Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Essay Writing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource begins with a general description of essay writing and moves to a discussion of common essay genres students may encounter across the curriculum. The four genres of essays (description, narration, exposition, and argumentation) are common paper assignments you may encounter in your writing classes. Although these genres, also known as the modes of discourse, have been criticized by some composition scholars, the Purdue OWL recognizes the wide spread use of these genres and students’ need to understand and produce these types of essays. We hope these resources will help.

The essay is a commonly assigned form of writing that every student will encounter while in academia. Therefore, it is wise for the student to become capable and comfortable with this type of writing early on in her training.

Essays can be a rewarding and challenging type of writing and are often assigned either to be done in class, which requires previous planning and practice (and a bit of creativity) on the part of the student, or as homework, which likewise demands a certain amount of preparation. Many poorly crafted essays have been produced on account of a lack of preparation and confidence. However, students can avoid the discomfort often associated with essay writing by understanding some common genres.

Before delving into its various genres, let’s begin with a basic definition of the essay.

What is an essay?

Though the word essay has come to be understood as a type of writing in Modern English, its origins provide us with some useful insights. The word comes into the English language through the French influence on Middle English; tracing it back further, we find that the French form of the word comes from the Latin verb exigere , which means "to examine, test, or (literally) to drive out." Through the excavation of this ancient word, we are able to unearth the essence of the academic essay: to encourage students to test or examine their ideas concerning a particular topic.

Essays are shorter pieces of writing that often require the student to hone a number of skills such as close reading, analysis, comparison and contrast, persuasion, conciseness, clarity, and exposition. As is evidenced by this list of attributes, there is much to be gained by the student who strives to succeed at essay writing.

The purpose of an essay is to encourage students to develop ideas and concepts in their writing with the direction of little more than their own thoughts (it may be helpful to view the essay as the converse of a research paper). Therefore, essays are (by nature) concise and require clarity in purpose and direction. This means that there is no room for the student’s thoughts to wander or stray from his or her purpose; the writing must be deliberate and interesting.

This handout should help students become familiar and comfortable with the process of essay composition through the introduction of some common essay genres.

This handout includes a brief introduction to the following genres of essay writing:

- Expository essays

- Descriptive essays

- Narrative essays

- Argumentative (Persuasive) essays

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 2009 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 42,469 quotes across 2009 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

Would you like to explore a topic?

- LEARNING OUTSIDE OF SCHOOL

Or read some of our popular articles?

Free downloadable english gcse past papers with mark scheme.

- 19 May 2022

The Best Free Homeschooling Resources UK Parents Need to Start Using Today

- Joseph McCrossan

- 18 February 2022

How Will GCSE Grade Boundaries Affect My Child’s Results?

- Akshat Biyani

- 13 December 2021

How to Write the Perfect Essay: A Step-By-Step Guide for Students

- June 2, 2022

- What is an essay?

What makes a good essay?

Typical essay structure, 7 steps to writing a good essay, a step-by-step guide to writing a good essay.

Whether you are gearing up for your GCSE coursework submissions or looking to brush up on your A-level writing skills, we have the perfect essay-writing guide for you. 💯

Staring at a blank page before writing an essay can feel a little daunting . Where do you start? What should your introduction say? And how should you structure your arguments? They are all fair questions and we have the answers! Take the stress out of essay writing with this step-by-step guide – you’ll be typing away in no time. 👩💻

What is an essay?

Generally speaking, an essay designates a literary work in which the author defends a point of view or a personal conviction, using logical arguments and literary devices in order to inform and convince the reader.

So – although essays can be broadly split into four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive – an essay can simply be described as a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. 🤔

The purpose of an essay is to present a coherent argument in response to a stimulus or question and to persuade the reader that your position is credible, believable and reasonable. 👌

So, a ‘good’ essay relies on a confident writing style – it’s clear, well-substantiated, focussed, explanatory and descriptive . The structure follows a logical progression and above all, the body of the essay clearly correlates to the tile – answering the question where one has been posed.

