- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Types, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

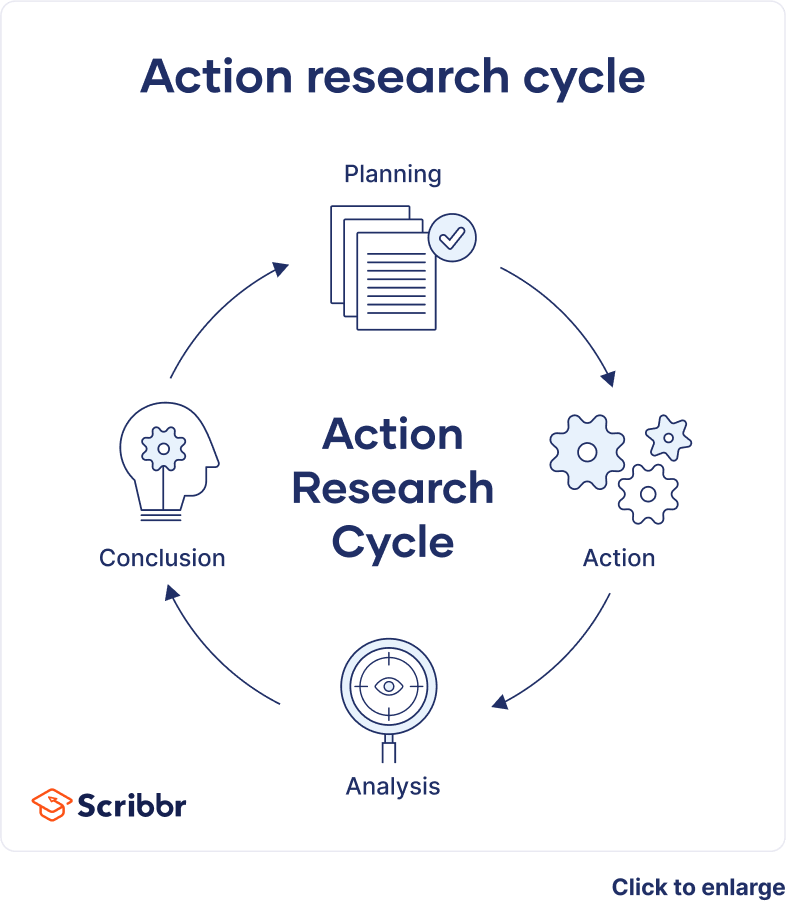

By engaging in cycles of planning, observation, action, and reflection, action research enables participants to identify challenges, implement solutions, and evaluate outcomes. This approach generates practical knowledge and empowers individuals and organizations to effect meaningful change in their contexts.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system .

What is Action Research?

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research , it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

Important Types of Action Research

Here are the main types of action research:

1. Practical Action Research

It focuses on solving specific problems within a local context, often involving teachers or practitioners seeking to improve practices.

2. Participatory Action Research (PAR)

A research process in which people, staff, and activists work together to generate knowledge from a study on an issue that adds value and supports their actions for social change.

3. Critical Action Research

Built to address power and social injustices in light of the Hegemonic Underpinnings, this research facilitates a callback, self-reflection, and thorough societal reformations.

4. Collaborative Action Research

In this form of research, a team of practitioners joins to do project work as part of an overall effort to improve. The work continues into the analysis phase with these same folks across all stages.

5. Reflective Action Research

This kind of research emphasizes individual or group reflection on practices. The key to this model is that it encourages reflective and deliberate practice, thus promoting learning and unfolding within ongoing experiences.

6. Transformative Action Research

This model empowers participants to address issues within their communities related to social justice and transformation.

Each type serves different contexts and goals, contributing to the overall effectiveness of action research.

Stages of Action Research

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

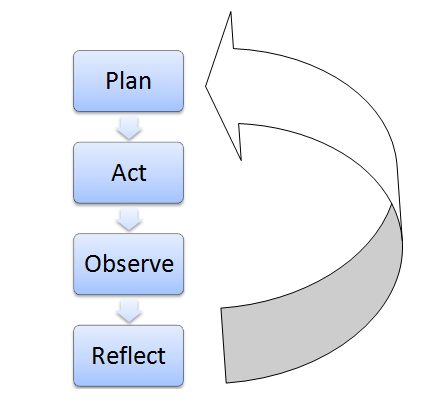

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation . This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

The Steps of Conducting Action Research

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

1. Identify The Action Research Question or Problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

2. Review Existing Knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design .

3. Plan The Research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools , and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

4. Collect Data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups . Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

5. Analyze The Data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

6. Reflect on The Findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

7. Develop an Action Plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

8. Implement The Action Plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

9. Evaluate and Monitor Progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

10. Reflect and Iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Examples of Action Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Action Research

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

Why QuestionPro Research Suite is Great for Action Research?

QuestionPro Research Suite is an ideal choice for action research, which typically involves multiple rounds of data collection , analysis, and intervention cycles. This is one reason it might be great for that:

01. Data Collection

QuestionPro offers flexible and adaptable methods for data dissemination. You can collect and store crucial business data from secure, personalized questionnaires , and distribute them through emails, SMSs, or even popular social media platforms and mobile apps.

This adaptability is particularly useful for action research, which often requires a variety of data collection techniques.

02. Advanced Analysis Tools

- Efficient Data Analysis: Built-in tools simplify both quantitative and qualitative analysis.

- Powerful Segmentation: Cross-tabulation lets you compare and track changes across cycles.

- Reliable Insights: This robust toolset enhances confidence in research outcomes.

03. Collaboration and Real-Time Reporting

Multiple researchers can collaborate within the platform, sharing permissions and changes in real-time while creating reports. Asynchronous collaboration: Conversation threads and comments can be in one place, ensuring all team members stay updated and are aligned with stakeholders throughout each action research phase.

04. User-Friendly Interface

At the user level, what kind of data visualization charts/graphs, tables, etc., should be provided to visualize the complex findings most often done through these)? Across all solutions, we need fully customizable dashboards to offer perfect vision to different people so they can make decisions and take action based on this data.

05. Automation and Integration Capabilities

- Workflow Automation: Enables recurring surveys or updates to run seamlessly.

- Time Savings: Frees up time in long-term research projects.

- Integrations: Connects with popular CRMs and other applications.

- Simplified Data Addition: This makes incorporating data from external sources easy.

