Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Qualitative Data Analysis

23 Presenting the Results of Qualitative Analysis

Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur

Qualitative research is not finished just because you have determined the main findings or conclusions of your study. Indeed, disseminating the results is an essential part of the research process. By sharing your results with others, whether in written form as scholarly paper or an applied report or in some alternative format like an oral presentation, an infographic, or a video, you ensure that your findings become part of the ongoing conversation of scholarship in your field, forming part of the foundation for future researchers. This chapter provides an introduction to writing about qualitative research findings. It will outline how writing continues to contribute to the analysis process, what concerns researchers should keep in mind as they draft their presentations of findings, and how best to organize qualitative research writing

As you move through the research process, it is essential to keep yourself organized. Organizing your data, memos, and notes aids both the analytical and the writing processes. Whether you use electronic or physical, real-world filing and organizational systems, these systems help make sense of the mountains of data you have and assure you focus your attention on the themes and ideas you have determined are important (Warren and Karner 2015). Be sure that you have kept detailed notes on all of the decisions you have made and procedures you have followed in carrying out research design, data collection, and analysis, as these will guide your ultimate write-up.

First and foremost, researchers should keep in mind that writing is in fact a form of thinking. Writing is an excellent way to discover ideas and arguments and to further develop an analysis. As you write, more ideas will occur to you, things that were previously confusing will start to make sense, and arguments will take a clear shape rather than being amorphous and poorly-organized. However, writing-as-thinking cannot be the final version that you share with others. Good-quality writing does not display the workings of your thought process. It is reorganized and revised (more on that later) to present the data and arguments important in a particular piece. And revision is totally normal! No one expects the first draft of a piece of writing to be ready for prime time. So write rough drafts and memos and notes to yourself and use them to think, and then revise them until the piece is the way you want it to be for sharing.

Bergin (2018) lays out a set of key concerns for appropriate writing about research. First, present your results accurately, without exaggerating or misrepresenting. It is very easy to overstate your findings by accident if you are enthusiastic about what you have found, so it is important to take care and use appropriate cautions about the limitations of the research. You also need to work to ensure that you communicate your findings in a way people can understand, using clear and appropriate language that is adjusted to the level of those you are communicating with. And you must be clear and transparent about the methodological strategies employed in the research. Remember, the goal is, as much as possible, to describe your research in a way that would permit others to replicate the study. There are a variety of other concerns and decision points that qualitative researchers must keep in mind, including the extent to which to include quantification in their presentation of results, ethics, considerations of audience and voice, and how to bring the richness of qualitative data to life.

Quantification, as you have learned, refers to the process of turning data into numbers. It can indeed be very useful to count and tabulate quantitative data drawn from qualitative research. For instance, if you were doing a study of dual-earner households and wanted to know how many had an equal division of household labor and how many did not, you might want to count those numbers up and include them as part of the final write-up. However, researchers need to take care when they are writing about quantified qualitative data. Qualitative data is not as generalizable as quantitative data, so quantification can be very misleading. Thus, qualitative researchers should strive to use raw numbers instead of the percentages that are more appropriate for quantitative research. Writing, for instance, “15 of the 20 people I interviewed prefer pancakes to waffles” is a simple description of the data; writing “75% of people prefer pancakes” suggests a generalizable claim that is not likely supported by the data. Note that mixing numbers with qualitative data is really a type of mixed-methods approach. Mixed-methods approaches are good, but sometimes they seduce researchers into focusing on the persuasive power of numbers and tables rather than capitalizing on the inherent richness of their qualitative data.

A variety of issues of scholarly ethics and research integrity are raised by the writing process. Some of these are unique to qualitative research, while others are more universal concerns for all academic and professional writing. For example, it is essential to avoid plagiarism and misuse of sources. All quotations that appear in a text must be properly cited, whether with in-text and bibliographic citations to the source or with an attribution to the research participant (or the participant’s pseudonym or description in order to protect confidentiality) who said those words. Where writers will paraphrase a text or a participant’s words, they need to make sure that the paraphrase they develop accurately reflects the meaning of the original words. Thus, some scholars suggest that participants should have the opportunity to read (or to have read to them, if they cannot read the text themselves) all sections of the text in which they, their words, or their ideas are presented to ensure accuracy and enable participants to maintain control over their lives.

Audience and Voice

When writing, researchers must consider their audience(s) and the effects they want their writing to have on these audiences. The designated audience will dictate the voice used in the writing, or the individual style and personality of a piece of text. Keep in mind that the potential audience for qualitative research is often much more diverse than that for quantitative research because of the accessibility of the data and the extent to which the writing can be accessible and interesting. Yet individual pieces of writing are typically pitched to a more specific subset of the audience.

Let us consider one potential research study, an ethnography involving participant-observation of the same children both when they are at daycare facility and when they are at home with their families to try to understand how daycare might impact behavior and social development. The findings of this study might be of interest to a wide variety of potential audiences: academic peers, whether at your own academic institution, in your broader discipline, or multidisciplinary; people responsible for creating laws and policies; practitioners who run or teach at day care centers; and the general public, including both people who are interested in child development more generally and those who are themselves parents making decisions about child care for their own children. And the way you write for each of these audiences will be somewhat different. Take a moment and think through what some of these differences might look like.

If you are writing to academic audiences, using specialized academic language and working within the typical constraints of scholarly genres, as will be discussed below, can be an important part of convincing others that your work is legitimate and should be taken seriously. Your writing will be formal. Even if you are writing for students and faculty you already know—your classmates, for instance—you are often asked to imitate the style of academic writing that is used in publications, as this is part of learning to become part of the scholarly conversation. When speaking to academic audiences outside your discipline, you may need to be more careful about jargon and specialized language, as disciplines do not always share the same key terms. For instance, in sociology, scholars use the term diffusion to refer to the way new ideas or practices spread from organization to organization. In the field of international relations, scholars often used the term cascade to refer to the way ideas or practices spread from nation to nation. These terms are describing what is fundamentally the same concept, but they are different terms—and a scholar from one field might have no idea what a scholar from a different field is talking about! Therefore, while the formality and academic structure of the text would stay the same, a writer with a multidisciplinary audience might need to pay more attention to defining their terms in the body of the text.

It is not only other academic scholars who expect to see formal writing. Policymakers tend to expect formality when ideas are presented to them, as well. However, the content and style of the writing will be different. Much less academic jargon should be used, and the most important findings and policy implications should be emphasized right from the start rather than initially focusing on prior literature and theoretical models as you might for an academic audience. Long discussions of research methods should also be minimized. Similarly, when you write for practitioners, the findings and implications for practice should be highlighted. The reading level of the text will vary depending on the typical background of the practitioners to whom you are writing—you can make very different assumptions about the general knowledge and reading abilities of a group of hospital medical directors with MDs than you can about a group of case workers who have a post-high-school certificate. Consider the primary language of your audience as well. The fact that someone can get by in spoken English does not mean they have the vocabulary or English reading skills to digest a complex report. But the fact that someone’s vocabulary is limited says little about their intellectual abilities, so try your best to convey the important complexity of the ideas and findings from your research without dumbing them down—even if you must limit your vocabulary usage.

When writing for the general public, you will want to move even further towards emphasizing key findings and policy implications, but you also want to draw on the most interesting aspects of your data. General readers will read sociological texts that are rich with ethnographic or other kinds of detail—it is almost like reality television on a page! And this is a contrast to busy policymakers and practitioners, who probably want to learn the main findings as quickly as possible so they can go about their busy lives. But also keep in mind that there is a wide variation in reading levels. Journalists at publications pegged to the general public are often advised to write at about a tenth-grade reading level, which would leave most of the specialized terminology we develop in our research fields out of reach. If you want to be accessible to even more people, your vocabulary must be even more limited. The excellent exercise of trying to write using the 1,000 most common English words, available at the Up-Goer Five website ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ) does a good job of illustrating this challenge (Sanderson n.d.).

