- Teaching Resources

- Upcoming Events

- On-demand Events

6 Essays on Women's History

- facebook sharing

- email sharing

Check out the following 6 blog posts in which the contributions of a number of key figures from women’s history are discussed. Together, these posts shed light on some of the unique ways that women have helped to shape the political landscapes of multiple countries and the experiences of workers in industries including the teaching profession itself.

Fannie Lou Hamer: Unsung Woman of the Civil Rights Movement Facing History Cleveland recently offered a riveting professional development webinar to Ohio-based educators called “Standing on Their Shoulders: Unsung Women of the Civil Rights Movement.” There, Program Director Pamela Donaldson and Senior Program Associate Lisa Lefstein-Berusch provided educators with strategies and frameworks they can use to broaden students’ knowledge of the contributions Black women made to the movement, as well as deepen students’ understanding of specific strategies that have driven social change.

Dolores Huerta's Life of Indefatigable Resistance A powerful story that is often left out of news stories and history books is that of Dolores Huerta—a Chicana activist whose contributions rival those of the most renowned civil rights leaders in U.S. history, but whose legacy is significantly less known. Awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012 and nine honorary doctorates, Huerta is a living legend in the labor movement and has been a tireless advocate for social justice for over 50 years.

Remembering Daisy Bates: Orator at the March on Washington The March on Washington was the historic 1963 protest in which as many as 500,000 people marched to demand jobs and freedom for Americans of all racial backgrounds. Though many of us remember this as the day that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, it is easy to forget that he was not the only civil rights leader to address the crowd. One of the leaders who joined him was movement veteran Daisy Bates—the only woman permitted to speak, though not in her own words.

How One Lesbian Couple Defied the Nazis: An Interview with Dr. Jeffrey Jackson We spoke with Dr. Jeffrey Jackson—Professor of History at Rhodes College and author of Paper Bullets: Two Artists Who Risked Their Lives to Defy the Nazis . In this interview. Dr. Jackson discusses the untold story of Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe, a French lesbian couple who intervened in the Nazi occupation of the Channel Islands through an expansive artistic campaign during World War II. Better known to art historians by their adopted names of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, Schwob and Malherbe’s story of resistance is told for the first time in Dr. Jackson’s new book. Here he shares a first look at their incredible story with Facing History.

Women's Suffrage at 100: The Key Role of Black Sororities Tuesday, August 18, 2020 marked the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This amendment established women's suffrage for the first time, granting white women across the country the right to vote to the exclusion of non-white women. Yet the women's suffrage movement contained many more key players than this outcome suggests. Among them were African American luminaries like Mary Church Terrell and the scores of Black women who joined with her to demand equal rights.

Teaching in the Light of Women's History Though we often think of Women’s History Month as a time to prioritize women’s voices and contributions in the classroom, this month is also a time to examine the profound ways in which women teachers, and broader perceptions of women, have shaped the teaching profession itself. From contemporary perceptions of the profession and the compensation of its workers, to the grounds for collective action that American teachers now enjoy, none can be understood outside the patriarchal context in which modern schooling emerged and women demanded justice. Examining this history offers not only a richer understanding of the challenges faced by today’s teachers, but reveals places where we must continue to disrupt patriarchal rhetoric if we are to cultivate school communities that do right by teachers and students.

You might also be interested in…

Race and equity in the jewish educational context, race, equity, and the state of education: a conversation with dr. pedro noguera, george takei: standing up to racism, then and now, memphis 1968: lessons for today, critical reflections about equity in education with dr. john b. king and dr. janice k. jackson, student reflections on black history month, teaching for equity and justice: a conversation with linda darling-hammond, all community read: a spotlight on disability rights, introducing ideas this week, conversations #behindthelens for lgbtq+ history month, march assemblies, reckoning with our past: the legacy of migration and belonging in us history, donate now and together we'll build a better world, inspiration, insights, & ways to get involved.

- Library of Congress

- Research Guides

- Multiple Research Centers

American Women: Topical Essays

Introduction.

- American Women: An Overview

- Marching for the Vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913

- Sentiments of an American Woman

- The House That Marian Built: The MacDowell Colony of Peterborough, New Hampshire

- Women On The Move: Overland Journeys to California

- “With Peace and Freedom Blest!”: Woman as Symbol in America, 1590-1800

- The Long Road to Equality: What Women Won from the ERA Ratification Effort

Women’s history

World history.

- The historian’s sources

- From explanation to interpretation

- The presentation of history

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Alamo Colleges District - Historiography: The Presentation of History

- University of Guelph - Mc Laughlin Library - What is historiography?

- Alpha History - What is Historiography?

- Academia - Historiography

- Table Of Contents

In the 19th century, women’s history would have been inconceivable, because “history” was so closely identified with war , diplomacy, and high politics—from all of which women were virtually excluded. Although there had been notable queens and regents—such as Elizabeth I of England , Catherine de Medici of France, Catherine the Great of Russia, and Christina of Sweden —their gender was considered chiefly when it came to forming marriage alliances or bearing royal heirs. Inevitably, the ambition to write history “from the bottom up” and to bring into focus those marginalized by previous historiography inspired the creation of women’s history.

One of the consequences of the professionalization of history in the 19th century was the exclusion of women from academic history writing. A career like that of Catherine Macaulay (1731–91), one of the more prominent historians of 18th-century England, was impossible one hundred years later, when historical writing had been essentially monopolized by all-male universities and research institutes. This exclusion began to break down in the late 19th century as women’s colleges were founded in England (e.g., at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge) and the United States . Some of these institutions, such as Bryn Mawr College in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, had strong research agendas.

Although the earliest academic women’s historians were drawn to writing about women, it cannot be said that they founded, or even that they were interested in founding, a specialty like “women’s history.” Alice Clark wrote Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century (1920), and Eileen Power wrote Medieval English Nunneries c. 1275 to 1535 (1922), a definitive monograph, and Medieval Women (published posthumously in 1975). Many women (including some in the early history of the Annales ) worked as unpaid research assistants and cowriters for their husbands, and it is doubtless that they were deprived of credit for being historians in their own right. An exception was Mary Ritter Beard (1876–1958), who coauthored a number of books with her more famous husband, Charles Beard , and also wrote Women as a Force in History , arguably the first general work in American women’s history.

Since it was still possible in the 1950s to doubt that there was enough significant evidence on which to develop women’s history, it is not surprising that some of the earliest work was what is called “contribution history.” It focused, in other words, on the illustrious actions of women in occupations traditionally dominated by men. The other preoccupation was the status of women at various times in the past. This was customarily evaluated in terms of comparative incomes, laws about ownership of property, and the degree of social freedom allowed within marriage or to unmarried women. In The Creation of Patriarchy (1986), Gerda Lerner, whose work chiefly concerned women in the United States, examined Mesopotamian society in an attempt to discover the ancient roots of the subjection of women. Explorations of the status of women also contributed to a rethinking of fundamental historical concepts, as in Joan Kelly’s essay “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” (1977).

Another area of study, which was curiously slow to emerge, was the history of the family. Since in all times most women have been wives and mothers for most of their adult lives, this most nearly universal of female experiences would seem to dictate that women’s historians would be especially interested in the history of the family. Yet for a long time few of them were. The history of the family was inspired primarily not by women’s history but by advances made in historical demography, whose heavy quantification women’s history generally avoided.

This partly explains why the majority of works in women’s history have dealt with unmarried women—as workers for wages, nuns, lesbians, and those involved in passionate friendships. Evidence concerning the lives of these figures is in some ways easier to come by than evidence of maternal and family life, but it is also clear that feminist historians were averse to studying women as victims of matrimony—as they all too often were. There are, however, intersections between history of the family and women’s history. A few historians have written works on family limitation ( birth control ) in the United States, for example; one of these scholars, Linda Gordon, raised the important question of why suffragists and other feminists did not as a rule support campaigns for family limitation.

Another way in which women’s history can lead to a reassessment of history in general is by analyzing the concept of gender. Joan Scott has taken the lead in this effort. Gender, according to Scott and many others, is a socially constructed category for both men and women, whereas sex is a biological category denoting the presence or absence of certain chromosomes. Even physical differences between the sexes can be exaggerated (all fetuses start out female), but differences in gender are bound to be of greatest interest to historians. Of particular interest to women’s historians are what might be called “gender systems,” which can be engines of oppression for both men and women.

World history is the most recent historical specialty, yet one with roots in remote antiquity. The great world religions that originated in the Middle East— Judaism , Christianity , and Islam —insisted on the unity of humanity, a theme encapsulated in the story of Adam and Eve . Buddhism also presumed an ecumenical view of humankind. The universal histories that characterized medieval chronicles proposed a single story line for the human race , governed by divine providence; and these persisted, in far more sophisticated form, in the speculative philosophies of history of Vico and Hegel. Marxism too, although it saw no divine hand in history, nevertheless held out a teleological vision in which all humanity would eventually overcome the miseries arising from class conflict and leave the kingdom of necessity for the kingdom of plenty.

