Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

LEARNING DISABILITY : A CASE STUDY

The present investigation was carried out on a girl name Harshita who has been identified with learning disability. She is presently studying at ‘Udaan’ a school for the special children in Shimla. The girl was brought to this special school from the normal school where she was studying earlier when the teachers and parents found it difficult to teach the child with other normal children. The learning disability the child faces is in executive functioning i.e. she forgets what she has memorized. When I met her I was taken away by her sweet and innocent ways. She is attentive and responsible but the only problem is that she forgets within minutes of having learnt something. Key words : learning disability, executive functioning, remedial teaching

Related Papers

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics

Sunil Karande , Madhuri Kulkarni

International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science Applications and Management Studies

Monika Thapliyal

This paper reviews the research work on 'learning disability' in India. It studies the social and educational challenges for learning disabled, and details research in India, concerning the aspects of diagnosis, assessment, and measures for improvement. The paper critically examines the development in their teaching-learning process, over the years. It highlights the role of special educator in their education and explores the impact of technology and specific teaching-aids in the education of learners with learning disability. The later part of the paper, throws light on the government policies for learning disabled and attempts to interpolate their proposed effect in their learning. It concludes with possible solutions, learner progress, based on the recommendations from detailed analysis of the available literature.

International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics

Shipra Singh

Background: Specific learning disability (SLD) is an important cause of academic underachievement among children, which often goes unrecognized, due to lack of awareness and resources in the community. Not much identifiable data is available such children, more so in Indian context. The objectives of the study were to study the demographic profile, risk factors, co-morbidities and referral patterns in children with specific learning disability.Methods: The study has a descriptive design. Children diagnosed with SLD over a 5 years’ period were included, total being 2015. The data was collected using a semi-structured proforma, (based on the aspects covered during child’s comprehensive assessment at the time of visit), which included socio-demographic aspects, perinatal and childhood details, scholastic and referral details, and comorbid psychiatric disorders.Results: Majority of the children were from English medium schools, in 8-12 years’ age group, with a considerable delay in seek...

Journal of Postgraduate Medicine

Sunil Karande

Fernando Raimundo Macamo

IJIP Journal

The cardinal object of the present study was to investigate the learning disability among 10 th students. The present study consisted sample of 60 students subjects (30 male students and 30 female students studying in 10th class), selected through random sampling technique from Balasore District (Odisha). Data was collected with the help of learning disability scale developed by Farzan, Asharaf and Najma Najma (university of Panjab) in 2014. For data analysis and hypothesis testing Mean, SD, and t test was applied. Results revealed that there is significant difference between learning disability of Boys and Girls students. That means boys showing more learning disability than girls. And there is no significant difference between learning disability of rural and urban students. A learning disability is a neurological disorder. In simple terms, a learning disability results from a difference in the way a person's brain is "wired." Children with learning disabilities are smarter than their peers. But they may have difficulty in reading, writing, spelling, and reasoning, recalling and/or organizing information if left to figure things out by them or if taught in conventional ways. A learning disability can't be cured or fixed; it is a lifelong issue. With the right support and intervention, children with learning disabilities can succeed in school and go on to successful, often distinguished careers later in life. Parents can help children with learning disabilities achieve such success by encouraging their strengths, knowing their weaknesses, understanding the educational system, working with professionals and learning about strategies for dealing with specific difficulties. Facts about learning disabilities Fifteen percent of the U.S. population, or one in seven Americans, has some type of learning disability, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Indian Pediatrics

Rukhshana Sholapurwala

samriti sharma

Baig M U N T A J E E B Ali

The present article deals with the important factors related to learning disability such as the academic characteristics of learning disability, how learning disability can be identified in an early stage and remedial measures for learning disability. It tries to give an insight into various aspects of learning disability in children that will be of help in designing the tools and administering them properly.

Iconic Research and Engineering Journals

IRE Journals

This article explains how learning disability affect on one's ability to know or use spoken affects on one's ability to know or use spoken or communication, do mathematical calculations, coordinate movements or direct attention learning disabilities are ignored, unnoticed and unanswered such children's needs are not met in regular classes. They needed special attention in classrooms. Learning disability is a big challenge for student in learning environment. The teacher's role is very important for identifying the learning disability. Some common causes and symptoms are there for children with learning disability. The classroom and teacher leads to main important role in identification and to overcome their disabilities.

RELATED PAPERS

Claudio Piechnik

Luis G Sanchez Giraldo

Salamat Ali

World News of Natural Sciences

rita rostika

Mohammed Gamal

Augmented Cognition

Martha Crosby

Hyomen Kagaku

Daisuke Fujita

Universitas Muhammadiyah Metrog

nida hasanati

Nurmiyati Nurmiyati

Rosita Diana

Mirjana Damjenic

Transport Problems

Mihaela Popa

Daniel Einarson

European review for medical and pharmacological sciences

Revista De La Educacion Superior

Lorenza Villa Lever

Turkish Journal of Pediatrics

Tanil Kendirli

Resumos do...

Rodrigo Luiz Ximenes

Dorota Jesionek-kupnicka

学校原版美国埃默里大学毕业证 emory学位证书毕业文凭证书Offer原版一模一样

Holodilʹnaâ Tehnika i Tehnologiâ

Serhiy Serbin

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Psychol Med

- v.45(3); 2023 May

- PMC10159575

Prevalence of Specific Learning Disorders (SLD) Among Children in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Liss maria scaria.

1 Child Development Centre, Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India.

Deepa Bhaskaran

Babu george, background:.

Specific learning disorders (SLD) comprise varied conditions with ongoing problems in one of the three areas of educational skills–reading, writing, and arithmetic–which are essential for the learning process. There is a dearth of systematic reviews focused exclusively on the prevalence of SLD in India. Hence, this study was done to estimate the prevalence of SLD in Indian children.

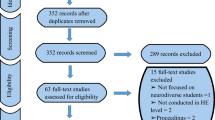

A systematic search of electronic databases of MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL was conducted. Two authors independently assessed the eligibility of the full-text articles. The third author reassessed all selected studies. A standardized data extraction form was developed and piloted. The pooled prevalence of SLDs was estimated from the reported prevalence of eligible studies, using the random-effects model.