These features make QuestionPro Research Suite a powerful tool for action research. It makes it easy to manage data, conduct analyses, and drive actionable insights through iterative research cycles.

Action research is a dynamic and participatory approach that empowers individuals and communities to address real-world challenges through systematic inquiry and reflection.

The methods used in action research help gather valuable insights and foster continuous improvement, leading to meaningful change across various fields. By promoting iterative cycles, action research generates knowledge and encourages a culture of learning and adaptation, making it a crucial tool for driving transformation.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Research Suite if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

Total Experience in Trinidad & Tobago — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Oct 29, 2024

You Can’t Please Everyone — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Oct 22, 2024

Life@QuestionPro Presents: Andrews Sekar

Oct 14, 2024

Edit survey: A new way of survey building and collaboration

Oct 10, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Action Research: Steps, Benefits, and Tips

Introduction

History of action research, what is the definition of action research, types of action research, conducting action research.

Action research is an approach to qualitative inquiry in social science research that involves the search for practical solutions to everyday issues. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature, the action research process goes beyond traditional research paradigms by emphasizing the involvement of those being studied in resolving social conflicts and effecting positive change.

The value of action research lies not just in its outcomes, but also in the process itself, where stakeholders become active participants rather than mere subjects. In this article, we'll examine action research in depth, shedding light on its history, principles, and types of action research.

Tracing its roots back to the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin developed classical action research as a response to traditional research methods in the social sciences that often sidelined the very communities they studied. Proponents of action research championed the idea that research should not just be an observational exercise but an actionable one that involves devising practical solutions. Advocates believed in the idea of research leading to immediate social action, emphasizing the importance of involving the community in the process.

Applications for action research

Over the years, action research has evolved and diversified. From its early applications in social psychology and organizational development, it has branched out into various fields such as education, healthcare, and community development, informing questions around improving schools, minority problems, and more. This growth wasn't just in application, but also in its methodologies.

How is action research different?

Like all research methodologies, effective action research generates knowledge. However, action research stands apart in its commitment to instigate tangible change. Traditional research often places emphasis on passive observation , employing data collection methods primarily to contribute to broader theoretical frameworks . In contrast, action research is inherently proactive, intertwining the acts of observing and acting.

The primary goal isn't just to understand a problem but to solve or alleviate it. Action researchers partner closely with communities, ensuring that the research process directly benefits those involved. This collaboration often leads to immediate interventions, tweaks, or solutions applied in real-time, marking a departure from other forms of research that might wait until the end of a study to make recommendations.

This proactive, change-driven nature makes action research particularly impactful in settings where immediate change is not just beneficial but essential.

Action research is best understood as a systematic approach to cooperative inquiry. Unlike traditional research methodologies that might primarily focus on generating knowledge, action research emphasizes producing actionable solutions for pressing real-world challenges.

This form of research undertakes a cyclic and reflective journey, typically cycling through stages of planning , acting, observing, and reflecting. A defining characteristic of action research is the collaborative spirit it embodies, often dissolving the rigid distinction between the researcher and the researched, leading to mutual learning and shared outcomes.

Advantages of action research

One of the foremost benefits of action research is the immediacy of its application. Since the research is embedded within real-world issues, any findings or solutions derived can often be integrated straightaway, catalyzing prompt improvements within the concerned community or organization. This immediacy is coupled with the empowering nature of the methodology. Participants aren't mere subjects; they actively shape the research process, giving them a tangible sense of ownership over both the research journey and its eventual outcomes.

Moreover, the inherent adaptability of action research allows researchers to tweak their approaches responsively based on live feedback. This ensures the research remains rooted in the evolving context, capturing the nuances of the situation and making any necessary adjustments. Lastly, this form of research tends to offer a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand, harmonizing socially constructed theoretical knowledge with hands-on insights, leading to a richer, more textured understanding.

Disadvantages of action research

Like any methodology, action research isn't devoid of challenges. Its iterative nature, while beneficial, can extend timelines. Researchers might find themselves engaged in multiple cycles of observation, reflection, and action before arriving at a satisfactory conclusion. The intimate involvement of the researcher with the research participants , although crucial for collaboration, opens doors to potential conflicts. Through collaborative problem solving, disagreements can lead to richer and more nuanced solutions, but it can take considerable time and effort.

Another limitation stems from its focus on a specific context: results derived from a particular action research project might not always resonate or be applicable in a different context or with a different group. Lastly, the depth of collaboration this methodology demands means all stakeholders need to be deeply invested, and such a level of commitment might not always be feasible.

Examples of action research

To illustrate, let's consider a few scenarios. Imagine a classroom where a teacher observes dwindling student participation. Instead of sticking to conventional methods, the teacher experiments with introducing group-based activities. As the outcomes unfold, the teacher continually refines the approach based on student feedback, eventually leading to a teaching strategy that rejuvenates student engagement.

In a healthcare context, hospital staff who recognize growing patient anxiety related to certain procedures might innovate by introducing a new patient-informing protocol. As they study the effects of this change, they could, through iterations, sculpt a procedure that diminishes patient anxiety.

Similarly, in the realm of community development, a community grappling with the absence of child-friendly public spaces might collaborate with local authorities to conceptualize a park. As they monitor its utilization and societal impact, continual feedback could refine the park's infrastructure and design.

Contemporary action research, while grounded in the core principles of collaboration, reflection, and change, has seen various adaptations tailored to the specific needs of different contexts and fields. These adaptations have led to the emergence of distinct types of action research, each with its unique emphasis and approach.

Collaborative action research

Collaborative action research emphasizes the joint efforts of professionals, often from the same field, working together to address common concerns or challenges. In this approach, there's a strong emphasis on shared responsibility, mutual respect, and co-learning. For example, a group of classroom teachers might collaboratively investigate methods to improve student literacy, pooling their expertise and resources to devise, implement, and refine strategies for improving teaching.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research (PAR) goes a step further in dissolving the barriers between the researcher and the researched. It actively involves community members or stakeholders not just as participants, but as equal partners in the entire research process. PAR is deeply democratic and seeks to empower participants, fostering a sense of agency and ownership. For instance, a participatory research project might involve local residents in studying and addressing community health concerns, ensuring that the research process and outcomes are both informed by and beneficial to the community itself.

Educational action research

Educational action research is tailored specifically to practical educational contexts. Here, educators take on the dual role of teacher and researcher, seeking to improve teaching practices, curricula, classroom dynamics, or educational evaluation. This type of research is cyclical, with educators implementing changes, observing outcomes, and reflecting on results to continually enhance the educational experience. An example might be a teacher studying the impact of technology integration in her classroom, adjusting strategies based on student feedback and learning outcomes.

