What Is The Importance Of Family Unity In Modern Society?

With advancements in technology, changing cultural norms, new priorities, and advanced forms of communication fueled by the internet, you may wonder how family holds up in modern society. The concept of family is likely to continue to be essential for people from all walks of life, despite changing beliefs and customs. Research often demonstrates the importance of family for numerous areas of well-being . No matter how much life changes and the concept of family evolves, it may continue to benefit human health and wellness by offering a sense of belonging and support. If you’re experiencing family-related challenges, it can be helpful to speak to an objective person, such as a licensed therapist, for insight and guidance.

Its definition may evolve, but family may remain essential

The traditional definition of a "nuclear family" typically entailed one man and one woman who were married and had biological children. However, today’s families can be more inclusive and may look different than family stereotypes. Additionally, research usually labels many different types of families.

Benefits of a healthy family

As modern life can add pressure and stress, a healthy family dynamic can have multiple benefits, regardless of whether it's a biological family, adoptive family, or chosen family.

Helps you meet your basic needs

Many years ago, Abraham Maslow created the Hierarchy of Needs . At the bottom of this hierarchy are usually basic needs, including water, food, rest, and health. A family may provide these necessities, which can serve as building blocks for other needs.

Research also suggests that social connection can be considered a need, as it usually improves physical and mental health. Family may offer social connection in abundance.

Allows you to belong to something and foster a sense of unity

A sense of belonging can come from the family, group, or community we belong to, and it can contribute to our emotional well-being by allowing us to feel connected socially.

Offers an important built-in support system and promotes family connection

Research shows that the support system families provide can have a profound impact throughout different stages of life. Difficult times are often inevitable, but a family may provide a sense of stability and connection that can make it easier to get through them.

A family bond contributes to health

Children might experience a healthy lifestyle when they live in a healthy family. They may eat healthy meals, enjoy time outdoors, and get prompt medical attention when needed.

Health benefits can exist for parents in families, too. Research has shown that people with children in their families tend to live longer , even after the children have grown up and moved away.

Families provide support when someone is ill

Facing medical problems alone can be challenging. A family may help alleviate this difficulty by offering support and assistance as you heal.

Offers community benefits by reinforcing family values.

A strong family structure may reduce the likelihood of delinquency and crime. This can mean that the family unit may substantially impact an individual and their community.

The importance of family and love in educating children

One way many parents contribute to society is by educating their children. Parents and caregivers often begin teaching children at a very young age. They may help them learn to walk and teach them new words as they develop their vocabulary and language skills. They also may teach them manners and take advantage of learning opportunities in everyday life.

Many parents also encourage scholarship opportunities, ethical behavior, and social skills that can benefit children throughout adolescence and into adulthood.

All families may struggle sometimes

Even though families can have benefits, they may face challenges at times. When it comes to overcoming the difficulties of family life, you might find support in your friends. You can also seek the help of a professional with training and experience in family dynamics.

Seeking help

Talking to a therapist may help you explore your feelings about family and learn to express those feelings openly. You may also learn to understand the family influences that shaped your personality.

Benefits of online therapy in enhancing family relationships

Online therapy can be an easy and convenient way to receive insight and guidance from a licensed therapist. It can be helpful to vent to an objective person during therapy sessions, and you can attend these sessions from any location with an internet connection. With an online therapy platform, you can even seek out a therapist who specializes in helping their clients navigate family-related concerns.

Effectiveness of online therapy

Although more research may be needed regarding the efficacy of individual online therapy for addressing family-related challenges, a growing body of evidence generally supports the idea that online therapy can be just as effective as face-to-face therapy.

What is the importance of a family bond in life?

Family can often serve as a cornerstone of our emotional support system, playing a role in each individual's emotional health. This foundational element often sets the stage for future relationships and helps build self-esteem.

What is the importance of family connection to a person?

Family can provide unconditional love and emotional support, which are key factors in building an individual's self-esteem. These early relationships set the groundwork for personal relationships and adult life.

What are 10 important aspects of family in your life?

- Emotional support: Family offers a safety net for emotional well-being.

- Unconditional love: The love from family is often lifelong and uncompromising.

- Moral and ethical guidance: Family serves as our first role model, teaching us social skills and crucial role values.

- Financial support: Financial stability often starts with family support.

- Educational support: Family’s involvement can positively impact academic performance.

- Healthy families: A supportive family environment can contribute to healthy relationships.

- Family traditions and history: Knowing your family history adds a sense of belonging.

- Role models: Family provides the first role models in a child’s life.

- Open communication: Communication within the family contributes to emotional health and strong personal relationships.

- Sense of belonging: Family gatherings, such as family meals, add to the sense of community.

Why are family relationships among the most important support we will ever have?

Family relationships can lay the foundation for how we manage future relationships. The skills learned in the family context are applied to personal relationships in adult life, playing an important role in our overall emotional well-being.

What are the most important values in your relationships as a family?

Important values, like unconditional love and open communication, can form the bedrock on which the emotional health of each individual in the family is built. These values often lead to a unified family, increasing senses of security, stability and support.

What is important in life: family or love?

Family often provides the first experience of unconditional love, and this foundational emotional support sets the tone for what we seek in other personal relationships throughout adult life.

Is having a family the most important thing?

Having a family often offers emotional support and unconditional love, serving as an individual’s foundational support system and playing a crucial role in emotional health. However, many aspects of life are important, and family is not necessarily more important than other relationships in your life.

Why is family more important than happiness?

Family often serves as a significant source of happiness, fulfilling our needs for emotional support and unconditional love.

What is the importance of family unity?

Family unity offers a conducive environment for emotional health and well-being. This unity is often fostered through open communication during family meals, contributing to each individual's ability to maintain relationships.

What brings unity to the family?

Common values and open communication are key factors that bring family unity. Family meals and traditions also play a part, serving as regular platforms for them to express emotional support and unconditional love.

- What Is Family Support? Understanding Services Available To You Medically reviewed by Laura Angers Maddox , NCC, LPC

- Is Sibling Rivalry Normal? How Conflict Between Siblings Works Medically reviewed by Elizabeth Erban , LMFT, IMH-E

- Relationships and Relations

- Unsubscribe

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Creating Cohesion: The Foundations Of Family Unity

- by Relationship Mag

- August 14, 2023 May 17, 2024

Unity within a family forms the bedrock upon which all other facets of social, emotional, and psychological well-being are built. It’s not just about being in the same family tree; it’s about fostering an environment of mutual respect, open communication, shared experiences, and unwavering support. This post explores the foundations of family unity, illustrating how it can be cultivated and strengthened. Each section provides an in-depth discussion of key elements and practical implementation strategies. The objective is to provide an insightful guide to fortify the pillars of unity within every family, fostering healthier, happier, and more fulfilling familial relationships.

