Shell Change Management Case Study

Welcome to our blog post on a Shell change management case study.

In today’s dynamic business landscape, change is inevitable, and organizations must constantly adapt to stay relevant and competitive.

However, change can be difficult to implement and manage effectively, especially in large organizations with complex structures and processes.

This is where change management comes into play – a structured approach to transitioning individuals, teams, and organizations from a current state to a desired future state.

In this case study, we will explore how Shell successfully managed a major change initiative, the strategies they employed, and the outcomes achieved.

We will also discuss the lessons learned from Shell’s experience and how other organizations can apply them to their own change management initiatives.

Brief History and Growth of Shell

Shell, officially known as Royal Dutch Shell, is a multinational oil and gas company headquartered in The Hague, Netherlands, and incorporated in the United Kingdom.

The company was formed in 1907 as a result of a merger between Royal Dutch Petroleum Company and Shell Transport and Trading Company Limited.

Shell’s early growth was fueled by its expansion into new markets and its exploration and production activities around the world, which enabled the company to become one of the largest oil companies in the world by the mid-20th century.

In recent years, Shell has diversified its business to include renewable energy, chemicals, and power, reflecting the company’s commitment to sustainability and the energy transition.

Today, Shell operates in over 70 countries and employs around 87,000 people worldwide.

External Factors of Change for Shell

- Increasing competition: Shell faced intense competition from other major oil and gas companies as well as new players in the market, particularly in the emerging markets. This put pressure on the company to find ways to differentiate itself and remain competitive.

- Changing customer demands: As the world became more environmentally conscious, customers began to demand cleaner, more sustainable energy solutions. This meant that Shell had to adapt its business model to incorporate more renewable energy options.

- Regulatory changes: Governments around the world were introducing new regulations aimed at reducing carbon emissions and promoting sustainable energy solutions. This meant that Shell had to comply with new rules and regulations, which could be expensive and time-consuming.

- Technological advancements : The rapid pace of technological change meant that Shell had to keep up with new innovations in areas such as exploration, production, and distribution of oil and gas. This required significant investment in research and development and the adoption of new technologies.

Internal Factors of change for Shell

- Complex organizational structure: Shell’s organizational structure was complex and hierarchical, with many layers of management and decision-making. This made it difficult to implement changes quickly and efficiently.

- Siloed business units: Shell’s business units were often siloed and did not communicate effectively with each other. This led to duplication of effort, inefficiencies, and missed opportunities.

- Resistant culture: Shell had a culture that was resistant to change, with many employees comfortable with the status quo. This made it challenging to get buy-in from employees for new initiatives and to implement change successfully.

- Cost pressures: As the oil and gas industry became more competitive, Shell faced increasing pressure to reduce costs and improve efficiency. This required a major overhaul of its operations and processes

Key Strategies of Successful Change Management Implementation by Shell

The change management strategy at Shell was designed to fit the specific needs and culture of the company, rather than trying to impose a one-size-fits-all approach. This helped to build buy-in and engagement among employees, and ensure that the change initiative was successful.

Following are the key strategies of successful change management implemented by Shell.

- Leveraging the existing culture: Rather than trying to change the culture at Shell, the change management strategy was designed to leverage the existing culture and build on its strengths. For example, Shell’s focus on safety and operational excellence was used as a foundation for the change initiative, with a strong emphasis on maintaining these values while driving efficiency and innovation.

- Engaging employees: Shell recognized that its employees were a critical component of the change initiative, and so the strategy was designed to engage employees at all levels of the organization. This involved creating opportunities for employees to provide feedback, share ideas, and participate in the development and implementation of the initiative.

- Flexibility and agility: Shell’s organizational structure and processes were complex and hierarchical, which could make it challenging to implement change quickly and efficiently. To address this, the change management strategy emphasized flexibility and agility, with a focus on breaking down silos and empowering employees to make decisions and take action.

- Measurement and metrics: Shell is a data-driven company, and so the change management strategy emphasized the importance of measurement and metrics in tracking progress and ensuring accountability. However, the metrics used were tailored to fit the specific needs of the change initiative, with a focus on outcomes that were important to Shell’s business objectives and culture.

Challenges of Implementation of Change Initiatives

While the change initiative at Shell was ultimately successful, there were several roadblocks and challenges that arose during implementation. Here are a few examples:

- Resistance to change: As with any change initiative, there was some resistance to the changes being implemented. This was particularly true among employees who had been with the company for many years and were accustomed to the old ways of working. Shell addressed this by emphasizing the benefits of the change, providing regular communication and updates, and involving employees in the process as much as possible.

- Complexity of the organization: Shell is a large and complex organization, with many different business units and functions. This made it challenging to implement change consistently across the organization. Shell addressed this by adopting a flexible and adaptable approach, and by empowering employees to make decisions and take action at the local level.

- Resource constraints: Implementing change can be resource-intensive, and Shell faced some challenges in terms of funding, staffing, and other resources. Shell addressed this by prioritizing the initiative and allocating resources strategically, and by leveraging existing capabilities and resources where possible.

- Change fatigue: Shell had undergone several change initiatives in the past, which had left some employees feeling fatigued and skeptical about the latest initiative. Shell addressed this by emphasizing the benefits of the change, providing regular communication and updates, and involving employees in the process as much as possible.

The biggest outcome of successful implementation of change by Shell

The biggest outcome of the successful implementation of change by Shell was the transformation of the organization from a traditional oil and gas company to a more agile, customer-focused, and innovative organization. This transformation enabled Shell to adapt to a rapidly changing market and stay competitive, while also delivering significant benefits to customers, employees, and shareholders.

By streamlining processes, eliminating redundancies, and improving communication and collaboration, Shell was able to increase efficiency and reduce costs. By better understanding customer needs and preferences, and by providing more responsive and personalized service, Shell was able to improve customer satisfaction. By empowering employees to take ownership of their work, and by creating a culture of innovation and continuous improvement, Shell was able to enhance innovation and drive new business growth.

As a result of these benefits, Shell was able to improve its overall business performance, including revenue growth, profitability, and market share. Overall, the successful implementation of change by Shell enabled the company to stay ahead of the curve and remain a leader in the industry.

Final Words

The change management initiative by Shell serves as an excellent example of how a large and complex organization can successfully adapt to changing market conditions and stay ahead of the curve. By adopting a flexible and adaptable approach, and by empowering employees to take ownership of their work, Shell was able to transform its culture and operations, delivering significant benefits to customers, employees, and shareholders.

The success of Shell’s change management initiative highlights the importance of effective leadership, communication, and collaboration in driving change. It also underscores the need for organizations to be proactive in anticipating and responding to external and internal factors that may impact their business.