Another element of voice is whether to write in the first person. While many students are instructed to avoid the use of the first person in academic writing, this advice needs to be taken with a grain of salt. There are indeed many contexts in which the first person is best avoided, at least as long as writers can find ways to build strong, comprehensible sentences without its use, including most quantitative research writing. However, if the alternative to using the first person is crafting a sentence like “it is proposed that the researcher will conduct interviews,” it is preferable to write “I propose to conduct interviews.” In qualitative research, in fact, the use of the first person is far more common. This is because the researcher is central to the research project. Qualitative researchers can themselves be understood as research instruments, and thus eliminating the use of the first person in writing is in a sense eliminating information about the conduct of the researchers themselves.

But the question really extends beyond the issue of first-person or third-person. Qualitative researchers have choices about how and whether to foreground themselves in their writing, not just in terms of using the first person, but also in terms of whether to emphasize their own subjectivity and reflexivity, their impressions and ideas, and their role in the setting. In contrast, conventional quantitative research in the positivist tradition really tries to eliminate the author from the study—which indeed is exactly why typical quantitative research avoids the use of the first person. Keep in mind that emphasizing researchers’ roles and reflexivity and using the first person does not mean crafting articles that provide overwhelming detail about the author’s thoughts and practices. Readers do not need to hear, and should not be told, which database you used to search for journal articles, how many hours you spent transcribing, or whether the research process was stressful—save these things for the memos you write to yourself. Rather, readers need to hear how you interacted with research participants, how your standpoint may have shaped the findings, and what analytical procedures you carried out.

Making Data Come Alive

One of the most important parts of writing about qualitative research is presenting the data in a way that makes its richness and value accessible to readers. As the discussion of analysis in the prior chapter suggests, there are a variety of ways to do this. Researchers may select key quotes or images to illustrate points, write up specific case studies that exemplify their argument, or develop vignettes (little stories) that illustrate ideas and themes, all drawing directly on the research data. Researchers can also write more lengthy summaries, narratives, and thick descriptions.

Nearly all qualitative work includes quotes from research participants or documents to some extent, though ethnographic work may focus more on thick description than on relaying participants’ own words. When quotes are presented, they must be explained and interpreted—they cannot stand on their own. This is one of the ways in which qualitative research can be distinguished from journalism. Journalism presents what happened, but social science needs to present the “why,” and the why is best explained by the researcher.

So how do authors go about integrating quotes into their written work? Julie Posselt (2017), a sociologist who studies graduate education, provides a set of instructions. First of all, authors need to remain focused on the core questions of their research, and avoid getting distracted by quotes that are interesting or attention-grabbing but not so relevant to the research question. Selecting the right quotes, those that illustrate the ideas and arguments of the paper, is an important part of the writing process. Second, not all quotes should be the same length (just like not all sentences or paragraphs in a paper should be the same length). Include some quotes that are just phrases, others that are a sentence or so, and others that are longer. We call longer quotes, generally those more than about three lines long, block quotes , and they are typically indented on both sides to set them off from the surrounding text. For all quotes, be sure to summarize what the quote should be telling or showing the reader, connect this quote to other quotes that are similar or different, and provide transitions in the discussion to move from quote to quote and from topic to topic. Especially for longer quotes, it is helpful to do some of this writing before the quote to preview what is coming and other writing after the quote to make clear what readers should have come to understand. Remember, it is always the author’s job to interpret the data. Presenting excerpts of the data, like quotes, in a form the reader can access does not minimize the importance of this job. Be sure that you are explaining the meaning of the data you present.

A few more notes about writing with quotes: avoid patchwriting, whether in your literature review or the section of your paper in which quotes from respondents are presented. Patchwriting is a writing practice wherein the author lightly paraphrases original texts but stays so close to those texts that there is little the author has added. Sometimes, this even takes the form of presenting a series of quotes, properly documented, with nothing much in the way of text generated by the author. A patchwriting approach does not build the scholarly conversation forward, as it does not represent any kind of new contribution on the part of the author. It is of course fine to paraphrase quotes, as long as the meaning is not changed. But if you use direct quotes, do not edit the text of the quotes unless how you edit them does not change the meaning and you have made clear through the use of ellipses (…) and brackets ([])what kinds of edits have been made. For example, consider this exchange from Matthew Desmond’s (2012:1317) research on evictions:

The thing was, I wasn’t never gonna let Crystal come and stay with me from the get go. I just told her that to throw her off. And she wasn’t fittin’ to come stay with me with no money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

A paraphrase of this exchange might read “She said that she was going to let Crystal stay with her if Crystal did not have any money.” Paraphrases like that are fine. What is not fine is rewording the statement but treating it like a quote, for instance writing:

The thing was, I was not going to let Crystal come and stay with me from beginning. I just told her that to throw her off. And it was not proper for her to come stay with me without any money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

But as you can see, the change in language and style removes some of the distinct meaning of the original quote. Instead, writers should leave as much of the original language as possible. If some text in the middle of the quote needs to be removed, as in this example, ellipses are used to show that this has occurred. And if a word needs to be added to clarify, it is placed in square brackets to show that it was not part of the original quote.

Data can also be presented through the use of data displays like tables, charts, graphs, diagrams, and infographics created for publication or presentation, as well as through the use of visual material collected during the research process. Note that if visuals are used, the author must have the legal right to use them. Photographs or diagrams created by the author themselves—or by research participants who have signed consent forms for their work to be used, are fine. But photographs, and sometimes even excerpts from archival documents, may be owned by others from whom researchers must get permission in order to use them.

A large percentage of qualitative research does not include any data displays or visualizations. Therefore, researchers should carefully consider whether the use of data displays will help the reader understand the data. One of the most common types of data displays used by qualitative researchers are simple tables. These might include tables summarizing key data about cases included in the study; tables laying out the characteristics of different taxonomic elements or types developed as part of the analysis; tables counting the incidence of various elements; and 2×2 tables (two columns and two rows) illuminating a theory. Basic network or process diagrams are also commonly included. If data displays are used, it is essential that researchers include context and analysis alongside data displays rather than letting them stand by themselves, and it is preferable to continue to present excerpts and examples from the data rather than just relying on summaries in the tables.

If you will be using graphs, infographics, or other data visualizations, it is important that you attend to making them useful and accurate (Bergin 2018). Think about the viewer or user as your audience and ensure the data visualizations will be comprehensible. You may need to include more detail or labels than you might think. Ensure that data visualizations are laid out and labeled clearly and that you make visual choices that enhance viewers’ ability to understand the points you intend to communicate using the visual in question. Finally, given the ease with which it is possible to design visuals that are deceptive or misleading, it is essential to make ethical and responsible choices in the construction of visualization so that viewers will interpret them in accurate ways.

The Genre of Research Writing

As discussed above, the style and format in which results are presented depends on the audience they are intended for. These differences in styles and format are part of the genre of writing. Genre is a term referring to the rules of a specific form of creative or productive work. Thus, the academic journal article—and student papers based on this form—is one genre. A report or policy paper is another. The discussion below will focus on the academic journal article, but note that reports and policy papers follow somewhat different formats. They might begin with an executive summary of one or a few pages, include minimal background, focus on key findings, and conclude with policy implications, shifting methods and details about the data to an appendix. But both academic journal articles and policy papers share some things in common, for instance the necessity for clear writing, a well-organized structure, and the use of headings.