- 1 Understanding Family Unity

- 2 The Role of Communication

- 3 Building Trust and Respect

- 4 The Value of Shared Experiences

- 5 Conflict Resolution Skills

- 6 Nurturing a Positive Family Culture

- 7 The Significance of Love and Affection

- 8 The Bottom Line

Understanding Family Unity

Family unity is the bond that ties a family together; the sense of support and love gives each member the confidence to face life’s challenges. This unity does not come from genetic connections or shared living spaces; it emanates from understanding, respect, shared values, and mutual support. When a family is united, it can effectively weather any storm, supporting each member in times of hardship and celebrating together in times of joy.

Understanding why family unity is essential is the first step in fostering it. It promotes emotional health, creates a supportive environment, and offers a sense of belonging. A united family can significantly impact children’s development, providing a solid foundation for emotional, cognitive, and social growth. It offers a blueprint for interacting with the world, negotiating conflicts, and forming healthy relationships. It offers adults a supportive network, mutual understanding, and a haven of comfort and love.

The Role of Communication

Communication forms the lifeblood of any relationship, and within a family , it plays an instrumental role in fostering unity. Open and honest communication allows family members to understand each other’s thoughts, feelings, needs, and desires. It paves the way for empathy and support, creating an environment where each member feels heard and valued.

However, effective communication is not a naturally occurring phenomenon in every family. It requires deliberate effort and, occasionally, the breakdown of barriers that hinder open discussions. Such barriers could range from a generational gap, language differences, or emotional barriers rooted in past conflicts or misunderstandings. Overcoming these challenges can involve establishing regular family meetings, active listening exercises, and encouraging open discussions about feelings and experiences.

Building Trust and Respect

Trust and respect are the cornerstone of any solid relationship, and within the family unit, these elements are paramount. Trust offers safety and predictability, while respect acknowledges each member’s individuality and inherent value. They create a nurturing environment where family members can grow and flourish.

Cultivating trust and respect within a family involves honesty, reliability, and empathy. Keeping promises, acknowledging emotions, validating each other’s experiences, and demonstrating consistent behavior are practical ways to foster these elements. They build individual self-esteem and contribute to a stronger, more unified family dynamic. The interplay between trust and respect significantly impacts cohesion and overall harmony within the family.

The Value of Shared Experiences

Shared experiences play a significant role in the construction of family unity. They are the threads that weave together the fabric of familial relationships, strengthening the bond between family members. From everyday activities like shared meals and bedtime stories to special occasions like vacations or holidays, these moments form a tapestry of memories that foster a deep sense of belonging.

Although these experiences are invaluable, they must not be grandiose or expensive. It could be as simple as a weekly game night, family cooking sessions, or watching a movie together. The critical factor is sharing time, emotions, and experiences. These create shared memories, which are a powerful bonding agent. Over time, these shared experiences foster mutual understanding, shared values, and collective identity, essential elements of family unity.

Conflict Resolution Skills

Even in the most unified families, conflict is inevitable. Differences in opinions, miscommunications, or clashing personalities can lead to disagreements. However, managing these conflicts can significantly impact the family’s unity. Therefore, effective conflict resolution skills are essential in maintaining harmony and fostering understanding within the family.

These skills include patience, active listening, empathy, and compromise. They help family members navigate disagreements respectfully and constructively, ensuring that conflicts become opportunities for growth rather than sources of division. These skills involve acknowledging and respecting different viewpoints, expressing emotions honestly, and working towards a mutually agreeable resolution. Family members learn to understand and appreciate each other more, fostering a stronger bond and more profound unity.

Nurturing a Positive Family Culture

A positive family culture is one where every member feels valued, loved, and accepted. It’s an environment that promotes mutual support, encourages individual growth, and nurtures positive values. This culture significantly contributes to family unity, setting the tone for interactions, influencing family dynamics, and shaping the overall family identity.

Creating such a culture may involve setting family values, fostering open communication, demonstrating love and respect, and encouraging individuality. It requires consistent effort from all members and a commitment to nurturing a supportive, loving, and positive environment. A positive family culture not only makes the family a haven of love and support but also significantly enhances the unity and cohesion of the family.

The Significance of Love and Affection

At the heart of family unity lies love and affection. These emotions form the foundation of the family bond, creating a sense of belonging and acceptance. Expressions of love and affection—whether verbal affirmations, acts of service, quality time, or physical touch—further strengthen this bond, fostering unity within the family.

However, expressing love and affection may not always be straightforward. Sometimes, emotional barriers, busy schedules, or simply not knowing how to express these feelings can stand in the way. Overcoming these challenges requires understanding each member’s love language, setting aside dedicated time for family, and fostering an environment where expressing emotions is encouraged and valued. By doing so, love and affection become the glue that holds the family together, fostering a profound sense of unity.

The Bottom Line

Family unity is the harmonious blend of mutual respect, open communication, shared experiences, conflict resolution skills, positive culture, and love. These elements contribute to creating an environment of support, acceptance, and belonging—forming the pillars of family unity. While each family is unique, and the path to unity may differ, the foundations remain the same. Implementing these strategies and nurturing these foundations can help foster unity within every family, ultimately creating healthier, happier, and more fulfilling familial relationships. In the grand tapestry of life, family unity forms the vibrant threads that hold everything together, a testament to its enduring power and immeasurable importance.

Related Posts

Preparing for the Emotional Impact of Empty Nest Syndrome

- July 29, 2024 July 29, 2024

Empty Nest Syndrome (ENS) is a complex emotional response that many parents face as their children grow up and leave home. This transitional phase can…

Overcoming Challenges In Multigenerational Families

- March 12, 2024 May 17, 2024

In today’s society, multigenerational living is becoming increasingly common, with families spanning grandparents, parents, and children under one roof. While offering numerous benefits such as…

Coping With Loss: Grieving And Healing As A Family

- February 27, 2024 May 17, 2024

Loss is an inevitable part of life, yet it strikes each individual and family uniquely. The journey through grief, marked by a myriad of emotions…

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

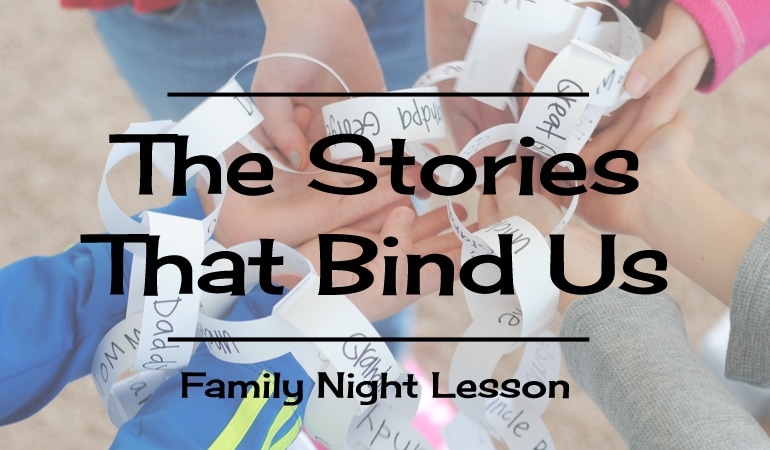

Understanding The Importance Of Family Traditions And 5 Traditions You Should Embrace

Mark Garcia

Table of Contents

- What Are Family Traditions?

