An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

EVOLUTION OF HUMAN EMOTION

Joseph e. ledoux.

New York University, 4 Washington Place, New York, NY 10003, 212-998-3930. Nathan Kline Institute, 140 Old Orangeburg Road, Orangeburg, NY 10962

Basic tendencies to detect and respond to significant events are present in the simplest single cell organisms, and persist throughout all invertebrates and vertebrates. Within vertebrates, the overall brain plan is highly conserved, though differences in size and complexity also exist. The forebrain differs the most between mammals and other vertebrates. The classic notion that the evolution of mammals led to radical changes such that new forebrain structures (limbic system and neocortex) were added has not held up, nor has the idea that so-called limbic areas are primarily involved in emotion. Modern efforts have focused on specific emotion systems, like the fear or defense system, rather than on the search for a general purpose emotion systems. Such studies have found that fear circuits are conserved in mammals, including humans. Animal work has been especially successful in determining how the brain detects and responds to danger. Caution should be exercised when attempting to discuss other aspects of emotion, namely subjective feelings, in animals since there are no scientific ways of verifying and measuring such states except in humans.

Introduction

The topic of emotion and evolution typically brings to mind Darwin’s classic treatise, Emotions in Man and Animals ( Darwin, 1872 ). In this book Darwin sought to extend his theory of natural selection beyond the evolution of physical structures and into the domain of mind and behavior by exploring how emotions too might have evolved. Particularly important to his argument was the fact that certain emotions are expressed similarly in people around the world, including in isolated areas where there had been little contact with the outside world and thus little opportunity for emotional expressions to have been learned and culturally transmitted. This suggested to him that there must be a strong heritable component to emotions in people. Also important was his observation that certain emotions are expressed similarly across species, especially closely related species, further suggesting that these emotions are phylogenetically conserved.

With the rise of experimental brain research in the late 19 th century, emotion was one of the key topics that early neuroscientists sought to relate to the brain (see LeDoux, 1987 ). The assumption was that emotion circuits are conserved across mammalian species, and that it should be possible to understand human emotions by exploring emotional mechanisms in the non-human mammalian brain.

In this chapter, I will first briefly survey the history of ideas about the emotional brain, and especially ideas that have attempted to explain the emotional brain in terms of evolutionary principles. This will lead to a discussion of fear, since this is the emotion that has been studied most thoroughly in terms of brain mechanisms. The chapter will conclude with a reconsideration of what the term emotion refers to, and specifically which aspects of emotion can be studied in animals and which must be studied in humans.

A Brief History of the Emotional Brain: The Rise and Fall of the Limbic System Theory

All organisms, even single cell organisms, must have the capacity to detect and respond to significant stimuli in order to survive. Bacteria, for example, approach nutrients and avoid harmful chemicals ( Macnab and Koshland, 1972 ). With the evolution of multicellular, metazoan organisms with specialized systems, particularly a nervous system, the ability to detect and respond to significant events increases in sophistication ( Shepherd, 1983 ).

Invertebrates, the oldest and largest group of multicellular organisms, exhibit a wide variety of types of nervous systems. However, all vertebrates share a common basic brain plan consisting of three broad zones (hindbrain, midbrain, and forebrain) with conserved basic circuits ( Nauta and Karten, 1970 ; Swanson, 2002 ; Bulter and Hodos, 2005 ; Striedter, 2005). In spite of this overall similarity, differences in size and complexity exist. For example, the forebrain differs the most between mammals and reptiles. On the basis of such differences, the classic view of forebrain evolution emerged in the first half of the 20 th century (e.g. Smith, 1924 ; Herrick, 1933 ; Arien Kappers et al, 1936 ; Papez, 1937 ; MacLean, 1949 , 1952 ). According to this view, with the emergence of mammals, the forebrain plan underwent radical changes in which new structures, especially cortical structures, were added. These were layered over and covered the reptilian forebrain, which mainly consisted of the basal ganglia. First came “primitive” cortical regions in early mammals. In these organisms the basic survival functions related to feeding, defense and procreation were taken care of by fairly undifferentiated (weakly laminated) cortical regions (primitive cortex, including the hippocampus and cingulate cortex) and related subcortical areas (such as the amygdala) that were closely tied to the olfactory system. Later mammals added highly novel, laminated cortical regions (neocortex) that made possible enhanced non-olfactory sensory processing and cognitive functions (including learning and memory, reasoning, and planning capacities, and, in humans, language).

The basic principle that equated cognition with evolutionarily new cortex (neocortex) and emotion with older cortex and related subcortical forebrain regions culminated in Paul MacLean’s limbic system theory of emotion (1949 , 1952 , 1970 ). The term limbic was first used by the French anatomist Paul Broca as a structural designation for a rim of cortex in the medial wall of the hemisphere. Broca called this rim the limbic lobe ( le grande lobe limbique ) (limbic is from the Latin word for rim, limbus ). MacLean built on the classic findings of comparative anatomists such as Herrick and Papez, and experimental findings from Walter Cannon, Phillip Bard and Henrich Kluver and Paul Bucy ( Cannon, 1929 ; Bard, 1928 ; Kluver and Bucy, 1937 ) to transform the limbic lobe into an emotion system, the limbic system. The limbic system was defined anatomically as the primitive medial cortical areas and interconnected subcortical nuclei (including the amygdala and septum).

MacLean called the limbic system the paleomammalian brain (since it was said to have emerged with the evolution of early mammals), and contrasted it with the reptilian brain (basal ganglia and brainstem). In more recent mammals the neocortex, also called the neomammalian brain, was said by MacLean to increases in size and complexity at the expense of the limbic system. The decrease of the limbic system reduced the dependence of humans on base emotions, and the increase in the neocortex allowed humans greater control over remaining emotional circuits as well as greater cognitive capacities.

The limbic system concept stimulated much research in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. However, it has been criticized on a number of grounds, and has been rejected by many scientists ( Swanson, 1983 ; LeDoux, 1987 , 1991 , 1996 ; Kotter and Meyer, 1992 ; Butler and Hodos, 2005 ). Because the limbic system concept continues to be referred to in some scientific circles (e.g. Panksepp, 1998 , 2005 ) and persists in many lay accounts of the brain, it is worth considering why it is not acceptable.

First, the theory presumes that the neocortex and limbic system are unique mammalian specializations. Neither of these ideas is accepted by contemporary comparative neuroanatomists ( Nauta and Karten, 1970 ; Northcutt and Kaas, 1995 ; Butler and Hodos, 2005 ; Striedter, 2005). Birds and reptiles, for example, have been shown to have structures that correspond with both mammalian neocortex and with MacLean’s cortical and subcortical limbic areas (hippocampus, amygdala). Second, MacLean argued the architecture of limbic areas is ill-suited for cognitive processes. However, the hippocampus, viewed by MacLean as the centerpiece of the limbic system and a central structure for emotional functions, is recognized as one of the key areas related to higher cognitive functions, such as declarative or explicit memory ( Squire, 1987 ; Eichenbaum, 2002 ) and spatial cognition ( O’Keefe and Nadel, 1978 ). Third, efforts to define the system have failed. Connectivity with old cortex is a flawed criterion if old cortex is itself an unjustified notion. Connectivity with the hypothalamus once seemed plausible, since that was a way of distinguishing relevant and irrelevant cortical areas ( Issacson, 1982 ). However, as anatomical techniques improved, areas from the neocortex were also found to be connected with the hypothalamus, as were areas of the spinal cord, potentially extending the limbic system across the entire brain. Finally, and perhaps most important, there is no evidence that the limbic system, however defined, functions as an integrated system in the mediation of emotion. While specific areas of the limbic system contribute to some emotional functions, these areas do not do so because they belong to a limbic system that evolved to perform emotional functions. Indeed, relatively few limbic areas have been shown to contribute to emotional functions. As noted above, the hippocampus, the centerpiece of the limbic system theory of emotion, has been strongly implicated in cognitive functions but the evidence for a role in emotion is far less impressive.