So what factors make up the genre of the academic journal article in sociology? While there is some flexibility, particularly for ethnographic work, academic journal articles tend to follow a fairly standard format. They begin with a “title page” that includes the article title (often witty and involving scholarly inside jokes, but more importantly clearly describing the content of the article); the authors’ names and institutional affiliations, an abstract , and sometimes keywords designed to help others find the article in databases. An abstract is a short summary of the article that appears both at the very beginning of the article and in search databases. Abstracts are designed to aid readers by giving them the opportunity to learn enough about an article that they can determine whether it is worth their time to read the complete text. They are written about the article, and thus not in the first person, and clearly summarize the research question, methodological approach, main findings, and often the implications of the research.

After the abstract comes an “introduction” of a page or two that details the research question, why it matters, and what approach the paper will take. This is followed by a literature review of about a quarter to a third the length of the entire paper. The literature review is often divided, with headings, into topical subsections, and is designed to provide a clear, thorough overview of the prior research literature on which a paper has built—including prior literature the new paper contradicts. At the end of the literature review it should be made clear what researchers know about the research topic and question, what they do not know, and what this new paper aims to do to address what is not known.

The next major section of the paper is the section that describes research design, data collection, and data analysis, often referred to as “research methods” or “methodology.” This section is an essential part of any written or oral presentation of your research. Here, you tell your readers or listeners “how you collected and interpreted your data” (Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault 2016:215). Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault suggest that the discussion of your research methods include the following:

- The particular approach to data collection used in the study;

- Any theoretical perspective(s) that shaped your data collection and analytical approach;

- When the study occurred, over how long, and where (concealing identifiable details as needed);

- A description of the setting and participants, including sampling and selection criteria (if an interview-based study, the number of participants should be clearly stated);

- The researcher’s perspective in carrying out the study, including relevant elements of their identity and standpoint, as well as their role (if any) in research settings; and

- The approach to analyzing the data.

After the methods section comes a section, variously titled but often called “data,” that takes readers through the analysis. This section is where the thick description narrative; the quotes, broken up by theme or topic, with their interpretation; the discussions of case studies; most data displays (other than perhaps those outlining a theoretical model or summarizing descriptive data about cases); and other similar material appears. The idea of the data section is to give readers the ability to see the data for themselves and to understand how this data supports the ultimate conclusions. Note that all tables and figures included in formal publications should be titled and numbered.

At the end of the paper come one or two summary sections, often called “discussion” and/or “conclusion.” If there is a separate discussion section, it will focus on exploring the overall themes and findings of the paper. The conclusion clearly and succinctly summarizes the findings and conclusions of the paper, the limitations of the research and analysis, any suggestions for future research building on the paper or addressing these limitations, and implications, be they for scholarship and theory or policy and practice.

After the end of the textual material in the paper comes the bibliography, typically called “works cited” or “references.” The references should appear in a consistent citation style—in sociology, we often use the American Sociological Association format (American Sociological Association 2019), but other formats may be used depending on where the piece will eventually be published. Care should be taken to ensure that in-text citations also reflect the chosen citation style. In some papers, there may be an appendix containing supplemental information such as a list of interview questions or an additional data visualization.

Note that when researchers give presentations to scholarly audiences, the presentations typically follow a format similar to that of scholarly papers, though given time limitations they are compressed. Abstracts and works cited are often not part of the presentation, though in-text citations are still used. The literature review presented will be shortened to only focus on the most important aspects of the prior literature, and only key examples from the discussion of data will be included. For long or complex papers, sometimes only one of several findings is the focus of the presentation. Of course, presentations for other audiences may be constructed differently, with greater attention to interesting elements of the data and findings as well as implications and less to the literature review and methods.

Concluding Your Work

After you have written a complete draft of the paper, be sure you take the time to revise and edit your work. There are several important strategies for revision. First, put your work away for a little while. Even waiting a day to revise is better than nothing, but it is best, if possible, to take much more time away from the text. This helps you forget what your writing looks like and makes it easier to find errors, mistakes, and omissions. Second, show your work to others. Ask them to read your work and critique it, pointing out places where the argument is weak, where you may have overlooked alternative explanations, where the writing could be improved, and what else you need to work on. Finally, read your work out loud to yourself (or, if you really need an audience, try reading to some stuffed animals). Reading out loud helps you catch wrong words, tricky sentences, and many other issues. But as important as revision is, try to avoid perfectionism in writing (Warren and Karner 2015). Writing can always be improved, no matter how much time you spend on it. Those improvements, however, have diminishing returns, and at some point the writing process needs to conclude so the writing can be shared with the world.

Of course, the main goal of writing up the results of a research project is to share with others. Thus, researchers should be considering how they intend to disseminate their results. What conferences might be appropriate? Where can the paper be submitted? Note that if you are an undergraduate student, there are a wide variety of journals that accept and publish research conducted by undergraduates. Some publish across disciplines, while others are specific to disciplines. Other work, such as reports, may be best disseminated by publication online on relevant organizational websites.

After a project is completed, be sure to take some time to organize your research materials and archive them for longer-term storage. Some Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols require that original data, such as interview recordings, transcripts, and field notes, be preserved for a specific number of years in a protected (locked for paper or password-protected for digital) form and then destroyed, so be sure that your plans adhere to the IRB requirements. Be sure you keep any materials that might be relevant for future related research or for answering questions people may ask later about your project.

And then what? Well, then it is time to move on to your next research project. Research is a long-term endeavor, not a one-time-only activity. We build our skills and our expertise as we continue to pursue research. So keep at it.

- Find a short article that uses qualitative methods. The sociological magazine Contexts is a good place to find such pieces. Write an abstract of the article.

- Choose a sociological journal article on a topic you are interested in that uses some form of qualitative methods and is at least 20 pages long. Rewrite the article as a five-page research summary accessible to non-scholarly audiences.

- Choose a concept or idea you have learned in this course and write an explanation of it using the Up-Goer Five Text Editor ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ), a website that restricts your writing to the 1,000 most common English words. What was this experience like? What did it teach you about communicating with people who have a more limited English-language vocabulary—and what did it teach you about the utility of having access to complex academic language?

- Select five or more sociological journal articles that all use the same basic type of qualitative methods (interviewing, ethnography, documents, or visual sociology). Using what you have learned about coding, code the methods sections of each article, and use your coding to figure out what is common in how such articles discuss their research design, data collection, and analysis methods.

- Return to an exercise you completed earlier in this course and revise your work. What did you change? How did revising impact the final product?

- Find a quote from the transcript of an interview, a social media post, or elsewhere that has not yet been interpreted or explained. Write a paragraph that includes the quote along with an explanation of its sociological meaning or significance.

The style or personality of a piece of writing, including such elements as tone, word choice, syntax, and rhythm.

A quotation, usually one of some length, which is set off from the main text by being indented on both sides rather than being placed in quotation marks.

A classification of written or artistic work based on form, content, and style.

A short summary of a text written from the perspective of a reader rather than from the perspective of an author.

Social Data Analysis Copyright © 2021 by Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter. But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free results chapter template

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods ). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and discuss its meaning), depending on your university’s preference. We’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as that’s the most common approach.

In contrast to a quantitative results chapter that presents numbers and statistics, a qualitative results chapter presents data primarily in the form of words . But this doesn’t mean that a qualitative study can’t have quantitative elements – you could, for example, present the number of times a theme or topic pops up in your data, depending on the analysis method(s) you adopt.