Six studies of the systematic review included the diagnostic screening of 8133 children. The random-effects meta-analysis showed that the overall pooled prevalence of SLD in India was 8% (95% CI = 4–11). The tools used to diagnose SLD in the studies were the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS)-SLD index and the Grade Level Assessment Device (GLAD).

Conclusions:

Nearly 8% of children up to 19 years have SLD. There are only a few high-quality, methodologically sound, population-based epidemiological studies on this topic. There is a pressing need to have large population-based surveys in India, using appropriate screening and diagnostic tools. Constructing standardized assessment tools, keeping in view the diversity of Indian culture, is also necessary.

Specific learning disorders (SLD), often referred to as learning disability, is a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) and refers to ongoing problems in one of the three basic skills–reading, writing, and arithmetic–which are the essential requisites for the learning process. 1 These difficulties, namely dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, and developmental aphasia, 2 can occur alone or in different combinations ranging from mild to severe difficulties. 3

Dyslexia, the reading disability, is the most common condition, accounting for about 80% of all SLDs. 4 Dysgraphia is generally characterized by distorted writing despite thorough instructions. The significant characteristic of dyscalculia is the problems in understanding or learning mathematical calculations. About 30% of children with SLD have behavioral and emotional problems, and they are at increased risk for hyperactivity and other comorbidities. 5

Although SLD cannot be cured, there are interventions for underlying conditions so that children with SLD can adapt, accomplish academic achievements, and live productive and fulfilling lives. 3 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) estimates the prevalence of all learning disorders (including impairment in writing, reading, and mathematics) to be about 5% to 15% worldwide. 6 The lifetime prevalence of learning disability among children in the USA was 9.7%. 7 In India, the prevalence of SLD is reported to vary from 3% to 10%. 8

In India, although SLD is included as one of the disabilities according to the Rights of Persons with Disability Act of 2016, the screening and diagnosis of SLD are complicated. Various tools are used for the assessment, with their own merits and demerits. Some tools like the AIIMS SLD: comprehensive diagnostic battery 9 and the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) index for SLD 10 are commonly used for assessment, but there is a dearth of well-established norms for the subtypes of SLD. There is no screening tool available for teachers to identify SLD, and various education boards (central and state boards) have different levels of academic curriculum. Some tools like the NIMHANS index for SLD can only be administered in English-medium schools, whereas in India, about 42% of students are studying in Hindi-medium schools. 11 Although many tools are developed in regional languages like Tamil, Kannada, and Marathi, 12 there is no nationwide acceptability of these tools to certify children with SLD.

It is crucial to have a review to know the depth and breadth of the problem and the differences in the diagnostic criteria used in the studies. There is a lacuna in the evidence regarding the prevalence of SLDs, and usually, they go undetected. 13 , 14 Early diagnosis and assistance for a child with SLD is the need of the hour, and thus it is also essential to know about the diagnostic methods used. There is a lack of systematic reviews focused exclusively on the prevalence of SLD in India. Estimating the prevalence of SLD in India is valuable in planning diagnostic and intervention services. Information regarding the overall estimate of SLDs in the country will help develop a school-based policy for early identification, referral, and management of children with SLDs. Hence, this study was designed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the prevalence of SLD in Indian children and review the tools used for diagnosing SLD.

Materials and Methods

The protocol for the review was registered with PROSPERO (registration number- CRD42020154690).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

Two investigators (LMS and DB) searched the electronic databases of MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. Data search was carried out between June and August 2021. Because SLD prevalence studies were published since 1990, the authors selected 30 years to review articles (1990–2020). Additional searches were conducted in Google Scholar and grey literature sources such as documents of conferences and government websites. Hand searching and retrospective searching of relevant published literature was also done. All English-language studies containing information on SLD prevalence among children and adolescents aged 6 to 19 years were retrieved. To select the upper age limit, the WHO definition of adolescents as 10 to 19 years was adopted. 15 From the selected studies having information on the prevalence of SLD, information on screening criteria and tools used to diagnose SLD was identified and reviewed. A search strategy that included the combination of subject terms and free-text terms was employed using the operators “OR” and “AND.” The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were SLD, learning disability, learning disorder, dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, prevalence, and India. All MeSH terms were exploded where necessary ( Table 1 ).

Search Strategy Used in MEDLINE Database (1989-2020)

The population of interest was school-going children residing in India aged 6 to 19 years who were assessed for SLD using different existing tools for diagnosing SLD.

Inclusion Criteria

Observational studies, including cross-sectional, cohort, or case-control studies, of children with SLDs, using validated or nonvalidated tools, published in the English language and conducted in community settings, were included. Where multiple publications were generated from the same data with the same outcome, only the most relevant study was included.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that discussed therapy, management, and comorbidities of SLDs were excluded. Studies conducted in hospitals were excluded because the children are likely to be highly selected (i.e., selection bias), resulting in inaccurate estimations of the true prevalence of SLDs. Studies were excluded if children were not screened for intelligence quotient (IQ). Editorials, letters, opinion articles, narrative or systematic reviews, brief communications, and posters were excluded.

Screening Strategy

Two authors reviewed the titles and/or abstracts of studies identified using the search strategy and those from additional sources. They independently assessed the eligibility of the full-text articles. The third author (BG) reassessed all selected studies. Any disagreement between the reviewers was resolved through discussion with the third author.

Quality Analysis

The quality of reporting in the selected articles was checked using Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). The STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies was used to evaluate the relevant information from each article. LMS and DB independently assessed studies’ reporting quality. In case of any disagreement on this assessment, the issue was resolved by discussion or consensus with the third investigator (BG).

Data Extraction

A standardized data extraction form was developed and piloted based on the Cochrane good practice data extraction form template to extract data from the selected studies. Extracted information included study design and methods, study settings, participant characteristics, study outcomes, results, conclusions, and study funding sources.

The pooled prevalence of SLDs was estimated from the reported prevalence of eligible studies, using the random-effects model. Analyses were performed using STATA 16 (College Station, Texas, USA) software. Forest plots were generated displaying prevalence with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (asymptotic Wald) for each study. The I-squared (I2) test was used to assess heterogeneity. The tools used to diagnose SLD were identified from the selected articles and reviewed.