The limbic system theory attempted to explain all emotions within a single anatomical concept. Contemporary researchers are more inclined to focus on tasks designed to study the brain systems of specific emotions. As we will see, this has been a more profitable empirical approach.

Contributions of the Amygdala to Avoidance Conditioning: An Early Approach to Linking Emotional Behavior to the Limbic System

Why, then, has the limbic system concept persisted for so long given that it proved questionable on evolutionary, structural, and functional grounds? The key reason can be summarized in the term “guilt by association.” One limbic area, the amygdala, has consistently been implicated in emotional behavior. Because the amygdala was part of the limbic system concept, its involvement vindicated the whole concept. This does not mean that the amygdala is the only structure involved in emotion, but instead that the amygdala is one area that has been extensively implicated in emotion, in part because of the behavioral tasks that have most often been used to study emotion.

The amygdala was first implicated in emotion through studies of the Kluver-Bucy Syndrome, a set of unusual behaviors observed in monkeys after removal of large areas of the temporal lobe ( Kluver and Bucy, 1937 ). Monkeys with such lesions attempted to eat inappropriate items and copulate with inappropriate partners, and lost their fear of snakes and humans. It was concluded that the animals had psychic blindness, an inability to appreciate the significance or value of visual stimuli. Weiskrantz (1956) attempted to localize the effects within the temporal lobe using a behavioral task where behavior was guided by stimulus value. Specifically, he used an avoidance conditioning paradigm where monkeys learned to use a cue to signal when to perform a behavioral response in order to avoid receiving a painful shock. Such a paradigm was viewed as especially useful in assessing the role of the amygdala in processing threats that lead to fear. Damage targeted to the amygdala disrupted performance, leading Weiskrantz to conclude that the amygdala was responsible for the inability of animals with temporal lobe damage to use stimulus value to guide behavior, and thus that an important function of the amygdala was to ascertain stimulus value. Specifically, Weiskrantz proposed that the amygdala processes the rewarding and punishing consequences of events. However, the data were essentially about aversive or punishing events since avoidance conditioning is a fear-based paradigm.

Subsequently, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, avoidance conditioning paradigms were used to study the contribution of the amygdala to emotion, an especially to fear. The bulk of the evidence was consistent, in general, with the idea that the amygdala is a key structure in avoidance conditioning, and by implication, in processing the value of emotional stimuli. Such findings were treated as evidence in support of the limbic system theory of emotion since the amygdala was part of the limbic system.

By the mid 1980s, thirty years of research on the brain mechanisms of avoidance had been conducted. While it seemed clear that the amygdala was somehow involved, there was considerable confusion as exactly what its role might be ( Sarter and Markowitsch, 1985 ). There are several explanations likely for this unsettled state of affairs. First, there was little appreciation of the anatomical complexity of the amygdala, a brain region with a dozen or so nuclei, each with subnuclei ( Amaral et al, 1992 ; Pitkanen et al, 1997 ; LeDoux, 2007 ). Failure to recognize this anatomical complexity may have led to confusion. Indeed, more recent work has shown that different nuclei and subnuclei have different functions ( Repa et al, 2001 ; LeDoux, 2007 ). Second, the behavioral complexity of avoidance conditioning itself was not fully appreciated. Avoidance tasks can be constructed in various ways (active, passive, signaled, unsignaled), and each involves the learning of a Pavlovian association and an instrumental association ( Cain and LeDoux, 2007 ; Cain et al., 2010 ; LeDoux et al., 2009 ; Choi et al, 2010 ; Amorapanth et al, 2000 ; Lazaro-Munoz et al., 2010 ). In retrospect, failure to separate these components also probably played a role in adding confusion to efforts to understand the brain mechanisms of avoidance.

Contribution of the Amygdala to Fear: Studies of Aversive Pavlovian Conditioning

During the 1960s, researchers began using Pavlovian conditioning to pursue the cellular and molecular mechanisms of learning in invertebrates (e.g. Kandel and Spencer, 1968 ; Kandel et al., 1986 ). The success of this approach, together with the fact that avoidance conditioning was stuck in a rut, led mammalian researchers to turn to Pavlovian conditioning as well ( Thompson, 1986 ; Kapp et al, 1979 ; LeDoux et al, 1984 ; Tischler and Davis, 1983 ).

As mentioned already, Pavlovian conditioning is the initial phase of avoidance conditioning. After the subjects rapidly undergo Pavlovian conditioning, they then slowly learn to perform avoidance responses using the CS as a warning signal. Indeed, the emotional learning that occurs in avoidance conditioning occurs during the Pavlovian phase. Pavlovian conditioning is thus a more direct means of studying emotional processing. Perhaps Pavlovian conditioning would be easier to understand.

In Pavlovian fear conditioning, the subject receives a neutral conditioned stimulus (CS), usually a tone, followed by an aversive unconditioned stimulus (US), typically footshock. After one or at most a few pairings, the CS comes to elicit innate emotional responses that naturally occur in the presence of threatening stimuli, such as predators. For example, after conditioning a CS elicits defensive freezing behavior and associated autonomic and endocrine responses that support the behavior ( Blanchard and Blanchard, 1969 ; Bolles and Fanselow, 1980 ; LeDoux et al, 1984 ). The subject does not have to learn to perform these responses. The responses are innate. What is learned is an association that allows a novel stimulus, a warning of danger, to elicit the defensive responses in anticipation of the actual danger.

With the simpler approach provided by fear conditioning, as opposed to avoidance, much progress was made in mapping the circuitry, including the regions in the brain where the CS and US converge to form the associations and the regions involved in the control of emotional responses by the CS in animals (see LeDoux, 2000 ; Maren, 2001 , 2005 ; Rodrigues et al, 2004 ; Johansen et al, in review ; Davis, 1992 ; Davis et al., 1997 ; Fanselow and Poulos, 2005 ; Pape and Pare, 2010 ) and humans ( Phelps and LeDoux, 2005 ; Phelps, 2006 ; Sehlmeyer et al., 2009 ; Kim et al., 2011 ; Whalen and Phelps, 2009 ). In brief, CS and US convergence occur in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala (LA), and specifically in the dorsal subregion of the LA. This convergence leads to synaptic plasticity and the formation of a CS-US association. Damage to LA, inactivation of LA, or manipulation of a variety of molecular pathways in LA prevents fear conditioning. A second important region is central nucleus of the amygdala (CE). Manipulations of the region also disrupts conditioning. LA and CE are connected directly and by way of various intra-amygdala pathways. Once the CS-US association is formed, later exposure to the CS results in the retrieval of the learned association formed by CS-US convergence during conditioning. Information then flows from LA to CE, which then connects to hypothalamic and brainstem areas that control behavioral, autonomic, and hormonal responses that help the organism cope with the threat. Plasticity also occurs in CE, and in CS processing regions and motor control regions. This simplified description omits many details.