What Is The Importance Of Family Traditions?

5 unique family traditions you can practice, a word from mind family, frequently asked questions (faqs).

Family customs are not just mere rituals or routines, they are the lifeblood of family ties that make our lives richer by creating a sense of continuity, identity, and communal joy.

The importance of family traditions is that it is typically passed from one generation to another, form an integral part of the fabric of family life. From grand holiday celebrations to simple daily routines, family traditions create a sense of belonging, instill values, and foster lasting memories.

In this article, we look at the significance of family traditions and present five distinctive actions that can unite families forever bonding them through time.

What Are Family Traditions?

Family traditions are the customs and habits a family creates and maintains over time, often passing them from generation to generation. These can be any activity that brings them together, makes them feel as one, and gives them memories.

Frequently celebrated holidays have different importance of family traditions associated with them. For example, during Christmas families decorate trees and bake cookies before exchanging gifts under the tree or attending religious services.

Thanksgiving is usually centered around cooking a large meal to share with others while expressing gratitude for what they have and watching football afterward. Easter tends to involve egg hunts in the morning followed by church services then ending with a family brunch. In contrast, Hanukkah usually consists of lighting candles on the menorah each night for eight nights straight.

Families highly value less frequent but still important daily or weekly practices. Some examples include eating dinner as a family every night, having Sunday brunch together each week, or even just ordering pizza once every Friday night without fail.

Other routines might consist of telling bedtime stories every night before going to sleep as well as playing board games together every Saturday evening after dinner when everyone has free time. Special phrases such as saying grace before meals or sharing best and worst parts about their day everyday also help hold families closer together.

Family traditions hold great significance for many reasons. They contribute towards the general wellbeing and togetherness of the family unit, which brings about various psychological, emotional and social benefits.

The following are some of the importance of family traditions:

1. Building Strong Family Ties

One of the importance of family traditions is that they create a chance for family members to spend quality time together hence developing closeness. These shared activities and rituals help build strong, lasting relationships among family members.

Family members learn better means of communication when they take part in traditions, offer support to each other, and feel united.

2. Identity Formation

Traditions are important in helping individuals understand their families’ history and culture. Such feelings make them feel that they belong somewhere as opposed to themselves only.

This sense of belonging is crucial for children as it helps them understand their own identity and where they come from.

3. Stability through tough times

During moments of change or anxiety, family traditions provide stability as well as continuity.

The importance of family traditions is that they offer a predictable routine that relatives can lean on during hard times; this is especially meaningful during difficult periods. Traditions are known ahead of time thus making them comforting while also relieving anxiety.

4. Teaching morals and moral principles

Family traditions often pass important values and life lessons from generation to generation. These practices usually embody the fundamental beliefs and ideas that families cherish, educating children about respect, thankfulness, responsibility, and other crucial virtues.

5. Making memories that will last

Traditions mark special occasions that become unforgettable memories. As a result of these shared experiences, a family acquires its collective history with accounts that can be handed down across generations. These recollections help cement emotional ties among family members.

6. Cultivating Group Identity

Involvement in family rituals makes one feel attached to their kin group or clan thereby creating a sense of belongingness. This bond is significant, especially for children and adolescents who experience support as well as understanding within their immediate family setting.

7. Boosting Emotional Wellbeing

Most times, familial conventions entail enjoyable activities that promote happiness and well-being. In this regard, all activities aimed at promoting fun such as holiday celebrations or an annual vacation or participating in a family game night ultimately contribute to overall emotional health by giving pleasure and relaxation too much.

8. Encouraging Family Communication

Traditions create periods for members of a family to communicate with each other on a more regular basis; either as they plan a holiday feast or merely share meals, these enable open dialogue on how to keep members connected.

9. Promoting Cultural and Religious Continuity

These are family traditions that are usually based on cultural or religious beliefs that play a role in preserving and transmitting the main elements of a family’s culture.

Involvement in such traditions helps families maintain their cultural or religious ties thus making them last for generations.

Family traditions provide the very foundation of the family unity and cohesion. They help establish and maintain meaningful connections, transmit essential values, and contribute to one’s sense of identity and belongingness.

These procedures help build up the tapestry of shared memories through which families can navigate life’s problems.

One way of strengthening family ties and creating long-lasting memories is by establishing unique family traditions. Here are some five different family traditions that shows the importance of family traditions:

1. Recipe Swap and Cook-off

For instance, every month a member of the family may pick out a recipe they would like to try. The recipes are then exchanged among individuals while others prepare their dishes.

The family can then eat together and taste all the foods as well as give each other comments about how they have cooked them. This also improves on cooking skills, adds variety to the diet, and introduces fun in the process.

2. Memory Jar

This jar should be kept somewhere everyone can see it so that small pieces of paper and pens may be available at all times in the house. For example, your family members could record happy moments, achievements, funny incidents or anything else worth remembering throughout the year and drop them into this jar.

At the end of the year or during a special occasion involving everyone in your household, empty out its contents by reading them aloud. The significance of this tradition is that it helps people look back upon positive things they have encountered and strengthens feelings of thankfulness also.

3. Sea Hunt for Each Season

Create a game of finding in every season. For example, in spring, look out for certain flowers, birds or insects; In summer go hunting for seashells, leaves of specific types or landmarks;

Alternatively, during autumn months find colourful leaves, acorns and pumpkins or locate festive decorations and footprints on the snow during winter seasons. This will help them to see that spending time outside is a way to gain knowledge and understand the world we live in.

4. Family’s Monthly Talent Show

The family should have a talent show to highlight each member’s gift once per month. Some of the things one can showcase include singing, dancing, playing an instrument such as guitar and violin, performing magic tricks and sharing one’s recent art project.

Anything that qualifies as a form of talent. It emphasizes uniqueness among the students thus increasing their level of confidence since it allows everyone to be supported by others.

5. Yearly Book Club

Selecting a book for the whole family to read over a certain period like a month or even more than that will be crucial at this point. After reading this book organize a discussion session with your family members at which they can share their thoughts about what they have read as well as some memorable parts from it.

To keep everybody engaged change the person responsible for selecting books between different relatives so that people read books from various genres and on different topics within their home library rings . Thus promoting reading culture , analyzing situations critically as well as making meaningful conversations .

These unique family traditions make life richer creating closer bonds among them through activities characterized by fun and interest which everyone eagerly anticipates

Family traditions are the threads that weave together the fabric of our shared lives, offering stability, identity, and joy. By incorporating unique traditions like a Recipe Swap and Cook-off families can cultivate a vibrant, supportive environment that nurtures growth and happiness.

At Mind Family, we believe in the profound impact that family traditions can have. They are more than just activities; they are the foundation upon which strong, loving families are built.

We encourage you to explore and create your own traditions, tailored to your family’s unique interests and values, and witness the beautiful tapestry of memories and bonds that will unfold.

What are family traditions?

