- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

BMI indicates body mass index; SES, socioeconomic status.

a Variables smoking status, SES, drinking pattern, former drinker bias only, occasional drinker bias, median age, and gender were removed.

b Variables race, diet, exercise, BMI, country, follow-up year, publication year, and unhealthy people exclusion were removed.

eAppendix. Methodology of Meta-analysis on All-Cause Mortality and Alcohol Consumption

eReferences

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Systematic Search Process for Studies of Alcohol Consumption and Risk of All-Cause Mortality

eTable 1. Newly Included 20 Studies (194 Risk Estimates) of All-Cause Mortality and Consumption in 2015 to 2022

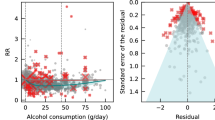

eFigure 2. Funnel Plot of Log-Relative Risk (In(RR)) of All-Cause Mortality Due to Alcohol Consumption Against Inverse of Standard Error of In(RR)

eFigure 3. Relative Risk (95% CI) of All-Cause Mortality Due to Any Alcohol Consumption Without Any Adjustment for Characteristics of New Studies Published between 2015 and 2022

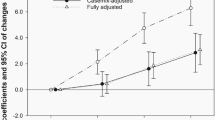

eFigure 4. Unadjusted, Partially Adjusted, and Fully Adjusted Relative Risk (RR) of All-Cause Mortality for Drinkers (vs Nondrinkers), 1980 to 2022

eTable 2. Statistical Analysis of Unadjusted Mean Relative Risk (RR) of All-Cause Mortality for Different Categories of Drinkers for Testing Publication Bias and Heterogeneity of RR Estimates From Included Studies

eTable 3. Mean Relative Risk (RR) Estimates of All-Cause Mortality Due to Alcohol Consumption up to 2022 for Subgroups (Cohorts Recruited 50 Years of Age or Younger and Followed up to 60 Years of Age)

Data Sharing Statement

- Errors in Figure and Supplement JAMA Network Open Correction May 9, 2023

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Zhao J , Stockwell T , Naimi T , Churchill S , Clay J , Sherk A. Association Between Daily Alcohol Intake and Risk of All-Cause Mortality : A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses . JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e236185. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6185

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Association Between Daily Alcohol Intake and Risk of All-Cause Mortality : A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses

- 1 Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

- 2 Department of Psychology, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire, United Kingdom

- Correction Errors in Figure and Supplement JAMA Network Open

Question What is the association between mean daily alcohol intake and all-cause mortality?

Findings This systematic review and meta-analysis of 107 cohort studies involving more than 4.8 million participants found no significant reductions in risk of all-cause mortality for drinkers who drank less than 25 g of ethanol per day (about 2 Canadian standard drinks compared with lifetime nondrinkers) after adjustment for key study characteristics such as median age and sex of study cohorts. There was a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality among female drinkers who drank 25 or more grams per day and among male drinkers who drank 45 or more grams per day.

Meaning Low-volume alcohol drinking was not associated with protection against death from all causes.

Importance A previous meta-analysis of the association between alcohol use and all-cause mortality found no statistically significant reductions in mortality risk at low levels of consumption compared with lifetime nondrinkers. However, the risk estimates may have been affected by the number and quality of studies then available, especially those for women and younger cohorts.

Objective To investigate the association between alcohol use and all-cause mortality, and how sources of bias may change results.

Data Sources A systematic search of PubMed and Web of Science was performed to identify studies published between January 1980 and July 2021.

Study Selection Cohort studies were identified by systematic review to facilitate comparisons of studies with and without some degree of controls for biases affecting distinctions between abstainers and drinkers. The review identified 107 studies of alcohol use and all-cause mortality published from 1980 to July 2021.

Data Extraction and Synthesis Mixed linear regression models were used to model relative risks, first pooled for all studies and then stratified by cohort median age (<56 vs ≥56 years) and sex (male vs female). Data were analyzed from September 2021 to August 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures Relative risk estimates for the association between mean daily alcohol intake and all-cause mortality.

Results There were 724 risk estimates of all-cause mortality due to alcohol intake from the 107 cohort studies (4 838 825 participants and 425 564 deaths available) for the analysis. In models adjusting for potential confounding effects of sampling variation, former drinker bias, and other prespecified study-level quality criteria, the meta-analysis of all 107 included studies found no significantly reduced risk of all-cause mortality among occasional (>0 to <1.3 g of ethanol per day; relative risk [RR], 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.06; P = .41) or low-volume drinkers (1.3-24.0 g per day; RR, 0.93; P = .07) compared with lifetime nondrinkers. In the fully adjusted model, there was a nonsignificantly increased risk of all-cause mortality among drinkers who drank 25 to 44 g per day (RR, 1.05; P = .28) and significantly increased risk for drinkers who drank 45 to 64 and 65 or more grams per day (RR, 1.19 and 1.35; P < .001). There were significantly larger risks of mortality among female drinkers compared with female lifetime nondrinkers (RR, 1.22; P = .03).

Conclusions and Relevance In this updated systematic review and meta-analysis, daily low or moderate alcohol intake was not significantly associated with all-cause mortality risk, while increased risk was evident at higher consumption levels, starting at lower levels for women than men.

The proposition that low-dose alcohol use protects against all-cause mortality in general populations continues to be controversial. 1 Observational studies tend to show that people classified as “moderate drinkers” have longer life expectancy and are less likely to die from heart disease than those classified as abstainers. 2 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of this literature 3 confirm J-shaped risk curves (protective associations at low doses with increasing risk at higher doses). However, mounting evidence suggests these associations might be due to systematic biases that affect many studies. For example, light and moderate drinkers are systematically healthier than current abstainers on a range of health indicators unlikely to be associated with alcohol use eg, dental hygiene, exercise routines, diet, weight, income 4 ; lifetime abstainers may be systematically biased toward poorer health 5 ; studies fail to control for biases in the abstainer reference group, in particular failing to remove “sick quitters” or former drinkers, many of whom cut down or stop for health reasons 2 ; and most studies have nonrepresentative samples leading to an overrepresentation of older White men. Adjustment of cohort samples to make them more representative has been shown to eliminate apparent protective associations. 6 Mendelian randomization studies that control for the confounding effects of sociodemographic and environmental factors find no evidence of cardioprotection. 7

We published 2 previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses that investigated these hypotheses. The first of these focused on all-cause mortality, 8 finding negligible reductions in mortality risk with low-volume alcohol use when study-level controls were introduced for potential bias and confounding, such as the widespread practice of misclassifying former drinkers and/or current occasional drinkers as abstainers (ie, not restricting reference groups to lifetime abstainers). 8 Our alcohol and coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality meta-analysis of 45 cohort studies 9 found that CHD mortality risk differed widely by age ranges and sex of study populations. In particular, young cohorts followed up to old age did not show significant cardio-protection for low-volume use. Cardio-protection was only apparent among older cohorts that are more exposed to lifetime selection biases (ie, increasing numbers of “sick-quitters” in the abstainer reference groups and the disproportionate elimination of drinkers from the study sample who had died or were unwell).

The present study updates our earlier systematic review and meta-analysis for all-cause mortality and alcohol use, 8 including studies published up to July 2021 (ie, 6.5 years of additional publications). The study also investigated the risk of all-cause mortality for alcohol consumption according to (1) median ages of the study populations (younger than 56 years or 56 years and older), replicating the methods of Zhao et al 9 ; (2) the sex distribution of the study populations, and (3) studies of cohorts recruited before a median age of 51 years of age and followed up in health records until a median age of at least 60 years (ie, with stricter rules to further minimize lifetime selection biases). Because younger cohorts followed up to an age at which they may experience heart disease are less likely to be affected by lifetime selection biases, 9 we hypothesized that such studies would be less likely to show reduced mortality risks for low-volume drinkers. Finally, we reran the analyses using occasional drinkers (<1 drink per week) as the reference, for whom physiological health benefits are unlikely. Occasional drinkers are a more appropriate reference group, given evidence demonstrating that lifetime abstainers may be biased toward ill health. 10

The present study updates the systematic reviews and meta-analyses described above 8 by including studies published up to July 2021 to investigate whether the risk differed for subgroups. The study protocol was preregistered on the Open Science Framework. 11 Inclusion criteria, search strategy, study selection, data extraction, and statistical analytical methods of the study are summarized in later sections (see eAppendix in Supplement 1 for more details).

The systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses ( PRISMA ) reporting guideline. 12 The review sought cohort studies of all-cause mortality and alcohol consumption. We identified all potentially relevant articles published up to July 31, 2021, regardless of language, by searching PubMed and Web of Science, through reference list cross-checking of previous meta-analyses (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 ). There were 87 studies identified by Stockwell et al. 8 After inclusion of 20 new studies meeting inclusion criteria, there were a total of 107 cohort studies (eTable 1 in Supplement 1 ). 13 - 32

Three coders (J. Z., F. A., and J. C.) reviewed all eligible studies to extract and code data independently from all studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Data extracted included (1) outcome, all-cause mortality; (2) measures of alcohol consumption; (3) study characteristics, including cohort ages at recruitment and follow-up; (4) types of misclassification error of alcohol consumers and abstainers; (5) controlled variables in individual studies. Alcoholic drinks were converted into grams per day according to country-specific definitions if not otherwise defined. 33 , 34

We also assessed publication bias, heterogeneity, and confounding of covariates that might potentially affect the association of interest using several statistical approaches. 35 - 41 Relative risk (RR), including hazard ratios or rate ratios, were converted to natural log-transformed formats to deal with skewness. Publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of the funnel plot of log-RR of all-cause mortality due to alcohol consumption against the inverse standard error of log-RR 42 and Egger’s linear regression method. 36 We also plotted forest graphs of log-RR of all-cause mortality for any level of drinking to assess heterogeneity among studies. 42 The between-study heterogeneity of RRs were assessed using Cochran Q 37 and the I 2 statistic. 38 If heterogeneity was detected, mixed-effects models were used to obtain the summarized RR estimates. Mixed-effects regression analyses were performed in which drinking groups and control variables were treated as fixed-effects with a random study effect because of significant heterogeneity. 43

All analyses were weighted by the inverse of the estimated variance of the natural log relative risk. Variance was estimated from reported standard errors, confidence intervals, or number of deaths. The weights for each individual study were created using the inverse variance weight scheme and used in mixed regression analysis to get maximum precision for the main results of the meta-analysis. 42 In comparison with lifetime abstainers, the study estimated the mean RR of all-cause mortality for former drinkers (ie, now completely abstaining), current occasional (<9.1 g per week), low-volume (1.3-24.0 g per day), medium-volume (25.0-44.0 g per day), high-volume (45.0-64.0 g) and highest-volume drinkers (≥65.0 grams per day). The analyses adjusted for the potential confounding effects of study characteristics including the median age and sex distribution of study samples, drinker biases, country where a study was conducted, follow-up years and presence or absence of confounders. Analyses were also repeated using occasional drinkers as the reference group. We used t tests to calculate P values, and significance was set at .05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and the SAS MIXED procedure was used to model the log-transformed RR. 44 Data were analyzed from September 2021 to August 2022.

There were 724 estimates of the risk relationship between level of alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality from 107 unique studies 13 - 32 , 45 - 131 , including 4 838 825 participants and 425 564 deaths available for the analysis. Table 1 describes the sample characteristics of the metadata. Of 39 studies 13 , 15 , 18 , 21 , 23 - 26 , 29 , 31 , 45 - 47 , 49 , 50 , 52 - 54 , 57 - 59 , 62 , 64 , 70 , 80 , 81 , 85 , 87 , 91 , 94 , 96 , 100 , 104 , 107 , 118 , 124 , 125 , 127 , 130 reporting RR estimates for men and women separately, 33 14 , 17 , 48 , 51 , 61 , 63 , 66 , 68 , 69 , 72 , 76 , 79 , 83 , 84 , 86 , 88 , 90 , 92 , 93 , 97 , 98 , 101 , 103 , 105 , 109 - 111 , 113 - 115 , 119 , 120 , 128 were for males only, 8 16 , 65 , 73 , 99 , 102 , 108 , 112 , 123 for females only, and 30 13 , 19 - 22 , 26 - 30 , 32 , 55 , 56 , 67 , 71 , 74 , 75 , 77 , 78 , 82 , 84 , 89 , 95 , 106 , 116 , 117 , 121 , 122 , 126 , 129 for both sexes. Twenty-one studies 13 , 17 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 26 , 27 , 45 - 58 (220 risk estimates) were free from abstainer bias (ie, had a reference group of strictly defined lifetime abstainers). There were 50 studies 14 - 16 , 18 , 20 , 23 - 25 , 29 , 59 - 99 (265 risk estimates) with both former and occasional drinker bias; 28 studies 28 , 30 - 32 , 100 - 122 , 130 (177 risk estimates) with only former drinker bias; and 8 studies 123 - 129 , 131 (62 risk estimates) with only occasional drinker bias.

Unadjusted mean RR estimates for most study subgroups categorized by methods/sample characteristics showed markedly or significantly higher RRs for alcohol consumers as a group vs abstainers. Exceptions were for studies with less than 10 years of follow-up and those with some form of abstainer bias ( Table 1 ). Bivariable analyses showed that mortality risks for alcohol consumers varied considerably according to other study characteristics, such as quality of the alcohol consumption measure, whether unhealthy individuals were excluded at baseline, and whether socioeconomic status was controlled for ( Table 1 ).

No evidence of publication bias was detected either by inspection of symmetry in the funnel plot of log-RR estimates and their inverse standard errors (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1 ) or by Egger linear regression analysis (eTable 2 in Supplement 1 , all P > .05 for each study group). Significant heterogeneity was observed across studies for all drinking categories confirmed by both the Q statistic ( Q 723 = 5314.80; P < .001) and I 2 estimates (all >85.87%). (See eFigure 3 in Supplement 1 for forest plot of unadjusted risk estimates of mortality risks for the 20 newly identified studies).

Pooled unadjusted estimates (724 observations) showed significantly higher risk for former drinkers (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.11-1.33; P = .001) and significantly lower risk for low-volume drinkers (RR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.81-0.88; P = .001) compared with abstainers as defined in the included studies ( Table 2 ; eFigure 4 in Supplement 1 ). In the fully adjusted model, mortality RR estimates increased for all drinking categories, becoming nonsignificant for low-volume drinkers (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.85-1.01; P = .07), occasional drinkers (>0 to <1.3 g of ethanol per day; RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.06; P = .41), and drinkers who drank 25 to 44 g per day (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.96-1.14; P = .28). There was a significantly increased risk among drinkers who drank 45 to 64 g per day (RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.07-1.32; P < .001) and 65 or more grams (RR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.23-1.47; P < .001). The Figure shows the changes in RR estimates for low-volume drinkers when removing each covariate from the fully adjusted model. In most cases, removing study-level covariates tended to yield lower risk estimates from alcohol use.

Table 2 presents the RR estimates when occasional drinkers were the reference group. In fully adjusted models, higher though nonsignificant mortality risks were observed for both abstainers and medium-volume drinkers (RR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94-1.16; P = .44 and RR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.96-1.25; P = .19, respectively). There were significantly elevated risks for both high and higher volume drinkers (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07-1.44; P = .004 and RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.23-1.61; . P = 001, respectively).

