Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- U.S. Muslims Concerned About Their Place in Society, but Continue to Believe in the American Dream

- 2. Identity, assimilation and community

Table of Contents

- 1. Demographic portrait of Muslim Americans

- 3. The Muslim American experience in the Trump era

- 4. Political and social views

- 5. Terrorism and concerns about extremism

- 6. Religious beliefs and practices

- 7. How the U.S. general public views Muslims and Islam

- Acknowledgements

- Appendix A: Glossary

- Appendix B: Survey methodology

Muslim Americans overwhelmingly embrace both the “Muslim” and “American” parts of their identity. For instance, the vast majority of U.S. Muslims say they are proud to be American (92%), while nearly all say they are proud to be Muslim (97%). Indeed, about nine-in-ten (89%) say they are proud to be both Muslim and American.

Muslim Americans also see themselves as integrated into American society in other important ways. Four-in-five say they are satisfied with the way things are going in their lives in America, and six-in-ten say they have “a lot” in common with most Americans. In addition, a declining share of U.S. Muslims say that “all” or “most” of their close friends are also Muslim.

Yet, in other ways, many Muslims feel they stand out in America. For example, about four-in-ten say there is something distinctive about their appearance, voice or clothing that people might associate with being Muslim. This includes most women who regularly wear hijab, but also one-in-four women who do not wear hijab regularly and about a quarter of men who also say there is something distinctively Muslim about their appearance. In addition, three-quarters of Muslim Americans say they feel a strong sense of belonging to the global ummah, or Muslim community, and 80% say they feel a strong tie to Muslim communities in the U.S. – though follow-up interviews highlight the ambiguity of these concepts, even for Muslims who say this.

This chapter also explores other aspects of identity, including what Muslims see as essential to their religious identity and key values and goals in life more broadly.

Most U.S. Muslims proud to be American, satisfied with life

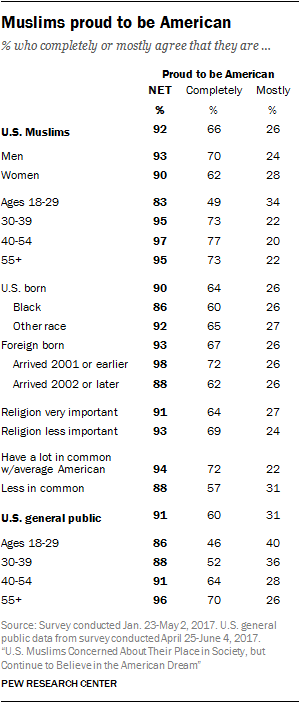

Nine-in-ten U.S. Muslims agree either completely (66%) or mostly (26%) with the statement, “I am proud to be American.” Only a handful of U.S. Muslims disagree with this statement either completely (4%) or mostly (2%).

Muslim immigrants are at least as likely as U.S.-born Muslims to express pride in being American. At the same time, immigrants who have been in the U.S. for longer are somewhat more likely than recent immigrants to say they are proud to be American.

Muslim adults younger than 30 are less likely than older Muslims to say they are proud to be American. The same pattern is evident among the population as a whole.

Among Muslims, pride in being American does not vary significantly based on the importance of religion in their lives. On the other hand, Muslims who say they have a lot in common with most Americans are considerably more likely than those who have less in common to completely agree that they are proud to be American (72% vs. 57%).

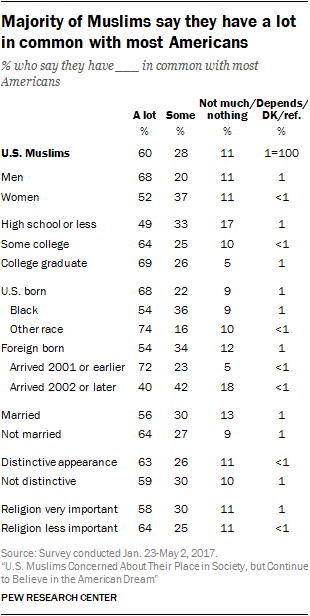

When asked how much they have in common with “most Americans,” six-in-ten U.S. Muslims (60%) say they have “a lot” in common. Another 28% say they have “some” in common, and about one-in-ten say they have “not much” (8%) or “nothing at all” (3%) in common with most Americans.

More Muslim men than women (68% vs. 52%) say they have a lot in common with most Americans. And about seven-in-ten Muslim college graduates say they have a lot in common with the average American, compared with only about half of those who have a high school degree or less.

U.S.-born Muslims (68%) are more likely than immigrants (54%) to say they have a lot in common with most Americans, but within these groups there also are important differences. For example, a much smaller share of recent immigrants say they have a lot in common (40%) compared with those who have been in the U.S. longer (72%).

Muslims who say there is something distinctive about their appearance that indicates their Muslim identity are no less likely than those who say there is nothing distinctive about their appearance to say they have a lot in common with most Americans.

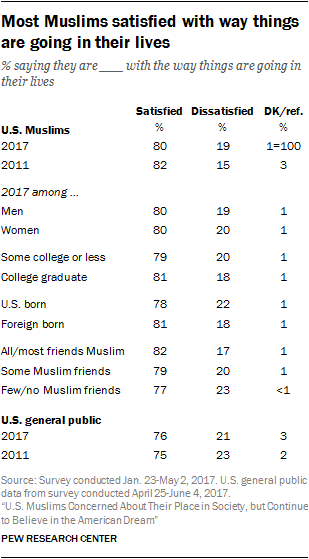

Four out of five U.S. Muslims (80%) say they are satisfied with the way things are going in their lives. In fact, Muslims remain about as satisfied with their lives as they were in 2011 (82%). Satisfaction among Muslim Americans is similar to feelings among those in the larger U.S. public.

Life satisfaction is relatively consistent among Muslim men and women, Muslims of varying levels of education, and immigrant and U.S.-born Muslims.

Muslims today less likely to say most of their friends are Muslim

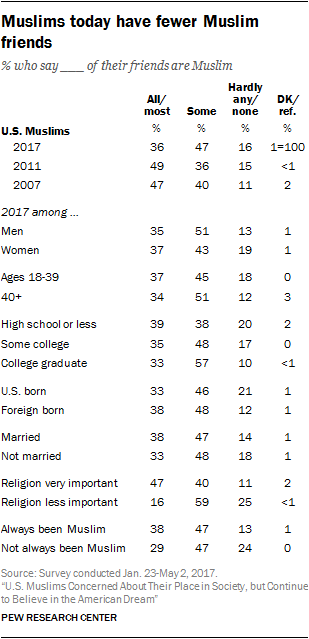

About one-in-three U.S. Muslims say all (5%) or most (31%) of their close friends are Muslim. About half (47%) say some of their friends are Muslim, and roughly one-in-six say hardly any of their friends are Muslim (15%) or that they have no Muslim friends (1%).

A smaller share of Muslims today say that all or most of their friends are Muslim compared with 2011 or 2007, when about half of U.S. Muslims said this.