Family traditions are customs and practices developed and maintained over time, often passed down through generations, to strengthen family bonds and create lasting memories.

What is the importance of family traditions?

Family traditions foster unity, create a sense of identity, provide stability, teach values, and enhance emotional well-being by offering regular opportunities for family connection and shared experiences.

What are some examples of unique family traditions?

Unique family traditions include a Recipe Swap and Cook-off, a Memory Jar, Seasonal Scavenger Hunts, Monthly Family Talent Shows, and an Annual Book Club, promoting fun and family connection.

— Share —

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Facebook

- Email this Page

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Telegram

- Share on Tumblr

- Print this Page

- Share on WhatsApp

2 responses to “Understanding The Importance Of Family Traditions And 5 Traditions You Should Embrace”

[…] kontynuacji. Przypominają nam o wspólnych chwilach, które stanowią fundament naszego życia (Mind Family) […]

[…] The smell of coffee often brings to mind cherished family traditions. Imagine waking up to the rich, inviting scent of coffee brewing in the kitchen. This daily ritual is a cornerstone in many households, marking the start of a new day. For some, it recalls mornings spent with parents or grandparents, sitting around the table, and sharing stories over a cup of freshly brewed coffee. This shared experience creates a deep bond, making the smell of coffee synonymous with family, love, and togetherness. learn more […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

10 Weird Parenting Practices Our Society Accepts as Normal

What Is Raksha Bandhan: A Deep Dive Into Its Spiritual Meaning And Significance

What is Ectopic Pregnancy: 5 Alarming Early Signs, Causes And Treatment

10 Incredible Disney Dads Who Teach Us The True Meaning of Fatherhood

Raising Children Based On Their Zodiac Sign: 12 Helpful Tips For Parents!

How To Prepare Your Child for a New Sibling: 10 Helpful Tips For Parents

The Raksha Bandhan festival is more than just a festival but a deeply felt commemoration of the unique bond between brothers and sisters. This singular day brings families closer allowing us to show love, care, and attachment through our time-honored customs.

But what’s so special about Raksha Bandhan Festival?

This piece will take us on a journey to the essence of Raksha Bandhan, penetrating into its spiritual significance and historical roots. Additionally, it will look at some of the essential practices that make this celebration truly exceptional.

Whether you are new to the festival or have celebrated it for many years, this article will enable you to have a deeper understanding of the rituals and meanings of the festival and also provide you with a guide on when is Raksha Bandhan celebrated.

When we think of Disney, we fantasize about magic realms, animals that talk, and incredible journeys. Apart from the myths and beautiful countryside, Disney has also gifted us with some truly amazing Disney fathers.

These Disney dads epitomize fatherhood and love by teaching us about love, sacrifice, and commitment.

Whether you are a parent or just looking for someone to inspire you, these Disney dads show the depth of influence that an affectionate dad can have. These fatherhood lessons from Disney movies will help you become a better parent!

Let’s dive in!

10 Incredible Disney Dads That Redefine Fatherhood and Love!

Welcoming a new child into your own family is always a historic and feeling event. However, like everything that happens, preparing your child for a new sibling is probably the hardest of them all.

This means that kids may have mixed feelings about a new sibling from being so happy to being anxious.

For this reason, at Mind Family, we understand the importance of assisting your child in making positive adjustments to life’s changes.

In this way, you can take advantage of thoughtful groundwork and proactive strategies and thus smoothen the way for preparing your child for a new sibling.

This article provides ten useful tips on how you can prepare your child to become a sibling and well as avoiding conflicts among them.

10 Video Games To Play With Your Parents And Improve Your Family Bonding

Are you searching for unique ways to bond with your parents?

Video games to play with your parents can be a great avenue of laughter, shared experiences, and friendly rivalry. Regardless of whether you are a seasoned gamer or just starting, the world of video games has something for everyone.

This article will take us through ten amazing video games to play with your parents. Each of these video games for family bonding allows parents and children to have fun together while providing an element of skill, imagination, and group effort.

So grab your controllers, and let us begin!

10 Video Games To Play With Your Parents

10 well-known movie characters based on your parenting style.

It is generally agreed that parenting is one of the most profound and rewarding experiences in life.

It’s also a trip that molds both our children and us. Each parent comes to this task in their way, shaped by what they believe in, what has happened to them before, and the type of people they are.

In this article, we will be looking at ten famous movie characters based on your parenting style.

Whether you have many jobs just like Elastigirl or teach lessons as Mufasa does you might find out that your parenting technique matches one of these cherished characters.

So let us begin!

10 Well-Know READ FULL ARTICLE ⇲ Up Next 10 Narcissistic Parents From Disney Movies That Take Toxicity To The Next Level

Disney movies are famously renowned for their magical narratives, colorful personalities, and important moral lessons. Nevertheless, behind these well-loved stories lie complex characters of narcissistic parents from Disney movies.

Of these, the depiction of narcissistic parents from Disney movies is one of the most effective narrative devices that reveal how self-centeredness and manipulation patterns can greatly affect their offspring.

In this article, we will examine numerous examples of Disney characters who personify classic signs of pathological narcissism which just take it too far.

10 Narcissistic Parents From Disney Movies

15 classic and new family movies for a perfect movie night.

Family movie nights are cherished traditions that bring everyone together, which is a perfect blend of entertainment, bonding, and relaxation.

However, it can be a challenge to find the right family movies for every age group and taste from an abundance of choices.

We have picked 15 awesome family movies whether you want to watch old classics or modern marvels that will make your movie night unforgettable.

For a perfect family movie night, here are 15 classic and new family movies.

- MPI en Español

- All Publications

- Fact Sheets

- Policy Briefs

- Commentaries

- Press Releases

- Work at MPI

- Intern at MPI

- Contact MPI

- Internships

- International Program

- Migrants, Migration, and Development

- National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy

- U.S. Immigration Policy Program

- Beyond Territorial Asylum

- Building a Regional Migration System

- Global Skills and Talent

- Latin America and Caribbean Initiative

- Migration Data Hub

- Migration Information Source

- Transatlantic Council on Migration

- ELL Information Center

Topics see all >

- Border Security

- Coronavirus

- Employment & the Economy

- Illegal Immigration & Interior Enforcement

- Immigrant Integration

- Immigrant Profiles & Demographics

- Immigration Policy & Law

- International Governance

- Migration & Development

- Refugee & Asylum Policy

Regions see all >

- Africa (sub-Saharan)

- Asia and the Pacific

- Central America & the Caribbean

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South America

- International Data

Featured Publication

Family Unity: The New Geography of Family Life

When the most intimate and enduring of human relationships are lived across international borders, states trying to manage migration flows must balance border control concerns with their international obligations to respect and support family life. While it is sometimes thought that state sovereignty over borders is complete, non-citizens can in certain cases, depending on immigration status and the nature of the relationship, claim the right to family unity in their host states.