Community-based action research

Another noteworthy type is community-based action research, which focuses primarily on community development and well-being. Rooted in the principles of social justice, this approach emphasizes the collective power of community members to identify, study, and address their challenges. It's particularly powerful in grassroots movements and local development projects where community insights and collaboration drive meaningful, sustainable change.

Key insights and critical reflection through research with ATLAS.ti

Organize all your data analysis and insights with our powerful interface. Download a free trial today.

Engaging in action research is both an enlightening and transformative journey, rooted in practicality yet deeply connected to theory. For those embarking on this path, understanding the essentials of an action research study and the significance of a research cycle is paramount.

Understanding the action research cycle

At the heart of action research is its cycle, a structured yet adaptable framework guiding the research. This cycle embodies the iterative nature of action research, emphasizing that learning and change evolve through repetition and reflection.

The typical stages include:

- Identifying a problem : This is the starting point where the action researcher pinpoints a pressing issue or challenge that demands attention.

- Planning : Here, the researcher devises an action research strategy aimed at addressing the identified problem. In action research, network resources, participant consultation, and the literature review are core components in planning.

- Action : The planned strategies are then implemented in this stage. This 'action' phase is where theoretical knowledge meets practical application.

- Observation : Post-implementation, the researcher observes the outcomes and effects of the action. This stage ensures that the research remains grounded in the real-world context.

- Critical reflection : This part of the cycle involves analyzing the observed results to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Revision : Based on the insights from reflection, the initial plan is revised, marking the beginning of another cycle.

Rigorous research and iteration

It's essential to understand that while action research is deeply practical, it doesn't sacrifice rigor . The cyclical process ensures that the research remains thorough and robust. Each iteration of the cycle in an action research project refines the approach, drawing it closer to an effective solution.

The role of the action researcher

The action researcher stands at the nexus of theory and practice. Not just an observer, the researcher actively engages with the study's participants, collaboratively navigating through the research cycle by conducting interviews, participant observations, and member checking . This close involvement ensures that the study remains relevant, timely, and responsive.

Drawing conclusions and informing theory

As the research progresses through multiple iterations of data collection and data analysis , drawing conclusions becomes an integral aspect. These conclusions, while immediately beneficial in addressing the practical issue at hand, also serve a broader purpose. They inform theory, enriching the academic discourse and providing valuable insights for future research.

Identifying actionable insights

Keep in mind that action research should facilitate implications for professional practice as well as space for systematic inquiry. As you draw conclusions about the knowledge generated from action research, consider how this knowledge can create new forms of solutions to the pressing concern you set out to address.

Collecting data and analyzing data starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of our intuitive software to make the most of your research.

the encyclopaedia of pedagogy and informal education

What is action research and how do we do it?

In this article, we explore the development of some different traditions of action research and provide an introductory guide to the literature., contents : what is action research · origins · the decline and rediscovery of action research · undertaking action research · conclusion · further reading · how to cite this article . see, also: research for practice ..

In the literature, discussion of action research tends to fall into two distinctive camps. The British tradition – especially that linked to education – tends to view action research as research-oriented toward the enhancement of direct practice. For example, Carr and Kemmis provide a classic definition:

Action research is simply a form of self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out (Carr and Kemmis 1986: 162).

Many people are drawn to this understanding of action research because it is firmly located in the realm of the practitioner – it is tied to self-reflection. As a way of working it is very close to the notion of reflective practice coined by Donald Schön (1983).

The second tradition, perhaps more widely approached within the social welfare field – and most certainly the broader understanding in the USA is of action research as ‘the systematic collection of information that is designed to bring about social change’ (Bogdan and Biklen 1992: 223). Bogdan and Biklen continue by saying that its practitioners marshal evidence or data to expose unjust practices or environmental dangers and recommend actions for change. In many respects, for them, it is linked into traditions of citizen’s action and community organizing. The practitioner is actively involved in the cause for which the research is conducted. For others, it is such commitment is a necessary part of being a practitioner or member of a community of practice. Thus, various projects designed to enhance practice within youth work, for example, such as the detached work reported on by Goetschius and Tash (1967) could be talked of as action research.

Kurt Lewin is generally credited as the person who coined the term ‘action research’:

The research needed for social practice can best be characterized as research for social management or social engineering. It is a type of action-research, a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action, and research leading to social action. Research that produces nothing but books will not suffice (Lewin 1946, reproduced in Lewin 1948: 202-3)

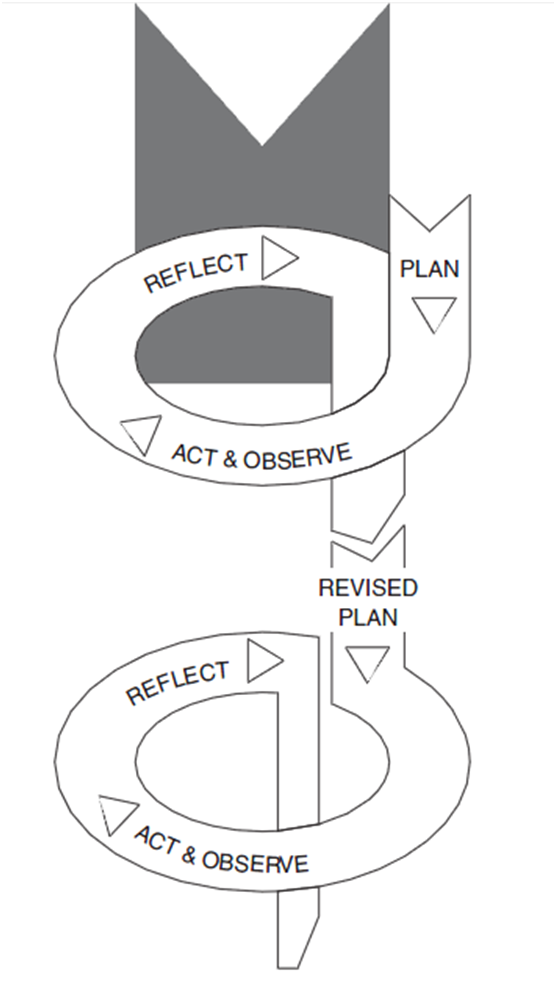

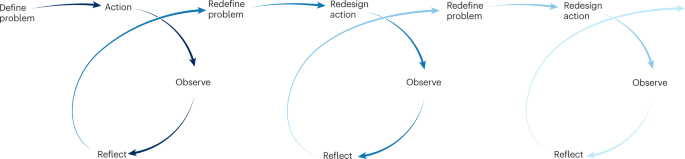

His approach involves a spiral of steps, ‘each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action and fact-finding about the result of the action’ ( ibid. : 206). The basic cycle involves the following:

