- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The 10 Best Essay Collections of the Decade

Ever tried. ever failed. no matter..

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels , the best short story collections , the best poetry collections , and the best memoirs of the decade , and we have now reached the fifth list in our series: the best essay collections published in English between 2010 and 2019.

The following books were chosen after much debate (and several rounds of voting) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

The Top Ten

Oliver sacks, the mind’s eye (2010).

Toward the end of his life, maybe suspecting or sensing that it was coming to a close, Dr. Oliver Sacks tended to focus his efforts on sweeping intellectual projects like On the Move (a memoir), The River of Consciousness (a hybrid intellectual history), and Hallucinations (a book-length meditation on, what else, hallucinations). But in 2010, he gave us one more classic in the style that first made him famous, a form he revolutionized and brought into the contemporary literary canon: the medical case study as essay. In The Mind’s Eye , Sacks focuses on vision, expanding the notion to embrace not only how we see the world, but also how we map that world onto our brains when our eyes are closed and we’re communing with the deeper recesses of consciousness. Relaying histories of patients and public figures, as well as his own history of ocular cancer (the condition that would eventually spread and contribute to his death), Sacks uses vision as a lens through which to see all of what makes us human, what binds us together, and what keeps us painfully apart. The essays that make up this collection are quintessential Sacks: sensitive, searching, with an expertise that conveys scientific information and experimentation in terms we can not only comprehend, but which also expand how we see life carrying on around us. The case studies of “Stereo Sue,” of the concert pianist Lillian Kalir, and of Howard, the mystery novelist who can no longer read, are highlights of the collection, but each essay is a kind of gem, mined and polished by one of the great storytellers of our era. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

John Jeremiah Sullivan, Pulphead (2011)

The American essay was having a moment at the beginning of the decade, and Pulphead was smack in the middle. Without any hard data, I can tell you that this collection of John Jeremiah Sullivan’s magazine features—published primarily in GQ , but also in The Paris Review , and Harper’s —was the only full book of essays most of my literary friends had read since Slouching Towards Bethlehem , and probably one of the only full books of essays they had even heard of.

Well, we all picked a good one. Every essay in Pulphead is brilliant and entertaining, and illuminates some small corner of the American experience—even if it’s just one house, with Sullivan and an aging writer inside (“Mr. Lytle” is in fact a standout in a collection with no filler; fittingly, it won a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize). But what are they about? Oh, Axl Rose, Christian Rock festivals, living around the filming of One Tree Hill , the Tea Party movement, Michael Jackson, Bunny Wailer, the influence of animals, and by god, the Miz (of Real World/Road Rules Challenge fame).

But as Dan Kois has pointed out , what connects these essays, apart from their general tone and excellence, is “their author’s essential curiosity about the world, his eye for the perfect detail, and his great good humor in revealing both his subjects’ and his own foibles.” They are also extremely well written, drawing much from fictional techniques and sentence craft, their literary pleasures so acute and remarkable that James Wood began his review of the collection in The New Yorker with a quiz: “Are the following sentences the beginnings of essays or of short stories?” (It was not a hard quiz, considering the context.)

It’s hard not to feel, reading this collection, like someone reached into your brain, took out the half-baked stuff you talk about with your friends, researched it, lived it, and represented it to you smarter and better and more thoroughly than you ever could. So read it in awe if you must, but read it. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Aleksandar Hemon, The Book of My Lives (2013)

Such is the sentence-level virtuosity of Aleksandar Hemon—the Bosnian-American writer, essayist, and critic—that throughout his career he has frequently been compared to the granddaddy of borrowed language prose stylists: Vladimir Nabokov. While it is, of course, objectively remarkable that anyone could write so beautifully in a language they learned in their twenties, what I admire most about Hemon’s work is the way in which he infuses every essay and story and novel with both a deep humanity and a controlled (but never subdued) fury. He can also be damn funny. Hemon grew up in Sarajevo and left in 1992 to study in Chicago, where he almost immediately found himself stranded, forced to watch from afar as his beloved home city was subjected to a relentless four-year bombardment, the longest siege of a capital in the history of modern warfare. This extraordinary memoir-in-essays is many things: it’s a love letter to both the family that raised him and the family he built in exile; it’s a rich, joyous, and complex portrait of a place the 90s made synonymous with war and devastation; and it’s an elegy for the wrenching loss of precious things. There’s an essay about coming of age in Sarajevo and another about why he can’t bring himself to leave Chicago. There are stories about relationships forged and maintained on the soccer pitch or over the chessboard, and stories about neighbors and mentors turned monstrous by ethnic prejudice. As a chorus they sing with insight, wry humor, and unimaginable sorrow. I am not exaggerating when I say that the collection’s devastating final piece, “The Aquarium”—which details his infant daughter’s brain tumor and the agonizing months which led up to her death—remains the most painful essay I have ever read. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (2013)

Of every essay in my relentlessly earmarked copy of Braiding Sweetgrass , Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s gorgeously rendered argument for why and how we should keep going, there’s one that especially hits home: her account of professor-turned-forester Franz Dolp. When Dolp, several decades ago, revisited the farm that he had once shared with his ex-wife, he found a scene of destruction: The farm’s new owners had razed the land where he had tried to build a life. “I sat among the stumps and the swirling red dust and I cried,” he wrote in his journal.

So many in my generation (and younger) feel this kind of helplessness–and considerable rage–at finding ourselves newly adult in a world where those in power seem determined to abandon or destroy everything that human bodies have always needed to survive: air, water, land. Asking any single book to speak to this helplessness feels unfair, somehow; yet, Braiding Sweetgrass does, by weaving descriptions of indigenous tradition with the environmental sciences in order to show what survival has looked like over the course of many millennia. Kimmerer’s essays describe her personal experience as a Potawotami woman, plant ecologist, and teacher alongside stories of the many ways that humans have lived in relationship to other species. Whether describing Dolp’s work–he left the stumps for a life of forest restoration on the Oregon coast–or the work of others in maple sugar harvesting, creating black ash baskets, or planting a Three Sisters garden of corn, beans, and squash, she brings hope. “In ripe ears and swelling fruit, they counsel us that all gifts are multiplied in relationship,” she writes of the Three Sisters, which all sustain one another as they grow. “This is how the world keeps going.” –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Hilton Als, White Girls (2013)

In a world where we are so often reduced to one essential self, Hilton Als’ breathtaking book of critical essays, White Girls , which meditates on the ways he and other subjects read, project and absorb parts of white femininity, is a radically liberating book. It’s one of the only works of critical thinking that doesn’t ask the reader, its author or anyone he writes about to stoop before the doorframe of complete legibility before entering. Something he also permitted the subjects and readers of his first book, the glorious book-length essay, The Women , a series of riffs and psychological portraits of Dorothy Dean, Owen Dodson, and the author’s own mother, among others. One of the shifts of that book, uncommon at the time, was how it acknowledges the way we inhabit bodies made up of variously gendered influences. To read White Girls now is to experience the utter freedom of this gift and to marvel at Als’ tremendous versatility and intelligence.

