JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Hello! You are viewing this site in English language. Is this correct?

Explore the Levels of Change Management

9 Successful Change Management Examples For Inspiration

Updated: August 2, 2024

Published: January 3, 2024

Welcome to our guide on change management examples, pivotal for steering through today's dynamic business terrain. Immerse yourself in the transformative power of change management, a tool for resilience, growth, innovation, and employee morale enhancement.

This guide equips you with strategies to promote an innovative, adaptable work environment and boost employee morale for lasting organizational success.

Uncover diverse types of change management with Prosci's established methodology and explore real-world examples that illustrate these principles in action.

What is Change Management?

Change management is a strategy for guiding an organization and its people through change. It goes beyond top-down orders, involving employees at all levels. This people-focused approach encourages everyone to participate actively, helping them adapt and use changes in their everyday work.

Effective change management aligns closely with a company's culture, values, and beliefs.

When change fits well with these cultural aspects, it feels more natural and is easier for employees to adopt. This contributes to smoother transitions and leads to more successful and lasting organizational changes.

Why is Change Management Important?

Change management is pivotal in guiding organizations through transitions, ensuring impactful and long-lasting results.

For example, a $28B electronic components and services company with 18,000 employees realized the importance of enhancing its processes. They knew to adopt more streamlined, efficient approaches, known as Lean initiatives .

However, they encountered challenges because they needed a more structured method for effectively managing the human aspects of these changes.

The company formed a specialized group focused on change to address their challenges and initiate key projects. These projects aligned with their culture of innovation and precision, which helped ensure that the changes were well-received and effectively implemented within the organization.

Matching change management to an organization's unique style and structure contributes to more effective transformations and strengthens the business for future challenges.

What Are the Main Types of Change Management?

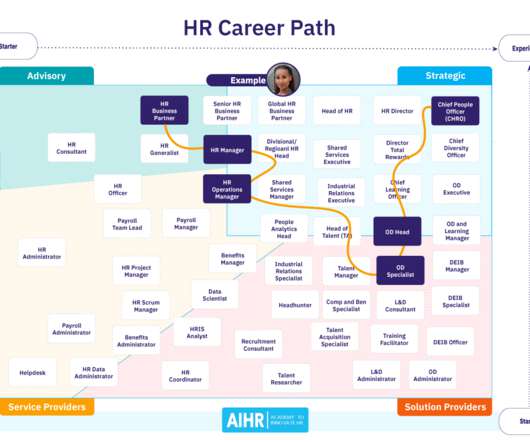

Discover Prosci's change management models: from individual application and organizational strategies to enterprise-wide integration and effective portfolio management, all are vital for transformative success.

Individual change management

At Prosci, we understand that change begins with the individual.

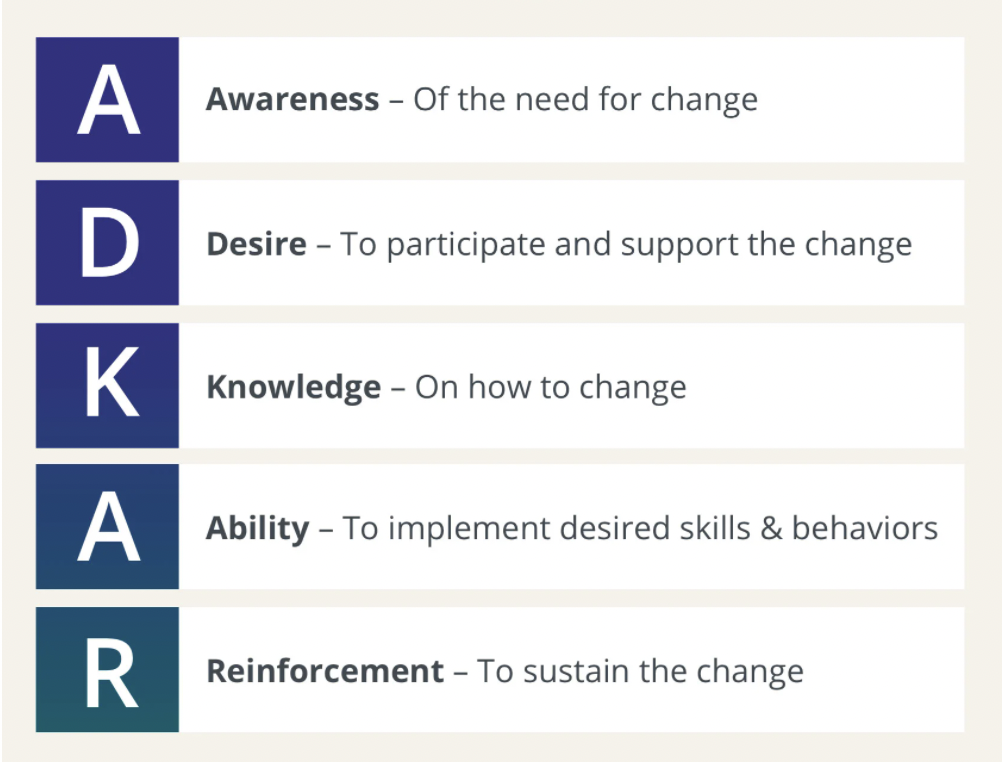

The Prosci ADKAR ® Model ( Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability and Reinforcement ) is expertly designed to equip change leaders with tools and strategies to engage your team.

This model is a framework that will guide and support you in confidently navigating and adapting to new changes.

Organizational change management

In organizational change management , we focus on the core elements of your company to fully understand and address each aspect of the change.

Our approach involves creating tailored strategies and detailed plans that benefit you and manage you to manage challenges effectively, which include:

- Clear communication

- Strong leadership support

- Personalized coaching

- Practical training

Our strategies are specifically aimed at meeting the diverse needs within your organization, ensuring a smooth and well-supported transition for everyone involved.

Enterprise change management capability

At the enterprise level, change management becomes an embedded practice, a core competency woven throughout the organization.

When you implement change capabilities:

- Employees know what to ask during change to reach success

- Leaders and managers have the training and skills to guide their teams during change

- Organizations consistently apply change management to initiatives

- Organizations embed change management in roles, structures, processes, projects and leadership competencies

It's a tactical effort to integrate change management into the very DNA of an organization—nurturing a culture that's ready and able to adapt to any change.

Change portfolio management

While distinct from project-level change management, managing a change portfolio is vital for an organization to stay flexible and responsive.

It’s like having a bird's-eye view of all ongoing changes, prioritizing them effectively, allocating resources judiciously, and ensuring each aligns with the organization's fundamental goals. This holistic approach ensures that change is managed and optimized for the best possible outcome .

9 Dynamic Change Management Success Stories to Revolutionize Your Business

Prosci case studies reveal how diverse organizations spanning different sectors address and manage change. These cases illustrate how change management can provide transformative solutions from healthcare to finance:

1. Hospital system

A major healthcare organization implemented an extensive enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and adapted to healthcare reform. This case study highlights overcoming significant challenges through strategic change management:

Industry: Healthcare Revenue: $3.7 billion Employees: 24,000 Facilities: 11 hospitals

Major changes:

- Implemented a new ERP system across all hospitals

- Prepared for healthcare reform

Challenges:

- Managing significant, disruptive changes

- Difficulty in gaining buy-in for change management

- Align with culture: Strategically implemented change management to support staff, reflecting the hospital's core value of caring for people

- Focus on a key initiative: Applied change management in the electronic health record system implementation

- Integrate with existing competencies: Recognized change leadership as crucial at various leadership levels

This example shows that when change management matches a healthcare organization's values, it can lead to successful and smooth transitions.

2. Transportation department

A state government transportation department leveraged change management to effectively manage business process improvements amid funding and population challenges. This highlights the value of comprehensive change management in a public sector setting:

Industry: State Government Transportation Revenue: $1.3 billion Employees: 3,000 Challenges:

- Reduced funding

- Growing population

- Increasing transportation needs

Initiative:

- Major business process improvement

Hurdles encountered:

- Change fatigue

- Need for widespread employee adoption

- Focus on internal growth

- Implemented change management in process improvement

This department's experience teaches us the vital role of change management in successfully navigating government projects with multiple challenges.