Literature Search

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement flowchart 16 in Figure 1 describes the literature screening, study selection, and reasons for exclusion. Out of 17 studies assessed for eligibility, 11 were excluded for the following reasons: management/interventional/risk factor studies, 17 , 18 no diagnosis done/only screened for different SLDs, 19 – 22 the prevalence of SLD was not assessed, 23 , 24 the study did not screen for the intelligence of the participant children, 25 and studies assessed only dyslexia. 26 , 27 A total of six studies met the inclusion criteria for this review and were finally included in the meta-analysis ( Table 2 ). 28 – 33

Characteristics of Selected Studies

SLD , specific learning disorders.

Description of Included Studies

The studies included in this review were conducted in different states of India, including Andhra Pradesh, Chandigarh, Goa, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha. All were cross-sectional studies done among children aged 6 to 19 years. The studies assessed children at a younger age itself, except for Arun et al., for which the age group was 12 to 19 years. Three studies assessed the subcategories of SLD separately along with the total prevalence of SLD 31 – 33 ; all other studies assessed SLD in total and not the subtypes. The study by Arora et al. was done in the community setting, 29 and all the other studies were conducted at schools. Of the studies conducted in schools, the study setting of four included both private and government schools. Three studies were conducted in urban areas alone. 31 – 33 The grade in which the students were studying ranged from Class II to Class XII. The articles by Mogasale et al., Sharma et al., and Shah and Buch assessed students of Classes III to IV, III to IV, and II to VI, respectively. 31 – 33

SLD was diagnosed with different diagnostic tools in different studies. The tools used to screen and diagnose SLD were the NIMHANS-SLD index and Grade Level Assessment Device (GLAD 34 ; Table 3 ). All the studies except Arora et al. used the NIMHANS-SLD index to diagnose SLD. The tool is available for English-medium students, and while using this tool, the authors used local language textbooks of lower grades for assessments.

Methodological Details of Specific Learning Disorders’ Screening and Evaluation Done

NDDs, neurodevelopmental disorders; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; GLAD, grade level assessment device; NIMHANS index, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences index for SLD; SLD, specific learning disorders; IQ, intelligence quotient.

The highest prevalence rate of SLD from individual studies was reported as 16.49% by Chacko and Vidhukumar, 30 followed by Mogasale et al., who reported a prevalence rate of 15.17%. 31 The least prevalence was reported as 1.58% by Arun et al. 28 Mogasale et al. reported 12.5%, 11.2%, and 10.5% prevalence of dysgraphia, dyslexia, and dyscalculia, respectively, 31 while the prevalence of SLD subtypes–dysgraphia, dyslexia, and dyscalculia–reported by Shan and Buch was 7.4%, 8.6%, and 7.1%, respectively. 32

The six studies of this systematic review have included the diagnostic screening of 8133 children. The random-effects meta-analysis showed that the overall pooled prevalence of SLD in India was 8% (95% CI = 4–11, Figure 2 ). In this meta-analysis, a high level of heterogeneity (98.72%) was observed between the studies. The diamond in the result represents the point estimate of 7.7% from all the individual studies together. The horizontal point of the diamond represents the 95% confidence interval of this combined point estimate.

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression were not attempted because the studies did not mention urban-rural differences or gender differences. Also, characteristics such as age group, type of study, and the diagnostic measure did not vary much among the studies.

In this meta-analysis, because the outcome measure is the prevalence and the probability that significance levels that may have biased publications are less, publication bias may not be applicable. The reasons for nonpublication are more likely small studies not using appropriate methodology. All the selected articles satisfied the STROBE criteria for reporting.

This systematic review reports an 8% prevalence of SLD in India. All the enrolled studies were recently published from 2012 to 2020. However, the six studies included in this review used a spectrum of tools for screening and diagnosis of SLD.

There is no single screening and diagnostic tool that may be considered specific for the diagnosis of SLD. The NIMHANS index for SLD was developed in 1991 in the Department of Clinical Psychology, NIMHANS, Bangalore. The NIMHANS index for SLD is a curriculum-based assessment that can be used to confirm the diagnosis of SLD. 10 It includes tests of reading, writing, spelling, and arithmetic abilities to detect children with disabilities in these areas. There are norms for children in Standards I to V. This battery can be used not only for confirming an initial diagnosis of SLD but also for certification of SLD in India. The Gazette of India (No. 61, dated January 6, 2018) states that the NIMHANS-SLD index shall be used to diagnose SLD in children. The tool can also be used for the assessment of improvement after remediation. However, the different types of SLDs cannot be picked up using this battery. 35 Besides, since the tool is in English and India is a multilingual country, professionals find it challenging to assess SLD in a child’s mother tongue.

The assessment using GLAD includes the level of functioning and process of learning. In developing this tool, the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT)-prescribed minimum levels of learning (MLL) were taken as standard. English, Hindi, and Mathematics textbooks from Class I to Class IV of the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE), and the state board in Andhra Pradesh were used to develop the tool. Items were taken from all the syllabi based on the MLL fixed based on NCERT stipulations. 34

There is a dearth of acceptable tools that are developed and validated in regional languages, particularly in rural parts of the country and the Adivasi population, where the dialects are different. The tools accepted for diagnosis of SLD are developed for students of English-medium schools, whereas in India, only one-fourth of the students study in English-medium schools. 36 The content used in the tools is not standardized. Existing tools have not included all the age groups for assessment, which makes assessment difficult, especially when the student is to be assessed in tenth or twelfth classes to issue a certificate for availing benefits. 37

In a population-based prevalence estimate from the USA, the prevalence of SLD reported was 9.7% in children aged 3 to 17 years. 7 Nearly 5% of the US school-age population have learning disabilities that have been formally identified. 38 Our study reports that nearly one in twelve Indian children have SLD. In Brazil, recent estimates show that the prevalence rate was 7.6% for global impairment, 5.4% for writing, 6.0% for arithmetic, and 7.5% for reading impairment. 39 Also, an epidemiological study from Turkey found the prevalence rate to be 13.6%. 40 A recent estimate from Pakistan showed a similar prevalence of 7.7% among primary school children. 41

SLDs are challenging to diagnose and are often not well understood as a group of disorders. There is a gap of nearly four years between the child’s age at SLD diagnosis and the mother’s first suspicion of a problem. 42 The treatment of SLD focuses on educational interventions, and early interventions are most desirable. 43 Therefore, it is crucial to identify SLD as soon as possible.