A "right to family unity" is not expressed as such in international treaties. Rather, the term is shorthand for the sum of several interlocking rights, discussed below. In the migration context, family unity covers issues related to admission, stay, and expulsion. Family unity can also have a more specific meaning relating to constraints on state discretion to separate an existing intact family through the expulsion of one of its members. In contrast, family reunification, or reunion, refers to the efforts of family members already separated by forced or voluntary migration to regroup in a country other than their country of origin, and so implicates state discretion over admission. This article uses family unity in its broader meaning, unless the more limited one is clearly implied.

The Right to Family Unity

A family's right to live together is protected by international human rights and humanitarian law. There is universal consensus that, as the fundamental unit of society, the family is entitled to respect, protection, assistance, and support. A right to family unity is inherent in recognizing the family as a group unit. The right to marry and found a family also includes the right to maintain a family life together.

The right to a shared family life draws additional support from the prohibition against arbitrary interference with the family. Finally, states have recognized that children have a right to live with their parents. Both the father and the mother, irrespective of their marital status, have common responsibilities as parents and share the right and responsibility to participate equally in the upbringing and development of their children.

The right to family unity is not limited to citizens living in their own state. Cross-border family unity issues arise most frequently when a host state either moves to deport a non-citizen family member, or denies entry to an individual seeking to join family members already residing in the state. The corollary problem, that of a state of origin denying exit permission to an individual attempting reunification with family in another country, has become a less salient issue with the end of the Cold War.

The right to family unity across borders intersects with the prerogative of states to make decisions on the entry or stay of non-citizens. These interests seem increasingly often to clash. Today's migratory movements are fueled by the economic pressures and opportunities of globalization, the prevalence of war and other human rights violations, and the existence of kinship networks created by earlier migration. At the same time, many states have been struggling to address real and perceived migration management problems by enacting restrictive laws and increasing enforcement efforts, a trend that has intensified now that national security considerations have come to the forefront of the immigration debate.

The pressures can be enormous, both on policymakers trying to craft orderly immigration procedures, and on families who find it hard to accept that a border has come between them. The problems are widespread; forced and voluntary migrants alike grapple with these issues. Because it is so common for refugee families to be divided, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees devotes much time and attention to refugee family unity and reunification, for obvious humanitarian reasons and also because both protection and solutions are immeasurably easier for intact families. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants, Gabriela Rodriguez Pizarro, has emphasized the pervasive nature of the problem in observing that families separated by migration "are becoming increasingly common, and will become a defining characteristic of societies in many countries in the twenty-first century."

Equally defining will be the efforts of families to reunite through migration, and the ways in which states will choose to respond. The rights on which family unity is based are often qualified with provisions for the state to limit the right under certain circumstances. It should be noted, however, that the most important, and sometimes only, qualifier is the imperative to act in the best interests of the child. The nature of the family relationship shapes the right to family unity, with minor dependent children and their parents having the strongest claim to remain together or to be reunited. Maintaining the unity of an intact family poses different issues than reconstituting a separated family. Finally, the immigration status of the various family members has an impact on how the right to family unity should be implemented.

Different Kinds of Families and the Right to Unity

There is not a single, internationally accepted definition of the family, and international law recognizes a variety of forms. Some observers have noted that in many countries, traditional family patterns characterized by duties of care and concern for elders and members of the extended family are giving way to a more "western" or "nuclear" model, and caution against making outdated assumptions that favor these more distant relatives in reunification schemes. Others have pointed out that families are also evolving in more expansive ways, with the increasing acceptance of same-sex unions, and the growing phenomenon of AIDS orphans resulting in child-headed households, as just two examples. Given the variety of families, the existence of a family tie is a question of fact, best determined on a case-by-case basis.

The right to family unity applies universally to all persons. The question, then, is not whether various categories of persons have the right to family unity, but rather which state(s) must act to ensure the right. A look at the various categories of people who might claim a right to family unity demonstrates some of the issues that can arise.

Nationals : The right to marry is not limited to persons of the same nationality. However, for a citizen marrying a non-citizen, issues can arise when arbitrary restrictions are imposed or significant delays are encountered, or when female citizens have fewer rights than male citizens, for example, in obtaining entry for their non-citizen spouses or in transmitting citizenship to their children.

Migrants : Under the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, which is under consideration in the United Nations General Assembly and is soon to come into force, states shall "take measures they deem appropriate" to facilitate reunification. The degree of discretion retained by states with respect to migrant workers reflects an expectation that workers can return to their home countries if they wish to rejoin family members, although this does not take into account economic realities that keep most migrant workers firmly tied to the host country. It is far more common for migrant workers to have, or wish to have, their families join them. Although some states have been reluctant to make generous provisions for family reunification, it is increasingly understood as a positive means of promoting the integration and securing the rights of migrants in their host societies.

Refugees : Refugees recognized under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees are usually in the most advantageous position of all non-citizens with respect to family unity. Family unity in the refugee context means granting refugee or a similar secure status to family members accompanying a recognized refugee. The country of asylum must likewise provide for family reunification , at least of close family members, since the refugee cannot by definition return to the country of origin to enjoy reunification there. The right to family unity applies equally in situations of mass influx, whether managed under a temporary protection scheme or under international agreement, such as the OAU Refugee Convention. UNHCR's Executive Committee has specifically concluded that respect for family unity is a "minimum basic human standard" in such situations and has called for family reunification for persons benefiting from temporary protection. There is an emerging consensus for the need for prompt reunification during periods of temporary protection.

Others in need of international protection : Those whose claims under the 1951 Refugee Convention have been rejected after an individual determination, but who have nevertheless been found to be in need of international protection (under the Convention against Torture, for example) are entitled to respect for their fundamental human rights, including the right to family unity. The justification for refugee family reunification in a country of asylum derives from the refugee not being able to return home, and not from the Refugee Convention itself. Persons in an analogous situation of inability to return home should benefit from the same application of the right in the host country.

Asylum seekers : Since asylum seekers are, by definition, people whose legal status has not yet been determined, it may be difficult to determine where they should enjoy the right to family reunification, or which state bears responsibility for giving effect to that right. The length of proceedings in many countries causes tremendous hardship, particularly when children are apart from parents. There is a general recognition, at least in principle, that separated children should benefit from expedited procedures, but such measures do not even begin to address the right of children left in a country of origin or in transit to family reunification; no state has adopted expedited procedures for asylum-seeking parents separated from their children. States are understandably not eager to process family reunification applications for asylum seekers whose asylum applications they are having difficulty processing. Given the scarcity of state resources, however, it would be helpful to pursue possibilities for reuniting family members who are seeking asylum in various countries, particularly if determination of the claim has been pending, or is expected to take longer than, six months. The grouping together of potentially related claims, witnesses, and evidence would be more cost effective than parallel procedures in different jurisdictions, would promote more consistent decision-making, and would hasten the provision of a durable solution for the family.