He is easily the most diversely talented American critic alive. He can write into genres like pop music and film where being part of an audience is a fantasy happening in the dark. He’s also wired enough to know how the art world builds reputations on the nod of rich white patrons, a significant collision in a time when Jean-Michel Basquiat is America’s most expensive modern artist. Als’ swerving and always moving grip on performance means he’s especially good on describing the effect of art which is volatile and unstable and built on the mingling of made-up concepts and the hard fact of their effect on behavior, such as race. Writing on Flannery O’Connor for instance he alone puts a finger on her “uneasy and unavoidable union between black and white, the sacred and the profane, the shit and the stars.” From Eminem to Richard Pryor, André Leon Talley to Michael Jackson, Als enters the life and work of numerous artists here who turn the fascinations of race and with whiteness into fury and song and describes the complexity of their beauty like his life depended upon it. There are also brief memoirs here that will stop your heart. This is an essential work to understanding American culture. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Eula Biss, On Immunity (2014)

We move through the world as if we can protect ourselves from its myriad dangers, exercising what little agency we have in an effort to keep at bay those fears that gather at the edges of any given life: of loss, illness, disaster, death. It is these fears—amplified by the birth of her first child—that Eula Biss confronts in her essential 2014 essay collection, On Immunity . As any great essayist does, Biss moves outward in concentric circles from her own very private view of the world to reveal wider truths, discovering as she does a culture consumed by anxiety at the pervasive toxicity of contemporary life. As Biss interrogates this culture—of privilege, of whiteness—she interrogates herself, questioning the flimsy ways in which we arm ourselves with science or superstition against the impurities of daily existence.

Five years on from its publication, it is dismaying that On Immunity feels as urgent (and necessary) a defense of basic science as ever. Vaccination, we learn, is derived from vacca —for cow—after the 17th-century discovery that a small application of cowpox was often enough to inoculate against the scourge of smallpox, an etymological digression that belies modern conspiratorial fears of Big Pharma and its vaccination agenda. But Biss never scolds or belittles the fears of others, and in her generosity and openness pulls off a neat (and important) trick: insofar as we are of the very world we fear, she seems to be suggesting, we ourselves are impure, have always been so, permeable, vulnerable, yet so much stronger than we think. –Jonny Diamond, Editor-in-Chief

Rebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions (2016)

When Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “Men Explain Things to Me,” was published in 2008, it quickly became a cultural phenomenon unlike almost any other in recent memory, assigning language to a behavior that almost every woman has witnessed—mansplaining—and, in the course of identifying that behavior, spurring a movement, online and offline, to share the ways in which patriarchal arrogance has intersected all our lives. (It would also come to be the titular essay in her collection published in 2014.) The Mother of All Questions follows up on that work and takes it further in order to examine the nature of self-expression—who is afforded it and denied it, what institutions have been put in place to limit it, and what happens when it is employed by women. Solnit has a singular gift for describing and decoding the misogynistic dynamics that govern the world so universally that they can seem invisible and the gendered violence that is so common as to seem unremarkable; this naming is powerful, and it opens space for sharing the stories that shape our lives.

The Mother of All Questions, comprised of essays written between 2014 and 2016, in many ways armed us with some of the tools necessary to survive the gaslighting of the Trump years, in which many of us—and especially women—have continued to hear from those in power that the things we see and hear do not exist and never existed. Solnit also acknowledges that labels like “woman,” and other gendered labels, are identities that are fluid in reality; in reviewing the book for The New Yorker , Moira Donegan suggested that, “One useful working definition of a woman might be ‘someone who experiences misogyny.'” Whichever words we use, Solnit writes in the introduction to the book that “when words break through unspeakability, what was tolerated by a society sometimes becomes intolerable.” This storytelling work has always been vital; it continues to be vital, and in this book, it is brilliantly done. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Valeria Luiselli, Tell Me How It Ends (2017)

The newly minted MacArthur fellow Valeria Luiselli’s four-part (but really six-part) essay Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions was inspired by her time spent volunteering at the federal immigration court in New York City, working as an interpreter for undocumented, unaccompanied migrant children who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border. Written concurrently with her novel Lost Children Archive (a fictional exploration of the same topic), Luiselli’s essay offers a fascinating conceit, the fashioning of an argument from the questions on the government intake form given to these children to process their arrivals. (Aside from the fact that this essay is a heartbreaking masterpiece, this is such a good conceit—transforming a cold, reproducible administrative document into highly personal literature.) Luiselli interweaves a grounded discussion of the questionnaire with a narrative of the road trip Luiselli takes with her husband and family, across America, while they (both Mexican citizens) wait for their own Green Card applications to be processed. It is on this trip when Luiselli reflects on the thousands of migrant children mysteriously traveling across the border by themselves. But the real point of the essay is to actually delve into the real stories of some of these children, which are agonizing, as well as to gravely, clearly expose what literally happens, procedural, when they do arrive—from forms to courts, as they’re swallowed by a bureaucratic vortex. Amid all of this, Luiselli also takes on more, exploring the larger contextual relationship between the United States of America and Mexico (as well as other countries in Central America, more broadly) as it has evolved to our current, adverse moment. Tell Me How It Ends is so small, but it is so passionate and vigorous: it desperately accomplishes in its less-than-100-pages-of-prose what centuries and miles and endless records of federal bureaucracy have never been able, and have never cared, to do: reverse the dehumanization of Latin American immigrants that occurs once they set foot in this country. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Zadie Smith, Feel Free (2018)

In the essay “Meet Justin Bieber!” in Feel Free , Zadie Smith writes that her interest in Justin Bieber is not an interest in the interiority of the singer himself, but in “the idea of the love object”. This essay—in which Smith imagines a meeting between Bieber and the late philosopher Martin Buber (“Bieber and Buber are alternative spellings of the same German surname,” she explains in one of many winning footnotes. “Who am I to ignore these hints from the universe?”). Smith allows that this premise is a bit premise -y: “I know, I know.” Still, the resulting essay is a very funny, very smart, and un-tricky exploration of individuality and true “meeting,” with a dash of late capitalism thrown in for good measure. The melding of high and low culture is the bread and butter of pretty much every prestige publication on the internet these days (and certainly of the Twitter feeds of all “public intellectuals”), but the essays in Smith’s collection don’t feel familiar—perhaps because hers is, as we’ve long known, an uncommon skill. Though I believe Smith could probably write compellingly about anything, she chooses her subjects wisely. She writes with as much electricity about Brexit as the aforementioned Beliebers—and each essay is utterly engrossing. “She contains multitudes, but her point is we all do,” writes Hermione Hoby in her review of the collection in The New Republic . “At the same time, we are, in our endless difference, nobody but ourselves.” –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Tressie McMillan Cottom, Thick: And Other Essays (2019)

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an academic who has transcended the ivory tower to become the sort of public intellectual who can easily appear on radio or television talk shows to discuss race, gender, and capitalism. Her collection of essays reflects this duality, blending scholarly work with memoir to create a collection on the black female experience in postmodern America that’s “intersectional analysis with a side of pop culture.” The essays range from an analysis of sexual violence, to populist politics, to social media, but in centering her own experiences throughout, the collection becomes something unlike other pieces of criticism of contemporary culture. In explaining the title, she reflects on what an editor had said about her work: “I was too readable to be academic, too deep to be popular, too country black to be literary, and too naïve to show the rigor of my thinking in the complexity of my prose. I had wanted to create something meaningful that sounded not only like me, but like all of me. It was too thick.” One of the most powerful essays in the book is “Dying to be Competent” which begins with her unpacking the idiocy of LinkedIn (and the myth of meritocracy) and ends with a description of her miscarriage, the mishandling of black woman’s pain, and a condemnation of healthcare bureaucracy. A finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for Nonfiction, Thick confirms McMillan Cottom as one of our most fearless public intellectuals and one of the most vital. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Dissenting Opinions

The following books were just barely nudged out of the top ten, but we (or at least one of us) couldn’t let them pass without comment.

