectively became a supplier of raw materials and a consumer of finished goods.

The colonial kings robbed India of education, opportunities etc. reducing Indians to mere servants. Undoubtedly, they never tried to estimate colonial India’s national and per capita income. Some individuals like – Findlay Shirras, Dadabhai Naoroji, William Digby, V.K.R.V. Rao and R.C. Desai tried to estimate such figures.

Although the results were inconsistent, the estimates of V.K.R.V. Rao are considered accurate. Notably, India’s growth of aggregate real output was less than 2% in the first half of the twentieth century coupled with a half percent growth in per capita output per year. By and large, India faced a herculean task to recover from the blows that two centuries of colonial rule landed on its economy.

Solved Example for You

Q: Name some individuals who tried to estimate colonial India’s per capita income.

Ans: Some individuals like – Findlay Shirras, Dadabhai Naoroji, William Digby, V.K.R.V. Rao and R.C. Desai tried to estimate such figures. Although the results were inconsistent, the estimates of V.K.R.V. Rao are considered accurate. An estimate was the best that could be calculated. The estimate was that colonial India’s growth of output was less than 2%.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

Indian Economy on the Eve of Independence

One response to “foreign trade”.

can I ask who the author is and the date of the publishment? I want to cite it in my paper.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

India before the British

Desmond kuah, university scholars programme , national university of singapore.

[ Victorian Web Home —> Victorian Political History —> Victorian Social History —> The British Empire —> British India ]

Mogul Decline in the 18th Century

The new emperor, Bahadur Shah I (1707-12), thought more tolerant, was unable to prevent Mogul decline. He never abolished jizya, but his effort to collect the tax became ineffectual. Bahadur Shah I tried to impose greater control over the Rajput states of Amber and Jodhpur, but was unsuccessful. His policies toward the Hindu Marathas were also half-hearted conciliatory as they were never defeated by the Moguls and resistance to Mogul rule persisted in the south.

Political and Economic Decentralization During the Mogul Decline

With the decline of Mogul central authority, the period between 1707 and 1761 witnessed the rise of the provinces against Delhi. This resurgence of regional identity accentuated both political and economic decentralization as Mogul military powers ebbed. The provinces became increasing independent from the central authority both economically and politically. Aided by intra-regional as well as inter-regional trade in local raw produce and artifacts, these provinces became virtual kingdoms. Bengal, Bihar, and Avadh in Northern India were among the new independent regions where these developments were most apparent. Their rulers became almost independent warlords recognizing the Mogul Emperor in name only. These provinces laid the foundations for the princely states under the Raj .

The Rise of Princely States

In due course, the growth of the regions at the expanse of Mogul central authority, gave local land- and power-holders enough influence to take up arms against Mogul authority and declare their independence. This gave rise to the princely states of British India . More often than not, narrow and selfish goals prevented these rebels from consolidating their interests into an effective challenge to the empire. These princes relied on the support from their relatives, lesser nobility, and peasants. Their rule was very personalized with followers swearing allegiance to the ruler alone and not to the state. As such, with the death of a prince, allegiance was reshuffled and loyalty divided. Next, the selfish motives of each princely state, made cooperation impossible. Each local group stroved to maximize its share of the spoils at the expense of the others. The princes were thus never strong enough to dominate any sizeable territories and the Mogul Empire, shrank thought it was lasted till 1858 .

The Mogul rulers were not replaced by the princes. Their presence was necessary to act as a balance and arbitrator between the powerful princes, each having his own agenda. The princes in the regions, were always alert for opportunities to establish their dominance over the others in the neighborhood, yet at the same time feared and resisted similar attempts by the others. As such, they all needed for their vices a kind of legitimacy, which was conveniently available in the long-accepted authority of the Mogul Emperor. With Mogul authority so weak, the princes had no fear in collectively accepting the Mogul Emperor as the titular head-of-state.

Bibliography and Web Resources

- Kamat's potpourri, "When the Moguls Ruled..."

- Benton W. (1972), "India" and "Pakistan" Encyclopedia Britannica

Last modified 6 November 2000

Blighted by Empire: What the British Did to India

By omer aziz september 1, 2018.

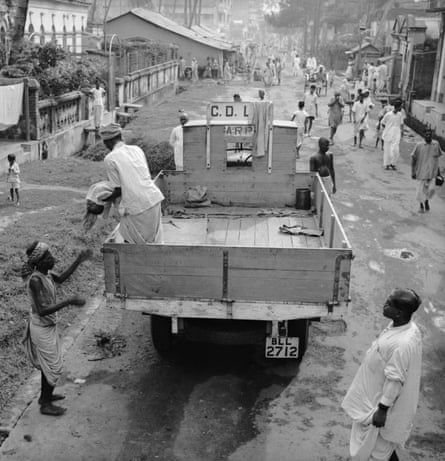

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F09%2FBritishRaj.png)

In seven weeks it was done, the frontiers decided A continent for better or worse divided The next day he sailed for England, where he could quickly forget The case, as a good lawyer must. Return he would not Afraid, as he told his Club, that he might get shot.

[W]e in India have known racialism in all its forms ever since the commencement of British rule. The whole ideology of this rule was that of the herrenvolk and the master race, and the structure of government was based upon it; indeed the idea of a master race is inherent in imperialism. There was no subterfuge about it; it was proclaimed in unambiguous language by those in authority. More powerful than words was the practice that accompanied them and, generation after generation and year after year, India as a nation and Indians as individuals were subjected to insult, humiliation and contemptuous treatment. The English were an imperial race, we were told, with the God-given right to govern us and keep us in subjection.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Delightful listening: a conversation between viet thanh nguyen with arundhati roy.

Viet Thanh Nguyen, whose novel “The Sympathizer” won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, speaks to novelist Arundhati Roy.

Viet Thanh Nguyen Jul 31, 2018

Politics and Economics

Reverse Robin Hood: The Historical Scam of Global Development

When a world system is based on the creation of scarcity, it is the meek that inherit that scarcity.