But, how do you go about making sure that you tick all these boxes and keep within a specified word count? Read on for the answer as well as an example essay structure to follow and a handy step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay – hooray. 🙌

Sometimes, it is helpful to think about your essay like it is a well-balanced argument or a speech – it needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question in a coherent manner. ⚖️

Of course, essays can vary significantly in length but besides that, they all follow a fairly strict pattern or structure made up of three sections. Lean into this predictability because it will keep you on track and help you make your point clearly. Let’s take a look at the typical essay structure:

#1 Introduction

Start your introduction with the central claim of your essay. Let the reader know exactly what you intend to say with this essay. Communicate what you’re going to argue, and in what order. The final part of your introduction should also say what conclusions you’re going to draw – it sounds counter-intuitive but it’s not – more on that below. 1️⃣

Make your point, evidence it and explain it. This part of the essay – generally made up of three or more paragraphs depending on the length of your essay – is where you present your argument. The first sentence of each paragraph – much like an introduction to an essay – should summarise what your paragraph intends to explain in more detail. 2️⃣

#3 Conclusion

This is where you affirm your argument – remind the reader what you just proved in your essay and how you did it. This section will sound quite similar to your introduction but – having written the essay – you’ll be summarising rather than setting out your stall. 3️⃣

No essay is the same but your approach to writing them can be. As well as some best practice tips, we have gathered our favourite advice from expert essay-writers and compiled the following 7-step guide to writing a good essay every time. 👍

#1 Make sure you understand the question

#2 complete background reading.

#3 Make a detailed plan

#4 Write your opening sentences

#5 flesh out your essay in a rough draft, #6 evidence your opinion, #7 final proofread and edit.

Now that you have familiarised yourself with the 7 steps standing between you and the perfect essay, let’s take a closer look at each of those stages so that you can get on with crafting your written arguments with confidence .

This is the most crucial stage in essay writing – r ead the essay prompt carefully and understand the question. Highlight the keywords – like ‘compare,’ ‘contrast’ ‘discuss,’ ‘explain’ or ‘evaluate’ – and let it sink in before your mind starts racing . There is nothing worse than writing 500 words before realising you have entirely missed the brief . 🧐

Unless you are writing under exam conditions , you will most likely have been working towards this essay for some time, by doing thorough background reading. Re-read relevant chapters and sections, highlight pertinent material and maybe even stray outside the designated reading list, this shows genuine interest and extended knowledge. 📚

#3 Make a detailed plan

Following the handy structure we shared with you above, now is the time to create the ‘skeleton structure’ or essay plan. Working from your essay title, plot out what you want your paragraphs to cover and how that information is going to flow. You don’t need to start writing any full sentences yet but it might be useful to think about the various quotes you plan to use to substantiate each section. 📝

Having mapped out the overall trajectory of your essay, you can start to drill down into the detail. First, write the opening sentence for each of the paragraphs in the body section of your essay. Remember – each paragraph is like a mini-essay – the opening sentence should summarise what the paragraph will then go on to explain in more detail. 🖊️

Next, it's time to write the bulk of your words and flesh out your arguments. Follow the ‘point, evidence, explain’ method. The opening sentences – already written – should introduce your ‘points’, so now you need to ‘evidence’ them with corroborating research and ‘explain’ how the evidence you’ve presented proves the point you’re trying to make. ✍️

With a rough draft in front of you, you can take a moment to read what you have written so far. Are there any sections that require further substantiation? Have you managed to include the most relevant material you originally highlighted in your background reading? Now is the time to make sure you have evidenced all your opinions and claims with the strongest quotes, citations and material. 📗

This is your final chance to re-read your essay and go over it with a fine-toothed comb before pressing ‘submit’. We highly recommend leaving a day or two between finishing your essay and the final proofread if possible – you’ll be amazed at the difference this makes, allowing you to return with a fresh pair of eyes and a more discerning judgment. 🤓

If you are looking for advice and support with your own essay-writing adventures, why not t ry a free trial lesson with GoStudent? Our tutors are experts at boosting academic success and having fun along the way. Get in touch and see how it can work for you today. 🎒

Popular posts

- By Guy Doza

- By Joseph McCrossan

- In LEARNING TRENDS

- By Akshat Biyani

What are the Hardest GCSEs? Should You Avoid or Embrace Them?

- By Clarissa Joshua

4 Surprising Disadvantages of Homeschooling

- By Andrea Butler

Want to try tutoring? Request a free trial session with a top tutor.