Elif Batuman, The Possessed (2010)

In The Possessed Elif Batuman indulges her love of Russian literature and the result is hilarious and remarkable. Each essay of the collection chronicles some adventure or other that she had while in graduate school for Comparative Literature and each is more unpredictable than the next. There’s the time a “well-known 20th-centuryist” gave a graduate student the finger; and the time when Batuman ended up living in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, for a summer; and the time that she convinced herself Tolstoy was murdered and spent the length of the Tolstoy Conference in Yasnaya Polyana considering clues and motives. Rich in historic detail about Russian authors and literature and thoughtfully constructed, each essay is an amalgam of critical analysis, cultural criticism, and serious contemplation of big ideas like that of identity, intellectual legacy, and authorship. With wit and a serpentine-like shape to her narratives, Batuman adopts a form reminiscent of a Socratic discourse, setting up questions at the beginning of her essays and then following digressions that more or less entreat the reader to synthesize the answer for herself. The digressions are always amusing and arguably the backbone of the collection, relaying absurd anecdotes with foreign scholars or awkward, surreal encounters with Eastern European strangers. Central also to the collection are Batuman’s intellectual asides where she entertains a theory—like the “problem of the person”: the inability to ever wholly capture one’s character—that ultimately layer the book’s themes. “You are certainly my most entertaining student,” a professor said to Batuman. But she is also curious and enthusiastic and reflective and so knowledgeable that she might even convince you (she has me!) that you too love Russian literature as much as she does. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist (2014)

Roxane Gay’s now-classic essay collection is a book that will make you laugh, think, cry, and then wonder, how can cultural criticism be this fun? My favorite essays in the book include Gay’s musings on competitive Scrabble, her stranded-in-academia dispatches, and her joyous film and television criticism, but given the breadth of topics Roxane Gay can discuss in an entertaining manner, there’s something for everyone in this one. This book is accessible because feminism itself should be accessible – Roxane Gay is as likely to draw inspiration from YA novels, or middle-brow shows about friendship, as she is to introduce concepts from the academic world, and if there’s anyone I trust to bridge the gap between high culture, low culture, and pop culture, it’s the Goddess of Twitter. I used to host a book club dedicated to radical reads, and this was one of the first picks for the club; a week after the book club met, I spied a few of the attendees meeting in the café of the bookstore, and found out that they had bonded so much over discussing Bad Feminist that they couldn’t wait for the next meeting of the book club to keep discussing politics and intersectionality, and that, in a nutshell, is the power of Roxane. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Rivka Galchen, Little Labors (2016)

Generally, I find stories about the trials and tribulations of child-having to be of limited appeal—useful, maybe, insofar as they offer validation that other people have also endured the bizarre realities of living with a tiny human, but otherwise liable to drift into the musings of parents thrilled at the simple fact of their own fecundity, as if they were the first ones to figure the process out (or not). But Little Labors is not simply an essay collection about motherhood, perhaps because Galchen initially “didn’t want to write about” her new baby—mostly, she writes, “because I had never been interested in babies, or mothers; in fact, those subjects had seemed perfectly not interesting to me.” Like many new mothers, though, Galchen soon discovered her baby—which she refers to sometimes as “the puma”—to be a preoccupying thought, demanding to be written about. Galchen’s interest isn’t just in her own progeny, but in babies in literature (“Literature has more dogs than babies, and also more abortions”), The Pillow Book , the eleventh-century collection of musings by Sei Shōnagon, and writers who are mothers. There are sections that made me laugh out loud, like when Galchen continually finds herself in an elevator with a neighbor who never fails to remark on the puma’s size. There are also deeper, darker musings, like the realization that the baby means “that it’s not permissible to die. There are days when this does not feel good.” It is a slim collection that I happened to read at the perfect time, and it remains one of my favorites of the decade. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Charlie Fox, This Young Monster (2017)

On social media as in his writing, British art critic Charlie Fox rejects lucidity for allusion and doesn’t quite answer the Twitter textbox’s persistent question: “What’s happening?” These days, it’s hard to tell. This Young Monster (2017), Fox’s first book,was published a few months after Donald Trump’s election, and at one point Fox takes a swipe at a man he judges “direct from a nightmare and just a repulsive fucking goon.” Fox doesn’t linger on politics, though, since most of the monsters he looks at “embody otherness and make it into art, ripping any conventional idea of beauty to shreds and replacing it with something weird and troubling of their own invention.”

If clichés are loathed because they conform to what philosopher Georges Bataille called “the common measure,” then monsters are rebellious non-sequiturs, comedic or horrific derailments from a classical ideal. Perverts in the most literal sense, monsters have gone astray from some “proper” course. The book’s nine chapters, which are about a specific monster or type of monster, are full of callbacks to familiar and lesser-known media. Fox cites visual art, film, songs, and books with the screwy buoyancy of a savant. Take one of his essays, “Spook House,” framed as a stage play with two principal characters, Klaus (“an intoxicated young skinhead vampire”) and Hermione (“a teen sorceress with green skin and jet-black hair” who looks more like The Wicked Witch than her namesake). The chorus is a troupe of trick-or-treaters. Using the filmmaker Cameron Jamie as a starting point, the rest is free association on gothic decadence and Detroit and L.A. as cities of the dead. All the while, Klaus quotes from Artforum , Dazed & Confused , and Time Out. It’s a technical feat that makes fictionalized dialogue a conveyor belt for cultural criticism.

In Fox’s imagination, David Bowie and the Hydra coexist alongside Peter Pan, Dennis Hopper, and the maenads. Fox’s book reaches for the monster’s mask, not really to peel it off but to feel and smell the rubber schnoz, to know how it’s made before making sure it’s still snugly set. With a stylistic blend of arthouse suavity and B-movie chic, This Young Monster considers how monsters in culture are made. Aren’t the scariest things made in post-production? Isn’t the creature just duplicity, like a looping choir or a dubbed scream? –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Elena Passarello, Animals Strike Curious Poses (2017)

Elena Passarello’s collection of essays Animals Strike Curious Poses picks out infamous animals and grants them the voice, narrative, and history they deserve. Not only is a collection like this relevant during the sixth extinction but it is an ambitious historical and anthropological undertaking, which Passarello has tackled with thorough research and a playful tone that rather than compromise her subject, complicates and humanizes it. Passarello’s intention is to investigate the role of animals across the span of human civilization and in doing so, to construct a timeline of humanity as told through people’s interactions with said animals. “Of all the images that make our world, animal images are particularly buried inside us,” Passarello writes in her first essay, to introduce us to the object of the book and also to the oldest of her chosen characters: Yuka, a 39,000-year-old mummified woolly mammoth discovered in the Siberian permafrost in 2010. It was an occasion so remarkable and so unfathomable given the span of human civilization that Passarello says of Yuka: “Since language is epically younger than both thought and experience, ‘woolly mammoth’ means, to a human brain, something more like time.” The essay ends with a character placing a hand on a cave drawing of a woolly mammoth, accompanied by a phrase which encapsulates the author’s vision for the book: “And he becomes the mammoth so he can envision the mammoth.” In Passarello’s hands the imagined boundaries between the animal, natural, and human world disintegrate and what emerges is a cohesive if baffling integrated history of life. With the accuracy and tenacity of a journalist and the spirit of a storyteller, Elena Passarello has assembled a modern bestiary worthy of contemplation and awe. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Esmé Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias (2019)

Esmé Weijun Wang’s collection of essays is a kaleidoscopic look at mental health and the lives affected by the schizophrenias. Each essay takes on a different aspect of the topic, but you’ll want to read them together for a holistic perspective. Esmé Weijun Wang generously begins The Collected Schizophrenias by acknowledging the stereotype, “Schizophrenia terrifies. It is the archetypal disorder of lunacy.” From there, she walks us through the technical language, breaks down the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual ( DSM-5 )’s clinical definition. And then she gets very personal, telling us about how she came to her own diagnosis and the way it’s touched her daily life (her relationships, her ideas about motherhood). Esmé Weijun Wang is uniquely situated to write about this topic. As a former lab researcher at Stanford, she turns a precise, analytical eye to her experience while simultaneously unfolding everything with great patience for her reader. Throughout, she brilliantly dissects the language around mental health. (On saying “a person living with bipolar disorder” instead of using “bipolar” as the sole subject: “…we are not our diseases. We are instead individuals with disorders and malfunctions. Our conditions lie over us like smallpox blankets; we are one thing and the illness is another.”) She pinpoints the ways she arms herself against anticipated reactions to the schizophrenias: high fashion, having attended an Ivy League institution. In a particularly piercing essay, she traces mental illness back through her family tree. She also places her story within more mainstream cultural contexts, calling on groundbreaking exposés about the dangerous of institutionalization and depictions of mental illness in television and film (like the infamous Slender Man case, in which two young girls stab their best friend because an invented Internet figure told them to). At once intimate and far-reaching, The Collected Schizophrenias is an informative and important (and let’s not forget artful) work. I’ve never read a collection quite so beautifully-written and laid-bare as this. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Ross Gay, The Book of Delights (2019)

