Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

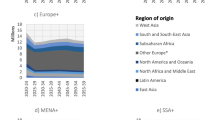

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

What is the purpose of literature review , a. habitat loss and species extinction: , b. range shifts and phenological changes: , c. ocean acidification and coral reefs: , d. adaptive strategies and conservation efforts: .

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review .

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as yo u go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free!

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research | Cite feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface. It also allows you auto-cite references in 10,000+ styles and save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research | Cite” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references in 10,000+ styles into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

| Annotated Bibliography | Literature Review | |

| Purpose | List of citations of books, articles, and other sources with a brief description (annotation) of each source. | Comprehensive and critical analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. |

| Focus | Summary and evaluation of each source, including its relevance, methodology, and key findings. | Provides an overview of the current state of knowledge on a particular subject and identifies gaps, trends, and patterns in existing literature. |

| Structure | Each citation is followed by a concise paragraph (annotation) that describes the source’s content, methodology, and its contribution to the topic. | The literature review is organized thematically or chronologically and involves a synthesis of the findings from different sources to build a narrative or argument. |

| Length | Typically 100-200 words | Length of literature review ranges from a few pages to several chapters |

| Independence | Each source is treated separately, with less emphasis on synthesizing the information across sources. | The writer synthesizes information from multiple sources to present a cohesive overview of the topic. |

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 22+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide).

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Librarian Assistance

For help, please contact the librarian for your subject area. We have a guide to library specialists by subject .

- Last Updated: Aug 26, 2024 5:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

3 Literature Review

Charitianne Williams

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Understand the purpose and function of a literature review.

- Structure a literature review according to basic genre expectations.

- Synthesize ideas from multiple sources using a synthesis matrix.

- Choose between narrative or parenthetical citation and direct quoting, or paraphrase with intent and purpose.

I. Introduction

The purpose of a literature review is just that—it reviews. This means that literature reviews examine a text after it was produced, with all the benefits that hindsight allows a reader. In popular culture, we commonly review movies, restaurants, vacation spots, products, etc. In those reviews, you look back at the single thing you are reviewing and your experience with it. You focus on the strengths and weaknesses of your experience and judge the experience as positive or negative while recommending or not recommending the place or product and explaining why.

An academic literature review does something different, although some of the skills and strategies you use remain the same. The job of a literature review is to examine a collection of research or scholarship (not a single thing or text) on a given topic and show how that scholarship fits together. Literature reviews summarize, describe, evaluate, and synthesize the work of other authors and researchers while looking for common trends/patterns, themes, inconsistencies, and gaps in this previous research. The main strategy writers of a literature review use is synthesis.

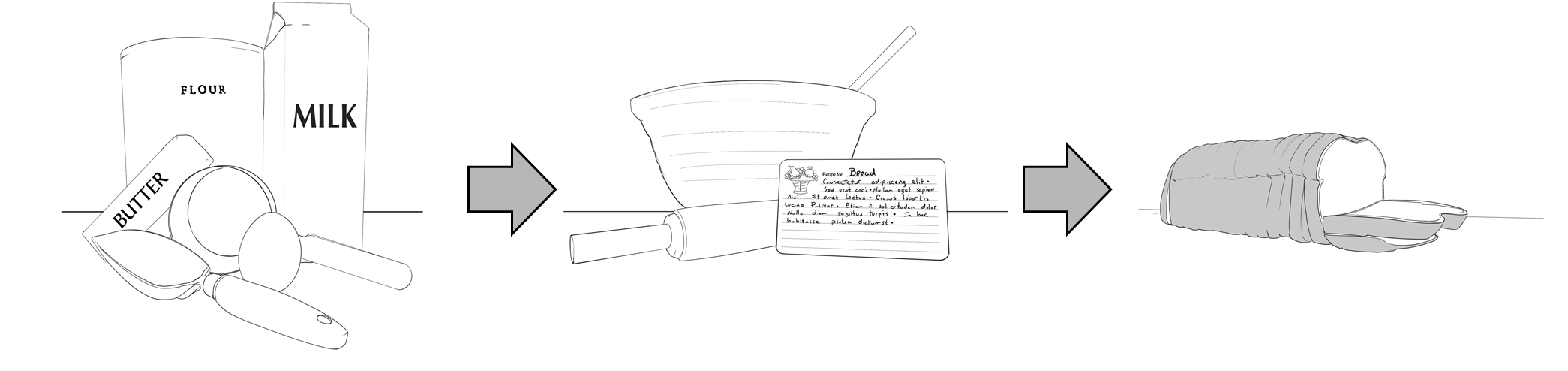

SYNTHESIS: the combination of ideas and elements to form a complete system or theory.

A good metaphor for synthesis is cooking! Imagine the ingredients for a loaf of bread laid out on a kitchen cabinet. Each ingredient—eggs, milk, flour, sugar, salt, yeast—have their own purpose and can be combined in different ways to form food other than bread. Knowing all of those individual attributes that make an egg an egg, or the difference between yeast and flour, is what makes you a chef. When you combine all these ingredients according to the recipe, you get something different than all the ingredients on their own: and most of us would rather eat a slice of bread than a spoonful of flour. The product of synthesis is like bread. Synthesis takes a list of ingredients and makes them into something more than the ingredients alone.

Usually, the writers of a literature review will start with a question that they want to answer through informed and research-based evidence gathered while reading others’ work on related topics. The “thesis” or controlling idea of a literature review may be that same question ( “This review seeks to answer…” ) or it may be a statement describing the reviewed research. The thesis reflects the purpose of the literature review as a genre and is different from the thesis you will write for the research paper that argues a claim or asserts a new idea.

Example 3.1: Look at this thesis statement taken from the introduction of a literature review in environmental psychology on the relationship between “nature sounds” and restorative environments:

From this example, we can learn many things about literature reviews:

- They are explicit and focused on their topic. The opening states an observable truth about the current research ( emphasizes nature ), is followed by a general condition ( positive psychological experiences) within that research, and then finally focuses on describing how a particular outcome is achieved (listening to nature sounds is restorative).

- They seek to pre vent or eliminate misunderstanding. Note the use of specialized key terms, exacting transitional phrases, and meaningful verbs in the thesis such as “ restorative environments,” “in particular,” and “ generate .”

- They seek to forward understanding. In other words, literature reviews examine and link together evidence described and validated in the research of others so a reader can learn how a field is developing. ( Research seems to agree that nature sounds can relieve stress and fatigue–this review will examine that conclusion so readers can understand/ build on how and why.)

Moving from the beginning to the very end of the literature review, we can also learn many things about literature reviews from the sources used. Think of each text listed in the References section of a literature review as contributing pieces to a gigantic puzzle.

Example 3.2: Look at the first three articles listed in the References for the article excerpted above: