What do you normally do in AP English Lang?

<p>I’m in APUSH right now as a sophomore and will be taking AP Eng Lang next year. APUSH isn’t that bad in my opinion. My teacher says my outlines and essays are great, and he’s a really tough grader. I have a 95% in that class.</p>

<p>Anyway, how many hours of homework a day are there in AP Lang? What do you normally do in that class? 1000 word essays? 5000 word essays? Specificity please!</p>

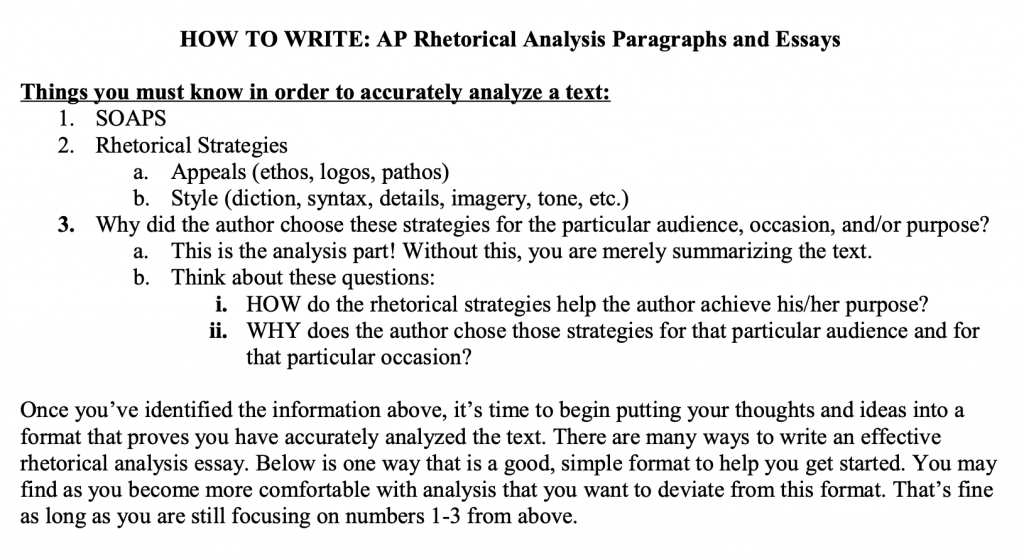

<p>AP English Language is a class about learning how to identify the METHODS and TOOLS that writers use to get their point across or develop character/plot. It is a class wher you need to learn how to read critically. In my AP Lang class last year, the homework was primarily reading whatever we were assigned each night. In our class, there was a significant emphasis on nonfiction works, like essays, speeches, and articles, in addition to actual novels. We usually had to identify things like author’s purpose and types of devices as we read–for example, “this author is using pathos, anaphora, and parallelism to emphasize this argument about this topic.” So the homework isn’t hard, but it can be time-consuming depending on what your teacher gives you. I spent about an hour each night on it (maybe more if we had a lot of reading), but the essays were far more demanding.</p>

<p>The essay prompts you’ll get will likely be quite different from essay prompts you’ve gotten in the past. You’ll be asked to analyze actual text and style rather than just characters or plot. My teacher wanted us to learn about rhetoric and argumentation, so we wrote some very difficult argumentative essays.</p>

<p>As for length, I can’t really say that there’s a normal wordcount for AP Lang work. My teacher’s style was giving us really difficult prompts and a limited amount of space and time to answer them effectively. Expect to churn out stronger essays for more complex prompts in less time.</p>

<p>An example of a prompt I had to write on: “Examine Hamlet’s famous soliloquy in II.ii.501-540 and Claudius’ confession in III.iii.36-72, 97-98. Compare and contrast these characters as dramatic opposites or twins. ** Discuss Shakespeare’s use of literary and rhetorical devices to reveal each character’s state of mind.**” The sentence I bolded is the AP Lang part–analyzing style adds another layer on top of the traditional “talk about this character or plot” prompt.</p>

<p>Any other questions? (English is my best subject, so I’ll admit that I’m biased toward this class. I loved it.)</p>

<p>It all varies by class. My homework/classwork is fairly consistent though. We are always reading 1-2 books (always one that is self-paced/we have one date that the book has to be done by and sometimes a second one that we read x number of chapters for by the following class). Personally I am a quick reader and never spend more then an hour on a school night do the readings. We are also occasionally doing projects (fairly easy) and write journal writes (that is what my teacher calls them, but in reality they are mini papers) after each book, those tend to be 3-6 pages (nothing major). The only other assignment is each quarter we have to find 50 words we don’t know (they can be found from watching TV, talking to friends, reading, listening to music and so on) and document them. Personally I find the class extremely reasonable (I finished last quarter with 102), though I know some people who have struggled with it.</p>

<p>Oh and for what we do in class, we will do practice essays, book discussions, multiple choice practice, test strategies, grammar, history relating to the books and some other random stuff.</p>

<p>It really depends from school to school and class to class in both material and intensity. My friend took it as a junior at his school and it was very intensive. They wrote essays every night. I take it as a senior in a different school and we do nothing for the most part. I’m serious, I go into class, the teacher gets side tracked for 25 minutes, then I hear about what a synthesis essay is, and then it’s time to go. The teacher actually spent one class teaching us about contractions (one can understand why I do dual enrollment). My friend’s class wrote over 100 essays. I have written about 5 so far. </p>

<p>It depends on the school, the teacher, and the class. There’s no way of predicting what the class will be like unless you talk to the current instructor and current students.</p>

<p>I hate English and don’t consider it to be a real subject. That being said, I got a 5 somehow. In class, I always sucked at MC but got 8-9s on essays, considering that I love studying argument. I skipped one section of MC on the exam, but rocked the essays. Good stuff.</p>

<p>How can you not consider English a real subject? Ideas couldn’t be communicated properly without it, and one of the largest art forms (literature) is completely based on it…</p>

<p>AP Language isn’t about how long your essays are. No AP test is like that. If that’s the idea you’ve gotten, you need to get rid of it fast. My teacher told us to get rid of the five paragraph essay format we’ve gotten used to. It’s all about identifying what you’ve been asked in the question, the hidden whats, and communicating your ideas properly with developed evidence. </p>

<p>In my class, we work on vocab and analysis in class, and work on literature. Since my class is a combination of both the language and literature tests, we do a lot a literature as well. You will be writing a lot if your teacher’s class is any good. Good luck on your tests!</p>

<p>I have to do Journals about the books that we are reading, etc. It’s a really fun class because we do AP Practice questions once a while and my teacher is really good. I started to write better as well :D</p>

<p>Well we obviously read the literary cannons: Huck Finn, Gatsby, etc. And we often do presentations that convey we know how to detect rhetorical devices and show the author’s purpose for doing so as well as its effect upon the story. </p>

<p>Then we do a lot of practice essays: argument, style, and synthesis (in chronological order). Argument is self explanatory you get a topic and you either defend, challenge, or qualify. Style you get a piece of text and analyze it for its rhetorical devices and write about how this aids on the authors writing, etc. Synthesis is like an argument but you are given the evidence (which you don’t receive in the argument essay) from 5 sources and have to cite at least 3. </p>

<p>We also do some socratic seminars on a prompt and basically have a massive discussion about it. We do a little more but that’s the gist of it.</p>

<p>We do nothing, each day we do mindless “peerediting” of “essays” which in reality are single paragraph rhetorical responses. Other times we talk about the books we read, go off on random tangents. Our teacher has not mentioned the word Synthesis Essay or Argumentative essay. Am I alone on this?</p>

<p>We did quite a bit of analyzing literature, from short stories and plays in class to independent novels. So far, we’ve read The Great Gatsby, A Separate Peace, To Kill A Mockingbird, Farewell to Manzanar, and currently have Of Mice and Men. (The other period read Things Fall Apart instead of Farewell.) We just finished a unit on persuasion and satire and are starting a unit on identity. We are also working on an analytical research paper, but that’s a requirement from the community college that the class is a dual enrollment opportunity. (A waste of time and money for me. The credits probably won’t transfer to where I want to go) English 11 (What AP Language is replacing credit wise) in Pennsylvania has to be focused on American Lit, which kind of sucks… </p>

<p>The only problem is that the class is huge. My grade has a lot of kids that were, I guess you could say, unjustly placed in honors English as a freshman and, since our school got rid of the honors classes and just have AP, a lot of people took AP when they probably shouldn’t have. Same goes for my AP World class. APUSH is really tough at my school, and a lot of the APWH class are newbies… </p>

<p>But I should do alright on the AP Language exam. Our teacher gave us some practice packets and I’ll review them before the exam. What sucks though is we’re actually off school the day of the exam, so we need our own rides there and home, AND it’s the day before prom… </p>

<p>Sent from my Nexus 7 using CC</p>

<p>My teacher is insane and he assigned a ludicrous amount of books for my class to read throughout the year. I read the first one, used Schmoop and Sparknotes for the rest and pulled out an A. </p>

<p>Not a single kid in my class read a book after he assigned Huck Finn (october) so now we’re all screwed for the AP test. The teacher refuses to review for AP and babbles on about how “it’s the learning that matters, not the test, not your grade.”</p>

<p>So yeah. AP English classes can be pretty terrible if you get a bad teacher, because they don’t need to follow a strict curriculum. </p>

<p>BTW: Anyone have advice/tips for the multiple choice? Nobody in our class can finish the multiple choice on time with above 45 right, but most of us have 22-2400 SATS. A few of us got review books today but we’re not sure whether to use Princeton Review of Cliffnotes. Any advice would be greatly appreciated.</p>

<p>It is one of the most difficult and rewarding classes I took. We were always reading 6-7 books at any one time (a total of something like 36 or more books throughout the year). About half my class did all the reading, the rest got by with Shmoop and such. The essays were incredibly demanding such as:</p>

<p>“Analyze how place and setting mirror character development in [insert three books of your choice]”</p>

<p>That essay was a killer – most people failed because they misread the prompt. The class, I’m sure, varies in difficulty, but it is super rewarding in my view.</p>

<p>I’ve always been an A student and this class conquered me! By far the most work and effort, despite the fact that I thought it would be one of my easier AP classes. It largely (extra emphasis here) depends on the teacher, but you can expect to transform as a writer of the course of the year. Yes, this class took down my GPA a bit, but I also came out a changed writer. I came in thinking my writing was superb and thought I did good on our first diagnostic-ish essay. Boy, was I wrong when I got that 4(out of 9) on an essay. I just took the AP test today and will be upset if I get anything less than a 4 or 5 on it after all the work I put in. This is one of the few classes where no matter how hard you try, you could very well not get the grade you want, regardless of what you do. This is my own personal experience so far… since I envy friends with other teachers who walk away with an easy A’s doing nothing, but remind myself that they have learned nothing in comparison. In other words, your experience in AP lang largely depends on your teacher. There were nights I got little to no sleep. My class did double journals all year, and read/analyzed/annotated too many essays to count. We read less books, but annotated many essays and took numerous practice prompts. Started with a 4/9 on essays, raised them to 5-6/9, and am finally in the place where I can get 7-8/9. </p>

<p>Don’t underestimate this class.</p>

AP English Language and Composition

Review the free-response questions from the 2024 ap exam, new for 2024-25: mcqs will have four answer choices.