When Ross Gay began writing what would become The Book of Delights, he envisioned it as a project of daily essays, each focused on a moment or point of delight in his day. This plan quickly disintegrated; on day four, he skipped his self-imposed assignment and decided to “in honor and love, delight in blowing it off.” (Clearly, “blowing it off” is a relative term here, as he still produced the book.) Ross Gay is a generous teacher of how to live, and this moment of reveling in self-compassion is one lesson among many in The Book of Delights , which wanders from moments of connection with strangers to a shade of “red I don’t think I actually have words for,” a text from a friend reading “I love you breadfruit,” and “the sun like a guiding hand on my back, saying everything is possible. Everything .”

Gay does not linger on any one subject for long, creating the sense that delight is a product not of extenuating circumstances, but of our attention; his attunement to the possibilities of a single day, and awareness of all the small moments that produce delight, are a model for life amid the warring factions of the attention economy. These small moments range from the physical–hugging a stranger, transplanting fig cuttings–to the spiritual and philosophical, giving the impression of sitting beside Gay in his garden as he thinks out loud in real time. It’s a privilege to listen. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Honorable Mentions

A selection of other books that we seriously considered for both lists—just to be extra about it (and because decisions are hard).

Terry Castle, The Professor and Other Writings (2010) · Joyce Carol Oates, In Rough Country (2010) · Geoff Dyer, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition (2011) · Christopher Hitchens, Arguably (2011) · Roberto Bolaño, tr. Natasha Wimmer, Between Parentheses (2011) · Dubravka Ugresic, tr. David Williams, Karaoke Culture (2011) · Tom Bissell, Magic Hours (2012) · Kevin Young, The Grey Album (2012) · William H. Gass, Life Sentences: Literary Judgments and Accounts (2012) · Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack, and Honey (2012) · Herta Müller, tr. Geoffrey Mulligan, Cristina and Her Double (2013) · Leslie Jamison, The Empathy Exams (2014) · Meghan Daum, The Unspeakable (2014) · Daphne Merkin, The Fame Lunches (2014) · Charles D’Ambrosio, Loitering (2015) · Wendy Walters, Multiply/Divide (2015) · Colm Tóibín, On Elizabeth Bishop (2015) · Renee Gladman, Calamities (2016) · Jesmyn Ward, ed. The Fire This Time (2016) · Lindy West, Shrill (2016) · Mary Oliver, Upstream (2016) · Emily Witt, Future Sex (2016) · Olivia Laing, The Lonely City (2016) · Mark Greif, Against Everything (2016) · Durga Chew-Bose, Too Much and Not the Mood (2017) · Sarah Gerard, Sunshine State (2017) · Jim Harrison, A Really Big Lunch (2017) · J.M. Coetzee, Late Essays: 2006-2017 (2017) · Melissa Febos, Abandon Me (2017) · Louise Glück, American Originality (2017) · Joan Didion, South and West (2017) · Tom McCarthy, Typewriters, Bombs, Jellyfish (2017) · Hanif Abdurraqib, They Can’t Kill Us Until they Kill Us (2017) · Ta-Nehisi Coates, We Were Eight Years in Power (2017) · Samantha Irby, We Are Never Meeting in Real Life (2017) · Alexander Chee, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel (2018) · Alice Bolin, Dead Girls (2018) · Marilynne Robinson, What Are We Doing Here? (2018) · Lorrie Moore, See What Can Be Done (2018) · Maggie O’Farrell, I Am I Am I Am (2018) · Ijeoma Oluo, So You Want to Talk About Race (2018) · Rachel Cusk, Coventry (2019) · Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror (2019) · Emily Bernard, Black is the Body (2019) · Toni Morrison, The Source of Self-Regard (2019) · Margaret Renkl, Late Migrations (2019) · Rachel Munroe, Savage Appetites (2019) · Robert A. Caro, Working (2019) · Arundhati Roy, My Seditious Heart (2019).

Emily Temple

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples History

Essay Samples on 21St Century

Navigating the 21st century: understanding of modern learning.

The 21st century has ushered in a new era of unprecedented change, progress, and innovation. As the world evolves at an astonishing pace, so too must the methods of learning and education. This essay delves into the essence of the 21st century as it pertains...

- 21St Century

The Essential Role of Human Values in the 21st Century

The 21st century presents a myriad of challenges and opportunities that call for a renewed emphasis on human values as guiding principles to shape individual behaviors, societal norms, and global interactions. In an era marked by technological advancements, cultural diversification, and interconnectedness, the role of...

The Dynamic Role of Media in the 21st Century

The 21st century has ushered in a new era of media that transcends traditional boundaries, transforming the way information is disseminated, consumed, and shared. In this age of digitalization and connectivity, media in the 21st century holds unprecedented power to shape public opinion, influence cultural...

- Role of Media

Human Values in 21st Century: A Blueprint for a Better World

The 21st century presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities that demand a reevaluation of the values that guide human behavior. In this era of rapid technological advancements, cultural diversification, and interconnectedness, the importance of human values in the 21st century cannot be overstated....

Feminism in the 21st Century: Empowerment and Progress

The 21st century has witnessed a remarkable evolution in the feminist movement, with women and gender equality advocates making significant strides towards dismantling barriers, challenging stereotypes, and reshaping societal norms. Feminism in the 21st century is characterized by a global and intersectional approach that transcends...

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Education in the 21st Century: Navigating a Transformative Landscape

The 21st century has brought about profound changes in every aspect of human life, including education. The traditional classroom model is being reshaped by rapid technological advancements, shifts in pedagogical approaches, and evolving societal demands. Education in the 21st century is not only about imparting...

- Technology in Education

Communication in the 21st Century: Navigating the Digital Age

The 21st century has witnessed an unprecedented transformation in the way people communicate. Rapid technological advancements have reshaped the landscape of communication in the 21st century, enabling instant global connectivity, diverse modes of expression, and new challenges and opportunities. This essay explores the multifaceted nature...

- Communication

Beauty in the 21st Century: Embracing Diversity and Empowerment

The concept of beauty has evolved significantly in the 21st century, reflecting a cultural shift towards inclusivity, diversity, and empowerment. No longer confined to narrow standards, beauty in the 21st century celebrates individuality, challenges stereotypes, and embraces a broader range of ideals. This essay explores...

Advantages of 21st Century Learning: A Transformative Educational Landscape

The 21st century has brought about a paradigm shift in education, ushering in a new era of learning that is characterized by innovation, technology integration, and a focus on holistic skill development. The advantages of 21st century learning are manifold, revolutionizing the educational landscape and...

Exploring the Impact of 21st Century Technology

The 21st century has witnessed a technological revolution that has reshaped every facet of human existence. From communication to commerce, education to entertainment, the influence of 21st century technology is pervasive and transformative. This essay delves into the profound impact of technology in this era,...

- Modern Technology

The 21st Century Teacher: Education's Transformative

The role of a teacher has evolved significantly in the 21st century, reflecting the dynamic changes in education, technology, and the needs of modern learners. The 21st century teacher is not merely an instructor but a guide, mentor, and facilitator of learning. This essay delves...