These philosophies have left their mark on world history, yet few historians (except for Marxists) now accept any of these master narratives. This fact, however, leads to a conceptual dilemma: if there is no single story in which all of humanity finds a part, how can there be any coherence in world history? What prevents it from simply being a congeries of national—or at the most regional—histories?

Modernization theorists have embraced one horn of this dilemma. There is, after all, a single story, they argue; it is worldwide Westernization. Acknowledging the worth of non-Western cultures and the great non-European empires of the past, they nevertheless see the lure of Western consumer goods—and the power of multinational corporations—as irresistible. This triumphalist view of Western economic and political institutions drew great new strength from the downfall of the managed economies of eastern Europe and the emergence in China of blatant state capitalism . It is easier to claim worldwide success for capitalism than for democracy , since capitalism has been perfectly compatible with the existence of autocratic governments in Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong; but history does suggest that eventually capitalist institutions will give rise to some species of democratic institutions, even though multinational corporations are among the most secretive and hierarchical institutions in Western society.

Modernization theory has been propounded much more enthusiastically by sociologists and political scientists than by historians. Its purest expression was The Dynamics of Modernization (1966), by Cyril Edwin Black, which made its case by studying social indexes of modernization, such as literacy or family limitation over time, in developing countries. Extending this argument in a somewhat Hegelian fashion, the American historian Francis Fukuyama provocatively suggested, in The End of History and the Last Man (1992), that history itself, as traditionally conceived, had ceased. This, of course, meant not that there would be no more events but that the major issues of state formation and economic organization had now been decisively settled in favour of capitalism and democracy . Fukuyama was by no means a simple-minded cheerleader for this denouement; life in a world composed of nothing but liberal nation-states would be, among other things, boring.

A much grimmer aspect of modernization was highlighted by Theodore H. Von Laue (1987) in The World Revolution of Westernization . Von Laue focused on the stresses imposed on the rest of the world by Westernization, which he saw as the root cause of communism , Nazism , dictatorships in developing countries, and terrorism . He declined to forecast whether these strains would continue indefinitely.

The stock objection to modernization theory is that it is Eurocentric. So it is, but this is hardly a refutation of it. That European states (including Russia) and the United States have been the dominant world powers since the 19th century is just as much a fact as that Europe was a somewhat insignificant peninsula of Asia in the 12th century. Some modernization theorists have caused offense by making it clear that they think European dominance is good for everybody, but it is noteworthy how many share the disillusioned view of the German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920), who compared the rational bureaucracies that increasingly dominated European society to an “iron cage.” More-valid criticisms point to the simplistic character of modernization theory and to the persistence and even rejuvenation of ostensibly “premodern” features of society—notably religious fundamentalism .

A considerably more complex scheme of analysis, world-systems theory, was developed by Immanuel Wallerstein in The Modern World System (1974). Whereas modernization theory holds that economic development will eventually percolate throughout the world, Wallerstein believed that the most economically active areas largely enriched themselves at the expense of their peripheries . This was an adaptation of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin ’s idea that the struggle between classes in capitalist Europe had been to some degree displaced into the international economy, so that Russia and China filled the role of proletarian countries. Wallerstein’s work was centred on the period when European capitalism first extended itself to Africa and the Americas, but he emphasized that world-systems theory could be applied to earlier systems that Europeans did not dominate. In fact, the economist André Gunder Frank argued for an ancient world-system and therefore an early tension between core and periphery . He also pioneered the application of world-systems theory to the 20th century, holding that “underdevelopment” was not merely a form of lagging behind but resulted from the exploitative economic power of industrialized countries. This “development of underdevelopment,” or “dependency theory,” supplied a plot for world history, but it was one without a happy ending for the majority of humanity. Like modernization theory, world-systems theory has been criticized as Eurocentric. More seriously, the evidence for it has been questioned by many economists, and while it has been fertile in suggesting questions, its answers have been controversial.

A true world history requires that there be connections between different areas of the world, and trade relations constitute one such connection. Historians and sociologists have revealed the early importance of African trade (Columbus visited the west coast of Africa before his voyages to the Americas, and he already saw the possibilities of the slave trade), and they have also illuminated the 13th-century trading system centring on the Indian Ocean , to which Europe was peripheral .

Humans encounter people from far away more often in commercial relationships than in any other, but they exchange more than goods. William H. McNeill , the most eminent world historian, saw these exchanges as the central motif of world history. Technological information is usually coveted by the less adept, and it can often be stolen when it is not offered. Religious ideas can also be objects of exchange. In later work, McNeill investigated the communication of infectious diseases as an important part of the story of the human species. In this he contributed to an increasingly lively field of historical studies that might loosely be called ecological history.

Focusing on the biological substrate of history can sometimes capture a vital element of common humanity. This was an early topic for the Annales historians, who were often trained in geography . Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie grounded his great history of the peasants of Languedoc in the soil and climate of that part of France , showing how the human population of the ancien régime was limited by the carrying capacity of the land. He went on to write a history of the climate since the year 1000. Even more influential were the magisterial works of Fernand Braudel (1902–85), perhaps the greatest historian of the 20th century. Braudel’s La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l’époque de Philippe II (1949; The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II ) had a political component, but it seemed almost an afterthought. Although it was not a world history, its comprehensive treatment of an entire region comprising Muslim and Christian realms and the fringes of three continents succeeded in showing how they shared a similar environment . The environment assumed an even greater role in Braudel’s Civilisation matérielle et capitalisme, XVe–XVIIIe siècle (vol. 1, 1967; vol. 2–3, 1979; Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century ). Although some of its claims seemed designed to shock conventional historical sensibilities—the introduction of forks into Europe, he wrote, was more important than the Reformation—no historical work has done more to explore the entire material base on which civilizations arise

One of the most important links between ecological history and world history is the so-called Columbian exchange , through which pathogens from the Americas entered Europe and those from Europe devastated the indigenous populations of the Americas. The Native Americans got much the worse of this exchange; the population of Mexico suffered catastrophic losses, and that of some Caribbean islands was totally destroyed. The effect on Europeans was much less severe. It is now thought that syphilis entered Europe from Asia, not the Americas.

Overt moralizing in historiography tends to attract professional criticism , and historians in Europe and the United States, where nation-states have long been established, no longer feel the moral obligation that their 19th-century predecessors did to exalt nationalism . They can therefore respond to global concerns, such as the clear-cutting of rainforests and global warming . It has become obvious that the world is a single ecosystem, and this may require and eventually evoke a corresponding world history.

There is, however, a powerful countertendency: subaltern history . Subaltern is a word used by the British army to denote a subordinate officer, and “subaltern studies” was coined by Indian scholars to describe a variety of approaches to the situation of South Asia , in particular in the colonial and postcolonial era. A common feature of these approaches is the claim that, though colonialism ended with the granting of independence to the former colonies of Britain , France, the United States, and other empires, imperialism did not. Instead, the imperial powers continued to exert so much cultural and economic hegemony that the independence of the former colonies was more notional than real. Insisting on free trade (unlimited access to the domestic markets of the former colonies) and anticommunism (usually enforced by autocratic governments), the old empires, as the subaltern theorists saw it, had reverted to the sort of indirect rule that the British had exerted over Argentina and other countries in the 19th century.

The other belief that united subaltern theorists is that this hegemony should be challenged. Orientalism (1978), by the literary critic Edward Said , announced many of the themes of subaltern studies. The Orient that Said discussed was basically the Middle East , and the Orientalism was the body of fact, opinion, and prejudice accumulated by western European scholars in their encounter with it. Said stressed the enormous appetite for this lore, which influenced painting, literature, and anthropology no less than history. It was, of course, heavily coloured by racism , but perhaps the most insidious aspect of it, in Said’s view, was that Western categories not only informed the production of knowledge but also were accepted by the colonized countries (or those nominally independent but culturally subordinate). The importation of Rankean historiography into Japan and Russia is an example. The result has been described rather luridly as epistemological rape, in that the whole cultural stock of colonized peoples came to be discredited.

Although originally and most thoroughly applied to the Middle East and South Asia, subaltern history is capable of extension to any subordinated population, and it has been influential in histories of women and of African Americans . Its main challenge to world history is that most subaltern theorists deny the possibility of any single master narrative that could form a plot for world history. This entails at least a partial break with Marxism, which is exactly such a narrative. Instead, most see a postmodern developing world with a congeries of national or tribal histories, without closures or conventional narratives, whose unity, if it has one at all, was imposed by the imperialist power.

The project of bringing the experience of subordinated people into history has been common in postwar historiography, often in the form of emphasizing their contributions to activities usually associated with elites. Such an effort does not challenge—indeed relies on—ordinary categories of historical understanding and the valuation placed on these activities by society. This has seemed to some subaltern theorists to implicate the historian in the very oppressive system that ought to be combated. The most extreme partisans of this combative stance claim that, in order to resist the hegemonic powers, the way that history is done has to be changed. Some feminists, for example, complain that the dominant system of logic was invented by men and violates the categories of thought most congenial to women. This is one of the reasons for the currency and success of postmodernist and postcolonialist thought. It licenses accounts of the past that call themselves histories but that may deviate wildly from conventional historical practice.