This is how Lewin describes the initial cycle:

The first step then is to examine the idea carefully in the light of the means available. Frequently more fact-finding about the situation is required. If this first period of planning is successful, two items emerge: namely, “an overall plan” of how to reach the objective and secondly, a decision in regard to the first step of action. Usually this planning has also somewhat modified the original idea. ( ibid. : 205)

The next step is ‘composed of a circle of planning, executing, and reconnaissance or fact-finding for the purpose of evaluating the results of the second step, and preparing the rational basis for planning the third step, and for perhaps modifying again the overall plan’ ( ibid. : 206). What we can see here is an approach to research that is oriented to problem-solving in social and organizational settings, and that has a form that parallels Dewey’s conception of learning from experience.

The approach, as presented, does take a fairly sequential form – and it is open to a literal interpretation. Following it can lead to practice that is ‘correct’ rather than ‘good’ – as we will see. It can also be argued that the model itself places insufficient emphasis on analysis at key points. Elliott (1991: 70), for example, believed that the basic model allows those who use it to assume that the ‘general idea’ can be fixed in advance, ‘that “reconnaissance” is merely fact-finding, and that “implementation” is a fairly straightforward process’. As might be expected there was some questioning as to whether this was ‘real’ research. There were questions around action research’s partisan nature – the fact that it served particular causes.

The decline and rediscovery of action research

Action research did suffer a decline in favour during the 1960s because of its association with radical political activism (Stringer 2007: 9). There were, and are, questions concerning its rigour, and the training of those undertaking it. However, as Bogdan and Biklen (1992: 223) point out, research is a frame of mind – ‘a perspective that people take toward objects and activities’. Once we have satisfied ourselves that the collection of information is systematic and that any interpretations made have a proper regard for satisfying truth claims, then much of the critique aimed at action research disappears. In some of Lewin’s earlier work on action research (e.g. Lewin and Grabbe 1945), there was a tension between providing a rational basis for change through research, and the recognition that individuals are constrained in their ability to change by their cultural and social perceptions, and the systems of which they are a part. Having ‘correct knowledge’ does not of itself lead to change, attention also needs to be paid to the ‘matrix of cultural and psychic forces’ through which the subject is constituted (Winter 1987: 48).

Subsequently, action research has gained a significant foothold both within the realm of community-based, and participatory action research; and as a form of practice-oriented to the improvement of educative encounters (e.g. Carr and Kemmis 1986).

Exhibit 1: Stringer on community-based action research

A fundamental premise of community-based action research is that it commences with an interest in the problems of a group, a community, or an organization. Its purpose is to assist people in extending their understanding of their situation and thus resolving problems that confront them….

Community-based action research is always enacted through an explicit set of social values. In modern, democratic social contexts, it is seen as a process of inquiry that has the following characteristics:

• It is democratic , enabling the participation of all people.

• It is equitable , acknowledging people’s equality of worth.

• It is liberating , providing freedom from oppressive, debilitating conditions.

• It is life enhancing , enabling the expression of people’s full human potential.

(Stringer 1999: 9-10)

Undertaking action research

As Thomas (2017: 154) put it, the central aim is change, ‘and the emphasis is on problem-solving in whatever way is appropriate’. It can be seen as a conversation rather more than a technique (McNiff et. al. ). It is about people ‘thinking for themselves and making their own choices, asking themselves what they should do and accepting the consequences of their own actions’ (Thomas 2009: 113).

The action research process works through three basic phases:

Look -building a picture and gathering information. When evaluating we define and describe the problem to be investigated and the context in which it is set. We also describe what all the participants (educators, group members, managers etc.) have been doing.

Think – interpreting and explaining. When evaluating we analyse and interpret the situation. We reflect on what participants have been doing. We look at areas of success and any deficiencies, issues or problems.

Act – resolving issues and problems. In evaluation we judge the worth, effectiveness, appropriateness, and outcomes of those activities. We act to formulate solutions to any problems. (Stringer 1999: 18; 43-44;160)

The use of action research to deepen and develop classroom practice has grown into a strong tradition of practice (one of the first examples being the work of Stephen Corey in 1949). For some, there is an insistence that action research must be collaborative and entail groupwork.

Action research is a form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own social or educational practices, as well as their understanding of those practices and the situations in which the practices are carried out… The approach is only action research when it is collaborative, though it is important to realise that action research of the group is achieved through the critically examined action of individual group members. (Kemmis and McTaggart 1988: 5-6)

Just why it must be collective is open to some question and debate (Webb 1996), but there is an important point here concerning the commitments and orientations of those involved in action research.

One of the legacies Kurt Lewin left us is the ‘action research spiral’ – and with it there is the danger that action research becomes little more than a procedure. It is a mistake, according to McTaggart (1996: 248) to think that following the action research spiral constitutes ‘doing action research’. He continues, ‘Action research is not a ‘method’ or a ‘procedure’ for research but a series of commitments to observe and problematize through practice a series of principles for conducting social enquiry’. It is his argument that Lewin has been misunderstood or, rather, misused. When set in historical context, while Lewin does talk about action research as a method, he is stressing a contrast between this form of interpretative practice and more traditional empirical-analytic research. The notion of a spiral may be a useful teaching device – but it is all too easy to slip into using it as the template for practice (McTaggart 1996: 249).

Further reading

This select, annotated bibliography has been designed to give a flavour of the possibilities of action research and includes some useful guides to practice. As ever, if you have suggestions about areas or specific texts for inclusion, I’d like to hear from you.

Explorations of action research

Atweh, B., Kemmis, S. and Weeks, P. (eds.) (1998) Action Research in Practice: Partnership for Social Justice in Education, London: Routledge. Presents a collection of stories from action research projects in schools and a university. The book begins with theme chapters discussing action research, social justice and partnerships in research. The case study chapters cover topics such as: school environment – how to make a school a healthier place to be; parents – how to involve them more in decision-making; students as action researchers; gender – how to promote gender equity in schools; writing up action research projects.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986) Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research , Lewes: Falmer. Influential book that provides a good account of ‘action research’ in education. Chapters on teachers, researchers and curriculum; the natural scientific view of educational theory and practice; the interpretative view of educational theory and practice; theory and practice – redefining the problem; a critical approach to theory and practice; towards a critical educational science; action research as critical education science; educational research, educational reform and the role of the profession.