Much has been learned about the molecular mechanisms in LA that make fear conditioning possible ( Blair et al, 2001 ; Schafe et al, 2001 ; Rodrigues et al, 2004 ; Fanselow and Poulos, 2005 ; Maren, 2001 , 2005 ; Pape and Pare, 2010 ; Sah et al, 2008 ; Johansen et al, in review ). In brief, the CS input synapses undergo plasticity when the LA neurons they connect with are depolarized by the shock US. As a result, the ability of the CS to activate the LA cell is potentiated. Plasticity is triggered when the depolarizing US allows calcium to flow into the cell via NMDA receptors and voltage sensitive calcium channels. The elevated calcium activate a number of protein kinases that ultimately lead to phosphoylation of transcription factors such as CREB that lead to gene expression and protein synthesis. The newly synthesized proteins then stabilize the synaptic potentiation, allowing the CS to strongly activate the LA cell for over long periods of time. It is particularly interesting that many of the molecular changes that underlie fear conditioning in mammals have also been show to be important for Palovian conditioning in invertebrates, showing the conserved nature of the molecular mechanisms of learning and memory.

The advances made in understanding Pavlovian fear conditioning made it possible to revisit the neural system of avoidance and related aversive instrumental behaviors ( Cain and LeDoux, 2007 ; Cain et al., 2010 ; LeDoux et al., 2009 ; Choi et al, 2010 ; Amorapanth et al, 2000 ; Lazaro-Munoz et al., 2010 ). This work showed that as in fear conditioning, the LA is essential for forming the CS-US association. But in contrast to fear conditioning, in avoidance information flows from the LA to the basal amygdala (not to the CE). Extrapolating from appetitive conditioning finding ( Everitt et al, 1989 , 1999 ; Cardinal et al, 2002 ), it has been proposed that connections from the basal amygdala to the ventral striatum allow the CS-US association to control aversively motivated instrumental behavior.

Avoidance responses are not emotional responses per se. They are simply responses. An animal can learn to avoid harm by running, climbing, pressing, swimming, or even remaining stationary. The animal learns to do what it needs to do to attain safety. But the same responses could be used to obtain food if the animal is hungry and those responses are a way to gain access to food. In contrast, in Pavlovian fear conditioning the CS elicits specific emotional responses, fear or defense responses. Researchers were much more inclined to discuss Pavlovian conditioning results specifically in terms of fear/defense circuits.

Comparative Observations

Amygdala areas have been implicated in fear conditioning in a variety of mammals, including rats, mice, rabbits, and monkeys (see LeDoux, 1996 , 2000 ; Johansen et al, in review ; LeDoux, 2000 ; Maren, 2001 , 2005 ; Rodrigues et al, 2004 ; Davis, 1992 ; Davis et al., 1997 ; Fanselow and Poulos, 2005 ; Pape and Pare, 2010 ). This suggests strong conservation of the circuitry within mammals, including humans. Indeed, a large body of work implicates the human amygdala in fear conditioning and in instrumental responses like avoidance ( Phelps and LeDoux, 2005 ; Phelps, 2006 ; Whalen et al., 2004 ; Dolan and Vuilleumier, 2003 ; Whalen and Phelps, 2009 ; Delgado et al., 2009 ; Labar, 2003 ; Ousdal et al., 2008 ; Gianaros et al., 2008 ; Damasio, 1994 ; Bechara et al., 1995 ). Thus, damage to the amygdala in humans prevents fear conditioning from occurring and functional imaging studies show that activity increases in the amygdala during fear conditioning. Additionally, a number of studies have found amygdala activation in response to angry or fearful faces, considered to be unconditioned threat stimuli ( Adolphs, 2008 ). Thus, findings involving both lesion studies and functional imaging suggest strong correspondence with the animal literature, at least at a gross anatomical level. Techniques available for studying the human brain do not allow precise localization of specific nuclei, though some progress is being made in this regard ( Davis et al., 2011 ; Bach et al., 2011 ).

An important question concerns the nature of the amygdala in non-mammals and the role of the homologous structure in fear conditioning. According to classic view, areas such as the amygdala, being paleomammalian structures, should not exist in reptiles. However, in the 1970s, Cohen (1975) claimed to have indentified the amygdala in avian species and found that lesions of this regions disrupted of Pavlovian fear conditioning in pigeons. More recently, there has been much debate about what constitutes the amygdala, and specifically individual amygdala nuclei, in reptiles and birds ( Karten, 1997 ; Martinez-Garcia et al., 2002 ; Lanuza et al., 1998 ; Moreno and Gonzalez, 2007 ; Bruce and Neary, 1995 ). Using connectivity patterns established in mammals, areas believed to be homologous to the lateral and central nucleus have been identified in lizards ( Martinez-Garcia et al., 2002 ; Lanuza et al., 1998 ). When threatened, these animals undergo tonic immobility, and damage to the CE homologue interferes with this defensive response ( Davies et al., 2002 ).

Much more work is needed to resolve what constitutes the amygdala in non-mammalian vertebrates and to determine whether the functions of the amygdala known to exist in mammals have some relation to the function of the homologous regions in the vertebrate ancestors of mammals.

Amygdala Contributions to Other Emotions

While the contribution of the amygdala to fear has been most thoroughly studied, it is clear that the amygdala contributes to other emotional states as well. A relatively large body of research has focused on the role of the amygdala in processing of rewards and the use of rewards to motivate and reinforce behavior ( Cardinal et al., 2002 ; Everitt et al., 1999 ; Holland and Gallagher, 2004 ; Murray, 2007 ; Salzman et al., 2007 ; Nishijo et al., 2008 ). As with aversive conditioning, the lateral, basal, and central amygdala have been implicated in different aspects of reward learning and motivation, as well as drug addiction. The amygdala has also been implicated in emotional states associated with aggressive, maternal, sexual, and ingestive (eating and drinking) behaviors ( Bahar et al., 2003 ; Galaverna et al., 1993 ; Miczek et al., 2007 ; Pfaff, 2005 ; Siegel and Edinger, 1981 ). Less is known about the detailed circuitry involved in these emotional states than is known about fear.

Emotional Evolution in Perspective

There is no shortage of theories that have speculated about the relation of emotion circuits to brain evolution. In the tradition of Darwin, basic emotions theorists have proposed that certain emotions are innate, in part because they are expressed the same in people around the world ( Tomkins, 1962 ; Ekman, 1977 , 1992 ; Izard, 1971 , 1992 ; Plutchik, 1980 ; Buck, 1981 ). These innate emotions are said to be mediated by affect programs in the brain. An affect program, in effect, is psychological description of a dedicated neural circuit. Some neuroscientist have adopted the basic emotions idea, and have proposed specific circuits for different basic emotions ( Panksepp, 1980 , 1998 , 2005 ), though the basic emotions discussed do not completely correspond with those proposed in the psychological theories.

The above discussion of the amygdala and its role in fear and defense might be construed as a mini-version of basic emotions theory, a version focused on one basic emotion. However, there is a fundamental difference between the approach I take and the approach of basic emotions theorists.

The goal of basic emotions theories is to understand subjective states of conscious experience that humans label with emotion words (fear, love, sadness, joy, etc). Their goal is to understand “feelings.” This is also true of brain science theories of emotion focused on basic emotions. Panksepp (1980 , 1998 , 2005 ), for example, searches for brain systems in animals that underlie feelings in the animals as a way of understanding the brain systems that underlie human feelings. Vocalizations that result from tickling a rat are ways of indexing joyful or pleasurable feelings in the rat brain, and freezing, flight and fight behaviors are markers of fearful feelings.

