Indian Criminal Justice System Reforms Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

History of criminal justice system, modern india criminal justice system.

Bibliography

Throughout world history, numerous criminal injustices have been witnessed. In most parts of the world, security officials have been blamed for perpetuating injustices against human rights. However, India is prone to criminal activities due to the harsh economic times. As a result, the security system always faces the challenge of implementing the law and respecting human rights.

In as much as some human rights activists often complain of the violation of the rights by the justice system, India’s criminal system has faced significant changes since colonial times to the present. The Indian criminal justice field reforms were closely associated with social changes that shifted the focus from archaic rituals to more modern regulatory principles, with the introduction of an updated criminal justice system with juries and credible representatives; the law was the significant advancements.

Religious Governance

Initially, the natives relied on religious laws to govern themselves. For instance, Muslims were punished according to the Islamic laws while Hindus were punished according to their customs. Nevertheless, Ahmad illustrates that Muslim rules prevailed over other religious practices because it was the most popular religion. However, criminal justice was modified by the regulations and customs of the Mughal administration.

British Colonial

Queen Elizabeth granted a royal charter to the English East India Company to enact laws in their territory; however, the rules were not supposed to contradict England’s. The subsequent charters of 1609 and 1661 empowered the company and allowed it to make its laws without England’s interference.

The 1726 charter empowered the councils and governors to make by-laws that could control the activities taking place within their territory. The laws also allowed them to instill penalties and pain to those who disobeyed the regulations imposed. However, the pain and punishment would be reasonable and conform to the laws that governed England. The charter also introduced the mayor’s court in several towns within India.

The criminal laws that were initially derived from the Muslim values started to lose weight when the British regulations began to take effect.

Panchayat System

After the degradation of the traditional Muslim laws, Wilk attempted to revive the panchayat system of trial. He encouraged the rulers in India to equip themselves with Hindoo Panchayet to help govern India effectively. Wilk acknowledged that India needed leaders who were well conversant with the traditions and methods of conflict resolution since the regulations imposed by the colonial masters were receiving a lot of resistance, and in some cases, it failed to work. He wanted to revive the ancient Indian institutions because he was inspired by Malcolm, an advocate of the panchayat system. Malcolm believed in two aspects of panchayat:

- The serving of justice through investigations conducted by tribunals and the results transmitted for a chief ruler for justice dispensation.

- Formation of independent tribunals to mediate and arbitrate.

Sir Thomas Munro also advocated for common law in India, and Punchayet was recommended as the applicable law of governance. The plan was adopted in 1814 after the courts experienced a backlog of cases.

The East India Judges Act

The act harmonized the salaries and pensions of juries across India. It promoted an inquiry into juries’ role and function across India, resulting in Jury bill introduction. The Juries Act allowed only Christians to form part of the jury as locals were viewed as biased individuals.

The legal system can be traced back to the Roman empire, where people were required to act according to the law. In ancient Rome, the courts interpreted the rules and punished the offenders who were brought to them using legal means. The legal idea conceived in Rome has been used by several generations and currently influences the justice system across the globe.

After the gain of independence in 1947, the power was vested to Indians. However, the country was again faced with the issues of criminal injustices. Access to fair justice has been difficult for several decades, even though the constitution provides a framework for protecting citizens’ rights.

The Planning Commission of India has established a working group to help the justice department create a 12th five-year plan. The recommendations suggested by the working group include:

- strengthening of Alternate Dispute Resolution system;

- increased funding to the judicial system;

- establishing morning and evening special courts;

- enhancing ICT to develop an innovative e-Court system.

The constitution has strengthened the laws that affect establishing an independent judicial system and an active civil society. The establishment of The National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) in 1987 has enabled many poor Indians to access free legal services. The Department of Justice has collaborated with United Nations Development Program to ensure that the justice system is sustainable and able to adhere to the principles of equality, liberty, and fraternity.

However, the judicial system has worsened over the years despite the numerous actions to provide quality service. The poor delivery of services is caused by enormous backlogs, delays, and judicial pendency. According to Mudgal, the political class prefers a judiciary to easily manipulate to champion their interests because most of them face criminal charges. As a result, the police reforms have not been implemented, and numerous supreme court rulings have been violated.

The prisons across India are currently overcrowded due to the numerous criminals that are jailed. The judicial systems are also overwhelmed, and police brutality shows that the legal aid’s right stipulated in the constitution is far from being achieved.

Succinctly, the criminal justice system has changed significantly over the past decades. The government has formed a partnership with international bodies to ensure that the country meets the modern democratic countries’ justice system’s standards. Although several reforms have been made, numerous challenges are affecting the full implementation of the system. For instance, the political class has systematically weakened the judiciary, and at times the court rulings are not obeyed.

Ahmad, Sk Ehtesham Uddin. “Colonial Reshaping of Criminal Law Before the Code of 1860.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 73 (2012): 553-62.

Ganguly, Chawm. 2012. “ Dr. Ashwani Kumar Inaugurates International Conference on Equitable Access to Justice: Legal Aid and Legal Empowerment. ” Core Sector Communique . Web.

Jaffe, James A. “Custom, Identity, and the Jury in India, 1800-1832.” The Historical Journal 57, 1 (2014): 131-55.

May, Larry. Ancient Legal Thought: Equity, Justice, and Humaneness from Hammurabi and the Pharaohs to Justinian and the Talmud. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Mudgal, Vipul. 2019. “ Reforming India’s Broken Criminal Justice System. ” The Hindustan Times . Web.

Shahidullah, Shahid M. Crime, Criminal Justice, and the Evolving Science of Criminology in South Asia . London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017.

United Nations Centre Against Apartheid. Special Committee on Apartheid Hears Judge William H. Booth : New York: Department of Political and Security Council Affairs, 1971.

- Classification of Burglary Criminal

- Pleading Guilty: Key Motivation

- One-Way MANOVA Data Analysis

- Military Trials: The Criminal Justice Procedures Violations

- The Relationship Between Physical Health and Life Satisfaction

- Discussion of Social Control of Perpetrators

- Analysis of Mary Winkler Case Study

- The Felony Murder Rule: When Is It Unfair?

- Hate Crimes and Implications

- Drug Cartels Problem Overview

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, November 3). Indian Criminal Justice System Reforms. https://ivypanda.com/essays/indian-criminal-justice-system-reforms/

"Indian Criminal Justice System Reforms." IvyPanda , 3 Nov. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/indian-criminal-justice-system-reforms/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Indian Criminal Justice System Reforms'. 3 November.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Indian Criminal Justice System Reforms." November 3, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/indian-criminal-justice-system-reforms/.

1. IvyPanda . "Indian Criminal Justice System Reforms." November 3, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/indian-criminal-justice-system-reforms/.

IvyPanda . "Indian Criminal Justice System Reforms." November 3, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/indian-criminal-justice-system-reforms/.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

Criminal Justice System of India – Is it time to implement the Malimath Committee Report?

Last updated on December 24, 2023 by ClearIAS Team

This results in a big problem of people losing faith in the Criminal Justice System of India – which is very dangerous.

The Government of India has been considering revisiting the Malimath Committee Report on reforms (2003) in the Criminal Justice System of India. In this context, ClearIAS in this article, analyse the country’s Criminal Justice System, the Malimath Committee recommendations and the need for reforming the system.

Table of Contents

What is the Criminal Justice System (CJS)?

- The Criminal Justice System (CJS) includes the institutions/agencies and processes established by a government to control crime in the country. This includes components like police and courts.

- The aim of the Criminal Justice System (CJS) is to protect the rights and personal liberty of individuals and the society against its invasion by others.

- The Criminal law in India is contained in a number of sources – The Indian Penal Code of 1860, the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 and the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act , 1989.

- CJS can impose penalties on those who violate the established laws.

- The criminal law and criminal procedure are in the concurrent list of the seventh schedule of the constitution.