Levi Vonk Jul 19, 2017

Translation

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

A Timeline of India in the 1800s

The British Raj Defined India Throughout the 1800s

- European History Figures & Events

- Wars & Battles

- The Holocaust

- European Revolutions

- Industry and Agriculture History in Europe

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

The British East India Company arrived in India in the early 1600s, struggling and nearly begging for the right to trade and do business. Within 150 years the thriving firm of British merchants, backed by its own powerful private army, was essentially ruling India.

In the 1800s English power expanded in India, as it would until the mutinies of 1857-58. After those very violent spasms things would change, yet Britain was still in control. And India was very much an outpost of the mighty British Empire .

1600s: The British East India Company Arrived

After several attempts to open trade with a powerful ruler of India failed in the earliest years of the 1600s, King James I of England sent a personal envoy, Sir Thomas Roe, to the court of the Mogul emperor Jahangir in 1614.

The emperor was incredibly wealthy and lived in an opulent palace. And he was not interested in trade with Britain as he couldn't imagine the British had anything he wanted.

Roe, recognizing that other approaches had been too subservient, was deliberately difficult to deal with at first. He correctly sensed that earlier envoys, by being too accommodating, had not gained the emperor's respect. Roe's stratagem worked, and the East India Company was able to establish operations in India.

1600s: The Mogul Empire at Its Peak

The Mogul Empire had been established in India in the early 1500s, when a chieftain named Babur invaded India from Afghanistan. The Moguls (or Mughals) conquered most of northern India, and by the time the British arrived the Mogul Empire was immensely powerful.

One of the most influential Mogul emperors was Jahangir's son Shah Jahan , who ruled from 1628 to 1658. He expanded the empire and accumulated enormous treasure, and made Islam the official religion. When his wife died he had the Taj Mahal built as a tomb for her.

The Moguls took great pride in being patrons of the arts, and painting, literature, and architecture flourished under their rule.

1700s: Britain Established Dominance

The Mogul Empire was in a state of collapse by the 1720s. Other European powers were competing for control in India, and sought alliances with the shaky states that inherited the Mogul territories.

The East India Company established its own army in India, which was composed of British troops as well as native soldiers called sepoys.

The British interests in India, under the leadership of Robert Clive , gained military victories from the 1740s onward, and with the Battle of Plassey in 1757 were able to establish dominance.

The East India Company gradually strengthened its hold, even instituting a court system. British citizens began building an "Anglo-Indian" society within India, and English customs were adapted to the climate of India.

1800s: "The Raj" Entered the Language

The British rule in India became known as "The Raj," which was derived from the Sanskrit term raja meaning king. The term did not have official meaning until after 1858, but it was in popular usage many years before that.

Incidentally, a number of other terms came into English usage during The Raj: bangle, dungaree, khaki, pundit, seersucker, jodhpurs, cushy, pajamas, and many more.

British merchants could make a fortune in India and would then return home, often to be derided by those in British high society as nabobs , the title for an official under the Moguls.

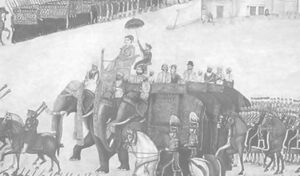

Tales of life in India fascinated the British public, and exotic Indian scenes, such as a drawing of an elephant fight, appeared in books published in London in the 1820s.

1857: Resentment Toward the British Spilled Over

The Indian Rebellion of 1857, which was also called the Indian Mutiny, or the Sepoy Mutiny , was a turning point in the history of Britain in India.

The traditional story is that Indian troops, called sepoys, mutinied against their British commanders because newly issued rifle cartridges were greased with pig and cow fat, thus making them unacceptable for both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. There is some truth to that, but there were a number of other underlying causes for the rebellion.

Resentment toward the British had been building for some time, and new policies which allowed the British to annex some areas of India exacerbated tensions. By early 1857 things had reached a breaking point.

1857-58: The Indian Mutiny

The Indian Mutiny erupted in May 1857, when sepoys rose up against the British in Meerut and then massacred all the British they could find in Delhi.

Uprisings spread throughout British India. It was estimated that less than 8,000 of nearly 140,000 sepoys remained loyal to the British. The conflicts of 1857 and 1858 were brutal and bloody, and lurid reports of massacres and atrocities circulated in newspapers and illustrated magazines in Britain.

The British dispatched more troops to India and eventually succeeded in putting down the mutiny, resorting to merciless tactics to restore order. The large city of Delhi was left in ruins. And many sepoys who had surrendered were executed by British troops .

1858: Calm Was Restored

Following the Indian Mutiny, the East India Company was abolished and the British crown assumed full rule of India.

Reforms were instituted, which included tolerance of religion and the recruitment of Indians into the civil service. While the reforms sought to avoid further rebellions through conciliation, the British military in India was also strengthened.

Historians have noted that the British government never actually intended to take control of India, but when British interests were threatened the government had to step in.

The embodiment of the new British rule in India was the office of the Viceroy.

1876: Empress of India

The importance of India, and the affection the British crown felt for its colony, was emphasized in 1876 when Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli declared Queen Victoria to be "Empress of India."

British control of India would continue, mostly peacefully, throughout the remainder of the 19th century. It wasn't until Lord Curzon became Viceroy in 1898, and instituted some very unpopular policies, that an Indian nationalist movement began to stir.

The nationalist movement developed over decades, and, of course, India finally achieved independence in 1947.

- The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857

- Images of British India

- East India Company

- The British Raj in India

- The Indian Revolt of 1857

- Colonial India in Cartoons

- A Timeline of India's Mughal Empire

- The Mughal Empire in India

- Overview of the Sepoy

- The First and Second Opium Wars

- The First Anglo-Afghan War

- Biography of Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore

- Timeline of Indian History

- What Was the Partition of India?

- Biography of Queen Victoria, Queen of England and Empress of India

- Seven Years' War: Major General Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive

Illusions of empire: Amartya Sen on what British rule really did for India

It is true that before British rule, India was starting to fall behind other parts of the world – but many of the arguments defending the Raj are based on serious misconceptions about India’s past, imperialism and history itself

T he British empire in India was in effect established at the Battle of Plassey on 23 June 1757. The battle was swift, beginning at dawn and ending close to sunset. It was a normal monsoon day, with occasional rain in the mango groves at the town of Plassey, which is between Calcutta, where the British were based, and Murshidabad, the capital of the kingdom of Bengal. It was in those mango groves that the British forces faced the Nawab Siraj-ud-Doula’s army and convincingly defeated it.

