- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Feature stories /

Speaking out on the stigma of mental health

Persons with psychosocial disabilities frequently face stigma, discrimination and rights violations, including within and from the medical community, which reflects broader societal stigma. One doctor relates his personal experience here and how he uses it today to challenge stigma.

When Dr Ahmed Hankir first experienced extreme psychological distress as a medical student in the United Kingdom in 2006, he delayed seeking help due to the shame and stigma of having a mental health condition.

Exacerbating his distress was the added stigma of being a man of colour and a Muslim, which, with his mental health condition, made up what he calls a “triple whammy” of stigmas that he “internalized”. It led to him feeling “dehumanised”.

The stress and strains of working low-paid jobs to support himself as a student, and an outbreak of war in Lebanon, the country of his roots and where his parents were living, made matters worse. Meanwhile, he was living in a dilapidated house in one of the most dangerous areas of Manchester.

The intersectionality of these stressors – which added a “layer upon layer” – are often overlooked at the level of the individual, he said. Racism might be passed over. “It might be there is some gaslighting... so, you know, you are not a victim of racism.”

Hankir, who was born in Belfast when his parents fled the 1982 war in Lebanon, but later returned to Lebanon as a teenager, also said he had an identity crisis. “We want to be accepted, but I wasn't treated as British in the UK and I wasn't treated as Lebanese in Lebanon.”

Stigma “rampant” in the medical profession

Yet it was in his own profession that he felt the stigma of mental health most deeply, which led to the delay in seeking help. He was “ridiculed” by fellow medical students and ostracised by his closest companions. When he sought help from the person in charge of student support, a person who had the power to have him removed from his course, he was “psychologically tortured”. He was forced to temporarily interrupt his studies.

“Stigma is rampant in the medical profession. Unless we address it, it will continue to destroy and devastate the lives of many. We’re just scratching the surface now - I don’t know an expert in stigma. There is a lot of ignorance on how to deal with mental health,” he said.

Not only is there ignorance, but there is also arrogance from health providers, some of whom look down on people with mental health conditions and psychosocial disabilities, he said.

“It takes strength to accept that you might be a source of stigma. What we need is humility. But I’ve met inspirational, humble doctors who have contributed to my recovery and continue to contribute to my resilience.”

“My lived experience is my superpower”

Today, Hankir is a psychiatrist and he draws from his past: “My lived experience is my superpower. It’s a strength, not a weakness. It makes me more insightful, empathetic and driven.

“When I'm working in frontline psychiatry and I'm providing care for a person in a mental health crisis at 2am, I often draw on my personal expertise more than my professional expertise especially when attempting to develop a rapport and 'therapeutic alliance' with the person receiving care from me.”

He believes that many of his peers have also experienced psychological distress, but have chosen to remain silent about it. “I’m honest and open about my experience of living with a mental health condition. More people are talking about it. We normalize living with mental health conditions.”

Ahmed has won multiple awards for his “Wounded Healer” presentation, including from WHO in 2022. Photo credit: WHO/ Michelle Funk

Delivering the “Wounded Healer” presentation around the world

Hankir is now renowned for his “ Wounded Healer ” presentation, which aims to debunk myths and humanize people living with mental health conditions through blending performing arts and storytelling with psychiatry.

The Wounded Healer also traces Hankir’s recovery journey. “Speaking out on stigma helps to reduce it,” he explained. More than 100,000 people in 20 countries have heard him speak. In recognition of his work, Hankir received the 2022 World Health Organization Director-General Award for Global Health, among other awards.

He welcomes WHO’s Quality Rights Initiative, which takes an approach to mental health grounded on a human rights framework that empowers, dignifies and humanizes people with mental health conditions.

“Our human rights are being violated, regardless of time and place – high income country, low income country. Too many people feel like they have been brutalized,” he said. “When care is available, there are also concerns about the quality of care.”

He continues to face negativity from some psychiatrists, some of whom are “suspicious” of his success. “They accuse me of fabricating having a severe mental health condition. It is as if people living with severe mental health conditions can’t recover or excel, and can only ever think of survival. I was miserable for many years. But now I am not just surviving, I’m thriving,” he laughed.

A version of this story first appeared in the WHO Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities.

Understanding Mental Health Stigma: 17 Ways to Reduce It

If so, you know the discomfort, shame, and dehumanization that occurs.

Labeling others separates people based on actual or perceived differences. The stigma associated with being labeled aims at one’s identity and divides us and them .

The label linked to certain assumptions lingers, impacting impressions of the individual regardless of their behavior (Yanos, 2018).

The differentiation between us and them may seem minor. However, a closer look reveals the depth it reaches to the point of eroding social capital — the strength and benefits derived through societal cohesion.

This article discusses mental health stigma, its effects, and ways to reduce it.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients build healthy, life-enriching relationships.

This Article Contains

Understanding mental health stigma, 2 real-life examples and statistics, 22 effects of stigma according to research, how to reduce mental health stigma, 8 questionnaires, questions, and scales, 5 activities, worksheets, and ideas, best books to educate yourself and others, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message, frequently asked questions.

The definition for the word stigma includes a brand, a mark of disgrace or infamy, and a mark of censure (Dobson & Stuart, 2021).

According to Ritzer (2021, p. 162), “stigma is a person’s characteristic that others find, define, and often label as unusual, unpleasant, or deviant.”

Labels aim to show the individual as unpredictable, unreliable, and potentially dangerous (Dobson & Stuart, 2021). A label effectively applied creates fear and distance between society and the one who is labeled.

Brief history of mental health stigma

Mental illness goes back to the earliest human writings from ancient Israel, China, and Greece, explaining it as bad luck or being cursed.

More recently, Erving Goffman’s seminal work Asylums (1961) analyzed the treatment of patients in psychiatric facilities and showed the negative impact punitive treatment had on their mental health (Dobson & Stuart, 2021).

Goffman’s work revealed that labeling and stigmatization can have enduring, if not permanent, effects on patients (Dobson & Stuart, 2021).

Mental health stigma and discrimination

According to Philip Yanos (2018, p. 10), author of Written Off: Mental Health Stigma and the Loss of Human Potential , stigmatizing labels “diminish people’s participation in community life and inhibit them from achieving their full potential as people.”

Yanos views mental health stigma as a social injustice and suggests focusing on society’s adverse reactions instead of eradicating symptoms.

Stigmatization leads to discrimination.

Discrimination became lethal in 1939 when Hitler created the heinous T-4 program to euthanize residents of private hospitals, psychiatric institutions, nursing homes, and others with psychiatric or neurological disorders (Yanos, 2018).

Sadly, discrimination toward mental illness is still in news headlines, media representations, hiring practices, and structural norms.

Approximately 43.3% of US adults with mental illness will not receive help. They may avoid seeking treatment because they fear the label, stigma, and discrimination (Evans et al., 2023).

Simone Biles

As fervor for the 2021 Tokyo Olympics grew, finalists for the various teams were announced. Simone Biles was a top US gymnast with astounding strength and skills.

Soon after the Olympics began, it became clear that Biles was struggling. Citing a case of the twisties , she pulled out of the competition to tend to her mental health.