In today’s rapidly changing business environment, the ability to adapt and innovate is essential for success. By embracing change management principles and practices, organizations can position themselves for growth and long-term success. The case study of Shell’s change management initiative provides valuable insights and lessons for organizations seeking to navigate the challenges and opportunities of the modern business landscape.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

Cadbury Crisis Management Case Study: Preserving Trust in Times of Crisis

Switch Change Management Model- Explained with Examples

What are 06 Stages of Behaviour Change

- Change Management in an Organization Words: 2787

- Organizational Change Management Essay Words: 1962

- Change Management Capabilities at Ryno Words: 1260

- Management in a Time of Change in the Global Context Words: 1931

- Nonprofit Organizations’ Change Management Words: 1383

- Organizational Change Management for Relocation Words: 3174

- Change Management: Vodafone Qatar Words: 4275

- The Interplay Between Leadership Styles and Organizational Change Management Words: 2207

- Model Management of Organizational Change Words: 1298

- Change Management and Management of Organizational Behavior Words: 1910

- Transformational Change: Case Study Words: 3961

- Change Management in Nursing Words: 684

- Evaluating Learning Outcomes: Change Management Words: 1719

- Change Management at Nokia Corporation Words: 1580

- Leadership and Change Management in Apple Company Words: 1377

- Organizational Change: Qatargas Case Study Words: 4117

- Dupont Case Study: Organizational Management Words: 1186

- Managing Organizational Change and Organizational Development Words: 702

- Woolworths, Australia: Organizational Change Management Words: 654

- Change Management Simulation and Lessons Learnt Words: 1425

- Change and Conflict Management in Nursing Words: 821

- Change Management Theories and Law Enforcement Change Management Words: 2241

Management of Change: Shell Case Study

Shell change management case study: introduction.

This assignment is a case study on organizational change and change management. The case study is based on a Canadian based organization known as Shell Canada. This organization is one of the many organizations which have undergone through major changes in the recent past. The change which has taken place in this organization is in the form of restructuring. This discussion starts with a brief overview of an organization and the theoretical perspectives to organizational change.

The discussion thenoes on to highlight the changes in the organization in terms of internal and external pressures of the changes, various types of change, the management’s role in the change process, resistance to the change process, the consequences of the change process and flow chart for the change process.

Shell Change Management Case Study: Discussion

Definition of an organization.

An organization is a group of people who work together with coordinated efforts to achieve certain objectives or goals. Organizational goals and objectives are of various categories and it is this variation of goals and objectives which classify organizations into three main categories namely profit-making, service-based and social responsibility based organizations (Murray, Poole, & Jones, 2006. pp.45-69). The study of organizations is made possible by the use of organizational theoretical models or approaches.

These theoretical models are mainly used to explain organizations in terms of structure and culture. Organizational culture refers to shared beliefs, values, norms and practices which characterize an organization. Organizational structure refers to how the organization is structured, how power and authority to make decisions are distributed along the structure of the organization and who takes what directives or instructions from whom and when (Robbins, 1996).

Theoretical Perspectives to Organizational Change

There are various perspectives of looking at organizational change in terms of how it occurs, why it occurs and how to address the issues of resistance to change in organizations. The perspectives take the form of theories or models. These two terms (theories and models) are used interchangeably although they do not mean the same. While theory is used to imply abstract insights to a subject, models are used to connote a particular set of procedures, methods or plans which may be used to undertake a particular action (Kezar, 2001).

In organizational context, many scholars use the term models instead of theories. Even when the term theory is used, it is used as model to lead organizations in their actions (Kezar, 2001). There are two main theoretical models of explaining and conceptualizing organizational change namely the Evolutionary and the Teleological models. The major distinction between the two is the manner in which they address the issue of determinism in the change process.

The Evolutionary model seems to embrace the idea of determinism in explaining organizational change while the Teleological perspective tends to de-emphasize it. However, both models tend to conceptualize organizational change as a liner and rational process which occur due to forces internal and external to organizations. Each of the models has got several other approaches of explaining and conceptualizing organizational change (Kezar, 2001).

Evolutionary model of organizational change

The major assumption in this model is that change in organizations depends on the situations and environments in which organizations operate. This model has its origin from the natural selection theory which was adopted in organizational change with the philosophy that change is always happening naturally and no force can effectively prevent it from happening (Towers, 2008).

Later on, there emerged the Resource Dependence approach which purports that organizations can never be self-sustaining but they rely on external environment and resources, and therefore managers in organizations have to come up with adaptive systems to enable them to cope and survive in the ever-changing internal and external organizational environments (Towers, 2008).

The Evolutionary model, in general, tends to emphasize on determinism, that is, organizations operate in an unpredictable socio-cultural, economic and political environments which automatically dictate how they should operate.

According to the model, change occurs in a liner manner but may also occur spontaneously as the environment may dictate and therefore managers cannot anticipate it. Managers should, therefore, embrace change, either from internal or external forces and develop adaptive mechanisms. Employees are supposed to automatically understand and embrace organizational change without questioning (Towers, 2008).

Teleological model

This model is also known as scientific management or planned change. The major assumption of this model is that change in organizations occurs as a result of concerted efforts by organizational leaders who see the necessity of change, plan and execute it for the benefit of organizations. This model is perhaps the most common in the literature of organizational change (Keys & Fulmer, 1998).

Approaches which lie under this category include Organizational Development, Strategic Planning and Organizational Learning. The Organizational Development approach is very popular in this category and it involves managers doing an analysis of their organizations to know the problems they are facing and then coming up with solutions to these problems as well as strategies of how to improve organizational productivity using minimum resources (Keys & Fulmer, 1998).

The change process and management

The change process can be contextualized using Kurt Lewin’s approach to change management which falls under the category of the teleological model of change. Lewin came up with what he called three-stage theory which involves three stages or steps namely unfreezing, changing and freezing (Cummings & Worley, 2008). In the first step (unfreezing), the organization is supposed to be motivated and prepared for the change.

The management must engage the employees and create a state of discontentment with the prevailing conditions in the organization. While doing this, the management should also ensure that they set out deadlines for themselves to come up with a new dispensation of doing things (Cummings & Worley, 2008). This stage is about doing a cost-benefit analysis about the proposed change and weighing whether the pros of the change outweigh the cons, then creating the necessary motivation for the change.

This stage is, therefore, the preparatory stage and is very crucial because it determines the success of the change if effected. When employees are highly motivated to change, the resistance to change is minimized and vice versa (Cummings & Worley, 2008). The next stage is the change stage which is also known as the transition stage and involves implementing the change. This is the hardest stage in change implementation because employees are always reluctant to move out of their comfort zones despite any motivation.