The approach I take is quite different ( LeDoux, 1984 , 1996 , 2002 , 2008 ). I use emotional behavior as a means of indexing circuits that have evolved to allow organisms to deal with challenges and opportunities in their environments. I make no assumption about what an animal is feeling, since I believe it is not possible to scientifically measure, and thus not possible to research, feelings in animals other than humans. I do not deny that other animals may have feelings. I simply question whether these can be studied using scientific methods. Beyond this methodological barrier, I am also critical of attempts to equate feelings in humans and other animals for other reasons. First, most studies that have explored conscious experience in humans have found that when information (including emotional information) reaches awareness the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is active, and if information is experimentally prevented from reaching awareness this area is not active (for summary see LeDoux, 2008 ). The dorsolateral granular prefrontal cortex is a unique primate specialization ( Preuss, 1995 ; Wise, 2008 ) and has features in the human brain that are lacking in other primates (Semendeferi et al., 2011). If human conscious experience depends on these unique features of brain organization, we should be cautious about attributing the kinds of mental states made possible by these features to animals that lack the feature or the brain region. Second, language is a unique human capacity, and conscious experience, including emotional experience, is influenced by language. The once disputed idea that language, and the cognitive processes required to support language functions, add complexity to human experience, has regained respect ( Lakoff, 1987 ; Lucy, 1997 ). In the absence of language experience cannot be partitioned in the same way-- English speakers can partition fear and anxiety into more than 30 categories ( Marks, 1987 ). The diversity with which non-verbal organisms can conceptualize the world and their experiences in it is thus likely constricted by the absence of language.

In sum, basic tendencies to detect and respond to significant events are present in the simplest single cell organisms, and persist throughout all invertebrates and vertebrates. Within vertebrates, the overall brain plan is highly conserved, though differences in size and complexity also exist. The forebrain differs the most between mammals and other vertebrates, though the old notion that the evolution of mammals led to radical changes such that new forebrain structures were added has not held up. Thus, the idea that mammalian evolution is characterized by the addition of a limbic system (devoted to emotion) and a neocortex (devoted to cognition) is flawed. Modern efforts to understand the brain mechanisms of emotion have made more progress by focusing on specific emotion systems, like the fear or defense system, rather than on efforts to find a single brain system devoted to emotion. Also, progress has been made in animal studies by focusing on emotion in terms of brain circuits that contribute to behaviors related to survival functions. Efforts to use scientific methods identify circuits in animals that might correspond to circuits in the human brain that are responsible for conscious feelings are not likely to succeed since we have no way of scientifically measuring feelings in animals. Conscious feelings are an important topic, but one that is best pursued through studies of humans.

Fear is the emotion most thoroughly understood in the brain. Much of the progress made has involved studies of Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats. During conditioning the conditioned stimulus (CS), usually a tone, and the unconditioned stimulus (US), usually a footschock, converge in the lateral nuclecus of the amygdala (LA) to induce synaptic plasticity of the CS inputs (CS–US convergence not shown). The CS is then able to flow through amygdala circuits to the central nucleus (CE) to control the expression of hard-wired, automatic, defensive reactions (freezing behavior, autonomin nervous system, ANS, activity, and hormonal release). CE outputs also activate networks in that control the release of neuromodulators, such as norepinephrine (NE), dopamine (DA), acetylcholine (ACh), and serotonin (5HT) throughtout the brain. These, like hormonal feedback, help add intensity to and prolong the duration of the aroused state. In addition to these various automatic responses controlled by CE, the LA also sends information, via the basal nucleus (B) to the ventral striatum, especially the nucleus accumbens. The latter connections are likely to be involved in the invigoration of goal-directed behaviors that allow the organism to act in certain ways on the basis of past instrumental learning or on-the-spot decisions about how to cope with the threat. Other abbreviations: ITC, intercalated nuclei of the amydala; CG, central gray; LH, lateral hypothalamus; PVN, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; VP, ventral pallidum.

- Adolphs R. Fear, faces, and the human amygdala. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2008; 18 :166–172. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amaral DG, Price JL, Pitkänen A, Carmichael ST. Anatomical organization of the primate amygdaloid complex. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The Amygdala: Neurobiological Aspects of Emotion, Memory, and Mental Dysfunction. New York: Wiley-Liss, Inc; 1992. pp. 1–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- Amorapanth P, LeDoux JE, Nader K. Different lateral amygdala outputs mediate reactions and actions elicited by a fear-arousing stimulus. Nature Neuroscience. 2000; 3 :74–79. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ariëns Kappers CU, Huber CG, Crosby EC. The Comparative Anatomy of the Nervous System of Vertebrates, Including Man. New York: Macmillan Company; 1936. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bach DR, Talmi D, Hurlemann R, Patin A, Dolan RJ. Automatic relevance detection in the absence of a functional amygdala. Neuropsychologia. 2011; 49 :1302–1305. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bahar A, Samuel A, Hazvi S, Dudai Y. The amygdalar circuit that acquires taste aversion memory differs from the circuit that extinguishes it. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003; 17 :1527–1530. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bard P. A diencephalic mechanism for the expression of rage with special reference to the sympathetic nervous system. American Journal of Physiology. 1928; 84 :490–515. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bechara A, Tranel D, Damasio H, Adolphs R, Rockland C, Damasio AR. Double dissociation of conditioning and declarative knowledge relative to the amygdala and hippocampus in humans. Science. 1995; 269 :1115–1118. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blair HT, Schafe GE, Bauer EP, Rodrigues SM, LeDoux JE. Synaptic plasticity in the lateral amygdala: a cellular hypothesis of fear conditioning. Learn & Memory. 2001; 8 :229–242. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC. Crouching as an index of fear. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1969; 67 :370–375. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolles RC, Fanselow MS. A perceptual-defensive-recuperative model of fear and pain. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1980; 3 :291–323. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruce LL, Neary TJ. The limbic system of tetrapods: a comparative analysis of cortical and amygdalar populations. Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 1995; 46 :224–234. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buck R. The evolution and development of emotion expression and communication. In: Brehm SS, Kassin SM, Gibbons FX, editors. Developmental Social Psychology. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1981. pp. 127–151. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler AB, Hodos W. Comparative Vertebrate Neuroanatomy: Evolution and Adaptation. 2. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cain CK, Choi JS, LeDoux JE. Active Avoidance and Escape Learning. In: Koob G, Thompson R, Le Moal M, editors. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience. New York: Elsevier; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cain CK, LeDoux JE. Escape from fear: a detailed behavioral analysis of two atypical responses reinforced by CS termination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2007; 33 :451–463. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cannon WB. Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear, and rage. Vol. 2. New York: Appleton; 1929. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, Everitt BJ. Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002; 26 :321–352. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter CS, Botvinick MM, Cohen JD. The contribution of the anterior cingulate cortex to executive processes in cognition. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 1999; 10 :49–57. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter CS, Braver TS, Barch DM, Botvinick MM, Noll D, Cohen JD. Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection, and the online monitoring of performance. Science. 1998; 280 :747–749. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi JS, Cain CK, LeDoux JE. The role of amygdala nuclei in the expression of auditory signaled two-way active avoidance in rats. Learn & Memory. 2010; 17 :139–147. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen DH. Involvement of the avian amygdalar homologue (archistriatum posterior and mediale) in defensively conditioned heart rate change. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1975; 160 :13–35. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Damasio A. Descarte’s error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Gosset/Putnam; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Darwin C. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: Fontana Press; 1872. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davies DC, Martinez-Garcia F, Lanuza E, Novejarque A. Striato-amygdaloid transition area lesions reduce the duration of tonic immobility in the lizard Podarcis hispanica. Brain Research Bulletin. 2002; 57 :537–541. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis FC, Johnstone T, Mazzulla EC, Oler JA, Whalen PJ. Regional response differences across the human amygdaloid complex during social conditioning. Cerebral Cortex. 2011; 20 :612–621. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1992; 15 :353–375. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis M, Walker DL, Lee Y. Amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: differential roles in fear and anxiety measured with the acoustic startle reflex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 1997; 352 :1675–1687. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Delgado MR, Jou RL, LeDoux JE, Phelps EA. Avoiding negative outcomes: tracking the mechanisms of avoidance learning in humans during fear conditioning. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009; 3 :33. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dolan RJ, Vuilleumier P. Amygdala automaticity in emotional processing. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003; 985 :348–355. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eichenbaum H. The cognitive neuroscience of memory. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P. Biological and cultural contributions to body and facial movement. In: Blacking J, editor. The Anthropology of the Body. London: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 39–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P. An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion. 1992; 6 :169–200. [ Google Scholar ]