More great reads:.

Benefits of Reading: Positive Impacts for All Ages Everyday

- May 26, 2023

15 of the Best Children's Books That Every Young Person Should Read

- By Sharlene Matharu

- March 2, 2023

Ultimate School Library Tips and Hacks

- By Natalie Lever

- March 1, 2023

Book a free trial session

Sign up for your free tutoring lesson..

Essay Papers Writing Online

Tips and tricks for crafting engaging and effective essays.

Writing essays can be a challenging task, but with the right approach and strategies, you can create compelling and impactful pieces that captivate your audience. Whether you’re a student working on an academic paper or a professional honing your writing skills, these tips will help you craft essays that stand out.

Effective essays are not just about conveying information; they are about persuading, engaging, and inspiring readers. To achieve this, it’s essential to pay attention to various elements of the essay-writing process, from brainstorming ideas to polishing your final draft. By following these tips, you can elevate your writing and produce essays that leave a lasting impression.

Understanding the Essay Prompt

Before you start writing your essay, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the essay prompt or question provided by your instructor. The essay prompt serves as a roadmap for your essay and outlines the specific requirements or expectations.

Here are a few key things to consider when analyzing the essay prompt:

- Read the prompt carefully and identify the main topic or question being asked.

- Pay attention to any specific instructions or guidelines provided, such as word count, formatting requirements, or sources to be used.

- Identify key terms or phrases in the prompt that can help you determine the focus of your essay.

By understanding the essay prompt thoroughly, you can ensure that your essay addresses the topic effectively and meets the requirements set forth by your instructor.

Researching Your Topic Thoroughly

One of the key elements of writing an effective essay is conducting thorough research on your chosen topic. Research helps you gather the necessary information, facts, and examples to support your arguments and make your essay more convincing.

Here are some tips for researching your topic thoroughly:

| Don’t rely on a single source for your research. Use a variety of sources such as books, academic journals, reliable websites, and primary sources to gather different perspectives and valuable information. | |

| While conducting research, make sure to take detailed notes of important information, quotes, and references. This will help you keep track of your sources and easily refer back to them when writing your essay. | |

| Before using any information in your essay, evaluate the credibility of the sources. Make sure they are reliable, up-to-date, and authoritative to strengthen the validity of your arguments. | |

| Organize your research materials in a systematic way to make it easier to access and refer to them while writing. Create an outline or a research plan to structure your essay effectively. |

By following these tips and conducting thorough research on your topic, you will be able to write a well-informed and persuasive essay that effectively communicates your ideas and arguments.

Creating a Strong Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a crucial element of any well-crafted essay. It serves as the main point or idea that you will be discussing and supporting throughout your paper. A strong thesis statement should be clear, specific, and arguable.

To create a strong thesis statement, follow these tips:

- Be specific: Your thesis statement should clearly state the main idea of your essay. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Be concise: Keep your thesis statement concise and to the point. Avoid unnecessary details or lengthy explanations.

- Be argumentative: Your thesis statement should present an argument or perspective that can be debated or discussed in your essay.

- Be relevant: Make sure your thesis statement is relevant to the topic of your essay and reflects the main point you want to make.

- Revise as needed: Don’t be afraid to revise your thesis statement as you work on your essay. It may change as you develop your ideas.

Remember, a strong thesis statement sets the tone for your entire essay and provides a roadmap for your readers to follow. Put time and effort into crafting a clear and compelling thesis statement to ensure your essay is effective and persuasive.

Developing a Clear Essay Structure

One of the key elements of writing an effective essay is developing a clear and logical structure. A well-structured essay helps the reader follow your argument and enhances the overall readability of your work. Here are some tips to help you develop a clear essay structure:

1. Start with a strong introduction: Begin your essay with an engaging introduction that introduces the topic and clearly states your thesis or main argument.

2. Organize your ideas: Before you start writing, outline the main points you want to cover in your essay. This will help you organize your thoughts and ensure a logical flow of ideas.

3. Use topic sentences: Begin each paragraph with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of the paragraph. This helps the reader understand the purpose of each paragraph.