3. Pharmaceuticals

A global pharmaceutical company navigated post-merger integration challenges. Using a proactive change management approach, they addressed resistance and streamlined operations in a competitive industry:

Industry: Pharma (Global Biopharmaceutical Company) Revenue: $6 billion Number of employees: 5,000

Recent activities: Experienced significant merger and acquisition activity

- Encountered resistance post-implementation of SAP (Systems, Applications and Products in Data Processing)

- They found themselves operating in a purely reactive mode

- Align with your culture: In this Lean Six Sigma-focused environment, where measurement is paramount, the ADKAR Model's metrics were utilized as the foundational entry point for initiating change management processes.

This company's journey highlights the need for flexible and responsive change management.

4. Home fixtures

A home fixtures manufacturing company’s response to the recession offers valuable insights on effectively managing change. They focused on aligning change management with their disciplined culture, emphasizing operational efficiency:

Industry: Home Fixtures Manufacturing Revenue: $600 million Number of employees: 3,000

Context: Facing the lingering effects of the recession

Necessity: Need to introduce substantial changes for more efficient operations

Challenge: Change management was considered a low priority within the company

- Align with your culture: The company's culture, characterized by discipline in projects and processes, ensured that change management was implemented systematically and disciplined.

This company’s experience during the recession proves that aligning change with company culture is key to overcoming tough times.

5. Web services

A web services software company transformed its culture and workspace. They integrated change management into their IT strategy to overcome resistance and foster innovation:

Industry : Web Services Software Revenue : $3.3 billion Number of employees : 10,000

Initiatives : Cultural transformation; applying an unassigned seating model

Challenges : Resistance in IT project management

- Focus on a key initiative: Applied change management in workspace transformation

- Go where the energy is: Establishing a change management practice within its IT department, developing self-service change management tools, and forming thoughtful partnerships

- I ntegrate with existing competencies: "Leading change" was essential to the organization's newly developed leadership competency model.

This case demonstrates the importance of weaving change management into the fabric of tech companies, especially for cultural shifts.

6. Security systems

A high-tech security company effectively managed a major restructuring. They created a change network that shifted change management from HR to business processes:

Industry : High-Tech (Security Systems) Revenue : $10 billion Number of employees: 57,000

Major changes : Company separation; division into three segments

Challenge : No unified change management approach

- Formed a network of leaders from transformation projects

- Go where the energy is: Shifted change management from HR to business processes

- Integrate with existing competencies: Included principles of change management in the training curriculum for the project management boot camp.

- Treat growing your capability like a change: Executive roadshow launch to gain support for enterprise-wide change management

This company’s innovative approach to restructuring shows h ow reimagining change management can lead to successful outcomes.

7. Clothing store

A major clothing retailer’s journey to unify its brand model. They overcame siloed change management through collaborative efforts and a community-driven approach:

Industry : Retail (Clothing Store) Revenue : $16 billion Number of employees : 141,000

Major change initiative : Strategic unification of the brand operating model

Historical challenge : Traditional management of change in siloes

- Build a change network : This retailer established a community of practice for change management, involving representatives from autonomous units to foster consensus on change initiatives.

The story of this retailer illustrates how collaborative efforts in change management can unify and strengthen a brand in the retail world.

A major Canadian bank initiative to standardize change management across its organization. They established a Center of Excellence and tailored communities of practice for effective change:

Industry : Financial Services (Canadian Bank) Revenue : $38 billion Number of employees : 78,000

Current state : Absence of enterprise-wide change management standards

Challenge :

- Employees, contractors, and consultants using individual methods for change management

- Reliance on personal knowledge and experience to deploy change management strategies

- Build a change network: The bank established a Center of Excellence and created federated communities of practice within each business unit, aiming to localize and tailor change management efforts.

This bank’s journey in standardizing change management offers valuable insights for large organizations looking to streamline their processes.

9. Municipality

You can learn from a Canadian municipality’s significant shift to enhance client satisfaction. They integrated change management across all levels to achieve profound organizational change and improved public service:

Industry : Municipal Government (Canadian Municipality) Revenue : $1.9 billion Number of employees : 3,000

New mandate:

- Implementing a new deliberate vision focusing on each individual’s role in driving client satisfaction

Nature of shift :

- A fundamental change within the public institution

Scope of impact :

- It affected all levels, from leadership to front-line staff

Solution :

- Treat growing your capability like a change: Change leaders promoted awareness and cultivated a desire to adopt change management as a standard enterprise-wide practice.

The municipality's strategy shows us how effective change management can significantly improve public services and organizational efficiency.

6 Tactics for Growing Enterprise Change Management Capability

Prosci's exploration with 10 industry leaders uncovered six primary tactics for enterprise change growth , demonstrating a "universal theme, unique application" approach.

This framework goes beyond standard procedures, focusing on developing a deep understanding and skill in managing change. It offers transformative tactics, guiding organizations towards excelling in adapting to change. Here, we uncover these transformative tactics, guiding organizations toward mastery of change.

1. Align with Your culture

Organizational culture profoundly influences how change management should be deployed.

Recognizing whether your organization leans towards traditional practices or innovative approaches is vital. This understanding isn't just about alignment; it's an opportunity to enhance and sometimes shift your cultural environment.

When effectively combined with an organization's unique culture, change management can greatly enhance key initiatives. This leads to widespread benefits beyond individual projects and promotes overall growth and development within the organization.

Embrace this as a fundamental tool to strengthen and transform your company's cultural fabric.

2. Focus on key initiatives

In the early phase of developing change management capabilities, selecting noticeable projects with executive backing is important.

This helps demonstrate the real-world impact of change management, making it easier for employees and leadership to understand its benefits. This strategy helps build support and maintain the momentum of change management initiatives within your organization.

Focus on capturing and sharing these successes to encourage buy-in further and underscore the importance of change management in achieving organizational goals.

3. Build a change network

Building change capability isn't just about a few advocates but creating a network of change champions across your organization.

This network, essential in spreading the message and benefits of change management, varies in composition but is universally crucial. It could include departmental practitioners, business unit leaders, or a mix of roles working together to enhance awareness, credibility, and a shared purpose.

Our Best Practices in Change Management study shows that 45% of organizations leverage such networks. These groups boost the effectiveness of change management and keep it moving forward.

4. Go where the energy is

To build change capabilities throughout an organization effectively, the focus should be on matching the organization's current readiness rather than just pushing new methods.

Identify and focus on parts of your organization that are ready for change. Align your change initiatives with these sectors. Involve senior leaders and those enthusiastic about change to naturally generate demand for these transformations.

Showcasing successful initiatives encourages a collaborative culture of change, making it an organic part of your organization's growth.

5. Integrate with existing competencies

Change management is a vital skill across various organizational roles.

Integrating it into competency models and job profiles is increasingly common, yet often lacks the necessary training and tools.

When change management skills expand beyond the experts, they become an integral part of the organization's culture—nurturing a solid foundation of effective change leadership.

This approach embeds change management deeper within the company and cultivates leaders who can support and sustain this essential practice.

6. Treat growing your capability like a change

Growing change capability is a transformative journey for your business and your employees. It demands a structured, strategic approach beyond telling your network that change is coming.

Applying the ADKAR Model universally and focusing on your organization's unique needs is pivotal. It's about building awareness, sparking a desire for change across the enterprise, and equipping employees with the knowledge and skills for effective, lasting change.

Treating capability-building like a change ensures that change management becomes a core part of your organization's fabric, benefitting every team member.

These six tactics are powerful tools for enhancing your organization's ability to adapt and remain resilient in a rapidly changing business environment.

Comprehensive Insights From Change Management Examples

These diverse change management examples provide field-tested savvy and offer a window into how varied organizations successfully manage change.

Case studies , from healthcare reform to innovative corporate restructuring, exemplify how aligning with organizational culture, building strong change networks, and focusing on tactical initiatives can significantly impact change management outcomes.

This guide, enriched with real-world applications, enhances understanding and execution of effective change management, setting a benchmark for future transformations.

To learn more about partnering with Prosci for your next change initiative, discover Prosci's Advisory services and enterprise training options and consider practitioner certification .

Founded in 1994, Prosci is a global leader in change management. We enable organizations around the world to achieve change outcomes and grow change capability through change management solutions based on holistic, research-based, easy-to-use tools, methodologies and services.

See all posts from Prosci

You Might Also Like

Enterprise - 8 MINS

3 Essential Change Management Strategies in Healthcare

What Is Change Management in Healthcare?

Subscribe here.

7 real-life organizational change examples & best practices

By Sanni Juoperi 9. November 2021

Does the famous Ray Noorda quote “Cause change and lead; accept change and survive; resist change and die” resonate with you?

The business environment is more turbulent and the technology adoption landscape is more fast-changing than ever . As of late, businesses have had to shift to fully virtual business models, only to start all over again to build models that work optimally in the hybrid environment. Leading change, and beyond that, the ability to proactively transform the business model and strategy, are the key capabilities for any leader today.

In this article, we will share seven real-life tested organizational change examples and best practices that will help you embrace the journey of neverending business transformation.

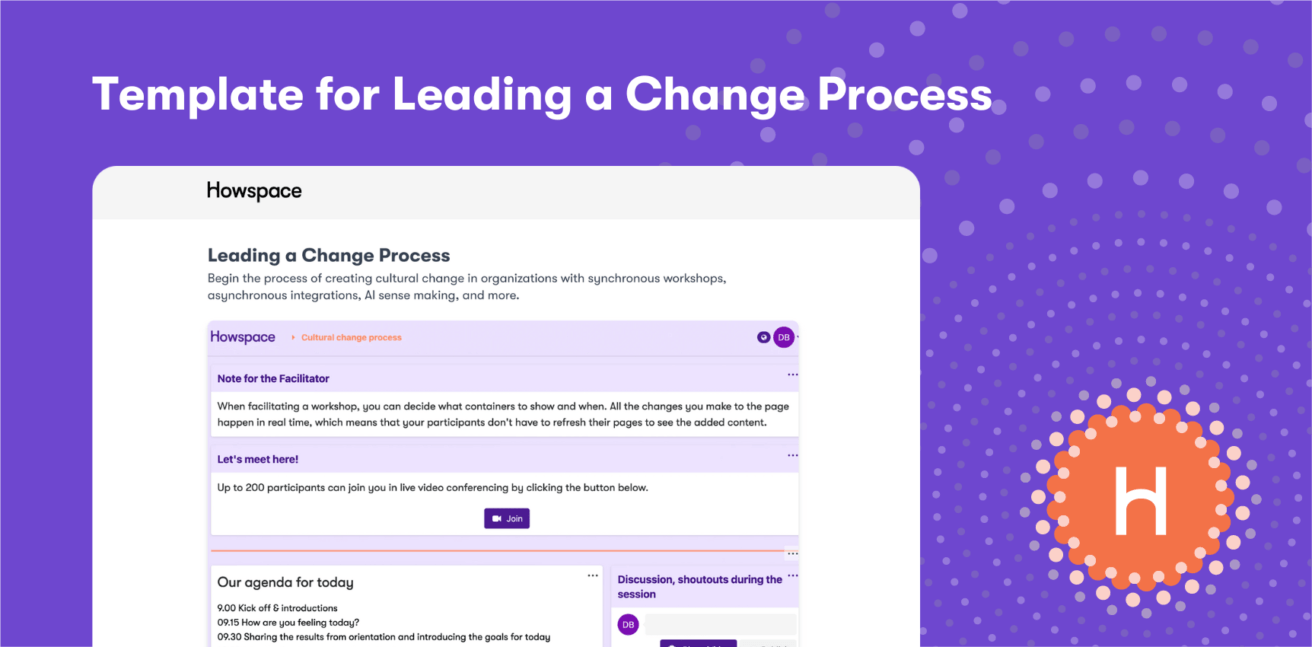

Grab our free template for leading a change process and get started with the cultural change process.

1. Real-life example: Shared values and culture drive the ability to change

The global elevator and escalator manufacturer with 60 000 employees, KONE Corporation , recreated its company values and was fast to establish them as a part of employees’ everyday life. The key to success? A collaborative process where the values came from employees’ real-life experiences and dialogue.

“Howspace really gives every individual the opportunity to influence and be part of the decision-making process.”

Lotta Vuoristo , Head of Culture Journey at KONE, describes the process: “There were a lot of people involved in the discussions whom we have previously struggled to engage without travelling to where they are and working together face-to-face. Now, everyone was really enthusiastic and active.”.

Vuoristo—like many other work-life professionals—believes that from now on, digital working practices are an inherent part of everyday life at KONE as well as in other organizations. The key to success is to get every member of the organization involved in cultural development and strategic transformation.

Virtual working methods contribute to equality when the discussions are not only analyzed by humans but also by artificial intelligence . “I feel that Howspace really gives every individual the opportunity to influence and be part of the decision-making process,” says Vuoristo. Read the full story here .

2. Best practice: Use a structured framework for organizational change

The ADKAR® Model of change is a well-known and widely used tool that helps you analyze your change and better understand it. For someone who’s unfamiliar with building organizational change processes, a structured framework around building human-centred change can be good support for getting started.

The five ADKAR elements—awareness, desire, knowledge, ability, and reinforcement—are the building blocks for creating change from the human perspective. Read this article to get ideas on how to take the ADKAR model from theory to practice.

Image source: prosci.com

3. Real-life example: Build the organizational change by strengthening what already works

Banking is a traditional industry with a lot of hierarchical structures. At the same time, it’s going through major changes with digitalization and shifting customer behaviour.

The Finnish banking company, Aktia, and the culture design agency, Milestone , realized that to embrace external changes, they needed to double down on what already worked well in Aktia’s internal culture.

By listening to Aktia’s employees and line managers on a digital platform, they identified the best parts of their culture: working together for the customer, innovativeness, bravery, and accountability.

“Using digital tools combined with service design methods allowed us to grasp the big picture fast.”

“With the Howspace platform, we got the opportunity to also involve line managers in the organization straight from the beginning. Using digital tools combined with service design methods allowed us to grasp the big picture fast,” describes Elina Aaltolainen, Culture Strategist from Milestone.

By strengthening the positive aspects that already existed in Aktia’s corporate culture, they were able to build Aktia’s future culture vision. Read the full story here.

4. Best practice: Create a safe space for finding all the ‘whys’ for change

There is usually a trigger—internal or external—as to why an organization pursues a change initiative. It’s the first ‘why’: Why do we need organizational change? It’s important to acknowledge, however, that this first why is not enough. People who make up the organization must make sense of the process in their own way and find their own ‘whys.’

Beyond the “why,” you then need to consider how you’ll go about the change process, which should include getting everyone involved and sharing their knowledge and ideas about the ongoing change.

As you facilitate this process, ensure people feel safe to speak their minds honestly. Feelings are always involved when people are involved. One helpful idea is to allow anonymous commenting for particularly sensitive phases of the process.