During this stage, therefore, employees need to be guided and encouraged to undertake the change. To realize a smooth sailing through this stage, employees need to be given the necessary training for them to acquire the knowledge and skills for navigating successfully through the transition stage (Cummings & Worley, 2008). The final stage is the freezing stage, which is also known as a refreezing stage. During this stage, the organization has successfully sailed through the change process and is now leaving in a new dispensation.

There is, therefore, the need of creating a new culture in the organization which is in line with the new organizational dispensation (Cummings & Worley, 2008). This approach has however been criticized for being very simplistic especially in the way it assumes that people can be taken through these stages without difficulties. Its critics argue that the approach is a bit mechanical and unrealistic.

But despite the criticism, the approach remains common in the world of organizational change even today, especially in the preparation of employees for change mainly through doing appraisals and evaluation of organizational activities and their effectiveness (Cummings & Worley, 2008).

These practices of appraising and evaluating organizational activities and programs can be explained as a contemporary Lewis’ approach to organizational change, which may be described by many as a participatory approach to organizational change (Cummings & Worley, 2008).

Shell Canada

The organization of my choice is Shell Canada. This is a branch of the Shell group of companies which are spread all over the world with a history of over 93 years in business and with its headquarters in London. The organization underwent some major organizational changes at the wake of the millennium, that is, in 2000 (Grant, 2002).

The changes witnessed in the organization

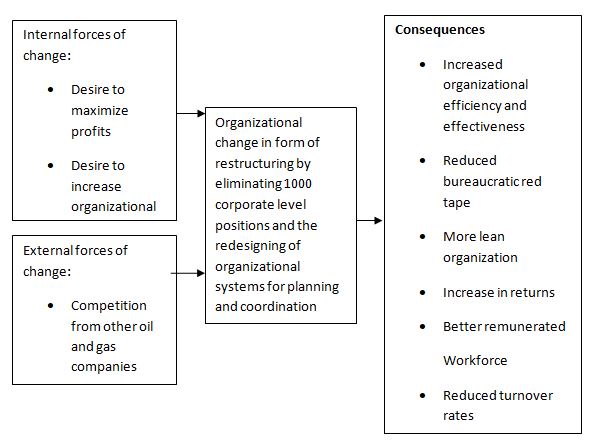

The changes basically entailed major restructuring of the organization to make it more productive, especially due to increasing competition from other oil and gas producing companies like B P. The restructuring saw some 1000 positions scrapped as well as the redesigning of the coordination and organizational control systems to make them more sensitive to, and respond adequately to competition.

The elimination of the 1000 corporate positions in the organization led to the decentralization of power to make decisions to divisions (shell Canada included). This also made the top leadership of the Canada division make decisions with ease and in a timely and efficient manner (Grant, 2002).

Internal and external pressures of the change

Organizational change may emanate either from internal or external environment of an organization. Internal environment constitutes things like profit maximization, expansion, bankruptcy, change of objectives, adoption of new technology as well as mergers and acquisitions. External environment constitutes the things which are beyond the control of the organization and may include things like competition, increased cost of production, political and social risks as well as rates of inflation.

One of the internal factors which necessitated the restructuring of Shell is the desire to maximize profits. This was to be achieved mainly through the elimination of 1000 corporate positions and the decentralization of power to make organizational decisions to divisional leaders and managers, with a view of doing away with the bureaucratic red tape which hindered organizational efficiency and effectiveness as well as the maximization of profits by the organization (Grant, 2002).

One external pressure which precipitated a change in Shell Company was competition from other oil and gas producing companies like BP, which were entering the market with a storm and promising customers more customer friendly goods and services at very friendly prices.

This made the organization see the need of restructuring to streamline its systems to allow for proper competition with its peers. The increase in the number of oil and gas producing companies also broke the monotony of Shell in the field of oil and gas, thus prompting the organizational changes (Grant, 2002).

Various Types of Change

According to the national academy for academic leadership, first-order change is a change which is reversible. This type of change entails doing more or less the same things which an organization has been doing with little variations (National academy for academic leadership, 2011). This type of change is usually not transformational and aims at restoring equilibrium in the systems of an organization or retaining the status quo.

First order changes, therefore, happen within the existing organizational structure and does not entail any new form of learning (National academy for academic leadership, 2011). Second order change is a change which is irreversible.

This type of change involves doing fundamentally new things within an organization; either as a result of internal or external pressure. This type of change is usually transformational and thus entails the learning of new concepts as well as the adoption of new approaches to organizational functions, processes, and procedures (National academy for academic leadership, 2011).

Management’s Role in the Change Process

Management is about planning, coordinating and controlling organizational resources so as to facilitate the achievement of organizational goals and objectives in an efficient and effective manner. The nature of management therefore only allows for the top leadership of an organization to act as the drivers of the organization in a way which facilitates the organization to achieve its goals and objectives, including the management of organizational change.

The role of the management of Shell Company in the change process was basically to plan and execute the change in a manner which was efficient and cost-effective so as to minimize resistance while maximizing the success of the change. The Shell management was actively involved in brainstorming and evaluation of the organizational functions and processes as well as doing an environmental scan to understand the market trends so as to inform the change process (Grant, 2002).

The management was able to analyze the market and thus saw the need for the radical departure from bureaucratic red tape and create a more lean organization, which was highly decentralized so as to maximize on organizational efficiency and effectiveness (Grant, 2002).

Resistance to the Change Process

Due to the proper calculations and planning of the change process by the management, there was no resistance to the change. This was basically because the restructuring did not require the consultation of the corporate level employees who were affected by the change. The reason why the management did not seek the views of the targeted employees in the restructuring was that it was obvious that they would resist.

The Consequences of the Change Process

One consequence of the changes in Shell was the remarkable reduction of head office costs following the elimination of the 1000 corporate-level jobs, most of whom had offices in London. Following the changes also were increased organizational efficiency as well as an increase in the number of returns due to the huge savings on management and running costs.

The employees’ remuneration was also increased marginally thus leading to low turnover rates in the organization. The organization also increased its competitive advantage at the global market of oil and gas products (Grant, 2002).

Cummings, T. G. & Worley, C. G. (2008). Organization development & change. Farmington, MI: Cengage Learning. Print.

Grant, R. M. (2002). ‘Organizational Restructuring within the Royal Dutch/Shell Group’. Web.

Keys, B., & Fulmer, R.M. (1998). Executive development and organizational learning for global business . New York, NY: Routledge. Print.