- Everitt BJ, Cador M, Robbins TW. Interactions between the amygdala and ventral striatum in stimulus- reward associations: studies using a second-order schedule of sexual reinforcement. Neuroscience. 1989; 30 :63–75. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Everitt BJ, Parkinson JA, Olmstead MC, Arroyo M, Robledo P, Robbins TW. Associative processes in addiction and reward. The role of amygdala-ventral striatal subsystems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999; 877 :412–438. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fanselow MS, Poulos AM. The neuroscience of mammalian associative learning. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005; 56 :207–234. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Galaverna OG, Seeley RJ, Berridge KC, Grill HJ, Epstein AN, Schulkin J. Lesions of the central nucleus of the amygdala. I: Effects on taste reactivity, taste aversion learning and sodium appetite. Behavioural Brain Research. 1993; 59 :11–17. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gianaros PJ, Sheu LK, Matthews KA, Jennings JR, Manuck SB, Hariri AR. Individual differences in stressor-evoked blood pressure reactivity vary with activation, volume, and functional connectivity of the amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008; 28 :990–999. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Herrick CJ. The functions of the olfactory parts of the cerebral cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U S A. 1933; 19 :7–14. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holland PC, Gallagher M. Amygdala-frontal interactions and reward expectancy. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2004; 14 :148–155. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Isaacson RL. The Limbic System. New York: Plenum Press; 1982. [ Google Scholar ]

- Izard CE. The Face of Emotion. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1971. [ Google Scholar ]

- Izard CE. Basic emotions, relations among emotions, and emotion-cognition relations. Psychological Review. 1992; 99 :561–565. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johansen J, Cain C, Ostroff L, LeDoux JE. Neural Mechanisms of Fear Learning and Memory. Cell in review. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kandel ER, Klein M, Castellucci VF, Schacher S, Goelet P. Some principles emerging from the study of short- and long-term memory. Neuroscience Research. 1986; 3 :498–520. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kandel ER, Spencer WA. Cellular neurophysiological approaches to the study of learning. Physiological Reviews. 1968; 48 :65–134. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kapp BS, Frysinger RC, Gallagher M, Haselton JR. Amygdala central nucleus lesions: effect on heart rate conditioning in the rabbit. Physiology & Behavior. 1979; 23 :1109–1117. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Karten HJ. Evolutionary developmental biology meets the brain: the origins of mammalian cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U S A. 1997; 94 :2800–2804. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim MJ, Loucks RA, Palmer AL, Brown AC, Solomon KM, Marchante AN, Whalen PJ. Behavioural Brain Research. 2011. The structural and functional connectivity of the amygdala: From normal emotion to pathological anxiety. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kluver H, Bucy PC. “Psychic blindness” and other symptoms following bilateral temporal lobectomy in rhesus monkeys. American Journal of Physiology. 1937; 119 :352–353. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kotter R, Meyer N. The limbic system: a review of its empirical foundation. Behavioural Brain Research. 1992; 52 :105–127. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LaBar KS. Emotional memory functions of the human amygdala. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2003; 3 :363–364. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lakoff G. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the mind. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1987. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lanuza E, Belekhova M, Martinez-Marcos A, Font C, Martinez-Garcia F. Identification of the reptilian basolateral amygdala: an anatomical investigation of the afferents to the posterior dorsal ventricular ridge of the lizard Podarcis hispanica. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1998; 10 :3517–3534. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lazaro-Munoz G, LeDoux JE, Cain CK. Sidman instrumental avoidance initially depends on lateral and Basal amygdala and is constrained by central amygdala-mediated Pavlovian processes. Biological Psychiatry. 2010; 67 :1120–1127. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE. Cognition and emotion: processing functions and brain systems. In: Gazzaniga MS, editor. Handbook of Cognitive Neuroscience. New York: Plenum Publishing Corp; 1984. pp. 357–368. [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion. In: Plum F, editor. Handbook of Physiology. 1: The Nervous System. Vol V, Higher Functions of the Brain. Bethesda: American Physiological Society; 1987. pp. 419–460. [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion and the limbic system concept. Concepts in Neuroscience. 1991; 2 :169–199. [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE. The Emotional Brain. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2000; 23 :155–184. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE. Synaptic Self: How our brains become who we are. New York: Viking; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux J. The amygdala. Current Biology. 2007; 17 :R868–874. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE. Emotional colouration of consciousness: how feelings come about. In: Weiskrantz L, Davies M, editors. Frontiers of Consciousness: Chichele Lectures. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 69–130. [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE, Sakaguchi A, Reis DJ. Subcortical efferent projections of the medial geniculate nucleus mediate emotional responses conditioned to acoustic stimuli. Journal Neuroscience. 1984; 4 :683–698. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LeDoux JE, Schiller D, Cain C. Emotional Reaction and Action: From Threat Processing to Goal-Directed Behavior. In: Gazzaniga MS, editor. The Cognitive Neurosciences. 4. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 905–924. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lucy JA. Linguistic Relativity. Annual Review of Anthropology. 1997; 26 :291–312. [ Google Scholar ]

- MacLean PD. Psychosomatic disease and the “visceral brain”: recent developments bearing on the Papez theory of emotion. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1949; 11 :338–353. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MacLean PD. Some psychiatric implications of physiological studies on frontotemporal portion of limbic system (visceral brain) Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1952; 4 :407–418. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MacLean PD. The triune brain, emotion and scientific bias. In: Schmitt FO, editor. The Neurosciences: Second Study Program. New York: Rockefeller University Press; 1970. pp. 336–349. [ Google Scholar ]

- Macnab RM, Koshland DE., Jr The gradient-sensing mechanism in bacterial chemotaxis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U S A. 1972; 69 :2509–2512. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maren S. Neurobiology of Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001; 24 :897–931. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maren S. Synaptic mechanisms of associative memory in the amygdala. Neuron. 2005; 47 :783–786. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marks I. Fears, Phobias, and Rituals: Panic, Anxiety and Their Disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 1987. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martinez-Garcia F, Martinez-Marcos A, Lanuza E. The pallial amygdala of amniote vertebrates: evolution of the concept, evolution of the structure. Brain Research Bulletin. 2002; 57 :463–469. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miczek KA, de Almeida RM, Kravitz EA, Rissman EF, de Boer SF, Raine A. Neurobiology of escalated aggression and violence. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007; 27 :11803–11806. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moreno N, Gonzalez A. Evolution of the amygdaloid complex in vertebrates, with special reference to the anamnio-amniotic transition. Journal of Anatomy. 2007; 211 :151–163. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray EA. The amygdala, reward and emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007; 11 :489–497. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nauta WJH, Karten HJ. A general profile of the vertebrate brain, with sidelights on the ancestry of cerebral cortex. In: Schmitt FO, editor. The Neurosciences: Second Study Program. New York: The Rockefeller University Press; 1970. pp. 7–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nishijo H, Hori E, Tazumi T, Ono T. Neural correlates to both emotion and cognitive functions in the monkey amygdala. Behavioural Brain Research. 2008; 188 :14–23. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Northcutt RG, Kaas JH. The emergence and evolution of mammalian neocortex. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995; 18 :373–379. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Keefe J, Nadel L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1978. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ousdal OT, Jensen J, Server A, Hariri AR, Nakstad PH, Andreassen OA. The human amygdala is involved in general behavioral relevance detection: evidence from an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging Go-NoGo task. Neuroscience. 2008; 156 :450–455. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Panksepp J. Hypothalamic integration of behavior: rewards, punishments, and related psychological processes. In: Morgane PJ, Panksepp J, editors. Handbook of the Hypothalamus. Vol. 3, Behavioral Studies of the Hypothalamus. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1980. pp. 289–431. [ Google Scholar ]

- Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience. New York: Oxford U. Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Panksepp J. Affective consciousness: Core emotional feelings in animals and humans. Consciousness and Cognition. 2005; 14 :30–80. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pape HC, Pare D. Plastic synaptic networks of the amygdala for the acquisition, expression, and extinction of conditioned fear. Physiological Reviews. 2010; 90 :419–463. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Papez JW. A proposed mechanism of emotion. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 1937; 79 :217–224. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfaff D. Hormone-driven mechanisms in the central nervous system facilitate the analysis of mammalian behaviours. Journal of Endocrinology. 2005; 184 :447–453. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Phelps EA. Emotion and cognition: insights from studies of the human amygdala. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006; 57 :27–53. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Phelps EA, LeDoux JE. Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: from animal models to human behavior. Neuron. 2005; 48 :175–187. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pitkänen A, Savander V, LeDoux JE. Organization of intra-amygdaloid circuitries in the rat: an emerging framework for understanding functions of the amygdala. Trends in Neuroscience. 1997; 20 :517–523. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Plutchik R. Emotion: A Psychoevolutionary Synthesis. New York: Harper & Row; 1980. [ Google Scholar ]

- Preuss TM. Do rats have a prefrontal cortex? The Rose-Woolsey-Akerty Program Reconsidered. J Cog Neurosci. 1995; 7 :1–24. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Repa JC, Muller J, Apergis J, Desrochers TM, Zhou Y, LeDoux JE. Two different lateral amygdala cell populations contribute to the initiation and storage of memory. Nature Neuroscience. 2001; 4 :724–731. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodrigues SM, Schafe GE, LeDoux JE. Molecular mechanisms underlying emotional learning and memory in the lateral amygdala. Neuron. 2004; 44 :75–91. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sah P, Westbrook RF, Luthi A. Fear conditioning and long-term potentiation in the amygdala: what really is the connection? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008; 1129 :88–95. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Salzman CD, Paton JJ, Belova MA, Morrison SE. Flexible neural representations of value in the primate brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007; 1121 :336–354. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sarter MF, Markowitsch HJ. Involvement of the amygdala in learning and memory: a critical review, with emphasis on anatomical relations. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1985; 99 :342–380. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schafe GE, Nader K, Blair HT, LeDoux JE. Memory consolidation of Pavlovian fear conditioning: a cellular and molecular perspective. Trends in Neuroscience. 2001; 24 :540–546. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sehlmeyer C, Schoning S, Zwitserlood P, Pfleiderer B, Kircher T, Arolt V, Konrad C. Human fear conditioning and extinction in neuroimaging: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2009; 4 :e5865. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Semendeferi K, Teffer K, Buxhoeveden DP, Park MS, Bludau S, Amunts K, Travis K, Buckwalter J. Spatial Organization of neurons in the frontal pole sets humans apart from great apes. Cerebral Cortex. 2010; 21 :1485–97. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shepherd G. Neurobiology. New York: Oxford; 1983. [ Google Scholar ]

- Siegel A, Edinger H. Neural control of aggression and rage behavior. In: Morgane PJ, Panksepp J, editors. Handbook of the Hypothalamus, Vol. 3, Behavioral Studies of the Hypothalamus. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1981. pp. 203–240. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith GE. The Evolution of Man. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1924. [ Google Scholar ]

- Squire L. Memory and Brain. New York: Oxford; 1987. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swanson LW. The hippocampus and the concept of the limbic system. In: Seifert W, editor. Neurobiology of the Hippocampus. London: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 3–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swanson LW. Brain Architecture: Understanding the Basic Plan. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson RF. The neurobiology of learning and memory. Science. 1986; 233 :941–947. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tischler MD, Davis M. A visual pathway that mediates fear-conditioned enhancement of acoustic startle. Brain Research. 1983; 276 :55–71. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tomkins SS. Affect, Imagery, Consciousness. New York: Springer; 1962. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiskrantz L. Behavioral changes associated with ablation of the amygdaloid complex in monkeys. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1956; 49 :381–391. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiss S. Forward frontal fields: phylogeny and fundamental function. Trends in Neuroscience. 2008; 31 :599–608. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whalen PJ, Kagan J, Cook RG, Davis FC, Kim H, Polis S, McLaren DG, Somerville LH, McLean AA, Maxwell JS, Johnstone T. Human amygdala responsivity to masked fearful eye whites. Science. 2004; 306 :2061. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whalen PJ, Phelps EA. The human amgydala. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- DOI: 10.5860/choice.192178

- Corpus ID: 143300546

The History of Emotions: An Introduction

- Jan Plamper

- Published 22 March 2015

- Psychology, History, Political Science, Philosophy, Art

169 Citations

The history of emotions: past, present, future, histories of emotion in communist and post-communist europe after 1945, labels, rationality, and the chemistry of the mind: moors in historical context, introduction to the edward elgar research handbook on law and emotion, introductory essay: emotion, affect, and the eighteenth century, an interview with jan plamper: on the history of emotions, history looks forward: interdisciplinarity and critical emotion research, emotions and the global politics of childhood, enacting musical emotions. sense-making, dynamic systems, and the embodied mind, 3 references, are emotions a kind of practice (and is that what makes them have a history) a bourdieuian approach to understanding emotion, against constructionism: the historical ethnography of emotions, the affective turn: historicising the emotions, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