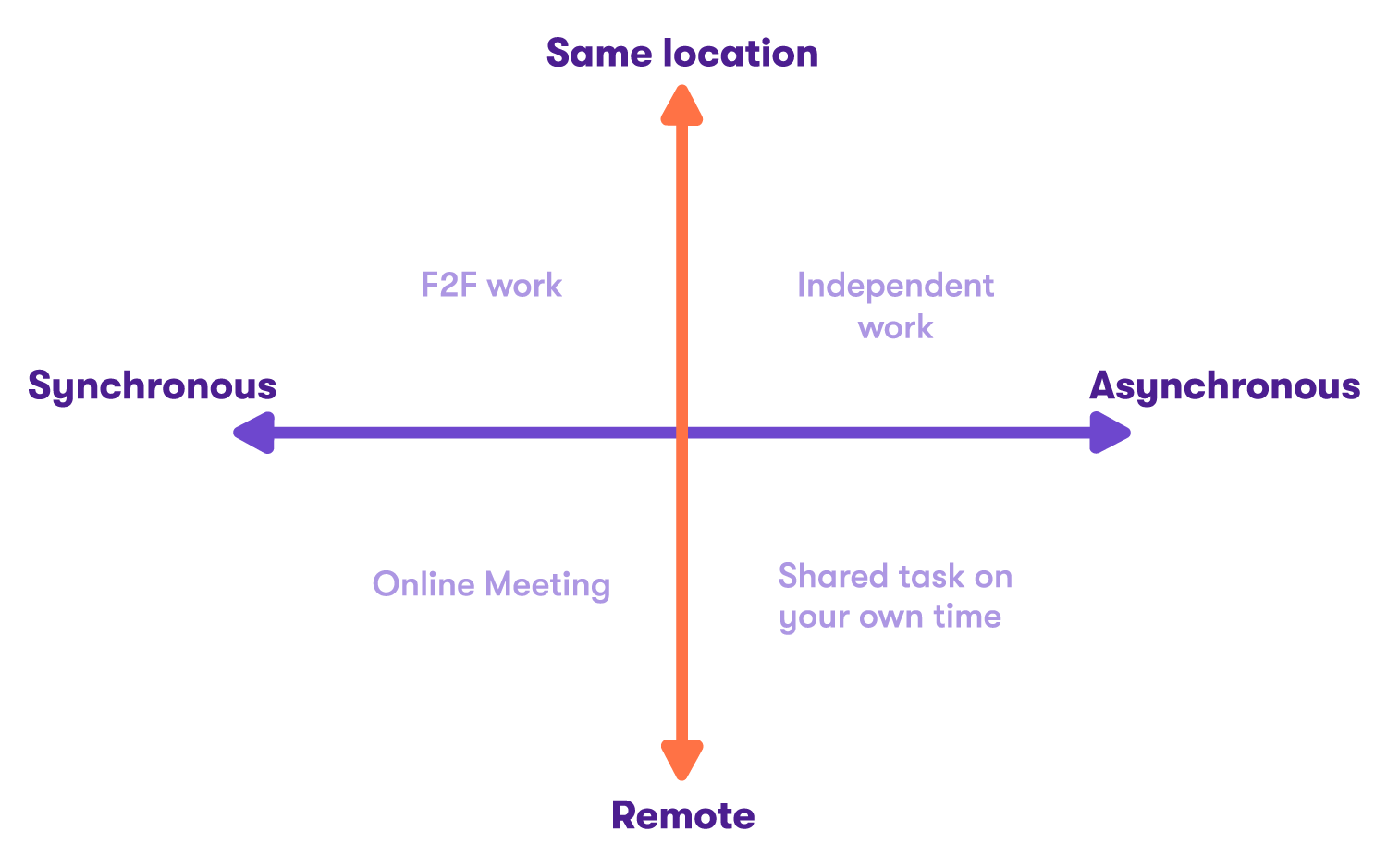

5. Real-life example: Build on asynchronous communication to involve everyone

Wärtsilä Energy, a global leader in sustainable energy solutions, had the ambitious goal of leading the transition towards a 100% renewable energy future. To reach this goal, the company needed a bold and unique organizational growth strategy.

Wärtsilä ’s talent development lead, Kati Järvinen, started working for the company in the middle of its strategy process. The company’s previous growth strategy was done traditionally, with little input from employees. But this time Wärtsilä Energy was ready to integrate every employee’s insights into the process of identifying strategic capabilities.

“We had been used to a quite stable business, but now we are facing a totally new situation in the market. The energy transition is huge, all the market requirements are changing, and our competitors challenge us all the time. That’s why it’s time for us to direct our whole organization to the more agile ways of working,” Järvinen explains.

Working both synchronously and asynchronously, no matter where people were and when they wanted to join the process, everyone was able to contribute to the shared strategy initiatives.

Adapted from the work of John Losey, IntoWisdom Group

“With Howspace, people were able to join the process whenever, wherever. It was wonderful that we had some pre-study before the workshops and during and after the events. People learned on the go, in small pieces, and when they had the motivation. We also had some quizzes and polls that immediately gave us excellent insight on how people experienced our strategy,” says Järvinen. Read the full story here.

6. Real-life example: AI supports making sense of the big picture

People need time and space to do their own sensemaking around change, as mentioned before. And with large communities and organizations, the amount of material to go through quickly becomes an issue.

When the Finnish Medical Association (FMA) started to prepare its basic principles of healthcare, it wanted to involve all members in discussing how to make healthcare even more effective in the future. The FMA has more than 26,000 members. To involve this amount of members for co-creation, going through input manually is not an option.

“We wanted a practical tool that would encourage and inspire doctors to actively discuss healthcare needs. The doctors know best what is going on in their field, and the Howspace digital platform made it possible to involve people in extensive discussions,” says Heikki Pärnänen , Policy Director at the FMA. Read more about their use of AI supporting large-scale dialogue in this article.

7. Best practice: Use a digital platform to co-create change

Many of the themes mentioned in this article require the ability to bring people together to have a dialogue around the change that is happening or needs to happen in an organization.

Howspace is a facilitation platform that is built for this purpose. Its built-in real-time AI capabilities—to build summaries, theme clusters and word clouds out of the discussion—allow for large groups of people to participate in change.

Check out our template for leading a change process! 💡 This practical process template walks you through the whole process of involvement-based cultural change from communicating the need for change to integrating it into the day-to-day.

Already a Howspace-user? You can add the template to your account here .

You might be interested in these as well

Organizational development

The best change management tools for successful organizational transformation

Embracing change within organizations can be challenging, as people naturally resist it. However, utilizing the right change management software can […]

Top 7 Virtual Organizational Transformation Strategies

When it comes to organizational transformation strategies and how to effectively lead change in a virtual environment, my pro tip […]

Human-centric transformation: What is it and why does it matter?

Facilitating human-centric transformation is the skill of the future. But what exactly is human-centric transformation, and why is it so important?

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

Change Management Case Study Examples: Lessons from Industry Giants

Explore some transformative journeys with efficient Change Management Case Study examples. Delve into case studies from Coca-Cola, Heinz, Intuit, and many more. Dive in to unearth the strategic wisdom and pivotal lessons gleaned from the experiences of these titans in the industry. Read to learn about and grasp the Change Management art!

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Certified Professional Change Management CPCM

- Risk Management for Change Training

- Managing Change with Agile Methodology Training

- Complete Change Management Assessments Training

- Managing Organisational Change Effectively

In the fast-paced world of business, staying ahead means being able to adapt. Have you ever wondered how some brands manage to thrive despite huge challenges? This blog dives into a collection of Change Management Case Studies, sharing wisdom from top companies that have faced and conquered adversity through effective Change Management Activities. These aren’t just stories; they’re success strategies.

Each Change Management Case Study reveals the smart choices and creative fixes that helped companies navigate rough waters. How did they turn crises into chances to grow? What can we take away from their successes and mistakes? Keep reading to discover these inspiring stories and learn how they can reshape your approach to change in your own business.

Table of Contents

1) What is Change Management in Business?

2) Top Examples of Case Studies on Change Management

a) Coca-Cola

b) Adobe

c) Heinz

d) Intuit

e) Kodak

f) Barclays Bank

3) Conclusion

What is Change Management in Business?

Change management in business refers to the structured process of planning, implementing, and managing changes within an organisation. It involves anticipating, navigating, and adapting to shifts in strategy, technology, processes, or culture to achieve desired outcomes and sustain competitiveness.

Effective Change Management entails identifying the need for change, engaging stakeholders, communicating effectively, and mitigating resistance to ensure smooth transitions. By embracing Change Management principles and utilizing change management tools , businesses can enhance agility, resilience, and innovation, driving growth and success in dynamic environments.

Top Examples of Case Studies on Change Management

Let's explore some transformative journeys of industry leaders through compelling case studies on Change Management:

1) Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola, the beverage titan, acknowledged the necessity to evolve with consumer tastes, market shifts, and regulatory changes. The rise of health-conscious consumers prompted Coca-Cola to revamp its offerings and business approach. The company’s proactive Change Management centred on innovation and diversification, leading to the launch of healthier options like Coca-Cola Zero Sugar.

Strategic alliances and acquisitions broadened Coca-Cola’s market reach and variety. Notably, Coca-Cola introduced eco-friendly packaging like the PlantBottle and championed sustainability in its marketing, bolstering its brand image.

Acquire the expertise to facilitate smooth changes and propel your success forward – join our Change Management Practitioner Course now!

