- Schools & departments

Case Study: supporting a visually impaired student

Case study highlighting the support that can be implemented for a visually impaired student

Fiona is a new international postgraduate student who commenced her undergraduate studies in the College of Science and Engineering at the University in September. Having obtained exceptional grades at school, Fiona was able to gain admission as a direct entrant into the second year of her BSc degree.

Fiona has a number of eye conditions which result in her having extremely limited vision in both eyes. She made contact with the Student Disability Service at the beginning of her first semester, and it was clear that, in addition to the provision of a range of support/adjustments, Fiona would also benefit from the provision of assistive technology in order to enable her to be able to access all elements of her studies.

Although the advisory staff within the Disability and Learning Support Service are skilled and trained in the use and application of a very broad range of assistive technology and software, there are occasions when even more specialist knowledge and expertise are required. Consequently, the Service worked with the Royal National Institute for Blind People (RNIB), and referred Fiona to them for a detailed assessment of need. This also allowed her to trial equipment which the Service did not have available.

As a non-UK student, Fiona was not eligible for state funding for any support requirements through Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA). Therefore, any recommendations for equipment, software or technology that arose from her RNIB assessment would be funded through the allocation that the University makes available in the form of the Disabled Students Support Fund (DSSF).

Fiona met with RNIB staff in October and they were able to let her try out a range of equipment which had practical benefits for her studies. On the basis of her feedback on ease of use and application in the academic context, the Service agreed to purchase a number of items, using finance from the DSSF, up to a total cost of £2,000. These included a digital voice recorder to record lectures, a laptop with Windows and MS Office and a ZoomText magnifier, optical magnifier and monocular telescope. This equipment enables the student to enlarge and adjust text size and utilise text to speech functions, which also minimise the need for human support and enables the student to maximise her capacity for independent learning.

Fiona has settled into her studies and is making effective use of the equipment, which she will be able to utilise for the duration of her studies. On completion of her degree, much of the equipment will be returned to Disability and Learning Support Service so that it may be used by other students in future.

Emerging Technologies for Blind and Visually Impaired Learners: A Case Study

- First Online: 31 May 2023

Cite this chapter

- Regina Kaplan-Rakowski 9 &

- Tania Heap 9

Part of the book series: Educational Communications and Technology: Issues and Innovations ((ECTII))

214 Accesses

Blind and visually impaired (BVI) people frequently encounter challenges in their daily lives. With the COVID-19 pandemic, some of those challenges decreased, but some became more evident. The goal of this chapter is two-fold. First, we present the findings of a qualitative case study of a blind student sharing reflections of his daily barriers with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, his success strategies, and his impressions of using emerging technologies. Second, we discuss guidelines on using traditional and innovative technologies to assist BVI individuals. The chapter has practical implications not only for the BVI population but also for all students, applying principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and illustrating the responsibility of stakeholders for inclusive policies on the implementation of assistive technologies and accessible learning experiences.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Throughout this chapter, the authors will use both person-first language, which places the person before their characteristic (e.g., people with disabilities) and identity-first language, which leads with the person’s characteristic (e.g., blind user). There are pros and cons to using either approach, but when the opportunity presents, a good practice is to ask each individual which language they prefer.

Aisami, R. S. (2015). Learning styles and visual literacy for learning and performance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 176 , 538–545.

Article Google Scholar

Alobaid, A. (2021). ICT multimedia learning affordances: Role and impact on ESL learners' writing accuracy development. Heliyon, 7 (7), e07517.

An, Y., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Yang, J., Conan, J., Kinard, W., & Daughrity, L. (2021). Examining K-12 teachers’ feelings, experiences, and perspectives regarding online teaching during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69 (2), 2589–2613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10008-5

Bartolic, S., Matzat, U., Tai, J., Burgess, J. L., Boud, D., Craig, H., Archibald, A., De Jaeger, A., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Lutze-Mann, L., Polly, P., Roth, M., Heap, T., Agapito, J., & Guppy, N. (2022). Student vulnerabilities and confidence in learning in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies in Higher Education, 47 , 1–13.

Baumgartner, E., Hartshorne, R., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Mouza, C., & Ferdig, R. E. (Eds.). (2022). A Retrospective of teaching, technology, and teacher education during the COVID-19 pandemic . Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Google Scholar

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 , 77–101.

Brown, S. E. (2008). Breaking barriers: The pioneering disability students services program at the University of Illinois, 1948–1960. In The history of discrimination in US education (pp. 165–192). Palgrave Macmillan.

Buetow, S. (2010). Thematic analysis and its reconceptualization as saliency analysis. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 15 (2), 123–125.

Burgstahler, S. (2020). Creating inclusive learning opportunities in higher education: A universal design toolkit (pp. 47–48). Harvard Education Press.

Burgstahler, S., & Crawford, L. (2020). The development of accessibility recommendations for online learning researchers. In S. Burgstahler (Ed.), Universal design in higher education: Promising practices . DO-IT, University of Washington. Retrieved from: www.uw.edu/doit/UDHE-promisingpractices/preface.html

Caldwell, B., Cooper, M., Reid, L. G., Vanderheiden, G., Chisholm, W., Slatin, J., & White, J. (2008). Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. WWW Consortium (W3C), 290, 1–34.

CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2 . Retrieved from: http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Crossland, M. D., Starke, S. D., Wolffsohn, J. S., & Webster, A. R. (2019). Benefit of an electronic head-mounted low vision aid. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics, 39 (6), 422–431.

Crutchfield, B., & Haugh, J. (2018). Accessibility in the virtual/augmented reality space. CSUN 2018 Assistive Technology Conference, San Diego, CA, March 22.

Enoch, J., McDonald, L., Jones, L., Jones, P. R., & Crabb, D. P. (2019). Evaluating whether sight is the most valued sense. JAMA Ophthalmology, 137 (11), 1317–1320.

Ferdig, R. E., Baumgartner, E., Hartshorne, R., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., & Mouza, C. (2020). Teaching, technology, and teacher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Stories from the field . Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved from: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/216903/

Ferdig, R. E., Baumgartner, E., Mouza, C., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., & Hartshorne, R. (2021). Editorial: Rapid publishing in a time of COVID-19: How a pandemic might change our academic writing practices. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 21 (1).

Hartshorne, R., Baumgartner, E., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Mouza, C., & Ferdig, R. E. (2020). Special issue editorial: Preservice and inservice professional development during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28 (2), 137–147. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216910/

Huber, E., Chang, K., Alvarez, I., Hundle, A., Bridge, H., & Fine, I. (2019). Early blindness shapes cortical representations of auditory frequency within auditory cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 39 (26), 5143–5152.

Kaplan-Rakowski, R. (2021). Addressing students’ emotional needs during the COVID-19 pandemic: A perspective on text versus video feedback in online environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69 (1), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09897-9

Kent, M., Ellis, K., Latter, N., & Peaty, G. (2018). The case for captioned lectures in Australian higher education. TechTrends, 62 (2), 158–165.

King, A. J. (2014). What happens to your hearing if you are born blind? Brain, 137 (1), 6–8.

Kriemeier, J., & Götzelmann, T. (2020). Two decades of touchable and walkable virtual reality for blind and visually impaired people: A high-level taxonomy. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 4 (4), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4040079

Kuri, N. P., & Truzzi, O. M. S. (2002). Learning styles of freshmen engineering students. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Education (ICEE 2002).

