Search for creative inspiration

19,898 quotes, descriptions and writing prompts, 4,964 themes

loneliness - quotes and descriptions to inspire creative writing

- an open letter to youth

- fear of loss

- quotes of loneliness

- quotes of self love

- self isolating thought patterns

- stand alone mode

- therapy dogs

Loneliness was an echo chamber for my pain. Solitude began when the pain was over, when I loved myself and had healed.

As time went on, loneliness felt more as solitude, for one finds ways to cope. Yet to have real company of one who loves me, that would be sweet indeed.

They say once you have mastered being alone, you are ready for the company of others, that doesn't make it easy though. When everyone's life journey separated from my own, when the only heart beating in this house belonged to me, it wasn't something most could take. For there are days when the brain becomes a cold fire, perhaps that is what others call panic, but when you are alone, who are you going to call? I guess the good news is that in time, after many unpleasant days, you are okay. Then you find joy again, or maybe it finds you. After that, your journey can change, take on new and exciting adventures... I wish I could wave a magic wand for you who are alone, but there are somethings you must learn the hard way, my love.

This loneliness is a vice on my heart, squeezing with just enough pressure to be a constant pain. It kills me every day just a little bit more, taking what was once my inner light and replacing it with a darkness that overshadows each moment. It is the fuel of my nightmares, the reason I struggle to breathe when a new shock comes. Where is the limit? When comes the point at which dogs are called off and the help begins? Because I need to know; I really need to know.

When friends feel like paper chains in the rain and the sky holds nothing but the promise of more storms, life is lonely. When all I want is a hand to hold or an arm about my shoulders and none comes, the world becomes cold and empty, a slow poison for the soul. We are born to be loved and nurtured, and to do the same for others. We are born to be in tribes with social bonds that last a lifetime. It's times like this I wish I could melt in the rain like those paper people, fade away, anything to stop the ever-present pain.

Loneliness was Keller's only dependable friend, there morning, noon and night. Cigarettes ran out, whiskey ran dry, but always the empty yawning persisted. Nothing ever touched it, not his love affairs or the bar room boys, and never the social media that was his constant poison.

Loneliness sounds like such an easy thing to fix: find a friend, reach out to someone who cares. Every time I try they recoil, unwilling to offer an olive branch of hope to the social leper, and so my anxiety deepens. There are nights it takes a hold of me. All I can do in those long black hours is find an enclosed place to shake until the tears subside and I can focus on the dawn light, breathe, drink water. It isn't simply a lack of company, though that's part of it for sure, it's a black hole that grows more powerful with every social snub. It threatens to swallow every part of me, bad and good, until all that's left is a human shaped shell too numb to feel the pain anymore.

Her friends were as vapid as the winter snow was cold. Their love extended only as far as a social media post, stopping abruptly at the pixellated screen. Their smiles were little yellow faces that stopped coming whenever her world fell apart, which was often. From their posts their lives were one constant party, wine and meals in fancy establishments. Every post fed her loneliness, hacked at the tenuous emotional connections she nursed. She used to only feel the cruel bite of isolation in crowds, now it followed her home, an ever present reminder that she was a failure on every front.

Sign in or sign up for Descriptionar i

Sign up for descriptionar i, recover your descriptionar i password.

Keep track of your favorite writers on Descriptionari

We won't spam your account. Set your permissions during sign up or at any time afterward.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Writing Tips Oasis - A website dedicated to helping writers to write and publish books.

How to Describe Loneliness in a Story

By Isobel Coughlan

There are many ways you can write a lonely character in your book. In this post, we share some tips on how to describe loneliness in a story. Read on to learn more!

Something that is intense, serious , or difficult to deal with.

“His heavy loneliness followed him everywhere, even when he was in a room full of people.”

“She was determined to shed her heavy lonely feelings, but it was proving easier said than done.”

How it Adds Description

“Heavy” shows that the feelings of loneliness are so strong that they’re weighing the character down. This adjective is usually reserved for extra powerful feelings, and it can imply characters have been suffering for a while. If a character experiences “heavy” loneliness, they might struggle to connect with others or have a fear that keeps them from reaching out for help.

Something that’s clear or easy to notice.

“She blushed as she entered the classroom alone. Her lack of companionship and loneliness was evident to everyone.”

“Though his secret feelings of loneliness weren’t evident , he was scared his peers knew he felt different.”

If you want to show a character’s feelings are clear or obvious, “evident” is an apt adjective. This shows that everyone in the story can see the character is lonely, perhaps because of their mood or actions. Some characters might try to befriend them if their loneliness is “evident,” but others may use this to tease them.

3. Fictitious

Something that doesn’t exist or is false.

“Quit this fictitious loner act! You have so many friends and admirers.”

“He says he’s lonely, but we think his feelings are rather fictitious . Don’t you?”

Some characters might feign loneliness for sympathy or attention. In these cases, the feelings are “fictitious” because the character is lying. Characters that create “fictitious” emotions are likely to annoy others. They’re also usually manipulative and want to gain something from their fake loneliness act.

4. Agonizing

Something that causes extreme mental or physical pain.

“His agonizing loneliness left him bedridden for weeks. He could feel his isolation deep in his bones.”

“The prisoner was left alone for weeks, and his solitude was so agonizing that he wailed in the evenings.”

Though loneliness is an emotion, in severe cases, some people complain that it causes physical pain. “Agonizing” signifies that a character feels so alone that it hurts, and this could be a call for help or a sign of desperation. “Agonizing” loneliness may also debilitate the character, leaving them depressed or difficult to be around.

5. Constant

Something that’s always there or occurs all the time.

“His constant loneliness felt like a friend now. He couldn’t imagine life without eternal solitude.”

“Though she surrounded herself with friends and family, the loneliness in her heart was constant .”

If the feelings of loneliness never leave your character, “constant” is an excellent description of the situation. This shows that the character is always burdened by their feelings, and it could show they’re a more emotional or tortured soul.

6. Embarrassing

Something that leaves you ashamed or shy.

“When he thought about it, his lack of companions was embarrassing . A pink tint spread across his cheeks as he dwelled on his lonely life.”

“It’s rather embarrassing to be lonely in this day and age. Why doesn’t he make friends online?”

“Embarrassing” describes a character’s shame caused by their loneliness. This also implies they care how others perceive them, and therefore they might be a quiet or anxious character. Nasty characters or bullies might make lonely characters feel “embarrassed” by highlighting their solitary nature.

Something that’s hidden or only known by a few people.

“His secret loneliness was hidden in the day, but at night he allowed himself to feel the sadness.”

“Only her sister knew about her secret loneliness, and she didn’t dare tell anyone else.”

You can use the adjective “secret” to show how your character hides their feelings from others in the story. This could be because they’re embarrassed of feeling alone, or it could be because they want to look brave and fit in. Characters who keep their loneliness “secret” might struggle when opening up to others or when showing their true personality.

8. Intricate

Something that features many details or small parts.

“She realized her loneliness was intricate , and there was no way she could describe it to another soul.”

“Loneliness is such an intricate emotion. You wouldn’t understand it unless you’ve felt it.”

If you want to add depth or complexity to your character’s suffering, “intricate” can signify the many causes of their loneliness. “Intricate” also implies that there’s a greater level of suffering, as the causes are more complicated than a simple lonely feeling. If a character suffers from “intricate” loneliness, others may try to help them but won’t be able to grasp the layers of the problem.

9. Comforting

Something that makes you happier and less anxious.

“At this point, the lady’s loneliness was comforting to her. It was simply all she had.”

“His comforting solitude was all he needed. He’d never complained about being lonely; it was normal to him.”

Some characters might be at ease when alone, and their loneliness might feel ”comforting” to them. This can indicate that they’re an independent character and happiest when alone. Other characters might find this strange and see them as a loner or standoffish.

Something gentle, kind, and harmless .

“Despite his complaints, his feelings of loneliness were benign, and he’d forgotten about them by the morning.”

“I wish my isolation was benign ! But this loneliness eats away at me every day.”