Nurturing 21st Century Skills: Preparing for Success in the Modern World

The 21st century is characterized by rapid technological advancements, shifting global dynamics, and a growing need for individuals to possess a distinct set of skills that go beyond traditional academics. The acquisition of 21st century skills has become a critical component of education, enabling individuals...

Transforming Education in the 21st Century

Education in the 21st century has undergone a profound transformation, driven by the rapid advancement of technology, changing societal demands, and a growing recognition of the need for holistic skill development. This essay delves into the landscape of 21st century education, exploring the key features...

The 2020 Mark: Reflecting on a New Decade of Transformation

The transition into the new decade marked by 2020 was a moment of anticipation and reflection. As the previous decade drew to a close, and the dawn of the 2020s emerged, I found myself looking both backward and forward, considering the lessons learned and the...

Digital Piracy as Main Crime of 21st-Century

Humans have been performing illegal activities for years. With today’s 21st-century society being technology, illegal activity within the technological/internet-based realm is a major occurrence. Digital piracy is the illegal trade in software, videos, digital video devices, and music. Piracy occurs when someone other than the...

- Digital Era

John Dewey, and the 21st Century Cinematic Aesthetic Experience

John Dewey in his tenth volume written in 1934, Art as Experience, gave his theory on the arts and created a change in the way people viewed aesthetics and how artists created. Even though Dewey does not talk about film in his volume, except briefly...

To What Extent is NATO Still Relevant in the 21st Century

Introduction In 1949 a new military alliance was finalised bringing together 12 nations for mutual defence. However, now in the 21st century, the world has changed and it is time to re-evaluate NATO’s relevance. President Trump has already questioned the commitment of other countries to...

Gun Control: The Controversial Issue of the 21st Century

Do you want a safer future for both you and your family? Do you want America to actually be great again? Then help solve one of America’s biggest problems since it declared its independence in 1776: Guns. This topic is considered one of the most...

- Controversial Issue

- Gun Control

China's Vision of the Silk Road for the 21st Century

Since the break-up of the Soviet Union and the establishment of the independent Central Asian States, China has been extremely active in its effort to rehabilitate the concept of the “Silk Road”. This endeavour eventually helped shaped the Chinese government’s grand initiative “One Belt and...

“To Be Or Not To Be?” How Relevant Is Shakespeare

Shakespeare has been dead for over four hundred years now. Four hundred two years now to be exact. Many people recognize the name William Shakespeare but when was the last time you have read one of his poems or stories or even watched one of...

- William Shakespeare

Data In The 21St Century And Its Importance

In the 21st century, globalization is the spreading of everything around the world, especially the internet. Now, internet has become an important tool for the business success. The internet has helped the organizations to gathers and records data. In the 21st century, data is the...

- Data Collection

- Effects of Technology

Obsolescence Of Major War Between Great Powers In The 21st Century

Ever since the collapse of Communism in 1991, the international society has been experiencing perhaps the most peaceful era in history. However, others argue that threats to national security have not yet been completely eliminated and the potential for the next major war still prevails....

- Separation of Powers

Anthropological Pieces To Understand A Culture

More Than Just Words If you were asked to define your culture in one sentence, what would you say? Would you mention the food, clothing, or beliefs? Would you feel satisfied with your answer, or feel the need to add more? Describing your culture to...

- Anthropology

Best topics on 21St Century

1. Navigating the 21st Century: Understanding of Modern Learning

2. The Essential Role of Human Values in the 21st Century

3. The Dynamic Role of Media in the 21st Century

4. Human Values in 21st Century: A Blueprint for a Better World

5. Feminism in the 21st Century: Empowerment and Progress

6. Education in the 21st Century: Navigating a Transformative Landscape

7. Communication in the 21st Century: Navigating the Digital Age

8. Beauty in the 21st Century: Embracing Diversity and Empowerment

9. Advantages of 21st Century Learning: A Transformative Educational Landscape

10. Exploring the Impact of 21st Century Technology

11. The 21st Century Teacher: Education’s Transformative

12. Nurturing 21st Century Skills: Preparing for Success in the Modern World

13. Transforming Education in the 21st Century

14. The 2020 Mark: Reflecting on a New Decade of Transformation

15. Digital Piracy as Main Crime of 21st-Century

- Civil Rights Movement

- American History

- Florence Nightingale

- African Diaspora

- Industrial Revolution

- Eleanor Roosevelt

- Monroe Doctrine

- Alexander The Great

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Home — Essay Samples — History — Contemporary History — 21St Century

Essays on 21st Century

Choosing 21st century essay topics.

As we navigate through the 21st century, the world around us is constantly evolving, and this evolution comes with a plethora of complex issues and topics that are ripe for exploration and discussion. When it comes to selecting an essay topic for your academic assignments, it's important to choose a subject that is not only relevant but also engaging and thought-provoking. In this article, we will delve into the importance of choosing a 21st-century essay topic, provide advice on how to select a topic, and offer a detailed list of recommended essay topics across various categories.

The Importance of the Topic

Choosing a relevant and impactful essay topic is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, it allows you to engage with current events and trends, fostering a deeper understanding of the world around us and its complexities. Secondly, a well-chosen topic can spark meaningful discussions and debates, both within academic circles and in society at large. Additionally, selecting a 21st-century essay topic can help you develop critical thinking and analytical skills, as you navigate through the complexities of contemporary issues.

Advice on Choosing a Topic

When it comes to selecting an essay topic, it's important to consider your interests, as well as the relevance and significance of the subject matter. Start by brainstorming a list of topics that intrigue you and align with your academic goals. Consider the potential impact of the topic and its relevance to modern society. Research the latest developments and debates surrounding the topic to ensure that you have access to current and credible sources. Lastly, make sure the topic is broad enough to provide you with ample research material, but also specific enough to allow for in-depth exploration.

Recommended Essay Topics

Social issues.

- The impact of social media on mental health

- Income inequality in the 21st century

- The rise of fake news and its implications

- The role of activism in contemporary society

Technology and Innovation

- The ethical implications of artificial intelligence

- The future of renewable energy sources

- Privacy and data protection in the digital age

- The impact of technology on the job market

Environmental Concerns

- The effects of climate change on global communities

- Sustainable practices for a greener future

- The role of activism in environmental conservation

- The intersection of environmentalism and social justice

Global Politics

- International responses to humanitarian crises

- Nationalism and its impact on global diplomacy

- The role of the United Nations in the 21st century

- The rise of populism and its implications for global governance

Cultural Identity

- The impact of globalization on cultural diversity

- The portrayal of gender and race in contemporary media

- The intersection of technology and cultural heritage

- The role of art and literature in shaping cultural identities

These are just a few examples of the myriad of topics that you can explore for your 21st-century essay. Remember to choose a topic that resonates with you and aligns with your academic interests. By delving into the complexities of contemporary issues, you can develop a deeper understanding of the world around us and contribute to meaningful discussions and debates.

Reflections on a Half-century: The World 50 Years Ago

Feminism as a movement of the 21st century, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

A Look at Racism in The 21st Century and Efforts to Stop It

Understanding the skills required to be successful in the 21st century, educational system in the 21 century, the effects of globalization on the 21st century societies and the role of religion in the analysis of kwame anthony appiah, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Geothermal Energy as The Solution to The 21st Century Problem of Energy

Most pressing issue facing the 21st century, discussion of whether equality is the end of chivalry, advertisement in 21 century, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Comparison of Online Dating and Traditional Dating

Comic books in the 21st century, a lesson to never give up in "the odyssey", a poem by homer, organizational structure and management: alibaba and the 21st century, challenges faced by native americans in 21str century, trump and the rise of 21st century fascism, princess diana’s memoir, a study on the impact of corporate accountability, understanding the craze behind esports, the changing role of accountants in the 21st century, sylvia plath’s presentation of feelings and standards on women as described in her book, the bell jar, analysis on communication as a factor in relationships, understanding the representation of black females sexual desirability in the u.s, how lucky i am to be born in this century, consensual cannibalism in the 21st century.