Kezar, A. J. (2001). Understanding and facilitating organizational change in the 21st century: recent research and conceptualizations, Volume 28, Issue 4 . New York, NY: Jossey-Bass. Print.

Murray, P., Poole, D and Jones, G. (2006). Contemporary issues in Management and Organizational Behavior . Farmington Hills, MI: Cengage Learning. pp.45-69.

National academy for academic leadership. (2011). ‘Leadership & Institutional Change’. Web.

Robbins, S. P. (1996). Organizational behavior: concepts, controversies, applications , (7th Ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Towers, I. (2008). Organizational change: processes, contexts and perspectives . Ottawa, ON K1A 0N4: Library and Archives Canada. Print.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, April 27). Management of Change: Shell Case Study. https://studycorgi.com/shell-canada-company-change-management/

"Management of Change: Shell Case Study." StudyCorgi , 27 Apr. 2020, studycorgi.com/shell-canada-company-change-management/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) 'Management of Change: Shell Case Study'. 27 April.

1. StudyCorgi . "Management of Change: Shell Case Study." April 27, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/shell-canada-company-change-management/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Management of Change: Shell Case Study." April 27, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/shell-canada-company-change-management/.

StudyCorgi . 2020. "Management of Change: Shell Case Study." April 27, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/shell-canada-company-change-management/.

This paper, “Management of Change: Shell Case Study”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: February 21, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Managing IT transformation on a global scale: An interview with Shell CIO Alan Matula

Over the last decade, Shell has been undergoing an IT transformation that is remarkable for the scope of change it is seeking in one of the world’s largest and most complex organizations—one with 25 business portfolios and operations across more than 100 nations. The transformation is defined by four phases, says Alan Matula, executive vice president and group CIO.

The first was about going back to basics—allowing Shell’s IT leaders to better align IT with the business units by stabilizing operations, establishing project discipline, and tracking costs, people, and assets. Matula says that this solid foundation is essential to any successful IT transformation.

In the second phase, the targets were costs and complexity. Shell rationalized and consolidated infrastructure, substantially reduced the number of business applications, improved procurement procedures, and aggressively offshored. It also strengthened governance by recognizing that a real dialogue with the businesses was needed and recruited high-grade talent to conduct it.

Investments in the future formed the third phase: innovation, functional improvements, and business-driven multiyear investment programs to help the businesses meet their targets. Shell implemented strategic sourcing to consolidate hundreds of suppliers, leaving just 11 key partners with whom it outsourced selected functions. Matula says the change in direction allowed Shell to work with suppliers, “doing things that are not only good for Shell but that also are innovative in the marketplace and help the industry.”

Shell is now geared up for the harvest-and-sustain phase, to ensure that the benefits of its IT investment are realized. “IT is more important and intense than ever before and that requires an ongoing effort to transform IT and improve its agility, to make the business more productive and competitive,” Matula told McKinsey’s Leon de Looff in a recent interview (in The Hague) covering Shell’s IT transformation, challenges, and the many lessons learned so far.

The Quarterly : Shell has been in the midst of an IT transformation for several years now. Can you tell us about how it started and about the approach you took?

Four steps to a successful IT transformation

Put transformation on a solid footing by stabilizing IT operations, enforcing project discipline, and tracking costs, people, and assets.

Take a phased approach—lock in IT efficiencies and reduce complexity early on; then invest in improvements to help businesses meet their goals.

Get business unit support for major change by maintaining precise accountability for the delivery of benefits and by monitoring progress frequently.

Select or recruit top IT talent for the interface in concert with business units to help build the trust needed to sustain transformation.

Alan Matula: It was a phased approach that started in the early 2000s with a drive to get back to basics. I was very fortunate to be a part of that effort from the beginning, continuing over the four phases, since I held positions as a business CIO and now as group CIO. The phases addressed specific goals: back to basics, rationalization and consolidation, investing in the future, and harvest and sustain. (For more, see sidebar “Four steps to a successful IT transformation.”)

The Quarterly : What do you need to launch an IT transformation at this scale?

Alan Matula: You have to start out with a solid foundation that builds credibility with the business. That includes stabilizing operations, implementing project discipline, and tracking costs, assets, and people. If you don’t have the foundation, then don’t even start.

Alan Matula biography

Born November 11, 1960

2 daughters

Graduated with a BS in quantitative business analysis from Indiana University

Earned an Executive MBA from Houston Baptist University

Royal Dutch Shell

CIO (2006-present)

CIO, Shell Downstream (2003–06)

CIO, Shell Chemicals (1996–2003)

Corporate planning, Shell US (1992–96)

Various information technology positions, Shell Oil (1982–92)

Nonexecutive board member of Airbiquity

Enjoys sports, outside recreation, and spending time with friends

The Quarterly : What did Shell do to be sure that the businesses were aligned on this?

Alan Matula: Right from the start, we deliberately put “business at the center” of what we do. But the key is that we have been able to strike a balance between an IT foundation that is standard across business units, while differentiating and catering to specific business needs—areas like high-performance computing for our exploration businesses.

The Quarterly : Did the move back to basics stir up any resistance from the businesses? And if so, how did you deal with that?

Alan Matula: We made the application portfolio transparent, showing the businesses the real cost and the complexity of what they had. They figured out pretty quickly that it didn’t fit the changing business models and competitive conditions in the industry, or the globalization agenda the company had set for them.

The Quarterly : It must have been complicated given your historical legacy?

Alan Matula: You have to remember, we came from a nation-based operating model that was successful for many years. We’re turning that model on its head. So you basically go nation by nation, region by region, and replace a lot of the legacy assets and start to initiate your standardization agenda to attack costs and complexity.

The Quarterly : CIOs debate whether IT should follow business change or lead it—in your case, for example, by furthering Shell’s globalization through IT standardization. What is your view?

Alan Matula: I see it somewhat differently. IT is like cement to the standardization activities. If you don’t cement changes with IT, then over time they will erode and revert back. IT provides the transparency that you need for driving standardization in a large, diversified corporation like Shell.

The Quarterly : You’re now a few years into the campaign. What has changed?

Alan Matula: We went from hundreds of national enterprise resource programs to about six to eight core platforms that do the heavy lifting in terms of business transactional capability. For example, we now have one HR system, one health system, and three or four big application landscapes per business sector.

The Quarterly : And what about the applications that have to be tailored for business needs?

Alan Matula: In addition to the core platforms, we divided the business into portfolios around key sectors such as upstream, downstream, and corporate functions. But to really align IT directly to the business strategy, you need to go one layer deeper. So for downstream operations, that means retailing and manufacturing; for upstream, it’s exploration and production. In total, we have 25 business portfolios.

The Quarterly : Are these managed differently?