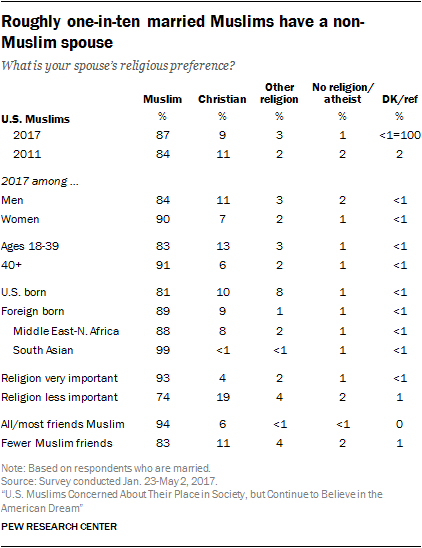

Muslims who say religion is very important to them are much more likely to say that all or most of their friends are Muslim than are those who say religion is less important. As in years past, most married U.S. Muslims have a spouse who is also Muslim (87%). Just 9% have a Christian spouse, 1% are married to someone who has no religious affiliation and 3% are married to someone of another faith. These figures are little changed since 2011.

While differences in question wording make direct comparisons difficult, surveys generally find that those in other religious groups also have a tendency to marry within their faith. Pew Research Center’s 2014 U.S. Religious Landscape Study, for example, found that 90% of married Christians are wedded to another Christian. And a 2013 Pew Research Center survey of U.S. Jews found that 64% of Jews are married to a Jewish spouse. 26

Married Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives are far more likely to have a Muslim spouse than those who say religion is less important (93% vs. 74%). And U.S. Muslims whose close friends are mostly or all Muslims are more likely than those with fewer Muslim friends to have a Muslim spouse (94% vs. 83%).

In their own words: What Muslims said about their friends and family

Pew Research Center staff called back some of the Muslim American respondents in this survey to get additional thoughts on some of the topics covered. Here is a sampling of what they said about their Muslim and non-Muslim friends and family: “I don’t have many Muslim friends here in the U.S. simply because I don’t really practice my religion. I don’t go to mosque or many places where I can meet groups of Muslims. So my friendship relationships are mainly with coworkers or things like that. So that’s why I don’t have many Muslim friends. … Ninety-nine percent of people, once they know I am Muslim, they assume my wife had to convert to Islam or that she’s Muslim. And that’s not the case. My wife is not a Muslim; she didn’t convert. That’s an interesting thing – when everyone knows I’m Muslim, they assume she’s Muslim and start acting based on that until I tell them she is not.” – Immigrant Muslim man “I don’t have Muslim friends. I’m originally from Egypt. There’s no Egyptian people around me, and I don’t get along with other nationalities. I don’t have friends at all.” – Muslim man over 60 “I have like a mixture of both Muslim and non-Muslim friends of all different races. I grew up around diversity, and I don’t have anything against non-Muslims. I have non-Muslim friends and coworkers and classmates and everything like that. I pretty much interact with all races and religions.” – Muslim woman under 30

“I actually do have a lot of Muslim friends, but have a lot of non-Muslim friends too. I would say it’s about two-thirds Muslim to one-third non-Muslim. A lot of my Muslim friends I made later in life. That’s because, when I was younger, it was harder to find Muslims I could be friends with. I found it difficult to socialize with Muslims who were socially very liberal. I found it very difficult because I was raised in a very conservative, religious household and that colored how I saw the world. … My dad served four years in the U.S. Air Force and that helped us better socialize with the public and accept our role here in America. And that eventually helped me make more Muslim friends. No matter where they stood on social issues, I could embrace them as friends because they were committed to being in this country as Muslims. … My non-Muslim friends saw me for myself and didn’t see or define me by my religious identity. I wear the hijab, but I have an outgoing personality. So they told me that while they may have judged me at first by my appearance, within five seconds they saw me for who I was.” – Muslim woman in her 40s “I have friends who are Muslim and friends who aren’t Muslim. I’m not sure if I have more Muslim friends or more non-Muslim friends because I don’t think about it. … Religion is just not a big issue for me. So, I don’t care if someone is Christian, Jewish or Muslim or whatever. For me it’s about what’s inside the person. I look for people who match my personality. If I like you, I don’t care about your religion. It’s you I’m interested in.” – Muslim man under 30

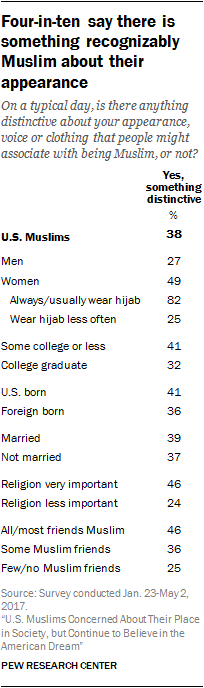

Some say they can be recognized as Muslim by appearance

About four-in-ten Muslim Americans say that on a typical day, there is something distinctive about their appearance, voice or clothing that other people might associate with being Muslim. Not only do the vast majority of women who report regularly wearing hijab say this (82%), but about a quarter of Muslim men (27%) and a similar share of Muslim women who wear hijab less often (25%) also say their everyday appearance effectively identifies them as Muslim.

Muslim women who say they are very religious are far more likely to say there is something distinctively Muslim about their appearance than are women who say religion is less important (63% vs. 16%); among men, however, there is no significant difference on this question by religious salience.

In addition, more Muslims in predominantly Muslim friendship circles say there is something distinctive about their appearance compared with those who have few or no Muslim friends.

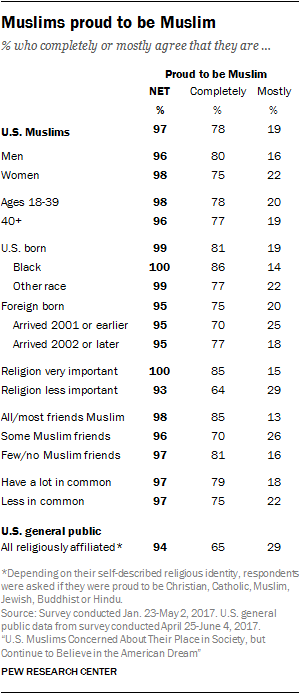

Nearly all U.S. Muslims are proud to be Muslim, most feel connected to the Muslim community

Pride in being Muslim is nearly universal among U.S. Muslims, 97% of whom “completely” or “mostly” agree that they are proud to be Muslim. By comparison, 94% of all religiously affiliated Americans say they are proud to be a member of their faith (e.g., proud to be Christian), although Muslim Americans are more likely than religiously affiliated Americans overall to completely agree that they are proud of their religious identity (78% vs. 65%).

U.S. Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives are especially likely to completely agree that they are proud to be Muslim (85%); among those who say religion is less important, about two-thirds (64%) completely agree that they are proud of their Muslim identity.