Lavrakas, P. J. (2008). Encyclopedia of survey research methods . Sage Publications.

Book Google Scholar

Lee, D., & Cho, J. (2022). Automatic object detection algorithm-based braille image generation system for the recognition of real-life obstacles for visually impaired people. Sensors (Basel), 22 (4), 1601, 1–22. Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22041601

Longhurst, G. J. (2021). Teaching a blind student anatomy during the Covid-19 pandemic. Anatomical Sciences Education, 14 (5), 586–589.

Lueders, K., Perla, F., Maffit, J., Vasile, E., Jay, N., Kaplan, J., & Hanuschock, W. E., III. (2020). Remote instruction for students who are blind or visually impaired: Experiences of preservice interns. In R. E. Ferdig, E. Baumgartner, R. Hartshorne, R. Kaplan-Rakowski, & C. Mouza (Eds.), Teaching, technology, and teacher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Stories from the field . Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

McBride, C. R. (2020). Critical issues in education for students with visual impairments: Access to mathematics and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] University of Georgia.

McDonnall, M. C., & Sui, Z. (2019). Employment and unemployment rates of people who are blind or visually impaired: Estimates from multiple sources. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 113 (6), 481–492.

Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E. (2010). Reflexivity. Encyclopediaof case study research. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412957397

Morgan, H. (2022). Alleviating the challenges with remote learning during a pandemic. Education Sciences, 12 (2), 109, 1–12, Retrieved from:. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020109

Mouza, C., Hartshorne, R., Baumgartner, E., & Kaplan-Rakowski, R. (2022). Special issue editorial: A 2025 vision for technology and teacher education. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 30 (2), 107–115.

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual-coding approach . Oxford University Press.

Rodríguez, A., Boada, I., & Sbert, M. (2018). An Arduino-based device for visually impaired people to play videogames. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 77 (15), 19591.

Rose, D. (2000). Universal design for learning. Journal of Special Education Technology, 15 (3), 45–49.

Russ, S., & Hamidi, F. (2021, April). Online learning accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Proceedings of the 18th International Web for All Conference (pp. 1–7).

Siu, A. F., Sinclair, M., Kovacs, R., Ofek, E., Holz, C., & Cutrell, E. (2020). Virtual reality without vision: A haptic and auditory white cane to navigate complex virtual worlds. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, April 25–30 .

Sooraj, V. S., Magadum, H. J., & Alluri, L. (2021, December). iTouch–blind assistance smart glove. In 2021 10th International Conference on System Modeling & Advancement in Research Trends (SMART) (pp. 172–175). IEEE.

Tellis, W. (1997). Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report, 3 (2).

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Persons with a disability: Labor force characteristics summary . Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/2Rt9rgm

WHO. (n.d.). Assistive technology . World Health Organization : Health Topics. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/assistive-technology#tab=tab_1

Zhao, Y., Bennett, C. L., Benko, H., Cutrell, E., Holz, C., Morris, M. R., & Sinclair, M. (2018, April). Enabling people with visual impairments to navigate virtual reality with a haptic and auditory cane simulation. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–14).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

Regina Kaplan-Rakowski & Tania Heap

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Regina Kaplan-Rakowski .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Deborah Cockerham

Regina Kaplan-Rakowski

Wellesley Foshay

Michael J. Spector

Interview Questions to Jarrod

Online learning

What aspects of online learning work well for you?

What aspects of online learning do not work well for you?

How did the shift to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic impacted you?

How did the shift to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic impacted your community?

What support did you receive?

What support did you wish you had received?

How has the shift to online learning due to COVID-19 informed your opinion about the future of digital accessibility?

What does not work well for you? How accurate is dictation? Do you feel it is improving?

What can be done differently or better?

What technologies have you been using that are helpful to you?

What innovative technologies are you aware of that you think could be helpful to you?

What about screen readers?

What about smart speakers?

As an assistive technology user and an experienced gamer, what advice do you have for game designers and professors using gaming in their courses?

An additional question:

How much understanding of your situation do you think the sighted people have?

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Heap, T. (2023). Emerging Technologies for Blind and Visually Impaired Learners: A Case Study. In: Cockerham, D., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Foshay, W., Spector, M.J. (eds) Reimagining Education: Studies and Stories for Effective Learning in an Evolving Digital Environment. Educational Communications and Technology: Issues and Innovations. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25102-3_16

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25102-3_16

Published : 31 May 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-25101-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-25102-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 12 November 2015

Visual impairment, coping strategies and impact on daily life: a qualitative study among working-age UK ex-service personnel

- Sharon A. M. Stevelink 1 ,

- Estelle M. Malcolm 1 &

- Nicola T. Fear 1 , 2

BMC Public Health volume 15 , Article number: 1118 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

26 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Sustaining a visual impairment may have a substantial impact on various life domains such as work, interpersonal relations, mobility and social and mental well-being. How to adjust to the loss of vision and its consequences might be a challenge for the visually impaired person. The purpose of the current study was to explore how younger male ex-Service personnel cope with becoming visually impaired and how this affects their daily life.

Semi-structured interviews with 30 visually impaired male ex-Service personnel, all under the age of 55, were conducted. All participants are members of the charity organisation Blind Veterans UK. Interviews were analysed thematically.

Younger ex-Service personnel applied a number of different strategies to overcome their loss of vision and its associated consequences. Coping strategies varied from learning new skills, goal setting, integrating the use of low vision aids in their daily routine, to social withdrawal and substance misuse. Vision loss affected on all aspects of daily life and ex-Service personnel experienced an on-going struggle to accept and adjust to becoming visually impaired.

Conclusions

Health care professionals, family and friends of the person with the visual impairment need to be aware that coping with a visual impairment is a continuous struggle; even after a considerable amount of time has passed, needs for emotional, social, practical and physical support may still be present.

Peer Review reports

Becoming visually impaired can be a life changing experience and is likely to have far reaching consequences for the person affected [ 1 – 3 ]. Persons acquiring a visual impairment express a variety of emotional, cognitive, behavioural and social responses to this significant loss. The model of grief proposed by Kübler-Ross, originally used to describe coping in terminally ill persons, has shown to be useful in a variety of settings in which persons face a significant crisis, change or loss, such as acquiring a visual impairment [ 4 , 5 ]. People affected will mourn their loss of vision and associated losses including their job, leisure activities and independence and may go through various phases of grief, which include denial, anger, depression, bargaining and acceptance [ 6 ]. Positive or negative mechanisms of adjustment, also termed coping strategies, can help individuals to master their impairment. Broadly speaking, we can distinguish between adaptive coping strategies such as seeing a counsellor and goal setting or maladaptive coping strategies including social withdrawal and substance misuse [ 7 , 8 ].

Service personnel are at a higher risk of becoming visually impaired than civilians as a result of deployment experiences. A decrease in combat-related mortality has been reported during the recent deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan compared to other conflicts; this can be explained by technological and medical advances in medical care, body armour and casualty evacuation [ 9 ]. However, more Service personnel return home with combat-related trauma such as shrapnel wounds, extremity amputations, head injury and vision loss [ 9 – 12 ].

Recently, a study reviewing the prevalence of mental health problems among (ex-) service personnel with an irreversible impairment (e.g. hearing, vision, but predominantly physical) concluded that common mental health disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, psychological distress and depression, were frequently reported, but levels varied widely across study populations. Nevertheless these levels appeared to be higher than found in comparable samples of civilian and military populations without an impairment [ 13 ].