The adjective “benign” shows that the character’s loneliness is harmless, meaning it won’t damage their mental or physical health. Characters with “benign” loneliness will likely get over their feelings quickly, especially with the help of others. Other characters might feel pity for them, but in some cases, they may think that the lonely character is being over dramatic.

Search form

‘exquisite loneliness’: yale writer reflects on isolation and creativity.

Richard Deming

Richard Deming was at work on an essay about the 2008 film “Synecdoche, New York” when he received an unexpected phone call from an old friend. Philip Seymour Hoffman, the star of that very film, had just been found dead of a drug overdose.

The news was both shocking and sickeningly familiar. Deming, who’d had his own struggles with addiction, had known too many people who had fallen back into drug use after years of sobriety. He had come to believe that relapses were often a result of an inability to cope with a “desolation of loneliness,” feelings of isolation and alienation that, according to many surveys, are now rampant among Americans in general.

In his new book, “This Exquisite Loneliness” (Viking), Deming, a poet and senior lecturer in English in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, reflects deeply on how we might find human connection through our shared feelings of loneliness, rather than be consumed by them. In addition to pondering Hoffman’s 2014 demise, he delves into the lives of six brilliant figures — including the Austrian Expressionist painter Egon Schiele; “The Twilight Zone” creator Rod Serling; and the author Zora Neale Hurston — pinpointing the sources of their own feelings of loneliness, and how their efforts to understand it helped fuel their extraordinary creative endeavors.

“ I believe we must reinvent loneliness,” Deming writes. “I have been trying to do this my whole life.”

Deming, who also directs the Creative Writing Program in the Department of English, spoke to Yale News about his own addiction, making connections with readers, and Rod Serling’s backstory.

You define “exquisite loneliness” as a way of tapping into the pain of loneliness to fuel creativity or to find a deeper understanding of the self and others. How did you arrive at the word exquisite ?”

Richard Deming: It comes from my borrowing it from medical terminology. They talk about exquisite pain , and that was the sort of thing that I wanted to bring in. It’s very real and intense, but it opens up this attention to it, rather than it being ambient or environmental. I wanted that sense of a kind of directive pain.

Your own struggles with loneliness are woven throughout the chapters, and you cite pervasive loneliness as being at the root of your former alcohol addiction. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Deming: I think it’s built into it to a certain degree because addiction does tend to be isolating. But for me, part of addiction was trying to find methods to navigate the loneliness that I felt, and it was a way to kind of dull that pain. But then addiction just starts to feed in on itself, which all sounds much more conscious than it was. It wasn’t like, oh, I feel lonely, this will be the cure. I just wanted to not feel it, or much of anything for that matter.

How long did it take you to identify loneliness as one of the things you were trying to mask with alcohol?

Deming: Oh, years. That’s one of the things about both psychoanalysis and sobriety is that it does take time to rewire everything and get that kind of wider perspective on your drives and motivations.

For each of the subjects profiled in the book, you search for the roots of their own loneliness, whether it’s childhood trauma or racism or poverty or war. Which of the subjects resonated most deeply with you?

Deming: None necessarily more deeply than others. They were all very touching and insightful. About what they went through. I went with people who had different facets that helped me get to places that I might not have otherwise gotten to on my own. Taken together they could give me a fuller view of loneliness.

[The Austrian painter] Egon Schiele. I mean, his life is fascinating, but in that last year of his life, all the death that he faced in 1918 at the end of the First World War and the influenza epidemic—the death of his friend and mentor, Gustav Klimt, the death of his wife and unborn child, and then his own death? That was devastating.

Rod Serling. I did not know how much World War II was part of his story or about the losses that he felt early on—friends, family, his childhood home. I knew “The Twilight Zone” backwards and forwards, and I knew some of his story, but I didn't know all of it.

[The psychoanalyst] Melanie Klein. I first went to her because someone had recommended that I read her. And then I became interested in why she asked her housekeeper, “do you ever feel lonely?” Who was she, beyond just the mind, and what is the life that leads to that question?

Zora Neale Hurston was really fascinating because when she gets to Harlem, she is sort of fully incandescent. And there’s not much before that that sets that up.

So they all really, really spoke to me in different ways.

They all met tragic ends, some of their own doing. What are we supposed to make of that?

Deming: I wanted to make clear that there are stakes to loneliness. It isn’t something that gets cured for the people who have, you know, chronic loneliness. It’s part of their temperament.

But these figures — along with [philosopher] Walter Benjamin and [photojournalist] Walker Evans — all found ways of working with loneliness or through it. I mean, strangely, they also all have kind of an upbeat story. They all did astonishing things and had friendships and relationships and made things that are lasting. I wanted to show the ways that they not only opened up, but that they specifically reached out to others to use their loneliness to create something that can help others as well.

They each had their own area of brilliance. Do brilliance and loneliness go hand in hand?

Deming: Not necessarily. I tend to agree with, say, Melanie Klein or the evolutionary biologists, who say that loneliness really is part of human nature. But I think what can be brilliant is the way that someone finds to try to understand and direct their loneliness. That’s where the brilliance is.

In the opening of the book, you talk about the record levels of loneliness in the United States. But your book isn't a prescription for loneliness. What are you hoping that readers take away?

Deming: Key to me is this idea that we’re not alone in our loneliness. Part of the problem with loneliness is that it’s so stigmatized that people are reluctant to recognize their loneliness or will go to great lengths not to confess it to other people, let alone even themselves. These incredible figures had it and we can see that if they could try to acknowledge and understand feeling emotionally isolated, each of us can do that.

Are you pleased with the reception the book has received so far?

Deming: It’s been interesting to already be getting emails from people and even a handwritten letter. Recently I had an email from a twentysomething living in Brooklyn who said, “Oh, this helps me feel seen. I’ve been ashamed to admit my loneliness to anyone.” And I wrote back, that was my hope for this book, that people would feel like their loneliness is seen and acknowledged. In general, art is to me like evidence of other people’s searching for their own meaningfulness, as if they were calling over from their own lost valleys.

Arts & Humanities

Media Contact

Allison Bensinger: [email protected] ,

Getting to net zero

Empowering students and faculty to bring innovative ideas into the world

Meet the 2024 Yale Ventures Summer Associates

Harnessing the forces of architecture

- Show More Articles

We’re sorry, this feature is currently unavailable. We’re working to restore it. Please try again later.

- Our network

The Sydney Morning Herald

This was published 3 years ago

‘No more bingo!’ How creative writing is telling the true story of loneliness in old age

By jewel topsfield, save articles for later.

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Gurney, a 90-year-old aged care home resident in Victoria, once told sociologist Barbara Barbosa Neves that everyone seemed to think bingo was sex for old people.

He begged to differ. “I have had enough of bingo!” he told her. “I want to join a youth club or go roller-skating – everything except bingo.”

Sociologist Barbara Barbosa Neves is passionate about addressing the impact of loneliness on older people. Credit: Luis Enrique Ascui

Dr Barbosa Neves, a senior lecturer in sociology at Monash University, was interviewing Gurney (not his real name) as part of her research into how people living in aged care homes experience loneliness.

“He was a very funny participant,” she says. “He was extremely lonely and humour can be a coping mechanism.”

Dr Barbosa Neves is passionate about addressing the impact of loneliness on older people. “The title of one of the papers I wrote was a quote from one of the participants: ‘It’s the worst bloody feeling in the world.’ ”

She points to a University of Sheffield-led global study last year that found between 35 and 61 per cent of older people in aged care facilities feel lonely, which is considerably higher than those living in the community or the general population.

“Loneliness increases the risk of illnesses including dementia. It increases dementia by 40 per cent regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, education and even the genetic risk,” Dr Barbosa Neves says.

In Canada Dr Barbosa Neves led teams designing digital technologies such as communication apps for older people in long-term care facilities, to help tackle their loneliness. Her recent research explores the potential for virtual reality and robotic companions to address social isolation among older people.

But when Dr Barbosa Neves talked about her studies, she struggled to get her audiences to empathise with the older people whose lives she was documenting.

“I do communicate my research in a very scientific way, which is dry,” she says.

Dr Barbosa Neves has been asked why she doesn’t study children instead. She has been told older people make themselves lonely because they’re always cranky. Or that they can’t be lonely if they live in a nursing home.