Starting in the 2024-25 school year, AP English Language and Composition multiple-choice questions (MCQs) will have four answer choices instead of five. This change will take effect with the 2025 exam. All resources have been updated to reflect this change.

Exam Overview

Exam questions assess the course concepts and skills outlined in the course framework. For more information, download the AP English Language and Composition Course and Exam Description (.pdf) (CED).

Encourage your students to visit the AP English Language and Composition student page for exam information.

Wed, May 14, 2025

AP English Language and Composition Exam

Exam format.

The AP English Language and Composition Exam has question types and point values that stay consistent from year to year, so you and your students know what to expect on exam day.

Section I: Multiple Choice

45 Questions | 1 hour | 45% of Exam Score

- 23–25 Reading questions that ask students to read and analyze nonfiction texts.

- 20–22 Writing questions that ask students to “read like a writer” and consider revisions to stimulus texts.

Section II: Free Response

3 Questions | 2 hours 15 minutes (includes a 15-minute reading period | 55% of Exam Score

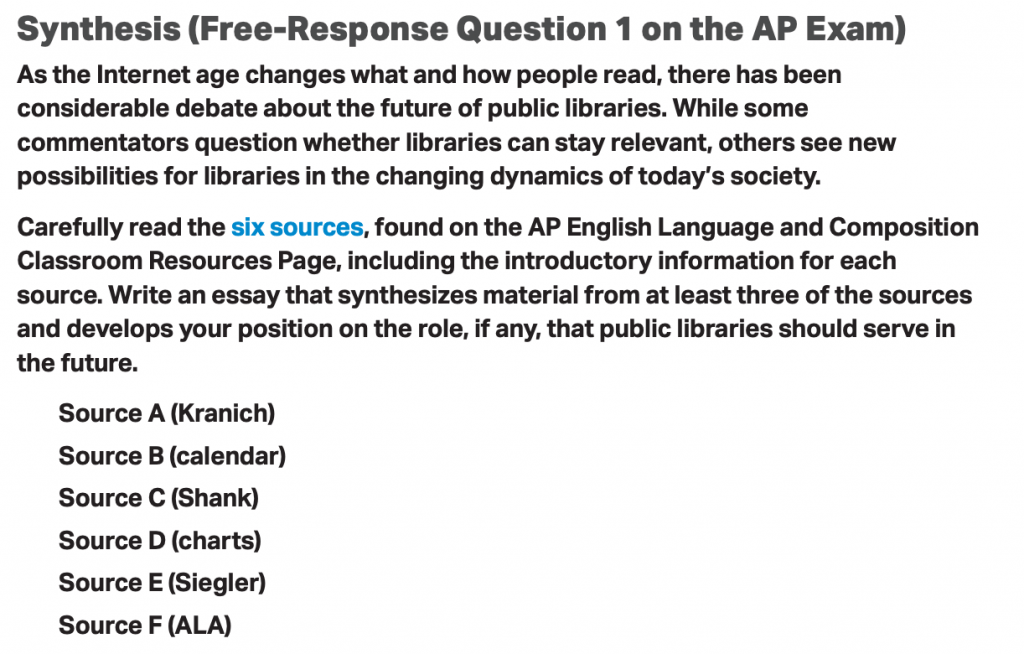

- Synthesis Question: After reading 6 texts about a topic (including visual and quantitative sources), students will compose an argument that combines and cites at least 3 of the sources to support their thesis.

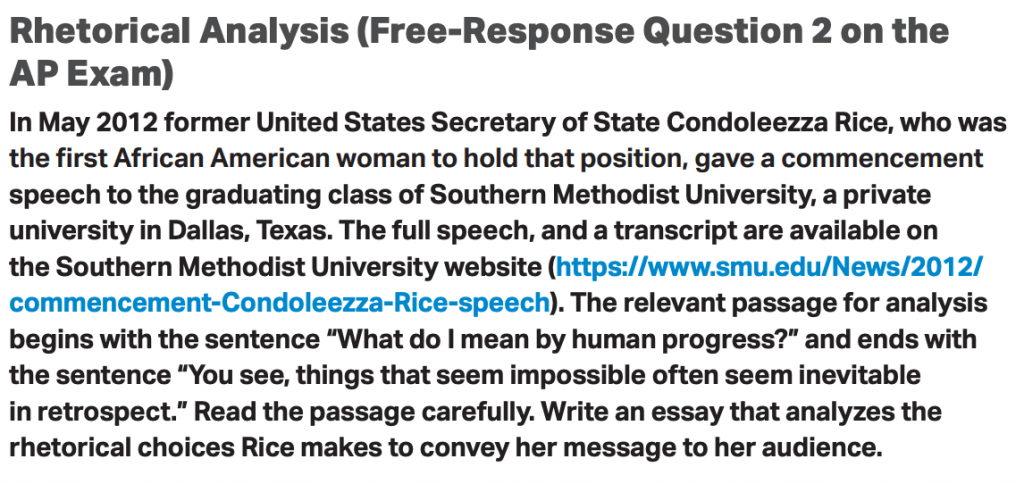

- Rhetorical Analysis: Students will read a nonfiction text and analyze how the writer’s language choices contribute to the intended meaning and purpose of the text.

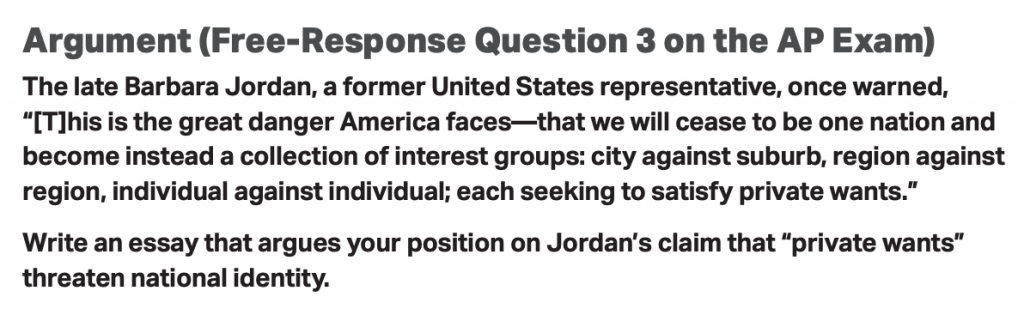

- Argument: Students will create an evidence-based argument that responds to a given topic.

Exam Questions and Scoring Information

Ap english language and composition exam questions and scoring information.

View free-response questions and scoring information from past exams.

Score Reporting

Ap score reports for educators.

Access your score reports.

AP ® Lang teachers: looking to help your students improve their rhetorical analysis essays?

Coach Hall Writes

clear, concise rhetorical analysis instruction.

Is AP Lang Worth It?

September 3, 2022 by Beth Hall

One of the most common questions I received over on TikTok this summer was “Is AP Lang worth it?”

The answer is “it depends.”

As someone who teaches both AP ® Language and Composition and College English (concurrent credit,) I think students need to consider a variety of factors before making this decision.

First and foremost, know that much of what I’m about to say depends on your interests/goals, the high school you attend, the state you live in, and where you want to attend college.

What is AP Lang?

For more information about the class, check out this video here . AP ® Language and Composition is a course offered through The College Board. Students have the option of taking an exam in May. Depending on the score they receive, students can earn college credit. More information on that to follow.

What is concurrent credit?

This term might vary a bit depending on where you live, but for the purposes of this blog post, concurrent credit means a college level class taught at a high school. Students receive both high school and college credit. The college credit often comes from a local college or community college and can transfer to other colleges. More information on this to follow as well.

What is dual enrollment?

Again, this term might very in its meaning depending on your school, but for the purposes of this blog post, dual enrollment is when you take an AP ® class and receive college credit from a local university at the same time.

Availability

In some sense, students are limited to which classes their high school offers. Your school might have more AP ® options than concurrent credit options, or vice versa. Some concurrent credit programs will let students take classes over the summer or online of the school does not offer the class, so definitely talk to your guidance counselor about your options.

Generally speaking, both AP ® exams and concurrent credit classes are less expensive than taking the classes as a college freshman. In that sense, both can be great options.

If cost is a factor, look into the cost of the AP ® exam fee and compare it to the cost of an equivalent concurrent credit class.

There are a few states, mine is one of them, where the state department of education covers the AP ® exam fee for students. Also, in our area, students who qualify for free and reduced lunch can take a couple concurrent credit classes at no cost. Sometimes there are also scholarship options for concurrent credit students. Because this varies from school to school and state to state, talk to your teachers or guidance counselors, as they would likely be able to advise you based on the options in your area.

College Credit

Colleges and universities determine what they will accept for credit, so if you have an idea of which schools you might apply to, see which AP scores they accept and what their concurrent credit policy is. This information is typically on the college or university’s website.

College Credit for AP ® Classes

In regard to AP ® classes, one of the perks is that they are widely accepted for college credit, meaning that if you earn the score the school accepts, it is accepted in place of a college class. If you enter college with multiple AP ® or concurrent credits, you are (in theory) saving money, as you could graduate in 2-3 years instead of 4.

As a word of caution, though, college is a big adjustment, and sometimes “testing out” of several classes, whether it be because of AP ® or concurrent credit, can mean that you end up taking several difficult classes as a freshman–all while you’re adjusting to college life. For some people, this is an easy adjustment. For others, it is a challenge.