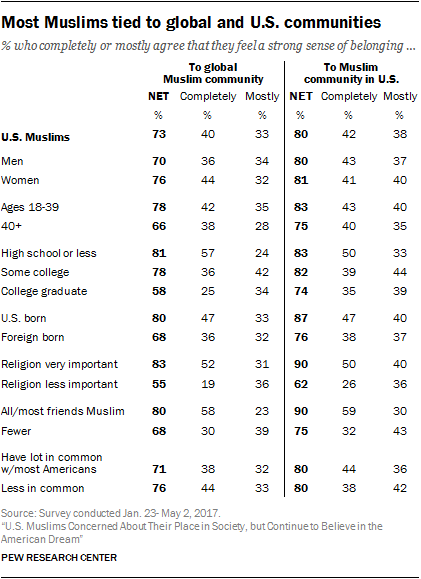

Most U.S. Muslims also feel a sense of belonging to Muslim communities both in the U.S. and around the world.

Nearly three-quarters of Muslim Americans completely (40%) or mostly (33%) agree that they feel a strong sense of belonging to the global Muslim community, or ummah . This view is more common among U.S.-born Muslims than among Muslim immigrants (80% vs. 68%).

Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives are far more likely than those who say religion is less important to say they feel a strong sense of belonging to the Muslim ummah (83% vs. 55%).

Muslims in the U.S. feel modestly more connected to the Muslim community in the U.S. than they do to the global Muslim community. Eight-in-ten completely (42%) or mostly (38%) agree that they feel a strong sense of belonging to the Muslim community in the United States. As with ties to the global Muslim ummah, U.S.-born Muslims, highly religious Muslims and those with many Muslim friends are especially likely to say they feel a connection to the Muslim community in the United States. How much U.S. Muslims feel they have in common with most Americans has little to do with how connected they feel to the Muslim community.

In their own words: What Muslims said about their sense of belonging to the global Muslim ummah and the U.S. Muslim community

Pew Research Center staff called back some of the Muslim American respondents in this survey to get additional thoughts on some of the topics covered. Here is a sampling of what they said about their sense of belonging to the global Muslim ummah and the U.S. Muslim community: “I guess I’m connected to the Muslim ummah, in terms of I belong to the same faith. So if you think about the billions of Muslims out there, I belong to that ummah – whatever that means. … If there is starvation in Somalia I’ll find a way to donate. But I don’t know if I’m that connected with the ummah. You get swallowed up in your life.” – Immigrant Muslim man

[to the Muslim community where I live]

“After 60 years of life, I sympathize with anybody in the world who has problems. It does not matter if they’re Christian, Jewish, Hindu or Muslim or whoever. When I see war and people who are dying or paying their life for something, whether Muslim or not, I feel connected to them.” – Muslim man over 60

“When I’ve traveled overseas … one of things I notice most is that I had more information and knowledge about my religion than my cousins and other family members who lived in a Muslim-majority country, Pakistan. I noticed that I felt more comfortable being Muslim than they did. … When you have freedom of religion and don’t allow it into the political life of a country – then you are free to explore religion, pursue and embrace it or leave it, as you see fit. That’s a beautiful thing to me.” – Muslim woman in her 40s

[The reason for this is a]

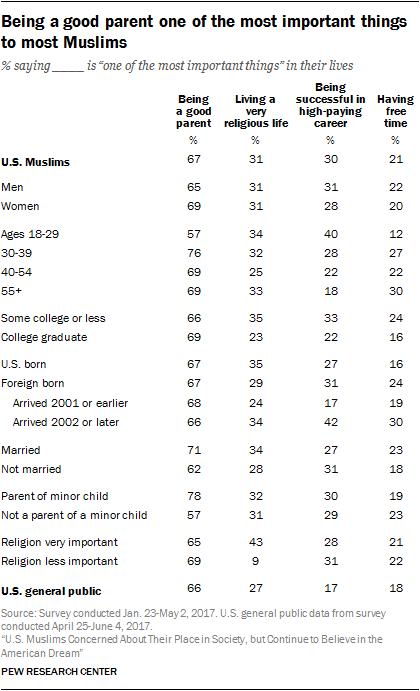

In their personal lives, Muslims prize being good parents – much like other Americans

The survey asked Muslim Americans about the importance of four specific life goals: being a good parent, living a very religious life, being successful in a high-paying career and having free time. Muslims largely mirror the U.S. general public in the sense that being a good parent is more important than any of the other goals asked about in the survey.

The vast majority of Muslim Americans say being a good parent is either “one of the most important things” in their lives (67%) or is “very important, but not one of the most important things” (25%). Very few say being a good parent is “somewhat important” (2%) or “not important” (5%). A similar pattern exists among the larger U.S. public, with fully two-thirds (66%) saying that being a good parent is one of the most important things in their lives and 23% saying it is very important but not one of the most important things.

An especially high share of Muslims with children under 18 currently living at home say being a good parent is one of the most important things (78%), but even among those without minor children at home, more than half (57%) say this as well.

While most Muslims (65%) say religion is very important in their lives, only about half as many (31%) say “living a very religious life” is “one of the most important things” in their life. Three-in-ten Muslims also say that being successful in a high-paying career is one of the most important goals in their life – higher than the comparable share of U.S. adults overall who say this (30% vs. 17%).

Career success is most important among young Muslims and recent immigrants. The importance of a high-paying career is also related to education and household income: About one-in-three respondents with a household income of less than $30,000 say being successful in a high-paying career is one of the most important things in life (35%), compared with just 18% of those with a household income over $100,000.

Having free time is the least important of the four life goals asked about in the survey. One-in-five Muslims say having free time to relax and do what they want is one of the most important things to them, similar to the share of Americans overall who say this.

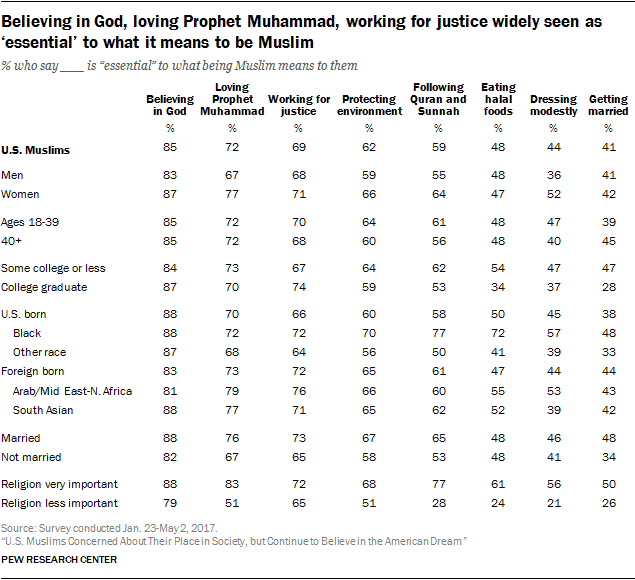

Essentials of being Muslim: Believing in God and loving the Prophet Muhammad, but also working for justice, protecting environment

The survey included a series of questions that asked Muslims whether several beliefs or behaviors are important or essential to what being Muslim means to them, personally. A large majority of Muslims (85%) say believing in God is essential to what being Muslim means to them, while 10% say believing in God is important but not essential to their Muslim identity. Very few (4%) say believing in God is not an important part of what being Muslim means to them.