Biles returned to competition in 2023 after a two-year hiatus to win first place in the Core Hydration Classic (Holcombe, 2023).

Aaron Hernandez

The case of Aaron Hernandez is one of tragedy and missed opportunities. Hernandez found success playing football for the New England Patriots. Unfortunately, Aaron’s behavior spiraled out of control. He was ultimately found guilty of murder in 2015.

In 2017, Aaron committed suicide in jail. Autopsy results showed he suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a neurodegenerative disease often associated with symptoms similar to dementia, violence, and depression (Gregory, 2020).

4 Mental health myths and facts

A plethora of myths abound regarding mental illness. Let’s clarify a few that were obtained from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2023).

Myth – Mental health issues cannot affect me.

Fact – In the United States, 1 in 5 adults experience mental health issues in a given year.

Myth – Mental health conditions result from character flaws or personality weakness.

Fact – Various factors, including physical illness, injury, brain chemistry, trauma, abuse, and family history, contribute to mental illness.

Download 3 Free Positive Relationships Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients to build healthy, life-enriching relationships.

Download 3 Positive Relationships Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Yanos (2018) identifies three primary types of stigma.

Public stigma

Public stigma refers to creating intentional chasms between us and them through the labeling process.

- Patient label – Identifying the individual as a patient requiring treatment or hospitalization.

- Pejorative labels – Labels such as crazy or insane refer disparagingly to the individual.

Discriminatory public behaviors include:

- Social isolation

- Gossiping about the individual

- Being passed over for promotion

- Concerns about reliability

This YouTube video demonstrates the public’s perception of people who have mental illness.

Self-stigma

Self-stigma happens when the labeled individual will self-handicap , self-label, and use their label as an excuse for failure, limiting their development.

The effects of self-stigma can include:

- Feeling damaged

- Feeling weak

- Feeling vulnerable

- Dressing inconspicuously to be less visible in public

- Not speaking up for themself

- Holding back from seeking positions or promotions

- Feelings of embarrassment, diminishment, and self-hatred

Discriminatory behaviors include:

- Limiting self to avoid stigma

Structural stigma

Yanos (2018, p. 3) states, “Structural stigma is again a sociological concept that identifies the inherent and intentional effects that derive from social power dynamics and the policies and practices of institutions to restrict the autonomy of people with a mental illness.”

Scenarios where this may apply include:

- Involuntary hospitalization

- Denial of insurance payments in cases of suicide

- Restriction of individuals with a history of mental illness in specific career fields

- Enacting policies that prohibit insurance claims

- Mental health screenings for specific social roles

- Restricted health care for people with mental illness

When Simone Biles withdrew from the competition, she highlighted mental health (Holcombe, 2023).

Conversation about mental illness should be omnipresent. Often, we avoid it to spare discomfort. Meanwhile, the discomfort for those suffering hits a fever pitch.

How to reduce stigma in the workplace

Harvard Business Review discusses ways managers can help create an empathetic workplace culture (O’Brien & Fisher, 2019). These can also be generalized for other uses.

1. Focus on language

Terms used in gest or casual conversion can create or add to stigmatization. Using derogatory terms such as “Mr. OCD” or “schizo” can sound like an attack to those struggling.

2. Rethink sick days

Normalizing the idea of tending to mental health using sick days can contribute toward an environment of mental and physical health.

3. Open and honest conversation

Creating a space where people can talk openly about mental health issues without fear of rejection or judgment creates psychological safety .

4. Response training

Train employees in Mental Health First Aid , a national program that helps recognize those struggling and connects them to resources that will help.

Developing lesson plans for schools

Another way to promote positive mental health is through social emotional learning (SEL) curricula. Social emotional learning enhances strategic protective factors that buffer against the risks of mental health through responsive relationships, skill development, and emotionally safe environments (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, n.d.).

In addition to bolstering mental health and wellness, SEL exercises and activities help improve attitudes about self and others and decrease risky behaviors and emotional distress.

This short TED talk explains the benefits of SEL and how to change perspectives.

Yanos (2018, p. 41) describes microaggressions as “subtle communications of prejudice toward individuals based upon memberships in marginalized social groups.”

Microaggressions include comments that are rude and insensitive. The comments may exclude or nullify one’s experiences.

Yanos and his colleague Lauren Gonzales (as cited in Yanos, 2018) used the Mental Illness Microaggression Scale-Perpetrator version to measure microaggressions. They found that 62% of respondents endorsed patronizing behavior with mentally ill individuals by talking to them more slowly. Furthermore, 81% of respondents reported frequently reminding them to take their medication.

Mental health quiz

Prejudice comprises preconceived negative attitudes, feelings, and beliefs toward members of a marginalized group. These notions come from unsubstantiated opinions or stereotypes (Ritzer, 2021).

One way to combat prejudice and subsequent stigma is to learn more about the targeted group.

The following 10-question quiz will help dispel harmful attitudes and misunderstandings regarding mental illness. Dispelling myths can help reduce stigma, creating an environment of inclusiveness.

Take this mental health quiz from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Questions to ponder

- How does segregating groups of people in society impact your values?

- What do you stand to lose if you stand up for someone with mental illness? What would you gain?

- How does it make you feel when you hear about an individual with mental illness being stigmatized?

- What is the underlying fear surrounding mental illness stigma?

- What resources do you need to make a change?

- What is mental health stigma costing society?

While on the subject of interesting questions to ponder, you may find this article helpful as well: 72 Mental Health Questions for Counselors and Patients .

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Many people are uncertain about starting a conversation on mental illness and stigma. Below are ideas for getting started.

1. SAFE: Mental health facts for families

Because many veterans struggle with mental illness, Michelle Sherman and the Oklahoma Veterans Affairs Medical Center created the SAFE Program : Mental health facts for families.

The acronym SAFE stands for Support and Family Education. Each session provides questions and materials for a class or group.

In particular, session 18 helps families understand the stigma around mental illness (Sherman, 2008). The program includes facts about the impact of stigma on the family’s experience of mental illness and prompts compelling questions, such as:

- What has been the most significant consequence of your loved one’s mental illness?

- What kept them from seeking treatment?

This invaluable program and others like it help families and the diagnosed realize they are not alone, provide insightful information, and build empathy and compassion for their loved ones.

2. Discussion starter

This simple handout, Stigma Discussion Starters , analyzes what stigma looks like and means and asks questions about what it would feel like to have mental illness and experience stigma.

This handout can be used as a template for discussions in college classrooms, in the workplace, and in medical settings to create a deeper understanding of what mental health stigma looks and feels like.

3. Interactive website

The wonderfully interactive website Make It OK provides resources to help educate people about mental illness and videos on language to avoid. It provides various podcasts, questions, and interactions. For example, you can scroll down to take a quiz and also sign a pledge to do your part to erase stigma.

The site is also aimed at helping those struggling with mental illness, as it provides relatable stories and resources.

4. Helpful group activities

Mental health stigma has wide-ranging effects on those labeled and society. Dialogue is essential to effect change.

Talking circles

Talking circles are integral to restorative justice and help people connect with each other and themselves.