She has even been told she looks too young to be concerned with older people.

“I feel like I have been failing because, especially in public communication, I just can’t create that empathy,” Dr Barbosa Neves says.

Extinctions, by Josephine Wilson, won the Miles Franklin award in 2017.

”If at the end people ask, ‘Why don’t you study children, they are the future,’ it means that nothing that I’ve said actually moved them in any way.”

And then one day Dr Barbosa Neves, a lover of fiction, read Extinctions , a Miles Franklin award-winning novel by Australian author Josephine Wilson.

The story of Fred Lothian, a retired academic engineer who moves into a retirement village, explores ageing, grief, loneliness and institutionalisation.

“I thought, ‘Wow, this is my research in a book but just written in a really beautiful way that I would never be able to accomplish as a scientific writer,’ ” Dr Barbosa Neves said.

In 1994 US sociologist Laurel Richardson coined the term crystallisation to describe how the arts – including storytelling, poetry writing, photography and performance – can be used to enrich research by deepening the understanding of a topic.

Miles Franklin award-winning author Josephine Wilson was thrilled by the request for help. Credit: James Brickwood

Dr Barbosa Neves was not aware of a writer and an academic trialling this approach, but decided to give it a go. “I just thought, why don’t I reach out to Josephine and see if she wants to help me communicate my research better.”

Wilson was thrilled by the “left-field” request. “Barbara’s work is really important and engages with the issues we’ve just heard in the royal commission into aged care. And so we really need ways of communicating that,” she says.

She listened to recordings of interviews with nursing home residents that Dr Barbosa Neves had conducted, and read her field notes and interview transcripts.

Wilson then wrote creative non-fiction narratives and a fantasy based around two of the participants – Gurney, whose life’s passion was aviation, and Patricia, who wished she could be happy like the trees.

In Gurney’s fantasy story, he leaves the nursing home in the cockpit of a Cessna Skyhawk. “No more bed baths. No more pureed food eaten under neon. No more cold tea and cheap biscuits. No more Bingo. Bingo!”

Wilson was inspired by Gurney: “The lively mind is something I really responded to in his voice, and the frustration. I think that ageing is such a terrible stereotype in our society.”

Dr Barbosa Neves hadn’t known what to expect, but was “blown away”.

“This exercise was really useful for me as a social scientist because Josephine captured things that I didn’t. I learnt a lot from the process about not only how to communicate my research in a way that hopefully can create some empathy, but also how to think about how we represent older people in the data and the stories that we tell.”

Dr Barbosa Neves describes their collaboration in the research paper Using Crystallisation to Understand Loneliness in Later Life , which was published in the scientific journal Qualitative Research last month.

From now on, when Dr Barbosa Neves speaks at conferences or community events, she will begin her presentation by reading aloud Gurney’s fantasy story or Patricia’s non-fiction creative narrative, instead of her usual PowerPoint. “I want to see how the audience responds to the stories.”

Start your day informed

Our Morning Edition newsletter is a curated guide to the most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Get it delivered to your inbox .

Most Viewed in National

Loneliness, Creativity, and Empathy

What’s the fundamental ambivalence in loneliness.

Posted October 3, 2023 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- Understanding Loneliness

- Find a therapist near me

This post is a review of This Exquisite Loneliness : What Loners, Outcasts, and the Misunderstood Can Teach Us About Creativity . By Richard Deming. Viking. 336 pp. $29.

To alleviate the emptiness and pain of loneliness, Richard Deming wandered through the streets of Boston, with a flask of Jack Daniels under his coat, asking strangers the time, not to start a conversation, but to prove, “at least provisionally,” that he did exist. At home, he dialed the phone, again and again, asking for “Paul,” and then drank himself into oblivion when he was told what he already knew: no one named Paul lived there.

The pattern was clear: a need for connection; retreat from a world in which no one seemed interested in him; drug abuse and blackout drinking. Since he has been sober, Deming has tried to understand an emotional disorder which, according to U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, has reached epidemic proportions.

In This Exquisite Loneliness , Deming, the director of Creative Writing at Yale University, draws on his life experiences, and those of six seminal artists and thinkers who wrestled with loneliness (along with family trauma , racism , sexism, and antisemitism) — psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, anthropologist and writer Zora Neale Hurston, philosopher Walter Benjamin, photographer Walker Evans, painter Egon Schiele, and Rod Serling, creator of The Twilight Zone — to identify the fundamental ambivalence inherent in the affliction: a desire for connection tethered to a belief in the certainty of rejection.

Throughout the book, Deming examines how heightened awareness can help loners turn outward, observe the lives of others, recognize the loneliness they feel, realize its ubiquity, empathize with them, and themselves. This Exquisite Loneliness is a beautifully written, informative, intimate, and insightful meditation about working with loneliness, a central and intrinsic feature of human existence, and not through it.

Klein, Deming reminds us, maintained that the seeds of loneliness emerge in early infancy, with a struggle between attachment and separation, and the memory of being a unified whole, “an illusion we chase for the rest of our lives.” Family relationships, Deming adds, can contribute to loneliness, but “we can’t necessarily say” it’s a cause or a cure. The self that emerges out of loneliness, moreover, is “who we are.”

Hurston’s stories, Deming acknowledges, don’t depict the vanquishing of loneliness by force of will. But their “cosmically personal yet turbulent beauty” gives readers a sense of what living with loneliness entails and provides the means for them to become “part of a larger whole, and a wider community.” If loneliness “is a story we tell ourselves,” revising that narrative invites us to create new ones.

Even before the Nazis came to power, Walter Benjamin was often “lonely, despondent, forsaken.” Avoiding cafes, Benjamin preferred communicating with friends in letters, because they permitted him to disavow isolation while remaining “distant, apart, isolated.” Divorced , on the run to escape death in a concentration camp, Benjamin committed suicide in 1940 in Spain. But, Deming points out, in the essays later published as Berlin Childhood Around 1900 , Benjamin demonstrated that “memory can be more than nostalgia ,” by serving as a reminder that “loneliness ebbs and flows.”

Photography, Deming maintains, allowed Walker Evans, whose empathy arose from his own loneliness and need for intimacy , to remain invisible while seeing soulmates who were also invisible. “Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop,” Evans recommended. “Die knowing something. You are not here long.” Evans’ now iconic Depression -era portraits, Deming writes, allow us to “feel alone together,” and be less subject to the gravitational force of loneliness. Somewhat similarly, the paintings of Egon Schiele, whose melancholy betrayed “a lonely vulnerability,” reveal “a genius for reading the pain of others,” and seemed to say, “I am here, and you are there. That’s what we share.” Perhaps, Deming writes, that is “where we begin.”

In “Where Is Everybody?”, the first episode of The Twilight Zone , the main character, dressed in a flight suit, wanders into a midwestern town and discovers that all the inhabitants have vanished. “Help me! Help me!” Mike cries, “Please, somebody’s looking at me.” And, indeed, an assembled audience and an audience in front of TV screens, is watching him. Later, the narrator will identify “the hunger for companionship” as a basic need, “the barrier to loneliness.” That barrier “can propel us to seek out others.” Especially when we recognize, along with Deming, that “belonging” is so close to “be longing.”

Glenn C. Altschuler, Ph.D. , is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies at Cornell University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that could derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face triggers with less reactivity and get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

This Exquisite Loneliness: What Loners, Outcasts, and the Misunderstood Can Teach Us About Creativity

Richard deming. viking, $29 (336p) isbn 978-0-593-49251-2.

Reviewed on: 08/14/2023

Genre: Nonfiction

Other - 1 pages - 978-0-593-49252-9

- Apple Books

- Barnes & Noble

Featured Nonfiction Reviews

ThinkWritten

How to Overcome Loneliness as a Writer

Writing can be a lonely and isolating passion – here are 10 ways to overcome loneliness and isolation as a writer.

We may receive a commission when you make a purchase from one of our links for products and services we recommend. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for support!

Sharing is caring!

Writing is a skill that requires creativity and technical know-how. It takes someone with a great deal of experience and exposure to write exceptionally well. Different writing styles require various skill sets. Hence, for the creative juices to flow, a calm and quiet environment is a writer’s best friend.