British rule ended nearly 200 years later with Jawaharlal Nehru’s famous speech on India’s “tryst with destiny” at midnight on 14 August 1947. Two hundred years is a long time. What did the British achieve in India, and what did they fail to accomplish?

During my days as a student at a progressive school in West Bengal in the 1940s, these questions came into our discussion constantly. They remain important even today, not least because the British empire is often invoked in discussions about successful global governance. It has also been invoked to try to persuade the US to acknowledge its role as the pre-eminent imperial power in the world today: “Should the United States seek to shed – or to shoulder – the imperial load it has inherited?” the historian Niall Ferguson has asked . It is certainly an interesting question, and Ferguson is right to argue that it cannot be answered without an understanding of how the British empire rose and fell – and what it managed to do.

Arguing about all this at Santiniketan school, which had been established by Rabindranath Tagore some decades earlier, we were bothered by a difficult methodological question. How could we think about what India would have been like in the 1940s had British rule not occurred at all?

The frequent temptation to compare India in 1757 (when British rule was beginning) with India in 1947 (when the British were leaving ) would tell us very little, because in the absence of British rule, India would of course not have remained the same as it was at the time of Plassey. The country would not have stood still had the British conquest not occurred. But how do we answer the question about what difference was made by British rule?

To illustrate the relevance of such an “alternative history”, we may consider another case – one with a potential imperial conquest that did not in fact occur. Let’s think about Commodore Matthew Perry of the US navy, who steamed into the bay of Edo in Japan in 1853 with four warships. Now consider the possibility that Perry was not merely making a show of American strength (as was in fact the case), but was instead the advance guard of an American conquest of Japan, establishing a new American empire in the land of the rising sun, rather as Robert Clive did in India . If we were to assess the achievements of the supposed American rule of Japan through the simple device of comparing Japan before that imperial conquest in 1853 with Japan after the American domination ended, whenever that might be, and attribute all the differences to the effects of the American empire, we would miss all the contributions of the Meiji restoration from 1868 onwards, and of other globalising changes that were going on. Japan did not stand still; nor would India have done so.

While we can see what actually happened in Japan under Meiji rule, it is extremely hard to guess with any confidence what course the history of the Indian subcontinent would have taken had the British conquest not occurred. Would India have moved, like Japan, towards modernisation in an increasingly globalising world, or would it have remained resistant to change, like Afghanistan, or would it have hastened slowly, like Thailand?

These are impossibly difficult questions to answer. And yet, even without real alternative historical scenarios, there are some limited questions that can be answered, which may contribute to an intelligent understanding of the role that British rule played in India. We can ask: what were the challenges that India faced at the time of the British conquest, and what happened in those critical areas during the British rule?

T here was surely a need for major changes in a rather chaotic and institutionally backward India. To recognise the need for change in India in the mid-18th century does not require us to ignore – as many Indian super-nationalists fear – the great achievements in India’s past, with its extraordinary history of accomplishments in philosophy, mathematics, literature, arts, architecture, music, medicine, linguistics and astronomy. India had also achieved considerable success in building a thriving economy with flourishing trade and commerce well before the colonial period – the economic wealth of India was amply acknowledged by British observers such as Adam Smith.

The fact is, nevertheless, that even with those achievements, in the mid-18th century India had in many ways fallen well behind what was being achieved in Europe. The exact nature and significance of this backwardness were frequent subjects of lively debates in the evenings at my school.

An insightful essay on India by Karl Marx particularly engaged the attention of some of us. Writing in 1853, Marx pointed to the constructive role of British rule in India, on the grounds that India needed some radical re-examination and self-scrutiny. And Britain did indeed serve as India’s primary western contact, particularly in the course of the 19th century. The importance of this influence would be hard to neglect. The indigenous globalised culture that was slowly emerging in India was deeply indebted not only to British writing, but also to books and articles in other – that is non-English – European languages that became known in India through the British.

Figures such as the Calcutta philosopher Ram Mohan Roy, born in 1772, were influenced not only by traditional knowledge of Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian texts, but also by the growing familiarity with English writings. After Roy, in Bengal itself there were also Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Madhusudan Dutta and several generations of Tagores and their followers who were re-examining the India they had inherited in the light of what they saw happening in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. Their main – often their only – source of information were the books (usually in English) circulating in India, thanks to British rule. That intellectual influence, covering a wide range of European cultures, survives strongly today, even as the military, political and economic power of the British has declined dramatically.

I was persuaded that Marx was basically right in his diagnosis of the need for some radical change in India, as its old order was crumbling as a result of not having been a part of the intellectual and economic globalisation that the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution had initiated across the world (along with, alas, colonialism).

There was arguably, however, a serious flaw in Marx’s thesis, in particular in his implicit presumption that the British conquest was the only window on the modern world that could have opened for India. What India needed at the time was more constructive globalisation, but that is not the same thing as imperialism. The distinction is important. Throughout India’s long history, it persistently enjoyed exchanges of ideas as well as of commodities with the outside world. Traders, settlers and scholars moved between India and further east – China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand and elsewhere – for a great many centuries, beginning more than 2,000 years ago. The far-reaching influence of this movement – especially on language, literature and architecture – can be seen plentifully even today. There were also huge global influences by means of India’s open-frontier attitude in welcoming fugitives from its early days.

Jewish immigration into India began right after the fall of Jerusalem in the first century and continued for many hundreds of years. Baghdadi Jews, such as the highly successful Sassoons, came in large numbers even as late as the 18th century. Christians started coming at least from the fourth century, and possibly much earlier. There are colourful legends about this, including one that tells us that the first person St Thomas the Apostle met after coming to India in the first century was a Jewish girl playing the flute on the Malabar coast. We loved that evocative – and undoubtedly apocryphal – anecdote in our classroom discussions, because it illustrated the multicultural roots of Indian traditions.