Such histories have been particularly associated with a “nativist” school of subaltern studies that rejects as “Western” the knowledge accumulated under the auspices of imperialism. An instructive example was the effort by Afrocentric historians to emphasize the possible Egyptian and Phoenician origins of classical Greek thought. Martin Bernal , for example, tried to show in Black Athena (1987) that the racist and anti-Semitic Orientalist discourse of the late 19th century (particularly but not exclusively in Germany ) obscured the borrowings of the classical Greeks from their Semitic and African neighbours. That there were borrowings, and that Orientalist discourse was racist and anti-Semitic, is beyond doubt, but these are findings made through ordinary historical investigation—whose conventions Bernal did not violate, despite the speculative character of some of his conclusions. How much distortion there was would also seem to be an ordinary, though difficult, historical question (made more difficult by the claim that the Egyptians had an esoteric and unwritten philosophical tradition that has left no documentary traces but that may have been imparted to Greek thinkers). But no historian could accept the claim that Aristotle gained knowledge from the library at Alexandria , since it was not built until after his death. If the idea that effects cannot precede causes is merely a culture-bound presupposition of Western-trained historians, then there is no logical basis for rejecting even a claim such as this. The nativist subaltern historians deserve credit at least for raising this issue (though, of course, not with such extreme examples). However, the price to be paid is high: if there are no logical categories that are not culture-bound, then people from different cultures cannot have a meaningful argument—or agreement—because these require at least some mutual acceptance of what will count as evidence and how reasoning is to be done . Most subaltern historians have therefore steered between the Scylla of contribution history and the Charybdis of nativism, and their emphasis on studying the mass of the people rather than colonial elites has had a powerful effect not only on the history of Asia and Africa but also on that of Europe and even the United States.

U.S. History As Women's History

New feminist essays, edited by linda k. kerber , alice kessler-harris , kathryn kish sklar.

488 pp., 6 x 9, 10 illus

- Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8078-4495-3 Published: March 1995

- E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-6686-3 Published: November 2000

- E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-6520-5 Published: November 2000

Gender and American Culture

Buy this book.

- Paperback $42.50

- E-Book $29.99 Barnes and Noble Ebooks Apple iBookstore Google eBookstore Amazon Kindle

About the Authors

Linda K. Kerber, May Brodbeck Professor of History at the University of Iowa, is author of Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America . For more information about Linda K. Kerber, visit the Author Page .

Alice Kessler-Harris, professor of history at Rutgers University, is author of Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States . For more information about Alice Kessler-Harris, visit the Author Page .

Kathryn Kish Sklar, Distinguished Professor of History at the State University of New York, Binghamton, is author of Florence Kelley and the Nation's Work: The Rise of Women's Political Culture, 1830-1900 . For more information about Kathryn Kish Sklar, visit the Author Page .

Quick Links

Permissions Information

Subsidiary Rights Information

Media Inquiries

Related Subjects

Women's Studies

Related Books

In dialogue: Writing women’s history

By Marion Turner, Margaret Chowning, Virginia Trimble, and David A. Weintraub March 27, 2023

Over the last century, radical shifts in historical scholarship have filled glaring gaps in the way we understand gender from the past and in the present. By developing new methods of writing history, feminist scholars have produced more pluralistic and inclusive histories globally. In celebration of this collective effort, we asked four of our authors the following question: What do we find when we read ‘women’ into histories that often exclude them? Their responses, ranging from medieval British literature to postcolonial Mexico to modern astronomy, illuminate the necessity of excavating women and womanhood from the past and the gifts we all enjoy upon doing so. This Women’s History Month, we present this dialogue to honor the innumerable women who make up our history as well as the many who write it.

Marion Turner | The Wife of Bath: A Biography

In Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey , the heroine, Catherine Morland, confesses that she cannot make herself enjoy reading history: “The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all—it is very tiresome.” Across time, the kinds of records that we have, and the kinds of stories that historians have most wanted to tell, have undoubtedly focused on men: on kings, soldiers, parliaments and other institutions which rigorously excluded women for most of history. Women’s histories are harder to excavate, but can be glimpsed and sometimes uncovered, if you know where to look and if you want to tell those unheard stories.

My 2019 biography of the fourteenth-century poet Chaucer— Chaucer: A European Life —was the story of a privileged man’s life, a story that had been told in different ways by many male biographers before me. I tried to do many things in this book, and one of those things was to look more at the women in Chaucer’s life. Very little work had been done on his daughter Elizabeth, for example, and I was able to find out fascinating information about the nunnery in which she lived. The nuns had been chastised for dancing and partying too much and having too many overnight guests. Similarly, while medievalists had long known that the earliest Chaucer life-record involved Chaucer being given some clothes, I put this record under a closer focus. The clothes had been given to him by his female employer, the countess of Ulster, and she was choosing to dress her young page in a scandalously tight and revealing outfit—in a style that was roundly condemned by contemporary chroniclers.

“Women’s histories are harder to excavate, but can be glimpsed and sometimes uncovered, if you know where to look and if you want to tell those unheard stories.”

Nuns, parties, and fashion: these are as important in understanding Chaucer’s life and world as his work as a Member of Parliament, a Customs’ Officer, and a diplomat. And these more traditionally ‘male’ strands of history are not exclusively male either. His second trip to Italy, for instance, was made with the aim of organising a marriage alliance; he got his job as a Customs’ Officer at least partly because of his sister-in-law’s liaison with John of Gaunt.

My most recent project focuses primarily on recovering medieval women’s stories. It concentrates on an extraordinary female character—the Wife of Bath—and explores why and how she emerged in the late fourteenth century and how she has been treated across time, most recently with Zadie Smith’s 2021 adaptation. Taking this fictional woman as a focus, I created a methodology that allowed me to write a composite and experimental ‘biography,’ by delving into the lives of many fascinating medieval women.

I found, for example, a group of women who formed a union in the 1360s to complain to the king and mayor of London about price-fixing by a prominent male merchant. I found a widow who took over her husband’s skinning business, producing furs, ran it successfully, employed apprentices, and remembered a female scribe, as well as other women, in her will. I found a maid who abandoned her employer half-way across Europe in order to begin a social ascent, eventually gaining a far better job in Rome and dispensing patronage to her former employer. I found female blacksmiths, parchment-makers, and ship-owners. I found women who suffered abuse and women who made their voices heard in exposing misogyny and violence.

Perhaps most importantly, by tracing long histories, it became absolutely clear that things have not steadily improved across time. Women’s voices were sometimes suppressed more in later centuries than they were in the medieval era: for example, 1970s adaptations of the Wife of Bath were more misogynist than fifteenth-century versions. Recent events in the US have reminded us that the history of women’s rights is not an ongoing forward march. In my own study of the Wife of Bath, I saw hopeful signs in the last twenty years, when more female authors have made their voices heard and have produced intelligent and sensitive adaptations. But women’s voices are by no means heard equally with men’s, even today. The work of listening to women’s voices is as urgent now as it has ever been.

Margaret Chowning | Catholic Women and Mexican Politics, 1750–1940

Bucking the recent trend toward long, story-telling titles, I decided to call my recent book simply “ Catholic Women and Mexican Politics.” This was after some false starts that included the word “gender” somewhere in the title. Although there is gender analysis in my project—both comparisons between women’s and men’s experiences, and discussions of gendered political discourses—the research centers on the real Catholic women who led other Catholic women, first into new relationships with priests within the church and then into political battles and collaborations with priests in an effort to try to preserve the special role of the Catholic church in Mexico.

“In my field of Mexican history, by the time women’s history was dead we had hardly begun the work of retrieving women from the archive.”

My embrace of social history and women’s history is a bit of a contrarian (some would say antiquarian) position among feminist scholars, most of whom—at least since 1986, with the publication of Joan Scott’s famous essay that called gender (not women) a “useful” category of analysis—have seen “women’s history” as a more or less failed experiment. Too easy for non-feminist historians to ignore, too focused on stories of overcoming male oppression, too predictable and narrow in its themes. The very universality of those themes across time and space, thrilling in the early days of women’s history, eventually made them seem banal.

But in my field of Mexican history, by the time women’s history was dead we had hardly begun the work of retrieving women from the archive. Potentially important stories (not just about oppression; not predictable; capable of altering the traditional narrative) were abandoned in favor of a framework of gender (itself sometimes producing predictable results, though that is not my point here).

I lucked out in my project. The archive revealed not just a rather shocking change in women’s relationship to the church after the turmoil of Mexican independence (women suddenly came to lead lay associations with men as members, “governing” them in an upending of the natural order of things), but also a story of Catholic women first organizing and leading lay associations and then using those lay associations as vehicles to mobilize petition campaigns in defense of church power and privilege. Since the proper and appropriate role of the church in Mexican society was at the center of politics from independence in 1821 to well into the twentieth century, this meant women were weighing in on vital political issues. And they were being paid attention to. The way the liberal press handled women’s petitioning falls into the category of predictable gendered political discourse, but the way the conservative press squirmed and shuddered its way to an embrace of women’s petitioning was as interesting as the way the church managed to accept Catholic women as leaders of important parish organizations.