Finding a spot where one can focus and work undisturbed is like a healthy soil where imagination flourishes. At the same time, this ideal environment for writing can take a toll on your own mental and emotional well-being.

Lonely Writer Syndrome

Writing in itself is a solitary experience. An act accomplished only by you and your trusted ally – your computer. In order to meet target deadlines, and sometimes just because of utter concentration, being cooped up indoors for several days and nights is nothing unusual.

It is a sacrifice one must take in order to get all ideas, thoughts, transferred into paper. After accomplishing such a feat, there is a sense of accomplishment, happiness, or satisfaction that overwhelms a writer and motivates them to do it all over again if they have to.

Most people say all writers are introverts as a result. When in reality, even those who have gotten used to being alone and in the quiet for long periods of time still experience bouts of loneliness from time to time. There are various reasons a writer can feel depressed or lonely.

Perhaps it’s the inability to socialize with people who understood what being a writer entails, being unable to find the time to form a bond and establish a connection or other rationale. One thing’s clear though – there’s no need to dwell on the situation. It’s time to act and remember the points raised below to overcome loneliness as a writer.

Here’s How to Overcome Loneliness as a Writer:

1. Keep a Healthy Mindset

You are not alone. What you do has an impact on other people’s lives. You matter.

Living and writing is similar in certain ways. You get to breathe, eat, sleep and live life on your own standards. However, living your life with intention means connecting with other people, committing to a lifestyle within your means and creating meaningful relationships.

Living and writing is a journey you don’t do just for yourself. Your ultimate goal as a writer is for someone to read your work, learn from it, feel inspired by it, and eventually change their lives for the better.

If you get tired from doing what you do, rest. Allow your body to feel pain, exhaustion or weariness and when you are ready, stand up and do what you do best – write! Write your thoughts, feelings and use your emotions to inspire and motivate you.

2. Connect and Interact

There are others just like you who have the same goals. There are others who may not be like you but appreciates what you do and accepts you for who you are and what you aim to accomplish. The key is in finding these types of people and reaching out. But the first step is to be visible. You won’t be meeting anyone if you don’t make an effort.

Join writing groups – online or face-to-face. Reply to comments. Answer questions from newbies without expecting anything in return. Enlist in Webinars. Welcome out of the blue conference calls. Participate in group activities. Attend meetups. Do a video call with a friend. Create or support a cause. Engage in social media challenges.

There is an endless list of ways you can meet new people and expand your circle to combat loneliness as a writer. Don’t stop though after merely getting to know them. Make a consistent effort to get to know them more and establish a relationship.

Remember, building relationships is a two way street. You need to put in as much effort as the other person if you’re keen on maintaining a bond. Keep an honest and open communication.

3. Stay Toxic-Free

What do you do with the people who don’t do you any good? Let them go. That’s right. Value yourself. Appreciate yourself more. Steer away from people or activities that bring you sadness, anxiety or apprehension. Invest in those that make you feel empowered, energized and positive.

4. Get Outside

You are not bound to the chair you usually sat in or the room you’re stuck in. There are several places you can still write but still have a few people around to inspire you and encourage simple interactions.

Move about. Find a new coffee shop to hang out every week or so. Check out a new restaurant in the area. Bask in the sunlight as you write while lying down on your stomach on the green lawn in a park nearby.

What’s even better? Find a friend who can hang out with you without feeling pressured to carry on a conversation. Having someone physically present without any expectation of small talk is a great way to write and not be alone.

5. Give Back

Volunteer and spend your vacant time to help a non-profit organization. Offer dog walking. Serve meals at a homeless shelter. Spend time at a nursing home. Clean up trash in your community.

Knowing that you can do something, no matter how small of an act, to contribute and help others brings about a sense of accomplishment and pride.

6. Vary your Routine

Take a shower in the afternoon instead of in the morning. Wear something different. Dab a little powder on your face. Brush your hair. Look at the mirror and appreciate the change.

Sometimes just taking a few minutes break to take care of yourself and change things up from your normal routine does a lot with your outlook and helps you stay focused and motivated.

7. Get a Pet or a Plant

Get a plant, a dog, cat, bird or fish to take care of. Having something else to take care of other than yourself can alleviate feelings of loneliness. A pet or plant both offer companionship with minimal supervision.

8. Learn Something New

Give yourself something to aim for, something you would need to invest your time and energy in so that you funnel your focus and energy to doing something worthwhile versus dwelling on your emotions.

Learn a new language. Look up how to knit. Join a dance class. Sing to your heart’s content while discovering how to play a guitar. Try out a new recipe.

Focus on a new goal and be relentless in achieving it. Diverting your emotions to task-oriented goals can help you stay objective and can bring about self satisfaction from achieving it.

As a writer, you rely a lot on words to express what you think and how you feel. Channel your emotions differently by attempting to draw.

Feel free to use colors, pens, markers, or anything that can help draw out your emotions without feeling any pressure. It doesn’t matter what it looks like. Don’t focus on what you are making but rather on how the activity makes you feel. Grab a pen and paper and scribble away!

10. Play a Game

Install a new game on your phone or laptop or try a new online game. When you are starting to feel stuck, overwhelmed, and isolated, hold off on whatever you are doing and take a few minutes to play the game. Chat with some of the players. Take a break, enjoy and have fun.

Solitude vs Isolation

Studies conclude that the less time an individual spends with others, the more he puts himself at risk for feeling lonely and depressed. While writers are more exposed to this risk since they put in a lot of work while being alone most of the time, there are several ways you can fight it off.

There is a difference between working in solitude and working in isolation. One pertains to simply being alone per one’s own choosing while the latter implies a negative connotation of being alone without wanting or meaning to.

Some people can feel isolated when they are within a group of people who don’t appreciate them as they are and have interests that are not meeting their own.

In order to not feel this way, one must invest time and effort in being visible, interacting with random people and selecting which groups they are most likely to be accepted for who they are and what they do, participating in activities that allow them to become better versions of themselves and be comfortable in their own skin.

It’s important to partake in activities you don’t normally get involved in if it means bringing you in the open and letting you meet new people.

Keep a healthy mindset and take action. Instead of feeling unwanted and alone, take appropriate measures to change the situation you are in. There is always something you can do to take advantage of it and bring about the best version of yourself.

Allow yourself to feel, acknowledge and react to the current circumstances. You are not a robot. Your feelings are normal. However, what you do given how you feel weighs more. Don’t rush yourself into making a decision and plan how to live your life more purposely.

Do you have any tips for overcoming loneliness as a writer? Share your comments and how you deal with feelings of isolation in the comments section below!

Eric Pangburn is a freelance writer who shares his best tips with other writers here at ThinkWritten. When not writing, he enjoys coaching basketball and spending time with his family.

Similar Posts

10 Ways to Be a More Productive Writer

How to Make Time for Writing: 5 Ways to Find Time to Write Now

10 Reasons to Join a Writing Group

How to Build Your Own Writer’s Studio + 5 Beautiful Shed Kits You Will Love

How Long Does It Take To Write a Book?

How I Write Over 2,500+ Words a Day

Rachel Carson on Writing and the Loneliness of Creative Work

By maria popova.

Many of the titans of literature have left, alongside a body of work that models powerful writing, abiding advice on the craft that examines the source of that power. Unrivaled among them in the combination of cultural impact and sheer splendor of prose is Rachel Carson (May 27, 1907–April 14, 1964) — the Promethean writer and marine biologist whose 1962 masterwork of moral courage , Silent Spring , ignited the modern environmental movement.

Nowhere does Carson’s writing philosophy, of which she never published a formal statement, come to life more vividly than in the 1972 out-of-print treasure The House of Life: Rachel Carson at Work ( public library ) — a portrait of Carson, drawn from her previously unpublished papers and letters, by Paul Brooks, who worked closely with her as editor-in-chief at Houghton Mifflin during the publication of The Edge of the Sea and Silent Spring .