A 2014 Pew Research Center survey found that U.S. Christians are similarly united in stating that belief in God is essential (86%) or important (10%) to what being Christian means to them.

After belief in God, Muslims place somewhat less emphasis on loving the Prophet Muhammad: Nearly three-quarters (72%) say loving Muhammad is essential to what it means to be Muslim, and another 20% say it is important but not essential.

About seven-in-ten Muslims (69%) say working for justice and equality in society is essential to what it means to be Muslim, and nearly as many (62%) say the same about protecting the environment. By comparison, a majority of U.S. Jews (60%) also say that working for justice and equality is essential to their Jewish identity. And far fewer U.S. Christians (22%) say protecting the environment is essential to what being Christian means to them.

About six-in-ten Muslim Americans (59%) say following the Quran and Sunnah is essential to what being Muslim means to them. Muslims are much more likely to say this than U.S. Jews are to say that observing Jewish law is essential to their Jewish identity (23%). Among Muslims, this view is concentrated among those who say religion is very important to them (77%), while far fewer Muslims who say religion is less important in their lives say following the Quran and Sunnah is essential to their Muslim identity (28%).

Muslims are similarly divided about the importance of eating halal food (see glossary for a definition of halal). Overall, about half of Muslims (48%) say eating halal food is essential to what being Muslim means to them. This view is expressed by roughly six-in-ten Muslims who say religion is very important in their everyday life (61%), but only about a quarter of Muslims who say religion is less important (24%).

Dressing modestly is seen as essential by 44% of Muslims. Here again, this view is most common among the most religious Muslims. The survey also finds that 52% of Muslim women say dressing modestly is essential to what being Muslim means to them, compared with just 36% of Muslim men who say this is essential to their Muslim identity.

Four-in-ten U.S. Muslims say getting married is essential to what being Muslim means to them. There is little difference between men and women on this issue, but married respondents are more likely than those who are not married to say marriage is essential to what being Muslim means to them. In addition, relatively few college-educated Muslims (28%) say getting married is essential.

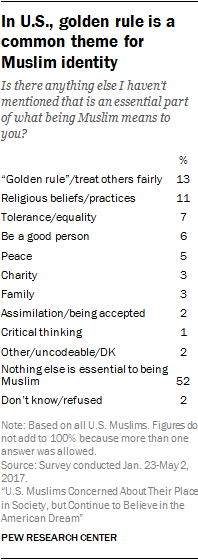

In addition to these eight items, respondents were asked if there was anything else that they personally see as essential to what it means to be Muslim. About one-in-ten mentioned the “golden rule” (13%) or specific ritual practices (11%), such as the daily salah (prayers), as essential aspects of being Muslim. And others mentioned being tolerant (7%), being a good person (6%) and either being peaceful or promoting peace (5%).

- This figure is the percentage of married “Jews by religion” (i.e., adults who identify their religion as Judaism) who say their spouse is also Jewish. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Beliefs & Practices

- Muslim Americans

- Religion & Politics

8 in 10 Americans Say Religion Is Losing Influence in Public Life

Faith on the hill, in their own words: how americans describe ‘christian nationalism’, pastors often discussed election, pandemic and racism in fall of 2020, most democrats and republicans know biden is catholic, but they differ sharply about how religious he is, most popular, report materials.

- Questionnaire

- Documentary: Being Muslim in the U.S.

- How Pew Research Center Conducted Its 2017 Survey of Muslim Americans

- 2017 Survey of U.S. Muslims

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

The Definition of a True Muslim

Raziullah Noman – Canada

With many Muslim scholars declaring other Muslims as non-Muslims in this day and age, it can be difficult to ascertain as to who is a true Muslim. Firstly, we should turn to the Holy Qur’an and see the Words of Allah. Allah the Almighty states about the Arab bedouins:

قَالَتِ الْأَعْرَابُ آمَنَّا قُلْ لَمْ تُؤْمِنُوا وَلَٰكِنْ قُولُوا أَسْلَمْنَا وَلَمَّا يَدْخُلِ الْإِيمَانُ فِي قُلُوبِكُمْ وَإِنْ تُطِيعُوا اللهَ وَرَسُولَهُ لَا يَلِتْكُمْ مِنْ أَعْمَالِكُمْ شَيْئًا إِنَّ اللَه غَفُورٌ رَحِيمٌ إِنَّمَا الْمُؤْمِنُونَ الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا بِاللهِ وَرَسُولِهِ ثُمَّ لَمْ يَرْتَابُوا وَجَاهَدُوا بِأَمْوَالِهِمْ وَأَنْفُسِهِمْ فِي سَبِيلِ اللهِ أُولَٰئِكَ هُمُ الصَّادِقُونَ

The Arabs of the desert say, ‘We believe.’ Say, “You have not believed yet; but rather say, ‘We have accepted Islam,’ for the true belief has not yet entered into your hearts.” But if you obey Allah and His Messenger, He will not detract anything from your deeds Surely, Allah is Most Forgiving, Merciful. The believers are only those who truly believe in Allah and His Messenger, and then doubt not, but strive with their possessions and their persons in the cause of Allah. It is they who are truthful. [i]

The Arabs of the desert would say they believe but, they were not yet true believers. For this reason, the Prophet Muhammad (sa) was told to say that you are Muslims but faith has not yet entered into your hearts. This shows that anyone who believes in Islam, is entitled to call themselves Muslims. The Qur’an does not allow anyone to declare another person a disbeliever if he recites the kalima (declaration of faith).

Then the question arises – what was the definition given by the Prophet Muhammad (sa)? When we turn to the ahadith (narrations of the Holy Prophet (sa)), we see that there are three main definitions of a Muslim.

The Prophet Muhammad (sa) stated:

اكْتُبُوا لِي مَنْ تَلَفَّظَ بِالإِسْلاَمِ مِنَ النَّاسِ

‘List the names of those people who have announced that they are Muslims’ [ii]

This was said by the Prophet Muhammad (sa) when the population of Muslims was needed for a census in Madinah. At that time this was the only criteria. Anyone who declared that they were Muslims, were counted as Muslims in the eyes of the founder of Islam.

The second definition mentioned some of the practices of Muslims. The Prophet Muhammad (sa) stated:

مَنْ صَلَّى صَلاَتَنَا، وَاسْتَقْبَلَ قِبْلَتَنَا، وَأَكَلَ ذَبِيحَتَنَا، فَذَلِكَ الْمُسْلِمُ الَّذِي لَهُ ذِمَّةُ اللَّهِ وَذِمَّةُ رَسُولِهِ، فَلاَ تُخْفِرُوا اللهَ فِي ذِمَّتِهِ

‘Whoever prays like us and faces our Qibla and eats our slaughtered animals is a Muslim and is under Allah’s and His Apostle’s protection. So do not betray Allah by betraying those who are in His protection.’ [iii]

In this hadith , the Prophet Muhammad (sa) has given a warning to the Muslims. He knew that in the future some extremist Muslims would persecute other Muslims over their differences. He warned such extremists that by persecuting such innocent Muslims, they would be betraying Allah.