This story of Catholic women shifts the traditional narrative of Mexican history, not just by showing that women seized political power much earlier than generally thought, but also by refocusing our attention on the liberal and anticlerical reform era of the mid-nineteenth century, and away, to a certain extent, from the 1910 Revolution. I was lucky to find such a story, but I found it because I was interested in women and not just gender.

Virginia Trimble | The Sky Is for Everyone: Women Astronomers in Their Own Words

Perhaps it should be unnecessary to say (but perhaps isn’t) that we all want our stories to be as accurate as possible in history of science as well as in chemistry, cosmology, condensed matter physics, and all the rest. Properly including the contributions of women scientists, as well as other minorities, is part of this process.

Now, assuming we all agree about this goal, other questions arise. One not much asked is whether our science would have progressed more rapidly if the capabilities of women had been more fully incorporated in the past. An example from my “alternative history” file is the case of Cecilia Helena Payne (later Gaposchkin). Her 1925 astronomy PhD dissertation at Harvard was a “first” in several respects, but the astronomically important point was that she demonstrated (using observations gathered by women and men, plus theoretical contributions from men) that stars are made mostly of hydrogen and helium. She finished this about when her fellowship funding ran out, was later employed at Harvard College Observatory by Shapley, and then had to work mostly on what he ordered. This was stellar photometry, variable and binary stars, not more about chemical composition of stars.

“If you take away the (not always properly recognized) contributions made by women, do you significantly slow down the progress of science?”

My “what if” is this: What if she had continued along her own lines? Would she have discovered the differences in heavy element abundances between different populations of stars and thus laying the foundation for our understanding of the evolution of the Milky Way and other galaxies? This foundation is now credited to Eggen, Lynden-Bell, and Sandage in a 1962 paper, perhaps 30 years after she might have got there following her own path. There are surely other examples from other parts of science. Names to conjure with include Rosalind Franklin, Marietta Blau, and Lisa Meitner.

A different follow-on question is this: If you take away the (not always properly recognized) contributions made by women, do you significantly slow down the progress of science? Some of these contributions were made by wives, or sometimes sisters or daughters, of scientists who generally get most of the credit. Others came from women hired, cheaply, to act as human computers and other assistants to the men. Clued-in astronomers today would surely think of Henrietta Swan Leavitt, who discovered the period-luminosity relationship for Cepheid variable stars, used (and sometimes misused) in studies of galaxies and cosmology today.

A second example that comes incompletely to mind is the computers who worked with Chandrasekhar over the years at Chicago, carrying out complex numerical calculations that fed into his results in stellar structures, stellar dynamics, and most of the other topics on which he made major impact. It is a sobering aspect of the issue of women’s under-recognized contributions across the sciences that I am going to have to stop to look up her name, though she was parodied as Canna Helpit in a paper supposed to be by S. Candlestickmaker (meaning Chandra, whose 1983 Physics Nobel Prize primarily recognized work done 50 years earlier, before he had her or other computational assistants). His papers generally recognize her role, and some of his autobiographical material records her as catching and correcting mistakes in his own calculations. She does not, however, generally appear as a co-author, though his work would surely have proceeded more slowly without her input.

I return triumphant with the name of Donna Elbert (1928–2010) who worked with Chandra from 1948 to 1979, and whose name (thank you, Astrophysics Data System) appeared as co-author on 17 of his 187 astronomy papers published during those years. She wrote (after Chandra’s death) about working with him, and a postdoctoral fellow at UCLA celebrated her in a press release on September 18, 2022. What can or should we do about all this? Does it help to write and edit books? Such was not the primary motivation for Dr. Weintraub and me—though we hope it won’t hurt!

David Weintraub | The Sky Is for Everyone: Women Astronomers in Their Own Words

In helping Virginia Trimble compile autobiographical essays by women astronomers, I learned something particularly eye-opening from one of our chapter authors. Meg Urry is the Israel Munson Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Yale. She wrote about an encounter she had with a male astrophysicist during her postdoctoral years at MIT. At a dinner one night, the senior scientist, believing himself to be an expert on the subject, announced that there had never been any good women artists. Urry’s response to this assertion comes from a famous essay by Linda Nochlin entitled “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Nochlin explains, “As we all know, things as they are and as they have been, in the arts as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive, and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male. The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education.”

“Histories that include women are exceptions because the victors usually write the histories. And women, historically, have not even been participants in the fight, let alone the victors.”

And so, women have been excluded from histories of art, of science, of literature, of politics—the list of excluded areas of human endeavor is nearly unbounded. This we know. But why? The answer is simple: Throughout most of human history and in most cultures, they have been—and even continue to be—excluded from actively working in the professions of art, of science, of literature, of politics, and so much more. A person cannot be written into the story if that person is not allowed in the room.

So, what have I learned? My eyes and ears are more open. I am more attuned to and notice the double standards and barriers still placed before my female colleagues. And I am much more aware that many changes are still needed before the playing fields are level. I also recognize that this story is repeating itself. Most professions still are exclusionary. In many countries, those excluded are still women. In other countries, the “firsts” are no longer women; instead, they are persons of color or those whose sexuality is nonbinary. Histories that include women are exceptions because the victors usually write the histories. And women, historically, have not even been participants in the fight, let alone the victors. These histories open our eyes to what might have been and to what should be. The latter is more important, and these histories might help us reach a better, more inclusive future much sooner.

This exchange was facilitated by Akhil Jonnalagadda as part of the Princeton University Press Publishing Fellowship program .

Stay connected for new books and special offers. Subscribe to receive a welcome discount for your next order.

- ebook & Audiobook Cart

The history of women’s work and wages and how it has created success for us all

As we celebrate the centennial of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, we should also celebrate the major strides women have made in the labor market. Their entry into paid work has been a major factor in America’s prosperity over the past century and a quarter.

Despite this progress, evidence suggests that many women remain unable to achieve their goals. The gap in earnings between women and men, although smaller than it was years ago, is still significant; women continue to be underrepresented in certain industries and occupations; and too many women struggle to combine aspirations for work and family. Further advancement has been hampered by barriers to equal opportunity and workplace rules and norms that fail to support a reasonable work-life balance. If these obstacles persist, we will squander the potential of many of our citizens and incur a substantial loss to the productive capacity of our economy at a time when the aging of the population and weak productivity growth are already weighing on economic growth.

A historical perspective on women in the labor force

In the early 20th century, most women in the United States did not work outside the home, and those who did were primarily young and unmarried. In that era, just 20 percent of all women were “gainful workers,” as the Census Bureau then categorized labor force participation outside the home, and only 5 percent of those married were categorized as such. Of course, these statistics somewhat understate the contributions of married women to the economy beyond housekeeping and childrearing, since women’s work in the home often included work in family businesses and the home production of goods, such as agricultural products, for sale. Also, the aggregate statistics obscure the differential experience of women by race. African American women were about twice as likely to participate in the labor force as were white women at the time, largely because they were more likely to remain in the labor force after marriage.

If these obstacles persist, we will squander the potential of many of our citizens and incur a substantial loss to the productive capacity of our economy at a time when the aging of the population and weak productivity growth are already weighing on economic growth.

The fact that many women left work upon marriage reflected cultural norms, the nature of the work available to them, and legal strictures. The occupational choices of those young women who did work were severely circumscribed. Most women lacked significant education—and women with little education mostly toiled as piece workers in factories or as domestic workers, jobs that were dirty and often unsafe. Educated women were scarce. Fewer than 2 percent of all 18- to 24-year-olds were enrolled in an institution of higher education, and just one-third of those were women. Such women did not have to perform manual labor, but their choices were likewise constrained.

Despite the widespread sentiment against women, particularly married women, working outside the home and with the limited opportunities available to them, women did enter the labor force in greater numbers over this period, with participation rates reaching nearly 50 percent for single women by 1930 and nearly 12 percent for married women. This rise suggests that while the incentive—and in many cases the imperative—remained for women to drop out of the labor market at marriage when they could rely on their husband’s income, mores were changing. Indeed, these years overlapped with the so-called first wave of the women’s movement, when women came together to agitate for change on a variety of social issues, including suffrage and temperance, and which culminated in the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 guaranteeing women the right to vote.

Between the 1930s and mid-1970s, women’s participation in the economy continued to rise, with the gains primarily owing to an increase in work among married women. By 1970, 50 percent of single women and 40 percent of married women were participating in the labor force. Several factors contributed to this rise. First, with the advent of mass high school education, graduation rates rose substantially. At the same time, new technologies contributed to an increased demand for clerical workers, and these jobs were increasingly taken on by women. Moreover, because these jobs tended to be cleaner and safer, the stigma attached to work for a married woman diminished. And while there were still marriage bars that forced women out of the labor force, these formal barriers were gradually removed over the period following World War II.

Over the decades from 1930 to 1970, increasing opportunities also arose for highly educated women. That said, early in that period, most women still expected to have short careers, and women were still largely viewed as secondary earners whose husbands’ careers came first.

As time progressed, attitudes about women working and their employment prospects changed. As women gained experience in the labor force, they increasingly saw that they could balance work and family. A new model of the two-income family emerged. Some women began to attend college and graduate school with the expectation of working, whether or not they planned to marry and have families.