This study utilised a sample of younger (ex-) Service personnel who are members of Blind Veterans UK (55 years of age or below). Blind Veterans UK is a charity organisation, formerly known as St Dunstan’s, which provides support and care for (ex-) Service personnel who have a visual impairment in both eyes, regardless of the cause. The majority of the members of Blind Veterans UK are 65 years and older, however, due to military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, the charity has seen an influx in younger members over the last decade. Therefore Blind Veterans UK commissioned the King’s Centre for Military Health Research at King’s College London to examine the mental health and social well-being of their younger members. We explored how ex-Service men adjust to their loss of vision, which coping strategies they use and how their loss of vision and its consequences has impacted on their daily life.

Setting and design

A cross-sectional study was conducted using a mixed methods approach. Phase 1 of the study consisted of telephone interviews with male and female (ex-) Service personnel whereby clinical screening measures for mental health were used. A subsample of the phase 1 participants was invited to join phase 2 of the study. Phase 2 consisted of semi-structured in-depth face to face interviews, covering various topics including the impact of becoming visually impaired on various domains of life and coping strategies. The current paper will report on male participants included in phase 2 of the study.

Participants

All participants were members of Blind Veterans UK and were under 55 years of age at recruitment. Male participants who took part in phase 1 of this study ( n = 74) were asked if they would be interested in taking part in a qualitative interview. Sixty-six participants indicated their willingness to do the face-to-face interview. We were especially interested in those who became visually impaired due to their deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan ( n = 10). They were prioritised in the selection process for phase 2 after which other participants were invited. Thirty male ex-Service personnel were approached and two declined. Therefore, an additional two male members were invited and they agreed to participate. We deemed 30 face-to-face interviews sufficient to reach data saturation based on previous experiences and the literature [ 14 ]. The data collection period was closely monitored to ensure that the data collected was rich and descriptive and no new information seemed to emerge whilst approaching the set interview target.

A semi-structured interview schedule was used consisting of 11 open-ended questions covering different aspects of how a visual impairment can have an impact on life, difficulties experienced because of being visually impaired and how ex-Service men adjusted to life with a visual impairment (Additional file 1 ). These questions were developed in collaboration with Blind Veterans UK, to ensure they met the remit of the work commissioned and were appropriate for use in the target population. The draft interview guide was piloted by E.M.M. and S.A.M.S. among two members of Blind who just exceeded the age threshold off 55 years. Feedback from the participants suggested that the questions were received well, easy to follow and comprehensive. Therefore no changes were made to the interview guide. Socio-demographic data obtained during phase 1 were linked to the participants who were included in phase 2 of the study.

Interviews took place between December 2012 and May 2013. Prior to the interview, participants received an information package explaining the study and a detailed signposting booklet (in accessible formats) providing information about various sources of help and advice that might be useful for the participant, such as the Veterans UK helpline.

Participants were interviewed by two researchers (E.M.M. and S.A.M.S.) who were trained and experienced in using the qualitative interview schedule. The majority of the interviews took place in the participant’s home environment after verbal informed consent was given. Procedures were in place for participants who were distressed or at risk and required a call back from a Community Psychiatric Nurse. All interviews were recorded with a Dictaphone. Interviews lasted 35–105 min. At the end of the interview participants were thanked for their time and received £20 in cash.

The interviews were transcribed in full to include all spoken words and non-verbal utterances such as sighs and laughter. Recordings were listened to and transcripts were read and re-read by E.M.M. and S.A.M.S. Both independently coded five different transcripts each using NVivo as an organisational tool. Once five transcripts were independently coded, E.M.M. and S.A.M.S. met to compare and discuss. The initial coding framework was grounded in the content of the data (inductive). Data were analysed thematically [ 15 ]. Throughout the first stages of the analysis process the coding framework was revised and further developed. E.M.M. and S.A.M.S. independently read and coded three additional transcripts to ensure the coding framework reflected the data. Any disagreement about codes between the two researchers were discussed and resolved. Once the coding frame was finalised, E.M.M. independently coded all of the transcripts (Additional file 2 ). Intra-coder agreement was established by E.M.M. by coding three interviews at two time points which were one month apart. An intra-coder agreement of 84.5 % was found, indicating good agreement. Once all transcripts were coded, the codes were put into broader themes and associated sub-themes. The main themes identified for the current paper were coping (strategies) and the impact of vision loss on daily life. Pseudonyms are used when presenting the data.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Social Care Research Ethics Committee (12-IEC08-0032).

Out of the 30 younger ex-Service men, 27 were below 45 years of age; 15 were employed at the time of the interview; four were still serving but were waiting to be medically discharged. Of those who had left the Armed Forces, 13 out of 30 had left over 10 years ago and just over half (17 out of 30) were married or in a long term relationship. The great majority (26 out of 30) had served in the Army.

Twelve men had a combat-related visual impairment, of which 10 sustained the impairment during deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. 12 out of the 30 sustained their impairment less than 5 years ago. Genetic causes of visual impairment were the most common causes of visual impairment ( n = 7) among those with a non-combat-related visual impairment followed by ocular medical conditions (e.g. age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma) ( n = 4) and environmental causes ( n = 4) (e.g. toxic or injury related). The overwhelming majority of ex-Service personnel used low vision aids (28 out of 30); four had a guide dog, 17 used talking books and 19 used a white stick. Approximately one in three participants screened positive for probable depression, probable anxiety or probable Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Stevelink et al., (2015) http://bjo.bmj.com/content/early/2015/04/23/bjophthalmol-2014-305986.full .

In the next section the findings of the two themes identified for the current paper, specifically ‘coping (strategies)’ and ‘impact of vision loss on daily life’, are combined to describe how vision loss affected the person from the time directly after becoming visually impaired and how this changed subsequently.

Coping with a visual impairment and impact on daily life

Directly after becoming visually impaired, younger male ex-Service personnel thought “life is over” and they “ [didn’t] want to carry on” . Their confidence was undermined, they felt sorry for themselves and had the feeling there was no way out.

Phil (non-combat-related visual impairment, age 35–44 years) : “Well initially straightaway it [loss of vision] stopped me from going out straightaway. I went in for the first two years, first year and a half at least, I was very depressed. Very sorry for myself and thought that was it (…). (…) I didn’t think there was anything I could do so yeah, dread, full of dread and fear and all that lot did come into it.”

These feelings and experiences were reinforced by other losses that were experienced as a result of their loss of vision such as losing their job, experiencing relationship difficulties and an increased dependence on others.

In most cases, if personnel suffered a deterioration of their sight whilst in Service, they were medically discharged and as a result had to confront the issue of changing their career. This was similar amongst those who had left the Service and had started a civilian job. This forced change of career was generally experienced as a “regression” leading into a cascade of accompanying consequences such as experiencing financial hardship if living on benefits, different family dynamics due to for example family members taking on the role of carer and, above all, impaired self-esteem. Ex-Service men felt that by no longer being the breadwinner in the household and a highly trained professional, they were set back to square one as said by Alan (combat-related visual impairment, age 25–34 years):

“(…) it’s like all that experience, all that knowledge… shoved right back in your face (…). (…) You’re a broken toy now. What happens to broken toys… goes to the tip doesn’t it? (…). You know you’re a broken toy they don’t want to know you.”