A generation after Virginia Woolf contemplated the relationship between loneliness and creativity , Carson echoed the lament at the heart of Hemingway’s Nobel Prize speech and observed upon accepting one of the many writing awards she won:

Writing is a lonely occupation at best. Of course there are stimulating and even happy associations with friends and colleagues, but during the actual work of creation the writer cuts himself off from all others and confronts his subject alone. He * moves into a realm where he has never been before — perhaps where no one has ever been. It is a lonely place, even a little frightening.

In a sentiment that calls to mind choreographer Martha Graham’s notion of the “divine dissatisfaction” driving all creative work, Carson adds:

No writer can stand still. He continues to create or he perishes. Each task completed carries its own obligation to go on to something new.

Like Einstein , Carson made an unwearying effort to answer as much as she could of the voluminous fan mail she received, but her most touching correspondence is with a young aspiring writer by the name of Beverly Knecht — a blind girl hospitalized with what would turn out to be a terminal illness. After devouring The Edge of the Sea on Talking Books — an early audiobook program initiated by the Library of Congress and the American Foundation for the Blind in the 1930s — Beverly sent Carson a letter of affectionate appreciation. Carson wrote back:

I hope you can realize the very deep and lasting pleasure your letter gave me. In my writing, I have always tried not to lean on illustrations (of which most of my books have had few) but to create in words an image that would register clearly on the eyes of the mind. You make me feel I may have succeeded.

In a letter to another young woman with whom Carson felt a deep kinship of spirit, she returns to the subject of loneliness as a necessary condition for creative work:

You are wise enough to understand that being “a little lonely” is not a bad thing. A writer’s occupation is one of the loneliest in the world, even if the loneliness is only an inner solitude and isolation, for that he must have at times if he is to be truly creative. And so I believe only the person who knows and is not afraid of loneliness should aspire to be a writer. But there are also rewards that are rich and peculiarly satisfying.

More than anything, however, Carson held up work ethic and integrity of vision as the most vital requirements for being a successful writer. In a sentiment which James Baldwin would come to echo decades later in his thoughts on the relationship between talent and discipline , and which Hemingway had articulated in his advice on the art of revision , she tells her young correspondent:

Given the initial talent … writing is largely a matter of application and hard work, of writing and rewriting endlessly, until you are satisfied that you have said what you want to say as clearly and simply as possible. For me, that usually means many, many revisions.

Carson adds a thought that parallels my own animating ethos since the inception of The Marginalian [ as Brain Pickings ] more than a decade ago:

If you write what you yourself sincerely think and feel and are interested in, the chances are very high that you will interest other people as well.

In previously contemplating what constitutes great nonfiction, I placed writers in a hierarchy of explainers, elucidators, and enchanters , the latter class being exceedingly rare and exceedingly rewarding to read. Carson was the twentieth century’s science-enchanter par excellence, whose writing was governed by her belief in “the magic combination of factual knowledge and deeply felt emotional response.” Today’s finest science writers — authors like Oliver Sacks , Janna Levin , Alan Lightman , Diane Ackerman , and James Gleick , who convey the inherent poetry of the universe in uncommonly enchanting prose — have some of Carson’s blood coursing through the pulse-beat of their books.

Carson, who made an art of illuminating nature beyond scientific fact , resented the notion that science is somehow separate from life. Our only means of upending the conventions and belief systems we resent is by modeling superior alternatives, and that is precisely what Carson did with her 1937 masterpiece Undersea , which pioneered a new way of writing about science with a strong lyrical sensibility, revealing the native poetry of nature. The piece became the seed for Carson’s 1951 bestseller The Sea Around Us , which won her the National Book Award. In her acceptance speech, she took head on the obtuse convention — one enduring to this day — that writing about science belongs in a special compartment of literature:

The materials of science are the materials of life itself. Science is part of the reality of living; it is the what, the how, and the why of everything in our experience. It is impossible to understand man without understanding his environment and the forces that have molded him physically and mentally. The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history or fiction; it seems to me, then, that there can be no separate literature of science.

With an eye to the deliberate stylistic choices she made in how she wrote about the sea — choices highly unusual for their time, which steered nonfiction toward an epoch-making new aesthetic direction — she adds:

My own guiding purpose was to portray the subject of my sea profile with fidelity and understanding. All else was secondary. I did not stop to consider whether I was doing it scientifically or poetically; I was writing as the subject demanded. The winds, the sea, and the moving tides are what they are. If there is wonder and beauty and majesty in them, science will discover these qualities. If they are not there, science cannot create them. If there is poetry in my book about the sea, it is not because I deliberately put it there, but because no one could write truthfully about the sea and leave out the poetry.

She took up the subject again in a letter written a few years after the publication of The Sea Around Us :

The writer must never attempt to impose himself upon his subject. He must not try to mold it according to what he believes his readers or editors want to read. His initial task is to come to know his subject intimately, to understand its every aspect, to let it fill his mind. Then at some turning point the subject takes command and the true act of creation begins… The discipline of the writer is to learn to be still and listen to what his subject has to tell him.

Later, during the writing of Silent Spring , Carson would reflect on the writer’s ultimate task:

The heart of it is something very complex, that has to do with ideas of destiny, and with an almost inexpressible feeling that I am merely an instrument through which something has happened — that I’ve had little to do with it myself.

She would then tell her beloved , Dorothy Freeman, in the same letter:

As for the loneliness — you can never fully know how much your love and companionship have eased that.

During her final revisions of Silent Spring , as she navigated the anguishing late stages of metastatic breast cancer, Carson addressed a friend’s concern that the book’s focus on pesticides would eclipse the splendor of the planet she was trying to protect. Acknowledging for the first and only time the dual motive power of moral outrage and fidelity to beauty that had animated her as she composed her masterpiece, she wrote:

I myself never thought the ugly facts would dominate, and I hope they don’t. The beauty of the living world I was trying to save has always been uppermost in my mind — that, and anger at the senseless, brutish things that were being done. I have felt bound by a solemn obligation to do what I could — if I didn’t at least try I could never again be happy in nature. But now I can believe I have at least helped a little. It would be unrealistic to believe that one book could bring a complete change.

Carson died eighteen months after Silent Spring was published and never lived to see herself proven wrong as it catalyzed the modern environmental movement by mobilizing the public conscience and effecting major government reform in environmental policy — nothing less than “a complete change” in culture and consciousness, proof that unrelenting idealism is in the end the mightiest realism.

Complement the thoroughly wonderful The House of Life with Carson’s prescient protest against the government’s assault on science and nature and her almost unbearably touching farewell to her beloved , then revisit other timeless advice on writing from Ernest Hemingway , William Faulkner , Susan Sontag , James Baldwin , Umberto Eco , Friedrich Nietzsche , and Ursula K. Le Guin .

UPDATE: For more on Carson, her epoch-making cultural contribution, and her unusual private life, she is the crowning figure in my book Figuring .

— Published August 28, 2017 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2017/08/28/rachel-carson-house-of-life-writing-loneliness/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books creativity culture letters out of print psychology rachel carson science writing, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

Get the Reddit app

Discussions about the writing craft.

How do I create a feeling of loneliness?

I am currently writing a story where the main character is trying to survive in the aftermath of the apocalypse. The idea I had was that she can't speak and she has been on her own for about a year. I wanted to expand on her personal feelings; loneliness, fear and distrust of others, before I introduced the side characters she will learn to deal with. However, when I read what I have written, I don't get a lonely vibe. Instead it is drier than Arrakis. Do you guys have any suggestions on how to best create that feeling of being alone?

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Lonely? 7 Ways to Stay Sane When Working by Yourself

Tom Meitner

When I started writing full-time in the spring of 2008, I was living alone in an apartment building. One month after I started, I graduated college.

At the time, I didn’t have a girlfriend. And because I was starting out as a writer with no savings, I didn’t have a lot of spending money. While my friends were all going out to bars, I stayed home to save money.

On the one hand, this was an exciting time in my life. I was working for myself, starting to make money, and had complete control over my schedule every single day.

On the other hand, it got lonely fast. With no office to go to, no school, no social life, no love life, there was no actual reason to leave my apartment beyond grocery shopping and church.

It wasn’t uncommon for me to go to church on Sunday morning, come home to watch the Green Bay Packers play football, and suddenly find myself on Tuesday afternoon realizing that I hadn’t seen or interacted with another human being in two whole days.