The downside of AP ® scores is that you might not earn the score you need. In these instances, I can see how it would be easy to think, “oh man, it was a waste.” But, don’t forget that you are a stronger student because of what you learned in the class. So when asked if AP Lang is worth it even if you don’t make the score you want, I think it is. Honestly, out all the AP ® and concurrent credit options out there, I think AP Lang and College English I (sometimes called Comp. I) are worth it because they reinforce how to read and write about nonfiction, a skill that most students will use in their future classes.

College Credit for Concurrent Credit Classes

With concurrent credit classes, it’s important to realize that in some cases private colleges and out-of-state schools are less likely to accept the concurrent credit. While I know of cases where a student attended a private college or out-of-state college and the schools accepted the concurrent credit, I know cases in which the school did not accept the credit. Just as with a school not accepting an AP ® score, I’d venture to say that the student still gained valuable knowledge from the concurrent credit class even if the credit didn’t transfer.

Moral of the story? Do your research.

Make a spreadsheet of the colleges you’re interested in and keep track of the AP and concurrent credit policies. This will help you make an informed decision once you start applying to colleges and receiving acceptance letters.

For more information about how to make a college list, check out this video here.

This is another factor that varies from school to school. Many schools give a “GPA boost” (5.0 scale) for completing an AP ® class. Schools may or may not give the same GPA boost for concurrent credit or dual enrollment classes.

Is AP Lang Hard?

In addition to being asked “is AP Lang worth it,” I’m also frequently asked if “is AP Lang hard.”

This depends on a variety of factors:

- your interest in English, especially nonfiction

- the classes you have previously taken on will be taking at the same time as AP Lang

- your teacher

- your learning style

- your other commitments (school, family, job, etc.)

- the class content and workload

I love that AP ® Lang focuses on rhetorical analysis, synthesis, and argument, as these are valuable skills. I also love that students are exposed to these skills in different ways throughout the year, as I believe these skills are valuable well beyond the class itself.

Want to know more? Check out this blog post about what is on the AP ® Lang Exam.

So is AP ® Lang hard? Maybe. But one of my goals is to try to make it a little easier for students, which is why I started my YouTube channel and TikTok .

Final Recommendations

When deciding “is AP Lang worth it,” make an informed decision by

- Doing your research to see what all your course options are

- Talking to your teachers, guidance counselors, parents/guardians, and students who have taken the classes at your school in previous years–while it should be your decision, sometimes it’s good to hear other people’s perspectives.

- Making a spreadsheet, t-chart, or list to compare the cost and credits accepted

DISCLAIMER: I am not affiliated with The College Board. The advice and opinions expressed in this video are my own.

For more information about AP ® Language and Composition, please go to The College Board’s website, which can be accessed here.

AP® Lang Teachers

Looking to help your students improve their rhetorical analysis essays?

Latest on Instagram

Shop My TPT Store

AP® English Language

The best ap® english language review guide for 2024.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: February 7, 2024

Navigating the AP® English Language exam is tough. That’s why we wrote this comprehensive AP® English Language study guide.

In this post, we’ll go over key questions you may have about the exam, how to study for AP® English Language, as well as what review notes and practice resources to use as you begin preparing for your exam.

Are you ready? Let’s get started.

What We Review

What’s the Format of the AP® English Language and Composition Exam?

The AP® English Language and Composition exam is broken into two sections: multiple-choice and free-response.

Students are asked to complete 23-25 reading questions focused on rhetorical analysis and 20-22 writing questions focused on making revisions related to diction, syntax, and other grammar concepts. The number of free-response questions remains the same, but they are now scored using an analytic rubric rather than a holistic rubric.

| Section | Time Limit | # of Questions | % of Overall Score |

| I: Multiple Choice | 1 hour | 45 | 45% |

| II: Free Response | 2 hours 15 minutes | 3 | 55% |

How Long is the AP® English Language and Composition Exam?

The AP® English Language and Composition exam is 3 hours and 15 minutes long. Students will have 1 hour to complete the multiple-choice section (45 questions) and 2 hours and 15 minutes to complete the free-response section (3 questions).

How Many Questions Does the AP® English Language and Composition Exam Have?

Section i: multiple choice.

- 5 passages total: 2 Reading and 3 Writing

- 23–25 Reading questions

- 20–22 Writing questions

Section II: Free Response

- 1 Synthesis question

- 1 Rhetorical Analysis question

- 1 Argument question

Return to the Table of Contents

What Topics are Covered on the AP® English Language and Composition Exam?

There are two types of AP® English Language and Composition questions: multiple-choice and free-response.

Because AP® English Language and Composition is a skills-based course, there’s no way to know what specific passages or topics might make it onto the official exam.

However, we know exactly which skills will be assessed with which passages, so it’s best to center your studying around brushing up on those skills! The charts below will help you understand which skills you should focus on.

| Set | # of Questions in Each Set | Skills Assessed |

| 1 | 11-14 | Reading skills 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| 2 | 11-14 | Reading skills 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| 3 | 7-9 | Writing skills 2, 4, 6, 8 |

| 4 | 7-9 | Writing skills 2, 4, 6, 8 |

| 5 | 4-6 | Writing skills 2, 4, 6, 8 |

Note that, even though there are more writing passages, reading passages have a greater total number of questions.

| Skill Category | Exam Weighting |

| 1. Rhetorical Situation — Reading (1.A, 1.B) | 11-14% |

| 2. Rhetorical Situation — Writing (2.A, 2.B) | 11-14% |

| 3. Claims and Evidence — Reading (3.A, 3.B, 3.C) | 13-16% |

| 4. Claims and Evidence — Writing (4.A, 4.B, 4.C) | 11-14% |

| 5. Reasoning and Organization — Reading (5.A, 5.B, 5.C) | 13-16% |

| 6. Reasoning and Organization — Writing (6.A, 6.B, 6.C) | 11-14% |

| 7. Style — Reading (7.A, 7.B, 7.C) | 11-14% |

| 8. Style — Writing (8.A, 8.B, 8.C) | 11-14% |

Like the multiple choice section, the free response section is also skills-based. We cannot predict what specific passages you will be asked to analyze, but we do know the type of essays you will be asked to produce:

- 1 Synthesis essay: After reading 6-7 sources, students are asked to write an essay using at least 3 of the provided sources to support their thesis.

- 1 Rhetorical Analysis essay: Students read a non-fiction text and write an essay that analyzes the writer’s choices and how they contribute to the meaning and purpose of the text.

- 1 Argument essay: Students are given an open-ended topic and asked to write an evidence-based argumentative essay in response to the topic.

What do the AP® English Language and Composition Exam Questions Look Like?

Multiple choice examples.

The Course and Exam Description (CED) for AP® English Language provides 8 practice questions that address reading skills and 9 practice questions that address writing skills.

Below, we’ll look at examples of each question type and the skills and essential knowledge they address.

Skill: 1.A Identify and describe components of the rhetorical situation: the exigence, audience, writer, purpose, context, and message.

Essential Knowledge: RHS-1.B The exigence is the part of a rhetorical situation that inspires, stimulates, provokes, or prompts writers to create a text.

Skill: 3.A Identify and explain claims and evidence within an argument.

Essential Knowledge: CLE-1.A Writers convey their positions through one or more claims that require a defense.

Skill: 5.C Recognize and explain the use of methods of development to accomplish a purpose.

Essential Knowledge: REO-1.J When developing ideas through cause-effect, writers present a cause, assert effects or consequences of that cause, or present a series of causes and the subsequent effect(s).

Skill: 7.B Explain how writers create, combine, and place independent and dependent clauses to show relationships between and among ideas.

Essential Knowledge: STL-1.L The arrangement of clauses, phrases, and words in a sentence can emphasize ideas.

Skill: 2.A Write introductions and conclusions appropriate to the purpose and context of the rhetorical situation.

Essential Knowledge: RHS-1.I The introduction of an argument introduces the subject and/ or writer of the argument to the audience. An introduction may present the argument’s thesis. An introduction may orient, engage, and/or focus the audience by presenting quotations, intriguing statements, anecdotes, questions, statistics, data, contextualized information, or a scenario.

Skill: 4.B Write a thesis statement that requires proof or defense and that may preview the structure of the argument.

Essential Knowledge: CLE-1.I A thesis is the main, overarching claim a writer is seeking to defend or prove by using reasoning supported by evidence.

Skill: 6.A Develop a line of reasoning and commentary that explains it throughout an argument.

Essential Knowledge: REO-1.D Commentary explains the significance and relevance of evidence in relation to the line of reasoning.

Free Response Examples

The Course and Exam Description (CED) for AP® Lang also provides a sample question for each FRQ. Below, we’ll review these examples and which skills they address.

Skills: 2.A, 4.A, 4.B, 4.C, 6.A, 6.B, 6.C, 8.A, 8.B, 8.C

This prompt is long, but it’s important to notice the key task:

- Write an essay that synthesizes material from at least three of the sources and develops your position on the role, if any, that public libraries should serve in the future.

So, your response should:

- Synthesize the material from at least three sources

- Make your position on the topic clear

In a bit, we’ll have a look at the rubric and see this in action.

Rhetorical Analysis

Skills: 1.A, 2.A, 4.A, 4.B, 4.C, 6.A, 6.B, 6.C, 8.A, 8.B, 8.C

The key task in this prompt is to:

- Write an essay that analyzes the rhetorical choices Rice makes to convey her message to her audience.

- Analyze the author’s rhetorical choices

- Connect those choices to the author’s message and how it’s conveyed to the audience

We’ll also have a look at this rubric and learn how these points can be earned.

The key task here is:

- Write an essay that argues your position on Jordan’s claim that “private wants” threaten national identity.

- Use evidence to back up your position

We’ll break down this rubric in a bit.