In Heart of Hope , Carolyn Boyes-Watson and Kay Pranis state (2010, p. 170), “Chronic conditions of unmet needs for dignity, respect, and basic necessities can induce the trauma response.” Unmet needs can lead to acting-out behaviors that can disconnect individuals from their true selves.

Boyes-Watson and Pranis (2010, p. 170) go on to say, “Acknowledging the harm of these structures and having an opportunity to tell the story of the harms in one’s life are essential in promoting resilience in the face of the harmful impacts.”

Talking circles are one way to listen and speak about societal injustices like mental illness stigma. Circles are used within the justice system, schools, and other contexts.

The process includes inviting members of the community and those harmed to sit together while they share personal stories and listen to the stories of others.

In order to address mental health stigma, the circle keeper could approach various topics such as respect, dimensions of identity, or empathy.

In this YouTube video, Kay Pranis captures the essence of talking circles and outlines the origins, objectives, and process.

Empathy Bingo

The Empathy Bingo worksheet provides an opportunity to demonstrate the difference between showing empathy and other responses. This activity works great in a therapeutic setting and other settings such as a classroom or the workplace.

The facilitator reads one of the 12 prepared scenarios and corresponding responses. Participants decide if the response exemplifies empathy or other choices provided, such as one-upping, correcting, or fixing it.

This exercise is a creative way to become aware of how our responses can be interpreted and how to build empathy, which is vital for reducing stigma.

The following books provide resources to understand mental illness and its stigma.

1. Written Off: Mental Health Stigma and the Loss of Human Potential – Philip T. Yanos

Written by Philip T. Yanos, the book conveys how the pervasive nature of stigma impacts those with mental illness, profoundly affecting their lives.

Yanos approaches the topic of stigma from the standpoint of social injustice, believing that when stigma prohibits mentally ill individuals from participating in society, it is not just a personal loss, but a communal one.

Yanos discusses negative attitudes and behaviors toward mental illness, community participation of those diagnosed, and ideas for changing perceptions.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Another Kind of Madness: A Journey Through the Stigma and Hope of Mental Illness – Stephen P. Hinshaw

Written by Stephen P. Hinshaw, it is a biographical depiction of his journey through his father’s mental illness.

After 18 years of silence, the life-changing revelation of his father’s mental illness came during a spring break from college.

Jolting as it was, it helped explain his father’s ups and downs and extended absences. It also awakened his journey to becoming a clinical and developmental psychologist and professor.

One way to internalize a lesson is through activities and exercises. Below are examples of both that can help formulate the building blocks of empathy and healing.

Positive Relationships Masterclass

Healthy relationships are crucial to individual wellbeing. The Positive Relationships Masterclass© is a coaching masterclass to help others build and maintain healthy relationships.

Participants will learn why positive relationships are crucial markers of wellbeing, the types of support needed, the benefits of building social capital resulting in stronger communities, perceptions about relationships, and how to manage relationships.

Learning to create and negotiate healthy relationships provides insight into relationship dynamics and helps change how individuals see and interact with others.

Recommended reading

If you too are intrigued by mental wellness, we have a great selection of articles that you will find interesting. Here is a short list of must-read articles:

- 19 Mental Health Exercises & Interventions for Wellbeing

- The Benefits of Mental Health According to Science

- 28 Mental Health Games, Activities & Worksheets (& PDF)

2 Worksheets

Telling an Empathy Story is a worksheet used in dyads or groups to build empathy through storytelling. Participants can use someone else’s story or a biography. The storyteller uses art to help convey emotions and then shares it with another or a group, thus learning empathy and allowing for self-expression through art.

The Compassion Formulation exercise encourages psychological and emotional wellbeing by bolstering self-compassion and compassion for others. Participants will explore aspects of past influences, primary fears, protective behaviors, and unintended outcomes.

An activity for kids

This class exercise called Group Circle allows kids to show kindness and enjoy its benefits through talking circles. Participants can experience empathy by talking about a time they felt different.

Positive relationship tools

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others build healthy relationships, check out this collection of 17 validated positive relationship tools for practitioners. Use them to help others form healthier, more nurturing, and life-enriching relationships.

17 Exercises for Positive, Fulfilling Relationships

Empower others with the skills to cultivate fulfilling, rewarding relationships and enhance their social wellbeing with these 17 Positive Relationships Exercises [PDF].

Created by experts. 100% Science-based.

The butterfly effect posits that positive shifts could ultimately create global waves of change.

This blog post presents a challenge and an opportunity. It contains questions, books, resources, and ideas to change perspectives on mental illness.

We can create a space for those struggling with mental illness to feel accepted, understood, and validated.

This change also transforms us by opening our minds and hearts and building empathy muscles. In addition, it builds social capital through communities where empathy trumps fear.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free .

Stigma affects those struggling with mental health, as it

- Limits participation in society

- Creates obstacles to seeking treatment

- Inhibits the ability to be authentic

Stigma is most often caused by:

- Lack of knowledge and understanding

- Lack of empathy

- Negative media portrayals

- Pejorative terms

If faced with stigma, the best way to cope is to:

- Seek professional help

- Find a supportive community

- Use coping mechanisms to reduce stress and anxiety

- Public stigma: “Patient” labeling and pejorative labeling

- Self-stigma: Feeling damaged, weak, or vulnerable; holding back from sticking up for yourself

- Structural stigma: Built into societal institutions

- Boyes-Watson, C., & Pranis, K. (2010). Heart of hope resource guide: Using peacemaking circles to develop emotional literacy, promote healing and build healthy relationships . Center for Restorative Justice at Suffolk University.

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (n.d.). SEL and mental health. Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/how-does-sel-support-your-priorities/sel-and-mental-health/.

- Dobson, K., & Stuart, H. L. (Eds.). (2021). The stigma of mental illness: Models and methods of stigma reduction . Oxford University Press.

- Evans, L., Chang, A., Dehon, J., Streb, M., Bruce, M., Clark, E., & Handal, P. (2023). The relationships between perceived mental illness prevalence, mental illness stigma, and attitudes toward help-seeking. Current Psychology , 1–10.

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums . Doubleday & Company.

- Gregory, H. (2020). Making a murderer: Media renderings of brain injury and Aaron Hernandez as a medical and sporting subject. Social Sciences & Medicine , 244 .

- Holcombe, M. (2023, August 9). What we can learn from Simone Biles’ mental health break . CNN. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://www.cnn.com/2023/08/09/health/biles-mental-health-break-wellness/index.html.

- Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., De Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., De Girolamo, G., Gluzman, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Kawakami, M., Karam, A., Levinson, D., Medina Mora, M. E., Oakley Browne, M. A., Posada-Villa, J., Stein, D. J., Adley Tsang, C. H., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., … Bedirhan Ustun, T. (2007). Life-time prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry, 6 (3), 168–176.

- O’Brien, D., & Fisher, J. (2019, February 19). 5 ways bosses can reduce the stigma of mental health at work . Harvard Business Review. Retrieved September 12, 2023, from https://hbr.org/2019/02/5-ways-bosses-can-reduce-the-stigma-of-mental-health-at-work.

- Ritzer, G. (2021). Essentials of sociology (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Sherman, M. D. (2008, April). Support and family education: Mental health facts for families . University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://www.ouhsc.edu/safeprogram/index.html.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023, April 24). Mental health myths and facts. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://www.samhsa.gov/mental-health/myths-and-facts.