Alan Matula: That’s where we’ve put our key talent in terms of IT capability. Because of their business domain knowledge, these are the people who really get a seat at the table with business leadership teams. They understand the business strategies and can create the differentiating IT on top of the business transactional layer. A lot of what we consider competitively differentiating is kept in house. Even though you read a lot about outsourcing, the key differentiating systems are still kept and managed specifically within Shell.

The Quarterly : Stepping back a bit, how does a CIO build the business case—one that demonstrates the benefits of a broad transformation that involves major investments and a lot of change?

Alan Matula: We’ve learned for sure that when you make the business case, you have to ensure accountability for delivery of the benefits. You need the names of the people who are going to extract the gains. Then you need to track benefits on an ongoing basis. We’re piloting quarterly monitoring where you look at an applications portfolio and examine where benefits are materializing and where they aren’t.

Beyond that, you have to have the right people at the business interface. They are invaluable. You will not find a CIO who doesn’t struggle with finding talent for the business interface. We’ve invested in our IT people through a learning program delivered by a business partner program.

The Quarterly : What role is IT playing in Shell’s innovation efforts?

Alan Matula: We review each of our major portfolios every 18 to 24 months, focusing on the key technologies needed to stay in the game as well as what is needed for competitive differentiation. We have done some very innovative things—in telematics, for example, using wireless technology to monitor auto fuel consumption and efficiency. But the key to innovation is having a real dialogue at the business-portfolio level to understand where technology is important. That means a change of mind-set and skills, moving from a focus on the basic infrastructure of business administration to a position as close to the business leaders’ needs as possible.

The Quarterly : What was the reasoning behind consolidating suppliers and outsourcing? How did your thinking evolve?

Alan Matula: We actually tested outsourcing early in phase two, but we backed away from it because we didn’t want to outsource IT problems we hadn’t fixed. Once we were comfortable with our progress, we started the third phase. We spent almost a year bringing in suppliers—10 or 15 of them—exploring what was working, what wasn’t, and what needed changing. It was then that we latched onto multisourcing as a model. For example, in infrastructure, we now have three suppliers that are capable of providing services across the board. This provides us with flexibility and agility as we evolve the delivery model to respond to the changing IT market and Shell business needs. We benchmark the suppliers, and we have written contracts that are very flexible.

The Quarterly : Is there an optimum number of suppliers for a company like Shell?

Alan Matula: Things do not stay the same forever. But to give you a sense of our thinking, before we consolidated our infrastructure suppliers, we had about 1,500 different contracts, covering licenses, hardware, and services, with an outsourcing model that was very fragmented. We’re now down to three infrastructure suppliers, and these are an integral part of what we call our ecosystem of key suppliers.

The Quarterly : Was there a driving philosophy behind the new outsourcing model and the new ways of working with suppliers?

Alan Matula: We started with the idea that we wanted 70 percent of our spending to be external. Of that, we wanted 80 percent to be focused on the top 11 suppliers. We put those 11 into three groups: First, there are the foundation suppliers, those in which we make long-term bets—Cisco, Microsoft, Oracle, and SAP. Then there’s the infrastructure group, with three bundles—AT&T, HP, and T-Systems—for networks, end-user computing, and hosting of storage, respectively. And finally we have four application services suppliers—Accenture, IBM, Logica, and Wipro. What we’re doing differently is bringing all 11 of them together to work as a collective.

The Quarterly : Tell us more about that last point.

Alan Matula: About two years ago, we began meeting with the ecosystem suppliers every quarter. We started out slowly, defining golden rules and how we operate, with the ambition of actually doing things together that not only are good for Shell but that also are innovative in the marketplace and help the industry.

The Quarterly : What kinds of innovation?

Alan Matula: The boundaries between the traditional suppliers are blurring. Some traditional hardware suppliers are going into software and vice versa. Others are getting into the data center business. As we started to give our top 11 suppliers some big challenges, that gave rise to some innovative approaches. You’re starting to see all suppliers wanting to play differently by collaborating to improve the overall delivery to Shell. I think it’s going to be an exciting time as we continue to push current industry norms to drive greater degrees of collaboration, change, and innovation.

The Quarterly : You think of IT in terms of phases. What is the next frontier for IT transformation at Shell?

Alan Matula: The next phase in our transformation will be a shift to harvesting the benefits from the assets we have put in place—a new system for HR should last 15 years. So the goal now is to leverage these assets to improve business performance. That’s a different model of change. It forces us to be more intimate with the business, actually putting business operations and IT operations side by side. In the project mode of recent years, you could keep some distance as you restructured, but in the harvest-and-sustain mode, you have to work to optimize the business processes, with IT delivering business performance improvements. The structural approach will be different, and that’s what we’re now exploring.

The Quarterly : Going forward, since you’re trying to capture benefits outside IT, you need a different steering mechanism and metrics beyond just reducing IT unit costs, right?

Alan Matula: The pressure to reduce unit costs will never go away in IT. But when you get to harvest and sustain, it’s about smarter demand management, to make sure you are using only the IT that you require and are doing only the IT projects that you need to do. It’s also about a different set of metrics on the business side, and the ultimate art of this is talking to the businesses in their own terminology, to show exactly where IT contributes to their goals. We’re testing a couple of portfolios to see if we can do this. It’s something that every CIO would love to be able to do.

The Quarterly : Are you doing your own IT research to develop innovations for the business?

Alan Matula: At the beginning of each year, we carve out key technology areas or domains that we want to mine—things like sensors, high-performance computing, new ways of working. We work with the external providers as well as internally searching for areas where we can make disruptive, differentiating strikes. In terms of structure, we have put all IT technology research into a projects-and-technology organization with a chief technologist whose job is to look for those technology strikes that add the most business value. We want to send the message that the CTO is a business partner at a very different level from standard IT. The projects-and-technology organization is split from the rest of the IT function, and there’s a cut line between the big technology plays and supporting staff—20 percent of the total staff—versus the more incremental activities that remain in the traditional IT line, or 80 percent of the staff.

The Quarterly : You have recently changed how you govern IT, with the business unit CIOs now reporting to the IT function and no longer to the business heads. Is this the optimal model?

Alan Matula: It’s really about maturity. In the early phases, there was no way you could consolidate IT under one function. We needed to build credibility with the businesses, and they needed to take ownership of their project portfolios. In today’s phases, maturity starts to blossom. The CIOs get more and more credibility. As long as they still have that seat at the business table, are heavily engaged, and serve on business forums and leadership teams, then that is what is really important. If that starts eroding, then we’ll go back to the previous model.

The Quarterly : The change in governance more or less coincided with the start of the recession?