Background of the Criminal Justice System in India

- The Criminal Justice System in India is an age-old system primarily based upon the Penal legal system that was established by the British Rule in India.

- The system has still not undergone any substantial changes even after 70 years of Independence. The biggest example could be Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) that defines sedition and provides for its punishment.

- The entire Code of Criminal Procedure (Cr.P.C.) was amended in 1973.

- The appointment of the Vohra Committee was the very first attempt towards reforming the Criminal Justice System in India. Vohra Committee report (1993) made an observation on the criminalisation of politics and of the nexus among criminals, politicians and bureaucrats in India.

- In 2000, the government formed a panel headed by Justice V.S. Malimath, the former Chief Justice of Kerala and Karnataka, to suggest reform in the century-old criminal justice system.

- The Malimath Committee submitted its report in 2003 with 158 recommendations but these were never implemented.

- The Committee felt that the existing system “weighed in favour of the accused and did not adequately focus on justice to the victims of crime.”

Why there is a need for reform in the Criminal Justice System in India?

[click_to_tweet tweet=”In India only about 16 percent of people booked for criminal offences are finally convicted. Low rate of conviction points to the inefficiency of the Criminal Justice System of India – which includes the police, prosecutors, and the judiciary.” quote=”In India only about 16 percent of people booked for criminal offences are finally convicted. Low rate of conviction points to the inefficiency of the Criminal Justice System of India – which includes the police, prosecutors, and the judiciary.”]

- The system has become ineffective: The state has constituted the CJS to protect the rights of the innocent and punish the guilty but the system, based on century-old outdated laws, has led to harassment of people by the government agencies and also put pressure on the judiciary.

- Inefficiency in justice delivery: The system takes years to bring justice and has ceased to deter criminals. There is a lack of synergy among the judiciary, the prosecution and the police. A large number of guilty go unpunished in a large number of cases. On the contrary, many innocent people remain as undertrail prisoners as well. As per NCRB data , 67.2% of our total prison population comprises of undertrials prisoners.

- Complex nature of the crime: Crime has increased rapidly and the nature of crimes are becoming more and more complex due to technological innovations.

- Investigation incapability: It led to delay in or haphazard investigation of crimes which greatly contribute to the delay in dispensing prompt justice.

- Inequality in the justice: The rich and the powerful hardly get convicted, even in cases of serious crimes. Also, the growing nexus between crime and politics has added a new dimension to the crime scenario.

- The lowered confidence of common man: The judicial procedures have become complicated and expensive. There is a rise in cases of mob violence.

Recommendation of the Malimath Committee

Some of the important recommendations of the committee were:

- Courts and Judges: There is a need for more judges in the country.

- National Judicial Commission: The Constitution of a National Judicial Commission to deal with the appointment of judges to the higher courts and amending Article 124 to make impeachment of judges less difficult.

- Separate criminal division in higher courts: The higher courts should have a separate criminal division consisting of judges who have specialised in criminal law.

- The inquisitorial system of investigation: The Inquisitorial system is practised in countries such as Germany and France should be followed.

- Power for court to summon any person: Court’s power to summon any person, whether or not listed as a witness if it felt necessary.

- Right to silence: A modification to Article 20 (3) of the Constitution that protects the accused from being compelled to be a witness against himself/herself. The court should be given freedom to question the accused to elicit information and draw an adverse inference against the accused in case the latter refuses to answer.

- The right of accused: A schedule to the Code be brought out in all regional languages to make accused aware of his/her rights, as well as how to enforce them.

- Presumption of Innocence: The courts follow “proof beyond reasonable doubt” as the basis to convict an accused in criminal cases which is an unreasonable burden on the prosecution and hence a fact should be considered as proven “if the court is convinced that it is true” after evaluating the matters before it.

- Justice to the victims: The victim should be allowed to participate in cases involving serious crimes and also be given adequate compensation. If the victim is dead, the legal representative shall have the right to implead himself or herself as a party, in case of serious offences. The State should provide an advocate of victim’s choice to plead on his/her behalf and the cost has to be borne by the state if the victim can’t afford it.

- Victim Compensation Fund: A Victim Compensation Fund can be created under the victim compensation law and the assets confiscated from organised crimes can be made part of the fund.

- Police Investigation: Hiving off the investigation wing of Law and Order

- National Security Commission and State Security Commissions: Setting up of a National Security Commission and State Security Commissions.

- SP in each district: Appointment of an SP in each district to maintain crime data, an organisation of specialised squads to deal with organised crime.

- Director of Prosecution: A new post, Director of Prosecution, should be created in every state to facilitate effective coordination between the investigating and prosecuting officers.

- Witness protection: The dying declarations, confessions, and audio/video recorded statements of witnesses should be authorised by law. There should be a strong witness protection mechanism . Witnesses should be treated with dignity.

- Arrears Eradication Scheme: To settle those cases which are pending for more than two years through Lok Adalat on a priority basis.

- Offences classification: It should be changed to the social welfare code, correctional code, criminal code, and economic and other offences code instead of the current classification of cognisable and non-cognisable.

- Substitution of death sentence: Substitute with imprisonment for life without commutation or remission.

- Central law for organized crime and terrorism: Though crime is a state subject, a central law must be enacted to deal with organised crime, federal crimes, and terrorism.

- Periodic review: A Presidential Commission was recommended for a periodical review of the functioning of the Criminal Justice System.

Key issues in the recommendations

- Malimath Committee report recommends making confessions made to a senior police officer (SP rank or above) admissible as evidence. Confessions to police have repeatedly come under scrutiny because of allegations of custodial torture, instances of custodial deaths, fake encounters and tampering with evidence .

- The report recommends diluting the standard of proof lower than the current ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ standard. It means that if a proof is enough to convince the court that something is true, then it can be considered as a standard proof. Such a measure would have adverse implications on suspects and requires considerable deliberation.

Reforms undertaken by the Government

- The government has implemented a number of recommendations like permitting videography of statements, the definition of rape has been expanded and new offences against women have been added. The victim compensation is now a part of the law.

- The Government is in the process to draft a new Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) for the appointment of High Court and Supreme Court Judges.

- The government has removed more than 1000 obsolete laws which came in the way of smooth administration.

- The Government has given its approval for implementation of an umbrella scheme of ‘Modernisation of Police Forces’ with proper use of technology.

- The Gram Nyayalayas and Lok Adalats were established to provide access to justice to the citizens at their doorsteps.

- The Legal Service Authority Act was enacted by the Parliament with an object to provide free and competent legal service to the weaker section of society.

Way Forward

UPSC CSE 2025: Study Plan ⇓

(1) ⇒ UPSC 2025: Prelims cum Mains

(2) ⇒ UPSC 2025: Prelims Test Series

(3) ⇒ UPSC 2025: CSAT

Note: To know more about ClearIAS Courses (Online/Offline) and the most effective study plan, you can call ClearIAS Mentors at +91-9605741000, +91-9656621000, or +91-9656731000.

It is a good idea to revisit the committee recommendations with a view to considering their possible implementation. However, the reforms should be made with care and after proper debate. The provisions like diluting the standard of proof or considering confession to senior police as evidence must be properly debated.

Supreme Court had already set guidelines for how the prosecution and the police should function to get justice to the victims and punish the guilty.

Revamping the CJS should not undermine the principles on which the justice system was founded. The rules and procedures are needed to be simplified to make it convenient for the common man. The primary focus must be on police reforms , appointing more judges, deploying scientific techniques, beefing up forensic labs, and other infrastructure investments are the need of the hour.

Read: Revised Criminal Laws

Article by: Alok Kumar

Top 10 Best-Selling ClearIAS Courses

Upsc prelims cum mains (pcm) gs course: unbeatable batch 2025 (online), rs.75000 rs.29000, upsc prelims marks booster + 2025 (online), rs.19999 rs.14999, upsc prelims test series (pts) 2025 (online), rs.9999 rs.4999, csat course 2025 (online), current affairs course 2025 (online), ncert foundation course (online), essay writing course for upsc cse (online), ethics course for upsc cse (online), upsc interview marks booster course (online), rs.9999 rs.4999.