Carson, T. R. and Sumara, D. J. (ed.) (1997) Action Research as a Living Practice , New York: Peter Lang. 140 pages. Book draws on a wide range of sources to develop an understanding of action research. Explores action research as a lived practice, ‘that asks the researcher to not only investigate the subject at hand but, as well, to provide some account of the way in which the investigation both shapes and is shaped by the investigator.

Dadds, M. (1995) Passionate Enquiry and School Development. A story about action research , London: Falmer. 192 + ix pages. Examines three action research studies undertaken by a teacher and how they related to work in school – how she did the research, the problems she experienced, her feelings, the impact on her feelings and ideas, and some of the outcomes. In his introduction, John Elliot comments that the book is ‘the most readable, thoughtful, and detailed study of the potential of action-research in professional education that I have read’.

Ghaye, T. and Wakefield, P. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book one: the role of the self in action , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 146 + xiii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: dialectical forms; graduate medical education – research’s outer limits; democratic education; managing action research; writing up.

McNiff, J. (1993) Teaching as Learning: An Action Research Approach , London: Routledge. Argues that educational knowledge is created by individual teachers as they attempt to express their own values in their professional lives. Sets out familiar action research model: identifying a problem, devising, implementing and evaluating a solution and modifying practice. Includes advice on how working in this way can aid the professional development of action researcher and practitioner.

Quigley, B. A. and Kuhne, G. W. (eds.) (1997) Creating Practical Knowledge Through Action Research, San Fransisco: Jossey Bass. Guide to action research that outlines the action research process, provides a project planner, and presents examples to show how action research can yield improvements in six different settings, including a hospital, a university and a literacy education program.

Plummer, G. and Edwards, G. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book two: dimensions of action research – people, practice and power , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 142 + xvii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: exchanging letters and collaborative research; diary writing; personal and professional learning – on teaching and self-knowledge; anti-racist approaches; psychodynamic group theory in action research.

Whyte, W. F. (ed.) (1991) Participatory Action Research , Newbury Park: Sage. 247 pages. Chapters explore the development of participatory action research and its relation with action science and examine its usages in various agricultural and industrial settings

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed.) (1996) New Directions in Action Research , London; Falmer Press. 266 + xii pages. A useful collection that explores principles and procedures for critical action research; problems and suggested solutions; and postmodernism and critical action research.

Action research guides

Coghlan, D. and Brannick, D. (2000) Doing Action Research in your own Organization, London: Sage. 128 pages. Popular introduction. Part one covers the basics of action research including the action research cycle, the role of the ‘insider’ action researcher and the complexities of undertaking action research within your own organisation. Part two looks at the implementation of the action research project (including managing internal politics and the ethics and politics of action research). New edition due late 2004.

Elliot, J. (1991) Action Research for Educational Change , Buckingham: Open University Press. 163 + x pages Collection of various articles written by Elliot in which he develops his own particular interpretation of action research as a form of teacher professional development. In some ways close to a form of ‘reflective practice’. Chapter 6, ‘A practical guide to action research’ – builds a staged model on Lewin’s work and on developments by writers such as Kemmis.

Johnson, A. P. (2007) A short guide to action research 3e. Allyn and Bacon. Popular step by step guide for master’s work.

Macintyre, C. (2002) The Art of the Action Research in the Classroom , London: David Fulton. 138 pages. Includes sections on action research, the role of literature, formulating a research question, gathering data, analysing data and writing a dissertation. Useful and readable guide for students.

McNiff, J., Whitehead, J., Lomax, P. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project , London: Routledge. Practical guidance on doing an action research project.Takes the practitioner-researcher through the various stages of a project. Each section of the book is supported by case studies

Stringer, E. T. (2007) Action Research: A handbook for practitioners 3e , Newbury Park, ca.: Sage. 304 pages. Sets community-based action research in context and develops a model. Chapters on information gathering, interpretation, resolving issues; legitimacy etc. See, also Stringer’s (2003) Action Research in Education , Prentice-Hall.

Winter, R. (1989) Learning From Experience. Principles and practice in action research , Lewes: Falmer Press. 200 + 10 pages. Introduces the idea of action research; the basic process; theoretical issues; and provides six principles for the conduct of action research. Includes examples of action research. Further chapters on from principles to practice; the learner’s experience; and research topics and personal interests.

Action research in informal education

Usher, R., Bryant, I. and Johnston, R. (1997) Adult Education and the Postmodern Challenge. Learning beyond the limits , London: Routledge. 248 + xvi pages. Has some interesting chapters that relate to action research: on reflective practice; changing paradigms and traditions of research; new approaches to research; writing and learning about research.

Other references

Bogdan, R. and Biklen, S. K. (1992) Qualitative Research For Education , Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Goetschius, G. and Tash, J. (1967) Working with the Unattached , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

McTaggart, R. (1996) ‘Issues for participatory action researchers’ in O. Zuber-Skerritt (ed.) New Directions in Action Research , London: Falmer Press.

McNiff, J., Lomax, P. and Whitehead, J. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project 2e. London: Routledge.

Thomas, G. (2017). How to do your Research Project. A guide for students in education and applied social sciences . 3e. London: Sage.

Acknowledgements : spiral by Michèle C. | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence

How to cite this article : Smith, M. K. (1996; 2001, 2007, 2017) What is action research and how do we do it?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [ https://infed.org/mobi/action-research/ . Retrieved: insert date] .

© Mark K. Smith 1996; 2001, 2007, 2017

Created by the Great Schools Partnership , the GLOSSARY OF EDUCATION REFORM is a comprehensive online resource that describes widely used school-improvement terms, concepts, and strategies for journalists, parents, and community members. | Learn more »

Action Research

In schools, action research refers to a wide variety of evaluative, investigative, and analytical research methods designed to diagnose problems or weaknesses—whether organizational, academic, or instructional—and help educators develop practical solutions to address them quickly and efficiently. Action research may also be applied to programs or educational techniques that are not necessarily experiencing any problems, but that educators simply want to learn more about and improve. The general goal is to create a simple, practical, repeatable process of iterative learning, evaluation, and improvement that leads to increasingly better results for schools, teachers, or programs.