Lack of appropriate resources, tools, and support and lack of awareness among parents and school teachers are significant issues in the Indian context. 44 The multiple curriculums at schools, varying standards, and multilingualism prevent a unifying standardized approach. 45 Regional adaptations in protocols and universal screening of children are the vital components. Prospective studies (across different states and vernacular languages), multicenter collaborations, and longitudinal research with a large sample and a single comprehensive test battery are needed to understand the situation better and make the children achieve their maximum potential. Also, SLD epidemiology needs to develop into the arenas of operational research to study the utilization pattern of services as well, thereby making care available to those in need.

The high prevalence of SLD among children in India implies the need for awareness generation among parents and teachers. Adopting community sensitization programs will be beneficial for early identification and improving access to remedial education programs. Advocating and strengthening the integrated education system, management of comorbidities, and prevention of mental health problems will improve the quality of life of children with SLD.

This systematic review had a few limitations. There was heterogeneity in the methodology among the applied screening and diagnostic tools used in the included studies, which might have led to under‑ or over-estimation of the prevalence data. The prevalence rate trend analysis was not done because the studies were published recently within ten years. Subgroup analysis on rural versus urban population and male and female sex could not be done because the articles did not mention the required data. Prevalence in the subgroups of ages could not be assessed because data were not available for different age groups.

This review systematically analyzed data from Indian studies to determine the prevalence of SLD in India. This is the only systematic review on the topic so far, and it demonstrated that nearly 8% of children have SLD. This may include mild, moderate, and severe cases. The conclusion shall be inferred taking care of the study’s limitations. The study also highlights that there are only a few high-quality, population-based epidemiological studies on this topic. This review has contributed to explaining the prevalence estimates of SLD in India. The impact of factors such as urban or rural location, age, diagnostic tools, and medium of instructions on SLD prevalence needs to be further investigated. As India is a vast country, there is a pressing need to have extensive population-based surveys using appropriate screening and diagnostic tools. Constructing standardized assessment tools, keeping in view the diversity of Indian culture, is an enormous task. Similarly, regional-language-based screening and diagnostic tools must be developed for easy identification and reporting. Since SLD is included as one of the disabilities in the RPWD Act 2016, diagnosis and certification are warranted. Early diagnosis and disability certification are essential requirements for providing equal opportunities, equal rights, and equal participation of the children in the community.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the research team of the Child Development Center for their support during this study.

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Specific Learning Disability in India: Challenges and Opportunities

Affiliations.

- 1 Pediatric Neurology Unit, Department of Neurological Sciences, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India.

- 2 Pediatric Neurology Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, 160012, India. [email protected].

- PMID: 31900846

- DOI: 10.1007/s12098-019-03159-0

Publication types

- Learning Disabilities*

- My Shodhganga

- Receive email updates

- Edit Profile

Shodhganga : a reservoir of Indian theses @ INFLIBNET

- Shodhganga@INFLIBNET

- University of Delhi

- Dept. of Home Science

Items in Shodhganga are licensed under Creative Commons Licence Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

UNESCO New Delhi launches 2019 State of the Education Report for India focusing on Children with Disabilities

New Delhi, 3 July: The 2019 State of the Education Report for India: Children with Disabilities, was launched today at an event organized by UNESCO New Delhi, at the Taj Palace Hotel in New Delhi. It was attended by over 200 representatives from the government, civil society, academia, partners and youth.

To be published annually, the 2019 report is the first of its kind published by UNESCO New Delhi and highlights accomplishments and challenges with regards to the right to education of children with disabilities (CWDs). Based on extensive research of national and international documents of reference, it provides comprehensive and detailed information on the current state of education of CWDs and submits ten key suggestions to policy makers.

“ Much has already been done in India for the education of children with disabilities, but with this report we are suggesting a number of concrete recommendations, to take several more steps forward and help the nearly 8 million Indian children with disabilities get their share of an education ,” said Eric Falt, UNESCO New Delhi Director.

“ UNESCO’s State of the Education Report 2019 is expected to deepen our understanding in this regard and help the education system better respond to the learning need of children with disabilities. This will enable us to make significant progress towards our collective objective of leaving no one behind and provide to all children and youth equitable opportunities for quality learning ”, said the Vice President of India, Hon’ble Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu in his message.

The Report acknowledges that inclusive education is complex to implement and requires a fine understanding of diverse needs of children and their families across different contexts. India has made considerable progress in terms of putting in place a robust legal framework and a range of programmes and schemes that have improved enrolment rates of children with disabilities in schools. However, further measures are needed to ensure quality education for every child so as to achieve the goals and targets of Agenda 2030 and more specifically Sustainable Development Goal 4 .

At present, three-fourths of the children with disabilities at the age of 5 years and one-fourth between 5-19 years do not go to any educational institution. The number of children enrolled in school drops significantly with each successive level of schooling. There are fewer girls with disabilities in schools than boys with disabilities in school. Significant gaps therefore remain, even though successive government schemes and programs have brought large numbers of children with disabilities into schools.

For instance, more work is required in the field of assistive technologies, with particular attention paid to bridging the digital divide and overcoming equity concerns. As an example of good practice, recently, in a two-year research-cum-documentation project in the North East, sign languages operating in the region were compiled in a web-based application known as 'NESL Sign Bank'. It is an online open source educational resource that contains information regarding the types of sign languages used by the deaf community. Currently the application incorporates data for 3000 words and has the potential to increase the database further. In 2018, the app was awarded with the Jury Appreciation Award at the 22nd All Indian Children’s Educational Audio-Video Festival & ICT Mela.

Government bodies have undertaken many other initiatives to make resources accessible to children with disabilities. The National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) created the Barkha – Graded Reading Series for children, which highlights the possibilities of Universal Design of learning. NCERT has developed two manuals on ‘Including Children with Special Needs’ for primary and upper primary stage teachers. Many States are using them extensively to understand the need for curriculum adaptations wherever children with disabilities study alongside other children in inclusive classrooms.

According to the UNESCO report, the attitude of parents and teachers towards including children with disabilities into mainstream education is also crucial to accomplish the goal of inclusive education. Development of inclusive practices requires flexible curriculum and availability of appropriate resources. Different frameworks for curriculum design can be adopted to develop curriculum that is both universal and suitable to adaptations. Accessibility to physical infrastructure, processes in the school, assistive and ICT technology and devices are also essential resources.

Emerging from extensive analysis, the report proposes a set of ten recommendations:

- Amend the RTE Act to better align with the RPWD Act by including specific concerns of education of children with disabilities.