Many Tuesday evenings, I finished eating a home-cooked dinner and then ventured out to Target. I didn’t have anything to buy, nor did I have any money to spend, but I would just wander the aisles, smiling at people and enjoying being out among the living.

Just writing that out makes me sad.

The writing life is a lonely one. If you are working for yourself, whether that’s in a freelance capacity or through publishing books, you are likely finding yourself spending long hours at your desk at home. And if you don’t have a family that lives at home with you, that lack of interaction can really grate on you.

Humans Need Interaction

7 tips to combat loneliness, mix and match.

There have been plenty of studies that show how human beings wither away when they don’t have interaction with other human beings . Yes, it’s funny and cool to say that you don’t need anybody except your dog, but that’s just not true. Everyone needs to be around people at some point. Working for yourself makes that incredibly difficult.

And of course, in the age of COVID-19, this problem is even more pronounced. You may be struggling with loneliness because you never intended to work for (and by) yourself.

Fortunately, not all is lost. There are ways of handling this problem, and you don’t need to be a social person to do it.

Tip 1: If you have a family at home, spend time with them

When you work from home, the boundaries around your work day are not so clear. It’s very easy to let work creep into the rest of your day.

You might take a few emails at the dinner table. Or you might be playing with your kids and get a Slack notification. Or you might simply push off some of your work to the evening, when you should be spending quality time with your spouse.

If you have a family at home, then the easiest way to deal with loneliness is by spending intentional time with them. That means putting away your devices and being fully engaged with them. That’s the quickest way to mental health.

At the end of your work day, establish some kind of ritual to switch off your work brain and get yourself in the mindset of someone who is coming home for the day. If you must work later in the day, that’s fine, but carve out time elsewhere to completely disengage from your work.

The best part about this solution, if you do have a family at home, is that it doesn’t require you to be an extrovert. Many of us writers are introverts by nature, but we’re comfortable around our own families. This gets you that human interaction without going out on a limb.

Tip 2: Work away from home one day a week

Depending on where you live, this can be difficult. But it is a solution that should be considered if the circumstances apply.

Before COVID-19 shut everything down, I spent one work day a week working somewhere other than my home office. It might be a coffee shop, or a library, or even just going to the mall. I grab my laptop and go work among the living for a little while .

I never intentionally interacted with anybody. I didn’t force myself to make any new friends. In fact, I kept to myself more than I do at home.

But just that feeling of being around other people helped. It gave me energy, and I could feel the difference it made in my mental and emotional health. Working from home as a writer can often make you feel disconnected from the world. Working among others in the world is a simple way to re-establish that connection.

Tip 3: Get involved in local writer groups

At this point, many people think of the internet as pushing people further apart from each other. Because we can all Zoom now, it feels as though we’re more disconnected than ever.

However, the internet is also a tool that can bring people together. Pretty much anywhere you live, there is probably a writing group available to you. This is true especially if you work in fiction. Writer groups exist almost everywhere, and they offer a way for you to get together with other like-minded writers and provide feedback and encouragement for each other.

You don’t write fiction? You actually have more options available to you. You are free to interact with other businesses, not just writers. That means you can go to your Chamber of Commerce or any number of local business groups. Often, when available, they meet at bars and restaurants over food and drinks to discuss business and network with each other.

This is easily the most intimidating solution that you can come up with for writer loneliness. But for many, it is a very effective solution. Plus, by networking with other writers and businesses, you give yourself a chance to expand your business overtime.

I don’t do this one. I’ve tried it in the past and I just don’t care for it. But for those who are comfortable with it, it works extremely well.

Tip 4: Join a group outside of your writing practice

Getting involved with other people in different ways can also provide you with companionship. For me, that means being involved in my church. But it can be anything. Church gives me the added benefit of getting out of my house once or twice a week. But maybe there’s another group that you can get together with. Look at your interests and see if there are groups that reflect them.

Tip 5: Get a pet

Not the same as human interaction, but it softens the loneliness.

Tip 6: Go wander around the store

I’m not saying it’s the best solution, but in a pinch, just going down to a store or mall and wandering the aisles can give you just enough of a boost to get through the week. There’s a reason I kept doing that.

Tip 7: Intentionally connect with other loved ones

Another easy solution is simply to look at the rest of your life and find ways to connect in person with the people that you care about. Just because your work life is lonely doesn’t mean your social life has to be lonely too. Reach out to friends and family that you haven’t talked to in a while and see if they want to get together. It can be more effective than you think.

The most important lesson to learn from this is that opportunity is everywhere if you look for it. Maybe there is a solution that works for you that I didn’t talk about here. Play around with it.

You’re not married to any solution. Try some things out and see what works for you, and you can stave off the loneliness that harms you mentally and emotionally—and can harm your writing career as well.

Join the ProWritingAid community for our weekly webinars

Each month, we host events ourselves and in collaboration with our partners, all aimed at helping you become a better writer.

Find out more and sign up for our upcoming events here..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Tom Meitner spends pretty much his entire day writing—and loves it. He is a freelance copywriter, self-published author, and fiction ghostwriter. You can learn more about Tom and his work at his website TomMeitner.com. When he's not glued to the screen of his Chromebook, Tom is spending time with his wife and kids in Wisconsin, likely eating some form of cheese.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

- Relationships

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

This Exquisite Loneliness: What Loners, Outcasts, and the Misunderstood Can Teach Us About Creativity Hardcover – October 3, 2023

- Print length 336 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Viking

- Publication date October 3, 2023

- Dimensions 5.7 x 1.11 x 8.52 inches

- ISBN-10 059349251X

- ISBN-13 978-0593492512

- See all details

From the Publisher

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Viking (October 3, 2023)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 336 pages

- ISBN-10 : 059349251X

- ISBN-13 : 978-0593492512

- Item Weight : 14.9 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.7 x 1.11 x 8.52 inches

- #681 in Creativity (Books)

- #824 in Author Biographies

- #1,026 in Interpersonal Relations (Books)

About the author

Richard deming.

Richard Deming's first collection of poems, LET'S NOT CALL IT CONSEQUENCE (Shearsman Books, 2008), won the Norma Farber Award from the Poetry Society of America and was a finalist for the Connecticut Book Award. He is also the author of Listening on All Sides: Towards an Emersonian Ethics of Reading. In 2012, he was awarded the Berlin Prize by the American Academy in Berlin. He is currently Director of Creative Writing at Yale University.

Customer reviews

| 1 star | 0% |

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Revisiting the Loneliness of the Long-Distance Writer

Cynthia D. Bertelsen learns to embrace the isolation of the writing life

I REMEMBER the exact moment that I decided to become a writer, the year I was in second grade. Snuggling deep into the coffee-brown overstuffed couch my mom had hauled home from a secondhand shop, I opened one of the two Bobbsey Twins books my grandmother had given me for Christmas and read, with snow falling outside the picture window of the living room. Two hours later, I let the book fall to the floor. Caught up in the world of Bert and Nan and Flossie and Freddie, I just lay there and decided I wanted to write stories like Laura Lee Hope did, to enthrall people with words.

Laura Lee Hope, I later learned, was not one person, but several. Despite that brief disillusionment, I still nurtured the idea of becoming a writer.

It’s been a long journey since that snowy day on the couch—and a lonely one, in which images of the romantic life of prolific hermit writers like J.D. Salinger have bumped up against society’s idealizations of both extroverts and submissive women.

Sure, most writers say writing’s a solitary business. And it is: you sit alone with pen in hand or in front of the computer for long stretches. There’s some consolation in reading stories about writing, and everyone from Anne Lamott and Stephen King and Annie Dillard to Eudora Welty and Margaret Atwood has contributed to the canon of reflections about the writing life. Wright Morris even published a book with the catchy title of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Writer (1995).

But while people talk about the physical isolation, I think the emotional isolation might be even more overwhelming. I think one reason why I feel a profound sense of loneliness as a writer is that most of the people — family, chiefly — surrounding me offer little emotional support.