Action research may also be called a cycle of action or cycle of inquiry , since it typically follows a predefined process that is repeated over time. A simple illustrative example:

- Identify a problem to be studied

- Collect data on the problem

- Organize, analyze, and interpret the data

- Develop a plan to address the problem

- Implement the plan

- Evaluate the results of the actions taken

- Identify a new problem

- Repeat the process

Unlike more formal research studies, such as those conducted by universities and published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals, action research is typically conducted by the educators working in the district or school being studied—the participants—rather than by independent, impartial observers from outside organizations. Less formal, prescriptive, or theory-driven research methods are typically used when conducting action research, since the goal is to address practical problems in a specific school or classroom, rather than produce independently validated and reproducible findings that others, outside of the context being studied, can use to guide their future actions or inform the design of their academic programs. That said, while action research is typically focused on solving a specific problem (high rates of student absenteeism, for example) or answer a specific question (Why are so many of our ninth graders failing math?), action research can also make meaningful contributions to the larger body of knowledge and understanding in the field of education, particularly within a relatively closed system such as school, district, or network of connected organizations.

The term “action research” was coined in the 1940s by Kurt Lewin, a German-American social psychologist who is widely considered to be the founder of his field. The basic principles of action research that were described by Lewin are still in use to this day.

Educators typically conduct action research as an extension of a particular school-improvement plan, project, or goal—i.e., action research is nearly always a school-reform strategy. The object of action research could be almost anything related to educational performance or improvement, from the effectiveness of certain teaching strategies and lesson designs to the influence that family background has on student performance to the results achieved by a particular academic support strategy or learning program—to list just a small sampling.

For related discussions, see action plan , capacity , continuous improvement , evidence-based , and professional development .

Alphabetical Search

Main Navigation Menu

Action research.

- Getting Started

- Finding Action Research Studies

- Bibliography & Additional Resources

Subject Librarian

What is Action Research?

Action research involves a systematic process of examining the evidence. The results of this type of research are practical, relevant, and can inform theory. Action research is different than other forms of research as there is less concern for universality of findings, and more value is placed on the relevance of the findings to the researcher and the local collaborators.

Riel, M. (2020). Understanding action research. Center For Collaborative Action Research, Pepperdine University. Retrieved January 31, 2021 from the Center for Collaborative Action Research. https://www.actionresearchtutorials.org/

-----------------------------------

The short video below by John Spencer provides a quick overview of Action Research.

How is Action Research different?

This chart demonstrates the difference between traditional research and action research. Traditional research is a means to an end - the conclusion. They start with a theory, statistical analysis is critical and the researcher does not insert herself into the research.

Action research is often practiced by practitioners like teachers and librarians who remain in the middle of the research process. They are looking for ways to improve the specific situation for their clientele or students. Statistics may be collected but they are not the point of the research.

Adapted from: Mc Millan, J. H. & Wergin. J. F. (1998). Understanding and evaluating educational research. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Next: Finding Action Research Studies >>

- Last Updated: Aug 26, 2024 12:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucmo.edu/actionresearch

Action Research

Action research can be defined as “an approach in which the action researcher and a client collaborate in the diagnosis of the problem and in the development of a solution based on the diagnosis” [1] . In other words, one of the main characteristic traits of action research relates to collaboration between researcher and member of organisation in order to solve organizational problems.

Action study assumes social world to be constantly changing, both, researcher and research being one part of that change. [2] Generally, action researches can be divided into three categories: positivist, interpretive and critical.

Positivist approach to action research , also known as ‘classical action research’ perceives research as a social experiment. Accordingly, action research is accepted as a method to test hypotheses in a real world environment.

Interpretive action research , also known as ‘contemporary action research’ perceives business reality as socially constructed and focuses on specifications of local and organisational factors when conducting the action research.

Critical action research is a specific type of action research that adopts critical approach towards business processes and aims for improvements.

The following features of action research need to be taken into account when considering its suitability for any given study:

- It is applied in order to improve specific practices. Action research is based on action, evaluation and critical analysis of practices based on collected data in order to introduce improvements in relevant practices.

- This type of research is facilitated by participation and collaboration of number of individuals with a common purpose

- Such a research focuses on specific situations and their context

Advantages of Action Research

- High level of practical relevance of the business research;

- Can be used with quantitative, as well as, qualitative data;

- Possibility to gain in-depth knowledge about the problem.

Disadvantages of Action Research

- Difficulties in distinguishing between action and research and ensure the application of both;

- Delays in completion of action research due to a wide range of reasons are not rare occurrences

- Lack of repeatability and rigour

It is important to make a clear distinction between action research and consulting. Specifically, action research is greater than consulting in a way that action research includes both action and research, whereas business activities of consulting are limited action without the research.

Action Research Spiral

Action study is a participatory study consisting of spiral of following self-reflective cycles:

- Planning in order to initiate change

- Implementing the change (acting) and observing the process of implementation and consequences

- Reflecting on processes of change and re-planning

- Acting and observing

Kemmis and McTaggart (2000) do acknowledge that individual stages specified in Action Research Spiral model may overlap, and initial plan developed for the research may become obselete in short duration of time due to a range of factors.

The main advantage of Action Research Spiral model relates to the opportunity of analysing the phenomenon in a greater depth each time, consequently resulting in grater level of understanding of the problem.

Disadvantages of Action Research Spiral model include its assumption each process takes long time to be completed which may not always be the case.

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance offers practical assistance to complete a dissertation with minimum or no stress. The e-book covers all stages of writing a dissertation starting from the selection to the research area to submitting the completed version of the work within the deadline.

References

[1] Bryman, A. & Bell, E. (2011) “Business Research Methods” 3 rd edition, Oxford University Press

[2] Collis, J. & Hussey, R. (2003) “Business Research. A Practical Guide for Undergraduate and Graduate Students” 2nd edition, Palgrave Macmillan

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What is Action Research for Classroom Teachers?

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is the nature of action research?

- How does action research develop in the classroom?

- What models of action research work best for your classroom?

- What are the epistemological, ontological, theoretical underpinnings of action research?

