Be thinking

Sapiens ? a critical review.

I much enjoyed Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind . It is a brilliant, thought-provoking odyssey through human history with its huge confident brush strokes painting enormous scenarios across time. It is massively engaging and continuously interesting. The book covers a mind-boggling 13.5 billion years of pre-history and history.

Fascinating but flawed

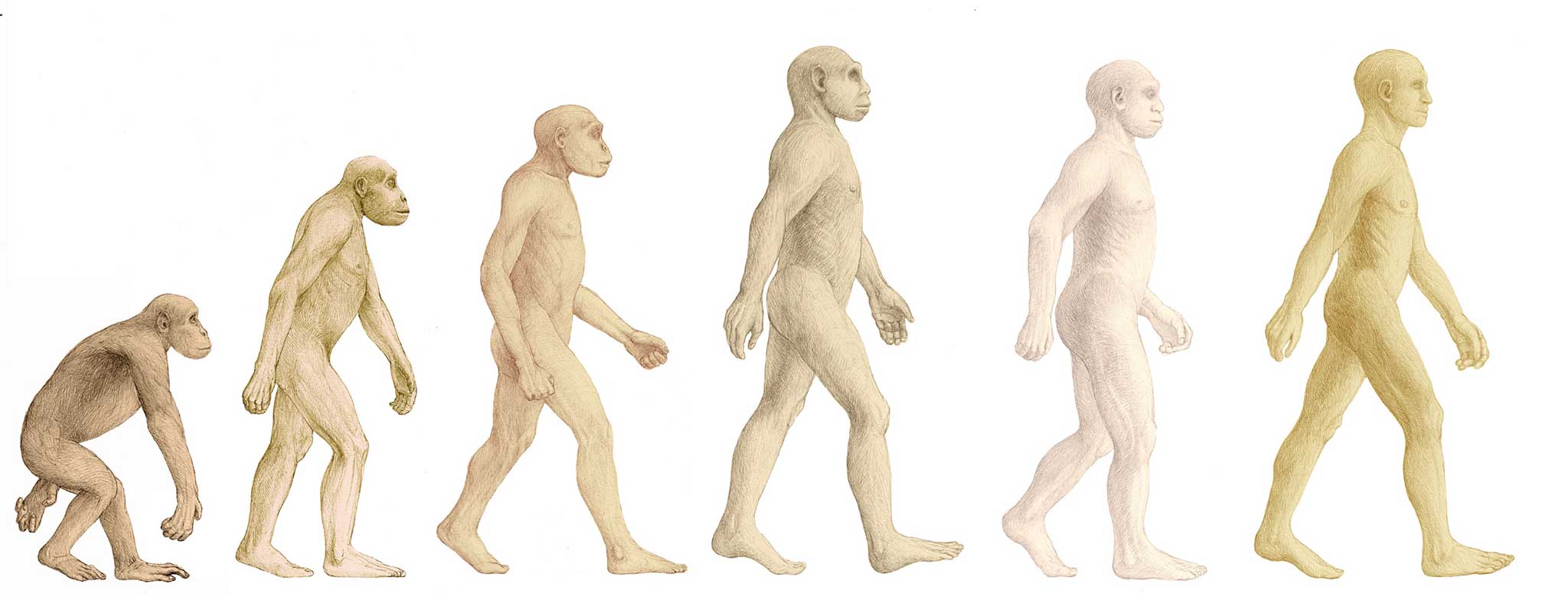

Harari’s pictures of the earliest men and then the foragers and agrarians are fascinating; but he breathlessly rushes on to take us past the agricultural revolution of 10,000 years ago, to the arrival of religion, the scientific revolution, industrialisation, the advent of artificial intelligence and the possible end of humankind. His contention is that Homo sapiens , originally an insignificant animal foraging in Africa has become ‘the terror of the ecosystem’ (p465). There is truth in this, of course, but his picture is very particular. He is best, in my view, on the modern world and his far-sighted analysis of what we are doing to ourselves struck many chords with me.

Harari is a better social scientist than philosopher, logician or historian

Nevertheless, in my opinion the book is also deeply flawed in places and Harari is a much better social scientist than he is philosopher, logician or historian. His critique of modern social ills is very refreshing and objective, his piecing together of the shards of pre-history imaginative and appear to the non-specialist convincing, but his understanding of some historical periods and documents is much less impressive – demonstrably so, in my view.