- Establish a coordinating mechanism under MHRD for effective convergence of all education programmes of children with disabilities.

- Ensure specific and adequate financial allocation in education budgets to meet the learning needs of children with disabilities.

- Strengthen data systems to make them robust, reliable and useful for planning, implementation and monitoring.

- Enrich school ecosystems and involve all stakeholders in support of children with disabilities.

- Massively expand the use of information technology for the education of children with disabilities.

- Give a chance to every child and leave no child with disability behind.

- Transform teaching practices to aid the inclusion of diverse learners.

- Overcome stereotypes and build positive dispositions towards children with disabilities, both in the classroom and beyond.

- Foster effective partnerships involving government, civil society, the private sector and local communities for the benefit of children with disabilities.

UNESCO hopes that the report will serve as a reference tool for enhancing and influencing the policies and programs that practice inclusion and scale-up quality education opportunities for CWDs.

The substance of the Report has been developed by an experienced team of researchers from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, under the guidance of UNESCO New Delhi.

As part of the launch, the media will have prior access to the full report (Strictly embargoed till its launch on 3 July 2019), along with finished audio-visual products that include:

- over 100 high quality images from four different locations in India;

- short videos (duration 3-4 mins);

- one minute capsules, focusing on themes, such as, Transforming teaching practices; Expanding the use of ICTs; An ecosystem to empower CWDs; and Learning with each other and about each other (All free of copyrights).

- Raw footage and the social media media pack will be also available on request.

Note to the Editors

The State of the Education Report for India, is one of UNESCO New Delhi’s flagship reports to be published annually. Its main objective will be to monitor progress towards the education targets in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The Vision for Inclusive Education The international normative framework comprising the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), Sustainable Development Goals, specifically SDG4 and the Agenda 2030 provides a strong vision and a set of goals that have guided India’s processes of fostering inclusion in schools.

The RTE Act 2009 and the RPWD Act 2016 have helped create a comprehensive legal framework for inclusive education. However, there remain a few ambiguities in terms of where children with disabilities should study and who should teach them; and gaps in terms of appropriate norms and standards applicable to all educational institutions and services provided to children with disabilities and an absence of a coordinated authority that can enforce the norms and standards.

The operationalization of the legal provisions is primarily done through the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan which envisions inclusive education as the underlying principle of providing a continuum of education. While it emphasizes on increasing enrolment of children with disabilities in regular schools, removal of barriers, training of teachers and use of technology, it also provides for home-based education. It expressly imagines the role of special schools as resource centres for general teachers who are required to teach children with disabilities. Samagra Shiksha also envisages convergence among the different schemes and programmes for children with disabilities that are spread across various ministries and departments. Implementation of the scheme with the conceived coordinated effort is yet to be operationalised.

About UNESCO

UNESCO is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. It seeks to build peace through international cooperation in Education, the Sciences and Culture. UNESCO's programmes contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals defined in Agenda 2030 , adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2015.

In this spirit, UNESCO develops educational tools to help people live as global citizens free of hate and intolerance. UNESCO works so that each child and citizen has access to quality education. By promoting cultural heritage and the equal dignity of all cultures, UNESCO strengthens bonds among nations. UNESCO fosters scientific programmes and policies as platforms for development and cooperation. UNESCO stands up for freedom of expression, as a fundamental right and a key condition for democracy and development. Serving as a laboratory of ideas, UNESCO helps countries adopt international standards and manages programmes that foster the free flow of ideas and knowledge sharing.

Related items

- Country page: India

- UNESCO Office in New Delhi

- SDG: SDG 4 - Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

This article is related to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals .

Other recent news

Advertisement

Specific learning disabilities and higher education: The Indian scenario and a comparative analysis

- Published: 03 December 2021

- Volume 12 , pages 395–415, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Uday Shankar 1 &

- Ashok Vardhan Adipudi 2

289 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Learning is in itself an institute of life. The impact of disability, physical or otherwise, on daily activities is profound. In 2016, the Indian law on disabilities became more inclusive by broadening the categories of disabled persons and widened the rights of persons with disabilities. In the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016, besides revising the benefits for physically disabled persons, the recognition of equal rights to persons with Specific Learning Disabilities (SLDs) is historic. The paper, set in the context of higher education, explains the concessions and accommodations provided under the current legislative scheme for SLDs and explores how different jurisdictions have addressed SLDs. Secondly, to realise how the rights provided by these legislations are to be operationalised in higher education institutions; this step assumes significance because neither students with SLDs have access to trained personnel, nor the accommodations in the higher education has been well-articulated. The findings of the comparative study and understanding of the Indian legislative framework suggest measures to how higher educational institutions are to made more accessible to SLDs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The justification for inclusive education in Australia

Education and Parenting in the Philippines

Neurodiversity in higher education: a narrative synthesis

See Anna Lawson and Angharad E Beckett, ‘The Social and Human Rights Models of Disability: Towards a Complementarity Thesis’ (2021) 25(2) The International Journal of Human Rights 348.

Charlene Andolina, ‘Syntactic Maturity and Vocabulary Richness of Learning Disabled Children

at Four Age Levels’ (1980) 13(7) Journal of Learning Disabilities 27. The work explains and contrasts the changes observed in learning trends of learning disabled students and their peers.

The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act 2009, Act No. 35 of 2009.

The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016, Act No. 49 of 2016. (The Indian RPWD Act).

The word in Hindi refers to the ‘specially-abled’ and is an attempt at reducing the social stigma around persons with disabilities. The Gazette Notification of the Indian RPWD Act, in its Hindi version, uses the said word in lieu of ‘person with disability.’ In the contemporary context of SLDs and mental health as well, the word is retained for its use known from the Indian RPWD Act.

Abhilash Balakrishnan et al., ‘The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016: Mental Health Implications’ (2019) 41(2) Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 119, 120-121.

Vikash Kumar v Union Public Service Commission (2021) 5 SCC 370 [32].

The Indian RPWD Act ss 60-73.

Ibid. ss 74-83.

Ibid. ss 84, 85.

India signed the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and subsequently ratified the same on October 1 2007.

The Indian RPWD Act, The Schedule entries 1-6.