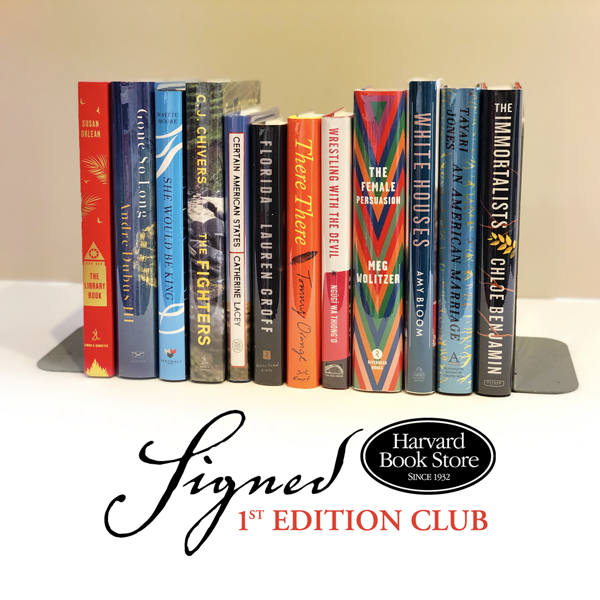

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

| Our Shelves |

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

| Gift Cards |

A Human History of Emotion: How the Way We Feel Built the World We KnowA sweeping exploration of the ways in which emotions shaped the course of human history, and how our experience and understanding of emotions have evolved along with us. "Eye-opening and thought-provoking!” (Gina Rippon, author of The Gendered Brain ) We humans like to think of ourselves as rational creatures, who, as a species, have relied on calculation and intellect to survive. But many of the most important moments in our history had little to do with cold, hard facts and a lot to do with feelings. Events ranging from the origins of philosophy to the birth of the world’s major religions, the fall of Rome, the Scientific Revolution, and some of the bloodiest wars that humanity has ever experienced can’t be properly understood without understanding emotions. Drawing on psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, art, and religious history, Richard Firth-Godbehere takes readers on a fascinating and wide ranging tour of the central and often under-appreciated role emotions have played in human societies around the world and throughout history—from Ancient Greece to Gambia, Japan, the Ottoman Empire, the United States, and beyond. A Human History of Emotion vividly illustrates how our understanding and experience of emotions has changed over time, and how our beliefs about feelings—and our feelings themselves—profoundly shaped us and the world we inhabit. There are no customer reviews for this item yet. Classic Totes Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more! Shipping & Pickup We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail! Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club! Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.  Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore © 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected] View our current hours » Join our bookselling team » We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily. Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual. Map Find Harvard Book Store » Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy » Harvard University harvard.edu »

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer. To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser . Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

What is the History of Emotions? 2019, Social History Related PapersSharon Crozier-De Rosa The Introduction to this volume introduces students to the broad field of the history of emotion, touching on its development over the last several decades, and its key dimensions in current scholarship. It then explains the structure and logic of the volume, providing hints about how it can be used by students and scholars new to the field. A final section reflects on the limitations and gaps in the volume and field more widely, and the ways that they may be filled by future research. Erin Sullivan Penelope Gouk , Helen Hills Emotions in Social Life: Social Theories and … Alexander Dean In 1941 historian Lucien Febvre challenged historians to reflect upon the emotions, stating that no historian concerned with the social life of individuals can any longer disregard their importance . Historians were quick to see, as Joanna Bourke states, that examination of the “transformations undergone by emotions within societies could provide a unique insight into everyday life .” However, the Primary problem facing historians has been how to define emotions to enable a rigorous academic study . If emotions are to have such a thing, then the historian is behoved to seek out and propose suitable methods to achieve such ends. This essay will seek to review the number of different methodological approaches that have been developed to fulfil this requirement and how such work has gleamed new historical insight. First by looking at how it has been suggested we may correctly interpret the cultural meaning of emotion from the past, from our modern vantage point. This in turn requires a review of the debates surrounding how it is proposed historical analysis of emotions be carried out, or if it can at all. Finally, exploring two fundamental methodological concepts central to the history of the emotions, by using as means of analysis the history such methods have produced, the essay will demonstrate how such studies of emotion can contribute to the wider academic practice. Andrew Kettler What Is the History of Emotions? provides historiographical narratives of the roots, current theories, and future goals for this well-established field of historical study. As part of the What Is History? series from Polity Press, which offers introductions to specific historical subfields, this edition provides lessons that can easily be used by graduate students and early career scholars who desire quick references to both the sturdy and wobbly columns that uphold the architecture of the history of emotions. Passions in Context, No. 1 © Stiftung Einstein Forum https://www.passionsincontext.de/ Barbara H Rosenwein What are some of the general methodological issues involved in writing a history of the emotions? Before answering this question, we need to address a major problem. If emotions are, as many scientists think, biological entities, universal within all human populations, do they-indeed can they-have much of a history at all? Once it is determined that they are less universal than claimed (without denying their somatic substratum), a host of problems and opportunities for the history of emotions emerge. In this paper, I propose that we study the emotions of the past by considering "emotional communi-ties" (briefly: social groups whose members adhere to the same valuations of emotions and their expression). I argue that we should take into consideration the full panoply of sources that these groups produced, and I suggest how we might most effectively interpret those sources. Finally, I consider how and why emotional change takes place, urging that the history of emotions be integrated into other sorts of histories-social, political, and intellectual . Emotion Researcher Riccardo Cristiani , Barbara H Rosenwein A conversation about the history of emotions with Nicole Eustace, Eugenia Lean, Julie Livingston, Jan Plamper, William Reddy, Barbara H. Rosenwein Margaret Mullett & Susan Ashbrook Harvey (eds) Managing Emotion: Passions, Affects and Imaginings in Byzantium Maria G. Xanthou FHEA In 1941 Lucien Febvre officially launched ‘history of emotions’ as a discipline on its own right. Ever since 1941, it has evolved into an increasingly productive and stimulating area of historical research. In the ’80s the ‘emotional’ or ‘affective’ turn was in full swing: historians interested in the history of society and mentalities in Medieval Europe and in the western world focusing on emotions. The resurgence of interest and its subsequent twenty year study of the interaction between historical conditions and the manifestations of emotions in Greek, Roman and Byzantine texts, images and material culture have already yielded its ἀπαρχαί as regards its set goal. In this thriving discipline, the historian’s task has been defined as follows: to examine the very diverse significance of emotions in society and culture in their broadest definitions (including religion, law, politics, etc.) [Chaniotis 2012, 15]. The discipline is based on the assumption that not only the way the emotions are perceived, namely feelings, but also the feelings themselves are learned. Culture and history are changing and so are feelings as well as their expression. The social relevance and potency of emotions is historically and culturally variable. In the view of many historians, emotion is, therefore, just as fundamental a category of history, as class, race or gender. Over the past years a wide array of methodological approaches have been discussed. A particular school of thought focuses on the historical analysis of emotional norms and rules under the heading of emotionology. In recent years, the history of emotions intersected with modern historiographical approaches such as conceptual history, historical constructivism and the history of the body. Thus, the methodological spectrum of the history of emotions has been enriched by performative, constructivist and practice theory approaches. Currently fundamental methodological concepts include emotive, emotional habitus and emotional practice. Additionally, there are several terms that describe the different scope and binding effect of feeling cultures such as emotional community, emotional regime and emotional style. My aim is to provide a succinct survey of the most important methodological approaches, as they have been already applied in the study of emotions in Greek, Roman and Byzantine texts, images and material culture. Loading Preview Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above. RELATED PAPERSRussell Foster Phil Hutchinson Douglas Cairns Clara Molina Richard de Koster "Introduction: Emotional Histories — Beyond the Personalization of the Past and the Abstraction of Affect Theory," Exemplaria 26.1 (2014): 3015" Stephanie J Trigg Sociological Forum Rebecca A Allahyari Patrick S. O'Donnell Canadian Bulletin of Medical History Bulletin Canadien D Histoire De La Medecine Faith Wallis Cognition & Emotion Gerrod Parrott Fayah Haussker South African Journal of Psychology Johann Louw Sherman Tan Human Affairs: Postdisciplinary Humanities & Social Sciences Quarterly Eduard Moreno Gabriel Ramazan Aras Social Psychology Quarterly Piotr Winkielman The Oxford Handbook of Affective Computing Arvid Kappas Revista de Estudios Sociales Rob Boddice , Revista de Estudios Sociales Aaron Ben-Ze'ev Psychological Concepts Louise K.W. Sundararajan A Companion to Psychological Anthropology: Modernity and Psychocultural Change. Eds. C. Casey and R. Edgerton. Oxford. Basil Blackwell. Charles Lindholm Ida Caiazza Joerg Wettlaufer RELATED TOPICS