Constraints on State Decisions to Expel and Admit Family Members

As a procedural matter, host states must consider the family interests involved before expelling a non-citizen family member. As a substantive matter, respect for the right to family unity requires balancing the state's interest in deporting the family member with the family's interest in remaining intact. The inquiry is focused whether the effects on the family of the separation would be disproportionate to the state's objectives in removing the individual. Considerations such as length of stay in the host country, age, and the degree of the family's financial and emotional interdependence should be weighed against the state's interests in promoting public safety and in enforcing immigration laws. The best practice suggests that, particularly when expulsion is threatened for immigration violations only, as opposed to criminal law convictions, and citizen children will be affected, states should find it difficult to rely solely on their interest in immigration enforcement to justify separating an intact family.

In assessing family unity cases involving children, states must also take into account the best interests of the child. States seeking to separate families through deportation face significant constraints in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which requires in article 9 that states " shall ensure that a child shall not be separated from his or her parents against their will, except when...such separation is necessary for the best interests of the child ." (emphasis added)

There are both procedural and substantive aspects to the best interests requirement. To ensure an adequate procedure, professional opinions regarding the impact on the child must be taken into account where deportation will mean the separation of a child from his or her parent. The substantive content of the best interests principle is not explicitly defined in the CRC. Nevertheless, certain elements emerge from other provisions of the Convention. In the case of actions and decisions affecting an individual child, it is the best interests of that individual child that must be taken into account. It is in the child's best interests to enjoy the rights and freedoms set out in the CRC, such as contact with both parents (in most circumstances). Best interests must be determined on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the totality of the circumstances. The views of the child shall be heard 'in any judicial and administrative proceedings affecting the child' and be given due weight in accordance with his or her age and maturity. It is certainly not always in the best interests of the child to remain with parents, as recognized in CRC article 9. However, it should be noted that the CRC does not recognize a public interest to be weighed against the involuntary separation of the family. The only exception allowed is when separation is necessary for the best interests of the child.

Family reunification requires a state affirmatively to allow entry to a person, as opposed to refraining from deporting someone, and thus is a right more encumbered by state discretion. Nevertheless, states are bound by international obligations toward the family in this context, as well.

These obligations are most pronounced in the CRC, but support can also be found in other human rights treaties, in humanitarian law and in refugee protection principles. In looking at the situation for minor children and their parents, several elements of the CRC are important. First, the obligation imposed to ensure the unity of families within the state also determines the state's action regarding families divided by its borders. Second, reunification may require a state to allow entry as well as departure. Third, children and parents have equal status in a mutual right; either may be entitled to join the other. Nor is it sufficient that the child be with only one parent in an otherwise previously intact family; the child has the right to be with both parents, and both parents have the right and responsibility to raise the child.

While the CRC does not expressly mandate approval of every reunification application, it clearly contemplates that there is at least a presumption in favor of approval. States cannot maintain generally restrictive laws or practices regarding the entry of aliens for reunification purposes without violating the CRC. Nor can states fail to provide and promote a procedure for reunification.

Globalization has expanded the realm in which families live and work, and created a new geography of family life. Few migrants, even those who have made the choice to travel and to do so alone, intend a permanent, or even long-term, separation from their loved ones. Immigration policymakers will increasingly be called upon to recognize the rights and realities of families living across borders.

Abram, E.F., 1995. "The Child's Right to Family Unity in International Immigration Law" 17(4) Law and Policy .

Bhabha, J., 2001. "Minors or Aliens?" Inconsistent State Intervention and Separated Child Asylum Seekers' 3 European Journal of Migration and Law .

Jastram, K. and Newland, K., 2003. "Family Unity and Refugee Protection," in E. Feller, V. Turk, and F. Nicholson (eds.) Refugee Protection in International Law: UNHCR's Global Consultations on International Protection , Cambridge University Press.

Van Krieken, P.J., 2001. "Family Reunification" in The Migration Acquis Handbook.

Family or Misery? The Question of Modernity

- Daniel de Liever

- — August 24, 2024

The cornerstone of society, the family, has seen unprecedented change since the 1950s. With the number of relatives that an individual has expected to drop by 35% in the near future, one might ask what the future of family life holds. Additionally, more and more Western adults are now child-free by choice , and alarmingly low Western birth rates are continuing to decline.

One crucial outcome has been a decline in mental health across the developed West. The decline of stable families, as one of the primary institutions of individual stability and sanity, was bound to be attended by such costs. With one in four people facing a mental illness at least once throughout their lives, and the rate of the most prominent mental health disorders—anxiety and depression—increasing by 28% and 25% respectively in 2023 alone, we can speak of a mental health crisis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the mental health crisis is “indisputable and urgent.” It is high time that we take a deeper look at the relationship between prosperous families and mentally flourishing individuals.

Dominant progressive thinkers have argued that the liberation from family life has been a deliverance to people at large, bringing opportunities, independence, and a hitherto unimaginable degree of freedom. Declining family unity is generally written off as a small price to pay or even a natural good reflective only of the emancipation of the individual. Yet the negative impact on the ground is more drastic than first meets the eye. While much of conservative thought has stressed the societal importance of a renaissance of the family as a social institution, I believe that the public debate should additionally be focused on beating modernity at its own game: in creating psychologically resilient, stable, and meaningful lives for people. Modern culture, with its progressive language of self-actualization and happiness, promotes a paradigm in which individual happiness and liberty are deemed the greatest good. But what if we could demonstrate that traditional family life brings exactly that for which modern man claims to strive, and much more besides?

The first step towards family erosion

To understand why family life changed so rapidly throughout the 20th century, we must look at the sexual revolution and its long-lasting impact. Erupting in the 1960s, this wholesale reversal of values transformed how society perceives sex, from a predominantly marital, sacred, and procreative act towards a primary act of pleasure, liberty, and individual emancipation. The result, among other things, has been an increase in divorces and a decrease in household size, marriage rates, and—perhaps most concerning of all—fertility rates (which are now below replacement levels across the vast majority of the developed world).

Underlying these sociological changes is the quest for individual emancipation. This unquestionable dogma—that unlimited liberty represents the highest virtue—is where modernism meets the reality of human nature. Unfettered freedom of choice and radical independence were promised as guarantors of overall quality of life and well-being. In practice, the shift from complementarity towards egalitarianism and from normative behavior towards the worship of the will has in fact made families more vulnerable and unstable over time which, as I will show further, has decreased the quality of life of the individual.

The solution to family erosion

A psychological account of the importance of families is crucial, but it only can be applied once we put it in its proper framework to understand human nature at the most fundamental level. We must call upon the resources of the Western tradition to make explicit an old truth that, until very recent times, was taken for granted: society can only be prosperous to the extent that its families flourish. Aristotle, Edmund Burke, Russell Kirk, and Roger Scruton, as some of the (pre)conservative giants on whose shoulders we stand, provide key insights which do not only explain the psychological agony in which we find ourselves, but also supply the tools with which we might help ourselves get back on track.