Denial of the consequences of vision loss resulted in ex-Service men trying to do the things they were used to do; this resulted in feelings of frustration and irritation as illustrated by Richard (non-combat-related visual impairment, age 45–54 years):

“(…) at first it [loss of vision] made me really down and depressed and … . Because I’d known for quite a while before that there was something wrong. And I went through not accepting it. So at first I wouldn’t accept it and then when I first finished work obviously I had to walk everywhere. I got quite narky with people. If I was out with my stick and they’d bump into me. I’d get quite angry with them… because it was everybody else’s fault for getting in my way. So I went through like a stage of denial, I suppose and then being angry.”

The emotional turmoil personnel went through whilst adjusting, adversely affected their relationship with their partner. Those who were in a relationship at the time of becoming visually impaired suggested that their impairment put a strain on that relationship. Personnel experienced increased dependence on their partner resulting in changing relationship dynamics. Both the partner and the person affected needed time to adapt to this new situation. In a few cases, participants divorced or ended their relationship with their partner, but the dominant view was that the impairment was a contributing factor but not the main reason for breaking up.

Charlie (non-combat-related visual impairment, age 35–44 years): “ But it [loss of vision] very nearly I think cost us my wife and I our marriage, because I was quite unpleasant on more than one occasion. But thankfully we’re coming through the other side so yeah it’s been a difficult journey.”

Members who became visually impaired in combat were proud about the circumstances that led to their loss of vision ( “serving Queen and Country” ), whereas those with a non-combat-related visual impairment struggled with the question ‘why me?’ and even felt guilty, ashamed or embarrassed. Some personnel expressed the hope that their vision would improve over time or were looking into potential treatment options. Personnel were mourning about what they had lost and what they could have done if they had not sustained a visual impairment.

Harry (combat-related visual impairment, 35–44 years): “You know the doctors are going to say to you at some point you don’t need to come and see us anymore, and that’s when it will sink in and that’s what you’ve got for the rest of your life, that’s what you’re stuck with. And at that point you need to just accept it, just get on with it because the longer you kid yourself it’s going to get better, or there’s going to be some miracle surgery, the longer it ‘ll take you to adapt.”

The visual impairment not only affected the domain of work and interpersonal relationships but also other areas as illustrated by Nick (non-combat related, age 25–34 years):

“ (…) you do have a bad impact on your day to day life especially from washing up to having food or to prepare a meal. Then taking medication and also you know dress yourself, and also you can’t actually go out on your own all the time. So your movement is quite restricted although it can be done with some training outside, but there is the danger off (…) colliding with something or someone or some obstruction.”

As time passed, ex-Service personnel were able to “ change [their] head around ” and tried to adjust to their visual impairment and its consequences, by applying various coping strategies. The ‘military ethos’ of “crack on” and “adapt and overcome the situation” helped them to overcome any problems they experienced. However, for some personnel it acted as a barrier because they were reluctant to ask for help and struggled through with their visual impairment (defined by the researchers as coping at a cost).

Other reasons for coping at a cost were that younger ex-Service personnel felt ashamed, lacked confidence or were too proud to ask for help. They did not want to be seen as a burden on others. Coping at a cost was enforced by reactions from the public. For example, Max (non-combat-related visual impairment, 35–44 years) was assaulted when using his cane on public transport after accidently bumping into someone; they did not believe he was visually impaired so from that moment on he decided not to use a cane anymore.

The unavailability of support and resources influenced how younger members coped with their loss. Ex-Service personnel tried ‘to escape’ by, for example, substance abuse or made a non-fatal suicide attempt.

Tom (non-combat-related visual impairment, 25–34 years): “ When I first lost my eyesight I never had that emotional support. I never had it and I dealt with it on my own. My way was hitting the drinks and hitting the drugs and going crazy .”

Other examples of maladaptive behaviour included isolation and social withdrawal from family and friends, acting aggressively or in an unfriendly manner.

Besides the use of maladaptive coping strategies, several adaptive coping strategies were applied. One of these was termed by the researchers as ‘downward comparison’. Younger ex-Service personnel pointed out that they were aware of other people being worse off than themselves such as soldiers with serious brain injury, cancer patients or if they still had some vision left those who were completely blind. Others made a comparison with vision impaired members who managed to carry on successfully. By making a downward comparison or by comparing themselves with people who had faced the same problems, coping was facilitated as members got inspired and motivated to “crack on with life”.

Oliver (non-combat-related visual impairment, 35–44 years): “They [members of Blind Veterans UK] proved that there are other people in the same situation as me and even not worse, and that you know you can still do day to day tasks and you can still do a lot of varied things if you put your mind to it. You know and it’s just challenging your mind to being able to do these things.”

People’s favourite leisure activities and interests changed substantially because they were no longer able to undertake them due to their loss of vision. Driving a car was missed tremendously, followed by sporting activities and reading. Personnel tried to get around these barriers by adopting a problem-focused approach (e.g. use of low vision aids, retrain, find other activities they were able to do). Also accepting or asking for (social) support from family, friends, charities or seeking professional support, helped ex-Service personnel to adjust and carry on.

Just after becoming visually impaired, personnel needed a lot of help and relied heavily on others. Once they started to adapt, people learned new skills and strategies, resulting in increased confidence and less reliance on others. This had a positive impact on the mental well-being of the person with the visual impairment and facilitated the process of accepting their loss of vision and its consequences. Further personnel learned what they are still able to do and what not, thereby reflecting on and adapting to the restrictions their visual impairment imposed. However, the dependence on others played a limiting role and new activities such as taking up different hobbies like disability sports were not always experienced as that satisfying.

Andrew (combat-related visual impairment, 25–34 years): “You have to accept that sort of thing as part of the hard bit in the beginning. (…) once you’ve accepted it [loss of vision] you get used to it and just move on from then. Then obviously you have achievement from there and then you put yourself to whatever you need to achieve.”

Achievement was often mentioned as a next step. Younger ex-Service personnel decided to set a particular goal such as starting a new course or degree, or signed up for a sporting challenge. By working towards a particular goal, personnel got back in a daily routine, their confidence increased as well as their self-worth. This impacted positively on their mental well-being. Reflecting on the different experiences of the participants it becomes apparent that coping with loss of vision is a dynamic long-term process. Even after years, people may struggle as new situations, challenges or life events come by.

Jack (combat-related visual impairment, 25–34 years): “It’s been [amount of years] now and there was a time I thought I’d accepted what had happened to me, but you know that was temporary. And yeah I don’t think I’ve fully accepted what’s happened to me. There [are] good periods and bad periods and you know they come and go quite randomly and yeah they affect me for different amounts of time and I can get quite negative sometimes and quite self-deprecating.”

Younger ex-Service men suggested that becoming visually impaired had turned their life upside down; the accompanying consequences had adverse effects on a variety of life domains and adjusting was experienced as a tough journey. Personnel struggled with an increased level of dependence on others, a loss of freedom, a lack of confidence and impaired feelings of self-worth. Various coping strategies were applied by younger ex-Service men and these enabled them to adjust to their loss and overcome challenges they faced down the line. Coping was an on-going and dynamic process with ex-Service personnel experiencing good and bad times, even after many years since sustaining their impairment.