The Parsis started arriving from the early eighth century – as soon as persecution began in their Iranian homeland. Later in that century, the Armenians began to leave their footprints from Kerala to Bengal. Muslim Arab traders had a substantial presence on the west coast of India from around that time – well before the arrival of Muslim conquerors many centuries later, through the arid terrain in the north-west of the subcontinent. Persecuted Bahá’ís from Iran came only in the 19th century.

At the time of the Battle of Plassey, there were already businessmen, traders and other professionals from a number of different European nations well settled near the mouth of the Ganges. Being subjected to imperial rule is thus not the only way of making connections with, or learning things from, foreign countries. When the Meiji Restoration established a new reformist government in Japan in 1868 (which was not unrelated to the internal political impact of Commodore Perry’s show of force a decade earlier), the Japanese went straight to learning from the west without being subjected to imperialism. They sent people for training in the US and Europe, and made institutional changes that were clearly inspired by western experience. They did not wait to be coercively globalised via imperialism.

O ne of the achievements to which British imperial theorists tended to give a good deal of emphasis was the role of the British in producing a united India. In this analysis, India was a collection of fragmented kingdoms until British rule made a country out of these diverse regimes. It was argued that India was previously not one country at all, but a thoroughly divided land mass. It was the British empire, so the claim goes, that welded India into a nation. Winston Churchill even remarked that before the British came, there was no Indian nation. “India is a geographical term. It is no more a united nation than the equator,” he once said.

If this is true, the empire clearly made an indirect contribution to the modernisation of India through its unifying role. However, is the grand claim about the big role of the Raj in bringing about a united India correct? Certainly, when Clive’s East India Company defeated the nawab of Bengal in 1757, there was no single power ruling over all of India. Yet it is a great leap from the proximate story of Britain imposing a single united regime on India (as did actually occur) to the huge claim that only the British could have created a united India out of a set of disparate states.

That way of looking at Indian history would go firmly against the reality of the large domestic empires that had characterised India throughout the millennia. The ambitious and energetic emperors from the third century BC did not accept that their regimes were complete until the bulk of what they took to be one country was united under their rule. There were major roles here for Ashoka Maurya, the Gupta emperors, Alauddin Khalji, the Mughals and others. Indian history shows a sequential alternation of large domestic empires with clusters of fragmented kingdoms. We should therefore not make the mistake of assuming that the fragmented governance of mid-18th century India was the state in which the country typically found itself throughout history, until the British helpfully came along to unite it.

Even though in history textbooks the British were often assumed to be the successors of the Mughals in India, it is important to note that the British did not in fact take on the Mughals when they were a force to be reckoned with. British rule began when the Mughals’ power had declined, though formally even the nawab of Bengal, whom the British defeated, was their subject. The nawab still swore allegiance to the Mughal emperor, without paying very much attention to his dictates. The imperial status of the Mughal authority over India continued to be widely acknowledged even though the powerful empire itself was missing.

When the so-called sepoy mutiny threatened the foundations of British India in 1857, the diverse anti-British forces participating in the joint rebellion could be aligned through their shared acceptance of the formal legitimacy of the Mughal emperor as the ruler of India. The emperor was, in fact, reluctant to lead the rebels, but this did not stop the rebels from declaring him the emperor of all India. The 82-year-old Mughal monarch, Bahadur Shah II, known as Zafar, was far more interested in reading and writing poetry than in fighting wars or ruling India. He could do little to help the 1,400 unarmed civilians of Delhi whom the British killed as the mutiny was brutally crushed and the city largely destroyed. The poet-emperor was banished to Burma, where he died.

As a child growing up in Burma in the 1930s, I was taken by my parents to see Zafar’s grave in Rangoon, which was close to the famous Shwedagon Pagoda. The grave was not allowed to be anything more than an undistinguished stone slab covered with corrugated iron. I remember discussing with my father how the British rulers of India and Burma must evidently have been afraid of the evocative power of the remains of the last Mughal emperor. The inscription on the grave noted only that “Bahadur Shah was ex-King of Delhi” – no mention of “empire” in the commemoration! It was only much later, in the 1990s, that Zafar would be honoured with something closer to what could decently serve as the grave of the last Mughal emperor.

I n the absence of the British Raj, the most likely successors to the Mughals would probably have been the newly emerging Hindu Maratha powers near Bombay, who periodically sacked the Mughal capital of Delhi and exercised their power to intervene across India. Already by 1742, the East India Company had built a huge “Maratha ditch” at the edge of Calcutta to slow down the lightning raids of the Maratha cavalry, which rode rapidly across 1,000 miles or more. But the Marathas were still quite far from putting together anything like the plan of an all-India empire.

The British, by contrast, were not satisfied until they were the dominant power across the bulk of the subcontinent, and in this they were not so much bringing a new vision of a united India from abroad as acting as the successor of previous domestic empires. British rule spread to the rest of the country from its imperial foundations in Calcutta, beginning almost immediately after Plassey. As the company’s power expanded across India, Calcutta became the capital of the newly emerging empire, a position it occupied from the mid-18th century until 1911 (when the capital was moved to Delhi). It was from Calcutta that the conquest of other parts of India was planned and directed. The profits made by the East India Company from its economic operations in Bengal financed, to a great extent, the wars that the British waged across India in the period of their colonial expansion.

What has been called “the financial bleeding of Bengal” began very soon after Plassey. With the nawabs under their control, the company made big money not only from territorial revenues, but also from the unique privilege of duty-free trade in the rich Bengal economy – even without counting the so-called gifts that the Company regularly extracted from local merchants. Those who wish to be inspired by the glory of the British empire would do well to avoid reading Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, including his discussion of the abuse of state power by a “mercantile company which oppresses and domineers in the East Indies”. As the historian William Dalrymple has observed: “The economic figures speak for themselves. In 1600, when the East India Company was founded, Britain was generating 1.8% of the world’s GDP, while India was producing 22.5%. By the peak of the Raj, those figures had more or less been reversed: India was reduced from the world’s leading manufacturing nation to a symbol of famine and deprivation.”