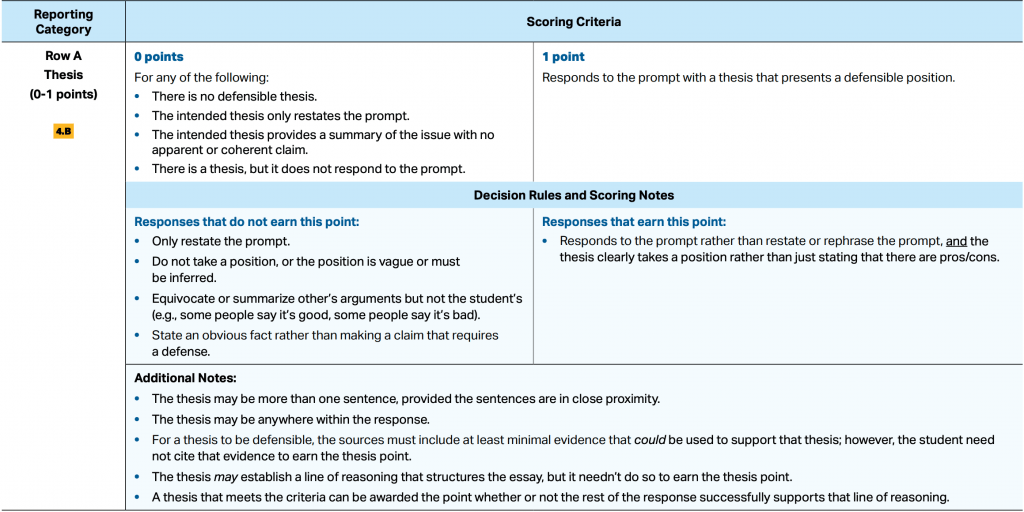

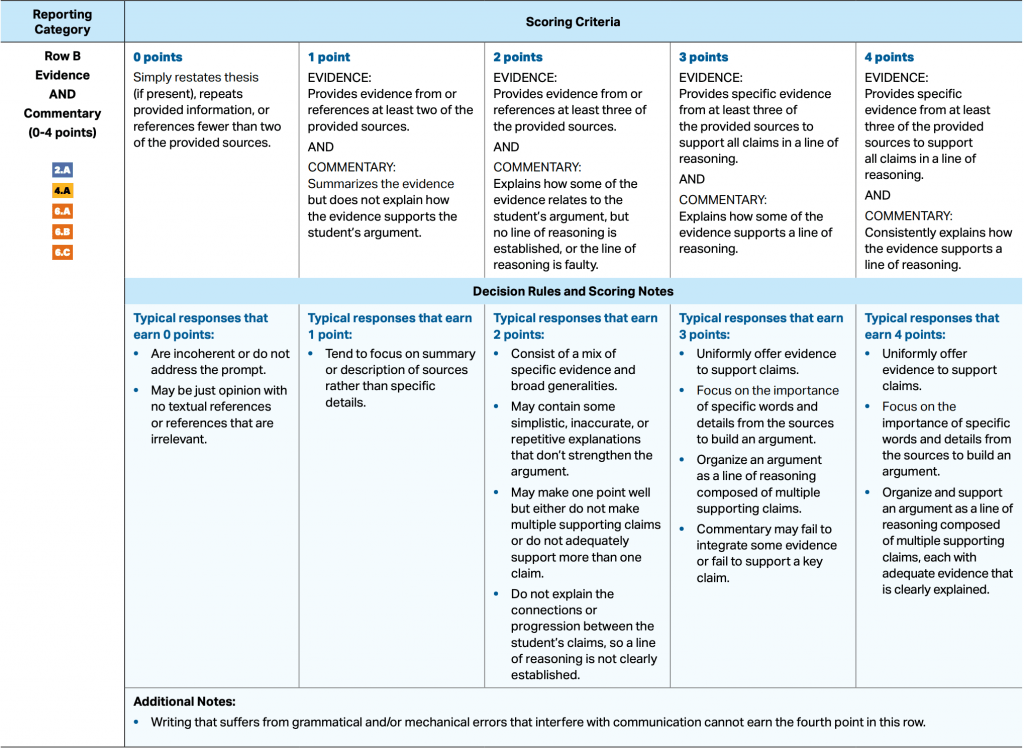

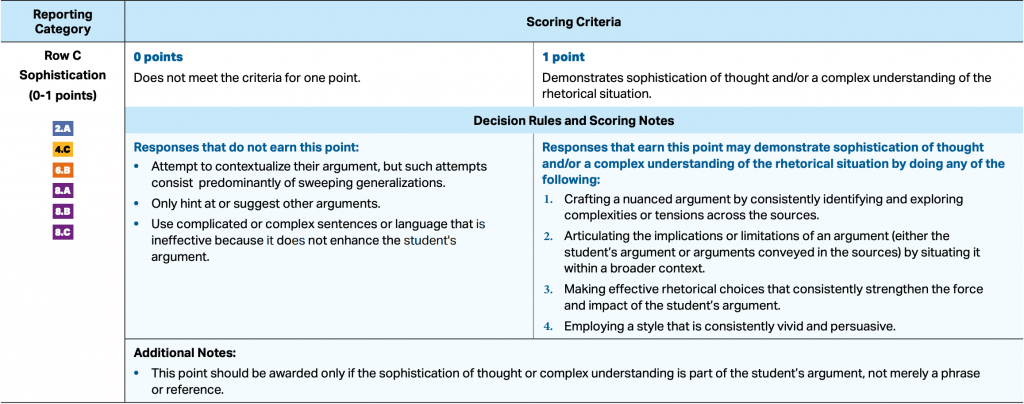

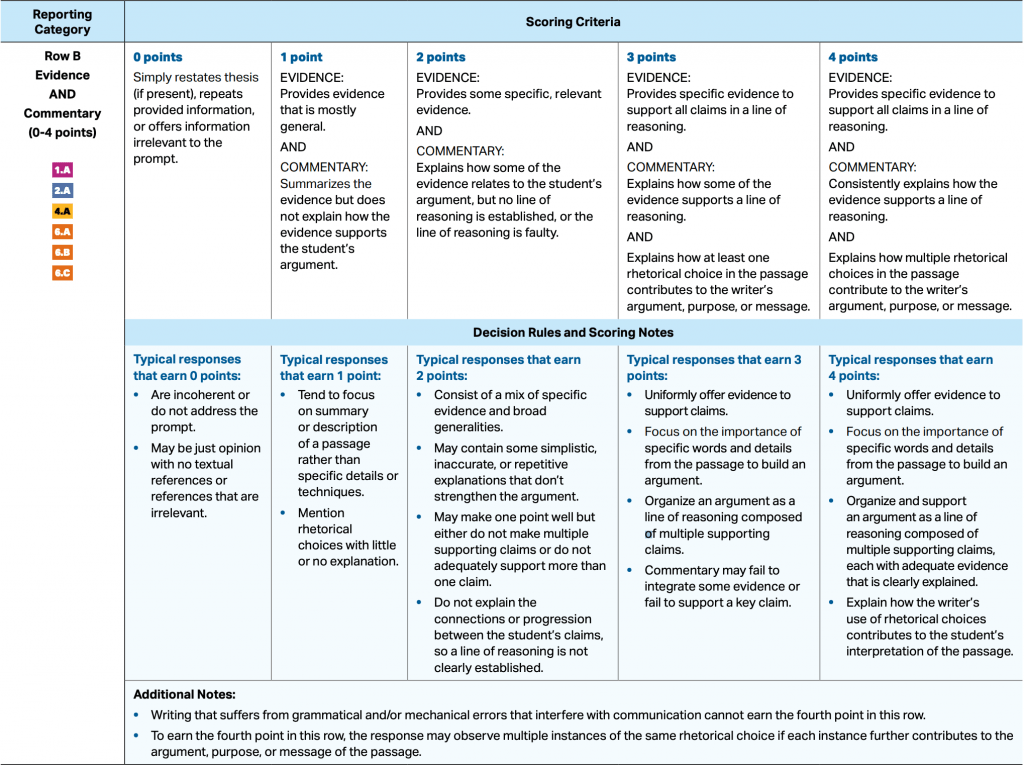

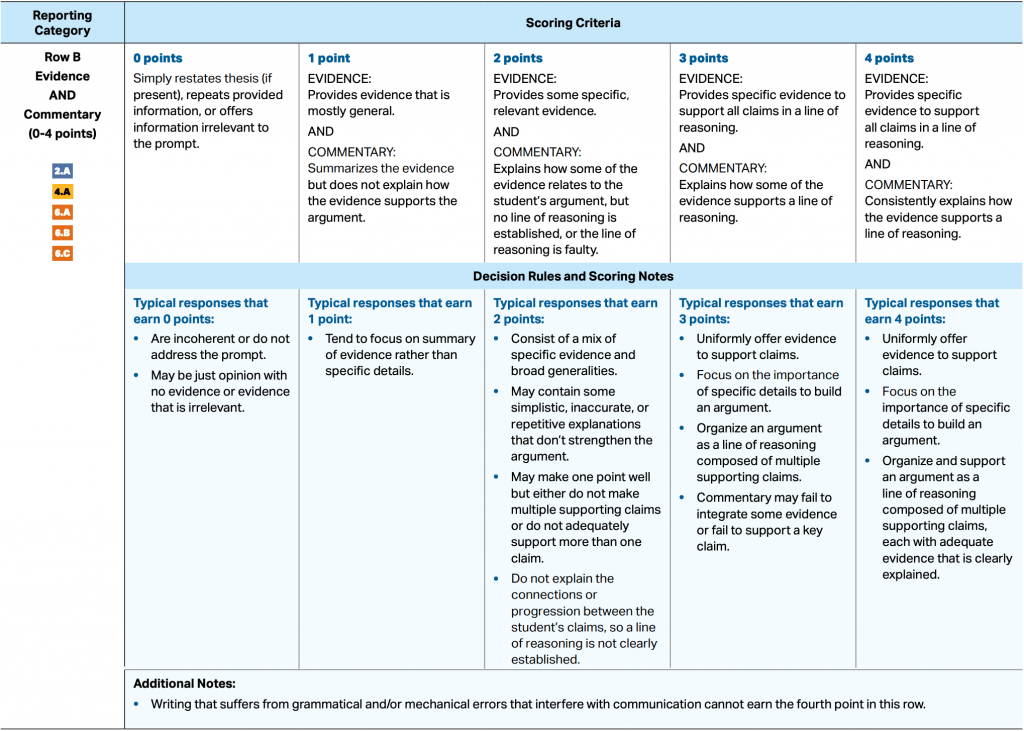

Free Response Rubric Breakdowns

With the 2020 redesign came new rubrics for the AP® Lang essay section. Previously, essays were scored using holistic rubrics, on a scale of 0-9. Starting with the 2019 exam, students’ essays will be graded with new analytic rubrics. Each essay is worth up to 6 points.