2) Adobe

Adobe, with its global workforce and significant revenue, faced a shift due to technological advancements and competitive pressures. In 2011, Adobe transitioned from physical software sales to cloud-based services, offering free downloads or subscriptions.

This shift necessitated a transformation in Adobe’s HR practices, moving from traditional roles to a more human-centric approach, aligning with the company’s innovative and millennial-driven culture.

Discover the Impact of Change Management Salaries on Career Growth and Organizational Success!

3) Heinz

Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital’s acquisition of Heinz led to immediate, sweeping changes. The new management implemented cost-cutting measures and altered executive perks.

Additionally, it introduced a more insular leadership style, contrasting with 3G’s young, mobile, and bonus-driven executive team.

Commence on a journey of transformative leadership and achieve measurable outcomes by joining our Change Management Foundation Course today!

4) Intuit

Steve Bennett’s leadership at Intuit marked a significant shift. Adopting the McKinsey 7S Model, he restructured the organisation to enhance decision-making, align rewards with strategy, and foster a performance-driven culture. His changes resulted in a notable increase in operating profits.

Discover the Best Change Management Books ! Read our top picks and transform your organization today!

5) Kodak

Kodak, the pioneer of the first digital and megapixel cameras in 1975 and 1986, faced bankruptcy in 2012. Initially, digital technology was costly and had subpar image quality, leading Kodak to predict a decade before it threatened their traditional business. Despite this accurate forecast, Kodak focused on enhancing film quality rather than digital innovation.

Dominating the market in 1976 and peaking with £12,52,16 billion in sales in 1999, Kodak’s reluctance to adopt new technology led to a decline, with revenues falling to £4,85,11,90 billion in 2011.

Get ready for your interview with our top Change Management Interview Questions .

In contrast, Fuji, Kodak’s competitor, embraced digital transformation and diversified into new ventures.

Empower your team to manage change effectively through our Managing Change With Agile Methodology Training – sign up now!

6) Barclays Bank

The financial sector, particularly hit by the 2008 mortgage crisis, saw Barclays Capital aiming for global leadership under Bob Diamond. However, the London Inter-bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) scandal led to fines and resignations, prompting a strategic overhaul by new CEO Antony Jenkins in 2012.

Changes included rebranding, refocusing on core markets, altering the business model away from high-risk lending, fostering a customer-centric culture, downsizing, and embracing technology for efficiency. These reforms aimed to strengthen Barclays, improve shareholder returns, and restore trust.

Dive into the detailed Case Study on Change Management

Conclusion

The discussed Change Management Case Study examples serve as a testament to the transformative power of adept Change Management. Let these insights from industry leaders motivate and direct you as you navigate your organisation towards a path of continuous innovation and enduring prosperity.

Enhance your team’s ability to manage uncertainty and achieve impactful results – sign up for our comprehensive Risk Management For Change Training now!

Frequently Asked Questions

The five key elements of Change Management typically include communication, leadership, stakeholder engagement, training and development, and measurement and evaluation. These elements form the foundation for successfully navigating organisational change and ensuring its effectiveness.

The seven steps of Change Management involve identifying the need for change, developing a Change Management plan, communicating the change vision, empowering employees, implementing change initiatives, celebrating milestones, and sustaining change through ongoing evaluation and adaptation.

The Knowledge Academy takes global learning to new heights, offering over 30,000 online courses across 490+ locations in 220 countries. This expansive reach ensures accessibility and convenience for learners worldwide.

Alongside our diverse Online Course Catalogue, encompassing 17 major categories, we go the extra mile by providing a plethora of free educational Online Resources like News updates, Blogs , videos, webinars, and interview questions. Tailoring learning experiences further, professionals can maximise value with customisable Course Bundles of TKA .

The Knowledge Academy’s Knowledge Pass , a prepaid voucher, adds another layer of flexibility, allowing course bookings over a 12-month period. Join us on a journey where education knows no bounds.

The Knowledge Academy offers various Change Management Courses , including the Change Management Practitioner Course, Change Management Foundation Training, and Risk Management for Change Training. These courses cater to different skill levels, providing comprehensive insights into Change Management Metrics .

Our Project Management Blogs cover a range of topics related to Change Management, offering valuable resources, best practices, and industry insights. Whether you are a beginner or looking to advance your Project Management skills, The Knowledge Academy's diverse courses and informative blogs have got you covered.

Upcoming Project Management Resources Batches & Dates

Mon 9th Sep 2024

Sat 14th Sep 2024, Sun 15th Sep 2024

Mon 23rd Sep 2024

Mon 7th Oct 2024

Sat 12th Oct 2024, Sun 13th Oct 2024

Mon 21st Oct 2024

Mon 28th Oct 2024

Mon 4th Nov 2024

Sat 9th Nov 2024, Sun 10th Nov 2024

Mon 11th Nov 2024

Mon 18th Nov 2024

Mon 25th Nov 2024

Mon 2nd Dec 2024

Sat 7th Dec 2024, Sun 8th Dec 2024

Mon 9th Dec 2024

Mon 16th Dec 2024

Mon 6th Jan 2025

Mon 13th Jan 2025

Mon 20th Jan 2025

Mon 27th Jan 2025

Mon 3rd Feb 2025

Mon 10th Feb 2025

Mon 17th Feb 2025

Mon 24th Feb 2025

Mon 3rd Mar 2025

Mon 10th Mar 2025

Mon 17th Mar 2025

Mon 24th Mar 2025

Mon 31st Mar 2025

Mon 7th Apr 2025

Mon 28th Apr 2025

Mon 12th May 2025

Mon 19th May 2025

Mon 9th Jun 2025

Mon 23rd Jun 2025

Mon 7th Jul 2025

Mon 21st Jul 2025

Mon 4th Aug 2025

Mon 18th Aug 2025

Mon 1st Sep 2025

Mon 15th Sep 2025

Mon 29th Sep 2025

Mon 13th Oct 2025

Mon 20th Oct 2025

Mon 27th Oct 2025

Mon 3rd Nov 2025

Mon 10th Nov 2025

Mon 17th Nov 2025

Mon 24th Nov 2025

Mon 1st Dec 2025

Mon 8th Dec 2025

Mon 15th Dec 2025

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest summer sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- ISO 9001 Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

Transformational change: Theory and practice

A look at how transformational change themes apply in practice, with case studies providing practical examples

Explores how the themes on transformational change apply in practice

Our report, Landing transformational change: Closing the gap between theory and practice explores how the themes identified in earlier research apply in practice. Case studies from four organisations provide practical examples of how organisations have approached transformational change.

The report also includes recommendations that HR, OD and L&D professionals should consider for their organisations and their own skill set, if they are to be successful expert initiators and facilitators of transformational change.

Whilst these findings and case studies are UK-based, the broader trends and implications should be of interest wherever you are based.

Download the report and individual case studies below

Landing transformational change

This earlier report covers some of the thinking and innovative ideas in the field of change management that can help to land transformational change. Drawing on a comprehensive literature review on change management the report develops ten themes on transformational change practice to provide a platform of knowledge on designing, managing and embedding change essential for OD, L&D and HR professionals.

Tackling barriers to work today whilst creating inclusive workplaces of tomorrow.

Bullying and harassment

Discover our practice guidance and recommendations to tackle bullying and harassment in the workplace.

We look at how investing in digital technologies, HR skills and culture drive success in restructured people functions

A case study of an HR function shifting from an Ulrich+ model towards an employee experience-driven model

A case study of a people function shifting to a four-pillar model to deliver a more consistent employee experience throughout the organisation

We look at the main focus areas and share practical examples from organisations who are optimising their HR operating model

More reports

Read our latest Labour Market Outlook report for analysis on employers’ recruitment, redundancy and pay intentions

A Northern Ireland summary of the CIPD Good Work Index 2024 survey report

A Wales summary of the CIPD Good Work Index 2024 survey report

A North of England summary of the CIPD Good Work Index 2024 survey report

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Most Successful Approaches to Leading Organizational Change

- Deborah Rowland,

- Michael Thorley,

- Nicole Brauckmann

A closer look at four distinct ways to drive transformation.