About ClearIAS Team

ClearIAS is one of the most trusted learning platforms in India for UPSC preparation. Around 1 million aspirants learn from the ClearIAS every month.

Our courses and training methods are different from traditional coaching. We give special emphasis on smart work and personal mentorship. Many UPSC toppers thank ClearIAS for our role in their success.

Download the ClearIAS mobile apps now to supplement your self-study efforts with ClearIAS smart-study training.

Reader Interactions

October 13, 2018 at 12:35 am

Very illustrative and informative article. Thanks, ClearIas.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don’t lose out without playing the right game!

Follow the ClearIAS Prelims cum Mains (PCM) Integrated Approach.

Join ClearIAS PCM Course Now

UPSC Online Preparation

- Union Public Service Commission (UPSC)

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

- Indian Police Service (IPS)

- IAS Exam Eligibility

- UPSC Free Study Materials

- UPSC Exam Guidance

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Prelims

- UPSC Interview

- UPSC Toppers

- UPSC Previous Year Qns

- UPSC Age Calculator

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- About ClearIAS

- ClearIAS Programs

- ClearIAS Fee Structure

- IAS Coaching

- UPSC Coaching

- UPSC Online Coaching

- ClearIAS Blog

- Important Updates

- Announcements

- Book Review

- ClearIAS App

- Work with us

- Advertise with us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Talk to Your Mentor

Featured on

and many more...

ClearIAS Programs: Admissions Open

Thank You 🙌

UPSC CSE 2025: Study Plan

Subscribe ClearIAS YouTube Channel

Get free study materials. Don’t miss ClearIAS updates.

Subscribe Now

IAS/IPS/IFS Online Coaching: Target CSE 2025

Cover the entire syllabus of UPSC CSE Prelims and Mains systematically.

- About India Foundation

- Board of Trustees

- Governing Council

- Distinguished Fellows

- Deputy Directors

- Senior Research Fellows

- Research Fellows

- Visiting Fellows

- Publications

- India Foundation Journal

- Issue Briefs

- Annual Report

- Upcoming Events

- Event Reports

- Press Release

- LD linkedin [#161] Created with Sketch.

India’s Criminal Justice Overhaul: A Deep Dive into the New Laws

The three new criminal laws came into effect on July 1, 2024, ushering significant changes to the country’s criminal justice system and ending colonial-era legislation. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, and the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam have replaced the British-era Indian Penal Code of 1860, Code of Criminal Procedure of 1973, and Indian Evidence Act of 1872, respectively.

The law ministry has announced that any reference to the now-replaced Indian Penal Code (IPC), Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), and Evidence Act in any statute, ordinance, or regulation would be interpreted as a reference to the new criminal justice laws. These old laws were replaced by the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) on July 1. The legislative department of the law ministry has issued a notification under the General Clauses Act to this effect. An official clarified that the notification reaffirms the provisions of the General Clauses Act, which addresses the repeal and re-enactment of laws.

The enforcement of the laws has evoked mixed responses from different quarters and stakeholders. A few PILs were filed in the Apex Court to derail or delay the implementation of the laws that seek to modernise the criminal justice system and make justice more accessible for ordinary citizens. Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud has openly advocated fast-tracking of trials from every conceivable platform and has aggressively worked to introduce technology in the judicial process to deliver faster justice and reinforce the faith of the people in the judiciary. The Supreme Court refused to entertain any of these PILs.

There was a litany of newspaper articles and social media onslaught about the new criminal laws, accusing the Central Government of rushing the job without adequate discussion and consensus among the stakeholders. Some naysayers among the critical stakeholders in the criminal justice system, particularly retired police officers, lawyers, academia, and a few non-profits, sought to castigate the government initiative on one or the other pretext. However, they all failed to muster public opinion against the new laws.

On August 15, 2022, while addressing the nation from the ramparts of the Red Fort on India’s 76th Independence Day, Prime Minister Narendra Modi talked about the ‘Panch Praan’ for the coming 25 years (Amrit Kaal) . Elaborating on the second Praan, he said, “In no part of our existence, not even in the deepest corners of our mind or habits, should there be any ounce of slavery. It should be nipped there itself. We have to liberate ourselves from the slavery mindset, which is visible in innumerable things within and around us. This is our second Praan Shakti.” He also said, “In this Azadi Ka Amrit Kaal, new laws should be made by abolishing the laws which have been going on from the time of slavery.” [1]

All the ministries were asked to identify obsolete provisions from the colonial era and draft new legislation that fulfilled the aspirations of a resurgent India. The Central Government has repealed over 1,500 archaic laws in the last decade. These three criminal laws are the result of such an endeavour.

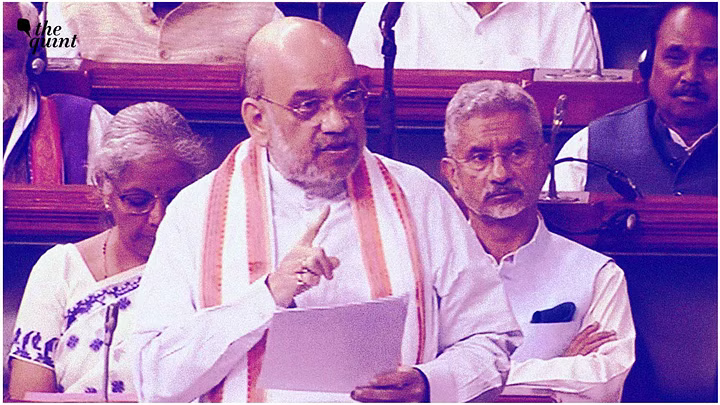

The new laws address contemporary social realities and crimes while aligning with the ideals enshrined in the Constitution. Union Home Minister Amit Shah, who introduced the laws, stated that the new legislation prioritises justice over penal action provisioned in the colonial laws. “These laws are made by Indians, for Indians, and by an Indian Parliament, marking the end of colonial criminal justice laws,” Shah said. The “soul, body, and spirit” of the new laws are distinctly Indian, he added. [2] Shah explained that justice encompasses both the victim and the accused, and the new laws aim to ensure political, economic, and social justice with an Indian ethos.

Decolonisation rhetoric aside, there is consensus that the three new laws address the contemporary requirements of defining crimes, processes, and indictments, relying on the principles of justice as opposed to the retribution of the old laws. Justice would be delivered “up to the level of the Supreme Court” within three years of registering an FIR.

The Positives

The new laws positively impact the criminal justice system because wide-ranging consultations were held with legislators, judicial and legal pundits, police and corrections leadership, academia, NGOs and other stakeholders. According to the Union Home Minister, these laws were discussed in the Lok Sabha for 9 hours and 29 minutes and in the Rajya Sabha for 6 hours and 17 minutes. Suggestions were sought from all MPs, Chief Ministers, Supreme Court and High Court Judges, IPS officers and Collectors in 2020. The Minister attended 158 consultative meetings to prepare these Bills. The bills were later sent to the Home Ministry committee, which has representatives from all major political opposition parties. The Committee discussed the Bill for about three months. Most of the suggestions for reforms in criminal laws were incorporated, except four, which the Central Government found were political. This consultative process convincingly debunks the allegations of lack of discussion and hasty passage of the bills.

The new laws make critical changes at four levels of the whole criminal justice procedure:

- At the substantive crimes/offences level under BNS.

- At the Police investigation level.

- At the judicial magistrate level, and finally,

- At the Trial level.