Educational research provides a vast landscape of knowledge on topics related to teaching and learning, curriculum and assessment, students’ cognitive and affective needs, cultural and socio-economic factors of schools, and many other factors considered viable to improving schools. Educational stakeholders rely on research to make informed decisions that ultimately affect the quality of schooling for their students. Accordingly, the purpose of educational research is to engage in disciplined inquiry to generate knowledge on topics significant to the students, teachers, administrators, schools, and other educational stakeholders. Just as the topics of educational research vary, so do the approaches to conducting educational research in the classroom. Your approach to research will be shaped by your context, your professional identity, and paradigm (set of beliefs and assumptions that guide your inquiry). These will all be key factors in how you generate knowledge related to your work as an educator.

Action research is an approach to educational research that is commonly used by educational practitioners and professionals to examine, and ultimately improve, their pedagogy and practice. In this way, action research represents an extension of the reflection and critical self-reflection that an educator employs on a daily basis in their classroom. When students are actively engaged in learning, the classroom can be dynamic and uncertain, demanding the constant attention of the educator. Considering these demands, educators are often only able to engage in reflection that is fleeting, and for the purpose of accommodation, modification, or formative assessment. Action research offers one path to more deliberate, substantial, and critical reflection that can be documented and analyzed to improve an educator’s practice.

Purpose of Action Research

As one of many approaches to educational research, it is important to distinguish the potential purposes of action research in the classroom. This book focuses on action research as a method to enable and support educators in pursuing effective pedagogical practices by transforming the quality of teaching decisions and actions, to subsequently enhance student engagement and learning. Being mindful of this purpose, the following aspects of action research are important to consider as you contemplate and engage with action research methodology in your classroom:

- Action research is a process for improving educational practice. Its methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices.

- Action research is participative and collaborative. It is undertaken by individuals with a common purpose.

- Action research is situation and context-based.

- Action research develops reflection practices based on the interpretations made by participants.

- Knowledge is created through action and application.

- Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice.

- Action research is iterative; plans are created, implemented, revised, then implemented, lending itself to an ongoing process of reflection and revision.

- In action research, findings emerge as action develops and takes place; however, they are not conclusive or absolute, but ongoing (Koshy, 2010, pgs. 1-2).

In thinking about the purpose of action research, it is helpful to situate action research as a distinct paradigm of educational research. I like to think about action research as part of the larger concept of living knowledge. Living knowledge has been characterized as “a quest for life, to understand life and to create… knowledge which is valid for the people with whom I work and for myself” (Swantz, in Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 1). Why should educators care about living knowledge as part of educational research? As mentioned above, action research is meant “to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in the everyday conduct of their lives and to see that action research is about working towards practical outcomes” (Koshy, 2010, pg. 2). However, it is also about:

creating new forms of understanding, since action without reflection and understanding is blind, just as theory without action is meaningless. The participatory nature of action research makes it only possible with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sense making that informs the research, and in the action, which is its focus. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 2)

In an effort to further situate action research as living knowledge, Jean McNiff reminds us that “there is no such ‘thing’ as ‘action research’” (2013, pg. 24). In other words, action research is not static or finished, it defines itself as it proceeds. McNiff’s reminder characterizes action research as action-oriented, and a process that individuals go through to make their learning public to explain how it informs their practice. Action research does not derive its meaning from an abstract idea, or a self-contained discovery – action research’s meaning stems from the way educators negotiate the problems and successes of living and working in the classroom, school, and community.

While we can debate the idea of action research, there are people who are action researchers, and they use the idea of action research to develop principles and theories to guide their practice. Action research, then, refers to an organization of principles that guide action researchers as they act on shared beliefs, commitments, and expectations in their inquiry.

Reflection and the Process of Action Research

When an individual engages in reflection on their actions or experiences, it is typically for the purpose of better understanding those experiences, or the consequences of those actions to improve related action and experiences in the future. Reflection in this way develops knowledge around these actions and experiences to help us better regulate those actions in the future. The reflective process generates new knowledge regularly for classroom teachers and informs their classroom actions.

Unfortunately, the knowledge generated by educators through the reflective process is not always prioritized among the other sources of knowledge educators are expected to utilize in the classroom. Educators are expected to draw upon formal types of knowledge, such as textbooks, content standards, teaching standards, district curriculum and behavioral programs, etc., to gain new knowledge and make decisions in the classroom. While these forms of knowledge are important, the reflective knowledge that educators generate through their pedagogy is the amalgamation of these types of knowledge enacted in the classroom. Therefore, reflective knowledge is uniquely developed based on the action and implementation of an educator’s pedagogy in the classroom. Action research offers a way to formalize the knowledge generated by educators so that it can be utilized and disseminated throughout the teaching profession.

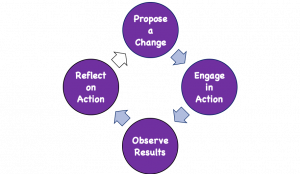

Research is concerned with the generation of knowledge, and typically creating knowledge related to a concept, idea, phenomenon, or topic. Action research generates knowledge around inquiry in practical educational contexts. Action research allows educators to learn through their actions with the purpose of developing personally or professionally. Due to its participatory nature, the process of action research is also distinct in educational research. There are many models for how the action research process takes shape. I will share a few of those here. Each model utilizes the following processes to some extent:

- Plan a change;

- Take action to enact the change;

- Observe the process and consequences of the change;

- Reflect on the process and consequences;

- Act, observe, & reflect again and so on.

Figure 1.1 Basic action research cycle

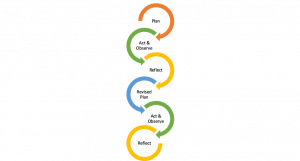

There are many other models that supplement the basic process of action research with other aspects of the research process to consider. For example, figure 1.2 illustrates a spiral model of action research proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2004). The spiral model emphasizes the cyclical process that moves beyond the initial plan for change. The spiral model also emphasizes revisiting the initial plan and revising based on the initial cycle of research:

Figure 1.2 Interpretation of action research spiral, Kemmis and McTaggart (2004, p. 595)

Other models of action research reorganize the process to emphasize the distinct ways knowledge takes shape in the reflection process. O’Leary’s (2004, p. 141) model, for example, recognizes that the research may take shape in the classroom as knowledge emerges from the teacher’s observations. O’Leary highlights the need for action research to be focused on situational understanding and implementation of action, initiated organically from real-time issues:

Figure 1.3 Interpretation of O’Leary’s cycles of research, O’Leary (2000, p. 141)

Lastly, Macintyre’s (2000, p. 1) model, offers a different characterization of the action research process. Macintyre emphasizes a messier process of research with the initial reflections and conclusions as the benchmarks for guiding the research process. Macintyre emphasizes the flexibility in planning, acting, and observing stages to allow the process to be naturalistic. Our interpretation of Macintyre process is below:

Figure 1.4 Interpretation of the action research cycle, Macintyre (2000, p. 1)

We believe it is important to prioritize the flexibility of the process, and encourage you to only use these models as basic guides for your process. Your process may look similar, or you may diverge from these models as you better understand your students, context, and data.