In fact, they often completely ignore the writing part of me. I get the message that if I talk about my art, I’m seen as a braggart. For me, getting an article published now and then is simply the same sort of thing as, say, taking a business trip to Germany or India (which some of my relatives do). Just part of the job, the process.

To counteract the demons of isolation and solitude, I tried immersing myself in various community organizations. One of these was a group devoted to preserving a magnificent cookery-book collection housed in the university library near me. I liked the work, and over a period of years I took on leadership positions. But weekly and monthly meetings demanded a lot of my time, and squabbles between committee members drained my energy, and even editing the newsletter of this organization became a trial because so few contributors stepped forward. Surrounded by living, breathing warm bodies, I found myself still alone, physically and spiritually depleted, drowning in the world.

And—more to the point—not writing.

One morning, after a particularly fractious meeting at the university library, I knew the time had come. I resigned that afternoon.

To do the real work of writing, I realized, requires a form of solitude, not unlike that of the anchorite, living in seclusion for religious reasons. Julian of Norwich served as my role model. Walled into a cell in a convent in Norwich in the late fourteenth century, away from the sinuous clamorings of the world, she wrote Revelations of Divine Love , the first known English book by a woman. She said “No” to the world.

And that is what I learned to do as well.

Yes, to write is to be alone, even lonely. The Internet and social media help in driving away some of the physical and mental isolation, bringing other living, writerly voices into my life. But the danger of over-involvement is there as well. What Ernest Hemingway stressed in his 1954 Nobel acceptance speech remains true:

Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day .

Indeed, there’s something of the eternal about writing, the words remaining long after the flesh is dust.

And so, for now, I accept the loneliness, as it’s the price I must pay to do what I do. These days, I often think of Norman Mailer’s comment: “Writers don’t have lifestyles. They sit in little rooms and write.”

And they say “No” to the world, to protect the writing.

Creative Writing Workshop

Works written by students during the Creative Writing Studies.

Loneliness and emptiness

No comments:, post a comment.

Yale Alumni Logo

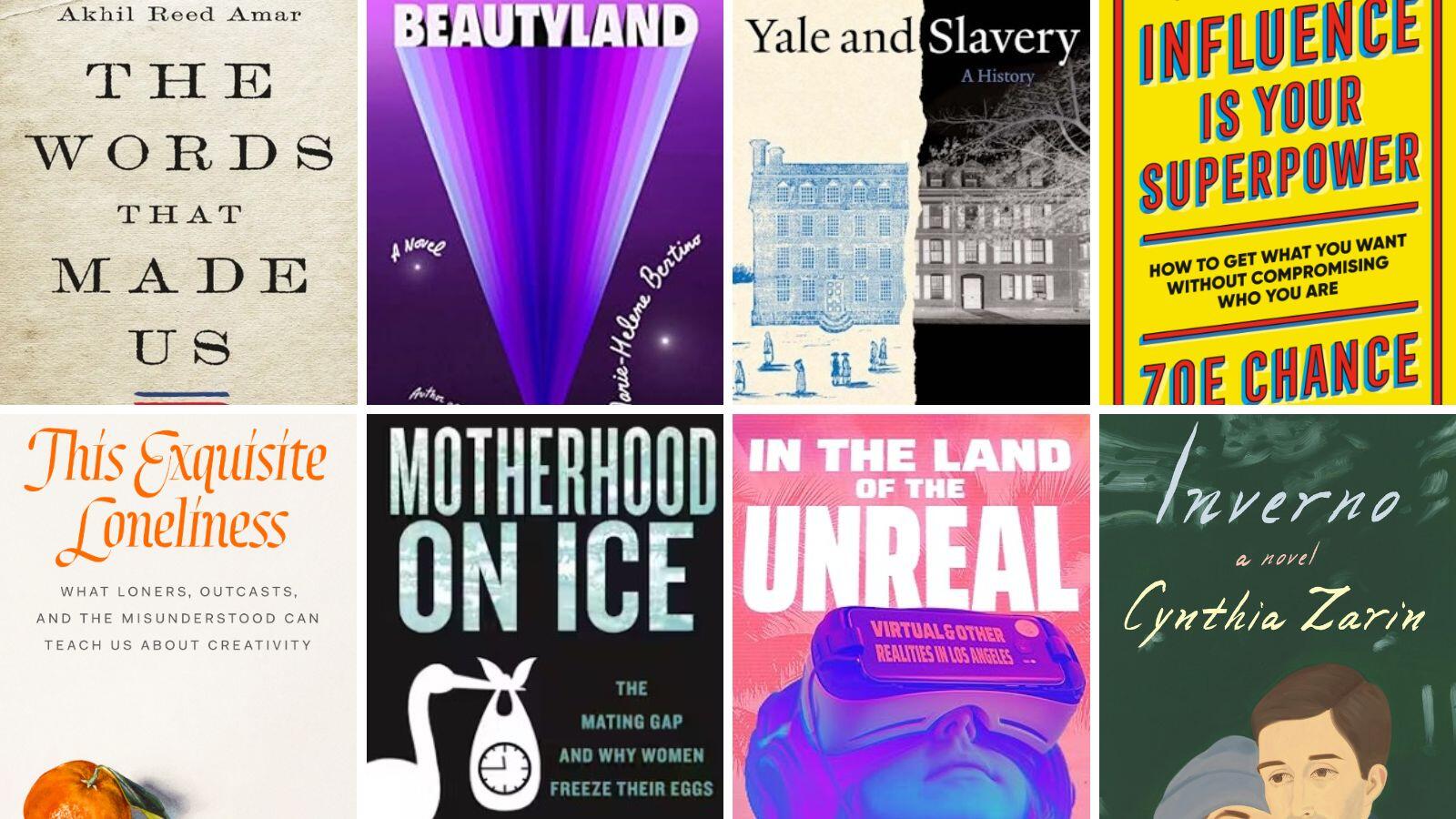

Yale Alumni Association Summer 2024 Reading List

As the weather heats up in New Haven, we’re planning to head to the beach or stay inside in the air conditioning with a good book. Join the YAA’s reading journey with our summer reading list featuring recent publications from members of the esteemed Yale faculty, which includes novels, how to use your influence superpower, and learning about the context of loneliness and what people have done to navigate it.

- The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840 by Akhil Reed Amar, Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science

- Beautyland: A Novel by Marie-Helene Bertino, Ritvo-Slifka Writer-in-Residence and Lecturer in English

- Yale and Slavery: A History by David Blight, Sterling Professor of History and African American Studies [Note: Please also see the companion website .]

- Influence is Your Superpower: How to Get What You Want Without Compromising Who You Are by Zoe Chance, Senior Lecturer in Management

- This Exquisite Loneliness: What Loners, Outcasts, and the Misunderstood Can Teach Us about Creativity by Richard Deming, Senior Lecturer in English, Director of Creative Writing

- Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs by Marcia Inhorn, William K. Lanman Jr. Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs

- In the Land of the Unreal: Virtual and Other Realities in Los Angeles by Lisa Messeri, Assistant Professor of Anthropology

- Inverno: A Novel by Cynthia Zarin, Senior Lecturer in English, Writing Concentration Coordinator

Have more suggestions for this list? Tag us with your summer reading finds #YaleAlumni or @YaleAlumni on social!

You May Also Be Interested In

Kathryn Guarini ’94, former CIO of IBM, to teach at Yale Engineering this fall

Jennifer Taylor ’10 JD looks back on time at Liman Center

Jeffrey Brock ’92 reappointed dean of Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science

Garrett West ’18 JD to join Yale Law School faculty

Stellar cast, captivating writing combine for brilliant 'Little Bear Ridge Road'

This is a deeply beautiful piece of writing, bleakly funny, poetic in its plainness, aching in its intense empathy for the characters, brought to life by laurie metcalf and micah stock at steppenwolf theatre..

Sarah (Laurie Metcalf) and her estranged nephew Ethan (Micah Stock) attempt to find some connection in Steppenwolf Theatre’s world premiere production of “Little Bear Ridge Road” by Samuel D. Hunter, directed by Joe Mantello.