The BNS is much shorter than the IPC. Redundant sections have either been pruned, merged or simplified, reducing the number of sections from 511 in the Indian Penal Code to 358. For example, definitions previously scattered across sections 6 to 52 are now consolidated into one section. Eighteen sections have been repealed, and four relating to weights and measures are now covered under the Legal Metrology Act of 2009. Some still criticise the new acts as colonial for retaining nearly 75% of the old sections.

New provisions address issues like false promises of marriage, gang rape of minors, mob lynching, and chain snatching, which the old Indian Penal Code did not adequately cover. A new provision addresses the abandonment of women after making sexual relations under a false promise of marriage.

Snatching, defined in Clause 304(1), is one of the ‘new’ crimes, distinct from theft. The definition reads: “In order to commit theft, the offender suddenly or quickly or forcibly seizes or secures or grabs or takes away from any person or from his possession any moveable property”. Both theft and snatching prescribe a punishment of up to three years in jail.

All state governments are now mandated to implement witness protection schemes to ensure the safety and cooperation of witnesses, enhancing the credibility and effectiveness of legal proceedings. The definition of “gender” now includes transgender individuals, promoting inclusivity and equality.

Another notable addition to the BNS is the inclusion of offences such as organised crime and terror, previously in the ambit of specific stringent laws like the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act for terrorism and state-specific laws such as the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act for organised crime. On terrorism, the BNS borrows heavily from the UAPA.

Organised crime, in Clause 111(1), encompasses “any continuing unlawful activity including kidnapping, robbery, vehicle theft, extortion, land grabbing, contract killing, economic offences, cyber-crimes having severe consequences, trafficking in people, drugs, illicit goods or services and weapons, human trafficking racket for prostitution or ransom. Sedition, which raised the freedom heckles from the civil society, has been replaced with treason. Some detractors of the retention of treason in the new code believe it to be a colonial hangover. The Supreme Court in May 2022 virtually stalled the operation of sedition law, deeming it “prima facie unconstitutional.” The Government claims the new laws have “done away with sedition.”

The BNS has, however, introduced the offence with a broader definition while incorporating the Supreme Court guidelines in the 1962 Kedarnath Singh case, which upheld the constitutional validity of the crime of sedition. In Hindi, the law carries out a simple name change—from rajdroh (rebellion against the king) to deshdroh (rebellion against the nation). The Central Government must be aware of the internal security challenges, extraneous factors, and different state and non-state actors fomenting fissiparous tendencies in our country. The jury is out to assess the Government’s assurance about the judicious use of the new treason provisions.

The BNS has also consolidated previously scattered provisions about crimes against women and children in one chapter (Chapter V). New provisions have been added to strengthen women’s rights. Section 69 BNS, for example, introduces a new offence not previously included in the IPC that penalises a man who engages in consensual sexual intercourse with a woman under four categories of deceit, including a false promise to marry.

In line with the Apex Court’s decriminalisation of adultery in the landmark Joseph Shine judgment, t he BNS has removed adultery from the criminal code.

Several crimes and their perpetrators have been made gender-neutral. For instance, Section 77 BNS (previously Section 354C IPC), which addresses voyeurism, is now gender-neutral concerning the perpetrator—the term ‘whoever’ replaces ‘any man’ from the IPC. Similarly, Section 76 BNS (previously Section 354B IPC), which addresses assault with intent to disrobe a woman, now uses ‘whoever’ instead of ‘any man,’ allowing for the prosecution of women perpetrators. Additionally, the BNS has enhanced punishment terms for many offences protecting women.

One of the glaring omissions from the new laws is the issue of marital rape. The status of marital rape, as an exception to the offence of rape in the IPC, is still retained in the new BNS, despite several court rulings recognising marital rape as a ground for divorce. The issue is sub judice in the Apex Court. Section 67 BNS still requires the victim of a forceful sexual assault by a separated husband to report the matter herself and not by any friend or family member. The BNS keeps such a horrible offence as a bailable offence.

The BNS, with a seemingly progressive outlook, entirely leaves out Section 377 of the IPC, which criminalised “carnal intercourse against the order of nature”. In 2018, the Apex Court read this provision down in its landmark Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India verdict, holding that it decriminalised consensual sex among adults, including those of the same sex. [3] The judgment created an exception in the case of consensual sex among same-sex individuals. However, with the exclusion of the entire Section 377 of the IPC provision in the BNS, and with rape laws still not made gender-neutral, there is little criminal recourse for male victims of such sexual assault, transgender people and the crimes of bestiality.

The BNS, under Section 103, for the first time, recognises murder on the grounds of race, caste, or community as a separate offence. The Supreme Court had, in 2018, directed the Centre to consider a separate law for lynching. The new provision should arrest the incidence of such crimes, which has shown an upward trend in recent years. The inclusion of offences for mob lynching is crucial and signals a legislative intent to curb such hate crimes.

These new laws aim to make the police investigation people-friendly with provisions like Zero FIR, online registration of police complaints, electronic summonses, and mandatory videography and forensic team visits to crime scenes for all heinous crimes. Electronic reporting of crimes is now a reality, eliminating the need to visit a police station physically and allowing for quicker action by the police. However, the complainant has to visit the police station within three days to sign the complaint physically. With the introduction of Zero FIR, a First Information Report (FIR) can be filed at any police station, regardless of jurisdiction, ensuring immediate reporting of offences. Empowering citizens to report crimes via text message or electronic mode will help them navigate the legal process without fear of stigma or hesitation.

Zero FIR is not mentioned in any of the new laws. However, a Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPRD) SOP (Standard operating procedure) seeks to institutionalise the concept of Zero FIR. When a case is reported at a police station other than the police station where the actual crime was committed, a Zero FIR is supposed to be registered by adding a Zero before the FIR number and then transferred to the police station where the crime occurred. The SOP needs to be revised to enlighten the mode of transfer of the FIR to the other police station. Will it be sent online, by post, special messenger or another mode? Is there any app or platform developed to transmit such FIRs nationwide? What happens when the recipient police station finds the crime mentioned in the FIR did not occur in their jurisdiction? Will they register another Zero FIR or return the same? The document needs more details.

In a case of crime against the body, a medical examination in a government hospital is mandatory. Who will get this examination conducted before the evidence is lost or contaminated remains unanswered in the SOP. With time, the police will find answers, and the courts will give appropriate directions.

Section 173(3) BNSS provides discretion to a police officer in registering an FIR in a cognisable matter if the offence is punishable with three or more years but less than seven years of imprisonment. The officer in charge of a police station ‘may’ (and not ‘shall’) proceed with investigation or conducting preliminary enquiry with the approval of his deputy superintendent of police or do nothing. This enquiry is mandated to be completed within fifteen days. The Apex Court first permitted preliminary enquiry in the Lalita Kumari case. Some people familiar with the police functioning suspect this provision may be misused by unscrupulous investigating officers to extract bribes or favours from the complainant and the accused. For example, the offence of cruelty to married women is still punishable with a maximum of three years of imprisonment; in all such cases, the victim, a married woman, will have to wait till the police officer makes up his mind to take up the investigation.

There should be no scope for discretion at the police’s end. Secondly, the law does not define the procedure for this preliminary enquiry. Will it be a cursory enquiry to ascertain the probability of commission of a cognisable offence, or will it be a full-fledged preliminary enquiry on the lines of the CBI’s preliminary enquiry, often termed PE? No SOP has so far been issued either by the police think tank BPRD or any state government for the guidance of field-level police officers.

Section 46 BNSS explicitly allows the police to handcuff the accused during arrest or court production for offences like rape, acid attacks, human trafficking, and sexual crimes against children. In several cases, criminals have taken advantage of the non-handcuff provisions to escape from police custody. It is undoubtedly a welcome step.

In the event of an arrest, the arrested person has the right to inform a person of their choice, ensuring immediate support. Arrest details will also be prominently displayed in police stations and district headquarters. The progress of the case will also be shared with the complainant from time to time.