The Indian RPWD Act s 2(r) ‘person with benchmark disability’ means a person with not less than forty percent of a specified disability where specified disability has not been defined in measurable terms and includes a person with disability where specified disability has been defined in measurable terms, as certified by the certifying authority; The Indian RPWD Act s 2(s) ‘person with disability’ means a person with long term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment which, in interaction with barriers, hinders his full and effective participation in society equally with others; The Indian RPWD Act s 2(t) ‘person with disability having high support needs’ means a person with benchmark disability certified under clause (a) of sub-section (2) of Section 58 who needs high support.

The Indian RPWD Act s 2(s).

Balakrishnan et al., ‘The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016’ (n 6).

Srikala Naraian and Poonam Natarajan, ‘Negotiating Normalcy with Peers in Contexts of Inclusion: Perceptions of Youth with Disabilities in India’ (2013) 60(2) International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 146.

See Suresh Bada Math et al., ‘The Rights of Persons with Disability Act, 2016: Challenges and Opportunities’ (2019) 61(10) Indian Journal of Psychiatry 809.

‘India’ ( UNESCO Institute for Statistics , 10 April 2021). uis.unesco.org/en/country/in. Accessed 29 September 2021. Data as of September 2020.

Pramod Arora v Hon’ble Lt Governor of Delhi (2014) SCC OnLine Del 1402.

Rajneesh Kumar Pandey v Union of India W P (C) 132/2016. [Order dated 4 December 2017].

Ibid. [Order dated 8 March 2016].

Nidhi Singal, ‘Inclusive Education in India: International Concept, National Interpretation’ (2006) 53(3) International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 351.

20 USC Ch 33: Education of Individuals with Disabilities.

Ibid. s 1401 (3)(A).

Ibid. s 1401 (9)(c).

Americans with Disabilities Act 1990, 42 USC Ch 126 s 12101 et seq.

Ibid. s 12102 (1), (2).

Ibid. s 12102 (2)(A).

Defined in Section 8 of Title 1 of the USC to mean a child born alive at any stage of development.

20 USC s 1414 on evaluations, eligibility determinations, individualised education programs, and educational placements of children with disabilities; 20 USC ss 1431-1444 on eligibility, authorisation, and allocation of funds for infants with disabilities.

29 USC s 794 (a).

House of Representatives Report No. 485, 101st Congress, 2nd Session, part 2 (1990), 50; House of Representatives Report No. 485, 101st Congress, 2nd Session, part 3 (1990) 27; Senate Report No. 116, 101st Congress, 1st Session (1989) 21-22. Also see 29 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) s 1630.2 (h)(1-2) (1998) which contains a similar definition.

The Equality Act 2010, c 15 (UK) s 6(1) (The Equality Act).

Ibid. Schedule 1.

The Education Act, Original Enactment: Ordinance 45 of 1957 (Singapore); The Compulsory Education Act, Original Enactment: Act 27 of 2000 (Singapore).

Ministry of Social and Family Development , First Enabling Masterplan (EMP 1) 2007–2011 . https://www.msf.gov.sg/policies/Disabilities-and-Special-Needs/Pages/EM%201.pdf . Accessed 6 September 2021. Ch 1.

Definition Of ‘Disability’ For Social Policies . ( Ministry of Social and Family Development , 8 July 2019). https://www.msf.gov.sg/media-room/Pages/Definition-of-'Disability'-for-Social-Policies.aspx . Accessed April 10, 2021.

Ministry of Social and Family Development, First Enabling Masterplan (n 37).

Federal Law No. 29 of 2006 (UAE), art 1 (Federal Law No. 29).

42 USC s 2000e-4.

See e.g., McGuinness v New Mexico School of Medicine 170 F 3d 974, 977-78 (10th Circuit 1998); Price v National Board of Medical Examiners 966 F Supp 419, 425-26 (S D W Va 1997).

Bragdon v Abbott 524 US 624 (1998).

The Equality Act Schedule 1, para 12, sub-para (1).

Federal Law No. 29 art 11.

42 USC Ch 21, sub-chapters V and VI.

34 CFR Part 104 (2000).

Ibid. Part 104.44 (b), (d) (2000).

29 USC s 794.

Laura F Rothstein, ‘Higher Education and the Future of Disability Policy’ (2000) 52(1) Alabama Law Review 241.

Susan M Denbo, ‘Disability Lessons in Higher Education: Accommodating Learning-Disabled Students and Student-Athletes under the Rehabilitation Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act’ (2003) 41(1) American Business Law Journal 145.

See Laura F Rothstein, ‘Students Staff and Faculty with Disabilities: Current Issues for Colleges and Universities’ (1991) 17(4) Journal of College and University Law , 471; Donald Stone, ‘The Impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act on Legal Education and Academic Modifications for Disabled Law Students: An Empirical Study’ (1996) 44(3) University of Kansas Law Review 567; Bonnie Poitras Tucker, ‘Application of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 to Colleges and Universities: An Overview and Discussion of Special Issues Relating to Students’ (1996) 23(1) Journal of College and University Law 1.

The Equality Act ss 11, 19.

Ibid. s 20(3), (4), (5). Section 20 of the Equality Act 2010 mandates that institutes be responsible for 3 requirements that might cause a substantial disadvantage: provision, criterion, or practice (in academic institutions this broad requirement might manifest in respect of any additional teaching that might be necessary for a specially disabled student); physical feature; substantial disadvantage ‘but for the provision of an auxiliary aid.’

Ibid. Part 9.

‘Resources for Students: Academic Support, Non-Academic Support, Community and Peer Support’ ( National University of Singapore ). https://nus.edu.sg/osa/student-services/student-accessibility-unit/resources-for-students/ . Accessed 12 October 2021.

‘Disability Services’ ( Singapore Management University ). https://www.smu.edu.sg/campus-life/disability-services . Accessed 10 April 2021.

Federal Law No. 29 art 13.

Law 4485/2017 (Greece) art 8, 13, 34. The said provisions elaborate on the mandatory internal regulatory mechanisms to be provided by higher educational institutions, followed by the measures to be taken by institutions for the benefit of students with disabilities.

‘Validation of Non-formal and Informal Learning’ ( European Commission ). https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/validation-non-formal-and-informal-learning-32_en . Accessed 10 April 2021.

‘Country Information for Greece-Legislation and Policy’ ( European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education ). https://www.european-agency.org/country-information/greece/legislation-and-policy . Accessed 10 April 2021.