Definitions of Action Research and Examples

At this point, it may be helpful for readers to have a working definition of action research and some examples to illustrate the methodology in the classroom. Bassey (1998, p. 93) offers a very practical definition and describes “action research as an inquiry which is carried out in order to understand, to evaluate and then to change, in order to improve educational practice.” Cohen and Manion (1994, p. 192) situate action research differently, and describe action research as emergent, writing:

essentially an on-the-spot procedure designed to deal with a concrete problem located in an immediate situation. This means that ideally, the step-by-step process is constantly monitored over varying periods of time and by a variety of mechanisms (questionnaires, diaries, interviews and case studies, for example) so that the ensuing feedback may be translated into modifications, adjustment, directional changes, redefinitions, as necessary, so as to bring about lasting benefit to the ongoing process itself rather than to some future occasion.

Lastly, Koshy (2010, p. 9) describes action research as:

a constructive inquiry, during which the researcher constructs his or her knowledge of specific issues through planning, acting, evaluating, refining and learning from the experience. It is a continuous learning process in which the researcher learns and also shares the newly generated knowledge with those who may benefit from it.

These definitions highlight the distinct features of action research and emphasize the purposeful intent of action researchers to improve, refine, reform, and problem-solve issues in their educational context. To better understand the distinctness of action research, these are some examples of action research topics:

Examples of Action Research Topics

- Flexible seating in 4th grade classroom to increase effective collaborative learning.

- Structured homework protocols for increasing student achievement.

- Developing a system of formative feedback for 8th grade writing.

- Using music to stimulate creative writing.

- Weekly brown bag lunch sessions to improve responses to PD from staff.

- Using exercise balls as chairs for better classroom management.

Action Research in Theory

Action research-based inquiry in educational contexts and classrooms involves distinct participants – students, teachers, and other educational stakeholders within the system. All of these participants are engaged in activities to benefit the students, and subsequently society as a whole. Action research contributes to these activities and potentially enhances the participants’ roles in the education system. Participants’ roles are enhanced based on two underlying principles:

- communities, schools, and classrooms are sites of socially mediated actions, and action research provides a greater understanding of self and new knowledge of how to negotiate these socially mediated environments;

- communities, schools, and classrooms are part of social systems in which humans interact with many cultural tools, and action research provides a basis to construct and analyze these interactions.

In our quest for knowledge and understanding, we have consistently analyzed human experience over time and have distinguished between types of reality. Humans have constantly sought “facts” and “truth” about reality that can be empirically demonstrated or observed.

Social systems are based on beliefs, and generally, beliefs about what will benefit the greatest amount of people in that society. Beliefs, and more specifically the rationale or support for beliefs, are not always easy to demonstrate or observe as part of our reality. Take the example of an English Language Arts teacher who prioritizes argumentative writing in her class. She believes that argumentative writing demonstrates the mechanics of writing best among types of writing, while also providing students a skill they will need as citizens and professionals. While we can observe the students writing, and we can assess their ability to develop a written argument, it is difficult to observe the students’ understanding of argumentative writing and its purpose in their future. This relates to the teacher’s beliefs about argumentative writing; we cannot observe the real value of the teaching of argumentative writing. The teacher’s rationale and beliefs about teaching argumentative writing are bound to the social system and the skills their students will need to be active parts of that system. Therefore, our goal through action research is to demonstrate the best ways to teach argumentative writing to help all participants understand its value as part of a social system.

The knowledge that is conveyed in a classroom is bound to, and justified by, a social system. A postmodernist approach to understanding our world seeks knowledge within a social system, which is directly opposed to the empirical or positivist approach which demands evidence based on logic or science as rationale for beliefs. Action research does not rely on a positivist viewpoint to develop evidence and conclusions as part of the research process. Action research offers a postmodernist stance to epistemology (theory of knowledge) and supports developing questions and new inquiries during the research process. In this way action research is an emergent process that allows beliefs and decisions to be negotiated as reality and meaning are being constructed in the socially mediated space of the classroom.

Theorizing Action Research for the Classroom

All research, at its core, is for the purpose of generating new knowledge and contributing to the knowledge base of educational research. Action researchers in the classroom want to explore methods of improving their pedagogy and practice. The starting place of their inquiry stems from their pedagogy and practice, so by nature the knowledge created from their inquiry is often contextually specific to their classroom, school, or community. Therefore, we should examine the theoretical underpinnings of action research for the classroom. It is important to connect action research conceptually to experience; for example, Levin and Greenwood (2001, p. 105) make these connections:

- Action research is context bound and addresses real life problems.

- Action research is inquiry where participants and researchers cogenerate knowledge through collaborative communicative processes in which all participants’ contributions are taken seriously.

- The meanings constructed in the inquiry process lead to social action or these reflections and action lead to the construction of new meanings.

- The credibility/validity of action research knowledge is measured according to whether the actions that arise from it solve problems (workability) and increase participants’ control over their own situation.

Educators who engage in action research will generate new knowledge and beliefs based on their experiences in the classroom. Let us emphasize that these are all important to you and your work, as both an educator and researcher. It is these experiences, beliefs, and theories that are often discounted when more official forms of knowledge (e.g., textbooks, curriculum standards, districts standards) are prioritized. These beliefs and theories based on experiences should be valued and explored further, and this is one of the primary purposes of action research in the classroom. These beliefs and theories should be valued because they were meaningful aspects of knowledge constructed from teachers’ experiences. Developing meaning and knowledge in this way forms the basis of constructivist ideology, just as teachers often try to get their students to construct their own meanings and understandings when experiencing new ideas.

Classroom Teachers Constructing their Own Knowledge

Most of you are probably at least minimally familiar with constructivism, or the process of constructing knowledge. However, what is constructivism precisely, for the purposes of action research? Many scholars have theorized constructivism and have identified two key attributes (Koshy, 2010; von Glasersfeld, 1987):

- Knowledge is not passively received, but actively developed through an individual’s cognition;

- Human cognition is adaptive and finds purpose in organizing the new experiences of the world, instead of settling for absolute or objective truth.