When tasked with implementing large-scale organizational change, leaders often give too much attention to the what of change — such as a new organization strategy, operating model or acquisition integration — not the how — the particular way they will approach such changes. Such inattention to the how comes with the major risk that old routines will be used to get to new places. Any unquestioned, “default” approach to change may lead to a lot of busy action, but not genuine system transformation. Through their practice and research, the authors have identified the optimal ways to conceive, design, and implement successful organizational change.

Management of long-term, complex, large-scale change has a reputation of not delivering the anticipated benefits. A primary reason for this is that leaders generally fail to consider how to approach change in a way that matches their intent.

- Deborah Rowland is the co-author of Sustaining Change: Leadership That Works , Still Moving: How to Lead Mindful Change , and the Still Moving Field Guide: Change Vitality at Your Fingertips . She has personally led change at Shell, Gucci Group, BBC Worldwide, and PepsiCo and pioneered original research in the field, accepted as a paper at the 2016 Academy of Management and the 2019 European Academy of Management. Thinkers50 Radar named as one of the generation of management thinkers changing the world of business in 2017, and she’s on the 2021 HR Most Influential Thinker list. She is Cambridge University 1st Class Archaeology & Anthropology Graduate.

- Michael Thorley is a qualified accountant, psychotherapist, executive psychological coach, and coach supervisor integrating all modalities to create a unique approach. Combining his extensive experience of running P&L accounts and developing approaches that combine “hard”-edged and “softer”-edged management approaches, he works as a non-executive director and advisor to many different organizations across the world that wish to generate a new perspective on change.

- Nicole Brauckmann focuses on helping organizations and individuals create the conditions for successful emergent change to unfold. As an executive and consultant, she has worked to deliver large-scale complex change across different industries, including energy, engineering, financial services, media, and not-for profit. She holds a PhD at Faculty of Philosophy, Westfaelische Wilhelms University Muenster and spent several years on academic research and teaching at University of San Diego Business School.

Partner Center

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 November 2019

Organisational change in hospitals: a qualitative case-study of staff perspectives

- Chiara Pomare ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9118-7207 1 ,

- Kate Churruca 1 ,

- Janet C. Long 1 ,

- Louise A. Ellis 1 &

- Jeffrey Braithwaite 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 19 , Article number: 840 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

22 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Organisational change in health systems is common. Success is often tied to the actors involved, including their awareness of the change, personal engagement and ownership of it. In many health systems, one of the most common changes we are witnessing is the redevelopment of long-standing hospitals. However, we know little about how hospital staff understand and experience such potentially far-reaching organisational change. The purpose of this study is to explore the understanding and experiences of hospital staff in the early stages of organisational change, using a hospital redevelopment in Sydney, Australia as a case study.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 46 clinical and non-clinical staff working at a large metropolitan hospital. Hospital staff were moving into a new building, not moving, or had moved into a different building two years prior. Questions asked staff about their level of awareness of the upcoming redevelopment and their experiences in the early stage of this change. Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Some staff expressed apprehension and held negative expectations regarding the organisational change. Concerns included inadequate staffing and potential for collaboration breakdown due to new layout of workspaces. These fears were compounded by current experiences of feeling uninformed about the change, as well as feelings of being fatigued and under-staffed in the constantly changing hospital environment. Nevertheless, balancing this, many staff reported positive expectations regarding the benefits to patients of the change and the potential for staff to adapt in the face of this change.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that it is important to understand prospectively how actors involved make sense of organisational change, in order to potentially assuage concerns and alleviate negative expectations. Throughout the processes of organisational change, such as a hospital redevelopment, staff need to be engaged, adequately informed, trained, and to feel supported by management. The use of champions of varying professions and lead departments, may be useful to address concerns, adequately inform, and promote a sense of engagement among staff.

Peer Review reports

Change is a common experience in complex health care systems. Staff, patients and visitors come and go [ 1 ]; leadership, models of care, workforce and governing structures are reshaped in response to policy and legislative change [ 2 ], and new technologies and equipment are introduced or retired [ 3 ]. In addition to these common changes experienced throughout health care, the acute sector in many countries is constantly undergoing major changes to the physical hospital infrastructure [ 4 , 5 ]. In New South Wales, Australia, several reports have described the increase in hospital redevelopment projects as a ‘hospital building boom’ [ 4 , 6 ], with approximately 100 major health capital projects (i.e., projects over AUD$10 million) currently in train [ 7 ]. In addition to meeting the needs of a growing and ageing population [ 8 ], the re-design and refurbishment of older hospital infrastructure is supported by a range of arguments and anecdotal evidence highlighting the positive relationship between the hospital physical environment and patient [ 9 ] and staff outcomes [ 10 ]. While there are many reasons why hospital redevelopments are taking place, we know little about how hospital staff prospectively perceive change, and their experiences, expectations, and concerns. Hospital staff encapsulates any employee working in the hospital context. This includes clinical and non-clinical staff who provide care, support, cleaning, catering, managerial and administrative duties to patients and the broader community.

One reason as to why little research has explored the perspectives of hospital staff during a redevelopment may be because hospital redevelopment is often considered a physical, rather than organisational change. Organisational change means that not only the physical environment is altered, but also the behavioural operations, structural relationships and roles, and the hospital organisational culture may transform. For example, changing the physical health care environment can affect job satisfaction, stress, intention to leave [ 11 ], and the way staff work together [ 12 ].

Redeveloping a hospital can be both an exciting and challenging time for staff. In a recent notable example of opening a new hospital building in Australia, staff attitudes shifted from appreciation and excitement in the early stages of change to frustration and angst as the development progressed [ 13 ]. Similar experiences have been reported elsewhere, such as in a study describing the consequences for staff of hospital change in South Africa [ 14 ]. However, these examples explored staff attitudes towards change retrospectively and considered the change as a physical redevelopment, rather than organisational change. Such retrospective reports may be limited in validity [ 15 ] as prospective experiences and understanding of change reported by staff may be conflated with the final outcome of the change. The hospital redevelopment literature has also prospectively assessed health impacts of proposed redevelopment plans as a means to predetermine the impact of a large change on the population [ 16 ]; while prospective, this research again considers redevelopment as a physical modification, rather than an organisational change. Thus, while the literature has reported retrospective accounts of staff experiences in large hospital change and prospective assessment of the impact of the change, there is little research examining the understanding and experiences of staff in the early stages of redevelopmental change in hospitals through a lens of organisational change.

Seminal research in the organisational change literature highlights that the role of frontline workers (in this case hospital staff) is crucial to implementation of any process or change [ 17 , 18 ]. Specifically, that the support of actors (understanding, owning, and engaging) can determine the success of a change [ 19 ]. This is consistent with complexity science accounts which suggest that any improvement and transformation of health systems is dependent upon the actors involved, and the extent and quality of their interactions, their emergent behaviours, and localised responses [ 1 , 20 ]. In health care, change can be resisted when it is imposed on actors (in this case, hospital staff), but may be better accepted when people are involved and adopt a sense of ownership of the changes that will affect them [ 21 ]. This may include being involved in the design process. For this reason, it is important to examine the understanding and experiences of actors involved in a change (i.e., hospital staff in a redevelopment), in order to understand and potentially address their concerns, alleviating negative expectations prior to the change.

This study is part of a larger project exploring how hospital redevelopment influences the organisation, staff and patients involved [ 22 ]. The present study aimed to explore the understanding and experiences of staff prior to moving into a new building as one stage in a multidimensional organisational change project. The research questions were: How do staff make sense of this organisational change? How well informed do they feel? What are their expectations and concerns? What are the implications for hospitals undergoing organisational change, particularly redevelopment?

The study protocol has been published elsewhere [ 22 ]. The Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines were used to ensure comprehensive reporting of the qualitative study results (Additional file 1 ) [ 23 ] .

Study setting and participants

This study was conducted at a large metropolitan, publicly-funded hospital in Sydney, Australia. The facility is undergoing a multimillion-dollar development project to meet the growing needs of the community. This hospital has undergone a number of other changes over the last two decades, including incremental increases in size. Since its opening in the mid 1990s (with approximately 150 beds), several buildings have been added over the years. The hospital now has multiple buildings and over 500 beds.