Misunderstanding the medieval world

Harari is not good on the medieval world, or at least the medieval church. He suggests that ‘premodern’ religion asserted that everything important to know about the world ‘was already known’ (p279) so there was no curiosity or expansion of learning. When does he think this view ceased? He makes it much too late. He gives the (imagined) example of a thirteenth-century peasant asking a priest about spiders and being rebuffed because such knowledge was not in the Bible. It’s hard to know where to begin in saying how wrong a concept this is.

For example, in the thirteenth century the friars, so often depicted as lazy and corrupt, were central to the learning of the universities. Moreover they were, at that time, able to teach independently of diktats from the Church. As a result, there was an exchange of scholarship between national boundaries and demanding standards were set. The Church also set up schools throughout much of Europe, so as more people became literate there was a corresponding increase in debate among the laity as well as among clerics. Huge library collections were amassed by monks who studied both religious and classical texts. Their scriptoria effectively became the research institutes of their day. One surviving example of this is the fascinating library of the Benedictines at San Marco in Florence. Commissioned in 1437, it became the first public library in Europe. This was a huge conceptual breakthrough in the dissemination of knowledge: the ordinary citizens of that great city now had access to the profoundest ideas from the classical period onwards.

And there is Thomas Aquinas. Usually considered to be the most brilliant mind of the thirteenth century, he wrote on ethics, natural law, political theory, Aristotle – the list goes on. Harari forgets to mention him – today, as all know, designated a saint in the Roman Catholic church.

Harari tends to draw too firm a dividing line between the medieval and modern eras

In fact, it was the Church – through Peter Abelard in the twelfth century– that initiated the idea that a single authority was not sufficient for the establishment of knowledge, but that disputation was required to train the mind as well as the lecture for information. This was a breakthrough in thinking that set the pattern of university life for the centuries ahead.

Or what about John of Salisbury (twelfth-century bishop), the greatest social thinker since Augustine, who bequeathed to us the function of the rule of law and the concept that even the monarch is subject to law and may be removed by the people if he breaks it. Following Cicero he rejected dogmatic claims to certainty and asserted instead that ‘probable truth’ was the best we could aim for, which had to be constantly re-evaluated and revised. Harari is wrong therefore, to state that Vespucci (1504) was the first to say ‘we don’t know’ (p321).

So, historically Harari tends to draw too firm a dividing line between the medieval and modern eras (p285). He is good on the more modern period but the divide is manifest enough without overstating the case as he does.

Short-sighted reductionism

His passage about human rights not existing in nature is exactly right, but his treatment of the US Declaration of Independence is surely completely mistaken (p123). To ‘translate’ it as he does into a statement about evolution is like ‘translating’ a rainbow into a mere geometric arc, or better, ‘translating’ a landscape into a map. Of course, neither process is a translation for to do so is an impossibility. They are what they are. The one is an inspiration, the other an analysis. It is not a matter of one being untrue, the other true – for both landscapes and maps are capable of conveying truths of different kinds.

The Declaration is an aspirational statement about the rights that ought to be accorded to each individual under the rule of law in a post-Enlightenment nation predicated upon Christian principles. Harari’s ‘translation’ is a statement about what our era (currently) believes in a post-Darwinian culture about humanity’s evolutionary drives and our ‘selfish’ genes. ‘Biology’ may tell us those things but human experience and history tell a different story: there is altruism as well as egoism; there is love as well as fear and hatred; there is morality as well as amorality. The sword is not the only way in which events and epochs have been made. Indeed, to make biology/biochemistry the final irreducible way of perceiving human behaviour, as Harari seems to do, seems tragically short-sighted.

Religious illiteracy

I’m not surprised that the book is a bestseller in a (by and large) religiously illiterate society; and though it has a lot of merit in other areas, its critique of Judaism and Christianity is not historically respectable. A mere six lines of conjecture (p242) on the emergence of monotheism from polytheism – stated as fact – is indefensible. It lacks objectivity. The great world-transforming Abrahamic religion emerging from the deserts in the early Bronze Age period (as it evidently did) with an utterly new understanding of the sole Creator God is such an enormous change. It simply can’t be ignored in this way if the educated reader is to be convinced by his reconstructions.