Adding a quantitative element to your study can add some rigour, which strengthens your results by providing more evidence for your claims. This is particularly common when using qualitative content analysis. Keep in mind though that qualitative research aims to achieve depth, richness and identify nuances , so don’t get tunnel vision by focusing on the numbers. They’re just cream on top in a qualitative analysis.

So, to recap, the results chapter is where you objectively present the findings of your analysis, without interpreting them (you’ll save that for the discussion chapter). With that out the way, let’s take a look at what you should include in your results chapter.

What should you include in the results chapter?

As we’ve mentioned, your qualitative results chapter should purely present and describe your results , not interpret them in relation to the existing literature or your research questions . Any speculations or discussion about the implications of your findings should be reserved for your discussion chapter.

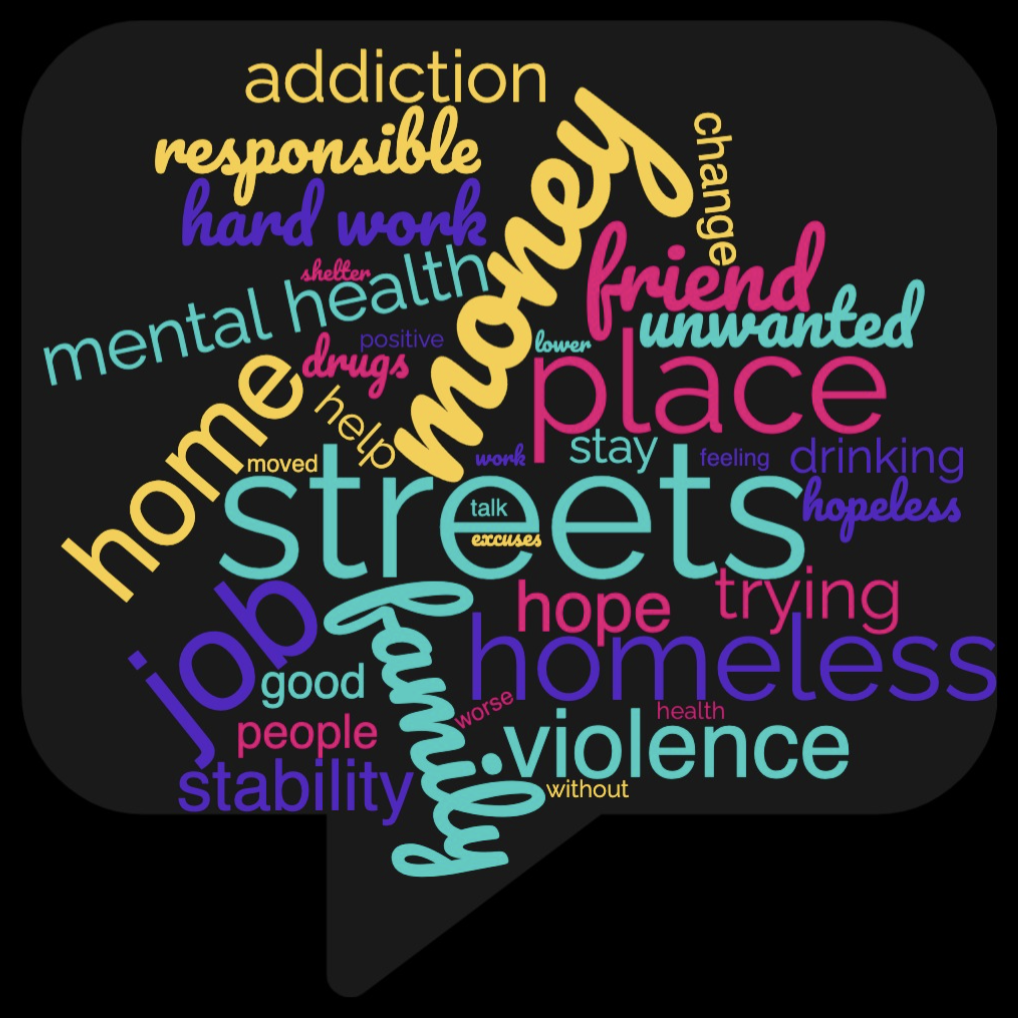

In your results chapter, you’ll want to talk about your analysis findings and whether or not they support your hypotheses (if you have any). Naturally, the exact contents of your results chapter will depend on which qualitative analysis method (or methods) you use. For example, if you were to use thematic analysis, you’d detail the themes identified in your analysis, using extracts from the transcripts or text to support your claims.

While you do need to present your analysis findings in some detail, you should avoid dumping large amounts of raw data in this chapter. Instead, focus on presenting the key findings and using a handful of select quotes or text extracts to support each finding . The reams of data and analysis can be relegated to your appendices.

While it’s tempting to include every last detail you found in your qualitative analysis, it is important to make sure that you report only that which is relevant to your research aims, objectives and research questions . Always keep these three components, as well as your hypotheses (if you have any) front of mind when writing the chapter and use them as a filter to decide what’s relevant and what’s not.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to look at how to structure your chapter. Broadly speaking, the results chapter needs to contain three core components – the introduction, the body and the concluding summary. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Section 1: Introduction

The first step is to craft a brief introduction to the chapter. This intro is vital as it provides some context for your findings. In your introduction, you should begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions and highlight the purpose of your research . Make sure that you spell this out for the reader so that the rest of your chapter is well contextualised.

The next step is to briefly outline the structure of your results chapter. In other words, explain what’s included in the chapter and what the reader can expect. In the results chapter, you want to tell a story that is coherent, flows logically, and is easy to follow , so make sure that you plan your structure out well and convey that structure (at a high level), so that your reader is well oriented.

The introduction section shouldn’t be lengthy. Two or three short paragraphs should be more than adequate. It is merely an introduction and overview, not a summary of the chapter.

Pro Tip – To help you structure your chapter, it can be useful to set up an initial draft with (sub)section headings so that you’re able to easily (re)arrange parts of your chapter. This will also help your reader to follow your results and give your chapter some coherence. Be sure to use level-based heading styles (e.g. Heading 1, 2, 3 styles) to help the reader differentiate between levels visually. You can find these options in Word (example below).

Section 2: Body

Before we get started on what to include in the body of your chapter, it’s vital to remember that a results section should be completely objective and descriptive, not interpretive . So, be careful not to use words such as, “suggests” or “implies”, as these usually accompany some form of interpretation – that’s reserved for your discussion chapter.

The structure of your body section is very important , so make sure that you plan it out well. When planning out your qualitative results chapter, create sections and subsections so that you can maintain the flow of the story you’re trying to tell. Be sure to systematically and consistently describe each portion of results. Try to adopt a standardised structure for each portion so that you achieve a high level of consistency throughout the chapter.

For qualitative studies, results chapters tend to be structured according to themes , which makes it easier for readers to follow. However, keep in mind that not all results chapters have to be structured in this manner. For example, if you’re conducting a longitudinal study, you may want to structure your chapter chronologically. Similarly, you might structure this chapter based on your theoretical framework . The exact structure of your chapter will depend on the nature of your study , especially your research questions.

As you work through the body of your chapter, make sure that you use quotes to substantiate every one of your claims . You can present these quotes in italics to differentiate them from your own words. A general rule of thumb is to use at least two pieces of evidence per claim, and these should be linked directly to your data. Also, remember that you need to include all relevant results , not just the ones that support your assumptions or initial leanings.

In addition to including quotes, you can also link your claims to the data by using appendices , which you should reference throughout your text. When you reference, make sure that you include both the name/number of the appendix , as well as the line(s) from which you drew your data.