During the time of this study, the hospital was in the second stage of the multi-stage redevelopment. This stage included: the opening of a new acute services building, the relocation of several wards to this new building (e.g., Intensive care unit (ICU) and Maternity), increases in resources (e.g., equipment, staffing), and the adoption of new ways of working (e.g., activity-based workspaces for support staff). Essentially, the redevelopment involves the opening of a new state-of-the-art building which will include moving services (and staff) from the old to the new building, with some wards staying in the old building. For the wards moving into the new building, this change does not initially involve more patients in existing services, but is intended to increase the number of staff because there will be more physical space to cover and new models of care introduced (e.g., ICU changing to single-bed rooms, more staff needed to individually attend to patients). The current redevelopment includes space for future expansion to account for the growing population. In addition to the redevelopment of the physical infrastructure, the way staff work together is also planned to change. Hospital leadership is aiming to foster a cultural shift towards greater cohesion and unity; highlighting that the hospital redevelopment can be conceptualised as an organisational change of considerable importance and magnitude.

Participants were hospital staff (clinical and non-clinical) working at the hospital under investigation. Staff working on four wards were targeted for interviews, with the intention to capture diverse experiences of the redevelopment and the broader organisational change; two of these wards would be moving into the new building (ICU and Maternity), one ward was not moving (Surgical), and one ward had moved into a new building two years prior (Respiratory). Interviews were also conducted with staff who held responsibilities across wards (e.g., General Services Department: cleaners, porters). The hospital staff were purposively recruited by department heads and snowballed from participants. Fifty staff members were approached (until data saturation was met) with four refusing to participate because they did not have the time.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in private settings at the participants’ place of work (e.g., ward interview rooms, private offices). In the event a participant was unable to meet the researcher in person, interviews were conducted over the phone. A semi-structured interview guide was created in collaboration with key stakeholders from the hospital under investigation and following a literature review. The guide (Additional file 2 ) included questions aimed at exploring participants’: (1) understanding of the hospital’s culture and current ways of working; (2) understanding of the redevelopment and other hospital changes; and (3) concerns or expectations about the organisational change. The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim by the first author who is trained and experienced in conducting semi-structured interviews. No field notes were made during the interview nor were transcripts returned to participants for comment or correction due to the time poor characteristics of the study participants (hospital staff). Participants were informed that the research was part of the first author’s doctoral studies.

Interview data were analysed via thematic analysis [ 24 ] using NVivo [ 25 ]. This approach followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six phases of thematic analysis: familiarise, generate initial codes, develop themes, review potential themes, define and name themes, produce the report. Data were initially read multiple times by the first author, then descriptively and iteratively coded according to semantic features. The analysis included the use of inductive coding to identify patterns driven by the data, together with deductive coding, keeping the research questions in mind. Through examination of codes and coded data, themes were developed. The broader research team (KC, LAE, JCL) were included throughout each stage of the analysis process, with frequent discussions concerning the categorization of codes and themes. This process of having one researcher responsible for the analysis while other researchers then checked and clarified emerging themes throughout contributes to the trustworthiness of the findings [ 26 ].

In presenting the results, extracts have been edited minimally to enhance readability, without altering meaning or inference. Where extracts are presented, staff are coded according to their department (G: General – works across several wards; ICU: Intensive care unit; MAT: Maternity ward; RES: Respiratory ward; SUR: Surgical ward) and profession (AD: Administrative staff; CHGTEAM: Change management team staff; DR: Medical staff; GS: General services staff; MW: Midwifery staff; N: Nursing staff; OTH: Other profession).

Forty-six staff members participated in the semi-structured interviews. Interviews were typically conducted face-to-face ( n = 41; 89.1%), with five interviews conducted over the phone. No differences were discerned in content between these different mediums. Hospital staff taking part in interviews included those from: nursing and midwifery, medical, general services, administrative, and change management (Table 1 ). Change management staff are external to the hospital staff, and do not report to hospital executives. Interviews ranged from seven to 33 min in length ( M = 17 min). Participating staff had worked at the hospital for on average 10.5 years (range 5 months and 30 years).

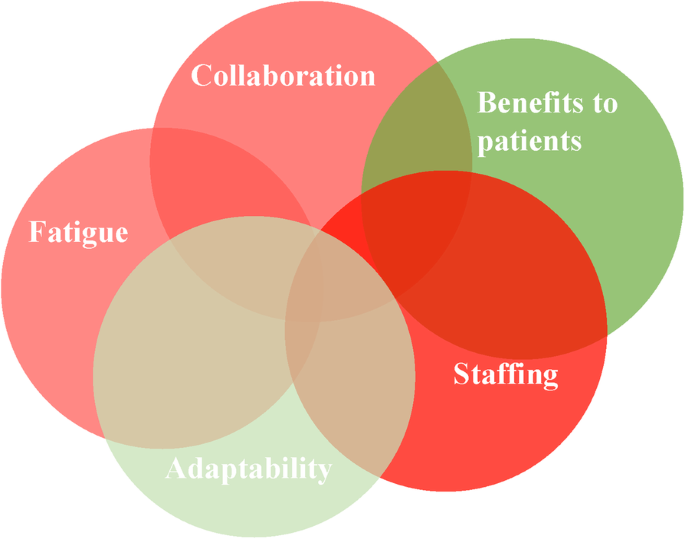

Five themes were identified related to hospital staff’s understanding and experiences (i.e., expectations and concerns) of the change: staffing; benefits to patients; collaboration; fatigue; and adaptability. These expectations and concerns are schematically presented in Fig. 1 , with shades of red indicating negative expectations and concerns associated with the theme, and green representing positive expectations. Intensity of the colour demonstrated the frequency of positivity or negativity associated with that theme (i.e., deeper shades of red indicate frequency of negative discussion of this theme by different hospital staff). This figure also highlights the complexity and interrelatedness of these themes (e.g., the concern of inadequate staffing for the new building was linked with concerns about patient care, which could possibly impede the way the team work together, leading to staff feeling overworked and worn out; these expectations were all mitigated by the staff member’s understanding and awareness of the change). Explanations and examples are presented below.

Thematic visualisation of staff understanding and expectations of the change

Hospital staff consistently held staffing to be a major concern in this redevelopment. To them, the opening of the new building, and with it the increase in physical size and addition of new services, meant that an increase in staff was crucial to successfully implement the change: “ My biggest uncertainty at the moment is the fact that I’m really concerned about whether I’m actually going to get enough staff ” (GS1). Many participants suggested that this issue would determine the success of the new hospital building. This was particularly important for staff moving into the new building with a bigger work space: “ We just need more staff. Yeah I think that’s the main issue - if we fix that then I believe everything should be smooth ” (ICUN4). For the most part, staff were unaware about how many new staff they would have in the new building. This uncertainty involved two related issues: (1) will we get the budget for new staff that we need? And if so, (2) where will we find all these new staff to employ?

On the first point, staff reported concerns that they would not have enough staff to cover the increased physical space and new ways of working within the new building. This lingering uncertainty was the result of external factors, specifically unresolved budget issues: “ But I suppose some of the issues stem from the fact that you never know how many beds we are able to open based on the funding from the government, and that is what is still up in the air ” (ICUDR1).

Regarding the second point, staff noted that even if budgetary issues were resolved, and there was enough money to hire new staff to fill the new building, a challenge would be finding the staff to recruit: “ I don’t know where these new staff are going to come from” (GN3). Some participants suggested that they already encountered difficulties with employing enough appropriately qualified staff and reported concerns that this issue would be compounded when they moved into the new building: “ Excitement will be way gone. It’s more to deal with that stress and the workload of other staff ” (ICUN4). Participants working on wards that were not moving into the new building also reported concerns about staffing. They noted that, despite not being directly involved in previous stages of the redevelopment, they had still been affected by these changes, because their colleagues were taken from their ward without consultation and moved into a new area. Hence, even staff not moving in the next stage of the redevelopment had concerns that their staffing levels would be affected: “ We have been told that we are not moving in there. And hopefully they don’t take our staff there ” (SURN5).