By the 1970s, a dramatic change in women’s work lives was under way. In the period after World War II, many women had not expected that they would spend as much of their adult lives working as turned out to be the case. By contrast, in the 1970s young women more commonly expected that they would spend a substantial portion of their lives in the labor force, and they prepared for it, increasing their educational attainment and taking courses and college majors that better equipped them for careers as opposed to just jobs.

These changes in attitudes and expectations were supported by other changes under way in society. Workplace protections were enhanced through the passage of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act in 1978 and the recognition of sexual harassment in the workplace. Access to birth control increased, which allowed married couples greater control over the size of their families and young women the ability to delay marriage and to plan children around their educational and work choices. And in 1974, women gained, for the first time, the right to apply for credit in their own name without a male co-signer.

By the early 1990s, the labor force participation rate of prime working-age women—those between the ages of 25 and 54—reached just over 74 percent, compared with roughly 93 percent for prime working-age men. By then, the share of women going into the traditional fields of teaching, nursing, social work, and clerical work declined, and more women were becoming doctors, lawyers, managers, and professors. As women increased their education and joined industries and occupations formerly dominated by men, the gap in earnings between women and men began to close significantly.

Remaining challenges and some possible solutions

We, as a country, have reaped great benefits from the increasing role that women have played in the economy. But evidence suggests that barriers to women’s continued progress remain. The participation rate for prime working-age women peaked in the late 1990s and currently stands at about 76 percent. Of course, women, particularly those with lower levels of education, have been affected by the same economic forces that have been pushing down participation among men, including technical change and globalization. However, women’s participation plateaued at a level well below that of prime working-age men, which stands at about 89 percent. While some married women choose not to work, the size of this disparity should lead us to examine the extent to which structural problems, such as a lack of equal opportunity and challenges to combining work and family, are holding back women’s advancement.

Recent research has shown that although women now enter professional schools in numbers nearly equal to men, they are still substantially less likely to reach the highest echelons of their professions.

The gap in earnings between men and women has narrowed substantially, but progress has slowed lately, and women working full time still earn about 17 percent less than men, on average, each week. Even when we compare men and women in the same or similar occupations who appear nearly identical in background and experience, a gap of about 10 percent typically remains. As such, we cannot rule out that gender-related impediments hold back women, including outright discrimination, attitudes that reduce women’s success in the workplace, and an absence of mentors.

Recent research has shown that although women now enter professional schools in numbers nearly equal to men, they are still substantially less likely to reach the highest echelons of their professions. Even in my own field of economics, women constitute only about one-third of Ph.D. recipients, a number that has barely budged in two decades. This lack of success in climbing the professional ladder would seem to explain why the wage gap actually remains largest for those at the top of the earnings distribution.

One of the primary factors contributing to the failure of these highly skilled women to reach the tops of their professions and earn equal pay is that top jobs in fields such as law and business require longer workweeks and penalize taking time off. This would have a disproportionately large effect on women who continue to bear the lion’s share of domestic and child-rearing responsibilities.

But it can be difficult for women to meet the demands in these fields once they have children. The very fact that these types of jobs require such long hours likely discourages some women—as well as men—from pursuing these career tracks. Advances in technology have facilitated greater work-sharing and flexibility in scheduling, and there are further opportunities in this direction. Economic models also suggest that while it can be difficult for any one employer to move to a model with shorter hours, if many firms were to change their model, they and their workers could all be better off.

Of course, most women are not employed in fields that require such long hours or that impose such severe penalties for taking time off. But the difficulty of balancing work and family is a widespread problem. In fact, the recent trend in many occupations is to demand complete scheduling flexibility, which can result in too few hours of work for those with family demands and can make it difficult to schedule childcare. Reforms that encourage companies to provide some predictability in schedules, cross-train workers to perform different tasks, or require a minimum guaranteed number of hours in exchange for flexibility could improve the lives of workers holding such jobs. Another problem is that in most states, childcare is affordable for fewer than half of all families. And just 5 percent of workers with wages in the bottom quarter of the wage distribution have jobs that provide them with paid family leave. This circumstance puts many women in the position of having to choose between caring for a sick family member and keeping their jobs.

This possibility should inform our own thinking about policies to make it easier for women and men to combine their family and career aspirations. For instance, improving access to affordable and good quality childcare would appear to fit the bill, as it has been shown to support full-time employment. Recently, there also seems to be some momentum for providing families with paid leave at the time of childbirth. The experience in Europe suggests picking policies that do not narrowly target childbirth, but instead can be used to meet a variety of health and caregiving responsibilities.

The United States faces a number of longer-term economic challenges, including the aging of the population and the low growth rate of productivity. One recent study estimates that increasing the female participation rate to that of men would raise our gross domestic product by 5 percent. Our workplaces and families, as well as women themselves, would benefit from continued progress. However, a number of factors appear to be holding women back, including the difficulty women currently have in trying to combine their careers with other aspects of their lives, including caregiving. In looking to solutions, we should consider improvements to work environments and policies that benefit not only women, but all workers. Pursuing such a strategy would be in keeping with the story of the rise in women’s involvement in the workforce, which has contributed not only to their own well-being but more broadly to the welfare and prosperity of our country.

This essay is a revised version of a speech that Janet Yellen, then chair of the Federal Reserve, delivered on May 5, 2017 at the “125 Years of Women at Brown Conference,” sponsored by Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Yellen would like to thank Stephanie Aaronson, now vice president and director of Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, for her assistance in the preparation of the original remarks. Read the full text of the speech here »

About the Author

Janet l. yellen, distinguished fellow in residence – economic studies, the hutchins center on fiscal and monetary policy, more from janet yellen.

Former Fed chair Janet Yellen on gender and racial diversity of the federal government’s economists

Janet Yellen delivered this remark at the public event, “The gender and racial diversity of the federal government’s economists” by Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy at Brookings on September 23, 2019.

The gender and racial diversity of the federal government’s economists

The lack of diversity in the field of economics – in addition to the lack of progress relative to other STEM fields – is drawing increasing attention in the profession, but nearly all the focus has been on economists at academic institutions, and little attention has been devoted to the diversity of the economists employed […]

MORE FROM THE 19A SERIES

Leaving all to younger hands: Why the history of the women’s suffragist movement matters

Dr. Susan Ware places the passage of the 19th Amendment in its appropriate historical context, highlights its shortfalls, and explains why celebrating the Amendment’s complex history matters.

Women warriors: The ongoing story of integrating and diversifying the American armed forces

General (ret.) Lori J. Robinson and Michael O’Hanlon discuss the strides made toward greater participation of women in the U.S. military, and the work still to be done to ensure equitable experiences for all service members.

Women’s work boosts middle class incomes but creates a family time squeeze that needs to be eased

Middle-class incomes have risen modestly in recent decades, and most of any gains in their incomes are the result of more working women. Isabel Sawhill and Katherine Guyot explain the important role women play in middle class households and the challenges they face, including family “time squeeze.”

- Media Relations

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

National Archives News

Women’s History

Suffrage parade in Washington, DC, March 3, 1913. View in National Archives Catalog

Records in the National Archives document the great contributions that women have made to our nation. Learn about the history of women in the United States by exploring their stories through letters, photographs, film, and other primary sources. Explore the records featured here, and view selected images from the National Archives Catalog .

In 2020, the nation observed the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the states from denying the vote on the basis of sex. The exhibit Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote looked beyond suffrage parades and protests to the often overlooked story behind ratification.

In support of the centennial of the 19th Amendment, we posted several video messages from notable women sharing their personal views about the 19th Amendment and addressing the complex history and legacy of this milestone anniversary. View the entire playlist on YouTube .

Women's Rights Topics

Research topics.

Equal Rights Amendment

Legislation and Advocacy

Notable Women

|

Written in 1921 by suffragist Alice Paul, the Equal Rights Amendment was introduced into every session of Congress between 1923 and 1972. A panel explores the proposed amendment and its implications in today's world. | |

|

Political communicators and strategists discuss their experiences working on political campaigns on both local and national levels, the changes in opportunities and obstacles, and advice for young women looking to become more involved in politics. | |

|

Joelle Gamble, Director of National Network of Emerging Thinkers, Roosevelt Institute, shares her experience as an emerging generation. | |

|

First Ladies have long the power to shape societal attitudes and used their platform to advocate for important issues. This conference focuses on the First Lady as spouse of the Commander in Chief and the actions they have taken, throughout times of war and peace, to support Americans in combat, military families, and the country's veterans. | |

|

In celebration of the March 2017 grand opening of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor’s Center, we join the National Park Service in presenting a panel discussion examining the life and legacy of Harriet Tubman and the ongoing preservation of her Maryland | |

|

Madam C.J. Walker, one of the great American entrepreneurs of the early 20th century, was born to former slaves and grew up in destitution. |

Additional Videos

Women’s History on the Horizon: The Centennial of Woman Suffrage in 2020

The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

Women’s Suffrage and the Vote: Funding Feminism

The Equal Rights Amendment: Yesterday and Today

Temperance and Woman Suffrage: Reform Movements and the Women Who Changed America

Women and the Supreme Court

Women’s History Month Program: The Glass Ceiling, Broken or Cracked?