While most of the loot from the financial bleeding accrued to British company officials in Bengal, there was widespread participation by the political and business leadership in Britain: nearly a quarter of the members of parliament in London owned stocks in the East India Company after Plassey. The commercial benefits from Britain’s Indian empire thus reached far into the British establishment.

The robber-ruler synthesis did eventually give way to what would eventually become classical colonialism, with the recognition of the need for law and order and a modicum of reasonable governance. But the early misuse of state power by the East India Company put the economy of Bengal under huge stress. What the cartographer John Thornton, in his famous chart of the region in 1703, had described as “the Rich Kingdom of Bengal” experienced a gigantic famine during 1769–70. Contemporary estimates suggested that about a third of the Bengal population died. This is almost certainly an overestimate. There was no doubt, however, that it was a huge catastrophe, with massive starvation and mortality – in a region that had seen no famine for a very long time.

This disaster had at least two significant effects. First, the inequity of early British rule in India became the subject of considerable political criticism in Britain itself. By the time Adam Smith roundly declared in The Wealth of Nations that the East India Company was “altogether unfit to govern its territorial possessions”, there were many British figures, such as Edmund Burke, making similar critiques. Second, the economic decline of Bengal did eventually ruin the company’s business as well, hurting British investors themselves, and giving the powers in London reason to change their business in India into more of a regular state-run operation.

By the late 18th century, the period of so-called “post-Plassey plunder”, with which British rule in India began, was giving way to the sort of colonial subjugation that would soon become the imperial standard, and with which the subcontinent would become more and more familiar in the following century and a half.

H ow successful was this long phase of classical imperialism in British India, which lasted from the late 18th century until independence in 1947? The British claimed a huge set of achievements, including democracy, the rule of law, railways, the joint stock company and cricket, but the gap between theory and practice – with the exception of cricket – remained wide throughout the history of imperial relations between the two countries. Putting the tally together in the years of pre-independence assessment, it was easy to see how far short the achievements were compared with the rhetoric of accomplishment.

Indeed, Rudyard Kipling caught the self-congratulatory note of the British imperial administrator admirably well in his famous poem on imperialism:

Take up the White Man’s burden – The savage wars of peace – Fill full the mouth of famine And bid the sickness cease

Alas, neither the stopping of famines nor the remedying of ill health was part of the high-performance achievements of British rule in India. Nothing could lead us away from the fact that life expectancy at birth in India as the empire ended was abysmally low: 32 years, at most.

The abstemiousness of colonial rule in neglecting basic education reflects the view taken by the dominant administrators of the needs of the subject nation. There was a huge asymmetry between the ruler and the ruled. The British government became increasingly determined in the 19th century to achieve universal literacy for the native British population. In contrast, the literacy rates in India under the Raj were very low. When the empire ended, the adult literacy rate in India was barely 15%. The only regions in India with comparatively high literacy were the “native kingdoms” of Travancore and Cochin (formally outside the British empire), which, since independence, have constituted the bulk of the state of Kerala. These kingdoms, though dependent on the British administration for foreign policy and defence, had remained technically outside the empire and had considerable freedom in domestic policy, which they exercised in favour of more school education and public health care.

The 200 years of colonial rule were also a period of massive economic stagnation, with hardly any advance at all in real GNP per capita. These grim facts were much aired after independence in the newly liberated media, whose rich culture was in part – it must be acknowledged – an inheritance from British civil society. Even though the Indian media was very often muzzled during the Raj – mostly to prohibit criticism of imperial rule, for example at the time of the Bengal famine of 1943 – the tradition of a free press, carefully cultivated in Britain, provided a good model for India to follow as the country achieved independence.

Indeed, India received many constructive things from Britain that did not – could not – come into their own until after independence. Literature in the Indian languages took some inspiration and borrowed genres from English literature, including the flourishing tradition of writing in English. Under the Raj, there were restrictions on what could be published and propagated (even some of Tagore’s books were banned). These days the government of India has no such need, but alas – for altogether different reasons of domestic politics – the restrictions are sometimes no less intrusive than during the colonial rule.

Nothing is perhaps as important in this respect as the functioning of a multiparty democracy and a free press. But often enough these were not gifts that could be exercised under the British administration during imperial days. They became realisable only when the British left – they were the fruits of learning from Britain’s own experience, which India could use freely only after the period of empire had ended. Imperial rule tends to require some degree of tyranny: asymmetrical power is not usually associated with a free press or with a vote-counting democracy, since neither of them is compatible with the need to keep colonial subjects in check.

A similar scepticism is appropriate about the British claim that they had eliminated famine in dependent territories such as India. British governance of India began with the famine of 1769-70, and there were regular famines in India throughout the duration of British rule. The Raj also ended with the terrible famine of 1943. In contrast, there has been no famine in India since independence in 1947.

The irony again is that the institutions that ended famines in independent India – democracy and an independent media – came directly from Britain. The connection between these institutions and famine prevention is simple to understand. Famines are easy to prevent, since the distribution of a comparatively small amount of free food, or the offering of some public employment at comparatively modest wages (which gives the beneficiaries the ability to buy food), allows those threatened by famine the ability to escape extreme hunger. So any government should be able stop a threatening famine – large or small – and it is very much in the interest of a government in a functioning democracy, facing a free press, to do so. A free press makes the facts of a developing famine known to all, and a democratic vote makes it hard to win elections during – or after – a famine, hence giving a government the additional incentive to tackle the issue without delay.

India did not have this freedom from famine for as long as its people were without their democratic rights, even though it was being ruled by the foremost democracy in the world, with a famously free press in the metropolis – but not in the colonies. These freedom-oriented institutions were for the rulers but not for the imperial subjects.

In the powerful indictment of British rule in India that Tagore presented in 1941, he argued that India had gained a great deal from its association with Britain, for example, from “discussions centred upon Shakespeare’s drama and Byron’s poetry and above all … the large-hearted liberalism of 19th-century English politics”. The tragedy, he said, came from the fact that what “was truly best in their own civilisation, the upholding of dignity of human relationships, has no place in the British administration of this country”. Indeed, the British could not have allowed Indian subjects to avail themselves of these freedoms without threatening the empire itself.