As hypothesized, there was a significant interaction between cohort age and mortality risk ( P = .02; F 601 = 2.93) and so RR estimates for drinkers were estimated in analyses stratified by median age of the study populations at enrollment ( Table 3 ). In unadjusted and partially adjusted analyses, older cohorts displayed larger reductions in mortality risk associated with low-volume consumption than younger cohorts. However, in fully adjusted analyses with multiple covariates included for study characteristics, these differences disappeared. Younger cohorts also displayed greater mortality risks than older cohorts at higher consumption levels. Among studies in which participants were recruited at age 50 years or younger and followed up to age 60 years (ie, there was likely reduced risk of lifetime selection bias) higher RR estimates were observed for all drinking groups vs lifetime abstainers. These differences were significant in all drinking groups except low-volume drinkers (eTable 3 in Supplement 1 ).

Across all levels of alcohol consumption, female drinkers had a higher RR of all-cause mortality than males ( P for interaction = .001). As can be seen in Table 4 , all female drinkers had a significantly increased mortality risk compared with female lifetime nondrinkers (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.02-1.46; P = .03). Compared with lifetime abstainers, there was significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality among male drinkers who drank 45 to 64 g per day (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.03-1.28; P = .01) and drank 65 or more (RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.23-1.47; P < .001), and among female drinkers who drank 25 to 44 g per day (RR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.08-1.36; P < .01), 45 to 64 g (RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.11-1.63; P < .01) and 65 or more grams (RR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.44-1.80; P = .001).

In fully adjusted, prespecified models that accounted for effects of sampling, between-study variation, and potential confounding from former drinker bias and other study-level covariates, our meta-analysis of 107 studies found (1) no significant protective associations of occasional or low-volume drinking (moderate drinking) with all-cause mortality; and (2) an increased risk of all-cause mortality for drinkers who drank 25 g or more and a significantly increased risk when drinking 45 g or more per day.

Several meta-analytic strategies were used to explore the role of abstainer reference group biases caused by drinker misclassification errors and also the potential confounding effects of other study-level quality covariates in studies. 2 Drinker misclassification errors were common. Of 107 studies identified, 86 included former drinkers and/or occasional drinkers in the abstainer reference group, and only 21 were free of both these abstainer biases. The importance of controlling for former drinker bias/misclassification is highlighted once more in our results which are consistent with prior studies showing that former drinkers have significantly elevated mortality risks compared with lifetime abstainers.

In addition to presenting our fully adjusted models, a strength of the study was the examination of the differences in relative risks according to unadjusted and partially adjusted models, including the effect of removing individual covariates from the fully adjusted model. We found evidence that abstainer biases and other study characteristics changed the shape of the risk relationship between mortality and rising alcohol consumption, and that most study-level controls increased the observed risks from alcohol, or attenuated protective associations at low levels of consumption such that they were no longer significant. The reduced RR estimates for occasional or moderate drinkers observed without adjustment may be due to the misclassification of former and occasional drinkers into the reference group, a possibility which is more likely to have occurred in studies of older cohorts which use current abstainers as the reference group. This study also demonstrates the degree to which observed associations between consumption and mortality are highly dependent on the modeling strategy used and the degree to which efforts are made to minimize confounding and other threats to validity.

It also examined risk estimates when using occasional drinkers rather than lifetime abstainers as the reference group. The occasional drinker reference group avoids the issue of former drinker misclassification that can affect the abstainer reference group, and may reduce confounding to the extent that occasional drinkers are more like low-volume drinkers than are lifetime abstainers. 2 , 8 , 132 In the unadjusted and partially adjusted analyses, using occasional drinkers as the reference group resulted in nonsignificant protective associations and lower point estimates for low-volume drinkers compared with significant protective associations and higher point estimates when using lifetime nondrinkers as the reference group. In the fully adjusted models, there were nonsignificant protective associations for low-volume drinkers whether using lifetime abstainers or occasional drinkers as the reference group, though this was only a RR of 0.97 for the latter.

Across all studies, there were few differences in risk for studies when stratified by median age of enrollment above or below age 56 years in the fully adjusted analyses. However, in the subset of studies who enrolled participants aged 50 years or younger who were followed for at least 10 years, occasional drinkers and medium-volume drinkers had significantly increased risk of mortality and substantially higher risk estimates for high- and higher-volume consumption compared with results from all studies. This is consistent with our previous meta-analysis for CHD, 9 in which younger cohorts followed up to older age did not show a significantly beneficial association of low-volume consumption, while older cohorts, with more opportunity for lifetime selection bias, showed marked, significant protective associations.

Our study also found sex differences in the risk of all-cause mortality. A larger risk of all-cause mortality for women than men was observed when drinking 25 or more grams per day, including a significant increase in risk for medium-level consumption for women that was not observed for men. However, mortality risk for mean consumption up to 25 g per day were very similar for both sexes.

A number of limitations need to be acknowledged. A major limitation involves imperfect measurement of alcohol consumption in most included studies, and the fact that consumption in many studies was assessed at only 1 point in time. Self-reported alcohol consumption is underreported in most epidemiological studies 133 , 134 and even the classification of drinkers as lifetime abstainers can be unreliable, with several studies in developed countries finding that the majority of self-reported lifetime abstainers are in fact former drinkers. 135 , 136 If this is the case, the risks of various levels of alcohol consumption relative to presumed lifetime abstainers are underestimates. Merely removing former drinkers from analyses may bias studies in favor of drinkers, since former drinkers may be unhealthy, and should rightly be reallocated to drinking groups according to their history. However, this has only been explored in very few studies. Our study found that mortality risk differed significantly by cohort age and sex. It might be that the risk is also higher for other subgroups, such as people living with HIV, 137 a possibility future research should investigate.

The number of available studies in some stratified analyses was small, so there may be limited power to control for potential study level confounders. However, the required number of estimates per variable for linear regression can be much smaller than in logistic regression, and a minimum of at least 2 estimates per variable is recommended for linear regression analysis, 138 suggesting the sample sizes were adequate in all models presented. It has been demonstrated that a pattern of binge (ie, heavy episodic) drinking removes the appearance of reduced health risks even when mean daily volume is low. 139 Too few studies adequately controlled for this variable to investigate its association with different outcomes across studies. Additionally, our findings only apply to the net effect of alcohol at different doses on all-cause mortality, and different risk associations likely apply for specific disease categories. The biases identified here likely apply to estimates of risk for alcohol and all diseases. It is likely that correcting for these biases will raise risk estimates for many types of outcome compared with most existing estimates.

This updated meta-analysis did not find significantly reduced risk of all-cause mortality associated with low-volume alcohol consumption after adjusting for potential confounding effects of influential study characteristics. Future longitudinal studies in this field should attempt to minimize lifetime selection biases by not including former and occasional drinkers in the reference group, and by using younger cohorts (ie, age distributions that are more representative of drinkers in the general population) at baseline.

Accepted for Publication: February 17, 2023.

Published: March 31, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6185

Correction: This article was corrected on May 9, 2023, to fix errors in the Figure and Supplement.

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2023 Zhao J et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Jinhui Zhao, PhD, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria, PO Box 1700 STN CSC, Victoria, BC V8Y 2E4, Canada ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Drs Zhao and Stockwell had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Zhao, Stockwell, Naimi, Churchill, Sherk.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Zhao, Stockwell, Naimi, Clay.

Drafting of the manuscript: Zhao, Stockwell, Clay.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Zhao, Churchill.

Obtained funding: Zhao, Stockwell, Sherk.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Zhao, Stockwell, Naimi.

Supervision: Zhao, Stockwell, Naimi.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Stockwell reported receiving personal fees from Ontario Public Servants Employees Union for expert witness testimony and personal fees from Alko outside the submitted work. Dr Sherk reported receiving grants from Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: This study was partly funded by the CCSA as a subcontract for a Health Canada grant to develop guidance for Canadians on alcohol and health.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: Health Canada had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. CCSA staff conducted a preliminary search to identify potentially relevant articles but did not participate in decisions about inclusion/exclusion of studies, coding, analysis, interpretation of results or approving the final manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2 .