The Kübler-Ross model was initially developed to describe how people cope with death and dying following a distinct 5 stage model (denial, anger, depression, bargaining and acceptance) [ 6 ]. We used this model as an example in the introduction to describe how people may deal with facing a significant loss, such as sustaining a visual impairment. However, over the years this model has been critiqued widely [ 16 – 18 ].

When reflecting on our results, it became clear that ex-Service men experienced a far wider range of emotions and behaviours; in some cases these emotions occurred simultaneously. Instead of a stage like pattern of response, the data showed coping was more dynamic, highly interactive and a unique journey for every individual. Whereas the individual affected plays a central role in Kübler-Ross’ model, we found that other factors played an important role as well as to how people adjust, including the availability of social support, use of low vision aids, presence of public attitudes, family composition and other situational factors [ 19 ]. The variety of positive or negative mechanisms of adjustment helped the individual to master their impairment and should be referred to as forms of coping strategies [ 18 ]. Acceptance is described as the closing stage of the grief process by Kübler-Ross. However, as pointed out by Murray and colleagues (2010), and reflected in our data, we found coping to be a long-term process, whereby the person affected will apply different strategies depending on the changes or new situations they encounter [ 20 ]. Therefore, acceptance may occur temporarily but will interact with new periods of adjustment and the grief process can be characterised as ‘a chronic recurrent but episodic process’ [ 20 ]. This has been illustrated earlier with a quote from Jack (combat-related visual impairment, 25–34 years): he interchangeably experiences periods of acceptance vs. rejection, despite the fact that a considerable amount of time has passed by since he became visually impaired.

Personnel tried to adjust using various strategies, including a strategy termed by the researchers as ‘coping at a cost’. Underlying reasons such as feeling too embarrassed to ask for help, not wanting to burden others or wanting to ‘crack on’ alone. Participants suggested that asking for help would impede on their sense of self-pride and self-respect [ 19 , 21 – 24 ]. This attitude of ‘cracking on’ is a key element of the work ethic of the British Army and encourages pro-activity over passivity and contemplation [ 25 ]. A different strategy was comparing themselves with others they classified as worse off [ 26 , 27 ]. This downward comparison motivated and inspired people to life their live to the fullest. For ex-Service personnel with a combat-related visually impairment, feelings of being grateful to still be around were apparent. Analysis of the quantitative data of the current study suggested that the prevalence of mental health problems was not substantially different between personnel with a combat-related visual impairment (25.0 %) compared to those with a non-combat-related visual impairment (29.6 %) (Ref).

Impact of visual impairment on life domains

Various quantitative studies have examined the impact of vision loss on the psychological well-being of elderly populations [ 3 ]. A review summarizing qualitative evidence of seventeen studies on the impact of and coping with vision loss suggested that people relied more heavily on others to perform their daily activities [ 7 ]. Further, they reported the loss of leisure activities and hobbies. In addition, a negative impact on mental well-being was described such as the onset of depression, impaired self-esteem, being less socially active and experiencing challenges with regards to interpersonal relationships and communication [ 7 ]. Despite the review summarizing studies among the elderly, the findings correspond well with those from the current study. However, the researchers would like to highlight that while the actual barriers and changes due to the loss of vision and its related consequences may be unique for each person, they impede on the same highly valued core concepts of (in) dependence, autonomy, self-esteem, control, confidence, freedom and identity.

A different review synthesised the findings of quantitative studies about the psychosocial impact of vison loss in adults aged 18–59 years [ 2 ]. They concluded that the general mental health, social functioning and quality of life were adversely affected. However, this was not consistent for the impact of visual impairment on the prevalence of depression [ 2 ]. The association between depression and visual impairment appears to be more evident among elderly [ 1 , 24 ].

Limitations

This study had various limitations. First, all participants were members of the charity organisation Blind Veterans UK and had served in the UK Armed Forces. In what way these findings can be extrapolated to different visually impaired populations such as civilians, elderly, women and people who are not involved in a charity organisation remains uncertain. Second, the research team asked sensitive questions related to how personnel coped with their visual impairment. They could have given socially acceptable answers because they did not feel confident, did not trust the interviewer or did not want to appear as ‘weak’. This issue was addressed by informing them what to expect, building good rapport and providing the opportunity to ask the team questions. An important strength of this qualitative study is the substantial sample size ( n = 30). Therefore, we are confident that we captured a wide range of views and experiences.

Implications

Clinicians, ophthalmologists and other health care providers as well as partners, the wider family and friends need to be aware that coping is an on-going process and that even after a considerable amount of time, needs for emotional, social, practical and physical support may still be present. Functional training and psychosocial support should be offered enabling personnel to regain their confidence, feelings of self-worth and independence.

Our findings suggest that sustaining a visual impairment is a life changing event that has important effects on various domains of life. Adjusting to loss of vision and its related consequences can be described as a long-term and difficult journey whereby ex-Service personnel apply various coping strategies to overcome the challenges they face later on in their lives. Future research should be directed into how positive coping can be facilitated and how factors such as the duration of the visual impairment and perceived social support, influence coping processes.

Horowitz A. The prevalence and consequences of vision impairment in later life. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2004;20(3):185–95.

Article Google Scholar

Nyman SR, Gosney MA, Victor CR. Psychosocial impact of visual impairment in working-age adults. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(11):1427–31.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pinquart M, Pfeiffer JP. Psychological well-being in visually impaired and unimpaired individuals: a meta-analysis. Br J Vis Impair. 2011;29(1):27–45.

Schilling OK, Wahl HW. Modeling late-life adaptation in affective well-being under a severe chronic health condition: the case of age-related macular degeneration. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(4):703–14.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bergeron CM, Wanet-Defalque M. Psychological adaptation to visual impairment: the traditional grief process revised. Br J Vis Impair. 2013;31(1):20–31.

Kübler-Ross E. On death & dying. New York: Scribner; 1969.

Google Scholar

Nyman SR, Dibb B, Victor CR, Gosney MA. Emotional well-being and adjustment to vision loss in later life: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(12):971–81.

Hodge S, Barr W, Bowen L, Leeven M, Knox P. Exploring the role of an emotional support and counselling service for people with visual impairments. Br J Vis Impair. 2013;31(1):5–19.

Fazal TM. Dead wrong? Battle deaths, military medicine and exaggerated reports of war’s demise. Int Secur. 2014;39(1):95–125.

Blood CG, Puyana JC, Pitlyk PJ, Hoyt DB, Bjerke HS, Fridman J, et al. An assessment of the potential for reducing future combat deaths through medical technologies and training. J Trauma. 2002;53(6):1160–5.

Eastridge BJ, Jenkins D, Flaherty S, Schiller H, Holcomb JB. Trauma system development in a theater of war: Experiences from operation Iraqi freedom and operation enduring freedom. J Trauma. 2006;61(6):1366–72. discussion 1372–1363.

Bellamy RF. A note on American combat mortality in Iraq. Mil Med. 2007;172(10):1023.

Stevelink SA, Malcolm EM, Mason C, Jenkins S, Sundin J, Fear NT. The prevalence of mental health disorders in (ex-)military personnel with a physical impairment: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2014;72:243–51.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fugard AJB, Potts HWW. Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: a quantitative tool. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2015;18(6):669–84.

Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNaughton Nicholls C, Ormston R. Qualitative Research Practice: a guide for social science students & researchers. 2nd ed. London: SAGE; 2014.

Brewer BW. Review and critque of models of psychological adjustment to athletic injury. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1994;6(1):87–100.