Women's History Month Spotlight: National Archives Employee Adrienne Thomas

"Feminism" and Women of Color, National Conversation on #RightsAndJustice (Q&A with Soledad O'Brien)

National Conversations on Rights and Justice Women's Rights and Gender Equality

The Declaration of Independence: A Conversation with a Conservator

Historical Footage

Women and the Spirit of '76 (1976)

Decade of Our Destiny: Women—A New Force for Change (1976)

American Women and Social Change—Women at Work (1975)

Space for Women (NASA, 1981)

Women in Defense (1941)

Women on the Warpath (1943)

Education Resources

Education Updates: Women’s Suffrage Posters & Displays

Education Updates: New Women’s Rights Teaching Resources

DocsTeach activities on Women's Rights

DocsTeach page on "Rights in America,” with primary sources on Women's Rights

DocsTeach page on "1970s America,” with primary sources on Women's Rights

The Suffrage and the Civil Rights Reform Movements

Woman Suffrage and the 19th Amendment

Failure Is Impossible, a one-act play

Women's Suffrage Party Petition

Examining Rosa Parks's Arrest Record

Harriet Tubman’s Claim for a Pension

Woman’s Place in America: Congress and Woman Suffrage

AOTUS: Remembering Cokie

Ford in Focus: I’ll Race You for It!

Forward with Roosevelt: A First Lady on the Front Lines

Forward with Roosevelt: Eleanor Roosevelt's Battle to End Lynching

Forward with Roosevelt: Missy LeHand: FDR’s Right Hand Woman

Hoover Heads: Tempest in a Teapot – Lou Henry Hoover and the DePriest Tea Incident

Hoover Heads: Who is Anne Martin?

JFK Library—Archivally Speaking: Finding Inspiration in the Archives: Honoring Women at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library

JFK Library—Archivally Speaking: Personal Recollections of Corinne “Lindy” Boggs

JFK Library—Archivally Speaking: Restoring the Past in the White House: A Look at the Jacqueline Kennedy White House Restoration Project

NARAtions: The Making of Women’s Equality Day

Pieces of History: On the Basis of Sex: Equal Credit Opportunities

Pieces of History: On the Basis of Sex: Equal Pay

Pieces of History: Minnie Spotted Wolf

Pieces of History: The Hello Girls Finally Get Paid

Pieces of History: Finding the Girl in the Photograph

Pieces of History: Suffrage and Suffering at the 1913 March

Explore more posts in Pieces of History

Reagan Library Education Blog: "Remembering the Ladies" Blog Series

Text Message: Meet Sgt. Eva Mirabal/Eah Ha Wa (Taos Pueblo); Women’s Army Corps Artist

Text Message: An Indigenous Woman’s Legal Fight After Forced Sterilization

Text Message: The Closed Door of Justice: African American Nurses and the Fight for Naval Service

Text Message: The First Woman to Fly in an Aeroplane in the United States, October 27, 1909

Explore most posts in the Text Message

Unwritten Record: Queens of the Air: American Women Aviation Pioneers

Unwritten Record: Celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Title IX with Archival Footage of Sporting Legends

Unwritten Record: International Worker’s Day and the Female Workforce

Unwritten Record: No Mail, Low Morale: The 6888th Central Postal Battalion

Unwritten Record: Their War Too: U.S. Women in the Military During WWII, part 1 and part 2

Explore more in the Unwritten Record

Prologue Magazine Articles

From Slave Women to Free Women

View in National Archives Catalog

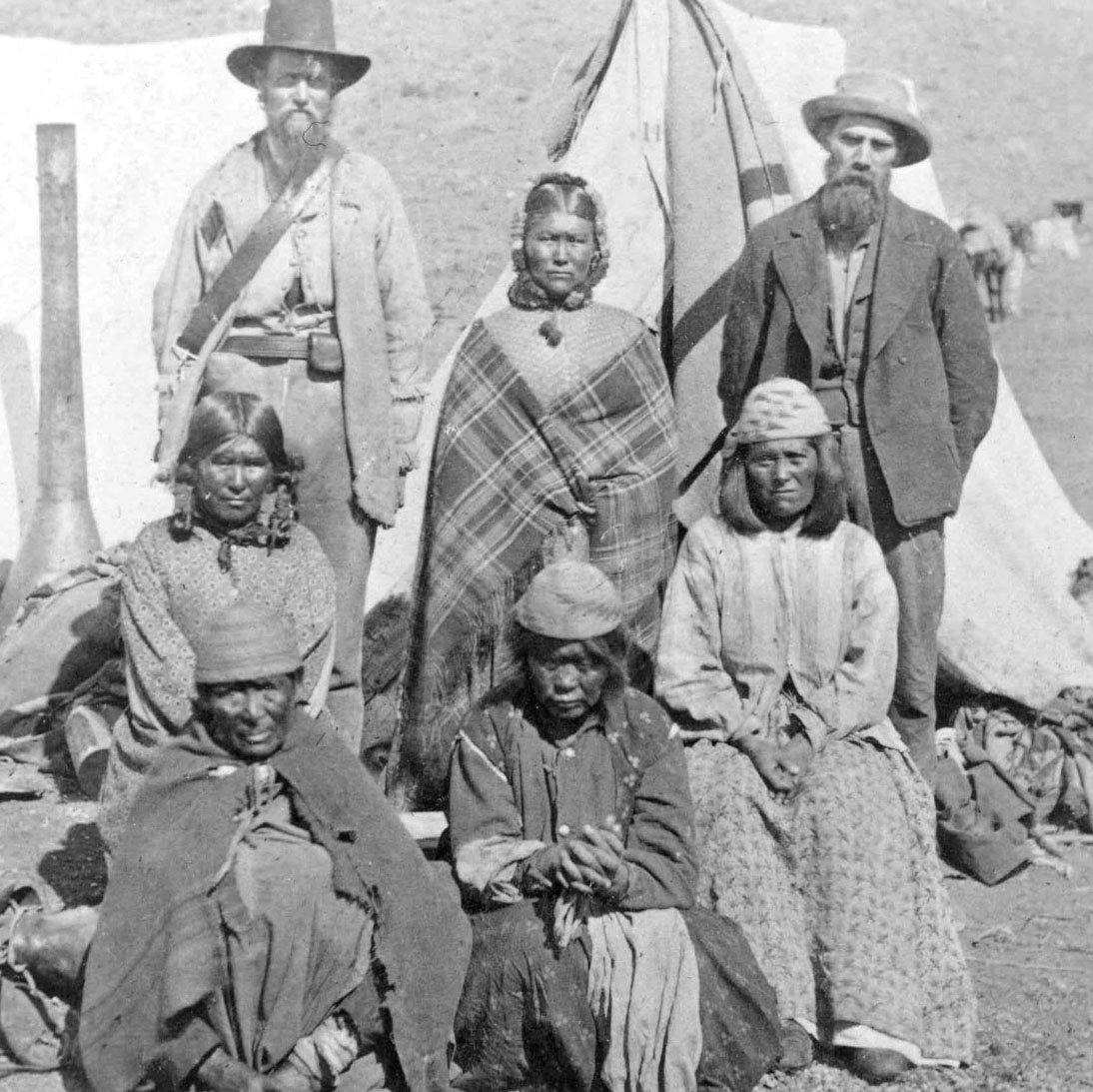

Winema and the Modoc War

“To the Rescue of the Crops”: The Women’s Land Army During World War II (16-G-323-4-N-4750)

Taking a Stand for Voting Rights

Belva Lockwood: Blazing the Trail for Women in Law

The Rejection of Elizabeth Mason: The Case of a “Free Colored” Revolutionary Widow

From Slave Women to Free Women: The National Archives and Black Women's History in the Civil War Era Women Soldiers of the Civil War

Winema and the Modoc War: One Woman’s Struggle for Peace

Women and Naturalization, ca. 1802–1940

When Saying "I Do" Meant Giving Up Your U.S. Citizenship

“Any woman who is now or may hereafter be married . . .” Women and Naturalization, ca. 1802–1940

The Story of the Female Yeomen during the First World War

World War I Gold Star Mothers, Part 1 ; Part 2

Women of the Polar Archives

“To the Rescue of the Crops”: The Women’s Land Army During World War II

Wearing Lipstick to War: An American Woman in World War II England and France

Women Workers in Wartime >

Online Exhibits

Rightfully Her: American Women and the Vote

Rightfully Hers, created for the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, looked beyond suffrage parades and protests to the often overlooked story behind ratification.