Additional Contributions: We gratefully acknowledge contributions by Christine Levesque, PhD (CCSA), and Nitika Sanger, PhD (CCSA), who conducted a preliminary literature search for potentially relevant articles. We also acknowledge the leadership of Drs Catherine Paradis, PhD (CCSA), and Peter Butt, MD (University of Saskatchewan), who cochaired the process of developing Canada’s new guidance on alcohol and health, a larger project which contributed some funds for the work undertaken for this study. We are grateful to Fariha Alam, MPH (Canadian Institute for Substance Use and Research), for her help coding the studies used in this study. None of them received any compensation beyond their normal salaries for this work.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

- Alcohol or alcoholic beverages contain ethanol, a psychoactive and toxic substance that can cause dependence.

- Worldwide, around 2.6 million deaths were caused by alcohol consumption in 2019. Of these, 1.6 million deaths were from noncommunicable diseases, 700 000 deaths from injuries and 300 000 deaths from communicable diseases.

- The alcohol-attributable mortality was heaviest among men, accounting for 2 million deaths compared to 600 000 deaths among women, in 2019.

- An estimated 400 million people, or 7% of the world’s population aged 15 years and older, lived with alcohol use disorders. Of this, 209 million people (3.7% of the adult world population) lived with alcohol dependence.

- Alcohol consumption, even at low levels can bring health risks, but most alcohol related harms come from heavy episodic or heavy continuous alcohol consumption.

- Effective alcohol control interventions exist and should be utilized more, at the same time it is important for people to know risks associated with alcohol consumption and take individual actions to protect from its harmful effects.

Alcohol and alcoholic beverages contain ethanol, which is a psychoactive and toxic substance with dependence-producing properties. Alcohol has been widely used in many cultures for centuries, but it is associated with significant health risks and harms.

Worldwide, 2.6 million deaths were attributable to alcohol consumption in 2019, of which 2 million were among men and 0.6 million among women. The highest levels of alcohol-related deaths per 100 000 persons are observed in the WHO European and African Regions with 52.9 deaths and 52.2 deaths per 100 000 people, respectively.

People of younger age (20–39 years) are disproportionately affected by alcohol consumption with the highest proportion (13%) of alcohol-attributable deaths occurring within this age group in 2019.

The data on global alcohol consumption in 2019 shows that an estimated 400 million people aged 15 years and older live with alcohol use disorders, and an estimated 209 million live with alcohol dependence.

There has been some progress; from 2010 to 2019, the number of alcohol-attributable deaths per 100 000 people decreased by 20.2% globally.

There has been a steady increase in the number of countries developing national alcohol policies. Almost all countries implement alcohol excise taxes. However, countries report continued interference from the alcohol industry in policy development.

Based on 2019 data, about 54% out of 145 reporting countries had national guidelines/standards for specialized treatment services for alcohol use disorders, but only 46% of countries had legal regulations to protect the confidentiality of people in treatment.

Access to screening, brief intervention and treatment for people with hazardous alcohol use and alcohol use disorder remains very low, as well as access to medications for treatment of alcohol use disorders. Overall, the proportion of people with alcohol use disorders in contact with treatment services varies from less than 1% to no more than 14% in all countries where such data are available.

Health risks of alcohol use

Alcohol consumption is found to play a causal role in more than 200 diseases, injuries and other health conditions. However, the global burden of disease and injuries caused by alcohol consumption can be quantified for only 31 health conditions on the basis of the available scientific evidence for the role of alcohol use in their development, occurrence and outcomes.

Drinking alcohol is associated with risks of developing noncommunicable diseases such as liver diseases, heart diseases, and different types of cancers, as well as mental health and behavioural conditions such as depression, anxiety and alcohol use disorders.

An estimated 474 000 deaths from cardiovascular diseases were caused by alcohol consumption in 2019.

Alcohol is an established carcinogen and alcohol consumption increases the risk of several cancers, including breast, liver, head and neck, oesophageal and colorectal cancers. In 2019, 4.4% of cancers diagnosed globally and 401 000 cancer deaths were attributed to alcohol consumption.

Alcohol consumption also causes significant harm to others, not just to the person consuming alcohol. A significant part of alcohol-attributable disease burden arises from injuries such as road traffic accidents. In 2019, of a total of 298 000 deaths from alcohol-related road crashes, 156 000 deaths were caused by someone else’s drinking.

Other injuries, intentional or unintentional, include falls, drowning, burns, sexual assault, intimate partner violence and suicide.

A causal relationship has been established between alcohol use and the incidence or outcomes of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV.

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy increases the risk of having a child with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs), the most severe form of which is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which is associated with developmental disabilities and birth defects. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy can also increase the risk of pre-term birth complications including miscarriage, stillbirth and premature delivery.

Younger people are disproportionately negatively affected by alcohol consumption, with the highest proportion (13%) of alcohol-attributable deaths in 2019 occurring among people aged between 20 and 39 years.

In the long term, harmful and hazardous levels of alcohol consumption can lead to social problems including family problems, issues at work, financial problems, and unemployment.

Factors affecting alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm

There is no form of alcohol consumption that is risk-free. Even low levels of alcohol consumption carry some risks and can cause harm.

The level of risk depends on several factors, including the amount consumed, frequency of drinking, the health status of the individual, age, sex, and other personal characteristics, as well as the context in which alcohol consumption occurs.

Some groups and individuals who are vulnerable or at risk may have a higher susceptibility to the toxic, psychoactive and dependence-inducing properties of alcohol. On the other hand, individuals who adopt lower-risk patterns of alcohol consumption may not necessarily face a significantly increased likelihood of negative health and social consequences.

Societal factors which affect the levels and patterns of alcohol consumption and related problems include cultural and social norms, availability of alcohol, level of economic development, and implementation and enforcement of alcohol policies.

The impact of alcohol consumption on chronic and acute health outcomes is largely determined by the total volume of alcohol consumed and the pattern of drinking, particularly those patterns which are associated with the frequency of drinking and episodes of heavy drinking. Most alcohol related harms come from heavy episodic or heavy continuous alcohol consumption.

The context plays an important role in the occurrence of alcohol-related harm, particularly as a result of alcohol intoxication. Alcohol consumption can have an impact not only on the incidence of diseases, injuries and other health conditions, but also on their outcomes and how these evolve over time.

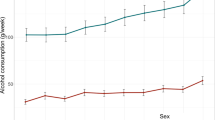

There are gender differences in both alcohol consumption and alcohol-related mortality and morbidity. In 2019, 52% of men were current drinkers, while only 35% of women had been drinking alcohol in the last 12 months. Alcohol per capita consumption was, on average, 8.2 litres for men compared to 2.2 litres for women. In 2019, alcohol use was responsible for 6.7% of all deaths among men and 2.4% of all deaths among women.

WHO response

The Global alcohol action plan 2022–2030, endorsed by WHO Member States, aims to reduce the harmful use of alcohol through effective, evidence-based strategies at national, regional and global levels. The plan outlines six key areas for action: high-impact strategies and interventions, advocacy and awareness, partnership and coordination, technical support and capacity-building, knowledge production and information systems, and resource mobilization.

Implementation of global strategy and action plan will accelerate global progress towards attaining alcohol-related targets under the Sustainable Development Goal 3.5 on strengthening the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol.

Achieving this will require global, regional and national actions on the levels, patterns and contexts of alcohol consumption and the wider social determinants of health, with a particular focus on implementing high-impact cost effective interventions.

It is vital to address the determinants that drive the acceptability, availability and affordability of alcohol consumption through cross-sectoral, comprehensive and integrated policy measures. It is also of critical importance to achieve universal health coverage for people living with alcohol use disorders and other health conditions due to alcohol use by strengthening health system responses and developing comprehensive and accessible systems of treatment and care that for those in need.

The SAFER initiative, launched in 2018 by WHO and partners, supports countries to implement the high-impact, cost-effective interventions proven to reduce the harm caused by alcohol consumption.

The WHO Global Information System on Alcohol and Health (GISAH) presents data on levels and patterns of alcohol consumption, alcohol-attributable health and social consequences and policy responses across the world.