Women, along with other vulnerable groups such as male children under 15, individuals over 60, and ill persons, etc., now need not go to the police stations to depose or record their statements in certain proceedings (proviso to Section 195(1) BNSS). Now, in rape cases, the proviso to Section 176(1) BNSS allows the police to record the statement of a rape victim through audio-video means, including mobile phones. A female police officer will record statements of rape victims in the presence of a guardian or relative, and medical reports must be completed within seven days.

The issue of enhanced police custody from 15 to 60 or 90 days (Section 187, BNSS) has invited sharp reactions. The proviso to Section 167(2)(a) of the repealed CrPC allowed a magistrate to extend custody beyond 15 days as long as it was not in police custody, meaning that beyond 15 days, the person had to go to judicial custody. However, the corresponding Section 187(3) of the BNSS has deleted the words “otherwise than in police custody” that exist in the CrPC, opening up the possibility of police custody for much longer duration than those envisaged in the UAPA [Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act] or erstwhile stringent legislation like the POTA (Prevention of Terrorism Act) and TADA [Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act].

However, the Union Home Minister clarified the new provision in a press conference. “I want to clarify that in BNS also, the remand period is 15 days. Earlier, if an accused was sent to police remand and got himself admitted to a hospital for 15 days, there was no interrogation as his remand period would expire. In BNS, there will be remand for a maximum of 15 days, but it can be taken in parts within an upper limit of 60 days,” [4] informed the Minister.

Forensic Push

The new laws make forensic investigation mandatory in offences punishable by seven years or more. The MHA aims to increase the conviction rate to 90 percent by involving forensic experts in spot visits and evidence collection, analysis, and presentation.

Section 176(3) of BNSS mandates compulsory inspection of heinous crime scenes by forensic experts, giving impetus to scientific investigation. In an adversarial judicial system, the judge relies on the parties to the present evidence. Properly collected, preserved, and tested forensic evidence from the scene of occurrence can help with inculpation and exculpation.

The new stipulation acutely burdens the existing forensic infrastructure regarding human resources and equipment. Only seven Central Forensic Science Laboratories (FSLs), 29 State FSLs, and over 50 Regional FSLs exist. Walking the talk, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) had launched mobile forensic vans in Delhi to test the waters much before the passage of the laws. The results have been encouraging. Days after assuming office, the Modi 3.0 regime greenlit the MHA’s ambitious proposal for the National Forensic Infrastructure Enhancement Scheme (NFIES) with an allocation of Rs 2254.43 crore for the next five years. The scheme targets enhanced forensic human resources by establishing forensic science universities nationwide. This strategic move is designed to bolster capacity and efficiency in forensic examinations, mitigate the scarcity of trained human resources, alleviate backlogs, and align with the MHA’s target of exceeding a 90% conviction rate.

Videography and photography of the crime scenes are also made mandatory. Crime scene photography is quite different from casual mobile photography. This is one area where the states and the Centre will have to pay immediate attention by providing hardware (mobiles with good camera resolution) and training to all investigators in a phased manner.

The National Informatics Centre (NIC) has developed apps for storing digital evidence, recordings, pictures, etc. Still, the SOP for collection, search and seizure, storage, chain of custody, authentication, transmission, analysis, and presentation is yet to be developed. In contrast, the USA’s guidelines on the subject, issued in 2020 by the National Institute of Justice, US Department of Justice, clearly lays down the policies and procedures for digital evidence.

The whole judicial system is mired in humongous pendency. According to the National Judicial Data Grid, at the beginning of 2024, more than five crore cases were pending trial in various courts. The pileup has doubled in the last two decades. These cases include 169,000 cases pending for over 30 years in the district and high courts. According to a strategy paper by Niti Ayog 2018, it would take 324 years to clear this backlog at the current pace!

The pendency of court cases costs 1.5-2% of our GDP. The Rule of Law Index 2023, a country ranking published by the World Justice Project, ranked India 111th out of 142 countries in civil justice and 93rd in criminal justice.

In 1987, the Law Commission, in its 120th report on Manpower Planning in the Judiciary, recommended 50 judges per million population in a phased manner. Unfortunately, we have not yet reached the halfway mark of the desired level of judicial access. Fortunately, the government of India has pushed to reimagine substantive laws and widespread technology use and court processes in the new laws.

Section 183(6)(a) BNSS mandates that statements in certain sexual assault cases be recorded by a female judicial magistrate or, in her absence, by a male judicial magistrate in the presence of a woman. There was no such provision in the CrPC.

Another provision of Section 183(6)(a) BNSS requires a judicial magistrate to record a witness’s statement in cases punishable by ten years or more, life imprisonment, or death, including certain offences against women. For maintenance cases, Section 145 BNSS (previously Section 125 CrPC) allows dependent parents, including mothers, to file for maintenance at their residence, removing the previous requirement to file only at the ward’s residence.

Trial Stage Level

Section 21 BNSS (previously Section 26 CrPC) still provides that a woman judge shall preferably preside over court trials for certain women-sensitive offences. Also, the term ‘some adult male member’ in Section 64 CrPC, relating to serving summons, has been replaced with ‘some adult member’ in its succeeding provision of Section 66 BNSS, recognising women as capable of receiving court-issued summons on someone’s behalf. The BNSS also allows for the electronic setup of court proceedings, which makes it easier for the complainant and witnesses to depose without fear or favour.

Addressing the J20 Summit at Rio de Janerio on digital transformation and the use of technology to enhance judicial efficiency, the CJI claimed that “virtual hearings have democratised access to the Supreme Court.” He announced that over 750,000 cases were heard over videoconferencing and more than 150,000 cases were filed online as technology has renegotiated the relationship between law and enforcement agencies, including the judiciary. [5]

It is heartening that the central government is providing liberal budgetary support to unite all criminal justice system stakeholders through seamless communication and data exchange. It has committed INR 7,000 crore to the Phase III eCourts Project, which will be implemented over the next four years.

The new laws aim for justice to be received up to the level of the Supreme Court within three years of the registration of the FIR. The BNSS stipulates that charges should be framed within 60 days of the first hearing. Only two adjournments are provided, eliminating the ‘tarikh pe tarikh’ culture. Judgments in criminal cases are expected to be delivered within 45 days of trial completion.

The BNSS also permits trials in absentia of those criminals who have fled the country to evade prosecution. All the absconding proclaimed offenders can now be tried and awarded punishment in their absence. The CrPC only allowed the evidence to be recorded in the accused’s absence. The new provision paves the way for faster extradition of the fugitives from their safe havens.

The Outreach

Coinciding with the rolling out of the three criminal laws on July 1, the officers-in-charge of all police stations and senior supervisory officers in the country organised public interactions to highlight the critical features of the intent behind the enactment of the Bhartiya Nyaya Samhita, Bhartiya Nagaril Suraksha Sanhita and the Bhartiya Sakshya Adhiniyam. The outreach involved women, youth, students, senior citizens, retired police professionals, eminent personalities, self-help groups, etc., to spread awareness about the key objectives behind the replacement of the British era IPC, CrPC and Evidence Act to put the “Citizens First, Dignity First and Justice First.”

The new laws aim to enhance the use of technology in the investigation and trial of cases. Around two dozen modifications have been made in the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems(CCTNS) software to make it technologically compatible with the new laws and a host of mobile applications like National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB) Sankalan, e-Sakshya (for electronically capturing evidence including forensics), Nyaya Shruti (for judicial hearings and onboarding of related documents) and e-Summons (for electronic delivery of court summonses) put in place to facilitate easy transition. The CCTNS 2.0 application e-connects police stations, forensics, prosecution, courts, and prisons.

Some critics have noted a need for more institutional preparedness before rolling out the new laws. Despite the general elections, the police leadership ensured that most of the investigating officers at the thana level had undergone refresher training, and handbooks were published for distribution among these personnel. This author spoke with several police chiefs, senior officers and ground-level officers who exuded confidence in rolling out the new laws without any hitch. Some, however, mentioned that some old police officers who were not comfortable with the digital upgrade of skills were mulling and seeking a posting in the non-investigative wings of the police.