- Yanos, P. T. (2018). Written off: Mental health stigma and the loss of human potential . Cambridge University Press.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

High-Functioning Autism: 23 Strengths-Based Daily Worksheets

Autism diagnoses are rising exponentially. A study by Russell et al. (2022) reported a 787% increase in UK diagnoses between 1998 and 2018. Similarly, 1 [...]

Treating Phobias With Positive Psychology: 15 Approaches

Phobophobia is a fear of phobias. That is just one in our list of 107 phobias. Clearly a person suffering from phobophobia has a lot [...]

How to Fuel Positive Change by Leveraging Episodic Memory

Some researchers believe that our memory didn’t evolve for us to only remember but to imagine all that might be (Young, 2019). Episodic memory is [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (22)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (37)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Mental Health Stigma

How the stigma of mental illness has evolved over time, anthropologist roy richard grinker explores the roots of stigma in his new book..

Posted January 12, 2021

Though progress has been made in recent years, mental illness remains highly stigmatized—the mentally ill are often victims of shame , marginalization, or outright mistreatment. In his upcoming book Nobody's Normal: How Culture Created the Stigma of Mental Illness, George Washington University anthropologist Roy Richard Grinker explores the roots of mental illness stigma around the world and highlights the cultural changes that have, he argues, brought us to the cusp of reimagining our relationship with neurodiversity and mental illness.

How does culture create stigma?

Evolutionary biologists would say that it’s natural for us to be afraid of some people. But what we are afraid of varies from society to society.

Most of the world doesn’t blame the individual for their suffering. Most of the world blames the family at large, God, a malevolent spirit, karma, or the stress of war, poverty, or an abusive relationship. It’s culture that teaches us how to seek blame, and how to explain differences. And if we explain differences in this very American way, that the individual is responsible for everything they succeed and fail in, it’s no surprise that people don’t want to seek care for certain conditions, especially conditions that threaten the ideals of being independent and achieving—the ideal American.

What’s an example of a condition that’s treated differently in different cultures?

I’ll give you an example of something that’s treated completely differently in the same location by a medical doctor and by his community. A man I’ll call Tamzo, who lives in rural Namibia, has what we would call schizophrenia. He walks 20 kilometers to the village once a month to get antipsychotic medicine. The Western doctor there writes down his diagnosis as schizophrenia. But at home he is thought to be the victim of a curse that somebody placed on their village that settled randomly on Tamzo. In his family and his village, as long as he is not hearing voices, he’s not considered at all to be sick. Whereas in the clinic, it’s “once labeled, always labeled.”

Your book discusses the relationship between capitalism and stigma. How has it informed beliefs about mental illness?

When capitalism took hold, we started to value individual autonomy and productivity for everybody. Before that, we didn’t hold a person responsible for all of their differences and all of their successes and failures. One of the things that characterized the first asylums in the 1700s, particularly in England and France, were that they were for people who violated the goals of productivity. They were idle, they didn’t work, or they were criminals. The asylums didn’t separate people into these different categories; they were all just the idle. It was only after humanitarian reformers sought to separate out the criminals from the non-criminals that you finally had people with mental illness (what was called insanity) by themselves, and then scientists could see them.

One of the problems for people with disabilities in general is what Alexis de Tocqueville observed in the early 1800s: In the U.S., the hero is the individual. People with disabilities aren’t necessarily always able to be independent. By the very nature of capitalism, the person who depends on others, who lives with others, or who isn’t an efficient worker is considered to be a failure.

How might that manifest today?

Something that really affects people is the idea that they can’t live up to capitalist values. We learn that certain occupations are valued more than others. In the book, I tell a story about my daughter with autism , Isabel. She loves to clean, and she’s very good at it. She got an internship at CVS, so the employer and my wife and I went over her duties. Isabel said, “When I get here in the morning, I’m a cleaning lady.” The employer snapped at her and said, “You are not a cleaning lady—you are a retail associate!”

It was a perfect example of how we learn that some ways of being are more valued than others. Until that moment, Isabel hadn’t realized that there was anything wrong with calling yourself a cleaning lady. There is nothing wrong with that.

The book also discusses the influence of war. How have wars altered the way people think of mental illnesses?

Wars can lead to massive transformations in all areas of life, including how we think about human behavior. The whole field of psychological testing derives from World War I and World War II. Various kinds of therapies that we take for granted, like community therapy , milieu therapy, and many other therapeutic techniques and medical technologies, all have their origins in wars.

The other thing is that each war creates new symptoms. In the Civil War, people experienced stress by having “soldier’s heart” or nostalgia . There was shell shock in World War I, war neurosis in World War II, and PTSD after Vietnam. These ideas come to fruition within the wars, but then they generalize to the community at large. Wars say that you can be strong, the ideal patriotic masculine warrior—and you’re still a human being that is going to be distressed by trauma .

Are we at a transition point in eradicating stigma?

I hope so. There’s been a real increase in the number of people who want to become psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. And I have a sense that, especially among young people, it’s expected to talk openly about things that people used to be ashamed of. Celebrities and athletes have been coming forward, like Lady Gaga, Bruce Springsteen, Jane Fonda, and Metta Sandiford-Artest.

But my real heroes are the people like my students who, on the first day of class, tell everyone, “I have Tourette syndrome, so please don’t be too upset when I say something that is inappropriate. I’m trying to control it, but sometimes I’ll say a swear word.” Or the student who says, “Getting diagnosed with ADHD was one of the best days of my Freshman year. For the first time, somebody saw that I wasn’t lazy or stupid. I just needed support.”

I’m not as optimistic about the most serious conditions. Things like schizophrenia and substance abuse threaten the ideals of capitalist society, that we should always be in control and masters of ourselves.

What led to this transition point?

So many things have changed the way we view human suffering and disability in general. You can take a particular case, like autism, and see how much our changing views of autism have come about because of our changing economies. The people who used to be denigrated for being "computer nerds" are now our heroes.

We’re also appreciating remote work. We’re starting to value stay-at-home parents more, and stay-at-home dads, which used to be considered weird. Why is that important? Being able to value a stay-at-home dad is to say that you are not necessarily disabled if you are not engaged in wage labor. You’re not a bad person if you’re not the sole breadwinner. The person with the disability who lives with their family, who doesn’t move out at the arbitrary age of 18, isn’t seen as violating some set of social rules. The disability rights movement, which includes the rights of people to have new identities, is also expanding the view that we all exist on a spectrum and that we can change over time. Being human means having some fluidity and change. Our views of mental illness are following that as well. It’s this openness and fluidity that I see as the tide that’s raising all boats.

Which is not to say that people aren’t suffering or discriminated against due to societal beliefs. But we’re more aware that that’s a form of suffering that we can eventually have control over. Because culture created it. If culture created it, we can change it.

How can people continue striving to eliminate stigma?

One of the things that bothers me is how much effort has been put toward eradicating stigma through education and awareness, like public service announcements and commercials. There’s nothing wrong with that, but Patrick Corrigan at the University of Illinois wrote a book called The Stigma Effect, in which he’s pretty clear that those things don’t work very well.