Alan Matula: That’s right. I now have more levers to pull when it comes to costs and agility. The new governance model has allowed us to move faster and make decisions without working across different business lines to get everyone to agree. Furthermore, we can move IT resources around easier and more quickly.

The Quarterly : In the financial crisis, some CIOs have focused primarily on cutting IT spending, while others have focused on IT’s important role in cutting business costs. What has been your experience?

Alan Matula: You have to do both. We have, for example, made use of the network for telephone calls, and we have transformation projects in place that use technology so we can work virtually. But it’s a balance. You need to keep driving down pure IT costs on a unit basis while also providing technology that drives business costs down. Of course, it’s always hard to tell that latter story, since it’s often difficult to determine the full cost of a business process.

The Quarterly : While you have pushed standardization and sourcing to the maximum level, is it still possible to squeeze more costs and inefficiencies out of IT operations?

Alan Matula: There are new models emerging, based on cloud computing and software as a service, that are going to have an impact. Beyond that, we have to be a lot more selective about what projects we do, and most of all we have to work for continuous improvement to get the full potential from our IT assets.

The Quarterly : What are the lessons you have learned from this transformation? What might you have done differently and what would you tell other CIOs?

Alan Matula: IT is more important and intense to the enterprise than ever before, and that essentially requires an ongoing effort to transform IT; there is always another phase. To support that mental model, the first thing is to never lose the perspective that you’re here to make the business more productive and more competitive. Our catchphrase, “business at the center,” keeps us grounded. Our position today is a reflection of the tight integration that we have with the business, combined with the efforts of key support functions like HR, finance, and procurement.

A second thing is that you’re only as good as the talent that you have. For instance, in the robust sourcing of infrastructure and applications we have put in place, the people at the interface are very important. They manage the critical supplier relationships with CEOs and top executives at these firms, and they have the technical know-how to help guide the suppliers.

Finally, if you don’t have the basics right, you won’t have any credibility. It only takes one bad “go live” on a project or a flaw in your basic delivery capabilities to set you back very quickly.

Leon de Looff is a principal in McKinsey’s Amsterdam office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Time to raise the CIO’s game

It architecture: cutting costs and complexity, where it infrastructure and business strategy meet.

Cambridge Core purchasing will be unavailable Sunday 22/09/2024 08:00BST – 18:00BST, due to planned maintenance. We apologise for any inconvenience. Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Business Ethics Quarterly

- > Volume 14 Issue 4

- > The Evolution of Shell’s Stakeholder Approach: A Case...

Article contents

The evolution of shell’s stakeholder approach: a case study.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 January 2015

Shell’s efforts to integrate the stakeholder management approach into its business practice worldwide involved the gradual development of a long-term, comprehensive strategy. This paper draws on stakeholder management theory and Shell’s experience to identify critical factors that contribute to the process of institutionalizing the principle of stakeholder management in a global company. A key lesson to be drawn from the case is the necessity of ensuring that the process allows for continuous learning, adaptation, and refinement.

Access options

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 14, Issue 4

- Jane Wei-Skillern

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.5840/beq200414443

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- October 1999

- HBS Case Collection

Royal Dutch/Shell in Transition (A)

- Format: Print

- | Pages: 31

About The Author

Lynn S. Paine

More from the author.

- August 19, 2024

- Harvard Business Review Digital Articles

The Business Roundtable’s Stakeholder Pledge, Five Years Later

- Faculty Research

Climate Governance at Linde plc (B)

- June 2024 (Revised June 2024)

Climate Governance at Linde plc (A)

- The Business Roundtable’s Stakeholder Pledge, Five Years Later By: Lynn S. Paine

- Climate Governance at Linde plc (B) By: Lynn S. Paine, Suraj Srinivasan, Emilie Billaud and Vincent Marie Dessain

- Climate Governance at Linde plc (A) By: Lynn S. Paine, Suraj Srinivasan, Emilie Billaud and Vincent Dessain

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Case study Reorganizing the Royal Dutch Shell Group

Related Papers

Shell's overbooking of oil and gas reserves provoked one of the biggest corporate scandals to occur in Europe in recent years. This article has three themes: 1. The Origins of the Scandal: the shortage of oil reserves, weak internal controls, the dual company structure and the closed corporate culture. 2. The Impact of the Crisis: the resignations of top managers, the fines imposed by the regulators, the fall of the share price and the decline in employee morale. 3. The Remedial Action Required: to rebuild Shell's reputation and to restore the trust of the investors, customers and the general public. At the root of the problem is the central question " How did Sir Philip Watts and his colleagues arrive at a situation where they overstated the company's proven reserves of oil and gas by 30 per cent? " Royal Dutch/Shell is a leading British and Dutch company with an enviable reputation and a proud history. How could this have happened? Through analysing the scandal at Shell, the article probes into the fundamental causes of the present crisis in corporate governance.

Frans A J Van Den Bosch

Using the upper echelons perspective together with corporate governance and strategic renewal literature, this paper investigates how top managers’ corporate governance orientation influences a firm’s strategic renewal trajectories over time. Through both a qualitative analysis (1907-2004) and a quantitative analysis (1959-2004), we investigate this under-researched question within the context of a large incumbent firm: Royal Dutch Shell plc. Our results

Journal of Management Studies

Henk Volberda

Organization & Environment

Simone Pulver

Frans Paul van der Putten

European Management Journal

Amol Thorat

Colin Higgins

Hisham Yaacob

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Change Management: Results With and Without. A Case Study.

22 February 2022 Same change, same time, two different approaches, widely different outcomes. Article written by Nelly Tire and Vincent Piedboeuf

Prosci Europe's case studies offer practical insights for organisations wishing to make changes that stick.

Executive Summary

Why should I read? To get a real-life example of what can happen without a structured approach to managing the change. We uncover the difference in outcome between two organisations seeking to deploy the same technological solution to a recurrent and common issue in the personal care service sector.