As referencing styles can vary greatly, be sure to look up the appendix referencing conventions of your university’s prescribed style (e.g. APA , Harvard, etc) and keep this consistent throughout your chapter.

Section 3: Concluding summary

The concluding summary is very important because it summarises your key findings and lays the foundation for the discussion chapter . Keep in mind that some readers may skip directly to this section (from the introduction section), so make sure that it can be read and understood well in isolation.

In this section, you need to remind the reader of the key findings. That is, the results that directly relate to your research questions and that you will build upon in your discussion chapter. Remember, your reader has digested a lot of information in this chapter, so you need to use this section to remind them of the most important takeaways.

Importantly, the concluding summary should not present any new information and should only describe what you’ve already presented in your chapter. Keep it concise – you’re not summarising the whole chapter, just the essentials.

Tips for writing an A-grade results chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear picture of what the qualitative results chapter is all about, here are some quick tips and reminders to help you craft a high-quality chapter:

- Your results chapter should be written in the past tense . You’ve done the work already, so you want to tell the reader what you found , not what you are currently finding .

- Make sure that you review your work multiple times and check that every claim is adequately backed up by evidence . Aim for at least two examples per claim, and make use of an appendix to reference these.

- When writing up your results, make sure that you stick to only what is relevant . Don’t waste time on data that are not relevant to your research objectives and research questions.

- Use headings and subheadings to create an intuitive, easy to follow piece of writing. Make use of Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” and be sure to use them consistently.

- When referring to numerical data, tables and figures can provide a useful visual aid. When using these, make sure that they can be read and understood independent of your body text (i.e. that they can stand-alone). To this end, use clear, concise labels for each of your tables or figures and make use of colours to code indicate differences or hierarchy.

- Similarly, when you’re writing up your chapter, it can be useful to highlight topics and themes in different colours . This can help you to differentiate between your data if you get a bit overwhelmed and will also help you to ensure that your results flow logically and coherently.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your results chapter (or any chapter of your dissertation or thesis), check out our private dissertation coaching service here or book a free initial consultation to discuss how we can help you.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

This was extremely helpful. Thanks a lot guys

Hi, thanks for the great research support platform created by the gradcoach team!

I wanted to ask- While “suggests” or “implies” are interpretive terms, what terms could we use for the results chapter? Could you share some examples of descriptive terms?

I think that instead of saying, ‘The data suggested, or The data implied,’ you can say, ‘The Data showed or revealed, or illustrated or outlined’…If interview data, you may say Jane Doe illuminated or elaborated, or Jane Doe described… or Jane Doe expressed or stated.

I found this article very useful. Thank you very much for the outstanding work you are doing.

What if i have 3 different interviewees answering the same interview questions? Should i then present the results in form of the table with the division on the 3 perspectives or rather give a results in form of the text and highlight who said what?

I think this tabular representation of results is a great idea. I am doing it too along with the text. Thanks

That was helpful was struggling to separate the discussion from the findings

this was very useful, Thank you.

Very helpful, I am confident to write my results chapter now.

It is so helpful! It is a good job. Thank you very much!

Very useful, well explained. Many thanks.

Hello, I appreciate the way you provided a supportive comments about qualitative results presenting tips

I loved this! It explains everything needed, and it has helped me better organize my thoughts. What words should I not use while writing my results section, other than subjective ones.

Thanks a lot, it is really helpful

Thank you so much dear, i really appropriate your nice explanations about this.

Thank you so much for this! I was wondering if anyone could help with how to prproperly integrate quotations (Excerpts) from interviews in the finding chapter in a qualitative research. Please GradCoach, address this issue and provide examples.

what if I’m not doing any interviews myself and all the information is coming from case studies that have already done the research.

Very helpful thank you.

This was very helpful as I was wondering how to structure this part of my dissertation, to include the quotes… Thanks for this explanation

This is very helpful, thanks! I am required to write up my results chapters with the discussion in each of them – any tips and tricks for this strategy?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to present the analysis of qualitative data within interdisciplinary studies for readers in the life and natural sciences

- Open access

- Published: 25 May 2021

- Volume 56 , pages 967–984, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gerda Casimir 1 ,

- Hilde Tobi 1 &

- Peter Andrew Tamás ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5409-1273 1

6020 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Research that addresses complex challenges often requires contributions from the social, life and natural sciences. The disciplines that contribute subject response data, and more specifically qualitative analyses of subject response data, to interdisciplinary studies are characterised by low consensus with respect to methods they use a diversity of terms to describe those methods and they often work from assumptions that are foreign to readers in the natural and life sciences. The first contribution this paper makes is to demonstrate that the forms of reporting that may be adequate for communicating quantitative analysis do not provide teams that include members from natural, life and social sciences with useful accounts of qualitative analysis. Our second contribution is to discuss and model how to report four methods appropriate for qualitative contributions to interdisciplinary projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

What Now and How? Publishing the Qualitative Journal Article

Beyond qualitative/quantitative structuralism: the positivist qualitative research and the paradigmatic disclaimer.

How Natural Is “Natural” in Field Research?

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There are strong arguments to combine quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis within the social sciences (Babbie 1989 ; Creswell and Clark 2000 ; Johnson Onwuegbuzie and Turner 2007 ). Research that addresses complex challenges, such as adaptation to the effects of climate change, often involves teams from the social, life and natural sciences. These interdisciplinary studies frequently demand teams to integrate qualitative analysis of subject response data with quantitative analysis of direct measures of natural phenomena. Further, reports of these studies are often presented in journals whose reporting formats anticipate quantitative analysis of direct measurements for natural and life science readers. We have found specific guidance on the design of interdisciplinary research (e.g. Tobi & Kampen 2018 ), on how to make it meaningful for policy (e.g. Kampen and Tamás 2014 ) and we have found a large number of guidelines for the reporting of both quantitative and qualitative analysis for both disciplinary researchers and for those times when interdisciplinarity is limited to the social sciences. Despite our own and our peers’ efforts, we have not found guidelines for the presentation of the qualitative analysis of subject response data that well serve integration into the reports of interdisciplinary studies published in journals that are read outside of the social sciences.

Our purpose with this paper is to strengthen inter-disciplinary science by improving the adequacy of the reports of analysis of qualitative subject response data within reports of interdisciplinary studies. In the next section we demonstrate the need for these guidelines by describing and faulting existing reporting practices. The guidance we then offer is presented through the use of a model case. The analysis methods we present in this model case were selected for their relevance to interdisciplinary research addressing environmental challenges.

2 The transparency of reporting in interdisciplinary research

In preparation for this manuscript we downloaded four years of papers that contained both ‘interdisciplinary’ and ‘interview’ in their titles, keywords and abstracts (N = 1160 papers). Footnote 1 The term ‘interdisciplinary’ was selected as we were certain that authors’ self-identification would be a strong indicator of interdisciplinarity and the term ‘interview’ was selected as the alternatives we considered, such as ‘qualitative’ produced high false-positive rates. We recognize that this search strategy likely excluded many studies which compromises the generalisability of our findings. We then used automatic coding in Atlas.ti to identify all paragraphs that contained both words ‘analysis’ and ‘interview’ (n = 1033 paragraphs) to quickly identify those papers that contained a substantial discussion of the methods used to analyse interview data and a location within papers where that discussion is certain to be found. We then used random selection from these paragraphs to identify papers for examination. We continued to randomly select papers for examination until five in a row produced no novel observations (n = 79 papers).