So, what does work? When we have interactions. We can get all the education we want, but if we don’t have proximity and interaction with networks and family who have mental illness and talk about them, we’re not going to get where we want to go.

One substitute for proximity is cinematic and television depictions. When I started working on autism in South Korea in the early 2000s, nobody would talk about mental illnesses. On autism, they would say, “Oh we don’t have that here,” or “We do, but it’s very rare.” If I heard somebody had a friend or colleague with autism, they would say, “They have autism, but you can’t talk to them because I never mentioned that I know.” It was so secretive. Today we’re seeing change in South Korea led in part by cinematic and television depictions. The Good Doctor, for example, was invented in Korea. It showed autism in a way that it had never been depicted before.

LinkedIn image: Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock

Abigail Fagan is a Senior Associate Editor at Psychology Today .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

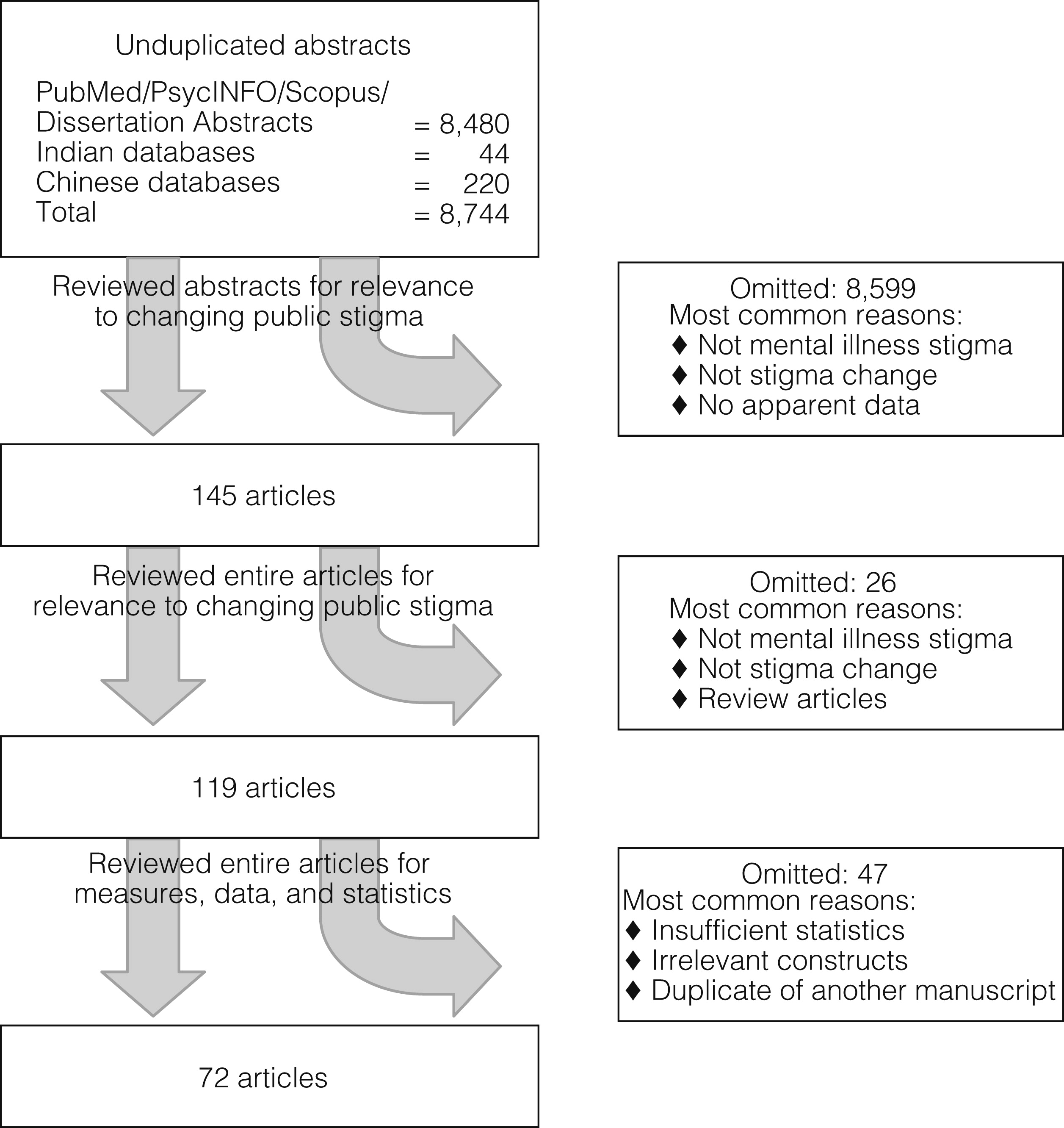

Changes shown on attributions (A), preferences for social distance (B), and perceptions of dangerousness (C), by condition. Significant changes ( P < .05) from one wave to the next (eg, 1996 to 2006) are indicated with heavy lines. Changes that were significant across the full time period (ie, 1996-2018), but not across successive waves, are indicated with a dashed line. All estimates are weighted. Data collected from the US National Stigma Studies. 12

The solid line provides the estimated trend across age groups (A), over time (B), and across cohorts (C). The shaded areas around the lines represent CIs, from light (95%) to dark (75%). Estimated cohort trends, which represent cohort-specific deviations from age and period trends, were obtained by averaging over all of the age-by-period combinations for a given cohort. For convenience, cohorts are indexed according to the first birth year in the birth cohort. The 1907 and 1917 cohorts were pooled to increase cell sizes. In all cases, higher values indicate a preference for greater social distance; lower values indicate the reverse. All estimates are weighted and adjust for respondents’ educational level, sex, and race and ethnicity, as well as the education, sex, and race and ethnicity of the person described in the vignette. Data collected from the US National Stigma Studies.

eMethods. Materials and Methods

eTable 1. Unadjusted Survey Year Differences

eTable 2. Adjusted Survey Year Differences

eTable 3. Model Fit of Candidate Models in APC Analyses

eTable 4. Deviation Magnitude Tests

eTable 5. Average Cohort Deviation Across Periods

eTable 6. Age and Period Main Effects

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Pescosolido BA , Halpern-Manners A , Luo L , Perry B. Trends in Public Stigma of Mental Illness in the US, 1996-2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2140202. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40202

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Trends in Public Stigma of Mental Illness in the US, 1996-2018

- 1 Department of Sociology, Indiana University, Bloomington

- 2 Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park

Question What changes in the prejudice and discrimination attached to mental illness have occurred in the past 2 decades?

Findings In this survey study of 4129 adults in the US, survey data from 1996 to 2006 showed improvements in public beliefs about the causes of schizophrenia and alcohol dependence, and data from a 2018 survey noted decreased rejection for depression. Changes in mental illness stigma appeared to be largely associated with age and generational shifts.

Meaning Results of this study suggest a decrease in the stigma regarding depression; however, increases and stabilized attributions regarding the other disorders may need to be addressed.

Importance Stigma, the prejudice and discrimination attached to mental illness, has been persistent, interfering with help-seeking, recovery, treatment resources, workforce development, and societal productivity in individuals with mental illness. However, studies assessing changes in public perceptions of mental illness have been limited.