Copp G. A review of current theories of death and dying. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(2):382–90.

Corr CA. Coping with dying-lessons that we should and should not learn from the work of Kublerross, Elisabeth. Death Stud. 1993;17(1):69–83.

Weber JA, Wong KB. Older adults coping with vision loss. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2010;29(3):105–19.

Murray SA, McKay RC, Nieuwoudt JM. Grief and needs of adults with acquired visual impairments. Br J Vis Impair. 2010;28(2):78–89.

Wong EYH, Guymer RH, Hassell JB, Keeffe JE. The experience of age-related macular degeneration. J Vis Impair Blind. 2004;98(10):629–40.

Ivanoff SD, Sjostrand J, Klepp KI, Lind LA, Lindqvist BL. Planning a health education programme for the elderly visually impaired person—a focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 1996;18(10):515–22.

Brouwer DM, Gaynor S, Winding K, Hanneman M. Limitations in mobility: experiences of visually impaired older people. Br J Occup Ther. 2008;71(10):414–21.

Mitchell J, Bradley C. Quality of life in age-related macular degeneration: a review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:97.

King A. Why we’re getting it wrong in Afghanistan. In: Prospect. 2009.

Teitelman J, Copolillo A. Psychosocial issues in older adults’ adjustment to vision loss: findings from qualitative interviews and focus groups. Am J Occup Ther. 2005;59(4):409–17.

Thurston M, Thurston A, McLeod J. Socio-economic effects of the transition from sight to blindness. Br J Vis Impair. 2010;28(2):90–112.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Christopher Dandeker based at the Department of War Studies, King’s College London, for his useful comments on an earlier draft of the paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

King’s Centre for Military Health Research, King’s College London, Weston Education Centre, 10 Cutcombe Road, SE5 9RJ, London, United Kingdom

Sharon A. M. Stevelink, Estelle M. Malcolm & Nicola T. Fear

Academic Department of Military Mental Health, King’s College London, Weston Education Centre, 10 Cutcombe Road, SE5 9RJ, London, United Kingdom

Nicola T. Fear

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sharon A. M. Stevelink .

Additional information

Competing interests.

S.A.M.S., E.M.M. and N.T.F. are based at King’s College London, which receives funding from the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD). S.A.M.S. and E.M.M. receive funding from Blind Veterans UK to carry out the Blind Veterans UK study. The authors were not directed in any way by the charity or the MoD in relation to this publication.

Authors’ contribution

SAMS was involved in the planning of the study, in developing the data analysis strategy for this paper, participated in data collection, undertook the data analyses and wrote the paper. EMM was involved in developing the data analysis strategy for this paper, participated in data collection, undertook the data analyses, contributed to and commented on the paper. NTF was the principal investigator for this study, was involved in the design, planning and data analysis strategy development of the study and commented extensively on the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Coding framework with the two main themes identified for the current paper. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 2:

Semi-structured interview guideline. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Stevelink, S.A.M., Malcolm, E.M. & Fear, N.T. Visual impairment, coping strategies and impact on daily life: a qualitative study among working-age UK ex-service personnel. BMC Public Health 15 , 1118 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2455-1

Download citation

Received : 27 October 2014

Accepted : 26 October 2015

Published : 12 November 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2455-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health-related quality of life

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.36(3); 2022 Mar

Association of visual impairment with disability: a population-based study

John m. nesemann.

1 Francis I Proctor Foundation, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA USA

Ram P. Kandel

2 Seva Foundation, Berkeley, CA USA

Raghunandan Byanju

3 Bharatpur Eye Hospital, Bharatpur, Nepal

Bimal Poudyal

Gopal bhandari, sadhan bhandari, kieran s. o’brien.

4 Division of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA USA

Valerie M. Stevens

Jason s. melo, jeremy d. keenan.

5 Department of Ophthalmology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA USA

Associated Data

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, JMN.

To determine the relationship between visual impairment and other disabilities in a developing country.

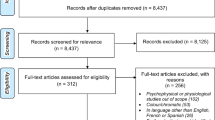

In this cross-sectional ancillary study, all individuals 50 years and older in 18 communities in the Chitwan region of Nepal were administered visual acuity screening and the Washington Group Short Set (WGSS) of questions on disability. The WGSS elicits a 4-level response for six disability domains: vision, hearing, walking/climbing, memory/concentration, washing/dressing, and communication. The association between visual impairment and disability was assessed with age- and sex-adjusted logistic regression models.

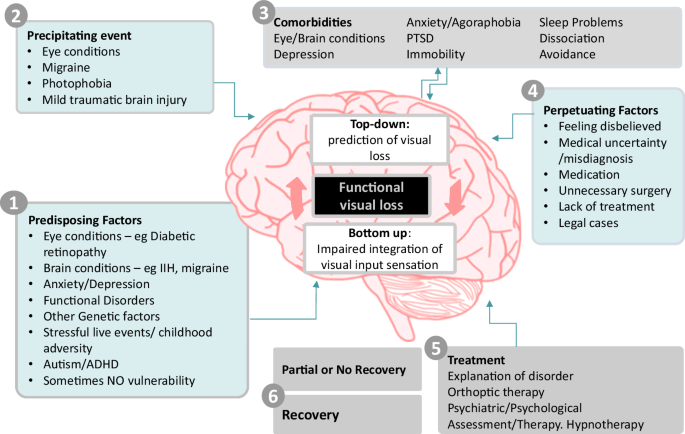

Overall, 4719 of 4726 individuals successfully completed visual acuity and disability screening. Median age of participants was 61 years (interquartile range: 55–69 years), and 2449 (51.9%) were female. Participants with vision worse than 6/60 in the better-seeing eye were significantly more likely to be classified as having a disability in vision (OR 18.4, 95% CI 9.9–33.5), walking (OR 5.3, 95% CI 2.9–9.1), washing (OR 9.4, 95% CI 4.0–21.1), and communication (OR 5.0, 95% CI 1.7–13.0), but not in hearing (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.006–2.2) or memory (OR 2.2, 95% CI 0.7–5.1).

Conclusions

Visually impaired participants were more likely to self-report disabilities, though causality could not be ascertained. Public health programs designed to reduce visual impairment could use the WGSS to determine unintended benefits of their interventions.

Introduction

Globally at least 2.2 billion people have visual impairment. Of these, at least 1 billion have visual impairment that has yet to be addressed or could have been prevented [ 1 ]. The 2017 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors study, which estimated years lived with disability to provide context about the burden of nonfatal diseases, found vision loss to be the third leading impairment for both sexes [ 2 ]. Moreover, the burden of visual impairment is forecast to increase substantially by 2050 as large portions of the global population age and life expectancy improves [ 3 ]. The high burden of visual impairment extends to the economic realm as well, leading to billions of dollars in productivity losses [ 4 ].

The burden of visual impairment is not distributed evenly. For example, the prevalence of distance visual impairment in low- and middle-income countries is estimated to be four times higher than that of high-income regions [ 5 ]. Furthermore, older individuals, women, and rural residents have also been found to have a higher risk of visual impairment [ 6 – 8 ]. Disabilities unrelated to vision are also thought to be associated with visual impairment, although supporting data are relatively sparse [ 1 ].