The beginning of the 21st century was the rise of a global warming, global economy and Third World consumerism, increased private enterprise and terrorist attacks. Many great and many bad things happened in the current century. Many natural and man-made disasters made their impact on the world.

In the 21st century the effects of social development have affected different countries and different social groups differently. Although social development upgraded life standards of population.

The main challenges in the 21st century are: climate change, plastic pollution in the oceans, natural hazards, air pollution, hunger and increased inequalities.

Technology in the 21st century has enabled to humans to make strides that our ancestors could only dream of. People in the 21st century live in a technology and media-suffused environment.

The world population was about 6.1 billion at the start of the 21st century and reached 7.8 billion by March 2020.

Economically and politically, the United States and Western Europe were dominant at the beginning of the century. By the 2010s, China became an emerging global superpower and the world's largest economy. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are increasing in popularity worldwide.

The 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers, Hurricane Katrina, Same-Sex Marriage Legalisation, Haiti Earthquake, The Arab Spring, Brexit

Relevant topics

- Jack The Ripper

- Roaring Twenties

- 19Th Century

- Moon Landing

- China Crisis

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Cuban Revolution

- Mother Teresa

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essay About 21st Century

21st Century America

Part 2 -What kind of world do we want for the 21st century? In today's society, when people are asked the question “what are your hopes for the world”, many automatically respond with “achieving world peace” and this is a great dream, but it is just a dream, not reality. People have begun to fight for world peace without thinking rationally about what it means because world wide conflict has become a very substantial conflict in the world today. People around the world have recognized that raising

Life In The 21st Century

we like, while others create fear and anxiety. Several predictions were made that the world will end in 2012 based on the rollover of the Mayan calendar but all these forecasting were proved to be fictitious. On the contrary we are living in the 21st century, 2025 and the world has changed tremendously in the last 13 years. The world has been transformed by the digital revolution and advances in medicine and human knowledge. The present-day civilization stands on two legs, one is spirituality, and

The Beginning Of The 21st Century

The 21st Century, the time period that we all live in today, smothered in continuous social, economic and political issues. An interesting era for films of this genre is the late 1930’s to early 1940’s which we see reflections in the literature today. War World 2 was a turning point in history and was a time of sheer horror in many places such as Spain, Germany, Poland and Eastern Europe. In today’s age, contemporary literature writers often draw their inspiration and ideas from the writers that

21st Century Skills in Education

In the 21st century, the world is changing and becoming increasingly complex as the flow of information increases and becomes more accessible day by day. The world is radically more different than it was just a few years ago, hard to imagine that it’s such a short period of time - the world and its people, economies and cultures have become inextricably connected, driven by the Internet, new innovations and low-cost telecommunications technology. A computer is a must, to be a successful student

The Importance Of Education In The 21st Century

Teaching and learning in the 21st century develop skills beyond listening, watching and remembering. Education in the 21st century incorporates advanced learning tools, development of skills, while actively involved in your own learning and environment. Also, education today is motivating while inspiring and preparing students for today’s world. Students gain the ability to adapt when needed for the changing world of tomorrow. Twenty-first century education is understanding how students learn with

The Role Of A Teacher In The 21st Century

The role of the teacher in the 21st century education consists of the teacher demonstrating leadership among the staff and with the administration-bringing consensus and common, shared ownership of the school’s vision and purpose. It is important for the teacher to make the instructional content engaging, relevant, and meaningful to students’ lives; teach core content that includes critical thinking, problem solving, addition to information and communications technology (ICT) literacy; and facilitate

21st Century Literacy In Education

times, they are a-changin” (Robinson, McKenna & Conradi, 2012, p. 223). Robinson, McKenna and Conradi discuss in their research about a common myth of 21st-Century literacy; that “21st-century literacy is about technology only” (Robinson, McKenna & Conradi, 2012, p. 227). As an educator, I agree with Robinson, McKenna and Conradi that 21st-Century literacy is not only about technology. Technology is a wonderful supplement to learning literacy, however it does not take the place of learning to read

Spooky Superstitions In The 21st Century

Superstitions Step on a crack and you will break your mother's back, a long ago, superstition but yet is still heard in the 21st century. Today lots of the things humans use has been through both innovation and science, but yet people still are wary of superstitions even though most have been disproven. The 5 main superstitions that are still prevalent in the 21st century are buildings not having a 13th floor, opening an umbrella inside, saying bless you, naming boats, and the most recently big

Forensic Science in the 21st Century

Forensic Science in the 21st Century Gertrude West Forensic Science and Psychological Profiling /CJA590 May 30, 2011 Edward Baker Forensic Science in the 21st Century Forensic science has various influences on crime, investigation and the people that are involved. Forensic science has a connection with the courts to ensure crimes are getting solved and justice is being served to those that commit crimes. With the help of forensic science, crimes are being solved from a human and technological

Tyranny : Slavery Of The 21st Century

Tyranny: Slavery Of the 21st century The last twenty-six years have been the most painful years for the Eritrean people. For more than two decades Eritreans went through the most brutal acts of evil. Here, I would like to share my personal experience and testimony. I vividly remember the colourful and joyful day when Eritrea was liberated from the Ethiopia rule in 1991. Though I was only six-years old my memory is still clear, and I remember the joy and happiness that Eritreans expressed then. We

Popular Topics

- A Christmas Carol Essay

- A Clean, Well-Lighted Place Essay

- A Clockwork Orange Free Will Essay

- A Description of New England Essay

- A Doll's House Freedom Essay

- A Doll's House Essay Nora

- A Doll's House Society Essay

- A Doll's House Torvald Essay

- A Farewell to Arms Essay

- A Farewell to Arms Death Essay

To arrive at the edge of the world's knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves.

Writing In The 21st Century

What are the arts but products of the human mind which resonate with our aesthetic and emotional faculties? What are social issues, but ways in which humans try to coordinate their behavior and come to working arrangements that benefit everyone? There's no aspect of life that cannot be illuminated by a better understanding of the mind from scientific psychology. And for me the most recent example is the process of writing itself.

Introduction

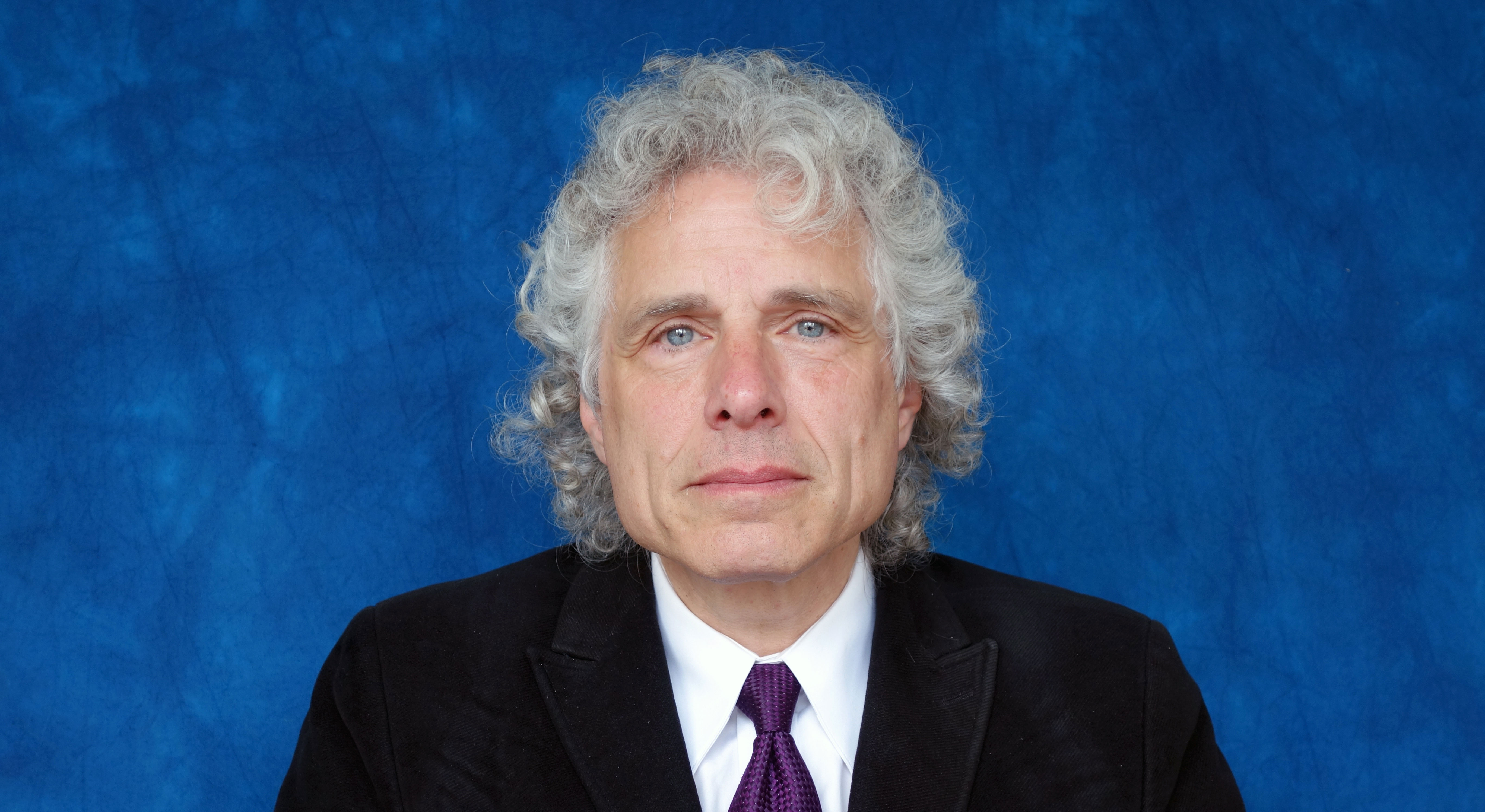

Psychologist Steven Pinker's 1994 book The Language Instinct discussed all aspects of language in a unified, Darwinian framework, and in his next book, How The Mind Works he did the same for the rest of the mind, explaining "what the mind is, how it evolved, and how it allows us to see, think, feel, laugh, interact, enjoy the arts, and ponder the mysteries of life."

He has written four more consequential books: Words and Rules (1999 ), The Blank Slate (2002 ), The Stuff of Thought (2007 ), and The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011) . The evolution in his thinking, and the expansion of his range, the depth of his vision, are evident in his contributions on many important issues on these pages over the years: "A Biological Understanding of Human Nature," "The Science of Gender and Science," "A Preface to Dangerous Ideas," "Language and Human Nature," "A History of Violence," "The False Allure of Group Selection," "Napoleon Chagnon: Blood Is Their Argument," and "Science Is Not Your Enemy." In addition to his many honors, he is the Edge Question Laureate, having suggested three of Edge's Annual Questions: "What Is Your Dangerous Idea?"; What Is Your Favorite Deep, Elegant, Or Beautiful Explanation?"; and "What Scientific Concept Would Improve Everybody's Cognitive Toolkit?". He is a consummate third culture intellectual.

In the conversation below, Pinker begins by stating his belief that "science can inform all aspects of life, particularly psychology, my own favorite science. Psychology looks in one direction to biology, to neuroscience, to genetics, to evolution. And it looks in another direction to the rest of intellectual and cultural life—because what are the arts but products of the human mind which resonate with our aesthetic and emotional faculties? What are social issues but ways in which humans try to coordinate their behavior and come to working arrangements that benefit everyone? There's no aspect of life that cannot be illuminated by a better understanding of the mind from scientific psychology. And for me the most recent example is the process of writing itself."...

— John Brockman

STEVEN PINKER is the Johnstone Family Professor in the Department of Psychology at Harvard University. He is the author of ten books, including The Language Instinct, How the Mind Works, The Better Angels of Our Nature , and The Sense of Style (September). Steven Pinker's Edge Bio page

WRITING IN THE 21ST CENTURY

I believe that science can inform all aspects of life, particularly psychology, my own favorite science. Psychology looks in one direction to biology, to neuroscience, to genetics, to evolution. And it looks in another direction to the rest of intellectual and cultural life—because what are the arts but products of the human mind which resonate with our aesthetic and emotional faculties? What are social issues but ways in which humans try to coordinate their behavior and come to working arrangements that benefit everyone? There's no aspect of life that cannot be illuminated by a better understanding of the mind from scientific psychology. And for me the most recent example is the process of writing itself.

I'm a psychologist who studies language—a psycholinguist—and I'm also someone who uses language in my books and articles to convey ideas about, among other things, the science of language itself. But also, ideas about war and peace and emotion and cognition and human nature. The question I'm currently asking myself is how our scientific understanding of language can be put into practice to improve the way that we communicate anything, including science?

In particular, can you use linguistics, cognitive science, and psycholinguistics to come up with a better style manual—a 21st century alternative to the classic guides like Strunk and White's The Elements of Style ?

Writing is inherently a topic in psychology. It's a way that one mind can cause ideas to happen in another mind. The medium by which we share complex ideas, namely language, has been studied intensively for more than half a century. And so if all that work is of any use it ought to be of use in crafting more stylish and transparent prose.

From a scientific perspective, the starting point must be different from that of traditional manuals, which are lists of dos and don'ts that are presented mechanically and often followed robotically. Many writers have been the victims of inept copyeditors who follow guidelines from style manuals unthinkingly, never understanding their rationale.

For example, everyone knows that scientists overuse the passive voice. It's one of the signatures of academese: "the experiment was performed" instead of "I performed the experiment." But if you follow the guideline, "Change every passive sentence into an active sentence," you don't improve the prose, because there's no way the passive construction could have survived in the English language for millennia if it hadn't served some purpose.

The problem with any given construction, like the passive voice, isn't that people use it, but that they use it too much or in the wrong circumstances. Active and passive sentences express the same underlying content (who did what to whom) while varying the topic, focus, and linear order of the participants, all of which have cognitive ramifications. The passive is a better construction than the active when the affected entity (the thing that has moved or changed) is the topic of the preceding discourse, and should therefore come early in the sentence to connect with what came before; when the affected entity is shorter or grammatically simpler than the agent of the action, so expressing it early relieves the reader's memory load; and when the agent is irrelevant to the story, and is best omitted altogether (which the passive, but not the active, allows you to do). To give good advice on how to write, you have to understand what the passive can accomplish, and therefore you should not blue-pencil every passive sentence into an active one (as one of my copyeditors once did).

Ironically, the aspect of writing that gets the most attention is the one that is least important to good style, and that is the rules of correct usage. Can you split an infinitive, that is, say, "to boldly go where no man has gone before,"or must you say to "go boldly"? Can you use the so-called fused participle—"I approve of Sheila taking the job"—as opposed to "I approve of Sheila's taking the job" (with an apostrophe "s")? There are literally (yes, "literally") hundreds of traditional usage issues like these, and many are worth following. But many are not, and in general they are not the first things to concentrate on when we think about how to improve writing.

The first thing you should think about is the stance that you as a writer take when putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. Writing is cognitively unnatural. In ordinary conversation, we've got another person across from us. We can monitor the other person's facial expressions: Do they furrow their brow, or widen their eyes? We can respond when they break in and interrupt us. And unless you're addressing a stranger you know the hearer's background: whether they're an adult or child, whether they're an expert in your field or not. When you're writing you have none of those advantages. You're casting your bread onto the waters, hoping that this invisible and unknowable audience will catch your drift.