Objective To evaluate the nature, direction, and magnitude of population-based changes in US mental illness stigma over 22 years.

Design, Setting, and Participants This survey study used data collected from the US National Stigma Studies, face-to-face interviews conducted as 1996, 2006, and 2018 General Social Survey modules of community-dwelling adults, based on nationally representative, multistage sampling techniques. Individuals aged 18 years or older, including Spanish-speaking respondents, living in noninstitutionalized settings were interviewed in 1996 (n = 1438), 2006 (n = 1520), and 2018 (n = 1171). The present study was conducted from July 2019 to January 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures Respondents reacted to 1 of 3 vignettes (schizophrenia, depression, alcohol dependence) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition , criteria or a control case (daily troubles). Measures included beliefs about underlying causes (attributions), perceptions of likely violence (danger to others), and rejection (desire for social distance).

Results Of the 4129 individuals interviewed in the surveys, 2255 were women (54.6%); mean (SD) age was 44.6 (16.9) years. In the earlier period (1996-2006), respondents endorsing scientific attributions (eg, genetics) for schizophrenia (11.8%), depression (13.0%), and alcohol dependence (10.9%) increased. In the later period (2006-2018), the desire for social distance decreased for depression in work (18.1%), socializing (16.7%), friendship (9.7%), family marriage (14.3%), and group home (10.4%). Inconsistent, sometimes regressive change was observed, particularly regarding dangerousness for schizophrenia (1996-2018: 15.7% increase, P = .001) and bad character for alcohol dependence (1996-2018: 18.2% increase, P = .001). Subgroup differences, defined by race and ethnicity, sex, and educational level, were few and inconsistent. Change appeared to be consistent with age and generational shifts among 2 birth cohorts (1937-1946 and 1987-2000).

Conclusions and Relevance To date, this survey study found the first evidence of significant decreases in public stigma toward depression. The findings of this study suggest that individuals’ age was a conservatizing factor whereas being in the pre–World War II or millennial birth cohorts was a progressive factor. However, stagnant stigma levels for other disorders and increasing public perceptions of likely violence among persons with schizophrenia call for rethinking stigma and retooling reduction strategies to increase service use, improve treatment resources, and advance population health.

Stigma, the prejudice and discrimination attached to devalued conditions, has been consistently cited as a major obstacle to recovery and quality of life among people with psychiatric disorders. 1 - 3 Stigma has been implicated in worsening outcomes for people with serious mental illness, 4 , 5 with nearly 40% of this population reporting unmet treatment needs despite available effective treatments. 6 , 7 Although some psychiatrists claim that stigma has decreased 8 or is irrelevant, 9 stigma remains concerning to health care professionals, patients, advocacy groups, and policy makers. Research has not supported claims of a decrease in stigma. 3 Moreover, national levels of public stigma have been associated with treatment-seeking intentions and experiences of discrimination reported by people with mental illness. 10 , 11 Findings on antistigma interventions also reflect the persistence of stigma 3 , 12 , 13 ; the unclear, limited, or short-term effectiveness of both large-scale messaging and small-scale interventions 12 - 16 ; and the lack of scalability of many such programs. Herein, we examine US public stigma over a 22-year period to provide a detailed assessment of changes in the nature and magnitude of public stigma over 2 decades for major mental health disorders.

The US National Stigma Studies (US-NSSs) use the General Social Survey (GSS), a biannual, household-based, multistage, cluster-sampled interview project providing nationwide, representative data on adults (age ≥18 years) living in noninstitutionalized settings in the continental US. 12 Face-to-face interviews for the US-NSSs were conducted by trained interviewers using the pencil/paper mode in 1996 (n = 1444; response rate, 76.1%) and computer-assisted personal interview format in 2006 (n = 1522; response rate, 71.2%) and 2018 (n = 1173; response rate, 59.5%). The GSS follows the American Association for Public Opinion Research ( AAPOR ) reporting guideline, which the present study followed. Mode effects, tested between 1996 and 2006, were minimal 17 and analyses to identify potential biases resulting from changing response rates did not identify problems. 18 Weights are provided and used where appropriate. Respondents receive an information page in English/Spanish and are asked for their consent to begin the interview. Institutional review board approval for the GSS and this study is held at NORC and at Indiana University. The present study was conducted from July 2019 to January 2021.

The US-NSSs used a survey experimental design using vignettes describing a fictitious person with behaviors meeting Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition 19 criteria for schizophrenia, major depression, alcohol dependence, and a daily troubles control (eMethods in the Supplement ). 20 , 21 This vignette strategy avoids identifying the nature of the problem, allowing for data collection on knowledge, recognition, and labeling by respondents. 20 , 21 The vignette character’s psychiatric condition as well as their self-reported sex (man or woman), race (African American, Hispanic, or White), and educational level (eighth grade, high school, or college) were randomly varied and assigned as experimental characteristics in the stimulus. These data were not reported or collected in the interview. One vignette per respondent was read aloud by the interviewer and printed on a card given to the respondent who was then asked a series of questions.

Three sets of dependent variables operationalized stigma. First, attributions targeted respondents’ evaluation of likely scientific causes (chemical imbalance and genetics) as well as their recognition of the situation as a mental illness. Other potential moral/social explanations (bad character, God’s will, ups and downs of life, and way raised [all coded 1 if very/somewhat likely; 0 otherwise]) were also included. Second, dangerousness asked about the likelihood that the vignette person would do something violent toward others (coded 1 if very/somewhat likely; 0 otherwise). Third, social distance, the most common measure of stigma, measured respondents’ unwillingness to work closely with the vignette person on a job, live next door to them, spend an evening socializing with them, marry into their family, make friends with them, or live near a group home (categories collapsed into not willing/do not know [1] or willing [0]); details are reported in eTable 1 in the Supplement . Additional analyses used an overall social distance, factor-analytic scale for depression (1-factor solution, factor loadings ranging between 0.47 and 0.80, Cronbach α = .85).

Statistical analyses evaluated changes across years. Because data were weighted, a design-based F statistic that used the second-order Rao and Scott 22 correction was used to test the equality of raw percentages. To adjust for possible sociodemographic shifts between survey years and examine disparities, logistic regression models were fit. Differences in the estimated probabilities for outcomes were calculated, holding control variables at sample-specific means. The delta method was used to determined 95% CIs. To explore subgroup differences in trends, we fit a series of regression models that included interactions between time periods and respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics. Model estimates were used to calculate estimated probabilities of preferring social distance at each time point (1996, 2006, and 2018) and for each group (eg, men vs women), as well as group-specific changes over time and group differences in trends. Owing to the population representation of racial and ethnic groups in the US population, African American and Hispanic groups were collapsed into a non-White category in the subgroup analysis to avoid estimation problems within the vignette-specific analyses. Variance estimates were again obtained via the delta method. In addition, an exploratory age, period, and cohort analysis applied the age-period cohort (APC)–I method of Luo and Hodges 23 to assess the unique contribution of birth cohorts to overall trends in the preferences of US residents for social distance. Aligned with Ryder’s view that a cohort’s meaning is “implanted in the age-time specification,” 24 [p861] this approach quantifies cohort associations as the differential outcomes of time periods depending on age groups (eMethods in the Supplement ). Different from conventional APC models that assume cohort associations occur independently of period and age, the APC-I approach acknowledges the association of age, period, and cohort, as originally proposed by Ryder, which makes the approach useful for identifying factors that might be attributed to cohort membership. The total sample size of the individual-level APC analysis is 4134, with the number of participants per age-period combination ranging between 126 and 345. Hypothesis tests were all 2 sided. The APC analysis was carried out using R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Analysis). The rest of the analysis—including data cleaning and variable transformations—was performed using Stata, version 16 (StataCorp LLC). Findings at P < .05 were considered significant.