Let’s start with Aristotle, as the classical spokesman for family life. In the Politics , Aristotle describes the procreative pair of man and woman as the beginning and fundamental unit of society. This basic unit branches out into the extended family, village, and the city as a whole. The family thus holds a fundamental role as the primary multigenerational institution which enables the formation of family narratives. As Aristotle makes clear, these narratives preserve the virtues that its members need to develop according to their telos —that is, their goal or purpose. Man’s purpose, for Aristotle, is happiness, though happiness understood in a far more robust way than it usually is today. In order to strive towards our telos , Aristotle claims that we need knowledge of morality, the will to make virtuous choices, and the resolve to perform virtuous deeds, quite independently of achieving personal gain or avoiding loss. The family provides nothing less than the practice grounds, fitted with correctional mechanisms, for reaching our telos .

In modern empirical psychology, we find further support for Aristotle’s foundational outlook on families. Family narratives have been shown to give children more self-embeddedness, security, better family functioning, self-control, and self-esteem. The lack of a family narrative or the complete erasure of its existence has been shown to inflict detrimental effects on everyone concerned.

Love and culture

Burke’s work has inspired many thinkers to pursue family-oriented philosophy. One of the most important figures in this respect is Kirk. In The Conservative Mind (1957), Kirk builds upon Burke’s vision of the family as the natural center of any good society. Kirk emphasized the true antidote of modern nihilism: love. As the old Jewish saying goes, we do not give to the ones we love, but we love the ones to whom we give. And as Kirk noted, primarily in family life we learn in a stable and practical environment to give to—and thus love—the people around us. Hence, the principal instrument of moral instruction, education and economic life should remain within the family. Only then can we learn to love ourselves and others. Additionally, Kirk understood that the family creates a vital tension in which one learns through moral effort to become a functional adult, a fully formed person within the social order, through the constructive disciplining of anti-social impulses. Most of contemporary psychology therefore misplaces the lack of self-love and meaning as a technical problem to do with individuals. No wonder these ‘specialists’ seem so unable to solve the ongoing mental health crisis.

Detrimentally, modernity promises man unparalleled stability and prosperity, even while he abandons all moral efforts and throws off every possible check on personal appetite. This is not only false, but it serves to create generations which are unable to control their destructive desires for the good of their future, their surroundings, and society. This has harmed our mental welfare in two ways: first, by destabilizing families, chaos, insecurity, anxiety and reduced well-being follow; and second, guilt, nihilism, and despair enter the picture due to the inability to harness moral effort. The solution to this cultural sickness is more moral effort, instead of acceptance of moral withdrawal. Again, the family comes to the rescue with its great, ennobling demands to pursue the maximal flourishing proper to human nature.

The role of parents

Scruton lands the most fundamental conservative blow against modern society’s outlook on families as merely “procreative contracts.” In The Meaning of Conservatism (1980), he points out the most problematic thing about the rights-obsessed language of the modern age. The liberal view of society starts from a contractual relationship between individual citizens and the state. Through the conferral by autonomous individuals of a mandate to the state, liberals believe that the state can defend abstract human rights. Yet, in practice, there are no abstract rights to be found. Rights are a product of the particular social history to which we belong. Thus, far from creating society through an indefinite number of acts by individual wills, conservatives understand the dependence that we all have, as individuals, on society. It follows that society should be defended from destabilization by individual selfishness, instead of the liberal view in which the individual should be protected from society. This is crucial, for it legitimizes the conservative defense of one’s society and culture.

To bring Scruton’s vision into the realm of the family, we must look at his understanding of authority and power. According to Scruton, society exists through the alliance of authority and power. Authority and power are drawn to each other, as classically has been observed in the relationship between the church (authority) and the state (power). The establishment is defended by conservatives based on a bond that is prior to any possibility of choice or contract. The primary example of just such a bond, transcending individual will, is the family. Having been established prior to our birth, we do not choose our family. The established power of the family is a great good due to the child’s need for its parents’ power over it. This manifestation of the parents’ will over their children is strongly related to the natural love which parents feel for their children to guide them throughout their primary developmental stages. This description of love is where Scruton and Kirk coincide. The initial feeling for things outside the family is one of love and dependency, like that of the family. Just as we become adults through the established power of our parents, in society we become persons through the society’s power over us.

Relating this to the mental health crisis, the loss of authority and power of parents over their children has broken the foundation of stability and security which is crucial to the rite of passage into stable adulthood. By labeling the authority of parents over their children as an act of oppressive power instead of love, parents have gradually lost the moral claim, let alone the tools, to raise their children in a prosperous way. Instead of trying to heal broken children, modern psychology should focus on healing the family basis that gave rise to stable people in the first place.

Well-being requires family

So far, we have made the case why a strong family life is needed to create psychologically stable and prosperous individuals, as well as flourishing societies. Now, it is crucial to understand the underlying psychological mechanisms that have made the family such a powerful social institution and increased individual well-being. This unites the philosophical and psychological underpinning of the family and indicates how modern psychology might contribute to family policy.

An important psychological theory to understand family life is stress process theory, which tells us that stress can undermine mental health. Additionally, receiving family support increases a sense of self-worth, self-esteem, optimism, positive affect, and overall good mental health. In short, family relations reduce stress and therefore can improve the individual’s mental health. Moreover, family relationships also play a role in regulating other’s behavior and providing information and encouragement to behave in healthier ways, in accordance with the vision of the family, promoted by Aristotle and Scruton, as the primary institution to develop prosperous people. Finally, the quality of family relations is important to highlight. Positive family relations are associated with a lower allostatic load (wear and tear on the body accumulating from stress), whereas negative family relations are associated with a higher allostatic load. When relating this to modern society, the increased instability and erosion of family relations reduces the potential for positive family relations to form and therefore reduces individual well-being, in line with Burke’s warning that only strong families are able to bring forth flourishing people.

Overall, the family forms one of the most important cornerstones of human flourishing. It makes us psychologically able to develop through intergenerational narratives, moral effort, and love. Families are thus entitled to power and authority in society, so that parents are able to nourish their children for the common good. This gives new generations the freedom to develop in accordance with their own adventures. Perhaps counterintuitively for today’s sensibilities, the conservative outlook, with its cardinal emphasis on family, nevertheless fulfills the modern dream of happiness and mental flourishing. A tremendous amount of social capital is lost with the modern shift towards radical individualization. It has reduced the cooperative strength of human beings into fractures and vulnerabilities. Modern man, as he becomes increasingly psychologically fragile, needs to rediscover that most basic of great assets to deal with an increasingly complex and changing world: an embedded family.

- Tags: Daniel de Liever , family

The Seductiveness of Ideology in Politics

An Uncertain Future for Conservative Christians: An Interview with Rod Dreher

Norman Stone (1941-2019)

SUBSCRIPTION

Privacy policy.

To submit a pitch for consideration: submissions@ europeanconservative.com

For subscription inquiries: subscriptions@ europeanconservative.com

© The European Conservative 2023

- Privacy Policy

- General Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Made by DIGITALHERO

Summer 2024, issue 31, jobs & vacancies.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Family, culture, and communication.