Harari is demonstrably very shaky in his representation of what Christians believe

Harari is also demonstrably very shaky in his representation of what Christians believe. For example, his contention that belief in the Devil makes Christianity dualistic (equal independent good and evil gods) is simply untenable. One of the very earliest biblical texts (Book of Job) shows God allowing Satan to attack Job but irresistibly restricting his methods (Job 1:12). Later, Jesus banishes Satan from individuals (Mark 1:25 et al .) and the final book of the Bible shows God destroying Satan (Revelation 20:10). Not much dualism there! It’s all, of course, a profound mystery – but it’s quite certainly not caused by dualism according to the Bible. Harari either does not know his Bible or is choosing to misrepresent it. He also doesn’t know his Thomas Hardy who believed (some of the time!) precisely what Harari says ‘nobody in history’ believed, namely that God is evil – as evidenced in a novel like Tess of the d’Urbervilles or his poem The Convergence of the Twain .

Fumbling the problem of evil

We see another instance of Harari’s lack of objectivity in the way he deals with the problem of evil (p246). He states the well-worn idea that if we posit free will as the solution, that raises the further question: if God ‘knew in advance’ (Harari’s words) that the evil would be done why did he create the doer?

I would expect a scholar to present both sides of the argument, not a populist one-sided account as Harari does

But to be objective the author would need to raise the counter-question that if there is no free will, how can there be love and how can there be truth? Automatons without free will are coerced and love cannot exist between them – by definition. Again, if everything is predetermined then so is the opinion I have just expressed. In that case it has no validity as a measure of truth – it was predetermined either by chance forces at the Big Bang or by e.g. what I ate for breakfast which dictated my mood. These are age-old problems without easy solutions but I would expect a scholar to present both sides of the argument, not a populist one-sided account as Harari does.

Moreover, in Christian theology God created both time and space, but exists outside them. So the Christian God does not know anything ‘in advance’ which is a term applicable only to those who live inside the time–space continuum i.e. humanity. The Christian philosopher Boethius saw this first in the sixth century; theologians know it – but apparently Harari doesn’t, and he should.

Ignoring the resurrection

In common with so many, Harari is unable to explain why Christianity ‘took over the mighty Roman Empire' (p243) but calls it ‘one of history’s strangest twists’. So it is, but one explanation that should be considered is the resurrection of Christ which of course would fully account for it – if people would give the idea moment’s thought. But to the best of my knowledge there is no mention of it (even as an influential belief) anywhere in the book.

Harari is unable to explain why Christianity ‘took over the mighty Roman Empire'

The standard reason given for such an absence is that ‘such things don’t happen in history: dead men don’t rise.’ But that, I fear, is logically a hopeless answer. The speaker believes it didn’t happen because they have already presupposed that God is not there to do it. Drop the presupposition, and suddenly the whole situation changes: in the light of that thought it now becomes perfectly feasible that this ‘strange twist’ was part of the divine purpose. And the funny thing is that unlike other religions, this is precisely where Christianity is most insistent on its historicity . Peter, Paul, the early church in general were convinced that Jesus was alive and they knew as well as we do that dead men are dead – and they knew better than us that us that crucified men are especially dead! The very first Christian sermons (about AD 33) were about the facts of their experience – the resurrection of Jesus – not about morals or religion or the future.

A one-sided view of the Church

Harari is right to highlight the appalling record of human warfare and there is no point trying to excuse the Church from its part in this. I have written at length about this elsewhere, as have far more able people. But do we really think that because everyone in Europe was labelled Catholic or Protestant (‘ cuius regio, eius religio ’) that the wars they fought were about religion ?

If the Church is cited as a negative influence, why, in a scholarly book, is its positive influence not also cited?