Table 1 provides the sociodemographic profile of US NSS respondents across the 3 survey periods: 1996 (n = 1438), 2006 (n = 1520), and 2018 (n = 1171). Representation of age, sex, race and ethnicity, and educational level were roughly in line with US Census Bureau data (1996: men, 642 [44.6%]; women, 796 [55.4%]; mean [SD] age, 44.7 [17.0] years; 2006: men, 666 [43.8%]; women, 854 [56.2%]; mean [SD] age, 46.7 [17.0] years; men, 566 [48.3%]; women, 605 [51.7%]; mean [SD] age, 49.0 [17.4] years). The slight overrepresentation of women across time has been commonly seen in interview studies. The GSS did not collect specific ethnicity data until 2000; from then, race and ethnicity categories comprised non-White (2006: 425 [28.0%]; 2018: 322 [27.5%]) and White (2006: 1095 [72.0%]; 2018: 849 [72.5%]) individuals. Overall mean (SD) age was 44.6 (16.9) years.

Figure 1 depicts unadjusted changes across survey waves. Adjusted changes reveal few differences compared with unadjusted results and are reported here (eTable 2 in the Supplement ). Scientific attributions (chemical imbalance, genetics) were high and selected by increasing percentages of US residents, with the major increase occurring in the first period (1996-2006). Overall, in the earlier period (1996-2006), scientific attributions (eg, genetics) for schizophrenia (11.8%), depression (13.0%), and alcohol dependence (10.9%) increased. The only case in which public endorsement was lower than 50%, but still substantial, was for the control situation: daily troubles ( Figure 1 A; eTable 1 in the Supplement ). These results may suggest a medicalization of life problems. However, this early significant increase in the category of chemical imbalance was followed by a decrease later.

Although problem recognition increased only for schizophrenia in the first period and for alcohol dependence only in the second period, the levels were high for all mental illnesses. No change was documented for depression, with recognition already high, or for the control, in which depression was considered not warranted, signaling a distinct difference in the public response to nonclinical problems ( Figure 1 A).

Social and moral attributions were endorsed by relatively few respondents with little change over time ( Figure 1 A). Significantly fewer respondents cited ups and downs as a cause of depression or selected God’s will. The latter choice decreased significantly in the first period for daily troubles, even as the way an individual was raised increased significantly later. Alcohol dependence, however, was increasingly stigmatized, marked by significant change in respondents simultaneously citing bad character (18.2%) and ups and downs of life (11.3%) (eTable 2 in the Supplement ). Overall, trends suggest increasing mental health literacy, including distinguishing between daily problems and mental illness.

Social distance showed little change over time, except for depression ( Figure 1 B). In the later period (2006-2018), the desire for social distance decreased for depression in work (18.1%), socializing (16.7%), friendship (9.7%), family marriage (14.3%), and group home (10.4%) (eTable 2 in the Supplement ). For depression, the decreases were statistically significant and substantial. Reductions occurred in the later period, spanning all domains except neighbor, which was already low. Other minor changes in a direction indicating a higher stigma were in evidence early. This change included an increase in social distance for schizophrenia as neighbor and having the vignette person marry into the family ( Figure 1 B; eTable 2B in the Supplement ).

Inconsistent, sometimes regressive change, was observed, particularly regarding dangerousness for schizophrenia ( Figure 1 C) (1996-2018: 15.7% increase, P ≤ .001) and bad character for alcohol dependence (1996-2018: 18.2% increase, P ≤ .001).

The similarity between unadjusted and adjusted results suggests that sociodemographic characteristics offer little power in explaining stigma. Table 2 reports the results of analyses of subgroup factors for race and ethnicity, sex, age, and educational attainment (vignette person characteristics controlled). There were no significant differences in the overall time trends for sociodemographic groups, but a few associations were observed within periods. More men endorsed stigma (ie, in the most recent period for socializing, in the middle period for neighbor, and in the earliest period for friendship and group home support) compared with women. More respondents who self-reported race as non-White desired social distance from individuals with depression as neighbors in the most recent period.

The most consistent sociodemographic association was noted with age. Older individuals in each period were significantly more unwilling to have the vignette person marry into the family. This response did not change over time. In addition, more individuals with lower levels of education endorsed stigma in the most recent period (neighbor) and the middle period (marriage into the family).

In Figure 2 , a composite social distance scale depicts possible explanations of the stigma decrease for depression (eTables 3-6 in the Supplement ). Age and social distance appeared to be conservatizing factors ( Figure 2 A). Distinct period responses were noted, especially from 2006 to 2018, when stigma toward depression decreased significantly (Figure 2B). Two cohorts were more likely than expected to report lower stigma—the Silent Generation (part of the 1937-1946 birth cohort, after the Greatest Generation but before the Baby Boomers) and Millennials (1987-2000 birth cohort) ( Figure 2 C). The average deviation for the 1937-1946 birth cohort was −0.12 (SE, 0.05) ( P = .02), and the average deviation for the 1987-2000 birth cohort was−0.21 (SE, 0.08) ( P = .01) (eTable 5 in the Supplement ).

Our analyses identified both stability and change in stigma over the 22-year period from 1996 to 2018. Five robust and clear patterns emerged. First, the period around the turn of the century (1996-2006) saw a substantial increase in the public acceptance of biomedical causes of mental illness. Survey participants were more likely to recognize problems as mental illness and draw a line between daily troubles and diagnosable conditions. These changes mark greater scientific beliefs and a decrease in stigmatizing attributions, but no reduction in social rejection. Overall, trends suggest increasing mental health literacy, including distinguishing between daily living problems and mental illness, aligning with earlier research. 25 , 26 Second, the more recent period (2006-2018) documented, to our knowledge, the first significant, substantial decrease in stigma, albeit for one mental illness diagnosis: major depression. Fewer survey respondents expressed a desire for social distance from people with depression across nearly all domains, including work and family. Considered in the context of previous research, these decreases are statistically significant, substantively large, and persist in the presence of controls. Other disorders did not see reductions in social distance, and public perceptions of dangerousness for schizophrenia and moral attributions for alcohol dependence increased.