Disability refers to the impairments, limitations and restrictions that a person faces while interacting with their environment—physical, social, or attitudinal [ 1 ]. The importance of disability has received increased attention in recent years, but data on the relationship between visual impairment and disability are scant [ 9 ]. Several previous studies have examined the relationships between visual function, visual disability, and activities of daily living in high-income countries, and one study assessed self-reported disability and visual impairment using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule in six lower- and middle-income countries [ 10 – 13 ]. The results from these studies suggest an association between disability and visual impairment, but data from other settings would add confidence to the findings.

In the present study, we evaluated the relationship between visual impairment and self-reported disability using a standardized disability questionnaire developed by the United Nations Washington Group (WG) on Disability Statistics and recommended by the World Bank for household surveys [ 14 ]. We conducted the study in a resource-limited setting in Nepal, where the burden of both visual impairment and disability would be expected to be relatively high [ 5 ]. We hypothesized that visual impairment would be associated with higher self-reported disability.

Materials and methods

Study design and settings.

The study took place in the Chitwan district of Nepal from 16 January, 2018 to 22 December, 2019. At the time, the district was divided into numerous village development committees (VDC), which were in turn subdivided such that each VDC consisted of nine wards. As part of a cluster-randomized trial, 36 wards from 6 VDCs in the Chitwan district were randomized to receive a community-based eye disease screening intervention or no screening intervention. Screening visits were performed by the same screening team in a central area of the community. The present report is an ancillary cross-sectional study conducted only in the 18 communities randomized to the screening intervention; this ancillary study compares the results of a visual acuity assessment and a disability questionnaire completed during the screening visit. The study adhered to the Strengthening of the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.

Participants

All individuals aged 50 years or older who were found to be residing within the randomized communities on a door-to-door census conducted 1–4 weeks prior to the screening visit were invited to participate in the study. All consenting participants reported to a central location in the community to undergo visual acuity screening and a fill out a disability questionnaire.

Visual acuity

Each eye was tested separately using a visual acuity screening card developed by Nepal Netra Jyoti Sangh (Kathmandu, Nepal); the foldable card had four faces, three of which contained a single tumbling E optotype of a different size (i.e., corresponding to visual acuities of 6/60, 6/18, and 6/9 when tested at 6 m). Each optotype size was presented at 6 m in four arbitrary directions at the discretion of the tester, with a successful effort requiring a correct answer for all four directions. Testing was conducted in a well-lit environment outside of direct sunlight. The right eye was tested first with the left eye occluded and then the left eye was tested with the right eye occluded. Participants were tested with spectacle correction, if any was available (i.e., the WHO’s definition of presenting visual acuity), followed by pinhole occlusion. Visual acuity was defined at the person level as the smallest optotypes that could be read in the better-seeing eye, either with spectacle correction if available (i.e., presenting visual acuity) or through a pinhole occluder (i.e., pinhole acuity).

The Washington Group Short Set of questions on disability (WGSS) was translated into Nepali and administered verbally to each participant [ 15 ]. This questionnaire elicits a 4-level response (i.e., “no difficulty,” “some difficulty,” “a lot of difficulty,” or “cannot do at all”) for disabilities in six domains: vision, hearing, walking/climbing, memory/concentration, washing/dressing, and communication (Supplementary Fig. 1 ). The questionnaire was administered verbally to each participant.

Statistical considerations

The exposure of interest was presenting visual acuity in the better-seeing eye, dichotomized at three different thresholds (i.e., 6/9, 6/18, and 6/60—the three thresholds screened with the visual acuity card) indicating the ability versus the inability to see that line of vision. The outcome of interest was the presence of disability for each domain, with disability defined as “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all” in at least one domain on the WGSS, as recommended by the Washington Group on Disability Statistics [ 16 , 17 ]. Logistic regression models were constructed for each disability domain outcome and adjusted for the potential confounders of sex, age in years, and presence of self-reported diabetes mellitus (i.e., an indicator of systemic co-morbidity), with separate models to assess each of the visual acuity thresholds. Individuals with missing data were excluded from the analysis. In a secondary analysis, the prevalence of disability and visual impairment was calculated for each community, and community-level associations assessed with a linear regression weighted by the number of respondents per community. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated to determine the degree to which disability and visual impairment clustered within communities [ 18 ]. The sample size was based on the underlying clinical trial, and therefore, fixed; we planned to enrol at least 4500 people across the 18 communities. Assuming a 2% prevalence of blindness based on a prior study from Nepal [ 19 ], a 5% prevalence of disability in people without visual impairment, and an alpha of 0.05, then this sample size would provide ~80% power to estimate a 7.5% greater prevalence of disability in the visually impaired group. Centre values for descriptive statistics are reported as medians and all odds ratios (ORs) are presented with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The data met underlying assumptions for logistic regression models. Analyses were performed with R version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [ 20 ].

The study received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of California San Francisco, and ethical approval from Nepal Netra Jyoti Sangh, and the Nepali Health Research Council. The study adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal informed consent was obtained for all participants; verbal consent was approved by ethical committees due to the high levels of illiteracy in the study area. No stipend was provided.

A total of 4726 individuals aged 50 years or older presented for examination, of which 4719 successfully completed visual acuity and disability screening. The median age of participants successfully completing screening was 61 years (interquartile range: 55–69 years), and 2449 (51.9%) were female.

The best presenting visual acuity in the better-seeing eye was 6/9 in 3101 (65.7%) participants, 6/18 in 1148 (24.3%) participants, 6/60 in 369 (7.8%) participants, and worse than 6/60 in 101 (2.1%) participants. When disability was defined using the WG recommendation of “a lot of difficulty” or “inability” in at least one domain, 233 people (5.0%) reported having a disability. When disability was defined as “some difficulty” or worse in one or more domains, 842 people (17.8%) reported having a disability. Age- and sex-stratified results of the vision screening and disability questionnaire are summarized in Table 1 . As depicted in Fig. 1 , both visual impairment and the number of reported disabilities became significantly more prevalent with advanced age but did not differ substantially by sex. The proportion of people with a disability increased as presenting vision in the better-seeing eye worsened, regardless of whether the threshold for disability was defined as “some” difficulty or “a lot” of difficulty (Fig. 2 ).

Age- and sex-stratified disability and vision results.

The Washington Group Short Set disability questionnaire has four possible responses (no difficulty, some difficulty, a lot of difficulty, and cannot do at all) over six disability domains (vision, hearing, walking/climbing, memory/concentration, washing/dressing, and communication).

a Disability from the Washington Group Short Set, defined using two thresholds: (1) a lot of disability or worse (as recommended by the Washington Group), and (2) some disability or worse (since this definition has been used in other research). Values represent the number of individuals with a disability in (1) one or more of the six domains, and (2) two or more of the domains.

b Best presenting visual acuity of the three tested optotype sizes (i.e., 6/9, 6/18, and 6/60), in the better-seeing eye.

A The proportion with disabilities in each age group and B the proportion in each visual acuity group, defined by best presenting acuity.

Presenting acuity results were classified into four ordered groups based on the best visual acuity line successfully read. Bars show the distribution of disability scores within each vision group. Note limit of the y -axis is set to 40% so as to better visualize the distribution of disability scores within each vision group.