As the Cambridge Modern History points out about the appalling Massacre of St Bartholomew’s Day in 1572 (which event Harari cites on p241) – the Paris mob would as soon kill Catholics as Protestants – and did. It was the result of political intrigue, sexual jealousy, human barbarism and feud. Oxford Professor Keith Ward points out ‘religious wars are a tiny minority of human conflicts’ in his book Is Religion Dangerous? If the Church is being cited as a negative influence, why, in a scholarly book, is its undeniably unrivalled positive influence over the last 300 years (not to mention all the previous years) not also cited? It’s simply not good history to ignore the good educational and social impact of the Church. Both sides need to feature. [1]

Philosophical fault-lines

I wonder too about Harari’s seeming complacency on occasion, for instance about where economic progress has brought us to. Is it acceptable for him to write (on p296): ‘When calamity strikes an entire region, worldwide relief efforts are usually successful in preventing the worst. People still suffer from numerous depredations, humiliations and poverty-related illnesses but in most countries nobody is starving to death’? Tell that to the people of Haiti seven years after the earthquake with two and a half million still, according to the UN, needing humanitarian aid. Or the people of South Sudan dying of thirst and starvation as they try to reach refugee camps. There are sixty million refugees living in appalling poverty and distress at this moment . In the light of those facts, I think Harari’s comment is rather unsatisfactory.

But there is a larger philosophical fault-line running through the whole book which constantly threatens to break its conclusions in pieces. His whole contention is predicated on the idea that humankind is merely the product of accidental evolutionary forces and this means he is blind to seeing any real intentionality in history. It has direction certainly, but he believes it is the direction of an iceberg, not a ship.

Many of his opening remarks are just unwarranted assumptions

This would be all right if he were straightforward in stating that all his arguments are predicated on the assumption that, as Bertrand Russell said, ‘Man is…but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms’ and utterly without significance. But instead, he does what a philosopher would call ‘begging the question’. That is, he assumes from the start what his contention requires him to prove – namely that mankind is on its own and without any sort of divine direction. Harari ought to have stated his assumed position at the start, but signally failed to do so. The result is that many of his opening remarks are just unwarranted assumptions based on that grandest of all assumptions: that humanity is cut adrift on a lonely planet, itself adrift in a drifting galaxy in a dying universe. Evidence please! – that humanity is ‘nothing but’ a biological entity and that human consciousness is not a pale (and fundamentally damaged) reflection of the divine mind.

The fact that (he says) Sapiens has been around for a long time, emerged by conquest of the Neanderthals and has a bloody and violent history has no logical connection to whether or not God made him (‘her’ for Harari) into a being capable of knowing right from wrong, perceiving God in the world and developing into Michelangelo, Mozart and Mother Teresa as well as into Nero and Hitler. To insist that such sublime or devilish beings are ‘no more than’ glorified apes is to ignore the elephant in the room: the small differences in our genetic codes are the very differences that may reasonably point to divine intervention – because the result is so shockingly disproportionate between ourselves and our nearest relatives. I’ve watched chimpanzees and the great apes; I love to do so (and especially adore gorillas!) but…so near, yet so so far.

Arguable assumptions

Here are a few short-hand examples of the author’s many assumptions to check out in context:

- ‘accidental genetic mutations…it was pure chance’ (p23)

- ‘no justice outside the common imagination of human beings’ (p31)

- ‘things that really exist’ (p35)

This last is such a huge leap of unwarranted faith. His concept of what ‘really exists’ seems to be ‘anything material’ but, in his opinion, nothing beyond this does ‘exist’ (his word). Actually, humans are mostly sure that immaterial things certainly exist: love, jealousy, rage, poverty, wealth, for starters. Dark matter also may make up most of the universe – it exists, we are told, but we can’t measure it.

His rendition of how biologists see the human condition is as one-sided as his treatment of earlier topics.

Harari’s final chapters are quite brilliant in their range and depth and hugely interesting about the possible future with the advent of AI – with or without Sapiens. His rendition, however, of how biologists see the human condition is as one-sided as his treatment of earlier topics. To say that our ‘subjective well-being is not determined by external parameters’ (p432) but by ‘serotonin, dopamine and oxytocin’ is to take the behaviourist view to the exclusion of all other biochemical/psychiatric science. Recent studies have concluded that human behaviour and well-being are the result not just of the amount of serotonin etc that we have in our bodies, but that our response to external events actually alters the amount of serotonin, dopamine etc which our bodies produce. It is two-way traffic. Our choices therefore are central. The way we behave actually affects our body chemistry, as well as vice versa. Harari is averse to using the word ‘mind’ and prefers ‘brain’ but the jury is out about whethe/how these two co-exist. There is one glance at this idea on page 458: without dismissing it he allows it precisely four lines, which for such a major ‘game-changer’ to the whole argument is a deeply worrying omission.