Law 4547/2008 (Greece) art 4-7.

20 USC s 1414(a).

Ibid. s 1414(a)(B).

Ibid. s 1414(a).

Ibid. s 1414.

Ibid. s 1414(c)(5).

Ibid. s 1414(d)(1)(B).

Ibid. s 1415(b)(1).

Ibid. s 1415(b)(2).

Ibid. s 1415(b)(5) and (b)(6).

Ibid. s 1415(e)(2)(B).

34 CFR s 104.36.

The provision currently available as 20 USC s 1415, as amended by Public Law 101-476.

See 29 USC Ch 16: Vocational Rehabilitation and other Rehabilitation Services.

Ibid. s 794a.

34 CFR s 104.7.

On public services, see 42 USC s 12133; On public accommodations and services operated by private entities, see 42 USC s 12188.

34 CFR Part 104.

Ibid. Although Article 11 empowers the committee to work on programs for early detection and diagnostics, the Committee has not yet provided any particular standards for determination of specific learning disabilities as was realised in Singapore. For reference to the Singaporean provisions, see Ministry of Social and Family Development, First Enabling Masterplan (n 37).

See National Research Centre on Learning Disabilities, SLD Identification Overview . https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED543737.pdf . Accessed 10 April 2021.

Lee J Cronbach, ‘The Two Disciplines of Scientific Psychology’ (1957) 12(11) American Psychologist 671; Lee J Cronbach, ‘Beyond the Two Disciplines of Scientific Psychology’ (1975) 30(2) American Psychologist 116.

F M Gresham, ‘Responsiveness to Intervention: An Alternative Approach to the Identification of Learning Disabilities’ in R Bradley, L Donaldson, and D Hallahan (eds) Identification of Learning Disabilities: Research to Practice (2002) 467; K A Kavale and S R Forness, ‘Substance Over Style: A Quantitative Synthesis Assessing the Efficacy of Modality Testing and Teaching’ (1987) 54(3) Exceptional Children 228.

Albert F Restori, Gary S Katz, and Howard B Lee, ‘A Critique of the IQ/Achievement Discrepancy Model for Identifying Specific Learning Disabilities’ (2009) 5(4) Europe’s Journal of Psychology 128, 136.

National Council for Special Education, Procedures used to Diagnose a Disability and to Assess Special Educational Needs: An International Review . 133-150. https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5_NCSE_Diag_Ass.pdf . Accessed 10 April 2021.

The Indian RPWD Act s 56.

For the amendment made in 2020, see Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Guidelines for Assessment of Various Specified Disabilities (9 December 2020). https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_25_54_00002_201649_1517807328299&type=notification&filename=amendment_guidelines__09.09.2020.pdf . Accessed 31 September 2021.

Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Guidelines for the Purpose of Assessing the Extent of Specified Disability in a Person Included Under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (49 of 2016) (4 January 2018, as amended on 9 December 2020). Annexure II. https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_25_54_00002_201649_1517807328299&type=notification&filename=Guidelines%20notification_04.01.2018.pdf . Accessed 12 October 2021.

See Rights of Persons with Disabilities Rules 2017, Rule 14A.

The law by laying down a framework for certification as an aspect of disability rights and also making it imperative for different institutions to provide appropriate benefit based on said certification, has created a dichotomy of recognition of eligibility of the benefit and grant of benefit.

See the Indian RPWD Act s 6(2). There is no provision of a legislative instrument deals exclusively with sensitised and trained human resources.

Geoff Lindsay, ‘Educational Psychology and the Effectiveness of Inclusive Education/Main-streaming’ (2007) 77(1) British Journal of Educational Psychology 1, 9, 15-18.

See A Llewellyn and K Hogan, ‘The Use and Abuse of Models of Disability’, (2000) 15(1) Disability & Society 157, for an overview of different models of disability including the transactional and ecological model.

Aakash Johry and Ravi Poovaiah, ‘Playfulness Through the Lens of Toy Design: A Study with Indian Preschool Children with Intellectual Disability’ (2019) 8(3) International Journal of Play 255, 258-259. The dimensionality of playfulness in children with SLDs replicates more than a mere physical/organ impairment. Mere physical impairment in many senses is inadequate for working with SLDs.

The Indian RPWD Act s 32.

Council for Science and Technology, Current Understanding, Support Systems, and Technology-led Interventions for Specific Learning Difficulties: Evidence Reviews Commissioned for Work by the Council for Science and Technology , 23. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/926052/specific-learning-difficulties-spld-cst-report.pdf . Accessed 10 April 2021.

Refers to the requirement of certification as laid down in the Indian RPWD Act for the student to avail reservation in an educational institution. See The Indian RPWD Act ss 56-59.

See e.g., The Equality Act s 91, lays down positive obligations of the responsible body of the higher education institute.

Sadananda Reddy Annapally et al., ‘Development of a Supported Education Program for Students with Severe Mental Disorders in India’ (2020) 43(3) Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 217.

See The Indian RPWD Act s 2(s). (Emphasis added).

Ibid. Para 2 of the Schedule.

Ministry of Social and Family Development, Definition Of ‘Disability’ For Social Policies . https://www.msf.gov.sg/media-room/Pages/Definition-of-'Disability'-for-Social-Policies.aspx . Accessed 10 April 2021; Ministry of Social and Family Development, First Enabling Masterplan (n 37).

Adrian Higgins, ‘Intellectual Disability or Learning Disability? Let’s Talk Some More’ (2014) 1(2) Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 142, 145.

See Varsha Vidyadharan and Harish M Tharayil, ‘Learning Disorder or Learning Disability: Time to Rethink’ (2019) 41(3) Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 276.

Office of the Deputy Director of Education, Instructions for Preparing Individualised Education Plan , (Circular No F.150 /DDE(IEDSS)/Admn.Cell/2016-17/1125, 17 August 2016).

Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Guidelines for the Purpose of Assessing the Extent of Specified Disability in a Person Included Under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (49 of 2016) (n 94).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipur, India

Uday Shankar

Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Ashok Vardhan Adipudi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Uday Shankar .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author has no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Shankar, U., Adipudi, A.V. Specific learning disabilities and higher education: The Indian scenario and a comparative analysis. Jindal Global Law Review 12 , 395–415 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41020-021-00155-4

Download citation

Accepted : 18 October 2021

Published : 03 December 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41020-021-00155-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Specific learning disabilities (SLDs)

- Disability law

- Comparative study

- Higher education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

COMMENTS

A learning disabled child may face problem in reading, writing, spelling, speech or the power of memorization. In the present case the child is able to write well. She can do mathematics fairly well, can speak very clearly and is socially active. She is quite neat in her presentation APRIL-MAY, 2014. Vol.