Some find that over-reliance on deterrence, enhanced punishments, increased minimum sentences and fines, and death sentences do not go well with modern criminal jurisprudence. They are also quick to point out that the penalties prescribed are rehabilitative and restorative only in a few cases. For crimes like rape of a woman under 16 or 12 years of age (S. 65 BNS) or gang rape (S. 70 BNS), the fine may be reasonable. However, such penalties do not exist for many offences, such as rape or aggravated rape (S. 64 BNS) and sexual intercourse by a person in a position of authority (S. 68 BNS).

Community Service: A Hesitant Start

Among the fundamental positive changes in the new laws is introducing community service as an alternate punishment for some offences. Community service is essentially a work that the court may order, without any entitlement to any remuneration, that benefits the community. Though it is mentioned in the Statement of Objectives, BNS has introduced community service for just six offences, such as public servant unlawfully engaging in trade(S 202 BNS), misconduct in public by a drunken person (S 355 BNS), defamation (S 356(2) BNS), etc. Several other petty crimes, such as committing a public nuisance, stay outside the community service ambit.

Indian prisons are teeming with under-trial prisoners. Nearly three-fourths of prisoners are those awaiting trial. Community service as an alternate form of punishment keeps first-time offenders and minor felons out of prisons, affording an opportunity to reform. The new laws have yet to take this opportunity. Hopefully, with the positive outcomes of the new provisions, the Government will be encouraged to expand the scope of community service in the coming days.

The BNS, however, does not define community service, leaving it to the judges’ discretion. Respective high courts and the Supreme Court can form a committee to devise a uniform award for community service.

There is broad consensus that the new laws are a step in the right direction. In the first 45 days of their enforcement, no criticism of the laws or inadequacies, particularly of the police, has been highlighted, which speaks volumes about the enhanced capabilities and efficient service delivery. No media, courts, critics or even the Parliament (which was in session) has discussed any systemic failures even in the initial days of implementation, which is a tribute to all the stakeholders in the criminal justice system.

The ‘Whole of Government’ approach played a crucial role in rolling out these transformative and pro-victims new criminal laws through support and wholehearted involvement from various government departments. As far as laws are concerned, they will remain subject to interpretation and amendment to be more inclusive and comprehensive.

There is a definite need for evolving standard procedures to amplify the spirit of the new laws, leaving nothing to discretion.

The role of police leadership would be to ensure the correct and just use of the laws, limiting any abuse of authority and miscarriage of justice.

Author Brief Bio: Shri Somesh Goyal is an IPS officer of the 1984 batch allocated to Himachal Pradesh. He is a former Director General of Police with over 37 years of experience having served in the Police, Prisons, and CAPFs like SPG, NSG, BSF, and SSB. He is known for excellent operational innovation and has won a host of awards including, the President’s Police Medal, the Police Medal for Meritorious Service, Kathin Sewa Medal with Bar, and Maharana Pratab Trophy for Best Border Management. He is a post-graduate in English Lit. and Journalism & Mass Communication. He is an alumnus of National Defence College.

References:

[1] https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1852024

[2] https://news.abplive.com/news/india/3-new-criminal-laws-bharatiya-nyaya-sanhita-bns-bnss-bsa-to-take-effect-monday-june-1-replacing-ipc-crpc-evidence-act-key-reforms-1699321

[3] https://translaw.clpr.org.in/case-law/navtej-singh-johar-vs-union-of-india-section-377/

[4] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/police-remand-period-continues-to-be-15-days-under-bns-union-home-minister-amit-shah/articleshow/111407798.cms?from=mdr

[5] https://lawbeat.in/top-stories/virtual-hearings-democratised-access-supreme-court-cji-chandrachud

Latest News

Bharat: Awakening and Churn

Religious Reservations in India: Past and the Future

Uniform Civil Code – Equality More Than Uniformity

Leave a comment, cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Please enter an answer in digits: nineteen − eighteen =

Adding {{itemName}} to cart

Added {{itemName}} to cart

Reforms in Criminal Justice System

The Criminal Justice System is a system comprising of various organisations/institutions that are involved in the procedure of bringing a crime to justice. Majorly there are three components of the system vis – a – vis Police, Judiciary, and Prisons which all work in synergy to ensure the proper delivery of Justice.

In the history of independent India, various reports have been published/suggested for reforming the justice system. Various reports of the Law Commission of India and of dedicated committees formed, have submitted their reports for the betterment of the ageing and inefficient criminal justice system. In this article, we’ll explain to you the reports of the Justice V.S. Malimath Committee and the Madhav Menon Committee.

The topic has a high probability of being asked as a Current Affairs Question in IAS Prelims. Visit the attached link to attempt practice quizzes on current affairs .

Note: UPSC 2023 is approaching closer, supplement your preparation with the free UPSC Study Materials by BYJU’S.

Note: Visit the attached link to understand the Criminal Justice System of India in a simplified yet detailed manner.

Need for Reforms

There are many reasons to overhaul the current criminal justice system, this is admitted by the Union Government of India itself. The major reasons are listed below:

- Complex Process: The process is so cumbersome and complex that it is very difficult for common men to understand it. Keeping a large section of society unaware of the justice system makes way for the misuse of the innocence of the people and complexity of the system by law practitioners and police.

- Colonial Foundation : The laws have not undergone any major changes since India gained its independence.

- Delayed Delivery of Justice: Indian judiciary is overburdened with huge piles of pending cases.

- Status of Undertrials : More than 63% of accused are undertrials in Indian prisons.

- Corruption : Lack of transparency, at all levels but especially at lower levels, compromises with the justice delivery.

- No Fixed Accountability : Police officials in India are not provided with enough freedom to take up the matter and investigate when the cases are high profile, in such scenarios, they are required to function at the will of the political class.

V.S. Malimath Committee on Reforms in the Criminal Justice System

Justice V.S. Malimath had been the chief justice of Kerala and Karnataka high court and was the head of this 6 member committee which was constituted in the year 2000 and submitted its reports three years later in the year of 2003. The Malimath committee made 158 crucial suggestions, but none of them were accepted and implemented. Below are the most prominent recommendations made by the Malimath Committee:

- Creation of National Security Commission, and State Security Commissions.

- For maintenance of crime data, appointing additional SP in each district was suggested.

- Organise Specialised Squads for dealing with organised crimes.

- Creating a Police Establishment Board for matters related to postings and transfers, etc.

- For probing inter-State or transnational crimes, a special team of officers must be constituted.

- Increasing the police custody period from current 15 days to 30 days and an additional period of 9 days for filing of charge sheet in cases of serious crimes.

- Investigative Practices: It felt the need of borrowing certain features of investigative procedures followed in countries such as Germany, and France. The judicial magistrate should be responsible to supervise the whole investigation and the courts should be granted the powers to summon anyone for examination if required, even if he/she is not listed in the witness list.

- Right to Silence: The Article 20 (3) of the Indian Constitution should be amended in such a way as to allow the courts to infringe on this right of the accused and make him/her provide information which could go against himself/herself.

- Rights of the Accused: A charter should be launched in all the languages so as to make the people aware of their rights and know the steps to make them get enforced and whom to approach if it doesn’t get enforced in the way it should have been.

- Innocence Until Proven Guilty: the practice of presuming the accused to be innocent and unreasonably burdening the prosecution to prove otherwise should be done away with. Instead, a fact should be considered as proven if the court is so convinced subject to its complete evaluation of all the matters in front of it.

- In all the cases of serious crimes, the victim should be allowed to take part in.

- If the victim is dead, his/her legal representative should have the right to take part in the investigation of such a case.