In all of the papers examined, researchers reported that they identified and aggregated themes in order to present patterns. The description given these efforts generally mirrored the account given of their analysis of quantitative data. For example, many reported ‘thematic content analysis’ which appears to be as informative as ‘multiple logistic regression.’ These two are neither equivalent nor are they similarly informative. The term ‘multiple logistic regression’ references a specific set of analysis procedures and assumptions about which there is well-known consensus. Thematic content analysis, however, involves two distinct steps neither of which benefits from the consensus supporting interpretation of the term ‘multiple logistic regression’. The first step in thematic content analysis is the attachment of codes to text that capture meaning. This step, coding, is akin to measurement or data processing in the natural and life sciences. The codes applied are the equivalent to the pH value recorded by a researcher when using litmus strips to measure acidity in surface water or the calculation of BMI based on data provided on weight and height.

Staying with the step of coding, which tended to be far better discussed than synthesis, in the articles we reviewed it was consistently clear that researchers identified themes, but it was not clear where those themes came from. Unlike chemistry, where budding scientists are taught consistently how to read litmus strips so the reader knows what procedures lie behind a stated pH value, there is no consensus in the social sciences that we know of that allows a reader to infer from ‘thematic content analysis’ an unequivocal understanding of how researchers identified units of text as meaningful and then determined what speakers meant by what they said. Certainly, many of the articles we reviewed used multiple raters and negotiation to improve reliability, but inter-rater agreement does not improve transparency in the manner required to shed light on validity.

Turning now to synthesis, we did not often find interpretable discussion of mechanisms by which the text strings coded by researchers were combined so as to produce the patterns that were reported. In the quantitative world, this would be the same as presenting the manipulation of data as a ‘cluster analysis’ without any further specification of the math and the criterion used to support identification of the patterns reported. Those cases that provided an interpretable account tended to be informed by well referenced use of grounded theory in which the processes and logic behind a line of argument and refutational synthesis are clearly stated.

In summary, analysis of qualitative subject response data and quantitative direct measures data arise from disciplines that vary dramatically in their level of consensus. Therefore, qualitative analysis requires far more detailed reporting than is normally found in the accounts given of quantitative analysis. In the following section we introduce and then provide and discuss model reports for the analysis of narrative subject-response data in research that is both mixed-methods and interdisciplinary.

3 Model case

3.1 material and methods, 3.1.1 material.

To demonstrate appropriate presentation of the qualitative analysis of subject response data within reports of interdisciplinary studies we used transcripts of eleven semi-structured interviews that were part of an interdisciplinary study in the domain of socio-technical studies. The questions that we use to provide model presentations here are (a) how do international graduate students use ICT technology to maintain ties with their household members and (b) what is the meaning of ‘household’ as experienced by those students. This material, relatively unstructured interview data, is typical of that subjected to qualitative analysis in interdisciplinary research.

Both the interviews and the transcripts were done in Spring 2012 by Jarkyn Shadymanova, at the time research fellow at the Sociology of Consumption and Households Group, Wageningen University, the Netherlands. Interviewees were African graduate students of Wageningen University who were interviewed in English. In the remainder of this paper the numbers P1 to P11 are used to refer to these interviewees. As should be found in such reports, a demographic description of the interviewees is presented in Annex one.

3.1.2 Methods

For this paper we exercised simple forms of four methods of analysis, aspects of which we have often found to be silently combined by researchers who are contributing to interdisciplinary studies: content analysis, metaphor analysis, domain analysis and membership categorization analysis. For each method we provide exemplar texts for a ‘materials and methods’ and for a ‘results’ section that are preceded by an introduction to the method and followed by a discussion of the method and its reporting.

Each of the methods we have chosen to model and discuss is understood and used in diverse ways. Silverman ( 2015 ), for instance, mentions content analysis, membership categorization analysis, conversation analysis, discourse analysis, semiotics and workplace studies. Flick ( 2014 ) speaks of grounded theory coding, thematic coding and content analysis, conversation, discourse and hermeneutic analysis. Coffey and Atkinson ( 1996 ) distinguish narrative analysis, metaphor analysis, and domain analysis. Bernard ( 1988 ) addresses narrative, discourse and content analysis. In addition, often ethnography or feminist research is mentioned (Bernard 1988 ; Grbich 2012 ; Silverman 2015 ).

There are also inconsistencies in discussion of coding. Most authors see coding as essential for qualitative analysis. However, they differ in the way they see coding in relation to analysis. Miles and Huberman explicitly state: “Coding is analysis” (Miles and Huberman 1994 p. 56). Others see coding and analysis as two distinct phases, where the latter is of a higher level of abstraction. Flick, citing Strauss and Corbin, 1990, distinguishes coding and ‘axial coding’, where the “Axial coding is the process of relating subcategories to a category” (Flick 2014 p. 311).

In our many years of instruction at the graduate level, our students have consistently recognized on their own that these taxonomies overlap, that the terms included in each are not mutually exclusive and that each taxonomy partitions practice in slightly different ways. In addition to making it impossible to infer from a label such as ‘thematic content analysis’ what was actually done, this lack of consensus also makes it impossible for an author who has transparently reported their analysis to defend against a detractor who argues, from a different definition of the method named, that their analysis is lacking some crucial dimension. The lack of consensus that characterizes methodological texts on qualitative data analysis brings us to our most basic recommendation: transparent report of qualitative analysis requires justification and detailed description of each of the analytic steps followed and the assessment of the appropriateness of such analysis must turn on examination of analytic steps in context and not the label assumed.

3.2 Content Analysis

3.2.1 introduction.

Content analysis is a ‘technique for making inferences by systematically and objectively identifying special characteristics of messages’ (Holsti 1969 , p. 608). As used in this study, content analysis aimed to examine textual data through the systematic application of pre-determined categorization codes and then determining frequencies of text fragments in each category (Silverman 2015 ).

Content analysis is typically used to answer questions of the form ‘who, what, when, where, how and how often’. All kinds of qualitative data can be subjected to content analysis: newspaper clippings, literary works, e-mails, pictures, audio clips, blogs, movies, scientific articles, answers to open questions in a survey, and, of course, also interview or focus groups discussion transcripts.

Coding within content analysis is done top-down, on the basis of a predefined protocol with a coding scheme, derived from the theoretical framework of the researcher as informed by a review of relevant literature. Initial coding schemes are often tested and amended based on their performance in a sample of the data.

Coding consistently imposes an operationalization of the conceptual framework of the researcher on the data in a manner that may be inconsistent with the framing used by research subjects. If repondents consistently use the same terms to describe analytically relevant concepts, automatic coding may be used. Compared to manual coding, automatic coding has three advantages. It allows for the coding of larger data sets, it increases completeness and it eliminates human error. Nonetheless, automatic coding requires careful consideration. For instance, the term ‘internet’ can appear in semantic units indicating a problem (lack of access) as well as a mode of–successful–communication.

In our example the research question for content analysis was: What are the characteristics of each respondent’s household and how do they communicate–with what tools, how often and how long–with their relatives back home?

3.2.2 Report of method

In order to determine household characteristics we used top-down content analysis. The coding frame used was based on an earlier scheme (Casimir and Tobi 2011 ) and extended with a list of ICT (Information Communication Technology) devices derived from Shadymanova’s interview guide. The coding scheme was segmented following the research questions: which people are part of the household, what is shared (resources, activities, expenditures), which ICT tools are used to communicate with the household, and how often are they used. The coding protocol was tested on two randomly chosen interviews, found inadequate and modified such that it adequately anticipated the full diversity of ICT tools used and household compositions. Manual coding was used rather than automatic as tests of automatic coding did not identify all relevant text strings and did not consistently associate appropriate codes with found text strings. For instance, the search string ‘internet access’ could indicate both the possibility of internet access and the absence of it.