Case Study: - A Case Study on a actual situation:- In this activity I Mr Vipan Raj Sardar Patel University Balaghat,{MP} have of a student/ child taken a real situation of a village, Jagota of tehsil Bhella , District Doda Jammu & Kashmir (India) thfrom class 6 from a government school where the student with special need/learning difficulty

Specific learning disorders (SLD), often referred to as learning disability, is a neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) and refers to ongoing problems in one of the three basic skills-reading, writing, and arithmetic-which are the essential requisites for the learning process. 1 These difficulties, namely dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, and developmental aphasia, 2 can occur ...

Specific Learning Disability in India: Challenges and Opportunities. Indian J Pediatr. 2020 Feb;87 (2):91-92. doi: 10.1007/s12098-019-03159-. Epub 2020 Jan 3.

The most recent, Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, oversees the implementation of the Right to Education Act from pre-school to Year 12.It has a broader goal to improve school effectiveness in terms of equal opportunities, and equitable learning outcomes and aims to 'enable all children and young persons with disabilities to have access to inclusive education and improve their enrolment, retention ...

The present study by Chordia et al. is a school-based, cross-sectional study conducted at Puducherry to ascertain the proportion of children aged 5 to 7 y at risk of specific learning disability (SLD) and to analyse the sociodemographic risk factors [].The methodology is comprehensive and was done in three phases starting from screening assessment by school teachers, evaluation to rule out ...

The issue of disability reveals an alarming concern of inclusive education and exclusion process in ongoing development. Disability and particularly learning disability exclude a sizeable population of children out of school, increase dropout and a challenge for universalisation of education and development of any society. A rough indication gives high prevalence about 10%; however, actual ...

The prevalence of learning disabilities in India ranges from 2.16% to 30.77%. ... Chahar C, Singhal AK. A case control study on specific learning disorders in school going children in Bikaner city Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:1477-81 ... Kumar J, Singh S. Identification and prevalence of learning disabled students Int J Sci Res Publ. 2017Last ...

A study of inclusive education practices for children with disabilities in selected states of India: Researcher: Jayanti Prakash: Guide(s): Asha Singh and Mukhopadhyay, Sudesh: Keywords: Developmental disabilities Education Special Learning disabilities Movement disorders People with disabilities Perceptual disorders Social Sciences Social ...

However, further measures are needed to ensure quality education for every child so as to achieve the goals and targets of Agenda 2030 and more specifically Sustainable Development Goal 4. At present, three-fourths of the children with disabilities at the age of 5 years and one-fourth between 5-19 years do not go to any educational institution.

that only 1 percent of children with disabilities in the 5-15 age group had access to education. recent World Bank Report (2007) highlighted that 38 per cent of the children with disabilities in. the age group 6-13 years are out of school. Irrespective of the estimate, in India the fact remains.

In a study by Rao et al. , the prevalence of dyslexia was studied in a group of 400 students in Mysore, and the rate was found to be 13.67%. In another study, Arun et al. attempted to study the prevalence of specific learning disabilities in students of Class VII to XII in Chandigarh. This was a large study, with a sample of 1301 from ...

Support for Learning is a special education journal publishing articles on the education of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools. In this article we report on various initiatives taken by the government since India's independence in 1947 to provide education to school-aged children with disabilities. The majority of ...

There is a dearth of systematic reviews focused exclusively on the prevalence of SLD in India. Hence, this study was done to estimate the prevalence of SLD in Indian children. ... A longitudinal study from five to eleven years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 1986; 27: 597-610. Crossref. ... Coping and defense mechanisms of mothers of learning ...

A Journey to Stare Then Reach - a case study of a special child. This is a story of a little angel of in the school Durgabhai Deshmukh Vocational Training and Rehabilitation Centre. The mother of the little angel is a homemaker while her father was working at a press. Little angel was the first child of her parents and was born on 19th March 2012.

The moniker "special child" is a commonly used term in India to refer to a child with a disability. India's most recent census data from 2011 estimated that approximately 6.5 million Indian children between the ages of 5-19 have a disability (Office of the Registrar 2011). The Indian census website allows for examination of the data at ...

Highlights Every child in India has the fundamental right to elementary education, including children with disabilities. India was one of the first countries to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), showing its strong commitment to upholding the rights of persons with disabilities and to ensuring that children with disabilities have access to ...

The case studies have a specific focus on children with disabilities and their families. However, many of the highlighted initiatives are designed for broad inclusion and benefit all children. In particular, this case study, covers such topics as: Inclusive Preschool, Assistive Technologies (AT), Early Childhood intervention (ECI ...

Experiences of Students with Learning Disabilities in Higher Education: A Scoping Review. Indian J Psychol Med. 2024;46(3):196-207. Address for correspondence: Anekal C Amaresha, Dept. of Psychiatric Social Work, Lokopriya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Institute of Mental Health (LGBRIMH), Tezpur, Assam 784001, India. E-mail: [email protected].

In India, exclusive efforts are not made to find out the incidence of LD but it has been established that 13-14% of our schoolchildren are with learning disorders. These children who require help are in an evaluation system predominantly based on written examination, which is a disadvantage to the learning-disabled child.

Education Case Study INDIA In March 2020, when COVID-19 closed schools in India, it disrupted the education of millions of children. Schools reopened fully two years later in March 2022 following the Omicron wave of infection, but just in the final month of the 2021/2022 school year. There are high hopes that the 2022/2023 academic year,

The process of parenting a disabled child has profound effects on the quality of life (QoL) of caregivers. ... Kurani et al. conducted a study in Mumbai, India, where parents were actively involved in learning readiness programme and its impact was measured on social, language, behavioural and cognitive development of children with severe and ...

Learning is in itself an institute of life. The impact of disability, physical or otherwise, on daily activities is profound. In 2016, the Indian law on disabilities became more inclusive by broadening the categories of disabled persons and widened the rights of persons with disabilities. In the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016, besides revising the benefits for physically disabled ...