Achieving a reduction in the harmful use of alcohol in line with the targets included in the Global alcohol action plan, the SDG 2030 agenda and the WHO Global monitoring framework for noncommunicable diseases, requires concerted action by countries and effective global governance.

Public policies and interventions to prevent and reduce alcohol-related harm should be guided and formulated by public health interests and based on clear public health goals and the best available evidence.

Engaging all relevant stakeholders is essential but the potential conflicts of interest, particularly with the alcohol industry, must be carefully assessed before engagement. Economic operators should refrain from activities that might prevent, delay or stop the development, enactment, implementation and enforcement of high-impact strategies and interventions to reduce the harmful use of alcohol.

By working together, with due diligence and protection from conflicts of interest, the negative health and social consequences of alcohol can be effectively reduced.

Global status report on alcohol and health and treatment of substance use disorders

Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol

Global Alcohol Action Plan 2022–2030

SAFER Alcohol Control Initiative

More on alcohol

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Nutrition and healthy eating

Alcohol use: Weighing risks and benefits

Drinking alcohol is a health risk regardless of the amount.

Research on alcohol suggests a sobering conclusion: Drinking alcohol in any amount carries a health risk. While the risk is low for moderate intake, the risk goes up as the amount you drink goes up.

Many people drink alcohol as a personal preference, during social activities, or as a part of cultural and religious practices. People who choose not to drink make that choice for the same reasons. Knowing your personal risk based on your habits can help you make the best decision for you.

The evidence for moderate alcohol use in healthy adults is still being studied. But good evidence shows that drinking high amounts of alcohol are clearly linked to health problems.

Here's a closer look at alcohol and health.

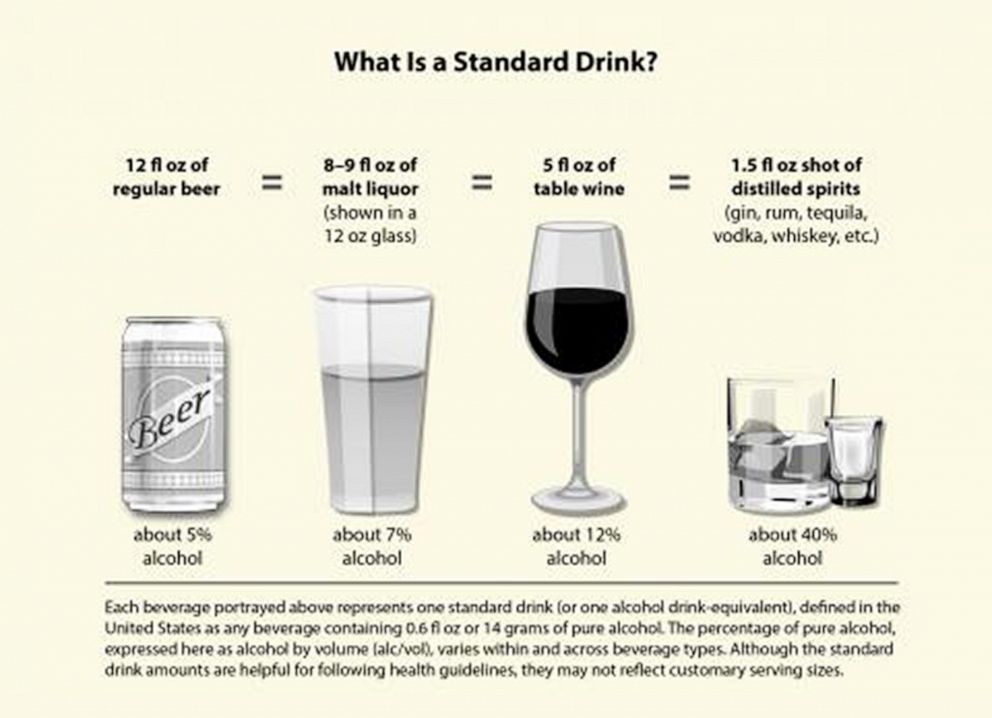

Defining moderate alcohol use

Moderate alcohol use may not mean the same thing in research studies or among health agencies.

In the United States, moderate drinking for healthy adults is different for men and women. It means on days when a person does drink, women do not have more than one drink and men do not have more than two drinks.

Examples of one drink include:

- 12 fluid ounces (355 milliliters) of regular beer

- 5 fluid ounces (148 milliliters) of wine

- 1.5 fluid ounces (44 milliliters) of hard liquor or distilled spirits

Health agencies outside the U.S. may define one drink differently.

The term "moderate" also may be used differently. For example, it may be used to define the risk of illness or injury based on the number of drinks a person has in a week.

Risks of moderate alcohol use

The bottom line is that alcohol is potentially addictive, can cause intoxication, and contributes to health problems and preventable deaths. If you already drink at low levels and continue to drink, risks for these issues appear to be low. But the risk is not zero.

For example, any amount of drinking increases the risk of breast cancer and colorectal cancer. As consumption goes up, the risk goes up for these cancers. It is a tiny, but real, increased risk.

Drinking also adds calories that can contribute to weight gain. And drinking raises the risk of problems in the digestive system.

In the past, moderate drinking was thought to be linked with a lower risk of dying from heart disease and possibly diabetes. After more analysis of the research, that doesn't seem to be the case. In general, a healthy diet and physical activity have much greater health benefits than alcohol and have been more extensively studied.

Risks of heavy alcohol use

Heavy drinking, including binge drinking, is a high-risk activity.

The definition of heavy drinking is based on a person's sex. For women, more than three drinks on any day or more than seven drinks a week is heavy drinking. For men, heavy drinking means more than four drinks on any day or more than 14 drinks a week.

Binge drinking is behavior that raises blood alcohol levels to 0.08%. That usually means four or more drinks within two hours for women and five or more drinks within two hours for men.

Heavy drinking can increase your risk of serious health problems, including:

- Certain cancers, such as colorectal cancer, breast cancer and cancers of the mouth, throat, esophagus and liver.

- Liver disease.

- Cardiovascular disease, such as high blood pressure and stroke.

Heavy drinking also has been linked to intentional injuries, such as suicide, as well as accidental injury and death.

During pregnancy, drinking may cause the unborn baby to have brain damage and other problems. Heavy drinking also may result in alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

When to avoid alcohol

In some situations, the risk of drinking any amount of alcohol is high. Avoid all alcohol if you:

- Are trying to get pregnant or are pregnant.

- Take medicine that has side effects if you drink alcohol.

- Have alcohol use disorder.

- Have medical issues that alcohol can worsen.

In the United States, people younger than age 21 are not legally able to drink alcohol.

When taking care of children, avoid alcohol. And the same goes for driving or if you need to be alert and able to react to changing situations.

Deciding about drinking

Lots of activities affect your health. Some are riskier than others. When it comes to alcohol, if you don't drink, don't start for health reasons.

Drinking moderately if you're otherwise healthy may be a risk you're willing to take. But heavy drinking carries a much higher risk even for those without other health concerns. Be sure to ask your healthcare professional about what's right for your health and safety.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Rethinking drinking: Alcohol and your health. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/. Accessed Jan. 8, 2024.

- 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov. Accessed Jan. 8, 2024.

- Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Alcoholic beverages. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/2020-advisory-committee-report. Accessed Jan. 8, 2024.

- Canada's guidance on alcohol and health. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. https://www.ccsa.ca/canadas-guidance-alcohol-and-health. Accessed Jan. 9, 2024.

- Science around moderate alcohol consumption. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/moderate-drinking.htm. Accessed Jan. 9, 2024.

- Alcohol use and your health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm. Accessed Jan. 9, 2024.

Products and Services

- Available Health Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diet Bundle

- The Mayo Clinic Diet Online

- A Book: Live Younger Longer

- A Book: Cook Smart, Eat Well

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on High Blood Pressure

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

- Health foods

- Alkaline water

- Artificial sweeteners and other sugar substitutes

- Autism spectrum disorder and digestive symptoms

- Breastfeeding nutrition: Tips for moms

- Caffeine: How much is too much?