3.2.3 Report of results

3.2.3.1 coding.

The coding phase resulted in Table 1 , where the first two columns contain the coding scheme. The third column gives a summary of results.

3.2.3.2 Analysis

Analysis consisted of an overview of frequencies of the codes applied (column 3 of Table 1 ). Six of the interviewees had one or more children, five of the interviewees were single. Most frequently mentioned as shared within the household were: sharing a roof, sharing consumption (food), sharing income and expenditures.

To communicate with their household back home, all interviewees used a mobile phone, e-mail and instant messaging (Skype). Six of the eleven interviewees had contact with their household back home every day, two interviewees twice or three times per week, and three interviewees once a week. The remaining interviewee–who was single without children–had contact with her relatives once per month. Duration of communications varied from a few minutes to three hours or more. The latter only when Skype was available.

3.2.4 Discussion of content analysis and its reporting

Top-down content analysis provided a description of manifest features within the data identified by the researchers at the outset as relevant to their study. The method allowed the researchers to extend the initial coding scheme that appeared adequate with respect to the research question, such that it became adequate with respect to the data. Results however are limited to the deductively imposed framework used and will not report findings that call into question the appropriateness of that framework.

3.3 Metaphor analysis

3.3.1 introduction.

Metaphor analysis uses systematic examination of elicited or spontaneous metaphors to identify latent conceptualizations (Schmitt 2005 ). According to Coffey and Atkinson ( 1996 ) metaphors are grounded in socially shared knowledge: “Particular metaphors may help to identify cultural domains that are familiar to the members of a given culture or subculture; they express specific values, collective identities, shared knowledge, and common vocabularies” (Coffey and Atkinson 1996 , p. 86). Metaphors require and reflect shared meanings. “In terms of data analysis (…) we can explore the intent (or function) of the metaphor, the cultural context of the metaphor, and the semantic mode of the metaphor” (Coffey and Atkinson 1996 , p. 85). Metaphor analysis is well suited for questions such as: ‘how do people depict a situation?’, or: ‘how do they describe a process?’ Data could be any kind of text, talk or visual. Metaphor analysis is particularly relevant when research questions require researchers to identify and make explicit implicit aspects of data, for example, when communication is highly coded as is often found in exploration of sensitive topics.

A metaphor analysis involves identification, classification and inductive examination of metaphors to draw inferences regarding the structure and significance of the conceptual metaphors of which they are an instance (Low and Cameron 1999 ). As metaphors are manifested in ways that are context-dependent, their analysis often starts with bottom-up coding. Top-down coding for metaphors is only indicated when researchers have a specific interest in pre-determined forms of metaphors (e.g. path metaphors, battle metaphors, animal metaphors).

The research question for our example is: what implicit perceptions and/or feelings do respondents have with respect to their households and their travel from that household, expressed through flowery language.

3.3.2 Report of method

Following Coffey and Atkinson ( 1996 ), we started metaphor analysis with building a protocol that would allow multiple researchers reliably to identify instances of flowery language. We tested this protocol and then coded the text for instances of flowery language. Once so identified, we then examined text coded as flowery in detail for instances of metaphors. For this coding we operationalized ‘metaphor’ as any instance where a term used can also be used in a different context and where hearers’ knowledge of that use in that different context alters their interpretation. Once all instances of flowery language were scrutinized for metaphors, we identified the source context for metaphorical terms, detailed the additional meanings that may be implied through use of that term, and then selected from those possibilities the one that was most probable.

3.3.3 Report of results

3.3.3.1 coding.

Coding identified metaphors in more than half of the transcripts. Respondents used non-literal descriptions when discussing topics that may involve emotion, such as distance (e.g. ‘another planet’), connection (e.g. ‘blood ties’) and surprise or impact (e.g. ‘shock’). The complete list of metaphors found is presented in Table 2 .

3.3.3.2 Analysis

On review, we decided that it was inappropriate to undertake analysis beyond the identification of potential metaphors. Each of our respondents came from a distinct cultural context so each could be expected to have their own distinct repertoire of metaphors. The narratives examined did not arise in natural conversation within their context but in interaction with an interviewer who comes from a different context, so it is not clear that respondents would have drawn on the repertoire found in their home context. As metaphor use is tied to both language and context, and interviews were held in a foreign country in both respondents’ and interviewer’s second language, we could not identify possible, let alone the most probable, meaning.

3.3.4 Discussion of metaphor analysis and its reporting

Metaphor analysis is useful when research questions require interpretation of a narrative that goes beyond the strictly literal meaning of terms. Since we did not have enough information at our disposal–as explained in Sect. 4.1 ., we cannot discuss results or come to conclusions.

3.4 Domain analysis

3.4.1 introduction.

Domain analysis was created by ethnographers to help them understand how the communities they were studying structured their world. “Domain analysis involves a search for the larger units of cultural knowledge called domains (…). In doing this kind of analysis we will search for cultural symbols which are included in larger categories (domains) by virtue of some similarity.” (Spradley 1979 , p. 94). Spradley distinguished four elements in the domain structure. The first is the so-called folk terms that informants use. These terms have semantic relationships–the second element–with ‘cover terms’, a name for a category of cultural knowledge, which are the third feature of domains. Finally, every domain has a boundary: informants know what is part of the domain and what is not (Carballo-Cárdenas Mol and Tobi 2013 ).

Codes are derived from the ‘folk’ terms used by the respondents in interviews (Borgatti and Halgin 1999 ) using in-vivo coding. “The systematic use of in-vivo codes can be used to develop a ‘bottom-up’ approach to the derivation of categories from the content of the data” (Coffey and Atkinson 1996 , p. 32). Data can be any kind of text or script, both naturally occurring and elicited text, talk and visuals.

The research question in our example was: How do respondents talk about their ‘household’ and their communication with home?

3.4.2 Report of method

Domain analysis was created in order to allow researchers to describe how respondents structure their worlds on their terms. Following Coffey and Atkinson ( 1996 ) our first step was to code the ‘folk terms’ with which the interviewees expressed their ideas about their household and the communication with that household. The second step was to identify those words or expressions that clearly indicated distinct domains (cover terms). Cover terms were inductively identified through clustering of folk terms. Clustering was indicated, in the first instance, by proximity between terms. For example, ‘sharing’ is subdivided into sharing a roof, sharing expenditures, etc. Once proximity associations were exhausted, terms were then clustered using refutational and then confirmatory arguments. For example, the term ‘meaning of life’ was tested against ‘sharing’ and ‘significance of household’ and found to fit least poorly and acceptably with ‘significance of household.’ Our last step was then to identify how other descriptive terms related to the cover terms just identified. Examples of such semantic relations are membership, causation or sequence.

3.4.3 Report of results

3.4.3.1 coding.

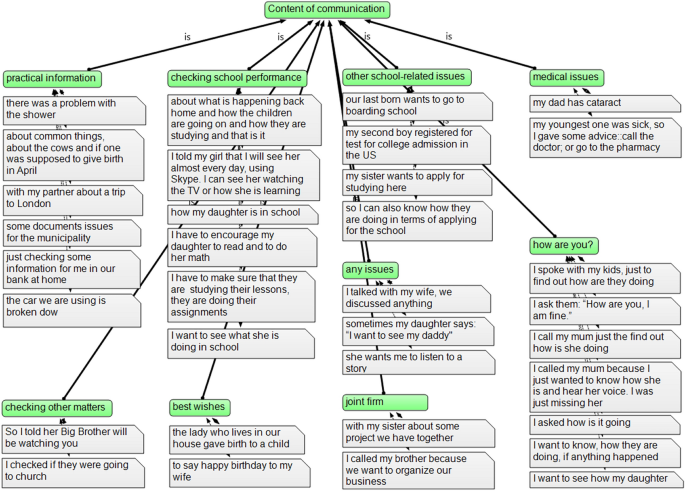

When talking about their household, interviewees referred to the sharing of several aspects–sharing a roof, food, income, expenditures, time, household organization–and to the significance of households, including feelings of connectedness and emotional aspects. Terms used were, for instance, “the people who live together”, “who share food”, “who live under the same roof”; and: “it is an emotion”, “it is protecting”, “it is important”, “it is the ‘holy thing’”. Or: “the meaning of life”. Also mentioned: “It is the place where I feel important and valuable”.