Switching to an analytic rubric from a holistic rubric can be tricky, especially if you’ve already taken another AP® English class and are used to the holistic version. But, the best thing about an analytic rubric is that it tells you exactly what to include in your essay to earn maximum points.

Think of the new rubrics as a How To Guide to getting a 6 on each essay. Below, we’ll spend some time breaking down each element of each rubric, but first let’s take a look at the Thesis point, which is pretty similar across all 3 essays.

Row A: Thesis

The Thesis row is all or nothing — you either earn the point or you don’t. It’s important to learn the wording of the rubric to make sure you are crafting an AP-level thesis. Note that you will not earn the point if your thesis:

- Just restates the prompt

- Summarizes the issue without also making a claim

- Doesn’t respond to the prompt

That’s all pretty straightforward, but earning the point for this category is a little more tricky than it seems at first. You will earn the point if your thesis:

- Responds to the prompt with a defensible position

- Takes a clear position that does not simply state there are pros and cons to the issue

Notice the second point above. While you may want to include a counterargument in the body of your essay (more on this later), your thesis is not the place to do so.

The purpose of presenting a counterargument is to refute it then and make your own argument stronger. Presenting the opposing argument in your thesis gets confusing for a reader and can make it seem like you aren’t holding strong in your own position, so it’s best to save that for the body of your essay.

The Additional Notes section of the rubric is also important to understand. This details what may or may not earn the thesis point. The main takeaways here are:

- Your thesis may be more than one sentence, as long as those sentences are near one another

- Your thesis doesn’t have to be in your opening paragraph

- Your sources must support your thesis, but you do not necessarily need to cite them

- Your thesis doesn’t have to outline your argument

- Your thesis statement can earn the point independent of whether or not your essay supports it on the whole

The Synthesis Rubric

As we’ve already discussed, the synthesis essay is the first of the three. You will be presented with 6-7 sources related to a given topic and asked to write an essay using at least 3 of those sources to support your thesis.

Let’s take a look at the various elements of the rubric and how you can earn maximum points for each category.

Row B: Evidence and Commentary

The Evidence and Commentary row is a little more flexible than the Thesis row. You can earn between 0 and 4 points depending on the quality of the evidence and commentary that you provide. Note you will not earn any points if your evidence and commentary:

- Does nothing more than restate your thesis

- Repeats already given information

- References fewer than 2 of the sources

- Is just opinion without any textual evidence

The nice thing about this section is that there are lots of places you can earn points! You will earn full points if your evidence and commentary:

- Contains specific evidence from at least 3 of the sources

- Fully supports your claim and line of reasoning

- Explains how the evidence supports your claim and line of reasoning

- Pulls specific words or details from the sources that support your argument

- Supports a line of reasoning that is broken down into supporting claims, with each supporting claim supported by its own pieces of evidence

The final point in the above list is the main difference between earning full points and partial points in this section. AP-level evidence and commentary will not only support your overall claim, but will also support your supporting claims fully.

You can think of supporting claims as each individual body paragraph’s focus. If each body paragraph makes a supporting claim, and that supporting claim is bolstered by specific supporting evidence, you are much more likely to earn the full 4 points here.

The Additional Notes section of the rubric is also important to understand. This gives extra detail on what may or may not earn the thesis point. The main takeaway here is that your argument must be free of grammatical and/or mechanical errors in order to earn full points. This means that if your grammar is not solid, you can only ever earn 3 or fewer points in this section.

If you struggle with grammar or syntax, check out Albert’s Grammar course to help build up those skills!

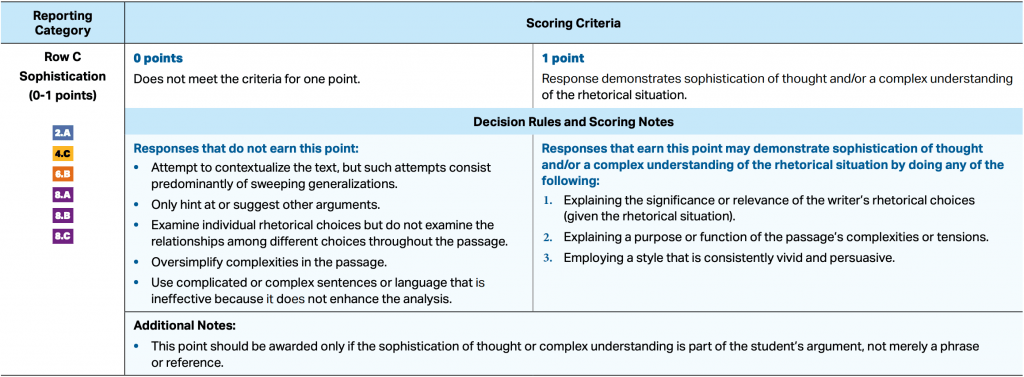

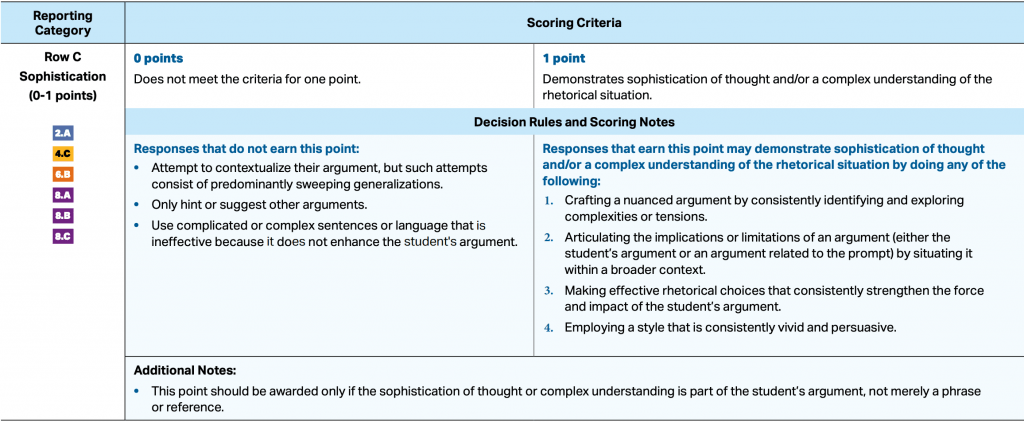

Row C: Sophistication

Similar to the Thesis point, the Sophistication row is also all or nothing — you either earn the point or you don’t.

Where the Sophistication point differs from the Thesis point is that it’s a bit more difficult to understand how to earn it! The rubric states that essays that earn the point “demonstrate sophistication of thought and/or a complex understanding of the rhetorical situation.”

In plain English, this means that you will not earn the point if your essay:

- Contains sweeping generalizations

- Only hints at other positions on the argument

- Uses complex sentences or language that doesn’t add anything to the argument

You will earn the point if your essay:

- Explores complexities or tensions between the provided sources, creating a more nuanced argument

- Acknowledges implications or limitations of your own argument through counterarguments

- Acknowledges implications or limitations of the sources’ arguments by situating them within the broader context of the argument

- Makes purposeful rhetorical choices that strengthen your argument

- Uses vivid and persuasive style

Note that you will not earn the point for this section if the items listed above are done in a single sentence or two. These elements must be present throughout your argument.

The Rhetorical Analysis Rubric

The rhetorical analysis essay is the second of the three. You will be presented with a non-fiction text and asked to write an essay that analyzes the writer’s choices and how they contribute to the meaning and purpose of the text.

- Gives information irrelevant to the prompt

- Explains how multiple rhetorical choices contribute to your understanding of the author’s argument, purpose, or message

- Pulls specific words or details from the passage that support your argument

The Additional Notes section of the rubric is also important to understand. This gives extra detail on what may or may not earn the thesis point. The main takeaways here are:

- You may address the same rhetorical choice more than once, as long you are addressing different instances of it.

- Your argument must be free of grammatical and/or mechanical errors in order to earn full points. This means that if your grammar is not solid, you can only ever earn 3 or fewer points in this section. If you struggle with grammar or syntax, check out Albert’s Grammar course to help build up those skills!

- Analyze individual rhetorical choices made by the author without also examining the relationships between the choices throughout the passage

- Oversimplify the passage

- Explains the significance of the writer’s rhetorical choices

- Explains the purpose or function of the complexities or tensions in the passage

The Argument Rubric

The argument essay is the last of the three. You will be given an open-ended topic and asked to write an evidence-based argumentative essay in response to the topic.

The final point above might be confusing at first glance. Giving your opinion is natural in an essay that literally asks for your opinion! But, the key is making sure to back up your opinion with evidence.

- Focuses on the importance of specific details to build your argument

- Explores complexities or tensions between the various elements of your argument, creating a more nuanced argument

- Acknowledges implications or limitations of your own argument through counter arguments

- Acknowledges implications or limitations of the prompt’s argument by situating it within a broader context

What Can You Bring to the AP® English Language and Composition Exam?

The College Board is rather specific about what you can and cannot bring to an AP® exam. You are at risk of having your score not count if you do not carefully follow instructions. We recommend that you carefully review these guidelines and pack your bag the night before so that you do not have any additional stress on the morning of the exam.

What You Should Bring to Your AP® English Language Exam

If you’re taking the paper AP® English Language exam in-person at school, you should bring:

- At least 2 sharpened No. 2 pencils for completing the multiple choice section

- At least 2 pens with black or blue ink only. These are used to complete certain areas of your exam booklet covers and to write your free-response questions. The College Board is very clear that pens should be black or blue ink only, so be sure to double-check!

- If you are concerned that your exam room may not have an easily visible clock, you are allowed to wear a watch as long as it does not have internet access, does not beep or make any other noise, and does not have an alarm.

- If you do not attend the school where you are taking an exam, you must bring a government issued or school issued photo ID.

- If you receive any testing accommodations , be sure that you bring your College Board SSD Accommodations Letter.

What You Should NOT Bring to Your AP® English Language Exam

If you’re taking the paper AP® English Language exam in-person at school, you should not bring:

- Electronic devices. Phones, smartwatches, tablets, and/or any other electronic devices are expressly prohibited both in the exam room and break areas.

- Books, dictionaries, highlighters, or notes

- Mechanical pencils, colored pencils, or pens that do not have black/blue ink

- Your own scratch paper

- Reference guides

- Watches that beep or have alarms

- Food or drink

This list is not exhaustive. Please check with your teacher or testing site to make sure that you are not bringing any additional prohibited items.