- V. Santiago Arias V. Santiago Arias College of Media and Communication, Texas Tech University

- and Narissra Maria Punyanunt-Carter Narissra Maria Punyanunt-Carter College of Media and Communication, Texas Tech University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.504

- Published online: 22 August 2017

Through the years, the concept of family has been studied by family therapists, psychology scholars, and sociologists with a diverse theoretical framework, such as family communication patterns (FCP) theory, dyadic power theory, conflict, and family systems theory. Among these theories, there are two main commonalities throughout its findings: the interparental relationship is the core interaction in the familial system because the quality of their communication or coparenting significantly affects the enactment of the caregiver role while managing conflicts, which are not the exception in the familial setting. Coparenting is understood in its broader sense to avoid an extensive discussion of all type of families in our society. Second, while including the main goal of parenting, which is the socialization of values, this process intrinsically suggests cultural assimilation as the main cultural approach rather than intergroup theory, because intercultural marriages need to decide which values are considered the best to be socialized. In order to do so, examples from the Thai culture and Hispanic and Latino cultures served to show cultural assimilation as an important mediator of coparenting communication patterns, which subsequently affect other subsystems that influence individuals’ identity and self-esteem development in the long run. Finally, future directions suggest that the need for incorporating a nonhegemonic one-way definition of cultural assimilation allows immigration status to be brought into the discussion of family communication issues in the context of one of the most diverse countries in the world.

- parental communication

- dyadic power

- family communication systems

- cultural assimilation

Introduction

Family is the fundamental structure of every society because, among other functions, this social institution provides individuals, from birth until adulthood, membership and sense of belonging, economic support, nurturance, education, and socialization (Canary & Canary, 2013 ). As a consequence, the strut of its social role consists of operating as a system in a manner that would benefit all members of a family while achieving what is considered best, where decisions tend to be coherent, at least according to the norms and roles assumed by family members within the system (Galvin, Bylund, & Brommel, 2004 ). Notwithstanding, the concept of family can be interpreted differently by individual perceptions to an array of cultural backgrounds, and cultures vary in their values, behaviors, and ideas.

The difficulty of conceptualizing this social institution suggests that family is a culture-bound phenomenon (Bales & Parsons, 2014 ). In essence, culture represents how people view themselves as part of a unique social collective and the ensuing communication interactions (Olaniran & Roach, 1994 ); subsequently, culture provides norms for behavior having a tremendous impact on those family members’ roles and power dynamics mirrored in its communication interactions (Johnson, Radesky, & Zuckerman, 2013 ). Thus, culture serves as one of the main macroframeworks for individuals to interpret and enact those prescriptions, such as inheritance; descent rules (e.g., bilateral, as in the United States, or patrilineal); marriage customs, such as ideal monogamy and divorce; and beliefs about sexuality, gender, and patterns of household formation, such as structure of authority and power (Weisner, 2014 ). For these reasons, “every family is both a unique microcosm and a product of a larger cultural context” (Johnson et al., 2013 , p. 632), and the analysis of family communication must include culture in order to elucidate effective communication strategies to solve familial conflicts.

In addition, to analyze familial communication patterns, it is important to address the most influential interaction with regard to power dynamics that determine the overall quality of family functioning. In this sense, within the range of family theories, parenting function is the core relationship in terms of power dynamics. Parenting refers to all efforts and decisions made by parents individually to guide their children’s behavior. This is a pivotal function, but the quality of communication among people who perform parenting is fundamental because their internal communication patterns will either support or undermine each caregiver’s parenting attempts, individually having a substantial influence on all members’ psychological and physical well-being (Schrodt & Shimkowski, 2013 ). Subsequently, parenting goes along with communication because to execute all parenting efforts, there must be a mutual agreement among at least two individuals to conjointly take care of the child’s fostering (Van Egeren & Hawkins, 2004 ). Consequently, coparenting serves as a crucial predictor of the overall family atmosphere and interactions, and it deserves special attention while analyzing family communication issues.

Through the years, family has been studied by family therapists, psychology scholars, and sociologists, but interaction behaviors define the interpersonal relationship, roles, and power within the family as a system (Rogers, 2006 ). Consequently, family scholarship relies on a wide range of theories developed within the communication field and in areas of the social sciences (Galvin, Braithwaite, & Bylund, 2015 ) because analysis of communication patterns in the familial context offers more ecological validity that individuals’ self-report measures. As many types of interactions may happen within a family, there are many relevant venues (i.e., theories) for scholarly analysis on this subject, which will be discussed later in this article in the “ Family: Theoretical Perspectives ” section. To avoid the risk of cultural relativeness while defining family, this article characterizes family as “a long-term group of two or more people related through biological, legal, or equivalent ties and who enact those ties through ongoing interactions providing instrumental and/or emotional support” (Canary & Canary, 2013 , p. 5).

Therefore, the purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the most relevant theories in family communication to identify frustrations and limitations with internal communication. Second, as a case in point, the United States welcomes more than 50 million noncitizens as temporary visitors and admits approximately 1 million immigrants to live as lawful residents yearly (Fullerton, 2014 ), this demographic pattern means that nearly one-third of the population (102 million) comes from different cultural backgrounds, and therefore, the present review will incorporate culture as an important mediator for coparenting, so that future research can be performed to find specific techniques and training practices that are more suitable for cross-cultural contexts.

Family: Theoretical Perspectives

Even though the concept of family can be interpreted individually and differently in different cultures, there are also some commonalities, along with communication processes, specific roles within families, and acceptable habits of interactions with specific family members disregarding cultural differences. This section will provide a brief overview of the conceptualization of family through the family communication patterns (FCP) theory, dyadic power theory, conflict, and family systems theory, with a special focus on the interparental relationship.

Family Communication Patterns Theory

One of the most relevant approaches to address the myriad of communication issues within families is the family communication patterns (FCP) theory. Originally developed by McLeod and Chaffee ( 1973 ), this theory aims to understand families’ tendencies to create stable and predictable communication patterns in terms of both relational cognition and interpersonal behavior (Braithwaite & Baxter, 2005 ). Specifically, this theory focuses on the unique and amalgamated associations derived from interparental communication and its impact on parenting quality to determine FCPs and the remaining interactions (Young & Schrodt, 2016 ).

To illustrate FCP’s focus on parental communication, Schrodt, Witt, and Shimkowski ( 2014 ) conducted a meta-analysis of 74 studies (N = 14,255) to examine the associations between the demand/withdraw family communication patterns of interaction, and the subsequent individual, relational, and communicative outcomes. The cumulative evidence suggests that wife demand/husband withdraw and husband demand/wife withdraw show similar moderate correlations with communicative and psychological well-being outcomes, and even higher when both patterns are taken together (at the relational level). This is important because one of the main tenets of FCP is that familial relationships are drawn on the pursuit of coorientation among members. Coorientation refers to the cognitive process of two or more individuals focusing on and assessing the same object in the same material and social context, which leads to a number of cognitions as the number of people involved, which results in different levels of agreement, accuracy, and congruence (for a review, see Fitzpatrick & Koerner, 2005 ); for example, in dyads that are aware of their shared focus, two different cognitions of the same issue will result.