- Is caffeine dehydrating?

- Calorie calculator

- Can whole-grain foods lower blood pressure?

- Carbohydrates

- Chart of high-fiber foods

- Cholesterol: Top foods to improve your numbers

- Coconut water: Is it super hydrating?

- Coffee and health

- Diet soda: How much is too much?

- Dietary fats

- Dietary fiber

- Prickly pear cactus

- Does soy really affect breast cancer risk?

- Don't get tricked by these 3 heart-health myths

- High-protein diets

- How to track saturated fat

- Is there a special diet for Crohn's disease?

- Monosodium glutamate (MSG)

- Nuts and your heart: Eating nuts for heart health

- Omega-3 in fish

- Omega-6 fatty acids

- Phenylalanine

- Portion control

- Taurine in energy drinks

- Underweight: Add pounds healthfully

- Daily water requirement

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Alcohol use Weighing risks and benefits

5X Challenge

Thanks to generous benefactors, your gift today can have 5X the impact to advance AI innovation at Mayo Clinic.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 June 2023

Alcohol consumption and risks of more than 200 diseases in Chinese men

- Pek Kei Im ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2624-9766 1 ,

- Neil Wright ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3946-1870 1 ,

- Ling Yang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5750-6588 1 , 2 ,

- Ka Hung Chan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3700-502X 1 , 3 ,

- Yiping Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4973-0296 1 , 2 ,

- Huaidong Du ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9814-0049 1 , 2 ,

- Xiaoming Yang 1 ,

- Daniel Avery ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9823-9575 1 ,

- Shaojie Wang 5 ,

- Canqing Yu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0019-0014 6 , 7 ,

- Jun Lv 6 , 7 ,

- Robert Clarke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9802-8241 1 ,

- Junshi Chen 8 ,

- Rory Collins 1 ,

- Robin G. Walters ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9179-0321 1 , 2 ,

- Richard Peto 1 ,

- Liming Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5873-7089 6 , 7 na1 ,

- Zhengming Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6423-105X 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Iona Y. Millwood ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0807-0682 1 , 2 na1 &

China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group

Nature Medicine volume 29 , pages 1476–1486 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

25 Citations

824 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Genetics research

- Risk factors

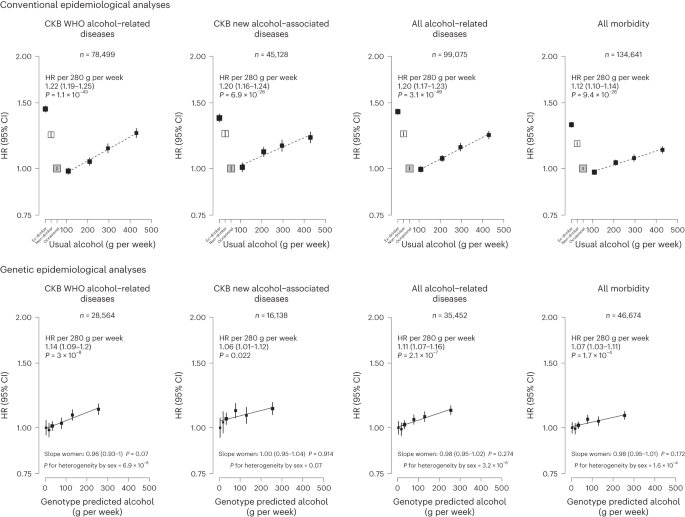

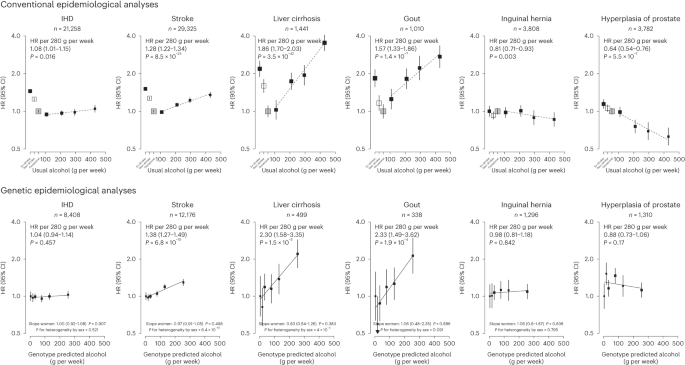

Alcohol consumption accounts for ~3 million annual deaths worldwide, but uncertainty persists about its relationships with many diseases. We investigated the associations of alcohol consumption with 207 diseases in the 12-year China Kadoorie Biobank of >512,000 adults (41% men), including 168,050 genotyped for ALDH2 - rs671 and ADH1B - rs1229984 , with >1.1 million ICD-10 coded hospitalized events. At baseline, 33% of men drank alcohol regularly. Among men, alcohol intake was positively associated with 61 diseases, including 33 not defined by the World Health Organization as alcohol-related, such as cataract ( n = 2,028; hazard ratio 1.21; 95% confidence interval 1.09–1.33, per 280 g per week) and gout ( n = 402; 1.57, 1.33–1.86). Genotype-predicted mean alcohol intake was positively associated with established ( n = 28,564; 1.14, 1.09–1.20) and new alcohol-associated ( n = 16,138; 1.06, 1.01–1.12) diseases, and with specific diseases such as liver cirrhosis ( n = 499; 2.30, 1.58–3.35), stroke ( n = 12,176; 1.38, 1.27–1.49) and gout ( n = 338; 2.33, 1.49–3.62), but not ischemic heart disease ( n = 8,408; 1.04, 0.94–1.14). Among women, 2% drank alcohol resulting in low power to assess associations of self-reported alcohol intake with disease risks, but genetic findings in women suggested the excess male risks were not due to pleiotropic genotypic effects. Among Chinese men, alcohol consumption increased multiple disease risks, highlighting the need to strengthen preventive measures to reduce alcohol intake.

Similar content being viewed by others

A burden of proof study on alcohol consumption and ischemic heart disease

Effect of alcohol consumption on kidney function: population-based cohort study

Genomic prediction of alcohol-related morbidity and mortality

Alcohol consumption is a major risk factor for poor physical and mental health, accounting for about 3 million deaths and over 130 million disability-adjusted life years worldwide in 2016 (ref. 1 ). Since the 1990s, alcohol consumption has increased in many low- and middle-income countries, including China, where it almost exclusively involves men 2 , 3 . Among Chinese men, those who reported alcohol consumption in the past 12 months increased from 59% to 85% and yearly per-capita alcohol consumption increased from 7.1 to 11.2 l between 1990 and 2017 and these have been predicted to increase in future years 2 .

Previous epidemiological studies conducted in mainly western populations have provided consistent evidence about the hazards of alcohol drinking for several major diseases, including several types of cancers and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), liver cirrhosis, infectious diseases (for example tuberculosis and pneumonia) and injuries 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 . Large western cohort studies with linkage to hospital records have also investigated the associations of alcohol with risks of several less-common or non-fatal disease outcomes (for example certain site-specific cancers 10 , 11 , 12 , dementia 13 , falls 14 and cataract surgery 15 ). For some (for example stomach cancer), there was suggestive evidence of weak positive associations with heavy drinking 10 , 11 , whereas for others (for example cataract) the limited available evidence has been contradictory 10 , 12 , 13 , 15 ; however, the evidence from western populations, even for diseases known to be associated with alcohol, may not be generalizable to Chinese populations, where the prevalence and types of alcohol drinking (mainly spirits), patterns of diseases (for example high stroke rates) and differences in the ability to metabolize alcohol 8 , 9 , 16 differ markedly from those in western populations 4 , 17 .