Highlights:

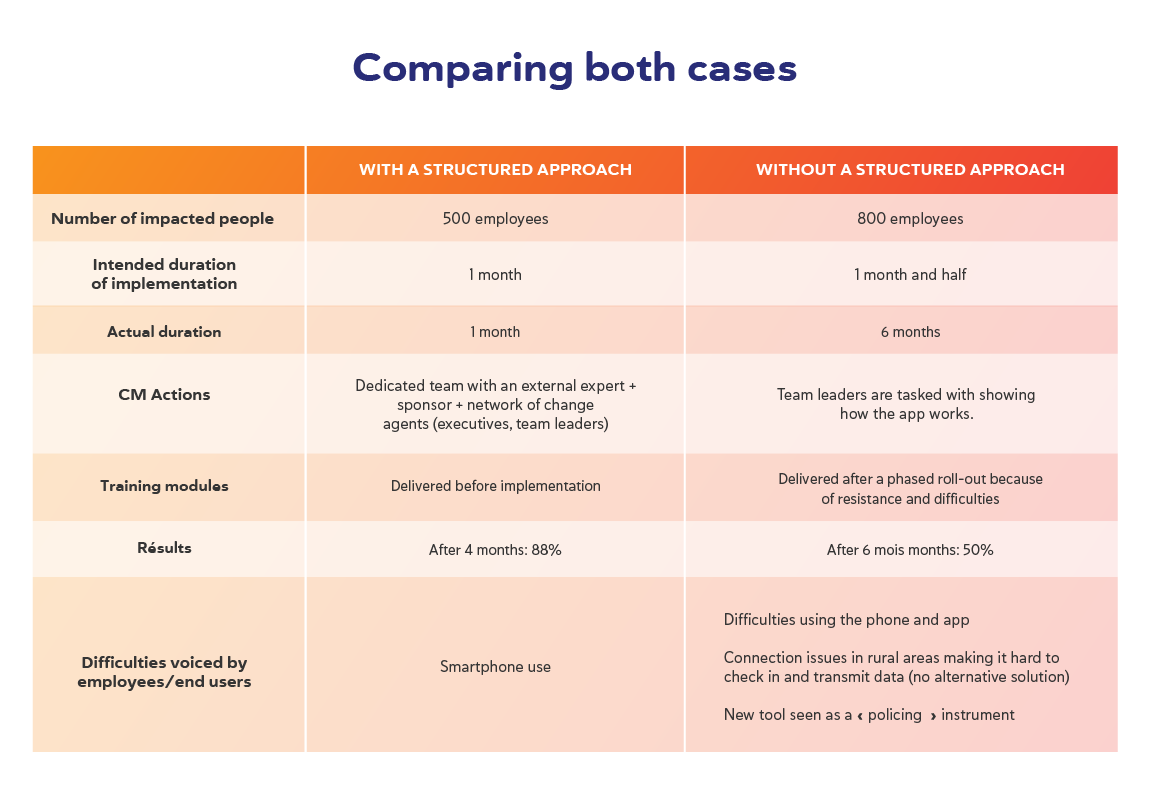

- In one case, the implementation phase proved much longer than expected. Only half of the staff was or stayed on board. The gulf between the target set and the number of people proficiently using the change kept widening every day.

- The second case shows adoption and utilisation rates close to 88%. A clear CM plan with actionable strategies delivered expected results on time.

- For a complete overview of what a successful CM plan looks like, please see Keys to application.

Background

Year – 2021.

Sector – Personal Care Services.

Who – Two non-profit organisations offering social services such as childcare, home nursing, special assistance to vulnerable people, heavy-duty housework, etc.

What – In a nutshell, outdated paper-based management and monitoring systems generate errors, poor responsiveness, and late payments while also causing the organisations and the sector to miss out on new opportunities. The new "Mobile Teleprocessing System" attempts to leverage technology to optimise the provision of existing and future services.

Type of change – See below.

The challenge (why the change?)

Baseline. Managing and controlling provided services happens through a two-fold mechanism of phone check-in used by staff members in the home of users (elderly, physically- challenged people, etc.) and paper-form shift sheets subsequently signed by users (date of the month, number of hours).

Internal reasons to change. Both entities sought to provide practical solutions to recurrent problems reported by frontline employees/account services. Climbing on the train of digitisation was also expected to raise the sector's attractiveness. More specifically, both associations faced the following issues:

- The excessive shift sheet volume led to repeated data processing and validation delays, pushing back invoicing and wage payments to 15 days the following month.

- Frontline employees (caretakers) found it challenging to check-in using the user's phone landline .

- There were problems managing shift sheets/forms , sometimes signed by disabled or vulnerable people (users), by staff members themselves, when not simply lost.

External reasons to change. The availability of game-changing technological solutions, which could also respond to concerns related to funding, turned the change into a pressing issue. The mix of specific requirements and opportunities included:

- system loopholes – the phone clocking in/out mechanism could only be used for some services.

- technological developments and new apps designed to smooth out the problems of bureaucracy and speed up data exchange.

- requests from funders to better control the use of resources allocated to the associations and allow real-time communication with home care services.

The solution

This set of external and internal drivers led to "Mobile Teleprocessing" project. The overarching element of the action plan was the switch from the aforementioned "point system" (fixed phone system and shift sheets) to the use of a particular app running on a professional smartphone and connected in real-time with the all-in-one software for planning/accountancy . This advanced solution could also help manage instant alerts in case of a change in the internal working schedule. Sending off invoices would be just one click away. Other apps responding to specific health and care issues were also under consideration.

Expected benefits ranged from shortening processing times and reducing errors when logging data to improving communication with frontline employees and funders.

Keys to application – 1st case

Highlight: The first organisation implemented the solution within one month, impacting 500 employees. The plan was based upon Prosci's best practices and ADKAR model for individual change. Here is an overview of the main items:

a. Sponsorship, the face of change.

Active and visible sponsorship throughout the whole duration of the project is the number-one success factor of any change initiative. In this case, the Director-General was designated as the primary sponsor. Beyond its involvement in the early phases, he was provided with data fresh from the field to remind people of the rules and communicate results.

b. Bringing in Change Management resources.

The association allocated resources to CM, setting up a dedicated team with a change practitioner and a network of change agents.

c. Evaluating impact.

The organisation identified the groups impacted by the change (frontline employees, team leaders, accounting services) to prepare targeted training sessions.

d. Creating Awareness and Desire.

Before moving any further along the change journey, the association communicated extensively around the project and the strategic reasons underpinning it. They proceeded to:

- Convene and conduct a meeting to introduce the project and CM plan to team leaders and super-users.

- Get executives and team leaders actively involved with CM and fully committed to the process.

- Circulate a promotional film featuring the change and its rationale, along with footage of an employee using the new tool.

- Disseminating information on the intranet to communicate with frontline staff (caretakers operating in users' homes)

- Send mail communications to present the "Mobile Teleprocessing" project to users and employees.

e. Building Knowledge and Ability.

After completing the impact analysis and conducting preliminary campaigns to raise awareness and desire, the organisation started to prepare the people for the change. They did so by:

- Delivering 21 training sessions to 500 collaborators

- Choosing instructors among expert users

- Designing high-quality training materials, with a strong focus on user-friendliness (practical exercises, quizzes, appropriate evaluation forms, ….)