I liked his bold discussion about the questions of human happiness that historians and others are not asking, but was surprised by his two pages on ‘The Meaning of Life’ which I thought slightly disingenuous. ‘From a purely scientific viewpoint, human life has absolutely no meaning…Our actions are not part of some divine cosmic plan.’ (p438, my italics). The first sentence is fine – of course , that is true! How could it be otherwise? Science deals with how things happen, not why in terms of meaning or metaphysics . To look for meta physical answers in the physical sciences is ridiculous – they can’t be found there. It’s like looking for a sandpit in a swimming pool. Distinguished scientists like Sir Martin Rees and John Polkinghorne, at the very forefront of their profession, understand this and have written about the separation of the two ‘magisteria’. Science is about physical facts not meaning; we look to philosophy, history, religion and ethics for that. Harari’s second sentence is a non-sequitur – an inference that does not follow from the premise. God’s ‘cosmic plan’ may well be to use the universe he has set up to create beings both on earth and beyond (in time and eternity) which are glorious beyond our wildest dreams. I rather think he has already – when I consider what Sapiens has achieved.

A curiously encouraging end

I found the very last page of the book curiously encouraging:

We are more powerful than ever before…Worse still, humans seem to be more irresponsible than ever. Self-made gods with only the laws of physics to keep us company, we are accountable to no one. (p466)

Exactly! Time then for a change. Better to live in a world where we are accountable – to a just and loving God.

Harari is a brilliant writer, but one with a very decided agenda. He is excellent within his field but spreads his net too wide till some of the mesh breaks – allowing all sorts of confusing foreign bodies to pass in and out – and muddies the water. His failure to think clearly and objectively in areas outside his field will leave educated Christians unimpressed.

[1] See my book The Evil That Men Do . (Sacristy Press, 2016)

Marcus Paul

You might also be interested in

21 Lessons for the 21st Century � a critical review

Yuval Noah Harari's wide-ranging book offers fascinating insights. But it also contains unspoken assumptions and unexamined biases.

Transgender � a review

Tom Roberts

With transgender issues raising difficult questions, this book from Vaughan Roberts offers a helpful introduction.

Gender Identity and the Body

Vaughan Roberts

What does the biblical view of creation have to say in the transgender debate?

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Fitness & Wellbeing

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance Deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Climate 100

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Wine Offers

- Betting Sites

- Casino Sites

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari, book review: Eloquent history of what makes us human

Welcome wit warms this treatise on human development, article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails.

It is an impediment to understanding the human story that the innovations that made us human – a long list including the control of fire, articulate language, the development of agriculture and herding, the working of metals, glass and other materials, abstract reasoning – took place over periods out of kilter with the time span of human generations.

Each generation saw itself as living a similar life to its predecessors, with the occasional addition of a slightly better way of accomplishing one thing or another. The true course of events is only now being uncovered by the sophisticated forensic techniques developed by science, not least the sequencing of ancient DNA and the mapping of human migrations through the DNA profiles of people living today.

As a historian, Yuval Harari (who teaches at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) belongs to the school founded by Jared Diamond (who endorses the book on the cover), in applying scientific research to every aspect of human history, not just the parts for which no written accounts exist. In truth, Harari uses less science than Diamond. He emphasizes the difficulty of knowing in detail the lives of our remote forebears and is often content to say – of topics that are being urgently investigated by the more forensically inclined – "frankly, we don't know". His ideas are mostly not new, being derived from Diamond, but he has a very trenchant way of putting them over.

Typical is a bravura passage on the domestication of wheat, in which he floats the conceit that wheat domesticated us. What was once an undistinguished grass in a small part of the Middle East now covers a global area eight times the size of England. Humans have to slave to serve the wheat god: " Wheat didn't like rocks and pebbles, so Sapiens broke their backs clearing fields. Wheat didn't like sharing its space..." and so on.

Harari proposes three big revolutions around which his story revolves: the Cognitive Revolution of around 70,000 years ago (articulate language); the Agricultural Revolution of 10,000 years ago; and the Scientific Revolution of 500 years ago. The last is part of history, the second is increasingly well understood, but the first is still shrouded in a mystery that DNA research will probably one day clear up.