In the third hadith , the Prophet Muhammad (sa) stated:

حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو بَكْرِ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ، حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو خَالِدٍ الأَحْمَرُ، ح وَحَدَّثَنَا أَبُو كُرَيْبٍ، وَإِسْحَاقُ بْنُ إِبْرَاهِيمَ، عَنْ أَبِي مُعَاوِيَةَ، كِلاَهُمَا عَنِ الأَعْمَشِ، عَنْ أَبِي ظِبْيَانَ، عَنْ أُسَامَةَ بْنِ زَيْدٍ، وَهَذَا، حَدِيثُ ابْنِ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ قَالَ بَعَثَنَا رَسُولُ اللهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم فِي سَرِيَّةٍ فَصَبَّحْنَا الْحُرَقَاتِ مِنْ جُهَيْنَةَ فَأَدْرَكْتُ رَجُلاً فَقَالَ لاَ إِلَهَ إِلاَّ اللهُ . فَطَعَنْتُهُ فَوَقَعَ فِي نَفْسِي مِنْ ذَلِكَ فَذَكَرْتُهُ لِلنَّبِيِّ صلى الله عليه وسلم فَقَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” أَقَالَ لاَ إِلَهَ إِلاَّ اللهُ وَقَتَلْتَهُ “ . قَالَ قُلْتُ يَا رَسُولَ اللهِ إِنَّمَا قَالَهَا خَوْفًا مِنَ السِّلاَحِ . قَالَ ” أَفَلاَ شَقَقْتَ عَنْ قَلْبِهِ حَتَّى تَعْلَمَ أَقَالَهَا أَمْ لاَ “ . فَمَازَالَ يُكَرِّرُهَا عَلَىَّ حَتَّى تَمَنَّيْتُ أَنِّي أَسْلَمْتُ يَوْمَئِذٍ . قَالَ فَقَالَ سَعْدٌ وَأَنَا وَاللهِ لاَ أَقْتُلُ مُسْلِمًا حَتَّى يَقْتُلَهُ ذُو الْبُطَيْنِ . يَعْنِي أُسَامَةَ قَالَ قَالَ رَجُلٌ أَلَمْ يَقُلِ اللهُ } وَقَاتِلُوهُمْ حَتَّى لاَ تَكُونَ فِتْنَةٌ وَيَكُونَ الدِّينُ كُلُّهُ لِلهِ{ فَقَالَ سَعْدٌ قَدْ قَاتَلْنَا حَتَّى لاَ تَكُونَ فِتْنَةٌ وَأَنْتَ وَأَصْحَابُكَ تُرِيدُونَ أَنْ تُقَاتِلُوا حَتَّى تَكُونَ فِتْنَةٌ

It is narrated on the authority of Usama b. Zaid that ‘the Messenger of Allah (sa) sent us on an expedition. We raided Huraqat of Juhaina in the morning. I caught hold of a man and he said:“There is no god but Allah”, I attacked him with a spear. It once occurred to me and I talked about it to the Apostle (sa). The Messenger of Allah (sa) said: ‘Did he profess “There is no god but Allah,” and even then you killed him?’ I said: ‘Messenger of Allah, he made a profession of it out of the fear of the weapon.’ He observed: ‘Did you tear his heart in order to find out whether it had professed or not?’ And he went on repeating it to me till I wished I had embraced Islam that day. Sa’d said: ‘By Allah, I would never kill any Muslim so long as a person with a heavy belly, i.e., Usama, would not kill.’ Upon this a person remarked: ‘Did Allah not say: And fight them until there is no more mischief and religion is wholly for Allah?’ Sa’d said: ‘We fought so that there should be no mischief, but you and your companions wish to fight so that there should be mischief.’ [iv]

The definitions given today by some Muslims are completely opposite to the words of the Prophet Muhammad (sa). Ahmadi Muslims believe all those who recite the kalima to be Muslims. Anything else spread in the media is either out of context or propaganda.

The Fifth Caliph and current worldwide head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, His Holiness, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba) stated:

‘The Ahmadiyya Community, according to the instructions of Allah and His Messenger (sa) believes everyone who recites the kalima is a Muslim. For someone to be a Muslim, it is enough for him to simply declare:

لَآ اِلٰهَ اِلَّااللهُ مُحَمَّدٌ رَّسُولُ الله

And this is exactly what is proven from the ahadith’ [v]

Speaking about the fact that some non-Ahmadi clerics have deemed Ahmadi Muslims to be non-Muslim, His Holiness (aba) said:

‘The Holy Prophet (sa) taught that no one has the right to call any person who utters the kalima to be a non-Muslim. The truth is that no human being or power has the right to deny what is in the heart of another person.’ [vi]

Despite having been labelled by most of the Muslim world as non-Muslims, Ahmadi Muslims do not seek out the approval or attestation of others; rather Ahmadi Muslims are content so long as they fulfill the criteria establish by God and His Messenger (sa), as His Holiness (aba) states:

‘As far as the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community is concerned, neither have we ever asked a foreign power to grant us the status of ‘Muslims’ before the law and the constitution, nor have we ever begged any Pakistani government for this. We do not require a certificate from any assembly or government in order to be called Muslims. We call ourselves Muslims. We call ourselves Muslims because we are Muslims. Allah the Exalted and His Messenger (sa) have declared us to be Muslims. We pronounce the kalima [declaration of faith]: [ there is none worthy of worship except Allah and Muhammad (sa) is His messenger ]. We believe in every pillar of Islam and article of faith. We have faith in the Holy Qur’an and believe the Holy Prophet (sa) to be Khatam-un-Nabiyeen [Seal of the Prophets] as Allah the Exalted has stated in the Holy Qur’an and as I have just recited. We have firm conviction that the Holy Prophet (sa) is Khatam-un-Nabiyeen .’ [vii]

[i] The Holy Qur’an Chapter 49 Verses 15-16

[ii] Sahih al-Bukhari, Hadith 3060

[iii] Sahih al Bukhari, Hadith 391

[iv] Sahih Muslim, Hadith 96 a

[v] Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba), Friday Sermon, 2 nd December 2011

[vi] Question and Answer Session with Indonesian Guests, 28 th September 2013 – https://www.alislam.org/press-release/true-khilafat-compatible-with-democracy-head-of-ahmadiyya-muslim-jamaat/

[vii] Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad (aba), Friday Sermon, October 13 th 2017

Related posts:

- Who are We to Judge?

- The Difference Between the Success of a Believer and a Non-Believer

- True Islam and Serving Humanity

- Caliph’s Germany Tour – Today’s Friday Sermon – The Companions

You may also like

A New Century of Islam Ahmadiyyat in Ghana – Becoming Beacons of Justice, Truth and Morality in the World

Friday Sermon Summary February 23 2024: ‘Testimony of the World to the Fulfilment of the Prophecy of the Promised Reformer’

Jewish and Muslim Co-Existence

Cancel reply.

Howdy very nice site!! Man .. Beautiful .. Superb .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds additionally?I’m happy to search out numerous useful info here within the post, we want work out more strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing.

Related Posts

Recent posts.