Third, respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics offered little insight into stigma, generally, or into observed decreases for depression. What is unusual about these findings is the absence of subgroup differences, suggesting a broad shift in the respondents’ thinking about depression. This absence of sociodemographic differences may be unexpected, but it supports findings from earlier NSSs. 10 , 27

Fourth, change over time may be associated with age as a conservatizing factor, 28 , 29 a cohort process in which older, more conservative individuals are replaced by younger, more liberal US residents, 29 , 30 and/or a period outcome stemming from broad shifts that are uniformly seen regarding social distance discriminatory predispositions across age and cohort. Although prior research tended to assume the observed trends primarily reflect a period-based process, we used the APC-I method to explore unique cohort patterns in public stigma of mental illness. Disaggregating the effects of age, period, and cohort revealed age as a conservatizing factor also seen in a parallel German study, 12 and a liberalizing tendency among both pre-WWII birth cohorts (referred to by demographers as the Silent Generation) and the most recent birth cohorts (Millennials), and a recent period outcome.

Fifth, although findings for depression are notable, other results may raise concerns. For schizophrenia, there has been a slow shift toward greater belief of dangerousness. Although not statistically significant in either of the time periods, the increase was substantial and relatively large over the entire period (approximately 13%), a finding analyzed in detail elsewhere. 31 The results for alcohol dependence are similarly mixed. Although there was an increase in the selection of alcohol dependence as a mental illness with chemical and genetic roots, the problem was also trivialized as ups and downs. Moreover, we observed a return to a moral attribution of bad character in the first period that remain stable into the second period.

This study has limitations. Responses to survey vignettes reflect attitudes, beliefs, and predispositions—not behavior. The lack of importance of sociodemographic characteristics may signal insensitivity in a vignette approach or in stigma measurement. 32 - 34 Although subgroup differences are widely believed to exist, such research is rare and often not generalizable. Yet, although our estimates of sociodemographic outcomes are somewhat inefficient owing to sample size constraints, power analyses indicate that they are adequately powered to detect very small effects overall (Cohen h = 0.12), and small to moderate associations within vignette condition (Cohen h = 0.25) (eMethods in the Supplement ). In addition, our vignettes are designed to capture public perceptions of behavior changes that typically occur with the onset of mental illness. Public response might differ if the vignettes included information about help-seeking and eventual recovery. Research that specifically targeted this limitation revealed a small but statistically significant lowering of public stigma when vignette persons were described as being in treatment or recovery. 35

Other limitations must also be considered. Decreasing response rates present a challenge to researchers who seek to model trends over time in attitudes or behaviors. As noted, GSS response rates decreased approximately 16% over the 22-year period in question. If GSS respondents were somehow increasingly selected on tolerance for individuals with mental illness, finding stigma change would be likely even in the absence of actual change. This explanation seems unlikely given our results. We found respondents’ attitudes toward mental illness were more accepting in some cases (eg, depression), but less accepting in others (eg, schizophrenia). Even for depression, in which change was found across social venues, the degree to which that happens varied greatly. If findings were an artifact of a simple sample selection process, we would not expect to observe this level of complexity. Trends over time would be more consistent across conditions, and differences between social domains would be less pronounced.

Equally important, although it may be tempting to associate the changes in mental health literacy in the earlier period with the stigma reduction for depression in the latter period, doing so would be premature. These data cannot support claims about lag effects owing to the GSS’s cross-sectional design. In addition, previous work, which examined this issue in detail in the earlier period alone, could document neither individual nor aggregate associations between accepting scientific attributions for mental illness and stigma levels. 10

Despite limitations, these findings have important implications for research and treatment as well as antistigma program and policy efforts. First and foremost, the results of this study suggest that public stigma can change. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first indications that revise the larger cultural climate of prejudice and discrimination without the coordinated, translational, and research-monitored program of stigma reduction used in other Western nations. 3 , 12 , 13 Research and antistigma efforts require content retooling to make use of what is known and address the most problematic and unique aspects of stigma. In the US, controversial and structural aspects of mental illness stigma have rarely been addressed. Not only are perceptions of violence increasing for schizophrenia, individuals with schizophrenia likely face the greatest resistance in dismantling public, legal, policy, treatment, and resource barriers. Furthermore, calls for tailoring efforts to diverse or specialized populations may be limited by a thin, unrepresentative, and contradictory scientific base. 36 , 37 Data gaps in our analysis signal the need for novel stigma targets in research, whether new measures or populations widely believed to hold distinct ideas about mental illness and stigma. Our results also raise questions on how the progress reported herein can be accelerated and regressive shifts reversed. These results suggest that we must be realistic because societies change slowly and change efforts must be persistent and sustainable. Randomized clinical trial–based antistigma research often reports positive findings in typical inoculation-style programs but confronts effects that are extinguished over time. 3 , 38

The NSSs have served as the de facto primary data source about public stigma in the US for the past 2 decades. In this analysis of 22 years of survey data, we found a significant decrease in public stigma toward major depression and increased scientific attribution for schizophrenia, major depression, and alcohol dependence. Our findings are consistent with the claims of Braslow et al 5 that what the public believes and knows often aligns with science (ie, increasing agreement with scientific attributions) but may fail to influence their attitudes and behavior (ie, desire for social distance from individuals with mental illness, except depression). The societal and individual effects of stigma are broad and pervasive. Stigma translates into individual reluctance to seek care, mental health professional shortages, and societal unwillingness to invest resources into the mental health sector. Yet, the research, teaching, and programming resources targeted to redress prejudice and discrimination remain a low priority, small in scale, and individually focused. 39 With indications that the level of stigma may be reducing, strategies to identify factors associated with the decrease in stigma for depression, to address stagnation or regression in other disorders, and to reach beyond current scientific limits are essential to confront mental illness’s contribution to the global burden of disease and improve population health.

Accepted for Publication: October 27, 2021.

Published: December 21, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40202

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2021 Pescosolido BA et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Bernice A. Pescosolido, PhD, Department of Sociology, Indiana University, 1022 E Third St, Bloomington, IN 47401 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Drs Pescosolido and Halpern-Manners had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Pescosolido, Halpern-Manners, Luo.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Pescosolido, Halpern-Manners.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Halpern-Manners, Luo.

Obtained funding: Pescosolido, Perry.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Pescosolido, Perry.

Supervision: Pescosolido.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Luo reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: Support for the study was provided by the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (formerly National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression) Distinguished Investigator Award and from Indiana University Network Science Institute (Dr Pescosolido), and base support and supplement from the National Science Foundation to the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) for the General Social Survey (GSS) and the National Stigma Studies.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Information: All GSS data are available from NORC ( https://gss.norc.org ) and the GSS data explorer ( https://gssdataexlporer.norc.org ).

Additional Contributions: We thank Alejandra Laszlo Capshew, MS (Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services Research), who assisted with project management; the College of Arts and Sciences and the Sociomedical Sciences Research Institute at Indiana University provided infrastructural support; and Tom W. Smith, PhD, and Jaesok Son, PhD (NORC at the University of Chicago), provided project assistance as key members of the NORC GSS Team. No financial compensation was provided.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Challenging the Public Stigma of Mental Illness: A Meta-Analysis of Outcome Studies

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, conclusions, three approaches to change, past reviews.

Effect size analysis

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) | Range (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Research participants | ||

| Age (M±SD) | 27.7±10.4 | 15–49 |

| Female | 58.7±18.4 | 3–100 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| European or European American | 61.1±27.1 | 0–95 |

| African or African American | 21.1±29.8 | 0–100 |