The distinction between the role of Britain and that of British imperialism could not have been clearer. As the union jack was being lowered across India, it was a distinction of which we were profoundly aware.

Adapted from Home in the World: A Memoir by Amartya Sen, published by Allen Lane on 8 July and available at guardianbookshop.com

This article was amended on 29 June 2021. Owing to an editing error, an earlier version incorrectly referred to Karl Marx writing on India in 1953. The essay was written in 1853.

- The long read

- British empire

- Colonialism

- History books

Most viewed

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857

Aftermath of the mutiny, government of india act of 1858, social policy, government organization, economic policy and development, the northwest frontier, the second anglo-afghan war, the incorporation of burma, origins of the nationalist movement, the early congress movement, the first partition of bengal, nationalism in the muslim community, reforms of the british liberals, moderate and militant nationalism, india’s contributions to the war effort, anti-british activity, the postwar years, jallianwala bagh massacre at amritsar.

- Gandhi’s philosophy and strategy

Constitutional reforms

The congress’s ambivalent strategy, muslim separatism, the impact of world war ii, british wartime strategy, the transfer of power and the birth of two countries.

- Who was Mangal Pandey?

- What did Gandhi try to accomplish with his activism?

- What were Gandhi’s religious beliefs?

- What other social movements did Gandhi’s activism inspire?

- What was Gandhi’s personal life like?

British raj

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Humanities LibreTexts - British Raj

- Association for Asian Studies - Education About Asia: Online Archives - The British Impact on India, 1700–1900

- Georgetown University - Berkley Center - The British Raj and the Present

- GlobalSecurity.org - 1858-1947 - British Raj

- Table Of Contents

British raj , period of direct British rule over the Indian subcontinent from 1858 until the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947. The raj succeeded management of the subcontinent by the British East India Company , after general distrust and dissatisfaction with company leadership resulted in a widespread mutiny of sepoy troops in 1857, causing the British to reconsider the structure of governance in India. The British government took possession of the company’s assets and imposed direct rule. The raj was intended to increase Indian participation in governance, but the powerlessness of Indians to determine their own future without the consent of the British led to an increasingly adamant national independence movement.

Though trade with India had been highly valued by Europeans since ancient times, the long route between them was subject to many potential obstacles and obfuscations from middlemen, making trade unsafe, unreliable, and expensive. This was especially true after the collapse of the Mongol empire and the rise of the Ottoman Empire all but blocked the ancient Silk Road . As Europeans, led by the Portuguese, began to explore maritime navigation routes to bypass middlemen, the distance of the venture required merchants to set up fortified posts.

The British entrusted this task to the East India Company, which initially established itself in India by obtaining permission from local authorities to own land, fortify its holdings, and conduct trade duty-free in mutually beneficial relationships. The company’s territorial paramountcy began after it became involved in hostilities, sidelining rival European companies and eventually overthrowing the nawab of Bengal and installing a puppet in 1757. The company’s control over Bengal was effectively consolidated in the 1770s when Warren Hastings brought the nawab’s administrative offices to Calcutta (now Kolkata ) under his oversight. About the same time, the British Parliament began regulating the East India Company through successive India Acts , bringing Bengal under the indirect control of the British government. Over the next eight decades, a series of wars, treaties, and annexations extended the dominion of the company across the subcontinent, subjugating most of India to the determination of British governors and merchants.

In late March 1857 a sepoy (Indian soldier) in the employ of the East India Company named Mangal Pandey attacked British officers at the military garrison in Barrackpore . He was arrested and then executed by the British in early April. Later in April sepoy troopers at Meerut , having heard a rumour that they would have to bite cartridges that had been greased with the lard of pigs and cows (forbidden for consumption by Muslims and Hindus, respectively) to ready them for use in their new Enfield rifles, refused the cartridges. As punishment, they were given long prison terms, fettered, and put in jail. This punishment incensed their comrades, who rose on May 10, shot their British officers, and marched to Delhi , where there were no European troops. There the local sepoy garrison joined the Meerut men, and by nightfall the aged pensionary Mughal emperor Bahādur Shah II had been nominally restored to power by a tumultuous soldiery. The seizure of Delhi provided a focus and set the pattern for the whole mutiny, which then spread throughout northern India. With the exception of the Mughal emperor and his sons and Nana Sahib , the adopted son of the deposed Maratha peshwa , none of the important Indian princes joined the mutineers. The mutiny officially came to an end on July 8, 1859.

The immediate result of the mutiny was a general housecleaning of the Indian administration. The East India Company was abolished in favour of the direct rule of India by the British government. In concrete terms, this did not mean much, but it introduced a more personal note into the government and removed the unimaginative commercialism that had lingered in the Court of Directors. The financial crisis caused by the mutiny led to a reorganization of the Indian administration’s finances on a modern basis. The Indian army was also extensively reorganized.

Another significant result of the mutiny was the beginning of the policy of consultation with Indians. The Legislative Council of 1853 had contained only Europeans and had arrogantly behaved as if it were a full-fledged parliament. It was widely felt that a lack of communication with Indian opinion had helped to precipitate the crisis. Accordingly, the new council of 1861 was given an Indian-nominated element. The educational and public works programs (roads, railways, telegraphs, and irrigation) continued with little interruption; in fact, some were stimulated by the thought of their value for the transport of troops in a crisis. But insensitive British-imposed social measures that affected Hindu society came to an abrupt end.

Finally, there was the effect of the mutiny on the people of India themselves. Traditional society had made its protest against the incoming alien influences, and it had failed. The princes and other natural leaders had either held aloof from the mutiny or had proved, for the most part, incompetent. From this time all serious hope of a revival of the past or an exclusion of the West diminished. The traditional structure of Indian society began to break down and was eventually superseded by a Westernized class system, from which emerged a strong middle class with a heightened sense of Indian nationalism .

(For more on the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, see also Indian Mutiny and the discussion of the mutiny in India .)

British rule

Establishment of direct british governance.