- Systematically collecting and analysing feedback to improve materials

- Creating FAQs on the intranet

- Uploading Video tutorials on the association website

- Developing memos for teams on specific topics

- At the end of the project, team leaders took over the role of instructors for new employees entering the application.

f. Reinforcing.

To ensure long-lasting results and effective use of the phone and app, the association proceeded to:

- Collect info on clocking in/out processes and the remaining volume of shift sheets.

- Hold a special briefing on results, including a quick review/reminder of the rules (main sponsor).

- Diffuse reminders on the intranet.

- Issue warning letters to people tricking the system by logging incorrect data, holding multiple broken phones, or repeatedly losing them.

Keys to application – 2 nd case

Highlight : The size of the change was even more significant in the second case, impacting about 800 employees. The expected time for completion was one month and a half. But unlike its counterpart, this association did not implement any structured Change Management plan. Team leaders viewed the technical solution as an easy fix.

Items : Team leaders were tasked with demonstrating how the application worked, with the following consequences:

- Employees complained that they received poor guidance and struggled to use the phone or the application.

- Employees perceived the new tool as a "policing instrument."

- The roll-out proved difficult, triggering resistance among staff and causing the training modules to be delivered late.

Results and Takeaways

Clear differences in outcomes show the importance of adopting a structured approach to managing the change. The implementation lasted one month without any significant setback in the first case . Not only did this association meet the deadline. Adoption and utilisation rates after four months were close to 88% . In contrast , implementation suffered from major delays in the second case . While leaders had planned on a one-month and a half roll-out, deployment was only complete after six months. Moreover, adoption and utilisation rates proved grossly insufficient , with a more modest 50%.

If all the above-described Change Management items account for what did go well in the first case, what went wrong in the second one?

A common mistake is to jump right into equipping the people without raising A wareness and creating D esire. This second case study clearly illustrates the consequences of not laying the foundations for the change. Omitting this part led to early resistances, crystallizing without any strategy or capacity to mitigate them. The new system was seen as a policing maneuver of sorts.

Furthermore, there was no attempt to create engaging training materials, leaving team leaders without a clear roadmap or tools to deliver K nowledge. Frontline employees lamented the lack of information or guidance. Issues with the phone connection in some rural regions also meant that employees were unable ( A bility) to use the solution. The new system, first seen as a quick fix, created distrust, and with nothing being done, the snowball effect sat in.

Change cannot be left to chance.

Check out our resources to learn more about Change Management and stay updated!

PROSCI Methodology in action

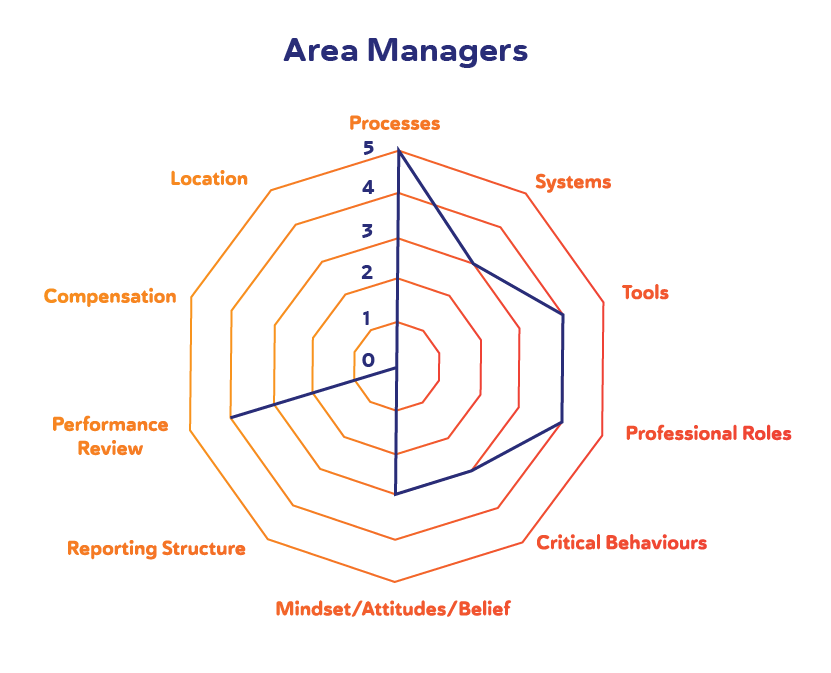

PROSCI's impact analysis provides a very accurate overview of the kind of change involved. The following "radar graphs" identify how the project "Mobile Teleprocessing" affects the three main target groups: Area Managers, Domestic Helpers, and Accounting Services. Most dimensions are self-explanatory [1] , but let's point out that processes , systems , tools, and critical behaviours – heavily emphasised in this case study – refer to:

- the "action steps to achieve a defined outcome" ( processes ), or how the provision of care services will be managed and monitored from this point on.

- the "combination of people and automated application" necessary to meet a set of goals ( systems ), in this case, all stakeholders and what is expected from them in terms of promoting, showcasing, and or being able to use the new "Mobile Teleprocessing" system.

- "an item used for a specific purpose" ( tools ), that is, a professional phone and related app to clock out, report, or log other relevant information.

- "a specific response to a stimulus" ( critical behaviours ), in this example, the consistent and proficient use of the professional phone and app.

[1] PROSCI's change impact model offers a robust framework to define the change along 10 dimensions that may impact people involved. These dimensions or areas typically include Processes (1), Systems (2), Tools (3), Professional Roles (4), Critical Behaviours (5), Mindset/Attitudes/Belief (6), Reporting Structure (7), Performance Review (8), Compensation (9), Location (10). To learn more: https://www.prosci.com/blog/defining-change-impact

After having managed a large number of changes in a wide range of business sectors, Vincent Piedboeuf dedicates his time helping managers to optimise their return on investment through effective integration of the people side in their change projects. He is one of the most active Change Management instructors and certifies hundreds of people in Prosci methodology every year.

Nelly Tire and Vincent Piedboeuf

Do you want to learn more?

Know more about Change Management

Learn the foundations of Change Management

Replay our Webinars

Be in the know.

Join the community to receive the latest articles on Change Management, upcoming events and exclusive newsletter.

We guarantee 100% privacy. Your personal details will not be shared to third party partners.

Join the community to receive the latest thought change management articles, upcoming events and exclusive newsletter

By completing and submitting this form, I authorize the use of my data for being informed of Prosci Europe upcoming events, and gaining access to useful materials tailored to my specific needs. For further information regarding the processing of your personal data or your rights on your personal data, please refer to our Privacy Policy .

Don't ask me anymore

We’ll get back to you soon.