- In case the victim can’t afford it, he/she should be provided an option of choosing a lawyer of his/her choice by the state and the cost involved must also be borne by the state itself.

- The compensation to the victim in all serious crimes, is the responsibility and an obligation on part of the state, irrespective of the fact of whether the accused is apprehended or not, convicted or acquitted.

- It also suggested creating a victim compensation fund, which could be funded with the money received after auctioning the items confiscated in the organised crimes.

- Dying Declarations: it suggested the law to authorise the audio/video recorded statements, confessions, and dying declarations.

- Public Prosecution: the creation of a new post of Director of Prosecution in each state who will ensure effective coordination between the prosecution wing and the investigation wing of the police, using the guidance of the Advocate General of that state. It is also recommended to appoint the public prosecutors and assistant public prosecutors by means of a competitive exam instead of departmental promotions. These appointees shouldn’t be posted in their home districts or where they are already practising.

- Judges and Courts: The committee suggested increasing the number of judges in Indian Courts. It also suggested separating the division of criminal proceedings from the ordinary ones in High Courts and the Supreme Court, and allotting such cases to only those judges who have a proven experience and expertise in criminal laws. It also suggested the creation of a National Judicial Commission.

- Witness Protection: The witness should be treated with dignity; be provided with allowance on the same day; be provided with proper seating and resting facilities. A Witness protection law must be made on the lines of one that is in the USA.

- Perjury: The witness must be fined and/or imprisoned and be tried if he/she is found to be providing false information so as to influence the natural course of the case.

- Court Vacations: Considering the number of pending cases before the court, the committee suggested reducing the vacation period of the courts by 21 days.

- Arrears Eradication Scheme: Under this scheme, the cases which are pending for more than 2 years are to be settled by the Lok Adalats on priority. Such cases will be heard daily and no adjournment is allowed.

- Creation of permanent statutory permanent committee for suggesting sentencing guidelines.

- House arrest instead of prison sentence for pregnant ladies and women who have a child less than the age of 7 years, considering the child’s future and wellbeing.

- Settlement without any trial in cases where the interest of the society is absent. In case he/she cannot afford to pay a fine, some form of community service could be arranged for the convict.

- Life imprisonment to replace a death sentence without the scope for commutation or remission.

- Update Indian Penal Code (IPC) for adding or removing crimes as per the changing times.

- Economic Code

- Criminal Code

- Correctional Code

- Social Welfare Code

- Other Offences Code

- Periodic Review: The criminal justice system of India should be reviewed periodically by a committee constituted by the President of India.

Note: Visit the attached link to read about the Malimath Committee report from IAS Prelims point of view.

Madhav Menon Committee on Reforms in the Criminal Justice System

N.R. Madhav Menon was the head of the 4 member committee entrusted to draft the “Draft National Policy on Criminal Justice”. The committee submitted its report in the year of 2007, advocating a complete overhaul of the whole criminal justice system of India. The draft contained some provisions that are recommended by the V.S. Malimath Committee as well in 2003, like re-categorisation of offences within IPC; creation of National Security Commission, and matters related to rights of the victims among others.

The re-classification of offences as per this report should be on the basis of the following criteria:

- Social Welfare Offences Code: Punishment should not be the focus here, rather reparation and/or restitution be .

- Correctional Offences Code: Involving crimes that have the provision of imprisonment of up to 3 years and/or fines.

- Grave Offences Code: Involving crimes that have the provision of imprisonment of beyond 3 years and/or death.

- Economic Offences Code: For crimes that are related to economic security and other financial laws.

All the above 4 categories will contain the detailed nature of trial, rules of procedure, and types of punishments.

The committee also suggested for the creation of a victim compensation fund for those who turned out hostile due to the pressure from the culprits.

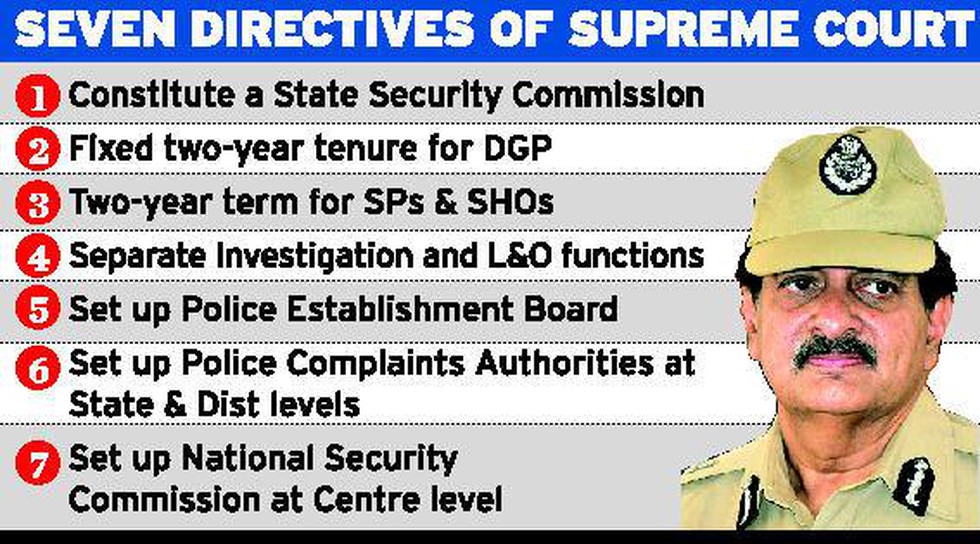

SC Judgement on Police Reforms

The Supreme Court of India in the year 2006, in the Prakash Singh v/s the Union of India case, gave 7 directives to all the States and Union Territories for carrying out police reforms. The major aim of the directives was to free the police system from the unwarranted interference and pressure from the political rulers and do their duty with full self-accountability. The Public Interest Litigation (PIL) was filed by a retired DGP (Director General of Police) having served in UP Police and Assam Police in the year 1996 seeking police reforms.

The case took a decade to conclude into what is considered as to be one of the most important judgments ever given by the Supreme Court after the Kesavananda Bharati case of 1973.

Following were the 7 Directives for Police Reforms propounded by the Supreme Court in 2006:

- Create a State Security Commission (SSC) for ensuring no unwarranted pressure or interference is exercised on the police by the respective state government. The SSC will also be responsible for evaluation of the performance of the state police and to institute broad policy guidelines.

- The DGP must have a minimum tenure of 2 years and should be appointed via a transparent merit based process.

- Superintendents of Police (SP) of a district, the Station House Officers (SHOs) of each police station and other police officials on operational duty must also have a minimum 2 years of tenure .

- Hive off the prosecution, investigation, law and order, and other functions of the police.

- Giving decisions on the matters related to police officials below the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP), such as transfers, postings, promotions among other service-related matters.

- For police officers above the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP), recommend upon the matters such as postings, and transfers.

- State Level: To enquire into and deal with public complaints against officers above the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) including the DSP itself, in matters of serious misconduct such as rape in police custody, grievous hurt, custodial death, etc.

- District level: With the same provisions and powers as above but for the police personnel who are below the Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) rank.

- For the purpose of selection and placement of Chiefs of CPOs (Central Police Organisations) with a minimum tenure of 2 years, create a National Security Commission (NSC) for constituting a panel for the said purpose.

Implementation Status of SC Directives

As per a study report published by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), not even a single State /Union Territory in India has completely adhered to the above directives. Some have implemented a few among those in a manner so as to make the implementation useless and just for the namesake. It found that 18 states have passed the amendments to their respective Police Acts in pursuance of these directives. By and large, the Police is still under the control and influence of the State Governments and this hampers the overall criminal justice system as the officials feel hesitant to even file the cases, let alone investigate it honestly and ensure the delivery of justice.

It is important to understand that it is the action of the police which marks the beginning of the long process of justice delivery, an inaction on its part or an action under the undue influence of State Governments simply means denial of justice. The judges of already overburdened courts have limited capacity to take suo moto cases and oversee the investigations done by the police.