4. Provide evidence and analysis: Support your arguments with evidence and analysis to back up your main points. Make sure your evidence is relevant and directly supports your thesis.

5. Transition between paragraphs: Use transitional words and phrases to create flow between paragraphs and help the reader move smoothly from one idea to the next.

6. Conclude effectively: End your essay with a strong conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your thesis. Avoid introducing new ideas in the conclusion.

By following these tips, you can develop a clear essay structure that will help you effectively communicate your ideas and engage your reader from start to finish.

Using Relevant Examples and Evidence

When writing an essay, it’s crucial to support your arguments and assertions with relevant examples and evidence. This not only adds credibility to your writing but also helps your readers better understand your points. Here are some tips on how to effectively use examples and evidence in your essays:

- Choose examples that are specific and relevant to the topic you’re discussing. Avoid using generic examples that may not directly support your argument.

- Provide concrete evidence to back up your claims. This could include statistics, research findings, or quotes from reliable sources.

- Interpret the examples and evidence you provide, explaining how they support your thesis or main argument. Don’t assume that the connection is obvious to your readers.

- Use a variety of examples to make your points more persuasive. Mixing personal anecdotes with scholarly evidence can make your essay more engaging and convincing.

- Cite your sources properly to give credit to the original authors and avoid plagiarism. Follow the citation style required by your instructor or the publication you’re submitting to.

By integrating relevant examples and evidence into your essays, you can craft a more convincing and well-rounded piece of writing that resonates with your audience.

Editing and Proofreading Your Essay Carefully

Once you have finished writing your essay, the next crucial step is to edit and proofread it carefully. Editing and proofreading are essential parts of the writing process that help ensure your essay is polished and error-free. Here are some tips to help you effectively edit and proofread your essay:

1. Take a Break: Before you start editing, take a short break from your essay. This will help you approach the editing process with a fresh perspective.

2. Read Aloud: Reading your essay aloud can help you catch any awkward phrasing or grammatical errors that you may have missed while writing. It also helps you check the flow of your essay.

3. Check for Consistency: Make sure that your essay has a consistent style, tone, and voice throughout. Check for inconsistencies in formatting, punctuation, and language usage.

4. Remove Unnecessary Words: Look for any unnecessary words or phrases in your essay and remove them to make your writing more concise and clear.

5. Proofread for Errors: Carefully proofread your essay for spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors. Pay attention to commonly misused words and homophones.

6. Get Feedback: It’s always a good idea to get feedback from someone else. Ask a friend, classmate, or teacher to review your essay and provide constructive feedback.

By following these tips and taking the time to edit and proofread your essay carefully, you can improve the overall quality of your writing and make sure your ideas are effectively communicated to your readers.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

How To Write an Essay

Make writing an essay as easy as making a hamburger

pointnshoot / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

- Writing Skills

- Pronunciation & Conversation

- Reading Comprehension

- Business English

- Resources for Teachers

Structuring the Essay (aka Building a Burger)

Choosing a topic, drafting the outline, creating the introduction, writing the body of the essay, concluding the essay.

- TESOL Diploma, Trinity College London

- M.A., Music Performance, Cologne University of Music

- B.A., Vocal Performance, Eastman School of Music

Writing an essay is like making a hamburger. Think of the introduction and conclusion as the bun, with the "meat" of your argument in between. The introduction is where you'll state your thesis, while the conclusion sums up your case. Both should be no more than a few sentences. The body of your essay, where you'll present facts to support your position, must be much more substantial, usually three paragraphs . Like making a hamburger, writing a good essay takes preparation. Let's get started!

Think about a hamburger for a moment. What are its three main components? There's a bun on top and a bun on the bottom. In the middle, you'll find the hamburger itself. So what does that have to do with an essay? Think of it this way:

- The top bun contains your introduction and topic statement. This paragraph begins with a hook, or factual statement intended to grab the reader's attention. It is followed by a thesis statement, an assertion that you intend to prove in the body of the essay that follows.

- The meat in the middle, called the body of the essay, is where you'll offer evidence in support of your topic or thesis. It should be three to five paragraphs in length, with each offering a main idea that is backed up by two or three statements of support.

- The bottom bun is the conclusion, which sums up the arguments you've made in the body of the essay.