How to Study for AP® English Language and Composition: 7 Steps

Start with a diagnostic test. Ask your teacher if they can assign you one of our full-length practice tests as a jumping-off point. Your multiple choice will be graded for you, and you can self-score your FRQs using the College Board’s scoring guidelines. If you would prefer to take a pencil and paper test, Princeton Review or Barron’s are two reputable places to start. Be sure to record your score.

Once you’ve completed and scored your diagnostic, it’s time to put the results to work and create a study plan.

- If you used Albert, you’ll notice that each question is labeled with the skill that it assesses. If any skills stand out as something you’re consistently getting wrong, those concepts should be a big part of your study plan.

- If you used Princeton Review, Barron’s, or another paper test, do your best to sort your incorrect answers into the skill buckets.

The tables below sort each set of skills into groups based on their Enduring Understandings and Big Ideas.

Big Idea: RHETORICAL SITUATION (RHS)

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Individuals write within a particular situation and make strategic writing choices based on that situation.

| Identify and describe components of the rhetorical situation: the exigence, audience, writer, purpose, context, and message. |

| Explain how an argument demonstrates understanding of an audience’s beliefs, values, or needs. |

| Write introductions and conclusions appropriate to the purpose and context of the rhetorical situation. |

| Demonstrate an understanding of an audience’s beliefs, values, or needs. |

Big Idea: CLAIMS AND EVIDENCE (CLE)

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Writers make claims about subjects, rely on evidence that supports the reasoning that justifies the claim, and often acknowledge or respond to other, possibly opposing, arguments.

| Identify and explain claims and evidence within an argument. |

| Identify and describe the overarching thesis of an argument, and any indication it provides of the argument’s structure. |

| Explain ways claims are qualified through modifiers, counterarguments, and alternative perspectives. |

| Develop a paragraph that includes a claim and evidence supporting the claim. |

| Write a thesis statement that requires proof or defense and that may preview the structure of the argument. |

| Qualify a claim using modifiers, counterarguments, or alternative perspectives. |

Big Idea: REASONING AND ORGANIZATION (REO)

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Writers guide understanding of a text’s lines of reasoning and claims through that text’s organization and integration of evidence.

| Describe the line of reasoning and explain whether it supports an argument’s overarching thesis. |

| Explain how the organization of a text creates unity and coherence and reflects a line of reasoning. |

| Recognize and explain the use of methods of development to accomplish a purpose. |

| Develop a line of reasoning and commentary that explains it throughout an argument. |

| Use transitional elements to guide the reader through the line of reasoning of an argument. |

| Use appropriate methods of development to advance an argument. |

Big Idea: STYLE (STL)

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: The rhetorical situation informs the strategic stylistic choices that writers make.

| Explain how word choice, comparisons, and syntax contribute to the specific tone or style of a text. |

| Explain how writers create, combine, and place independent and dependent clauses to show relationships between and among ideas. |

| Explain how grammar and mechanics contribute to the clarity and effectiveness of an argument. |

| Strategically use words, comparisons, and syntax to convey a specific tone or style in an argument. |

| Write sentences that clearly convey ideas and arguments. |

| Use established conventions of grammar and mechanics to communicate clearly and effectively |

Once your list of practice questions is complete, check out our 5 AP® English Language and Composition Multiple Choice Study Tips for some pointers.

Now that you’ve got your multiple-choice study plan in place, it’s time to make a plan for the FRQs. You should have self-scored your essays using the College Board’s scoring guidelines . If you notice that there is one particular prompt you struggled with, use Albert’s AP® Lang FRQ prompts for more practice!

If you didn’t struggle with a particular prompt as much as you did a particular part of the rubric, try to figure out where you went wrong. Does your thesis restate the prompt instead of proposing your own position? Did you remember to provide evidence but forget to bolster it with commentary? Maybe your word choice wasn’t varied enough to earn the sophistication point. Whatever element you struggled with, have a look at our 5 AP® English Language and Composition FRQ Study Tips for some expert advice.

Once you’ve compiled your entire study plan using the link above and identified the skills you need to practice, it’s time to implement your plan! Check your calendar. How many days, weeks, or months do you have until your exam? Pace your studying according to this time frame. Pro-tip: If you only have a few weeks or days to go, prioritize the skills that you scored the lowest on.

About halfway through your study schedule, plan to take a second diagnostic test to check your progress. You can either have your teacher assign another full-length Albert practice test or use one of the additional practice tests included in whatever AP® English Language and Composition review book you purchased. Use these results to inform the rest of your study schedule. Are there skills that you improved on or scored lower on this time? Adjust accordingly, and use our tips in the next section to guide you.

AP® English Language and Composition Review: 15 Must-Know Study Tips

Like anything else, learning to read and write at the AP® level takes time and practice. Whether this is the first AP® class you’ve taken or you’re just looking to brush up on your study skills, this list of tips will put you in a position to earn a passing score in May.

5 AP® English Language and Composition Study Tips for Home

1. Read. Read widely. Read constantly. Read everything.

There’s no substitute for reading. Reading has a number of benefits: a more impressive vocabulary, a better understanding of varied sentence structure and syntax, facility analyzing how and why authors make specific rhetorical choices. The more you read, the better equipped you will be to ace this exam.

2. Flashcards are your friend.

You will need to have a strong understanding of literary devices and rhetorical techniques, and you don’t want to waste time scrambling for definitions on exam day. Make yourself some flashcards with the most common literary devices and rhetorical techniques, and don’t forget to include grammar and punctuation there too. After all, a writer’s use of grammar and punctuation has as much impact on their prose as the words they use!

3. Take your homework assignments seriously, especially summer assignments.

Your teacher didn’t ask you to read that book for no good reason, or to write that essay just because! Summer assignments help to ensure that you are starting your school year off on the right foot. Every time that you complete a homework assignment, you are one step closer to earning a passing score on your exam. “Practice makes perfect” is a well-known phrase for a reason!

4. Seek out extra opportunities for practice!

Many practice books are available for purchase, and sometimes you can even find e-book versions to check out from your local library. Princeton Review and Barron’s are the most popular, but tons more can be found with a simple Google search.

5. Study with your friends!

Studying alone can sometimes be monotonous, and you might not have a lot of motivation if the only person holding you accountable is you. Forming study groups with friends and classmates ensures that you are held accountable, and it never hurts to have multiple perspectives on an essay question or multiple-choice answer. Plus, it’s just plain more fun.

5 AP® English Language and Composition Multiple Choice Study Tips

1. practice answering multiple-choice questions as often as you can. .

AP® English Language and Composition multiple choice questions will fall into one of the following buckets: rhetorical situation, claims and evidence, reasoning and organization, and style. If these categories look familiar to you, that’s because these are also the four Big Ideas outlined in the AP® Lang CED .

2. Exercise your close-reading skills.

The true key to acing the multiple choice section of this exam is staying engaged with the passages provided to you and actively reading. Active reading looks different to different people, so find what works best for you! For some, this can mean annotating as they read the passage. For others, this can mean reading the passage more than once: the first time just to scan for important information, and the second time to gain a deeper understanding.

3. Look over the questions before reading the passage.

This tip doesn’t work for all readers, but it can be helpful if you’re someone who gets easily distracted when reading! If you find your mind wandering when reading AP® Lang passages, knowing the questions beforehand can give your brain a purpose to focus on.

4. Use process of elimination.

Typically, an AP® Lang multiple choice question will have one or two answer choices that can be crossed off pretty quickly. See if you can narrow yourself down to two possible answers, and then choose the best one. If this strategy isn’t working on a particularly difficult question, it’s perfectly okay to circle it, skip it, and come back to it at the end.

5. Remember that it doesn’t hurt to guess.

Guessing on every single question isn’t a good strategy, of course, but you are scored only on the number of correct answers you give, not the number of questions you answer.

5 AP® English Language and Composition FRQ Study Tips

1. practice answering questions from the college board’s archive of past exam questions. .

Typically, the same skills are assessed from year to year, so practicing with released exams is a great way to brush up on your analysis skills.

2. Time yourself.

On test day, you are free to work on all three essays at your own pace so long as you finish within the 2-hour and 15-minute time frame. But, College Board directions recommend that you spend no longer than 40 minutes on each individual essay—not including the 15-minute reading period. So, while you’re practicing with the archive linked in Tip #1, be sure to have a timer handy!

3. Use the rubric!

The best part about the AP® English Language and Composition revised rubrics and scoring guidelines is that it’s very clear what elements are needed to earn full credit for your essay. Ensure that your thesis statement is clear and defensible; you provide specific evidence and commentary that supports your thesis; and you develop a clear and compelling argument.

4. Pay attention to the task verbs used in your FRQ prompts.

The College Board deliberately includes these to help you guide your response. Task verbs you’ll see on the exam are: analyze, argue your position, read, synthesize, and write. Further breakdown of each of these task verbs can be found at the bottom of this College Board Writing Study Skills list.

5. Know your rhetorical devices and techniques.

While you don’t need to call out these techniques and devices by name, you do need to know their purpose and effect on the passage. For example, maybe you know that the author is deliberately understating something for effect and to draw attention to something, but you can’t remember that the term for this is litotes. As long as you can successfully show this understatement’s effect on the overall piece and connect it back to your thesis, you’ll be okay.

The AP® English Language and Composition Exam: 5 Test Day Tips to Remember

1. get everything ready to go the night before..

Nobody wants to be scrambling around the morning of the exam with a million things left to do! Make sure you have everything from our What You Should Bring list in your backpack and ready to go.

2. Make sure you know where your testing site is and how to get there, especially if you’re taking the exam someplace other than your own school.

If you’re getting a ride from a parent or friend, be sure they know the address beforehand. If you’re taking public transit, check the schedule. Don’t get too comfortable if you are taking your exam at your own school. Be sure you know the room number! This is something small but impactful that you can do to reduce your stress the morning of your exam.

3. Be sure to eat.

We know, every teacher tells you this, but it’s for a good reason! If you’re hungry during the exam, it might be harder for you to focus, leading to a lower score or an incomplete exam. Making sure that you’ve eaten before taking your exam eliminates one less distraction, helping you stay focused and on task.