Participants with worse presenting visual acuity were more likely to self-report a disability, with greater magnitudes of association for those with more advanced vision loss (Fig. 3 ). For example, compared to those with better vision, participants whose presenting vision was worse than 6/60 in the better-seeing eye were more likely to be classified as having a disability in the vision (OR 18.4, 95% CI 9.9–33.5), walking (OR 5.3, 95% CI 2.9–9.1), washing (OR 9.4, 95% CI 4.0–21.1), and communication (OR 5.0, 95% CI 1.7–13.0) domains. In contrast, disabilities in the hearing and memory domains had weaker associations with visual impairment (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.06–2.2 and OR 2.2, 95% CI 0.7–5.1, respectively). Conclusions did not change when analyses were repeated with pinhole-corrected visual acuity (Supplementary Fig. 2 ).

Each dot represents the odds ratio from an age- and sex-adjusted logistic regression that models the presence of disability as a function of a dichotomous visual acuity exposure variable; bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Visual acuity groups indicate the best presenting visual acuity achieved (relative to those not achieving the respective acuity). The horizontal dashed line represents an odds ratio of 1.

The community prevalence of visual impairment (i.e., visual acuity worse than 6/60) did not significantly correlate with the community prevalence of disability (i.e., “a lot of difficulty” or “unable to do” in at least one domain of the WGSS), with each 10 percentage-point increase in the prevalence of visual impairment corresponding to a 3.1 percentage-point reduction (95% CI 25.6-point reduction to 19.4-point increase) in the prevalence of disability ( P = 0.77, regression weighted by a number of respondents per community; Fig. 4 ). Other thresholds of visual acuity impairment and disability were likewise not statistically significant. The magnitude of within-community clustering, as assessed by the ICC, was estimated to be 0.007 (95% CI 0–0.17) for the presence of at least one disability and 0.06 (95% CI 0–0.42) for presenting visual acuity impairment worse than 6/60.

Disability was defined as “a lot of difficulty” or “unable to do” in one or more domains of the disability questionnaire and visual impairment as best presenting acuity worse than 6/60. Each point represents a study community, sized proportional to the number of community members tested. The best-fit line from a linear regression of community-level data is shown as a dashed line.

This study’s principal finding was that people with visual impairment were more likely to have other self-reported disabilities. The likelihood of an association was strengthened by the observation of a dose response, with greater odds of disability for worsening states of visual impairment (Fig. 3 ).

We found that ~2.1% of the population 50 years or older in this region of Nepal had a presenting visual acuity worse than 6/60 in the better-seeing eye. Although the visual acuity thresholds and age groups of this study differ somewhat from prior studies, the extent of visual impairment observed here was generally in line with previous estimates of visual impairment in Nepal and indicates a relatively large burden of visual impairment in this region of Nepal [ 19 , 21 , 22 ].

Several previous studies found lower estimates of social and physical functioning in those with visual impairment, but these studies used a variety of measurement tools and did not focus specifically on disability [ 12 , 23 – 27 ]. For example, one study using data collected from 2007 to 2010 in six lower- and middle-income countries found an association between visual impairment and self-reported disability as assessed by the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 [ 13 ]. In the years since this study was completed, consensus has grown to support the United Nations WGSS of disability questions, a relatively quick 6-item questionnaire [ 28 ]. Use of this instrument in the present study enhances its generalizability and provides valuable, internationally comparable data. It was simple to incorporate into the study, added little time to fieldwork, and will help provide context to the main results of the clinical trial. We recommend its use by other research groups.

We found that approximately 5% of participants 50 years and older reported a lot of difficulty or inability in at least one of the tested disability domains, with rapidly increasing prevalence as the population aged (Fig. 1A ). Of the queried domains, self-reported difficulty with vision was most common. Reduced visual acuity was significantly associated with self-reported disabilities in walking, washing, and communication, but not hearing or memory (Fig. 3 ). Although this study cannot assess causality, it is reasonable to speculate that difficulty with vision would make walking and washing more challenging and could also hamper the ability to initiate and maintain communication. In contrast, vision has a less plausible direct causal impact on hearing loss, although both are associated with age. Of note, prior work has shown a longitudinal association between vision loss and cognitive decline [ 29 – 31 ]. The lack of an association between vision loss and memory in the present study could be due to several factors, including inadequate sample size, inability of a single question to accurately assess cognition when compared to the neuro-psychiatric tests used in other studies, and difficulty obtaining accurate responses from those who suffer severe deficits in cognition.

Despite the inability to assess causality in the present study, it is tempting to speculate whether interventions to improve visual acuity in a population could also reduce other perceived disabilities, especially since vision correction is likely a more easily modifiable risk factor than others for the disabilities elicited in this study. Future randomized trials of interventions that specifically target visual impairment, but not other disabilities, might consider including disability assessments as secondary outcomes.

The present study found that 5.0% of participants 50 years or older reported at least 1 disability when the threshold for a disability was set to “a lot” of difficulty (i.e., the cutoff recommended by the WG), and 17.8% when the threshold was defined as “some” difficulty in one or more domains (the definition employed by some other groups). These estimates are relatively consistent with population-based studies from Peru, Morocco, and Uganda, although the study definitions and/or reporting of outcomes are not exactly the same between the studies, making a direct comparison difficult [ 32 – 34 ]. These previous studies have found visual disability to be either the most common or second most common disability among the six tested domains, and have found an increasing prevalence of disability with age—each of which was also confirmed in the present study.

We found that community-level estimates of visual impairment did not correlate strongly with community-level disability prevalence, and that the magnitude of within-community clustering was minimal. This suggests that studies based on cluster sampling that seek to investigate the relationship between visual impairment and disability would likely be better off using an individual-level rather than community-level outcome.

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. Visual acuity was tested at only three acuity levels, limiting the granularity of the data and thus the statistical power. As stated above, the observational nature of the study precluded conclusions about causality. Ordinal multi-category data on disability and visual acuity impairment were dichotomized, a simplification that reduced statistical power but also made for more parsimonious regression models that were easier to interpret. While the regression models were adjusted for self-reported diabetes, data on other potential confounders of the relationship between vision and disability were not collected, preventing a more detailed multivariable analysis. Finally, while the inclusion of a random set of communities increased the study’s generalizability within this region of Nepal, the generalizability of the findings outside of Nepal is not clear: it is possible that visual impairment has a stronger magnitude of association with other disabilities in a place like Nepal with limited access to health services.

In summary, we found a significant association between visual impairment and disabilities in seeing, walking, washing, and communication, with higher odds of disability for groups with more advanced visual impairment in this area of Nepal. The causality of this association remains unclear. Incorporation of the WGSS into a community-based study of a blindness prevention program was quick and easy, and well accepted by the study participants. Inclusion of disability questions could be worthwhile for future studies of interventions for visual impairment, either to provide context about the characteristics of the study population or as a secondary outcome.

What was known before

- Disabilities unrelated to vision are thought to be associated with visual impairment although data is scarce.

What this study adds

- A population-based sample of adults 50 years and older in Nepal had visual acuity testing and answered a standardized disability questionnaire developed by the United Nations Washington Group on Disability Statistics and recommended by the World Health Organization.

- Individuals with vision worse than 6/60 in the better-seeing eye were more likely to report disabilities in vision, walking, washing, and communication but not hearing or memory.

- The questionnaire was easy to implement and may provide information on unintended benefits of public health programs intended to reduce visual impairment.

Supplementary information

Author contributions.

Concept and design: JDK, KSO, JSM, and VMS. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: JMN and JDK. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All Authors. Administrative, technical, or material support: RPK, RB, BP, HB, SB, KSO, VMS, and JSM. Supervision: JDK.