For many diseases, including those considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) 4 to be alcohol-related (for example ischemic heart disease (IHD) and diabetes), uncertainty remains about the causal relevance of these associations, which can be assessed in genetic studies using a Mendelian randomization (MR) approach 18 . In such studies, genetic variants can be used as instruments for alcohol consumption to investigate the potential causal relevance of alcohol drinking for diseases, which can limit the biases of confounding and reverse causality common in conventional observational studies 18 . Such studies are particularly informative in East Asian populations where two common genetic variants ( ALDH2 - rs671 and ADH1B - rs1229984 ), which are both rare in western populations, greatly alter alcohol metabolism and strongly affect alcohol intake 19 . Several studies have explored the causal relevance of alcohol consumption with CVD risk factors and morbidity 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 and cancer 16 using these genetic variants, yet findings remain inconclusive for certain diseases (for example IHD) and evidence for other diseases is sparse.

To address these questions, we conducted analyses using observational and genetic approaches to evaluate the associations between alcohol consumption and the risks of a wide range of disease outcomes in the prospective China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB).

Among the 512,724 participants (Supplementary Fig. 1 ), the mean age at baseline was 52 (s.d. 10.7) years, 41% were men and 56% lived in rural areas. Among men, 33% reported drinking alcohol regularly (at least once a week) at baseline (current drinkers), consuming on average 286 g of alcohol per week, mainly from spirits (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 ). Non-drinkers and ex-drinkers were older and more likely to report poor self-rated health or previous chronic diseases, compared to occasional or current drinkers (Table 1 ). Compared to moderate drinkers (<140 g per week), heavier drinkers were more likely to be rural residents, had received lower education and had more unhealthy lifestyle factors (for example smoking and infrequent fresh fruit intake), higher mean blood pressure and longer duration of drinking (Supplementary Table 3 ). Among male current drinkers, 62% reported drinking daily and 37% engaging in heavy episodic drinking (Supplementary Table 2 ). Among women, only 2% drank alcohol at least weekly (mean intake 116 g per week), but there were similar associations with other baseline characteristics (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 ) compared to those in men.

During a median of 12.1 (interquartile range 11.1–13.1) years of follow-up, 134,641 men (44,027 drinkers) and 198,430 women (4,420 drinkers) experienced at least one reported hospitalization event or death at age-at-risk 35–84 years, involving a total of 1,111,495 hospitalization episodes. Among men, there were 333,541 (107,857 in current drinkers) recorded events from 207 diseases across 17 International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision (ICD-10) chapters studied that had at least 80 cases each among current drinkers (Table 2 ), while among women there were 476,986 (11,773) events from 48 diseases across 18 ICD-10 chapters (Supplementary Table 5 ).

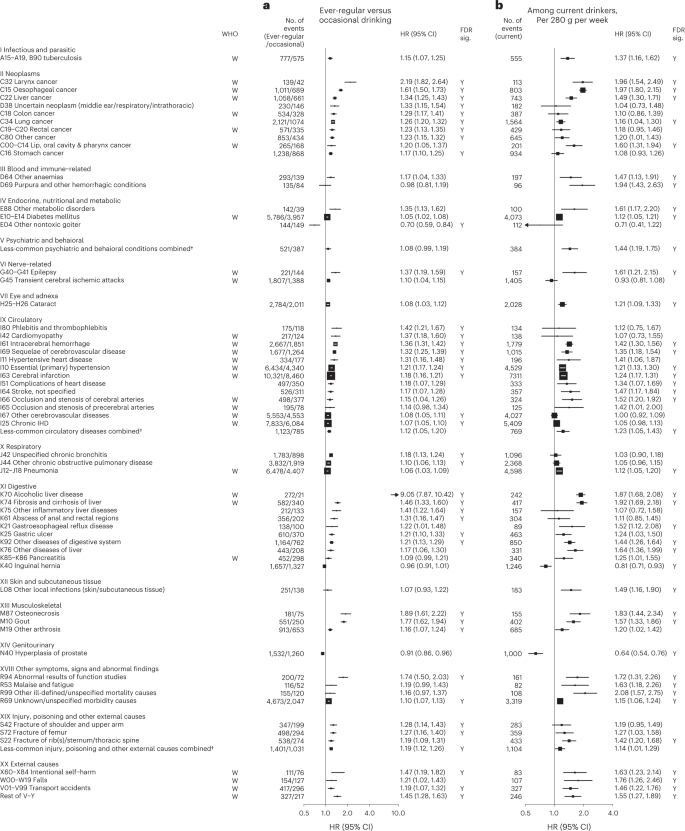

Observational associations of alcohol with disease risks

Among men, alcohol drinking was significantly associated with higher risks of 61 disease outcomes from 15 ICD-10 chapters based on two separate analyses, (1) comparing ever-regular versus occasional drinkers and (2) dose–response among current drinkers (Table 2 and Extended Data Fig. 1 ). In each of the analyses in men, there were significant associations of alcohol consumption with 42 diseases (or outcomes), of which 23 were significant in both analyses and the remainder were directionally consistent with one exception (transient cerebral ischemic attacks, ICD-10 code G45) (Fig. 1 ). In further analyses covering all alcohol consumption categories, there were typical U-shaped or J-shaped associations, with excess risks in male ex-drinkers and non-drinkers compared to occasional or moderate drinkers for most of these diseases (Supplementary Table 6 ). Among male ex-drinkers, the overall excess morbidity risks were more considerable for alcohol-associated diseases than for other diseases, but these excess risks were lower with increasing duration after stopping drinking (Extended Data Fig. 2 ).

Cox models ( a ) comparing ever-regular drinkers with occasional drinkers or ( b ) assessing the dose–response per 280 g per week higher usual alcohol intake within current drinkers, were stratified by age at risk and study area and were adjusted for education and smoking. Each solid square represents HR with the area inversely proportional to the variance of the log HR. The horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs. Diseases considered to be alcohol-related by the WHO are indicated with ‘W’ under the ‘WHO’ column. The individual diseases listed included all that showed FDR-adjusted significant associations with alcohol (FDR-adjusted P < 0.05, indicated with ‘Y’ under the ‘FDR sig.’ column) and WHO alcohol-related diseases that showed nominally significant associations with alcohol ( P < 0.05). All P values are two-sided. † Included less-common ICD-10 codes within the corresponding ICD-10 chapter that were not individually investigated in the present study. ‘Less-common psychiatric and behavioral conditions’ consisted of ICD-10 codes F00–F99, excluding F32, F33 and F99. ‘Less-common circulatory diseases’ consisted of ICD-10 codes I00–I99, excluding I10, I11, I20, I21, I24, I25, I27, I42, I46, I48–I51, I60–I67, I69, I70, I80 and I83. ‘Less-common injury, poisoning and other external causes’ consisted of ICD-10 codes S00–T98, excluding S06, S09, S22, S32, S42, S52, S62, S72, S82, S92 and T14.

Of the 61 diseases positively associated with alcohol intake in male participants, 28 were considered by the WHO to be alcohol-related diseases, including tuberculosis (A15–A19 and B90), six site-specific cancers including cancers in the larynx (C32), esophagus (C15), liver (C22), colon (C18), rectum (C19 and C20) and lips, oral cavity and pharynx (C00–C14), diabetes (E10–E14), epilepsy (G40 and G41), several hypertensive diseases (I10 and I11) and cerebrovascular diseases (I61, I63, I65, I66, I67, I69 and G45), chronic IHD (I25), cardiomyopathy (I42), pneumonia (J12–J18), alcoholic liver disease (K70) and liver cirrhosis (K74), pancreatitis (K85 and K86) and external causes including self-harm (X60–X84), falls (W00–W19), transport accidents (V01–V99) and other external causes (rest of V–Y) (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 3 ). Of these 28 diseases, 22 showed significant dose–response associations with alcohol intake. The hazard ratios (HRs) per 280 g per week higher intake for the aggregated WHO alcohol-related diseases were 1.22 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.19–1.25) (Supplementary Table 7 for detailed outcome classification), ranging from 1.12 (1.05–1.20) for pneumonia to 1.97 (1.80–2.15) for esophageal cancer.