The first thing to do in writing well—before worrying about split infinitives—is what kind of situation you imagine yourself to be in. What are you simulating when you write, and you're only pretending to use language in the ordinary way? That stance is the main thing that iw distinguishes clear vigorous writing from the mush we see in academese and medicalese and bureaucratese and corporatese.

The literary scholars Mark Turner and Francis-Noël Thomas have identified the stance that our best essayists and writers implicitly adopt, and that is a combination of vision and conversation. When you write you should pretend that you, the writer, see something in the world that's interesting, that you are directing the attention of your reader to that thing in the world, and that you are doing so by means of conversation.

That may sound obvious. But it's amazing how many of the bad habits of academese and legalese and so on come from flouting that model. Bad writers don't point to something in the world but areself-conscious about not seeming naïve about the pitfalls of their own enterprise. Their goal is not to show something to the reader but to prove that they are nota bad lawyer or a bad scientist or a bad academic. And so bad writing is cluttered with apologies and hedges and "somewhats" and reviews of the past activity of people in the same line of work as the writer, as opposed to concentrating on something in the world that the writer is trying to get someone else to see with their own eyes.

That's a starting point to becoming a good writer. Another key is to be an attentive reader. One of the things you appreciate when you do linguistics is that a language is a combination of two very different mechanisms: powerful rules, which can be applied algorithmically, and lexical irregularities, which must be memorized by brute force: in sum, words and rules.

All languages contain elegant, powerful, logical rules for combining words in such a way that the meaning of the combination can be deduced from the meanings of the words and the way they're arranged. If I say "the dog bit the man" or "the man bit the dog," you have two different images, because of the way those words are ordered by the rules of English grammar.

On the other hand, language has a massive amount of irregularity: idiosyncrasies, idioms, figures of speech, and other historical accidents that you couldn't possibly deduce from rules, because often they are fundamentally illogical. The past tense of "bring" is "brought," but the past tense of "ring" is "rang," and the past tense of "blink" is "blinked." No rule allows you to predict that; you need raw exposure to the language. That's also true for many rules of punctuation. . If I talk about "Pat's leg," it's "Pat-apostrophe-s." But If I talk about "its leg," I can't use apostrophe S; that would be illiterate. Why? Who knows? That's just the way English works. Peole who spell possessive "its" with an apostrophe are not being illogical; they're being too logical, while betraying the fact that they haven't paid close attention to details of the printed page.

So being a good writer depends not just on having mastered the logical rules of combination but on having absorbed tens or hundreds of thousands of constructions and idioms and irregularities from the printed page. The first step to being a good writer is to be a good reader: to read a lot, and to savor and reverse-engineer good prose wherever you find it. That is, to read a passage of writing and think to yourself, … "How did the writer achieve that effect? What was their trick?" And to read a good sentence with a consciousness of what makes it so much fun to glide through.

Any handbook on writing today is going to be compared to Strunk & White's The Elements of Style , a lovely little book, filled with insight and charm, which I have read many times. But William Strunk, its original author, was born in 1869. This is a man who was born before the invention of the telephone, let alone the computer and the Internet and the smartphone. His sense of style was honed in the later decades of the 19th century!

We know that language changes. You and I don't speak the way people did in Shakespeare's era, or in Chaucer's. As valuable as The Elements of Style is (and it's tremendously valuable), it's got a lot of cockamamie advice, dated by the fact that its authors were born more than a hundred years ago. For example, they sternly warn, "Never use 'contact' as a verb. Don't say 'I'm going to contact him.' It's pretentious jargon, pompous and self-important. Indicate that you intend to 'telephone' someone or 'write them' or 'knock on their door.'" To a writer in the 21st century, this advice is bizarre. Not only is "to contact" thoroughly entrenched and unpretentious, but it's indispensable. Often it's extremely useful to be able to talk about getting in touch with someone when you don't care by what medium you're going to do it, and in those cases, "to contact" is the perfect verb. It may have been a neologism in Strunk and White's day, but all words start out as neologisms in their day. If you read The Elements of Style today, you have no way of appreciating that what grated on the ears of someone born in 1869 might be completely unexceptionable today.

The other problem is that The Elements of Style was composed before there existed a science of language and cognition. A lot of Strunk and White's advice depended completely on their gut reactions from a lifetime of practice as an English professor and critic, respectively. Today we can offer deeper advice, such as the syntactic and discourse functions of the passive voice—a construction which, by the way, Strunk & White couldn't even consistently identify, not having being trained in grammar.

Another advantage of modern linguistics and psycholinguistics is that it provides a way to think your way through a pseudo-controversy that was ginned up about 50 years ago between so-called prescriptivists and descriptivists. According to this fairy tale there are prescriptivists who prescribe how language ought to be used and there are descriptivists, mainly academic linguists, who describe how language in fact is used. In this story there is a war between them, with prescriptivist dictionaries competing with descriptivist . dictionaries.

Inevitably my own writing manual is going to be called "descriptivist," because it questions a number of dumb rules that are routinely flouted by all the best writers and had no business being in stylebooks in the first place. These pseudo-rules violate the logic of English but get passed down as folklore from one style sheet to the next. But debunking stupid rules is not the same thing as denying the existence of rules, to say nothing of advice on writing. The Sense of Style is clearly prescriptive: it consists of 300 pages in which I boss the reader around.

This pseudo-controversy was created when Webster's Third International Dictionary was published in the early 1960s. Like all dictionaries, it paid attention to the way that language changes. If a dictionary didn't do that it would be useless: writers who consulted it would be guaranteed to be misunderstood. For example, there is an old prescriptive rule that says that "nauseous," which most people use to mean nauseated, cannot mean that. It must mean creating nausea, namely, "nauseating." You must write that a roller coaster ride was nauseous, or a violentmovie was nauseous, not I got nauseous riding on the roller coaster or watching the movie. Nowadays, no one obeys this rule. If a dictionary were to stick by its guns and say it's an error to say that the movie made me nauseous, it would be a useless dictionary: it wouldn't be doing what a dictionary has to do. This has always been true of dictionaries.

But there's a myth that dictionaries work like the rulebook of Major League Baseball; they legislate what is correct. I can speak with some authority in saying that this is false. I am the Chair of the Usage Panel of The American Heritage Dictionary , which is allegedly the prescriptivist alternative to the descriptivist Webster's . But when I asked the editors how they decide what goes into the dictionary, they replied, "By paying attention to the way people use language."

Of course dictionary editors can't pay attention to the way everyone uses language, because people use language in different ways. When you write, you're writing for a virtual audience of well-read, literate fellow readers. And those are the people that we consult in deciding what goes into the dictionary, particularly in the usage notes that comment on controversies of usage, so that readers will know what to anticipate when they opt to obey or flout an alleged rule.

This entire approach is sometimes criticized by literary critics who are ignorant of the way that language works, and fantasize about a golden age in which dictionaries legislated usage. But language has always been a grassroots, bottom-up phenomenon. The controversy between "prescriptivists" and "descriptivists" is like the choice in "America: Love it or leave it" or "Nature versus Nurture"—a euphonious dichotomy that prevents you from thinking.

Many people get incensed about so-called errors of grammar which are perfectly unexceptionable. There was a controversy in the 1960s over the advertising slogan "Winston tastes good, like a cigarette should." The critics said it should be " as a cigarette should" and moaned about the decline of standards. . A more recent example was an SAT question that asked students whether there was an error in "Toni Morrison's genius allows her to write novels that capture the African American condition." Supposedly the sentence is ungrammatical: you can't have "Toni Morrison's" as an antecedent to the pronoun "she." Now that is a complete myth: there was nothing wrong with the sentence.