Benefits to patients

Many hospital staff expressed a positive expectation of the move related to benefits for patients. This was consistent across wards, departments and professions. Staff expected patients to experience benefits including reductions in infection rates and improved satisfaction, due to staying in a well-controlled and physically appealing environment with natural light: “ Any new place will give some joy or some happiness to people… The major change will be that because there are individual rooms, the infection rate will be lower and that I’m very pleased with” (ICUDR1).

Despite these participants reporting the improved physical environment was expected to positively affect patients, they also raised concerns that being in the new building might negatively affect patient safety because the increased physical space could introduce more room for error with the greater workload: “ Brings with it the fear, of how will we treat so many patients with nursing when you have one to one and the rooms are closed. That is a constant worry ” (ICUDR1). Participants indicated that this issue would be compounded if staffing levels were not increased.

Collaboration

Staff expressed multiple negative expectations or concerns about how their ways of working together would be affected by moving into the new building. Staff understood the change as more than just a physical expansion, but as an organisational change that would affect their ways of working. This understanding led to concern regarding how to work together in the new building. Specifically, staff moving into the new building were worried about the new layout of ICU, where nurses would be working alone in rooms with single patients. This would disrupt their ability to easily ask for support currently done by asking the nurse at an adjacent bed, or signalling to someone visible across the room: “ Single rooms are great for patients and everything but I think it becomes a bit more isolated for staffing ” (ICUOTH1). These concerns were also recognised among staff working in the change management team, who may not be directly affected by the change, but acknowledged that this is a major consequence of the move into the new building: “ All the beds, they were able to see each other all the time whereas now it’s a different work environment. They’re a bit more isolated… So that’s what we find is the challenge” (CHGTEAM2). Further, staff were concerned about working in open plan spaces that limit opportunity for private discussions, for example with other staff about workplace conflict or personal matters: “ I’m very concerned about insufficient space for private stuff ” (ICUAD1).

Staff reported negative expectations of collaboration breakdown not only within wards, but across the hospital. The organisational change will include far-flung staff and expanded infrastructure, which may decrease opportunity to collaborate directly. For several participants, the growing size of the hospital was seen as a fracturing of the positive, cohesive culture of what was once a smaller hospital—“ It used to be that the general manager would walk through and know everybody by name, the cleaner, maintenance crew, everybody knew everybody’s name ” (GN1)—into more disconnected, subunits: “ Now we’re very separate ” (ICUOTH1).

During interviews, many participants reported feeling over-worked and under-resourced. While some described being fatigued and unhappy at work, the redevelopment was, nevertheless, clearly a positive: “ We’re not happy because we’re under so much pressure and stress. But, you know, we are looking forward to the new build, it’ll be a beautiful building” (GN3). For others, there were concerns that their feelings of being over-worked would not subside with the opening of the new hospital building and that there was a lack of time to even consider the change. This was expressed by staff moving in to the new building, as well as those not moving:

Who has got the time to go and look at those decorative things ! (SURN5).

I can’t see how it will make a big difference to me… I don’t pay a lot of attention to the looks (MATDR1).

It doesn’t really matter… I could be providing it [patient care] in a tent or a building . (MATMW2).

Further, hospital staff expressed frustration in having to endure poor resourcing, which tempered their excitement for the new building: “We’ve all put up with whatever since whenever and I’m done, I’m so done” (ICUAD1). Some participants reported negative expectations related to the increase in physical space in the new building, as adding to the work load of clinical staff and requiring they travel further to get supplies and attend to patients: “They are worried about, hang on I’m going to have to do so many more laps” (ICUAD1). Similarly, an issue expressed on behalf of staff in the General Services Department was whether they will be able to adequately clean and cater for physically larger areas: “ I’m sitting here and looking at [a previous building that was opened] and seeing how filthy it is ” (CHGTEAM3). Concerns about being over-worked in the face of the redevelopment were further emphasised by some interviewees who discussed a problem with turnover: “ We’ve actually had a few people, I have had three people, which is unusual for us, who have looked for other jobs and are probably resigning. You know which is sort of the opposite of what we’d expect at this time, we’d expect they’d be excited for the new building ” (ICUN5). However, most staff in more junior positions had not seen the new building and thus were unaware of the layout and the degree to which it may impact their work: “ Because I have not seen the actual structure of the area, and I don’t know what they based it on and how they figured out a way to be friendly for both staff and patients at the same time ” (ICUN3). The unawareness and lack of understanding accentuated concerns and negative expectations among staff as they expected the worst.

Also contributing to reports of experiencing fatigue, staff described numerous other large changes taking place at the hospital over the years, in addition to the redevelopment: “ Basically for seven years we’ve been undergoing changes since I’ve been here. It is utterly exhausting having this many changes all the time ” (GS1). This highlights that while this study captures prospective insights to the change, change is constant in health care. While the move into the new building has not yet occurred, the move is part of a broader organisational change grander than the physical expansion of infrastructure. While this was a major concern for many staff, some of the senior medical staff dismissed this as being an issue, suggesting constant change is part of health care and should not lead to staff feeling worn out: “ I think once you get to my level you get good at kind of jumping through hoops… As you get more experienced, you just go with the flow a bit more” (SURDR2).

Adaptability

An additional theme involved staff’s positive expectation that they would be able to adapt to the changes brought about by the move into the new building. Reflecting on past experiences of organisational and infrastructure changes at the hospital, staff expressed that it could take time to adapt and see the benefits of the change: “ At the beginning, of course, everybody was scared of the changes and stuff like that, but eventually we got used to it. ” (SURN3). However, some staff reported that they saw adapting to the new building as a concern, potentially because of a lack of knowledge pertaining to what the new building entails: “ I just don’t know. I’m worried because I don’t know what we’re walking in to ” (ICUN2). In general, staff expressed an understanding of the change as one of physical growth (hospital redevelopment) and changes in ways of working (organisational change): “Getting bigger. So, basically taking all of our acute services and putting it in a brand spanking new building where they’re significantly expanding” (GN1); “ The biggest change is changing the way they work. Changing the way they deliver care .” (CHGTEAM2). When asked why the change was happening, hospital staff were consistent in attributing the need for redevelopment to population growth: “ To develop more resources to accommodate for the growing number of patients ” (SURDR3).

Feeling uninformed and uncertain about the change was expressed by staff of different professions and different levels throughout the hospital. In fact, even wards that were not moving to the new building were unsure if this was the case: “ There’s been no communication from anyone really. I hear from different people yes we are moving and then somebody says no we’re not. We’re staying here in the old building. So, I’m not sure exactly who’s going” (SURN1).

Our findings suggest that in the early stages of hospital redevelopment, staff experience both positive and negative expectations that are dependent upon the level of personal understanding, awareness of the change to come, and how well-resourced they already feel. Interviews with hospital staff highlighted a general understanding of the change as involving physical expansion of the hospital. However, participants also reported feeling inadequately informed about what is to come and described a range of sometimes differing expectations about the organisational effects of this change (e.g., on collaboration, for patients). This supports the conceptualisation of hospital redevelopment as not only a physical change, but an organisational one too.

The present study is the first to empirically explore the experiences and understanding of staff in the early stages of a hospital redevelopment, and conceptualised this as an organisational change. This conceptualisation is an important contribution to the organisational change literature because we show that change, even when based on the best evidence-based design, can be disappointing and bring about negative experiences for staff. The concerns and negative expectations of the change expressed by staff in the present study echo past research that retrospectively explored the experiences of staff during a hospital change, in Australia [ 13 ], and elsewhere [e.g., 14]. In the present study, staffing was a major concern reported by hospital staff. This is consistent with other reports of hospital redevelopment in the Australian context. For example, in a report into the opening of a new children’s hospital, staff were frustrated about the progression of the change and that a lack of staffing impacted on service planning. Staffing was also emphasised as an issue in another Australian hospital redevelopment project, where the building opened with insufficient staffing and resources [ 27 ]. Additionally, hospital staff in the present study indicated that they felt fatigued, so much so that excitement for the opening of the new building was diminishing. Reports of low staff morale in hospital redevelopment projects has also been documented in other Australian and international studies [ 13 , 14 ]. Further, participants in this study reported a lack of awareness of the redevelopment, something that appears to be common with a report of hospital revitalisation in the United States reporting a similar finding [ 28 ].