Michael Brosilow

The notion of a Samuel D. Hunter play starting during the COVID-19 pandemic seems natural, since the MacArthur genius grant winner has previously pondered people with proclivities towards social isolation. His most famous character to date, in his play “The Whale,” was a man whose unmanageable obesity served in part to give him reason for never leaving his chair. Brendan Fraser earned a best actor Oscar for the film version.

When we meet the two main characters of Hunter’s newest work “Little Bear Ridge Road” — now receiving its world premiere at Steppenwolf Theatre — we know they’re not the most, shall we say, people-friendly people. Sarah (the always welcome, unsurprisingly magnificent Steppenwolf ensemble member Laurie Metcalf) has moved a half-hour away from the nearest city — which would be Moscow, Idaho (population about 25,000) — because she says, even fewer people “suits me better.” Ethan (the less-familiar and shockingly terrific Micah Stock) seems to assume people disapprove of him, perhaps a remnant of growing up gay in religious territory. He’s surprised to hear that Sarah doesn’t have an issue when he mentions his sexuality.

Ethan has driven from Seattle to Idaho upon the death of his father, an incorrigible meth addict and Sarah’s brother. Sarah notices that Ethan seems to have all his belongings in his barely running car.

But there’s a sense of hope, if that’s what you can call a glimmer of mutual connection, that this mostly estranged aunt and nephew can find some comfort in each other. By the end of the first scene, two things have happened. Sarah has invited Ethan to stay in her guest room while he arranges to sell his father’s house, and Ethan has removed his face mask.

“There you are,” Sarah says.

There seems a possibility of reconciliation, shared mourning. Maybe, eventually, they’ll even smile.

But this is a Hunter play, and as such almost inexorably an exploration of self-loathing, loneliness, inertia, unresolvable trauma, existential perplexity. People are like deep, bottomless holes of unfillable, unspeakable emotional need. That hole metaphor is emphasized here both by references to astrophysics and by the round circle of carpet that forms the base of Scott Pask’s ultra-minimal set design, which contains only that carpeting, a couch and a back wall that’s lit up at times to suggest the vastness of space, very visible in this part of Idaho where it’s a half-hour drive to the nearest store.

Ensemble member Laurie Metcalf and Micah Stock star in Samuel D. Hunter’s “Little Bear Ridge Road” at Steppenwolf Theatre.

Meaningful conversation between the two is constantly challenging, halting. They watch TV hoping to find something they can talk about and, tellingly, end up watching a show they both mostly hate. But it’s easier than anything personal. Sarah keeps the biggest news in her life secret.

In one of the play’s many amusing moments — the production’s ability to find humor amid human awkwardness is endless — Stock squirms with his entire body when Sarah queries Ethan about his love life. Asked why he doesn’t write even though he went to school for fiction, Ethan’s general answer is, “I don’t know,” while his more specific response is that he writes about aspects of himself, but “I realized I didn’t like my main characters.”

The surprising honesty of that admission makes it funny, even though it isn’t. But it is.

When the characters do start to become more open with each other, it only gets more complicated. The entire play captures the intense contradiction of how people need to rely on others, yet either resent it or lose themselves in dependence, or both.

John Drea (left) and Micah Stock co-star in “Little Bear Ridge Road” at Steppenwolf Theatre.

- Season 3 of ‘The Bear’ to debut one day earlier than previously announced

This is a deeply beautiful piece of writing, bleakly funny, poetic in its plainness, aching in its intense empathy for the characters, brought to brilliant life, and eventually explosive drama, by Metcalf and Stock under the precise, elegant direction of Joe Mantello.

It’s not perfect. The title of the play remains puzzling, and, although it may have personal meaning to Hunter (it relates to his own father’s home and where he drafted the play), it’s not evocative on its own. One of two supporting characters — James (an appealing John Drea), a love interest for Ethan — feels fundamentally over-idealized, a type of hope personified in a play that isn’t stylized enough for such a symbol.

But throughout, Metcalf and Stock provide a constant source of fascination, so exact in their differentiation between what they know they should say and what they do say, so dour and yet so comic simultaneously. Stock is such a revelation here, wearing Ethan’s raw pain on the outside, so exposed and yet also so invulnerable.

I don’t remember the last time I cared about characters this much.

- Open access

- Published: 24 June 2024

The rise and fall of a social support intervention feasibility trial targeting loneliness in patients with cardiac disease - lessons learned and future perspectives

- Mitti Blakoe 1 ,

- Cathrine S. Olesen 1 ,

- Anne Vinggaard Christensen 1 ,

- Pernille Palm 1 ,

- Ida Elisabeth Hoejskov 1 &

- Selina Kikkenborg Berg 1 , 2

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 423 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

83 Accesses

Metrics details

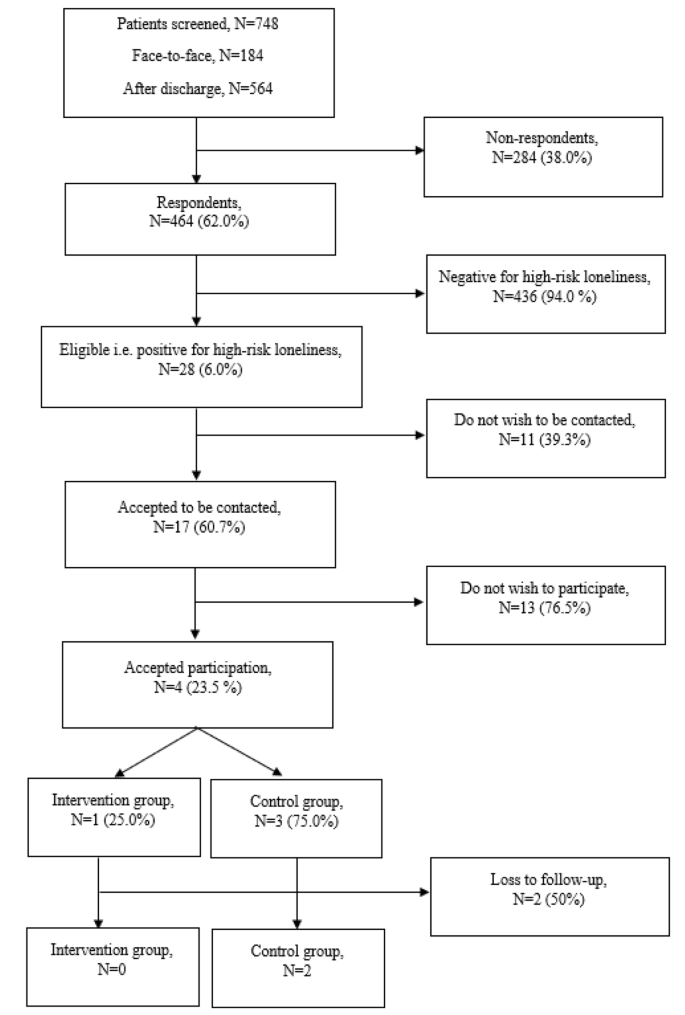

One of the psychosocial factors recognized for its positive impact on health outcomes among patients with heart disease, is social support provided by network members. However, an increasing number of patients report to experience loneliness. This study addresses the gap in research on the feasibility of an individually structured social support intervention targeting patients treated for cardiac disease who experience loneliness.

A feasibility trial of a 6-month social support intervention targeted patients treated for cardiac disease who experienced loneliness. The intervention involved providing the patient with an informal caregiver, either a person from the patient’s social network or a peer, in the long-term rehabilitation phase. Furthermore, the intervention included nurse consultations and motivational text messages. Feasibility was assessed in terms of acceptability and adherence.

During October 2022-July 2023, n = 464 patients were screened for loneliness and 28 (6.0%) screened positive of which 17 (60.7%) accepted to be contacted and receive additional information about the social support intervention. Of these, 2 (11.8%) accepted participation. The low recruitment rate did not meet the predetermined acceptability criterion of 25%.

This individually structured social support intervention targeting patients treated for cardiac disease who experience loneliness was non-feasible. The study highlights the complexities of engaging lonely patients in a social support intervention program and contributes with valuable insights for future research aiming to develop effective social support interventions tailored to the needs of cardiac patients who experience loneliness.

Trial registration

The trial is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05503810) 18.08.2022.

Peer Review reports