Like the two pieces of a hamburger bun, the introduction and conclusion should be similar in tone, brief enough to convey your topic but substantial enough to frame the issue that you'll articulate in the meat, or body of the essay.

Before you can begin writing, you'll need to choose a topic for your essay, ideally one that you're already interested in. Nothing is harder than trying to write about something you don't care about. Your topic should be broad or common enough that most people will know at least something about what you're discussing. Technology, for example, is a good topic because it's something we can all relate to in one way or another.

Once you've chosen a topic, you must narrow it down into a single thesis or central idea. The thesis is the position you're taking in relation to your topic or a related issue. It should be specific enough that you can bolster it with just a few relevant facts and supporting statements. Think about an issue that most people can relate to, such as: "Technology is changing our lives."

Once you've selected your topic and thesis, it's time to create a roadmap for your essay that will guide you from the introduction to conclusion. This map, called an outline, serves as a diagram for writing each paragraph of the essay, listing the three or four most important ideas that you want to convey. These ideas don't need to be written as complete sentences in the outline; that's what the actual essay is for.

Here's one way of diagramming an essay on how technology is changing our lives:

Introductory Paragraph

- Hook: Statistics on home workers

- Thesis: Technology has changed work

- Links to main ideas to be developed in the essay: Technology has changed where, how and when we work

Body Paragraph I

- Main idea: Technology has changed where we can work

- Support: Work on the road + example

- Support: Work from home + example statistic

Body Paragraph II

- Main idea: Technology has changed how we work

- Support: Technology allows us to do more on our own + example of multitasking

- Support: Technology allows us to test our ideas in simulation + example of digital weather forecasting

Body Paragraph III

- Main idea: Technology has changed when we work

- Support: Flexible work schedules + example of telecommuters working 24/7

- Support: Technology allows us to work any time + example of people teaching online from home

Concluding Paragraph

- Review of main ideas of each paragraph

- Restatement of thesis: Technology has changed how we work

- Concluding thought: Technology will continue to change us

Note that the author uses only three or four main ideas per paragraph, each with a main idea, supporting statements, and a summary.

Once you've written and refined your outline, it's time to write the essay. Begin with the introductory paragraph . This is your opportunity to hook the reader's interest in the very first sentence, which can be an interesting fact, a quotation, or a rhetorical question , for instance.

After this first sentence, add your thesis statement . The thesis clearly states what you hope to express in the essay. Follow that with a sentence to introduce your body paragraphs . This not only gives the essay structure, but it also signals to the reader what is to come. For example:

Forbes magazine reports that "One in five Americans work from home". Does that number surprise you? Information technology has revolutionized the way we work. Not only can we work almost anywhere, we can also work at any hour of the day. Also, the way we work has changed greatly through the introduction of information technology into the workplace.

Notice how the author uses a fact and addresses the reader directly to grab their attention.

Once you've written the introduction, it's time to develop the meat of your thesis in three or four paragraphs. Each should contain a single main idea, following the outline you prepared earlier. Use two or three sentences to support the main idea, citing specific examples. Conclude each paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the argument you've made in the paragraph.

Let's consider how the location of where we work has changed. In the past, workers were required to commute to work. These days, many can choose to work from the home. From Portland, Ore., to Portland, Maine, you will find employees working for companies located hundreds or even thousands of miles away. Too, the use of robotics to manufacture products has led to employees spending more time behind a computer screen than on the production line. Whether it's in the countryside or in the city, you'll find people working everywhere they can get online. No wonder we see so many people working at cafes!

In this case, the author continues to directly address the reader while offering examples to support their assertion.

The summary paragraph summarizes your essay and is often a reverse of the introductory paragraph. Begin the summary paragraph by quickly restating the principal ideas of your body paragraphs. The penultimate (next to last) sentence should restate your basic thesis of the essay. Your final statement can be a future prediction based on what you have shown in the essay.

In this example, the author concludes by making a prediction based on the arguments made in the essay.

Information technology has changed the time, place and manner in which we work. In short, information technology has made the computer into our office. As we continue to use new technologies, we will continue to see change. However, our need to work in order to lead happy and productive lives will never change. The where, when and how we work will never change the reason why we work.