The 33 other diseases showing false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted significant positive associations with alcohol drinking in men included lung (C34) and stomach (C16) cancers, cataract (H25 and H26), six digestive diseases such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (K21) and gastric ulcer (K25), three musculoskeletal conditions, including gout (M10), three fracture types (S22, S42 and S72), and the aggregates of less-common psychiatric and behavioral conditions and circulatory diseases (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 4 ). Of these 33 diseases, 22 showed significant dose–response associations, with HRs per 280 g per week higher intake ranging from 1.16 (95% CI 1.04–1.30) for lung cancer to 1.94 (1.43–2.63) for purpura and other hemorrhagic conditions (D69) and 1.20 (1.16–1.24) for the aggregated CKB new alcohol-associated diseases. In contrast, three diseases showed FDR-adjusted significant inverse associations with alcohol drinking (other nontoxic goiter (E04), hyperplasia of prostate (N40) and inguinal hernia (K40)). Overall, for all-cause morbidity, the HR per 280 g per week higher intake was 1.12 (1.10–1.14) in male current drinkers.

Supplementary Figs. 2 – 4 show the dose–response associations for all disease outcomes investigated in male current drinkers. For alcohol-associated diseases and for total morbidity, the dose–response associations were unaltered after additional covariate adjustments or excluding participants with poor baseline health conditions (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 8 ). Moreover, the associations were similar across various male population subgroups, but seemed to be stronger in younger men, urban residents and higher socioeconomic groups for new alcohol-associated diseases (Supplementary Fig. 6 ).

Among male current drinkers, drinking daily, heavy episodic drinking and drinking spirits were each associated with higher risks for alcohol-related diseases, but most of these associations were attenuated to the null after adjusting for total alcohol intake (Extended Data Fig. 5 ); however, for a given total alcohol intake among male current drinkers, drinking daily was associated with 30–40% higher risks of alcohol-related cancers (1.30, 1.17–1.45) and liver cirrhosis (1.39, 1.13–1.72), compared to non-daily drinking. Similarly, heavy episodic drinking was associated with higher risks of diabetes (1.23, 1.12–1.34) and IHD (1.11, 1.03–1.19), whereas drinking outside of meals was associated with 49% (1.49, 1.19–1.86) higher risk of liver cirrhosis than drinking with meals. The risks of all major alcohol-associated diseases were higher with longer duration of alcohol consumption in men (Extended Data Fig. 6 ).

Among women, due to few reported current drinkers there was a lack of statistical power to detect any associations of self-reported alcohol intake with disease risks (Supplementary Table 5 , Extended Data Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 7 ).

Genetic associations of alcohol with disease risks

A genetic instrument for alcohol intake was derived using ALDH2 - rs671 (G > A) and ADH1B - rs1229984 (G > A) genotypes. The overall A-allele frequency was 0.21 for ALDH2 - rs671 and 0.69 for ADH1B - rs1229984 , with both A-alleles being more common in southern than northern study areas (Supplementary Table 9 ). Both ALDH2 - rs671 and, to a lesser extent, ADH1B - rs1229984 were strongly associated with alcohol drinking in men, but much less so in women (Supplementary Table 10 ). In men, the derived genetic instrument predicted a >60-fold difference (range 4–255 g per week, C1 to C6) in mean alcohol intake, whereas in women mean alcohol intake remained low (<10 g per week) across genetic categories (Supplementary Table 11 ). Both variants and the derived instrument were not associated with smoking or other major self-reported baseline characteristics, except for a small difference in fresh fruit intake by ALDH2 - rs671 genotype in men.

Among men, genotype-predicted mean alcohol intake was positively associated with higher risks of CKB WHO alcohol-related (HR per 280 g per week higher genotype-predicted mean male alcohol intake: 1.14, 95% CI 1.09–1.20) and CKB new alcohol-associated (1.06, 1.01–1.12) diseases (Fig. 2 ), both of which were slightly weaker than the conventional associations. For certain diseases, however, the genetic associations were stronger, with HRs of 1.38 (1.27–1.49) for stroke, 2.30 (1.58–3.35) for liver cirrhosis and 2.33 (1.49–3.62) for gout, in men (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 8 ). For individual genetic variants, the associations were directionally consistent (Extended Data Figs. 9 and 10 ). Conversely, there were no significant dose–response genotypic associations with IHD, inguinal hernia or hyperplasia of prostate in men. For other alcohol-associated diseases, higher genotype-predicted mean male alcohol intake was significantly associated with higher risks of esophageal cancer, cataract, occlusion and stenosis of cerebral arteries, sequelae of cerebrovascular disease, essential primary hypertension and fractures of ribs, sternum or thoracic spine. There were also suggestive positive genotypic associations with several digestive tract cancer types (liver, colon and stomach) and circulatory and digestive diseases, and significant inverse associations with lung cancer and other chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (J44) in men (Extended Data Figs. 8 – 10 ). Sensitivity analyses using different analytical methods to adjust for confounding by study area, or a two-stage least-squares MR approach, did not alter the main genetic findings in men (Supplementary Table 12 ). In contrast, genotypes that increased alcohol intake in men were not adversely associated with most alcohol-related disease risks among women (for example HR 1.00 (0.97–1.04) for all morbidity among female non-drinkers; Supplementary Fig. 7 and Extended Data Figs. 8 – 10 ).

Each box represents HR with the area inversely proportional to the variance of the group-specific log hazard within subplot. The vertical lines indicate group-specific 95% CIs. Conventional epidemiological analyses relate self-reported drinking patterns to risks of diseases (reference group is occasional drinkers), using Cox models stratified by age at risk and study area and adjusted for education and smoking. Within current drinkers, HRs were plotted against usual alcohol intake and were calculated per 280 g per week higher usual alcohol intake. Genetic epidemiological analyses relate genetic categories to risks of diseases (reference group is the genotype group with lowest genotype-predicted mean male alcohol intake), using Cox models stratified by age at risk and study area and adjusted for genomic principal components. The HR per 280 g per week higher genotype-predicted mean male alcohol intake was calculated from the inverse-variance-weighted mean of the slopes of the fitted lines in each study area. The corresponding slopes in women were summarized in text and the slopes of the fitted line by sex were compared and assessed for heterogeneity using chi-squared tests (indicated by P for heterogeneity by sex). All P values are two-sided. Analyses of these aggregated outcomes were based on first recorded event of the aggregate during follow-up and participants may have had multiple events of different types of diseases. ‘All alcohol-related diseases’ includes the first recorded event from ‘CKB WHO alcohol-related diseases’ or ‘CKB new alcohol-associated diseases’ during follow-up.

Each box represents HR with the area inversely proportional to the variance of the group-specific log hazard within subplot. The vertical lines indicate group-specific 95% CIs. Conventional epidemiological analyses relate self-reported drinking patterns to risks of diseases (reference group is occasional drinkers), using Cox models stratified by age at risk and study area and adjusted for education and smoking. Within current drinkers, HRs were plotted against usual alcohol intake and were calculated per 280 g per week higher usual alcohol intake. Genetic epidemiological analyses relate genetic categories to risks of diseases (reference group is the genotype group with lowest genotype-predicted mean male alcohol intake), using Cox models stratified by age at risk and study area and adjusted for genomic principal components. The HR per 280 g per week higher genotype-predicted mean male alcohol intake was calculated from the inverse-variance-weighted mean of the slopes of the fitted lines in each study area. The corresponding slopes in women were summarized in text and the slopes of the fitted line by sex were compared and assessed for heterogeneity using chi-squared tests (indicated by P for heterogeneity by sex). All P values are two-sided. Corresponding ICD-10 codes, IHD (I20–I25); stroke (I60, I61, I63 and I64); liver cirrhosis (K70 and K74); gout (M10); inguinal hernia (K40); hyperplasia of prostate (N40).

Hospitalizations associated with alcohol drinking