Recent Developments

- Union Home Minister Mr. Amit Shah has sought suggestions to make the criminal laws of India more people-centric. The suggestions have been primarily sought by the Chief Justice of India (CJI), Chief Ministers (CMs), and Members of Parliament (MPs) among others.

- In his statement, Mr. Amit Shah hinted that the days of third degree tortures will soon be over.

- The government is keen to make changes in the Indian Penal Code (IPC), the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), and the Indian Evidence Act.

- At a recent meeting of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) core group, experts have expressed their serious concerns on the sluggish speed of reforms being made in the Criminal Justice System of India.

Start your IAS Exam preparation by understanding the UPSC Syllabus in-depth and planning your approach accordingly. UPSC 2023 is approaching closer, keep yourself updated with the latest current affairs for UPSC, where we explain the important news in a simplified manner.

You can also make your daily current affairs revision robust using Free Monthly Magazines by BYJU’S .

Related Links:

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- Current Issue

- Election 2024

- Arts & Culture

- Social Issues

- Science & Technology

- Environment

- World Affairs

- Data Stories

- Photo Essay

- Newsletter Sign-up

- Print Subscription

- Digital Subscription

- Digital Exclusive Stories

- CONNECT WITH US

India’s criminal law overhaul: An essential backgrounder

New rules aim to update justice system, but some fear they may bite off more than they can chew..

Published : Jul 12, 2024 19:55 IST - 1 MIN READ

READ LATER SEE ALL Remove

Advocates holding the banner of the All India Lawyers Union stage a protest demanding a halt to the implementation of new criminal laws, in Visakhapatnam on July 11, 2024. | Photo Credit: V RAJU / THE HINDU

The Centre has implemented new criminal laws effective July 1, 2024. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), and Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) have replaced the Indian Penal Code (IPC), Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), and Indian Evidence Act, respectively.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi stated these reforms aim to “eradicate the mentality and symbols of slavery” and create a “new confident India.” The government argues that the new laws prioritise justice and fairness over punishment alone. However, legal experts and civil rights advocates have raised concerns about these changes.

The new laws include provisions that alter existing legal procedures. For instance, they grant expanded powers to the police, allowing preliminary inquiries before registering First Information Reports (FIRs) for certain offenses. Critics argue this could lead to increased police discretion and potential delays in filing cases.

Also, the new laws have effectively reintroduced provisions similar to the previously stayed sedition law, prompting concerns about potential impacts on freedom of speech. The omission of a provision comparable to Section 377 of the IPC has raised questions about legal protections for certain non-consensual sexual acts.

Some observers have criticised the rapid passage of these laws, citing limited debate and discussion. There are also concerns about the potential impact on pending litigation and a possible increase in the number of cases awaiting trial.

As India transitions to this new legal framework, Frontline presents a collection of stories and interviews examining these criminal and civil laws, their implications for Indian citizens, and their potential effects on India’s democracy and judicial system.

‘The new criminal laws are like old wine in new bottles’: Rebecca John

New criminal laws push India toward a regressive past

Father Stan Swamy: Silenced in death

G.N. Saibaba’s acquittal prompts calls to scrap UAPA

Sedition law report: A regressive step by Law Commission

Dangerous haste to reform criminal law

Sudha Bharadwaj: ‘A lot of democratic space has been lost’

Parliamentary panel’s draft proposal to make adultery a crime contradicts landmark SC judgment

Why UAPA is a threat to media freedom in India

Uniform Civil Code: Clash of moral universalism and cultural pluralism

The Centre’s controversial makeover of crucial criminal codes can have far-reaching impacts

The fallacy of one nation, one examination

Editor’s Note: Dirty skeletons in the NEET closet

- Bookmark stories to read later.

- Comment on stories to start conversations.

- Subscribe to our newsletters.

- Get notified about discounts and offers to our products.

Terms & conditions | Institutional Subscriber

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide to our community guidelines for posting your comment

Criminal Justice System in India

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- R. Thilagaraj Ph.D. 4

3006 Accesses

2 Citations

The Union of India is a Federal Polity consisting of different states. The states have their own powers and functioning under the Constitution of India. The Police and Prison are the state subjects. However, the Federal laws are followed by the Police, Judiciary, and Correctional Institutes. The system followed in India for dispensation of criminal justice is the adversarial system of common law inherited from the British Colonial Rulers. This paper explains the structure, powers, and functioning of the three vital agencies of the Criminal Justice Administration of India, namely, the Police, Judiciary, and Correctional Administration. This paper also explains the community-based corrections, Juvenile Justice System, and Intervention of Apex Court for effecting the function in the Criminal Justice System in India.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Penitentiary System and Community Justice in Mexico

Crime and Punishment

The Position of the Public Prosecution Service in the New Swiss Criminal Justice Chain

Chakrabarthi, N.K. (1999). Institutional Corrections in the Administration of Criminal Justice . New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications Pvt. Ltd.

Google Scholar

Chandrasekharan, K. N. (2008). Public prosecution in India . In Paper presented at the 4th Asian Human Rights Consultation on the Asian Charter of Rule of Law in Hong Kong.

Chauhan, B., & Srivastava, M. (2011). Change and Challenges for Indian Prison Administration, The Indian Police Journal , Vol, LV111 (1). Jan-Mar, 2011. Pg 69–86.

Diaz, S. M. (1976). New Dimensions to the police role and functions in India . Hyderabad: National Police, Academy.

Ganguly, T. K. (2009). A discourse on corruption in India . New Delhi: Alp Books Publications.

Gautam, D. N. (1993). The Indian police: A study in fundamentals . New Delhi: Mittal Publications.

Kelkar, R. V. (1998). Lectures on criminal procedure . Lucknow: Eastern Book Company.

Krishna Iyer, V. R. (1980). Justice and beyond . New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications.

Krishne Mohan, M. (1994). Indian police: Roles and challenges . New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House.

Nehad, A. (1992). Police and policing in India . New Delhi: Common Wealth Publishers.

Nitai, R.C. (2002). Indian prison laws and correction of prisoners . New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications Pvt. Ltd.

Raghavan, R. K. (1989). Indian police: Problems, planning and perspectives . New Delhi: Manohar Publication.

Saha, B. P. (1990). Indian police: Legacy and quest for formative role . Delhi: Konark Publishers Private Limited.

Sen, S. (1986). Police Today . New Delhi: Ashish Publishing House.

Sethi, R. B. (1983). The police acts . Allahabad: Law Book Co.

Shankardass, R. D. (2000). Punishment and the prison: Indian and international perspectives . New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Thilagaraj, R. (1988). “ Role of police, juvenile court and correctional institutions in the Implementation of Juvenile Justice Act 1986 ”, Journal of the Madras University, Vol. LX. pg no 44–48.

Thilagaraj, R., & Varadharajan, D. (2000). “Probation: Approach of the Indian Judiciary” The year book of legal studies (Vol. 23). Chennai: Directorate of Legal Studies.

Trivedi, B. V. (1987). Prison administration in India . New Delhi: Uppal Publishing House.

Walmsley, R. (2008). World prison population list . London: Kings College.

Weiner, M. (1991). The Child and the State in India: Child Labour and Education Policy in Comparative Perspective . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Criminology, University of Madras, Chennai, 600 005, Tamil Nadu, India

R. Thilagaraj Ph.D.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to R. Thilagaraj Ph.D. .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, University of Macau, Taipa, Macao, Macao

Jianhong Liu

Centre for Criminology and Criminal Just, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Bill Hebenton

School of Criminology, National Taipei University, Taipei, Taiwan R.O.C.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Thilagaraj, R. (2013). Criminal Justice System in India. In: Liu, J., Hebenton, B., Jou, S. (eds) Handbook of Asian Criminology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5218-8_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5218-8_13