- Writing Cause and Effect Essays for English Learners

- Persuasive Writing: For and Against

- Paragraph Writing

- Personal Descriptions

- Sentence Connectors and Sentences

- Writing About Cities

- Writing Sentences for Beginners

- Complex Sentence Worksheet

- How to Use Sentence Connectors to Show Contrast

- Learn to Order Events for Narrative Writing Assignments

- Parallel Structure

- Writing Descriptive Paragraphs

- How to Use Sentence Connectors to Express Complex Ideas

- Beginning Writing Short Writing Assignments

- Sentence Patterns

- Compound-Complex Sentence Worksheet

What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

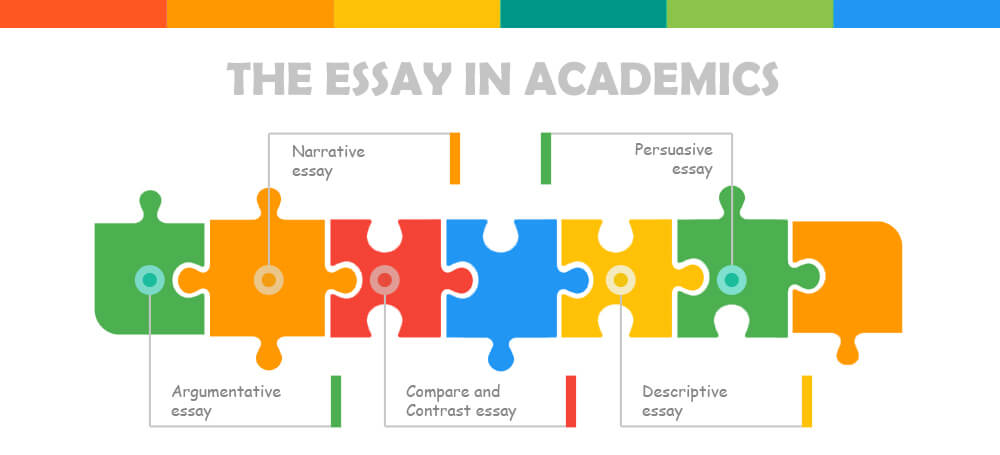

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Verify originality of an essay

Get ideas for your paper

Cite sources with ease

150 Exemplification Essay Topics: Inspiration & Writing Tips

Updated 23 Sep 2024

What is an Exemplification Essay?

An exemplification essay is a type of argumentative writing that uses specific examples to clarify a general idea or to support a thesis. It is commonly used in academic settings to present a balanced and thorough discussion on a given topic. Writers often employ this style when they need to explain complex concepts or controversial issues, using real-world examples to illustrate their points.

Exemplification essays are particularly useful in educational contexts, research papers, and persuasive writing, where a deeper understanding and clear communication are essential. This essay type requires a structured approach, including an introduction with a clear thesis, body paragraphs presenting detailed examples, and a conclusion reinforcing the argument. The key is to provide enough examples to substantiate the claim without overwhelming the reader.

The Importance of Choosing a Good Topic for an Exemplification Essay

Selecting the right topic for an exemplification essay is crucial as it sets the foundation for your entire piece. A well-chosen topic makes the writing process smoother and ensures that your essay is engaging and informative for your audience. It allows you to explore a subject thoroughly, using concrete examples to support your argument and make complex ideas more accessible.

When choosing a topic, consider your interests and its relevance to your audience. Opt for subjects that offer a balance between being broad enough to find numerous examples and specific enough to maintain a clear focus. This will help you craft a compelling essay that is both persuasive and insightful.

Tips for Choosing a Good Topic:

- Choose a Relevant Issue: Select a topic that resonates with current social, technological, or cultural trends.

- Ensure Availability of Examples: Make sure you can find concrete examples to support your arguments.

- Balance Complexity and Clarity: Avoid overly complicated topics that are difficult to explain or too simple that they lack depth.

By carefully selecting your topic, you ensure a more effective and impactful essay that resonates with readers.

150+ Exemplification essay topics across subjects

Technology and innovation.