4. Bring mints or gum with you.

The rules say that you can’t have food or drink in the testing room, but mints and/or gum are usually allowed unless it’s against your testing site’s own rules. If you find yourself getting distracted, pop a mint in your mouth! This can help to keep you more awake and focused.

5. Breathe! Seriously, breathe.

If you’ve followed the rest of the tips in this post, listened to your teacher, and done your homework, you’re well-prepared for this exam. Trust that you have done all you can do to prepare and don’t cram the morning of. Last-minute studying helps no one!

AP® English Language and Composition Review Notes and Practice Test Resources

Write space.

This site provides AP® Lang students and teachers with resources on rhetorical analysis, synthesis, argument, grammar support, and much much more to help guide you through the AP ® English Language and Composition exam.

How to Guide for Rhetorical Analysis Essays

This step-by-step guide will take you through writing a rhetorical analysis essay from beginning to end.

AP® English Language and Composition Survival Guide

This survival guide is a one-stop-shop for everything you need to about multiple choice questions, essay writing, rhetorical terms, and more!

Ms. Effie’s Lifesavers

If you’re a seasoned AP® English teacher, Ms. Effie (Sandra Effinger) probably needs no introduction! Ms. Effie’s Lifesavers has helped many an AP® Lang (and Lit!) teacher plan effective and thoroughly aligned lessons and assignments. Sandra was an AP® Reader for many years, so she knows her stuff. She has tons of free content on her page, as well as a Dropbox full of AP® English goodies for anyone who makes a donation via her PayPal.

AP® Study Notes

This site has some great sample essays written at the AP® level. They also have a section dedicated to rhetorical terms, which is great if you want to make flashcards for review.

Summary: The Best AP® English Language and Composition Review Guide

Remember, the structure of the AP® Lang exam is as follows:

Because AP® English Language and Composition is a skills-based course, there’s no way to know what specific passages or topics might make it onto the official exam. But, we do know exactly which skills will be assessed with which passages, so it’s best to center your studying around brushing up on those skills!

Start with a diagnostic test, either on Albert or with a pencil and paper test via Princeton Review or Barron’s . Once you’ve completed and scored your diagnostic, follow our 7 steps on how to create an AP® English Language and Composition study plan.

Read! The more you read, the better equipped you will be to ace this exam.

Practice answering multiple choice questions on Albert and free-response questions from The College Board’s archive of past exam questions.

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, why do students struggle with ap lang.

Okay I've heard from so many people that AP Lang is notoriously difficult. I might take it next year, but I'm sort of nervous about it. Can anyone tell me why AP Lang has such a reputation for being so difficult? What is it about the class that makes people struggle?

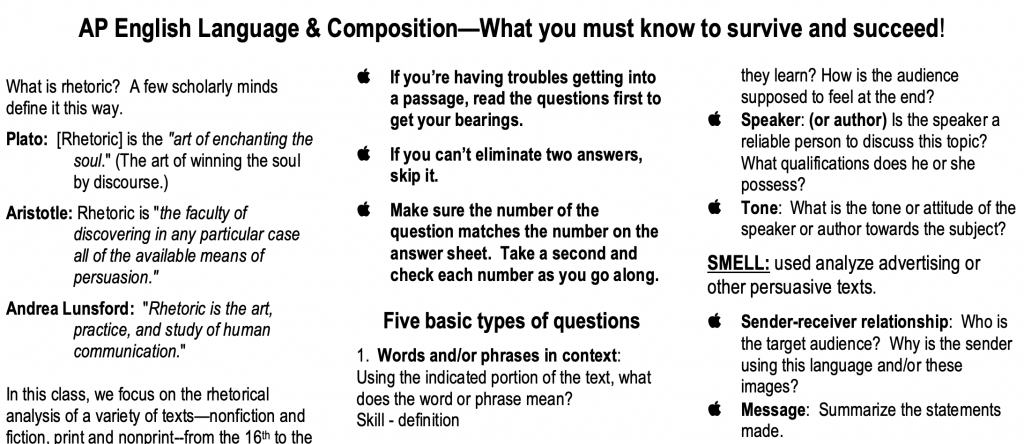

There are a few reasons why students might find AP Lang challenging, and it's essential to understand these factors to prepare effectively for the class.

1. Analytical reading and writing skills: AP Lang focuses heavily on refining analytical reading and writing skills. It requires students to dissect sophisticated written pieces, understand the author's arguments and motives, and develop logical and persuasive essays in response to the author. These tasks require a strong grasp of rhetoric and a deeper understanding of language.

2. Time management: Crafting well-structured and persuasive essays can be quite time-consuming for some students, as you’ll often need to revise your essay at least a couple of times to get it to where you want. It's crucial to develop good time management skills, so that you can balance your AP Lang workload with other academic and extracurricular responsibilities.

3. Multiple-choice questions: The multiple-choice section of the AP Lang exam covers various aspects of language, such as vocabulary, syntax, and rhetorical strategies. Many students find these questions challenging because they require a thorough understanding of the material and careful attention to detail.

4. Writing style diversity: Throughout the course, students explore different rhetorical modes (narration, exposition, description, argumentation) and essay formats (e.g., synthesis, rhetorical analysis, and argument). The need to adapt writing styles, analyze texts from various genres, and maintain a strong voice across assignments can be tough for some students.

5. High expectations: As an AP course, AP Lang expects students to excel at a college level. Relative to other high school English classes, the course may involve increased workload, group discussions, and assignments that go beyond simply understanding the material. Students are encouraged to think critically, engage in complex ideas, and formulate original and persuasive arguments, and doing those things consistently takes a lot of brainpower.

To tackle these challenges and succeed in AP Lang, it's essential to stay organized, practice reading and writing consistently, and develop strong analytical skills. Seek help from your teacher or peers if you need assistance, and don't be afraid to challenge yourself! Good luck!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

The First Week of AP Language

How in the world do we start?

There are so many ways to design an AP English Language course, that it’s hard to decide what to do the first week. For some schools, schedules are pretty fluid the first ten days or so, so you may be constantly dropping and gaining students. For others, students might be allowed to drop classes they find too challenging, so the classroom dynamic keeps changing. I’ve never been in either situation; in both the schools in which I taught Lang, schedules were pretty much locked in for upper-level upperclassmen, and they weren’t allowed to drop. My problem in both schools was schedule modification because of extended homeroom. I might have had one class that met for 30 minutes and another that lasted 90. That drove me bonkers.

Ideal world: If I had the same students every day for the first week of school, and we met for the same amount of time each of those days, here’s how I would run that first week.

Day 1: Get to know students as teenagers and as learners.

I’m a little old school when it comes to the seating chart. I line ’em up in rows for the first two weeks until I have learned names and figured out how students interact with each other. After that, I change it up every few days depending on the activity we have going on.

I have three icebreakers I love to use, and they help me figure out how to group students later. All of them work with extroverts, introverts, and ‘tweeners like me.

I then use a couple of learning style and work style inventories for insight into how they learn.

We do spend a few minutes on the obligatory student information form, and I go over some basic course requirements (textbooks, materials they’ll need, how I want their binders divided, etc.).

Students are reminded of our school-wide independent reading program , and I show them where to sign up their books and how to check books out from my personal classroom library.

Day 2: Dive right in with a baseline writing assignment

It’s time for these never-made-below-an-A-type-A kids to experience some humility. We do a 40-minute in-class rhetorical analysis essay on a cold prompt. I give them lined paper, require that they use a black pen, and hand them the most challenging prompt I can find: the 1998 letter from Charles Lamb to William Wordsworth. This baby will separate the cream from the milk, the wheat from the chaff, the tired metaphor from . . . another tired metaphor. The problem this year is that we won’t have anchor papers for it on the new analytic rubric .

Why this prompt? The letter was written in 1801, and the tones are SUBTLE. I want to know who in the room can run with a 19th century piece with layered tones. Full disclosure: I’ve always taught Honors English 10 as well as AP Lang, so I knew many of my students. I had the relationship to scare them a bit without shutting them down.

Then comes the first assignment. Yes, they have homework. No, it’s not overwhelming. I give them hard copies of “Our Barbies, Ourselves” by Emily Prager and have them read and mark it up for whatever they notice. I also ask them to bring in Barbie dolls and GI Joe-type action figures.

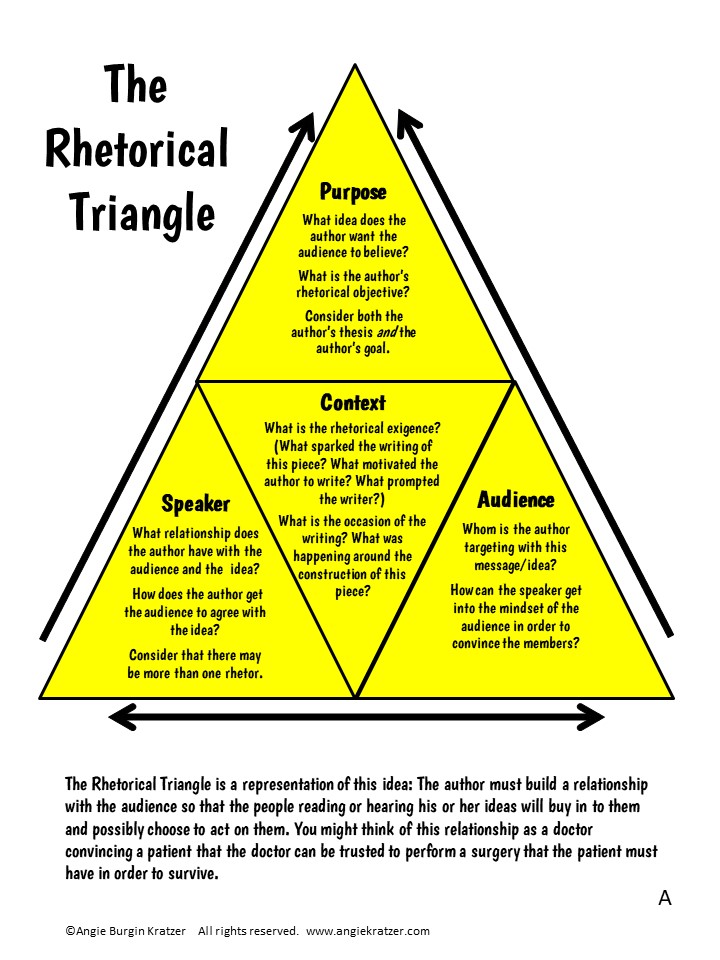

Day 3: Introduce the Rhetorical Triangle.