Much of the blame for the mutiny fell on the ineptitude of the East India Company. On August 2, 1858, Parliament passed the Government of India Act , transferring British power over India from the company to the crown. The merchant company’s residual powers were vested in the secretary of state for India, a minister of Great Britain’s cabinet, who would preside over the India Office in London and be assisted and advised, especially in financial matters, by a Council of India , which consisted initially of 15 Britons, 7 of whom were elected from among the old company’s court of directors and 8 of whom were appointed by the crown. Though some of Britain’s most powerful political leaders became secretaries of state for India in the latter half of the 19th century, actual control over the government of India remained in the hands of British viceroys—who divided their time between Calcutta ( Kolkata ) and Simla ( Shimla )—and their “steel frame” of approximately 1,500 Indian Civil Service (ICS) officials posted “on the spot” throughout British India.

On November 1, 1858, Lord Canning (governed 1856–62) announced Queen Victoria ’s proclamation to “the Princes, Chiefs and Peoples of India,” which unveiled a new British policy of perpetual support for “native princes” and nonintervention in matters of religious belief or worship within British India. The announcement reversed Lord Dalhousie ’s prewar policy of political unification through princely state annexation, and princes were left free to adopt any heirs they desired so long as they all swore undying allegiance to the British crown. In 1876, at the prompting of Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli , Queen Victoria added the title Empress of India to her regality. British fears of another mutiny and consequent determination to bolster Indian states as “natural breakwaters” against any future tidal wave of revolt thus left more than 560 enclaves of autocratic princely rule to survive, interspersed throughout British India, for the entire nine decades of crown rule. The new policy of religious nonintervention was born equally out of fear of recurring mutiny, which many Britons believed had been triggered by orthodox Hindu and Muslim reaction against the secularizing inroads of utilitarian positivism and the proselytizing of Christian missionaries . British liberal socioreligious reform therefore came to a halt for more than three decades—essentially from the East India Company’s Hindu Widow’s Remarriage Act of 1856 to the crown’s timid Age of Consent Act of 1891, which merely raised the age of statutory rape for “consenting” Indian brides from 10 years to 12.

The typical attitude of British officials who went to India during that period was, as the English writer Rudyard Kipling put it, to “take up the white man’s burden.” By and large, throughout the interlude of their Indian service to the crown , Britons lived as super-bureaucrats, “Pukka Sahibs,” remaining as aloof as possible from “native contamination” in their private clubs and well-guarded military cantonments (called camps), which were constructed beyond the walls of the old, crowded “native” cities in that era. The new British military towns were initially erected as secure bases for the reorganized British regiments and were designed with straight roads wide enough for cavalry to gallop through whenever needed. The old company’s three armies (located in Bengal , Bombay [ Mumbai ], and Madras [ Chennai ]), which in 1857 had only 43,000 British to 228,000 native troops, were reorganized by 1867 to a much “safer” mix of 65,000 British to 140,000 Indian soldiers. Selective new British recruitment policies screened out all “nonmartial” (meaning previously disloyal) Indian castes and ethnic groups from armed service and mixed the soldiers in every regiment, thus permitting no single caste or linguistic or religious group to again dominate a British Indian garrison. Indian soldiers were also restricted from handling certain sophisticated weaponry.

After 1869, with the completion of the Suez Canal and the steady expansion of steam transport reducing the sea passage between Britain and India from about three months to only three weeks, British women came to the East with ever greater alacrity , and the British officials they married found it more appealing to return home with their British wives during furloughs than to tour India as their predecessors had done. While the intellectual calibre of British recruits to the ICS in that era was, on the average, probably higher than that of servants recruited under the company’s earlier patronage system, British contacts with Indian society diminished in every respect (fewer British men, for example, openly consorted with Indian women), and British sympathy for and understanding of Indian life and culture were, for the most part, replaced by suspicion, indifference, and fear.

Queen Victoria’s 1858 promise of racial equality of opportunity in the selection of civil servants for the government of India had theoretically thrown the ICS open to qualified Indians, but examinations for the services were given only in Britain and only to male applicants between the ages of 17 and 22 (in 1878 the maximum age was further reduced to 19) who could stay in the saddle over a rigorous series of hurdles. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that by 1869 only one Indian candidate had managed to clear those obstacles to win a coveted admission to the ICS. British royal promises of equality were thus subverted in actual implementation by jealous, fearful bureaucrats posted “on the spot.”

From 1858 to 1909 the government of India was an increasingly centralized paternal despotism and the world’s largest imperial bureaucracy . The Indian Councils Act of 1861 transformed the viceroy’s Executive Council into a miniature cabinet run on the portfolio system, and each of the five ordinary members was placed in charge of a distinct department of Calcutta’s government—home, revenue, military, finance, and law. The military commander in chief sat with that council as an extraordinary member. A sixth ordinary member was assigned to the viceroy’s Executive Council after 1874, initially to preside over the Department of Public Works, which after 1904 came to be called Commerce and Industry. Though the government of India was by statutory definition the “Governor-General-in-Council” ( governor-general remained the viceroy’s alternate title), the viceroy was empowered to overrule his councillors if ever he deemed that necessary. He personally took charge of the Foreign Department, which was mostly concerned with relations with princely states and bordering foreign powers. Few viceroys found it necessary to assert their full despotic authority, since the majority of their councillors usually were in agreement. In 1879, however, Viceroy Lytton (governed 1876–80) felt obliged to overrule his entire council in order to accommodate demands for the elimination of his government’s import duties on British cotton manufactures, despite India’s desperate need for revenue in a year of widespread famine and agricultural disorders.

From 1854 additional members met with the viceroy’s Executive Council for legislative purposes, and by the act of 1861 their permissible number was raised to between 6 and 12, no fewer than half of whom were to be nonofficial. While the viceroy appointed all such legislative councillors and was empowered to veto any bill passed on to him by that body, its debates were to be open to a limited public audience, and several of its nonofficial members were Indian nobility and loyal landowners. For the government of India the legislative council sessions thus served as a crude public-opinion barometer and the beginnings of an advisory “safety valve” that provided the viceroy with early crisis warnings at the minimum possible risk of parliamentary-type opposition. The act of 1892 further expanded the council’s permissible additional membership to 16, of whom 10 could be nonofficial, and increased their powers, though only to the extent of allowing them to ask questions of government and to criticize formally the official budget during one day reserved for that purpose at the very end of each year’s legislative session in Calcutta. The Supreme Council, however, still remained quite remote from any sort of parliament.

Economically, it was an era of increased commercial agricultural production, rapidly expanding trade, early industrial development, and severe famine . The total cost of the mutiny of 1857–59, which was equivalent to a normal year’s revenue, was charged to India and paid off from increased revenue resources in four years. The major source of government income throughout that period remained the land revenue, which, as a percentage of the agricultural yield of India’s soil, continued to be “an annual gamble in monsoon rains.” Usually, however, it provided about half of British India’s gross annual revenue, or roughly the money needed to support the army. The second most lucrative source of revenue at that time was the government’s continued monopoly over the flourishing opium trade to China; the third was the tax on salt, also jealously guarded by the crown as its official monopoly preserve. An individual income tax was introduced for five years to pay off the war deficit, but urban personal income was not added as a regular source of Indian revenue until 1886.

Despite continued British adherence to the doctrine of laissez-faire during that period, a 10 percent customs duty was levied in 1860 to help clear the war debt, though it was reduced to 7 percent in 1864 and to 5 percent in 1875. The above-mentioned cotton import duty, abolished in 1879 by Viceroy Lytton, was not reimposed on British imports of piece goods and yarn until 1894, when the value of silver fell so precipitously on the world market that the government of India was forced to take action, even against the economic interests of the home country (i.e., textiles in Lancashire), by adding enough rupees to its revenue to make ends meet. Bombay’s textile industry had by then developed more than 80 power mills, and the huge Empress Mill owned by Indian industrialist Jamsetji (Jamshedji) N. Tata (1839–1904) was in full operation at Nagpur , competing directly with Lancashire mills for the vast Indian market. Britain’s mill owners again demonstrated their power in Calcutta by forcing the government of India to impose an “equalizing” 5 percent excise tax on all cloth manufactured in India, thereby convincing many Indian mill owners and capitalists that their best interests would be served by contributing financial support to the Indian National Congress .

Britain’s major contribution to India’s economic development throughout the era of crown rule was the railroad network that spread so swiftly across the subcontinent after 1858, when there were barely 200 miles (320 km) of track in all of India. By 1869 more than 5,000 miles (8,000 km) of steel track had been completed by British railroad companies, and by 1900 there were some 25,000 miles (40,000 km) of rail laid. By the start of World War I (1914–18) the total had reached 35,000 miles (56,000 km), almost the full growth of British India’s rail net. Initially, the railroads proved a mixed blessing for most Indians, since, by linking India’s agricultural, village-based heartland to the British imperial port cities of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta, they served both to accelerate the pace of raw-material extraction from India and to speed up the transition from subsistence food to commercial agricultural production. Middlemen hired by port-city agency houses rode the trains inland and induced village headmen to convert large tracts of grain-yielding land to commercial crops.

Large sums of silver were offered in payment for raw materials when the British demand was high, as was the case throughout the American Civil War (1861–65), but, after the Civil War ended, restoring raw cotton from the southern United States to Lancashire mills, the Indian market collapsed. Millions of peasants weaned from grain production now found themselves riding the boom-and-bust tiger of a world-market economy. They were unable to convert their commercial agricultural surplus back into food during depression years, and from 1865 through 1900 India experienced a series of protracted famines, which in 1896 was complicated by the introduction of bubonic plague (spread from Bombay, where infected rats were brought from China). As a result, though the population of the subcontinent increased dramatically from about 200 million in 1872 (the year of the first almost universal census) to more than 319 million in 1921, the population may have declined slightly between 1895 and 1905.

The spread of railroads also accelerated the destruction of India’s indigenous handicraft industries, for trains filled with cheap competitive manufactured goods shipped from England now rushed to inland towns for distribution to villages, underselling the rougher products of Indian craftsmen. Entire handicraft villages thus lost their traditional markets of neighbouring agricultural villagers, and craftsmen were forced to abandon their looms and spinning wheels and return to the soil for their livelihood. By the end of the 19th century a larger proportion of India’s population (perhaps more than three-fourths) depended directly on agriculture for support than at the century’s start, and the pressure of population on arable land increased throughout that period. Railroads also provided the military with swift and relatively assured access to all parts of the country in the event of emergency and were eventually used to transport grain for famine relief as well.

The rich coalfields of Bihar began to be mined during that period to help power the imported British locomotives, and coal production jumped from roughly 500,000 tons in 1868 to some 6,000,000 tons in 1900 and more than 20,000,000 tons by 1920. Coal was used for iron smelting in India as early as 1875, but the Tata Iron and Steel Company (now part of the Tata Group ), which received no government aid, did not start production until 1911, when, in Bihar, it launched India’s modern steel industry. Tata grew rapidly after World War I, and by World War II it had become the largest single steel complex in the British Commonwealth . The jute textile industry, Bengal’s counterpart to Bombay’s cotton industry, developed in the wake of the Crimean War (1853–56), which, by cutting off Russia’s supply of raw hemp to the jute mills of Scotland, stimulated the export of raw jute from Calcutta to Dundee. In 1863 there were only two jute mills in Bengal, but by 1882 there were 20, employing more than 20,000 workers.

The most important plantation industries of the era were tea, indigo, and coffee. British tea plantations were started in northern India’s Assam Hills in the 1850s and in southern India’s Nilgiri Hills some 20 years later. By 1871 there were more than 300 tea plantations, covering in excess of 30,000 cultivated acres (12,000 hectares) and producing some 3,000 tons of tea. By 1900 India’s tea crop was large enough to export 68,500 tons to Britain, displacing the tea of China in London. The flourishing indigo industry of Bengal and Bihar was threatened with extinction during the “Blue Mutiny” (violent riots by cultivators in 1859–60), but India continued to export indigo to European markets until the end of the 19th century, when synthetic dyes made that natural product obsolete. Coffee plantations flourished in southern India from 1860 to 1879, after which disease blighted the crop and sent Indian coffee into a decade of decline.

Foreign policy