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment

- Pros and Cons of Blockchain Technology in Finance

- The Role of Technology in Modern Education

- Cybersecurity Challenges in the Digital Age

- The Influence of Social Media on Society

- Big Data and Privacy Concerns

- The Future of Autonomous Vehicles

- How Virtual Reality is Changing Entertainment

- Renewable Energy Innovations and Sustainable Development

- The Role of Drones in Environmental Conservation

Environmental Issues

- Climate Change: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

- Plastic Pollution in Oceans and Solutions

- Deforestation and Its Impact on Biodiversity

- The Global Water Crisis and Sustainable Water Management

- The Role of Individuals in Environmental Conservation

- Urban Sprawl and Its Environmental Impact

- The Impact of Fast Fashion on the Environment

- Sustainable Agriculture Practices

- Air Pollution and Its Effects on Public Health

- The Future of Electric Vehicles and Green Transportation

Social Issues

- The Global Impact of Poverty and Inequality

- Gender Equality: Progress and Challenges

- The Effects of Globalization on Local Cultures

- Racial Discrimination and Social Justice Movements

- Mental Health Awareness and Stigma Reduction

- The Refugee Crisis: Causes and Solutions

- The Role of Social Media in Activism

- LGBTQ+ Rights and Legal Recognition Worldwide

- Human Trafficking: A Modern Form of Slavery

- The Opioid Crisis: Public Health and Policy Responses

Health and Wellness

- The Importance of Nutrition in Preventing Chronic Diseases

- The Impact of Exercise on Mental Health

- Vaccinations: Myths and Facts

- The Global Rise of Obesity and Public Health Strategies

- The Benefits of Mindfulness and Meditation

- The Relationship Between Mental Health and Social Media Use

- The Role of Genetics in Personalized Medicine

- The Health Risks of Air and Water Pollution

- The Importance of Sleep for Overall Health

- Stress Management Techniques for a Balanced Life

Education and Learning

- The Benefits and Challenges of Homeschooling

- The Importance of Early Childhood Education

- Online Learning: Pros and Cons

- The Future of Higher Education Post-Pandemic

- The Importance of STEM Education

- The Role of Art and Music in Cognitive Development

- The Impact of Social Media on Learning and Attention

- The Importance of Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

- The Role of Physical Education in Schools

Business and Economics

- The Effects of Globalization on Small Businesses

- Corporate Social Responsibility and Its Impact on Brand Image

- The Influence of E-commerce on Traditional Retail

- The Importance of Financial Literacy for Young Adults

- The Role of Startups in Economic Development

- Ethical Issues in Corporate Governance

- The Impact of Remote Work on Business Productivity

- The Future of Cryptocurrency in Global Markets

- The Role of Women in Business Leadership

- The Effects of Minimum Wage Increases on the Economy

Politics and Law

- The Impact of Lobbying on Political Decisions

- The Importance of Voting in a Democracy

- The Role of International Organizations in Global Peacekeeping

- The Effects of Media Bias on Public Opinion

- The Ethics of Capital Punishment

- The Influence of Social Movements on Legal Reforms

- The Impact of Immigration Policies on Society

- Freedom of Speech vs. Hate Speech: A Legal Perspective

- The Role of the Judiciary in Protecting Human Rights

- The Effectiveness of Gun Control Laws

Science and Research

- The Importance of Space Exploration for Humanity

- The Ethical Implications of Genetic Engineering

- The Role of Vaccines in Public Health

- The Impact of Climate Change on Marine Life

- The Benefits and Risks of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

- The Role of Citizen Science in Research

- The Future of Renewable Energy Technologies

- The Ethics of Animal Testing in Scientific Research

- The Role of Research in Developing Sustainable Agriculture

- The Importance of Funding for Scientific Innovation

Media and Entertainment

- The Influence of Pop Culture on Youth Behavior

- The Role of Journalism in Modern Society

- The Impact of Reality TV on Public Perception

- The Evolution of Film Genres Over the Decades

- The Role of Music in Cultural Identity

- The Influence of Video Games on Cognitive Skills

- The Impact of Social Media on Celebrity Culture

- The Role of Documentaries in Social Awareness

- The Evolution of News Consumption in the Digital Age

- The Influence of Advertising on Consumer Behavior

Lifestyle and Personal Development

- The Importance of Work-Life Balance

- The Role of Hobbies in Personal Growth