When talking about communication, the interviewees referred to the content of communications. The content of communication ranged from sharing practical information–some repair that has to be done, financial issues–to conversations about how their beloved ones are doing, in particular: how children are doing in school. Also, medical problems with children or parents were discussed, or business shared with relatives. Sometimes no specific topic was mentioned, but the interviewees indicated that they wanted to communicate with home because they felt lonely, or because they wanted to hear their mother’s voice, since he or she missed her.

Interviewees did also talk about their communication style. One of the interviewees indicated that ICT creates circumstances for communication which may ask for a different style: “You have to be more kind, support them. When I am there, I tend to be more rigorous” (P4).

3.4.3.2 Analysis

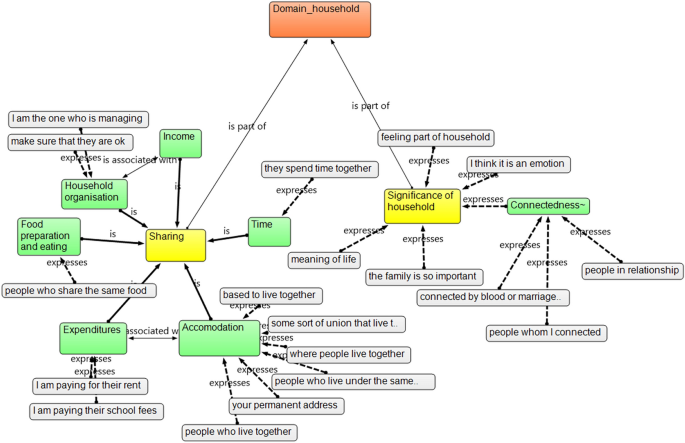

In the analysis phase, cover terms were defined and the folk terms were related with semantic relationships to these cover terms. In some cases, the cover terms were divided into sub-terms, for instance ‘sharing’ is subdivided into sharing a roof, sharing expenditures, etc. Figure 1 presents the result of both the coding phase and the analysis phase for the domain ‘Household’. In Fig. 2 , the content types (cover terms) and expressions (folk terms) of the domain ‘Communication’ are shown.

Domain household with folk terms (uncolored boxes), semantic relationships (labels on the arrows) and cover terms (filled boxes, with initial capitals)

Domain communication, in particular content of communication

3.4.4 Discussion of domain analysis and its reporting

Domain analysis allowed us to answer questions about how respondents structured their world. It was possible efficiently and reliably to identify folk terms through in-vivo coding. Decisions on categorization of folk terms and semantic relationships between folk terms and cover terms required subjective judgement that would be difficult to reproduce, but was quite easy to transparently document. For example, rather than proceed with the classification structure just presented, we could have opted for subcategories such as practical reasons (sharing information, asking where people are), communication for its own sake (when feeling lonely, for instance) and other reasons for communication. Transparent presentation of these subjective judgements should be reported as an annex within or as supplemental material accompanying a standard-length journal article.

3.5 Membership Categorization Analysis

3.5.1 introduction.

Membership categorization analysis (MCA), introduced by Sacks in 1972, identifies the categories interviewees use to classify people and how these categories are routinely attached to particular kinds of attributes and activities (Silverman 2015 ). The rules applied to attribute individuals to categories are called Membership Categorization Devices, MCDs (Schegloff 2007 ). MCA does not ask people how they categorize, but investigates how people “use social categories to account for, explain, justify and make sense of people’s actions” (Fitzgerald and Housley 2015 , p. 6). Each set of categories is a collection and categories may belong to more than one collection: professor is part of the collection students/administrators/staff, i.e. university community, but also part of the occupational collection plumber/doctor/secretary/undertaker (Schegloff 2007 ).

In the actual execution of MCA, the fundamental goal is to identify how respondents order categories and their attributes in their social world. Data analyzed through MCA may be any kind of text, talk or visuals. We used Membership Categorization Analysis to identify how respondents determined if a given individual was a member of their household.

3.5.2 Report of method

Membership categorization analysis was developed to identify from natural speech how subjects classify others and what characteristics are associated with those classes (Silverman 2015 ). In our analysis we used MCA to identify the rules by which our subjects classified others as member of their household: membership classification devices. Shadymanova elicited data appropriate for this analysis by asking respondents the following questions: “Could you tell me about your household?” and “What is a household for you?”. We identified each instance where an individual was classified as either a member or not a member of the household and then coded explanatory text. These fragments of explanatory text were then examined for justifications for the classification just given. Justifications were then clustered by similarity and each cluster of justification was then described as a membership classification device.

3.5.3 Report of results

3.5.3.1 coding.

Respondents appeared to use several terms when indicating whether individuals were members of their household or not. Interviewees used terms as ‘being family’, ‘having blood ties’. Several found sharing a roof, sharing income, or expenditures, sharing food or household chores justification to include people in the category ‘household’. In several cases, household membership was related to feeling responsible (“I am paying their school fees / their rent, because I am feeling responsible for them”). Also, emotional terms were used (“She feels like family”). Some of the interviewees realized that their cultural background influences their rules of inclusion:

If I consider household as composed of those who are close to me somehow, I will say that I have one wife; I have three kids; and I have a lady who helps us at home, who helps my wife. So that is my household, my small household. But in Africa, let’s say in my country, (…) [the] household is part of a larger household: (…) aunts, (…) one brother and some sisters. (P1)

One interviewee said: “ household is the space you are sharing and supplying for daily needs ” (P4). Since he was the one who paid for food and rent, he was part of that household, also when he was abroad at the moment. Sharing a roof was also for P3 a reason to include people; however, being absent was no reason to exclude people as a member of the household.

Several interviewees expressed awareness of the existence of different definitions of households by saying: my wife and my children constitute my nuclear household, but in our culture–or Africa, or in my country–we include siblings, aunts, grandparents. Also, nephews or nieces for whom they took care by paying rent or school fees could be included or excluded from the household, depending on the definition used.

The second column of Table 3 contains the terms used by the interviewees.

3.5.3.2 Analysis

After the coding was done, the rules of inclusion and exclusion used by the interviewees were classified into categories of Membership Categorization Devices, given in the first column of Table 3 . The third column contains further remarks.

3.5.4 Discussion of MCA and its reporting

MCA produced a list of criteria (Membership Categorization Devices) that justify classification of individuals with respect to their membership in the category ‘household’. It gave the authors a new understanding of respondents’ public construction of their understanding of relationships. Significantly, interviewees’ notions of ‘household’ were mutually inconsistent and many interviewees used more than one device (e.g. blood and familiarity) when determining membership in their household.

4 Discussion

4.1 comparison of the four methods modelled.

In the previous section we modelled and discussed what is required to usefully report individual qualitative analysis methods within interdisciplinary studies. In this sub-section we step back and comparatively discuss the methods we modelled.