Although the book is billed as a short history, it is just as much a philosophical meditation on the human condition. One great overriding argument runs through it: that all human culture is an invention. The rules of football; the concept of a limited liability company; the laws relating to property and marriage; the character, actions and notional edicts of deities – all are examples of what Harari calls Imagined Order. He develops this idea into a magnificent, humane polemic, particularly highlighting the sorrows that accrue from society's justification of its cruel practices as either natural or ordained by God (they are neither).

Not only is Harari eloquent and humane, he is often wonderfully, mordantly funny. Much of what we take to be inherent cultural traditions are of recent adoption: "William Tell never tasted chocolate, and Buddha never spiced up his food with chilli".

Towards the end of the book, the influence of thinkers other than Diamond emerges. He rehearses Steven Pinker's argument that objectively (to judge by mortality statistics) the world is, despite appearances, becoming less violent; passages on individual happiness and how it can be assessed alongside more conventional historical topics smack of Theodore Zeldin, both in style and content.

Inevitably, in a "big picture" account such as this, some portions of the canvas are less hatched in than others. For this reader, these later sections seemed weaker, but in the last chapter the brio returns as Harari considers what humankind – who developed culture to escape the constraints of biology – will became now that it is also a biological creator. Sapiens is a brave and bracing look at a species that is mostly in denial about the long road to now and the crossroads it is rapidly approaching.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

A GRAPHIC HISTORY: THE BIRTH OF HUMANKIND: VOLUME ONE

by Yuval Noah Harari ; adapted by David Vandermeulen & illustrated by Daniel Casanave & Claire Champion ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 27, 2020

An informative, breathless sprint through the evolution and consequences of human development.

The professor and popular historian expands the reach of his internationally bestselling work with the launch of a graphic nonfiction series.

In a manner that is both playful and provocative, Harari teams with co-creators adept at the graphic format to enliven his academic studies. Here, a cartoon version of the professor takes other characters (and readers) on something of a madcap thrill ride through the history of human evolution, with a timeline that begins almost 14 billion years ago and extends into the future, when humanity becomes the defendant in “Ecosystem vs. Homo Sapiens,” a trial presided over by “Judge Gaia.” As Harari and his fellow time travelers visit with other academics and a variety of species, the vivid illustrations by Casaneve and colorist Champion bring the lessons of history into living color, and Vandermeulen helps condense Harari’s complex insights while sustaining narrative momentum. The text and illustrations herald evolution as “the greatest show on earth” while showing how only one of “six different human species” managed to emerge atop the food chain. While the Homo sapiens were not nearly as large, strong, fast, or powerful as other species that suffered extinction, they were able to triumph due to their development of the abilities to cooperate, communicate, and, perhaps most important, tell and share stories. That storytelling ultimately encompasses fiction, myth, history, and spirituality, and the success of shared stories accounts for a wide variety of historical events and trends, including Christianity, the French Revolution, and the Third Reich. The narrative climaxes with a crime caper, as a serial-killing spree results in the extinction of so many species, and the “Supreme Court of the future” must rule on the case against Homo sapiens . Within those deliberations, it’s clear that not “being aware of the consequences of their actions” is not a valid excuse.

Pub Date: Oct. 27, 2020

ISBN: 978-0-06-305133-1

Page Count: 248

Publisher: Perennial/HarperCollins

Review Posted Online: Oct. 20, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Nov. 15, 2020

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY | ANCIENT | WORLD | HISTORY | GENERAL GRAPHIC NOVELS & COMICS | GENERAL HISTORY

Share your opinion of this book

More by Yuval Noah Harari

BOOK REVIEW

by Yuval Noah Harari

by Yuval Noah Harari ; illustrated by Ricard Zaplana Ruiz

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2023

New York Times Bestseller

by Walter Isaacson ‧ RELEASE DATE: Sept. 12, 2023

Alternately admiring and critical, unvarnished, and a closely detailed account of a troubled innovator.

A warts-and-all portrait of the famed techno-entrepreneur—and the warts are nearly beyond counting.