- Friday Sermon Summary 24th May 2024: ‘God Almighty’s Support for Khilafat’

- The 5 Apology Languages & Islamic Insights into Forgiveness – Part 4

- Are Muslims . . . ?

- Are Muslims Allowed To Gamble?

- Are Muslims Vegetarian?

What does it mean to be a Muslim woman? A new book is challenging the stereotypes

The clothing worn by some Muslim women has been a source of contention in many European countries. Image: REUTERS/Leonhard Foeger

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Heba Kanso

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Roles of Religion is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, roles of religion.

Fed up with Western stereotypes pegging Muslim women as "submissive" and judging them by their religious clothing, a feminist author collected essays from 17 Muslim women whose lives tell a different story, including her own.

In Mariam Khan's "It's Not About the Burqa", the authors include activists, journalists and researchers, mainly from Britain, who wrote personal stories about mental health, queer identity, divorce, feminism, and the hijab.

"Burqa is the most politicised word around Muslim women," Khan told the Thomson Reuters Foundation by phone from England on Wednesday.

"Burqa and hijab are the first things many people think of in the West when they think of Muslim women - that is not a problem, but there is so much more to a Muslim woman than the clothes she wears ... I want to diversify their stories."

The burqa is a head-to-toe cloak which conceals the face with a mesh or is worn in conjunction with the niqab - a face veil that leaves only the eyes exposed.

Last year, former British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson said the robe was oppressive, ridiculous and made women look like letter boxes and bank robbers, prompting an outcry from other politicians and British Muslim groups.

"Muslim female narratives are often co-opted by everyone who isn't a Muslim - rarely will you hear authentically, or in an unfiltered way from Muslim women, and it is really unfair," said Khan.

The wearing of full-face coverings, such as niqabs and burqas, is a polarising issue across Europe, with some arguing that they symbolise discrimination against women and should be outlawed. The clothing has been banned in France and Denmark.

Khan, 26, who wears a head scarf - or hijab - also has an essay in the book. In it, she wrote about how mainstream "white feminism" did not fit with the choices she made within her faith.

Have you read?

Why are people religious , these countries have the most women in parliament, religious violence is on the rise. what can faith-based communities do about it.

"For some feminists in the West they see (the hijab) as oppressive - but for people like me who wear it - I am not oppressed. I am empowered by it because I chose to wear it," she said.

Other authors in the book, which hits shelves on Thursday, include outspoken Egyptian-American activist Mona Eltahawy, who wrote about misogyny within the Muslim community, as well as her continued fight for women's rights.

Another contributor, Saima Mir, a former BBC journalist, wrote about being twice divorced, and the negative attitude toward divorce in Muslim Pakistani culture. Her essay questions why the culture judges divorce so harshly.

Khan hopes that after reading the book people will see that Muslim women are not under a "monolithic, single story narrative", and their voices and stories concerning their faith should be heard.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Civil Society .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How focused giving can unlock billions and catapult women’s wealth

Mark Muckerheide

May 21, 2024

Innovating for equity is a win-win for companies and communities

Cheryl L. Dorsey and Francois Bonnici

Lessons learned from over three decades fighting poverty

Vera R. Cordeiro

May 13, 2024

How to successfully orchestrate collective action

Khushboo Awasthi Kumari, Tasso Azevedo and Danya Pastuszek

May 6, 2024

How The Gambia offers a roadmap for enhancing diaspora engagement

Gibril Faal and Adrian Kitimbo

May 2, 2024

International Workers' Day: 3 ways trade unions are driving social progress

Giannis Moschos

May 1, 2024

- Religion & Spirituality

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Why I Am A Muslim: An American Odyssey Paperback – January 1, 2005

- Print length 172 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Thorsons Pub

- Publication date January 1, 2005

- Dimensions 5.25 x 0.5 x 8.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0007175345

- ISBN-13 978-0007175345

- See all details

Product details

- Publisher : Thorsons Pub (January 1, 2005)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 172 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0007175345

- ISBN-13 : 978-0007175345

- Item Weight : 7.2 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.25 x 0.5 x 8.25 inches

About the author

Asma gull hasan.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

College Essay: I Am Muslim, I Am Black

I am Yasmin Mohamed Sheikh Abdurahman Noor Sheikh Mohamed Hussein. I am Somali. I am American. I am Muslim. I am a Black woman. I used to believe that being all of these things at once was nearly impossible.

Walking into my first class at my first public school after moving from a charter school was quite literally the most nerve-wracking thing I ever did because of the dreaded roll call. In my eighth- grade English class after the bell rang on the first day, a teacher read names off of the roster. When it came to me, I wished I could melt into my chair. My teacher paused at my name, looked up and found me, the dark-skinned hijabi, then asked students to raise their hands if their last name started with “Abd.” When I hesitantly raised my hand, wishing that this moment could end, my teacher asked, “What a unique name. Where is it from?”

To many of the white 13-year-olds in my class, the Black students who they were acquainted with were the “cool Black kids” who wore expensive sneakers, went to church on Wednesdays and got their hair done every weekend. I didn’t want to stand out. I shoved myself into a box where I only allowed my Blackness to seep through. My Muslim and Somali identity was never allowed to gasp for air. But I still wasn’t protected from the woes of an “African village girl” that somehow always found a way into a conversation.

By the end of eighth grade, I had somewhat completed my social transition from African to African-American. As long as I didn’t do anything too wild, like dress in the traditional baati or bring Somali food for lunch, I wasn’t African; I was just another “normal Black muslim girl.” At that time, that was all I thought I could be.

High school brought on a massive shift in my perspective, not only on my culture but also my religion. Nearly every Black kid at the school was first-generation American, with mostly Somali, Nigerian, Kenyan and Ethopian roots; many of them were Muslim. For the first time in a long time, I wasn’t the one who stuck out like a sore thumb.

Not only that, but everyone was so proud of their home countries. They brought their native foods to lunch and shared it with one another. We hyped up our friends who would wear their native clothing;we didn’t need to be “the cool Black kids” anymore. I tried to connect to my culture and language more, but it never crossed my mind that I would now envy the people who spoke their language fluently and are able to converse with family overseas. I found myself slowly reaching out to family and friends to help me learn my language.

I was finally reacquainting myself with my Somali side and falling in love with it as I did. I rediscovered the rich qualities of Somali culture, from the brightness of its clothing to the poetry that diversified Somalia and nuances of its sweet music that made everyday life beautiful.

Up until now, I believed that it was impossible to be so many things at once. I am Somali. I am American. I am a Black woman. I am Yasmin Mohamed Sheikh Abdurahman Noor Mohamed Sheikh Hussein and I am proud.

© 2024 ThreeSixty Journalism • Login

ThreeSixty Journalism,

a nonprofit program of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of St. Thomas, uses the principles of strong writing and reporting to help diverse Minnesota youth tell the stories of their lives and communities.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Strangers in Their Own Land: Being Muslim in Modi’s India

Families grapple with anguish and isolation as they try to raise their children in a country that increasingly questions their very identity.