Using “Our Barbies, Ourselves,” I introduce the Rhetorical Triangle, and we line the toys up along my white board tray and discuss the author’s claim and whether or not she makes her argument well.

Day 4: Introduce S.O.A.P.S.

Students learn SOAPS (subject, occasion, audience, purpose, speaker), apply it to stale text (“Our Barbies, Ourselves”) and then apply it to cold text with “The Black Table is Still There.”

Day 5: Introduce tone.

Students have learned the bare-boned basics of rhetoric, and now we get into strategies. I LOVE teaching tone for many reasons, and my first lesson always includes a skit that changes in meaning based on the way the parts are read. I give out an exhaustive list of tone words, categorize them with the students, and then assign “tone parts” to help them see how tone dictates meaning. Students pair up with their assigned tones and perform the mini skit for the class with whatever prompts they want to use. Here’s the script:

Person A: No, you didn’t.

Person B: Yes, I did.

Person A: Where?

Person B: On the other side of town.

Person A: Was it expensive?

Person B: Are you kidding?

Image the tone pair being aghast/triumphant. Now imagine the tone pair being approving/guilty. Are they talking about a heist? A good sale? A new car? A clandestine meeting? Students have a lot of fun with this activity, and you can switch it up with different types of dialogue.

So, there you have it. I will send you my complete pacing guide if you’re interested. If you’re on a 180-day schedule, get this pacing guide . If you’re on a 90-minute block, get this pacing guide .

I’m a recovering high school English teacher and curriculum specialist with a passion for helping teachers leave school at school. I create engaging, rigorous curriculum resources for secondary ELA professionals, and I facilitate workshops to help those teachers implement the materials effectively.

- AP Language Exam

- Argumentation & Persuasion

- Grammar & Usage

- Reading Instruction

- Rhetorical Analysis

- Teacher Tips & Best Practices

- The Research Process

- Uncategorized

- Writing Instruction

Copyright © 2023 Angie Kratzer Site Design by Laine Sutherland Designs

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the AP Lang Argument Essay + Examples

What’s covered:, what is the ap language argument essay, tips for writing the ap language argument essay, ap english language argument essay examples, how will ap scores impact my college chances.

In 2023, over 550,148 students across the U.S. took the AP English Language and Composition Exam, and 65.2% scored higher than a 3. The AP English Language Exam tests your ability to analyze a piece of writing, synthesize information, write a rhetorical essay, and create a cohesive argument. In this post, we’ll be discussing the best way to approach the argumentative essay section of the test, and we’ll give you tips and tricks so you can write a great essay.

The AP English Language Exam as of 2023 is structured as follows:

Section 1: 45 multiple choice questions to be completed in an hour. This portion counts for 45% of your score. This section requires students to analyze a piece of literature. The questions ask about its content and/or what could be edited within the passage.

Section 2: Three free response questions to be completed in the remaining two hours and 15 minutes. This section counts for 55% of your score. These essay questions include the synthesis essay, the rhetorical essay, and the argumentative essay.

- Synthesis essay: Read 6-7 sources and create an argument using at least three of the sources.

- Rhetorical analysis essay: Describe how a piece of writing evokes meaning and symbolism.

- Argumentative essay: Pick a side of a debate and create an argument based on evidence. In this essay, you should develop a logical argument in support of or against the given statement and provide ample evidence that supports your conclusion. Typically, a five paragraph format is great for this type of writing. This essay is scored holistically from 1 to 9 points.

Do you want more information on the structure of the full exam? Take a look at our in-depth overview of the AP Language and Composition Exam .

Although the AP Language Argument may seem daunting at first, once you understand how the essay should be structured, it will be a lot easier to create cohesive arguments.

Below are some tips to help you as you write the essay.

1. Organize your essay before writing

Instead of jumping right into your essay, plan out what you will say beforehand. It’s easiest to make a list of your arguments and write out what facts or evidence you will use to support each argument. In your outline, you can determine the best order for your arguments, especially if they build on each other or are chronological. Having a well-organized essay is crucial for success.

2. Pick one side of the argument, but acknowledge the other side

When you write the essay, it’s best if you pick one side of the debate and stick with it for the entire essay. All your evidence should be in support of that one side. However, in your introductory paragraph, as you introduce the debate, be sure to mention any merit the arguments of the other side has. This can make the essay a bit more nuanced and show that you did consider both sides before determining which one was better. Often, acknowledging another viewpoint then refuting it can make your essay stronger.

3. Provide evidence to support your claims

The AP readers will be looking for examples and evidence to support your argument. This doesn’t mean that you need to memorize a bunch of random facts before the exam. This just means that you should be able to provide concrete examples in support of your argument.

For example, if the essay topic is about whether the role of the media in society has been detrimental or not, and you argue that it has been, you may talk about the phenomenon of “fake news” during the 2016 presidential election.

AP readers are not looking for perfect examples, but they are looking to see if you can provide enough evidence to back your claim and make it easily understood.

4. Create a strong thesis statement

The thesis statement will set up your entire essay, so it’s important that it is focused and specific, and that it allows for the reader to understand your body paragraphs. Make sure your thesis statement is the very last sentence of your introductory paragraph. In this sentence, list out the key points you will be making in the essay in the same order that you will be writing them. Each new point you mention in your thesis should start a paragraph in your essay.

Below is a prompt and sample student essay from the May 2019 exam . We’ll look at what the student did well in their writing and where they could improve.

Prompt: “The term “overrated” is often used to diminish concepts, places, roles, etc. that the speaker believes do not deserve the prestige they commonly enjoy; for example, many writers have argued that success is overrated, a character in a novel by Anthony Burgess famously describes Rome as a “vastly overrated city,” and Queen Rania of Jordan herself has asserted that “[b]eing queen is overrated.”

Select a concept, place, role, etc. to which you believe that the term “overrated” should be applied. Then, write a well-developed essay in which you explain your judgment. Use appropriate evidence from your reading, experience, or observations to support your argument.

Sample Student Essay #1:

[1] Competition is “overrated.” The notion of motivation between peers has evolved into a source of unnecessary stress and even lack of morals. Whether it be in an academic environment or in the industry, this new idea of competition is harmful to those competing and those around them.

[2] Back in elementary school, competition was rather friendly. It could have been who could do the most pushups or who could get the most imaginary points in a classroom for a prize. If you couldn’t do the most pushups or win that smelly sticker, you would go home and improve yourself – there would be no strong feelings towards anyone, you would just focus on making yourself a better version of yourself. Then as high school rolled around, suddenly applying for college doesn’t seem so far away –GPA seems to be that one stat that defines you – extracurriculars seem to shape you – test scores seem to categorize you. Sleepless nights, studying for the next day’s exam, seem to become more and more frequent. Floating duck syndrome seems to surround you (FDS is where a competitive student pretends to not work hard but is furiously studying beneath the surface just like how a duck furiously kicks to stay afloat). All of your competitors appear to hope you fail – but in the end what do you and your competitor’s gain? Getting one extra point on the test? Does that self-satisfaction compensate for the tremendous amounts of acquired stress? This new type of “competition” is overrated – it serves nothing except a never-ending source of anxiety and seeks to weaken friendships and solidarity as a whole in the school setting.

[3] A similar idea of “competition” can be applied to business. On the most fundamental level, competition serves to be a beneficial regulator of prices and business models for both the business themselves and consumers. However, as businesses grew increasingly greedy and desperate, companies resorted to immoral tactics that only hurt their reputations and consumers as a whole. Whether it be McDonald’s coupons that force you to buy more food or tech companies like Apple intentionally slowing down your iPhone after 3 years to force you to upgrade to the newest device, consumers suffer and in turn speak down upon these companies. Similar to the evolved form of competition in school, this overrated form causes pain for all parties and has since diverged from the encouraging nature that the principle of competition was “founded” on.

The AP score for this essay was a 4/6, meaning that it captured the main purpose of the essay but there were still substantial parts missing. In this essay, the writer did a good job organizing the sections and making sure that their writing was in order according to the thesis statement. The essay first discusses how competition is harmful in elementary school and then discusses this topic in the context of business. This follows the chronological order of somebody’s life and flows nicely.

The arguments in this essay are problematic, as they do not provide enough examples of how exactly competition is overrated. The essay discusses the context in which competition is overrated but does not go far enough in explaining how this connects to the prompt.

In the first example, school stress is used to explain how competition manifests. This is a good starting point, but it does not talk about why competition is overrated; it simply mentions that competition can be unhealthy. The last sentence of that paragraph is the main point of the argument and should be expanded to discuss how the anxiety of school is overrated later on in life.

In the second example, the writer discusses how competition can lead to harmful business practices, but again, this doesn’t reflect the reason this would be overrated. Is competition really overrated because Apple and McDonald’s force you to buy new products? This example could’ve been taken one step farther. Instead of explaining why business structures—such as monopolies—harm competition, the author should discuss how those particular structures are overrated.

Additionally, the examples the writer used lack detail. A stronger essay would’ve provided more in-depth examples. This essay seemed to mention examples only in passing without using them to defend the argument.

It should also be noted that the structure of the essay is incomplete. The introduction only has a thesis statement and no additional context. Also, there is no conclusion paragraph that sums up the essay. These missing components result in a 4/6.

Now let’s go through the prompt for a sample essay from the May 2022 exam . The prompt is as follows:

Colin Powell, a four-star general and former United States Secretary of State, wrote in his 1995 autobiography: “[W]e do not have the luxury of collecting information indefinitely. At some point, before we can have every possible fact in hand, we have to decide. The key is not to make quick decisions, but to make timely decisions.”

Write an essay that argues your position on the extent to which Powell’s claim about making decisions is valid.

In your response you should do the following:

- Respond to the prompt with a thesis that presents a defensible position.

- Provide evidence to support your line of reasoning.

- Explain how the evidence supports your line of reasoning.

- Use appropriate grammar and punctuation in communicating your argument.

Sample Student Essay #2:

Colin Powell, who was a four star general and a former United States Secretary of State. He wrote an autobiography and had made a claim about making decisions. In my personal opinion, Powell’s claim is true to full extent and shows an extremely valuable piece of advice that we do not consider when we make decisions.