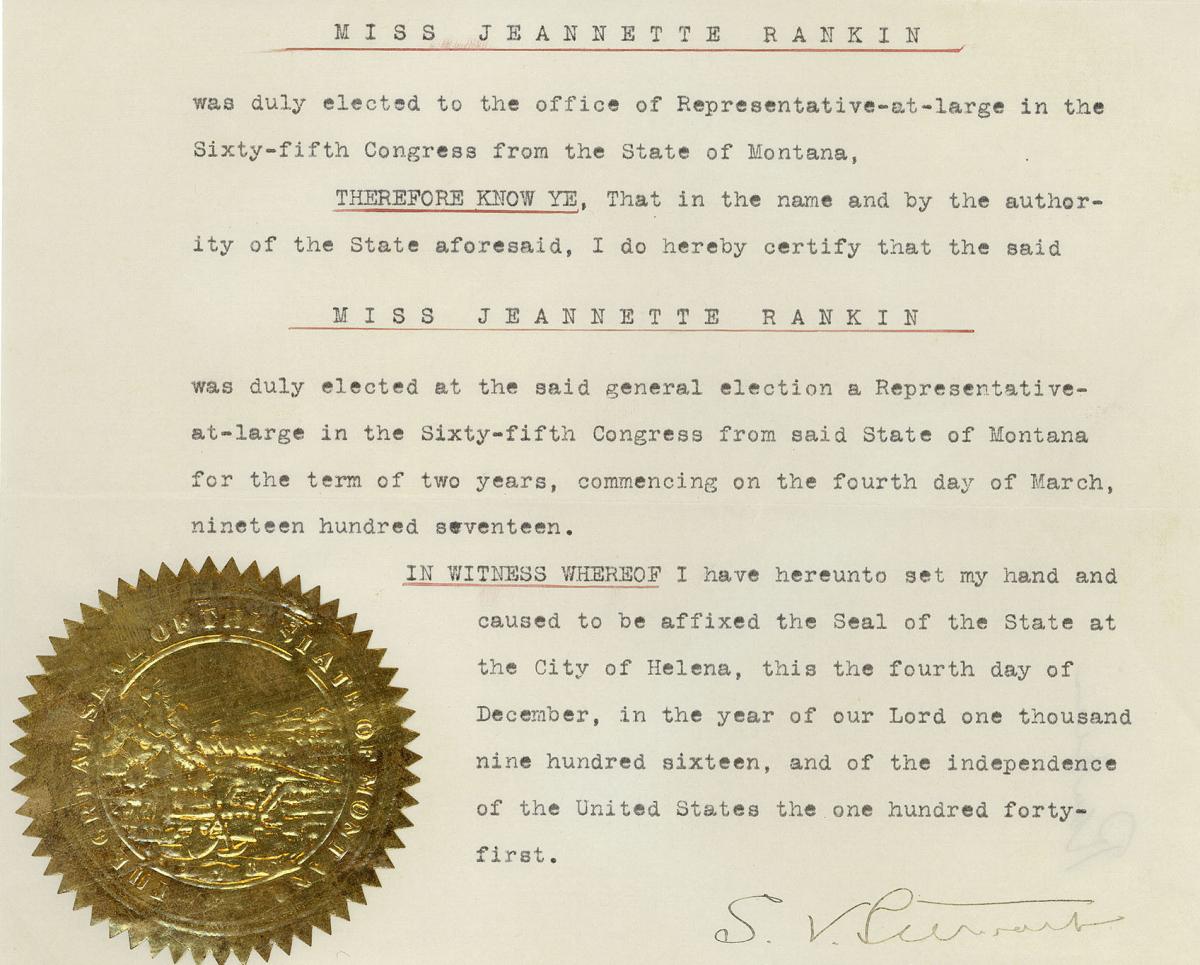

100th Anniversary of Jeannette Rankin as First Congresswoman

Jeannette Rankin's 1917 credentials as a Member of the House of Representatives were displayed at the National Archives in Washington, DC.

Records of Rights

The Records of Rights exhibit in Washington, DC, and online tells the story of women's rights.

The U.S. Food Administration, Women, and the Great War

Women played a key role in food conservation during World War I.

Eleanor Roosevelt and the United Nations

After leaving the White House Eleanor Roosevelt became the first woman to represent the United States as a delegate to the United Nations.

Amending America: Women's Rights

Explore selected stories about civil rights and individual freedoms featured at our National Conversation on #RightsAndJustice: Women's Rights and Gender Equality in New York City.

A People at War: Women Who Served

Although women were not allowed to participate in battle during World War II, they did serve in so-called "noncombat" missions in the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) and Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).. These missions often proved to be extremely dangerous.

From the Presidential Libraries

Franklin d. roosevelt library.

Eleanor Roosevelt's Press Conferences

It's Up To The Women

Dwight D. Eisenhower Library

Women in Politics in the 1950s

Jacqueline Cochran and the Women's Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs)

Women Unite for Ike (online exhibit)

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library

Records of the Commission on the Status of Women

JFK’s remarks on the President's Commission on the Status of Women’s Final Report

Resources on Women’s Rights

Gerald R. Ford Library

George w. bush library.

Gale A. Norton, First Woman to be Secretary of the Interior

Ann Veneman, Frst Woman to be Secretary of Agriculture

Condoleezza Rice, First African American Woman to be Secretary of State

Cristeta Comerford, First Woman to be Named White House Executive Chef

Elaine L. Chao, first Asian American woman to be Secretary of Labor

The First Lady & Her Role

Speeches by First Lady Laura Bush

Mrs. Laura Bush’s Leadership

Mrs. Bush's Remarks to Women CEOs

Laura Bush and the President’s Radio Address

First Lady Laura Bush’s radio address about treatment of women & children by the Taliban in Afghanistan

Flickr Sets

Women in World War II

Women’s Rights

Girl Scouts

Women’s Bureau

Selected Images

Astronauts Ellen Ochoa, Julie Payette and, Tamara Jernigan with a National Women's Party banner in the International Space Station in 1999. View in National Archives Catalog

Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson in Japan, May 22, 1953. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Library)

Frances Perkins meets with Carnegie Steel Workers, 1933. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Library)

First Lady Betty Ford with members of the National Women’s Party following the presentation of the first Alice Paul Award to Mrs. Ford in the Map Room at the White House, January 11, 1977. View in National Archives Catalog

Swearing-in ceremony for Madeleine Albright as Secretary of State, January 23, 1997 (Photo by Ralph Alswang). View in National Archives Catalog

National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice in the Oval Office, September 18, 2001 (Photo by Tina Hager). View in National Archives Catalog

Kamala Harris was sworn in as the first woman Vice President of the United States on January 20, 2021. In this picture, President Barack Obama greets Harris, then California's Attorney General, at a White House meeting on criminal justice on April 4, 2014. View in National Archives Catalog

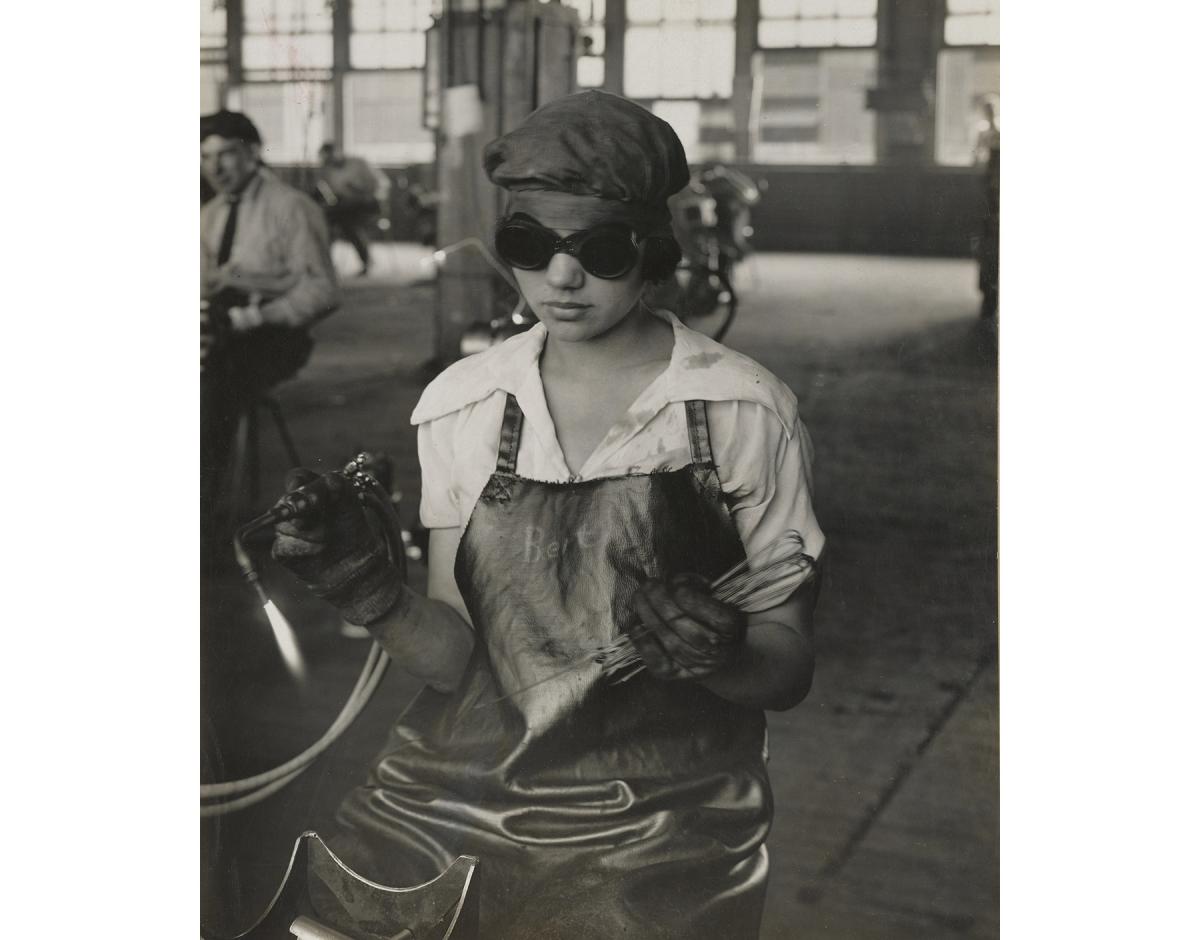

A woman works on Liberty airplane engines at the Packard Motor Company in Detroit during World War I. View in National Archives Catalog