By Mujib Mashal and Hari Kumar

Reporting from Noida and Chennai, India

It is a lonely feeling to know that your country’s leaders do not want you. To be vilified because you are a Muslim in what is now a largely Hindu-first India.

It colors everything. Friends, dear for decades, change. Neighbors hold back from neighborly gestures — no longer joining in celebrations, or knocking to inquire in moments of pain.

“It is a lifeless life,” said Ziya Us Salam, a writer who lives on the outskirts of Delhi with his wife, Uzma Ausaf, and their four daughters.

When he was a film critic for one of India’s main newspapers , Mr. Salam, 53, filled his time with cinema, art, music. Workdays ended with riding on the back of an older friend’s motorcycle to a favorite food stall for long chats. His wife, a fellow journalist, wrote about life, food and fashion.

Now, Mr. Salam’s routine is reduced to office and home, his thoughts occupied by heavier concerns. The constant ethnic profiling because he is “visibly Muslim” — by the bank teller, by the parking lot attendant, by fellow passengers on the train — is wearying, he said. Family conversations are darker, with both parents focused on raising their daughters in a country that increasingly questions or even tries to erase the markers of Muslims’ identity — how they dress, what they eat, even their Indianness altogether.

One of the daughters, an impressive student-athlete, struggled so much that she needed counseling and missed months of school. The family often debates whether to stay in their mixed Hindu-Muslim neighborhood in Noida, just outside Delhi. Mariam, their oldest daughter, who is a graduate student, leans toward compromise, anything to make life bearable. She wants to move.

Anywhere but a Muslim area might be difficult. Real estate agents often ask outright if families are Muslim; landlords are reluctant to rent to them.

“I have started taking it in stride,” Mariam said.

“I refuse to,” Mr. Salam shot back. He is old enough to remember when coexistence was largely the norm in an enormously diverse India, and he does not want to add to the country’s increasing segregation.

But he is also pragmatic. He wishes Mariam would move abroad, at least while the country is like this.

Mr. Salam clings to the hope that India is in a passing phase.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, however, is playing a long game.

His rise to national power in 2014, on a promise of rapid development, swept a decades-old Hindu nationalist movement from the margins of Indian politics firmly to the center. He has since chipped away at the secular framework and robust democracy that had long held India together despite its sometimes explosive religious and caste divisions.

Right-wing organizations began using the enormous power around Mr. Modi as a shield to try to reshape Indian society. Their members provoked sectarian clashes as the government looked away, with officials showing up later to raze Muslim homes and round up Muslim men. Emboldened vigilante groups lynched Muslims they accused of smuggling beef (cows are sacred to many Hindus). Top leaders in Mr. Modi’s party openly celebrated Hindus who committed crimes against Muslims.

On large sections of broadcast media, but particularly on social media, bigotry coursed unchecked. WhatsApp groups spread conspiracy theories about Muslim men luring Hindu women for religious conversion, or even about Muslims spitting in restaurant food. While Mr. Modi and his party officials reject claims of discrimination by pointing to welfare programs that cover Indians equally, Mr. Modi himself is now repeating anti-Muslim tropes in the election that ends early next month. He has targeted India’s 200 million Muslims more directly than ever, calling them “infiltrators” and insinuating that they have too many children.

This creeping Islamophobia is now the dominant theme of Mr. Salam’s writings. Cinema and music, life’s pleasures, feel smaller now. In one book, he chronicled the lynchings of Muslim men. In a recent follow-up, he described how India’s Muslims feel “orphaned” in their homeland.

“If I don’t pick up issues of import, and limit my energies to cinema and literature, then I won’t be able to look at myself in the mirror,” he said. “What would I tell my kids tomorrow — when my grandchildren ask me what were you doing when there was an existential crisis?”

As a child, Mr. Salam lived on a mixed street of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims in Delhi. When the afternoon sun would grow hot, the children would move their games under the trees in the yard of a Hindu temple. The priest would come with water for all.

“I was like any other kid for him,” Mr. Salam recalled.

Those memories are one reason Mr. Salam maintains a stubborn optimism that India can restore its secular fabric. Another is that Mr. Modi’s Hindu nationalism, while sweeping large parts of the country, has been resisted by several states in the country’s more prosperous south.

Family conversations among Muslims there are very different: about college degrees, job promotions, life plans — the usual aspirations.

In the state of Tamil Nadu, often-bickering political parties are united in protecting secularism and in focusing on economic well-being. Its chief minister, M.K. Stalin, is a declared atheist.

Jan Mohammed, who lives with his family of five in Chennai, the state capital, said neighbors joined in each other’s religious celebrations. In rural areas, there is a tradition: When one community finishes building a place of worship, villagers of other faiths arrive with gifts of fruits, vegetables and flowers and stay for a meal.

“More than accommodation, there is understanding,” Mr. Mohammed said.

His family is full of overachievers — the norm in their educated state. Mr. Mohammed, with a master’s degree, is in the construction business. His wife, Rukhsana, who has an economics degree, started an online clothing business after the children grew up. One daughter, Maimoona Bushra, has two master’s degrees and now teaches at a local college as she prepares for her wedding. The youngest, Hafsa Lubna, has a master’s in commerce and within two years went from an intern at a local company to a manager of 20.

Two of the daughters had planned to continue on to Ph.D’s. The only worry was that potential grooms would be intimidated.

“The proposals go down,” Ms. Rukhsana joked.

A thousand miles north, in Delhi, Mr. Salam’s family lives in what feels like another country. A place where prejudice has become so routine that even a friendship of 26 years can be sundered as a result.

Mr. Salam had nicknamed a former editor “human mountain” for his large stature. When they rode on the editor’s motorcycle after work in the Delhi winter, he shielded Mr. Salam from the wind.

They were together often; when his friend got his driver’s license, Mr. Salam was there with him.

“I would go to my prayer every day, and he would go to the temple every day,” Mr. Salam said. “And I used to respect him for that.”

A few years ago, things began to change. The WhatsApp messages came first.

The editor started forwarding to Mr. Salam some staples of anti-Muslim misinformation: for example, that Muslims will rule India in 20 years because their women give birth every year and their men are allowed four wives.

“Initially, I said, ‘Why do you want to get into all this?’ I thought he was just an old man who was getting all these and forwarding,” Mr. Salam said. “I give him the benefit of doubt.”

The breaking point came two years ago, when Yogi Adityanath, a Modi protégé, was re-elected as the leader of Uttar Pradesh, the populous state adjoining Delhi where the Salam family lives. Mr. Adityanath, more overtly belligerent than Mr. Modi toward Muslims, governs in the saffron robe of a Hindu monk, frequently greeting large crowds of Hindu pilgrims with flowers, while cracking down on public displays of Muslim faith.

On the day of the vote counting, the friend kept calling Mr. Salam, rejoicing at Mr. Adityanath’s lead. Just days earlier, the friend had been complaining about rising unemployment and his son’s struggle to find a job during Mr. Adityanath’s first term.

“I said, ‘You have been so happy since morning, what do you gain?’” he recalled asking the friend.