To call Elon Musk (b. 1971) “mercurial” is to undervalue the term; to call him a genius is incorrect. Instead, Musk has a gift for leveraging the genius of others in order to make things work. When they don’t, writes eminent biographer Isaacson, it’s because the notoriously headstrong Musk is so sure of himself that he charges ahead against the advice of others: “He does not like to share power.” In this sharp-edged biography, the author likens Musk to an earlier biographical subject, Steve Jobs. Given Musk’s recent political turn, born of the me-first libertarianism of the very rich, however, Henry Ford also comes to mind. What emerges clearly is that Musk, who may or may not have Asperger’s syndrome (“Empathy did not come naturally”), has nurtured several obsessions for years, apart from a passion for the letter X as both a brand and personal name. He firmly believes that “all requirements should be treated as recommendations”; that it is his destiny to make humankind a multi-planetary civilization through innovations in space travel; that government is generally an impediment and that “the thought police are gaining power”; and that “a maniacal sense of urgency” should guide his businesses. That need for speed has led to undeniable successes in beating schedules and competitors, but it has also wrought disaster: One of the most telling anecdotes in the book concerns Musk’s “demon mode” order to relocate thousands of Twitter servers from Sacramento to Portland at breakneck speed, which trashed big parts of the system for months. To judge by Isaacson’s account, that may have been by design, for Musk’s idea of creative destruction seems to mean mostly chaos.

Pub Date: Sept. 12, 2023

ISBN: 9781982181284

Page Count: 688

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Review Posted Online: Sept. 12, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Oct. 15, 2023

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | BUSINESS | SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY | ISSUES & CONTROVERSIES | POLITICS

More by Walter Isaacson

by Walter Isaacson with adapted by Sarah Durand

by Walter Isaacson

More About This Book

BOOK TO SCREEN

HOW DO APPLES GROW?

by Betsy Maestro & illustrated by Giulio Maestro ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 30, 1992

A straightforward, carefully detailed presentation of how ``fruit comes from flowers,'' from winter's snow-covered buds through pollination and growth to ripening and harvest. Like the text, the illustrations are admirably clear and attractive, including the larger-than-life depiction of the parts of the flower at different stages. An excellent contribution to the solidly useful ``Let's-Read-and-Find-Out-Science'' series. (Nonfiction/Picture book. 4-9)

Pub Date: Jan. 30, 1992

ISBN: 0-06-020055-3

Page Count: 32

Publisher: HarperCollins

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 15, 1991

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

More by Betsy Maestro

by Betsy Maestro & illustrated by Giulio Maestro

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

October 8, 2024

- The American presidential election through an international (literary) lens

- Sarah Aziza on Gaza, a year later

- Sage Mehta on growing up with the writer Ved Mehta

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The book does a very good job summarizing key points of human history. The important thing to note is that it is a summary. In my opinion, the author does a good job trying to be unbiased as possible, but each topic he covers has its own rich history and complexities.

Recently I went to buy the hard copy of the book and I found a slew of despairing reviews saying that it is full of assertions and half truths founded with a lack of actual research and sources. Does anyone have any thoughts on why this book is great, or why this book is bullshit.

Is the book "Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind" by Yuval Noah Harari historically accurate in the development of human evolution?

The book covers a mind-boggling 13.5 billion years of pre-history and history. From the outset, Harari seeks to establish the multifold forces that made Homo (‘man’) into Homo sapiens (‘wise man’) – exploring the impact of a large brain, tool use, complex social structures and more.

Although the book is billed as a short history, it is just as much a philosophical meditation on the human condition. One great overriding argument runs through it: that all human culture is an...

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari has an overall rating of Positive based on 9 book reviews.

An informative, breathless sprint through the evolution and consequences of human development. bookshelf. shop now. The professor and popular historian expands the reach of his internationally bestselling work with the launch of a graphic nonfiction series.

If you were unfortunate enough to catch me after a beer this past month, you probably know about the book I’ve been reading — Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari. It’s an excellent book I’m happy to talk about.

Sapiens is the sort of book that sweeps the cobwebs out of your brain. Its author, Yuval Noah Harari, is a young Israeli academic and an intellectual acrobat whose logical leaps have you gasping with admiration.

1,087,084 ratings55,665 reviews. From a renowned historian comes a groundbreaking narrative of humanity’s creation and evolution—a #1 international bestseller—that explores the ways in which biology and history have defined us and enhanced our understanding of what it means to be “human.”