History of EmotionsAfter sixteen successful years of research, the Center for the History of Emotions will conclude its work on 30 June 2024 . Our thanks go to the many scholars who shared their ideas and knowledge , were guest researchers, gave lectures or explored new avenues of the history of emotions with us as collaboration partners. Do emotions have a history? And do they make history? These are the questions that the Research Center History of Emotions seeks to answer. To explore the emotional orders of the past, historians work closely with psychologists and education specialists. In addition, they draw on the expertise of anthropologists, sociologists, musicologists and scholars working on literature and art. Our research rests on the assumption that emotions – feelings and their expressions – are shaped by culture and learnt/acquired in social contexts. What somebody can and may feel (and show) in a given situation, towards certain people or things, depends on social norms and rules. It is thus historically variable and open to change. A central objective of the Research Center is to trace and analyse the changing norms and rules of feeling. We therefore look at different societies and see how they develop and organise their emotional regimes, codes, and lexicons. Research concentrates on the modern period (18th to 20th centuries). Geographically, it includes both western and eastern societies (Europe, North America and South Asia). Special attention is paid to institutions that have a strong impact on human behaviour and its emotional underpinnings, such as the family, law, religion, the military, the state. Equally important to the Center's research programme is the historical significance of emotions. Emotions are said to motivate human action and thus influence social, political, and economic developments. In this capacity, they are and have been a privileged object of manipulation and instrumentalisation. Who appealed to what kind of emotions for what reasons? To what degree did emotions play a part in/contribute to the formation and dissolution of social groups, communities and movements? These and other questions open doors to a new field of research, one which aims to thoroughly historicise a crucial element of human development.  Conferences & Calls for Papers Monographs and Editions In the Media Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings . Login Alert

A History of Emotions, 1200–1800

Book descriptionThe history of emotions is an expanding field of research. The essays in this collection examine emotional responses to art and music, the role of emotions in contemporary notions of gender and sexuality and theoretical questions as to their use. Bringing together a series of case studies from points across the medieval and early modern periods, the authors in this volume provide fascinating glimpses into human emotional experience across a variety of cultures. "‘From this collection we discover that emotions were the objects of constant vigilance and effort, shaped by ever changing ideas and norms concerning the self, the holy, the mind, the arts, friendship, sickness and health. Overall, a fascinating sampling of the best recent work in the history of emotions, framed by a strong introduction and a provocative methodological essay by Barbara H Rosenwein.’"

Refine ListActions for selected content:.

Save content toTo save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to . To save content items to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle . Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply. Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service . Save SearchYou can save your searches here and later view and run them again in "My saved searches". Frontmatter pp i-ivContents pp v-vi, list of contributors pp vii-x, list of figures pp xi-xii, introduction pp 1-6.

I - Theoretical Issues1 - theories of change in the history of emotions pp 7-20.

2 - Ottoman Love: Preface to a Theory of Emotional Ecology pp 21-48

II - Emotional Repertoires3 - preachers, saints, and sinners: emotional repertoires in high medieval religious role models pp 49-64.

4 - Theology and Interiority: Emotions as Evidence of the Working of Grace in Elizabethan and Stuart Conversion Narratives pp 65-78

5 - ‘Finer’ Feelings: Sociability, Sensibility and the Emotions of Gens de Lettres in Eighteenth-Century France pp 79-94

III - Music and Art6 - music as wonder and delight: construction of gender in early modern opera through musical representation and arousal of emotions pp 95-104.

7 - Politesse and Sprezzatura : The History of Emotions in the Art of Antoine Watteau pp 105-118

IV - Gender, Sexuality and the Body8 - emotions and gender: the case of anger in early modern english revenge tragedies pp 119-134.

9 - Beauty, Masculinity and Love Between Men: Configuring Emotions with Michael Drayton's Peirs Gaveston pp 135-152

10 - ‘Pray, Dr, is there Reason to Fear a Cancer?’ Fear of Breast Cancer in Early Modern Britain pp 153-166

V - Uses of Emotions11 - the little girl who could not stop crying: the use of emotions as signifiers of true conversion in eighteenth-century greenland pp 167-180.

12 - The Political Rhetoric of Tears in Early Modern Sweden pp 181-206Notes pp 207-250, index pp 251-259, full text views. Full text views reflects the number of PDF downloads, PDFs sent to Google Drive, Dropbox and Kindle and HTML full text views for chapters in this book. Book summary page viewsBook summary views reflect the number of visits to the book and chapter landing pages. * Views captured on Cambridge Core between #date#. This data will be updated every 24 hours. Usage data cannot currently be displayed.  TED is supported by ads and partners 00:00 The history of human emotions

Sign in through your institution

AHR Conversation: The Historical Study of EmotionsNicole Eustace is Associate Professor of History and Co-Director of the Atlantic History Program at New York University. She received her B.A. from Yale University and her Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania, where she received her training as a historian of eighteenth-century British America and the early United States. Her works include 1812: War and the Passions of Patriotism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012) and Passion Is the Gale: Emotion, Power, and the Coming of the American Revolution (University of North Carolina Press, 2008), as well as articles and essays in the William & Mary Quarterly , the Journal of Social History , the Journal of American History , and numerous encyclopedias and anthologies.

Nicole Eustace, Eugenia Lean, Julie Livingston, Jan Plamper, William M. Reddy, Barbara H. Rosenwein, AHR Conversation: The Historical Study of Emotions, The American Historical Review , Volume 117, Issue 5, December 2012, Pages 1487–1531, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/117.5.1487

In the past few years, the AHR has published five “Conversations,” each on a subject of interest to a wide range of historians: “On Transnational History” (2006), “Religious Identities and Violence” (2007), “Environmental Historians and Environmental Crisis” (2008), “Historians and the Study of Material Culture” (2009), and “Historical Perspectives on the Circulation of Information” (2011). For each the process has been the same: the Editor convenes a group of scholars with an interest in the topic who, via e-mail over the course of several months, conduct a conversation, which is then lightly edited and footnoted, finally appearing in the December issue. The goal has been to provide readers with a wide-ranging consideration of a topic at a high level of expertise, in which the participants are recruited across several fields and periods. It is the sort of publishing project that this journal is uniquely positioned to undertake. This year's topic is “The Historical Study of Emotions.” Given the expanding range of new methodological and disciplinary forays among historians in recent years, it may be too much to proclaim that we are witnessing an “Emotional Turn.” (Indeed, one conclusion that might be drawn from the June 2012 AHR Forum on “Historiographic ‘Turns’ in Critical Perspective” is that the very concept of “turns” may have outlived its intellectual usefulness.) But it cannot be denied that the study of emotions has become a thriving pursuit among historians from many different areas and periods. Not only does its emergence as a legitimate subfield foster the interrogation of descriptors—love, hate, resentment, passions, pity, happiness, and the like—that historians are more often likely to use uncritically if at all; it also allows for the crossing of the boundaries between private and public, the personal and collective, that often constrain our work. To be sure, a major problem with the study of emotions is how we can access the emotional lives of people in past times: is it possible to go beyond emotional expressions —usually conveyed in language—and attain some assurance that these are indicative of actual emotional states ? This is only one of the questions confronted in the course of this wide-ranging conversation. Joining the Editor in this conversation are Nicole Eustace, a historian of early America; Eugenia Lean, who studies modern Chinese history, literature, and culture; Julie Livingston, a historian who works in Africa; Jan Plamper, a specialist in Soviet and Russian history; William M. Reddy, who has written widely on modern European as well as comparative history; and Barbara H. Rosenwein, whose research has ranged across the religious, social, and intellectual history of the Middle Ages.  American Historical Association membersPersonal account.

Institutional accessSign in with a library card.

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways: IP based accessTypically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account. Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.