“Yogi ended namaz,” the friend responded, referring to Muslim prayer on Fridays that often spills into the streets.

“That was the day I said goodbye,” Mr. Salam said, “and he hasn’t come back into my life after that.”

Mujib Mashal is the South Asia bureau chief for The Times, helping to lead coverage of India and the diverse region around it, including Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan. More about Mujib Mashal

Hari Kumar covers India, based out of New Delhi. He has been a journalist for more than two decades. More about Hari Kumar

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A Persian, a Turk, an Arab and a Greek are traveling to a distant land when they begin arguing over how to spend the single coin they share in common. The Persian wants to spend the coin on angur ...

As a writer and scholar of religions, I am often asked how, knowing all that I know about the religions of the world, I can still call myself a believer, let alone a Muslim. It's a reasonable question. Considering the role that religion so often plays in fueling conflicts abroad and inspiring bigotry at home,…

I am very thankful to Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis that she has done a wonderful job during searching of the art of islam that I am a muslim …. and I don't have any problem with this article or essay but it minus the manners of our prophet how it look's like and the originally of islam does it play any role of the terrorism in the world ...

I am a muslim and being a muslim the the formost important thing for me is to get and give the right knowledge. I would like to share my thoughts with all the people that allah has created all the humans and given them so much intelligence that no other creations have got, making them superior on them.Our great allah is very justiful. ...

Farah Al Qasimi for The New York Times. Although Muslim Americans are often perceived as foreigners or latecomers, history tells us otherwise. Muslims have lived in America since before there was ...

Essay Writing Service. Islam teaches me to respect elders and love children and promote brotherhood. Islam promotes justice and equality. You are treated equally either you are Arab, Non-Arab, White or Black you are treated equally in Islam. In Islam Fasting in the month of Ramadan is to makes us realize how poor people sometimes live without ...

Extract. To be a Muslim today—or any day—is to live in accordance with the will and pleasure of Allah. Muslims often say, with joy and pride, that it is easy to be a Muslim since Islam is 'the straight path' leading to paradise. What this means, in other words, is that the principles of Islam are simple and straightforward, free of ...

Identity, assimilation and community. Muslim Americans overwhelmingly embrace both the "Muslim" and "American" parts of their identity. For instance, the vast majority of U.S. Muslims say they are proud to be American (92%), while nearly all say they are proud to be Muslim (97%). Indeed, about nine-in-ten (89%) say they are proud to be ...

It is a failure to give moral philosophy the task of mixing it up with (in this. case) history in order to say something about the specific functional. sources of given fundamental commitments (such as to Islam) and then, relatedly, a failure to consider a more bottom-up approach to the study of. moral principles.

Why I Am Not a Christian is an essay by the British philosopher Bertrand Russell. Originally a talk given on 6 March 1927 at Battersea Town Hall, ... Why I Am Not a Muslim, a 1995 book by Ibn Warraq, is also critical of the religion in which the author was brought up — in this case, Islam.

The Arabs of the desert say, 'We believe.'. Say, "You have not believed yet; but rather say, 'We have accepted Islam,' for the true belief has not yet entered into your hearts.". But if you obey Allah and His Messenger, He will not detract anything from your deeds Surely, Allah is Most Forgiving, Merciful.The believers are only ...

The article ran under the title "The Extinction of the Grayzone.". The gray zone is the space inhabited by any Muslim who has not joined the ranks of either ISIS or the crusaders. Throughout ...

The press has been filled with information and misinformation about the true nature of Islam. Hasan represents what is left out of the daily newspapers and explains why being a Muslim is not merely a matter of birth, but it is a matter of choice. In the wake of 9-11, the activities of Osama Bin Laden and Hamas, and the most recent Gulf War, the western press has been filled with information ...

But these assumptions aren't totally out of the blue—the Muslim's religion, Islam, teaches a low tolerance for other religions and the Islamic government has no separation of church and state, so it's only normal to assume that their government shall have a low tolerance as well—some however, immediately translate this into terrorism.

Wearing the hijab is a reminder of my beliefs. I wear it through the heat of the summer, through the cold of winter and despite the curious stares. It takes willpower. Many would give up, but I'm not the average person. I wear my hijab because it's part of who I am. I am very dedicated and I don't give up easily when things get tough.

"Muslim female narratives are often co-opted by everyone who isn't a Muslim - rarely will you hear authentically, or in an unfiltered way from Muslim women, and it is really unfair," said Khan. The wearing of full-face coverings, such as niqabs and burqas, is a polarising issue across Europe, with some arguing that they symbolise discrimination ...

This just isn't the case - Islam has its different denominations, just as Christianity does, and there are lots of possible ways of interpreting an old classical Arabic text. "Why I Am a Muslim" is one woman's personal exploration of those possibilities, not a definitive textbook on all things Islamic. It should be accepted as such.

933 reviews 110 followers. October 31, 2011. Simply but engagingly written, Why I Am a Muslim is more of a personal narrative than an in-depth analysis of Islam. Ms. Hasan covers the basic tenets of Islam as well as the interaction between the religion itself and various cultural traditions (such as female genital mutilation, polygamy, even ...

July 2021 Yasmin Abdurahman College Essay, Summer Camp, ThreeSixty Magazine, Voices. I am Yasmin Mohamed Sheikh Abdurahman Noor Sheikh Mohamed Hussein. I am Somali. I am American. I am Muslim. I am a Black woman. I used to believe that being all of these things at once was nearly impossible. Walking into my first class at my first public school ...

Open Document. I am Muslim. Muslim parents are authoritative. My parents have rules and pretty good reasoning behind them. They are strictly against parties and anything that could cause trouble in my near future. But I really wanted to experience a party. So, one day I decided to rebel and go to a friend's party one night, without them knowing.

Why I Am Not a Muslim. Why I Am Not a Muslim, a book written by Ibn Warraq, is a critique of Islam and the Qur'an. It was first published by Prometheus Books in the United States in 1995. The title of the book is a homage to Bertrand Russell 's essay, Why I Am Not a Christian, in which Russell criticizes the religion in which he was raised.

These people are genuinely scared that the 1.7 billion Muslim people worldwide exist purely to kill Americans because they "disagree with American values.". Of course, that isn't true, but ...

He has targeted India's 200 million Muslims more directly than ever, calling them "infiltrators" and insinuating that they have too many children. Mr. Salam, and his wife, Uzma Ausaf, at ...

An ultraconservative president, 63-year-old Raisi was killed Sunday, along with Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian and other high-ranking officials, in a helicopter crash in Iran's remote ...

I am Muslim by birth and proud to be a Muslim. I know Islam is a true religion and I am on a right track. There are other religions too Why I was not attracted towards them? The main reason is my stro ... Essay Services; Essay Writing Service; Assignment Writing Service; Coursework Writing Service; Essay Plan Writing Service;

Abstract. This essay is an exposition of the philosophy of populism, a philosophy by and large inspired by Michel Foucault to herald the New Discourse called 'post-Marxism' a term made famous by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe which would lay the foundations for not so much the secular New Social Movements comprising multiple issues like gay rights and environment, but ironically would be ...