Amelia Earhart, July 30, 1936. View in National Archives Catalog

Three female lumberjacks walk up a log chute from Turkey Pond in New Hampshire, November 10, 1942. They had been rolling logs in the pond, pulling them to the log chute. View in National Archives Catalog

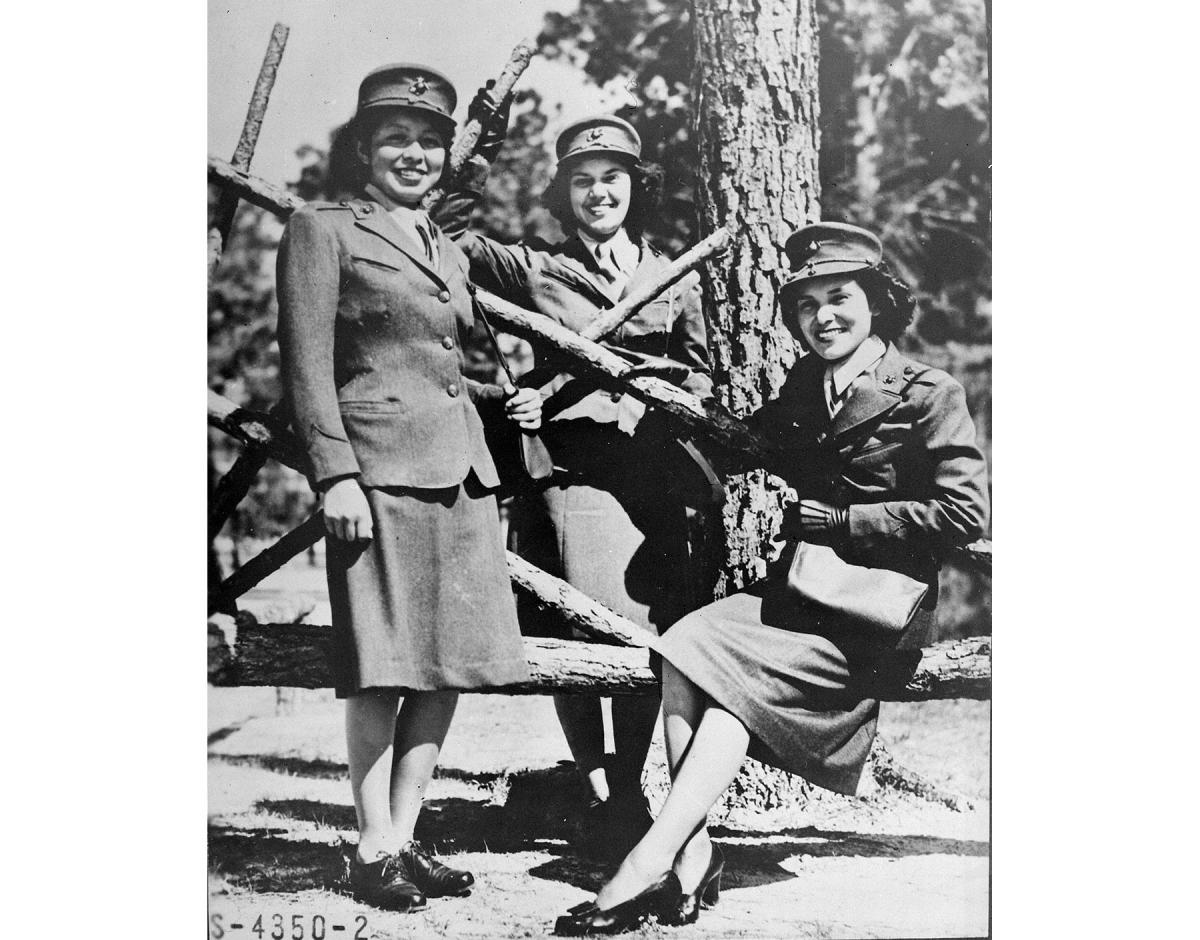

Native American women served in the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II. Left to right: Minnie Spotted Wolf (Blackfeet), Celia Mix (Potawatomi), and Violet Eastman (Chippewa). View in National Archives Catalog

Maj. Charity E. Adams and Capt. Abbie N. Campbell inspect women of the 6888th Central Postal Battalion, assigned to duty in England, February 1945. View in National Archives Catalog

Native women of the village of Ambler ice fishing for whitefish. View in National Archives Catalog

A woman scientist working for NASA, October 17, 1978 (Photo by Hank Seidel). View in National Archives Catalog

Blanca Tomé of the National Archives Document Preservation Branch, 1974. View in National Archives Catalog

History of the Women’s Rights Movement

Living the Legacy: The Women’s Rights Movement (1848-1998)

“ Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has. ” That was Margaret Mead’s conclusion after a lifetime of observing very diverse cultures around the world. Her insight has been borne out time and again throughout the development of this country of ours. Being allowed to live life in an atmosphere of religious freedom, having a voice in the government you support with your taxes, living free of lifelong enslavement by another person. These beliefs about how life should and must be lived were once considered outlandish by many. But these beliefs were fervently held by visionaries whose steadfast work brought about changed minds and attitudes. Now these beliefs are commonly shared across U.S. society.

Another initially outlandish idea that has come to pass: United States citizenship for women. 1998 marked the 150th Anniversary of a movement by women to achieve full civil rights in this country. Over the past seven generations, dramatic social and legal changes have been accomplished that are now so accepted that they go unnoticed by people whose lives they have utterly changed. Many people who have lived through the recent decades of this process have come to accept blithely what has transpired. And younger people, for the most part, can hardly believe life was ever otherwise. They take the changes completely in stride, as how life has always been.

The staggering changes for women that have come about over those seven generations in family life, in religion, in government, in employment, in education – these changes did not just happen spontaneously. Women themselves made these changes happen, very deliberately. Women have not been the passive recipients of miraculous changes in laws and human nature. Seven generations of women have come together to affect these changes in the most democratic ways: through meetings, petition drives, lobbying, public speaking, and nonviolent resistance. They have worked very deliberately to create a better world, and they have succeeded hugely.

Throughout 1998, the 150th anniversary of the Women’s Rights Movement is being celebrated across the nation with programs and events taking every form imaginable. Like many amazing stories, the history of the Women’s Rights Movement began with a small group of people questioning why human lives were being unfairly constricted.

A Tea Launches a Revolution The Women’s Rights Movement marks July 13, 1848 as its beginning. On that sweltering summer day in upstate New York, a young housewife and mother, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was invited to tea with four women friends. When the course of their conversation turned to the situation of women, Stanton poured out her discontent with the limitations placed on her own situation under America’s new democracy. Hadn’t the American Revolution had been fought just 70 years earlier to win the patriots freedom from tyranny? But women had not gained freedom even though they’d taken equally tremendous risks through those dangerous years. Surely the new republic would benefit from having its women play more active roles throughout society. Stanton’s friends agreed with her, passionately. This was definitely not the first small group of women to have such a conversation, but it was the first to plan and carry out a specific, large-scale program.

Today we are living the legacy of this afternoon conversation among women friends. Throughout 1998, events celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the Women’s Rights Movement are looking at the massive changes these women set in motion when they daringly agreed to convene the world’s first Women’s Rights Convention.

Within two days of their afternoon tea together, this small group had picked a date for their convention, found a suitable location, and placed a small announcement in the Seneca County Courier. They called “A convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman.” The gathering would take place at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls on July 19 and 20, 1848.

In the history of western civilization, no similar public meeting had ever been called.

A “Declaration of Sentiments” is Drafted These were patriotic women, sharing the ideal of improving the new republic. They saw their mission as helping the republic keep its promise of better, more egalitarian lives for its citizens. As the women set about preparing for the event, Elizabeth Cady Stanton used the Declaration of Independence as the framework for writing what she titled a “Declaration of Sentiments.” In what proved to be a brilliant move, Stanton connected the nascent campaign for women’s rights directly to that powerful American symbol of liberty. The same familiar words framed their arguments: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

In this Declaration of Sentiments, Stanton carefully enumerated areas of life where women were treated unjustly. Eighteen was precisely the number of grievances America’s revolutionary forefathers had listed in their Declaration of Independence from England.

Stanton’s version read, “The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.” Then it went into specifics:

- Married women were legally dead in the eyes of the law

- Women were not allowed to vote

- Women had to submit to laws when they had no voice in their formation

- Married women had no property rights